Abstract

A wide array of biocompatible micro/nanorobots are designed for targeted drug delivery and precision therapy largely depending on their self-adaptive ability overcoming complex barriers in vivo. Here, we report a twin-bioengine yeast micro/nanorobot (TBY-robot) with self-propelling and self-adaptive capabilities that can autonomously navigate to inflamed sites for gastrointestinal inflammation therapy via enzyme-macrophage switching (EMS). Asymmetrical TBY-robots effectively penetrated the mucus barrier and notably enhanced their intestinal retention using a dual enzyme-driven engine toward enteral glucose gradient. Thereafter, the TBY-robot was transferred to Peyer’s patch, where the enzyme-driven engine switched in situ to macrophage bioengine and was subsequently relayed to inflamed sites along a chemokine gradient. Encouragingly, EMS-based delivery increased drug accumulation at the diseased site by approximately 1000-fold, markedly attenuating inflammation and ameliorating disease pathology in mouse models of colitis and gastric ulcers. These self-adaptive TBY-robots represent a safe and promising strategy for the precision treatment of gastrointestinal inflammation and other inflammatory diseases.

Self-adaptive yeast micro/nanorobots cross biological barriers via enzyme-macrophage engine switching to reach inflamed sites.

INTRODUCTION

Gastrointestinal (GI) inflammation, such as chronic gastritis and inflammatory bowel disease, is a complex inflammatory disorder of the GI tract and increases the risk of cancer (1, 2). Current delivery systems are immobile and rely on passive diffusion to reach inflamed sites, which leads to frequent dosing and potentially severe side effects that can adversely affect patients’ adherence to medication (3). Hence, there is an immense unmet clinical need for active and targeted GI inflammation therapies.

Micro/nanorobots are miniaturized smart devices that can convert internal energy or external physical stimuli into mechanical force to generate autonomous motion. One of the main applications of micro/nanorobots is targeted drug delivery because they can actively shuttle through the human body, driven by various propulsion modes, to reach diseased regions that are difficult to access by conventional administration methods (4, 5). Among these devices, chemically/biochemically propelled micro/nanorobots, in particular, show great potential for in vivo GI inflammation applications owing to their co-option use of biocompatible endogenous fuels (6).

The use of enzymes as catalytic bioengines is emerging as an attractive and valid approach because of their ability to convert their biocompatible substrate biofuel into a driving force (7). Such enzyme-powered robots are successfully fabricated through the asymmetric immobilization of enzymes onto inorganic substance surfaces or the coloading of enzymes into asymmetric polymersomes (8–10), which exhibit attractive collectively driven forces across a specific barrier in response to an enzyme substrate gradient. In addition, having evolved with diverse and unique capabilities ranging from rapid capture and sensitive chemotaxis, natural living cells are another endogenous biochemical engine demonstrated to propel cell-like micro/nanorobot precise movement (11, 12). For instance, macrophages, a cell type with migration and chemotaxis properties, can penetrate biological barriers and target inflamed sites by following the chemokine concentration gradient (13, 14). In addition, the utilization of autonomously motile cells allows for built-in chemotactic motion, which eliminates the need for harmful fuels or complex actuation equipment (12). However, because of the limitation of single-engine propulsion, self-propelled micro/nanorobots are predominantly confined to local physiological environments, such as the stomach, bladder, blood vessels, and GI tract (8, 11, 15–17). It is difficult to adjust to the microenvironmental changes encountered in crossing multiple biological barriers to reach long-distance or deep-seated lesions. Overall, it remains challenging to develop self-adaptive micro/nanorobots that can adjust their driving mechanisms to achieve continuous and directional propulsion for active target delivery in a complex GI microenvironment.

It is very important to design intelligent micro/nanorobots with biomimetic and biocompatible materials to prevent potential toxicity and pathogenicity in GI inflammation applications (18). Yeast microcapsules (YCs) are biodegradable, natural, hollow, porous, and uniform microspheres into which chemical agents or nanoparticles (NPs) can be packaged (19, 20). They are derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which has long been known for its use in beer brewing and bread making and is considered a safe probiotic (21). Thus, YC has great potential to be used as a biocompatible and smart material to design GI micro/nanorobots. However, less than 0.1% of YCs are retained in the intestinal tract after oral administration owing to rapid intestinal motility and the inability of YCs to actively penetrate the intestinal mucus barrier (22). Fortunately, YCs retained in the intestinal tract can be specifically recognized and efficiently endocytosed by macrophages in Peyer’s patches (23), thus enabling the YC-encapsulated nanodrug to switch from the intestinal tract to the circulatory system. In blood circulation, macrophages with inflammatory chemotaxis, as a natural driving bioengine, can effectively facilitate the active transport and delivery of nanodrugs to disease sites, which is very important for the treatment of GI inflammation. Because of the complete difference between GI intraluminal and extraluminal environments, YC-based robots need at least two engines to overcome multiple barriers for the treatment of GI inflammatory diseases.

Here, we aimed to develop a self-adaptive micro/nanorobot to cross multiple biological barriers and achieve active and accurate drug delivery for GI inflammation therapy. To this end, we constructed a twin-bioengine yeast micro/nanorobot (TBY-robot) with self-driving and self-adaptive capabilities that can autonomously navigate to the sites of GI inflammation via enzyme-macrophage switching (EMS). Glucose oxidase (GOx) and catalase (Cat) are extensively used as feed additives to relieve oxidative stress, maintain microbiota homeostasis, and enhance gut function because of their excellent stability in the animal intestinal tract (24, 25). Thus, the TBY-robot was synthesized by asymmetrically immobilizing GOx and Cat onto the surface of anti-inflammatory NP-packaged YCs (NPYs). At a homogeneous glucose concentration, the Janus distribution of enzymes can catalyze the decomposition of glucose to generate a local glucose gradient for TBY-robot self-propelling motion. In the presence of an enteral glucose gradient, the oral TBY-robots move toward the glucose gradient to penetrate the intestinal mucus barrier and then cross the intestinal epithelial barrier by microfold cell transcytosis. After in situ switching to the macrophage bioengine in Peyer’s patch, the TBY-robots autonomously migrate to inflamed sites of the GI tract through chemokine-guided macrophage relay delivery (Fig. 1A). In inflamed colon and stomach mouse models, TBY-robots markedly attenuated inflammation and ameliorated disease pathology. The bioinspired TBY-robots exhibited enzyme actuation and macrophage relay characteristics, especially EMS ability, enabling autonomous adaptation to changes in the surrounding environment to penetrate multiple biological barriers to reach deep-seated inflamed sites for precision GI inflammation therapy.

Fig. 1. TBY-robots using enzyme actuation and macrophage relay for GI inflammation treatment.

(A) Schematic outline of the fabrication of the TBY-robot and its application for active target delivery and GI inflammation treatment. (B) SEM image of a TBY-robot. Scale bar, 1 μm. (C) Fluorescence image characterization of the Janus coating of GOx (Cy5.5, red) and Cat (FITC, green) on the TBY-robot. Scale bar, 1 μm. (D) Protein amounts in NPY and TBY-robot (both 2 × 109/ml) were analyzed by bicinchoninic acid protein assay. NPY group, the residual protein of YC. Two-tailed Student’s t tests. ***P < 0.001. (E) The remaining enzyme activity of GOx and Cat decorating the surface of the TBY-robot was analyzed by the Amplex Red assay. Data are presented as the means ± SD. n = 3 biologically independent samples. (F) Representative fluorescence image (top) of TBY-robot loaded with Cur (autofluorescence, green) at an NP/YC ratio of 3. Scale bar, 5 μm. TEM image (bottom) of a TBY-robot. Red arrows indicate the boundary of conjugated enzymes. Blue arrows indicate the packaged NPs. Scale bar, 1 μm. (G) The loading content and encapsulation efficiency of Cur and 5-ASA (means ± SD; n = 5). (H) In vitro drug release profiles of TBY-robots. Cumulative release of 5-ASA from bare or enteric-coated TBY-robotI and cumulative release of Cur from bare TBY-robotII or enteric-coated TBY-robotII at pH 1.2 (simulated gastric fluids, left) or pH 7.4 (simulated intestinal fluids, right). The results are expressed as the means ± SD; n = 5.

RESULTS

TBY-robots are synthesized by sequential modification method for oral delivery

The Janus TBY-robot was constructed in three main sequential modification steps: NP self-deposition, asymmetric surface activation, and GOx/Cat immobilization (Fig. 1A). Initially, YCs approximately 5.0 μm in diameter were purified from S. cerevisiae by acidic and alkaline extraction to remove the cytoplasm and cell-wall polysaccharides (26). Cationic NPYs were prepared by electrostatic self-deposition (27). To accomplish asymmetric surface activation, an NPY film was formed on the surface of a dish through glycerol plasticizer assistance. This process enabled the partial masking of the NPYs and subsequently allowed the upper side of the film to be activated. Next, imidazole carbamate linkages for coupling with amine ligands (─NH2) were sequentially introduced onto hydroxyl groups (─OH) of the upper hemisphere of YC by N, N′-carbonyl diimidazole (CDI) activation (28, 29). Afterward, the resulting NPYs with asymmetrically activated surfaces were dissociated from the dish. Last, TBY-robots were obtained by coupling abundant ─NH2-containing GOx and Cat with asymmetrically activated NPYs. For application in the intestinal tract environment, TBY-robots were coated with a pH-responsive enteric polymer (soluble when pH ≥ 5.5) (16) to protect them against gastric acid.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images indicate that the TBY-robots have a typical Janus structure (Fig. 1B and fig. S1A). The energy-dispersive x-ray spectroscopy (EDS) mapping images displayed the signal of nitrogen (N) element presented on one side of the YC, illustrating the asymmetrical distribution of enzymes on the TBY-robot surface (fig. S1B). Furthermore, the TBY-robots were characterized by fluorescence microscopy imaging using cyanine (Cy5.5)–labeled GOx and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–labeled Cat. The merged images verified the successful asymmetric immobilization of the two enzymes GOx and Cat on the TBY-robot surface (Fig. 1C).

A protein quantification assay showed that the protein content of the TBY-robots reached approximately 1200 μg/ml and was markedly higher than that of NPYs, which may be ascribed to the dual enzymes immobilized on the surface of the TBY-robots (Fig. 1D). We also estimated the enzymatic activity by a commercial Amplex Red assay. The bioactivities of GOx and Cat were 156 and 830 mU/ml, respectively (Fig. 1E). Moreover, the enzyme immobilization maintained approximately 97% of the bioactivities of GOx and Cat (fig. S2). These results indicated that GOx and Cat were efficiently decorated on the YCs and retained their activities after the immobilization step.

To evaluate the drug loading efficiency, we selected 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA), a first-line anti-inflammatory agent for the treatment of ulcerative colitis (30), and curcumin (Cur), a pleiotropic anti-inflammatory therapeutic drug (31), for study. Flow cytometry analysis revealed that the optimal condition for packaging Cur was a Cur-loaded nanoparticle (CP)/YC weight ratio of 3:1 (fig. S3). The merged image of the bright-field and Cur (excitation/emission = 488/535 nm) channels confirmed that the CPs were efficiently packaged into TBY-robots (TBY-robotII) (Fig. 1F, top). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images verified the Janus structure of the yeast robot and demonstrated that 5-ASA–loaded nanoparticles (APs) could also be efficiently packaged into TBY-robots (TBY-robotI) (Fig. 1F, bottom, and fig. S4). The Cur and 5-ASA encapsulation efficiencies of the TBY-robots were 84.26 and 80.62%, respectively, and the loading contents of the TBY-robots were 55.48 and 45.92 μg/mg, respectively (Fig. 1G). These results indicate that TBY-robot is a high-efficiency drug carrier.

Subsequently, we separately analyzed the drug release profiles of TBY-robotI and TBY-robotII with or without enteric coating at pH 1.2 (simulated gastric fluids) and pH 7.4 (simulated intestinal fluids). Both TBY-robotsI and TBY-robotsII with enteric coating showed negligible drug release (~2.5%) within 5 hours at pH 1.2, suggesting that the pH-responsive enteric polymer protects TBY-robots against gastric acid (Fig. 1H, left). Similar to the acid environment, enteric TBY-robotsI and enteric TBY-robotsII exhibited minimal drug release (~7%) within 72 hours at pH 7.4 (Fig. 1H, right). Conversely, bare TBY-robotsI and TBY-robotsII showed rapid and efficient drug release (~85%) at pH 1.2 (Fig. 1H, left), indicating that TBY-robots are acid-responsive drug release systems. Together, these results revealed that enteric-coated TBY-robots have good stability and that their packaged drugs do not easily leak into the GI tract.

TBY-robots exhibit self-propulsion toward a glucose gradient

The Janus distribution of GOx and Cat over the YC surface results in an asymmetric biocatalytic decomposition cascade of biocompatible glucose: Glucose is oxidized by GOx into d-glucono-δ-lactone and hydrogen peroxide, and the latter is then decomposed by Cat into oxygen and water (32). d-glucono-δ-lactone reduces the pH of the solution (32) to protect GOx against the alkaline environment in the small intestine (fig. S5). The reaction is illustrated in Fig. 1A and described by Eq. 1

| (1) |

In a homogeneous glucose environment, the TBY-robot generates a local glucose concentration gradient around itself, which can give rise to convective flows and drive the TBY-robots to undergo self-diffusiophoretic motion.

To confirm the mechanism of propulsion of the TBY-robots, motion data were acquired by optical tracking of individual TBY-robots. Figure 2A (and corresponding movie S1) displays the typical tracking trajectories of the TBY-robots in the presence of different glucose concentrations and illustrates enhanced active motion with increasing concentrations of glucose as fuel. To determine which side of the TBY-robot is in front when self-propulsion occurs, we observed the motion of the TBY-robot by fluorescence microscopy using FITC-labeled Cat in the presence of 50 mM glucose. The results revealed that the no-enzyme side of the TBY-robot is in the front during self-diffusiophoretic motion (movie S2). Considering that the intestinal tract environment contains food microparticles, we investigated whether TBY-robots can actively avoid obstacles in a glucose solution. The time-lapse images in Fig. 2B, captured from movie S3, show the whole process by which an individual TBY-robot approached, escaped, and bypassed a static YC obstacle by alternating reorientation and self-diffusiophoretic movement modes. Hence, TBY-robots are potentially capable of effectively avoiding food microparticle obstacles in intestinal tract environments.

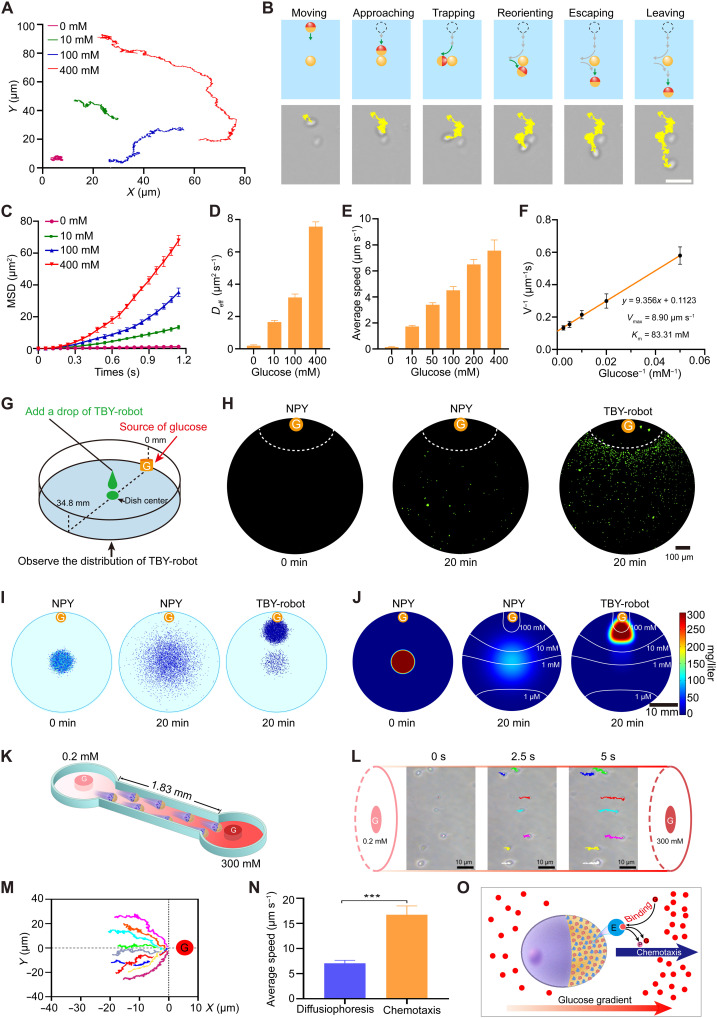

Fig. 2. Active chemotaxis of TBY-robots in the presence of a glucose gradient.

(A) Optical tracking trajectories (over 20 s) of TBY-robot in glucose solutions with different concentrations. (B) Schemes showing a TBY-robot bypassing an obstacle in a 20 mM glucose solution. A static YC represents a microsize obstacle. Scale bar, 10 μm. (C) MSD of TBY-robots at different glucose concentrations over time. n = 15 at each point. The Deff (D), average speed (E), and Lineweaver-Burk plots (F) of TBY-robots in the different glucose concentrations. (G) Schematic design of experiments observing the chemotactic motion of TBY-robots along a glucose gradient. G, glucose-soaked agarose gel. (H) The corresponding fluorescence images of NPYs and TBY-robots at 0 and 20 min. Dotted line, edge of the G. (I and J) Simulation of motion (I) and heating map of the concentration (J) of NPYs and TBY-robots. White lines, glucose gradient. (K) Schematic analysis of the chemotactic motion of TBY-robots by a microfluidic device. The length of the channel represents the distance from the center of the intestinal lumen to the intestinal wall of mice. The glucose (G) gradient from the intestinal lumen to the intestinal wall is 0.2 to 300 mM. (L) Time-lapse images of the chemotactic motion of TBY-robots toward high–glucose concentration region. (M) Normalized track trajectories of the chemotaxis of TBY-robots. (N) The average speed of TBY-robots in a homogeneous glucose concentration (300 mM) and corresponding glucose gradients. n = 5; two-tailed Student’s t tests. ***P < 0.001. (O) Schematic of the mechanism of the chemotactic motion of TBY-robots. After glucose binds to an enzyme, the resulting complex has two possible fates, unbinding or catalytic turnover. E, enzyme; P, product.

On the basis of the X-Y coordinates of the TBY-robot trajectories, the mean-squared displacement (MSD) was calculated as a function of the time interval (Δt) in the presence of different glucose concentrations. As shown in Fig. 2C, the MSD curve was linear in the absence of glucose, which is typical of Brownian motion (33). In contrast, the MSD curves in the presence of glucose showed a parabolic shape, in which the slope increased with increasing glucose concentration. These results demonstrated that TBY-robots exhibited effective directional movement at different glucose concentrations. Figure 2D shows that the effective diffusion coefficient (Deff) of TBY-robots increased with increasing glucose concentration. The Deff values for TBY-robots were calculated to be ~0.193 and ~ 7.560 μm2 s−1 in the absence and presence of 400 mM glucose, respectively, showing a 39.2-fold increase over the value corresponding to Brownian motion. These results further suggested the robust self-propulsion of TBY-robots in the presence of glucose. Moreover, the speed of TBY-robot motion gradually increased with increasing glucose concentration (Fig. 2E). The maximum propulsion velocity (Vmax) and the Michaelis-Menten constant (Km) were calculated by using a Lineweaver-Burk plot (33). The Vmax and Km values of the TBY-robots were determined to be 8.90 μm s−1 and 83.31 mM, respectively (Fig. 2F). These results confirmed that TBY-robot self-propulsion is driven by enzyme bioengines using glucose fuel. Most notably, the TBY-robots were able to propel themselves at very low concentrations of glucose (10 mM). It has been reported that the postprandial glucose concentrations in the lumen of the rat and human small intestine are approximately 50 and 48 mM, respectively (34). The high physiological glucose concentrations of the intestinal tract could thus generate sufficient power for enzyme bioengines to propel the motion of the TBY-robots.

To gain further insight into the TBY-robot response to a glucose gradient, we performed experiments to more clearly visualize their motion capability in the presence of an external gradient of glucose using the approach shown in Fig. 2G. A cylindrical agarose gel presoaked in a 1 M glucose solution was placed on the edge of a petri dish filled with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). FITC-labeled NPYs or FITC-labeled TBY-robots were added to the center of the dish with a dropper and directly imaged with a fluorescence camera at different time points. Fluorescence imaging showed that no fluorescence signal was detected around the agarose at 0 min (Fig. 2H). After 20 min, a small number of NPYs were randomly distributed around the agarose gel, suggesting that the motion of NPYs is due to Brownian diffusion. However, a large number of TBY-robots accumulated in an orderly arrangement around the agarose gel (Fig. 2H). The distributions of NPYs and TBY-robots were further recorded, and TBY-robots across the whole petri dish were simulated by using a two-dimensional (2D) fluid model. We observed that the TBY-robots concentrated toward the glucose source from 0 to 20 min after administration (Fig. 2, I and J). TBY-robots exhibit long-range self-propulsion toward glucose sources over time scales of minutes and length scales 105 times longer than their own size.

Notably, small intestinal epithelial cells secrete digestive multienzymes capable of breaking carbohydrates into glucose (35, 36). Moreover, intestinal epithelial cells contain many transport proteins capable of actively absorbing glucose from the intestinal lumen, with a consequent high flow of glucose from the intestinal lumen to the intestinal epithelium (34, 37). Thus, we next analyzed the self-propelling mechanism and efficiency of TBY-robots under a physiological environment in the small intestine of mice by a microfluidic device (Fig. 2K), in which the radius is 1.83 mm (38) and the glucose gradient is 0.2 to 300 mM (36). The time-lapse images of TBY-robots show that these robots could sense the local glucose gradient, align, and move along the glucose gradient toward the high-glucose areas (Fig. 2L and corresponding movie S4). Obviously, the normalized trajectories of TBY-robots are biased toward the source of glucose, representing a positive chemotaxis (Fig. 2M). The chemotactic speed of TBY-robots in the physiological glucose gradient is 16.74 μm s−1, which is 2.4-fold higher than that in the homogeneous glucose concentration (300 mM), and they are capable of rapidly reaching the intestinal wall within 2 min by directional chemotactic motion (Fig. 2N). Hence, the high-glucose gradients naturally exist in the intestinal tract, which ensures the chemotactic motion of TBY-robots in vivo after oral delivery. Meanwhile, according to the previous theoretical analysis and numerical simulation of enzymes and enzyme-coated motors movement (39–43), we speculate that the positive chemotaxis of TBY-robots arises from a thermodynamic driving force that lowers the chemical potential of the system because of favorable enzyme-substrate binding. Glucose gradient–induced TBY-robot chemotaxis by cross-diffusion transfers robots toward regions of higher glucose concentration (Fig. 2O). Together, these data support the conclusion that TBY-robots have a strong chemotactic capability, which could enable efficient navigation across the intestinal barrier.

TBY-robots penetrate intestinal barrier and switch to macrophage bioengine

To examine whether TBY-robots could actively penetrate the intestinal barrier, we first established a 3D human intestinal model composed of epithelial cells and mucus barriers (Fig. 3A). A monolayer of Caco-2 cells was seeded on the apical side of porous (8-μm) Transwell inserts as the intestinal epithelial barrier. After that, the inserts were inverted, and a human B-lymphocyte cell (Raji cell) secreting inflammatory mediators was seeded at the basolateral side of the inserts to convert Caco-2 cells to microfold cells (44). Phorbol myristate acetate (PMA)–stimulated THP-1 macrophages were cultivated at the bottom of the Transwell. Biosimilar mucus (45) was added to the insert as an intestinal mucus barrier 5 min before the addition of glucose at a physiological concentration (50 mM) and TBY-robots. The penetration of TBY-robots across the intestinal barrier and subsequent switch to the macrophage bioengine were imaged by confocal microscopy.

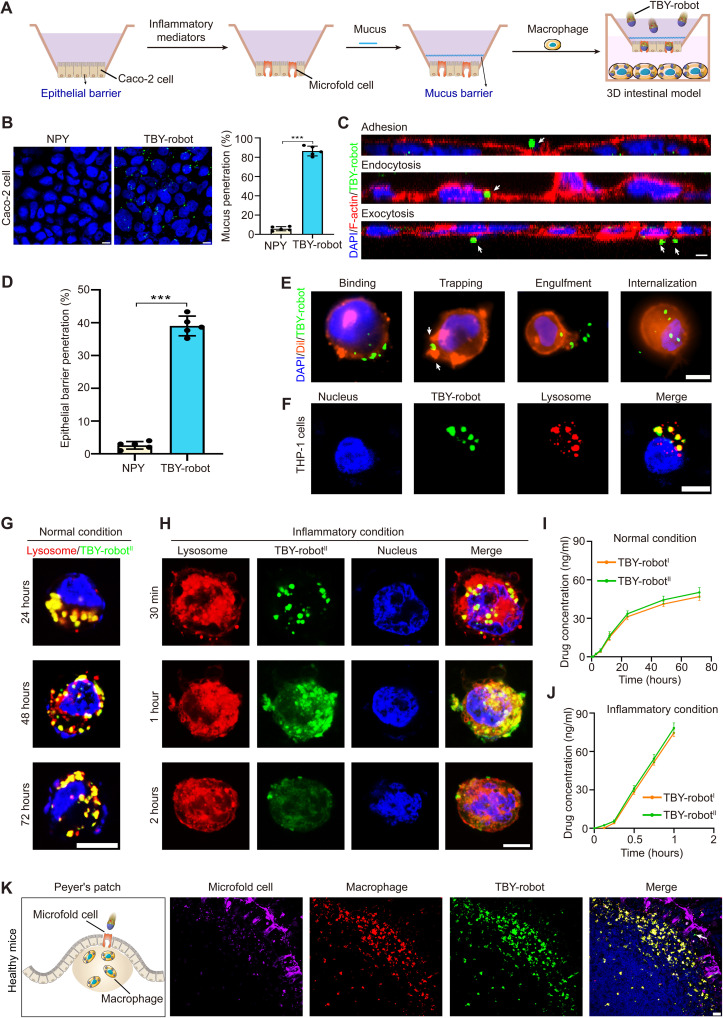

Fig. 3. TBY-robots actively penetrated the intestinal barrier and switched to the macrophage bioengine.

(A) Schematic illustration of TBY-robot penetration of the intestinal barrier and switching to the macrophage bioengine in a human 3D intestinal model. (B) FITC-labeled TBY-robots (green) crossed the intestinal mucus barrier and reached the underlying Caco-2 cells. Nuclei (DAPI, blue). Scale bar, 10 μm. The mucus penetration ratio of the TBY-robot was analyzed by flow cytometry. (C) Caco-2 cells were analyzed by confocal microscopy (XZ section). Nuclei (DAPI, blue), cell membrane (F-actin stained with RBITC-labeled phalloidin, red). Scale bar, 10 μm. (D) The epithelial barrier penetration ratio of TBY-robots was analyzed by flow cytometry. (E) The process of TBY-robot switching to the macrophage bioengine. Nuclei (DAPI, blue), cell membrane (Dil, red). Scale bar, 10 μm. (F) Subcellular colocalization of TBY-robots in macrophages. Nucleus (Hoechst 33258, blue); lysosome (LysoTracker, red). Scale bar, 10 μm. (G) Fluorescence microscopy images illustrating the intracellular retention of TBY-robotII under normal conditions. (H) Fluorescence microscopy images illustrating Cur (green) release from macrophage under inflammatory conditions at different times. Scale bar, 10 μm. (I and J) Cumulative release of 5-ASA and Cur from macrophages that had endocytosed TBY-robotI or TBY-robotII under normal conditions (I) and inflammatory conditions (J). (K) TBY-robots switched to the macrophage bioengine in Peyer’s patches in situ. Nuclei (DAPI, blue). Microfold cells (DyLight 649–conjugated UEA I, magenta). Macrophages (rhodamine-conjugated anti-F4/80 antibodies, red). TBY-robots fluoresced in green. Arrows, TBY-robot. Scale bar, 20 μm. Data are presented as the means ± SD. n = 5. Two-tailed Student’s t tests. ***P < 0.001.

First, as shown in Fig. 3B, the TBY-robots rapidly penetrated the mucus barrier and reached the epithelial cell layer within 30 min in the presence of 50 mM glucose. Moreover, TBY-robots significantly increased mucus penetration to 14.8-fold higher than that achieved by NPYs. Next, to observe the dynamic penetration of TBY-robots across the intestinal epithelial barrier, we stained the Caco-2 cell membrane (F-actin) with rhodamine B isothiocyanate (RBITC)–labeled phalloidin (red) and stained the cell nuclei with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, blue). The z scans and time-lapse fluorescence images clearly demonstrated that FITC-labeled TBY-robots (green) crossed the epithelial cell barrier by microfold cell transcytosis (adhesion, endocytosis, and exocytosis) (Fig. 3C and movie S5). Furthermore, the percentage of TBY-robots penetrating the epithelial barrier was measured by flow cytometric analysis. After 24 hours of treatment, the percentage of TBY-robots that penetrated the epithelial cell barrier was 39%, a nearly 15-fold increase compared with that of the NPY control (Fig. 3D), indicating that TBY-robots efficiently penetrated the epithelial barrier in the 3D human intestinal model.

Internalization is an effective strategy to fabricate biohybrid autonomous cellular robots (46). To visualize the process by which TBY-robots switched to the macrophage bioengine, we performed cellular immunofluorescence imaging to analyze the endocytosis of TBY-robots by macrophages. TBY-robots were observed to switch rapidly and efficiently to the macrophage engine within 30 min upon binding, trapping, engulfment, and internalization (Fig. 3E). In addition, fluorescence staining with LysoTracker Deep Red indicated that the TBY-robots were trafficked into intracellular lysosomes (Fig. 3F). Considering that dectin-1 is a major β-glucan receptor on macrophages (23) and that β-glucan is the main component of YCs (47), we speculate that the possible mechanism of the TBY-robot switch to the macrophage bioengine is through the dectin-1–mediated pathway. In addition, internalized TBY-robots did not affect the chemotactic motion of the macrophage bioengine toward inflammation (fig. S6). These results demonstrated that TBY-robots are capable of mildly and efficiently switching to the macrophage bioengine.

We further examined how TBY-robots release drugs from macrophages under different physiological conditions. Under normal conditions, we found that TBY-robotsII were maintained in macrophage lysosomes for up to 72 hours (Fig. 3G), which was consistent with previous studies showing that yeast particles remained intact for 3 to 5 days in murine macrophages (27). Meanwhile, the Cur fluorescence displayed a minimal change in the TBY-robots. Next, we analyzed how TBY-robotsII released Cur under lipopolysaccharide (LPS)–stimulated inflammatory conditions using a coculture system similar to that shown in Fig. 3A. LysoTracker fluorescence rapidly increased in the cytoplasm within 30 min, followed by a gradual saturation at 1 hour (Fig. 3H), mainly because of the decrease in intracellular pH in apoptotic macrophages induced by inflammation (fig. S7) (48–50). Moreover, the Cur fluorescence of TBY-robotsII diffused in the cytoplasm from lysosomes after 1 hour of incubation and then rapidly decreased within 2 hours (Fig. 3H).

To verify the exocytosis process of drugs in macrophages, we further analyzed the Cur concentration in the culture supernatant by fluorescence spectroscopy. The Cur concentration increased slowly over time in the culture supernatant and exhibited negligible content within 12 hours, reaching a maximum level after 72 hours under normal conditions (Fig. 3I). In contrast, under inflammatory conditions, the Cur concentration rapidly increased within 2 hours to a higher value than the maximum reached within 72 hours under normal conditions (Fig. 3J). Similar to TBY-robotsII, TBY-robotsI exhibited a negligible difference in the amounts of 5-ASA released (Fig. 3, I and J). These data clearly indicated that TBY-robots rapidly released the packaged drugs from macrophage lysosomes to the cytoplasm and were then exocytosed to the extracellular environment in an inflammation-responsive manner.

On the basis of the above findings, we then explored whether TBY-robots could maintain enzyme bioengine activities and switch to the macrophage bioengine in vivo. The TBY-robots (2 × 107 particles) were orally administered to healthy mice. After 4 hours, the intestinal fluids and Peyer’s patches were collected. The ex vivo results showed that both GOx and Cat maintained their activities and that the TBY-robots still displayed effective propulsion at 4 hours after oral administration in mice (fig. S8 and movie S6). The results may be due to the protection of enteric coating in the stomach and glucose decomposition in the small intestine. Next, the intestinal microfold cells and macrophages in the Peyer’s patches were stained with DyLight 649–labeled Ulex europaeus agglutinin I (UEA I) and RBITC-labeled anti-F4/80 antibodies (red), respectively. The colocalization of fluorescence images demonstrated that the TBY-robots rapidly crossed the intestinal barrier into Peyer’s patches via microfold cell transcytosis and then efficiently switched to the macrophage bioengine (Fig. 3K). These results collectively demonstrated that the TBY-robots maintained their activities and were capable of actively penetrating the intestinal barrier and efficiently switching in situ to the macrophage bioengine.

TBY-robots exhibit inflammation chemotaxis by macrophage relay

We next wanted to determine whether orally administered TBY-robots can home to long-distance inflamed sites in a disease model of ulcerative colitis. Ulcerative colitis is an inflammatory bowel disease that affects the colon and rectum and is associated with high morbidity and decreased quality of life (51). Ulcerative colitis was induced in mice by administering 3% dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) in their drinking water (52). On the third day, the mice were orally administered Cy5.5-labeled TBY-robots (2 × 107 particles), and tissues were collected at different times to analyze their homing process.

The chemotaxis behavior of TBY-robots in Peyer’s patches was examined by flow cytometry. The results showed that the number of Cy5.5-positive macrophages in the TBY-robot group was approximately 5.5-fold higher than that in the NPY controls in Peyer’s patches (Fig. 4, A and B), indicating that the TBY-robots efficiently penetrated the intestinal barrier and entered the Peyer’s patches to switch to the macrophage bioengine. In contrast, the total number of macrophages in the Peyer’s patches was notably decreased at 4 hours after oral gavage with TBY-robots compared to that after gavage with NPYs (Fig. 4, A and C). This result implied that resident macrophages in the Peyer’s patches participated in TBY-robot movement, as the macrophage bioengine carrying TBY-robots emigrated from the Peyer’s patches.

Fig. 4. TBY-robots are driven by macrophage bioengine relay delivery to inflamed sites.

Colitis was induced by administering 3% DSS to mice in their drinking water. On the third day, Cy5.5-labeled TBY-robots were orally administered to mice. (A to C) Flow cytometry plots (A) and positive ratio (B) of TBY-robots internalized by macrophages and total populations of macrophages (C) in Peyer’s patches at 4 hours after treatment (n = 3). (D and E) Ex vivo fluorescence imaging (D) and fluorescence intensity (E) of Peyer’s patches, MLNs, and spleen at different time points after oral delivery of TBY-robots (n = 3). (F) Fluorescence intensity of macrophages at different time points after laminarin pretreatment to block microfold cells. (G and H) Fluorescence imaging (G) and fluorescence intensity (H) of macrophages in blood and inflamed colon tissue were examined at different times. (I) Fluorescence intensity of macrophages in blood and inflamed colon tissue examined at different points after removing the spleen. (J) Schematic illustration showing the process of TBY-robot migration and transmigration (Peyer’s patch–MLN–spleen–blood) and inflammation targeting. TBY-robots rapidly reached the mucus barrier within 2 min by directional chemotactic motion (Fig. 2, K to M) and then penetrated the mucus barrier within 30 min (Fig. 3B). Thus, TBY-robots navigate to the GI tract wall within 32 min and then switched to the macrophage engine within 1 hour (Fig. 3, E and F). TBY-robots continuously deliver drugs to the inflamed sites through lymph and blood circulation within 24 hours (Fig. 4). nd, not detected. Data are presented as the means ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s post hoc test (C) or an unpaired two-tailed Student t test (B, E, F, and H). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

To determine TBY-robot chemotaxis, we next analyzed the migration route of macrophage bioengine relay delivery in the lymphatic and blood circulation systems. The intestinal lymph tissues, including Peyer’s patches, mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs), and spleen, were collected and imaged with an in vivo imaging system at 6, 12, and 24 hours after the oral administration of NPYs or TBY-robots. Ex vivo imaging revealed that the fluorescence signal of the TBY-robots in the Peyer’s patches decreased rapidly over time. In contrast, the Cy5.5 fluorescence signal in the spleen increased rapidly and peaked at 12 hours after treatment, and the level of fluorescence was calculated to be approximately 3.8-fold higher than that of NPYs at 12 hours (Fig. 4, D and E). Moreover, the MLNs had a minimal fluorescence signal compared with the Peyer’s patches and spleen (Fig. 4, D and E). These results revealed that the macrophages carrying TBY-robots did not reside within the MLNs, possibly because the MLNs act as a firewall to quickly select immune cells to enter the lymphatic ducts and systemic circulation (53). To further investigate whether the TBY-robots migrated to the spleen via the lymphatic circulation, the mouse was pretreated by oral gavage with laminarin (competitive binding microfold cell) for 1 hour before TBY-robot administration. The fluorescence signal in the Peyer’s patches and MLNs was 100-fold lower than that without laminarin pretreatment (Fig. 4F and fig. S9A). These results demonstrated that TBY-robots, through microfold cell transcytosis into intestinal lymph tissues, rapidly transmigrated to the spleen via lymphatic circulation.

Subsequently, macrophages were separately isolated from the blood and inflamed colon tissues and examined using an in vivo imaging system at different times. Ex vivo imaging of macrophages revealed that the fluorescence signals in the blood decreased gradually, while a relatively stable fluorescence signal remained in the inflamed colon tissues over time after TBY-robot administration. Blood macrophages exhibited minimal fluorescence signals 24 hours after oral gavage with TBY-robots compared to those in colon tissues (Fig. 4, G and H). Splenic macrophages have been reported to be exclusively involved in the regulation of inflammation (54); thus, we further investigated the role of the spleen in TBY-robot chemotaxis. After the mouse spleen was removed, the fluorescence signal in macrophages in the blood and inflamed colon tissue was markedly decreased and could not be detected at 24 hours (Fig. 4I and fig. S9B). This result is also in line with the fact that the spleen serves as a storage reservoir for macrophages and enables them to rapidly mobilize to inflamed sites without staying in the blood for a long time (54). These data clearly demonstrated that TBY-robots transmigrated from the spleen and rapidly homed to inflamed sites through the blood circulation.

Collectively, these observations implied that the TBY-robots were capable of efficient chemotactic motion and homing to inflamed sites by macrophage bioengine relay delivery. The route of chemotactic motion is described in Fig. 4J. TBY-robots are first transported via microfold cell transcytosis into Peyer’s patches for in situ switching to the macrophage bioengine. Sequentially, the TBY-robot underwent macrophage relay delivery to the MLNs, then translocated to the spleen via the lymphoid circulation, and lastly traveled through the blood circulation to home to the inflamed sites.

TBY-robots enhance intestinal retention and inflammation targeting

After EMS delivery, the intestinal retention and inflammation targeting efficiency of TBY-robots were further evaluated in vivo using the colitis mouse model. After the oral administration of 3% DSS for 3 days, bioluminescent imaging of the intestinal tract with the luminol-based chemiluminescent probe L-012 confirmed that a strong inflammatory signal was specifically localized in the colon (Fig. 5, A and B). Given that the transit time of microparticles in the GI tract is approximately 5 hours in mice (55), we started to analyze the intestinal retention of the TBY-robots at 6 hours after oral administration. At 6 hours after oral gavage with TBY-robots (modified with a Cy5.5 fluorophore), a significantly enhanced fluorescence signal that was 15-fold higher than that of NPYs was detected in the small intestine (Fig. 5, C and D), reflecting attractive chemotaxis driven by enzymes and efficient retention in the small intestine. Immunofluorescent staining of the Peyer’s patches of the different small intestine regions further showed that most TBY-robots penetrated the jejunum mucus layer (fig. S10). Next, we monitored the long-term intestinal retention of TBY-robots using an in vivo imaging system. The TBY-robots showed a detectable signal for up to 24 hours in the small intestine, which was approximately fivefold longer than the typical GI emptying time in the mouse GI tract. In addition, mice were pretreated with laminarin to competitively bind microfold cells, and the fluorescence signal of TBY-robots was not detected in the small intestine at 24 hours after GI emptying (fig. S11). These results demonstrated that the TBY-robots actively penetrated the intestinal barrier by using the enzyme-driven engine and significantly enhanced their intestinal retention efficiency and retention time in the small intestine.

Fig. 5. TBY-robots efficiently enhanced intestinal retention and inflammation targeting.

Colitis was induced by administering 3% DSS to mice in their drinking water. (A and B) Ex vivo bioluminescence images (A) of the GI tract and analysis (B) by an in vivo imaging system. (C and D) Fluorescence imaging of the GI tract (C) and fluorescence intensity quantification (D) 6, 12, and 24 hours after oral delivery of NPYs or TBY-robots. Each bar represents the means ± SD; n = 3. Statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired two-tailed Student t test. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

Simultaneously, the TBY-robots displayed a maximal fluorescence signal in the inflamed colon compared with the stomach and small intestine from 6 to 24 hours (Fig. 5C), suggesting that the TBY-robots were capable of actively homing to inflamed colon tissue after oral administration. Moreover, the difference in the fluorescence signal of TBY-robots and NPYs in the colon gradually increased over time, and it reached the highest difference of 10-fold at 24 hours (Fig. 5D). Conversely, when the mouse spleen was removed, the fluorescence signal of the TBY-robots in the inflamed colon could not be detected after 24 hours (fig. S11), suggesting that the TBY-robots homed to the inflamed site by macrophage relay delivery. Moreover, immunofluorescence imaging of TBY-robots colocalized with macrophages further confirmed that TBY-robots specifically accumulated in the colonic inflamed site by the action of the macrophage bioengine (fig. S12). Collectively, these data clearly verified that TBY-robots were capable of actively penetrating the intestinal barrier for enhanced intestinal retention by using an enzyme-driven engine and that their inflammation targeting was markedly enhanced by chemotaxis-guided macrophage relay delivery.

Orally administered TBY-robots ameliorate colitis

Next, we tested the potential therapeutic utility of TBY-robotI in mice with DSS-induced colitis. Enteric-coated TBY-robotsI were orally administered on days 3, 5, and 7 after DSS administration, and colitis severity was assessed on day 8 (Fig. 6A).

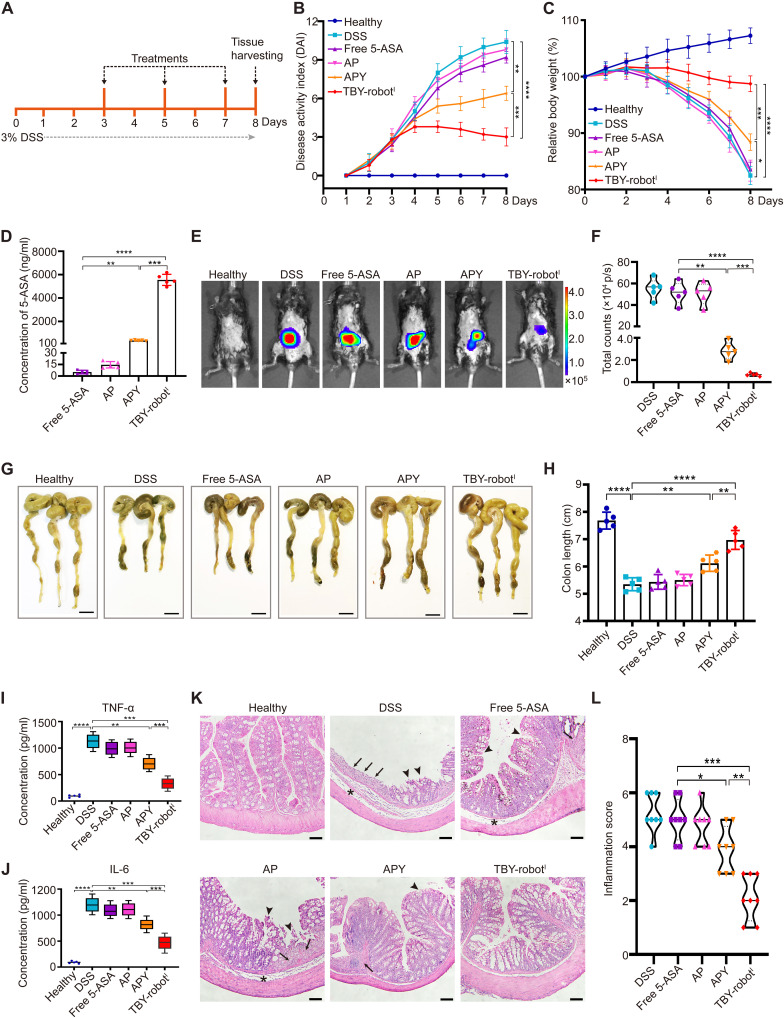

Fig. 6. Orally administered TBY-robots effectively attenuated DSS-induced colitis in mice.

(A) After 3% DSS was administered, mice were orally administered free 5-ASA, APs, AP-loaded yeast microcapsules (APYs), and TBY-robotsI on days 3, 5, and 7 and then euthanized to evaluate the therapeutic effect. (B and C) The DAI (B) and body weight (C) were measured daily after the different treatments (n = 5). (D) The concentration of 5-ASA in the colon after three treatments. (E and F) Bioluminescent images (E) and fluorescent quantification (F) of the levels of inflammation in colitis mice using an in vivo imaging system. (G and H) Gross morphological changes in the colon (G) and colon length (H) were evaluated. (I and J) TNF-α levels (I) and IL-6 levels (J) in whole-tissue lysates were assessed by ELISA (n = 5). (K and L) Representative H&E-stained sections of colons (K) and inflammation scores (L) are shown. Arrows, areas of strong transmural inflammation with loss of crypt structure and goblet cells; arrowheads, ulceration; asterisks, neutrophilic infiltrates and transmural inflammation. Scale bar, 100 μm. Significance displays were measured using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001.

Oral gavage with TBY-robotsI significantly protected against the DSS-induced increase in disease activity index (DAI) score and body weight loss (Fig. 6, B and C). Mouse colons were collected on day 8, and quantitative analysis of the 5-ASA concentration in the colon showed that the TBY-robots increased drug accumulation by 998-fold compared to free 5-ASA and by 13.2-fold compared with AP-loaded yeast microcapsules (APYs) (Fig. 6D). We then used the luminol-based chemiluminescent probe L-012 to evaluate the level of inflammation in vivo by using an in vivo imaging system. The in vivo images showed a strong chemiluminescence signal in the colon area in the free 5-ASA and AP groups, and it was not significantly different from that in the control group of DSS-treated mice (Fig. 6, E and F). In contrast, colitis mice that were treated with APYs exhibited only moderate anti-inflammatory effects, whereas TBY-robotI treatment resulted in the strongest protection against colonic inflammation (Fig. 6E). Analysis of L-012 chemiluminescence intensity confirmed that the luminescent signal obtained with TBY-robotI administration was approximately 4.1-fold lower than that with APY administration and more than 74.3-fold lower than that with the other treatments (Fig. 6F). Moreover, direct measurement of colon length showed that compared with the mice in the other treatment groups, mice treated with TBY-robotsI were significantly protected from DSS-induced colon shortening (Fig. 6, G and H).

To further assess the effects of the different treatments on inflammation severity, we analyzed the proinflammatory cytokine levels in colon tissues by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Colonic tumor necrosis factor–α (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels, whose elevation is a hallmark of colitis, were drastically reduced after three rounds of oral delivery of TBY-robotsI compared to those in other treatment groups (Fig. 6, I and J). In addition, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of colonic sections showed that DSS-induced colitis caused notable damage to the colon structure, with epithelial disruption, goblet cell depletion, and substantial leukocyte infiltration. While APYs slightly attenuated colonic injury, TBY-robotI treatment efficiently cured colitis, as shown by the nearly normal histological microstructure and reduced inflammation scores (Fig. 6, K and L). Together, these results suggest that TBY-robots efficiently deliver 5-ASA to inflamed intestinal sites, significantly ameliorating inflammation and pathological damage in colitis, and could serve as a reliable therapeutic strategy for colitis.

Orally administered TBY-robots ameliorate gastric ulcers

The therapeutic applications of TBY-robots were further tested in an aspirin-induced chronic gastritis model. Here, gastric ulcers were induced in mice by the oral administration of aspirin (100 mg/kg) in the water supply for 10 days (56). Enteric-coated TBY-robotsII were orally delivered every other day starting on day 3, and the stomachs of the mice were collected to evaluate mucosal damage on day 10 (Fig. 7A). Quantitative analysis of the Cur concentration in the stomach showed that TBY-robotsII increased Cur accumulation at the inflamed site by approximately 1000-fold compared to that obtained with free Cur administration and by 14.6-fold compared to that with CP-loaded yeast microcapsule (CPY) administration (Fig. 7B). Ex vivo fluorescence imaging and immunofluorescence analysis further revealed that TBY-robots efficiently targeted gastric ulcers and colocalized with macrophages (fig. S13), confirming that the TBY-robots were indeed driven by macrophage bioengines and through macrophage relay to target inflamed sites. The L-012 chemiluminescence signals revealed aspirin-induced severe gastric ulcers in the stomach. The mice that were treated with CPYs exhibited only moderate anti-inflammatory effects, whereas TBY-robotII treatment produced the most prominent protection against gastric ulcers (Fig. 7, C and D).

Fig. 7. Orally administered TBY-robots effectively attenuated gastric ulcer development in mice.

(A) Gastric ulcer development was induced using aspirin (100 mg/kg) in CD-1 mice (n = 5). Mice were treated with free Cur, CPs, CPYs, or TBY-robotsII on days 3, 5, 7, and 9 and euthanized to evaluate therapeutic efficiency on day 10. (B) The concentration of Cur in the stomach after four treatments. (C and D) Representative bioluminescence images (C) of inflamed gastric sites and signal quantification (D) (n = 5). (E and F) Gastric TNF-α (E) and IL-6 (F) levels in whole-stomach tissue lysates were evaluated by ELISA. Data are presented as the means ± SD; n = 5. (G and H) Representative H&E-stained sections of stomachs (G) and inflammation scores (H) are shown. Arrows, gastric glands are markedly dilated with distorted architecture; arrowheads, epithelial ulceration; asterisks, transmural inflammation and neutrophilic infiltrates. Scale bar, 100 μm. (I) Immunofluorescence staining for assessing neovascularization. TBY-robotsII effectively enhanced gastric mucosal cell proliferation. Immunostaining for endothelial cells (anti–CD31-FITC, green), α-SMA (red), and nuclei (DAPI, blue) of gastric ulcer sections. Scale bar, 50 μm. Significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001.

Moreover, TBY-robotsII drastically reduced the levels of important proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α and IL-6 (Fig. 7, E and F). Pathologically, aspirin leads to severe gastric lesions in the form of gland dilation, distortion, erosion, and transmural inflammation (56). All of these gastric ulcer signs were significantly and markedly reduced in TBY-robotII–treated mice, as assessed by histology and inflammation scores (Fig. 7, G and H).

The therapeutic efficacy of TBY-robotsII for gastric ulcer healing was also assessed by immunofluorescence. Double immunofluorescence staining against CD31 (an endothelial cell marker) and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) was performed to analyze neovascularization, and the results showed a significant increase in the densities of capillaries and small arteries in inflamed sites in the group administered TBY-robotsII compared with those in the other treatment groups (Fig. 7I). This result further indicated that TBY-robotsII markedly decreased inflammation to promote gastric ulcer healing. Together, these findings demonstrated that TBY-robots efficiently delivered Cur to inflamed sites in the stomach and achieved desirable efficacy in the treatment of gastric ulcers in mice.

We also evaluated the safety of TBY-robots in vivo. Experiments assessing the effects of treatment on blood biochemistry parameters indicated that mice treated with TBY-robot markedly decreased cationic NP toxicity in the liver, kidney, and blood and had similar profiles to those in mice administered PBS (fig. S14, A to C). H&E staining of the stomach and small intestinal tissues showed that TBY-robots had minimal impact on their histologic structures (fig. S14D). Together, these results indicated that TBY-robot displayed a good safety profile for the treatment of GI inflammation.

DISCUSSION

Micro/nanorobots play a vital role in active targeted drug therapy for precision medicine (57). However, single-engine–driven robots cannot adjust their driving mechanisms to achieve continuous and directional propulsion forces that can overcome biological barriers and achieve long-distance delivery in vivo. We aimed to develop a self-adaptive micro/nanorobot to overcome multiple biological barriers and achieve active and accurate drug delivery for GI inflammation therapy. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a TBY-robot with enzyme actuation and macrophage relay, which can autonomously respond to changes in the microenvironment to cross multiple biological barriers and autonomously navigate to long-distance and deep-seated inflamed sites. Asymmetric immobilized enzyme bioengines enable the TBY-robot to achieve a driving force toward higher glucose concentrations over time scales of minutes and length scales 105 times longer than their own size. Moreover, TBY-robots are capable of chemotactic motion to enhance intestinal retention and effectively cross the intestinal epithelial barrier.

The TBY-robots actively penetrate the intestinal mucus by enzymatic driving and then enter the Peyer’s patches via microfold cell transcytosis to switch to the macrophage engine. Subsequently, TBY-robots can autonomously migrate to inflamed GI sites through macrophage chemotaxis–guided relay delivery. This twin-bioengine delivery strategy is a sequence-driven process through EMS with Peyer’s patches as transfer stations, which can precisely transport therapeutics across multiple biological barriers to long-distance, deep-seated diseased sites. The transport route is similar to that of the Express Mail Service in precisely delivering the parcels to a distant destination by different transportation facilities (Fig. 8). Self-adaptive TBY-robots can respond to complex environmental changes through chemical chemotaxis in the intestinal tract and biological chemotaxis in the circulatory system.

Fig. 8. EMS delivery of TBY-robots for long-distance transport across multiple biological barriers.

EMS is similar to that of the Express Mail Service in precisely delivering parcels to a distant destination by different transportation facilities.

Notably, the EMS strategy is essential for TBY-robots to perform the active and targeted delivery of anti-inflammatory drugs to inflamed sites in the GI tract. First, glucose concentration gradients exist only in the small intestine, where the digestion and absorption of glucose occurs (34), while both the colon and stomach lack a glucose power source. Thus, these microrobots cannot directly reach inflamed sites in the colon and stomach by using a single-enzyme bioengine. Second, the enteric coating of TBY-robots avoids enzyme bioengine inactivation and prevents drug leakage into gastric fluids, and they also cannot directly release drugs in the alkaline colonic environment simultaneously. On the other hand, the blockade of microfold cell transcytosis and spleen removal further confirmed the lymphatic-blood transport route of the microrobots. As a result, the TBY-robots increased drug accumulation at the diseased GI sites by approximately 1000-fold compared with that of the free drug, markedly attenuating inflammation and ameliorating disease pathology in colitis and gastric ulcer mouse models. Moreover, macrophage-mediated chemotaxis is closely related to various inflammatory diseases, including infectious diseases, neurodegenerative diseases, arthritis, atherosclerosis, diabetes, obesity, pancreatitis, and cancer (58–61). We envision that the self-adaptive TBY-robot can cross multiple biological barriers and achieve precision drug therapy of these inflammatory diseases through a long-distance EMS delivery strategy.

In summary, TBY-robots are endowed with enzyme actuation and macrophage relay characteristics, especially EMS capability, enabling them to undergo self-adaptive changes in the complex environment of the GI tract, lymph, and blood to cross multiple biological barriers and navigate to long-distance, deep-seated inflamed sites. These EMS-based TBY-robots represent a safe and versatile delivery vehicle for the treatment of GI inflammation and other inflammatory diseases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Baker’s yeast (S. cerevisiae) was provided by Lesaffre Management Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). GOx (100 to 250 U/mg) from Aspergillus niger, Cat (2000 to 5000 U/mg) from bovine liver, branched polyethyleneimine (bPEI, molecular weight = 25 kDa), FITC, glucose and CDI, PMA, 5-ASA, Cur, laminarin, and LPS were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Missouri, USA). l-α-distearoyl-phosphatidylcholine (DSPC), cholesterol, and 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[amino (polyethylene glycol)-2000] (DSPE-PEG2000-NH2) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabama, USA). Sulfo-Cy5.5 N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) ester was purchased from Lumiprobe (Maryland, USA). A bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit, Amplex Red GOx assay kit, and Amplex Red Cat assay kit were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, USA). Acrylic polymers (Eudragit L, 100-55) were purchased from Evonik Industries (Hanau, Germany). Caco-2 cells, Raji cells, and THP-1 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, USA). The cell culture reagents were obtained from Gibco (Grand Island, USA). All other chemicals and reagents used were of analytical grade.

Preparation of Cy5.5-labeled GOx and FITC-labeled Cat

GOx was first dissolved in PBS at 1 mg/ml, and Cy5.5 NHS ester (1 mM) was added. Two milligrams of Cat was dissolved in 1 ml of sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3) buffer, and 70 μg of FITC was added. The solution was shaken for 6 hours. Cy5.5-labeled GOx or FITC-labeled Cat was purified with PBS through a 100-kDa filter (Millipore, USA) with centrifugation at 2000g for 5 min. The resulting Cy5.5-GOx or FITC-Cat was dispersed in PBS and stored at 4°C until use.

Preparation of YCs

Hollow YCs were purified from baker’s yeast through alkaline and acid extraction methods (26). Briefly, baker’s yeast was dissolved in 1 M sodium hydroxide (NaOH), and the solution was heated at 80°C for 1 hour. After centrifugation at 3000g for 10 min, the pellet was rinsed twice with deionized water. Then, the sample was dispersed in hydrochloric acid (HCl) solution at pH 4.0 and incubated at 60°C for 1 hour. Subsequently, the obtained sample was rinsed with isopropyl alcohol and acetone, and the YCs were collected and dried at room temperature.

Preparation of cationic NPs

CPs were prepared according to the previously described self-assembly method (62). In brief, Cur and bPEI were dissolved in anhydrous dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at a weight ratio of 1:2, with a bPEI concentration of 10 mg/ml, and the resulting solution was dialyzed against deionized water for 24 hours. The Cur content in the NPs was determined by fluorescence spectroscopy (F900, Edinburgh Instruments Ltd., UK) with excitation at 488 nm and emission at 535 nm.

To prepare Cy5.5-labeled cationic NPs, three Cy5.5 units were conjugated onto bPEI by reaction with Sulfo-Cy5.5 NHS ester. Cationic liposomes loaded with 5-ASA (AP) were prepared according to the conventional thin-film hydration method (63). Briefly, lipids, DSPC, cholesterol, and DSPE-PEG-NH2 (5:4:0.3 molar ratio) were dissolved in 7 ml of trichloromethane:methanol (5:2, v/v), and the solvent was removed via rotary-vacuum evaporation (37°C, 15 min) to form a thin film. The film was then hydrated with an aqueous solution containing 5-ASA (1 mg/ml) in PBS. The resulting dispersion was extruded using a polycarbonate membrane (100-nm pore size; Millipore, USA), and the suspension was lastly subjected to dialysis against saline to remove nonencapsulated 5-ASA. The 5-ASA content in NPs was determined by ultraviolet (UV) spectrophotometry at 330 nm (Lambda 35, PerkinElmer, USA).

Fabrication of NPYs

NPYs were prepared by electrostatic force–driven self-deposition (27). First, 100 mg of YC was incubated with 10 ml of carbonate buffer solution at 37°C for 1 hour, and then different ratios of CPs (CP/YC ranging from 0.1 to 9 w/w) were added to the buffered YC suspension and incubated for 4 hours at 37°C. The resulting CP-packaged YC was collected by centrifugation at 3000g for 10 min and thoroughly washed with deionized water to remove unpackaged NPs. Then, the CPYs were obtained by lyophilization. The optimal CP/YC ratio was determined by flow cytometry (Beckman Coulter, UK). The Cur encapsulation efficiency and loading content were determined by quantification of unpackaged CPs by fluorescence spectrometry (F900, Edinburgh Instruments Ltd., UK) with excitation at 488 nm and emission at 535 nm. The same procedures at the same optimal ratio were used to fabricate the APYs and Cy5.5-labeled NPYs. The 5-ASA encapsulation efficiency and loading content in APYs were determined by UV spectrophotometry at 330 nm (Lambda 35, PerkinElmer, USA).

Preparation of TBY-robots

First, 10 mg of NPYs and 100 μl of glycerol were resuspended in deionized water. To mask half the surface of the NPYs, the suspension was poured onto a 15-cm glass petri dish and dried at 60°C in a hot-air oven for 2 hours. After drying, the dish was washed with deionized water to remove unattached NPYs. Afterward, the ─OH of the attached NPYs was allowed to react with CDI (0.3 M) in anhydrous DMSO for 2 hours. Three washes with deionized water were needed to remove excess agents, and the partially surface-activated NPYs were disassociated from the glass petri dish, followed by two deionized water washes. Last, the partially surface-active NPYs were suspended in a solution containing GOx (3 mg/ml) and Cat (1 mg/ml) overnight at 4°C and washed with deionized water. For oral delivery, the TBY-robots were coated with a commercial enteric polymer by a controlled emulsion technique, as described in previous reports (16).

Morphology of the TBY-robots

SEM images of the TBY-robots were obtained with a SUPRA55 instrument (Zeiss, Germany). EDS mapping analysis was performed using an Oxford EDS detector attached to the SEM instrument. TEM images were captured using a JEM-1400Plus microscope (JEOL, Japan). The Janus coating of GOx and Cat onto YCs was characterized by fluorescent imaging of Cy5.5 and FITC. All bright-field, fluorescence, and merged images were captured using a SpinSR10 confocal microscope (Olympus, Japan).

The immobilized enzyme amount was determined by the commercial BCA protein quantitation assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The remaining enzymatic activity of GOx and Cat was evaluated by the Amplex Red assay.

In vitro drug release study

The drug release profiles from TBY-robots were assessed in simulated gastric fluid at pH 1.2 and simulated intestinal fluid at pH 7.4 with the addition of 0.2% Triton X-100 as a surfactant. The Cur concentrations in the buffer were quantified by fluorescence spectrometry. The 5-ASA concentrations were quantified by UV spectrophotometry.

Propulsion analysis

All experiments were performed in aqueous solution by mixing TBY-robots with glucose solution at the desired concentrations. A cover slide was applied to prevent drifting. The motion of the TBY-robot was observed by using an inverted optical microscope (EVOS M7000, Invitrogen, USA) with a 40× microscope objective. Accurate tracking of the TBY-robot was accomplished by using the Fiji plugin TrackMate and analyzed using Origin 8.0. The MSD was calculated as follows (9)

| (2) |

After this, Deff was obtained by fitting the MSD curves to Eq. 3

| (3) |

where Deff represents the effective diffusion coefficient and Δt represents the time interval.

Chemotactic motion of TBY-robots

The accumulation motion of the TBY-robots was visualized by using a soaked glucose agarose gel to create a gradient of glucose in a petri dish. First, a cylindrical agarose gel presoaked in 1 M glucose solution was placed on the edge of a petri dish (diameter, 34.8 cm) filled with PBS. Afterward, 100 μl of FITC-labeled TBY-robot or FITC-labeled NPY was added to the center of the dish. Images of the samples were collected at different time points by fluorescence microscopy (Olympus, Japan). A previously proposed model (10) was used to simulate the chemotactic motion of TBY-robots. The motion and heatmap of the TBY-robot concentration were simulated by COMSOL Multiphysics software. The simulation parameters are listed in table S1.

The microfluidic channel was filled with PBS solution. Then, 300 and 0.2 mM glucose agarose gels were placed on each side of the channel. After 5 min, 20 μl of PBS solution with TBY-robots was added to the channel. Then, the chemotaxis of the TBY-robots was observed under an Olympus IX71 inverted microscope. Accurate tracking of the TBY-robot was accomplished by using the Fiji plugin TrackMate and analyzed using Origin 8.0.

Human 3D intestinal model

The human 3D intestinal model was obtained by adapting the existing M-cell–like model (44) and intestinal mucus model (45). Briefly, Transwell inserts (Corning Costar) were coated with Matrigel (10 μl/ml of medium; BD Bioscience, CA) and placed at room temperature for 1 hour. The supernatants were then removed, and the inserts were washed with RPMI 1640 medium. Caco-2 cells (5 × 105) were seeded on the upper insert side and cultivated for 16 days. Afterward, Raji cells (2.5 × 105) were added to the basolateral insert compartment and maintained for 5 days to convert Caco-2 cells to M cells. Human macrophages differentiated from PMA (100 ng/ml)–stimulated THP-1 cells were cultivated at the bottom of the Transwell. On day 21, 20 μl of biosimilar mucus was placed on a Caco-2 cell monolayer 5 min before adding 300 μl of complete RPMI 1640 (containing 50 mM glucose) medium to the insert. FITC-labeled TBY-robots or FITC-labeled NPYs (both 2 × 106 particles/ml) were added to the insert, and the system was cultured for 24 hours. The cells were examined by confocal laser scanning microscopy (Leica, TCS SP8, Germany). The time-lapse 3D images of the penetration of TBY-robots across the intestinal epithelial barrier were observed with a widefield and confocal imaging system (Mica, Leica, Germany).

To analyze how TBY-robotsII release Cur under inflammatory conditions, we used a coculture system similar to that shown in Fig. 3A. TBY-robotII–endocytosed macrophages were first seeded into the bottom of the Transwell plates. Caco-2 cells were seeded into the upper chambers, pretreated with LPS (10 μg/ml) for 4 hours to induce an inflammatory condition, added to the Transwell system, and cocultured with TBY-robotII–endocytosed macrophages for different times. As indicated above, these TBY-robotII–endocytosed macrophages were imaged by confocal microscopy. Moreover, the Cur concentration of the cell culture supernatant was analyzed by fluorescence spectrometry.

The in situ switching of the TBY-robots to the macrophage bioengine in the Peyer’s patches was examined by immunofluorescence. Microfold cells were stained with DyLight 649–conjugated UEA I (Vector Laboratories, USA), macrophages were stained with RBITC-conjugated F4/80 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), and nuclei were stained with DAPI and examined by confocal microscopy.

Animal studies

C57BL/6 female mice and CD-1 male mice (6 to 8 weeks of age) were obtained from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co. Ltd. (Beijing, China). Mice were placed in suitable cages and acclimatized to laboratory conditions for 1 week before starting the experiments. All mouse experiments were carried out in accordance with the Guide Protocol of Laboratory Animals (SIAT-IACUC-190220-YYS-ZBZ-A0598) and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Shenzhen Institute of Advanced Technology, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

TBY-robot switching to macrophage bioengines and targeting inflammation

Colitis was induced by feeding C57BL/6 female mice 3% (w/v) DSS (MP Biomedicals) dissolved in drinking water continuously for 7 days (52). On day 3, mice were randomly assigned to three groups (n = 3). The control group was orally administered 0.2 ml of saline, while the other two groups were orally administered 0.2 ml of Cy5.5-labeled TBY-robots or Cy5.5-labeled NPYs (equivalent of 2 × 107 particles per mouse). At 6, 12, and 24 hours after treatment, the mice were euthanized, and the organs (Peyer’s patches, MLNs, spleen, and GI tract) were excised for ex vivo fluorescence imaging by using an in vivo imaging system (IVIS Spectrum, PerkinElmer, CA).

The procedure of macrophage isolation from the MLNs, spleen, blood, and colon after digestion and density gradient centrifugation was described previously (64). Briefly, digestion of the tissue was performed using cell dissociation buffer (Gibco, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After centrifugation of the digested tissue, the supernatant was discarded carefully, and the pellet was resuspended in 5 ml of 40% Percoll (GE Healthcare, USA). This suspension was carefully loaded on 5 ml of 80% Percoll in a 15 ml-tube, creating a 40 to 80% gradient with a sharp border. Interphase-containing macrophages were harvested. The macrophage isolation from the Peyer’s patches was analyzed by flow cytometry (Beckman Coulter, UK). Macrophage isolation from the blood, spleen, and colon was examined by an in vivo imaging system.

To further investigate whether TBY-robots transmigrate to the spleen through the lymphatic circulation, mice were pretreated by oral gavage with laminarin (150 mg/kg) for 1 hour before TBY-robot administration to inhibit robot entry into the lymphatic circulation. To investigate the role of the spleen in TBY-robot chemotaxis, the mouse spleen was removed under isoflurane anesthesia after an incision was made on the left side of the abdomen. After 1 week, colitis was induced in the splenectomized mice by 3% DSS. The aforementioned procedures were adopted to evaluate the role of the spleen in TBY-robot chemotaxis.

Colitis treatment

Colitis was induced by administering 3% (w/v) DSS in drinking water for 7 days. Healthy animals received drinking water without DSS. All colitis group mice were randomly divided into four groups on day 3 (n = 5) and orally administered deionized water, free 5-ASA, APs, APYs, or enteric-coated TBY-robotsI (10 mg/kg 5-ASA equivalent per mouse) every other day. Mice were evaluated daily for changes in body weight and DAI (52). On day 8, mice were intraperitoneally injected with L-012 solution (25 mg/kg; Wako Chemicals, Japan). Bioluminescence images were obtained using an in vivo imaging system. Thereafter, the colon was removed and flushed with PBS. Colon length and colon weight were measured. Small segments of the colon were taken for H&E staining. The H&E–stained sections were scored blindly using index scoring (52). Colon samples were homogenized to assess 5-ASA content by a high-performance liquid chromatography system (Shimadzu, Japan). The detection wavelength was 330 nm, and the injection volume was 10 μl for each sample. Moreover, the cytokines in the colon tissues were examined by TNF-α and IL-6 ELISA kits (BioLegend, USA).

Gastric ulcer treatment

Gastric ulcers were induced by the oral administration of aspirin (100 mg/kg; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) per day for 10 days in CD-1 mice. On day 3, mice were orally administered deionized water, Cy5.5-labeled NPY, or Cy5.5-labeled enteric-coated TBY-robots (n = 3). After 48 hours, the stomach was collected and imaged with an in vivo imaging system. Stomach sections were stained with FITC-labeled CD68 and DAPI and examined by confocal microscopy.

For the treatment of gastric ulcers, on day 3, mice were randomly divided into four groups (n = 5) and orally administered deionized water, free Cur, CPs, CPYs, or enteric-coated TBY-robotsII (10 mg/kg Cur equivalent per mouse) every other day. On day 10, mice were intraperitoneally injected with L-012 solution (25 mg/kg), the stomachs were harvested after 10 min, and bioluminescent images were obtained using an in vivo imaging system. Afterward, small segments of the stomach were taken for H&E staining and immunohistochemistry evaluation. The H&E sections were scored blindly using index scoring (65). The stomachs were stained with FITC-labeled CD31, RBITC-labeled α-SMA, and DAPI to analyze cell proliferation. Stomach samples were homogenized to assess Cur content by fluorescence spectroscopy (F900, Edinburgh Instruments Ltd., UK). The cytokines in stomach tissue were examined by TNF-α, IL-6, and ELISA kits (BioLegend, USA).

Statistics analysis

All results are presented as the means ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (v.8.0). The significance between the two groups was analyzed by an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. For multiple comparisons, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s post hoc test was used. P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81971749), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2019YFE0198700 and 2022YFC2402400), the Guangdong Provincial Key Area R&D Program (2020B1111540001), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2022A1515010780), and the Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (JCYJ20200109114616534 and JCYJ20210324101807020).

Author contributions: L.C., B.Z., M.Z., and H.P. conceived the study and designed the experiments. B.Z., Z.C., and T.Y. performed the experiments and collected the data. All the authors contributed to writing the manuscript, discussing the results and implications, and editing the manuscript at all stages.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Supplementary Text

Figs. S1 to S14

Table S1

Legends for movies S1 to S6

Other Supplementary Material for this : manuscript includes the following:

Movies S1 to S6

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.S. M. Brierley, D. R. Linden, Neuroplasticity and dysfunction after gastrointestinal inflammation. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 11, 611–627 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.W. Jia, G. Xie, W. Jia, Bile acid-microbiota crosstalk in gastrointestinal inflammation and carcinogenesis. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 15, 111–128 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.S. Zhang, R. Langer, G. Traverso, Nanoparticulate drug delivery systems targeting inflammation for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Nano Today 16, 82–96 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.J. Li, B. Esteban-Fernández de Ávila, W. Gao, L. Zhang, J. Wang, Micro/nanorobots for biomedicine: Delivery, surgery, sensing, and detoxification. Sci. Robot. 2, eaam6431 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.S. Palagi, P. Fischer, Bioinspired microrobots, Nat. Rev. Mater. 3, 113–124 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 6.M. Fernández-Medina, M. A. Ramos-Docampo, O. Hovorka, V. Salgueiriño, B. Städler, Recent advances in nano- and micromotors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1908283 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 7.G. Salinas, S. M. Beladi-Mousavi, A. Kuhn, Recent progress in enzyme-driven micro/nanoswimmers: From fundamentals to potential applications. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 32, 100887 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 8.A. C. Hortelao, C. Simó, M. Guix, S. Guallar-Garrido, E. Julián, D. Vilela, L. Rejc, P. Ramos-Cabrer, U. Cossío, V. Gómez-Vallejo, T. Patiño, J. Llop, S. Sánchez, Swarming behavior and in vivo monitoring of enzymatic nanomotors within the bladder. Sci. Robot. 6, eabd2823 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.S. Tang, F. Zhang, H. Gong, F. Wei, J. Zhuang, E. Karshalev, B. Esteban-Fernández de Ávila, C. Huang, Z. Zhou, Z. Li, L. Yin, H. Dong, R. H. Fang, X. Zhang, L. Zhang, J. Wang, Enzyme-powered Janus platelet cell robots for active and targeted drug delivery. Sci. Robot. 5, eaba6137 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.A. Joseph, C. Contini, D. Cecchin, S. Nyberg, L. Ruiz-Perez, J. Gaitzsch, G. Fullstone, X. Tian, J. Azizi, J. Preston, G. Volpe, G. Battaglia, Chemotactic synthetic vesicles: Design and applications in blood-brain barrier crossing. Sci. Adv. 3, e1700362 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.H. Zhang, Z. Li, C. Gao, X. Fan, Y. Pang, T. Li, Z. Wu, H. Xie, Q. He, Dual-responsive biohybrid neutrobots for active target delivery. Sci. Robot. 6, eaaz9519 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.B. Esteban-Fernández de Ávila, W. Gao, E. Karshalev, L. Zhang, J. Wang, Cell-like micromotors. Acc. Chem. Res. 51, 1901–1910 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.M. Iijima, Y. E. Huang, P. Devreotes, Temporal and spatial regulation of chemotaxis. Dev. Cell 3, 469–478 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.C. Shi, E. G. Pamer, Monocyte recruitment during infection and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 11, 762–774 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.B. Esteban-Fernández de Ávila, P. Angsantikul, J. Li, M. Angel Lopez-Ramirez, D. E. Ramírez-Herrera, S. Thamphiwatana, C. Chen, J. Delezuk, R. Samakapiruk, V. Ramez, M. Obonyo, L. Zhang, J. Wang, Micromotor-enabled active drug delivery for in vivo treatment of stomach infection. Nat. Commun. 8, 272 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Z. Wu, L. Li, Y. Yang, P. Hu, Y. Li, S.-Y. Yang, L. V. Wang, W. Gao, A microrobotic system guided by photoacoustic computed tomography for targeted navigation in intestines in vivo. Sci. Robot. 4, eaax0613 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.F. Zhang, Z. Li, Y. Duan, A. Abbas, R. Mundaca-Uribe, L. Yin, H. Luan, W. Gao, R. H. Fang, L. Zhang, J. Wang, Gastrointestinal tract drug delivery using algae motors embedded in a degradable capsule. Sci. Robot. 7, eabo4160 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.F. Soto, E. Karshalev, F. Zhang, B. Esteban Fernandez de Avila, A. Nourhani, J. Wang, Smart materials for microrobots. Chem. Rev. 122, 5365–5403 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.M. Aouadi, G. J. Tesz, S. M. Nicoloro, M. Wang, M. Chouinard, E. Soto, G. R. Ostroff, M. P. Czech, Orally delivered siRNA targeting macrophage Map4k4 suppresses systemic inflammation. Nature 458, 1180–1184 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Y.-B. Miao, W.-Y. Pan, K.-H. Chen, H.-J. Wei, F.-L. Mi, M.-Y. Lu, Y. Chang, H.-W. Sung, Engineering a nanoscale Al-MOF-armored antigen carried by a “trojan horse”-like platform for oral vaccination to induce potent and long-lasting immunity. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1904828 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 21.S. Sen, T. J. Mansell, Yeasts as probiotics: Mechanisms, outcomes, and future potential. Fungal Genet. Biol. 137, 103333 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.S. Lin, S. Mukherjee, J. Li, W. Hou, C. Pan, J. Liu, Mucosal immunity-mediated modulation of the gut microbiome by oral delivery of probiotics into Peyer’s patches. Sci. Adv. 7, eabf0677 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.G. D. Brown, S. Gordon, A new receptor for β-glucans. Nature 413, 36–37 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Z. Liang, Y. Yan, W. Zhang, H. Luo, B. Yao, H. Huang, T. Tu, Review of glucose oxidase as a feed additive: Production, engineering, applications, growth-promoting mechanisms, and outlook. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 1-18, 10.1080/07388551.2022.2057275, (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Y. Li, X. Zhao, X. Jiang, L. Chen, L. Hong, Y. Zhuo, Y. Lin, Z. Fang, L. Che, B. Feng, S. Xu, J. Li, D. Wu, Effects of dietary supplementation with exogenous catalase on growth performance, oxidative stress, and hepatic apoptosis in weaned piglets challenged with lipopolysaccharide. J. Anim. Sci. 98, skaa067 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]