Significance

Cerebral small vessel diseases (cSVDs) are a group of related idiopathic and familial pathologies that cause stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), and cognitive decline. The underlying mechanisms are poorly understood, and no effective treatment options exist. Here, we investigated a mouse that models a form of cSVD caused by a mutation in the gene encoding type collagen IV alpha1 (COL4A1) to better understand the pathogenesis of the disease. We found that impairment of transient receptor potential melastatin 4 (TRPM4) cation channels disrupted the ability of cerebral arteries from middle-aged mutant animals to constrict in response to physiological levels of intraluminal pressure. Vascular function was restored by acute inhibition of phosphoinositide 3-kinase and transforming growth factor-βreceptors, potentially identifying new therapeutic targets.

Keywords: cerebral small vessel diseases, PIP2, vascular smooth muscle, COL4A1, ion channels

Abstract

Gould syndrome is a rare multisystem disorder resulting from autosomal dominant mutations in the collagen-encoding genes COL4A1 and COL4A2. Human patients and Col4a1 mutant mice display brain pathology that typifies cerebral small vessel diseases (cSVDs), including white matter hyperintensities, dilated perivascular spaces, lacunar infarcts, microbleeds, and spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. The underlying pathogenic mechanisms are unknown. Using the Col4a1+/G394V mouse model, we found that vasoconstriction in response to internal pressure—the vascular myogenic response—is blunted in cerebral arteries from middle-aged (12 mo old) but not young adult (3 mo old) animals, revealing age-dependent cerebral vascular dysfunction. The defect in the myogenic response was associated with a significant decrease in depolarizing cation currents conducted by TRPM4 (transient receptor potential melastatin 4) channels in native cerebral artery smooth muscle cells (SMCs) isolated from mutant mice. The minor membrane phospholipid phosphatidylinositol 4,5 bisphosphate (PIP2) is necessary for TRPM4 activity. Dialyzing SMCs with PIP2 and selective blockade of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), an enzyme that converts PIP2 to phosphatidylinositol (3, 4, 5)-trisphosphate (PIP3), restored TRPM4 currents. Acute inhibition of PI3K activity and blockade of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) receptors also rescued the myogenic response, suggesting that hyperactivity of TGF-β signaling pathways stimulates PI3K to deplete PIP2 and impair TRPM4 channels. We conclude that age-related cerebral vascular dysfunction in Col4a1+/G394V mice is caused by the loss of depolarizing TRPM4 currents due to PIP2 depletion, revealing an age-dependent mechanism of cSVD.

Cerebral small vessel diseases (cSVDs) are a group of familial and sporadic pathologies afflicting the blood vessels in the brain. cSVDs are a major cause of vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia (VCID), second only to Alzheimer’s disease as the most common form of dementia in adults (1). VCID and cSVDs are more prevalent in the elderly and are expected to overburden health care systems globally as the world’s population ages (2). Idiopathic and familial forms of the disease have been described, but the pathogenesis remains poorly understood and specific treatment options are not available. Mutations in the genes encoding type IV collagen alpha 1 (COL4A1) and alpha 2 (COL4A2) cause Gould syndrome, an autosomal dominant multisystem disorder that encompasses all the hallmarks of cSVDs, including white matter hyperintensities, intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), lacunes, and microinfarcts (3, 4). How COL4A1 and COL4A2 mutations cause cSVD and related brain defects are not known. Studies using a murine allelic series of Col4a1 and Col4a2 mutations show allelic heterogeneity with a position effect whereby mutations closer to the carboxyl terminus of the triple helical domain are associated with increased ICH severity (5, 6). These findings suggest that the mechanisms underlying cSVD associated with Gould syndrome are heterogeneous and complex. Here, we sought to elucidate the molecular links between a specific Col4a1 mutation and cerebrovascular dysfunction.

COL4A1 and COL4A2 form a heterotrimer [α1α1α2(IV)] that is a fundamental component of all basement membranes. Collagen α1α1α2(IV) is secreted to the extracellular space, where it polymerizes into networks that are further cross-linked with other basement membrane components. COL4A1 and COL4A2 proteins are composed of a long triple helical domain flanked by 7S and NC1 domains at the amino and carboxyl termini, respectively (7). The triple helical regions consist of long stretches of G-X-Y repeats characteristic of all collagens. Glycine (G) is required at every third amino acid as the absence of a side chain allows it to fit into the core of the triple helix (8). The vast majority of pathogenic COL4A1 and COL4A2 mutations are missense mutations of one of these highly conserved glycine residues (9–11). Such mutations are thought to drive three potential adverse outcomes: diminishment of normal collagen α1α1α2(IV) in basement membranes; secretion and incorporation of mutant collagen α1α1α2(IV) that disrupts the functional integrity of the basement membrane; and intracellular retention of misfolded collagen α1α1α2(IV) molecules that cause ER/SR stress in collagen-producing cells (12). Col4a1 mutant mice display striking position-dependent heterogeneity in trafficking defects, with diminishing export and increased intracellular retention of collagen α1α1α2(IV) associated with mutations closer to the carboxyl terminus of the protein (13). For the current study, we used mice heterozygous for a point mutation in Col4a1 in which the G residue at position 394 (relatively near the amino terminus) had been replaced by valine (V). Col4a1+/G394V mice traffic collagen α1α1α2(IV) out of cells relatively efficiently (13), suggesting that the pathology of these animals is independent of ER/SR stress and that structural and/or functional imperfections in the basement membrane is the primary defect.

Autoregulation of blood flow in the brain is maintained in part by the vascular myogenic response, a process that sustains partial constriction of arteries and arterioles in response to intraluminal pressure (14). The myogenic response maintains near-constant blood flow within the microcirculation during beat-to-beat fluctuations in the force of perfusion, thereby preventing tissue ischemia during transient drops in pressure and protecting delicate capillary beds during temporary increases in pressure (14). Several types of cerebrovascular disease disrupt this process, including familial cSVD associated with cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) (15). The effects of Col4a1 mutations on the myogenic tone of cerebral arteries are not known. Signaling pathways intrinsic to vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs) forming the walls of arteries and arterioles generate the myogenic response (14). Increases in intraluminal pressure activate TRPM4 (transient receptor potential melastatin 4) channels, allowing an influx of Na+ ions that depolarize the SMC plasma membrane to initiate Ca2+ influx through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and engage contractile pathways (16–18). The depolarizing effects of TRPM4 channels are balanced by hyperpolarizing K+ currents primarily conducted by voltage-dependent K+ (Kv) channels, large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BK) channels, and inwardly rectifying K+ (KIR) channels (19, 20). In the CADASIL mouse model, increased Kv channel current density in SMCs accounts for diminished myogenic tone (15). The electrophysiological properties of SMCs from Col4a1 mutant mice have not been reported.

Here, we show that the myogenic response of cerebral pial arteries from Col4a1+/G394V mice was dramatically impaired in an age-dependent manner. In contrast to CADASIL models, K+ currents in SMCs from Col4a1+/G394V mice were not increased compared to controls. Instead, we found that the loss of myogenic tone was associated with decreased activity of inward Na+ currents conducted by TRPM4 channels. TRPM4 currents were restored by supplying exogenous phosphatidylinositol 4,5 bisphosphate (PIP2), a minor membrane phospholipid that is a necessary co-factor for TRPM4 activity (21, 22), and by selective blockade of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), an enzyme that depletes PIP2 by converting it to phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3). Further, inhibition of PI3K activity and blockade of upstream transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) receptors rescued myogenic tone in arteries from 12-mo-old mutant mice. We conclude that age-dependent cerebral vascular dysfunction in Col4a1+/G394V mice is caused by the loss of depolarizing TRPM4 currents due to PIP2 depletion. Conversion of PIP2 to PIP3 by PI3K, acting downstream of TGF-β receptors, accounts for diminished PIP2 levels in SMCs. Our findings reveal a mechanism of age-dependent cerebral vascular dysfunction and identify PI3K and TGF-β receptors as therapeutic targets for some forms of cSVDs.

Results

Cerebral Arteries from Middle-Aged Col4a1+/G394V Mice Fail to Generate Myogenic Tone.

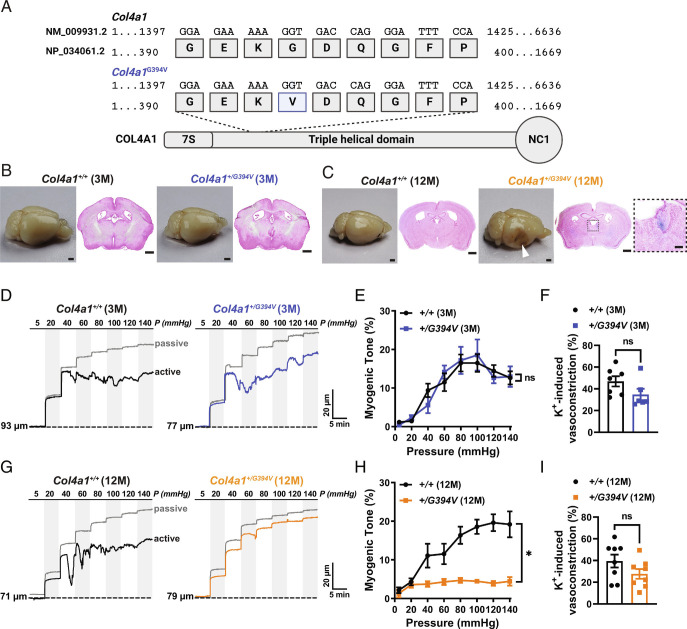

Mutant mice used for this study harbor a point mutation in the gene sequence that results in the substitution of G for V at position 394 of the polypeptide (Fig. 1A). mice that were 3 (young adult) or 12 (middle-aged) mo old were included in our study design. Both male and female mice were used for all experiments, and no sex-specific differences were detected. Histological examination of Prussian blue-stained brain sections showed that the brains of 3-mo-old Col4a1+/G394V mice (Fig. 1B) lacked ICH, but loss of brain tissue resulting from hemorrhagic events and evidence of spontaneous ICH was present in brains from 12-mo-old Col4a1+/G394V mice (Fig. 1C ).

Fig. 1.

Cerebral arteries from 12-mo-old Col4a1+/G394V mice fail to develop myogenic tone. (A) Schematic representation of COL4A1 showing the position of the Col4a1G394V mutation. (B and C) Representative images of perfusion-fixed brains and coronal brain sections stained with Prussian blue and Nuclear Fast Red from 3-mo-old (B) and 12-mo-old (C) Col4a1+/+ and Col4a1+/G394V mice. Arrowhead indicates a region with loss of brain tissue secondary to a hemorrhagic event. Enlarged region in the inset shows an example of spontaneous ICH. Scale = 1 mm. Inset scale = 200 µm. Representative of four mice per group. (D) Typical recordings of the inner diameter of isolated cerebral arteries from 3-mo-old Col4a1+/+ and Col4a1+/G394V mice showing the myogenic response to increases in intraluminal pressure (active) and the dilation of the same arteries when extracellular Ca2+ has been removed (passive). (E) Summary of myogenic tone, expressed as mean ± SEM, as a function of intraluminal pressure. n = 6 to 7 arteries from six animals per group. ns = not significant, two-way ANOVA. (F) Summary data showing vasoconstriction of isolated cerebral arteries from 3-mo-old Col4a1+/+ and Col4a1+/G394V mice in response to 60 mM KCl. n = 6 to 7 arteries from six animals per group. ns = not significant, unpaired t test. (G) Representative traces of the myogenic response and passive diameter of isolated cerebral arteries from 12-mo-old Col4a1+/+ and Col4a1+/G394V mice. (H) Summary of myogenic tone expressed as mean ± SEM as a function of intraluminal pressure. n = 8 arteries from five or six animals per group. *P < 0.05, two-way ANOVA. (I) Summary data showing vasoconstriction of isolated cerebral arteries from 12-mo-old Col4a1+/+ and Col4a1+/G394V mice in response to 60 mM KCl. n = 8 arteries from five or six animals per group. ns = not significant, unpaired t test.

Established pressure myography techniques (23) were used to investigate the development of spontaneous myogenic tone in cerebral pial arteries from Col4a1+/G394V mice. Initially, changes in the diameters of cannulated cerebral arteries were recorded as intraluminal pressure was increased in a stepwise manner from 5 to 140 mmHg, and the luminal diameter during active muscular contraction was recorded at each pressure. After this challenge, the pressure was returned to 5 mmHg, vessels were superfused with a Ca2+-free solution, and changes in diameter in response to increases in pressure were again recorded to determine the passive response—the diameter in the absence of muscular contraction. The myogenic tone was calculated as the difference in active versus passive diameter normalized to the passive diameter. Arteries from 3-mo-old mice from both groups began to constrict when pressures within the physiological range (i.e., 40 mmHg and above) were applied, and the myogenic tone did not differ (Fig. 1 D and E). In addition, vasoconstriction in response to the application of a high concentration of extracellular K+ (60 mM) was applied to collapse K+ gradients and directly depolarize SMC plasma membranes did not differ between cerebral arteries from 3-mo-old control and mutant mice (Fig. 1F). In contrast, arteries isolated from 12-mo-old Col4a1+/G394V mice barely constricted across all levels of applied pressure, and the myogenic tone was significantly lower compared to 12-mo-old Col4a1+/+ littermates (Fig. 1 G and H). These data demonstrate that cerebral arteries from Col4a1+/G394V mice lose the ability to develop myogenic tone during aging. Vasoconstriction in response to elevated [K+] did not differ between 12-mo-old Col4a1+/+ and Col4a1+/G394V mice (Fig. 1I), indicating that voltage-dependent Ca2+ influx and fundamental contractile mechanisms were not grossly impaired in 12-mo-old Col4a1+/G394V mice. Passive dilation of cerebral arteries in response to increases in intraluminal pressure did not differ between 12-mo-old Col4a1+/+ and Col4a1+/G394V mice (Fig. 1 and SI Appendix, Fig. S1), indicating that changes in vascular compliance do not account for impaired myogenic tone in mutant mice. The myogenic tone of cerebral arteries in which endothelial cell function had been disrupted by the passage of air through the lumen was also assessed. Pressure-induced constriction was significantly less in endothelium-denuded arteries from 12-mo-old Col4a1+/G394Vcompared to Col4a1+/+ littermates (Fig. 1 and SI Appendix, Fig. S2), demonstrating that that impaired myogenic tone in these animals is due to SMC dysfunction.

Loss of Myogenic Tone in Cerebral Arteries from Middle-Aged Col4a1+/G394V Mice Is Not Attributable to Increases in SMC K+ Channel Currents.

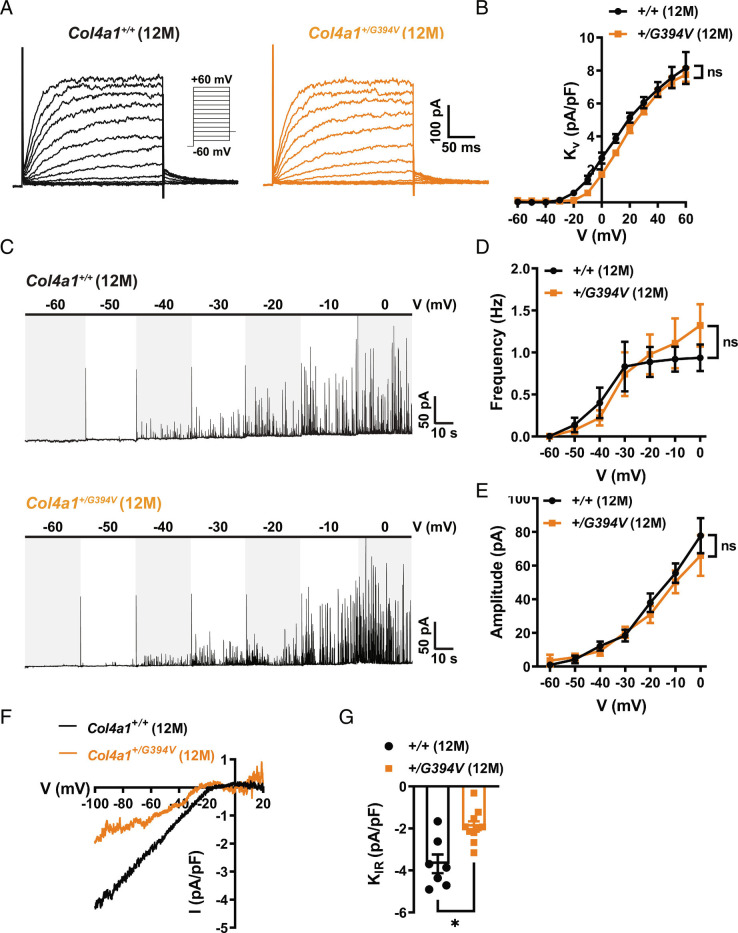

Impaired myogenic tone in cerebral arteries from CADASIL cSVD mice is due to elevated Kv current density in SMCs (15). To determine whether this mechanism also accounts for impaired myogenic tone in 12-mo-old Col4a1+/G394V mice, we measured K+ channel currents in cerebral artery SMCs using patch-clamp electrophysiology. To record Kv currents, freshly isolated SMCs were patch-clamped in the amphotericin B perforated configuration in the presence of the selective BK channel blocker paxillin (1 µM), and voltage-dependent currents were evoked by the application of a series of voltage steps from −60 to +60 mV from a holding potential of −80 mV. The voltage step protocol was repeated in the presence of the Kv channel blocker 4-aminopyridine (5 mM), and Kv current amplitude was determined at each potential by subtraction. We found that Kv current amplitude did not differ between SMCs from Col4a1+/+ and Col4a1+/G394V mice at any applied membrane potentials (Fig. 2 A and B). These data indicate that the mechanisms that impair the myogenic tone in 12-mo-old Col4a1+/G394V mice differ from the CADASIL cSVD model.

Fig. 2.

Loss of myogenic tone in cerebral arteries from middle-aged Col4a1+/G394V mice is not attributable to increased SMC K+ channel currents. (A) Example recording of 4-aminopyridine (5 mM)-sensitive Kv currents elicited by application of voltage pulses (250 ms) from −60 to + 60 mV in the presence of the BK channel blocker paxilline (1 μM). (B) Summary data of KV current at each command potential, normalized to cell capacitance (pA/pF). n = 8 to 10 cells from three animals per group. ns = not significant, two-way ANOVA. (C) Representative traces of STOCs recorded over a series of membrane potentials (−60 to 0 mV). (D and E) Summary data for STOC frequency (D) and amplitude (E) at each command potential. n = 11 to 14 cells from six or seven animals per group. ns = not significant, two-way ANOVA. (F) Representative recording of BaCl2-sensitive KIR whole-cell currents evoked by adding 60 mM KCl to the bath as voltage ramps (−100 to +20 mV) were applied. (G) Summary data of KIR current amplitude recorded at −100 mV and normalized to cell capacitance (pA/pF). n = 7 to 10 cells from four or six animals per group. *P < 0.05, unpaired t test.

BK channel activity has a powerful hyperpolarizing effect on the SMC membrane potential that could account for the lack of myogenic tone in cerebral arteries from 12-mo-old Col4a1+/G394V mice (19, 20). Under physiological conditions, Ca2+ sparks—transient, localized Ca2+ signals generated by the release of Ca2+ from the SR into the cytosol through RyRs—activate clusters of BK channels on the plasma membrane to produce large-amplitude spontaneous transient outward currents (STOCs) (19). We compared BK channel activity between SMCs from 12-m-old Col4a1+/+ and Col4a1+/G394V mice using the amphotericin B perforated patch-clamp configuration. We found that the frequency and amplitude of STOCs recorded over a range of command potentials (−60 to 0 mV) did not differ between groups, indicating that elevated BK channel activity does not account for the loss of myogenic tone in 12-mo-old Col4a1+/G394V mice (Fig. 2 C–E).

An increase in KIR channel activity could also account for the loss of myogenic tone in 12-mo-old Col4a1+/G394V mice. Conventional whole-cell patch-clamp electrophysiology was used to measure KIR current density in cerebral artery SMCs from 12-mo-old Col4a1+/+ and Col4a1+/G394V mice. KIR currents were evoked by applying a high concentration of K+ (60 mM) to the bath solution during voltage ramps (−100 to +20 mV). Voltage ramps were repeated in the presence of the selective KIR channel blocker BaCl2 (10 μM), and KIR current amplitude was determined by subtraction. KIR current density was significantly smaller in SMCs from 12-mo-old Col4a1+/G394V mice compared with Col4a1+/+ animals (Fig. 2 F and G). However, decreases in K+ current density depolarize the SMC plasma membrane and increase vasoconstriction. Therefore, loss of KIR channel activity does not account for the diminished myogenic tone of cerebral arteries from 12-mo-old Col4a1+/G394V mice.

TRPM4 Currents Are Diminished in Cerebral Artery SMCs from Middle-Aged Col4a1+/G394V Mice.

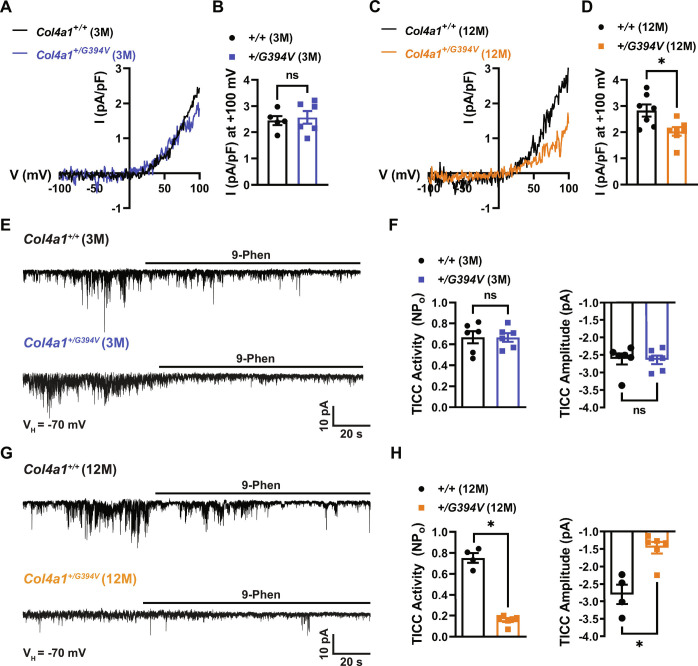

TRPM4 channel activity is necessary for pressure-induced SMC depolarization and the development of myogenic tone in cerebral arteries (16–18). TRPM4 channels are activated by high intracellular [Ca2+], selective for monovalent cations (i.e., Na+ and K+), and impermeant to Ca2+ ions (24, 25). Patch-clamp electrophysiology was used to determine whether TRPM4 activity was diminished in SMCs from 12-mo-old Col4a1+/G394V mice. SMCs were patch-clamped in the conventional whole-cell configuration with a high [Ca2+] intracellular solution to activate TRPM4 channels directly. Currents were recorded as voltage ramps (−100 to +100 mV) were applied, and the ramp protocol was repeated in the presence of the TRPM4 blocker 9-phenanthrol (30 μM). The TRPM4 component of the whole-cell current was determined by subtraction. Ion substitution studies have demonstrated that Ca2+-activated, 9-phenanthrol-sensitive currents recorded in this manner are carried by Na+ ions (16, 24, 25). These currents were also blocked by the recently described (26, 27) selective TRPM4 inhibitor 4-chloro-2-[2-(naphthalene-1-yloxy) acetamido] benzoic acid (NBA), providing substantial evidence that these are bona fide TRPM4 currents (Fig. 3 and SI Appendix, Fig. S1). We found that conventional whole-cell TRPM4 currents recorded from SMCs from 3-mo-old mice did not differ between mutants and controls (Fig. 3 A and B). In contrast, whole-cell TRPM4 currents were significantly blunted in SMCs from 12-mo-old Col4a1+/G394V mice compared with controls (Fig. 3 C and D).

Fig. 3.

TRPM4 currents are diminished in cerebral artery SMCs from 12-mo-old Col4a1+/G394V mice. (A) Typical I–V plots of whole-cell TRPM4 currents in SMCs from 3-mo-old mice produced as voltage ramps (−100 to +100 mV) were applied. Currents were evoked by including 200 μM free Ca2+ in the intracellular solution. (B) Summary of TRPM4 current amplitude at +100 mV normalized to cell capacitance. n = 5 to 6 cells from four or five animals per group. ns = not significant, unpaired t test. (C) Representative I–V plots of whole-cell TRPM4 currents in SMCs from 12-mo-old mice. (D) Summary of TRPM4 current amplitude at +100 mV normalized to cell capacitance in 12-mo-old mice. n = 7 cells from five animals per group. *P < 0.05, unpaired t test. (E) Typical recordings of whole-cell TICCs in SMCs from 3-mo-old mice voltage-clamped at −70 mV. TICCs were inhibited by the TRPM4 blocker 9-phenanthrol (30 μM). (F) Summary of total TICC activity and amplitude. n = 6 cells from three animals per group. ns = not significant, unpaired t test. (G) Representative recordings of TICCs in SMCs from 12-mo-old mice. (H) Summary of total TICC activity and amplitude. n = 4 to 6 cells from three animals per group. *P < 0.05, unpaired t test.

In additional experiments designed to study the activity of TRPM4 channels under near-physiological conditions, TRPM4-dependent transient inward cation currents (TICCs) were recorded from SMCs using an intracellular solution that minimally disrupted intracellular Ca2+ signaling (28). We found that TICCs recorded from SMCs from 3-mo-old mice did not differ between groups (Fig. 3 E and F). In contrast, TICC activity and amplitude were significantly lower in SMCs from 12-mo-old Col4a1+/G394V mice compared with Col4a1+/+ animals (Fig. 3 G and H). Prior studies used ion substitution to show that TICCs are Na+ currents and are inactivated by the downregulation of TRPM4 expression (28, 29). TICCs were also inhibited by NBA (Fig. 3 and SI Appendix, Fig. S1), providing further evidence that these currents depend on TRPM4 activity. These findings suggest that diminished TRPM4 channel activity accounts for the loss of myogenic tone in cerebral arteries from middle-aged Col4a1+/G394V mice.

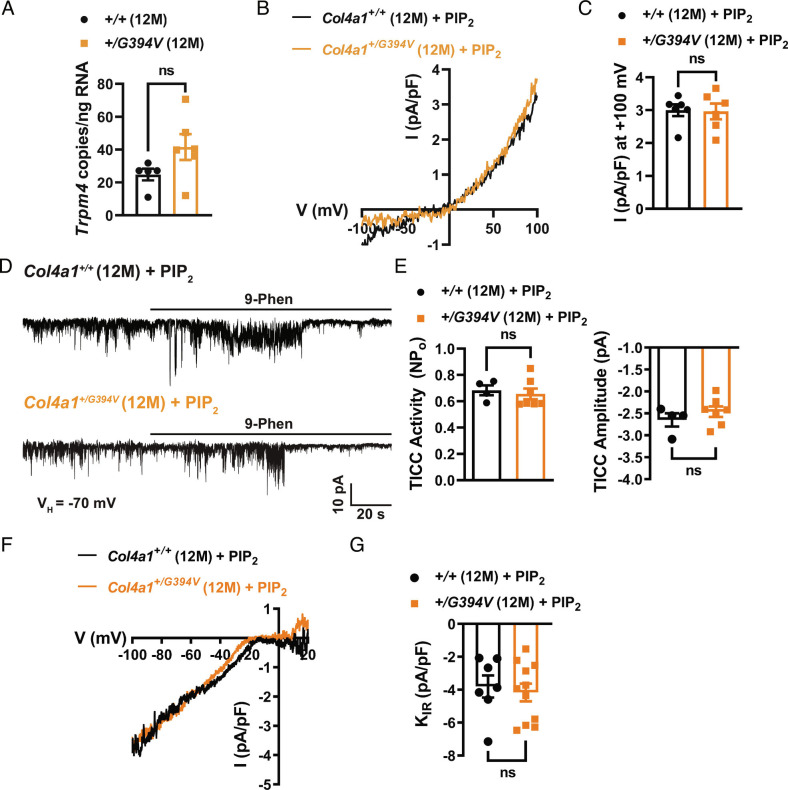

Impaired TRPM4 activity is restored by exogenous PIP2.

Diminished TRPM4 activity in SMCs from 12-mo-old Col4a1+/G394V mice could result from decreased Trpm4 expression. However, we used droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) to show that the number of Trpm4 transcripts in cerebral arteries from 12-mo-old Col4a1+/+ and Col4a1+/G394V mice was not different (Fig. 4A). We therefore investigated dysregulation of TRPM4 activity using patch-clamp electrophysiology.

Fig. 4.

Impaired TRPM4 activity is restored by exogenous PIP2. (A) ddPCR assay for Trpm4 mRNA (as transcript copies/ng total RNA) in cerebral arteries. n = 5 or 6 animals. ns = not significant, unpaired t test. (B) Typical recordings of whole-cell TRPM4 currents in SMCs from 12-mo-old Col4a1+/+ and Col4a1+/G394V mice with diC8-PIP2 (10 μM) added to the intracellular solution. (C) Summary of TRPM4 current amplitude at +100 mV, normalized to cell capacitance (pA/pF). n = 6 cells from four animals per group. ns = not significant, unpaired t test. (D) Representative recordings of TICCs in SMCs from 12-mo-old Col4a1+/+ and Col4a1+/G394V mice with diC8-PIP2 (10 μM) added to the intracellular solution. (E) Summary of total TICC activity and amplitude. n = 4 to 7 cells from three or four animals per group. ns = not significant, unpaired t test. (F) Representative recording of BaCl2-sensitive KIR whole-cell currents recorded in SMCs from 12-mo-old animals with diC8-PIP2 (10 μM) added to the intracellular solution. (G) Summary data of KIR current amplitude recorded at −100 mV and normalized to cell capacitance (pA/pF). n = 7 to 11 cells from three animals per group. ns = not significant, unpaired t test.

The activities of TRPM4 and KIR channels are diminished in SMCs from 12-mo-old Col4a1+/G394V mice. Both channels require PIP2 for activity (21, 22), suggesting that PIP2 depletion could underlie the defects. We tested this idea by adding exogenous PIP2 to the intracellular solution during patch-clamp electrophysiology experiments. We found that when diC8-PIP2 (10 μM) was added to the intracellular solution, conventional whole-cell TRPM4 currents (Fig. 4 B and C) and TICCs recorded from cerebral artery SMCs from 12-mo-old Col4a1+/G394V mice (Fig. 4 D and E) were restored to the levels recorded from age-matched Col4a1+/+ mice. Supplying PIP2 via the intracellular solution also increased KIR current density in SMCs from Col4a1+/G394V mice to the level of control animals (Fig. 4 F and G). These data suggest that PIP2 levels are lower in SMCs from 12-mo-old Col4a1+/G394V mice compared to age-matched Col4a1+/+ mice, leading to diminished TRPM4 and KIR channel activity.

Inhibition of PI3K and TGF-β Receptors Rescues Myogenic Tone.

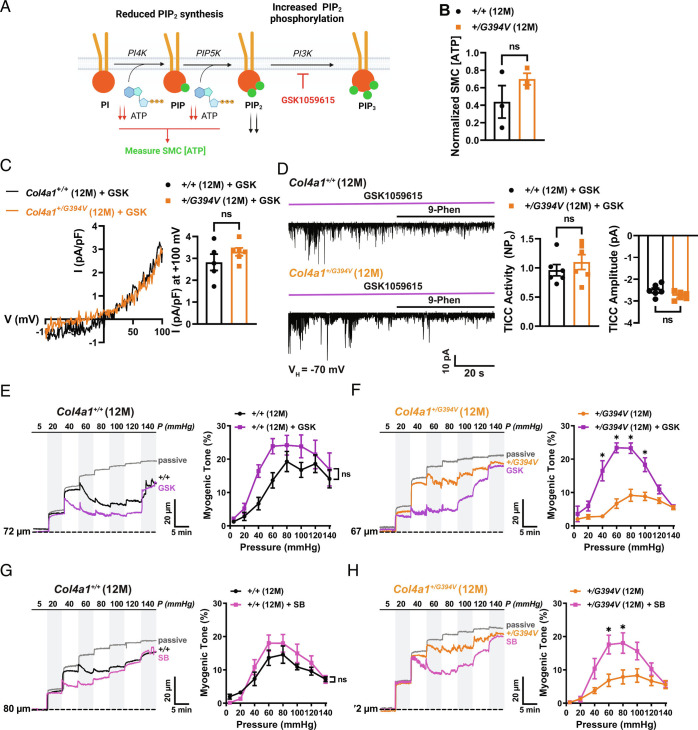

The steady-state level of PIP2 is controlled by the relative activities of biosynthesis and removal pathways (Fig. 5A). PIP2 is produced through sequential ATP-dependent phosphorylation of phosphatidylinositol (PI) by the enzymes phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase (PI4K) and phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5 kinase (PIP5K). Prior studies report that diminished levels of ATP underlie decreased synthesis of PIP2 and reduced KIR channel activity in brain capillary endothelial cells from CADASIL and 5xFAD Alzheimer’s disease mice (30, 31). We measured ATP levels in freshly isolated cerebral artery SMCs from 12-mo-old control and Col4a1+/G394V mice using a combined luciferase/fluorescence assay that demonstrated a broad dynamic range and high sensitivity (Fig. 5 and SI Appendix, Fig. S1). SMC ATP levels did not differ between 12-mo-old control and Col4a1+/G394V mice (Fig. 5B), suggesting that PIP2 synthesis is not limited by ATP availability in the mutant animals. We next considered pathways that remove or modify PIP2. One of the ways that PIP2 levels can be reduced is by PI3K-induced phosphorylation to PIP3. To investigate this possibility, we treated SMCs with the potent and selective PI3K inhibitor GSK1059615 (10 nM) (32) and found that whole-cell TRPM4 currents and TICCs recorded from SMCs isolated from 12-mo-old Col4a1+/G394V were restored to control levels by PI3K inhibition (Fig. 5 C and D). These data indicate that elevated PI3K activity accounts for diminished PIP2 levels and decreased TRPM4 currents in SMCs from 12-mo-old Col4a1+/G394V mice.

Fig. 5.

Inhibition of PI3K and TGF-β receptors rescues myogenic tone. (A) PIP2 synthesis and removal pathways. (B) Normalized SMC [ATP]. n = 3 animals per group. ns = not significant, unpaired t test. (C) Typical recordings and summary data of whole-cell TRPM4 currents in SMCs from 12-mo-old Col4a1+/+ and Col4a1+/G394V mice treated with the PI3K blocker GSK1059615 (10 nM). Inhibition of PI3K activity with GSK1059615 (10 nM) restores whole-cell TRPM4 currents in SMCs from 12-mo-old Col4a1+/G394V mice to the level of controls. n = 5 to 6 cells from three or four animals per group. ns = not significant, unpaired t test. (D) Inhibition of PI3K activity with GSK1059615 (10 nM) restores TICC activity and amplitude recorded from SMCs from 12-mo-old Col4a1+/G394V mice to the level of controls. n = 6 cells from four animals per group. ns = not significant, unpaired t test. (E and F) Representative traces (E) and summary data (F) of the myogenic response of cerebral arteries from 12-mo-old Col4a1+/+ and Col4a1+/G394V mice before and after blocking PI3K with GSK1059615 (10 nM, 30 min). n = 6 arteries from four or five animals per group, *P < 0.05, ns = not significant, two-way ANOVA. (G and H) Representative traces (G) and summary data (H) of the myogenic response of cerebral arteries from 12-mo-old Col4a1+/+ and Col4a1+/G394V mice before and after blocking TGF-β receptors with SB-431542 (1 μM, 30 min). n = 5 to 6 arteries from three animals per group, *P < 0.05, ns = not significant, two-way ANOVA.

Deficient TRPM4 channel activity in SMCs from 12-mo-old Col4a1+/G394V mice is repaired by blocking PI3K. Therefore, we used pressure myography to determine whether the PI3K pathway is also linked to the loss of myogenic tone in cerebral arteries from 12-mo-old Col4a1+/G394V mice. Arteries were studied before and after incubation with GSK1059615 (10 nM) for 30 min. This treatment slightly increased the contractility of arteries from 12-mo-old Col4a1+/+ mice, but differences in myogenic tone did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 5E). In contrast, blockade of PI3K dramatically increased the contractility of cerebral arteries from 12-mo-old Col4a1+/G394V mice. The myogenic tone within the physiological range (40 to 100 mmHg) was significantly elevated and restored to the levels observed for arteries from control animals (Fig. 5F). However, at higher levels of intraluminal pressure (120 and 140 mmHg), the myogenic tone was not improved by PI3K inhibition (Fig. 5F). These data suggest that elevated PI3K activity in cerebral arteries from 12-mo-old Col4a1+/G394V mice blunts the development of myogenic tone over a physiologically relevant range of pressures. Higher pressures, such as those encountered during systemic hypertension, override the rescue effect of PI3K inhibition.

Data presented so far support a model in which elevated PI3K activity decreases SMC PIP2 levels and TRPM4 activity to impair the development of myogenic tone in cerebral arteries from 12-mo-old Col4a1+/G394V mice. But how does a point mutation in Col4a1 lead to elevated PI3K activity? Basement membranes sequester and regulate the bioavailability of extracellular regulatory proteins and growth factors and release these substances in response to environmental cues. One of these factors, TGF-β, can stimulate PI3K activity (33). We therefore investigated the effects of acute TGF-β receptor blockade on the development of myogenic tone. The myogenic tone was measured in cerebral arteries from 12-mo-old control and Col4a1+/G394V mice before and after treatment (30 min) with SB-431542 (1 μM), a potent and selective inhibitor of TGF-β type I receptors (34). The effects of this treatment were strikingly similar to the impact of the PI3K blockade. The contractility of arteries from Col4a1+/+ mice was slightly increased in the presence of SB-431542, but the difference in myogenic tone was not statistically significant (Fig. 5G). The myogenic tone of arteries from 12-mo-old Col4a1+/G394V mice was enhanced at pressures in the normal range for nonhypertensives, but the myogenic tone was not improved at higher pressure levels (Fig. 5H). These data suggest that the blockade of TGF-β receptors restores the myogenic tone to arteries from Col4a1+/G394V mice at normal pressure levels, but the myogenic response remains impaired at hypertensive pressure. Addition of GSK1059615 to arteries treated with SB-431542 did not further increase the myogenic tone in arteries from either 12-mo-old Col4a1+/G394V or control mice (Fig. 5 and SI Appendix, Fig. S2), suggesting that PI3K activity acts downstream of TGF-β receptors. In control experiments, we found that DMSO, the vehicle for both GSK1059615 and SB-431542, had no effect on the myogenic tone of cerebral vessels from either group (Fig. 5 and SI Appendix, Fig. S3).

Discussion

Autosomal dominant mutations in COL4A1 and COL4A2 cause cSVD and related brain injuries, including ICH, porencephaly, and white matter lesions (3, 4), but the mechanistic underpinnings of this pathology are unknown. Here, we investigated how a specific point mutation in Col4a1 damages small arteries in the brain during aging. Our findings show that the vascular myogenic response, a process that is vital for the autoregulation of cerebral blood flow, was deficient in cerebral arteries from middle-aged, but not young adult, Col4a1+/G394V mice. Electrophysiological analysis of SMCs from these animals revealed that the loss of myogenic tone was associated with diminished activity of TRPM4 cation channels. TRPM4 currents were rescued by dialyzing SMCs with PIP2 or by preventing the conversion of PIP2 to PIP3 by blocking PI3K. Our data also show that inhibition of PI3K or TGF-β receptors restored the myogenic tone of cerebral arteries from middle-aged Col4a1+/G394V mice. We conclude that the loss of myogenic tone in arteries from 12-mo-old Col4a1+/G394V mice is due to pathological overstimulation of TGF-β receptors that drives increased PI3K activity to deplete PIP2 and diminish cation influx through TRPM4 channels. Loss of TRPM4’s depolarizing influence decreases voltage-dependent Ca2+ influx to reduce SMC contractility and myogenic vasoconstriction. These findings reveal an age-dependent mechanism of cSVD.

Disrupted PIP2 metabolism has emerged as a leading pathogenic process in multiple types of cSVDs (35). In prior studies, PIP2 deficits were shown to reduce KIR channel activity in brain capillary endothelial cells and impair somatosensory-induced functional hyperemia in CADASIL cSVD and 5xFAD familial Alzheimer’s disease mice (30, 31). Here, we demonstrated that pathologically lowered PIP2 levels in SMCs disrupt TRPM4 cation channels and impair the development of myogenic tone in cerebral arteries from middle-aged Col4a1+/G394V mice. Interestingly, KIR channel activity and PIP2 levels were not altered in SMCs and cerebral arterial endothelial cells from CADASIL and 5xFAD mice (30, 31), suggesting cellular heterogeneity in PIP2 defects in different types of cSVD. The effects of cSVDs on PIP2 levels in other types of cells involved in cerebral blood flow regulation, such as pericytes, microglia, and astrocytes, have not been reported, but such data may be enlightening. Diminished intracellular ATP levels and impaired PIP2 synthesis reportedly account for the deficit in brain capillary endothelial cells (30, 31). However, ATP levels in SMCs from Col4a1+/G394V mice did not differ from controls. Instead, our data indicate that elevated PI3K activity and conversion of PIP2 to PIP3 are responsible for the deficit. Thus, although multiple forms of cSVDs may share PIP2 insufficiency as a core pathogenic mechanism, the pathways to depletion differ. Pharmacological manipulation of PIP2 may prove to be a breakthrough treatment option for multiple types of cSVDs. Further investigations into fluctuations of brain vascular PIP2 levels during normal aging and sporadic forms of cSVDs are essential.

Elevated TGF-β signaling has been shown to contribute to the ocular pathogenesis of Col4a1 mutant mice (36). Acute block of TGF-β receptors repaired defective myogenic tone of cerebral arteries from middle-aged Col4a1+/G394V mice, implicating this pathway in the deficiency. Our findings also suggest that TGF-β acts upstream of PI3K in Col4a1+/G394V mice. A prior report shows that TGF-β receptors bind the ubiquitin ligase TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) (37). When activated, TRAF6 stimulates Lys63-linked ubiquitylation of the p85α (regulatory) subunit of PI3K, activating the catalytic subunit and increasing the conversion of PIP2 to PIP3 (37). Disrupted TGF-β signaling is also associated with cerebral autosomal recessive arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CARASIL), a familial form of cSVD that is caused by mutations in HTRA1 (38). HTRA1 encodes a serine protease localized to the extracellular matrix (ECM) that normally contributes to the restraint of TGF-β signaling, and CARASIL-causing mutations disinhibit these pathways (38). It is not known if elevated TGF-β signaling associated with CARASIL also increases PI3K activity to deplete PIP2 and disrupt ion channel activity, but this outcome is possible and potentially exciting. It is also not known how COL4A1 mutations increase TGF-β signaling. The production and maturation of TGF-β and activation of corresponding signaling cascades are complex processes, suggesting several possibilities for the defect. TGF-β ligand and latency-associated protein (LAP) are expressed as single pre-pro precursor polypeptides that form homodimers and are subsequently cleaved by proteases during posttranslational processing (39). The ligand dimer noncovalently associates with LAP, this complex is covalently attached to latent TGF-β-binding protein (LTBP), and the entire assembly is secreted from the cell and sequestered by the ECM as an inactive complex (39). TGF-β ligand is liberated to bind its receptors and initiate signaling cascades by several stimuli, including activation of integrins and/or modification of the ECM by metalloproteases (39). Any of these processes could be affected by Col4a1 mutations in a way that increases TGF-β bioavailability. For example, it is conceivable that defects in the structure of the basement membrane associated with the incorporation of mutant collagen, in conjunction with the insults of normal aging, impair the sequestration of the TGF-β LAP complex in 12-mo-old Col4a1+/G394V mice, leading to increased availability, activation of the cognate signaling cascades, and ultimately, vascular dysfunction.

Even within monogenetic forms of familial cSVD, the pathogenic mechanisms and impacts of the disease widely vary. For example, Col4a1+/G498V mutant mice displayed cSVD-like pathology in young adult animals together with hypermuscularity and elevated pressure-induced contractility of pericyte-ensheathed transitional vascular segments bridging capillaries and arterioles in the retinal vasculature (40, 41). Here, we show that cerebral vascular dysfunction in Col4a1+/G394V mice is observed from middle age and involves the loss of pressure-induced constriction of cerebral arteries caused by faulty TRPM4 cation channels in SMCs. These and other examples show that cSVDs are a cluster of related disorders with similar outcomes arising from different processes rather than a single, monolithic disease. Accordingly, a targeted, precision medicine-based approach may be the best strategy for developing effective therapeutics for cSVDs and associated dementias.

Materials and Methods

Chemical and Reagents.

Unless otherwise specified, chemicals and other reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, Inc.

Animals.

Young adult (3-mo-old) and middle-aged (12-mo-old) male and female littermate Col4a1+/+ and Col4a1+/G394V mice were used in this study. The Col4a1G394V mutation was backcrossed to C57BL/6J mice for over 20 generations (13, 42). Animals were maintained in individually ventilated cages (≤5 mice/cage) with ad libitum access to food and water in a room with controlled 12-h light and dark cycles. All animal care procedures and experimental protocols involving animals complied with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the University of Nevada, Reno, and UCSF. mice were euthanized by decapitation and exsanguination under isoflurane anesthesia (Baxter Healthcare). Brains were isolated and placed in ice-cold Ca2+-free physiological saline solution (Mg-PSS, containing 140 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, and 10 mM glucose (pH 7.4, NaOH), supplemented with 0.5% bovine serum albumin).

Brain Histological Analysis.

Anesthetized mice were transcardially perfused with PBS, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (Fisher) dissolved in PBS. Whole brain images were acquired using a digital camera (Sony α6000; Sony). Brains were postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h, cryoprotected in 30% sucrose in PBS, and embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound (Fisher). Coronal cryosections (35 µm) regularly spaced (500 µm) along the rostrocaudal axis were stained with a Prussian blue and Nuclear Fast Red stain kit (Abcam). Images were acquired with a BZ-X700 microscope using BZ-X Viewer 1.3.0.5 software and stitched with BZ-X Analyzer 1.3.0.3 software (Keyence).

Isolation of Cerebral Arteries and SMCs.

Cerebral pial arteries (middle cerebral, posterior cerebral, and superior cerebellar) were gently removed from the brain and washed in Mg-PSS. Native SMCs for patch-clamp experiments were obtained by initially digesting isolated arteries in 1 mg/mL papain (Worthington Biochemical Corporation), 1 mg/mL dithiothreitol (DTT), and 10 mg/mL BSA in Mg-PSS at 37 °C for 12 min, followed by a 14-min incubation with 1 mg/mL type II collagenase (Worthington Biochemical Corporation). A single-cell suspension was prepared by washing digested arteries three times with Mg-PSS and triturating with a fire-polished glass pipette. All cells used for this study were freshly dissociated on the day of experimentation.

Pressure Myography.

The current best practices guidelines for pressure myography experiments were followed (43). Arteries were mounted between two glass cannulas (outer diameter, 40 to 50 μm) in a pressure myograph chamber (Living Systems Instrumentation) and secured by a nylon thread. Intraluminal pressure was controlled using a servo-controlled peristaltic pump (Living Systems Instrumentation). Preparations were visualized with an inverted microscope (Accu-Scope Inc.) coupled to a USB camera (The Imaging Source LLC). Changes in luminal diameter were assessed using IonWizard software (version 7.2.7.138; IonOptix LLC, Westwood, MA, USA). Arteries were bathed in warmed (37 °C), oxygenated (21% O2, 6% CO2, 73% N2) PSS (119 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 21 mM NaHCO3, 1.17 mM MgSO4, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1.18 mM KH2PO4, 5 mM glucose, 0.03 mM EDTA) at an intraluminal pressure of 5 mmHg. Following equilibration for 15 min, intraluminal pressure was increased to 110 mmHg, and vessels were stretched to their approximate in vivo length, after which pressure was reduced back to 5 mmHg for an additional 15 min. Vessel viability was assessed for each preparation by evaluating vasoconstrictor responses to high extracellular [K+] PSS, made isotonic by adjusting the [NaCl] (60 mM KCl, 63.7 mM NaCl). Arteries that showed less than 10% constriction in response to elevated [K+] were excluded from further investigation.

The myogenic tone was assessed by raising the intraluminal pressure stepwise from 5 mmHg to 20 mmHg and then to 140 mmHg in 20 mmHg increments. The active diameter was obtained by allowing vessels to equilibrate for at least 5 min at each pressure or until a steady-state diameter was reached. Following completion of the pressure-response study, intraluminal pressure was lowered to 5 mmHg, and arteries were superfused with Ca2+-free PSS supplemented with EGTA (2 mM) and the voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel blocker diltiazem (10 μM) to inhibit SMC contraction, after which passive diameter was obtained by repeating the stepwise increase in intraluminal pressure. The myogenic tone at each pressure step was calculated as myogenic tone (%) = [1 – (active lumen diameter/passive lumen diameter)] × 100. For some experiments, the endothelium was disrupted by passing air bubbles through the lumen as previously described (43).

Electrophysiological Recordings.

Enzymatically isolated native SMCs were transferred to a recording chamber (Warner Instruments) and allowed to adhere to glass coverslips for 15 min at room temperature. Recording electrodes (3 to 5 MΩ) were pulled and polished. Currents were recorded at room temperature using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices) equipped with an Axon CV 203BU headstage and Digidata 1440A digitizer (Molecular Devices) for all patch-clamp electrophysiology experiments.

The bathing solution composition for perforated-patch whole-cell recordings of KV currents and STOCs was 134 mM NaCl, 6 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, 10 mM HEPES, and 10 mM glucose at pH 7.4 (NaOH). The pipette solution contained 110 mM K-aspartate, 1 mM MgCl2, 30 mM KCl, 10 mM NaCl, 10 mM HEPES, and 50 µM EGTA at pH 7.2 (KOH). Amphotericin B (200 µg/mL) was included in the pipette solution of all perforated-patch recordings to allow electrical access. Perforation was deemed acceptable if series resistance was less than 50 MΩ. Whole-cell K+ currents were recorded using a step protocol (−60 to +60 mV in 10-mV, 250-ms steps) from a holding potential of −80 mV. The BK channel blocker paxilline (1 µM) was included in the bath solution when Kv currents were recorded. Whole-cell K+ currents were recorded in the absence and presence of 4-aminopyridine (5 mM), and the Kv component was determined by subtraction. Summary current–voltage (I–V) plots were generated using values obtained from the last 50 ms of each step. STOCs, produced by the efflux of K+ through BK channels, were recorded from SMCs voltage-clamped at a range of membrane potentials (−60 to 0 mV).

Conventional whole-cell patch-clamp electrophysiology was used to measure Ba2+-sensitive KIR currents in isolated cerebral artery SMCs. Currents were recorded by voltage-ramp protocol (−100 mV to +20 mV for 3,000 ms) from the holding potential of −30 mV. Voltage ramps were repeated every 10 s for 300 s. The composition of external bathing solution was 80 or 134 mM NaCl, 60 or 6 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM glucose, and 2 mM CaCl2 (PH 7.4). The pipette solution was of the following composition: 5 mM NaCl, 35 mM KCl, 100 mM K-gluconate, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM EGTA, 2.5 mM Na2- ATP, and 0.2 mM GTP (pH 7.2). The Kir channel currents were activated by increasing the extracellular K+ concentration from 6 to 60 mM (replacing Na+) and blocked using Ba2+ (10 µM).

Whole-cell TRPM4 currents were recorded in a bath solution consisting of 156 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 10 mM glucose, 10 mM HEPES, and 10 mM TEACl (pH 7.4, adjusted with NaOH). The patch pipette solution contained 156 mM CsCl, 8 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4, adjusted with NaOH), and a free Ca2+ concentration of 200 µM, adjusted using the appropriate amount of CaCl2 and EGTA, as determined with Max-Chelator software (WEBMAXC standard, available at https://somapp.ucdmc.ucdavis.edu/pharmacology/bers/maxchelator/webmaxc/webmaxcS.htm). Whole-cell cation currents were evoked by applying 400-ms voltage ramps from −100 to +100 mV from a holding potential of −60 mV. Voltage ramps were repeated every 2 s for 300 s. The selective TRPM4 inhibitor 9-phenanthrol (30 μM) or NBA (3 μM) was applied after the peak TRPM4 current was recorded (~60 s). Whole-cell TRPM4 current amplitude was expressed as the 9-phenanthrol or NBA-sensitive current at +100 mV.

TICCs were recorded using modified whole-cell patch-clamp conditions as described in our previous publication (28). The bath solution contained 140 mM NaCl, 5 mM CsCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM glucose, and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4, adjusted with NaOH). The pipette solution contained 20 mM CsCl, 87 mM K-aspartate, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM MgATP, 10 mM EGTA, and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.2, adjusted with CsOH). Cells were voltage-clamped at −70 mV, and TICC activity was calculated as the sum of the open channel probability (NPo) of multiple open states of 1.75 pA (44).

Isolation of RNA and ddPCR.

Total RNA was extracted from isolated cerebral arteries by homogenization in TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), followed by purification using a Direct-zol RNA microprep kit (Zymo Research) with on-column DNAse treatment. RNA concentration was determined using an RNA 6000 Pico Kit run on a Bioanalyzer 2100 using Agilent 2100 Expert Software (B.02.11; Agilent Technologies). RNA was converted to cDNA using iScript cDNA Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules). Quantitative ddPCR was performed using QX200 ddPCR EvaGreen Supermix (Bio-Rad), cDNA templates, and custom-designed primers for Trpm4 (NM_175130.4): 5′-TTCACGTACTCTGGCCGAAA-3′ (sense) and 5′-CGGGTAACGAGACTGTACACA-3′ (antisense). Generated droplet emulsions were amplified using a C100 Touch Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad), and the fluorescence intensities of individual droplets were measured using a QX200 Droplet Reader (Bio-Rad) running QuantaSoft (version 1.7.4; Bio-Rad). Analysis was performed using QuantaSoft Analysis Pro (version 1.0596; Bio-Rad).

Measurement of [ATP] in SMCs.

Cerebral artery SMCs were prepared by enzymatic digestion. The cell suspension was passed through a 70-µm cell strainer (VWR) to remove large debris, and the viable SMC concentration was determined by manual count using a hemocytometer and Trypan Blue staining. The intracellular (ATP) was determined by lysing the cells and quantifying luminescence produced by luciferase-induced conversion of ATP to light using the CellTiter-Glo Assay 3D (Promega). Approximately 5,000 SMCs were added to each reaction. To further ensure equal input of SMCs, the CellTiter-Glo 3D Assay was multiplexed with CellTox Green Assay (Promega), a fluorescent dye that selectively and quantitatively binds double-stranded DNA. Dye fluorescence is directly proportional to DNA concentration and the number of cells in each assay. ATP concentration (luminescence) was normalized to the number of cells (fluorescence) to determine intracellular ATP per cell. Luminescence and fluorescence (485Ex/538Em) were measured using a FlexStation 3 (Molecular Devices). A serial tenfold dilution of ATP (1 nM to 1 μM; 80 µl contains 8−14 to 8−11 moles of ATP, respectively) was measured to calibrate the linear working range of ATP detection. Data were expressed as the ratio of ATP luminescence/DNA fluorescence.

Statistical Analysis.

All summary data are presented as means ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed, and graphs were constructed using Prism version 9.3.1 (GraphPad Software). The value of n refers to the number of cells for patch-clamp electrophysiology experiments and arteries for myography experiments. Statistical analyses were performed using unpaired Student’s t tests or two-way ANOVA. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the NIH (NHLBI R35155008 and NIGMS P20GM130459 to S.E.; NINDS R01NS096173 to D.B.G.; and NINDS RF1NS110044 and R33NS115132 to D.B.G and S.E.). The Transgenic Genotyping and Phenotyping Core and the High Spatial and Temporal Resolution Imaging Core at the COBRE Center for Molecular and Cellular Signaling in the Cardiovascular System, University of Nevada, Reno are maintained by grants from NIH/NIGMS (P20GM130459 Sub#5451 and P20GM130459 Sub#5452). The University of California, San Francisco Department of Ophthalmology is supported by a Vision Core grant NEI P30EY002162 and by an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, NY.

Author contributions

E.Y., D.B.G., and S.E. designed research; E.Y., S.A., A.S.S., P.T., M.S., X.W., C.L.-D., and S.E. performed research; C.L.-D., D.B.G., and S.E. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; E.Y., S.A., A.S.S., P.T., X.W., and S.E. analyzed data; and E.Y., D.B.G., and S.E. wrote the paper.

Competing interest

The authors have patent filings to disclose, Drs. S.E. and D.B.G. have filed a provisional patent for the use of PI3 kinase inhibitors to treat cSVDs.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. T.A.L. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper or the SI Appendix. All supporting data have been deposited in a publicly available database (https://figshare.com/articles/figure/Yamasaki_et_al_PNAS_2022_Source_Data_Files_xlsx/21892776)

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Cannistraro R. J., et al. , CNS small vessel disease: A clinical review. Neurology 92, 1146–1156 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dichgans M., Leys D., Vascular cognitive impairment. Circ. Res. 120, 573–591 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gould D. B., et al. , Mutations in Col4a1 cause perinatal cerebral hemorrhage and porencephaly. Science 308, 1167–1171 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gould D. B., et al. , Role of COL4A1 in small-vessel disease and hemorrhagic stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 354, 1489–1496 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeanne M., Jorgensen J., Gould D. B., Molecular and genetic analyses of collagen type IV mutant mouse models of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage identify mechanisms for stroke prevention. Circulation 131, 1555–1565 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Labelle-Dumais C., et al. , COL4A1 mutations cause neuromuscular disease with tissue-specific mechanistic heterogeneity. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 104, 847–860 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khoshnoodi J., Pedchenko V., Hudson B. G., Mammalian collagen IV. Microsc. Res. Tech. 71, 357–370 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shoulders M. D., Raines R. T., Collagen structure and stability. Annu Rev Biochem 78, 929–958 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zagaglia S., et al. , Neurologic phenotypes associated with COL4A1/2 mutations: Expanding the spectrum of disease. Neurology 91, e2078–e2088 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meuwissen M. E., et al. , The expanding phenotype of COL4A1 and COL4A2 mutations: Clinical data on 13 newly identified families and a review of the literature. Genet. Med. 17, 843–853 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeanne M., Gould D. B., Genotype-phenotype correlations in pathology caused by collagen type IV alpha 1 and 2 mutations. Matrix Biol. 57–58, 29–44 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuo D. S., Labelle-Dumais C., Gould D. B., COL4A1 and COL4A2 mutations and disease: Insights into pathogenic mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. Hum. Mol. Genet. 21, R97–110 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuo D. S., et al. , Allelic heterogeneity contributes to variability in ocular dysgenesis, myopathy and brain malformations caused by Col4a1 and Col4a2 mutations. Hum. Mol. Genet. 23, 1709–1722 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis M. J., Hill M. A., Signaling mechanisms underlying the vascular myogenic response. Physiol. Rev. 79, 387–423 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dabertrand F., et al. , Potassium channelopathy-like defect underlies early-stage cerebrovascular dysfunction in a genetic model of small vessel disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, E796–E805 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Earley S., Waldron B. J., Brayden J. E., Critical role for transient receptor potential channel TRPM4 in myogenic constriction of cerebral arteries. Circ. Res. 95, 922–929 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonzales A. L., Garcia Z. I., Amberg G. C., Earley S., Pharmacological inhibition of TRPM4 hyperpolarizes vascular smooth muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 299, C1195–1202 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonzales A. L., et al. , A PLCgamma1-dependent, force-sensitive signaling network in the myogenic constriction of cerebral arteries. Sci. Signal. 7, ra49 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nelson M. T., et al. , Relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by calcium sparks. Science 270, 633–637 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knot H. J., Standen N. B., Nelson M. T., Ryanodine receptors regulate arterial diameter and wall [Ca2+] in cerebral arteries of rat via Ca2+-dependent K+ channels. J. Physiol. 508, 211–221 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nilius B., et al. , The Ca2+-activated cation channel TRPM4 is regulated by phosphatidylinositol 4,5-biphosphate. EMBO J. 25, 467–478 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Z., Okawa H., Wang Y., Liman E. R., Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate rescues TRPM4 channels from desensitization. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 39185–39192 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wenceslau C. F., et al. , Guidelines for the measurement of vascular function and structure in isolated arteries and veins. Am. J. Physiol. Heart. Circ. Physiol. 321, H77–H111 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Launay P., et al. , TRPM4 is a Ca2+-activated nonselective cation channel mediating cell membrane depolarization. Cell 109, 397–407 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nilius B., et al. , Voltage dependence of the Ca2+-activated cation channel TRPM4. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 30813–30820 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arullampalam P., et al. , Species-specific effects of cation channel TRPM4 small-molecule inhibitors. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 712354 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ozhathil L. C., et al. , Identification of potent and selective small molecule inhibitors of the cation channel TRPM4. Br. J. Pharmacol. 175, 2504–2519 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gonzales A. L., Earley S., Endogenous cytosolic Ca(2+) buffering is necessary for TRPM4 activity in cerebral artery smooth muscle cells. Cell Calcium 51, 82–93 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ali S., et al. , Nitric oxide signals through IRAG to inhibit TRPM4 channels and dilate cerebral arteries. Function 2, zqab051 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dabertrand F., et al. , PIP2 corrects cerebral blood flow deficits in small vessel disease by rescuing capillary Kir2.1 activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2025998118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mughal A., Harraz O. F., Gonzales A. L., Hill-Eubanks D., Nelson M. T., PIP2 improves cerebral blood flow in a mouse model of alzheimer’s disease. Function 2, zqab010 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xie J., Li Q., Ding X., Gao Y., GSK1059615 kills head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells possibly via activating mitochondrial programmed necrosis pathway. Oncotarget 8, 50814–50823 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang L., Zhou F., ten Dijke P., Signaling interplay between transforming growth factor-beta receptor and PI3K/AKT pathways in cancer. Trends Biochem. Sci. 38, 612–620 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Inman G. J., et al. , SB-431542 is a potent and specific inhibitor of transforming growth factor-beta superfamily type I activin receptor-like kinase (ALK) receptors ALK4, ALK5, and ALK7. Mol. Pharmacol. 62, 65–74 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Earley S., Kleinfeld D., PIP2 as the "coin of the realm" for neurovascular coupling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2106308118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mao M., Labelle-Dumais C., Tufa S. F., Keene D. R., Gould D. B., Elevated TGFbeta signaling contributes to ocular anterior segment dysgenesis in Col4a1 mutant mice. Matrix Biol. 110, 151–173 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hamidi A., et al. , TGF-beta promotes PI3K-AKT signaling and prostate cancer cell migration through the TRAF6-mediated ubiquitylation of p85alpha. Sci. Signal 10, eaal4186 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hara K., et al. , Association of HTRA1 mutations and familial ischemic cerebral small-vessel disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 1729–1739 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.ten Dijke P., Arthur H. M., Extracellular control of TGFbeta signalling in vascular development and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 857–869 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ratelade J., et al. , Reducing hypermuscularization of the transitional segment between arterioles and capillaries protects against spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Circulation 141, 2078–2094 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ratelade J., et al. , Severity of arterial defects in the retina correlates with the burden of intracerebral haemorrhage in COL4A1-related stroke. J. Pathol. 244, 408–420 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Favor J., et al. , Type IV procollagen missense mutations associated with defects of the eye, vascular stability, the brain, kidney function and embryonic or postnatal viability in the mouse, Mus musculus: An extension of the Col4a1 allelic series and the identification of the first two Col4a2 mutant alleles. Genetics 175, 725–736 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wenceslau C. F., et al. , Guidelines for the measurement of vascular function and structure in isolated arteries and veins. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 321, H77–H111 (2021), 10.1152/ajpheart.01021.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gonzales A. L., Amberg G. C., Earley S., Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum is required for sustained TRPM4 activity in cerebral artery smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 299, C279–C288 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper or the SI Appendix. All supporting data have been deposited in a publicly available database (https://figshare.com/articles/figure/Yamasaki_et_al_PNAS_2022_Source_Data_Files_xlsx/21892776)