Abstract

The present study provides evidence of how positive social interaction and the perception of psychological kinship are mechanisms by which identity fusion with the host country is associated with the psychological well-being of Venezuelan migrants in Chile. The sample consisted of 323 Venezuelan migrants, of whom 147 (45.5%) were men. The participants were residents of the city of Santiago, Chile. The variables assessed were psychological well-being, identity fusion with host country, positive social interaction, and psychological kinship. Structural equation modeling was performed to estimate the proposed mediation model. The estimation method used was robust weighted least squares estimation. The first model showed that people who felt more fused with the host country had higher levels of psychological well-being. On the other hand, the second estimated model indicated that both positive social interaction and psychological kinship fully mediate the relationship between identity fusion with the host country and immigrants’ psychological well-being. It is not the mere sensation of feeling merged with the host country that increases the psychological well-being of migrants, but rather it is the positive social interactions and feeling that members of the host country are like family that are the components that link the fusion with the host country and the psychological well-being of Venezuelan migrants in Chile.

Keywords: Psychological well-being, Identity fusion, Positive social interaction, Psychological kinship, Venezuelan migrants

Introduction

Migration is a globalized process and reaches all countries, with 3.5% of the world’s population, or more than 272 million people, currently considered international migrants (IOM, 2020). South America and Chile in particular are no exception, with migrants in the latter constituting 7.8% of the country’s total population (INE, 2021), the largest percentage coming from other Latin American countries, with Venezuelan migration being the main one in the last 10 years (DEM, 2021). Despite how attractive and hopeful it seems to be to migrate in search of better opportunities, migrating is not easy, since on the one hand one leaves behind family, friends, interpersonal relationships, economic resources, culture, and customs and, on the other hand, once migrants arrive in the host country, being part of a minority group, they often suffer experiences of prejudice and discrimination that negatively affect their health and welfare (Firat, & Noels, 2021; Lincoln et al., 2021; Urzúa et al., 2022).

There is a growing body of research providing evidence for the importance of psychological well-being on both the physical and mental health of migrants (e.g., Balidemaj et al., 2019) and how discrimination worsens this well-being (Giuliani et al., 2018; Mera-Lemp et al., 2019; Urzúa et al., 2020a). However, there is little literature that discusses factors that could mitigate the negative effect of discrimination on the welfare of south-south migrants (Urzúa et al., 2020a; Urzúa et al., 2021a; Urzúa et al., 2021b).

It has been shown that some variables related to social identity would have an important influence on the health and well-being of migrants (Balidemaj & Small, 2019; Espinosa & Tapia, 2011; Haslam et al., 2009; Luhtanen & Crocker, 1992; Phinney et al., 2001; Urzúa et al., 2022). Social identity has traditionally been defined as an individual’s knowledge that he or she belongs to certain social groups along with some emotional and value meaning to him or her of group membership (Tajfel, 1972). Social identity is not only the knowledge of being a member of the group, but also responds to an emotional attachment to the group and knowledge of the group’s social position in relation to other groups (Hogg, 2012). In this sense, people can represent the social world in terms of groups, creating socioemotional and cognitive mechanisms that are fundamental for adequate adaptation to enable them to function effectively within a dynamic and complex social context (Turner & Oakes, 1997). Alignment with a group forms positive social relationships that foster well-being and health because it provides individuals with expectations that allow for a sense of meaning, belonging, self-esteem, and stability that allows for better understanding and adjustment to a series of important life transitions such as migration processes (Jetten et al., 2012).

When immigrants arrive in a new country, they usually go through processes of constructing new social identities. Some research has shown that people with more social ties are healthier because they are the recipients of various types of support; consequently, positive social relationships ensure emotional support (availability of others who can listen sympathetically when one has a problem and show care and acceptance), instrumental support (availability of practical help and assistance), and informational support (availability of advice, information, and guidance on how to solve problems; House, 1981; Sani, 2012). Researchers have also shown that social ties lead to the perceived availability of social support, i.e., the perception that others will provide resources that may be needed and appropriate in times of need (Sani, 2012; Sarason & Sarason, 1986). According to the Social Convoy Model (Khan & Antonucci, 1980), migrants adapt their interpersonal ties as they insert themselves into the context of the new host country, in order to protect themselves from negative experiences and to be able to successfully develop their migration process. In this sense, when immigrants arrive in the new country, they seek contact and support from other compatriots, but as they settle and integrate in the host country, they are likely to open up to the experience of seeking contact and support from members of the local population (García-Cid et al., 2017). Expanding the social support network within the host country allows for the protection of mental health through coexistence, social emotional support, and satisfaction with such relationships (Herrero & Gracia, 2011). In addition, migrants who are successful in obtaining host country citizenship, longer residence in the country, better labor market position, greater language proficiency and use, and more social contacts with members of the majority group have been found to be more likely to predict alignment with the host country (e.g., Ono, 2002; Walters et al., 2007). Therefore, the stronger the ties that migrants maintain and develop both with their family and loved ones, but also with co-workers, the host community, and other local groups, the better their physical and mental health will be (Jetten et al., 2012).

In this line of studies, our research group has provided evidence of the positive effects that various variables associated with identity have on the well-being of migrants eradicated in Chile (e.g., Henríquez et al., 2021; Hun et al., 2022; Silva et al., 2016; Urzúa et al., 2021a; Urzúa et al., 2021b; Urzúa et al., 2020a). Migrating constitutes a process of interaction and cultural exchange that generates a continuous and dynamic reciprocity where some elements of one’s own identity are maintained, but identity elements of the new host place can also be incorporated (Álvarez-Benavides, 2020). For this reason, it is important to consider identity processes within migration studies since they are fundamental in the understanding of some psychological dynamics such as well-being.

An identity variable consolidated in recent years but little studied in relation to people’s well-being is identity fusion (Henríquez et al., 2020), defined as a visceral feeling of union with the group (Gómez & Vázquez, 2015), where the delimitation between personal identity and social identity becomes porous (Gómez & Vázquez, 2015; Swann et al., 2012). Highly fused individuals tend to develop feelings of connectedness and reciprocal strength with group members (Gómez et al., 2011). Feelings of connectedness is the perception of feeling powerfully bonded with the group (Swann et al., 2012), while reciprocal strength is the conviction that oneself and the group are mutually reinforcing (Gómez & Vázquez, 2015). Thus, highly fused individuals maintain both relational ties (i.e., feelings towards individual group members) and collective ties (i.e., feelings towards the group as a whole; Gómez et al., 2011, 2019) to the group to which they are fused, which maintain and reinforce the perceived connection and reciprocal strength between personal identity and group identity (Besta, 2018; Gómez et al., 2011). These relational ties are also reinforced by the fused individuals’ belief that they share a certain essence with other group members (Gómez, 2018; Whitehouse & Lanman, 2014). There is incipient evidence relating identity fusion to various indicators of well-being such as quality of life (Jaśkiewicz & Besta, 2014), life satisfaction (Grinde et al., 2018), psychological adjustment (Kiang et al., 2020), personal well-being (Zabala et al., 2020), social well-being (Zabala et al., 2020; Zumeta et al., 2020), psychological well-being (Henríquez et al., 2021), and mental well-being of individuals (Cohen et al., 2022).

To our knowledge, no study has explored the identity fusion of migrants with the host country, which is why we believe it is important to analyze this type of alignment in the context of migration. In the present study, we propose that identity fusion with the host country would have a positive relationship with the psychological well-being of migrants. Furthermore, we propose that some mechanisms that explain the relationship between identity fusion with the host country and psychological well-being would be positive social interaction and perceived psychological kinship.

On the one hand, we wanted to evaluate the role of positive social interaction, a process in which the individual assumes a social role characterized by positively valuing the relationships he maintains with his social environment (Urzúa et al., 2020b), feeling satisfaction when performing tasks related to his social circle (Lambert et al., 1996), perceiving himself as a contribution and a being appreciated by his social group, and believing that the society in which he is immersed is on a good path towards the future (Keyes, 1998). The contextual elements of society and the immigrant’s interaction with these environments have an important relationship with the psychological well-being of immigrants (Urzúa et al., 2020b). According to the secure base hypothesis of identity fusion (Klein & Bastian, 2022), individuals who exhibit high levels of identity fusion with a group would be provided by a secure base that would allow them to maintain a sense of support, security, and trust, which would translate into more open and cooperative intergroup relationships. By being aligned with a group and having it function as a secure base, fused individuals would reflect more exploratory and prosocial behavior, including greater trust in others (Mikulincer, 1998) and a lower perception of threat to strangers, thus facilitating better interpersonal and intergroup relationships (Klein & Bastian, 2022). Therefore, under the assumption that highly fused individuals stand out for maintaining strong relational and collective bonds (Gómez et al., 2011), which help preserve and strengthen their connection and reciprocal strength with the group (Besta, 2018), and which also makes them more confident of themselves and the social context around them (Klein & Bastian, 2022), we propose that highly fused migrants with the host country would tend to create and maintain better positive social interaction with the host society, and this would be reflected in higher levels of psychological well-being.

On the other hand, we have incorporated the perception of psychological kinship, defined as feeling, and behaving towards other people or groups as “if they were related,” but not genetically related to the individual (Bailey, 1988; Nava & Bailey, 1991). Recognizing that other group members share common basic characteristics would foster the perception of kinship ties with other group members (Swann et al., 2014). Perceived kinship would involve an interpersonal appraisal of affective proximity where the subject would rank other people among those whom he or she considers in-group or out-group most intimate and close (Bailey, 1988). Given that we humans would be inclined to help our close relatives, this interpersonal appraisal of more intimate affective proximity to metaphorical (non-genetically related) relatives could result in the individual responding emotionally in a manner like as if these were real relatives (genetically related; Richerson & Henrich, 2009; Robert et al., 2019).

Some research has evidenced that the kinship perception that develops from being fused with a more intimate group (local fusion) can be extended or projected to the larger group (extended fusion; Atran et al., 2014; Gómez, 2018; Swann et al., 2014; Whitehouse et al., 2014). Thus, individuals highly fused with large collectives (e.g., the nation or a religion) might create feelings of familiarity and kinship with (extended) group members whom they do not yet know and who do not have a direct genetic relationship (Buhrmester et al., 2015; Newson et al., 2018; Robert et al., 2019; Swann et al., 2012). In the case of migrants highly fused with the host country, the development of these close ties could generate mutually supportive interpersonal networks that reinforce the psychological structures that motivated their initial relationship towards members of the host country (Gómez & Vázquez, 2015; Swann et al., 2012). This emotional commitment to the host country would facilitate the satisfaction of basic needs such as belonging or the meaning of one’s own identity for highly fused individuals (Gómez et al., 2021).

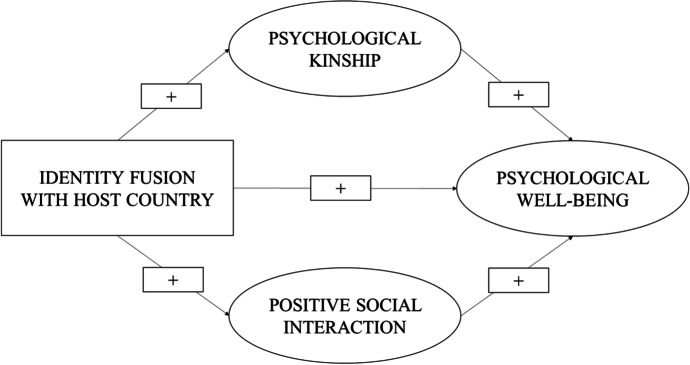

In this context, the present research seeks to explore some mechanisms that could mediate the relationship between identity fusion with the host country and psychological well-being in a migrant population. We propose that both positive social interaction and psychological kinship perception are pathways that could explain this relationship. The proposed model and the direction of the expected relationships can be seen in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The direct effects of the proposed model are presented

Method

Design and Participants

The study is correlational, non-experimental, and transversal (Ato et al., 2013). A purposive sampling was carried out based on the accessibility of the participants and using the snowball strategy to recruit them. The inclusion criteria were Venezuelan nationality and being over 18 years of age.

The sample consisted of 323 Venezuelan migrants, of whom 147 (45.5%) were men and 176 (54.5%) were women, ranging in age from 18 to 69 years (ME = 32.61; SD = 9.36). The participants were residents of the city of Santiago, Chile. Physically, participants defined themselves as White (n = 68; 21.1%), Indigenous (n = 3; 0.9%), Mestizo (n = 50; 15.5%), Afro-descendant (n = 14; 4.3%), Mulattos (n = 177; 54.8%), and other groups (n = 11; 3.4%). Most migrants arrived in the country within the last decade (n = 300; 92.9%).

Instruments

Identity Fusion

To measure the identity fusion of Venezuelan migrants with the host country, the pictorial identity fusion scale (Swann et al., 2009) was used. This instrument consists of a single item with five response options. The participant was instructed “Next, a series of figures appear, each consisting of two circles. The small circle represents you (‘I’), and the large circle represents Chile. Mark the letter of the figure that best represents how you perceive your relationship with Chile” (see Fig. 2). Higher scores would reflect higher levels of identity fusion with the host country. The pictorial identity fusion scale has provided evidence of validity and reliability in multiple studies (e.g., Swann et al., 2009; Gómez et al., 2011).

Fig. 2.

Adaptation of the pictorial identity fusion scale (Swann et al., 2009)

Positive Social Interaction

The positive social interaction scale proposed by Urzúa et al. (2020b), which consists of 18 items, was used to measure positive social interaction. The scale is made up of five dimensions: integration (e.g., “I feel that I am an important part of my community, of some social group or of my population/neighborhood”), contribution (e.g., “I think I can contribute something to the world”), actualization (e.g., “Society is improving for people like me”), acceptance (e.g., “People care about other people’s problems”), and social role adjustment (e.g., “I feel pressured at work/home”). It was answered in a Likert response format, with options ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Higher scores represent greater positive social interaction. In the present study, the scale presented acceptable Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for all its dimensions (whole scale, α = 0.89; integration, α = 0.88; contribution, α = 0.90; actualization, α = 0.90; acceptance, α = 0.77; social role adjustment, α = 0.83).

Perceptions of Psychological Kinship

An adaptation of the kin-perceptions scale (Swann et al., 2014), consisting of four items (i.e., “People from Chile are like family to me,” “If someone from Chile is hurt or in danger, it is like a family member is hurt or in danger,” “I see other members of Chile as brothers and sisters,” and “I am part of the Chilean family”) was used to measure the perception of psychological kinship. Higher scores represent higher perceptions of psychological kinship with members of the host country. In the present study, the scale presented an acceptable Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (α = 0.91).

Psychological Well-Being

The scales of psychological well-being (SPWB) by Ryff (1989), in its Spanish version of 28 items, was used to measure psychological well-being (Díaz et al., 2006). The instrument has presented valid and reliable scores in the migrant population in Chile (Henríquez et al., 2021; Silva et al., 2016). Psychological well-being is constituted by six dimensions: self-acceptance (e.g., “When I look back on the history of my life, I am happy with how things have turned out”), positive relationships (e.g., “I feel that my friendships bring me many things”), autonomy (e.g., “I am afraid to express my opinions, even if they are contrary to what most people think”), mastery of the environment (e.g., “I have been able to build a home and a way of life to my liking”), and personal growth (e.g., “Overall, over time I feel that I continue to learn more about myself”). It was answered using a Likert-type response format, with options ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Higher scores represent higher levels of psychological well-being. In the present study, the scale presents acceptable Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for all its dimensions (whole scale, α = 0.93; self-acceptance, α = 0.91; positive relationships, α = 0.88; autonomy, α = 0.86; environmental mastery, α = 0.76; purpose in life, α = 0.91; personal growth, α = 0.89).

Procedure

Participants were recruited online. The questionnaire was developed in the Google Forms platform and then shared in groups of web pages (e.g., Facebook and Instagram) that could be of interest to the migrant population in Chile (e.g., “Migrants in Chile,” “Venezuelan Community in Chile,” “Work for Venezuelans in Chile”). The inclusion criteria to participate in the study were to be over 18 years old and to be a Venezuelan migrant living in Chile. Users interested in participating entered the published link and were redirected to an informed consent page. If they accepted the consent, they were sent to the main questionnaire platform. The snowball sampling technique was used, where each participant who had completed the questionnaire was asked if he or she knew any other migrant who was willing to participate in the study. The questionnaires of people who responded very quickly (i.e., who finished answering the questionnaire before 5 min) were eliminated, since it is very likely that they had not paid enough attention to each of the items. The application of the battery of questionnaires lasted an average of 20 min, so each participant was reimbursed for their participation with an amount close to 6 dollars (5 thousand Chilean pesos). It is important to emphasize that at the time of sampling, there were strict restrictions on physical contact due to the pandemic (COVID-19), which made it impossible to complement the sample with questionnaires taken in person. The instruments and the procedure were known and approved by the ethics committee of the first author’s university.

Data Analysis

First, the measurement models were tested and adjusted through confirmatory factor analysis for each of the variables used in the study. Once the measurement models were estimated, two structural equation models were tested. The first model estimated the effect of identity fusion with the host country on the psychological well-being of Venezuelan migrants residing in Chile (M1). In the second model, multiple mediation model was conducted to estimate the indirect effects of positive social interaction and perceived psychological kinship on the relationship between identity fusion with the host country and the psychological well-being of Venezuelan migrants (M2). Age, sex, year of arrival, and self-defined phenotype were controlled for in the two models. The indirect effects of the mediation models were estimated following the recommendations of Stride et al. (2015). Goodness of fit of the models were estimated using chi-square (χ2) values, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI). According to standards recommended by the literature (e.g., Schreiber, 2017), RMSEA values ≤ 0.08, CFI ≥ 0.95, and TLI ≥ 0.95 are considered adequate and indicative of good fit. The robust weighted least squares (WLSMV) estimation method was used, which is appropriate with non-normal ordinal variables (Beauducel & Herzberg, 2006). The statistical packages used were SPSS v. 24 and MPlus v. 8.2.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 shows some descriptive statistics (n, ME, SD) of all the variables included in the model.

Table 1.

Scores and correlations of the variables included in the model

| Variables | n | ME | SD | PPK | PSI | PWB |

| Identity fusion with host country | 323 | 3.29 | 1.17 | 0.53* | 0.35* | 0.27* |

| Psychological kinship | 323 | 3.73 | 0.88 | 0.56* | 0.37* | |

| Positive social interaction | 323 | 3.83 | 0.68 | 0.62* | ||

| Psychological well-being | 323 | 4.00 | 0.68 |

PPK perceptions of psychological kinship, PSI positive social interaction, PWB psychological well-being

p < .05*

Measurement Models

Table 2 shows the goodness-of-fit indices of the analyzed measurement models. Both the positive social interaction scale and the perceptions of psychological kinship scale presented goodness-of-fit indicators close to the standards recommended by the literature (Schreiber, 2017). However, the scales of psychological well-being presented fit indices lower than expected. Therefore, it was decided to iteratively debug the initial model, eliminating the inverse items since these could be forcing an artificial dimension by wording effect (e.g., Marsh, 1996). Once the inversely worded items of each dimension of psychological well-being were eliminated, the refined measurement model proved to fit the data adequately, presenting acceptable goodness-of-fit indices (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Indicators of overall fit of measurement models

| Models | Parameters | χ2 | DF | p | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | RMSEA IC 90% | |

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| PSI | 95 | 445.064 | 130 | .00 | .980 | .977 | .087 | .078 | .096 |

| PPK | 12 | 4.818 | 2 | .00 | .992 | .977 | .066 | .000 | .144 |

| SPWB | 151 | 5264.042 | 371 | .00 | .813 | .795 | .202 | .197 | .207 |

| SPWB* | 126 | 538.965 | 246 | .00 | .987 | .986 | .061 | .054 | .068 |

Note: PSI positive social interaction, PPK perceptions of psychological kinship, SPWB scales of psychological well-being

*Refined model

Structural Equation Models

Once the measurement models were estimated and adjusted, we proceeded to examine the effect of identity fusion with the host country on the psychological well-being of Venezuelan migrants in Chile.

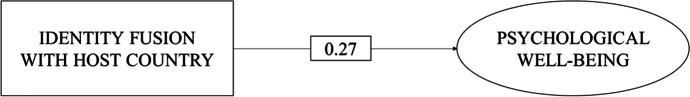

The model (M1) presented goodness-of-fit indices close to the criteria recommended by the literature (see Table 3). Figure 3 (M1) shows that identity fusion with Chile has a statistically significant positive effect of small magnitude (b > 0.20; Cohen, 1988) on the psychological well-being of migrants. The effect of age, sex, year of arrival, and self-defined phenotype was controlled for in the analysis.

Table 3.

Indicators of overall fit of structural equation models

| Models | Parameters | χ2 | DF | p | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | RMSEA IC 90% | |

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| M1 | 127 | 591.253 | 269 | .00 | .985 | .984 | .061 | .054 | .068 |

| M2 | 250 | 3592.518 | 1199 | .00 | .926 | .922 | .079 | .076 | .082 |

Fig. 3.

Relationship between identity fusion with Chile and psychological well-being. Note: Solid paths indicate significant relationships effects (p < .05)

After having estimated the relationship between identity fusion with the host country and psychological well-being (M1), the second structural model (M2) was tested. The multiple mediation model presented acceptable goodness-of-fit indices and close to the criteria recommended by the literature (see Table 3). Figure 4 (M2) shows that identity fusion with the host country has a statistically significant positive effect of moderate magnitude (b > 0.30; Cohen, 1988) on positive social interaction and a statistically significant positive effect of large magnitude (b > 0.50; Cohen, 1988) on perceptions of psychological kinship. Identity fusion with the host country had no statistically significant effect on psychological well-being. On the other hand, it can be observed that positive social interaction has a statistically significant positive effect of large magnitude (b > 0.50; Cohen, 1988) on the psychological well-being of migrants. Perceptions of psychological kinship had a statistically significant positive effect of moderate magnitude (b > 0.30; Cohen, 1988) on the psychological well-being of migrants.

Fig. 4.

Mediating effect of perceived social support on the relationship between identity fusion with Chile and psychological well-being. Note: The analysis controlled for the effects of years of stay, sex, age, and self-defined phenotype. Solid paths indicate significant relationship effects (p < .05). Non-significant paths are shown with dashed line

Finally, both positive social interaction and perceptions of psychological kinship present statistically significant indirect effects on the relationship between identity fusion with the host country and the psychological well-being of migrants (see Fig. 4). In this case, one could speak of complete mediation (Ato & Vallejo, 2011), since in the presence of the indirect effects of positive social interaction and perceptions of psychological kinship, the direct effect of identity fusion with the host country on the psychological well-being of migrants disappears.

These results demonstrate that positive social interaction and perceptions of psychological kinship could be psychological mechanisms by which identity fusion with the host country is related to the psychological well-being of Venezuelan migrants residing in Chile.

Discussion

The sociopolitical and economic situation that Venezuela is going through has led to a significant increase in the emigration of Venezuelans to other Latin American countries. In Chile, Venezuelans have become the main migratory flow that has arrived in the country in recent years. Due to this scenario, some recent studies have concentrated their efforts on examining the experiences of discrimination experienced by Venezuelan migrants in Chile (Cienfuegos-Illanes & Ruf-Toledo, 2022; Salgado et al., 2018). Despite this situation, studies related to the well-being of south-south migrants have been scarce. For this reason, the present research explored the mediating effect exerted by positive social interaction and kinship perception on the relationship between identity fusion with the host country and the psychological well-being of Venezuelan migrants residing in Chile. The results indicate that positive social interaction and kinship perception are pathways that would explain the relationship between identity fusion (i.e., a visceral feeling of union with the group, in this case, the host country) and the psychological well-being of migrants.

First, as expected, migrants with higher levels of fusion with the host country were found to have higher levels of psychological well-being than less fused migrants. These findings are concordant with previous work where it has been shown that identity fusion of international students with local students (Kiang et al., 2020) or of migrants with the host country (Henríquez et al., 2021) is associated with better well-being and psychological adjustment of individuals. This could be explained because, according to the theory of acculturation strategies, some migrants may choose to adopt some of the cultural customs of the host country and therefore come to identify with the receiving country, to achieve a better social and psychological adaptation, assuming the new culture as their own (Berry & Sabatier, 2011). However, not only adopting some customs of the dominant culture could lead to alignment with the majority group, but also the perception of equal status between the groups, cooperative intergroup contact, and opportunities for personal acquaintance that deepen closer relationships between members of both groups and generate norms of support for multiculturalism and inclusion by the authorities of the receiving country (Dovidio et al., 2000; Fleischmann & Verkuyten, 2016). Conversely, perceived social rejection and devaluation from the receiving society towards the migrant may result not only in increased identification with the minority group but also in decreased identification with the host country (Verkuyten & Martinovic, 2012). According to identity fusion theory, individuals who have shared intense experiences and emotions with other group members would increase their identity fusion with the group in general (Páez et al., 2015; Whitehouse & Lanman, 2014; Whitehouse et al., 2017; Zumeta et al., 2020); therefore, it is likely that migrants who present higher levels of identity fusion with the host country are those who have shared experiences and emotions through cooperation and mutual aid with members of the receiving country.

When migrants arrive in a new country, they reduce the number of social networks, ties, and close relationships they had in their country of origin, so it is very likely that migrants will adapt their interpersonal ties in order to regenerate the social fabric and sources of social support (García-Cid et al., 2017). As migrants adapt to the host country, they establish greater contact with members of the receiving country, which often transforms into cooperation and mutual help, thus generating sources of protection for mental health through healthy coexistence (Herrero & Gracia, 2011). For their part, migrants who manage to obtain the citizenship of the host country, a longer residence in the country, or a good job often show a greater rapprochement and alignment with the receiving country (e.g., Ono, 2002; Walters et al., 2007). Therefore, the stronger the ties that migrants maintain and develop the host society, the greater the sources of cooperation, emotional support, instrumental support, and informational support (House, 1981; Sani, 2012). It is likely that some migrants prioritize the search for and formation of support networks to increase their social capital, thus enabling them to access better living conditions (Ferrer et al., 2014). These interpersonal relationships are sometimes accompanied by cooperative social actions in conjunction with shared emotions and experiences that could be the cradle of identity fusion with the host country (Whitehouse et al., 2017). For the fused individuals, group membership becomes increasingly rewarding as it gives meaning to both their personal identity and their social identity (Gómez, 2018). Therefore, for the fused person if the group is well, the personal self will also be well, and vice versa, thus amplifying the migrant’s sense of well-being.

On the other hand, migrants who presented higher levels of identity fusion with the host country were also those who had better positive social interaction. Therefore, it is likely that people who have a visceral feeling of bonding with the host country present a higher positive valuation of the relationships they have with their environment (in the migratory context). This is consistent with the proposal of Klein and Bastian (2022) who point out that highly fused individuals would be provided with a secure base that gives them a perception of support, security, and trust, allowing for more open and cooperative intergroup relations. In this sense, migrants fused with the host country would have a secure base that allows them to establish positive relationships and more exploratory and prosocial behaviors, greater trust in others (Mikulincer, 1998), and less perceived threat in the new context (Klein & Bastian, 2022). Thus, highly fused individuals by standing out for maintaining strong relational and collective ties (Gómez et al., 2011) preserve and strengthen their connection and reciprocal strength with the group (Besta, 2018), which makes them have greater self-confidence, performing better and harmoniously in the social context that surrounds them (Klein & Bastian, 2022). Therefore, when the migrant relates to the host country, their collective and relational ties with the country are strengthened, thus feeling greater satisfaction when performing activities related to their social circle in the nation to which they migrated. Similarly, by fusing with the host country, the migrant is likely to maintain a sense of connection and reciprocal strength with the country, which would increase his or her perception of being a contribution and being appreciated by the group to which he or she is fused. In the present study, people who presented higher levels of identity fusion with the host country felt more important and valued by society, having the feeling that people care about each other’s problems. In addition, people highly fused with the country of origin presented better social adjustment, with fewer problems at work or in their educational establishment, and reporting that they made good use of their free time. In this way, the migrant fused with the host country would tend to maintain positive social interactions with his or her environment, which would be reflected in greater psychological well-being in general. Additionally, it is necessary to mention that many Venezuelan migrants see Chile not only as an economically stable country with flexible migration policies, but also as a place where they find networks of friends or relatives who have migrated before and who often receive them to support them when they have recently arrived in the country (Salgado et al., 2018), a fact that can facilitate a positive social interaction with their environment.

According to the contact hypothesis theory proposed by Allport (1954), certain conditions facilitate positive social interactions between members of the minority group and members of the majority group (Brown & Hewstone, 2005). These conditions are that members of both groups must share the same status in various social aspects; there must be institutions that support policies that help maintain positive contact between the two groups; members of both groups must share the pursuit of common goals; and there must be some degree of cooperation to achieve shared common goals (Berg, 2015). While not all conditions need to be met for positive social interaction to exist between groups, having more conditions present would increase the chances of creating a positive social interaction environment (Berg, 2015; Pettigrew, 1998). Some of these conditions are also consistent or could be related to some of the causes of fusion, such as shared experiences and emotions with the group to which the individual fuses (Páez et al., 2015; Whitehouse & Lanman, 2014; Whitehouse et al., 2017; Zumeta et al., 2020), so it could be expected that these events are behind and are facilitators to develop identity fusion with a group, and in turn, this has an impact on more positive social interactions.

Finally, it was also observed that migrants who had greater identity fusion with the host country had higher levels of perceived psychological kinship with members of the host country. According to identity fusion theory, individuals fused with a group could develop close relational ties that would translate into the perception that members of the group to which one is being fused are viewed as if they were members of one’s own family (Swann et al, 2012). Swann et al. (2014) in research that compiled six studies with subjects coming from different nationalities (China, India, USA, and Spain) showed that perceiving basic characteristics (biological or psychological) shared with the members of the group increased in highly fused people the perception of family ties with the other members of the group, which in turn caused them to be more willing to perform extreme behaviors in favor of the group. In another study by Buhrmester et al. (2015), after the Boston Marathon bombings, they showed that Americans who were fused to their country were predisposed to perceive their compatriots as psychological relatives and that this encouraged them to provide various forms of support to the victims of the attack (sending letters of encouragement or donating money). In the case of migrants who are highly fused with the host country, it is very likely that they see the rest of the members of the receiving country as if they were psychological kin. According to some authors, to develop the perception of psychological kinship, it is necessary for the individual to believe that the other members of the group share essential components of their biographical self-concept (Buhrmester et al., 2015; McAdams, 2008; Singer & Salovey, 1993; Swann et al., 2012). The shared experiences and emotions that the migrant has engaged in with members of the host country could be the reason why the migrant has developed close interpersonal relationships (e.g., romantic, intimate, friendship, work, or mutual aid with members of the host country) and a fraternal bond with the host country. Thus, it is very likely that the migrant will develop perceptions of family ties with members of the host country. For Bailey (1988), the psychological kinship that patients develop with their therapist is beneficial for therapy, since this strategy helps to create bonds of trust and security, where the therapist goes from being an unknown professional to being an intimate person who is a support figure for the patient. For his part, Durkheim (1897/2007) early on pointed out that the larger the family, the less likely its members were to commit suicide; for this reason, he argued that the more intense social life offered by larger families constitutes a protective factor against suicide (Sani, 2012). In a more current systematic review, it was found that familism or family unity would be related to better mental health outcomes in the Latino population (Valdivieso-Mora et al., 2016). This is explained because the family unit is a cultural value of great importance in Hispanic cultures as it appeals to respect, support, obligation, and cooperation towards beings considered as relatives (Calzada et al., 2012), which would have a buffering effect for stressful life experiences (Tubman & Windle, 1995; Valdivieso-Mora et al., 2016). In this sense, and as pointed out by some authors, family relationships or perceived as such become more important for well-being as people’s social networks diminish (e.g., Thomas et al., 2017) as is the case for migrants arriving in a new country.

Migration is currently one of the largest social processes that affects multiple socio-cultural aspects of both the countries of origin and the host countries. Many migrants leave friends, families, and loved ones in their countries of origin, so in the new host country, they seek to expand their support networks to better cope with the cultural and linguistic challenges they face daily. Immigrants not only experience changes in their social networks, but also exposure to new value systems and cultural identifications that can sometimes clash with their cultural values and practices of origin (Repke & Benet-Martínez, 2019). For Benet-Martínez (2018), the way migrants negotiate their group alignments with the host country varies for everyone, depending on the sociopolitical context, their preferences, and personal skills. For this reason, good management of migration processes is necessary, ensuring that the actions taken by the authorities in charge are well informed and with as much information as possible, so that the actions they promote can positively affect the well-being of the groups involved. Governments and authorities of sending and receiving countries should increase their efforts to have greater coordination in improving the conditions of people moving between their countries. In addition, host countries should more strongly implement programs that promote the diversity of people living in the nation, as this would bring cultural and economic benefits to the host country (Taylor, 1992). Ignoring and not recognizing cultural diversity provokes resistance and rejection by minority groups, making national unity look suspicious and taken as a fiction (Modood, 2007; Parekh, 2001). For a society to function well, it is necessary for its members to have a sense of commitment and common belonging, so it is important to foster social cohesion that makes everyone feel they belong to the host country. States must include in their worldview the cultural diversity of the people in their territory, through policies that promote structural, cultural, social, and emotional integration (Verkuyten & Martinovic, 2012). Consequently, this research sought to contribute to knowledge in this line, exploring some identity aspects that could be relevant when analyzing in what terms the incorporation of migrants to the host country is taking place and how coexistence and well-being among the groups could be facilitated. The observed results show that positive social interaction and the perception of kinship are mechanisms that could explain the relationship between the fusion of identity with the host country and the psychological well-being of Venezuelan migrants living in Chile. Therefore, those migrants who present a visceral feeling of union with the host country see the members of the host country as a family with whom they have positive daily interactions, which translates into a better well-being for their stay in the new context.

Limitations

Although the present study may be of great relevance, it is important to point out some limitations of these results. First, it should be considered that the study was cross-sectional in nature, so causal effects cannot be attributed to the relationships between variables. However, alignment with a group and well-being function as a virtuous circle (Jetten et al., 2012; Sani, 2012), because alignment with a group can lead to better well-being, but in turn people with higher well-being might be more motivated to participate and feel united with a group. Second, the sample was biased towards Venezuelan migrants who wanted to participate in the study, so the conclusions that could be reached would only be plausible for a population such as the sample (e.g., people with internet access) and could not be generalized to migrants from other countries or in other conditions. In addition, it would be desirable for further research to include other migrant populations in other contexts, to see if the observed relationships are replicated. Future researchers should also include different measures of group alignment to see if they complement or differ in their impact on migrants’ psychological well-being. Finally, to gain a deeper understanding of participants’ experiences, it would be desirable to complement these findings with qualitative methodologies.

Author Contribution

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Diego Henríquez and Alfonso Urzúa. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Diego Henríquez, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This publication is derived from the project FONDECYT Regular #1180315, funded by the National Agency for Research and Development (ANID) of the Government of Chile, who had no influence on the results of this publication.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due the fact that they constitute an excerpt of research in progress but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

The present research is part of the FONDECYT 1180315, which has been reviewed and approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee of Universidad Católica del Norte, Chile. Each of the participants signed a consent form.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-Benavides, A. (2020). Migraciones e identidad. Una aproximación desde la teoría de la identidad colectiva y desde la teoría del sujeto. Revista Latinoamericana,1(1), 97–115. 10.5377/rlpc.v1i1.9518 [Google Scholar]

- Ato, M., López-García, J. J., & Benavente, A. (2013). Un sistema de clasificación de los diseños de investigación en psicología. Anales de Psicología/Annals of Psychology, 29(3), 1038–1059. 10.6018/analesps.29.3.178511

- Ato, M., & Vallejo, G. (2011). Los efectos de terceras variables en la investigación psicológica. Anales De Psicología/annals of Psychology,27(2), 550–561. 10.6018/analesps [Google Scholar]

- Atran, S., Sheikh, H., & Gómez, Á. (2014). For cause and comrade: Devoted actors and willingness to fight. Cliodynamics, 5(1). 10.21237/C7clio5124900

- Bailey, K. G. (1988). Psychological kinship: Implications for the helping professions. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training,25(1), 132. 10.1037/h0085309 [Google Scholar]

- Balidemaj, A., & Small, M. (2019). The effects of ethnic identity and acculturation in mental health of immigrants: A literature review. International Journal of Social Psychiatry,65(7–8), 643–655. 10.1177/0020764019867994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauducel, A., & Herzberg, P. Y. (2006). On the performance of maximum likelihood versus means and variance adjusted weighted least squares estimation in CFA. Structural Equation Modeling,13(2), 186–203. 10.1207/s15328007sem1302_2 [Google Scholar]

- Benet-Martínez, V. (2018). Multicultural identity and experiences: Cultural, social, and personality processes. In K. Deaux & M. Snyder (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of personality and social psychology (2nd ed., Vol. 1). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190224837.013.29

- Berg, J. A. (2015). Explaining attitudes toward immigrants and immigration policy: A review of the theoretical literature. Sociology Compass,9(1), 23–34. 10.1111/soc4.12235 [Google Scholar]

- Berry, J. W., & Sabatier, C. (2011). Variations in the assessment of acculturation attitudes: Their relationships with psychological wellbeing. International Journal of Intercultural Relations,35(5), 658–669. 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.02.002 [Google Scholar]

- Besta, T. (2018). Independent and interdependent? Agentic and communal? Self-construals of people fused with a group. Anales De Psicología/annals of Psychology,34(1), 123–134. 10.6018/analesps.34.1.266201 [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R., & Hewstone, M. (2005). An integrative theory of intergroup contact. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology, 37, pp. 255–343. Elsevier Academic Press. 10.1016/S0065-2601(05)37005-5

- Buhrmester, M. D., Fraser, W. T., Lanman, J. A., Whitehouse, H., & Swann, W. B., Jr. (2015). When terror hits home: Identity fused Americans who saw Boston bombing victims as “family” provided aid. Self and Identity,14(3), 253–270. 10.1080/15298868.2014.992465 [Google Scholar]

- Calzada, E. J., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., & Yoshikawa, H. (2012). Familismo in Mexican and Dominican families from low-income, urban communities. Journal of Family Issues,34(12), 1696–1724. 10.1177/0192513X12460218 [Google Scholar]

- Cienfuegos-Illanes, J., & Ruf-Toledo, I. (2022). Profesionales de nacionalidad venezolana en Chile: barreras, estrategias y trayectorias de su migración. Estudios Públicos,165, 77–104. 10.38178/07183089/1314210429 [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, E., Davis, A. J., & Taylor, J. (2022). Interdependence, bonding and support are associated with improved mental wellbeing following an outdoor team challenge. Applied Psychology: Health and Well‐Being. 1–24. 10.1111/aphw.12351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Departamento de Extranjería y Migración [DEM] (2021). Estadísticas Migratorias. Registros y Administrativos del Departamento de Extranjería y Migración. Retrieved January 20, 2022, from https://www.extranjeria.gob.cl/estadisticas-migratorias/

- Díaz, D., Rodríguez-Carvajal, R., Blanco, A., Moreno-Jiménez, B., Gallardo, I., Valle, C. & van Diedrendock, D. (2006). Adaptación española de las escalas de bienestar psicológico de Ryff. Psicothema, 18(3), 572–577. Retrieved October 13, 2022, from https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/727/72718337.pdf [PubMed]

- Dovidio, J. F., Gaertner, S. L., & Kafati, G. (2000). Group identity and intergroup relations. In Advances in group processes. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. 10.1016/S0882-6145(00)17002-X [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, E. (1897/2007). On suicide. London, UK: Penguin.

- Espinosa, A., & Tapia, G. (2011). Identidad nacional como fuente de bienestar subjetivo y social. Boletín de psicología, 102(2), 71–87. Retrieved October 13, 2022, from https://www.uv.es/seoane/boletin/previos/N102-5.pdf

- Ferrer, R., Palacio, J., Hoyos, O., & Madariaga, C. (2014). Proceso de aculturación y adaptación del inmigrante: características individuales y redes sociales. Psicología desde el Caribe,31(3), 557–576. 10.14482/psdc.31.3.4766 [Google Scholar]

- Firat, M., & Noels, K. A. (2021). Perceived discrimination and psychological distress among immigrants to Canada: The mediating role of bicultural identity orientations. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 1368430221990082. 10.1177/1368430221990082

- Fleischmann, F., & Verkuyten, M. (2016). Dual identity among immigrants: Comparing different conceptualizations, their measurements, and implications. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology,22(2), 151–165. 10.1037/cdp0000058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Cid, A., Hombrados-Mendieta, I., Gómez-Jacinto, L., Palma-García, M. D. L. O., & Millán-Franco, M. (2017). Apoyo social, resiliencia y región de origen en la salud mental y la satisfacción vital de los inmigrantes. Universitas Psychologica,16, 91–104. [Google Scholar]

- Giuliani, C., Tagliabue, S., & Regalia, C. (2018). Psychological well-being, multiple identities, and discrimination among first and second generation immigrant Muslims. Europe’s Journal of Psychology,14(1), 66. 10.5964/ejop.v14i1.1434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, Á., & Vázquez, A. (2015). El poder de ‘sentirse uno’ con un grupo: Fusión de la identidad y conductas progrupales extremas. Revista De Psicología Social,30(3), 1–31. 10.1080/02134748.2015.1065089 [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, Á., Brooks, M. L., Buhrmester, M. D., Vázquez, A., Jetten, J., & Swann, W. B., Jr. (2011). On the nature of identity fusion: Insights into the construct and a new measure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,100(5), 918–933. 10.1037/a0022642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, Á., Vázquez, A., López-Rodríguez, L., Talaifar, S., Martínez, M., Buhrmester, M. D., & Swann, W. B., Jr. (2019). Why people abandon groups: Degrading relational vs collective ties uniquely impacts identity fusion and identification. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology,85, 103853. 10.1016/j.jesp.2019.103853 [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, Á., Martínez, M., Martel, F. A., López-Rodríguez, L., Vázquez, A., Chinchilla, J., ... & Swann, W. B. (2021). Why people enter and embrace violent groups. Frontiers in psychology, 3823. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.614657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gómez, A. (2018). Psicología social aplicada a la violencia y el extremismo. El caso de la fusión de identidad. In: Vázquez, A., & Gómez, A. (Eds.), Psicología Social (pp. 389–434). Sans y Torres.

- Grinde, B., Nes, R. B., MacDonald, I. F., & Wilson, D. S. (2018). Quality of life in intentional communities. Social Indicators Research,137(2), 625–640. 10.1007/s11205-017-1615-3 [Google Scholar]

- Haslam, S. A., Jetten, J., Postmes, T., & Haslam, C. (2009). Social identity, health and well-being: An emerging agenda for applied psychology. Applied Psychology,58(1), 1–23. 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00379.x [Google Scholar]

- Henríquez, D., Urzúa, A., & López-López, W. (2020). Identity fusion: A systematic review. Acta Colombiana de Psicología,23(2), 383–409. Retrieved July 30, 2020, from 10.14718/ACP.2020.23.2.15

- Henríquez, D., Urzúa, A., & López-López, W. (2021). Indicators of identity and psychological well-being in immigrant population. Frontiers in psychology, 4729. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.707101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Herrero, J., & Gracia, E. (2011). Covariates of subjective well-being among Latin American immigrants in Spain: The role of social integration in the community. Journal of Community Psychology,39(7), 761–775. 10.1002/jcop.20468 [Google Scholar]

- Hogg, M. A. (2012). Social identity and the psychology of groups. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (2nd ed., pp. 502–519). NewYork: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- House, J. S. (1981). Work stress and social support. Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Hun, N., Urzúa, A., Henríquez, D. T., & López-Espinoza, A. (2022). Effect of ethnic identity on the relationship between acculturation stress and abnormal food behaviors in Colombian migrants in Chile. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities,9(2), 413–419. 10.1007/s40615-021-00972-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas [INE] y Departamento de Extranjería y Migración [DEM] (2021). Estimación de personas extranjeras residentes en Chile al 31 de diciembre 2020. Retrieved August 30, 2022, from https://www.ine.cl/docs/default-source/demografia-y-migracion/publicaciones-y-anuarios/migración-internacional/estimación-población-extranjera-en-chile-2018/estimación-población-extranjera-en-chile-2020-metodología.pdf

- International Organization for Migration (IOM, 2020). World Migration Report 2020. IOM, Geneva. Retrieved September 18, 2021, from https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/wmr_2020_es.pdf

- Jaśkiewicz, M., & Besta, T. (2014). Is easy access related to better life? Walkability and overlapping of personal and communal identity as predictors of quality of life. Applied Research in Quality of Life,9(3), 505–516. 10.1007/s11482-013-9246-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jetten, J., Haslam, S. A., & Haslam, C. (2012). The case for a social identity analysis of health and well-being. In J. Jetten, C. Haslam, & S. A. Haslam (Eds.), The social cureIdentity: health and well-being (pp. 3–19). Psychology Press.

- Keyes, C. (1998). Social well-being. Social Psychology Quarterly,61, 121–140. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, R. L., & Antonucci, T. C. (1980). Convoys over the life course: Attachment, roles and social support. In P. Baltes & O. Brim (Eds.), Life span development and behavior, 3 (pp. 253–286). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kiang, L., C. Brunsting, N., Tevis, T., Zachry, C., He, Y., & Takeuchi, R. (2020). Identity fusion and adjustment in international students at US colleges and universities. Journal of Studies in International Education, 1028315320932320. 10.1177/1028315320932320

- Klein, J. W., & Bastian, B. (2022). The fusion-secure base hypothesis. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10888683221100883. 10.1177/10888683221100883 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lambert, M. J., Hansen, N. B., Umpress, V., Lunnen, K., Okiishi, J., & Burlingame, G. M. (1996). Administration and scoring manual for the OQ-45.2. United States: American Professional Credentialing Services. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, A. K., Cardeli, E., Sideridis, G., Salhi, C., Miller, A. B., Da Fonseca, T., ... & Ellis, B. H. (2021). Discrimination, marginalization, belonging, and mental health among Somali immigrants in North America. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 91(2), 280. 10.1037/ort0000524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Luhtanen, R., & Crocker, J. (1992). A collective self-esteem scale: Self-evaluation of one’s social identity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin,18(3), 302–318. 10.1177/0146167292183006 [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, H. W. (1996). Positive and negative global self-esteem: A substantively meaningful distinction or artifactors? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,70(4), 810. 10.1037//0022-3514.70.4.810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdams, D. P. (2008). Personal narratives and the life story. In O. John, R. Robins, & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 241–261). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mera-Lemp, M. J., Ramírez-Vielma, R., Bilbao, M. D. L. Á., & Nazar, G. (2019). La discriminación percibida, la empleabilidad y el bienestar psicológico en los inmigrantes latinoamericanos en Chile. Revista De Psicología Del Trabajo y De Las Organizaciones,35(3), 227–236. 10.5093/jwop2019a24 [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer, M. (1998). Attachment working models and the sense of trust: An exploration of interaction goals and affect regulation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,74(5), 1209–1224. 10.1037/0022-3514.74.5.1209 [Google Scholar]

- Modood, T. (2007). Multiculturalism. Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nava, G. R., & Bailey, K. G. (1991). Measuring psychological kinship: Scale refinement and validation. Psychological Reports,68(1), 215–227. 10.2466/pr0.1991.68.1.215 [Google Scholar]

- Newson, M., Bortolini, T., Buhrmester, M., da Silva, S. R., da Aquino, J. N. Q., & Whitehouse, H. (2018). Brazil’s football warriors: Social bonding and inter-group violence. Evolution and Human Behavior,39(6), 675–683. 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2018.06.010 [Google Scholar]

- Ono, H. (2002). Assimilation, ethnic competition, and ethnic identities of US-born persons of Mexican origin. International Migration Review,36(3), 726–745. 10.1111/j.1747-7379.2002.tb00102.x [Google Scholar]

- Páez, D., Rimé, B., Basabe, N., Wlodarczyk, A., & Zumeta, L. (2015). Psychosocial effects of perceived emotional synchrony in collective gatherings. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,108(5), 711. 10.1037/pspi0000014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parekh, B. (2001). Rethinking multiculturalism: Cultural diversity and political theory. Ethnicities,1(1), 109–115. 10.1177/146879680100100112 [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew, T. F. (1998). Reactions toward the new minorities of Western Europe. Annual Review of Sociology,24(1), 77–103. 10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.77 [Google Scholar]

- Phinney, J. S., Horenczyk, G., Liebkind, K., & Vedder, P. (2001). Ethnic identity, immigration, and well-being: An interactional perspective. Journal of Social Issues,57(3), 493–510. 10.1111/0022-4537.00225 [Google Scholar]

- Repke, L., & Benet-Martínez, V. (2019). The interplay between the one and the others: Multiple cultural identifications and social networks. Journal of Social Issues,75(2), 436–459. 10.1111/josi.12323 [Google Scholar]

- Richerson, P., & Henrich, J. (2009). Tribal social instincts and the cultural evolution of institutions to solve collective action problems. Context and the Evolution of Mechanisms for Solving Collective Action Problems Paper. 10.2139/ssrn.1368756 [Google Scholar]

- Robert, L., Virpi, L., & John, L. (2019). Self sacrifice and kin psychology in war: Threats to family predict decisions to volunteer for a women’s paramilitary organization. Evolution and Human Behavior,40(6), 543–550. 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2019.06.001 [Google Scholar]

- Ryff, C. D. (1989). Beyond Ponce de Leon and life satisfaction: New directions in quest of successful aging. International Journal of Behavioral Development,12, 35–55. 10.1177/016502548901200102 [Google Scholar]

- Salgado, F., Contreras, C., & Albornoz, L. (2018). La migración venezolana en Santiago de Chile: entre la inseguridad laboral y la discriminación. RIEM. Revista internacional de estudios migratorios,8(1), 81–117. 10.25115/riem.v8i1.2164 [Google Scholar]

- Sani, F. (2012). Group identification social relationships and health. In J. Jetten, C. Haslam, & S. A. Haslam (Eds.), The social cure: Identity, health and well-being (pp. 21–37). Psychology Press.

- Sarason, I. G., & Sarason, B. R. (1986). Experimentally provided social support. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,50(6), 1222–1225. 10.1037/0022-3514.50.6.1222 [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber, J. B. (2017). Update to core reporting practices in structural equation modeling. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy,13, 634–643. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2016.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva, J., Urzúa, A., Caqueo-Urizar, A., Lufin, M., & Irarrazaval, M. (2016). Bienestar psicológico y estrategias de aculturación en inmigrantes afrocolombianos en el norte de Chile. Interciencia, 41(12), 804–811. Retrieved July 18, 2022, from https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/339/33948806002.pdf

- Singer, J. A., & Salovey, A. P. (1993). The remembered self. The Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stride C.B., Gardner S., Catley. N. & Thomas, F. (2015). 'Mplus code for mediation, moderation, and moderated mediation models'. http://www.offbeat.group.shef.ac.uk/FIO/mplusmedmod.htm

- Swann, W. B., Jr., Gómez, Á., Seyle, D. C., Morales, J., & Huici, C. (2009). Identity fusion: The interplay of personal and social identities in extreme group behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,96(5), 995–1011. 10.1037/a0013668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann, W. B., Jr., Jetten, J., Gómez, Á., Whitehouse, H., & Bastian, B. (2012). When group membership gets personal: A theory of identity fusion. Psychological Review,119(3), 441–456. 10.1037/a0028589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann Jr, W. B., Buhrmester, M. D., Gómez, A., Jetten, J., Bastian, B., Vázquez, A., ... & Zhang, A. (2014). What makes a group worth dying for? Identity fusion fosters perception of familial ties, promoting self-sacrifice. Journal of personality and social psychology, 106(6), 912. 10.1037/a0036089 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tajfel, H. (1972). Social categorization: Englishmanuscript of La catégorisation socialé. In S. Moscovici (Ed.), Introduction à la psychologie sociale (Vol. 1, pp. 272–302). Larousse. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, C. (1992). Multiculturalism and the politics of recognition. University of Princeton Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, P. A., Liu, H., & Umberson, D. (2017). Family relationships and well-being. Innovation in aging,1(3), igx025. 10.1093/geroni/igx025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tubman, J. G., & Windle, M. (1995). Continuity of difficult temperament in adolescence: Relations with depression, life events, family support, and substance use across a one-year period. Journal of Youth and Adolescence,24(2), 133–153. 10.1007/BF01537146 [Google Scholar]

- Turner, J. C., & Oakes, P. J. (1997). The socially structured mind. In C. McGarty & S. A. Haslam (Eds.), The message of social psychology (pp. 355–373). Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Urzúa, A., Henríquez, D., & Caqueo-Urízar, A. (2020a). Affects as mediators of the negative effects of discrimination on psychological well-being in the migrant population. Frontiers in Psychology,11, 3421. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.602537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urzúa, A., Leiva, J., & Caqueo-Urízar, A. (2020b). Effect of positive social interaction on the psychological well-being in South American immigrants in Chile. Journal of International Migration and Integration,21, 295–306. 10.1007/s12134-019-00731-7 [Google Scholar]

- Urzúa, A., Caqueo-Urízar, A., Henríquez, D., Domic, M., Acevedo, D., Ralph, S., Reyes, G., & Tang, D. (2021a). Ethnic identity as a mediator of the relationship between discrimination and psychological well-being in south-south migrant populations. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health,18(5), 2359. 10.3390/ijerph18052359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urzúa, A., Caqueo-Urízar, A., Henríquez, D., & Williams, D. R. (2021b). Discrimination and health: The mediating effect of acculturative stress. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health,18(10), 5312. 10.3390/ijerph18105312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urzúa, A., Henríquez, D., Caqueo-Urízar, A., & Landabur, R. (2022). Ethnic identity and collective self-esteem mediate the effect of anxiety and depression on quality of life in a migrant population. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health,19(1), 174. 10.3390/ijerph19010174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdivieso-Mora, E., Peet, C. L., Garnier-Villarreal, M., Salazar-Villanea, M., & Johnson, D. K. (2016). A systematic review of the relationship between familism and mental health outcomes in Latino population. Frontiers in Psychology,7, 1632. 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkuyten, M., & Martinovic, B. (2012). Immigrants’ national identification: Meanings, determinants, and consequences. Social Issues and Policy Review,6(1), 82–112. 10.1111/j.1751-2409.2011.01036.x [Google Scholar]

- Walters, D., Phythian, K., & Anisef, P. (2007). The acculturation of Canadian immigrants: Determinants of ethnic identification with the host society. Canadian Review of Sociology/revue Canadienne De Sociologie,44(1), 37–64. 10.1111/j.1755-618X.2007.tb01147.x [Google Scholar]

- Whitehouse, H., & Lanman, J. A. (2014). The ties that bind us: Ritual, fusion, and identification. Current Anthropology,55(6), 674–695. 10.1086/678698 [Google Scholar]

- Whitehouse, H., McQuinn, B., Buhrmester, M., & Swann, W. B. (2014). Brothers in arms: Libyan revolutionaries bond like family. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,111(50), 17783–17785. 10.1073/pnas.1416284111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehouse, H., Jong, J., Buhrmester, M. D., Gómez, Á., Bastian, B., Kavanagh, C. M., ... & Gavrilets, S. (2017). The evolution of extreme cooperation via shared dysphoric experiences. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 1–10. 10.1038/srep44292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zabala, J., Conejero, S., Pascual, A., Alonso-Arbiol, I., Amutio, A., Torres-Gomez, B., et al. (2020). Basque ethnic identity and collective empowerment: Two key factors in well-being and community participation. Frontiers in Psychology,11, 606316. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.606316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zumeta, L. N., Castro-Abril, P., Méndez, L., Pizarro, J. J., Wlodarczyk, A., Basabe, N., Navarro-Carrillo, G., Padoan-De Luca, S., da Costa, S., Alonso-Arbiol, I., Torres-Gómez, B., Cakal, H., Delfino, G., Techio, E. M., Alzugaray, C., Bilbao, M., Villagrán, L., LópezLópez, W., Ruiz-Pérez, J. I., … Pinto, I. R. (2020). Collective effervescence, self-transcendence, and gender differences in social well-being during 8 march demonstrations. Frontiers in Psychology,11, 607538. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.607538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due the fact that they constitute an excerpt of research in progress but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.