Abstract

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19), which emerged in 2019, has induced worldwide chaos. The main cause of COVID-19 mass infection indoors is the spread of virus-containing droplets via indoor airflow, which is affected by air conditioners and purifiers. Here, ten experimental cases were established to analyze how use of air purifiers affects the spread of virus-containing droplets. The experiments were conducted in a school classroom with an air conditioner in summer. In the droplet dispersion experiment, paraffin oil was used as the droplet substance. Two main scenarios were simulated: (1) an infected student was seated in the back of the classroom; and (2) the teacher, standing in the front of the classroom, was infected. The results were expressed using two parameters: peak concentration and loss rate, which reflect the degree of direct and indirect infection (airborne infection), respectively. The air purifier induced a peak concentration decrease of 42% or an increase of 278%, depending on its location in the classroom. Conversely, when the air purifier was operated in the high mode (flow rate = 500 CMH; cubic meters per hour), the loss rate showed that the amount of droplet nuclei only decreased by 39% and the droplet amount decreased by 22%. Thus, the airborne infection degree can be significantly reduced. Finally, the use of air purifiers in the summer may be helpful in preventing group infections by reducing the loss rate and peak concentration if the air purifier is placed in a strategic location, according to the airflow of the corresponding room.

Keywords: COVID-19, Droplet dispersion, Airborne infection, Indoor, Air purifier, Air conditioner

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19), which emerged in December 2019, is a threat to human health [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) is making efforts to prevent its spread, including having declared it as a pandemic [2]. COVID-19 is primarily transmitted from person to person [[3], [4], [5]]; in an enclosed environment, the virus of an infected person is released into the air when coughing, sneezing, or even talking, and spreads through aerosols and droplets [6,7].

Recently, many cases of COVID-19 group infection have been reported in places with operating indoor air conditioners [8]. Lu et al. [9] analyzed nine cases of group infection that occurred in a restaurant in Guangzhou, China, in January 2020 and determined that the main underlying cause was the air-conditioning effect. When an air conditioner is in operation, the strong air flow causes airborne droplets to spread rapidly throughout the space, which leads to group infection. In the summer, the air conditioner operation rate is high owing to the high temperature and humidity; therefore, preparing for the spread of droplets when operating an air conditioner is essential [10].

The use of air purifiers is on the rise worldwide. The reasons for their use vary widely from country to country. South Korea and China have large amounts of fine dust; thus, in these countries, air purifiers are used to remove it [11,12]. In Japan, air purifiers are mainly purchased to prevent allergies caused by pollen [13]. In the United States, air purifiers are used to purify the air from the dust derived from carpets and pets [14]. For these reasons, the supply of air purifiers has expanded significantly.

Recent studies have shown that air purifiers are effective in reducing the spread of COVID-19 [15]. According to a study by Zhao [16], the use of air purifiers in dental clinics suppressed the spread of droplets through the oral cavity during the COVID-19 pandemic, thus helping prevent COVID-19 spread. Chen et al. [17] also argued that the use of air purifiers in dental clinics is an effective way to reduce the exposure to airborne droplets and aerosol particles. Mousavi et al. [18] analyzed the effects of using an air purifier in a COVID-19 ward. When using an air purifier in an isolated space, a 99% COVID-19 spread suppressing effect was observed, with the optimal location of the air purifier being near the bed of the infected patient. Therefore, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend the use of portable air purifiers with HEPA filters during pandemics [19].

In contrast, some studies have shown that the use of air purifiers can increase COVID-19 spread. Ham [20] argued that a group infection that occurred in a call center company in South Korea may have been caused by the airflow generated by an air purifier that spread the droplets produced by the cough of an infected person. These conflicting claims about the use of air purifiers during the COVID-19 pandemic have led to confusion about whether the use of an air purifier can help prevent COVID-19 spread or not.

Therefore, we aimed to investigate how the use of an air purifier affects the actual droplet diffusion. The experiment in this study was performed in the summer, with an electric heat pump (EHP) and an air conditioner. The experiment was divided into ten different cases, in which the particle generation location, location of the air purifier, and air volume of the air purifier (mode of operation) were changed. Thus, the effect of the air purifier on droplet diffusion was quantitatively evaluated.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Size of the virus and droplets

The size of viruses can vary from 20 to 300 nm [21]. Chen et al. [22] reported that the size of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus causing COVID-19, is approximately 50–200 nm. SARS-CoV-2 is transmitted by dispersion of the droplets of an infected person when they cough, sneeze, or talk, since the virus is present in these droplets. Therefore, it is the droplet size, and not the size of the SARS-CoV-2 virus itself, that is key when studying the spread of COVID-19. This is because since SARS-CoV-2 is trapped in the droplet, its movement depends on the movement of the droplet. Therefore, we examined the size of the droplets by spraying a substance similar to that of droplets.

Through microscopic analysis, Roland [23] found that the size of the droplets derived from humans talking or coughing, ranged between 1 and 500 μm. Among all droplets, 95% of them had a radius of less than 50 μm and most of them had a radius of approximately 5 μm. According to the WHO, when the human saliva particle size is smaller than 5 μm, it is defined as a droplet nucleus, whereas when it is larger than 5 μm, it is defined as a droplet [24]. Droplets typically travel up to 2 m away from the infected person [25]. A direct viral infection can be prevented if a certain distance (2 m or more) is maintained because droplets easily sink under the influence of gravity when there is no wind, since the particle size is relatively large [26,27]. However, as mentioned above, droplets may propagate further owing to various external factors, such as the airflow created by an air conditioner or air purifier.

As droplet nuclei are relatively small and float in the air for a long period, they can spread over very long distances in the presence of air currents [28]. However, since each droplet nucleus contains a low viral load, the risk of infection due to the spread of droplet nuclei is quite low [29]. Nevertheless, some studies have reported that a risk of infection by droplet nuclei in the form of aerosols exists if the exposure is prolonged and in a closed environment. Shen et al. [30], who analyzed the cluster infection that occurred inside a bus, suggested the possibility of airborne infection by the spread of droplet nuclei from the infected person to passengers seated far away from the infected person. Nissen et al. [31] confirmed that the virus was detected in a central ventilation system away from the patient area at Uppsala University Hospital in Sweden, and based on this, reported that SARS-CoV-2 could spread via aerosols.

In this study, the experiment was conducted by emitting particles similar to droplets because it was not possible to conduct an experiment using an actual virus. The particles were divided according to their size: particles with a size of 5 μm or more, and particles with a size of 5 μm or less. The particles whose size was larger than 5 μm simulated droplets, and those whose size was smaller than 5 μm simulated droplet nuclei, whose spread is responsible for airborne infections. To assess the impact of the virus as a whole, the PM10 mass concentration was evaluated using the evaluation method used by Han et al. [32].

2.2. Selection of substances to use for droplet simulation

In an experiment that simulates actual droplet diffusion, the selection of the material used is very important. NaCl, KCl, and paraffin liquid are surrogate solutions used by many researchers in experiments to simulate droplets [[33], [34], [35]]. In this study, five alternative solutions used in previous studies were selected [[33], [34], [35]], and the particle size distribution according to the concentration of the solution was analyzed (Table 1 ). The analysis was performed by the Korea Conformity Laboratories, an authorized analysis institution. Among the above experiments, paraffin oil is suitable for describing human droplets with large particles due to its large diameter and its wide use in face mask tests to block human droplets; thus, it is judged to be qualified as a human droplet description material [36,37]. Paraffin oil density is lower than that of actual human droplets, so the residence time in the air may be long. In this experiment, the density difference was not significant, as we compared only the relative concentration in each case. Therefore, we used paraffin liquid for the droplet experiments in this study. Special attention was required since paraffin liquid can cause respiratory disorders; therefore, the experiments were conducted in a strictly controlled place without people.

Table 1.

Substance selection for droplet simulation.

| Type | Particle number concentration (#/cc) | Mass concentration (μg/m3) | Median particle size (nm) | Mean particle size (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NaCl 2% | 211.12 | 76.1 | 93.3 | 121.7 |

| NaCl 5% | 680.16 | 130.5 | 70.2 | 93.6 |

| KCl 2% | 763.23 | 15.4 | 82.4 | 102.9 |

| KCl 30% | 198.64 | 157.4 | 127.7 | 165.1 |

| Paraffin liquid | 842.4 | 1.75 × 103 | 230 | 262.2 |

2.3. Emission particle concentration change pattern

When droplets are generated from the mouth while sneezing or coughing, their concentration increases instantaneously. The initial droplet instantaneous peak concentration generated when an infected person sneezes or coughs is very high, inducing the transmission of the infectious disease to other humans. Thereafter, the droplet concentration decreases rapidly, owing to the deposition or diffusion of the droplets. After a certain period, the droplet concentration decreases stably. During this stage, droplets remain suspended in the air for a long time, potentially causing airborne infections [24].

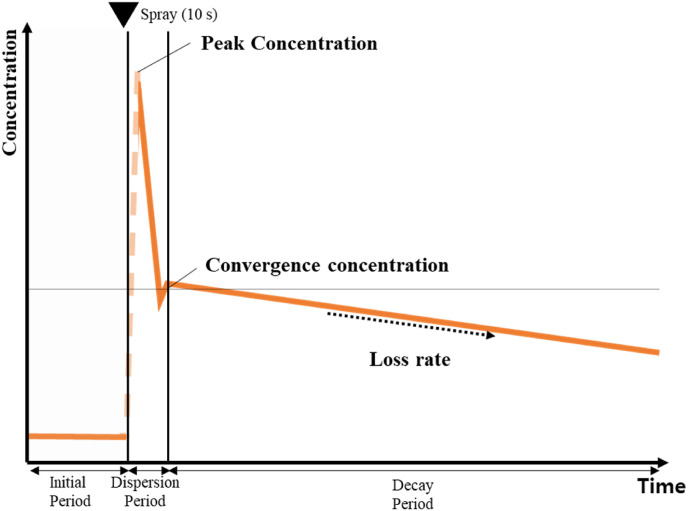

In this study, a particle generation experiment was conducted by simulating the droplet concentration patterns. Fig. 1 shows the particle concentration patterns used in the particle emission experiments, considering what happens when an infected person sneezes. In this situation, to understand the spread of a virus, we need to understand the peak concentration and the loss rate trends in the particle decay period.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of the droplet dispersion stages.

2.3.1. Peak concentration

Droplets, which initially exhibit a high instantaneous peak concentration, are important factors in direct infection. Most infections occur when a large number of droplets are directly transmitted to a person [38]. Therefore, the peak concentration is considered one of the most influential factors in SARS-CoV-2 spread.

2.3.2. Loss rate

To understand the degree of infection through the air, we should consider the loss rate, which decreases over time. The concentration of indoor particulate matter is reduced through the diffusion or gravitational deposition of particles. The particle loss rate is defined as the rate at which the particle concentration decreases. The particle loss rate varies depending on the particle characteristics, including its diameter and composition, and on indoor environmental factors, such as the air temperature, relative humidity, and airflow velocity. In this study, we analyzed the possibility of infection based on the particle reduction rate because we focused on the particles that are diffused by the airflow generated through the operation of an air conditioner. A first-order mass conservation equation was used to calculate the particle concentration reduction rate [39].

| (1) |

where is the indoor particle concentration (μg/m3), is the outdoor air concentration (μg/m3), P is the penetration factor, A is the air exchange rate (h−1), K is the deposition rate (decay rate)(h−1), E is the emission rate (μg/h), V is the volume of the room (m3), and t is the time (h).

The particle loss rate (L) is the sum of the infiltration (A) and deposition (K) and can be calculated using Equation (2), which is derived from Equation (1).

| (2) |

where, is the indoor background particle concentration before measurement (μg/m3) and is the particle concentration in the beginning of the decay period. The unit of the loss rate (L) is h−1.

2.4. Experimental setup

2.4.1. Equipment setting

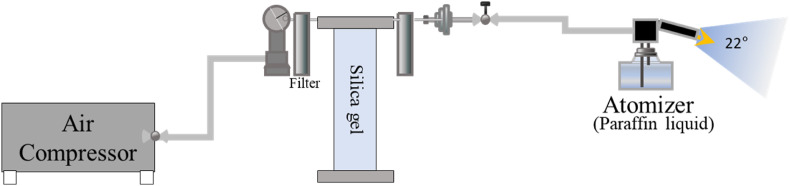

Fig. 2 shows the layout of the particle generator used to discharge droplet particles. The humid and dusty air of the atmosphere was purified into dry and pure air as it passed through the filter and silica gel, as induced by the air compressor. In these experiments, it was important to use the same droplet emission amount for different experimental cases. Therefore, the pressure at the time of discharge was maintained constant (2 bar). By ensuring that the injection time was constant, we could ensure that the particle injection amount was the same for each experiment. For this injection test method, we referred to the method by Mousavi et al. [18]. The particle concentration was intentionally increased to 400 μg/m3, in contrast to the 5 μg/m3 background concentration. Paraffin liquid was sprayed in the form of droplets as it passed through the atomizer. It was sprayed from a height of 1.2 and 1.6 m, to simulate the cases when the infected person is sitting or standing, respectively. In addition, to simulate a sneeze, the ejection angle was set to 22° [40].

Fig. 2.

Layout of the particle generator.

Table 2 lists the equipment used in the experiment. TSI-8530 and OPS3330 were used to measure the droplet concentration; TSI-8530 was used to measure the particle mass concentration. It is mainly used to measure the PM10 and PM2.5, and the resulting measurements have high accuracy [41]. OPS3330 was used to measure the particle number concentration. This instrument enables the accurate measurement of the particle concentration and size distribution using optical particle size measurement technology [42]. TESTO-400 was used to measure the predictive mean vote (PMV) elements of the laboratory (temperature, humidity, air speed, and radiation temperature). A low-cost air purifier commonly used worldwide was used. This product has a particle clean air delivery rate (CADR) of up to 500 m³/h, an effective area of 60 m2, and uses a HEPA filter.

Table 2.

Laboratory measurement devices used.

| Device name images | Basic principle and condition | Device name images | Basic principle and condition |

|---|---|---|---|

TSI-8530 |

TSI-8530 was used to measure the particle mass concentration. It is mainly used to measure PM10 and PM2.5 and its measurements have high accuracy. |

OPS3330 |

OPS3330 was used to measure the particle number concentration. It enables the accurate measurement of the particle concentration and size distribution using optical particle counting technology. |

TESTO-400

|

Identifies the PMV elements in the laboratory (temperature, humidity, air speed, and radiation temperature). | Portable air purifier

|

This product has a particle CADR of up to 500 m³/h. |

| It has an effective area of 60 m2. | |||

| A HEPA filter was used. |

2.4.2. Environment setup

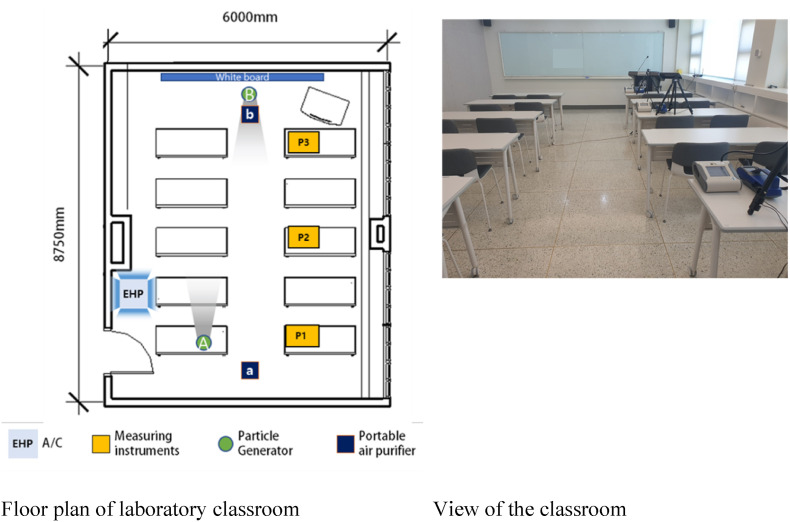

The experiment was conducted from July 27 to September 1, 2021, at a university classroom in Seoul, Korea, during a hot summer with an average outdoor temperature of 28 °C ± 3 °C. The room dimensions were 6 × 8.75 × 2.8 m, and it was designed to accommodate 20–30 students. Fig. 3 shows the scene and equipment conditions used in the experiment.

Fig. 3.

Experimental setup and sampling location.

First, the airtightness performance of the room, which greatly affects the indoor air environment, was analyzed by performing a blower-door depressurization test. Measurements were performed according to the procedures of the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) E779:2010 and ISO9972:Europe (2016), using Retrotec 6100 (Retrotec, Everson, WA, USA) equipment. When the pressure difference between the room and the outdoor space was 50 Pa, the air change per hour (ACH)_50 was 23. This value is lower than that observed in most classrooms in this university [43]. This is due to the age of the windows of this classroom, which increases the amount of air that penetrates the room from the outside, resulting in a low airtightness performance.

An electric heat pump (EHP) installed on the ceiling of the classroom was used for cooling. The room temperature was set to 25 °C, and the EHP was operated in weak wind mode. The air volume was set to 8 m3/min cubic meter per minutes (CMM). The EHP was operated identically in all experiments. The measurements were performed in three measurement points: in the back (Point 1; P1), middle (P2), and front of the classroom (P3), as shown in Fig. 3. Particles were generated at rear Point A, which simulates the case in which an infected student is sitting in the back of the classroom, and at Point B, which simulates the case in which the teacher, who stands in the front of the classroom, is infected. A portable air purifier was placed in the back (a) or front (b).

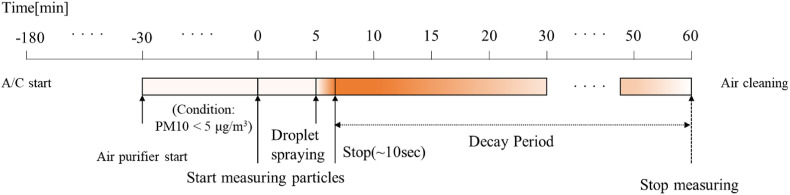

2.4.3. Experimental procedure

Fig. 4 shows the schedule used for the particle-release experiment. The EHP (A/C) was turned on 3 h before the measurements to set the indoor temperature to 25 °C ± 2 °C. The air purifier was operated for more than 30 min, so that the initial PM10 concentration in each experiment was 5 μg/m3 or less. The particle concentration measurements started, the background concentration was measured for 5 min, and then particles were generated for 10 s. The particle concentration was measured every 30 s, and the measurements were terminated 1 h after the particle generation started.

Fig. 4.

Measurement schedule used in the droplet dispersion experiments.

2.5. Experimental cases

Table 3 summarizes the conditions of the experimental cases simulated in this study, including the use of an air purifier, the droplet generation location, the air purifier location, and the air purifier flow rate. For each case, the experiment was performed 2–3 times. The experimental results are presented as mean values. The flow rate of the air purifier was approximately 109 cubic meters per hour (CMH) in low mode and 500 CMH in high mode, which correspond to 0.74 and 3.4 ACH, respectively.

Table 3.

Experimental cases.

| Case | Air purifier (Yes/No) | Particle generator location | Air purifier location | Air purifier flow rate Low mode (109 CMH), High mode (500 CMH) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | No | – | – | |

| 1–1 | Yes | A | a | Low mode |

| 1–2 | High mode | |||

| 1–3 | b | Low mode | ||

| 1–4 | High mode | |||

| 2 | No | – | – | |

| 2–1 | Yes | B | a | Low mode |

| 2–2 | High mode | |||

| 2–3 | b | Low mode | ||

| 2–4 | High mode |

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Indoor airflow evaluation

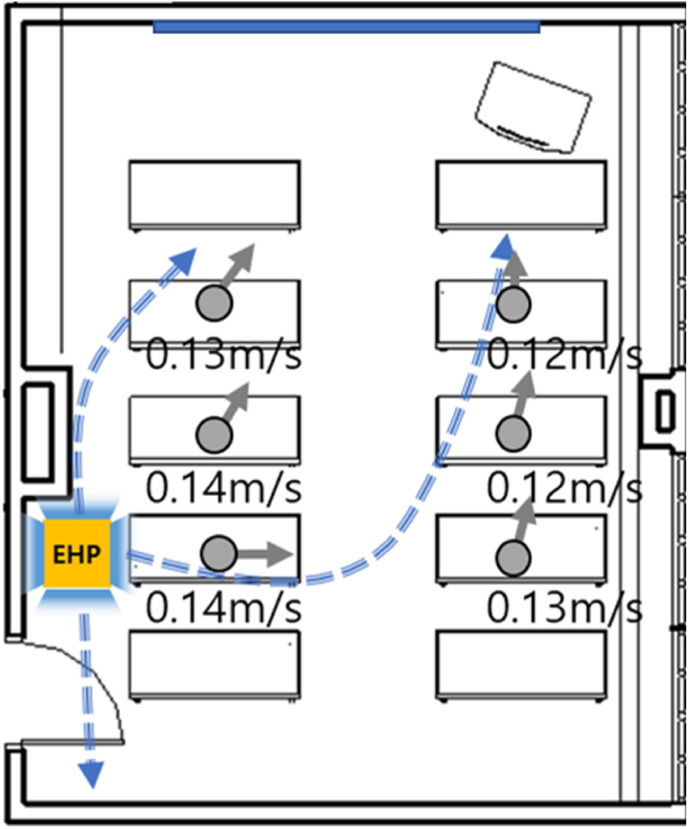

The movement and diffusion of droplets are mainly affected by the indoor airflow. Therefore, for a more rational analysis, we measured the indoor wind speed and the direction of the airflow generated by the EHP. The airflow wind speed was measured using a Testo 400 instrument. Wind direction was measured using a small smoke generator. The measurement was performed at a height of 1.2 m. Fig. 5 illustrates the airflow and wind speed in the room. The wind speed was very low (0.12–0.14 m/s). The cold air generated by the EHP was discharged in four directions. Because the EHP was installed at the rear of the classroom, the overall direction of the airflow was from the rear to the front of the classroom.

Fig. 5.

Classroom airflow produced by the EHP.

3.2. Concentration change according to the particle generation location

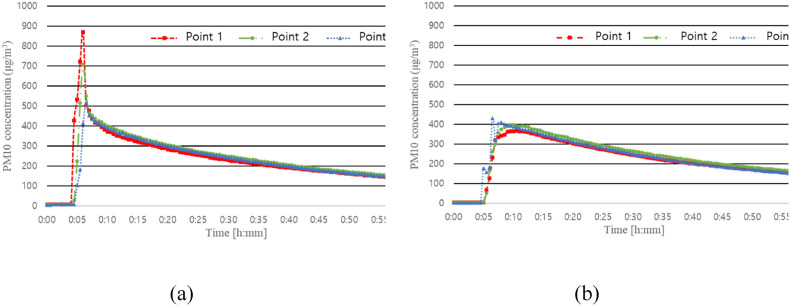

Fig. 6 shows the changes in concentration according to the particle generation location in the cases in which an air purifier was not used. In Cases 1 and 2, the particle generation location was (A) and (B), respectively.

Fig. 6.

Differences in PM10 concentration according to the particle generation location. (a) Case 1: Particle generator location A with no air purifier; (b) Case 2: Particle generator location B with no air purifier.

The peak concentration in Case 1 was 871, 707, and 515 μg/m3 at Points 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The peak concentration value at Point 1, which is the point closest to the location of the particle generator, was the highest. Due to the airflow created by the EHP, as the distance from location (A) increases, the droplets sink more and the peak concentration decreases. In Case 2, because the direction of the indoor airflow derived from the EHP opposes the direction of particle ejection, even if a large concentration of particles is generated at the beginning, the particles immediately mix with the air, and a peak concentration changing trend according to the measurement location could not be clearly observed. However, the decay trend was similar to that observed in Case 1.

3.3. Comparison of the peak concentrations

As mentioned earlier, the peak concentration observed in the early stages of droplet generation was closely related to direct human-to-human infections. To compare the degree of direct infection in each case, the peak concentration values measured in the experiments were compared. Table 4 shows the rate of increase in the peak concentration for each case, according to the particle generation location. The peak concentration increase rate was calculated based on the concentrations measured in Cases 1 and 2.

Table 4.

Comparison of the average PM10 mass peak concentration by location.

| Average peak concentration (μg/m³) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Point 1 | Point 2 | Point 3 | ||||||||

| Case |

Setting (Particle generator location, Air purifier location, Air purifier mode) |

Base peak concentration (A) |

Average peak concentration (B) |

Rate of increase (A/B-1) × 100 |

Base peak concentration (A) |

Average peak concentration (B) |

Rate of increase (A/B-1) × 100 |

Base peak concentration (A) |

Average peak concentration (B) |

Rate of increase (A/B-1) × 100 |

| 1 (Base) | A--(No purifier) | 871 |

871 | 0% | 707 |

707 | 0% | 515 |

515 | 0% |

| 1-1 | A, a, Low | 905 | 4% | 579 | −18% | 439 | −15% | |||

| 1-2 | A, a, High | 990 | 14% | 410 | −42% | 381 | −26% | |||

| 1-3 | A, b, Low | 1,345 | 54% | 956 | 35% | 480 | −7% | |||

| 1-4 |

A, b, High |

1,460 |

68% |

1260 |

78% |

886 |

72% |

|||

| 2 (Base) | B--(No purifier) | 368 | 368 | 0% | 399 | 399 | 0% | 432 | 432 | 0% |

| 2-1 | B, a, Low | 394 | 7% | 429 | 7% | 670 | 55% | |||

| 2-2 | B, a, High | 397 | 8% | 494 | 24% | 1,630 | 278% | |||

| 2-3 | B, b, Low | 330 | −11% | 404 | 1% | 621 | 44% | |||

| 2-4 | B, b, High | 353 | −4% | 381 | −4% | 360 | −17% | |||

The base peak concentration refers to the values of cases 1 and 2, without the use of air purifiers.

3.3.1. Particle generation location: A (location of the infected student)

-

(1)

When the air purifier was located in “a” (Cases 1, 1-1, and 1-2)

In this situation, the “infected student” sits in the back of the classroom, and the air purifier is located in the back of the classroom, close to the “infected student”. The change in particle concentration according to the volume of air derived from the air purifier was analyzed (Case 1-1 vs. Case 1-2). When the air purifier air volume increases, the amount of droplets collected in the filter increases; however, the initial peak concentration may appear rather high near the air purifier due to the strong air current that it generates.

As shown in Table 4, when the air purifier was placed at Point 1, the peak concentration increased by 4% and 14% in the low and high modes, respectively. However, when located at Points 2 and 3, the peak concentration decreased by 18% and 42%, and by 15% and 26%, respectively. This means that, at Point 1, which is close to the location of particle generation, the peak concentration was affected by the airflow generated by the air purifier, whereas at Points 2 and 3, the air purifier directly removed the particles, thus decreasing the peak concentration.

-

(2)

When the air purifier is located in the front of the classroom (b) (comparison of Cases 1, 1-3, and 1-4)

When the air purifier was installed in the front of the classroom (b), the peak concentration was higher at Points 1, 2, and 3 than in Case 1 (P1: 871, P2: 707, and P3: 515), in which no air purifier was used. These results show that, in Case 1, the droplets generated at position A, high mode, sank approximately 1 m away from the location of particle generation. Conversely, in Case 1-3, since the air purifier was operated in low mode, the high-density droplets spread up to Points 1 and 2, and the peak concentration increased by 54% and 35%, respectively, compared to those in Case 1. The power of the low mode is weak. Therefore, the particles spread up to Point 3; however, the corresponding peak concentration was reduced by 7% since some droplets were removed by the filter. These results show that the use of air purifiers can increase the degree of direct infection, similar to the aforementioned research results by Ham [20]. More specifically, this experiment shows that according to the particle generation location, the air purifier location can help induce an airflow in a direction that promotes diffusion, and the initial peak concentration can increase up to a certain distance, depending on the mode of operation of the air purifier. In Case 1-4, the peak concentration was increased by 68%, 78%, and 72% at Points 1, 2, and 3, respectively, because the air purifier was operated in the high mode and a large pulling force was exerted on the droplets.

3.3.2. Particle generation location: B (location of the infected teacher)

-

(1)

When the air purifier is located in (a) (comparison of Cases 2, 2-1, and 2-2)

When the particle generator is at position B and the air purifier is located at (a), for both Cases 2-1 and 2-2, in which the air purifier was operated in low and high mode, respectively, a higher peak concentration was measured in Points 1–3, compared to those in Case 2, in which no air purifier was used. This result may be explained by the fact that, as in the previous section, the spread of droplets increases when the droplet generation location and the air purifier location are far from each other. In particular, in Case 2-2, the peak concentration increased by 278% in Point 3. The absolute value measured in this case was also the highest (1,630 μg/m3), indicating that the probability of infection would be high if this were a real situation.

-

2)

When the air purifier is located in (b) (comparison of Cases 2, 2-3, and 2-4)

The peak concentration decreased substantially at all points. This appears to be because the generated droplets were directly removed by the air purifier that was located within a short distance. Nevertheless, in Point 3, the peak concentration increased in some cases when the air purifier was operated in the low mode. This appears to be an exceptional phenomenon of this experiment, in which the peak concentration was affected by the updraft induced by the air purifier. The air purifier was effective in reducing the peak concentration when the droplet generator was near the air purifier. These results are similar to those obtained by Mousavi et al. [18] which showed that the optimal air purifier location is near the infected person in an enclosed space.

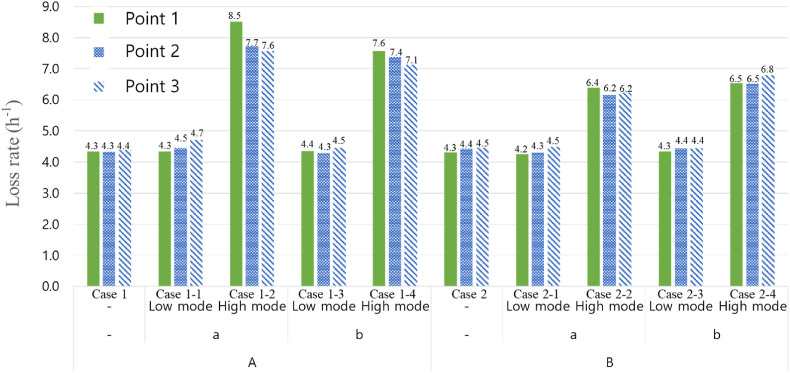

3.4. Loss rate

3.4.1. Evaluation of reduction rate based on PM10

The loss rate is an indicator of how quickly the number of droplets in the air is reduced. If the loss rate is high, the droplet reduction rate in the air is higher, and thus, the likelihood of airborne infection is reduced. Conversely, if the loss rate is low, the likelihood of airborne infection increases. The loss rates for all measurement locations and for all cases are shown in Fig. 7 . In Cases 1 and 2, in which no air purifier was used, the loss rate was approximately 4.41 h−1, and no significant difference, according to the particle generation and measurement location, was observed. This is because the particles generated by the indoor airflow induced by the EHP were relatively well mixed with the air.

Fig. 7.

Comparison of the PM10 mass concentration loss rate between cases.

In Cases 1-1, 1-3, 2-1, and 2-3, in which the air purifier is operated in low mode (109 CMH), an average loss rate of 4.5 h−1 was observed. This is not a significant improvement compared with that of Cases 1 and 2, in which no air purifier was used. These results may be due to the low airtightness performance of the classroom used in the experiment; the concentration reduction induced by infiltration seemed to be higher than that induced by the air purifier operated in low mode.

In Cases 1-2, 1-4, 2-2, and 2-4, in which the air purifier was operated in high mode (500 CMH), the average loss rate increased significantly to 7.0 h−1 compared to those in Cases 1 and 2. These results indicate that increasing the air volume of the air purifier can reduce the number of airborne droplets and the airborne infections through the air. No significant differences were observed between the values obtained for different measurement points, and this may be because the particles were well mixed throughout the room by the EHP and the air purifier.

3.4.2. Loss rate by particle size

Table 5 summarizes the loss rates according to the generated particle size for each case. As discussed in the Introduction, the particle size threshold that distinguishes the droplets from droplet nuclei is 5 mm. In the experiment, the particles with a size of 0.3–5 mm were classified as droplet nuclei and those with a size of 5–10 mm were classified as droplets. The loss rate was low (approximately 5.4 h−1) for a particle size range of 0.3–0.5 mm, and 8.4 h−1 (54% higher than the former) for a particle size range of 5–10 mm. This is because heavier droplets sink faster because of gravity.

Table 5.

Comparison of the particle number concentration loss rate by case according to the PM0.3–5 and PM5-10 values.

| Case | Loss rate (h−1) |

Average | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Point 1 |

Point 2 |

Point 3 |

|||||

| Size:0.3–5 μm | Size:5–10 μm | Size:0.3–5 μm | Size:5–10 μm | Size:0.3–5 μm | Size:5–10 μm | ||

| 1 | 4.3 | 6.9 | 4.4 | 7 | 4.2 | 5.9 | 5.5 |

| 1–1 | 4.4 | 6.8 | 4.5 | 12.5 | 4.3 | 7.6 | 6.7 |

| 1–2 | 8.8 | 7 | 7.6 | 6.9 | 7.9 | 7.3 | 7.6 |

| 1–3 | 4.2 | 8.6 | 4.2 | 6.6 | 4.2 | 9.7 | 6.3 |

| 1–4 | 7 | 10.6 | 7 | 6.5 | 7 | 13.5 | 8.6 |

| Average | 5.7 | 8.0 | 5.5 | 7.9 | 5.5 | 8.8 | 6.9 |

| 2 | 4.4 | 7.9 | 4.5 | 6.4 | 4.3 | 6.6 | 5.7 |

| 2–1 | 4.2 | 9.4 | 4.4 | 8.7 | 4.3 | 9.9 | 6.8 |

| 2–2 | 6.6 | 7.1 | 6.2 | 13.0 | 6.3 | 6.9 | 7.7 |

| 2–3 | 4.3 | 7.4 | 4.5 | 7.0 | 4.6 | 9.4 | 6.2 |

| 2–4 | 6.5 | 10.1 | 7.0 | 8.2 | 6.8 | 9.9 | 8.1 |

| Average | 5.2 | 8.4 | 5.3 | 8.7 | 5.3 | 8.5 | 6.9 |

The loss rates based on the airflow volume of the air purifier are summarized in Table 6 . When the air purifier was operated in low mode, the loss rate increase rate of the droplet nuclei was 1%, which is almost ineffective. However, an increase rate of approximately 19% was observed for droplets. This means that even if the air volume released from the air purifier is low, the number of droplets containing a high viral load can be reduced. When the air purifier was operated in high mode, for which the air volume was 500 CMH, the loss rate increased significantly. In the case of droplet nuclei, it increased by 39%, whereas in the case of droplets, it increased by 22%.

Table 6.

Comparison of the particle number concentration loss rate according to the air purifier intensity based on the PM0.3–5 and PM5-10 values.

| Size: 0.3–5 μm |

Size: 5–10 μm |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loss rate (h−1) | Rate of increase (A/B-1) × 100 | Loss rate (h−1) | Rate of increase (A/B-1) × 100 | |

| No air purifier (A) | 4.3 | – | 7.0 | – |

| Air purifier in low mode (B) | 4.34 | −1.0% | 8.6 | −19% |

| Air purifier in high mode (B) | 7.1 | −39% | 8.9 | −22% |

Overall, using the air purifier in the low mode did not significantly affect the loss rate compared with using it in the high mode. The effect of infiltration was relatively greater than that of the air purifier, because the airtightness performance of the classroom was weak. As a result, in the case of a classroom with a poor airtightness performance, if the air volume of the air purifier is insufficient compared to the amount of infiltration, the air infection suppressing effect by operating an air purifier may be insignificant. However, an air infection suppression effect was clearly observed when the air purifier was operated in high mode, for which the air volume of the air purifier was sufficient compared to the amount of infiltration.

This experiment was conducted in an unoccupied classroom. According to Murakami et al. [44], indoor airflow can change under the influence of heat emitted by the human body. Taking this into account, the results presented in this study may differ from those in the presence of actual residents. Nevertheless, since the heat emitted by the human body cannot change the main airflow itself, the error, according to the air volume and location of the air purifier, is deemed sufficiently low to be acceptable to infer meaningful conclusions.

4. Discussion

Based on our results, we concluded that placing an infected person near an air purifier is an effective method to prevent the aerial dispersion of droplets including viral particles. If so, the question remains about how to actually reduce the dispersion of COVID-19 in a classroom setting. To solve this problem, we think additional efforts should be made to identify asymptomatic infected people. To this end, it is recommended to appropriately gather people who have come into close contact with infected persons or early fever generators near the air purifier. However, these measures should be accompanied by social understanding and consultation.

5. Conclusions

To evaluate whether the use of an air purifier affects droplet diffusion, repeated experiments were conducted by studying ten experimental cases that differed in terms of the location of droplet generation, the location of the air purifier, and air purifier intensity (air volume).

From the experimental results, the following conclusions can be drawn. The peak concentration, which can determine the degree of direct infection, decreased by 42% or increased by 278%, depending on the location of the air purifier. We found that these disparate results were due to how the air purifier changed the airflow in the classroom. When the air purifier was operated in the low mode, the loss rate of droplet nuclei, which can be used to evaluate the likelihood of airborne infection, did not improve significantly. Nevertheless, the loss rate increased by 19% for the droplets (approximate particle size: 5–10 mm). However, when the air volume was increased (when the air purifier was operated in the high mode), the reduction efficiency was as high as 39% and 22% for droplet nuclei and droplets, thus affecting the likelihood of indirect airborne and direct infection, respectively.

Based on reports, the airflow induced by the EHP and air purifiers greatly affects the possibility of COVID-19 infection. Air purifiers can reduce the concentration of droplets, which may contain viruses, due to their filter; however, they can also spread the droplets further, due to the airflow that they induce. To reduce the COVID-19 group infections, understanding the airflow movement in a room caused by the EHP and air purifier, and to properly place the air purifier is essential.

In this study, we analyzed the spread of droplets in a classroom under specific conditions. Therefore, the generalizability of the effects of the EHP and air purifiers to other classrooms is somewhat limited. Nevertheless, through the analysis of various cases, our results will hopefully help relieve the fear around the use of air purifiers and air conditioners and elucidate their impact on the spread of COVID-19.

Funding

This work was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT, MOE) [grant number 2019M3E7A1113095]. The funder had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Hoo Seung Na: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Project administration, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Hyungkeun Kim: Methodology, Conceptualization. Taeyeon Kim: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage for providing language assistance and proofreading services to enhance the quality of this manuscript.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., Zhu F., Liu X., Zhang J., Wang B., Xiang H., Cheng Z., Xiong Y.J.J., Zhao Y., Li Y., Wang X., Peng Z. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asadi S., Bouvier N., Wexler A.S., Ristenpart W.D. The coronavirus pandemic and aerosols: does COVID-19 transmit via expiratory particles? Aerosol Sci. Technol. 2020;54:1–4. doi: 10.1080/02786826.2020.1749229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li C., Ji F., Wang L., Wang L., Hao J., Dai M., Liu Y., Pan X., Fu J., Li L.J.E.i.d., Yang G., Yang J., Yan X., Gu B. Asymptomatic and human-to-human transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in a 2-family cluster, Xuzhou, China, Emerg. Inf. Disp. 2020;26:1626–1628. doi: 10.3201/eid2607.200718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Song R., Han B., Song M., Wang L., Conlon C.P., Dong T., Tian D., Zhang W., Chen Z., Zhang F., Shi M., Li X. Clinical and epidemiological features of COVID-19 family clusters in Beijing, China. J. Infect. 2020;81 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.018. e26–e30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wrapp D., Wang N., Corbett K.S., Goldsmith J.A., Hsieh C.L., Abiona O., Graham B.S., McLellan J.S.J.S. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science. 2020;367:1260–1263. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liao L., Xiao W., Zhao M., Yu X., Wang H., Wang Q., Chu S., Cui Y.J.A.n. Can N95 respirators be reused after disinfection? How many times? ACS Nano. 2020;14:6348–6356. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c03597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prather K.A., Wang C.C., Schooley R.T.J.S. Reducing transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Science. 2020;368:1422–1424. doi: 10.1126/science.abc6197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shen Y., Li C., Dong H., Wang Z., Martinez L., Sun Z., Handel A., Chen Z., Chen E., Ebell M., Wang F., Yi B., Wang H., Wang X., Wang A., Chen B., Qi Y., Liang L., Li Y., Ling F., Chen J., Xu G. Airborne transmission of COVID-19: epidemiologic evidence from two outbreak investigations. SSRN Journal. 2020 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3567505. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu J., Gu J., Li K., Xu C., Su W., Lai Z., Zhou D., Yu C., Xu B., Yang Z.J.E.i.d. COVID-19 outbreak associated with air conditioning in restaurant, Guangzhou, China, 2020. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;26:1628–1631. doi: 10.3201/eid2607.200764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh R., Dewan A.J.C.S. Rethinking use of individual room air-conditioners in view of COVID 19. Creat. Sp. 2020;8:15–20. doi: 10.15415/cs.2020.81002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oh H.-J., Nam I.-S., Yun H., Kim J., Yang J., Sohn J.-R.J.B. Characterization of indoor air quality and efficiency of air purifier in childcare centers, Korea, Build. Environ. Times. 2014;82:203–214. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2014.08.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pei J., Dong C., Liu J.J.B. Operating behavior and corresponding performance of portable air cleaners in residential buildings, China, Build. Environ. Times. 2019;147:473–481. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2018.08.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng Y.S., Lu J.C., Chen T.R.J.A.S. Efficiency of a portable indoor air cleaner in removing pollens and fungal spores. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 1998;29:92–101. doi: 10.1080/02786829808965554. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rao N.G., Kumar A., Wong J.S., Shridhar R., Goswami D.Y.J.A. Effect of a novel photoelectrochemical oxidation air purifier on nasal and ocular allergy symptoms. Allergy Rhinol. (Providence) 2018;9 doi: 10.1177/2152656718781609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu D.T., Phillips K.M., Speth M.M., Besser G., Mueller C.A., Sedaghat A.R. Portable HEPA purifiers to eliminate airborne SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2022;166:615–622. doi: 10.1177/01945998211022636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao B., An N., Chen C. Using an air purifier as a supplementary protective measure in dental clinics during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2021;42:493. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen C., Zhao B., Cui W., Dong L., An N., Ouyang X. The effectiveness of an air cleaner in controlling droplet/aerosol particle dispersion emitted from a patient's mouth in the indoor environment of dental clinics. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2010;7:1105–1118. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2009.0516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mousavi E.S., Godri Pollitt K.J., Sherman J., Martinello R.A. Performance analysis of portable HEPA filters and temporary plastic anterooms on the spread of surrogate coronavirus. Build. Environ. 2020;183 doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.107186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . CDC; USA: 2020. Interim Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Patients with Suspected or Confirmed Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Healthcare Settings. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ham S.J.E. Prevention of exposure to and spread of COVID-19 using air purifiers: challenges and concerns. Epidemiol. Health. 2020;42 doi: 10.4178/epih.e2020027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hinds W.C. John Wiley & Sons; 1999. Aerosol Technology: Properties, Behavior, and Measurement of Airborne Particles. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., Qu J., Gong F., Han Y., Qiu Y., Wang J., Liu Y., Wei Y., Xia J., Yu T., Zhang X., Zhang L. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Netz R.R. Mechanisms of airborne infection via evaporating and sedimenting droplets produced by speaking. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2020;124:7093–7101. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.0c05229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.W.H.O . 2014. Infection Prevention and Control of Epidemic-And Pandemic-Prone Acute Respiratory Infections in Health Care.https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/112656 (accessed 2022.December.2002) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindsley W.G., Reynolds J.S., Szalajda J.V., Noti J.D., Beezhold D.H.J.A.S. A cough aerosol simulator for the study of disease transmission by human cough-generated aerosols. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 2013;47:937–944. doi: 10.1080/02786826.2013.803019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pica N., Bouvier N.M. Environmental factors affecting the transmission of respiratory viruses. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2012;2:90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2011.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bourouiba L., Dehandschoewercker E., Bush J. Violent expiratory events: on coughing and sneezing. J. Fluid Mech. 2014;745:537–563. doi: 10.1017/jfm.2014.88. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fernstrom A., Goldblatt M. Aerobiology and its role in the transmission of infectious diseases. J. Pathog. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/493960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chinn R.Y., Sehulster L. CDC; USA: 2003. Guidelines for Environmental Infection Control in Health-Care Facilities; Recommendations of CDC and Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shen Y., Li C., Dong H., Wang Z., Martinez L., Sun Z., Handel A., Chen Z., Chen E., Ebell M.H., Wang F., Yi B., Wang H., Wang X., Wang A., Chen B., Qi Y., Liang L., Li Y., Ling F., Chen J., Xu G. Community outbreak investigation of SARS-CoV-2 transmission among bus riders in eastern China. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020;180:1665–1671. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.5225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nissen K., Krambrich J., Akaberi D., Hoffman T., Ling J., Lundkvist Å., Svensson L., Salaneck E. Long-distance airborne dispersal of SARS-CoV-2, in COVID-19 wards. Sci. Rep. 2020;10 doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-76442-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Han B., Kim S., Lee G., Hong G., Park I., Kim H., Lee Y., Kim Y., Jeong S., Shim S., Kim J., Roh S., Min T., Shin W. Analysis on applicability of air purifiers in schools to prevent the spread of airborne infection of Sars-CoV-2. J. Korean Soc. Atmos. Environ. 2020;36:832–840. doi: 10.5572/KOSAE.2020.36.6.832. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chaudhuri S., Basu S., Kabi P., Unni V.R., Saha A. Modeling the role of respiratory droplets in Covid-19 type pandemics. Phys. Fluids. 1994;32(2020) doi: 10.1063/5.0015984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou S.S., Lukula S., Chiossone C., Nims R.W., Suchmann D.B., Ijaz M.K. Assessment of a respiratory face mask for capturing air pollutants and pathogens including human influenza and rhinoviruses. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018;10:2059–2069. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.03.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiang J., Zhang H., He W., Li T., Li H., Liu P., Liu M., Wang Z., Wang Z., Yao X. Adhesion of microdroplets on water-repellent surfaces toward the prevention of surface fouling and pathogen spreading by respiratory droplets. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017;9:6599–6608. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b15213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kulmala I., Heinonen K., Salo S. Improving filtration efficacy of medical face masks. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2021;21 doi: 10.4209/aaqr.210043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jung H., Kim J.K., Lee S., Lee J., Kim J., Tsai P., Yoon C. Comparison of filtration efficiency and pressure drop in anti-yellow sand masks, quarantine masks, medical masks, general masks, and handkerchiefs. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2014;14:991–1002. doi: 10.4209/aaqr.2013.06.0201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ge Z.Y., Yang L.M., Xia J.J., Fu X.H., Zhang Y.Z. Possible aerosol transmission of COVID-19 and special precautions in dentistry. J. Zhejiang Univ. - Sci. B. 2020;21:361–368. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B2010010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen C., Zhao B. Review of relationship between indoor and outdoor particles: I/O ratio, infiltration factor and penetration factor, Atmos. Environ. Times. 2011;45:275–288. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.09.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gupta J.K., Lin C.H., Chen Q.J.I.a. Flow dynamics and characterization of a cough. Indoor Air. 2009;19:517–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2009.00619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chatoutsidou S.E., Ondráček J., Tesar O., Tørseth K., Ždímal V., Lazaridis M.J.B. Indoor/outdoor particulate matter number and mass concentration in modern offices. Build. Environ. 2015;92:462–474. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2015.05.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Workman A.D., Xiao R., Feng A., Gadkaree S.K., Quesnel A.M., Bleier B.S., Scangas G.A. Suction mitigation of airborne particulate generated during sinonasal drilling and cautery. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2020;10:1136–1140. doi: 10.1002/alr.22644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eom Y.S., Park B.R., Kim S.G., Kang D.H. A case study on placement of portable air cleaner considering outdoor particle infiltration into an elementary school classroom. J. KIAEBS. 2020;14:158–170. doi: 10.22696/JKIAEBS.20200015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murakami S., Kato S., Zeng J. Combined simulation of airflow, radiation and moisture transport for heat release from a human body. Build. Environ. 2000;35:489–500. doi: 10.1016/S0360-1323(99)00033-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.