Abstract

The ability of research networks and individual institutions to effectively and efficiently prepare, respond, and adapt to emergent challenges is essential for the biomedical research enterprise. At the beginning of 2021, a special Working Group was formed by individuals in the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) consortium and approved by the CTSA Steering Committee to explore “Adaptive Capacity and Preparedness (AC&P) of CTSA Hubs.” The AC&P Working Group took a pragmatic Environmental Scan (E-Scan) approach of utilizing the diverse data that had been collected through existing mechanisms. The Local Adaptive Capacity framework was adapted to illustrate the interconnectedness of CTSA programs and services, while exposing how the demands of the pandemic forced them to quickly pivot and adapt. This paper presents a synopsis of the themes and lessons learned that emerged from individual sections of the E-Scan. Lessons learned from this study may improve our understanding of adaptive capacity and preparedness at different levels, as well as help strengthen the core service models, strategies, and foster innovation in clinical and translational science research.

Keywords: Clinical and translational research, Clinical and Translational Science Award Program, adaptive capacity, emergency preparedness, environmental scan

Introduction

The Environmental Context of CTSA Hubs

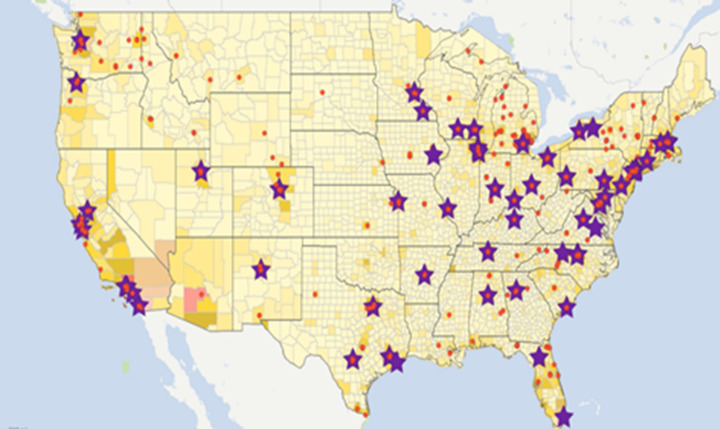

The Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) Program, funded by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), has been a flagship of the translational enterprise with the mission to speed the translation of research discoveries into improved patient care. Each institution that receives a CTSA is referred to as a “hub” that not only serves as the center of integrated research and training for clinical and translational science (CTS) in their local environments, but also coordinates and collaborates with multiple partner institutions (“spokes”) such as affiliated hospitals, clinics, and community organizations (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

NCATS CTSA Program: national network of medical research institutions (star) and partners (•).

Source: Kurilla, M. Clinical Science and COVID-19. Lecture presented at: MEDI 502 - Translational Science in the COVID-19 Pandemic - Accelerating and Enhancing our Response across Preclinical, Clinical and Population Health Research, 2021 Fall Term II, NCATS.

In the light of the explosive spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, the importance of leveraging this consortium of CTS organizations to respond to the health emergencies has become increasingly evident. The ability of the network and individual institutions to effectively and efficiently prepare, respond, and adapt to the emergent challenges is also positioned at the forefront of translational science and scientists. The pandemic has provoked changes to the direction and scope of programs conducted and services provided by the CTSAs, including CTS research, critical research support services, and workforce development. One of the roles of translational science is to document the lessons learned and disseminate “practices that work” from different settings [1, 2], especially during these unprecedented times. The CTSA Program consortium has a history of investigating opportunities that build capacity for best practices as a crisis evolves [3], and the COVID-19 crisis provides a unique opportunity to learn about adaptive capacities and strategies implemented by the CTSA hubs to address research needs and continue to impact the translational research enterprise (e.g., emerging community engagement and digital health opportunities, adaptive trial platform, remote/decentralized research, eConsent solutions, etc.).

Since the onset of the pandemic, NCATS and the University of Rochester Center for Leading Innovation and Collaboration (CLIC) have launched several efforts to understand the impact of COVID-19 on program hubs. CLIC created a Discussion Forum collaborative space with a Coronavirus Disease 2019 landing page and a COVID-19 tag to assist researchers and trainees in finding pandemic-related resources in the Educational Clearinghouse. In April of 2020, CLIC administered a survey for KL2 scholars and TL1 trainees to understand the immediate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on training and career development, and in October 2020, a CTSA hub survey on COVID-19 experiences was sent out as part of a collaboration between the CTSA Program Steering Committee and the Journal of Clinical and Translational Science [4].

In September 2020, CLIC hosted the “Virtual Un-Meeting: Clinical Research in the COVID-era and Beyond,” with discussions around the pandemic-driven changes in clinical and translational research, trial design opportunities, training, remote trials, the impact on recruitment, and the role of CTSA Program in clinical research during pandemics. The event participants voted for “Adaptive Strategies and Preparedness of Clinical and Translational Research” as one of the five key topic areas for discussion and future investigation. Some of the interesting points discussed in the Un-Meeting’s breakout rooms included such concepts as “elasticity,” “plasticity,” and “resilience” of CTS research institutions.

“Adaptive Capacity and Preparedness (AC&P) of CTSA Hubs” Working Group: Purposes, Uses, and Engagement

The abovementioned efforts brought to light some aspects of COVID-19’s impact on CTSA program hubs as it relates to their ability to rapidly respond to the pandemic but did not address the overall adaptiveness and preparedness of hubs to respond to a future crisis. Thus, at the beginning of 2021, a special Working Group (WG) was approved by the CTSA Steering Committee to explore “Adaptive Capacity and Preparedness (AC&P) of CTSA Hubs.” The AC&P WG participants represented multiple CTSA hubs, translational research and operations areas, and scientific disciplines (such as leadership, administration, workforce training, monitoring and evaluation, continuous improvement, research operations, and informatics). Broader stakeholder engagement was ensured by the inclusion of NCATS, the CTSA Steering Committee, and community organization representatives. The group also utilized the expertise and collaborations of relevant networks, such as the CTSA Steering Committee and relevant Working Groups and Forums, the Association for Clinical and Translational Science Special Interest Groups, and the American Evaluation Association Translational Research Evaluation Topical Interest Group, to explore and share both challenges in and strategies for building adaptive capacity and preparedness of CTSAs.

The AC&P Working Group took a pragmatic approach of utilizing the data that had been—or was planned to be—collected through existing mechanisms, aligning with and contributing to the goals and processes of the NCATS’ evolving process to document and disseminate how the CTSA Program prepares for and responds to a public health crisis. The overall purpose of the WG was not to evaluate, test, generalize, quantify, or validate any hypotheses, approaches, or interventions, but rather to identify, curate, analyze, and share diverse challenges, strategies, practices, and ideas for building adaptive capacity and preparedness of CTSAs across the goals outlined by NCATS for the CTSA program, its scientific sectors, and the translational research spectrum.

The instrumental and conceptual uses of the Working Group products are interlinked to include: (1) mitigating the impact of the COVID-19 crisis by adjusting programs, practices, and processes; (2) planning capacity building for “emergency ready and responsive” research and training; (3) optimizing strategic management, evaluation, and accountability of CTS programs; and (4) advancing translational science grounded in high-quality learning and improvement.

Adaptive Capacity and Related Concepts

In general terms, we understand and define “adaptive capacity” as the capacity of systems, institutions, humans, and other entities to adjust to potential damage, to take advantage of opportunities, or to respond to consequences (adapted from IPCC, 2014) [5]. A related concept that is key to enhancing adaptive capacity is “resilience,” i.e., “the capacity of social, economic, and environmental systems to cope with a hazardous event or trend or disturbance, responding or reorganizing in ways that maintain their essential function, identity, and structure, while also maintaining the capacity for adaptation, learning, and transformation” [6]. Adaptive capacity is inextricably linked to our capability to act collectively, which is largely affected by trust, social capital, and organization [6]. Folke et al. [7]. emphasize that:

“Systems with high adaptive capacity are able to re-configure themselves without significant declines in crucial functions in relation to primary productivity, …social relations and economic prosperity. A consequence of a loss of resilience, and therefore of adaptive capacity, is loss of opportunity, constrained options during periods of re-organization and renewal, an inability of the system to do different things.”

Building adaptive capacity is paramount in the context of emerging diseases, public health threats, and other environmental, physical, social, and political conditions; it is a prerequisite for sustainable program implementation and both effective and efficient adaptations depending on future circumstances. Johnson et al. [8] suggest that to successfully build adaptive capacity, it is necessary to examine human behavior theories, models, and lessons learned for better understanding stakeholder capabilities, perceptions, and preparedness for meaningful engagement and action. One of such approaches, Appreciative Inquiry, has been tacitly incorporated into the AC&P WG planning, data collection and analysis, interpretation, and dissemination efforts. Appreciative Inquiry is an approach seeking to improve performance and conditions by focusing on strengths rather than on weaknesses, which is rather different from many organizational change, continuous improvement, and evaluation approaches that focus on deficits and problems [9]. Cooperrider & Whitney [10] share the view that, “Appreciative Inquiry is about the coevolutionary search for the best in people, their organizations, and the relevant world around them. Appreciative Inquiry involves, in a central way, the art and practice of asking questions that strengthen a system’s capacity to apprehend, anticipate, and heighten positive potential.” Accordingly, Preskill & Catsambas [11] make the point that Appreciative Inquiry is “…a group process that inquires into, identifies and further develops the best of ‘what is’ in organizations in order to create a better future. …It is a means for addressing issues, challenges, changes and concerns of an organization in ways that build on the successful, effective and energizing experiences of its members.” Such strength-based, yet constructively critical, and forward-looking spirit and principles have grounded the AC&P WG’s approach—an Environmental Scan of challenges, issues, and practices in CTSA hubs’ preparedness and adaptation.

Methods

The Environmental Scan (E-Scan) Approach

The Working Group approach was implicitly designed as an Environmental Scan (E-Scan), a methodological approach that can be described as a systematic process of searching, collecting, analyzing, and using relevant and credible information from internal and external sources (environments) on their assets, processes, achievements, and shortcomings to inform strategic planning and decision making [12–14]. The AC&P E-Scan incorporated diverse data sources and methods as part of searching for COVID-19, emergency preparedness, response, and adaptation titles and content:

Scientific publications and white papers on CTSA AC&P-related activities

A mix of CTSA hubs’ websites: public stories, news, highlights, measures, etc.

NCATS, Center for Leading Innovation & Collaboration (CLIC), and other clinical and translational science organizations’ websites

Select CTSA hub Research Performance Progress Reports’ (RPPRs) de-identified information and COVID-19 reports featuring relevant highlights, accomplishments, challenges, metrics, etc.

JCTS COVID-19 Special Edition Survey’s select questions and responses related to AC&P

Experiences, perceptions, and expert opinions of the E-Scan implementers, reviewers, and stakeholders, and

Other Adaptive Capacity & Preparedness publications and resources (See Appendix A for more details).

E-Scan Structure/Framework

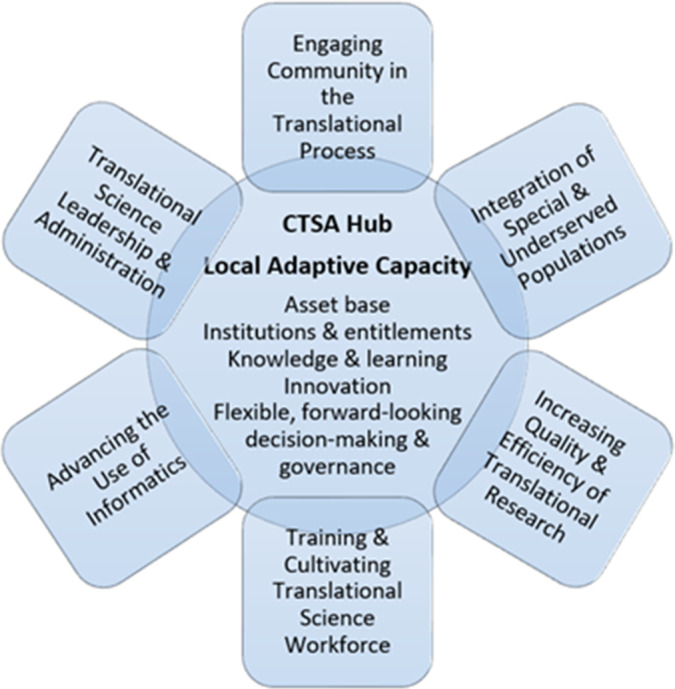

The E-Scan’s exploration and consideration of adaptive capacity and preparedness (see Fig. 2) was guided by the Local Adaptive Capacity Framework [15] and structured around the following CTSA Program goals:

Train and cultivate the translational science workforce;

Engage patients and communities in every phase of the translational process;

Promote the integration of special and underserved populations in translational research;

Innovate processes to increase the quality and efficiency of translational research; and

Advance the use of cutting-edge informatics.

Fig. 2.

Local adaptive capacity of CTSA hubs.

The WG decided that it was important to also consider an additional category of “Provide leadership and administration to advance translational science.” This category is not one of the official CTSA goals, and it is not immediately apparent within those program goals. However, this category is a key requirement and condition for implementing and achieving all CTSA goals. Indeed, the key focus of adaptive capacity, according to Parsons et al. [16], is “…on the potential for the facilitation of adaptation by governance, institutional, management and social arrangements and processes.”

Based on the available expertise and interest, six dedicated “Working Group subgroups” were formed to pursue an E-Scan within each of the above goals and areas. In our search and analysis of the evidence (“adaptive capacity and preparedness” lessons learned, practices that work, case studies, and recommendations relevant to the goals), we followed a combination of approaches and frameworks. Our evolving conceptual framework for AC&P drew on insights from across different disciplines and scientific perspectives. After thorough consideration of existing adaptive capacity frameworks, we decided to adapt a Local Adaptive Capacity (LAC) framework developed by Jones et al. [15] Informed by extensive consultations with academics, policy-makers, and practitioners, the LAC framework integrates resource-based, intangible, and dynamic dimensions of adaptive capacity; it is useful for understanding and assessing adaptive capacity at the local level (and, perhaps, beyond), monitoring progress, identifying needs, and coordinating resources to optimize preparedness and adaptation. LAC underpinnings and components are grounded in social science, systems thinking, and organizational theory; it is flexible and open to adaptations, based on organizational changes. Even though the LAC framework has been mostly utilized in the climate change arena, it pragmatically fits many other scientific and practitioner settings, including CTSA hubs (see Fig. 2).

The LAC framework (Table 1) incorporates five core characteristics (or, as we call them, domains), namely: asset base; institutions and entitlements; knowledge and information; innovation; and flexible, forward-looking decision-making and governance. These domains interact to determine the ways of and the degree to which individual CTSA hubs are prepared for and able to adapt to emergencies and other significant adverse changes. While these domains are necessarily interdependent, interacting, and overlapping, each of them serves a distinct role in CTSAs’ ability to adapt to and thrive under new adverse circumstances and beyond. The framework is also open to incorporating other domains to reflect specific organizational settings, conditions, and circumstances. We have adapted the “knowledge and information” domain by integrating a concept of “learning,” which is more comprehensive, flexible, and conducive to adaptive capacity development in the context of translational science, NCATS 3Ds (Developing, Demonstrating, Disseminating) approach [1, 17], and CTSA Program goals.

Table 1.

Local adaptive capacity domains and their features (adapted from Jones et al. [15])

| Adaptive capacity domains | Features that characterize a high adaptive capacity |

|---|---|

| Asset base | Availability of key assets that allow the system to respond to evolving circumstances |

| Institutions and entitlements | Existence of an appropriate and evolving institutional environment that allows fair access and entitlement to key assets and capitals |

| Knowledge, information, and learning | The system has the ability to collect, analyze, and disseminate knowledge and information to learn in support of adaptation activities |

| Innovation | The system creates an enabling environment to foster innovation, experimentation, and the ability to explore pragmatic solutions and to take advantage of opportunities |

| Flexible, forward-looking decision-making and governance | The system is able to anticipate, incorporate, and respond to changes with regards to its decision-making, governance and operational structures, and future planning |

The Working Group applied the LAC framework systematically to identify, curate, and analyze relevant evidence that represents different areas and members of the CTSA network. Following the NCATS 3Ds approach [1, 17], the Working Group implemented a comprehensive strategy for conceptualization, data collection, analysis, gathering timely feedback, and dissemination. Most of the WG activities were implemented in the collaborative space of Google Drive, which allowed enhanced sharing, communication, data/evidence curation, project administration, transparency, accountability, and real-time collaboration. The CTS community was engaged by reviewing and providing feedback via consultations with CTSA colleagues, expert and stakeholder reviews, feedback from the CTSA Steering Committee, and feedback discussions at conferences. Dissemination efforts (some implemented in 2021 and more planned for 2022) have been bidirectional, providing an opportunity for feedback and new information to accrue, including conference presentations, abstract publications, webinars, CLIC website posts, report presentation to the CTSA Steering Committee, and manuscripts submitted to the Journal of Clinical and Translational Science.

Results

Select Themes and Lessons Learned from the E-Scan Focus Areas

A wealth of broad themes and concrete lessons learned emerged from individual sections of the E-Scan that are relevant to the CTSA Program at local and national levels. Despite and in response to the pandemic-induced challenges, CTSAs rallied in their pursuit of local, regional, and national strategies to foster innovation and meet emergent needs. Numerous accounts described how individual hubs quickly moved to remote environments while simultaneously responding to increased needs for resources and services. Hubs found that years of NIH CTSA funding meant that some resources and services were ready to support the needs driven by the pandemic, while the uniqueness of the pandemic created new needs and unexpected stresses [18]. Lessons learned happened in real time, forcing hubs to evolve continuously during each wave of the pandemic.

The LAC framework helps to illustrate the interconnectedness of CTSA programs and services, while exposing how the demands of the pandemic forced them to quickly pivot and adapt. Lessons learned from this process aid our understanding of adaptive capacity and preparedness at different levels, as well as help strengthen the core service models and strategies and foster innovation in translational science in many CTSA Program areas. A synopsis of findings for all E-Scan focus areas is presented next.

Engaging Community in the Translational Process 1

Asset base

The success of responses and adaptations depends on such assets as trust in public authorities, trust in science, and the use of communication strategies to inform—and be informed by—the public at large and individual communities [19, 20]. CTSA’s efforts to strengthen community relationships [21] and deploy enhanced communications methods [22] have contributed to slowing the spread of the virus and implementing biomedical research. CTSA hubs are expected to further deepen trust-based community engagement and strengthen advocacy for health equity [23].

| AC&P approaches for community engagement |

|---|

| Building on, optimizing, and expanding existing connections and trust relationships. Maintaining bi-directional communication. Communicating clearly, effectively, honestly. Practicing attentive, responsive, active listening to—and learning from—the community. Using culturally appropriate, community-approved, respectful solutions. Integrating communities as equal partners in the entire research and leadership process. |

Institutions and entitlements

During emergencies and beyond, collaborative institutional and inter-institutional environments are key to managing fair and efficient access to essential assets and opportunities. CTSA hubs utilized and expanded their collaborative relationships with local community organizations, public health departments, coalitions, and other stakeholders [24, 25]. Research teams and community advocates require additional assistance to enable more impactful collaboration in CTS research and its equitable integration in all populations.

Knowledge, information, and learning

CTSA hubs have used various mechanisms to advance co-learning and co-sharing of knowledge, resources, tools, and experiences between academic professionals, patients, community partners, and other stakeholders [26, 27]. There is still significant room for bi-directional flow of information and learning, listening to community partners, understanding their levels of awareness, attitudes and beliefs towards research, and responding to their concerns and ideas.

Innovation

University researchers and community partners collaborated to develop evidence-based, inclusive, accessible, and culturally appropriate resources helping community members stay healthy, informed, and connected during the pandemic [28–30]. CTSA hubs utilized novel and enhanced remote-engagement and non-face-to-face strategies and leveraged video-conferencing and asynchronous communication technology to ensure timely communication between investigators, community partners, and study participants [31].

Flexible, forward-looking decision-making

CTSA experiences demonstrated that governance structures having community members as equal, trusted partners can facilitate rapid responses to crises, particularly those affecting rural communities and racial and ethnic minorities [23, 32]. Some experts believe that the core culture of clinical research has not significantly changed to properly integrate community stakeholders in all research processes and to ensure suitable responsiveness and adaptation when an emergency strikes [33].

Integration of Special and Underserved Populations (SUPs) in Translational Research 2

Asset base

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated health disparities for special and underserved populations, exposing mistrust towards public health and other authorities, medical research, and healthcare during a crisis. Relationship building and inclusion of SUP populations throughout the process of translational research may lead to the trust of vaccines, clinical trials, diagnostics, and other advances [34]. The literature suggests that there is a need for institutions to invest more resources that support the translational research enterprise and leverage federal and non-federal funding to foster integration and promote the health and well-being of SUP communities across the lifespan.

| AC&P approaches for integrating SUPs |

|---|

| Earning trust through community action, connections, and resources. Promoting SUP participation and recruitment in clinical trials. Optimizing access to information, programs, centers, toolkits, and new compensation models. Developing outreach strategies, resources, and technology solutions addressing specific needs of SUPs. Assessing and diversifying leadership, operations, workforce, data, and communication with SUPs. Engaging community/SUP partners in shaping priorities and research prospectively. |

Institutions and entitlements

Demographic diversity in clinical trials must be a reality [35], as well as easy access to information, data repositories, programs, centers, toolkits, etc. developed to increase SUP participation and recruitment [36]. Community integration resources, infrastructure, and initiatives need to be optimized to support the translational research enterprise’s ability to promote resilience in special and underserved populations, as well as their engagement in the problem-solving process—as co-creators, designers, implementers, or reviewers of the projects.

Knowledge, information, and learning

CTSA consortium’s challenging task has been to ensure that the translational research enterprise’s knowledge and data science tools are designed for accessibility for learning in underrepresented and special populations across the human lifespan. Generalizable knowledge has to be created from mixed qualitative and quantitative research methods that best align with the knowledge generation mechanisms of underrepresented and special populations [23, 37, 38].

Innovation

Overreliance on technology and other electronic-based methods further exclude SUPs from the research process. Hybrid outreach strategies that combine old and new methods may help bridge the digital divide, a growing gap that affects the underprivileged members of society who do not have adequate access to computers or the internet [39]. Institutions could focus on human-centered design to promote disaster resilience in underserved and special populations across the lifespan. To advance innovation, CTS researchers need to have the knowledge, attitudes, and skills to partner with and listen to community leaders and members most familiar with what communities need.

Flexible, forward-looking decision-making

Racial health inequities existing across the entire research spectrum can be addressed via careful need assessments and diversification of leadership, operations, workforce, data, approaches, and communication mechanisms with SUPs [23, 40, 41]. Institutions may benefit from greater engagement of community partners in shaping priorities and research prospectively (e.g., reviewing pilot project proposals) and a Board of Trustees that includes representatives from SUP communities across the lifespan to further transform and realize the translational research enterprise’s vision, mission, and values.

Increasing Quality and Efficiency of Translational Research 3

Asset base

CTSA activities caused by the pandemic became more visible. Successful adaptations, pivoting strategies, and resources developed during critical times are part of the asset base, e.g., formation of clinical trial review committees, adoption of appropriate safeguards and safety protocols [42]; critical role of deep regulatory knowledge, electronic submissions capabilities to the FDA for efficient access to experimental therapeutics, and nimble regulatory and legal resource reallocation [43]; and a substantial shift of institutional approaches in biorepository management to an enterprise-serving strategy [44].

| AC&P approaches for increasing quality and efficiency |

|---|

| Highlighting CTSA hub service portfolio. Maintaining and sharing robust adaptations, pivoting strategies, and resources developed during crisis. Leveraging pre-established collaborations, resources, and information. Adopting a “learning health system approach” to integrate scientists into care delivery processes and interdisciplinary networking. Optimizing approaches to expedite experimental therapeutics and other innovative potential solutions. Building transformative and adaptive capacity bolstered by continuous quality improvement. |

Institutions and entitlements

An interplay of local and regional considerations and capacities may influence clinical outcomes and linked research during emergencies. CTSA hubs leveraged pre-established collaborations and assets to provide uninterrupted service to research teams while ensuring staff safety. CTS institutions can be better prepared via: establishing organizational structures, acquiring equipment, preparing personnel, creating consensus-driven clinical protocols, aligning resources across a system [45], rapidly deploying resources, fostering trusting relationships among investigative and clinical care teams, and developing shared “play books” for facilitating research specimen collections and other activities [43].

Knowledge, information, and learning

Impactful knowledge generation and dissemination are indispensable, yet difficult to implement during emergencies. Select CTSA strategies in this area included: adopting a “learning health system approach” which integrates scientists into care delivery processes and interdisciplinary networking [46]; creating faster access for researchers to high-quality COVID-19 data; and providing COVID-19-focused research training [47, 48]. Learning was not restricted to the academic environment. At many CTSA hubs’ virtual Town Hall meetings and Community Forums, health and research experts shared with thousands of community members the evidence and resources needed to augment understanding of COVID-19 and research-related issues [49, 50].

Innovation

Responses to crises rely on expedited procedures but usual workflows, testing, and protocol reviews take time. In the context of most staff and committee operations being successfully transitioned to remote conduct, CTSA hubs helped investigators navigate new options such as electronic consent, shipping study drugs to participants, and starting in-home research visits [51]. For example, IRB-approved COVID-19 studies could acquire study participants’ consent through electronic signature, and a UMN CTSI-developed special registry housed electronic medical records of COVID-19 patients to offer fast access to high-quality pandemic data for researchers [47]. Bolstered by robust standard operating procedures, proactive identification of key personnel, and cross-departmental collaboration real-time together and in parallel, Georgia CTSA’s Rapid Response Team coordinated 48-hour approval for treatment of coronavirus patients [52]. With both safety and quality in mind, hubs developed novel approaches to expedite experimental therapeutics, e.g., repurposing existing therapeutic interventions in the clinical setting [28].

Flexible, forward-looking decision-making

Crises put a strain on established systems that are often neither agile nor fit to respond to emergencies. Unfortunately, the broader system often rediscovers the same needs during a crisis, calling again for actions to be able to predict and be sufficiently prepared for the next one [53]. To make the CTS research enterprise agile and nimble, one that can sustain and advance the operations of the vast translational sciences enterprise, while addressing emergency needs, institutional leadership may follow these steps: (1) Say what you do (policies and SOPs governed by a capable management team); (2) Do what you say (program implementation and team training); (3) Prove it (monitoring and evaluation to ensure processes are followed and outcomes achieved); and (4) Improve it (addressing areas of concern) [54].

Training and Cultivating the Translational Science Workforce 4

| AC&P approaches for cultivating TS workforce |

|---|

| Leveraging existing, redesigned, and newly developed resources to facilitate continuity of both research and training agendas. Providing indirect and direct financial relief to trainees and researchers. Moving teaching/educational/mentorship activities to virtual platforms. Providing virtual: group mentoring hours, peer-mentoring, happy hours, networking sessions. Utilizing surveys on the impact of the emergency on trainees/scholars to inform adaptation activities. Emphasizing well-being, resilience, and critical skills for the translational science workforce. Conducting a needs assessment to redefine the characteristics of success in academia. Ensuring equity by monitoring demographic breakdowns in tenure/promotion and allocation of new teaching and service loads. |

Asset base

Since CTSA TL1 and KL2 training appointments are time-limited, developing and incorporating adaptations to the evolving circumstances of the pandemic was essential. Training, mentorship, and research—the trifecta of career development activities—were all required to be virtual or physically distant. While COVID-19-related challenges to training and cultivating the translational science workforce have been described previously [55], the environmental scan found that CTSA hubs were creative in identifying strategies to minimize disruptions caused by the pandemic. Many CTSA hubs leveraged existing, redesigned, and newly developed resources to facilitate the continuity of both research and training agendas [56, 57].

Institutions and entitlements

The pandemic caused traditional, in-person, educational activities to be reduced or canceled, which oftentimes led to a lack of interpersonal connectivity and decreased sense of a learning community in a mostly digital world. CTSA institutions provided access to physical, electronic, and digital/online resources to facilitate training activities and the conduct of human subjects research [58]. Most importantly, the pandemic showed that under such unprecedented conditions, additional support was required beyond the traditional mentor–mentee dyad to foster resiliency, such as providing virtual well-being resources, connecting trainees and scholars with 1:1 counseling, accommodating childcare responsibilities, and providing indirect/direct financial relief [59–61].

Knowledge, information, and learning

As most universities halted research operations entirely or prioritized COVID-19 research, trainees and scholars were concerned about how to continue their research, training, and other learning agendas. CTSA hubs leveraged informational technology and electronic, digital, and online resources for education. Online group forums and one-on-one meetings enabled ongoing exchange of information and learning, as well as opportunities for trainees to share their concerns, challenges, needs, and provide mutual assistance. CTSA hub surveys on the impact of the emergency on trainees/scholars were useful for informing adaptation activities [55].

Innovation

The move to the virtual platform also led to the implementation of innovative programs such as the CTSA Visiting Scholar Program that allowed KL2 Scholars to serve as virtual visiting professors and to expand their network beyond the home institution without the need to travel. The challenges of the COVID-19 crisis and associated isolation emphasized the importance of mentorship and social connectivity. Such novel activities like virtual dinners, group mentoring hours, happy hours, networking sessions, and virtual support groups provided these early career researchers and trainees the ability to retain and form new social connections needed for the next stage in their careers [62, 63].

Flexible, forward-looking decision-making

CTSA hubs demonstrated flexible, strategic decision-making in their provision of direct and indirect resources, in addition to leveraging existing assets, for allowing research and training projects to continue. For instance, some trainees and scholars were provided COVID-19 relief grants or supplements, took advantage of existing data sources (such as electronic health records) to allow research to continue with a pivot in focus, and/or were permitted to adjust the amount of protected research time to allow their career to continue to grow. Important considerations for institutional leadership include: expanding the range of products that “count” toward tenure and promotion; allowing for more individualized timelines for tenure and promotion; and ensuring equity by monitoring demographic breakdowns in tenure/promotion and allocation of new teaching and service loads [64].

Advancing the Use of Informatics 5

| AC&P approaches for advancing the use of informatics |

|---|

| Adapting existing resources for generating and managing information. Optimizing and expanding existing collaborations in research networks. Building centralized resources designed to aggregate and harmonize clinical data across organizations to enable rapid integration. Harmonizing data into a common data model across hubs, health systems, scientists, and other partners in different areas. Capturing informatics challenges and best practices to share via multiple channels. Utilizing pragmatic information technology solutions that help engage and inform the community about research. Creating collaborative, advanced analytics platforms and strategies to enable emergency-related data collection and novel analyses. Preparing collaborative analytics approaches and platforms for future emergencies. |

Asset base

Years of investments from NCATS allowed for informatics services and resources at CTSA Hubs to play a significant role in addressing the health crisis. Challenges included lack of sufficient, reliable clinical and research information during an emergency, and unharmonized data in multiple databases. CTSA hubs’ response strategies included adapting existing resources for generating and managing information, leveraging and expanding pre-established collaborations, and building centralized resources designed to aggregate/harmonize clinical data across organizations to enable rapid integration. The asset base available to the CTSA consortium and individual hubs in responding to the pandemics—and in need of focused capacity building—includes the following domains: governance, tools, common data models, data terminology standards, and training [18]. To prepare for a future crisis, Coller et al. [65] recommend the adoption of novel informatics platforms, hiring individuals with required informatics skills while considering work from home policies, and strengthening security, privacy, and technical capability of informatics platforms.

Institutions and entitlements

The pandemic exposed the lack of access for the clinical and research community to a wealth of clinical (COVID-19 including) data, sitting in widely distributed databases. A common-sensical, yet challenging to implement, strategy was to pool local resources and harmonize electronic health record (EHR) data into a common data model across hubs, health systems, scientists, and other partners in different areas. Coordinated efforts, such as the National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C), illustrate the power of the CTSA consortium and other partners to collectively support national needs in the aggregation and harmonization of clinical data, utilizing a collaborative analytics approach that can be adopted and adapted for addressing other health conditions and emergencies.

Knowledge, information, and learning

There was a significant increase in demand for data and resources related to the use of cutting-edge informatics. CTSA hubs and their health care and research partners have recognized the need for concerted efforts leading to the dissemination of newly found or optimized knowledge and information to biomedical and translational scientists, clinicians, patients, and other stakeholders. One of the approaches emphasized by NCATS and NIH has been the ongoing cultivation of a culture of Open Science and Data Sharing grounded in the FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) principles [17, 66]. It is essential to systematically capture challenges and best practices for informatics to share via multiple channels. For example, the CTSA Program’s CLIC pivoted to share successful practices and lessons learned from the CTSA Program Response to COVID-19, including those related to the use of cutting-edge informatics.

Innovation

Among common pandemic challenges were difficulties with engagement of diverse participant groups in pandemic-related and other research and a strong need for massive, interoperable clinical, and research data. Advancing their ability to innovate and find pragmatic solutions, CTSA hubs collaborated in the development of high-functioning participant recruitment and engagement platform to integrate a diverse participant population into COVID-19 vaccine trials, allowing research teams to track, analyze, and report study participation over time [67], as well as utilized their informatics infrastructure to create pandemic data dashboards [68].

Flexible, forward-looking decision-making

Capable decision-making and governance are needed to advance cutting-edge, ‘emergency-ready’ informatics platforms and strategies, enabling data generation, management, novel analyses, and communication—integrated into translational research, community engagement, and workforce training. There are key roles for informatics decision makers, teams, tools, policies, and resources in the following hub-suggested practices in the emergency context: developing a detailed plan to support research during any emergency; mobilizing key players for early collaboration; developing a central location for key information; communicating frequently and openly with the research community; and engaging the community effectively so they can become aware of the importance of clinical research and opportunities currently available.

Leadership and Administration to Advance Translational Science 6

Asset base

The speed and scope of the COVID-19 pandemic quickly emphasized the critical role of leadership and administration during a global pandemic. In practical terms, this meant coordinating access to resources, sharing knowledge, fostering innovation, and remaining flexible. CTSA hubs were asked to perform the dual task of supporting emerging translational science needs, while pivoting their existing services and resources to virtual environments. CTSA involvement in decision-making was instrumental in establishing dedicated COVID-19 diagnostic laboratories and research, obtaining funding, facilitating laboratory and clinical spaces, adjusting workflows to support improved timing for IRB review, and developing diagnostic tests for COVID-19 [70]. Derived from the JCTS COVID Special Edition Survey of CTSA hubs, some pragmatic, asset-related suggestions to prepare for another emergency include: having robust technology to support remote research and administrative activities; internal resources to track and evaluate the emergency; the ability to rapidly develop tools to understand local situations; and the availability of the institutional Critical Incident Management Team (CIMT) to create a cohesive, comprehensive approach to assessing and addressing emergencies.

Institutions and entitlements

Scientific and administrative leadership of the CTSA hubs and their partners worked together to align their response to the pandemic, and their institutions and communities benefited from pre-existing structures and relationships to share diverse resources, ideas, and strategies, e.g., via the Trial Innovation Network, the Recruitment Innovation Centers, Regional Tri-State Hubs [65, 67]. Widespread disruptions from the pandemic forced CTSAs to rethink informatics resources, administration of the TL1 and KL2 programs, and research at a time when most universities were shutting down [18, 55, 56].

| AC&P approaches for leadership and administration |

|---|

| Developing: technology solutions to support remote research and administrative activities; internal resources to track and evaluate the emergency; the ability to rapidly develop tools to understand local situations; and institutional emergency management teams. Utilizing and expanding existing collaborations and structures to share resources, ideas, and strategies. Developing robust mechanisms to share challenges and best practices with diverse stakeholders via multiple channels. Building evaluation and monitoring capacity for continuous organizational learning, improvement, and broader understanding of how to better adapt and prepare. Cultivating trustful partnership and shared decision making with other academic partners, medical centers, private partners, community clinics, citizen scientists, and special and underrepresented groups. |

Community partnerships helped address communication gaps with vulnerable and minority populations and provide concise and trustworthy information regarding COVID-19 prevention, testing, and the pandemic socioeconomic impact [34]. Access to consortia networks such as the Accrual to Clinical Trials (ACT) Network, National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network (PCORnet), and Consortium for Characterization of COVID-19 by EHR (4CE) helped to support access to much needed data [71]. The development of the National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C), helped to accelerate our understanding of COVID-19 and leveraged the principles of team science in sharing data during the pandemic [71].

Knowledge, information, and learning

Lessons learned from the shared living-through-COVID experience may serve as a primer for emergency preparedness and assist organizations to enhance their ability to respond to the next public health crisis. There are many examples of CTSA stakeholder communication during the pandemic (Community Forums, Town Halls, webinars, and other meetings), with the dialogue and mutual learning taking place between decision makers, researchers, and community members. CTSA-supported informatics collaboratives [22] have ensured that relevant pandemic data, information, and knowledge-related activities affecting communities and researchers are widely shared and coordinated. Rigorous evaluation and monitoring are indispensable for continuous organizational learning, improvement, and broader understanding of how to better adapt and prepare [72], bolstered by robust mechanisms for sharing knowledge across research teams, organizations, partners, and disciplines.

Innovation

Clinical and translational science “innovations developed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic deserve serious consideration for adoption as new standards, thus converting the painful trauma of the pandemic into ‘post-traumatic growth’” [65]. CTSA hub leadership and administration at various levels have contributed to identifying and materializing multiple novel solutions and innovations in the translational science enterprise in the areas of community engagement, communication, informational technology, collaboration, training, data generation, and sharing, etc. – practices that will continue to benefit the CTS workforce, research participants, communities, and other stakeholders.

Flexible, forward-looking decision-making

Five distinct elements to successful leadership during the COVID-19 crisis, highlighted by Shingler-Nance [73], are both simple and powerful: staying calm, communication, collaboration, coordinating, and providing support. Having experienced varying degrees of success in those areas, CTSA hub leaders have demonstrated that one of the greatest strengths was collaboration on the national and regional levels to strengthen networks of comprehensive support available to the research community all throughout the translational continuum. Trustful partnership and shared decision making with other academic partners, medical centers, private partners, community clinics, citizen scientists, and special and underrepresented groups are imperative to generate novel approaches and pragmatic solutions for complex issues across all populations.

Discussion

The environmental scan findings and discussions have highlighted the enormous challenges of a public health emergency; scientific/research opportunities that it presented; and creativity, flexibility, and optimism of the diverse teams of health professionals, clinical and translational science research teams, administration and information technology experts, and community organizations that worked hard to address those challenges and opportunities. The speed and scope of the COVID-19 pandemic quickly emphasized the critical role of leadership and administration during a global pandemic. In practical terms, this meant coordinating access to resources, sharing knowledge, fostering innovation, and remaining flexible. CTSA hubs were asked to perform the dual task of supporting emerging translational science needs, while pivoting their existing services and resources to virtual environments.

Common challenges created by the emergency include conducting research as universities shut down, sustaining programs, and services that traditionally occurred in person, the need for quick decision making and governance, support for underserved populations, and addressing the continuously evolving research and data requirements. Although the pandemic created considerable disruptions, many CTSA hubs demonstrated resilience in addressing emergent needs. Programs, services, and educational offerings quickly moved to virtual environments. Translational science leaders and scientists now realize that lessons learned from the pandemic would alter the way that institutions will operate in the future and that the adoption of new standards would foster growth and increase our collective adaptive capacity [46, 65]. Some of the challenges, lessons learned, and approaches across CTSA focus areas—grounded in the pandemic experiences and captured by the Environmental Scan—are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Challenges for CTSA hubs in the context of emergency, practices to address them, and lessons learned derived from the AC&P E-Scan (adapted from Volkov & Hoyo 75)

| Focus areas | Challenges identified | Practices and lessons learned | Adaptive capacity domains |

|---|---|---|---|

| Engaging communities | Uncertainty Lack of trust Miscommunication |

Building collaborative environments to manage fair and efficient access Bi-directional communication Attentive, responsive, active listening |

Institutions and entitlements |

| Integrating special and underserved populations | Mistrust of the research process Disproportionate burden, health disparities |

Overcoming reliance on sometimes exclusionary technology and methods Optimizing design for accessibility, specific needs |

Knowledge, information, and learning |

| Increasing quality and efficiency | Explaining a portfolio of CTSA mission, roles, services to internal and external collaborators Red tape hinders efficiency and innovation |

Improving visibility, flexibility, efficiency of CTSA services Facilitating novel/pragmatic approaches to expedite health care and research solutions |

Innovation |

| Cultivating translational workforce | Widespread disruption of research activities and training Institutional, structural and personal barriers |

Leveraging existing assets and capabilities Adapting traditional tools and technology to new conditions |

Assets |

| Informatics | Lack of sufficient, reliable clinical and research information Lack of engagement with diverse populations |

Developing massive, interoperable clinical/research data infrastructure Making concerted efforts to optimize knowledge dissemination |

Innovation |

| Leadership and administration | Critical need for coordinated response among widespread disruption | Collaborating to strengthen networks of comprehensive support for research community Cultivating trustful partnership and shared decision making |

Flexible, forward-looking decision-making |

To achieve a state of readiness to meet the challenges of this pandemic and future crises, the CTSA Program hubs must play an increasingly pivotal role in prioritizing studies and establishing the necessary research infrastructure in centers throughout the nation. We anticipate that the successful initiatives, which CTSA hubs led and collaborated on, will be further optimized, expanded, and leveraged on a large scale to fight the COVID-19 pandemic, syndemics, novel diseases, and any public health disasters and challenges. Truly engaged communities and stakeholders, new technological capabilities, goodwill, and newly acquired experience should allow us to build national and international collaborations and global infrastructure in the areas of public health and translational science. Being a forward-looking, catalytic member of the broad, global scientific community is a critical element of our national adaptive capacity and preparedness.

While the observations in this overview are not intended to generalize to other clinical and translational infrastructures, this environmental scan can help design principles, concepts, policies, and practices that would enable the clinical and translational science enterprise to respond and adapt to rapidly emerging needs at multiple levels. Future community-engaged research, guided by the LAC Framework and other promising models, may want to include additional sources of information that were outside of the scope of this scan, such as surveys of translational science stakeholders, comprehensive analysis of the organizational documents, and focus groups and interviews with community representatives and experts in the specific focus areas. Careful consideration and coordination by the translational science community are needed to better understand the current status of—and future directions for—our preparedness and adaptive capacity to make determined, effective efforts to deal with high-priority scientific and medical challenges, questions, and needs presented by emergencies and beyond.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to extend a special thank you for the expert review and stakeholder feedback provided by Jennifer Cieslak (Chief of Staff, the University of Minnesota Clinical and Translational Science Institute, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and Laura Meiners (Director of Operations, the Mayo Clinic Center for Clinical and Translational Science, Rochester, MN, USA). We also thank Ellen Champagne (Evaluation Project Manager, the Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research, University of Michigan, MI, USA), Verónica Hoyo (Executive Director, NNLM National Evaluation Center, Northwestern University Clinical and Translational Science Institute, Chicago, IL, USA), and Marie Kenny (Monitoring & Evaluation Specialist, the University of Minnesota Clinical and Translational Science Institute, Minneapolis, MN, USA) for their assistance with data collection and presentation. This work was supported, in part, through the following National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) grants: UL1TR002494, UL1TR003015, KL2TR002542. The authors acknowledge the support of the University of Rochester Center for Leading Innovation and Collaboration (CLIC), grant U24TR002260. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the contributors’ institutions, NCATS, or NIH.

Footnotes

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2022.400.

click here to view supplementary material

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1. Austin CP. Opportunities and challenges in translational science. Clinical and Translational Science 2021; 14(5): 1629–1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mehta TG, Mahoney J, Leppin AL, et al. Integrating dissemination and implementation sciences within clinical and translational science award programs to advance translational research: recommendations to national and local leaders. Journal of Clinical Translational Science 2021; 5(1): e151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cottler LB, Green AI, Pincus HA, et al. Building capacity for collaborative research on opioid and other substance use disorders through the clinical and translational science award program. Journal of Clinical Translational Science 2020; 4(2): 81–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Austin CP, Jonson S, Kurilla MG. Foreword to the JCTS COVID-19 special issue. Journal of Clinical Translational Science 2021; 5(1): e103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Core Writing Team RKP and LAM. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Geneva: IPCC, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6. IPCC. Annex II: Glossary [Mach, K.J., S. Planton and C. von Stechow (eds.)]. In: Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change ([Core Writing Team, R.K. Pachauri and L.A. Meyer (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 2014) pp. 117–130. (https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/AR5_SYR_FINAL_Annexes.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- 7. Folke C,Carpenter S, Elmqvist T, Gunderson L, Holling CS, Walker B. Resilience and sustainable development: building adaptive capacity in a world of transformations. AMBIO A Journal of the Human Environment 2002; 31(5): 437–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Johnson FA, Eaton MJ, Mikels-Carrasco J, et al. Building adaptive capacity in a coastal region experiencing global change. Ecology and Society 2020; 25(3): 1–22.32523609 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Better Evaluation. Appreciative inquiry. Accessed April 27, 2021. (https://www.betterevaluation.org/en/plan/approach/appreciative_inquiry)

- 10. Cooperrider DL, Whitney DK. Appreciative Inquiry: A Positive Revolution in Change. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Preskill HS, Catsambas TT. Reframing Evaluation through Appreciative Inquiry. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Charlton P, Doucet S, Azar R, et al. The use of the environmental scan in health services delivery research: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 2019; 9(9): e029805. DOI 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Volkov B, Gibbens B, Wakefield M. An environmental scan of health and health care in North Dakota: establishing the baselines for positive health transformation, 2009. (https://ruralhealth.und.edu/assets/1792-6616/vol1-2.pdf)

- 14. Wilburn A, Vanderpool RC, Knight JR. Environmental scanning as a public health tool: Kentucky’s human papillomavirus vaccination project. Preventing Chronic Disease 2019; 13(8): E109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jones L, Ludi E, Levine S. Towards a characterisation of adaptive capacity: a framework for analysing adaptive capacity at the local level, 2010. (https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2782323)

- 16. Parsons M, Glavac S, Hastings P, et al. Top-down assessment of disaster resilience: a conceptual framework using coping and adaptive capacities. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2016; 19: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 17. NCATS. PAR-21–293: Clinical and Translational Science Award (UM1 Clinical Trial Optional). Bethesda, MD: National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bookman RJ, Cimino JJ, Harle CA, et al. Research informatics and the COVID-19 pandemic: challenges, innovations, lessons learned, and recommendations. Journal of Clinical Translational Science 2021; 5(1): 1–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Han Q, Zheng B, Cristea M, et al. Trust in government regarding COVID-19 and its associations with preventive health behaviour and prosocial behaviour during the pandemic: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Psychological Medicine 2021: 1–11. DOI 10.1017/S0033291721001306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kalichman SC,Shkembi B, Kalichman MO, Eaton LA. Trust in health information sources and its associations with COVID-19 disruptions to social relationships and health services among people living with HIV. BMC Public Health 2021; 21(1): 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Office of Academic Clinical Affairs. Building Trust in Science through Power of Partnerships. Minneapolis, MN: Clinical and Translational Science Institute, University of Minnesota, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 22. IPIC. IPIC.org – Home. Published 2020. Accessed March 15, 2021. (https://www.pandemiccollaborative.org/)

- 23. Eder MM, Millay TA, Cottler LB. A compendium of community engagement responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Clinical Translational Science 2021; 5(1): e133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Carrasquillo O, Kobetz-Kerman E, Behar-Zusman V, et al. 46213 Florida community-engaged research alliance against COVID-19 in disproportionately affected communities (FL-CEAL): addressing education, awareness, access, and inclusion of underserved communities in COVID-19 research. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science 2021; 5(s1): 80–81. DOI 10.1017/cts.2021.609. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. NIH Community Engagement Alliance. Community benefits of COVID-19 research: an overview for community members, 2021. (https://covid19community.nih.gov/sites/default/files/2021-03/Community_Benefits_COVID-19_Research.pdf)

- 26. Barlow E. Five questions with Maurizio fava – Harvard catalyst. Harvard Catalyst News & Highlights, 2020. (https://catalyst.harvard.edu/news/article/five-questions-with-maurizio-fava/)

- 27. RIC. RIC COVID-19. Recruitment + retention toolkit (updated). Trial innovation network, 2021. (https://trialinnovationnetwork.org/material-details/?ID=144)

- 28. MICHR. Existing drugs kill SARS-CoV-2 in cells – MICHR. COVID-19, stories of impact, 2021. (https://michr.umich.edu/news/2021/8/23/existing-drugs-kill-sars-cov-2-in-cells)

- 29. CTSA Program Meeting 2021. TNN (The New Normal Campaign) TNN: we’re making history, 2021. (https://clic-ctsa.org/events/2021-virtual-ctsa-annual-meeting)

- 30. Hoedeman M. Keeping Indigenous communities connected during the pandemic, 2021. (https://ctsi.umn.edu/news/keeping-indigenous-communities-connected-during-pandemic)

- 31. Poger JM, Murray AE, Schoettler EA, Marin ES, Aumiller BB, Kraschnewski JL. Enhancing community engagement in patient-centered outcomes research: equipping learners to thrive in translational efforts. Journal of Clinical Translational Science 2021; 5(1): e172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Murphy T, Pointer K, Robinson RH, et al. Sustainable response to the COVID pandemic in an urban underserved community in Buffalo, New York. In: 2020 Fall Virtual Clinical and Translational Science Award Program Meeting, 2020.

- 33. Grumbach K, Cottler LB, Brown J, et al. It should not require a pandemic to make community engagement in research leadership essential, not optional. Journal of Clinical Translational Science 2021; 5(1): 95–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wieland ML, Asiedu GB, Lantz K, et al. Leveraging community engaged research partnerships for crisis and emergency risk communication to vulnerable populations in the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Clinical Translational Science 2021; 5(1): 6–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chastain DB, Osae SP, Henao-Martínez AF, Franco-Paredes C, Chastain JS, Young HN Racial disproportionality in COVID clinical trials. The New England Journal of Medicine 2020; 383(9): e59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nana-Sinkam P, Kraschnewski J, Sacco R, et al. Health disparities and equity in the era of COVID-19. Journal of Clinical Translational Science 2021; 5(1): e99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. BACHAC. Stanford COVID-19 Community Outcomes (COCO) Survey. Redwood City, CA: Bay Area Community Health Advisory Council, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bohn K. COVID-19: the urgency of engaging during crisis. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science 2021; 5(s1): 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Miller HN, Charleston J, Wu B, et al. Use of electronic recruitment methods in a clinical trial of adults with gout. Clinical Trials 2021; 18(1): 92–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hardeman R, Medina E, Boyd R. Stolen breaths. The New England Journal of Medicine 2020; 383(3): 71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. UCSF, Clinical & Translational Science Institute. COVID Research Patient and Community Advisory Board in Motion & Receives PCORI Funding. San Francisco, CA: UCSF, Clinical & Translational Science Institute, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 42. UC Davis Health. CTSC is a Quiet Hero of UC Davis COVID-19 Research. Sacramento, CA: UC Davis Health, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Weatherwax K, Gravelin M, Wright J, et al. Role of CTSA institutes and academic medical centers in facilitating preapproval access to investigational agents and devices during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Clinical Translational Science 2021; 5(1): 94–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Croker JA, Patel R, Campbell KS, et al. Building biorepositories in the midst of a pandemic. Journal of Clinical Translational Science 2021; 5(1): 92–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Auld SC, Caridi-Scheible M, Blum JM, et al. ICU and ventilator mortality among critically ill adults with coronavirus disease 2019. Critical Care Medicine 2020; 48(9): E799–E804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mendez A. At the Speed of ‘Pandemic’. Minneapolis, MN: Medical School, University of Minnesota, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Blazar B. How We’re Supporting Researchers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Minneapolis, MN: Clinical and Translational Science Institute, University of Minnesota, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Clinical and Translational Science Institute, University of Minnesota. Helping Researchers Test New COVID-19 Treatments Quickly. Minneapolis, MN: Clinical and Translational Science Institute, University of Minnesota, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Research Office, Stanford Medicine. Message from Dr. Ruth O’Hara, Senior Associate Dean for Research. Stanford, CA: Stanford Medicine, Research Office Bulletin. Accessed April 12, 2021. (https://med.stanford.edu/researchoffice/about/news/message-from-dr-ruth-ohara-senior-associate-dean-for-research.html) [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lawler L. COVID-19 research community forum – Harvard catalyst, 2020. (https://catalyst.harvard.edu/news/article/covid-19-research-community-forum/)

- 51. Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative (CTSC). Impact of COVID-19 on the Clinical Research Professional Workspace: Perspectives across the CTSC. Cleveland, OH: Case Western Reserve University, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Georgia Clinical and Translational Science Alliance. Georgia CTSA Rapid Response Team Coordinates 48-Hour Approval for Treatment of Coronavirus Patient. Atlanta, GA: Georgia Clinical and Translational Science Alliance, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Greenberg R, Greenberg RG, Poole L, et al. Response of the trial innovation network to the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Clinical Translational Science 2021; 5(1): 100–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bhatt A. Quality of clinical trials: a moving target. Perspectives in Clinical Research 2011; 2(4): 124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. McCormack WT, McCormack WT, Bredella MA, et al. Immediate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on CTSA TL1 and KL2 training and career development. Journal of Clinical Translational Science 2020; 4(6): 556–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Fattah L, Peter I, Sigel K, Gabrilove JL. Tales from New York City, the pandemic epicenter: a case study of COVID-19 impact on clinical and translational research training at the Icahn School of medicine at Mount Sinai. Journal of Clinical Translational Science 2020; 5(1): 258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sohrabi C, Mathew G, Franchi T, et al. Impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on scientific research and implications for clinical academic training – a review. International Journal of Surgery 2021; 86: 57–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Triemstra JD, Haas MRC, Bhavsar-Burke I, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the clinical learning environment: addressing identified gaps and seizing opportunities. Academic Medicine 2021; 96(9): 1276–1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bredella MA, Ferrone CR, Tannous BA, Patel KA, Levy AS, Bouxsein ML Promoting women in academic medicine during COVID-19 and beyond. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2021; 36(10): 3292–3294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Buch KA, Daye D, Wood MJ, et al. Wellness program implementation in an academic radiology department: determination of need, organizational buy-in, and outcomes. Journal of the American College of Radiology 2021; 18(5): 663–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Margolis RD, Berenstain LK, Janosy N, et al. Grow and advance through intentional networking: a pilot program to foster connections within the women’s empowerment and leadership initiative in the society for pediatric anesthesia. Paediatric Anaesthesia 2021; 31(9): 944–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. DePierro J, Katz CL, Marin D, et al. Mount Sinai’s center for stress, resilience and personal growth as a model for responding to the impact of COVID-19 on health care workers. Psychiatry Research 2020; 293: 113426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lamming DW, Carter CS. Maintaining a scientific community while social distancing. Translational Medicine of Aging 2020; 4: 55–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Butler T. Tenure clock extensions aren’t enough to help support researchers and their work during the pandemic (opinion). Inside higher ed, 2021. (https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2021/01/19/tenure-clock-extensions-arent-enough-help-support-researchers-and-their-work)

- 65. Coller BS,Buse JB, Kimberly RP, Powderly WG, Zand MS Re-engineering the clinical research enterprise in response to COVID-19: the clinical translational science award (CTSA) experience and proposed playbook for future pandemics. Journal of Clinical Translational Science 2021; 5(1): 1–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. NIH. NIH strategic plan for data science, 2018. (https://datascience.nih.gov/sites/default/files/NIH_Strategic_Plan_for_Data_Science_Final_508.pdf)

- 67. CLIC. Preparedness, capacity, and adaptability at the NYU CTSI in the time of COVID-19, 2020. (https://clic-ctsa.org/news/preparedness-capacity-and-adaptability-nyu-ctsi-time-covid-19)

- 68. DeGennaro S, Lee CR, Wahl P, et al. Miami clinical and translational science institute: leading a collaborative effort to facilitate COVID-19 research and education for researchers and community stakeholders. In: 2020 Fall Virtual Clinical and Translational Science Award Program Meeting, 2020.

- 69. Ragon B, Volkov BB, Pulley C, Holmes K. Using informatics to advance translational science: environmental scan of adaptive capacity and preparedness of Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program hubs. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science 2022; 1–23. DOI 10.1017/cts.2022.402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Jayaweera D, Flume PA, Singer NG, et al. Prioritizing studies of COVID-19 and lessons learned. Journal of Clinical Translational Science 2021; 5(1): 106–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Haendel MA, Chute CG, Bennett TD, et al. The national COVID cohort collaborative (N3C): rationale, design, infrastructure, and deployment. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2021; 28(3): 427–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Pringle P. AdaptME toolkit: adaptation monitoring and evaluation, 2011. (www.ukcip.org.uk/adaptme-toolkit/)

- 73. Shingler-Nace A. COVID-19: when leadership calls. Nurse Lead 2020; 18(3): 202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Volkov BB, Ragon B, Holmes K, Samuels E, Walden A, Herzog K. Leadership and administration to advance translational science: environmental scan of adaptive capacity and preparedness of Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program hubs. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science 2022; 1–26. DOI 10.1017/cts.2022.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Volkov BB, Hoyo V. 460 adaptive capacity and preparedness of CTSAs: the environmental scan approach and findings. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science 2022; 6(s1): 91–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Volkov BB, Hoyo V, Hunt J. Engaging community in the translational process: environmental scan of adaptive capacity and preparedness of Clinical and Translational Science Award Program Hubs. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science 2022; 1–26. DOI 10.1017/cts.2022.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Hoyo V, Shah RC, Dave G, Volkov BB. Integrating special and underserved populations in translational research: Environmental scan of adaptive capacity and preparedness of Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program hubs. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science 2022; 6(1): e89. DOI 10.1017/cts.2022.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Shah RC, Hoyo V, Moussatche P, Volkov BB. Improving quality and efficiency of translational research: environmental scan of adaptive capacity and preparedness of Clinical and Translational Science Award Program Hubs. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science 2022; 1–29. DOI 10.1017/cts.2022.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Bredella MA, Volkov BB, Doyle JM. Training and cultivating the translational science workforce: Responses of Clinical and Translational Science Awards program hubs to the COVID-19 pandemic. Clinical and Translational Science 2022; 1–7. DOI 10.1111/cts.13437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2022.400.

click here to view supplementary material