Abstract

Background

Communication problems in health care may arise as a result of healthcare providers focusing on diseases and their management, rather than people, their lives and their health problems. Patient‐centred approaches to care delivery in the patient encounter are increasingly advocated by consumers and clinicians and incorporated into training for healthcare providers. However, the impact of these interventions directly on clinical encounters and indirectly on patient satisfaction, healthcare behaviour and health status has not been adequately evaluated.

Objectives

To assess the effects of interventions for healthcare providers that aim to promote patient‐centred care (PCC) approaches in clinical consultations.

Search methods

For this update, we searched: MEDLINE (OvidSP), EMBASE (OvidSP), PsycINFO (OvidSP), and CINAHL (EbscoHOST) from January 2000 to June 2010. The earlier version of this review searched MEDLINE (1966 to December 1999), EMBASE (1985 to December 1999), PsycLIT (1987 to December 1999), CINAHL (1982 to December 1999) and HEALTH STAR (1975 to December 1999). We searched the bibliographies of studies assessed for inclusion and contacted study authors to identify other relevant studies. Any study authors who were contacted for further information on their studies were also asked if they were aware of any other published or ongoing studies that would meet our inclusion criteria.

Selection criteria

In the original review, study designs included randomized controlled trials, controlled clinical trials, controlled before and after studies, and interrupted time series studies of interventions for healthcare providers that promote patient‐centred care in clinical consultations. In the present update, we were able to limit the studies to randomized controlled trials, thus limiting the likelihood of sampling error. This is especially important because the providers who volunteer for studies of PCC methods are likely to be different from the general population of providers. Patient‐centred care was defined as a philosophy of care that encourages: (a) shared control of the consultation, decisions about interventions or management of the health problems with the patient, and/or (b) a focus in the consultation on the patient as a whole person who has individual preferences situated within social contexts (in contrast to a focus in the consultation on a body part or disease). Within our definition, shared treatment decision‐making was a sufficient indicator of PCC. The participants were healthcare providers, including those in training.

Data collection and analysis

We classified interventions by whether they focused only on training providers or on training providers and patients, with and without condition‐specific educational materials. We grouped outcome data from the studies to evaluate both direct effects on patient encounters (consultation process variables) and effects on patient outcomes (satisfaction, healthcare behaviour change, health status). We pooled results of RCTs using standardized mean difference (SMD) and relative risks (RR) applying a fixed‐effect model.

Main results

Forty‐three randomized trials met the inclusion criteria, of which 29 are new in this update. In most of the studies, training interventions were directed at primary care physicians (general practitioners, internists, paediatricians or family doctors) or nurses practising in community or hospital outpatient settings. Some studies trained specialists. Patients were predominantly adults with general medical problems, though two studies included children with asthma. Descriptive and pooled analyses showed generally positive effects on consultation processes on a range of measures relating to clarifying patients' concerns and beliefs; communicating about treatment options; levels of empathy; and patients' perception of providers' attentiveness to them and their concerns as well as their diseases. A new finding for this update is that short‐term training (less than 10 hours) is as successful as longer training.

The analyses showed mixed results on satisfaction, behaviour and health status. Studies using complex interventions that focused on providers and patients with condition‐specific materials generally showed benefit in health behaviour and satisfaction, as well as consultation processes, with mixed effects on health status. Pooled analysis of the fewer than half of included studies with adequate data suggests moderate beneficial effects from interventions on the consultation process; and mixed effects on behaviour and patient satisfaction, with small positive effects on health status. Risk of bias varied across studies. Studies that focused only on provider behaviour frequently did not collect data on patient outcomes, limiting the conclusions that can be drawn about the relative effect of intervention focus on providers compared with providers and patients.

Authors' conclusions

Interventions to promote patient‐centred care within clinical consultations are effective across studies in transferring patient‐centred skills to providers. However the effects on patient satisfaction, health behaviour and health status are mixed. There is some indication that complex interventions directed at providers and patients that include condition‐specific educational materials have beneficial effects on health behaviour and health status, outcomes not assessed in studies reviewed previously. The latter conclusion is tentative at this time and requires more data. The heterogeneity of outcomes, and the use of single item consultation and health behaviour measures limit the strength of the conclusions.

Keywords: Humans, Decision Making, Health Behavior, Medical Staff, Medical Staff/education, Medicine, Nursing Staff, Nursing Staff/education, Patient Participation, Patient Satisfaction, Patient‐Centered Care, Patient‐Centered Care/methods, Physician‐Patient Relations, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Training healthcare providers to be more 'patient‐centred' in clinical consultations

Problems may arise when healthcare providers focus on managing diseases rather than on people and their health problems. Patient‐centred approaches to care delivery in the patient encounter are increasingly advocated by consumers and clinicians and incorporated into training for healthcare providers. We updated a 2001 systematic review of the effects of these training interventions for healthcare providers that aim to promote patient‐centred care in clinical consultations.

We found 29 new randomized trials (up to June 2010), bringing the total of studies included in the review to 43. In most of the studies, training interventions were directed at primary care physicians (general practitioners, internists, paediatricians or family doctors) or nurses practising in community or hospital outpatient settings. Some studies trained specialists. Patients were predominantly adults with general medical problems, though two studies included children with asthma.

These studies showed that training providers to improve their ability to share control with patients about topics and decisions addressed in consultations are largely successful in teaching providers new skills. Short‐term training (less than 10 hours) is as successful in this regard as longer training. Results are mixed about whether patients are more satisfied when providers practice these skills. The impact on general health is also mixed, although the limited data that could be pooled showed small positive effects on health status. Patients' specific health behaviours show improvement in the small number of studies where interventions use provider training combined with condition‐specific educational materials and/or training for patients, such as teaching question‐asking during the consultation or medication‐taking after the consultation. However, the number of studies is too small to determine which elements of these multi‐faceted studies are essential in helping patients change their healthcare behaviours.

Background

Communication problems between healthcare providers and patients are common. Various studies have found that many patients are dissatisfied with the quality of the interaction with their healthcare provider. (Coulter 1998; Ong 1995; Stewart 1995a; Stewart 1995b; Epstein 2011; Mazor 2005; Verghese 2011).Some communication problems have been attributed to the fact that many healthcare providers focus on diseases and their management, rather than on the people, their lives and their health issues.

The concept of 'patient‐centred medicine' was introduced into the medical literature in the mid 1950s by Balint, (Balint 1955; Balint 1956) who contrasted it with 'illness‐centred medicine' (Brown 1999). It has its roots within the paradigm of holism, which suggests that people need to be seen in their biopsychosocial entirety (Henbest 1989), and draws medical attention to patients' individual identities. More recently, calls for increased patient engagement suggest that providers should draw on patients' identities, concerns and preferences in acting on patient‐centeredness in the clinical encounter. The US Institute of Medicine (IOM) defined patient‐centred care as healthcare that establishes a partnership among practitioners, patients and their families to ensure that providers and systems deliver care that is attentive to the needs, values and preferences of patients. (IOM 2001). In their view, this requires mutual, power‐sharing relationships that are collaborative and include the "whole person" orientation.

In this growing literature, the meaning of patient‐centred healthcare continues to include a set of concepts that are compatible. However, different approaches use different sub‐sets of the elements of the approach. This allows "patient‐centred" to be defined somewhat differently across studies. The variability of aims is reflected as well in the heterogeneity of outcomes measured. The term patient‐centred has, at its core, an approach whereby the provider 'tries to enter the patient’s world to see illness through the patient’s eyes' (McWhinney 1989). This means that the provider is guided by the patient’s knowledge, experience (Byrne 1976), needs and preferences (Laine 1996), and comes to understand the patient as a unique human being (Balint 1969). Others (Grol 1990; Lipkin 1984; Winefield 1995) have noted the importance of information‐giving and shared decision‐making in this process. Mead (Mead 2000) has proposed a framework with the following dimensions for studying PCC: the biopsychosocial perspective; the 'patient‐as‐person' ‐ understanding the personal meaning of the illness for each individual patient; sharing power and responsibility; the therapeutic alliance; and the 'doctor‐as‐person' ‐ awareness of the influence of the personal qualities and emotion of the doctor on the doctor‐patient relationship. Shared decision making advocates focus on the need for clinicians to describe options, elicit patient preferences and agree on next steps in the decision‐making process.

Different elements of patient‐centred care (PCC) may be differently constructed and valued by different stakeholders, and for different reasons. Some people regard patient‐centred care as desirable in its own right, while others see it as a means to particular (and varied) ends. Healthcare providers and healthcare consumers may have varied opinions about which components and which outcomes of patient‐centred care are most important. For example, consumers may be more concerned with the extent to which healthcare providers assess consumers' level of knowledge and adjust the consultation accordingly, than with outcomes such as adherence to care plans. The International Alliance of Patients' Organizations, in its declaration on patient‐centred healthcare, includes the involvement of patients in health policy and ready access to information (IAPO 2007).

Patient‐centredness is increasingly being advocated and incorporated into the training of healthcare providers. The growth of interest in training healthcare providers in patient‐centred care has occurred despite a relatively poor empirical understanding of the effects of different interventions to promote it. A growing consensus, however, identifies provider‐patient communication as a key to achieving patient‐centred care. The IOM document specifies as keys that providers use skills and behaviours that promote a relationship in which patients actively participate as partners in healthcare decision making. The US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE), beginning in 2012, will require that to obtain licensure, US physicians demonstrate in the examination, skills that foster the doctor‐patient relationship; as well as gathering information, providing information, making decisions and supporting emotions (US 2012). The move toward testing patient‐centred care skills in professional education is based on the studies that demonstrate a correlation between effective provider‐patient communication and improved patient health outcomes (Stewart 1995a; Epstein 2007). This review extends that empirical tradition and updates the 2001 Cochrane review, synthesizing the maturing literature to examine rigorously the effects of PCC across studies.

Objectives

To assess the effects of interventions for healthcare providers that aim to promote a patient‐centred approach in clinical consultations. We considered the effects on provider‐patient interactions, healthcare behaviours (including health service utilisation), patients' health and wellbeing, and patients' satisfaction with care.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs), excluding other study designs that were included in the previous version of this review (controlled clinical trials, controlled before and after studies, and interrupted time series). This restriction to RCTs limits the likelihood of sampling error, which is especially important because the providers who volunteer for studies of PCC methods are likely to be different from the general population of providers.

Types of participants

We included studies of all types of healthcare providers, including those training to qualify as healthcare providers.This review focuses primarily on interventions directed at healthcare providers. Some studies, however, combined provider interventions with those given directly to patients. Most assessed some patient outcomes. There were no restrictions on the types of patients for whom outcome data were extracted.

Types of interventions

Any intervention directed at healthcare providers and intended to promote patient‐centred care within clinical consultations was considered.

The update maintains the original definition of patient‐centred care (Lewin 2001), in which shared treatment decision making is a sufficient indicator of patient‐centred care. We defined patient‐centred care as including the following two main features:

healthcare providers share control of consultations, decisions about interventions or the management of the health problems with patients, and/or

healthcare providers focus on the patient as a person, rather than solely on the disease, in consultations.

The review focused on clinical consultations firstly because these are the most usual type of encounters between patients and healthcare providers. Secondly, we wanted to differentiate interventions to promote patient‐centred care in the context of clinical healthcare consultations from related interventions that may be intended to promote patient‐centred approaches in social support or social care. These interventions are likely to be quite different in terms of their target groups; their outcomes; and their policy implications.

An intervention was included if the description of the intervention was adequate to allow review authors to establish that it aimed to increase the patient‐centred behaviours of providers in the clinical consultation. By patient‐centred care we mean behaviours that reflect a philosophy of care that encourages

shared control of the consultation, decisions about interventions or management of the health problems with the patient, and/or

a focus in the consultation on the patient as a whole person who has individual preferences situated within social contexts. This is in contrast to a focus in the consultation on a body part or disease.

In the original review (Lewin 2001), authors assessed the intensity of patient‐centredness and teaching/training tactics for each intervention in the included studies using a three point scale (weak, medium, strong), but the review found this scale to be unreliable. In this update, we used a proxy measure of intervention intensity, namely number of hours, dichotomized as Brief Training (< 10 hours) and Extensive Training (> 10 hours).

Exclusions

We excluded:

studies that considered cultural, disability, sexuality or other sensitivity training only for healthcare providers. Although sensitivity to these issues may be necessary for patient‐centred care, it is not sufficient in itself to constitute patient‐centred care according to our definition.

studies that evaluated training in psychotherapy or counselling for healthcare providers. Although training in psychotherapy and counselling would meet our inclusion criteria, in psychotherapy and counselling (in contrast to most other healthcare situations), communication between healthcare provider and patient is itself the primary treatment. We therefore excluded studies that evaluated training in psychotherapy or counselling unless they specifically indicated that the training aimed to encourage a more patient‐centred approach to psychotherapy or counselling than is usually used.

studies that trained healthcare providers to deliver a specific, secondary intervention initiated by the health provider (e.g. advice on a healthy diet or smoking cessation) in a patient‐centred manner in clinical consultations, regardless of whether the intervention was related to the primary purpose of the consultation as indicated by the patient or their carer. We only classified interventions as patient‐centred if they promoted a patient‐centred approach to care that was integrated with the primary purpose of the consultation rather than being a secondary, 'bolt‐on' component of it initiated by the healthcare provider.

Types of outcome measures

A number of processes and outcomes might be affected by interventions that aim to promote patient‐centred care in the clinical consultation. We extracted all outcomes and grouped them in to the following categories:

| Outcome category | Description |

| A. Consultation processes | Consultation processes, including the extent to which patient‐centred care was judged to be achieved in practice: provider communication skills, consultation process measures |

| B. Satisfaction | Patient satisfaction with care |

| C. Health behaviour | Patient healthcare behaviours, such as concordance with care plans, attendance at follow‐up consultations, and health service utilization |

| D. Health status | Patient health status and well being, including physiological measures (for example of blood pressure); clinical assessments (for example of wound healing); patient self‐reports of symptom resolution or quality of life; and patient self‐esteem |

In this update, the 'satisfaction' category was modified from Lewin 2001 to exclude carers' satisfaction with care, as it was rarely measured, and added heterogeneity to the review's findings (see Potential biases in the review process). We modified the 'health behavior' category to be more consistent with measures of behaviours found in studies in the original review. The previous (Lewin 2001) definition was: "Other healthcare behaviours, including types of care plans agreed; providers' provision of interventions; patients' adoption of lifestyle behaviours; and patients' use of interventions and services".

Exclusions

Studies that did not include any of the outcomes listed above.

Studies which measured only healthcare providers' knowledge, attitudes or intentions, for example by assessing their responses to written vignettes describing patient cases. However, we included studies using simulated patients to assess practice.

Studies so compromised by flaws in their design or execution as to be unlikely to provide reliable data.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched:

MEDLINE (OvidSP) (January 2000 to June 17 2010) (Appendix 1),

PsycINFO (OvidSP) (January 2000 to June 2010) (Appendix 2),

CINAHL (EbscoHOST) (January 2000 to June 2010) (Appendix 3), and

EMBASE (OvidSP) (January 2000 to June 2010) (Appendix 4).

For this update, we used the same search strategy as was used in the original review (Lewin 2001). Search strategies were tailored to each database.

Lewin 2001 searched the following databases:

MEDLINE (1966 to December 1999),

HEALTH STAR (1975 to December 1999),

PsycLIT (1987 to December 1999),

CINAHL (1982 to December 1999),

EMBASE (1985 to December 1999).

Searching other resources

We searched the bibliographies of studies assessed for inclusion. Any study authors who were contacted for further information on their studies were also asked if they were aware of any other published or ongoing studies that would meet our inclusion criteria.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two authors or acknowledged screening members of the team screened all reports (titles and abstracts) against inclusion criteria (FCD, MHR, CG, JC, SL, GS, AO, RCS, AAO, LF, LBL, KKB). No review authors made selection decisions regarding any of their own studies. We resolved inconsistencies by discussion and consensus. When appropriate, we contacted study authors for further information and clarification. We retrieved in full text all articles that were judged to be potentially relevant from the titles and abstracts. Two review authors then independently assessed these retrieved articles for inclusion. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. In several papers, the description of the intervention was not sufficiently detailed to allow the review authors to judge whether it met the review's inclusion criteria. In these cases, the study authors were contacted and, where possible, we then assessed more detailed descriptions and/or materials.

We excluded studies which did not meet the Criteria for considering studies for this review after full text assessment, as well as studies that were so compromised by flaws in their design or execution as to be unlikely to provide reliable data. We listed these excluded studies, together with the reasons for their exclusion, in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Data extraction and management

For included studies, two authors independently extracted full descriptions of the interventions and participants onto a standard outline form (FCD, MHR, CG, SL, JC, GS, AO, and RCS, AAO, LF, LBL, KKB). No authors extracted data from their own studies. Data extraction sheets were checked by the first author for consistency (FCD). Where necessary, other members of the review team were asked to consider and discuss problems. The outcome variables used to measure intervention effects in each category are reported in the Characteristics of included studies table. In many cases, additional outcomes were measured. However, the table indicates 'not applicable' (NA) where none of the study outcomes addressed consultation processes, satisfaction, healthcare behaviour or health status, respectively. Consistent with the original review, two authors (FCD, CGM, GS, SL, JC, RCS, AO, JC, MHR) independently examined each measured outcome and assigned it to the categories described at Types of outcome measures.

We classified interventions by whether they focused only on providers or on providers and patients, with and without condition‐specific educational materials. We grouped outcome data from the studies to evaluate both direct effects on patient encounters (consultation process variables) and effects on patient outcomes (satisfaction, health behaviour change, health status).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (FCD, CG, GS) independently assessed the risk of bias of each included study using the criteria listed below taken from the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool in RevMan 5.1:

Random sequence generation (selection bias)

Allocation concealment (selection bias)

Blinding (performance bias and detection bias)

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias)

Selective reporting (reporting bias)

Other bias

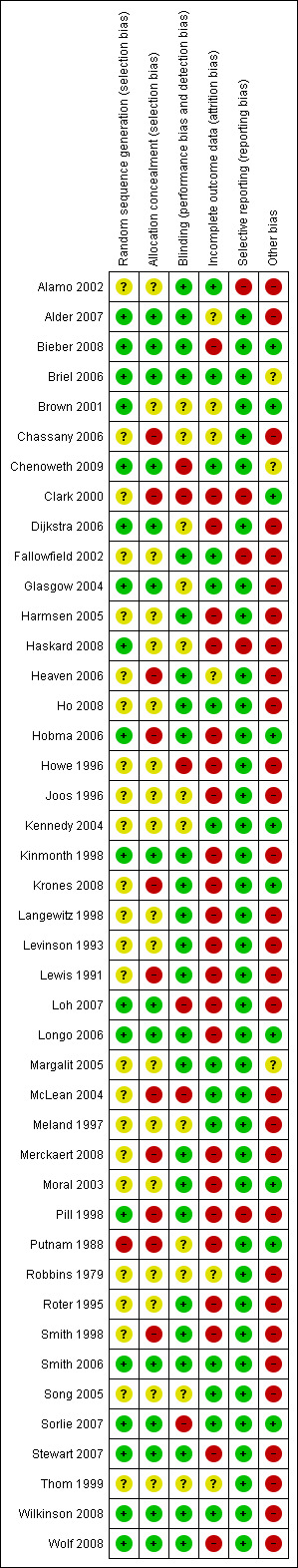

For each criterion, we reported whether it was 'done', 'not done' or 'unclear'. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion. We report the risk of bias assessment at Risk of bias in included studies, and Figure 1; Figure 2.

1.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

2.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

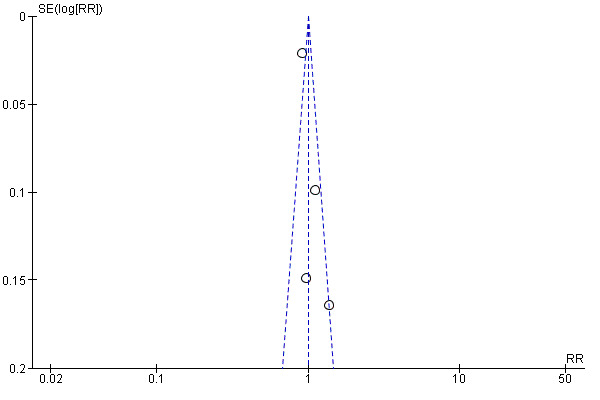

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes, we recorded the relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). In determining the RR, positive outcomes were defined as events, so RR > 1 indicates a positive effect of the intervention.

For continuous outcomes, we recorded means and standard deviations which were used to compute the standardized mean difference (SMD) and its 95% CI.

Unit of analysis issues

In the pooled analysis, for cluster randomized trials, we reviewed the methods and results reported. If authors used statistical methods that did not account for clustering of observations, we did not meta‐analyse these data. If the authors adjusted for clustering, but did not report the value of the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), we contacted the authors. Where reported, we used the ICC value to adjust the sample sizes by dividing the actual sample sizes by the design effect factor (DEFF), which was calculated using ICC as DEFF=1+(M‐1)ICC, where M is the average cluster size (eg, number of patients nested within clinician) (see Notes section of Characteristics of included studies).

Finally, if the studies contained more than two arms, we used pair‐wise comparisons of intervention to control. These steps ensured that comparable estimates of treatment effects were analysed: all from either RCTs with the patient as unit of randomisation and analysis, or from cluster randomized trials adjusted for clustering effect, and all providing between‐arm comparisons for two trial arms.

Dealing with missing data

If the information necessary for meta‐analysis was not reported in the article, we attempted to obtain such information from study authors, including ICC as described above. Further, if an article reported the results of analyses that did not compare two trial arms, then we attempted to re‐analyse the data to derive between‐group comparisons rather than within‐group comparisons. We contacted study authors for any information missing in the article that was needed for re‐analysis, such as the means and standard deviation of the outcomes in each group rather than mean change scores. If we received no response from authors, then we excluded studies with missing data from meta‐analyses (see Table 1).

1. Studies excluded completely from meta‐analysis.

| Study | Type of variable | Reason for Exclusion |

| Dichotomous | ||

| Lewis 1991 | Consultation | Need baseline data and ICCa to adjust for clustering |

| Continuous | ||

| Alamo 2002 | Consultation | Need ICCa to adjust for clustering |

| Bieber 2008 | Consultation Health status Patient satisfaction |

Need ICCa for patients clustered within physicians; Need to confirm with authors if physicians were randomized |

| Brown 2001 | Consultation Health status Health behaviour |

Need ICCa; Need Standard deviations |

| Chassany 2006 | Health status Health behaviour |

Methodological Problem; change scores analyzed instead of post intervention; No ICCa for adjusting for clustering |

| Fallowfield 2002 | Consultation? | Need number of events per doctor or odds for each group reported for table 4 on page 653. Need standard deviations |

| Haskard 2008 | Need standard deviations; Need to reanalyze data because they compared changes within groups | |

| Harmsen 2005 | Need standard deviation for Table 1. All patients. | |

| Heaven 2006 | Methodological Problem: no control; two interventions compared to each other; | |

| Krones 2008 | Consultation Health status Patient satisfaction |

Need standard errors or unadjusted standard deviations for table four; Need ICCa |

| Levinson 1993 | Consultation? | Need short program means for pre intervention and also post intervention separate; Reported as a difference which is unusable; Need Standard deviations pre and post |

| Lewis 1991 | Consultation Health status Patient satisfaction |

Need baseline data and ICCa to adjust for clustering |

| Longo 2006 | Consultation Health status Health behaviour Patient satisfaction |

Need ICCa |

| Margalit 2005 | Methodologically out; No controls; two interventions | |

| Meland 1996 | Patient behaviour? | Need ICCa to adjust for clustering |

| Moral 2003 | Consultation | Need ICCa and standard deviations |

| Pill 1998 | Satisfaction Health status |

Methodological problem: experimental providers were asked to submit a recording which demonstrated the use of the method they had been taught; Need ICCa; Need actual values post with standard deviations ? not change scores |

| Putnam 1988 | Satisfaction Health behaviour Health status |

Need standard deviations; Possible contamination |

| Robbins 1979 | Consultation | Need standard deviations pre and post |

| Smith 1998 | Consultation Satisfaction |

Methodological problem: possible contamination stated by authors; need standard deviations for attitudes and knowledge‐answered by residents; Need satisfaction post means and standard deviations for controls and interventions instead of a difference; |

| Song 2005 | Health status | Methodological problem: possible contamination. Change scores are compared |

| Thom 1999 | Satisfaction Consultation |

Need ICCa |

a) ICC: Intra‐cluster correlation

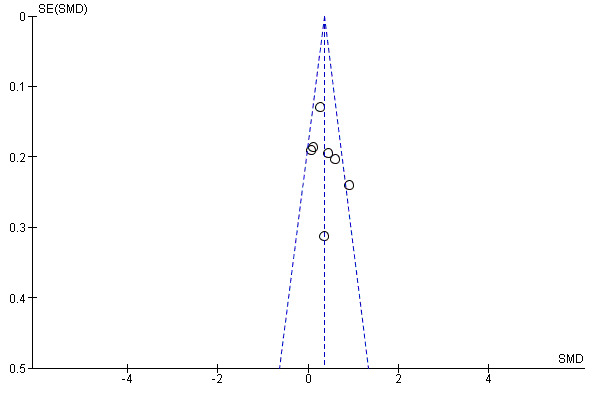

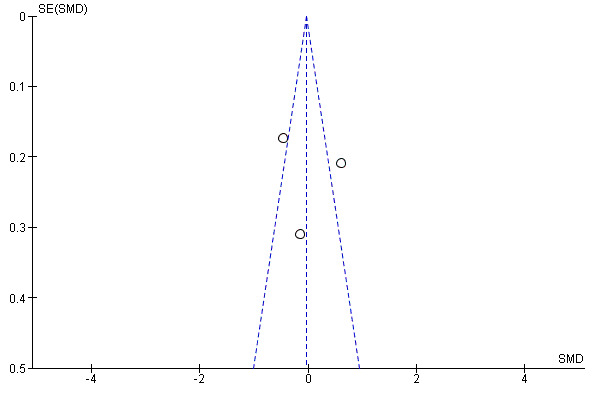

Assessment of heterogeneity

For groups of outcomes with more than two studies, we assessed heterogeneity using the I2 statistic, and a formal Chi2 test of significance. A value of 50% or higher of the I2 statistic, and P value > 0.1 indicated substantial heterogeneity (Higgins 2003). Where heterogeneity was substantial, an attempt was made to explore the sources of heterogeneity using the a priori generated list of study characteristics (see Data extraction and management above). Characteristics included: academic or non‐academic setting, country, inclusion of an experiential component, number of hours of experiential training, total number of hours of training, individual randomisation or cluster randomisation, usual care control or sham intervention control, whether the outcome analysed was primary or secondary, whether the analysis followed the intention to treat strategy. We conducted subgroup analyses according to the levels of study characteristics. We also investigated methodological problems with the studies as a potential source of heterogeneity.

Data synthesis

Limiting the current update to RCTs allowed us to pool data within categories by conducting meta‐analyses of included studies where similar outcome measures were used within categories. Two authors (SJ, AS) pooled results of RCTs using standardized mean difference (SMD) and relative risks (RR) applying a fixed‐effect model. In each outcome category it was important to keep the direction of the effects the same. For example, higher was worse in some categories, such as depression as an indicator of health status. In other categories, higher was better, such as percentage of patients making an appointment as an indicator of outcomes of consultation processes. The direction of the effects in each category of effects is labelled on the plots (see Data and analyses).

In part due to the inconsistency across categories in the pooled analysis, and because fewer than half of studies could be included in the meta‐analysis, we also conducted a descriptive analysis of the whole set of studies according to the four outcome categories. We report a summary of this analysis at Effects of interventions and a detailed narrative synthesis at Appendix 5. We summarized the results of the descriptive analysis in terms of the number of studies showing a positive effect out of the number of studies that measured that outcome for each of the categories (see Table 2).

2. Impact of Interventions ‐ summary of qualitative analysis.

| Intervention category | Total studies in category |

Studies in which consultation process outcomes favoured intervention / Total studies assessing consultation process (%) |

Studies in which satisfaction outcomes favoured intervention / Total studies reporting satisfaction (%) |

Studies in which patient behaviour outcomes favoured intervention / Total studies reporting patient behaviour (%) |

Studies in which health status outcomes favoured intervention / Total studies reporting health status (%) |

| 1 (PCC training for providers) | 23 | 16/22 (73%) | 6/13 (46%) | 1/4 (25%) | 5/11 (45%) |

| 2 (PCC for providers plus training or materials for patients) | 7 | 5 /6 (83%) | 1/4 (25%) | 0/2 (0%) | 3/4 (75%) |

| 3 (PCC plus condition‐specific training for providers) | 7 | 2/2 (100%) | 2/5 (40%) | 4/6 (67%) | 2/6 (33%) |

| 4 (PCC plus condition‐specific training for providers, plus training for patients) | 6 | 5/5 (100%) | 3/4 (75%) | 3/5 (60%) | 3/6 (50%) |

| Total | 43 | 28/35 (80%) | 12 /26 (46%) | 8/17 (47%) | 12/26 (46%) |

For continuous outcomes, to maintain one direction within each group of outcomes in meta‐analysis (e.g. larger is worse as in anxiety), outcomes with higher scores indicating better outcomes were reverse scored by subtracting the reported means from the scale totals. Where reported, the adjusted estimates and baseline values of the outcomes were recorded.

If reported, one dichotomous and one continuous outcome from each study were included within the four outcome groups: consultation process, satisfaction, health behavior, and health status. If more than one outcome from each group was reported, then the following strategies were implemented to choose one outcome:

primary outcomes were selected over secondary;

total scale scores were selected over sub‐scale scores; and finally

outcomes with median RR or SMD were selected for data synthesis.

Each group of outcomes was also described with the median RR and SMD and the number of studies with significant effects. Because many of the studies were cluster randomized trials, and ICCs were not available in the articles or after contacting the authors, the number of studies in each outcome subgroup was small. This issue and few studies with the number of hours of training reported prevented the implementation of the dose response meta‐regression. Subgroup analyses according to the dichotomous study characteristics shed light on the association between these study characteristics and the magnitude of the intervention effect.

Sensitivity analysis

To determine if the summary effects were dependent on outliers or studies with low methodological quality, we performed the meta‐analyses with and without these studies.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The original review (Lewin 2001) identified 5260 titles and abstracts by electronic searching; 135 of these were judged to potentially meet the entry criteria and the full articles were retrieved for further detailed assessment. The original review included 15 randomized controlled trials (all published before January 2000) and 2 non‐randomized controlled clinical studies.

Our updated searches in June 2010 generated 8469 titles and abstracts, of which 100 were retrieved in full text for further assessment.

Included studies

The original review (Lewin 2001) ostensibly included 15 RCTs and 2 non‐randomized clinical trials. Through discussion with the study author we have since identified that the two papers by Smith et al (Smith 1995; Smith 1998), which were reported as separate trials in the original review, were in fact reports of the same RCT.

We added 29 studies published between January 2000 and May 2010 to the original 14 studies (Lewin 2001), bringing the total number of trials included in this update to 43 (Alamo 2002; Alder 2007; Bieber 2008; Briel 2006; Brown 2001; Chassany 2006; Chenoweth 2009; Clark 2000; Dijkstra 2006; Fallowfield 2002; Glasgow 2004; Harmsen 2005; Haskard 2008; Heaven 2006; Ho 2008; Hobma 2006; Howe 1996; Joos 1996; Kennedy 2004; Kinmonth 1998; Krones 2008; Langewitz 1998; Levinson 1993; Lewis 1991; Loh 2007; Longo 2006; Margalit 2005; McLean 2004; Meland 1997; Merckaert 2008; Moral 2003; Pill 1998; Putnam 1988; Robbins 1979; Roter 1995; Smith 1998; Smith 2006; Song 2005; Sorlie 2007; Stewart 2007; Thom 1999; Wilkinson 2008; Wolf 2008). These 43 studies were reported in 74 papers. Fewer than half (N = 21) of the 43 studies met the criteria for inclusion in at least one comparison in the meta‐analyses.

Clark 2000 provides additional data for a study included in the original review as Clark 1998.

Interventions and comparisons

The interventions involved training related to a variety of skills, using diverse teaching techniques and lengths of training. Some used placebo controls and some used pure usual care, as noted in the Characteristics of included studies table. Aims of the interventions ranged from improving patient centeredness as a primary goal to improving health behaviour of patients and/or effectiveness of providers in managing medical problems. Studies focused always on providers, by definition. However, the addition in some studies of decision aids and patient education materials (both general and condition‐specific) and patient training suggested that interventions have become more complex, and directed to both the provider and the patient sides of the encounter. While none of the studies included in Lewin 2001 described shared decision making as an aim, four in the current review did aim to improve shared decision making (Bieber 2008; Krones 2008; Loh 2007; Longo 2006).

To capture this emerging diversity in aims of studies, our descriptive results are presented in four intervention categories as follows:

| Intervention category | PCC intervention | Other component | Number of studies |

| 1 | PCC training for providers | None | 23 |

| 2 | PCC training for providers | Training or general educational materials for patients | 7 |

| 3 | PCC training for providers | Condition‐specific training or materials (eg. management of asthma or diabetes mellitus) for providers | 7 |

| 4 | PCC training for providers | Condition‐specific materials or training for both providers and patients | 6 |

Setting

All 43 of the included studies were published in English. Studies were conducted in 13 countries from North America, Europe and Eastern Asia. There were no studies from low and middle income countries.

| Country | Number of studies |

| USA | 16 |

| UK | 10 |

| Germany | 3 |

| Each of Netherlands, Spain, Australia, Switzerland | 2 |

| Each of Canada, France, Holland, Israel, Norway, Taiwan | 1 |

Unit of randomisation

The unit of randomisation was the organisation or practice in 9 studies (Chenoweth 2009; Hobma 2006; Meland 1997; Kinmonth 1998; Pill 1998, Dijkstra 2006; Kennedy 2004, Moral 2003, Krones 2008), the individual healthcare provider in 25 studies (Alder 2007; Alamo 2002; Briel 2006; Chassany 2006; Clark 2000; Fallowfield 2002; Glasgow 2004; Harmsen 2005; Heaven 2006; Ho 2008; Howe 1996; Joos 1996; Langewitz 1998, Levinson 1993; Lewis 1991; Loh 2007; Margalit 2005; Merckaert 2008; Putnam 1988; Robbins 1979; Roter 1995; Smith 1998; Stewart 2007; Thom 1999; Wilkinson 2008), the patient in 6 studies (Bieber 2008; McLean 2004; Smith 2006; Song 2005; Sorlie 2007; Wolf 2008); and both the provider and patient in 3 studies (Brown 2001; Haskard 2008; Longo 2006).

Trainer characteristics

Training interventions were delivered by healthcare providers and/or research centre staff in 19 studies (Alder 2007; Chenoweth 2009; Chassany 2006; Heaven 2006; Hobma 2006; Howe 1996; Lewis 1991; Krones 2008; Langewitz 1998; Margalit 2005; Pill 1998; Putnam 1988; Robbins 1979; Roter 1995; Smith 1998; Smith 2006; Sorlie 2007; Stewart 2007; Thom 1999). The remaining 24 studies did not indicate the identity of intervention trainers. Moreover, only ten of the 43 studies reported any kind of training or certification of intervention trainers (Chenoweth 2009; Chassany 2006; Fallowfield 2002; Haskard 2008; Kinmonth 1998; Kennedy 2004; Levinson 1993; Roter 1995; Stewart 2007; Wilkinson 2008).

Consumer involvement

Only three studies (Dijkstra 2006; Kinmonth 1998; Stewart 2007) appeared to have involved consumers in the development of the intervention. None of the 43 studies involved consumers in the actual training of providers.

Patient participants

The 43 included studies evaluating PCC interventions focused on a variety of clinical conditions, although the most common patients were adults with general medical problems. Three studies used simulated patients with a common medical and/or psychosocial problem (Ho 2008; Langewitz 1998; Moral 2003); three others used both real and simulated patients with generalized musculoskeletal pain/fibromyalgia (Alamo 2002), cancer (Wilkinson 2008), and general medical problems (Alder 2007). The remaining 37 studies included only real patients. Two of them included children with asthma (Clark 2000) and a range of different problems (Lewis 1991). The remaining 35 studies enrolled adults with: general medical problems (Briel 2006; Harmsen 2005; Haskard 2008; Heaven 2006; Ho 2008; Hobma 2006; Howe 1996; Joos 1996; Levinson 1993; Longo 2006; Margalit 2005; McLean 2004; Putnam 1988; Robbins 1979; Roter 1995; Smith 1998; Thom 1999); and more specific medical conditions like diabetes (Dijkstra 2006; Glasgow 2004; Kinmonth 1998; Pill 1998), cancer (Brown 2001; Fallowfield 2002; Merckaert 2008; Stewart 2007), depression (Loh 2007), high coronary heart disease risk (Meland 1997), inflammatory bowel diseases (Kennedy 2004), osteoarthritis (Chassany 2006), fibromyalgia (Bieber 2008), dementia (Chenoweth 2009) and medically‐unexplained symptoms (Smith 2006). Three studies enrolled adult patients undergoing surgery for heart disease (Song 2005; Sorlie 2007) and obesity (Wolf 2008).

Healthcare‐provider participants

In most of the studies, training interventions were directed at primary care physicians (general practitioners, internists, paediatricians or family doctors) or nurses practising in community or hospital outpatient settings. In other studies, specialists were also trained. For example, Alder 2007 trained only obstetricians and gynaecologists. Brown 2001, Fallowfield 2002 and Merckaert 2008 trained medical, radiation, and/or surgical oncologists at specialty cancer centres. Six studies trained nurses and/or nurse practitioners (Heaven 2006; Smith 2006; Song 2005; Sorlie 2007; Wilkinson 2008; Wolf 2008); four studies trained both primary care physicians and nurses (Dijkstra 2006; Kennedy 2004; Kinmonth 1998; Pill 1998), and one study (Chenoweth 2009) trained care givers at residential dementia care sites. The clinical experience of providers varied both within and across studies, ranging from medical students with five years of medical education to providers with more than 20 years of clinical experience. The study sample sizes also varied from 8 to 41 practices in the nine studies randomized by practice, and 4 to 172 providers in the 31 studies that randomized by providers. One study that randomized 30 CME insurance groups did not provide the number of practices and/or providers included (Krones 2008).

The process through which providers were selected to participate in the studies also varied. In two studies (Ho 2008; Smith 1998), participation in the training programmes appeared to have been compulsory (as part of medical school (Ho 2008) or postgraduate (Smith 1998) training); although in Smith 1998, postgraduate trainees were allowed to opt out of the analysis. For the remaining studies, however, participation appeared to be voluntary. Provider recruitment methods were as follows:

| Method of recruiting providers | Study |

| Approached whole practices | Alder 2007; Briel 2006; Dijkstra 2006; Heaven 2006; Hobma 2006; Joos 1996; Kinmonth 1998; Levinson 1993; Lewis 1991; Loh 2007; Longo 2006; Margalit 2005; McLean 2004; Merckaert 2008; Pill 1998; Robbins 1979; Stewart 2007 |

| Approached subsets of providers from specified groups or areas | Clark 2000; Langewitz 1998; Meland 1997; Putnam 1988; Thom 1999; Wilkinson 2008 |

| Approached physicians from the mailing lists of local medical societies | Chassany 2006 |

| Approached physicians from the mailing lists of insurance companies | Glasgow 2004; Krones 2008 |

| Providers were care staff at residential care sites and were selected by managers as competent and interested personnel | Chenoweth 2009 |

| Not specified | Alamo 2002; Bieber 2008; Brown 2001; Fallowfield 2002; Harmsen 2005; Haskard 2008; Howe 1996; Kennedy 2004; Moral 2003; Smith 2006; Song 2005; Sorlie 2007; Wolf 2008). |

In 30 of the 43 studies, the percentage of invited providers who agreed to participate ranged from 5 per cent (Glasgow 2004) to 100 per cent (Alamo 2002). In the other 13 studies this percentage was unclear (Bieber 2008; Brown 2001; Chenoweth 2009; Clark 2000; Dijkstra 2006; Levinson 1993; McLean 2004; Merckaert 2008; Smith 2006; Song 2005; Sorlie 2007; Thom 1999; Wolf 2008).

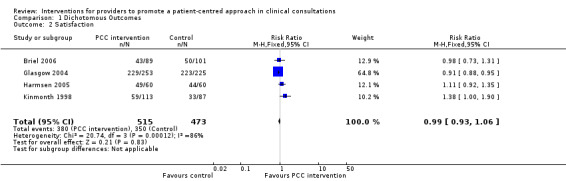

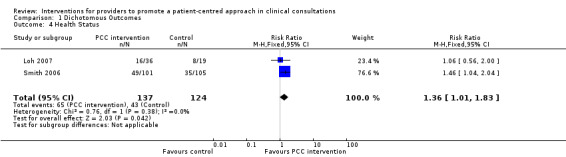

Outcomes

Most of the included studies evaluated the impact on consultation processes (n = 35, Table 3) and many also evaluated the impact on patient satisfaction (n = 26, Table 4). Patient health behaviours were less frequently assessed (n = 17, Table 5). Patient health status (n = 26, Table 6) was evaluated quite frequently.

3. Category A consultation process outcome measures.

| Study ID | Outcome Category A: Consultation Process | How assessed | Use in analysis |

| Provider consultation communication behaviour | |||

| Alamo 2002 | Provider use of patient‐centred communication behaviours in video recordings of encounters. | Used GATHERES‐CP scoring system | Narrative |

| Alder 2007 | Provider use of patient‐centred communication behaviours in video recordings of encounters, shared decision making | Observation from videotapes as measured by the Maastricht History and Advice Checklist‐Revised (MAAS‐R). | Continuous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Fallowfield 2002 | Provider use of patient‐centred communication behaviours in video recordings of encounters, shared decision making | Medical Interaction Process System (MIPS) | Narrative |

| Haskard 2008 | Physician information giving | Patient report | Narrative |

| Heaven 2006 | Provider use of patient‐centred communication behaviours in audio recordings of encounters | Medical Interview Aural Rating Scale (MIARS) | Narrative |

| Ho 2008 | Provider use of patient‐centred communication behaviours in observed standardized patients | OSCE scores on observed standardized patient encounter | Continuous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Hobma 2006 | Provider use of patient‐centred communication behaviours in video recordings of encounters | MAAS Global Questionnaire for Providers. | Continuous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Howe 1996 | Provider's psychological distress detection rate following training in communication skills among video recordings of own patients | Checklist for video analysis among patients with high scores on General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) | Continuous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Joos 1996 | Provider elicitation of all patient concerns (previously stated on checklist) in audio recordings of encounters | Roter Interactional Analysis System (RIAS) | Continuous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Kinmonth 1998 | Quality of communication with provider | Proportion of patients rating maximum quality | Dichotomous |

| Krones 2008 | Shared decision making, patient perception that doctor knows patient | SDM‐Q, Patient Participation Survey | Narrative |

| Langewitz 1998 | Provider use of patient‐centred communication behaviours in video recordings of encounters with standardized patients | Maastricht History and Advice Checklist‐Revised (MAAS‐R) | Continuous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Levinson 1993 | Provider and patient‐centred communication behaviours |

Change scores: observed from video using RIAS | Narrative |

| Lewis 1991 | Patient‐centered communication style in video recording of actual encounters |

Percentage and number of statements in encounter by Pantell/Stewart coding method | Narrative |

| Loh 2007 | Consultation time; doctor facilitation of patient involvement | Time in min; Participation surveys: PICS, variation of Man‐Song‐Hing scale | Continuous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Longo 2006 | Involving patient in decision making | Observation (Provider score on OPTION instrument for patient agreement and involvement) | Narrative |

| Margalit 2005 | Provider’s biopsychosocial knowledge, intentions, patient‐centred attitudes; Physician detection of patient distress |

Physician self‐report; Patient report (physician detection of patient distress) | Narrative |

| Merckaert 2008 | Patient‐centered communication style in audio recording of simulated and actual encounters |

Audio rating: French translation of “Cancer Research Campaign Workshop Evaluation Manual”; | Continuous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Moral 2003 | Consultation behaviour in standardized patient encounters | Rated by GATHA‐RES (instrument/rating scale designed by authors) | Narrative |

| Pill 1998 | Provider use of patient‐centred communication behaviours in audiotaped encounters. | Investigator developed coding | Narrative |

| Putnam 1988 | Patient and provider use of patient‐centred communication behaviours in audiotaped encounters | Coded verbal response modes (VRMs) | Narrative |

| Robbins 1979 | Provider use of patient‐centred communication behaviours in video taped encounters; empathy scores | Coded responses using Kagan, Brockway, Curkhuff scales; Affect Sensitivity Scale (empathy) | Narrative |

| Roter 1995 | Provider use of emotion‐handling skills in audio recordings of encounters with simulated patients, actual patients | Changes in emotion handling score using study‐specific coding measure | Dichotomous |

| Smith 1998 | Provider use of patient‐centred communication behaviours in audio recorded encounters with real patients, video recorded simulated patients. | Study‐specific rating scales | Narrative |

| Song 2005 | Knowledge of advanced care planning | Patient/surrogate report | Continuous |

| Stewart 2007 | Provider use of patient‐centred communication behaviours in video recordings of encounters. | Score from Patient‐Centred Communication Measure | Continuous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Thom 1999 | Provider's humaneness during visit | Patient perception from score on Physician Humanistic Behaviors Questionnaire | Narrative |

| Wilkinson 2008 | Provider use of patient‐centred communication behaviours in audio recordings of encounters. | Communication Skill Rating Scale coverage score at baseline; skills change score) | Continuous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Wolf 2008 | Reported skills by providers | Structured checklist | Narrative |

| Patient centered actions | |||

| Briel 2006 | Medication prescribed | Provider self‐report | Dichotomous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Clark 2000 | Medication prescribed, treatment/action plan given | Patient/parent report, provider survey | Dichotomous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Dijkstra 2006 | Diabetes‐specific process measures at index visit and 12 months | From medical record | Narrative |

| Glasgow 2004 | Patient‐centred activities completed | Number completed out of a priori list | Continuous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Impact on provider‐patient relationship | |||

| Bieber 2008 | Quality of patient‐physician relationship | By FAPI questionnaire, patient report | Narrative |

| Harmsen 2005 | Mutual understanding | Patient and doctor survey, Mutual Understanding Scale (MUS) | Narrative |

| Other consultation process outcomes | |||

| Brown 2001 | Duration of consultation | Audiotape recording | Narrative |

| Kennedy 2004 | Number of visits to clinic, medical and surgical treatment in hospital | Counts from medical record | Narrative |

| McLean 2004 | Duration of consultation | Timed by the physician | Narrative |

4. Category B satisfaction outcome measures.

| Study ID | Outcome category B: Satisfaction | How assessed | Use in analysis |

| Alamo 2002 | Patient experience of the consultation | Survey at 2 to 3 months | Narrative |

| Alder 2007 | Satisfaction with consultation and relationship | Adapted version of the Kravitz survey | Narrative |

| Bieber 2008 | Patient satisfaction with decision; decisional conflict | Satisfaction with Decision (SWD); Decisional Conflict Scale (DCS) | Narrative |

| Briel 2006 | Patient satisfaction with care received | Score on Langewitz, Patient Satisfaction Survey relative to validation study score | Dichotomous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Clark 2000 | Satisfaction with consultation | Patient report using Likert‐type scale items to assess doctor performance of consultation skills | Narrative |

| Glasgow 2004 | Patient satisfaction with care | Patient satisfaction items of Diabetes Patient Recognition Program (PRP) | Dichotomous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Harmsen 2005 | Satisfaction with consultation | 3‐item survey | Dichotomous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Haskard 2008 | Satisfaction with information, overall care | Physician Information‐giving scale (Heisler), single item: whether recommend doctor to a friend | Narrative |

| Joos 1996 | Patient satisfaction with physician skills | American Board of Internal Medicine Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire | Continuous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Kennedy 2004 | Satisfaction with initial consultation | Consultation satisfaction questionnaire (Baker) | Continuous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Kinmonth 1998 | Patient satisfaction with treatment | Survey dichotomized to high/low | Dichotomous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Krones 2008 | Satisfaction with care process and outcome | Patient Participation Scale (Man‐Son‐Hing) | Narrative |

| Langewitz 1998 | Patient satisfaction; Patients who would recommend doctor to a friend. | Score on the German version of the PSQ by the American Board of Internal Medicine; Proportion recommend | Narrative |

| Lewis 1991 | Child satisfaction with visit; parent satisfaction with visit | Child Satisfaction Questionnaire; Parent Medical Interview Satisfaction Scale | Narrative |

| Loh 2007 | Patient satisfaction with care | German version of CSQ‐8 questionnaire for patients | Continuous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Longo 2006 | Patient satisfaction with communication | COMRADE | Narrative |

| McLean 2004 | Satisfaction with consultation | Consultation Satisfaction Questionnaire (Baker) | Continuous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Merckaert 2008 | Satisfaction with physician communication skills | Perception of the Interview Questionnaire (Devaux) | Narrative |

| Pill 1998 | Satisfaction treatment | SF36 | Narrative |

| Putnam 1988 | Satisfaction with encounter | Medical Interview Satisfaction Scale | Narrative |

| Smith 1998 | Patient satisfaction with medical interview | 29 item locally‐developed scale | Narrative |

| Smith 2006 | Patient satisfaction with provider‐patient relationship | Satisfaction With Provider Patient Relationship Questionnaire (PPR) by Smith | Narrative |

| Stewart 2007 | Patient satisfaction with doctor’s information‐giving and interpersonal skills | Cancer Diagnostic Interview Scale (CDIS) | Continuous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Thom 1999 | Patient's satisfaction with visit | Survey by Davis | Narrative |

| Wilkinson 2008 | Satisfaction with care | 'Patient Satisfaction With Communication' by Ware | Continuous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Wolf 2008 | Satisfaction with care | Baker and Taylor Measurement Scale (BTMS) patient survey | Continuous variable in meta‐analysis |

5. Category C health behaviour outcome measures.

| Study ID | Outcome category C: Health Behavior | How assessed | Use in analysis |

| Alder 2007 | Compliance | Kravitz questionnaire for patients | Narrative |

| Bieber 2008 | Therapeutic modality chosen (medication, exercise, relaxation) | Medical record | Narrative |

| Briel 2006 | Re‐consultation within 14 days | Patient survey at 14 days | Dichotomous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Brown 2001 | Patient consultation behaviours (question asking, information recall) | None | Not included |

| Clark 2000 | Emergency department visits; hospitalizations; school days missed | Parent/patient report | Narrative |

| Glasgow 2004 | Self‐management goal setting | Met NCQA/ADA diabetes Physician Recognition Program (PRP) criteria or not | Dichotomous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Joos 1996 | Medication adherence | Meds score = Number of meds dispensed divided by number prescribed | Continuous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Kennedy 2004 | Making no more than 2 GP visits per year | Medical record | Dichotomous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Kinmonth 1998 | Patients' lifestyle: diet, exercise, smoking | Self‐report | Narrative |

| Krones 2008 | Patient participation in encounter | Patient Participation Scale | Narrative |

| Loh 2007 | Information seeking | PICS‐IS | Continuous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Longo 2006 | Adherence expectation | COMRADE sub scales | Narrative |

| Meland 1997 | Physical activity, smoking | Self‐report | Narrative |

| Pill 1998 | Patient attendance at practice over last 12 months; smoking and alcohol use |

Self‐report | Narrative |

| Putnam 1988 | Medication adherence, Appointment adherence |

Meds = telephone interview Appointment adherence = medical record |

Narrative |

| Roter 1995 | Utilisation of health care by GHQ positive patients | General Healthcare Questionnaire (GHQ) | Narrative |

| Smith 2006 | Antidepressant used to full dose | Medical record review | Dichotomous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Thom 1999 | Continuity with study provider; medication or advice adherence | Medical record review at 6 months | Narrative |

6. Category D health status outcome measures.

| Study ID | Outcome category D: Health status | How assessed | Use in analysis |

| Alamo 2002 | Pain, depression and anxiety | Pain Scale of Nottingham Health Profile; Goldberg Scale of Anxiety, Depression | Narrative |

| Bieber 2008 | Pain, depression; functional capacity; general health status | Pain level (0‐10 VAS) CES‐D; Hannover Functional Quest; SF‐12 | Narrative |

| Briel 2006 | Number of days with restricted activities | Self‐report | Continuous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Brown 2001 | Anxiety | Spielberger | Narrative |

| Chassany 2006 | Pain relief, stiffness, physical functioning/global health; adverse events | WOMAC = physical functioning, stiffness; Adverse events = Lequensne Index | Narrative |

| Chenoweth 2009 | Quality of life in late‐stage dementia | 'Quality of life in late‐stage dementia' survey | Continuous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Dijkstra 2006 | HbA1c level | Medical record review | Continuous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Glasgow 2004 | Quality of life, depression | Patient Health Questionnaire‐depression (PHQ‐9) | Narrative |

| Kennedy 2004 | Number and duration of relapses during the course of the year | HADS –Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale | Continuous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Kinmonth 1998 | Wellbeing score, quality of life | Not specified | Narrative |

| Krones 2008 | Cardiovascular risk | Mean change on Framingham calibrated for Europeans | Narrative |

| Lewis 1991 | Anxiety (child) | Reported by parent | Narrative |

| Loh 2007 | Depression severity | Brief PHQ‐D patient questionnaire | Dichotomous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Longo 2006 | Anxiety; health status | Anxiety = Spielberger; health status =SF‐12 | Narrative |

| McLean 2004 | Anxiety | Spielberger | Continuous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Meland 1997 | Risk factors for CHD (blood pressure, cholesterol); Combine risk of myocardial infarction compared with a female without risk factors | Mean from record review | Narrative |

| Merckaert 2008 | Change in anxiety | STAI‐S | Continuous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Pill 1998 | Health status Diabetes‐specific measures of well being |

Health status = SF‐36 | Narrative |

| Putnam 1988 | Symptom improvement | Patient questionnaire Index: 3x5 point scales (Mushlin 1978) | Narrative |

| Roter 1995 | Health status | GHQ | Narrative |

| Smith 1998 | Patients' physical and psychosocial well being | Change in health status or not, on GHQ | Dichotomous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Smith 2006 | Mental health | MH scale on SF‐36 survey | Narrative |

| Song 2005 | Anxiety, difficulty making choices | Spielberger STAI | Narrative |

| Sorlie 2007 | Subjective health, overall emotional well‐being | SF‐36 | Continuous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Stewart 2007 | Patients’ psychological distress | Brief Symptom Inventory | Narrative |

| Wilkinson 2008 | Health status | General Health Questionnaire‐12 (GHQ‐12) | Continuous variable in meta‐analysis |

| Wolf 2008 | Bariatric patients post‐op infections, complications | Medical record reviews | Narrative |

Excluded studies

The two non‐randomized clinical trials included in Lewin 2001 were excluded from this update as they no longer met the inclusion criteria (Cope 1986; Roter 1998).

In the Characteristics of excluded studies table we list those studies assessed in full text which were then excluded. The main reasons for exclusion were: ineligible study design, failure to meet patient‐centred criteria, or intervention was not directed at providers.

Risk of bias in included studies

All 43 included studies were at risk of at least one of the potential biases; but none was at high risk for all of them. The details of the risk of bias of included studies are given under each reference in the Characteristics of included studies. See also Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Overall risk of bias was moderate to high, with the highest risks in the elements of random sequence generation and concealment, and blinding of outcome assessors. Conversely, most studies had low risk of reporting bias.

Allocation

Only 18 of 43 studies were judged to have a well‐described randomisation process. Twelve studies explicitly reported concealed and secure allocation (Bieber 2008; Briel 2006; Chenoweth 2009; Dijkstra 2006; Kinmonth 1998; Loh 2007; Longo 2006; Smith 2006; Sorlie 2007; Stewart 2007; Wilkinson 2008; Wolf 2008). Two of these, (Dijkstra 2006; Sorlie 2007) did not describe how the sequence was generated, but allocation was clearly concealed. In the other ten, allocation was made by computer, random number table, or by casting blinded lots. We judged sequence allocation and/or concealment to be adequate in six other studies, even though they were only partially described (Alder 2007; Brown 2001; Glasgow 2004; Haskard 2008; Hobma 2006; Pill 1998). Even after email correspondence with authors, sequence allocation and concealment was judged to be either inadequate or unclear in the remaining 25 studies, raising concerns about selection and confounding biases in these studies (Alamo 2002; Chassany 2006; Clark 2000; Fallowfield 2002; Harmsen 2005; Heaven 2006; Ho 2008; Howe 1996; Joos 1996; Kennedy 2004; Krones 2008; Langewitz 1998; Levinson 1993; Lewis 1991; Margalit 2005; McLean 2004; Meland 1997; Merckaert 2008; Moral 2003; Putnam 1988; Robbins 1979; Roter 1995; Smith 1998; Song 2005; Thom 1999).

Blinding

Blinding of outcome assessors was reported or clear in the majority (28/43) of studies (Alamo 2002; Alder 2007; Bieber 2008; Briel 2006; Chenoweth 2009; Harmsen 2005; Heaven 2006; Ho 2008; Hobma 2006; Kinmonth 1998; Krones 2008; Langewitz 1998; Levinson 1993; Lewis 1991; Longo 2006; Margalit 2005; Merckaert 2008; Moral 2003; Pill 1998; Putnam 1988; Robbins 1979; Roter 1995; Smith 1998; Smith 2006; Stewart 2007; Thom 1999 (interviewers, but not chart abstractors); Wilkinson 2008; Wolf 2008). In one study (Fallowfield 2002), outcome assessors for the primary outcome were blinded "as far as possible," but authors did not report blinding for other "subjective and objective" ratings which were planned for future publications. For the remaining 14 studies it was unclear or unlikely that blinding of outcome assessors had been ensured (Brown 2001; Chassany 2006; Clark 2000; Dijkstra 2006; Glasgow 2004; Haskard 2008; Howe 1996; Joos 1996; Kennedy 2004; Loh 2007; McLean 2004; Meland 1997; Song 2005; Sorlie 2007).

Incomplete outcome data

Outcome data were complete in only six studies (Brown 2001; Fallowfield 2002; Ho 2008; Robins 1989; Song 2005; Thom 1999 ). Of the 37 studies with incomplete data, 12 clearly adopted an intention to treat (ITT) approach to statistical analysis (Alamo 2002; Briel 2006; Chenoweth 2009; Glasgow 2004; Joos 1996; Kennedy 2004; Margalit 2005; McLean 2004; Meland 1997; Smith 2006; Sorlie 2007; Wilkinson 2008), raising the possibility of bias in the remaining 25 studies. Five studies stated that ITT analysis was used, but they did not include some participants with missing data in final analyses (Bieber 2008; Chassany 2006; Hobma 2006; Kinmonth 1998; Moral 2003). One study stated that an ITT approach was not used (Roter 1995). In the other 19 studies, it was either unlikely or unclear that this approach had been used (Alder 2007; Clark 2000; Dijkstra 2006; Harmsen 2005; Haskard 2008; Heaven 2006; Krones 2008; Langewitz 1998; Levinson 1993; Lewis 1991; Loh 2007; Longo 2006; McLean 2004; Merckaert 2008; Pill 1998; Putnam 1988; Smith 1998; Stewart 2007; Wolf 2008). Fallowfield 2002Ho 2008Song 2005Brown 2001Robbins 1979Thom 1999 The risk of bias from incomplete outcome data in all studies is illustrated in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Selective reporting

Only five studies appeared to be at high risk of bias from selective reporting (Alamo 2002; Clark 2000; Fallowfield 2002; Haskard 2008; Pill 1998). All other studies were at low risk for this bias (see Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Other potential sources of bias

Protection against contamination

In studies conducted before1999, attempts to ensure protection from contamination from the intervention to the control group were reported in one study only (Putnam 1988) in which intervention group physicians were asked not to discuss the intervention with control group physicians. After that period, nine more studies attempted to protect against contamination (Brown 2001; Clark 2000; Glasgow 2004; Hobma 2006; Kennedy 2004; Krones 2008; Longo 2006; Moral 2003; Sorlie 2007). However, in the majority of studies, it was unclear or unlikely that protection against contamination was adequate (Alamo 2002; Bieber 2008; Briel 2006;Chenoweth 2009; Dijkstra 2006; Harmsen 2005; Haskard 2008; Heaven 2006; Ho 2008; Howe 1996; Joos 1996; Kinmonth 1998; Langewitz 1998; Levinson 1993; Lewis 1991; Loh 2007; Margalit 2005; McLean 2004; Meland 1997; Merckaert 2008; Pill 1998; Robbins 1979; Roter 1995; Smith 1998; Song 2005; Stewart 2007; Thom 1999; Wilkinson 2008). In five studies (Alder 2007; Chassany 2006; Fallowfield 2002; Smith 2006; Wolf 2008) potential for contamination was high, and no attempts were made to prevent or control it.

Potential for unit of analysis error for some outcomes

Thirty‐two of the studies included in this review (Alamo 2002; Alder 2007; Bieber 2008; Briel 2006; Chassany 2006; Chenoweth 2009; Clark 2000; Dijkstra 2006; Fallowfield 2002; Glasgow 2004; Harmsen 2005; Haskard 2008; Hobma 2006; Joos 1996; Kennedy 2004; Kinmonth 1998; Krones 2008; Levinson 1993; Lewis 1991; Loh 2007; Longo 2006; Margalit 2005; Meland 1997; Merckaert 2008; Moral 2003; Pill 1998; Putnam 1988; Roter 1995; Smith 1998; Stewart 2007; Thom 1999; Wilkinson 2008) randomized health providers or practices/clinics to intervention or control groups and then collected some data respectively at the level of the individual patient or provider. Standard statistical methods that do not account for the cluster effects that may arise in such data will result in the overestimation of the significance of the intervention. Five studies randomized health providers but either did not include patient clusters or did not analyse any patient level data (Heaven 2006; Ho 2008; Howe 1996; Langewitz 1998; Robbins 1979); and the remaining six were randomized by patient (Brown 2001; McLean 2004; Smith 2006; Song 2005; Sorlie 2007; Wolf 2008).

The potential for a unit of analysis error for some outcomes was acknowledged in only 19 of the studies that randomized providers or practices. (Briel 2006; Chassany 2006; Chenoweth 2009; Clark 2000; Dijkstra 2006; Fallowfield 2002; Glasgow 2004; Harmsen 2005; Haskard 2008; Joos 1996; Kennedy 2004; Kinmonth 1998; Krones 2008; Loh 2007; Longo 2006; Roter 1995; Stewart 2007; Thom 1999). However, 28 made adjustments for clustering in the analysis (Alder 2007; Bieber 2008; Briel 2006; Chassany 2006; Chenoweth 2009; Clark 2000; Dijkstra 2006; Fallowfield 2002; Glasgow 2004; Harmsen 2005; Haskard 2008; Howe 1996; Joos 1996; Kennedy 2004; Kinmonth 1998; Krones 2008; Levinson 1993; Lewis 1991; Loh 2007; Longo 2006; Margalit 2005; Merckaert 2008; Moral 2003; Putnam 1988; Roter 1995; Smith 1998; Stewart 2007; Thom 1999; Wilkinson 2008), while four made no such adjustments (Alamo 2002; McLean 2004; Pill 1998; Meland 1997). Although the potential unit of analysis error was not explicitly acknowledged in Hobma 2006, practices were stratified by possible effect modifiers identified by a panel of experts. Clustering is potentially a problem for those studies that randomized providers, due to the clustering effects that cannot be eliminated for patient‐level outcomes. However, when we describe cluster randomized trials in this review, we refer to those that randomized practices.

Baseline measurement

Baseline measures of health provider performance or patient outcomes were conducted in 37 studies and were not collected in six (Alamo 2002; Ho 2008; Lewis 1991; McLean 2004; Roter 1995; Wolf 2008). In 21 studies, no significant differences were found across study groups before the intervention (Alder 2007; Bieber 2008 (except lower depression scores in the non‐randomized comparison group); Briel 2006; Brown 2001; Chassany 2006; Dijkstra 2006; Glasgow 2004; Howe 1996; Joos 1996; Kinmonth 1998; Langewitz 1998; Meland 1997; Pill 1998 (except for two measures); Putnam 1988; Robbins 1979; Smith 1998; Smith 2006; Stewart 2007; Song 2005; Sorlie 2007; Thom 1999). Eight studies reported significant differences between intervention and control groups at baseline and adjustments were made for them (Clark 2000; Fallowfield 2002; Chenoweth 2009; Moral 2003; Harmsen 2005; Heaven 2006; Howe 1996; Wilkinson 2008). Although not tested for significance, baseline differences were accounted for in the main analyses in seven studies (Hobma 2006; Kennedy 2004; Levinson 1993; Loh 2007; Longo 2006; Margalit 2005; Merckaert 2008). The remaining study collected baseline data but did not test for differences at baseline (Haskard 2008).

Effects of interventions

Methodological issues in pooled results

Studies used a variety of measures in all four main outcome categories (consultation process, satisfaction, health behavior, health status). This made pooling results challenging.

Of the 43 included studies, 22 were cluster‐randomized trials. In these studies, for some of the outcomes the unit of randomisation was the same as the unit of analysis, necessitating no adjustment of the sample sizes due to a design effect. Examples of such outcomes include the mean percent of patients whose distress was recognized by a physician, or the mean frequency of using particular types of questions by a physician during patient visits. For other outcomes, the unit of analysis differed from the unit of randomisation, and the intra‐class correlation coefficient (ICC) was needed to adjust the sample sizes for the design effect. Such outcomes included the health status of patients treated by a physician when physicians were randomized to receive the intervention. Notably, only five (Chenoweth 2009; Kennedy 2004; Kinmonth 1998; Krones 2008; Loh 2007) out of the 22 studies had the ICC reported. In four additional studies (Briel 2006; Dijkstra 2006; Glasgow 2004; Harmsen 2005), ICCs were estimated for sample size calculations. Because the ICC was not reported in other relevant articles, and was not provided by authors after email inquiry, we excluded some outcomes from the meta‐analyses. The specific numbers of outcomes from studies included are shown in the summary of analyses of each group of outcomes (see 'Data and analyses'; and Table 2.)

Other methodological problems related to risk for bias were lack of random selection of the patients when physician‐directed programs were evaluated, risk of contamination between study groups, and within group as opposed to between group analyses ('Risk of bias in included studies'; Table 1; Table 7).

7. Studies with some variables excluded from meta‐analysis.

| Study | Type of Variable‐ continuous | Reason for exclusion |

| Glasgow 2004 | Health status | Inconsistency in published report of no significant differences between intervention and control groups for diabetes‐specific quality of life, but with point estimates and standard deviations inconsistent with this finding. |

| Kinmonth 1998 | Consultation Health status Patient satisfaction |

Need standard deviations |

| Langewitz 1998 | Patient satisfaction | Need ICCb |

| McLean 2004 | Consultation | Need standard deviations |

| Merckaert 2008 | Consultation | Methodological problem: patients chosen by physician; did not use some outcomes (selection bias ? health status) |

| Roter 1995 | Consultation | Need ICCb; Need actual scores, standard deviations, pre‐post |

| Smith 2006 | Health status | Need adjusted post scores with standard deviation |

| Stewart 2007 | Consultation Satisfaction Health status |

Need ICCb |

a) PAID‐2 (Problem Areas in Diabetes 2) A questionnaire for diabetes‐specific quality of life.

b) ICC: intra‐cluster correlation

In the Characteristics of included studies table (Notes field) we show both the unadjusted sample sizes, ICC used for calculation, DEFF, and adjusted sample sizes. As seen from the table, the values of ICC differ from study to study. When a value of ICC was not reported for a particular outcome, we used values reported for other outcomes (or their median) if reported in the same paper (for the same study). However, using ICC from another unrelated study was not judged appropriate; it would be unclear which value of ICC to use from a fairly wide range.

We did not undertake sensitivity analysis according to the absence of reported ICCs. Given the number of studies and the amount of missing data, results would be questionable. In summary, we chose a conservative approach. Where any ICC was mentioned in the paper, it was used, and we decided against using some arbitrary values in the absence of any information.

Pooled results by outcome category

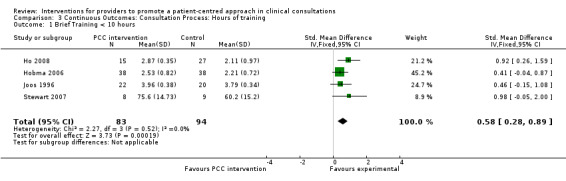

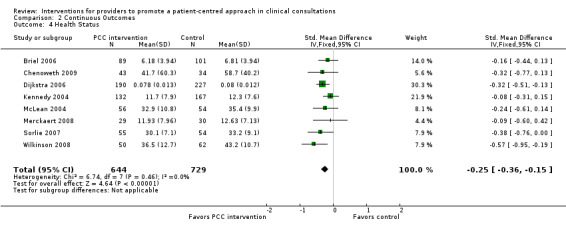

Outcome category A: Consultation processes

Summary: Outcomes measured varied across studies (see Table 3), with most measuring some aspect of consultation skills and behaviour (29 studies). Other outcomes included patient‐centred actions in the consultation, impact on the provider‐patient relationship, and impact on the consultation itself (usually duration). The studies in the pooled analysis showed mixed results. Analysis 2.1 Sixteen studies included in the pooled analyses reported a consultation process outcome. The majority of studies measured consultation skills or behaviours In the 4 studies that used dichotomous variables, the pooled analysis showed no effect (RR 0.96, 95%CI 0.82 to 1.13) due largely to the influence of the negative Roter 1995 study, Analysis 1.1, whereas the pooled analysis of the 12 of 16 studies using continuous variables favoured the intervention (SMD 0.70, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.82) Analysis 2.1. This is consistent with the descriptive analysis where three‐quarters of studies assessing consultation processes showed positive results with the remaining quarter indicating no effect or negative results.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Continuous Outcomes, Outcome 1 Consultation Process.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Dichotomous Outcomes, Outcome 1 Consultation Process.