Abstract

Introduction

Bovine coronavirus (BCoV) is a causative agent of enteric and respiratory diseases in cattle. Despite its importance for animal health, no data is available on its prevalence in Poland. The aim of the study was to determine the virus’ seroprevalence, identify risk factors of BCoV exposure in selected cattle farms and investigate the genetic variability of circulating strains.

Material and Methods

Serum and nasal swab samples were collected from 296 individuals from 51 cattle herds. Serum samples were tested with ELISA for the presence of BCoV-, bovine herpesvirus-1 (BoHV-1)- and bovine viral diarrhoea virus (BVDV)-specific antibodies. The presence of those viruses in nasal swabs was tested by real-time PCR assays. Phylogenetic analysis was performed using fragments of the BCoV S gene.

Results

Antibodies specific to BCoV were found in 215 (72.6%) animals. Seropositivity for BCoV was more frequent (P>0.05) in calves under 6 months of age, animals with respiratory signs coinfected with BoHV-1 and BVDV and increased with herd size. In the final model, age and herd size were established as risk factors for BCoV-seropositivity. Genetic material of BCoV was found in 31 (10.5%) animals. The probability of BCoV detection was the highest in medium-sized herds. Polish BCoVs showed high genetic homology (98.3–100%) and close relatedness to European strains.

Conclusion

Infections with BCoV were more common than infections with BoHV-1 and BVDV. Bovine coronavirus exposure and shedding show age- and herd density-dependence.

Keywords: BCoV, BoHV-1, BVDV, serology, real time RT-PCR

Introduction

Coronaviruses are RNA viruses that can infect multiple mammalian and avian species causing respiratory, enteric, hepatic and neurological diseases. As their genome is characterised by a high mutation rate, they are able to adapt quickly to novel hosts and ecological niches. This has become especially evident in recent years with the occurrence of local outbreaks of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) and the global pandemic of SARS-CoV-2 (29). Bovine coronavirus (BCoV) belongs to the Betacoronavirus genus and is closely related to one of the human coronaviruses, HCoV OC43 (8). It can cause both respiratory and enteric diseases and is involved in neonatal calf diarrhoea, winter dysentery in cattle, and bovine respiratory disease complex (BRDC). BRDC is one of the most important causes of morbidity and mortality in cattle. It is a multiagent disease associated with different viral and bacterial pathogens (22). Apart from bovine coronavirus, bovine herpesvirus 1 (BoHV-1) and bovine viral diarrhoea virus (BVDV) are among the most important viral agents involved in BRDC (20, 22). Infections with those viruses not only directly affect farming incomes by influencing productivity, e.g. weight gain, but also increase the risk of secondary bacterial infections that necessitate the increased use of antibiotics. In Poland, infections with BoHV-1 are monitored on a regular basis, 71 local outbreaks having been detected in 2017 (5). At the same time, the latest data from 2015–2016 show that more than one third of Polish cattle herds could be affected by BVDV infections (18). In contrast, the epizootic situation of BCoV infection in Polish cattle remains unknown and no local strains have been identified yet.

Additionally, while the importance of the interaction between different pathogens is widely recognised, including the significance of BCoV in the occurrence of BRDC, no studies on coinfections with multiple respiratory viruses have been performed in Poland in recent years (11, 16). The aim of the study was to investigate the prevalence of co-occurring infections with the three viruses BCoV, BVDV and BoHV-1 in selected cattle herds in Poland among both healthy animals and those showing signs of respiratory disease. As a follow-up, sequences of BCoV isolates were characterised for the first time in the country.

Material and Methods

Sample collection. Paired samples of serum and nasal swabs were collected from 296 animals of 51 cattle herds from Wielkopolskie (11 herds), Podlaskie (16 herds), Pomorskie (11 herds), Opolskie (1 herd) and Mazowieckie provinces (12 herds) between 2014 and 2015. The samples were kept in temperature-controlled conditions and transferred to the laboratory within 48 h of collection. Among the sampled animals there were 34 males and 120 females, but sex information was missing for 142 animals. Age data were available for 261 animals: 89 individuals were younger than 3 months, 126 were older than 3 months but younger than 6 months, and 51 were older than 6 months. Data on herd size was available for 245 animals: 62 were from small herds (≤77 animals), 158 from medium herds (80–590) and 25 from large herds (≥750). Additionally, the health status of 171 animals was known, 86 of which showed signs of respiratory disease. All samples were collected from animals that had no history of previous vaccinations against BoHV-1 or BVDV.

Serology. Serum samples were tested using a Monoscreen Ab Bovine coronavirus/Competition ELISA (Bio-X Diagnostics, Rochefort, Belgium), BVDV Total Ab Test (IDEXX, Liebefeld-Bern, Switzerland) and infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR) /BHV-1 gB X3 Test (IDEXX) designed to detect antibodies specific to BCoV, BVDV and BoHV-1, respectively. The assays were used in accordance with the instructions provided by the manufacturers. Doubtful results were excluded from further statistical analysis.

Real-time PCR. Viral RNA was extracted from 140 μL of nasal swab samples using a QIAamp Viral RNA Mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. Ribonucleic acid was eluted in 50 μL of elution buffer and stored at −70°C. Viral DNA was extracted from 200 μL of nasal swab samples using a QIAamp DNA Mini kit (Qiagen), eluted in 30 μL of elution buffer and stored at −70°C.

A real-time reverse transcriptase RT-PCR for BCoV detection was run using previously described primers specific to the gene encoding the M protein (6). Additionally, for internal control, a 200 μL mix of primers and probes specific to β-actin was prepared consisting of 5 μL of 100 μM ACT-1005-F and ACT-1135-R primers, 3.75 of 100 μM ACT-1081-HEX probe and 186.25 μL of water (24). The reaction was run in 20 μL of reaction mix that comprised 6.3 μL of water, 4 μL of 5× QuantiTect Virus Master Mix (Qiagen), 2 μL of each BCoV-specific forward and reverse primer (10 μM), 2 μL of BCoV-specific probe (5 μM), 1.5 μL of a mixture of primers and probes specific to bACT, 0.2 μL of 100 QuantiTect Virus RT Mix (Qiagen) and 2 μL of RNA sample. After 30 min of reverse transcription at 42°C and a 10 min incubation at 95°C, 40 cycles of amplification were run each consisting of 15 s of denaturation at 95°C and 45 s of annealing/elongation at 58°C.

A real-time PCR specific to BoHV-1 was run using previously described primers specific to the gene encoding glycoprotein gD (26). The reaction was run in 25 μL of a mix that included 14.5 μL of water, 5 μL of 5× QuantiTect Virus Master Mix (Qiagen), 1 μL of each BoHV-1 specific forward and reverse primer (10 μM), 1 μL of BoHV specific probe (10 μM) and 2.5 μL of DNA sample. The reaction started with a 5 min incubation at 50°C, and proceeded through 2 min at 95°C and 45 cycles of amplification consisting of 15 s of denaturation at 95°C and 45 s of annealing/elongation at 60°C.

A multiplex real-time PCR for BVDV-1 and 2 detection was performed using the primers specific to the 5ʹ untranslated region described by Baxi et al. (1). The reaction was carried out in a 25 μL mix that included 7 μL of water, 12.5 μL of AgPath-ID 2× RT-PCR reaction buffer (Applied Biosystems, Austin, USA), 1 μL of 10 μM of each BVDV primer, 0.25 μL of both BVDV1 and BVDV2 probes, 1 μL of AgPath-ID 25× RT-PCR enzyme mix (Applied Biosystems) and 2 μL of RNA sample. The reaction started with 10 min of reverse transcription at 48°C and continued with a 10 min incubation at 95°C. Next, 40 cycles of amplification were performed consisting of 15 s of denaturation at 95°C and 45 s of annealing/elongation at 60°C.

All real-time PCR amplifications were performed using the LightCycler 96 Instrument (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Sequences of primers used for detection of the viruses are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers and probes used for BCoV, BVDV, BoHV-1 and internal control amplification

| Target | Primer/probe | Sequence (5′–3′) | Amplicon size (bp) | Gene/ protein | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCoV-F | CTGGAAGTTGGTGGAGTT | ||||

| BCoV-R | ATTATCGGCCTAACATACATC | 85 | M/matrix | ||

| BCoV | BCoV-Pb | FAM-CCTTCATATCTATACACATCAAGTTGTT-BHQ1 | (6) | ||

| Sp1 | CTTATAAGTGCCCCCAAACTAAAT | ||||

| Sp2 | CCTACTGTGAGATCACATGTTTG | 622 | S/spike | ||

|

| |||||

| Pesti-F | CTAGCCATGCCCTTAGTAG | ||||

| Pesti-R | CGTCGAACCAGTGACGACT | ||||

| BVDV | BVDV1 | FAM-TAGCAACAGTGGTGAGTTCGTTGGATGGCT-BHQ1 | 106 | 5′-UTR | (1) |

| BVDV2 | TxR-TAGCGGTAGCAGTGAGTTCGTTGGATGGCC-BHQ1 | ||||

|

| |||||

| gD5595-F | CCGCCGTATTTTGAGGAGTCG | ||||

| BoHV-1 | gD5704-R | TCGGTCTCCCCTTCRTCCTC | 46 | gD | (26) |

| BHV1-gD-FAM* | FAM-TCGGTCTCCCCTTCRTCCTC-BHQ1 | ||||

|

| |||||

| ACT-1005-F | CAGCACAATGAAGATCAAGATCATC | ||||

| β Actin | ACT-1135-R | CGGACTCATCGTACTCCTGCTT | 130 | bACT | (24) |

| ACT-1081-HEX | HEX-TCGCTGTCCACCTTCCAGCAGATGT- BHQ1 | ||||

BCoV – bovine coronavirus; F – forward; R – reverse; BVDV – bovine viral diarrhoea virus; Pesti – pestivirus; UTR – untranslated region; BoHV–1 – bovine herpesvirus 1; FAM – fluorescein amidite; * – modified; gD – glycoprotein D; bACT – β-actin; HEX – hexachlorofluorescein

RT-PCR and Sanger sequencing. The samples which were positive for RNA in the real-time RT-PCR were amplified with a conventional RT-PCR using Sp1 and Sp2 primers specific to the conserved fragment of the S gene encoding the spike protein (6). A Transcriptor One-Step RT-PCR kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) was used. The reaction was carried out in a total volume of 25 μL which included 1 μL of each primer at 10 μM concentration, 5 μL of 5× reaction buffer, 0.5 μL of enzyme mix, 15.5 μL of PCR grade water and 2 μL of RNA sample. The amplification steps consisted of 30 min of reverse transcription at 50°C followed by 2 min of incubation at 94°C and 45 cycles consisting of 30 s of denaturation at 94°C, 30 s of annealing at 55°C and 30 s of elongation at 68°C. The reaction was completed by a 10 min incubation at 68°C. Specific 622-nucleotide-long products were visualised in 1.5% agarose gel. Positive samples were purified and used for Sanger sequencing with the Sp1 and Sp2 primers described previously (Table 1). The reaction was performed by Genomed (Warsaw, Poland). The resulting partial sequences of the S gene were aligned with other selected coronavirus sequences available in GenBank using MEGA-X software, and a neighbour-joining phylogenetic tree was constructed (19).

Statistical analysis. The chi-squared test was used to estimate associations between the proportion of positive samples and exposure variables such as age, sex, origin and health status. Since age and herd size were not normally distributed discrete values, they were categorised into three groups by the 25th and 75th centiles (Table 2). The confidence intervals were calculated using the exact binomial distribution and Microsoft Excel. Cross-correlations for all variables were assessed by Spearman’s rank test. The generalised linear mixed models (GLMMs) using binomial error structure and logit link function were developed by backward elimination one by one of insignificant variables (with P>0.05). The multicollinearity evaluated using the variance inflation factor (≥10) and Spearman’s rank test (ρ > |0.8|; P<0.05) between the variables was considered when building up the multivariate model. Possible confounding and clustering were analysed as previously described (7). To account for clustering, models including random intercept were assessed by checking the variance of the component and other covariates. The model with the lowest Akaike information criterion and highest Bayesian information criterion values was considered the better fitting one. Detailed analyses were carried out using STATA v.13.0 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). A P-value ≤0.05 was considered significant in all the performed analyses.

Table 2.

Univariable analysis of bovine coronavirus (BCoV) seroprevalence in cows and presence of genetic material in nasal swabs (shedding) detected by reverse transcriptase RT-PCR

| Variable | Seroprevalence | RT-PCR positive | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| n/N | % | 95% CI | χ 2 | P | n/N | % | 95% CI | χ2 | P | |

| Age group* | 23.20 | <0.001 | 5.06 | 0.080 | ||||||

| ≤ 3 months | 16/89 | 82.0 | 73.9–90.1 | 14/89 | 15.7 | 8.0–23.4 | ||||

| 3–6 months | 102/126 | 81.0 | 74.0–87.9 | 12/126 | 9.5 | 4.3–14.7 | ||||

| ≥ 6 months | 25/51 | 49.0 | 34.8–63.2 | 2/51 | 3.9 | −1.6–9.4 | ||||

| All | 201/261 | 77.0 | 71.4–82.0 | 29/261 | 11.1 | 7.6–15.6 | ||||

| Sex | 0.006 | 0.940 | 2.90 | 0.088 | ||||||

| Female | 89/120 | 74.2 | 65.6–87.1 | 7/120 | 5.8 | 2.4–11.6 | ||||

| Male | 25/34 | 73.5 | 55.6–87.1 | 5/34 | 14.7 | 5.0–31.1 | ||||

| All | 114/154 | 74.0 | 66.4–80.8 | 12/154 | 7.8 | 4.1–13.2 | ||||

| Respiratory signs | 4.39 | 0.0361 | 3.23 | 0.072 | ||||||

| Yes | 62/86 | 72.1 | 61.4–81.2 | 15/86 | 17.4 | 10.1–27.1 | ||||

| No | 57/85 | 67.1 | 56.0–76.9 | 7/85 | 8.2 | 3.4–16.2 | ||||

| All | 119/171 | 69.6 | 62.1–76.4 | 22/171 | 12.9 | 8.2–18.8 | ||||

| BoHV–1 status | 13.97 | <0.001 | 0.084 | 9.772 | ||||||

| Seropositive | 99/117 | 84.6 | 76.8–90.6 | 13/117 | 11.1 | 6.1–18.3 | ||||

| Seronegative | 116/179 | 64.8 | 57.3–71.8 | 18/179 | 10.1 | 6.1–15.4 | ||||

| All | 215/296 | 72.6 | 67.2–77.6 | 31/296 | 10.5 | 7.2–14.5 | ||||

| BVDV status | 5.98 | 0.014 | 1.249 | 0.264 | ||||||

| Seropositive | 113/144 | 78.5 | 70.9–84.9 | 18/144 | 12.5 | 7.6–19.0 | ||||

| Seronegative | 93/142 | 65.5 | 57.1–73.3 | 12/142 | 8.4 | 4.4–14.3 | ||||

| All | 206/286 | 72.0 | 66.4–77.2 | 30/286 | 10.5 | 7.2–14.6 | ||||

| BoHV–1 PCR | 1.142 | 0.285 | 0.35 | 0.554 | ||||||

| Positive | 3/3 | 100.0 | 29.2–100.0 | 0/3 | 0.0 | 0.0–70.8 | ||||

| Negative | 212/293 | 72.3 | 66.9–77.4 | 31/293 | 10.6 | 7.3–14.7 | ||||

| All | 215/296 | 72.6 | 76.2–77.6 | 31/296 | 10.5 | 7.2–14.5 | ||||

| BVDV RT–PCR | 5.107 | 0.024 | 0.04 | 0.841 | ||||||

| Positive | 3/8 | 37.5 | 8.5–75.5 | 1/8 | 12.5 | 0.3–52.7 | ||||

| Negative | 212/288 | 73.6 | 68.1–78.6 | 30/288 | 10.4 | 7.1–14.5 | ||||

| All | 215/296 | 72.6 | 67.2–77.6 | 31/296 | 10.5 | 7.2–14/5 | ||||

| BCoV RT–PCR | 0.042 | 0.837 | ||||||||

| Positive | 23/31 | 74.2 | 55.4–88.1 | |||||||

| Negative | 192/265 | 72.4 | 66.7–77.7 | |||||||

| All | 215/296 | 72.6 | 67.2–77.6 | |||||||

| Herd size* | 29.34 | <0.001 | 10.35 | 0.006 | ||||||

| Smaller (≤77) | 31/62 | 50.0 | 6.0–62.8 | 1/62 | 1.6 | −1.6–4.8 | ||||

| Medium (80–590) | 128/158 | 81.0 | 74.8–87.2 | 19/158 | 12.0 | 6.9–17.1 | ||||

| Larger (≥750) | 24/25 | 96.0 | 87.7–104.2 | 6/25 | 24.0 | 6.0–42.0 | ||||

| All | 183/245 | 74.7 | 69.1–80.3 | 25/245 | 10.2 | 6.7–14.8 | ||||

| Province | 12.65 | 0.013 | 13.04 | 0.011 | ||||||

| Mazowieckie | 44/66 | 66.7 | 54.0–77.8 | 9/66 | 13.6 | 6.4–24.3 | ||||

| Pomorskie | 42/60 | 70.0 | 56.8–81.1 | 2/60 | 3.3 | 0.4–11.5 | ||||

| Opolskie | 58/70 | 82.8 | 71.9–90.8 | 5/70 | 7.1 | 2.4–15.9 | ||||

| Podlaskie | 38/45 | 84.4 | 70.5–93.5 | 3/45 | 6.7 | 1.4–18.3 | ||||

| Wielkopolskie | 33/55 | 60.0 | 46.0–73.0 | 12/55 | 21.8 | 11.8–35.0 | ||||

| All | 215/296 | 72.6 | 67.2–77.6 | 31/296 | 10.5 | 7.2–14.5 | ||||

n – number of positive animals; N – all animals tested in the category; CI – confidence interval; * – age group and herd size variables were categorised into three groups by values of ≤25th, 25th–75th and ≥75th centile prior to analysis. P-values ≤0.05 were considered significant

Results

Serology. Antibodies specific to BCoV were found in 215 (72.6%), to BVDV in 144 (50.3%) and to BoHV-1 in 117 (39.5%) of the tested animals. Ten serum samples were doubtful for BVDV and were excluded from further analysis. Among the 51 cattle herds tested, BCoV seropositive animals were found in 42, whereas animals seropositive for BoHV-1 and BVDV were detected in only 19 and 30 herds, respectively. Animals seropositive to more than one viral agent were identified, including 113 (39.4%) BCoV/BVDV-positive, 99 (33.5%) BCoV/BoHV-1-positive and 87 (30.3%) BVDV/BoHV-1 -positive cattle. Additionally, 72 (25.1%) animals had antibodies to all three tested viral agents (BCoV/BVDV/ BoHV-1). Moreover, BCoV seropositivity was associated with seropositivity to the other two respiratory viruses (Table 2). Bovine coronavirus-seropositive animals were more frequent in the younger age groups (calves at the age of ≤3 months and 3–6 months) and in the subset of cows which showed respiratory clinical signs (Table 2). Seroprevalence of BCoV was also higher in the herds of more than 80 head and varied significantly between provinces. The risk factors in the final GLMMs for the presence of BCoV antibodies included the age group and herd size, with the province as a fixed effect (Table 3). The probability of detecting BCoV decreased in cattle over 6 months of age (odds ratio – OR: 0.27); however, the highest ORs were estimated for medium- and larger-sized herds. Cattle originating from these two herd categories had a greater risk of being BCoV seropositive with ORs of 5.2 and 39.9, respectively.

Table 3.

The final generalised linear mixed model presenting risk factors of bovine coronavirus seropositivity in cattle (number of observations = 229)

| Variable | Category | Odds ratio | β (SE) | z | P > |z| | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group* | ||||||

| ≤3 months | reference | |||||

| 3–6 months | 0.58 | 0.32 | −0.99 | 0.323 | 0.19–1.72 | |

| ≥6 months | 0.27 | 0.14 | −2.44 | 0.015 | 0.10–0.78 | |

| Herd size* | ||||||

| Smaller (≤77) | reference | |||||

| Medium (80–590) | 5.20 | 2.93 | 2.91 | 0.004 | 1.71–15.72 | |

| Larger (≥750) | 39.90 | 45.78 | 3.21 | 0.001 | 4.21–378.14 | |

|

| ||||||

| Fixed effect | Variance | β (SE) | 95% CI | |||

| Province | 0.95 | 0.87 | 0.16–5.76 | |||

SE – standard error; z – Wald z statistic; CI – confidence interval; * – age group and herd size variables were categorised into three groups by values of ≤25th, 25th – 75th and ≥75th centile prior to analysis

Virus detection in nasal swab samples. Each of the tested nasal swabs was positive for the presence of β-actin, confirming the appropriate quality of the collected material. Genetic material of BCoV was found in 31 (10.5%), material of BVDV-1 in 8 (2.7%) and that of BoHV-1 in 3 (1%) of the tested animals. No samples positive for BVDV-2 were identified. The presence of BCoV genetic material was detected more frequently in younger calves, males and animals with clinical signs of respiratory disease; however, the associations were only borderline significant (Table 2). The virus was detected significantly more often in nasal swabs from animals originating from larger herds, and again the prevalence differed by province. The final multivariable model included herd size as a single risk factor for BCoV RNA detection in nasal swab samples from individual cattle (Table 4) adjusted for age group as a fixed effect. The probability of detecting BCoV-infected animals was the highest (OR of 4.22) in the medium-sized (80–590 head) herds.

Table 4.

The final generalised linear mixed model presenting risk factors of bovine coronavirus detection in nasal swabs from individual cattle by reverse transcriptase PCR (number of observations = 229)

| Variable | Category | Odds ratio (OR) | β (SE) | z | P > |z| | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Herd size* | ||||||

| Smaller (≤77) | reference | |||||

| Medium (80–590) | 4.22 | 1.92 | 3.16 | 0.004 | 1.73–10.30 | |

| Larger (≥750) | 0.02 | 0.02 | -4.24 | <0.001 | 0.002–0.11 | |

|

| ||||||

| Fixed effect | Variance | β (SE)c | 95% CI | |||

| Age group | 1.06 | 1.66 | 0.05–23.16 | |||

SE – standard error; z – Wald z statistic; CI – confidence interval; * – age group and herd size variables were categorised into three groups by values of ≤25th, 25th–75th and ≥75th centile prior to analysis

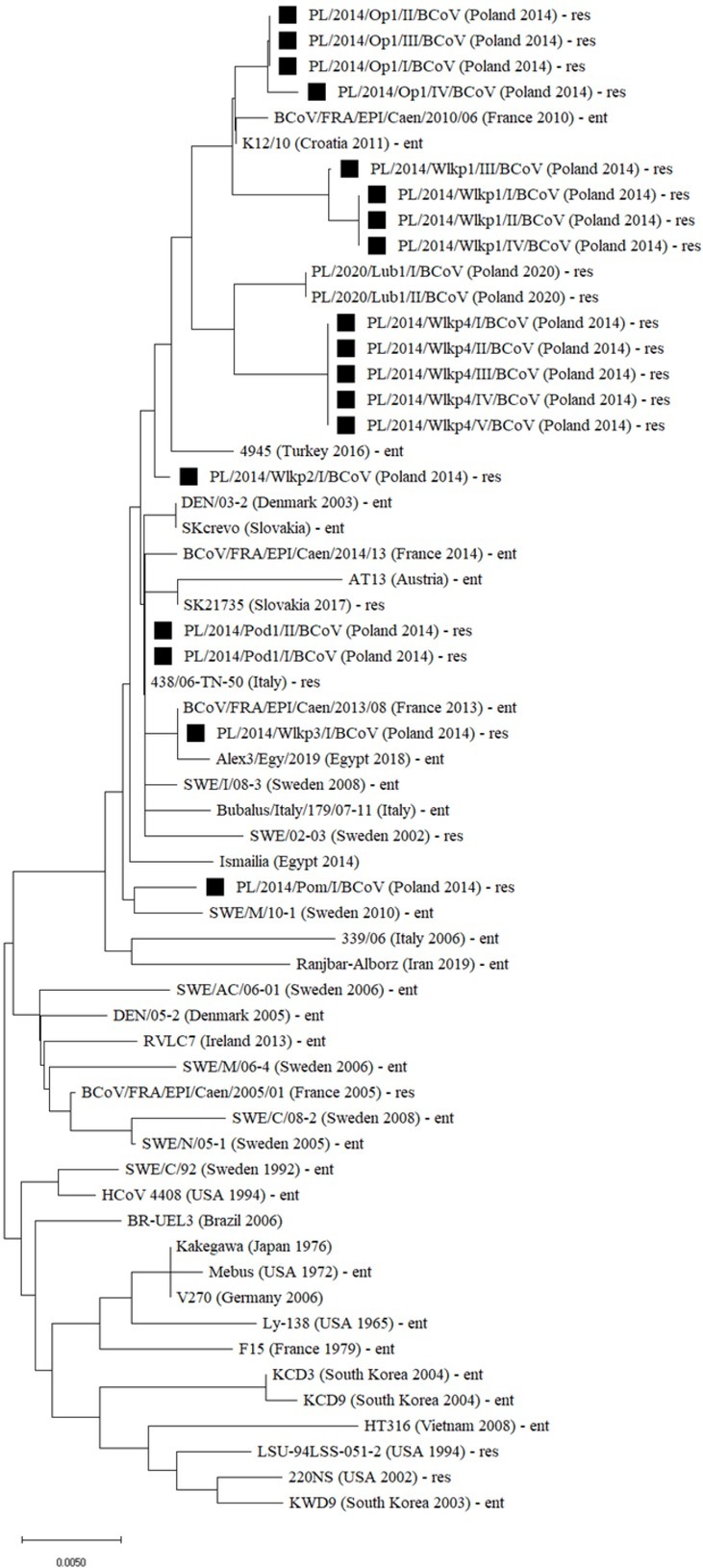

Phylogenetic analysis of BCoV sequences. In total, 18 partial sequences of the spike protein gene were successfully sequenced and submitted to GenBank under accession numbers OL477639–OL477656. Sequences were aligned using MEGA-X and a phylogenetic tree was constructed by neighbour-joining. All identified BCoV strains showed high genetic homology in the analysed gene fragment (98.3–100%) and clustered together with recent European strains of BCoV, including Polish strains isolated in 2020 (unpublished data) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Neighbour-joining phylogenetic tree of sequences obtained in the study (19). The tree was constructed using a 601-nucleotide-long fragment of the gene encoding the spike protein of BCoV. Sequences acquired in this study are marked by black squares. The country and the date of isolation (when available) are included in the brackets next to each sequence res – respiratory isolate; ent – enteric isolate

Discussion

Bovine coronavirus seemed to be the most common viral pathogen in the tested population, as almost three quarters of the tested animals were seropositive, and the virus was detected in 10.5% of nasal swabs. Similarly, high BCoV seroprevalence was observed in recent studies conducted in Norway and Sweden, where 72.2% and up to 85.3% of dairy herds were seropositive, respectively (23, 27). At the same time, a significant correlation was observed between respiratory signs and the presence of BCoV-specific antibodies. Respiratory signs were also more common in animals for which the presence of BCoV was confirmed in nasal swabs; however, this correlation was marginal and not statistically significant. Those ambiguous results are not uncommon for BCoV, and for this reason the role of this virus as the primary agent of BRDC remains controversial. Previous studies showed serological prevalence of over 90%, suggesting that most cattle become exposed to BCoV during their lifetime; however, the virus was identified in both healthy and diseased animals (4, 29). It is possible that, as was previously described, BCoV does not initiate the respiratory disease, but may trigger the process in case of coinfection with other respiratory pathogens (16). In our study, seropositivity to BCoV was more frequent among younger animals (calves at the age of ≤3 months and 3–6 months) and moreover, age was identified as one of the risk factors. The higher seropositivity among young animals contradicted previous results showing an increase in the BCoV seroprevalence with age of the animal (2). This discrepancy may arise from the retention of maternal antibodies by a significant part of the youngest age group in our study. Tuncer et al. (25) described the decline of BCoV passive immunity as starting at three months. On the other hand, it was observed that BCoV was also detected more frequently in younger animals. Similar results were found in a previous study, which suggested that it is associated with an insufficient efficiency of the immune response in eliminating the virus in young, naïve calves (21).

Previous studies showed that a large herd size could be associated with a higher risk of BCoV seropositivity (12, 23). This was also observed in our study, as significant differences were found between herds of different sizes, with an increase in seroprevalence with the size of the herd. The herd size was also one of the risk factors for seroprevalence, and cases of active BCoV infections were detected more frequently in larger herds. It is possible that a larger number of animals favours the persistence of this virus in the herd, as it is more likely that susceptible individuals are present, creating better conditions for virus circulation. Additionally, it was suggested that larger herds could have more indirect contact with carriers and be at greater iatrogenic risk via veterinarians and technical personnel if biosecurity standards are insufficient (23). This could be a potential route for the spread of BCoV within and between herds, as it was previously shown that transmission of the virus via fomites is possible (13).

Given the seroprevalence data, cattle are exposed more frequently to BCoV in the herds where BVDV and BoHV-1 are also present. These two viruses are endemic and covered by eradication programmes introduced in Poland. Different large-scale studies on BVDV herd-level seroprevalence estimated using bulk milk samples showed that 33% or 71% of herds were infected with the virus (10, 18). The present study has shown a comparable animal-level seroprevalence of over 50% and over 70% herd-level seroprevalence. It must be stated, however, that the validity of the correlation is circumscribed by the limited number of animals and herds included. The problems with BVDV control arise also from vaccination failure and widening of the genetic variability of field BVDV strains, especially since BVDV-2 infection has been confirmed in Poland (15).

The seroprevalence and the number of virus-infected animals was the lowest in the case of BoHV-1 at 39.5% and 1%, respectively. These are similar results to those of a previous study in which serum samples collected from Polish dairy farms in 2011 showed the true prevalence of BoHV-1 infection to be 49.3% (17).

Both BVDV and BoHV-1 are considered primary pathogens, as they can lead to serious, potentially lethal diseases in cattle even as single agents, while in the case of BCoV, primary pathogen status remains controversial (14). Nevertheless, coinfection with multiple viral agents has been described by Ridpath et al. (16) as common in cattle and leading to potential synergy resulting in increased pathogenesis. In our study, almost 40% of the animals were seropositive to more than one viral pathogen. Zhu et al. (30) confirmed that BCoV was the most frequent viral partner in coinfections detected in respiratory disease patients, as was also observed in our study. Both BVDV and BoHV-1 infection cause immunosuppression. This promotes secondary infections and, as a result, complicates the course of BRDC (3, 16). This predisposition to secondary infections may explain the association of BCoV exposure with the two other respiratory viruses in the presented study. However, it should be noted that the majority of the tested animals were under 6 months old, and as such, they could still have possessed maternal antibodies to each of the analysed viruses.

This is also the first report to describe BCoV detection in Poland. Sequences of BCoV showed clustering predominantly with viral strains originating from European countries and isolated in the last two decades, including the most recent Polish BCoV strains from 2020. All isolates originated from the respiratory tract but their sequences were closely related to both enteric and respiratory strains, with no clear clustering involving infection type. This was in line with previous observations that viral tissue tropism seemed to be unrelated to the genetic sequence of a particular strain (9, 28).

In conclusion, our study showed that infections with BCoV were common in the regions of Poland analysed in this study and were more seroprevalent than infections with BVDV and BoHV-1. Furthermore, statistical analysis showed that they may be associated with cases of respiratory disease in Polish cattle and may vary in frequency of occurrence by herd size and cattle age group. The sequences of Polish BCoVs mainly clustered by geographical location of isolation rather than isolation date or pathology.

Acknowledgements

We thank Małgorzata Głowacka and Agnieszka Nowakowska for their excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Conflict of Interests Statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this article.

Financial Disclosure Statement

This study was conducted as part of the statutory activity of the National Veterinary Research Institute in Puławy, Poland.

Animal Rights Statement

None required.

References

- 1.Baxi M., McRae D., Baxi S., Greiser-Wilke I., Vilcek S., Amoako K., Deregt D.. A one-step multiplex real-time RT-PCR for detection and typing of bovine viral diarrhea viruses. Vet Microbiol. 2006;116:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2006.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bidokhti M.R., Tråvén M., Fall N., Emanuelson U., Alenius S.. Reduced likelihood of bovine coronavirus and bovine respiratory syncytial virus infection on organic compared to conventional dairy farms. Vet J. 2009;182:436–440. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biswas S., Bandyopadhyay S., Dimri U., Patra P.. Bovine herpesvirus-1 (BHV-1) – a re-emerging concern in livestock: a revisit to its biology, epidemiology, diagnosis, and prophylaxis. Vet Q. 2013;33:68–81. doi: 10.1080/01652176.2013.799301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boileau M.J., Kapil S.. Bovine coronavirus associated syndromes. Vet Clin N Am - Food Anim Pract. 2010;26:123–146. doi: 10.1016/j.cvfa.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zintegrowany wieloletni plan kontroli dla Polski - Raport Roczny 2017 (Integrated multi-annual control plan for Poland - Annual Report 2017 – in Polish), GIS. Warsaw: 2018. https://www.gov.pl/attachment/0e1d3b5f-9c94-4269-bc71-6196b077d618. Chief Sanitary Inspectorate of the State Sanitary Inspection (SSI) of Poland. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Decaro N., Elia G., Campolo M., Desario C., Mari V., Radogna A., Colaianni M.L., Cirone F., Tempesta M., Buonavoglia C.. Detection of bovine coronavirus using a TaqMan-based real-time RT-PCR assay. J Virol Methods. 2008;151:167–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dohoo I.R., Martin W., Stryhn H.E. Veterinary Epidemiologic Research. Second Edition. VER Inc; Charlottetown, PEI,: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Domańska-Blicharz K., Woźniakowski G., Konopka B., Niemczuk K., Welz M., Rola J., Socha W., Orłowska A., Antas M., Śmietanka K., Cuvelier-Mizak B.. Animal coronaviruses in the light of COVID-19. J Vet Res. 2020;64:333–345. doi: 10.2478/jvetres-2020-0050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franzo G., Drigo M., Legnardi M., Grassi L., Pasotto D., Menandro M.L., Cecchinato M., Tucciarone C.M.. Bovine coronavirus: variability, evolution, and dispersal patterns of a no longer neglected betacoronavirus. Viruses. 2020;12:1285. doi: 10.3390/v12111285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuta A., Polak M.P., Larska M., Żmudziński J.F.. Monitoring of bovine viral diarrhoea virus (BVDV) infection in Polish dairy herds using bulk tank milk samples. Bull Vet Inst Pulawy. 2013;57:149–156. doi: 10.2478/bvip-2013-0028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nikbakht G., Tabatabaei S., Lotfollahzadeh S., Nayeri Fasaei B., Bahonar A., Khormali M.. Seroprevalence of bovine viral diarrhoea virus, bovine herpesvirus 1 and bovine leukaemia virus in Iranian cattle and associations among studied agents. J Appl Anim Res. 2015;43:22–25. doi: 10.1080/09712119.2014.883995. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohlson A., Heuer C., Lockhart C., Tråvén M., Emanuelson U., Alenius S.. Risk factors for seropositivity to bovine coronavirus and bovine respiratory syncytial virus in dairy herds. Vet Rec. 2010;167:201–207. doi: 10.1136/vr.c4119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oma V.S., Klem T., Tråvén M., Alenius S., Gjerset B., Myrmel M., Stokstad M.. Temporary carriage of bovine coronavirus and bovine respiratory syncytial virus by fomites and human nasal mucosa after exposure to infected calves. BMC Vet Res. 2018;14:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12917-018-1335-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pardon B., Buczinski S.. Bovine respiratory disease diagnosis: what progress has been made in infectious diagnosis? Vet Clin N Am - Food Anim Pract. 2020;36:425–444. doi: 10.1016/j.cvfa.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Polak M.P., Kuta A., Rybałtowski W., Rola J., Larska M., Żmudziński J.F.. First report of bovine viral diarrhoea virus-2 infection in cattle in Poland. Vet J. 2014;202:643–645. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ridpath J.F., Fulton R.W., Bauermann F.V., Falkenberg S.M., Welch J., Confer A.W.. Sequential exposure to bovine viral diarrhea virus and bovine coronavirus results in increased respiratory disease lesions: clinical, immunologic, pathologic, and immunohistochemical findings. J Vet Diagn. 2020;32:513–526. doi: 10.1177/1040638720918561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rola J.G., Larska M., Grzeszuk M., Rola J.. Association between antibody status to bovine herpesvirus 1 and quality of milk in dairy herds in Poland. J Dairy Sci. 2015;98:781–789. doi: 10.3168/jds.2014-8781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rypuła K., Płoneczka-Janeczko K., Czopowicz M., Klimowicz-Bodys M.D., Shabunin S., Siegwalt G.. Occurrence of BVDV infection and the presence of potential risk factors in dairy cattle herds in Poland. Animals. 2020;10:230. doi: 10.3390/ani10020230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saitou N., Nei M.. The neighbor-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salem E., Dhanasekaran V., Cassard H., Hause B., Maman S., Meyer G., Ducatez M.F.. Global transmission, spatial segregation, and recombination determine the long-term evolution and epidemiology of bovine coronaviruses. Viruses. 2020;12:534. doi: 10.3390/v12050534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Studer E., Schönecker L., Meylan M., Stucki D., Dijkman R., Holwerda M., Glaus A., Becker J.. Prevalence of BRD-related viral pathogens in the upper respiratory tract of Swiss veal calves. Animals. 2021;11:1940. doi: 10.3390/ani11071940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor J.D., Fulton R.W., Lehenbauer T.W., Step D.L., Confer A.W.. The epidemiology of bovine respiratory disease: What is the evidence for predisposing factors? Can Vet J. 2010;51:1095–1102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toftaker I., Sanchez J., Stokstad M., Nødtvedt A.. Bovine respiratory syncytial virus and bovine coronavirus antibodies in bulk tank milk – risk factors and spatial analysis. Prev Vet Med. 2016;133:73–83. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2016.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Toussaint J.F., Sailleau C., Breard E., Zientara S., De Clercq K.. Bluetongue virus detection by two real-time RT-qPCRs targeting two different genomic segments. J Virol Methods. 2007;140:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tuncer P., Yeşilbağ K.. Serological detection of infection dynamics for respiratory viruses among dairy calves. Vet Microbiol. 2015;180:180–185. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2015.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wernike K., Hoffmann B., Kalthoff D., König P., Beer M.. Development and validation of a triplex real-time PCR assay for the rapid detection and differentiation of wild-type and glycoprotein E-deleted vaccine strains of Bovine herpesvirus type 1. J Virol Methods. 2011;174:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2011.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolff C., Emanuelson U., Ohlson A., Alenius S., Fall N.. Bovine respiratory syncytial virus and bovine coronavirus in Swedish organic and conventional dairy herds. Acta Vet Scand. 2015;57:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s13028-014-0091-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vilček S., Jacková A., Kolesárová M., Vlasáková M.. Genetic variability of the S1 subunit of enteric and respiratory bovine coronavirus isolates. Acta Virol. 2017;61:212–216. doi: 10.4149/av_2017_02_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vlasova A.N., Saif L.J.. Bovine coronavirus and the associated diseases. Front Vet Sci. 2021;8:293. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.643220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu Q., Li B., Sun D.. Advances in Bovine Coronavirus Epidemiology. Viruses. 2022;14:1109. doi: 10.3390/v14051109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]