Abstract

Objectives:

Pressure ulcers are the most common condition among palliative care patients at home care facilities and impose a significant burden on patients, their relatives, and caregivers. Caregivers play a vital role in preventing pressure ulcers. When the caregivers are knowledgeable about preventing pressure ulcers, they will be able to avoid lots of discomfort for the patients. It will help the patient to achieve the best quality of life and spend the last days of life peacefully and comfortably with dignity. It is essential to develop evidence-based guidelines for caregivers of palliative care patients on pressure ulcer prevention, which may play a major role in preventing pressure ulcers. The primary objective is to implement evidence-based guidelines for caregivers of palliative care patients on pressure ulcer prevention.The secondary objective is to improve the knowledge and practice of caregivers and enable them to take measures to prevent pressure ulcer development among palliative care patients, thereby improving the quality of life of palliative care patients.

Materials and Methods:

Following PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses), a systematic review was conducted. The search was conducted using electronic databases Pub Med, CINHAL, Cochrane and EMBASE database. The studies selected were in the English language and with free full text. The studies were selected and assessed for quality using the Cochrane risk assessment tool. Clinical practice guidelines, systematic reviews, and randomized controlled trials conducted on pressure ulcer prevention in palliative care patients were selected for the review. Twenty Eight studies were found to be potentially relevant after screening the search results. Twelve studies were not found suitable. 5 RCTs did not meet the inclusion criteria. Finally, four systematic reviews, five RCTs, and two clinical practice guidelines were included in the study, and guidelines were prepared.

Results:

Based on the best available research evidence, clinical practice guidelines were developed on skin assessment, skin care, repositioning, mobilization, nutrition, and hydration to prevent pressure ulcers to guide caregivers of palliative care patients.

Conclusion:

The evidence-based nursing practice integrates the best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values. Evidence-based nursing practice leads to a problem-solving approach which is existing or anticipated. This will contribute to choosing appropriate preventive strategies for maintaining patients’ comfort, thereby improving the quality of life of palliative care patients. The guidelines were prepared through an extensive systematic review, RCT, and other guidelines followed in different settings and modified to suit the current setting.

Keywords: Evidence based, Clinical practice guidelines, Caregivers, Palliative care patients, Prevention of pressure ulcer

INTRODUCTION

Pressure ulcers (also referred to as pressure sores, bedsores and pressure injuries) are defined as ‘localised injury to the skin and/or underlying tissue usually over a bony prominence, as a result of pressure or pressure in combination with shear’.[1] Individuals receiving palliative care become less active and their immobility increases as the disease progress. Palliative care patients who spend a lot of time in bed are subject to an increased risk of soft-tissue ulceration.[2] Pressure ulcers are associated with significant morbidity and mortality, causing pain and imposing a considerable burden and distress to patients both physically and psychosocially. The problem goes beyond increased health-care costs to loss of life.[3]

Palliative care patients are most vulnerable to pressure ulcers. Pressure ulcers have been shown to increase the risk of mortality among palliative care patients and decrease the quality of life of these patients. Poor nutrition, urinary and faecal incontinence, poor overall physical health, advanced age, immobility, inadequate hydration, neurosensory deficiency, multiple comorbidities, circulatory abnormalities and mental health predispose people to pressure ulcer formation.[4] Several expert panels have produced guidelines and consensus documents regarding skin changes and pressure ulcers in patients near the end of their lives; however, it is generally accepted that pressure ulcers in patients receiving palliative care are unlikely to heal.[5] The care goals include preventing wounds as much as possible, stabilising and, if possible, progressing towards closure and managing related symptoms to improve individual comfort, well-being and quality of life. Individual or family education between the patient, family and physician or other health professionals will enhance understanding and establish the individual’s and significant other’s desired goals of care.[6]

Thus, it is essential to develop evidence-based guidelines for caregivers of patients receiving palliative care in home-care settings on pressure ulcer prevention, which may play a significant role in preventing pressure ulcers.

There is some evidence that pressure ulcers negatively impact a person’s physical, social, financial and psychological well-being, according to a systematic review of 31 studies.[5] The current guideline development process made an effort to search the literature to provide specific guidelines to the caregivers to prevent pressure ulcers after conducting a need analysis and situational analysis. Using a structured interview schedule, a need assessment study was conducted among 20 caregivers of palliative care patients residing in Olavanna Panchayath, Kozhikode, Kerala. Assessment of knowledge among the caregivers revealed that 50% of them had poor knowledge, 40% had average knowledge, 10% had good knowledge and none had very poor or very good knowledge.[7] The situational analysis revealed no written guidelines for caregivers of palliative care patients on pressure ulcer prevention in the setting. It enables them to take measures to prevent pressure ulcer development among palliative care patients, thereby improving the quality of life of patients receiving home-based palliative care.

Pressure ulcer prevention is a crucial aspect of patient care, arguably the most cost-effective and intuitive way to deal with this potential problem. In our need assessment study, we found that caregivers of palliative care patients do not have adequate knowledge regarding pressure ulcer prevention. It is essential to ensure that caregivers of palliative care patients are empowered to prevent pressure ulcers by providing evidence-based practice guidelines. An attempt is made to develop evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for caregivers of patients receiving home-based palliative care. The objective of the systematic review is to find evidence on pressure ulcer prevention among palliative care patients.

The purpose of the guideline

The purpose of the guideline is to implement evidence-based guidelines for caregivers of palliative care patients on pressure ulcer prevention. This guideline aims to improve the knowledge and practice of caregivers and enables them to take measures to prevent pressure ulcer development among palliative care patients, thereby improving the quality of life of palliative care patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The first step in the guideline development was identifying the evidence. We conducted a systematic review on pressure ulcer prevention and treatment in several electronic databases using a sensitive search strategy. All retrieved references were screened using pre-determined inclusion criteria and preliminary data extraction tables were completed.

In a second step, the retrieved evidence was evaluated, critical appraisals of the evidence were undertaken and the level of evidence was established and refined in the evidence tables. In the next stage, clinical practice guidelines were developed based on the available evidence. It reflects the degree of confidence that a caregiver can place in the recommendation relative to the strength of the supporting evidence, the clinical risks versus benefits, the cost-effectiveness and the system implications.

Criteria for selection of studies

Type of participants

Any palliative care patients who are prone to pressure ulcer development (this may include patients in hospitals, nursing homes, hospice, or home care).

Type of intervention

Inclusion criteria

The following criteria were included in the study:

Any measures used to prevent pressure ulcers among bedridden adult patients were included.

No pressure ulcer at the time of recruitment to the study.

Studies focusing solely on educational interventions that were not accompanied by other interventions.

Exclusion criteria

The following criteria were excluded from the study:

Studies focusing on paediatric age group patients

Studies focusing on wound care and those focused on site-specific (for example, cervical and heel) prevention of pressure ulcers.

Electronic searches

The literature search was conducted on four electronic databases: PubMed, CINHAL, Cochrane and EMBASE database.

Selection of studies

The studies selected were in English language and were with free full text. The studies were selected and assessed for quality using the Cochrane risk assessment tool.

Inclusion criteria

The following criteria were included in the study:

Clinical practice guidelines

Systematic reviews

Randomised controlled trials.

Exclusion criteria

The following criteria were excluded from the study:

Published pilot study findings of RCT

Studies that were not written in English

Studies excluded by the Cochrane risk assessment tool.

Search history

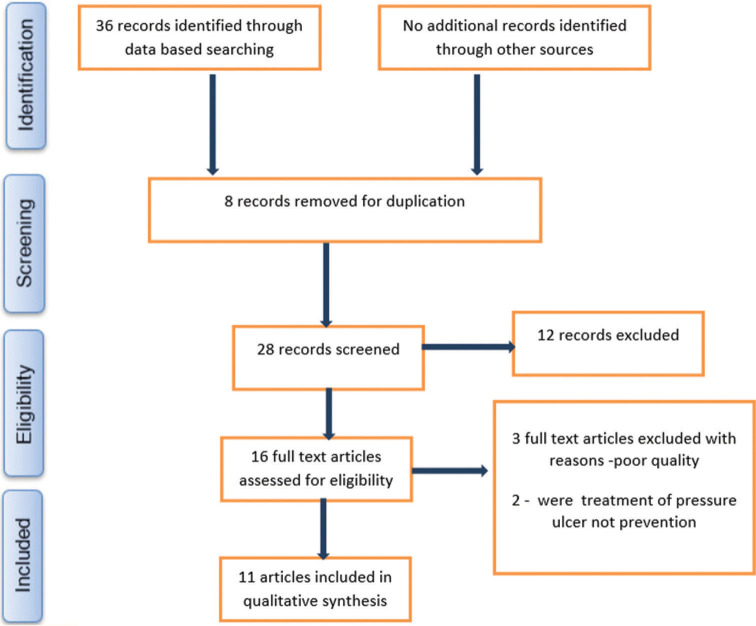

In the first selection phase, studies were screened by assessing titles, abstracts and keywords after removing duplicates. The databases were selected for relevant studies using the following search strategy ‘pressure ulcer[mh] OR pressure ulcer* OR decubitus ulcer* OR pressure sore* OR bed sore* OR skin sore * PU*AND(prevention and control) OR prevent*[tiab] reduction OR reduce* OR prophylactic*AND before-after OR pre-post OR randomised controlled trial[pt] OR randomised controlled trials OR RCT* OR random allocation OR controlled’. The second phase was the full-text review. Full-text studies were selected. Twenty-eight studies were found potentially relevant following the screening of the search results. Twelve studies were not found suitable. Five RCTs did not meet the inclusion criteria. Finally, four systematic reviews and five RCTs and two clinical practice guidelines were included in the study. [Figure 1] depicts the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses 2019 flow diagram of the selection process.

Figure 1:

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses 2019 Flow diagram of the selection process.

Guideline preparation

Clinical Practice Guidelines are systematically derived statements of appropriate care designed to guide health-care providers, caregivers and patients in making decisions for specific clinical condition. They should be based on the best available research evidence and practical experience.

RESULTS

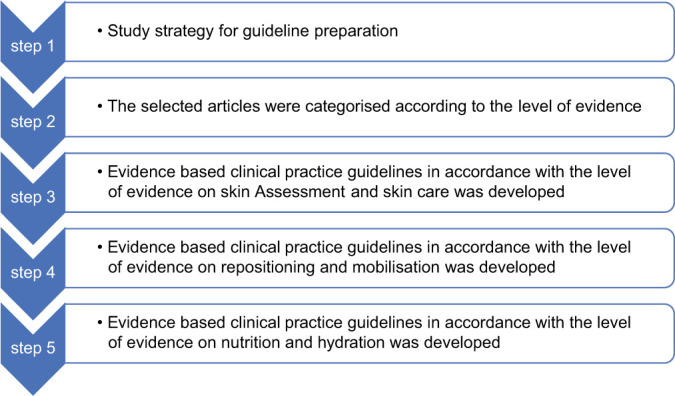

The description of the study strategy for preparation of the guideline is presented in [Table 1 and Figure 2].

Table 1:

Study strategy for guideline preparation.

| Guideline title: Evidence-based guidelines for caregivers of palliative care patients on prevention of pressure ulcer | |

|---|---|

| Guideline Status | Development and implementation |

| Clinical speciality | Community Health Nursing |

| Intended Users | Caregivers of Palliative care patients |

| Guideline objective | To develop evidence-based guidelines for care givers of palliative care patients on prevention of pressure ulcer |

| Target population | Palliative care patients |

| Intervention and practice considered | Various measures taken to prevent pressure ulcer |

| Major outcomes considered | Absence of pressure ulcer |

| Methods used to obtain evidences |

|

| Process of guideline development |

|

| Description of Implementation strategy |

|

Figure 2:

Steps of guideline preparation.

The selected articles were categorised according to the level of evidence and are presented in [Table 2].

Table 2:

Classification of selected articles based on the level of evidence.

| Level of evidence | |

|---|---|

| Category I A |

|

| Category I B |

|

| Category I C |

|

| Category I A |

|

| Category I B |

|

| Category I C |

|

[Table 3] depicts evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for caregivers of palliative care patients on the prevention of pressure ulcers in accordance with the level of evidence on skin assessment and skincare.

Table 3:

Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for caregivers of palliative care patients on prevention of pressure ulcers in accordance with the level of evidence on skin assessment and skincare.

| S. No. | Recommended clinical practice guidelines | Evidence category |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Skin assessment | |

| 1.1 | Conduct skin assessment as soon as possible (but within a maximum of 4 h of reaching home) for all palliative care patients | 1 A, IB, IC |

| 1.2 | Conduct comprehensive skin assessment twice daily | IA, IB, IC |

| 1.3 | Include the following factors in every skin assessment perfusion and oxygenation;

|

I A |

| 1.4 | Consider the potential impact of the following factors on an individual’s risk of pressure ulcer development:

|

1 A |

| 1.5 | Educate care providers on how to undertake a comprehensive skin assessment | 1A |

| 1.6 | Inspect the skin for erythema in individuals identified as being at risk of pressure ulceration | 1A |

| 1.7 | Use the finger method to assess whether the skin is blanchable or by pressing a finger on the erythema for 3 s and blanching is assessed following removal of the finger | 1A |

| 1.8 | When conducting a skin assessment in an individual with darkly pigmented skin and prioritise assessment of:

|

1A,1B |

| 1.9 | Assess localised pain as part of every skin assessment | 1A,1C |

| 1.10 | Avoid positioning the individual on an area of erythema | 1A,1C |

| 1.11 | Use of BRADEN SCALE For Predicting Pressure Sore Risk in Home Care Preventive skincare | IA, IB, IC |

| 2.1 | Keep the skin clean and dry | IA, IB, IC |

| 2.2 | Do not massage or vigorously rub skin that is at risk of pressure ulcer or painful friction massage can cause mild tissue destruction or provoke inflammatory reactions, particularly in frail palliative care patients | IA, IB, IC |

| 2.3 | Develop and implement an individualised continence management plan | IA |

| 2.4 | Cleanse the skin promptly following episodes of incontinence | IA |

| 2.4 | Protect the skin from exposure to excessive moisture with a barrier product to reduce the risk of pressure damage | IA |

| 2.5 | Use a skin moisturiser to hydrate dry skin to reduce the risk of skin damage | 1A, 1B |

| 2.6 | Use support surfaces like Air/water mattress | 1A, 1B |

| 2.7 | Ensure that surfaces of Air/Water or other mattress does not come in direct contact with the skin, which may be able to alter the microclimate by changing the rate of evaporation of moisture and the rate at which heat dissipates from the skin | 1A, 1B |

| 2.8 | Do not apply heating devices (e.g., hot water bottles, heating pads or any modes of moist heat applications directly on skin surfaces of palliative care patients) | IA |

| 2.9 | Consider using silk-like fabrics rather than cotton or cotton-blend fabrics to reduce shear and friction | IA |

[Table 4] represents evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for caregivers of palliative care patients on preventing pressure ulcers in conformity with the level of evidence on repositioning and mobilisation.

Table 4:

Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for caregivers of palliative care patients on prevention of pressure ulcers in conformity with the level of evidence on repositioning and mobilisation.

| S. No. | Recommended clinical practice guidelines | Evidence category |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | Repositioning and mobilisation | |

| 3.1 | Reposition palliative care patients 4–6 hourly at night and 2 hourly in day time | IA |

| 3.2 | Determine repositioning frequency with consideration to the individual’s:

|

1A, 1C |

| 3.3 | Use pressure redistribution support surface mattress like Air/water mattress if required | 1A,1B,1C |

| 3.4 | Encourage patients to do ‘pressure relief lifts’ | 1A |

| 3.5 | Use manual handling aids to reduce friction and shear. Lift — don’t drag — the individual while repositioning to ensure safety of both the patient and the care provider | 1A, 1B |

| 3.6 | Take help from relatives/friends/or volunteers for position changing if required | 1A |

| 3.7 | Avoid positioning the individual directly onto medical devices, such as tubes, drainage systems or other foreign objects | 1A |

| 3.8 | Do not leave the individual on a bedpan longer than necessary | 1A |

| 3.9 | Use the 30° tilted side-lying position (alternately, right side, back, left side) or the prone position if the individual can tolerate this and her/his general condition allows | 1A, 1B, 1C |

| 3.10 | Encourage clients who can reposition themselves to sleep in a 30° to 40° side-lying position or flat in bed if not contraindicated | 1A, 1B |

| 3.11 | Limit head-of-bed elevation to 30° for palliative care patients unless contraindicated by breathing difficulty or feeding and digestive considerations | 1A, 1B, 1C |

| 3.12 | While sitting in bed is necessary, avoid head-of-bed elevation or a slouched position that places pressure and shear on the sacrum and coccyx | 1A, 1B |

| 3.13 | Assess individuals placed in the prone position for evidence of facial pressure ulcers | 1A |

| 3.14 | Provide sitting position which maintains stability and their full range of activities if it is possible | 1A |

| 3.15 | Ensure that the feet are properly supported either directly on the floor, on a footstool or on footrests when sitting (upright) in a bedside chair or wheelchair | 1A |

| 3.16 | Limit the time a patient spends seated in a chair without pressure relief to 30 min | 1A |

[Table 5] portrays evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for caregivers of palliative care patients on the prevention of pressure ulcers in accordance with the level of evidence on nutrition and hydration.

Table 5:

Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for caregivers of palliative care patients on prevention of pressure ulcers consistent with the level of evidence on nutrition and hydration.

| S. No. | Recommended clinical practice guidelines | Evidence category |

|---|---|---|

| 4 | Nutrition | |

| 4.1 | Provide 30–35 k calories/kg body weight for palliative care patients at risk of a pressure ulcer and malnutrition. | 1A |

| 4.2 | Offer 1.25–1.5 g protein/kg body weight daily for palliative care patients at risk of a pressure ulcer and malnutrition | 1A |

| 4.3 | Offer fortified foods and/or high calorie, high protein oral nutritional supplements between meals if nutritional requirements cannot be achieved by dietary intake | 1A |

| 4.4 | Consult a dietician if necessary | 1A |

| 4.5 | Provide/encourage individuals assessed to be at risk of pressure ulcers to consume a balanced diet that includes good sources of vitamins and minerals | 1A,1B |

| 4.6 | Provide/encourage an individual assessed to be at risk of a pressure ulcer to take vitamin and mineral supplements when dietary intake is poor | 1A, 1B |

| 5 | Hydration | |

| 5.1 | Provide and encourage adequate daily fluid intake for hydration to palliative care patients at risk of a pressure ulcer | 1A, 1B |

| 5.2 | Monitor individuals for signs and symptoms of dehydration, including change in weight, skin turgor and urine output | 1A |

| 5.3 | Provide additional fluid for individuals with dehydration, elevated temperature, vomiting, profuse sweating, diarrhoea or heavily exuding wounds | 1A |

DISCUSSION

Skin assessment

It has been shown that pressure injury prevention recommendations based on risk assessments can reduce pressure injuries.[16] This study supports validated pressure injury risk assessment tools, but controversy exists over which tool best suits a given care setting. To add to the heterogeneity of the scales, each assigns a different weight to factors.[17] The Braden Scale has been shown to have good sensitivity (83–100%) and specificity (77–94%) but has poor positive predictive value (around 40%). Therefore, it is an effective risk assessment tool that should be used for comprehensive pressure ulcer prevention.[18]

Pressure and shear injury

It is possible to determine the potential source of pressure and shear injury based on the patient’s posture, activities, mobility, lifestyle and current support surfaces such as sleeping and sitting surfaces. When pressure is exerted near a bony prominence, the risk of pressure injuries increases by 3–5 times.[19] Shear injuries may happen when trying to change the positions of the patient.

Preventive skin care

There is enough evidence on implementing pressure ulcer prevention strategies on the prevalence of PIs in the community for home care patients in community settings. A study conducted in Dubai revealed a significant drop in both prevalence (9.0%) and incidence rate (6.0%) of pressure ulcers, approximately 2.0% after implementing the protocol.[20] Timely and effective skincare using oil or creams reduces the occurrences of pressure ulcers.

Repositioning and mobilisation

Patients’ tissue tolerance, mobility level, medical condition and treatment objectives, as well as their existing support surface, should be considered during the creation of their repositioning protocols.[21] While repositioning, utmost care should be given to the bony prominence; all caregivers must be given training in positioning changing skills. Intensive support services may be required for the patient, or caregivers may need training, respite, or support when lifting and turning the patient.[22]

Nutrition

Nutritional deprivation and insufficient dietary and fluid intake are the key risk factors for developing pressure ulcers and impaired wound healing. There is no specific optimal nutrient intake for wound healing, but there is a documented need for energy, protein, zinc and Vitamins A, C and E in this process. In addition, oral nutritional supplements high in protein have significantly reduced pressure ulcers among at-risk patients.[23]

Hydration

Hydration plays a key role in preserving and repairing skin integrity. Dehydration disturbs cell metabolism and wound healing. A sufficient fluid intake is essential to prevent further skin breakdown and support blood flow to injured tissues.[24]

Support surfaces

A patient cannot be relieved of all pressure. By reducing pressure on one part of the body, we increase pressure elsewhere. Therefore, pressure redistribution should be optimised for best results. An effective method of redistributing pressure is the use of support surfaces. According to a review of the literature, there is sufficient evidence that specially designed support surfaces effectively prevent the formation of pressure ulcers.[25]

Implication

Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines have implications for practice in the wider world of palliative care, especially in the home care setting. These guidelines are expected to have the potential to create palliative care champions among the caregivers. Positive results will have the ability to stimulate and percolate additional quality improvement projects in the future. It may also improve the morale of patients, family members and caregivers. When caregivers can see the positive result of their hard work with evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, they are more likely to be engaged in the future projects. The field of palliative care can benefit from positive results in patient care areas. These guidelines may lead to more evidence-based practices for providing quality patient care. This will help to ensure that the patients are being provided with the most appropriate intervention based on research and evidence and the caregivers will have support and direction in providing quality care.

CONCLUSION

The evidence-based nursing practice integrates the best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values. The guideline preparation was done through a series of steps based on the Rosswurm and Larrabee model.[26] Evidence-based nursing practice leads to a problem-solving approach which is existing or anticipated. The guideline preparation has considered evidence, expertise and patient preferences. The guidelines were prepared through an extensive review through systematic review, RCT and evaluation of other guidelines followed in different settings and modified to suit the current setting. The findings of this review will aid in selecting appropriate preventive strategies for preserving the dignity and comfort of patients. Furthermore, pressure ulcers caused by unavoidable disease states can be accepted and treated appropriately, rather than being seen as a failure of care.

Footnotes

How to cite this article: Antony L, Thelly AS, Mathew JM. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for caregivers of palliative care patients on the prevention of pressure ulcer. Indian J Palliat Care 2023;29:75-81.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as there are no patients in this study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

Ms. Anu Savio Thelly is one of the Section Associate Editors.

References

- 1.National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel. Available from: https://npiap.com/404.aspx?404 http://www.npuap.org:80/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Updated-10-16-14-Quick-Reference-Guide-DIGITAL-NPUAP-EPUAPPPPIA-16Oct2014.pdf [Last accessed on 2022 Mar 01]

- 2.Fragala G. Bed care for patients in palliative settings: Considering risks to caregivers and bed surfaces. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2015;21:66–70. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2015.21.2.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brem H, Maggi J, Nierman D, Rolnitzky L, Bell D, Rennert R, et al. High cost of stage IV pressure ulcers. Am J Surg. 2010;200:473–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.VanDenKerkhof EG, Friedberg E, Harrison MB. Prevalence and risk of pressure ulcers in acute care following implementation of practice guidelines: Annual pressure ulcer prevalence census 1994-2008. J Healthc Qual. 2011;33:58–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1945-1474.2011.00127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. EPUAP. Available from: http://www.epuap.org [Last accessed on 2022 Mar 01]

- 6.Pressure Ulcers in Individuals Receiving Palliative Care: A: Advances in Skin and Wound Care. Available from: https://journals-lww-com.surrey.idm.oclc.org/aswcjournal/fulltext/2010/02000/pressure_ulcers_in_individuals_receiving.7.aspx [Last accessed on 2022 Mar 02] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Antony L, Thelly AS. Knowledge on prevention of pressure ulcers among caregivers of patients receiving home-based palliative care. Indian J Palliat Care. 2022;28:75–9. doi: 10.25259/IJPC_84_2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunk AM, Carville K. The international clinical practice guideline for prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers/injuries. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72:243–4. doi: 10.1111/jan.12614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gorecki C, Brown JM, Nelson EA, Briggs M, Schoonhoven L, Dealey C, et al. Impact of pressure ulcers on quality of life in older patients: A systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1175–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soban LM, Hempel S, Munjas BA, Miles J, Rubenstein LV. Preventing pressure ulcers in hospitals: A systematic review of nurse-focused quality improvement interventions. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2011;37:245–52. doi: 10.1016/S1553-7250(11)37032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sullivan N, Schoelles KM. Preventing in-facility pressure ulcers as a patient safety strategy: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:410–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-5-201303051-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tubaishat A, Papanikolaou P, Anthony D, Habiballah L. Pressure ulcers prevalence in the acute care setting: A systematic review, 2000-2015. Clin Nurs Res. 2018;27:643–59. doi: 10.1177/1054773817705541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergstrom N, Horn SD, Rapp M, Stern A, Barrett R, Watkiss M, et al. Preventing pressure ulcers: A multisite randomized controlled trial in nursing homes. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2014;14:1–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Webster J, Coleman K, Mudge A, Marquart L, Gardner G, Stankiewicz M, et al. Pressure ulcers: Effectiveness of risk-assessment tools. A randomised controlled trial (the ULCER trial) BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20:297–306. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.043109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mistiaen P, Achterberg W, Ament A, Halfens R, Huizinga J, Montgomery K, et al. Cost-effectiveness of the Australian Medical Sheepskin for the prevention of pressure ulcers in somatic nursing home patients: Study protocol for a prospective multi-centre randomised controlled trial (ISRCTN17553857) BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:4. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moore Z, Cowman S, Conroy RM. A randomised controlled clinical trial of repositioning, using the 30° tilt, for the prevention of pressure ulcers. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:2633–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beeckman D, Serraes B, Anrys C, Van Tiggelen H, Van Hecke A, Verhaeghe S. A multicentre prospective randomised controlled clinical trial comparing the effectiveness and cost of a static air mattress and alternating air pressure mattress to prevent pressure ulcers in nursing home residents. Int J Nurs Stud. 2019;97:105–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lyder CH, Ayello EA. In: Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Hughes RG, editor. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US; 2008. Pressure ulcers: A patient safety issue. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.International Review Pressure Ulcer Prevention Pressure Shear Friction and Microclimate in Context Wounds International. Available from: https://www.woundsinternational.com/resources/details/international-review-pressure-ulcer-prevention-pressure-shear-friction-and-microclimate-context [Last accessed on 2022 Mar 20]

- 20.Prasad S, Hussain N, Sharma S, Chandy S, Kurien J. Impact of pressure injury prevention protocol in home care services on the prevalence of pressure injuries in the Dubai community. Dubai Med J. 2020;3(3):99–104. doi: 10.1159/000511226. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.FROM THE NPUAP: Pressure Ulcer Guidelines: Minding the Gaps When Developing New Guidelines Article Nursing Center. Available from: https://www.nursingcenter.com/journalarticle?Article_ID=790732andJournal_ID=54015andIssue_ID=790723 [Last accessed on 2022 Mar 02] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Bluestein D, Javaheri A. Pressure ulcers: Prevention, evaluation, and management. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78:1186–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raffoul W, Far MS, Cayeux MC, Berger MM. Nutritional status and food intake in nine patients with chronic low-limb ulcers and pressure ulcers: Importance of oral supplements. Nutrition. 2006;22:82–8. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saghaleini SH, Dehghan K, Shadvar K, Sanaie S, Mahmoodpoor A, Ostadi Z. Pressure ulcer and nutrition. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2018;22:283–9. doi: 10.4103/ijccm.IJCCM_277_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.LeLaurin JH, Shorr RI. Preventing falls in hospitalized patients: State of the science. Clin Geriatr Med. 2019;35:273–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2019.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosswurm MA, Larrabee JH. A model for change to evidence-based practice. Image J Nurs Sch. 1999;31:317–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1999.tb00510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]