Abstract

Objective:

To determine if the secretions collected from a conditionally reprogrammed primary endocervical cell culture are a suitable surrogate for mucus studies.

Design:

Experimental

Setting:

University research center

Animals:

emale rhesus macaque (n=2)

Intervention(s):

None

Main Outcome Measure(s):

Quantitative proteomic analysis using tandem mass tag (TMT) mass spectrometry (LC-LC/MS).

Results:

We identified 3047 proteins common proteins present in both primary endocervical cell cultures and rhesus macaque mucus. We found a 71% overlap in top 500 most prevalent proteins in the samples. Cell culture secretions contained many essential mucus proteins including mucin MUC5B, the primary mucin of the endocervix.

Conclusion:

The proteomes of mucus produced by conditionally reprogrammed primary endocervical cells are similar to the proteomes of whole mucus. These cultures present a promising model to study endocervical mucus production.

Keywords: Endocervix, Mucus, Primate, Proteome

Capsule:

Conditionally reprogrammed primary cells from the macaque endocervix produce mucus secretions that are similar to mucus collected directly from the cervix

Introduction

Endocervical mucus plays a key role in regulating the entry of sperm and other pathogens into the uterus and upper reproductive tract. Endocervical epithelial cells respond to estrogens and progestogens by altering the composition of cervical mucus so that it is thin and watery during fertile time points in the menstrual cycle and thick and scant during all others (1). In addition to fertility, secreted proteins play critical roles in mucus structure/rheology, immunology, and sperm capacitation (2,4). While there have been several studies assessing mucus composition throughout the cycle (4–6), we do not have a clear understanding of how mucus changes are mediated (2,3).

To facilitate experiments that could provide insight into mucus biology, we developed a primary cell culture model using Conditionally Reprogrammed Endocervical Cells (CREC) from the macaque endocervix (7). These cultures can be expanded and passaged robustly, allowing for in vitro experiments that previously were limited by short in vitro longevity (7,8). CRECs can also be differentiated to produce mucus and maintain hormonal sensitivity (7). CRECs produce mucins such as MUC5B, that serve as the scaffold for mucus’ gel-like property. However, we did not know if other proteins found in mucus collected directly from the macaque cervix were also seen in CRECs.

In this study, we used isobaric labeling quantitative proteomics to determine how closely mucus secreted by CRECs resembles that of whole mucus collected from the endocervix.

Methods

The Oregon Health and Science University Institutional Review Board approved this study. The Oregon National Primate Research Center (ONPRC), Division of Comparative Medicine provided the macaques. The ONPRC Animal Care and Use Committee approved all animal procedures. We followed recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health for all work.

Sample procurement

Figure 1 illustrates the overall methodology of sample procurement, processing, and analysis. We collected mucus and tissue samples from reproductive-aged female rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) (n=2) undergoing necropsy at ONPRC. Macaque samples represent early follicular (E2=16 pg/ml, P4=0.13 ng/ml) and luteal phase (E2=21 pg/ml, P4=1.64 ng/ml). To obtain mucus samples, we bi-valved the cervix, washed the luminal surface of the endocervix with 200 μl of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and then aspirated the luminal washings with 1 ml slip-tip insulin syringe.

Figure 1:

Study design. Mucus and tissue were collected from the endocervix of fresh necropsy specimens of the rhesus macaque. Tissue samples underwent conditional reprogramming with irradiated Swiss mouse fibroblasts 3T3J2 and Rho protein kinase (ROCK) inhibitor Y-27632 and were differentiated to produce mucus. Mucus from both conditionally reprogrammed endocervical cells (CRECs) and rhesus macaque were trypsin digested, labeled with tandem mass tags, separated with high pH reverse phase/low pH reverse phase liquid chromatography, and analyzed with Thermo Orbitrap Fusion (SPS MS3). Proteomic analysis workbench (PAW)/Comet pipeline provided peptide ID and protein inference; edgeR (Bioconductor) was used for differential expression testing. =

We previously described methods for generating primary cell cultures using conditional reprogramming (7). Briefly, we used a scalpel to separate endocervical cells from the underlying stromal tissue. We minced and washed the samples with 70% ethanol and enzyme digested the sample before filtering and plating the sample in a dish pre-plated with irradiated Swiss mouse 3T3 fibroblast feeder cells, along with a Rho protein kinase (ROCK) inhibitor Y-27632.

We differentiated the CRECs to produce mucus by moving the cells to polycarbonate permeable supports [Transwell (0.4 μm pore size), Corning] and changing the media to a serum-free differentiation medium (ReproLife CX, Lifeline Cell Technology) supplemented with calcium chloride (0.4mM, Sigma Aldrich). To examine hormone treatments on CREC mucus secretions, we mimicked conditions during mid-cycle and luteal phase by adding 17β estradiol (10−8 M, Sigma Aldrich) to the differentiation media for mid-cycle conditions, or 17β estradiol followed by progesterone (10−7 M, Sigma Aldrich) and 17β estradiol (10−9 M) for mid-luteal conditions (9,10). We also compared secretions from “short” cultures to “long” cultures. We exposed the medium every other day for 7 days for short treatments (n=2), or every other day for 21 days (n=2) or 26 days (n=2) days for long treatments.

Sample Processing and Analysis

We probe sonicated approximately 200 μl of each sample (macaque, n=2; CREC, n=6) in 4% SDS, 0.2% Deoxycholic acid, and 100 mM TEAB. We performed a Bicinchoninic acid protein assay and trypsin digested 55 μg of each sample. After peptide assay, we labeled 20 μg peptide digest of each sample with tandem mass tags (TMT10plex™ Isobaric Label Reagent Set and TMT11–131C Label Reagent, Thermo Scientific). After a pre-analysis normalization run to determine final mixing volumes, we fractionated the multiplexed sample with high pH reverse phase (30-fractions), followed by conventional low pH reverse phase, ionized with nano-electrospray, and analyzed on a Thermo Fusion Tribrid mass spectrometer. We collected the MS2 spectra with CID using linear ion trap and the reporter ions were generated using HCD after SPS MS3 enrichment.

We identified peptides and proteins using Comet (11) and the PAW pipeline (12) using a wider 1.25 Da parent ion mass tolerance and a canonical rhesus monkey protein database (21,211 sequences, UP000006718, release 2019.07). We used accurate mass conditional score histograms and target/decoy method to establish confident peptide identifications. We used the PAW pipeline to infer proteins, perform homologous protein grouping, establish peptide uniqueness, and sum unique peptide spectrum matches reporter ions into protein intensity totals. We performed differential expression testing using the Bioconductor package edgeR (13). Additional experimental details and description of the human cervical mucus samples have been reported (14) and the data are available at ProteomeXchange (dataset PXD021710).

Results

In total, we found 3047 proteins present in both CREC and whole mucus. Table 1 shows the most abundant proteins for each group. CRECs and whole mucus shared 357 (71%) of the top 500 (by protein reporter ion total signal) proteins and 10 (40%) of the top 25 proteins. The most abundant protein in all samples was serum albumin [UniProt: P02768]. Mucin 5B (MUC5B) [UniProt: Q9HC84] was the most prevalent mucin protein in both human and cell culture mucus. In addition to MUC5B, CREC also secretes MUC5AC [UniProt: P98088], MUC4 [UniProt: Q99102], MUC16 [UniProt: Q8WXI7], and MUC1 [UniProt: P15941], which are all found in human and macaque mucus samples (14). Other key endocervical mucus proteins present include leukocyte elastase inhibitor [UniProt: P30740] (15) and calcium-activated chloride channel regulator 1 (CLCA1) [UniProt: A8K7I4] (16). The most common Gene Ontology (GO) biological processes were immunity, post-translational modification, protein transport, cell adhesion, and proteolysis.

Table 1:

Top 25 most abundant proteins identified in conditionally reprogrammed endocervical cells and macaque mucus.

| CREC | UniProt Accession | Avg. reporter ion intensity (in millions) | GO: Biological Process | Whole Mucus | UniProt Accession | Avg. reporter ion intensity (in millions) | GO: Biological Process | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| metabolism, post translational protein | metabolism, post translational protein | |||||||

| 1 | Serum albumin | P02768 | 73.3 | modification | Serum albumin | P02768 | 149.9 | modification |

| 2 | Protein S100-A6 | P06703 | 65.4 | cell growth, cell-cell signaling | Protein S100-A8 | P05109 | 20.7 | immune response |

| 3 | Annexin A2 | P07355 | 48.8 | cell growth, collagen fibril organization | Mucin-5B (MUC-5B) | Q9HC84 | 20.2 | immune response |

| 4 | Ugl-Y3 Calcium-activated chloride channel |

P02751 | 44.5 | immune response, cell-cell signaling | Protein S100-A9 | P06702 | 19.1 | Immune response, cell-cell signaling |

| 5 | regulator 1 Aldo-keto reductase family 1 member |

A8K7I4 | 34.6 | transport | Complement C3c alpha’ chain fragment 2 | P01024 | 15.4 | immune response, cell-cell signaling |

| 6 | B10 | O60218 | 19.1 | metabolism, immune response | Spinorphin | P68871 | 15.3 | immune response |

| 7 | Annexin A1 | P04083 | 17.6 | hormone regulation | Hemoglobin subunit alpha Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate | P69905 | 13.1 | transport, stress response |

| 8 | Metalloproteinase inhibitor 1 | P01033 | 15.4 | metabolism, immune response | dehydrogenase (GAPDH) | P04406 | 11.7 | Immune response |

| 9 | 14-3-3 protein sigma | P31947 | 14.0 | homeostasis, keratinization | Short peptide from AAT | P01009 | 11.6 | acute phase response, hemostasis transport, iron ion homeostasis, protein |

| 10 | Leukocyte elastase inhibitor (LEI) | P30740 | 11.8 | immune response, stress response | Serotransferrin (Transferrin) | P02787 | 11.1 | regulation |

| 11 | Protein S100-A8 | P05109 | 10.5 | Immune response | Annexin A2 Calcium-activated chloride channel |

P07355 | 10.1 | cell growth, collagen fibril organization |

| 12 | Cathepsin D heavy chain | P07339 | 10.4 | Immune response | regulator 1 | A8K7I4 | 9.6 | transport |

| 13 | Complement C3c alpha’ chain fragment 2 | P01024 | 10.0 | Immune response, cell-cell signaling Immune response, epithelial cell | Pyruvate kinase PKM | P14618 | 9.0 | glycolytic enzyme |

| 14 | Galectin-3 (Gal-3) | P17931 | 10.0 | differentiation | Gelsolin | P06396 | 8.2 | biogenesis/degradation |

| 15 | Endoplasmic reticulum chaperone BiP | P11021 | 9.6 | homeostasis | Elongation factor 1-alpha 1 (EF-1-alpha-1) | P68104 A0A0G2JMS |

7.9 | protein regulation |

| 16 | Plectin (PCN; PLTN) | Q15149 | 9.6 | structural integrity | Uncharacterized protein Anterior gradient protein 2 homolog (AG-2; hAG-2) |

6 | 7.8 | protease inhibitor |

| 17 | Histone H4 | P62805 | 8.9 | metabolism, gene regulation transport, iron ion homeostasis, | Actin, cytoplasmic 1, N-terminally | O95994 | 7.7 | cell growth |

| 18 | Protein S100-A9 Actin, cytoplasmic 1, N-terminally |

P06702 | 8.9 | protein regulation | processed | P60709 | 7.5 | motility |

| 19 | processed | P60709 | 8.8 | motility | Alpha-enolase | P06733 | 7.4 | metabolism, immune response |

| 20 | Filamin-B (FLN-B) | O75369 | 8.6 | structural integrity | Truncated apolipoprotein A-I | P02647 | 7.3 | metabolism, transport, hormone regulation |

| 21 | Alpha-actinin-4 | O43707 | 8.4 | motility, | Protein S100-A6 | P06703 | 7.3 | cell growth, cell-cell signaling transport, immune response, stress |

| 22 | Alpha-enolase | P06733 | 8.1 | metabolism, immune response | Heat shock cognate 71kDa protein | P11142 | 7.2 | response, mRNA regulation |

| 23 | Profilin-1 | P07737 | 7.3 | motility | Myosin-9 | P35579 | 7.1 | intracellular organization |

| 24 | Laminin subunit alpha-3 | Q16787 | 7.3 | structural integrity | Triosephosphate isomerase (TIM) | P60174 | 6.2 | metabolism |

| 25 | Pyruvate kinase PKM | P14618 | 7.2 | glycolytic enzyme | Lactoferroxin-C | P02788 | 6.2 | immune response, transport |

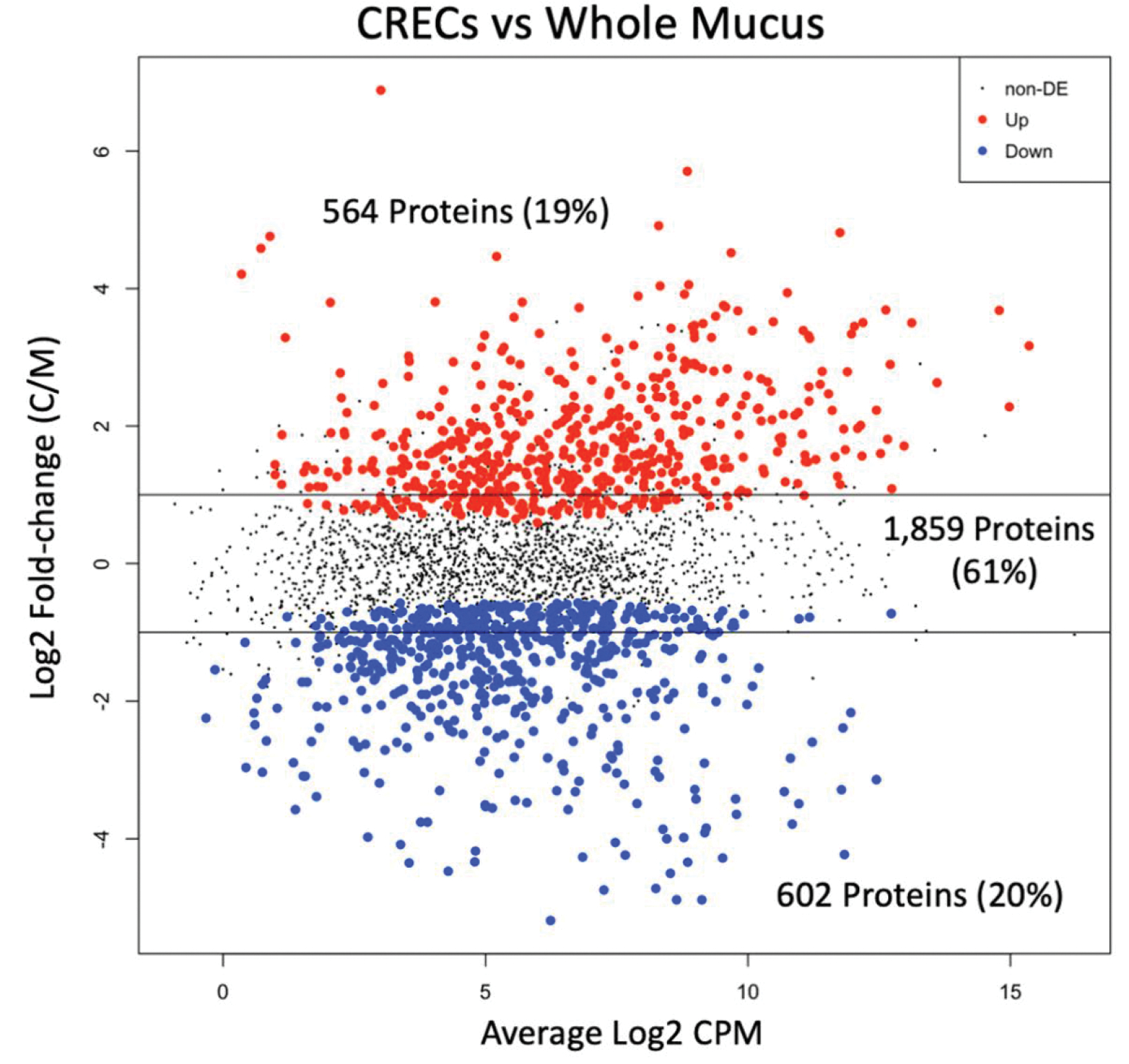

We found 1406 proteins to be differentially expressed (FDR<0.1). Figure 2 plots the 679 proteins with increased relative abundance in CRECs and the 727 proteins with increased relative abundance in whole mucus. We performed a functional annotation analysis using the Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID, https://david.ncifcrf.gov/) of the differentially expressed proteins with log fold change greater than 2. This included 191 proteins from CREC and 139 proteins from whole mucus. DAVID recognized 187 of 191 proteins from CREC and 132 of the 139 proteins from whole mucus. Overexpressed proteins in whole mucus contained more immunity related functions and the top GO process was innate immune response. Meanwhile, overexpressed proteins in CREC secretion were enriched in cell differentiation and proliferation terms.

Figure 2:

There are 564 proteins with increased relative abundance in conditionally reprogrammed endocervical cells (CRECs) and 602 proteins with increased relative abundance in whole mucus based on an edgeR exact test Benjamini-Hochberg corrected false discovery rate<0.05. DE 1⁄4 differentially expressed; CPM 1⁄4 counts per million; C/M 1⁄4 CREC intensity/mucus intensity.

Short-term culture and long-term cultures showed differences in secretions with 1400 (46%) differentially expressed candidates. We found greater overlap in proteins between whole mucus and long cultures than short cultures. Short CRECs cultures and whole mucus shared 163 proteins (33%) of the top 500 proteins compared to 353 (71%) of the long cultures. Using functional annotation analysis with DAVID, we found more proteins related to immunity in the long culture, while short cultures contained more proteins related to cell adhesion and extracellular matrix organization. CREC secretions under mid-cycle and luteal phase hormone treatment did not demonstrate statistically significant differently expressed candidates.

Discussion

The proteome of CREC secretions was comparable to those seen in whole mucus samples. We found a high degree of overlap between CRECs and whole mucus, and a very high concordance (>70%) when comparing the most abundant proteins. We also found that CRECs differentiated for longer in culture produced secretions that had protein profiles more similar to whole mucus. CREC secretions contain essential mucin and regulatory proteins that have roles in infection, and fertility (17). Taken together, our findings support the use of CRECs for in vitro studies of mucus production.

An in vitro model to study endocervical mucus would be invaluable to understanding how mucus changes are regulated and how secretions are altered by steroid signaling as well as novel drugs. Clinical studies in humans or studies with non-human primate (NHP) animal models are expensive, invasive, and difficult to control for endogenous hormonal confounding and biological variability (3). Moreover, drug discovery in clinical models is limited by safety and regulatory challenges. Lower order models, like mice, do not have the same reproductive anatomy or menstrual cycles (18,19). Thus, an in vitro model that recapitulates in vivo like secretions would provide an inexpensive platform to perform mechanistic studies of lower tract fertility regulation. These applications could extend to immune studies as well given the high quantity of immune proteins found in CREC secretions. Previous in vitro studies examining immune responses to common pathogens could be repeated in CRECs in order to measure variability of inflammatory response (20,21). Finally, one of the key benefits of using conditionally reprogrammed cultures is that they maintain genetic similarity to parent cells even after 30+ doublings, suggesting that in vitro experiments with CRECs would faithfully recapitulate their in vivo variations (8). CRECs could potentially be used a therapeutic model to both assess biological variability in secretions and fertility as well as test novel drugs taking into account personalized differences.

This limited pilot study did not account for biological variability seen among different animals or cell lines; however, this is the first proteomic comparison of in vitro endocervical cultures secretion to in vivo mucus. This study did not detect differences in secretions under estradiol only and estradiol and progesterone treatment. However, previous studies in CRECs (9) demonstrates expression of both estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor. We hypothesize that this is because mucus accumulation during the initial estradiol-only phase masks the subsequent progesterone effect, and more substantial washes of the cultures are needed in order to compare conditions. Further studies are needed to determine what aspects of the proteome are hormonally responsive in vitro.

Conclusion

In summary, this study demonstrated that proteins found in mucus produced by an in vitro conditionally reprogrammed endocervical cell culture share a significant number of proteins with whole mucus specimens. Additional studies are needed to characterize the changes in CREC secretions in response to hormonal changes to further validate their ability to recapitulate in vivo changes.

Table 2:

Top 25 differentially expressed proteins by fold change.

| CREC | Fold change | Whole Mucus | Fold change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Heat shock cognate 71 kDa protein | 118.3 | Immunoglobulin lambda constant 6 | 36.5 |

| 2 | Prostate stem cell antigen | 52.2 | Immunoglobulin lambda-like polypeptide 5 | 29.6 |

| 3 | Cornifin-B | 30.1 | Transthyretin | 29.6 |

| 4 | Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 5 | 28.1 | Bactericidal permeability-increasing protein (BPI) | 26.8 |

| 5 | Adhesion G protein-coupled receptor L2 | 27.1 | Antibacterial peptide LL-37 | 26.4 |

| 6 | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 L3 | 24.0 | Immunoglobulin lambda-like polypeptide 5 | 22.7 |

| 7 | Cornifin-B | 22.9 | Haptoglobin beta chain | 22.2 |

| 8 | Transmembrane protease serine 11E catalytic chain | 22.1 | Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 2 | 20.4 |

| 9 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein C-like 1 (hnRNP C-like-1) | 18.5 | Olfactomedin-4 (OLM4) | 20.3 |

| 10 | IL-8(9–77) | 16.6 | Coiled-coil domain-containing protein 168 | 20.2 |

| 11 | Sodium- and chloride-dependent neutral and basic amino acid transporter B(0+) | 16.4 | Immunoglobulin heavy constant gamma 2 | 19.4 |

| 12 | Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 6 | 15.3 | Immunoglobulin heavy variable 4–59 | 19.3 |

| 13 | Interferon-induced transmembrane protein 3 | 15.1 | Glutathione S-transferase A3 | 18.9 |

| 14 | Syndecan-4 (SYND4) | 14.8 | Spinorphin | 18.8 |

| 15 | Claudin-4 | 14.0 | HD5(63–94) | 18.1 |

| 16 | Arylsulfatase A component C | 13.9 | Ras GTPase-activating-like protein IQGAP2 | 17.0 |

| 17 | Nuclear receptor-interacting protein 1 | 13.9 | Ketimine reductase mu-crystallin | 16.6 |

| 18 | 27 kDa interstitial collagenase | 13.5 | Truncated apolipoprotein A-II | 16.0 |

| 19 | CD59 glycoprotein | 13.3 | Apolipoprotein D (Apo-D; ApoD) | 15.8 |

| 20 | Transmembrane glycoprotein NMB | 13.2 | Tetranectin (TN) | 15.7 |

| 21 | Galectin-3 (Gal-3) | 12.9 | Vitamin D-binding protein (DBP; VDB) | 15.1 |

| 22 | Ugl-Y3 | 12.8 | Tubulin polymerization-promoting protein family member 3 | 14.5 |

| 23 | Urokinase-type plasminogen activator chain B (U-plasminogen activator; uPA) | 12.8 | Calcyphosin | 14.4 |

| 24 | Quinone oxidoreductase PIG3 | 12.1 | Truncated apolipoprotein A-I | 13.8 |

| 25 | Kallikrein-7 (hK7) | 12.0 | Cilia- and flagella-associated protein 54 | 13.5 |

Funding:

This research received support from the grant K12 HD000849, awarded to the Reproductive Scientist Development Program by the NICHD. In addition, this work received funding from The March of Dimes Foundation, American Society for Reproductive Medicine and American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology as part of the RSDP, as well as the OHSU-School of Medicine, Medical Foundation of Oregon and ONPRC core grant number P51 OD011092. Mass spectrometry was done at the OHSU Proteomics Shared Resource with partial support from NIH grants P30EY010572, P30CA069533, and S10OD012246.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none

References

- 1.Moghissi K, Syner F, Evans T. A composite picture of the menstrual cycle. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1972;114:405–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Jonge C Biological basis for human capacitation—revisited. Hum Reprod Update 2017;23:289–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Han L, Taub R, Jensen JT. Cervical mucus and contraception: what we know and what we don’t. Contraception 96(2017):310–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grande G, Milardi D, Vincenzoni F, Pompa G, Biscione A, Astorri AL, et al. Proteomic characterization of the qualitative and quantitative differences in cervical mucus composition during the menstrual cycle. Mol Biosyst 2015;11(6):1717–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andersch-Björkman Y, Thomsson KA, Holmén Larsson JM, Ekerhovd E, Hansson GC. Large Scale Identification of Proteins, Mucins, and Their O-Glycosylation in the Endocervical Mucus during the Menstrual Cycle. Mol Cell Proteomics 2007;6(4):708–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Panicker G, Ye Y, Wang D, Unger ER. Characterization of the Human Cervical Mucous Proteome. Clin Proteomics 2010;6(1–2):18–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han L, Andrews W, Wong K, Jensen JT. Conditionally reprogrammed macaque endocervical cells retain steroid receptor expression and produce mucus. Biol Reprod 2020;102(6):1191–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu X, Krawczyk E, Suprynowicz FA, Palechor-Ceron N, Yuan H, Dakic A, et al. Conditional reprogramming and long-term expansion of normal and tumor cells from human biospecimens. Nat Protoc 2017;12(2):439–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buckner LR, Schust DJ, Ding J, Nagamatsu T, Beatty W, Chang TL, et al. Innate immune mediator profiles and their regulation in a novel polarized immortalized epithelial cell model derived from human endocervix. J Reprod Immunol 2011;92(1):8–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hombach-Klonisch S, Kehlen A, Fowler PA, Huppertz B, Jugert JF, Bischoff G, et al. Regulation of functional steroid receptors and ligand-induced responses in telomerase-immortalized human endometrial epithelial cells. J Mol Endocrinol 2005;34(2):517–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eng JK, Jahan TA, Hoopmann MR. Comet: An open-source MS/MS sequence database search tool. PROTEOMICS 2013;13(1):22–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilmarth PA, Riviere MA, David LL. Techniques for accurate protein identification in shotgun proteomic studies of human, mouse, bovine, and chicken lenses. J Ocul Biol Dis Infor 2009;2(4):223–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 2010;26(1):139–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han L, Park D, Reddy A, Wilmarth PA, Jensen JT. Comparing endocervical mucus proteome of humans and rhesus macaques. Proteomics Clin Appl 2021;15(4):e2100023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park J-A, He F, Martin LD, Li Y, Chorley BN, Adler KB. Human neutrophil elastase induces hypersecretion of mucin from well-differentiated human bronchial epithelial cells in vitro via a protein kinase C{delta}-mediated mechanism. Am J Pathol 2005;167(3):651–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nyström EEL, Birchenough GMH, van der Post S, Arike L, Gruber AD, Hansson GC, et al. Calcium-activated Chloride Channel Regulator 1 (CLCA1) Controls Mucus Expansion in Colon by Proteolytic Activity. EBioMedicine 2018;33:134–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barrios De Tomasi J, Opata MM, Mowa CN. Immunity in the Cervix: Interphase between Immune and Cervical Epithelial Cells. J Immunol Res 2019;2019:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cunha GR, Sinclair A, Ricke WA, Robboy SJ, Cao M, Baskin LS. Reproductive tract biology: Of mice and men. Differentiation 2019;110:49–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laffan SB, Posobiec LM, Uhl JE, Vidal JD. Species Comparison of Postnatal Development of the Female Reproductive System. Birth Defects Res 2018;110(3):163–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Radtke AL, Quayle AJ, Herbst-Kralovetz MM. Microbial products alter the expression of membrane-associated mucin and antimicrobial peptides in a three-dimensional human endocervical epithelial cell model. Biol Reprod 2012;87(6):132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buckner LR, Lewis ME, Greene SJ, Foster TP, Quayle AJ. Chlamydia trachomatis infection results in a modest pro-inflammatory cytokine response and a decrease in T cell chemokine secretion in human polarized endocervical epithelial cells. Cytokine 2013;63(2):151–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]