Abstract

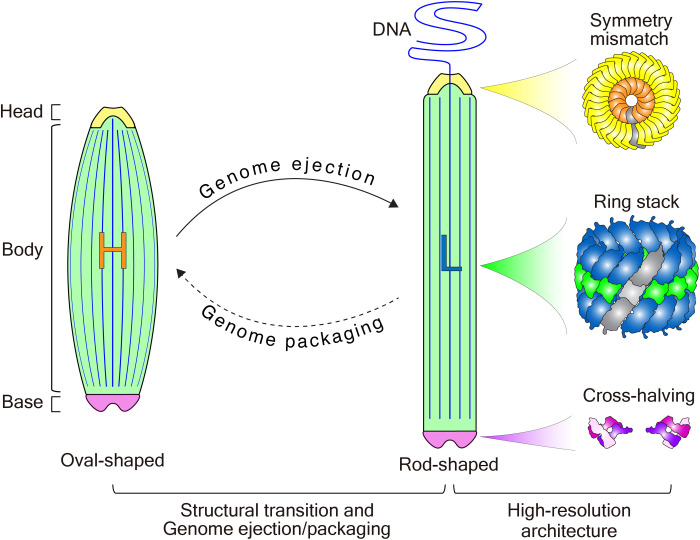

White spot syndrome virus (WSSV) is one of the largest DNA viruses and the major pathogen responsible for white spot syndrome in crustaceans. The WSSV capsid is critical for genome encapsulation and ejection and exhibits the rod-shaped and oval-shaped structures during the viral life cycle. However, the detailed architecture of the capsid and the structural transition mechanism remain unclear. Here, using cryo–electron microscopy (cryo-EM), we obtained a cryo-EM model of the rod-shaped WSSV capsid and were able to characterize its ring-stacked assembly mechanism. Furthermore, we identified an oval-shaped WSSV capsid from intact WSSV virions and analyzed the structural transition mechanism from the oval-shaped to rod-shaped capsids induced by high salinity. These transitions, which decrease internal capsid pressure, always accompany DNA release and mostly eliminate the infection of the host cells. Our results demonstrate an unusual assembly mechanism of the WSSV capsid and offer structural insights into the pressure-driven genome release.

White spot syndrome virus owns uncommon ring-stacked capsids, and the structural morphing is accompanied by viral genome release.

INTRODUCTION

White spot syndrome virus (WSSV), which is the sole species of virus in the genus Whispovirus in the family Nimaviridae, is the major pathogen responsible for white spot syndrome in a wide range of crustacean hosts, especially penaeid shrimp (1–3). WSSV, which is highly contagious and lethal, can wipe out the entire populations of many shrimp farms within 3 to 10 days (4–6). Effective treatments for WSSV are still unavailable (5, 6). WSSV causes a ~10% loss in global shrimp production (7), and the related economic loss is ~10 billion U.S. dollars per year (6, 8, 9).

WSSV is an oval-shaped, double-stranded, DNA virus (10, 11). The viral particle has been reported to be 250 to 380 nm in length and 80 to 120 nm in diameter (4). Sometimes, the WSSV virion has a tail-like appendage at one end, the function of which is still unknown (4, 12). WSSV has an outer lipid bilayer membrane envelope (13, 14). Beneath the envelope, there are two extra layers: a tegument and a capsid (9). The WSSV tegument is a cluster of proteins that line the space between the envelope and the capsid (9, 15) and aid in capsid transport and evasion of the host immune response (16, 17).

WSSV capsid proteins enwrap DNA strands into nucleocapsids for genome encapsulation (12, 18). Under negative-stain electron microscopy (EM), isolated capsids exhibit a rod-shaped architecture, with a length of 330 to 440 nm and a diameter of 58 to 80 nm (4, 19, 20). Rod-shaped capsids are also visible in host cells under thin-section EM, representing certain stages during viral life cycle (15, 21). Approximately 15 conspicuous vertical layers stack along the long axis, and each layer consists of two parallel striations (6, 19). These two striations can be divided into 14 globular capsomers, each of which is 8 nm in diameter (19). Unexpectedly, rod-shaped capsids are not directly discernable from the oval-shaped WSSV virions (21), hinting toward the structural plasticity of capsids and the structural transition during viral infection.

Similar to other DNA viruses, the cycle of viral infection of WSSV virions begins with the entry into the host cell via hijacking clathrin-mediated endocytosis and then continues through endosomes until WSSV ejects the DNA genome from its capsid into the host cell nucleus (22–25). Once in the nucleus, host transcriptional factors will bind the WSSV genome and initiate viral gene expression (1, 26). How the WSSV genome passes through the nuclear membrane remains unknown. Many families of DNA viruses, such as the herpes simplex virus (HSV) and bacteriophage λ, have highly stressed packaged genomes, which exert 10 to 20 atmospheres of pressure inside their capsids (27–30). The high internal capsid pressure is usually generated by an adenosine 5′-triphosphate–driven packaging motor, located at the portal vertex (31, 32). The reverse process of pressure-driven genome ejection is critical for viral replication, and the extent of this genome ejection will be affected by varying the external osmotic pressure (30). So far, these observations are limited to viruses with icosahedral capsids. The genome ejection mechanism for oval-shaped or spindle-shaped viruses, including WSSV, is worthy of thorough investigation.

WSSV has one of the largest genomes, at ~300 kilobases, of viruses that infect animals, containing at least 181 predicted open reading frames (4, 33). Most of these encode polypeptides with no significant homology to other known proteins (33), which makes it hard to predict their individual structures. Here, we isolated WSSV capsids to mimic various stages in host cells, resolved the architecture of rod-shaped WSSV capsids to near-atomic resolution via cryo-EM, and identified its unusual ring-stacked assembly mechanism, which is distinct from other viruses. We further analyzed the structural transition mechanism from the oval-shaped to rod-shaped WSSV capsids induced by high salinity, linked the structural transition with the genome ejection, and identified salinity treatment as a potential solution to prevent WSSV infection.

RESULTS

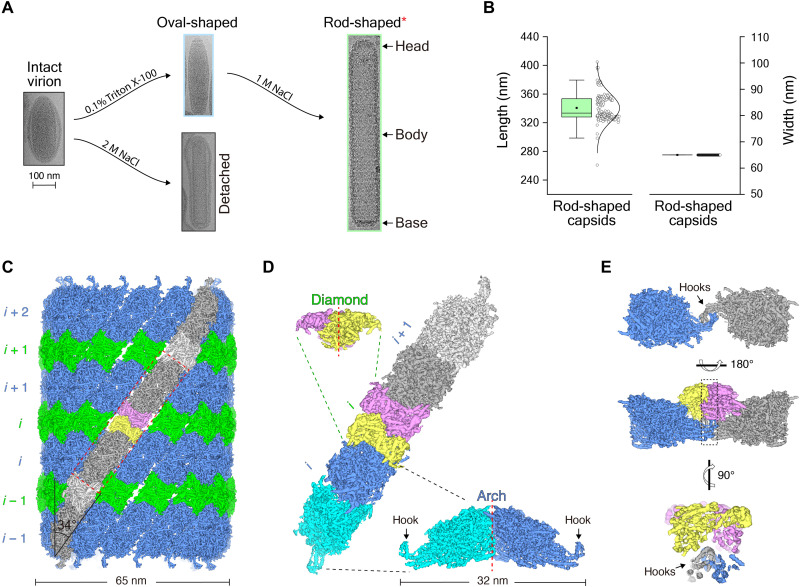

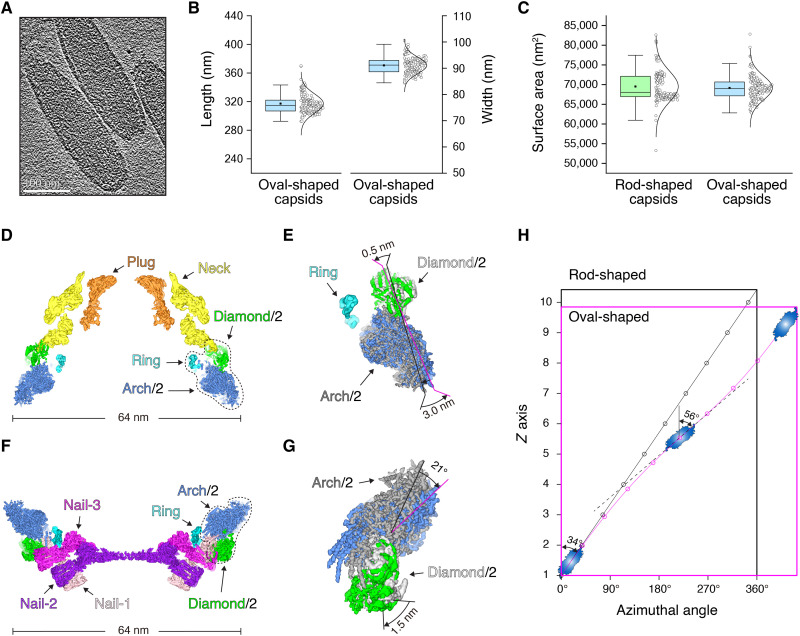

Barrel-shaped structure of the body

The WSSV virion was isolated via ultracentrifugation, and the WSSV capsid was obtained after successive treatments with detergent and high salt (Fig. 1A), as described in the literatures (15, 21, 34). Under cryo-EM, the isolated WSSV capsid assembles into a straight, rod-shaped filament with regular patterns (Fig. 1A), similar to previous negative-stain EM results (19). The rod-shaped WSSV capsid has obvious polarity and can be divided into three subregions: the base, the body, and the head (Fig. 1A). The base and the head themselves seem homogeneous in both size and shape, while the body exhibits diverse lengths. Detailed statistical analyses show that the width of the body is quite stable at ~65 nm, while the length ranges from 300 to 380 nm (Fig. 1B). The length distribution of the body exhibits a clear “ladder pattern”, with the difference at ~24 nm (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1. Barrel-shaped structure of the body and its assembly mechanism.

(A) Typical cryo-EM micrographs of the WSSV capsids after different treatments. The rod-shaped capsid is zoomed in two times the size of other structures for better labeling with the head, the body, and the base. (B) The length and width statistics of the rod-shaped WSSV capsids. (C) Barrel-like structure of the body. The thick and thin layers are colored in blue and green, respectively. The same color scheme is used throughout the study unless specified. Arch-like and diamond-like structures in one protofilament are colored in dark gray and light gray, respectively. One diamond-like structure is divided into two parts (in purple and yellow) based on the symmetry. (D) Structural analyses on the arch-like and diamond-like structures. Twofold symmetry axis is labeled as red dashed lines. (E) Intertwined hooks lock neighboring arch-like structures together.

Length variability of the body makes it difficult to directly resolve the rod-shaped WSSV capsid as a whole. So, a divide and conquer strategy was adopted to separately reconstruct the base, the body, and the head and then to rejoin these structures into an integral architecture (fig. S1 and table S1). Of the three rod-shaped capsid components, the body, which occupies ~87% of the total length, was first to undergo three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction, with great potential for high resolution.

A 75% overlap between adjacent boxes was adopted during particle picking on the body, and 46,915 particles were lastly selected after the removal of obvious junks. 2D classification showed a regular pattern with layered striations (figs. S1 and S2A), which is similar to the previous report (19). As suggested in the literature, a 14-fold symmetry was enforced during the 3D refinement, and the reconstruction converged to a resolution of 4.6 Å, based on the gold-standard Fourier shell correlation (FSC) (fig. S3A). Because of the structural heterogeneity within the body, a focal refinement was applied onto the asymmetric unit, and this further improved the final resolution to 3.3 Å (figs. S1, S2B, and S3B). This well-resolved density map was carefully segmented into an arch-like structure and a diamond-like structure, and these two structural components were duplicated to build a high-resolution architecture of the body (Fig. 1, C and D, and figs. S1 and S2B).

The body of rod-shaped WSSV capsids exhibits a barrel-like structure and consists of two kinds of parallel rings: a thick (~24 nm) ring and a thin ring (~13 nm) (fig. S2C). The thick ring consists of 14 arch-like structures, and each of these has a tilting angle of ~34° against the long axis. The arch-like structure occurs as a dimer and is huge in size with the length of ~32 nm and the height of ~12 nm (Fig. 1D). Neighboring arch-like structures are tightly packed into the thick ring, with no obvious seam between. Instead, neighboring thick rings have an obvious gap, and the gap is perfectly filled with a thin ring (Fig. 1C and fig. S2C). The thin ring is composed of 14 diamond-like structures (Fig. 1C and fig. S2C). The diamond-like structure also has a two-fold symmetry, which joins the upper and lower thick rings. Apparently, the body adopts an unusual ring-stacked assembly mode.

The body of the rod-shaped WSSV capsid can also be deemed as a helix with 14 protofilaments. Unfortunately, a single helical symmetry cannot be indexed directly from the power spectra (fig. S2A), because of a possible huge helical rise or multiple helical symmetries. Thus, a global helical symmetry is not applied onto the body of the rod-shaped WSSV. On the basis of the above reconstruction with the 14-fold symmetry, an arch-like structure and a diamond-like structure appear alternately along each protofilament (Fig. 1C). Neighboring arch-like structures have a small contact region along the protofilament. Specifically, each arch-like structure has two elongated hook-like tails on both far ends (Fig. 1D and fig. S2C). Neighboring arch-like structures on the same protofilament use these hooks to tightly lock them together. The dimeric diamond-like structure lies exactly over the intertwined hooks and uses its deep cleft between the two subunits to clamp these hooks (Fig. 1E). This organization effectively prevents the detachment of neighboring arch-like structures on the same protofilament and provides structural connectivity to the body.

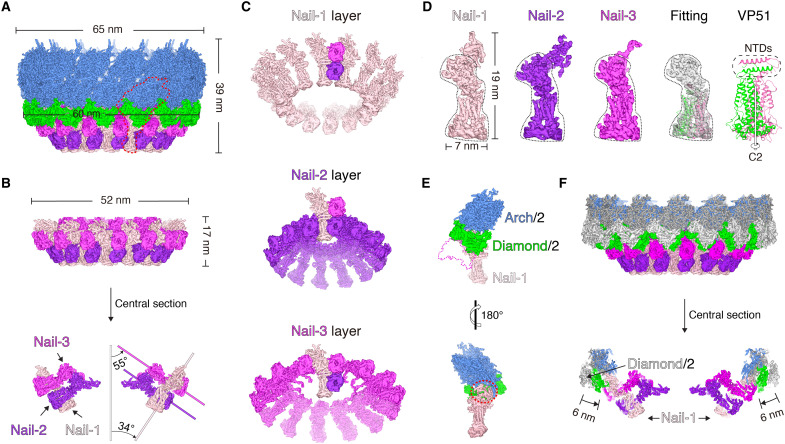

Disc-shaped structure of the base

To reconstruct the base of the rod-shaped WSSV capsids, targeted regions were manually picked up using the base as the center. The same 14-fold symmetry as the body was enforced on the base, and the reconstruction converged at a resolution of 4.8 Å (figs. S1 and S3C and table S1). A focal refinement was also performed on three asymmetric units due to the structural variation (movie S1), and this further pushed the resolution to 3.7 Å (figs. S1 and S3D). Subtracting the overlapping densities with the body, the base was found to have a disc-shaped structure with a diameter of ~52 nm and a height of ~17 nm (Fig. 2, A and B, and fig. S4A). In each asymmetric unit, there were three oval shapes on the surface of the base, which were similar to each other (fig. S4A). After intensive density segmentation, these three oval shapes were found to belong to three nail-like structures (depicted as Nail-1, Nail-2, and Nail-3, respectively), which, together, occupied almost all the EM densities in the asymmetric unit (Fig. 2, A and B, and fig. S4B).

Fig. 2. Disc-shaped structure of the base and its assembly mechanism.

(A) Cryo-EM model of the base and part of the body. One typical region is circled in red for further structural analysis in (E). (B) Cryo-EM model of the disc-shaped base and its cross-halving joint structure formed by Nail-1, Nail-2, and Nail-3. (C) Layers of Nail-1, Nail-2, and Nail-3. One cross-halving joint structure is displayed in each layer. (D) Structural comparison of Nail-1, Nail-2, and Nail-3 and the fitted VP51 model. (E) Nail-1 directly contacts the arch-like structure of the body, covered by a Diamond/2. Diamond/2 is the half of the diamond-like structure. (F) Structural change of the Diamond/2 in the base relative to the body. The arch-like and diamond-like structures from the body are colored in dark gray and light gray, respectively.

Neighboring Nail-1, Nail-2, and Nail-3 assemble into a “cross-halving joint structure.” Nail-3 lies over Nail-2, while Nail-1 perpendicularly appends to the above two structures (Fig. 2B). These cross-halving joint structures are repeated 14 times around the base, and the 42 nail-like structures assemble into a giant self-locking apparatus (Fig. 2C). Each nail-like structure has two regions. The region with the oval shape on the outer surface is resolved with a twofold symmetry, which is nearly identical in all three nail-like structures (Fig. 2D). Mass spectrum analysis of the rod-shaped capsids indicated the presence of six major capsid proteins, including VP664, VP190, VP136, VP76, VP60, and VP51 (fig. S5A). All were structurally predicted as a whole via AlphaFold-2, except that VP664 were segmented into the overlapping fragments owing to its large size (667 kDa) (figs. S5B and S6). Two VP51 molecules fit well into part of the nail-like structures in overall shape and orientations of most α helices. After flexible fitting and refinement, atomic models for two VP51 molecules in one nail-like structure were successfully built (Fig. 2D, fig. S5C, and table S2). Unexpectedly, these two VP51 molecules were not identical, with the difference arising from the orientation of their N-terminal domains (NTDs). These two NTDs stack onto each other, orthogonal to the twofold axis of symmetry (Fig. 2D). Such a packing mode of NTDs breaks the twofold symmetry but tightly holds the two VP51 molecules together.

The other part of the nail-like structure is structurally different. Nail-2 has a quite large density, and 14 Nail-2 densities weave a basket-like structure with close contact at the center of the base (Fig. 2, C and D). Nail-3 has a small density as a rope. This structure packs tightly onto Nail-2 and might play a role in locking Nail-2 (Fig. 2, C and D). Compared with Nail-2 and Nail-3, Nail-1 is relatively straight (Fig. 2, C and D). The tip of Nail-1 extends to the body as the sole contact region between the base and the body.

During the reconstruction of the base, one layer of arch-like structures was also resolved at a local resolution of ~6.0 Å (Fig. 2A). Hooks from the arch-like structures directly contact Nail-1 at the base. Specifically, the tip part of Nail-1 exactly fits into the hook to lock or stabilize the arch-like structure, as the intertwined hooks in the body (Fig. 2E). Over the joint region between Nail-1 and the arch-like structure, there is an extra density in the cryo-EM map. This density is exactly half of the diamond-like structure (depicted as Diamond/2) (Fig. 2, E and F, and fig. S4, C and D). Compared with the diamond-like structure of the body, each Diamond/2 is shifted ~6 nm toward the center, which renders the ring of Diamond/2 a smaller diameter at ~60 nm (Fig. 2, A and F, and fig. S4, C and D). Presumably, the base uses their Nail-1 structures to initiate the assembly of the body.

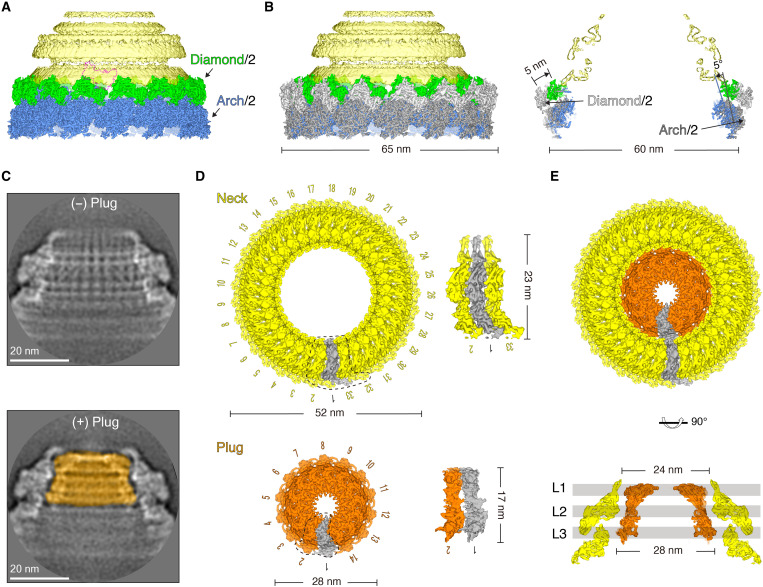

Rotor-like structure of the head

Similar to the base, the head of rod-shaped WSSV capsids was manually picked up for accurate centering and was tentatively reconstructed with the enforced 14-fold symmetry. Unexpectedly, only regions belonging to the body were resolved to a reasonable resolution of 9.2 Å (Fig. 3A; figs. S1 and S7, A and B; and table S1). As with the joint region between the base and the body, 14 Diamond/2 form a ring, which covers the arch-like structures of the body. Compared with the diamond-shaped structure in the body, each Diamond/2 shifts ~5 nm toward the center, assembling into a smaller ring with a diameter of ~60 nm (Fig. 3B). There is also clear structural change on the arch-like layers adjacent to the Diamond/2 layer, each of which rotates ~5° toward the center (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3. Rotor-shaped structure of the head and its assembly mechanism.

(A) Cryo-EM model of the head with the enforced 14-fold symmetry. Only Diamond/2 and arch-like layers are resolved with the desired structural features. The head region is colored in yellow. (B) Structural change of Diamond/2 in the head relative to the body. The arch-like and diamond-like structures from the body are colored in dark gray and light gray, respectively. (C) Two typical classes of the head. One has a plug, while the other is plug-free. (D) Cryo-EM models of the neck and the plug. The neck and the plug are colored in yellow and orange, respectively. Neighboring protomers in the neck and the plug are zoomed in and shown. (E) A composite cryo-EM model of the head with its central section.

From the smeared 3D map, the head is shown to have two layers (Fig. 3A); the outer and inner layers are depicted as the neck and the plug, respectively. The failure of the direct reconstruction of the head with the enforced 14-fold symmetry suggests that the neck and the plug might have distinct symmetries. Deep 2D classification of the head indicates two typical classes: ~69% particles belong to the class with both a neck and a plug, and ~31% particles only have a neck (Fig. 3C). The neck-only class shows a clear pattern with the number of threads occurring at the multiples of three. Thus, different symmetries in multiples of three were tried during 3D reconstructions. After the enforcement of 33-fold symmetry, the final reconstruction successfully converged to an EM map with a final resolution of 6.5 Å (Fig. 3D and figs. S1 and S3E). Unexpectedly, the application of the 14- or 33-fold symmetry on particles with both the neck and the plug failed to obtain any reasonable reconstruction on the plug. When the neck was masked out from these particles, the plug was lastly resolved at a resolution of 4.2 Å with an enforced 14-fold symmetry (Fig. 3D and figs. S1 and S3F).

Detailed structural analysis showed that each protomer of the neck has a quite flat structure with two separate domains (Fig. 3D). The plug protomer is also quite flat with elongated densities. The gate of the neck has a minimum diameter of ~24 nm, and the plug has a maximum width of ~28 nm (Fig. 3E and fig. S7C). This organization effectively prevents the detachment of the plug from the neck. The neck lies between the plug and the body and has a different symmetry (33-fold) from the plug and the body (14-fold). The symmetry numbers at 33 and 14 are coprime to each other, which renders a smooth rotation between the body and the neck and between the neck and the plug. This characteristic may be helpful for genome packaging or ejection.

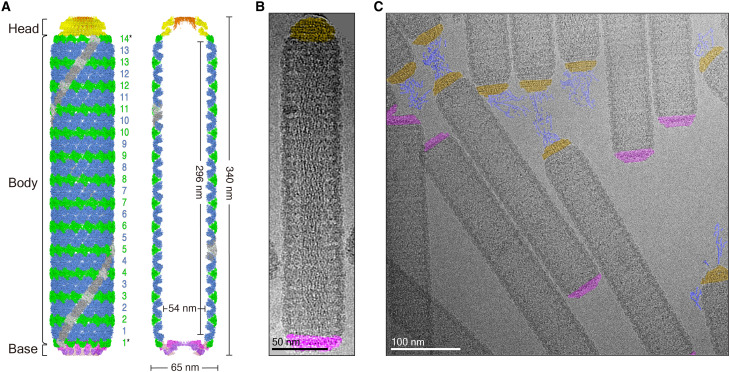

Capsid architecture and genome packaging

On the basis of the high-resolution cryo-EM models of the base, the body, and the head, the whole architecture of WSSV capsids can be composed. For a typical WSSV capsid with the average length of 340 nm, the body will consist of 13 layers of the arch-like structures separated by 12 layers of the diamond-like structures and 2 layers of the Diamond/2 structures, which connect the base and the head, respectively (Fig. 4A). In total, there are 42 nail-like structures, 182 arch-like structures, 168 diamond-like structures, 28 Diamond/2 structures, 33 neck protomers, and 14 plug protomers (Fig. 4A). All these structural components are precisely designed and well organized in the whole WSSV capsid.

Fig. 4. The architecture of the rod-shaped WSSV capsid and the genome packaging.

(A) A composite cryo-EM model of the rod-shaped WSSV capsid and its central section. The number of layers was determined by the average length of the capsid. Layer numbers in the body are labeled. Diamond/2 layers are labeled with extra stars. (B) A typical rod-shaped capsid with clear genome packaging inside. The base and the head are colored in purple and yellow, respectively. (C) A typical cryo-EM micrograph of the rod-shaped WSSV capsids with the released DNA genomes. The released DNA is colored in blue.

Representative filamentous or bullet-shaped viruses such as tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) and vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) usually have helical capsids, and their genomes follow the helical trajectory for encapsulation (35–38). Compared with TMV and VSV, the rod-shaped WSSV has a ring-stacked capsid. This unusual feature may suggest a different genome packaging mode for the WSSV capsid. Inside the WSSV capsid, there is a cylindrical cavity with a length of ~296 nm and a width of ~54 nm (Fig. 4A), which holds the DNA genome. A cluster of DNA filaments were recognized inside the rod-shaped capsid, directly from the raw cryo-EM micrographs, and the directions of all these filaments were parallel to the long axis of the rod-shaped capsid (Fig. 4B and movie S2). These ring-stacked capsids of the WSSV enlarge our understanding of the architecture of viral capsids and the genome packaging modes.

In addition to their presence in the inner cavity of the rod-shaped WSSV capsid, DNA filaments were also discernable in the vicinity of the head but not observed around the base or the body (Fig. 4C), which agrees well with the fibrilla component (probably a complex of DNA and proteins) around the head of the rod-shaped capsids under thin-section EM on the WSSV-infected cells (15). All these suggest that the rod-shaped WSSV capsid may represent a genome ejection state with the head being the gateway. This observation reiterates the need to further explore the relationship between WSSV capsids and the genome ejection.

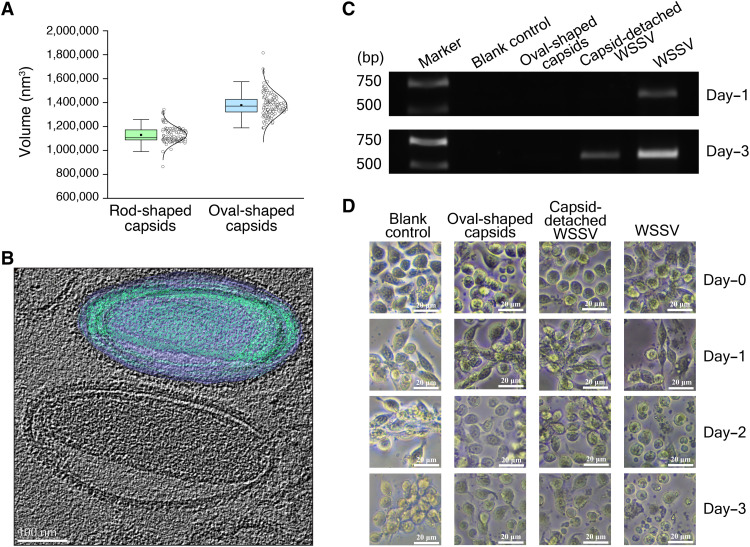

Structural transition of WSSV capsids

Rod-shaped WSSV capsids are ideal for high-resolution cryo-EM analysis. Without extra high salt treatment, mild detergent alone solubilizes the membrane yielding an oval-shaped structure (Figs. 1A and 5A). As with the rod-shaped WSSV capsid, major capsid proteins such as VP664 and VP190 can be identified from the mass spectrum (fig. S5A). Compared with the rod-shaped capsid, the oval-shaped WSSV capsid has a bulging body with an average long axis decreasing to ~317 nm and an average short axis increasing to ~92 nm (Fig. 5B and movie S3). The oval-shaped capsid has the same surface area as the rod-shaped capsid (Fig. 5C), which indicates the same amount of capsid proteins. Structural transition between oval-shaped and rod-shaped capsids will be directly caused by structural rearrangements of the arch-like and diamond-like structures.

Fig. 5. Structural transition between the rod-shaped and oval-shaped WSSV capsids.

(A) The oval-shaped WSSV capsid revealed by cryo–electron tomography (cryo-ET). (B) The length and width statistics of the oval-shaped WSSV capsids. (C) The surface area statistics of the rod-shaped and oval-shaped WSSV capsids. (D) The central section of the head of the oval-shaped capsid. (E) Structural change of Diamond/2 and Arch/2 in the oval-shaped capsid relative to the rod-shaped capsid. The arch-like and diamond-like structures from the body are colored in dark gray and light gray, respectively. (F) The central section of the base of the oval-shaped capsid. (G) Structural change of Diamond/2 and Arch/2 in the oval-shaped capsid relative to the rod-shaped capsid. The arch-like and diamond-like structures from the rod-shaped capsid are colored in dark gray and light gray, respectively. (H) Modeling of the structural rearrangement of arch-like structures along the Z axis (long axis of rod-shaped and oval-shaped capsids).

To precisely compare the oval-shaped WSSV capsid with the rod-shaped capsid, the base, the body, and the head of the oval-shaped capsid were reconstructed separately (fig. S8). As expected, the body exhibited diverse conformations with varying widths, which makes the body smear in the 2D classification. Fortunately, both the base and the head are well classified with adequate structural features. The head and the base of the oval-shaped capsids were separately reconstructed, and their respective conformational change against the counterparts in the rod-shaped capsids was investigated (fig. S8).

The head of the oval-shaped WSSV capsid was directly reconstructed with the enforced 14-fold symmetry to focus on the arch-like and Diamond/2 layers. These two layers were determined at a resolution of ~8.0 Å, sufficient for accurate structural comparison (Fig. 5D and figs. S8, S9A, and S10, A and B). From the rod-shaped to oval-shaped capsids, the arch-like structures were shifted ~3 nm outward (Fig. 5E). As the control, the Diamond/2 layer takes a very similar orientation between the rod-shaped and oval-shaped capsids (Fig. 5E). This structural rearrangement causes the upcoming arch-like layers to have increasingly larger diameters.

The base of the oval-shaped WSSV capsids is resolved at a resolution of 5.9 Å (Fig. 5F and figs. S8, S9B, and S10, C and D) and is identical in structure to the base of rod-shaped capsids, indicating that the base is quite fixed during structural transition. Besides the base, one arch-like layer and one Diamond/2 layer in the oval-shaped capsids are also resolved clearly. Structural comparison indicates that the Diamond/2 layers take a very similar orientation, while the arch-like structures rotate ~21° outward from the rod-shaped to oval-shaped capsids (Fig. 5G). Again, this structural arrangement markedly enlarges the following arch-like layers in the body of the oval-shaped capsids.

Apparently, from either the base or the head to the center of the body, the arch-like layers have greater diameters in the oval-shaped WSSV capsids. Furthermore, each arch-like structure takes conformations with increasing tilting angles to the long axis. Modeling shows that the tilting angle of arch-like structures in the central layer of the body reaches up to ~56° along the long axis in the oval-shaped capsids. As the control, the arch-like structures in the rod-shaped capsids have a fixed titling angle at ~34° (Fig. 5H). These gradual changes in the tilting angle of the arch-like structures from the different layers contribute to their structural transition from the rod-shaped to the oval-shaped capsids.

Pressure-driven genome ejection

Unlike the similar surface area, which remains constant, the average volume of the oval-shaped WSSV capsids at 1,380,000 nm3 is ~26% greater than that of the rod-shaped capsids at 1,100,000 nm3; the former has a greater capacity to hold additional DNA filaments (Fig. 6A). Accordingly, only a few oval-shaped capsids release filaments from the head under cryo-EM, and more DNA is stored in the oval-shaped capsids. In the oval-shaped capsid, the head and the base each has a ring, which has not been resolved in the rod-shaped WSSV capsid. Both rings have 14-fold symmetries and are identical in structure (fig. S11). These two rings have opposite orientations in the oval-shaped capsids and expose their same sides to the inner cavity. Thus, the rings might get involved in clamping the DNA inside the oval-shaped capsids, and the detailed function still needs further investigation.

Fig. 6. Structural transition is highly relevant to WSSV infection.

(A) The volume statistics of the rod-shaped and oval-shaped WSSV capsids. (B) Cryo-ET of the intact WSSV virion with the oval-shaped capsids. (C) The replication comparison of the WSSV VP28 gene in the primarily cultured shrimp cells after different treatments at different time points. (D) The damage comparison of WSSV to shrimp cells after different treatments at different time points.

Cryo–electron tomography (cryo-ET) analysis of intact WSSV virions has also identified an oval-shaped capsid beneath the envelope, with similar sizes to the oval-shaped capsids after detergent treatment (Fig. 6B). Compared with the rod-shaped capsids, the bulging of the oval-shaped capsids may be driven by pressure in the packaged genomes inside the virion, as in Sulfolobus monocaudavirus 1, HSV-1, and bacteriophage λ (27–30, 39). Osmotic stress such as high salt concentrations can alter genome packaging and then release intrinsic pressure (29), and direct high salt treatment on the intact virion was found to detach the capsid from the envelope (depicted as the capsid-detached WSSV virion) and turn the oval-shaped capsids into the rod-shaped capsids (Fig. 1A). This structural transition in WSSV is unique and does not occur in HSV-1 and bacteriophage λ probably due to the structural rigidity of their icosahedral capsids.

After the high salt levels were removed, the structural transition of the WSSV capsids was found to be irreversible, and the WSSV capsid still had a rod-shaped structure inside the envelope (Fig. 1A). This suggests us that the capsid-detached WSSV virion might lose pressure to push the genome into the nucleus, and this would impair the genome replication and possible infection of WSSV in shrimp cells. To verify these speculations, capsid-detached WSSV virions were incubated with the primarily cultured shrimp cells, and the replication level of the WSSV VP28 gene was monitored at different days. Compared with the wild-type WSSV, the replication level of VP28 was much lower in the capsid-detached WSSV (Fig. 6C). Consistent with this, the capsid-detached WSSV had less effect on the shrimp cells. After 3 days, the lysed cells were marked reduced in number compared with the wild-type WSSV (Fig. 6D). This supports the pressure-driven ejection mechanism of viral genomes into host cells and links the genome ejection with the structural transition of WSSV capsids.

DISCUSSION

WSSV is a major shrimp pathogen, readily transmissible to other crustaceans, but its capsid architecture and infection mechanism remain unclear (1, 2, 40). Here, we used cryo-EM to resolve the base, the body, and the head of the rod-shaped WSSV capsid to near-atomic resolutions. The body with the resolution at 3.3 Å allows us to perform protein identification via DeepTracer (41, 42). On the basis of the local resolution map, we picked up seven best resolved fragments from Arch/2 and blasted the predicted sequences of these fragments against 177 annotated WSSV proteins, and the only blast hit for all these fragments was VP664 (fig. S12). A continuous cryo-EM density derived from one fragment (residues from 2657 to 2826) further extends to Diamond/2, indicating that Arch/2 and Diamond/2 may belong to one VP664 molecule (fig. S13). The good superimposition between structures of these fragments and the predicted counterparts via AlphaFold-2 further validated this (figs. S12 and S13). Thus, VP664 spans both Arch/2 and Diamond/2 as the major component to assemble into the body of WSSV capsids. The atomic model of VP664 will help clarify the assembly mechanism of the body and the structural transition between the rod-shaped and oval-shaped capsids at the molecular level.

Besides VP664, previous and our own mass spectrum and immune-gold labeling results indicate that the WSSV capsid consist of at least five other different proteins including VP190, VP136, VP76, VP60, and VP51 (14, 15, 43, 44). So far, we could only assign the AlphaFold-2–predicted VP51 model to the part of nail-like structures (Fig. 2D and fig. S5C) but failed on other proteins. One possible reason for this is the low sequence similarity between WSSV capsid proteins and structurally resolved proteins. Another possible reason is that proteins assembled in the WSSV capsid might take different conformations from their individual structures. Although atomic models for most capsid proteins are unavailable, the assembly mechanism of WSSV capsids can still be clearly clarified.

Both rod-shaped and oval-shaped WSSV capsids are composed of stacked rings, which are distinct from the helical assemblies of many filamentous or spindle-shaped viruses (35–37, 39, 45). The base, the body, and the head have their own peculiar structural features. For instance, the base of the WSSV capsid adopts a cross-halving joint structure, the body evolves hook-like structures to connect neighboring arch-like layers, and the head has a plug and a neck with distinct symmetries (Fig. 7). From the oval-shaped to rod-shaped capsids, only the body takes a significant conformational change with the reduced length and the bulged width. Hook-like structures between neighboring rungs are supposed to offer this structural plasticity.

Fig. 7. Model illustrating the architecture of the WSSV capsid and the pressure-driven genome ejection.

“H” and “L” stand for the high- and low- capsid pressures, respectively.

In both the rod-shaped and oval-shaped WSSV capsids, the base, the body, and the plug have 14-fold symmetries, except for the neck that has a 33-fold symmetry. A similar symmetry mismatch also occurs in other apparatuses such as flagella motor proteins and the Epstein-Barr virus portal (46–48). Symmetry numbers in these well-known molecular apparatuses are always prime to each other. The coprime character renders a reduced friction between rings and can be extended to apparatuses requiring smooth rotations to fulfil their functions, which will benefit protein design and engineering.

Genome ejection of DNA viruses into a host cell nucleus is usually pressure-driven (27–30). Intact WSSV virion has an oval-shaped capsid, and high salinity induces the structural transition of the oval-shaped capsid to a rod-shaped capsid, accompanied by DNA release from the head. Relative to the oval-shaped capsid, the rod-shaped WSSV capsid has the same surface area but a significantly reduced volume. These characteristics link the structural transition of WSSV capsids with the genome packaging/ejection (Fig. 7). Our work expands the pressure-driven genome packaging/ejection model to oval-shaped viruses and suggests high-salinity treatment as a potential solution to fight against WSSV and similar viruses via impairing genome ejection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of the WSSV capsids

WSSV-infected gill tissues (1 g) from penaeid shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) were homogenized in 20 ml of TN buffer [20 mM tris-HCl and 400 mM NaCl (pH 7.5)]. After centrifugation at 3000g for 5 min, the supernatant was collected and further filtered by 0.45-μm filter. A 0.1-ml sample of supernatant was injected intramuscularly into healthy crayfish (Procambarus clarkii, 7 to 10 cm in length and 20 to 30 g in weight) between the third and fourth abdominal segments. After 4 to 7 days, dead and moribund crayfish were collected and kept at 4°C for virus isolation.

The tissues of 10 infected crayfish except for hepatopancreas were homogenized on ice for 5 min using a mechanical homogenizer (SCIENTZ, China) in 1 liter of TNE buffer [50 mM tris-HCl, 500 mM NaCl, and 5 mM EDTA (pH 8.0)] containing protease inhibitors (1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM benzamidine, and 1 mM Na2S2O5) (34). After centrifugation at 3500g for 5 min at 4°C, the supernatant was collected and then subjected to ultracentrifugation at 30,000g for 30 min at 4°C (Beckman Optima XPN-100, USA). The supernatant was discarded, and the upper loose layer of the pellet was rinsed out carefully. The lower solid layer containing viral particles was resuspended in 50 ml of TNE buffer. The resuspension was subjected to another round of successive centrifugation steps at 3500g for 5 min and at 30,000g for 20 min at 4°C. The lower solid layer was resuspended in 1 ml of TM buffer [50 mM tris-HCl and 5 mM MgCl2 (pH 7.5)]. The final resuspension was centrifuged three to five times at 650g for 5 min to remove pink impurities. The milk-like fraction containing intact WSSV virions was stored at 4°C, and fresh samples were subjected to the following treatments.

Purified intact WSSV virions were mixed with an equal volume of 0.2% Triton X-100 in TM buffer and incubated at room temperature for 30 min to obtain oval-shaped WSSV capsids. The sediments were collected after centrifugation at 20,000g for 20 min at 4°C and resuspended in TM buffer. The treatment was repeated once to ensure that envelopes were removed completely. To obtain rod-shaped WSSV capsids, the Triton X-100–treated WSSV capsids were further mixed with an equal volume of 2 M NaCl in TM buffer and incubated at 4°C for 30 min. The sediments were collected after centrifugation at 20,000g for 20 min at 4°C and resuspended in TM buffer. Both rod-shaped and oval-shaped WSSV capsids were immediately subjected to high-resolution cryo-EM analysis.

In addition, the purified intact WSSV virions were directly treated with 2 M NaCl in TM buffer at 4°C for 30 min. The sediments were collected and suspended in TM buffer after centrifugation at 20,000g for 20 min at 4°C. The virions were still envelope-encapsulated, and we named them the capsid-detached WSSV virions. The capsid-detached WSSV virions were collected for the further infection assays.

Cryo-EM sample preparation

Rod-shaped and oval-shaped capsids and capsid-detached WSSV virions followed the same cryo-EM sample preparation procedure. Specifically, 4 μl of sample was applied onto a freshly glow-discharged holey carbon grid (Quantifoil Au R2/1, 200 mesh) with a thin layer of continuous carbon film. The grid was blotted for 2 s in 100% humidity at 8°C and plunged into liquid ethane with Mark IV Vitrobot (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Cryo-EM grids were screened on a Glacios microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) operated at 200 kV with a Ceta 16M camera.

Cryo-EM data collection

Movies were collected using a 300-kV Titan Krios G3i microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) equipped with a K3 BioQuantum direct electron detector (Gatan, USA). Cryo-EM micrographs were automatically recorded via FEI EPU software (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) with the energy filter slit set to 20 eV (49). Each micrograph was collected at a total dose of 50 e−/Å2 fractionated into 40 frames, and the defocus was set in the range from −1.0 to −1.8 μm. A super-resolution mode was used at a nominal magnification of ×64,000 with a pixel size of 0.67 Å.

Before image processing, raw frames were aligned and summed with dose weighting under MotionCor2.1 with the final pixel size of 1.34 Å (50), and the Contrast Transfer Function parameters were determined by CTFFIND-4 (51). Image processing was mainly performed in RELION 3.1 (52) and cryoSPARC 3.1.0 (53).

Data processing on the rod-shaped WSSV capsids

A rod-shaped WSSV capsid is filamentous in shape and can be divided into three parts: a base, a body, and a head. A “divide and conquer” strategy was adopted to separately reconstruct the base, the body, and the head of the WSSV capsid and then compose these structures into an integral architecture.

3D reconstruction of the body

In each filament, start and end points of the body were manually specified, and particles were extracted with 75% overlap. Obvious junks were removed on the basis of the 2D classification. On the basis the literature (19), 14-fold symmetry was tentatively applied during the reconstruction. Total 46,915 particles were 3D classified into three classes with the enforced 14-fold symmetry and a cylinder as the initial model. One class with 17,715 particles was selected and subjected to 3D autorefinement with the 14-fold symmetry, and the reconstruction was estimated at the resolution of 4.6 Å based on the gold-standard FSC of 0.143.

To further improve resolution, local refinement was applied on the asymmetric unit. Specifically, the 14-fold symmetry was released from the determined Euler angles, and the dataset was expanded and passed to cryoSPARC. In cryoSPARC, local refinement was performed with a mask on the asymmetric unit, and the final reconstruction was estimated at the resolution of 3.3 Å based on the gold-standard FSC 0.143.

3D reconstruction of the base

The center of the base in each filament was manually specified, and one particle was extracted from each filament. The built-up particle set was subjected to 2D classification to remove obvious junks, and total 16,509 particles were selected. A direct 3D refinement was performed in RELION with the enforced 14-fold symmetry and the initial model for the refinement was synthesized with part of the low-pass–filtered body and two rings. The reconstruction of the base was converged at the resolution of 4.8 Å based on the gold-standard FSC of 0.143. The same local refinement strategy as the body was applied onto the base with three asymmetric units covered in the mask, and the final resolution was pushed to 3.7 Å.

3D reconstruction of the head

The reconstruction strategy on the head was similar to the base. Specifically, the center of the head in each filament was also manually specified, and a particle set containing 5827 particles was built up after 2D classification. An initial model was composed with part of the low-pass–filtered body and three layers of rings. A direct 3D refinement with the enforced 14-fold symmetry yielded a reconstruction at the resolution of 9.2 Å. The body has detailed structural features, while the head is blurred. The head has two layers, and the inner and outer layers are named as the plug and the neck, respectively.

To focus on the head, 5827 particles were reextracted using a smaller box, which tightly covers the head region. 2D classification indicated two typical classes: One only has the neck, while the other has both the plug and the neck. The neck-only class consists of 988 particles, and an exhaust search from 9- to 33-fold symmetry, at the multiple of three, was attempted to verify the ideal 33-fold symmetry. 3D refinement with the enforced 33-fold symmetry yielded a reconstruction of the neck at the resolution of 6.5 Å. The class with both the plug and the neck contains 2157 particles, and the direct reconstructions with the enforced 14-fold or 33-fold symmetry failed to yield any reasonable density map. These particles were reboxed with an even smaller box and were reconstructed in cryoSPARC with the 14-fold symmetry and a tight mask. The final resolution reached 4.2 Å based on the gold-standard FSC 0.143.

Data processing on the oval-shaped WSSV capsids

Similar to the rod-shaped capsid, the oval-shaped WSSV capsid can also be divided into three parts: the base, the body, and the head; and each part was separately reconstructed in RELION and cryoSPARC. A total of 2126 micrographs with integral oval-shaped WSSV capsids were selected after motion correction. In each capsid, start and end points of the body were manually specified, and particles were extracted with 75% overlap. Particles (17,569) were extracted and performed three rounds of 2D classification. Ideal classes with structural features only appear on the far ends of the body.

The base of oval-shaped WSSV capsids was manually picked up, and 1774 particles were extracted in RELION. A total of 1683 particles were further screened out after 2D classification. A direct 3D refinement was performed with the enforced 14-fold symmetry in cryoSPARC, and the base of the rod-shaped WSSV capsid was low-pass–filtered to 40 Å as the initial model. The reconstruction was estimated at the resolution of 5.9 Å based on the gold-standard FSC 0.143.

The head of oval-shaped WSSV capsids was also manually picked up, and 981 particles were extracted in RELION. A total of 808 particles were screened out after 2D classification. A direct 3D refinement was performed with the enforced 14-fold symmetry in cryoSPARC, and the head of the rod-shaped WSSV capsid was low-pass–filtered to 40 Å as the initial model. The reconstruction was estimated at the resolution of 9.5 Å based on the gold-standard FSC of 0.143. The body part in the head of oval-shaped WSSV capsids was well resolved with detailed structural features. The focal refinement was performed on the body part and yielded the final reconstruction at the 8.0-Å resolution.

Structural analyses and cryo-EM model building

Local-refined cryo-EM maps including the body, the base, and the head from either rod-shaped or oval-shaped WSSV capsids were intensively segmented via Segger in UCSF Chimera 1.16 (54). Specifically, asymmetric unit in each map was firstly recognized and segmented, and then the asymmetric unit was further divided into subregions based on the density connectivity and their own symmetries. Five high-resolution individuals including arch-like structure, diamond-like structure, nail-like structure, neck protomer, and plug protomer have been segmented from the rod-shaped WSSV capsid, and one ring protomer is solely resolved in the oval-shaped WSSV capsid.

Using these high-resolution individuals as the blocks, the high-resolution models of the body, the base, or the head were built in UCSF Chimera. According to the average length of rod-shaped WSSV capsids, the composite model of the whole WSSV capsid was manually built via UCSF Chimera. Other structural analyses, such as structural superimposition, were also fulfilled with UCSF Chimera.

Surface area and volume analyses

A total of 154 integral rod-shaped or oval-shaped WSSV capsids were randomly selected from raw cryo-EM micrographs, and their length (long axis for the oval-shaped capsids) and width (short axis for the oval-shaped capsids) were manually measured in EMAN2.12 (55).

Both the surface areas and 3D volumes for the rod-shaped and oval-shaped WSSV capsids were calculated on the basis of their respective average length and width as shown in Figs. 1B and 5B. Specifically, the rod-shaped capsid was treated as a cylinder with the length at 340 nm and the width at 65 nm; the oval-shaped capsid was treated as an ellipsoid with the length at 317 nm and the width at 92 nm.

Mass spectrum analyses

Rod-shaped and oval-shaped WSSV capsids were suspended in SDS buffer [4% SDS and 100 mM tris (pH 7.5)], reduced with 10 mM dithiothreitol at 37°C for 1 hour, and transferred to the Microcon YM-30 (Millipore MRCF0R030, USA). The buffer was replaced with UA buffer [8 M urea and 100 mM tris (pH 8.5)], and proteins were alkylated with 55 mM iodoacetamide at room temperature for 15 min in the dark. The UA buffer was then replaced with 0.1 M triethylammonium bicarbonate solution (pH 8.5). Proteins were digested with sequencing grade trypsin at 37°C overnight, and the elution was collected by ultrafiltration with the cutoff at 5000 Da. Peptides were desalted by strong cation exchange StageTips and concentrated by a SpeedVac vacuum concentrator (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

Peptides were analyzed on a TripleTOF 5600 mass spectrometer (AB Sciex, USA) coupled with an Eksigent NanoLC-1D platform assembled in information-dependent mode. Peptides were identified from MS/MS spectra using ProteinPilot version 4.2 (Applied Biosystems, USA) by searching against the protein sequences of WSSV. The fixed modification was carbamidomethylation of cysteine residues. Trypsin was specified as the proteolytic enzyme with two missed cleavages. Mass tolerance was set to 0.05 Da, and the maximum false discovery rate for proteins and peptides was 1%.

Protein identification and atomic model building

Protein identification was performed on the body with the resolution at 3.3 Å. Specifically, protein sequence prediction on Arch/2 was performed in DeepTracer (41, 42). On the basis of the local resolution map, seven best resolved fragments in Arch/2 were picked up, and the predicted sequences of these fragments were used to blast against 177 annotated WSSV proteins. For all these fragments, the only blast hit was VP664. EM density of one fragment (residues from 2657 to 2826) was traced in Coot 0.8.9.1 (56) and extended to Diamond/2. Thus, both Arch/2 and Diamond/2 belong to one VP664 molecule. VP664 (ALN66566.1; access numbers were obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information protein database) were segmented into fragments with overlaps, which were predicted separately by AlphaFold-2 with the recommended parameters (57). The predicted structures of these fragments were superimposed with the counterparts built in Coot (56). The perfect superimposition further verified that VP664 is the major component for both Arch/2 and Diamond/2.

The pseudo-atomic models of VP51 (ALN66551.1), VP190 (ALN66543.1), VP136 (ALN66537.1), VP76 (ALN66517.1), and VP60 (ALN66580.1) were predicted as a whole by AlphaFold-2 (57). Each model was tentatively docked into the segmented EM density maps one by one as a rigid body in UCSF Chimera. Only VP51 can fit into the nail-like structures in the base. VP51 model was further optimized for improved local density fitting with Coot and real-space refinement with PHENIX (58).

Cryo-ET data collection

Movies of cryo-ET data were collected using the same Titan Krios G3i microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) equipped with a K3 BioQuantum direct electron detector (Gatan, USA). The cryo-EM movies were automatically collected using Thermo Fisher Tomography (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) with a slit width of 20 eV on the energy filter. The tilt series were acquired using a bidirectional acquisition scheme from −60° to +60° with a 3° increment (59). The total dose was 158 e−/Å2, the final pixel size was 1.34 Å/pix, and the target defocus was set to −4.0 μm.

Cryo-ET data analyses

All images in each tilt series were motion-corrected and dose-weighted (MotionCor2.1) before alignment (50). Tilt series were aligned using patch tracking in the IMOD package (60) without gold fiducials. Tomographic reconstructions were performed with either simultaneous iterative reconstruction technique implemented in the IMOD package (61) or weighted back-projection in IMOD. Reconstructed tomograms were binned by two and then noise-reduced by nonlinear anisotropic diffusion method in IMOD, with a typical K value of 0.05 and an iteration number of 20. Segmentation and isosurface rendering of the denoised tomograms were performed in Amira software (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Briefly, membranes, tegument, and spike proteins were recognized by human eye and then manually segmented with brush tools, thresholding tools, and interpolation method. Membranes were also processed with membrane enhancement filter. Isosurface rendering and measurements were performed on segmented components.

Infection assay

The hemopoietic tissue of healthy crayfish (Cherax quadricarinatus) (20 to 25 cm in length and 70 to 80 g in weight) was collected and digested by a 0.1% (w/v) mixture of collagenase I and IV at room temperature for 30 min. After centrifugation at 800g for 10 min, the cell pellet was suspended in Leibovitz’s L-15 medium (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone, USA), basic fibroblast growth factor (20 μg/ml), epidermal growth factor (20 μg/ml), penicillin G sodium (100 IU/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml), with a pH range of 7.0 to 7.2 adjusted with NaOH. Cells (~3.5 × 105 cells/ml) were seeded into 24-well culture plates (Corning, USA) and incubated at 28°C in a 3% CO2 incubator. When 80 to 90% confluence was achieved in the cell cultures, the medium was carefully removed, and cells were washed four to five times with the same antibiotic-free medium.

Wild-type WSSV virions, capsid-detached WSSV virions, and oval-shaped capsids were diluted to the same concentration by the FBS- and antibiotic-free medium, filtered with 0.45-μm sterile filters, and then added into the above cultured cells. The medium alone was used as the blank control. After incubation for 2 hours for virus infection, the medium was carefully removed, and fresh antibiotic-free medium was added into cell cultures. Cells were observed and photographed daily under an inverted phase-contrast microscope (OLYMPUS CKX53SF-R, Japan).

On the first and third days, the same amounts of cultured cells were collected and treated with deoxyribonuclease I (0.1 mg/ml) for 15 min at room temperature to digest viral DNA attached to the cell surface. The treated cells were washed twice with CPBS buffer [10 mM Na2HPO4, 10 mM KH2PO4, 150 mM NaCl, 10 μM CaCl2, and 10 μM MnCl2 (pH 6.8)] (62), and cell genome was extracted using the TIANamp Genomic DNA Kit (TIANGEN, China) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The extracted cell genomes were firstly analyzed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and quantified by an ultraviolet spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific NanoDrop 2000, USA) to ensure the same amount of DNA extracted.

VP28 is one of the major structural proteins of WSSV, which plays a key role in host-virus protein interactions (63, 64). The expression level of VP28 genes in the treated cells were monitored by semiquantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR; Thermo Fisher Scientific ProFlex PCR system, USA) (65) using a pair of VP28 specific primers: the forward primer of 5′-TTCACTCTTTCGGTCGTG-3′ and the reverse primer of 5′-GATTTATTTACTCGGTCTCA-3′. The extracted cell genomes at the same concentration (50 ng/μl) were added into the amplification system. The PCR products were analyzed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, and the target VP28 band at ~610 base pairs (bp) was analyzed and quantified by an ultraviolet spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific NanoDrop 2000, USA).

Acknowledgments

We thank W. Jiang from Purdue University for critical reading. We are grateful to L. Qi, D. Zhao, and C. Gao from the Cryo-EM facility for Marine Biology at QNLM for our cryo-EM data collection.

Funding: This work was supported by the following: the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFF1200400 awarded to Q.-T.S., 2017YFA0504800 awarded to Q.-T.S., and 2021YFA0909600 awarded to C.L.), the National Science Foundation of China (91851205 awarded to Y.-Z.Z., 31870743 awarded to Q.-T.S., 42076229 awarded to C.L., 32170127 awarded to P.W., and 32100028 awarded to K.L.), and the Program of Shandong for Taishan Scholars (TSPD20181203 awarded to Y.-Z.Z.).

Author contributions: Conceptualization: Q.-T.S. and Y.-Z.Z. Methodology: M.S., M.L., H.S., K.L., H.G., X.-L.C., Y.L., and J.L. Investigation: M.S., M.L., K.L., P.W., Y.Z., R.W., Y.T., L.Y., Y.Z., C.L., and X.S. Visualization: M.S., M.L., K.L., P.W., and Q.-T.S. Funding acquisition: P.W., X.-L.C., Q.-T.S., and Y.-Z.Z. Project administration: Q.-T.S. and Y.-Z.Z. Supervision: Q.-T.S. and Y.-Z.Z. Writing (original draft): M.S., M.L., H.S., K.L., and Q.-T.S. Writing (review and editing): Q.-T.S. and Y.-Z.Z.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: The cryo-EM density maps of WSSV capsids were deposited in Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB; www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/emdb/) with the accession numbers 33162 (head of the oval-shaped capsid), 33163 (base of the oval-shaped capsid), 33164 (plug of the rod-shaped capsid), 33165 (body-focal of the rod-shaped capsid), 33166 (body of the rod-shaped capsid), 33167 (base of the rod-shaped capsid), 33168 (base-focal of the rod-shaped capsid), and 33170 (neck of the rod-shaped capsid), as listed in table S1. The atom coordinate of VP51 was deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB; www.rcsb.org/) with the PDB ID codes 7XF2 (table S2). All other data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S13

Tables S1 and S2

Legends for movies S1 to S3

Other Supplementary Material for this : manuscript includes the following:

Movies S1 to S3

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.C. Li, S. Weng, J. He, WSSV-host interaction: Host response and immune evasion. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 84, 558–571 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.B. Verbruggen, L. K. Bickley, R. van Aerle, K. S. Bateman, G. D. Stentiford, E. M. Santos, C. R. Tyler, Molecular mechanisms of white spot syndrome virus infection and perspectives on treatments. Viruses 8, 23 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.H.-C. Wang, I. Hirono, M. B. Bacano Maningas, K. Somboonwiwat, G. Stentiford; Ictv Report Consortium , ICTV virus taxonomy profile: Nimaviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 100, 1053–1054 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.J. H. Leu, F. Yang, X. Zhang, X. Xu, G. H. Kou, C. F. Lo, Whispovirus. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 328, 197–227 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.S. K. Chandrika, S. T. Puthiyedathu, Challenges and prospects of viral envelope protein VP28-based control strategies to combat white spot syndrome virus in penaeid shrimps: A review. Rev. Aquac. 13, 734–743 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 6.B. K. Dey, G. H. Dugassa, S. M. Hinzano, P. Bossier, Causative agent, diagnosis and management of white spot disease in shrimp: A review. Rev. Aquac. 12, 822–865 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 7.G. D. Stentiford, D. M. Neil, E. J. Peeler, J. D. Shields, H. J. Small, T. W. Flegel, J. M. Vlak, B. Jones, F. Morado, S. Moss, J. Lotz, L. Bartholomay, D. C. Behringer, C. Hauton, D. V. Lightner, Disease will limit future food supply from the global crustacean fishery and aquaculture sectors. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 110, 141–157 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D. V. Lightner, R. M. Redman, C. R. Pantoja, K. F. J. Tang, B. L. Noble, P. Schofield, L. L. Mohney, L. M. Nunan, S. A. Navarro, Historic emergence, impact and current status of shrimp pathogens in the Americas. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 110, 174–183 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.P. J. Walker, C. V. Mohan, Viral disease emergence in shrimp aquaculture: Origins, impact and the effectiveness of health management strategies. Rev Aquac. 1, 125–154 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.J. M. Tsai, H. C. Wang, J. H. Leu, H. H. Hsiao, A. H. J. Wang, G. H. Kou, C. F. Lo, Genomic and proteomic analysis of thirty-nine structural proteins of shrimp white spot syndrome virus. J. Virol. 78, 11360–11370 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.C. J. D’Arcy, L. L. Domier, Luteoviridae, in Virus taxonomy. VIIIth report of the international committee on taxonomy of viruses, C. M. Fauquet, M. A. Mayo, J. Maniloff, U. Desselberger, L. A. Ball, Eds. (Elsevier/Academic Press, 2005), pp. 891–900. [Google Scholar]

- 12.S. Durand, D. V. Lightner, R. M. Redman, J. R. Bonami, Ultrastructure and morphogenesis of White Spot Syndrome Baculovirus (WSSV). Dis. Aquat. Organ. 29, 205–211 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Z. Li, Q. Lin, J. Chen, J. L. Wu, T. K. Lim, S. S. Loh, X. Tang, C. L. Hew, Shotgun identification of the structural proteome of shrimp white spot syndrome virus and iTRAQ differentiation of envelope and nucleocapsid subproteomes. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 6, 1609–1620 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.X. Xie, L. Xu, F. Yang, Proteomic analysis of the major envelope and nucleocapsid proteins of white spot syndrome virus. J. Virol. 80, 10615–10623 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.J. M. Tsai, H. C. Wang, J. H. Leu, A. H. J. Wang, Y. Zhuang, P. J. Walker, G. H. Kou, C. F. Lo, Identification of the nucleocapsid, tegument, and envelope proteins of the shrimp white spot syndrome virus virion. J. Virol. 80, 3021–3029 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Q. Wan, L. M. Xu, F. Yang, VP26 of white spot syndrome virus functions as a linker protein between the envelope and nucleocapsid of virions by binding with VP51. J. Virol. 82, 12598–12601 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.P. Jaree, S. Senapin, I. Hirono, C. F. Lo, A. Tassanakajon, K. Somboonwiwat, WSV399, a viral tegument protein, interacts with the shrimp protein PmVRP15 to facilitate viral trafficking and assembly. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 59, 177–185 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.M. C. van Hulten, J. Witteveldt, S. Peters, N. Kloosterboer, R. Tarchini, M. Fiers, H. Sandbrink, R. K. Lankhorst, J. M. Vlak, The white spot syndrome virus DNA genome sequence. Virology 286, 7–22 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.C. H. Huang, L. R. Zhang, J. H. Zhang, L. C. Xiao, Q. J. Wu, D. H. Chen, J. K. K. Li, Purification and characterization of white spot syndrome virus (WSSV) produced in an alternate host: Crayfish, Cambarus clarkii. Virus Res. 76, 115–125 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.A. S. Hameed, M. Anilkumar, M. L. S. Raj, K. Jayaraman, Studies on the pathogenicity of systemic ectodermal and mesodermal baculovirus and its detection in shrimp by immunological methods. Aquaculture 160, 31–45 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 21.L. Li, Y. Hong, D. Huo, P. Cai, Ultrastructure analysis of white spot syndrome virus (WSSV). Arch. Virol. 165, 407–412 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.L. K. Liu, M. J. Liu, D. L. Li, H. P. Liu, Recent insights into anti-WSSV immunity in crayfish. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 116, 103947 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.J. Mercer, M. Schelhaas, A. Helenius, Virus entry by endocytosis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 79, 803–833 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.S. C. Zheng, J. Y. Xu, H. P. Liu, Cellular entry of white spot syndrome virus and antiviral immunity mediated by cellular receptors in crustaceans. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 93, 580–588 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.C. Meng, L. K. Liu, D. L. Li, R. L. Gao, W. W. Fan, K. J. Wang, H. C. Wang, H. P. Liu, White spot syndrome virus benefits from endosomal trafficking, substantially facilitated by a valosin-containing protein, to escape autophagic elimination and propagate in the crustacean Cherax quadricarinatus. J. Virol. 94, e01570-20 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.W. J. Liu, Y. S. Chang, A. H. Wang, G. H. Kou, C. F. Lo, White spot syndrome virus annexes a shrimp STAT to enhance expression of the immediate-early gene ie1. J. Virol. 81, 1461–1471 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.D. W. Bauer, J. B. Huffman, F. L. Homa, A. Evilevitch, Herpes virus genome, the pressure is on. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 11216–11221 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.A. Brandariz-Nunez, T. Liu, T. Du, A. Evilevitch, Pressure-driven release of viral genome into a host nucleus is a mechanism leading to herpes infection. eLife 8, e47212 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.A. Evilevitch, L. T. Fang, A. M. Yoffe, M. Castelnovo, D. C. Rau, V. A. Parsegian, W. M. Gelbart, C. M. Knobler, Effects of salt concentrations and bending energy on the extent of ejection of phage genomes. Biophys. J. 94, 1110–1120 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.A. Evilevitch, L. Lavelle, C. M. Knobler, E. Raspaud, W. M. Gelbart, Osmotic pressure inhibition of DNA ejection from phage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 9292–9295 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.D. E. Smith, S. J. Tans, S. B. Smith, S. Grimes, D. L. Anderson, C. Bustamante, The bacteriophage straight phi29 portal motor can package DNA against a large internal force. Nature 413, 748–752 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.M. McElwee, S. Vijayakrishnan, F. Rixon, D. Bhella, Structure of the herpes simplex virus portal-vertex. PLOS Biol. 16, e2006191 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.F. Yang, J. He, X. Lin, Q. Li, D. Pan, X. Zhang, X. Xu, Complete genome sequence of the shrimp white spot bacilliform virus. J. Virol. 75, 11811–11820 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.X. Xie, H. Li, L. Xu, F. Yang, A simple and efficient method for purification of intact white spot syndrome virus (WSSV) viral particles. Virus Res. 108, 63–67 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.D. L. Caspar, K. Namba, Switching in the self-assembly of tobacco mosaic virus. Adv. Biophys. 26, 157–185 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.A. Kendall, M. McDonald, G. Stubbs, Precise determination of the helical repeat of tobacco mosaic virus. Virology 369, 226–227 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.M. Luo, The nucleocapsid of vesicular stomatitis virus. Sci. China Life Sci. 55, 291–300 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.P. Ge, J. Tsao, S. Schein, T. J. Green, M. Luo, Z. H. Zhou, Cryo-EM model of the bullet-shaped vesicular stomatitis virus. Science 327, 689–693 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.F. Wang, V. Cvirkaite-Krupovic, M. Vos, L. C. Beltran, M. A. B. Kreutzberger, J.-M. Winter, Z. Su, J. Liu, S. Schouten, M. Krupovic, E. H. Egelman, Spindle-shaped archaeal viruses evolved from rod-shaped ancestors to package a larger genome. Cell 185, 1297–1307.e11 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.T. Xu, X. Shan, Y. Li, T. Yang, G. Teng, Q. Wu, C. Wang, K. F. J. Tang, Q. Zhang, X. Jin, White spot syndrome virus (WSSV) prevalence in wild crustaceans in the Bohai Sea. Aquaculture 542, 736810 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 41.L. Chang, F. Wang, K. Connolly, H. Meng, Z. Su, V. Cvirkaite-Krupovic, M. Krupovic, E. H. Egelman, D. Si, DeepTracer-ID: De novo protein identification from cryo-EM maps. Biophys. J. 121, 2840–2848 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.J. Pfab, N. M. Phan, D. Si, DeepTracer for fast de novo cryo-EM protein structure modeling and special studies on CoV-related complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2017525118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.J. H. Leu, J. M. Tsai, H. C. Wang, A. H. J. Wang, C. H. Wang, G. H. Kou, C. F. Lo, The unique stacked rings in the nucleocapsid of the white spot syndrome virus virion are formed by the major structural protein VP664, the largest viral structural protein ever found. J. Virol. 79, 140–149 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.C. Wu, F. Yang, Localization studies of two white spot syndrome virus structural proteins VP51 and VP76. Virol. J. 3, 76 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.R. Hochstein, D. Bollschweiler, S. Dharmavaram, N. G. Lintner, J. M. Plitzko, R. Bruinsma, H. Engelhardt, M. J. Young, W. S. Klug, C. M. Lawrence, Structural studies of Acidianus tailed spindle virus reveal a structural paradigm used in the assembly of spindle-shaped viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 2120–2125 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.S. Johnson, Y. H. Fong, J. C. Deme, E. J. Furlong, L. Kuhlen, S. M. Lea, Symmetry mismatch in the MS-ring of the bacterial flagellar rotor explains the structural coordination of secretion and rotation. Nat. Microbiol. 5, 966–975 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.J. Tan, X. Zhang, X. Wang, C. Xu, S. Chang, H. Wu, T. Wang, H. Liang, H. Gao, Y. Zhou, Y. Zhu, Structural basis of assembly and torque transmission of the bacterial flagellar motor. Cell 184, 2665–2679.e19 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Z. Li, X. Zhang, L. Dong, J. Pang, M. Xu, Q. Zhong, M. S. Zeng, X. Yu, CryoEM structure of the tegumented capsid of Epstein-Barr virus. Cell Res. 30, 873–884 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.R. F. Thompson, M. G. Iadanza, E. L. Hesketh, S. Rawson, N. A. Ranson, Collection, pre-processing and on-the-fly analysis of data for high-resolution, single-particle cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Protoc. 14, 100–118 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.S. Q. Zheng, E. Palovcak, J. P. Armache, K. A. Verba, Y. Cheng, D. A. Agard, MotionCor2: Anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Methods 14, 331–332 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.A. Rohou, N. Grigorieff, CTFFIND4: Fast and accurate defocus estimation from electron micrographs. J. Struct. Biol. 192, 216–221 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.J. Zivanov, T. Nakane, B. O. Forsberg, D. Kimanius, W. J. H. Hagen, E. Lindahl, S. H. W. Scheres, New tools for automated high-resolution cryo-EM structure determination in RELION-3. eLife 7, e42166 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.A. Punjani, J. L. Rubinstein, D. J. Fleet, M. A. Brubaker, cryoSPARC: Algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat Methods 14, 290–296 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.E. F. Pettersen, T. D. Goddard, C. C. Huang, G. S. Couch, D. M. Greenblatt, E. C. Meng, T. E. Ferrin, UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.G. Tang, L. Peng, P. R. Baldwin, D. S. Mann, W. Jiang, I. Rees, S. J. Ludtke, EMAN2: An extensible image processing suite for electron microscopy. J. Struct. Biol. 157, 38–46 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.P. Emsley, B. Lohkamp, W. G. Scott, K. Cowtan, Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 486–501 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.J. Jumper, R. Evans, A. Pritzel, T. Green, M. Figurnov, O. Ronneberger, K. Tunyasuvunakool, R. Bates, A. Žídek, A. Potapenko, A. Bridgland, C. Meyer, S. A. A. Kohl, A. J. Ballard, A. Cowie, B. Romera-Paredes, S. Nikolov, R. Jain, J. Adler, T. Back, S. Petersen, D. Reiman, E. Clancy, M. Zielinski, M. Steinegger, M. Pacholska, T. Berghammer, S. Bodenstein, D. Silver, O. Vinyals, A. W. Senior, K. Kavukcuoglu, P. Kohli, D. Hassabis, Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.P. D. Adams, P. V. Afonine, G. Bunkóczi, V. B. Chen, I. W. Davis, N. Echols, J. J. Headd, L. W. Hung, G. J. Kapral, R. W. Grosse-Kunstleve, A. J. McCoy, N. W. Moriarty, R. Oeffner, R. J. Read, D. C. Richardson, J. S. Richardson, T. C. Terwilliger, P. H. Zwart, PHENIX: A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Q. S. Zheng, M. B. Braunfeld, J. W. Sedat, D. A. Agard, An improved strategy for automated electron microscopic tomography. J. Struct. Biol. 147, 91–101 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.J. R. Kremer, D. N. Mastronarde, J. R. McIntosh, Computer visualization of three-dimensional image data using IMOD. J. Struct. Biol. 116, 71–76 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.J. I. Agulleiro, J. J. Fernandez, Fast tomographic reconstruction on multicore computers. Bioinformatics 27, 582–583 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.X. Xu, H. Duan, Y. Shi, S. Xie, Z. Song, S. Jin, F. Li, J. Xiang, Development of a primary culture system for haematopoietic tissue cells from Cherax quadricarinatus and an exploration of transfection methods. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 88, 45–54 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.M. Sanjuktha, V. Stalin Raj, K. Aravindan, S. V. Alavandi, M. Poornima, T. C. Santiago, Comparative efficacy of double-stranded RNAs targeting WSSV structural and nonstructural genes in controlling viral multiplication in Penaeus monodon. Arch. Virol. 157, 993–998 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.G. Yi, Z. Wang, Y. Qi, L. Yao, J. Qian, L. Hu, Vp28 of shrimp white spot syndrome virus is involved in the attachment and penetration into shrimp cells. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 37, 726–734 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Q. Han, P. Li, X. Lu, Z. Guo, H. Guo, Improved primary cell culture and subculture of lymphoid organs of the greasyback shrimp Metapenaeus ensis. Aquaculture 410-411, 101–113 (2013). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figs. S1 to S13

Tables S1 and S2

Legends for movies S1 to S3

Movies S1 to S3