This 20-year follow-up of a randomized clinical trial reports the long-term associations of early intervention services compared with treatment as usual for individuals with first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorder.

Key Points

Question

What are the very long-term associations of early intervention services vs treatment as usual among individuals with first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorder?

Findings

In this follow-up study of a randomized clinical trial, no clinical associations of 2 years of early intervention services compared with treatment as usual among 164 individuals with diagnosed schizophrenia spectrum disorders at 20 years were found.

Meaning

New initiatives are needed to maintain the positive outcomes achieved after early intervention services and further improve very long-term outcomes among individuals diagnosed with first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorder.

Abstract

Importance

The OPUS 20-year follow-up is the longest follow-up of a randomized clinical trial testing early intervention services (EIS) among individuals with first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorder.

Objective

To report on long-term associations of EIS compared with treatment as usual (TAU) for first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorder.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A total of 547 individuals were included in this Danish multicenter randomized clinical trial between January 1998 and December 2000 and allocated to early intervention program group (OPUS) or TAU. Raters who were blinded to the original treatment performed the 20-year follow-up. A population-based sample aged 18 to 45 years with first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorder were included. Individuals were excluded if they were treated with antipsychotics (>12 weeks prior to randomization), had substance-induced psychosis, had mental disability, or had organic mental disorders. Analysis took place between December 2021 and August 2022.

Interventions

EIS (OPUS) consisted of 2 years of assertive community treatment including social skill training, psychoeducation, and family involvement by a multidisciplinary team. TAU consisted of the available community mental health treatment.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Psychopathological and functional outcomes, mortality, days of psychiatric hospitalizations, number of psychiatric outpatient contacts, use of supported housing/homeless shelters, symptom remission, and clinical recovery.

Results

Of 547 participants, 164 (30%) were interviewed at 20-year follow-up (mean [SD] age, 45.9 [5.6] years; 85 [51.8%] female). No significant differences were found between the OPUS group compared with the TAU group on global functional levels (estimated mean difference, −3.72 [95% CI, −7.67 to 0.22]; P = .06), psychotic symptom dimensions (estimated mean difference, 0.14 [95% CI, −0.25 to 0.52]; P = .48), and negative symptom dimensions (estimated mean difference, 0.13 [95% CI, −0.18 to 0.44]; P = .41). The mortality rate was 13.1% (n = 36) in the OPUS group and 15.1% (n = 41) in the TAU group. Likewise, no differences were found 10 to 20 years after randomization between the OPUS and TAU groups on days of psychiatric hospitalizations (incidence rate ratio, 1.20 [95% CI, 0.73-1.20]; P = .46) or number of outpatient contacts (incidence rate ratio, 1.20 [95% CI, 0.89-1.61]; P = .24). Of the entire sample, 53 participants (40%) were in symptom remission and 23 (18%) were in clinical recovery.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this follow-up study of a randomized clinical trial, no differences between 2 years of EIS vs TAU among individuals with diagnosed schizophrenia spectrum disorders at 20 years were found. New initiatives are needed to maintain the positive outcomes achieved after 2 years of EIS and furthermore improve very long-term outcomes. While registry data was without attrition, interpretation of clinical assessments are limited by high attrition rate. However, this attrition bias most likely confirms the lack of an observed long-term association of OPUS with outcomes.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00157313

Introduction

Schizophrenia is considered a major public health challenge by the World Health Organization due to years lived with disabilities1 and reduced life expectancy.2 The lifetime risk for receiving a diagnosis of schizophrenia has been estimated to be 1.8%.3

A recent review including 16 studies with at least 15 years of follow-up found individuals with schizophrenia to have a poorer long-term prognosis than individuals diagnosed with other schizophrenia spectrum disorders4 with inconsistencies of good outcomes ranging from 8% to 74%.4 Also, meta-analyses on recovery after a schizophrenia diagnosis have been inconsistent with rates ranging from 14% to 57%.5,6,7,8 Several individual cohort studies among individuals with first-episode psychosis have in general found bleaker and less favorable outcomes among individuals with schizophrenia compared with affective disorders and other related psychoses after 10 years9,10 and 20 years.11

Over the past 20 years, specialized early treatment facilities have been implemented targeting patients experiencing first-episode psychosis, including schizophrenia, and randomized clinical trials (RCTs) have found short-term positive clinical effects on symptom severity, psychiatric hospitalizations, and involvement in school and work when testing early specialized interventions.12 Yet, none of these studies have reported effects longer than 5 years after inclusion.

It has been hypothesized that the first years after the onset of psychosis is critical.13,14 During this period, it has been argued that symptoms are more malleable and therefore more receptive to intervention.13,14 Further, as it has been shown that symptoms in the early course of illness are associated with the later outcome, treatment in this time window should improve outcomes in the long term

To date, the Danish OPUS trial (NCT00157313) is the longest RCT testing 2 years of early intervention services (EIS) among individuals with a first episode of schizophrenia with 20 years of follow-up. After 2 years of follow-up, negative and psychotic symptoms, mainly hallucinations, were reduced in the intensive early intervention program (OPUS) group compared with the treatment as usual (TAU) group.15 However, after 5 years of follow-up (3 years after the end of treatment), the effects of the intervention had equalized to the same level in both groups.16 Despite this, individuals from the OPUS group were less likely to live in supported housing and they had fewer days of psychiatric hospitalizations compared with the TAU group.16 After 10 years of follow-up, all the clinical outcomes favoring EIS had faded, but a tendency to spend fewer days in supported housing was observed.17 Still, knowledge is sparse on the long-term effects of EIS among individuals with a first episode of schizophrenia.

In this study, we aimed to investigate the clinical association of EIS compared with TAU 20 years after their first diagnoses of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder. The main outcomes were psychopathological and functional outcomes, mortality, psychiatric hospitalizations, psychiatric outpatient contacts, and use of supported housing and homeless shelters. All other variables were explored as secondary outcomes. Furthermore, rates of remission and recovery are reported.

Methods

Participants

A total of 547 individuals from the catchment areas of Aarhus and Copenhagen, Denmark, were included in the trial between January 1998 and December 2000 with the following inclusion criteria: age 18 to 45 years and a first diagnosis within the schizophrenia spectrum in accordance with the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision18 codes F20-F25 and F28-F29. Individuals were excluded if they had been treated with antipsychotics (>12 weeks of treatment prior to randomization), had substance-induced psychosis, mental disability (IQ lower than 70), or organic mental disorders. The participants were randomized with concealed allocation sequence to either 2 years of EIS (OPUS intervention) or mental health community treatment (standard treatment at that time). At the time of inclusion, the participants represented 90% and 63% of incident cases registered in the catchment areas of Aarhus and Copenhagen, respectively.19 All participants interviewed at 20-year follow-up provided written informed consent, and the assessments were carried out at the participants’ homes or local environment or at the research unit, Copenhagen Research Centre for Mental Health.20 In addition, participants were offered compensation with a gift basket with groceries as well as paid transportation when needed. The OPUS trial has been approved by the Regional Ethical Scientific Committee and by the Danish Data Protection Agency.

Interventions

The OPUS intervention consisted of modified assertive community treatment, social skill training, psychoeducation, and family involvement21 including possibility for participation in psychoeducational multifamily groups.22 The treatment was delivered by a multidisciplinary team with a staff:patient ratio of 1:10. The standard treatment was mostly based on a case manager principle with a staff:patient ratio of 1:20 to 1:30 consisting of the available community mental health treatment.15,16 Individuals in both treatment arms were equally treated with antipsychotic medication at 1-year follow-up in accordance with national guidelines (eTable 1 in Supplement 1). The interventions have been described in detail elsewhere.15,16 Furthermore, 4 clinical assessments (1, 2, 5, and 10 years) of the participants have been carried out through the past 20 years with follow-up rates of 77%,19 67%,23 55%,16 and 63%,17 respectively.

Outcomes

Clinical staff, blinded to the original treatment allocation, assessed the 20-year follow-up with the following clinical assessment battery: reassessments of psychiatric diagnoses were based on the schedule for clinical assessment in neuropsychiatry (SCAN 2.1).24 Psychotic and negative symptoms in the past 3 and 6 months were measured on the Scale for Assessment for Positive Symptoms (SAPS)25 and Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS),26 respectively. Functional level was scored on the Global Assessment of Functioning scale (GAF-F)27 and the Personal and Social Performance scale.28 Cognition was assessed using the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia.29

Further information was collected by self-report on cohabitation and intimate partnership, living conditions and children, educational level, employment and work ability, housing and homelessness, current psychiatric treatment including doses and adherence to antipsychotic treatment, self-perceived recovery, substance misuse, suicidal ideations, and suicide attempts.

Additionally, the following questionnaires were included: quality of life was measured on 4 domains (physical health, psychological, social relationship, and environment) with the World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF,30,31 health-related quality of life was measured on the EuroQoL 5-dimension,32 self-perceived physical health was measured on the Danish Sundhedsprofilen 2013,33 and self-perceived recovery was reported by the participants as either no, partly, or fully self-perceived recovery.

The Danish Registry Data

All 547 participants were identified and followed up with longitudinal sociodemographic data through the Danish registers with a unique identification number linking them to the individual-level data.

The following registers hold complete and updated data in real time on all participants (not deceased or emigrated) on a range of relevant outcomes: (1) addresses and vital status was drawn from the Danish Civil Registration System,34 (2) information about psychiatric service use (days of psychiatric hospitalizations, number of psychiatric outpatient contacts) was extracted from the Danish Psychiatric Central Register,35 (3) use of supported housing and homeless shelters at the previous year up to 20-year follow-up was obtained by linking information from the official Danish national website Tilbudsportalen with addresses of all supported housing facilities and homeless shelters in Denmark with individual-level address information in the Danish Civil Registration System register34 as described in a previous publication,36 (4) mortality and cause of death was drawn from the Cause of Death Registry,37 and (5) vocational status was available from the DREAM database.38 Registry data were collected for all individuals regardless of participation in the assessments and is thus free from attrition.

Statistical Analysis

We performed intention-to-treat analysis on SANS,26 SAPS,25 and GAF-F,27 still censoring those who had died. We used a linear mixed model with repeated data from the 1-, 2-, 5-, 10-, and 20- year follow-up and adjusted for treatment center and symptom dimension at baseline. Furthermore, we included 2-way interaction terms between time and intervention, which indicated whether duration of time of a given outcome differed between the OPUS and TAU groups.

We calculated a composite score for SAPS called the psychotic symptom dimension = hallucinations score + delusions score / 2, including global score for hallucinations and delusions domains from SAPS.39 The negative symptom dimension was based on global scores for 4 domains in SANS including affective flattening or blunting, alogia, avolition/apathy, and anhedonia/asociality.39 The disorganized symptom dimension was based on 2 SAPS domains, bizarre behavior and formal thought disorder, and 1 SANS domain, inappropriate affect.39

Register Data With Full Longitudinal Data on All Participants

Cox regression was used to perform mortality analysis with updated data on causes of mortality from the Danish registers up until 20 years after randomization. Analyses on use of supported housing and homeless shelters as well as total days of psychiatric hospitalizations (after randomization) and number of outpatient contacts (excluding contact to psychiatric emergency departments) were done in accordance with the intention-to-treat principle and negative binomial regression with the natural logarithm of time under observation as offset, censoring participants at death or migration. These analyses were all adjusted for treatment center.

Definition of Symptom Remission and Clinical Recovery

Symptom remission was defined as a score of 2 or less on all items on SAPS and SANS for at least 6 months in accordance with the Remission in Schizophrenia Working Group.40 As previously reported,41 clinical recovery was defined as no psychotic episode, no psychiatric hospitalizations, and no supported accommodation for 2 consecutive years before follow-up and currently studying or working and a GAF-F score of 60 or higher.

All analyses were performed using Stata/MP version 15.1 (StataCorp) and IBM SPSS statistical software versions 25 and 27 (SPSS Inc). Two-sided P values were statistically significant at less than .05. Analysis took place between December 2021 and August 2022.

Results

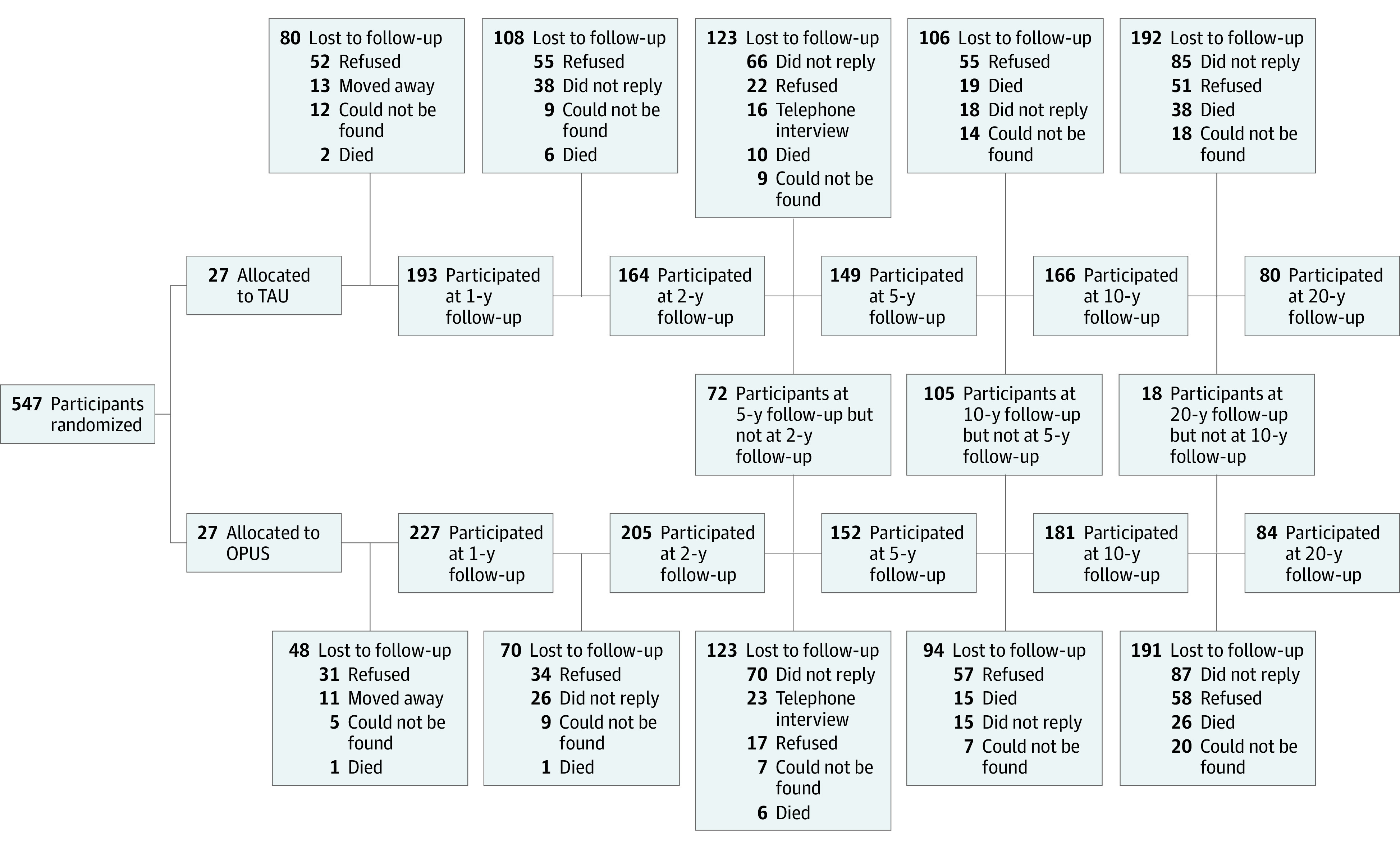

Of 547 participants, 164 (30%) were interviewed at 20-year follow-up (mean [SD] age, 45.9 [5.6] years; range, 38-64 years) (Figure 1). Of the 383 nonparticipants, 64 (17%) died, 109 (28%) refused to participate, 172 (45%) did not respond to the invitation of participation, and 38 (10%) were lost to follow-up due to either emigration or nondisclosure of name and address/address confidentiality or conservatorship. In participant dropout analysis, we found significant differences on baseline variables between participants and nonparticipants at 20-year follow-up. Participants were slightly younger (mean [SD] baseline age, 25.5 [5.6] years vs 27.1 [6.6] years; P = .007), included more female individuals (85 [52%] vs 138 [36%]), more had completed high school (69 [42%] vs 115 [30%]), were engaged in studying or working (54 [33%] vs 92 [24%]), and performed better on global functioning (mean [SD] GAF-F score, 44.2 [13.2] vs 39.9 [13.2]; P < .001) and on global symptom scores (mean [SD] GAF-S score, 35.0 [10.5] vs 32.9 [10.7]; P = .04) compared with nonparticipants at baseline (eTable 1 in Supplement 1). Nonparticipants had higher negative symptom scores (mean [SD] negative symptom dimension, 2.3 [1.2] vs 1.9 [1.1]; P = .003) and disorganized symptom scores (mean [SD] disorganized symptom dimension, 1.1 [1.0] vs 0.9 [0.9]; P = .03) at baseline compared with participants (eTable 1 in Supplement 1). Further dropout analysis on baseline characteristics between participation among the OPUS and TAU groups are shown in eTable 2 in Supplement 1. eTable 3 in Supplement 1 details the same dropout analyses for symptoms and function using the last available assessment point excluding the 20-year assessment.

Figure 1. Flowchart of Participation.

OPUS indicates intensive early intervention program; TAU, treatment as usual.

At 20-year follow-up, we found age to be significantly higher among participants in the OPUS group compared with the TAU group (mean [SD] age, 46.8 [5.6] years vs 45.0 [5.2] years; P = .04) (Table 1).

Table 1. Clinical Characteristics of Participants at 20-Year Follow-up.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 164) | TAU (n = 80) | OPUS (n = 84) | ||

| Sociodemographics | ||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 45.93 (5.47) | 45.03 (5.2) | 46.78 (5.6) | .04 |

| Female | 85 (51.8) | 38 (47.5) | 47 (56.0) | .28 |

| Male | 79 (48.2) | 42 (52.5) | 37 (44.0) | |

| Independent living | 154 (93.9) | 76 (95.0) | 78 (92.9) | .33 |

| In a relationship | 70 (42.7) | 34 (42.5) | 36 (42.9) | .96 |

| Being a parent | 71 (43.3) | 35 (43.8) | 36 (42.9) | .91 |

| Living in supported housing | 9 (5.5) | 4 (5.0) | 5 (6.0) | .79 |

| Homelessness | 1 (0.6) | 0 | 1 (1.2) | .33 |

| Employed | 48 (30.6) | 27 (35.1) | 21 (26.3) | .23 |

| Receiving social benefits | 109 (69.4) | 50 (64.9) | 59 (73.8) | .23 |

| Educational level | ||||

| Primary school | 40 (24.4) | 17 (21.3) | 23 (27.4) | .69 |

| High school | 20 (12.2) | 14 (17.5) | 6 (7.1) | |

| Vocational education | 33 (20.1) | 15 (18.8) | 18 (21.4) | |

| Short education (1-2 y) | 8 (4.9) | 4 (5.0) | 4 (4.8) | |

| Medium-long education (3-4.5 y) | 32 (19.5) | 16 (20.0) | 16 (19.0) | |

| Long education (5-6 y) | 26 (15.9) | 12 (15.0) | 14 (16.7) | |

| Diagnoses (ICD-10) | ||||

| Alcohol/substance use disorder | 24 (14.9) | 14 (17.9) | 10 (12.0) | .30 |

| Social and global functioning, mean (SD) | ||||

| GAF-F score27 | 57.87 (15.65) | 59.24 (15.81) | 56.54 (15.47) | .27 |

| Personal and Social Performance scale score28 | 57.61 (15.78) | 59.10 (16.10) | 56.17 (15.43) | .24 |

| Psychopathology, mean (SD) | ||||

| Psychotic dimension (excluding F21) | 1.12 (1.46) | 1.01 (1.39) | 1.22 (1.54) | .83 |

| Negative dimension | 1.54 (1.15) | 1.45 (1.11) | 1.63 (1.20) | .32 |

| Disorganized dimension | 0.65 (0.89) | 0.67 (0.92) | 0.62 (0.86) | .73 |

| Cognition, mean (SD) | ||||

| Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia, total z score29 | 0.01 (1.021) | 0.07 (1.023) | −0.05 (1.024) | .50 |

| Current use of antipsychotic medication | ||||

| Users of antipsychotics | 80 (48.8) | 38 (47.5) | 42 (50.0) | .75 |

| Suicidal ideation in the past 2 y | ||||

| Suicidal thoughts | 40 (24.7) | 14 (17.9) | 26 (31.0) | .06 |

| Suicide attempts | 2 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.4) | .17 |

| Remission/recovery | ||||

| Symptom remission (excluding F21)a | 53 (39.8) | 29 (42.0) | 24 (37.5) | .59 |

| Clinical recovery (excluding F21)b | 23 (17.2) | 14 (21.2) | 9 (14.1) | .29 |

| Self-perceived recovery | ||||

| None | 41 (25.3) | 16 (20.3) | 25 (30.1) | .21 |

| Partly | 65 (40.1) | 31 (39.2) | 34 (41.0) | |

| Fully | 56 (34.6) | 32 (40.5) | 24 (28.9) | |

| World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF30,31 | ||||

| Very poor | 2 (1.3) | 0 | 2 (2.5) | .61 |

| Poor | 14 (9.1) | 7 (9.3) | 7 (8.9) | |

| Fair | 34 (22.1) | 15 (20.0) | 19 (24.1) | |

| Good | 74 (48.1) | 39 (52.0) | 35 (44.3) | |

| Excellent | 30 (19.5) | 14 (18.7) | 16 (20.3) | |

| Self-rated physical healthc | ||||

| Very poor | 8 (5.2) | 1 (1.3) | 7 (8.9) | .22 |

| Poor | 29 (18.7) | 15 (19.7) | 14 (17.7) | |

| Fair | 31 (20.0) | 16 (21.1) | 15 (19.0) | |

| Good | 73 (47.1) | 35 (46.1) | 38 (48.1) | |

| Excellent | 14 (9.0) | 9 (11.8) | 5 (6.3) | |

| Health-related quality of life, mean (SD)d | 72.21 (19.48) | 71.59 (18.66) | 70.93 (20.26) | .40 |

Abbreviations: GAF-F, Global Assessment of Functioning scale; ICD-10, International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision; OPUS, intensive early intervention program; TAU, treatment as usual.

Symptom remission: symptom remission was defined as a score of 2 or less on all items on Scale for Assessment for Positive Symptoms and Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms for at least 6 months in accordance with the Remission in Schizophrenia Working Group.40

Clinical recovery: defined as no psychotic episode, no psychiatric hospitalizations, and no supported accommodation for 2 consecutive years before follow-up and currently studying or working and a GAF-F score of ≥60.

Using the Danish Sundhedsprofilen 2013.33

EuroQoL 5-dimension,32 self-rated health related quality of life, scale from 0-100.

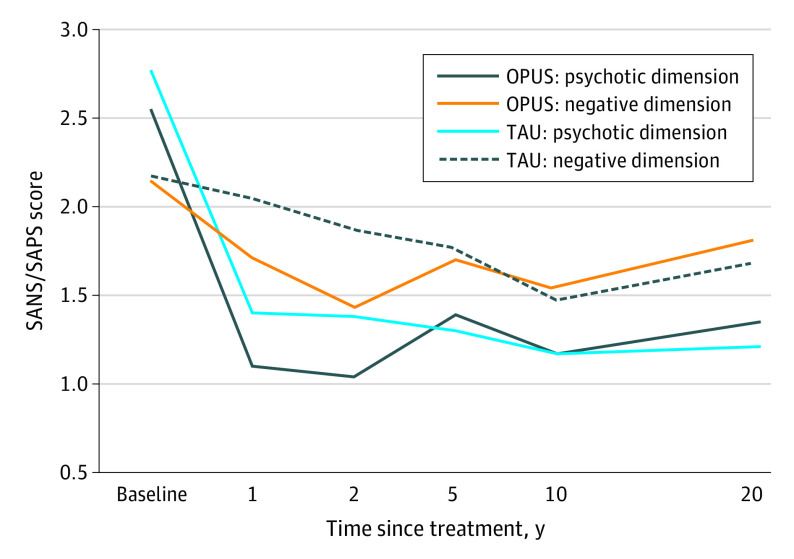

With the TAU group as a reference group, we found no significant differences between the OPUS and TAU groups in regard to psychotic (estimated mean difference, 0.14 [95% CI, −0.25 to 0.52]; P = .48) and negative symptoms (estimated mean difference, 0.13 [95% CI, −0.18 to 0.44]; P = .35) (Table 2 and Figure 2). Furthermore, no significant differences were found between the groups on global functional levels (estimated mean difference, −3.72 [95% CI, −7.67 to 0.22]; P = .06) (Table 2). (A graphic illustration of the development of global functional levels in both groups is given in eFigure 1 in Supplement 1).

Table 2. Psychotic and Negative Symptoms and Global Functional Levels at 1, 2, 5, 10, and 20 Years After Randomization.

| Follow-up | Mean (SE) | Estimated mean difference (95% CI) | P value of difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPUS | TAU | |||

| Psychotic symptom dimensiona | ||||

| 1 y | 1.10 (0.08) | 1.40 (0.09) | −0.30 (−0.54 to −0.06) | .02 |

| 2y | 1.04 (0.09) | 1.38 (0.10) | −0.34 (−0.60 to −0.08) | .01 |

| 5 y | 1.39 (0.12) | 1.30 (0.12) | 0.09 (−0.24 to 0.43) | .58 |

| 10 y | 1.17 (0.10) | 1.17 (0.11) | 0.00 (−0.29 to 0.29) | .99 |

| 20 y | 1.35 (0.14) | 1.21 (0.14) | 0.14 (−0.25 to 0.52) | .48 |

| Negative symptom dimensionb | ||||

| 1 y | 1.71 (0.07) | 2.06 (0.07) | −0.35 (−0.53 to −0.16) | .001 |

| 2 y | 1.42 (0.08) | 1.87 (0.08) | −0.45 (−0.67 to −0.23) | .001 |

| 5 y | 1.70 (0.10) | 1.76 (0.10) | −0.06 (−0.34 to 0.23) | .69 |

| 10 y | 1.55 (0.08) | 1.47 (0.08) | 0.08 (−0.14 to 0.29) | .49 |

| 20 y | 1.82 (0.11) | 1.69 (0.11) | 0.13 (−0.18 to 0.44) | .41 |

| GAF functionc | ||||

| 1 y | 51.74 (0.89) | 49.42 (0.93) | 2.32 (−0.21 to 4.85) | .07 |

| 2y | 54.89 (0.98) | 52.23 (1.04) | 2.66 (−0.13 to 5.45) | .06 |

| 5 y | 53.34 (1.24) | 53.28 (1.26) | 0.05 (−3.41 to 3.52) | .98 |

| 10 y | 53.24 (1.15) | 53.97 (1.19) | −0.73 (−3.99 to 2.52) | .66 |

| 20 y | 51.97 (1.40) | 55.69 (1.43) | −3.72 (−7.67 to 0.22) | .06 |

Figure 2. Psychotic and Negative Symptom Dimensions Between the Intensive Early Intervention Program (OPUS) and Treatment as Usual (TAU) Groups Since Start of Treatment.

SANS indicates Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms; SAPS, Scale for Assessment for Positive Symptoms.

The time × intervention interaction terms from the mixed-model analysis were not statistically significant for the psychotic symptoms dimension (F4,283.695 = 2.195; P = .07) but were significant for the negative symptom dimension (F4,267.896 = 5.037; P <=.001) as well as GAF-F scores (F4,303.476 = 2.501; P = .04).

For the analysis of symptom remission and clinical recovery rates, we excluded those diagnosed with schizotypal disorders at baseline (42 of 79 [53.2%] in the OPUS group and 37 of 79 [46.8%] in the TAU group; eTable 1 in Supplement 1), as a diagnosis of schizotypal disorder excludes any major psychotic symptoms. A total of 53 participants (40%) obtained symptom remission, and 23 (18%) were in clinical recovery at 20-year follow-up. Remission accounted for 37.5% (n = 24) in the OPUS group and 42% (n = 29) in the TAU group (Table 1). Clinical recovery accounted for 14.1% (n = 9) in the OPUS group and 21.2% (n = 14) in the TAU group (Table 1). Furthermore, 57 participants (28.8%) (observed cases) experienced clinical recovery at least once through the past 20 years (eFigure 2 in Supplement 1 includes a graphic illustration of clinical recovery).

Register-Based Outcomes

For the total sample of 547 participants, register-based outcomes were analyzed and therefore differ from the numbers in Figure 1 and Table 1.

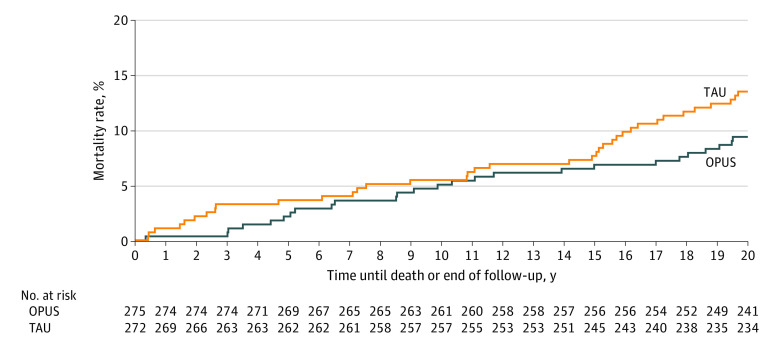

All-cause mortality at 20-year follow-up was 14.1% (n = 77) with 13.1% (n = 36) in the OPUS group and 15.1% (n = 41) in the TAU group (Figure 3). Overall, 19 (3.5%) died by suicide (8 [2.9%] in the OPUS group and 11 [4.0%] in the TAU group).

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier Mortality Curve for Intensive Early Intervention Program (OPUS) vs Treatment as Usual (TAU).

Using the registers with full longitudinal data on all participants, we found no difference in the rate of psychiatric hospitalizations per year among the OPUS group compared with the TAU group 10 to 20 years after randomization (incidence rate ratio, 1.20 [95% CI, 0.73-2.00]; P = .46) (eTable 4 in Supplement 1). Furthermore, no difference was detected in number of outpatient contacts (incidence rate ratio, 1.20 [95% CI, 0.89-1.61]; P = .24) (eTable 4 and eFigure 3 in Supplement 1). Also, 7 individuals (2.9%) in the OPUS group and 5 (2.3%) in the TAU group had spent 1 or more days in supported housing or homeless shelters at the previous year up to 20-year follow-up. Approximately, 52 (24.6%) in the OPUS group and 54 (27.6%) in the TAU group were in full- or part-time employment (with/without supported employment benefits) 50% of the past year prior to the 20-year follow-up.

Discussion

In this long-term follow-up study among individuals with first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorder, we found no evidence that 2 years of EIS were associated with long-term illness course compared with TAU.

No differences were found between the groups on educational level, living conditions, cognition, use of antipsychotics, self-rated physical and mental health, quality of life, symptom remission, or clinical recovery at 20-year of follow-up. A statistically significant time interaction for negative symptom dimension as well as global functioning scores was found. This is seen in all previous studies among the same group of individuals and driven by differences found at 2-year follow-up.23 Using the registers with complete longitudinal data on all participants, we found no significant differences between the groups regarding mortality rates, number of outpatient contacts, or days of psychiatric hospitalizations 10 to 20 years after inclusion. Use of supported housing and homeless shelters were also not found to be different between the groups at 20-year follow-up. Looking back at earlier follow-up points, we found no significant differences between the treatment groups regarding symptom levels or global level of function sustained after 5 years. The previous studies showed that at 2-year follow-up, OPUS treatment was superior to TAU regarding symptom levels, comorbid substance use, adherence to treatment, and satisfaction with treatment,23 but these differences were no longer significant at 5-year follow-up.16 At 5 years, an effect on use of supported housing and psychiatric hospitalization was observed favoring OPUS treatment above TAU,16 but at the 10-year follow-up, no significant differences between the groups were found,17 so it is not surprising that no new differences were found at 20-year follow-up. The lack of sustained treatment effects contradicts the critical period hypothesis, as it could suggest that treatment-induced progress in the first years of diagnosis does not change the long-term trajectory. However, it is worth mentioning that in the last 10 years, the OPUS intervention was implemented nationwide in Denmark as standard treatment for all incident cases of schizophrenia,42 and flexible community treatment was set up to manage treatment of patients with ongoing illness.

The implementation of the OPUS intervention has been proven even more effective in clinical settings43 on several outcomes (ie, reduced all-cause mortality, lower risk of alcohol and substance misuse, psychiatric hospitalizations and admissions, daily doses of antipsychotics, and improved odds of working/studying).43 Despite the higher staff:patient ratio in the real-world setting, fidelity assessment of the OPUS intervention found good fidelity scores among the majority of OPUS teams postimplementation.42 The OPUS intervention has also proven to be more effective and less expensive than TAU.44 This supports that EIS is as effective in a real-world setting as in short-term studies.12

The mortality rate in our population was 14.1% compared with 3.8% for same-aged individuals in the background population during this period. This is an alarming finding that calls for improved prevention and treatment of physical comorbidities and suicidal behavior among individuals with schizophrenia.

Specialized EIS have been implemented all around the world and are proven effective in treatment of patients with first-episode psychosis.12 We found a 40% symptom remission and an 18% clinical recovery rate among observed individuals at 20-year follow-up, and while this gives rise to optimism and hope among individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia, it also means many patients need further help. It is time to develop specialized treatment units targeting patients with multiple episode and chronic trajectories similar to the development of EIS. To further improve long-term outcomes among individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia, some specialized interventions could be very effective for patients in all stages of illness. A recent network meta-analysis on prevention of relapses points to family interventions, family psychoeducation, and cognitive behavioral therapy as 3 primary psychosocial treatments to reduce relapses.45 Going forward, we should consider these 3 types of intervention worldwide when implementing or extending EIS for individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia. Yet, there is still a lack of long-term RCT studies investigating EIS with no other RCT reporting on outcomes more than 5 years after inclusion.46,47,48

Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge, the present study is the longest RCT follow-up among individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorder. The main strength of this study is the 20-year clinical and longitudinal data assessed among a large sample of individuals diagnosed with a first episode of schizophrenia spectrum disorders. A limiting factor was the markedly increased attrition rate from the 10-year to the 20-year follow-up. Only about half of the participants in the 20-year follow-up received treatment with antipsychotic medication. This suggests that perhaps patients with more severe symptoms were underrepresented in this follow-up. Conducting long-term outcome studies is challenging among individuals with severe mental disorders, since those with most unfavorable outcomes are hard to reach possibly due to relapses, lack of contact to mental health services, or homelessness. In addition to this, the COVID-19 pandemic might also have influenced our follow-up rate. While the periods of lockdown delayed our study about 6 months, we continued to conduct assessments during the pandemic between lockdowns. It is very likely that more participants declined participation during this time because of the risk of infection, especially because this population was at higher risk of severe complications.36 With such high rates of missing data, we did not deem it feasible to impute missing data.49 To account for the high attrition rate, we used the Danish registers in some of the analyses in attempt to elucidate the skewed attrition at 20-year follow-up. When conducting dropout analysis, participation was associated with better baseline scores than nonparticipation; therefore, it is likely that the patients with the most severe symptoms and poor outcomes are underrepresented in our study. Therefore, our results should be viewed with this in mind. Finally, it is currently not certain how well our results would translate to other types of EIS than those very similar to OPUS.

Conclusions

In this 20-year follow-up study of a randomized clinical trial, we did not find any long-term differences among individuals receiving 2 years of EIS compared with TAU. New initiatives are needed to maintain the positive outcomes achieved after EIS and further improve long-term outcomes among individuals diagnosed with first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorder. A Danish RCT did not find 5 years of OPUS to be superior to the usual 2 years of OPUS followed by transfer to other treatment.46 While registry data was without attrition, interpretation of clinical assessments is limited by high attrition rate. However, this attrition bias most likely confirms the lack of an observed long-term effect of OPUS.

eTable 1. Baseline characteristics among participants and non-participants at 20-year follow-up

eTable 2. Baseline characteristics among participants and non-participants at 20-year follow-up divided between the OPUS-group and TAU-group

eTable 3. Last observation characteristics (excluding the 20-year assessment) among participants and non-participants at 20-year follow-up divided between the OPUS-group and TAU-group

eTable 4. Psychiatric Hospitalizations and Outpatient Contacts at one-two, two-five, five-ten and ten-20 Years after Randomization into Early Intervention Services (OPUS-treatment) vs. TAU

eFigure 1. Global functional levels between the OPUS-group and the TAU-group since start of treatment

eFigure 2. Percentages of Participants in Clinical Recovery at Five-, Ten- and 20-years of Follow-up

eFigure 3. Psychiatric hospitalizations and outpatient contacts between the OPUS-group and the TAU-group since start of treatment

Data sharing statement

References

- 1.GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators . Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1789-1858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laursen TM, Plana-Ripoll O, Andersen PK, et al. Cause-specific life years lost among persons diagnosed with schizophrenia: is it getting better or worse? Schizophr Res. 2019;206:284-290. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2018.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pedersen CB, Mors O, Bertelsen A, et al. A comprehensive nationwide study of the incidence rate and lifetime risk for treated mental disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(5):573-581. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peritogiannis V, Gogou A, Samakouri M. Very long-term outcome of psychotic disorders. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020;66(7):633-641. doi: 10.1177/0020764020922276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huxley P, Krayer A, Poole R, Prendergast L, Aryal S, Warner R. Schizophrenia outcomes in the 21st century: a systematic review. Brain Behav. 2021;11(6):e02172. doi: 10.1002/brb3.2172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jääskeläinen E, Juola P, Hirvonen N, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of recovery in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(6):1296-1306. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lally J, Ajnakina O, Stubbs B, et al. Remission and recovery from first-episode psychosis in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of long-term outcome studies. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;211(6):350-358. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.117.201475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hansen HG, Speyer H, Starzer M, et al. Clinical recovery among individuals with a first-episode schizophrenia an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2022;sbac103. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbac103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morgan C, Lappin J, Heslin M, et al. Reappraising the long-term course and outcome of psychotic disorders: the AESOP-10 study. Psychol Med. 2014;44(13):2713-2726. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714000282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henry LP, Amminger GP, Harris MG, et al. The EPPIC follow-up study of first-episode psychosis: longer-term clinical and functional outcome 7 years after index admission. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(6):716-728. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04846yel [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kotov R, Fochtmann L, Li K, et al. Declining clinical course of psychotic disorders over the two decades following first hospitalization: evidence from the Suffolk County Mental Health Project. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(11):1064-1074. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.16101191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Correll CU, Galling B, Pawar A, et al. Comparison of early intervention services vs treatment as usual for early-phase psychosis: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(6):555-565. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.0623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Birchwood M, Todd P, Jackson C. Early intervention in psychosis: the critical period hypothesis. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1998;172(33)(suppl 1):53-59. doi: 10.1192/S0007125000297663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malla AK, Norman RMG, Joober R. First-episode psychosis, early intervention, and outcome: what have we learned? Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(14):881-891. doi: 10.1177/070674370505001402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thorup A, Petersen L, Jeppesen P, et al. Integrated treatment ameliorates negative symptoms in first episode psychosis: results from the Danish OPUS trial. Schizophr Res. 2005;79(1):95-105. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bertelsen M, Jeppesen P, Petersen L, et al. Five-year follow-up of a randomized multicenter trial of intensive early intervention vs standard treatment for patients with a first episode of psychotic illness: the OPUS trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(7):762-771. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.7.762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Secher RG, Hjorthøj CR, Austin SF, et al. Ten-year follow-up of the OPUS specialized early intervention trial for patients with a first episode of psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(3):617-626. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbu155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization . International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10). World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petersen L, Nordentoft M, Jeppesen P, et al. Improving 1-year outcome in first-episode psychosis: OPUS trial. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2005;48:s98-s103. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.48.s98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Velkommen til CORE (Copenhagen Research Centre for Mental Health)-forskningsenheden ved Psykiatrisk Center København. Accessed January 17, 2023. https://www.psykiatri-regionh.dk/core/Sider/default.aspx

- 21.Jørgensen P, Nordentoft M, Abel MB, Gouliaev G, Jeppesen P, Kassow P. Early detection and assertive community treatment of young psychotics: the Opus Study rationale and design of the trial. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2000;35(7):283-287. doi: 10.1007/s001270050240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McFarlane WR, Lukens E, Link B, et al. Multiple-family groups and psychoeducation in the treatment of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52(8):679-687. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950200069016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petersen L, Jeppesen P, Thorup A, et al. A randomised multicentre trial of integrated versus standard treatment for patients with a first episode of psychotic illness. BMJ. 2005;331(7517):602. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38565.415000.E01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wing JK, Sartorius N, Üstun TB. WHO Diagnosis and Clinical Measurement in Psychiatry. A Reference Manual for SCAN. Cambridge University Press; 1998. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511666445 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andreasen NC, Flaum M, Sqayze VW 2nd, Tyrrell G, Arndt S. Positive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia: a critical reappraisal. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47(7):615-621. doi: 10.1097/00001504-199302000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andreasen NC. The Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS): conceptual and theoretical foundations. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1989;(7):49-58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aas IH. Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF): properties and frontier of current knowledge. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2010;9(1):20. doi: 10.1186/1744-859X-9-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tegeler D, Juckel G. Validation of Personal and Social Performance Scale (PSP) on a random test of acute schizophrenic patients. Der Nervenarzt. 2007;78:74.16133433 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keefe RSE, Goldberg TE, Harvey PD, Gold JM, Poe MP, Coughenour L. The Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia: reliability, sensitivity, and comparison with a standard neurocognitive battery. Schizophr Res. 2004;68(2-3):283-297. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2003.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Health Organization Quality of Life–BREF. APA PsycNet. Accessed January 17, 2023. doi: 10.1037/t01408-000 [DOI]

- 31.von Knorring L. Danish validation of WHO Quality of Life Questionnaire. Nord J Psychiatry. 2001;55(4):227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brooks R. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy. 1996;37(1):53-72. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(96)00822-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Danskernes Sundhed-Den Nationale Sundhedsprofil 2013. Sundhedsstyrelsen. Accessed January 17, 2023. https://www.sst.dk/da/udgivelser/2014/danskernes-sundhed---den-nationale-sundhedsprofil-2013

- 34.Pedersen CB. The Danish Civil Registration System. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):22-25. doi: 10.1177/1403494810387965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mors O, Perto GP, Mortensen PB. The Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):54-57. doi: 10.1177/1403494810395825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nilsson SF, Laursen M, Osler M, et al. Adverse SARS-CoV-2-associated outcomes among people experiencing social marginalisation and psychiatric vulnerability: a population-based cohort study among 4,4 million people. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2022;20:100421. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Helweg-Larsen K. The Danish Register of Causes of Death. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):26-29. doi: 10.1177/1403494811399958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.The DREAM database. Statistics Denmark . Accessed January 17, 2023. https://www.dst.dk/en

- 39.Arndt S, Andreasen NC, Flaum M, Miller D, Nopoulos P. A longitudinal study of symptom dimensions in schizophrenia: prediction and patterns of change. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52(5):352-360. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950170026004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Andreasen NC, Carpenter WT Jr, Kane JM, Lasser RA, Marder SR, Weinberger DR. Remission in schizophrenia: proposed criteria and rationale for consensus. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(3):441-449. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Albert N, Bertelsen M, Thorup A, et al. Predictors of recovery from psychosis: analyses of clinical and social factors associated with recovery among patients with first-episode psychosis after 5 years. Schizophr Res. 2011;125(2-3):257-266. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nordentoft M, Melau M, Iversen T, et al. From research to practice: how OPUS treatment was accepted and implemented throughout Denmark. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2015;9(2):156-162. doi: 10.1111/eip.12108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Posselt CM, Albert N, Nordentoft M, Hjorthøj C. The Danish OPUS early intervention services for first-episode psychosis: a phase 4 prospective cohort study with comparison of randomized trial and real-world data. Am J Psychiatry. 2021;178(10):941-951. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2021.20111596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hastrup LH, Kronborg C, Bertelsen M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of early intervention in first-episode psychosis: economic evaluation of a randomised controlled trial (the OPUS study). Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202(1):35-41. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.112300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bighelli I, Rodolico A, García-Mieres H, et al. Psychosocial and psychological interventions for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(11):969-980. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00243-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Albert N, Melau M, Jensen H, et al. Five years of specialised early intervention versus two years of specialised early intervention followed by three years of standard treatment for patients with a first episode psychosis: randomised, superiority, parallel group trial in Denmark (OPUS II). BMJ. 2017;356:i6681. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i6681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kane JM, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. Comprehensive versus usual community care for first-episode psychosis: 2-year outcomes from the NIMH RAISE early treatment program. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(4):362-372. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15050632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ruggeri M, Bonetto C, Lasalvia A, et al. ; GET UP Group . Feasibility and effectiveness of a multi-element psychosocial intervention for first-episode psychosis: Results from the cluster-randomized controlled GET UP PIANO trial in a catchment area of 10 million inhabitants. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(5):1192-1203. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbv058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jakobsen JC, Gluud C, Wetterslev J, Winkel P. When and how should multiple imputation be used for handling missing data in randomised clinical trials: a practical guide with flowcharts. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17(1):1-10. doi: 10.1186/s12874-017-0442-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Baseline characteristics among participants and non-participants at 20-year follow-up

eTable 2. Baseline characteristics among participants and non-participants at 20-year follow-up divided between the OPUS-group and TAU-group

eTable 3. Last observation characteristics (excluding the 20-year assessment) among participants and non-participants at 20-year follow-up divided between the OPUS-group and TAU-group

eTable 4. Psychiatric Hospitalizations and Outpatient Contacts at one-two, two-five, five-ten and ten-20 Years after Randomization into Early Intervention Services (OPUS-treatment) vs. TAU

eFigure 1. Global functional levels between the OPUS-group and the TAU-group since start of treatment

eFigure 2. Percentages of Participants in Clinical Recovery at Five-, Ten- and 20-years of Follow-up

eFigure 3. Psychiatric hospitalizations and outpatient contacts between the OPUS-group and the TAU-group since start of treatment

Data sharing statement