Abstract

Objective

Hypoglycemia is a sporadic and serious adverse reaction of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) due to its sulfonylurea-like effect. This study explored the clinical characteristics, risk factors, treatment, and prognosis of TMP-SMX-induced hypoglycemia.

Methods

Case reports and series of TMP-SMX-induced hypoglycemia were systematically searched using Chinese and English databases. Primary patient and clinical information were extracted for analysis.

Results

A total of 34 patients were reported from 31 studies (16 males and 18 females). The patients had a median age of 64 years (range 0.4-91), and 75.8% had renal dysfunction. The median duration of a hypoglycemic episode was six days (range 1-20), and the median minimum glucose was 28.8 mg/dL (range 12-60). Thirty-two patients (97.0%) showed neuroglycopenic symptoms, with consciousness disturbance (30.3%) and seizure (24.2%), sweating (18.2%), confusion (15.2%), asthenia (12.1%) being the most common symptoms. Fifteen patients (44.1%) had elevated serum insulin levels, with a median of 31.8 μU/mL (range 3-115.3). C-peptide increased in 13 patients (38.2%), with a median of 7.7 ng/mL (range 2.2-20). Complete recovery from symptoms occurred in 88.2% of patients without sequelae. The duration of hypoglycemia symptoms was 8 hours to 47 days after the intervention. Interventions included discontinuation of TMP-SMX, intravenous glucose, glucagon, and octreotide.

Conclusion

Hypoglycemia is a rare and serious adverse effect of TMP-SMX. Physicians should be aware of this potential adverse effect, especially in patients with renal insufficiency, increased drug doses, and malnutrition.

Keywords: hypoglycemia, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, pneumocystis pneumonia, seizure, neuroglycopenic symptoms

Introduction

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX), AKA co-trimoxazole, was approved in 1968 for treating urinary tract infections, uncomplicated sinusitis, and chronic bronchitis (1). Oral and intravenous preparations are manufactured from a fixed ratio of 1:5 of trimethoprim to sulfamethoxazole. TMP-SMX is also the therapy for treating Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP) (2).

The most common adverse reactions of TMP-SMX are rash, allergic reaction, gastrointestinal discomfort, hyperkalemia, nephrotoxicity, and pancytopenia (3). In rare cases, TMP-SMX can also cause severe hypoglycemia that is often overlooked, leading to fatal outcomes. Current knowledge about TMP-SMX-induced hypoglycemia is based primarily on case reports, and the specific clinical features are unclear. Here, we discuss the clinical features, risk factors, treatment, and prognosis of hypoglycemia induced by TMP-SMX to provide a basis for the rational use of TMP-SMX.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

Case reports, case series, and clinical studies of cotrimoxazole-induced hypoglycemia were searched from Chinese and English databases, including Wanfang, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, China Science and Technology Journal Database, PubMed, OVID, Web of Science, Embase, and Cochrane Library. The search period was limited from January 1, 1968, to July 31, 2022. The searches were performed using subject and free words, including “trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole” [MeSH] OR “trimethoprim” [MeSH] OR “sulfamethoxazole” [MeSH] OR “SMX” [MeSH] OR “TMP” [MeSH] OR “co-trimoxazole” [MeSH] AND “hypoglycemia” [MeSH] OR “blood glucose” [MeSH] OR “glycaemia” [MeSH]. There was no language restriction. Mechanistic studies, animal studies, reviews, and duplicate reports were excluded.

Data extraction

The following data were extracted using self-designed tables: age, sex, underlying diseases, concomitant medications, indications, dosage regimens, risk factors, clinical symptoms and signs, laboratory tests (blood glucose, insulin, C-peptide, liver function, renal function), imaging studies, treatment, and prognosis.

Diagnostic criteria for hypoglycemia

According to the latest diagnostic criteria for hypoglycemia of the American Diabetes Association, hypoglycemia can be diagnosed when the blood glucose level of diabetic patients is ≤70 mg/dL (≤3.9 mmol/L). In contrast, the blood sugar of non-diabetic patients is less than 55 mg/dL (3.0 mmol/L) (4).

Statistical analyses

SPSS Statistics 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Enumeration and measurement data were represented by n (%) and the median value (range, minimum and maximum values), respectively.

Results

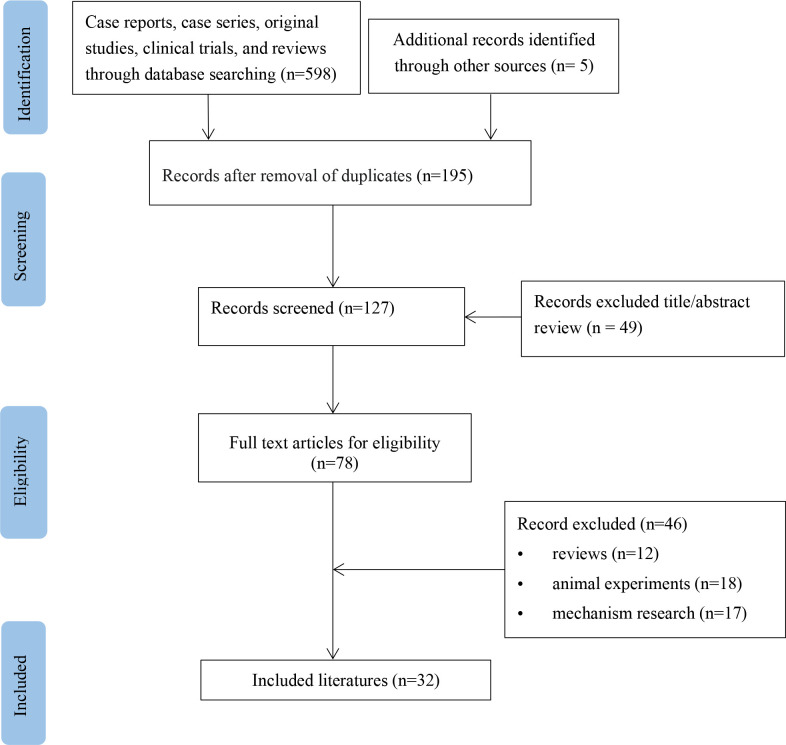

A flow diagram for the study is provided in Figure 1 . According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 34 patients from 32 studies were included ( Table 1 ) (5–36). The basic information about these patients is summarized in Table 2 . These patients (16 men and 18 women) were mainly from North America (38.2%), Europe (44.1%), and Asia (7.6%), with a median age of 64 years (range 0.4-91). Medical history was available in 33 patients (97.1%), including 9 (27.3%) with type 2 diabetes and 2 (6.1%) with hepatitis. Ten patients (29.4%) had malnutrition. Twenty-two patients (43%) were taking concomitant drugs, including 13 (38.2%) taking drugs that could cause hypoglycemia, such as beta-adrenergic antagonists, quinolones, angiotensin-converting agent enzyme inhibitors (ACEI), propoxyphene, and hypoglycemic medications. The median daily dose of sulfamethoxazole is 3,200 mg (range 400-9,600). The median duration of TMP-SMX treatment before the hypoglycemia episode was six days (range 1-20).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study selection process for reported cases of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-induced hypoglycemia.

Table 1.

Summary of clinical information of 34 patients.

| reference | age/sex | indication | daily dose (mg/d) | duration(d) | symptoms | serum glucose (mg/dL) | Insulin (μU/ml) | C-peptide (ng/mL) | serum creatinine (mg/dL) | Management |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 65/f | UTI | 320/1600 po | 10 | seizure, dyspnea, lethargic | 27 | 36 | na | 6.1 | discontinued, dextrose iv |

| 6 | 63/m | pyogenic arthritis | 960/4800 po; 320/1600 po | 5/na | seizures, mental status changes | 26 | 58.7 | na | HD | dose decreased |

| 7 | 85/f | UTI | 320/1600 po | 7 | confusion, loss of consciousness | 24 | 3 | na | 1.3 | discontinued, dextrose iv |

| 7 | 74/f | UTI | 320/1600 po | na | loss of consciousness | 12 | 6 | na | 8.2 | discontinued, dextrose iv |

| 8 | 69/f | UTI | na | 2 | nausea, vomiting, weakness, slurred speech, numbness | 48 | na | na | normal | discontinued, dextrose iv |

| 9 | 62/m | PCP | 960/4800 po | 5 | consciousness disturbance | 20 | 34.5 | na | 3.3 | discontinued |

| 10 | 64/m | PCP | 1280/6400 iv | 2 | loss of consciousness | 36 | na | na | 9.5 | dextrose iv |

| 11 | 34/m | PCP | na | 6 | stuporous | 18 | 12 | ↑ | normal | discontinued, dextrose iv |

| 12 | 88/f | UTI | 320/1600 po | 4 | GTCS, incoherence, confusion | 33 | na | NA | 1.2 | discontinued, dextrose iv |

| 13 | 19/f | na | 320/1600 po | 1 | confusion | 17 | na | NA | PD | dextrose iv |

| 14 | 36/m | PCP | 960/4800 iv, 1920/9600 po |

8 | tremor, loss of consciousness, seizure, sweating | 28.8 | na | 4.3 | 3.6 | discontinued, dextrose iv,diazepam |

| 15 | 54/f | PCP | 1280/6400 | 5 | neuroglycopenic symptoms | 36 | 24.2 | 7.7 | normal | discontinued, dextrose iv |

| 16 | 73/m | HAP | 1280/6000 iv;600/3000 iv | 6/9 | asymptomatic | 22 | na | na | 5.1 | discontinued, dextrose iv, low-dose re-challenge |

| 17 | 91/f | UTI | 640/3200 po | 7 | decreased level of consciousness | 34 | na | na | 1.7 | discontinued |

| 18 | 41/m | PCP | 640/3200 po | 6 | tremor, sweating, disorienting, unresponsive | 18 | 30.2 | 12.6 | 1.4 | discontinued |

| 19 | 5m/f | PCP | 20/100 mg/kg per d | 3 | generalized convulsion | 18 | 16.4 | 4.88 | normal | dose decreased, diazoxide |

| 20 | 46/m | PCP | 1280/6400 po | 18 | GTCS, altered state of consciousness, falls | 28.8 | na | na | 2 | discontinued, dextrose iv |

| 21 | 76/m | UTI | 160/800 | 5 | symptomatic hypoglycemia, inability to speak | 34 | na | na | 2 | discontinued, dextrose iv |

| 22 | 44/f | PCP | 1920/9600 iv | 7 | sweating, asthenia, dizziness | 59 | 40 | na | normal | continued, dextrose iv |

| 22 | 24/m | PCP | 960/4800 iv | 20 | sweating, asthenia, confusion, nausea, dizziness | 56 | 80 | na | normal | discontinued, dextrose iv |

| 23 | 83/m | prophylaxis | 160/800 | na | loss of muscle tone, pale skin and mucous membranes | 28 | 3.2 | 2.2 | 1.7 | discontinued, dextrose iv |

| 24 | 56/f | PCP | no | 5 | coma | 30.6 | 2ULN | 2ULN | CKD 5 | discontinued, dextrose iv |

| 25 | 52/f | prophylaxis | 80/400 | 7 | dizziness, hunger, headaches, sweating. | 30.6 | 41.1 | 6.1 | > 60 * | continued, oral sugar |

| 26 | 60/f | UTI | 160/800 | 3 | tremor, sweating, fatigue | 60 | na | na | normal | discontinued |

| 27 | 71/m | PCP | 1120/5600 | 11 | coma, acute neurological deterioration, nervous breakdown, hypothermia | 24 | na | na | 3.2 | discontinued, dextrose iv |

| 28 | 69/m | PCP | 960/4800 | 4 | Tonic clonic seizure | 28.8 | 95.9 | 12.8 | AKI | discontinued, dextrose iv, glucagon |

| 29 | 18/f | prophylaxis | 80/400 po | 2 | na | 43.2 | 8.1 | 11.7 | 0.5 | discontinued, dextrose iv |

| 30 | 85/m | UTI | 320/1600 po | 7 | pale, altered state of consciousness | 35 | 8.8 | 4.57 | 1.79 | discontinued, dextrose iv |

| 31 | 75/f | PCP | 96 mg/kg/day | 10 | lost consciousness | 20 | na | na | 53.7 * | discontinued, oral sugar, low-dose re-challenge |

| 32 | 64/m | PCP | 1280/6400 po | 5 | delirious, spoke nonsense words, displayed dancing arms, deliration | 30.6 | 115.3 | 19.55 | 49.67* | dose decreased |

| 33 | 73/m | bacteremia | 160/800 2d, 960/4800 po | 8 | lethargy, visual hallucinations | 45 | 31.8 | 4.5 | 1.3 | Discontinued, hydrocortisone and dextrose iv, intramuscular glucagon and octreotide. |

| 34 | 62/f | Cerebral toxoplasmosis | 320/1600 | 6 | GTCS | 21 | 99 | 20 | na | discontinued, dextrose iv, glucagon |

| 35 | 64/f | PCP | no | na | confusion | 21.6 | no | 15.5 | AKI | discontinued, dextrose iv, glucagon |

| 36 | 79/f | UTI | 320/1600 po | 6 | consciousness disorder, coma, wandering, sweating | 28.8 | na | na | na | discontinued, dextrose iv |

AKI, acute kidney injury; CKD, Chronic kidney disease; GTCS, generalized tonic clonic seizure; HD, hemodialysis; na, not applicable; PCP, Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia; PD, peritoneal dialysis; iv, intravenous; ULN, upper limit of normal value; UTI, urinary tract infection.

*Represents estimated glomerular filtration rate (mL/min).

AKI, acute kidney injury; CKD, Chronic kidney disease; GTCS, generalized tonic clonic seizure; HD, hemodialysis; na, not applicable; PCP, Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia; PD, peritoneal dialysis; iv, intravenous; ULN, upper limit of normal value; UTI, urinary tract infection.

*Represents estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Table 2.

Summary of basic information of 34 patients.

| Parameter | Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | F M |

18 (52.3%) 16 (47.1%) |

| Age, years | 64 (0.4,91) b | |

| Country | USA UK Canada Italy Japan, Turkey, France, China Portugal, Iran, Israel, Spain, Barbados |

8 (23.5%) 6 (17.7%) 4 (11.8%) 3 (8.8%) 2 (5.9%) 1 (2.9%) |

| Onset time (days) (30) a | 6 (1,20) b | |

| Daily dose (mg) (29) a | 3200 (400,9600) b | |

| Indication (33)a | PCP UTI prophylaxis HAP, pyogenic arthritis, bacteremia cerebral toxoplasmosis |

16 (48.5%) 10 (30.3%) 3 (9.1%) 1 (3.0%) |

| Medical history (33)a | type 2 diabetes autoimmune disease AIDS hypertension cardiovascular disease hematological tumor cancer nervous system disease, nephrolithiasis, osteoporosis, kidney transplant, COPD epilepsy, hypothyroidism |

9 (27.3%) 8 (24.2%) 6 (18.2%) 4 (12.1%) 4 (12.1%) 3 (6.1%) 3 (6.1%) 2 (6.1%) 2 (6.1%) 1 (3.0%) |

| Combination therapy (22) a | prednisone antibiotics hypoglycemic drugs diuretics propoxyphene H2 blockers antihypertensive drugs beta blocker Immunosuppressant antiviral drugs proton pump inhibitor |

6 (27.3%) 5 (22.7%) 5 (22.7%) 5 (22.7%) 4 (18.2%) 4 (18.2%) 4 (18.2%) 3 (13.6%) 3 (13.6%) 3 (13.6%) 2 (9.1%) |

PCP, Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia; UTI, urinary tract infection; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HAP, hospital acquired pneumonia; AIDS, acquired immune deficiency syndrome.

a Represents the number of patients out of 34 in whom information regarding this particular parameter was provided.

b Median (minimum-maximum).

Clinical symptoms

Thirty-three patients had documented clinical symptoms, of which 32 (97.0%) developed neurological hypoglycemia symptoms and 1 (3.0%) had asymptomatic hypoglycemia. The most common symptoms during hypoglycemia episodes were consciousness disturbance (30.3%) and seizure (24.2%), followed by sweating (18.2%), confusion (15.2%), asthenia (12.1%), tremor (9.1%), dizziness (9.1%), coma (9.1%) and lethargic (9.1%). Other rare symptoms and signs include dyspnea, hypothermia, visual hallucinations, and numbness. Details are shown in Table 3 .

Table 3.

Summary of clinical symptoms and laboratory tests of 34 patients.

| Parameter | Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Symptoms and signs (33)a | asymptomatic neuroglycopenic symptoms |

1 (3.0%) 32 (97.0%) |

| consciousness disturbance seizure sweating confusion asthenia tremor dizziness coma lethargic pale skin and mucous membranes nausea deliration other rare symptoms: dyspnea, slurred speech, numbness, incoherence, inability to speak, disorienting, nonresponsive, fall, loss of muscle tone, hunger, hypothermia, dehydration, visual hallucinations, spoke nonsense words, displayed dancing arms, headaches |

10 (30.3%) 8 (24.2%) 6 (18.2%) 5 (15.2%) 4 (12.1%) 3 (9.1%) 3 (9.1%) 3 (9.1%) 3 (9.1%) 2 (6.1%) 2 (6.1%) 2 (6.1%) 1 (3.0%) |

|

| Serum glucose (mg/dL) | 28.8 (12,60) b | |

| Insulin (μU/mL) (19)a | 31.8 (3,115.3) b | |

| elevated normal |

15 (78.9%) 4 (21.1%) |

|

| C-peptide (ng/mL) (13)a | elevated | 13 (100%) 7.7(2.2,20) b |

| Renal (33) a | normal renal impairment* |

8 (24.2%) 25 (75.8%) |

| Liver (22)a | hepatitis normal |

2 (9.1%) 20 (90.1%) |

* Renal impairment were categorized according to their estimated creatinine clearance at screening: normal renal function (≥ 90 mL/min/1.73 m2), mild impairment (60–89 mL/min/1.73 m2), moderate impairment (30–59 mL/min/1.73 m2) and severe impairment (15–29 mL/min/1.73 m2).

a Represents the number of patients out of 34 in whom information regarding this particular parameter was provided.

b Median (minimum-maximum).

Laboratory test

The median lowest serum glucose measured was 28.8 mg/dL (range 12-60). Of the 19 patients measured, 15 (78.9%) had elevated serum insulin levels, with a median of 31.8 μU/mL (range 3-115.3). C-peptide levels increased in all 13 measured patients, with a median of 7.7 ng/mL (range 2.2-20). Renal impairment occurred in 25 of 33 patients (75.8%), and hepatitis occurred in 2 of 22 patients (9.1%). Details are shown in Table 3 .

Treatment and prognosis

TMP-SMX was immediately discontinued in 27 patients (79.4%), continued in 2 patients (5.9%), and the dose decreased in 3 patients (8.8%). One case (2.9%) did not describe whether treatment was discontinued or changed information. The management of TMP-SMX was not described in one patient. Thirty patients (88.2%) received intravenous glucose immediately, 2 (5.9%) received oral glucose, and 1 (2.9%) received carbohydrate supplementation. In addition, four patients (11.8%) received glucagon, and one each (2.9%) received octreotide, diazoxide, hydrocortisone, and diazepam, respectively. Two patients (5.9%) were rechallenged with TMP-SMX at a lower dose and did not experience hypoglycemia. Despite continuous intravenous glucose injection, 11 patients (42.8%) had persistent hypoglycemia within 24 hours, 7 (26.9%) had it for 28-72 hours, and 2 (7.7%) had it for 24 days and 47 days, respectively. Ultimately, 30 patients (88.2%) recovered completely without neurological sequelae, and 1 (2.9%) did not report an outcome. Three patients (8.8%) died of hypoglycemia, potential multiple myeloma and other causes, respectively. Details are shown in Table 4 .

Table 4.

Summary of treatment and prognosis of 34 patients.

| Parameter | Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment | discontinued continued dose decreased na dextrose intravenously oral sugar carbohydrates supplements glucagon octreotide diazoxide hydrocortisone diazepam low-dose re-challenge |

27 (79.4%) 2 (5.9%) 3 (8.8%) 2 (5.9%) 30 (88.2%) 2 (5.9%) 1 (2.9%) 4 (11.8%) 1 (2.9%) 1 (2.9%) 1 (2.9%) 1 (2.9%) 2 (5.9%) |

| Duration of hypoglycemia (26)a | rapid 8-24h 24-48h 48-72h 24-47d |

1 (3.8%) 10 (38.4%) 7 (26.9%) 6 (23.1%) 2 (7.7%) |

| Outcome | recovery death na |

30 (88.2%) 3 (8.8%) 1 (2.9%) |

na, not applicable.

a Represents the number of patients out of 34 in whom information regarding this particular parameter was provided.

Discussion

Hypoglycemia is characterized by low plasma glucose levels and ultimately leads to the clinical syndrome of neurological hypoglycemia with numerous etiologies (37). Patients with insulinoma, paraneoplastic hypoglycemia, hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia syndrome, alcohol, infection, hypocortisolism, liver dysfunction, malnutrition, renal insufficiency, toxins, and drugs are associated with hypoglycemia (38). A variety of medications can induce exacerbated hypoglycemia, including acetaminophen, beta-blockers, pentamidine, ACEI, and propoxyphene (39, 40). The presence of these risk factors increases the risk of hypoglycemia in patients receiving TMP-SMX (3).

In our study, TMP-SMX -induced hypoglycemia occurred primarily in patients over 60 years of age. In these patients, the median onset of hypoglycemia was seven days. Symptoms of hypoglycemia include neurogenic (autonomic) or neuroglycopenic symptoms. The clinical signs of TMP-SMX-induced hypoglycemia are mainly neurogenic hypoglycemia. In patients with TMP-SMX-induced hypoglycemia, other factors predisposing to hypoglycemia include the use of hypoglycemic drugs (e.g., beta-blockers, ACEI, acetaminophen, propoxyphene), liver dysfunction, malnutrition, and renal insufficiency. Renal insufficiency was probably the most common risk factor for TMP-SMX-induced hypoglycemia, and 74% of patients had renal insufficiency at the time of hypoglycemia in our study. Although our retrospective analysis identified risk factors for co-trimoxazole-induced hypoglycemia, the incidence of this complication could not be determined.

About 10% to 30% of trimethoprim is metabolized to the inactive form, and the remainder is excreted unchanged in the urine. Sulfamethoxazole is mainly metabolized in the liver, and about 30% is excreted unchanged in the urine. In normal renal function, the half-life of TMP-SMX is 8-15 hours, while in end-stage renal disease, the half-life can be extended to 20-50 hours (41). Therefore, the dose of TMP-XSM should be adjusted when creatinine clearance is below 30 mL/min. This implies assessing the patient’s baseline kidney and liver function before starting co-trimoxazole is crucial. Both components of TMP-SMX can significantly affect the metabolism of concomitantly administered drugs. The trimethoprim component selectively inhibits CYP2C8, while sulfamethoxazole inhibits CYP2C9 (42). Trimethoprim may increase the risk of hypoglycemia by inhibiting repaglinide liver metabolism (21). This suggests that co-trimoxazole should be used with caution in the case of concurrent oral hypoglycemic agents.

The occurrence of hypoglycemia appears to be dose-related. Three patients had no additional hypoglycemia symptoms that occurred when the dose of co-trimoxazole was adjusted according to renal function (6, 19, 32). Hypoglycemia caused by TMP-SMX may be related to sulfamethoxazole. The possible mechanism is the structural similarity between sulfamethoxazole and sulfonylureas (10, 43). Sulfamethoxazole is postulated to increase insulin secretion, a theory supported by elevated insulin and C-peptide levels in more than 79% of patients in our study.

Currently, there is no optimal management plan for TMP-SMX-induced hypoglycemia. Opinions on continuous administration of TMP-SMX are inconsistent after hypoglycemia. The discontinuation of TMP-SMX is safe and eliminates the risk of recurrent hypoglycemia. Limited data suggest that some patients may be successfully re-challenged at lower doses. TMP-SMX remains the only option when other effective alternatives for severe PCP, such as pentamidine and primaquine, are unavailable. Intravenous glucose is needed for hypoglycemia to prevent seizures, coma, and death. Octreotide, a somatostatin analog, reduces calcium influx through voltage-gated channels in beta islet cells, thus reducing pancreatic calcium-mediated insulin release. It is commonly used in the treatment of sulfonylurea overdose (44, 45). Glucagon may be used as a treatment option in hypoglycemia refractory to glucose administration. Despite appropriate treatment, symptoms persisted for more than 8 hours in 95% of patients in our analysis.

Conclusion

Clinicians should be aware of this rare but life-threatening hypoglycemia complication of co-trimoxazole, especially in patients with multiple risk factors. Early interventions in the event of hypoglycemia during TMP-SMX treatment are essential to prevent severe adverse outcomes. Blood glucose monitoring is feasible in patients taking long-term co-trimoxazole.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

LS and CW conceived of the presented idea. CW, WF, Zl and LS wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding Statement

This research was supported by the Inclusive Policy and Innovative Environment Construction Program of Hunan Province(Grant numbers: 2021SK53707).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1. Cockerill FR, Edson RS. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Mayo Clin Proc (1991) 66(12):1260–9. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)62478-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Maschmeyer G, Helweg-Larsen J, Pagano L, Robin C, Cordonnier C, Schellongowski P, et al. ECIL guidelines for treatment of pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in non-HIV-infected haematology patients. J Antimicrob Chemother (2016) 71(9):2405–13. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ho JM, Juurlink DN. Considerations when prescribing trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. CMAJ. (2011) 183(16):1851–8. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.111152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cryer PE, Axelrod L, Grossman AB, Heller SR, Montori VM, Seaquist ER, et al. Evaluation and management of adult hypoglycemic disorders: An endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2009) 94(3):709–28. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Arem R, Garber AJ, Field JB. Sulfonamide-induced hypoglycemia in chronic renal failure. Arch Intern Med (1983) 143(4):827–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.143.4.827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Frankel MC, Leslie BR, Sax FL, Soave R. Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole-related hypoglycemia in a patient with renal failure. N Y State J Med (1984) 84(1):30–1. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)49528-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Poretsky L, Moses AC. Hypoglycemia associated with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole therapy. Diabetes Care (1984) 7(5):508–9. doi: 10.2337/diacare.7.5.508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Baciewicz AM, Swafford WB., Jr. Hypoglycemia induced by the interaction of chlorpropamide and co-trimoxazole. Drug Intell Clin Pharm (1984) 18(4):309–10. doi: 10.1177/106002808401800407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fukuda H, Ohiwa T, Kusano Y, Ohbu S, Niikura H, Terada H. A case of hypoglycemic attack associated with sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim. Nihon Naika Gakkai Zasshi. (1987) 76(12):1887–8. doi: 10.2169/naika.76.1887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ryan DW, Oyston J. Sulphonylureas and hypoglycaemia. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). (1988) 296(6632):1328. doi: 10.1136/bmj.296.6632.1328-a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schattner A, Rimon E, Green L, Coslovsky R, Bentwich Z. Hypoglycemia induced by co-trimoxazole in AIDS. BMJ. (1988) 297(6650):742. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6650.742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McKnight JT, Gaskins SE, Pieroni RE, Machen GM. Severe hypoglycemia associated with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole therapy. J Am Board Fam Pract (1988) 1(2):143–5. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.1.2.143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mansoor GA, Nicholson GD. Hypoglycaemia in chronic renal failure. West Indian Med J (1992) 41(1):41–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Johnson JA, Kappel JE, Sharif MN. Hypoglycemia secondary to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole administration in a renal transplant patient. Ann Pharmacother. (1993) 27(3):304–6. doi: 10.1177/106002809302700309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hekimsoy Z, Biberoğlu S, Cömlekçi A, Tarhan O, Mermut C, Biberoğlu K. Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole-induced hypoglycemia in a malnourished patient with severe infection. Eur J Endocrinol (1997) 136(3):304–6. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1360304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee AJ, Maddix DS. Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole-induced hypoglycemia in a patient with acute renal failure. Ann Pharmacother. (1997) 31(6):727–32. doi: 10.1177/106002809703100611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mathews WA, Manint JE, Kleiss J. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-induced hypoglycemia as a cause of altered mental status in an elderly patient. J Am Board Fam Pract (2000) 13(3):211–2. doi: 10.3122/15572625-13-3-211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hughes CA, Chik CL, Taylor GD. Cotrimoxazole-induced hypoglycemia in an HIV-infected patient. Can J Infect Dis (2001) 12(5):314–6. doi: 10.1155/2001/848946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gonc EN, Turul T, Yordam N, Ersoy F. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole induced prolonged hypoglycemia in an infant with MHC class II deficiency: Diazoxide as a treatment option. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab (2003) 16(9):1307–9. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2003.16.9.1307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Strevel EL, Kuper A, Gold WL. Severe and protracted hypoglycaemia associated with co-trimoxazole use. Lancet Infect Dis (2006) 6(3):178–82. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70414-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Roustit M, Blondel E, Villier C, Fonrose X, Mallaret MP. Symptomatic hypoglycemia associated with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and repaglinide in a diabetic patient. Ann Pharmacother. (2010) 44(4):764–7. doi: 10.1345/aph.1M597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nunnari G, Celesia BM, Bellissimo F, Tosto S, La Rocca M, Giarratana F, et al. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-associated severe hypoglycaemia: A sulfonylurea-like effect. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci (2010) 14(12):1015–8. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2010.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Caro J, Navarro-Hidalgo I, Civera M, Real JT, Ascaso JF. Severe, long-term hypoglycemia induced by co-trimoxazole in a patient with predisposing factors. Endocrinol Nutr (2012) 59(2):146–8. doi: 10.1016/j.endonu.2011.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Forde DG, Aberdein J, Tunbridge A, Stone B. Hypoglycaemia associated with co-trimoxazole use in a 56-year-old Caucasian woman with renal impairment. BMJ Case Rep (2012) 2012:bcr2012007215. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2012-007215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Senanayake R, Mukhtar M. Cotrimoxazole-induced hypoglycaemia in a patient with churg-strauss syndrome. Case Rep Endocrinol (2013) 2013:415810. doi: 10.1155/2013/415810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Eshraghian A, Omrani GR. Cotrimoxazole-induced hypoglycemia in outpatient setting. Nutrition (2014) 30(7-8):959. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2014.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Conan PL, Charton F, Quiblier A, Margery J, Rivière F. Hypoglycemic coma and co-trimoxazole in a nondiabetic patient. Med Mal Infect (2016) 46(4):236–7. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2016.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Conley TE, Mohiuddin A, Naz N. Severe co-trimoxazole-induced hypoglycaemia in a patient with microscopic polyangiitis. BMJ Case Rep (2017) 2017:bcr2016218976. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-218976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Richards KA, Raby S. Co-Trimoxazole-induced hypoglycaemia in an immunosuppressed intensive care patient. J Intensive Care Soc (2017) 18(1):59–62. doi: 10.1177/1751143716660330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rossio R, Arcudi S, Peyvandi F, Piconi S. Persistent and severe hypoglycemia associated with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in a frail diabetic man on polypharmacy: A case report and literature review. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther (2018) 56(2):86–9. doi: 10.5414/CP203084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Okazaki M, Okazaki M, Nakamura M, Asagiri T, Takeuchi S. Consecutive hypoglycemia attacks induced by co-trimoxazole followed by pentamidine in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Int J STD AIDS. (2019) 30(1):86–9. doi: 10.1177/0956462418795580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang BJ, Liu ZH, Wang QY, Liu W, Tang B, Qiu ZX, et al. Prolonged and recurrent hypoglycemia induced by trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in a Hodgkin lymphoma patient with pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. Chin Med J (Engl). (2020) 134(10):1230–2. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000001285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mah JK, Negreanu D, Radi S, Christopoulos S. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-induced refractory hypoglycaemia successfully treated with octreotide. BMJ Case Rep (2021) 14(5):e240232. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-240232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lavrador M, Catarino D, Cátia AA, Luísa B, Paiva I. Sulfamethoxazole/Trimethoprim associated hypoglycaemia in a patient with renal transplantation history. Endocrine Abstracts (2021) 73:AEP430. doi: 10.1530/endoabs.73.AEP430 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sarkar P, Puttanna A. Recurrent severe hypoglycaemia: Think about antibiotic choice. Diabetic Med (2022) 39(SUPPL 1):75. doi: 10.1111/dme.14810 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li H, Han Y. Analysis of acute hypoglycemic reaction caused by combination of damecam and compound sulfamethoxazole. Armed Police Med J (2001) 12(7):442. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1004-3594.2001.07.027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Service FJ. Hypoglycemia. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am (1997) 26:937–51. doi: 10.1016/S0889-8529(05)70288-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Morgan RK, Cortes Y, Murphy L. Pathophysiology and aetiology of hypoglycaemic crises. J Small Anim Pract (2018) 59(11):659–69. doi: 10.1111/jsap.12911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pandit MK, Burke J, Gustafson AB, Minocha A, Peiris AN. Drug-induced disorders of glucose tolerance. Ann Intern Med (1993) 118(7):529–39. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-7-199304010-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Murad MH, Coto-Yglesias F, Wang AT, Sheidaee N, Mullan RJ, Elamin MB, et al. Clinical review: Drug-induced hypoglycemia: A systematic review. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2009) 94(3):741–5. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Masters PA, O'Bryan TA, Zurlo J, Miller DQ, Joshi N. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole revisited. Arch Intern Med (2003) 163(4):402–10. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.4.402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wen X, Wang JS, Backman JT, Laitila J, Neuvonen PJ. Trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole are selective inhibitors of CYP2C8 and CYP2C9, respectively. Drug Metab Dispos (2002) 30(6):631–5. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.6.631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Williams JD. The garrod lecture. selective toxicity and concordant pharmacodynamics of antibiotics and other drugs. J Antimicrob Chemother (1995) 35(6):721–37. doi: 10.1093/jac/35.6.721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. McLaughlin SA, Crandall CS, McKinney PE. Octreotide: an antidote for sulfonylurea-induced hypoglycemia. Ann Emerg Med (2000) 36(2):133–8. doi: 10.1067/mem.2000.108183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hsu WH, Xiang HD, Rajan AS, Kunze DL, Boyd AE, 3rd. Somatostatin inhibits insulin secretion by a G-protein-mediated decrease in Ca2+ entry through voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels in the beta cell. J Biol Chem (1991) 266(2):837–43. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(17)35249-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.