Abstract

Metallophilic interactions were observed in four pairs of 12-membered metallamacrocyclic silver and gold complexes of imidazole-derived N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs), [1-(R1)-3-N-(2,6-di-(R2)-phenylacetamido)-imidazol-2-ylidene]2M2 [R1 = p-MeC6H4, R2 = Me, M = Ag (1b) and Au (1c); R1 = Me, R2 = i-Pr, M = Ag (2b) and Au (2c); R1 = Et, R2 = i-Pr, M = Ag (3b) and Au (3c)], and a 1,2,4-triazole-derived N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC), [1-(i-Pr)-4-N-(2,6-di-(i-Pr)-phenylacetamido)-1,2,4-triazol-2-ylidene]2M2 [M = Ag (4b) and Au (4c)]. The X-ray diffraction, photoluminescence, and computational studies indicate the presence of metallophilic interactions in these complexes, which are significantly influenced by the sterics and the electronics of the N-amido substituents of the NHC ligands. The argentophilic interaction in the silver 1b–4b complexes was stronger than the aurophilic interaction in the gold 1c–4c complexes, with the metallophilic interaction decreasing in the order 4b > 1b > 1c > 4c > 3b > 3c > 2b > 2c. The 1b–4b complexes were synthesized from the corresponding amido-functionalized imidazolium chloride 1a–3a and the 1,2,4-triazolium chloride 4a salts upon treatment with Ag2O. The reaction of 1b–4b complexes with (Me2S)AuCl gave the gold 1c–4c complexes.

Introduction

The closed-shell···closed-shell metallophilic interactions,1,2 commonly seen in coinage metals like Au, Ag, and Cu, are of interest in recent times mainly for their high-end material applications,3 in crystal engineering,4 supramolecular chemistry,5 etc.6,7 Apart from being the focus of mere intellectual curiosity, owing to strange aggregations due to bonding interactions between the coinage metal cations with closed-shell d10 configurations, these metallophilic interactions also arise interest for their photoluminescence,8 electrical conductivity,9,10 and other unexpected properties.7 The aurophilic interaction, being the most common, has been most extensively studied,11,12 followed by the argentophilic and cuprophilic interactions.13 These metallophilicities are weak interactions akin to hydrogen bonding, π–π stacking, ion–ion, ion–dipole, and dipole–dipole interactions. They can have similar profound implications in supramolecular and material applications if exploited judiciously.

The metallophilic interactions, are recognized primarily from the observed short metal···metal contacts, which can also be an artifact of ligand and lattice constraints. Hence, an accurate assessment of the interaction comes from their photoluminescence properties, aided by computational insights. The presence of weak metallophilic interactions is invoked for a long range of metal···metal separations of up to ca. 4 Å,2,14 particularly due to the lack of clarity on the true values of the van der Waals radius of the coinage metals like silver and gold.15 For example, the van der Waals radius of silver varies from that of the Bondi’s estimate of 1.72 Å16 to that of 2.1 Å by Batsanov17 or from that of the Bondi’s16 van der Waals radius of 1.66 Å for gold to that of 2.1 Å by Batsanov.17 The metallophilic interactions are ubiquitous in silver and gold complexes containing bridging18 and nonbridging ligands.19,20

Since the appearance of the first systematic investigations of the Au(I)···Au(I) interactions 4 decades ago,21−23 the concept of metallophilicity has been the subject of intense discussions with the understanding of its true nature continuing to evolve.2,7,24−27 The crucial involvement of metal···metal dispersion interactions in rendering stability to these metallophilic aggregates was shown by the breakdown of the interaction energy, with a minimal influence of the ligands on the overall interaction profile.28 Magnko calculated the {(PH3)AuCl}2 dimer’s potential well depth to be −34.82 kJ/mol at an Au···Au distance of 3.025 Å in line with Pyykkö’s earlier estimation.29 The orbital pairs belonging to the gold d-shell were the principal contributors to the correlation energy. Further, it was demonstrated that, in the case of the Cu(I) and Ag(I) complexes, the correlation contributions involving the ligand orbitals solely could play a significantly more prominent role.30 In this series of the dimeric {(PH3)MCl}2 (M = Cu, Ag, Au) examples, the strength of the metallophilic interaction was estimated to increase from Cu (−22.09 kJ/mol) to Ag (−30.70 kJ/mol) and to Au (−34.82 kJ/mol).30 However, using CCSD(T) calculations, Kaltsoyannis showed that the strength of the metallophilic interaction maximized at Ag and weakened further down group 11.31 In this context, our objective was to shed further light on the observed pattern by adding new synthesized examples, containing discrete singular metallophilic interactions, to the ongoing discussion about understanding the true nature of the d10–d10 interactions.

A primary challenge for studying these interactions arises from their unrestricted extended aggregated nature, which seriously restricts designing systems with discrete singular interactions for a comprehensive study of the metallophilic interaction.10,22 These interactions are ubiquitous and can be mainly manipulated with supported and unsupported ligand systems in designing supramolecular assemblies.6,10,23 However, the approach to design complexes exhibiting discrete singular metallophilic interactions remains a formidable task with fewer examples prevalent in the literature.19,21,32−34

The weak but persistent metallophilic interaction manifests in aggregated structures extending from complex supramolecular assemblies to polynuclear motifs of all varieties.6 Ligands with different steric, electronic, and coordinating requirements stabilize these interactions in various aggregated motifs. The intermolecular metallophilic interactions are more common and observed for many bridging and nonbridging ligands. The intramolecular version is, however, comparatively fewer in number and poses a more significant challenge in their design and synthesis, primarily for reasons of containing the metallophilic interaction within the molecule and from preventing it to extend beyond in intermolecular fashion.

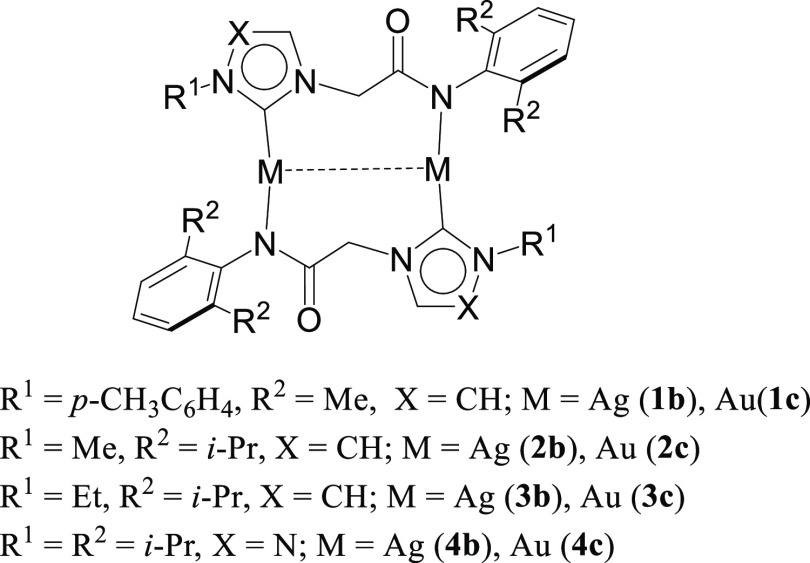

With our interest in understanding the metallophilic interaction, particularly in the ones stabilized over the N-heterocyclic carbenes, we have reported several examples of the metallophilicity bearing supported32,33 and unsupported ligands.19 Here, in this manuscript, we report four pairs of silver 1b–4b and gold 1c–4c N-heterocyclic carbene complexes (Figure 1) derived from imidazole and 1,2,4-triazole rings, bearing discrete singular intramolecular metallophilic interactions. The combined photoluminescence and computational studies provide valuable insights into the nature of the metallophilic interactions in these complexes.

Figure 1.

Twelve-membered metallamacrocyclic silver 1b–4b and gold 1c–4c complexes exhibiting discrete metallophilic interactions.

Results and Discussion

A class of amido-functionalized imidazole 1a–3a and 1,2,4-triazole (4a)-based N-heterocyclic carbene ligand precursors were synthesized from the corresponding 1-R1-imidazole (R1 = 4-MeC6H4, Me, Et) and 1-(i-Pr)-1,2,4-triazole by the direct alkylation with 2-chloro-N-2,6-(R2)2-phenylacetamide (R2 = Me, i-Pr) (Scheme 1). The formations of these imidazole-based 1a–3a and 1,2,4-triazole (4a)-based N-heterocyclic carbene ligand precursors were evident from the appearance of the characteristic highly downfield-shifted NCHN resonance at δ ca. 10.05–10.53 ppm for the imidazole-based 1a–3a ligand precursors and at 11.26 ppm for the 1,2,4-triazole-based 4a ligand precursor in the 1H NMR spectra (Figures S1, S24, S49, and S74). The subsequent reaction of the N-heterocyclic carbene precursors 1a–4a with Ag2O yielded the corresponding large 12-membered silver 1b–4b metallamacrocycles, the formation of which was supported by the observation of the Ag–Ccarbene resonances at δ ca. 177.2–182.3 ppm in the 13C{1H} NMR spectra (Figures S10, S33, S58, and S83).

Scheme 1. Synthetic Route to Amido-Functionalized Ag–NHC 1b–4b and Au–NHC 1c–4c Complexes.

The molecular structures of the 1b–4b complexes, as determined using a single-crystal X-ray diffraction technique, revealed the large 12-membered metallamacrocyclic nature of these complexes (Figures 2, S14, S37, and S62 and Table S1). These structures display Ci symmetry. The Ag–Ccarbene bond lengths of 2.071(2) Å (1b), 2.059(2) Å (2b), 2.0621(17) Å (3b), and 2.054(8) Å (4b) are comparable to the related analogues reported in the literature.32,33 Similarly, the Ag–Namido bond distances were 2.0971(16) Å in 1b, 2.0831(15) Å in 2b, 2.0911(13) Å in 3b, and 2.124(6) Å in 4b, and a near-linear bond angle [∠C(1)–Ag(1)–N(3) (°)] was observed at the metal center [167.90(7) in (1b), 170.01(6) in (2b), 166.36(6) in (3b), and 176.1(3) in (4b)].

Figure 2.

ORTEP of 4b with thermal ellipsoids shown at the 50% probability level. Hydrogen atoms and cocrystallized CH3CN molecules are omitted for clarity. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°): Ag(1)···Ag(2) 2.9974(8), Ag(1)–C(1) 2.054(8), Ag(1)–N(8) 2.125(6), C(1)–N(1) 1.382(10), C(1)–N(3) 1.361(10), C(1)–Ag(1)–N(8) 176.1(3), C(1)–Ag(1)–Ag(2) 100.7(2), N(1)–C(1)–N(3) 100.7(7), N(3)–C(1)–Ag(1) 132.3(6), and N(1)–C(1)–Ag(1) 127.0(6).

Interestingly, all of the 12-membered metallamacrocyclic silver 1b–4b complexes indicated the existence of argentophilic interaction in these complexes as observed from the short Ag···Ag distances of 3.1061(3) Å in (1b), 3.6495(4) Å in (2b), 3.3810(4) Å in (3b), and 2.9974(8) Å in (4b). These Ag···Ag distances are within the range obtained by twice the van der Waals radius of Ag that varied from the estimate of 1.72 Å by Bondi16 to that of 2.1 Å by Batsanov.17

The large 12-membered gold macrometallacyclic analogues 1c–4c were conveniently obtained from the silver 1b–4b complexes by the treatment with (SMe2)AuCl (Scheme 1). In 13C{1H} NMR, the Au–Ccarbene resonances of 1c–4c, appeared at δ ca. 168.9–172.1 ppm, upfield-shifted from the Ag–Ccarbene resonances of δ ca. 177.2–182.3 ppm observed in case of 1b–4b (Figures S10, S17, S33, S40, S58, S65, S83, and S89). Quite significantly, unlike the silver 1b–4b complexes, all of the gold 1c–4c complexes were characterized by the high-resolution mass spectroscopy (HRMS) measurements in which the molecular ion (M+) peak appeared at m/z 1031.2615 for 1c (calculated m/z 1031.2617), m/z 1013.3067 for 2c (calculated m/z 1013.3062), m/z 1019.3553 for 3c (calculated m/z 1019.3556), and m/z 1049.3770 for 4c (calculated m/z 1049.3774) (Figures S20, S43, S68, and S92).

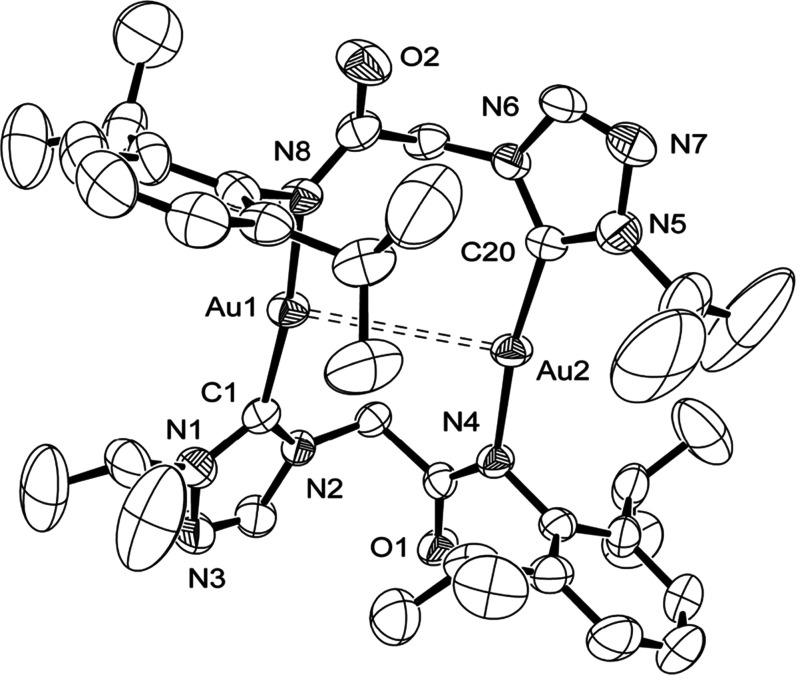

The gold 1c–4c complexes were isostructural with their silver analogues 1b–4b (Figures 3, S22, S45, and S70 and Table S1) as observed from the single-crystal X-ray diffraction studies. The gold structures display Ci symmetry. The Au–Ccarbene bond lengths of 1.993(2) Å (1c), 1.996(3) Å (2c), 1.985(4) Å (3c), and 1.975(4) Å (4c) are shorter than their silver analogues [2.071(2) Å (1b), 2.059(2) Å (2b), 2.0621(17) Å (3b), and 2.054(8) Å (4b)] due to smaller covalent radii of Au (1.37 Å)35 compared to Ag (1.46 Å).35 Quite interestingly, except for the 2c complex, in which a longer Au···Au contact of 4.2597(8) Å was observed, the remaining gold complexes displayed a much shorter metal···metal contact of 3.3462(2) Å (1c), 3.6358(5) Å (3c), and 3.5640(5) Å (4c).

Figure 3.

ORTEP of 4c with thermal ellipsoids shown at the 50% probability level. Hydrogen atoms and cocrystallized H2O molecule were omitted for clarity. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°): Au(1)···Au(2) 3.5640(5), Au(1)–C(1) 1.975(4), Au(1)–N(8) 2.031(3), C(1)–N(1) 1.330(5), C(1)–N(2) 1.361(5), C(1)–Au(1)–N(8) 172.00(14), N(1)–C(1)–N(2) 103.4(3), N(2)–C(1)–Au(1) 130.5(3), and N(1)–C(1)–Au(1) 126.1(3).

The photoluminescence studies indicated that both of the silver 1b–4b and the gold 1c–4c complexes exhibited metallophilic interactions in solution and in the solid state at room temperature. For the silver 1b–4b complexes, the excitation at 242 nm (λ) gave the Ag···Ag emission band at ca. 533–534 nm in CHCl3 solution and at ca. 549–559 in the solid state at room temperature (Table 1 and Figures 4, 5, S23, S46–S48, S71–S73, and S94–S96). The other high-energy band at ca. 430 nm for 1b (Figure 4), 433 nm for 2b (Figure S46), 446 nm for 3b (Figure S71), and 431 nm for 4b (Figure S94) in CHCl3 solution has been assigned to the ligand-based transitions, while in the solid state, the same emission was observed at ca. 389–390 nm for 1b–4b (Figures 5, S23, S47, S48, S72, S73, S95, and S96). Similarly, the presence of aurophilic interactions in 1c–4c was evident from the photoluminescence experiments, which too displayed a low-energy emission band at ca.530–533 nm in CHCl3 (Table 1 and Figures 4, S46, S71, and S94) and at ca. 548–559 nm in the solid state at room temperature (Figures 5, S23, S47, S48, S72, S73, S95, and S96). Like the silver 1b–4b complexes, the ligand-based high-energy band appeared at ca. 433 nm for 1c, 427 nm for 2c, 431 nm for 3c, and 430 nm for 4c in CHCl3 and at ca. 389–390 nm for 1c–4c in the solid state.

Table 1. Absorption and Emission Data for NHC Ligand Precursors 1a–4a, the Silver 1b–4b, and the Gold 1c–4c Complexes.

| room

temperature |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| compounds | λabs, nm (εmax, L3 mol–1 cm–1) | λem, nm in CHCl3 | λem, nm in solid state |

| 1a | 242 (28 504) | 375 | 389 |

| 1b | 239 (34 429) | 430, 534 | 389, 549 |

| 1c | 238 (62 451) | 433, 532 | 390, 548 |

| 2a | 240 (2645) | 425 | 390 |

| 2b | 240 (5683) | 433, 534 | 389, 553 |

| 2c | 250 (92 708) | 427, 533 | 389, 552 |

| 3a | 240 (3676) | 426 | 389 |

| 3b | 240 (7765) | 446, 533 | 390, 559 |

| 3c | 254 (54 145) | 431, 532 | 389, 559 |

| 4a | 240 (3008) | 421 | 390 |

| 4b | 239 (5868) | 431, 534 | 389, 552 |

| 4c | 238 (10 093) | 430, 530 | 389, 552 |

Figure 4.

Comparison of the emission spectra of the ligand (1a), the Ag–NHC complex (1b), and the Au–NHC complex (1c) in CHCl3 at room temperature (excitation at 242 nm), in which the peak representing the M···M interaction is designated by an asterisk (*) in the plot. (#Overtone of excitation at 242 nm).

Figure 5.

Comparison of the emission spectra (expanded) of the ligand (1a), the Ag–NHC complex (1b), and the Au–NHC complex (1c) in the solid state at room temperature (excitation at 242 nm), in which the peak representing the M···M interaction is designated by an asterisk (*) in the plot.

The metal···metal distances in the silver 1b–4b and the gold 1c–4c complexes and their emission bands compared well with other related structurally characterized large 12-membered metallamacrocycles known in the literature (Tables 2 and 3).32,33 It is worth mentioning that all of the structurally characterized examples of such large 12-membered silver and gold metallamacrocycles of amido-functionalized imidazole and 1,2,4-triazole-derived N-heterocyclic carbenes have been reported from our group32,33 with four complexes of the each metals being part of the current study (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2. Comparison of the Crystallographic and Photoluminescence Data of the Large 12-Membered Metallamacrocyclic Ag–NHC Complexes 1b–4b with Those Known in the Literature.

Table 3. Comparison of the Crystallographic and Photoluminescence Data of the Large 12-Membered Metallamacrocyclic Au–NHC Complexes 1c–4c with Those Known in the Literature.

The density functional theory (DFT) studies were undertaken to understand the electronic structures of the silver 1b–4b and the gold 1c–4c complexes. The metallophilic interactions were looked at by performing topological analysis, and the noncovalent interaction calculations were done for the visualization of the interactions between the silver and the gold atoms. The electron localization functions were estimated to understand electron localization between two metal atoms. In this regard, it is worth mentioning that, as the secondary interactions like hydrogen bonding, π–π stacking, and the crystal packing effects are more dominant over a weaker cuprophilic interactions13 than the relatively stronger argentophilic and aurophilic interactions,10,11,27 these secondary interactions are considered to have no significant influence in the metallophilic interactions in the silver 1b–4b and the gold 1c–4c complexes for the computational study.

The absorption spectra of silver 1b–4b and gold 1c–4c complexes in CHCl3 have been computed using the TD-DFT method to comprehend the electronic transition. The experimental and computed findings of λabsmax of different complexes using various functionals with various basis sets are given in Table S2. The B3LYP functional at LANL2DZ/6-31G(d) overestimates vertical excitation energies around 40 nm, while at the def2tzvp level about only 30 nm. The nonempirical PBE0 functional frequently used in benchmarks offers excellent results when compared to other density functionals, at least for the electronic vertical transitions.36 We also tried this exchange–correlation functional, and expectedly, PBE0 results agreed with experimental excitation energies. Table S3 lists the predicted maximum absorption energies (wavelengths) along with their oscillator strengths, primary contributions from different electronic transitions, excited states, and assignments in addition to the available experimental findings. The frontier orbitals involved in these transitions for different complexes are given in Figure S97. Based on our TD-DFT frontier orbitals analysis, all of the complexes’ bands may be described as an admixture of MLCT, LMCT, and ILCT states. We conducted the natural transition orbital (NTO) analysis based on the computed transition density matrices to examine the nature of absorption. Natural transition orbitals offer a more intuitive representation of the orbitals when excited states of molecules with highly delocalized chromophores or many chromophoric sites are involved. In terms of an expansion into single-particle transitions, this technique provides the most condensed depiction of the transition density between the ground and excited states. The terms “particle” and “hole” transition orbitals are used here to designate the vacant and occupied NTOs, respectively. The NTOs for all complexes are given in Figure S98. Based on our TD-DFT NTO analysis, all of the complexes’ bands may be described as an admixture of MLCT, LMCT, and ILCT states. Optically excited transition orbitals move from occupied (hole) to unoccupied (electron) transition orbitals. Hole NTOs are delocalized on N–Ag–Ag–N (N–Au–Au–N), while particle NTOs are mainly delocalized on C–Ag–Ag–C (C–Au–Au–C). By frontier orbitals and NTO, we may conclude that the main contributor for the transition arises from dx2–y2 – dx2–y2 (Ag/Au) – dσ to π* orbitals of the aromatic ring.

The semiempirical, Hartree–Fock, correlated methods like MP2 calculations suggest that the dispersion interaction is the dominant attractive component of metallophilic interactions and becomes more favorable when descending in group 11.24 On the other hand, dispersion-corrected DFT calculations have suggested that dispersion contributions are substantially less important than MP2 computations and that they are also relatively independent of the metal.24 Similarly, QCSID and CCSDT methods also contradict MP2 methods and support stronger argentophilic interactions compared to aurophilic interactions.24 Recent energy decomposition analysis suggests a combination of electrostatic interactions and weakly covalent M···M orbital interactions, both of which are counterbalanced by Pauli repulsion, which dictate the strength of metallophilic interactions.37 Based on this, we performed the atoms in molecules (AIM) analysis and constructed the topological diagrams for the silver 1b–4b and the gold 1c–4c complexes (Table 4 and Figure 6). The AIM analysis indicated the presence of a bond critical point (BCP) between two metal ions in all of the cases barring 2c, suggesting favorable metallophilic interactions. The electron density ρ(r), which measures the strength of this interaction, is found to be 0.019 au (1b), 0.0076 au (2b), 0.011 au (3b), 0.023 au (4b), 0.017 au (1c), 0.010 (3c) au, and 0.012 au (4c) (Table 4). The interaction energy,38Eint = V/2, at the M···M bond critical point is found to be −18.6 (1b), −4.5 (2b), −8.7 (3b), −25.7 (4b), −14.7 (1c), −7.5 (3c), and −8.8 (4c) (Table 4). The electron density ρ(r) and interaction energy Eint values of 1b–4b complexes are higher than those of 1c–4c, which indicates that the argentophilic interactions in the silver 1b–4b complexes are stronger. These values are smaller than the strong metallophilic interactions reported, like 0.042 au in a silver (N,N′-Di-i-propylacetamidinate) complex,39 and suggest that the strength of interactions decreases in the following order: 4b > 1b > 1c > 4c > 3b > 3c > 2b. A small value of the electron density, positive Laplacian value, and negative values of the total electronic energy density H(r) at the BCP generally suggest closed-shell electrostatic interactions.40 Further, the |V(r)|/G(r) ratio for complexes, except for 4b, is close to unity, suggesting closed-shell interactions.40 The order of this ratio is found to be 1b > 1c > 3b > 4c > 3c > 2b > 4b, and the covalency contribution decreases in the same order.

Table 4. Topological Parameters of Different Complexes at the M···M Bond Critical Point.

| parameter | 1b | 2b | 3b | 4b | 1c | 3c | 4c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ρ(r) (au) | 0.0192 | 0.0076 | 0.0118 | 0.0234 | 0.0172 | 0.0104 | 0.0119 |

| G(r) (au) | 0.0129 | 0.0037 | 0.0067 | 0.0172 | 0.0106 | 0.0059 | 0.0069 |

| K(r) (au) | 0.0012 | –0.0003 | –0.0001 | 0.0023 | 0.0005 | –0.0002 | –0.0001 |

| V(r) (au) | –0.0142 | –0.0034 | –0.0066 | –0.0196 | –0.0112 | –0.0057 | –0.0067 |

| H(r) (au) | –0.0012 | 0.0003 | 0.0001 | –0.0023 | –0.0005 | 0.0002 | 0.0001 |

| ∇2ρ(r) (au) | 0.0467 | 0.01621 | 0.0275 | 0.0596 | 0.0407 | 0.0250 | 0.0283 |

| H/ρ | –0.0653 | 0.0417 | 0.0082 | –0.010 | –0.0297 | 0.0255 | 0.0124 |

| |V|/G | 1.100 | 0.9155 | 0.986 | 0.137 | 1.05 | 0.955 | 0.979 |

| Eint = V/2 (kJ/mol) | –18.6 | –4.5 | –8.7 | –25.7 | –14.7 | –7.5 | –8.8 |

Figure 6.

AIM computed topological diagrams for different complexes (a) 1b, (b) 2b, (c) 3b, (d) 4b, (e) 1c, (f) 2c, (g) 3c, and (h) 4c. (Color code: yellow, ring critical point and green, cage critical point).

Apart from AIM, we have also performed NCI analysis that is widely used to understand the nature of noncovalent interactions.41,42 The divergence from a uniform electron distribution is explained by the dimensionless function known as the reduced density gradient (RDG). In regions far from the molecule where the density quickly decays to zero, the RDG will have very large positive values, and in regions with covalent bonds and noncovalent interactions, it will have very low values that are essentially negligible. RDG is a function of electron density and its gradient and is given by eq 1.41

| 1 |

Although low gradient density regions enable the identification of weak interactions in a molecular system, it is unable to differentiate various contributions to the noncovalent interactions, such as attractive and repulsive interactions. For this purpose, the sign of (λ2)ρ (λ2 is the largest eigen value of the Hessian matrix, λ2 < 0 and λ2 > 0 for bonding and nonbonding interactions, respectively) from noncovalent interaction (NCI) analysis can be utilized.41 The noncovalent interaction (NCI) and reduced density gradient (RDG) scatter plots42 for the silver 1b–4b and the gold 1c–4c complexes are shown in Figure 7. In the plots, the blue colored spikes in the negative region of the scatter plot correspond to the hydrogen bonds, the red colored spikes represent the strong repulsive interactions, and the green region indicates the van der Waals interaction. The metallophilic interaction region is circled in the NCI plot, and if we carefully analyze this region across the plot, the following points emerge: (i) for the 1b, 1c, and 4b complexes, this region is dominated by blue color, which suggests a dominant attractive interaction in these complexes and (ii) for the remaining 2b, 3b, 2c, 3c, and 4c complexes, the green color is dominant, and this suggests that the interaction has a dominant van der Waals contribution. Complementary to the NCI plot regions, we can see the corresponding spikes in the scatter plots in the negative region for 1b, 1c, and 4b, which are blue in color, whereas for the 2b, 3b, 2c, 3c, and 4c complexes, the spikes are dominantly green reaffirming our point.

Figure 7.

NCI plots of complexes (a) 1b, (b) 2b, (c) 3b, (d) 4b, (e) 1c, (f) 2c, (g) 3c, and (h) 4c and RDG scatter plots of complexes (a′) 1b, (b′) 2b, (c′) 3b, (d′) 4b, (e′) 1c, (f′) 2c, (g′) 3c, and (h′) 4c.

The NBO analysis performed yields natural population analysis (NPA) on different atoms that offers further insights into metal–metal interactions (Table S4). The charges on silver atoms are more compared to that of gold atoms in all complexes. The charges on pairs of atoms (Ag1, Ag1i) or (Au1, Au1i), (N3, N3i), and (C1, C1i) are almost similar except in the case of 4b and 4c. A significant positive charge on Ag1 or Au1 and a concomitant negative charge on the N3 atom in 2b or 2c leads to a larger Ag···Ag or Au···Au distance. In 4b and 4c, on the other hand, a significant less negative charge on N1 and a no charge on C attached to N1 are found, and this is found to strengthen the Ag···Ag or Au···Au interaction. In the 2b, 3b, and 4b complexes, the groups attached to N1/N1i are methyl, ethyl, and i-propyl, respectively; however, the groups attached to N3/N3i are constant. The steric hindrance capacity normally increases from methyl to i-propyl groups. The negative charge on the carbon atom is found to increase from i-propyl to methyl groups. The charges on N1 and N1i are almost similar. The Wiberg bond index (WBI) (Table 5) is consistent with the metal···metal distance observed in the X-ray structure, with the shortest distance geometry (4b) yielding the largest WBI of 0.17. The WBI is found to be 0.16 (1b), 0.09 (2b), 0.13 (3b), 0.17 (4b), 0.17 (1c), 0.04 (2c), 0.12 (3c), and 0.13 (4c) (Table 5). This again indicates that argentophilic interactions in 2b–4b is stronger than aurophilic interactions in 2c–4c, with 1b and 1c being nearly equal. Further, we observe that the Ag1–N3 and the Ag1–C1 bond’s WBI values are inversely proportional to the Ag···Ag interaction, and the same trend is observed for the WBI values for Au1–N3 and the Au1–C1 bonds in the case of the Au···Au interaction. The stronger argentophilic interactions compared to aurophilic interactions may be attributed to stronger Pauli repulsion between Au···Au centers.25,43 In short, the electronic and the steric factors of the group attached to N1 significanlty influences the M···M interactions.

Table 5. Wiberg Bond Indices of Selected Bonds for Silver 1b–4b and Gold 1c–4c Complexes.

| bonds | 1b | 2b | 3b | 4b | 1c | 2c | 3c | 4c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag1–Ag1i (Au1–Au1i) | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.13 |

| Ag1–N3 (Au1–N3) | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 0.38 | 0.39 |

| Ag1–C1 (Au1–C1) | 0.47 | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.45 | 0.65 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.66 |

Further electron localization function (ELF) analyses were performed to probe the localization of electron density corresponding to the M···M interactions (Figure 8). The electron localization function (ELF) is a simple measure of electron localization in an atomic and molecular system. The ELF is defined by eq 2(44)

| 2 |

where

| 3 |

| 4 |

D(r) is defined as the difference between the kinetic energy density and the bosonic kinetic energy density, D0(r) is taken as a reference (uniform electron gas), and ρ is the electron charge density.

Figure 8.

Electron localization function (ELF) color-filled maps of complexes (a) 1b, (b) 2b, (c) 3b, (d) 4b, (e) 1c, (f) 2c, (g) 3c, and (h) 4c.

The ELF is a relative measurement of the electron localization, and therefore, the ELF values are expected to be in the range of 0 to 1. In general, in the bonding regions, the ELF(r) is expected to reach unity,45 and when ELF(r) is greater than 0.7, electrons are characterized as localized (core or bonding regions or lone pairs). On the other hand, when the value of ELF is less than 0.7, the electron localization is similar to that of an electron–gas, which is typical of metallic bonds.46

Similar to ELF, Schmider and Becke defined another function for finding high localization zones called the localized orbital locator (LOL). The LOL is given by eq 5.47

| 5 |

where

| 6 |

D0(r) is defined similar to ELF. Generally speaking, LOL and ELF are qualitatively comparable, but LOL communicates a more distinct and decisive picture than ELF.48

The ELF values computed at the M···M bond critical point were found to be 0.085 (1b), 0.047 (2b), 0.063 (3b), 0.091 (4b), 0.088 (1c), 0.055 (3c), and 0.062 (4c) (the ELF value for 2c is negligible). Further, the LOL values computed at the M···M bond critical point were found to be 0.234 (1b), 0.183 (2b), 0.206 (3b), 0.241 (4b), 0.236 (1c), 0.194 (3c), and 0.204 (4c). The difference between ELF and LOL values is in the range of 0.12–0.15. The ELF and LOL values are small, indicating only weak metallophilic interactions, and this ELF and LOL order also supports the strengths of the M···M interaction. The ELF and LOL values at the M···M bond critical point of 2b–4b complexes are higher than those of 2c–4c (1b and 1c nearly the same), which indicates that at least the argentophilic interactions in the silver 2b–4b complexes are stronger, which again suggests that the argentophilic interactions in the silver 2b–4b complexes are stronger. In conclusion, ELF and LOL values, WBI indices, electron density (ρ(r)), interaction energy (Eint), crystallographic study, and photoluminescence spectra studies suggest that argentophilic interactions are most likely stronger than the aurophilic interactions in these complexes.

Conclusions

In summary, a series of four pairs of new large 12-membered silver 1b–4b and gold 1c–4c metallamacrocycles of amido-functionalized imidazole and 1,2,4-triazole-derived N-heterocyclic carbenes, displaying discrete singular metallophilic interactions, as corroborated by the single-crystal X-ray diffraction and the photoluminescence studies, have been synthesized. Furthermore, the computational studies indicate that the N-heterocyclic carbene-based ligand architecture led to strong metallophilic interactions in these complexes. The strength of the M···M interactions, as determined from the electron density at the bond critical point (BCP) from topological analysis and the Wiberg bond index (WBI) from the natural bond orbital (NBO) analysis, suggested that the metallophilic interaction decreased in the order 4b > 1b > 1c > 4c > 3b > 3c > 2b > 2c. The metallophilic interactions were visualized using scatter plots and NCI plots and were quantified using ELF functions. The steric factors at the N1-position and the charge of carbon attached to the N1-position influences the metallophilic interactions. In conclusion, both steric effects and the electronic effects of the N-heterocyclic carbene control the metallophilic interactions. ELF and LOL values, WBI indices, electron density (ρ(r)), interaction energy (Eint), crystallographic study, and photoluminescence spectra studies suggest that argentophilic interactions in 1b–4b complexes are stronger than the aurophilic interactions in the 1c–4c complexes.

Experimental Section

All manipulations were carried out using a combination of a glovebox and standard Schlenk techniques. Solvents were purified and degassed by standard procedures. 1-(4-Methylphenyl)imidazole,49 1-ethylimidazole,50 1-i-propyltriazole,51 2-chloro-N-(2,6-di-methylphenyl)acetamide,52 2-chloro-N-(2,6-di-i-propylphenyl)acetamide,52 and (SMe2)AuCl53 were synthesized by the modified literature procedures. 1H and 13C{1H} NMR spectra were recorded on Varian and Bruker 400 MHz and Bruker 500 MHz NMR spectrometers. 1H NMR peaks are labeled as singlet (s), doublet (d), triplet (t), doublet of doublets (dd), multiplet (m), and septet (sept). Infrared spectra were recorded on a PerkinElmer Spectrum One FT-IR spectrometer. Mass spectrometry measurements were done on a Micromass Q-Tof and Bruker Maxis Impact spectrometer. Elemental analysis was carried out on a Thermo Quest FLASH 1112 SERIES (CHNS) elemental analyzer. The crystals for the compound 1b–4b and 1c–4c were grown in CH3CN by a slow evaporation technique. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction studies were performed on a Rigaku Hg724+ diffractometer for compounds 1b–4b and on Bruker D8 Quest diffractometer for compounds 1c–4c, and crystal data collection and refinement parameters are summarized in Table S1. The structures were solved using SHELXT and refined via the full matrix least-squares method with SHELXL-2018/3, refining on F2.54 The CCDC – 1876407 (for 1b), 2170371 (for 1c), 1876404 (for 2b), 2173119 (for 2c), 1882493 (for 3b), 2160247 (for 3c), 1887221 (for 4b), and 2177632 (for 4c) contain supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.com.ac.uk/datarequest/cif.

Synthesis of 1-(4-Me-Phenyl)-3-N-(2,6-Me2-phenylacetamido)-imidazolium Chloride (1a)

1-(4-Me-Phenyl)-imidazole (2.00 g, 12.7 mmol) and 2-chloro-N-(2,6-Me2-phenyl)acetamide (2.76 g, 14.0 mmol) were refluxed in toluene (ca. 25 mL) for 12 h, after which the reaction mixture was cooled to 30 °C. The formed solid was filtered off and washed repeatedly with diethyl ether to give the crude product, which was purified by column chromatography on neutral silica using CHCl3/CH3OH (9.5:0.5 v/v) mixed medium to give the product (1a) as a light brown solid (1.86 g, 41%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz, 25 °C): δ, 10.48 (s, 1H, NCHN), 10.1 (s, 1H, NH), 7.81 (s, 1H, NCHCHN), 7.42 (s, 1H, NCHCHN), 7.35 (d, 2H, 3JHH = 8 Hz, 4-(CH3)C6H4), 7.18 (d, 2H, 3JHH = 8 Hz, 4-(CH3)C6H4), 6.9 (t, 1H, 3JHH = 6 Hz, 2,6-(CH3)2C6H3), 6.84 (d, 2H, 3JHH = 7 Hz, 2,6-(CH3)2C6H3), 5.71 (s, 2H, CH2), 2.29 (s, 3H, 4-(CH3)C6H4), 2.10 (s, 6H, 2,6-(CH3)2C6H3). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz, 25 °C): δ ppm, 163.6 (CO), 140.7 (4-(CH3)C6H4), 135.9 (NCHN), 135.3 (2,6-(CH3)2C6H3), 133.6 (4-(CH3)C6H4), 132 (2,6-(CH3)2C6H3), 130.9 (4-(CH3)C6H4), 127.9 (2,6-(CH3)2C6H3), 127.1 (2,6-(CH3)2C6H3), 124.6 (NCHCHN), 121.6 (4-(CH3)C6H4), 120.2 (NCHCHN), 51.9 (CH2), 21.1 (4-(CH3)C6H4), 18.7 (2,6-(CH3)2C6H3). IR data (cm–1) KBr pellet: 3406 (m), 3253 (m), 3049 (m), 1671 (s), 1547 (s), 1471 (m), 1441 (w), 1267 (w), 1239 (m), 1073 (w), 819 (w), 763 (w), 514 (w). HRMS (ESI): Calcd. for [M – Cl]+, [C20H22N3O]+m/z 320.1757; found m/z 320.1755. Anal. Calcd. for C20H22N3OCl: C, 67.50; H, 6.23; N, 11.81; Found: C, 67.20; H, 6.413; N, 11.57%.

Synthesis of [1-(4-Me-Phenyl)-3-N-(2,6-Me2-phenylacetamido)-imidazol-2-ylidene]2Ag2 (1b)

A solution of 1-(4-Me-phenyl)-3-(2,6-Me2-phenyl)acetamido-imidazolium chloride (1a) (0.905 g, 2.54 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (ca. 50 mL) was stirred with Ag2O (0.592 g, 2.55 mmol) in the dark at room temperature overnight. The reaction mixture was filtered over a pad of celite, and the solvent was evaporated. The residue was purified by column chromatography on neutral Al2O3 using the CHCl3/CH3OH (9.5:0.5) system to give the desired product (1b) as a grayish-white solid (0.551 g, 51%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz, 25 °C): δ ppm, 7.62 (s, 1H, NCHCHN), 7.16 (s, 1H, NCHCHN), 7.07 (d, 2H, 3JHH = 8 Hz, 4-(CH3)C6H4), 6.99 (d, 2H, 3JHH = 8 Hz, 4-(CH3)C6H4), 6.94 (d, 2H, 3JHH = 7 Hz, 2,6-(CH3)2C6H3), 6.90 (t, 1H, 3JHH = 7 Hz, 2,6-(CH3)2C6H3), 5.01 (s, 2H, CH2), 2.37 (s, 3H, 4-(CH3)C6H4), 1.90 (s, 6H, 2,6-(CH3)2C6H3). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz, 25 °C): δ ppm 176.9 (d, 1J109Ag–13Ccarbene = 251 Hz, 1J107Ag–13Ccarbene = 216 Hz, Ag–NCN), 168.1 (CO), 146.2 (2,6-(CH3)2C6H3), 138.8 (4-(CH3)C6H4), 137.3 (4-(CH3)C6H4), 132.1 (2,6-(CH3)2C6H3), 130.3 (4-(CH3)C6H4), 127.8 (2,6-(CH3)2C6H3), 123.6 (2,6-(CH3)2C6H3), 123.5, (4-(CH3)C6H4), 123.2 (NCHCHN), 121.5 (NCHCHN), 61.8 (CH2), 21.0 (4-(CH3)C6H4), 18.5 (2,6-(CH3)2C6H3). IR data (cm–1) KBr pellet: 3452 (m), 3165 (m), 2938 (m), 1686 (m), 1601 (s), 1579 (s), 1515 (s), 1467 (m), 1438 (m), 1271 (m), 1238 (m), 1093 (w), 818 (m), 767 (m), 541 (w). Anal. Calcd. for C40H40N6O2Ag2: C, 56.35; H, 4.73; N, 9.86; Found: C, 56.19; H, 4.797; N, 9.83%.

Synthesis of [1-(4-Me-Phenyl)-3-N-(2,6-Me2-phenylacetamido)-imidazol-2-ylidene]2Au2 (1c)

[1-(4-Me-Phenyl)-3-N-(2,6-Me2-phenylacetamido)-imidazol-2-ylidene]2Ag2 (1b) (0.107 g, 0.127 mmol) and (SMe2)AuCl (0.076 g, 0.260 mmol) were mixed in CH2Cl2 and stirred for 6 h at room temperature. An off-white AgCl solid precipitated out during the course of reaction, after which it was filtered. The filtrate was dried under vacuum to give the crude product, which was purified by column chromatography on neutral Al2O3 using a mixed medium of CH2Cl2/CH3OH (9.5:0.5, v/v) to give the product as a white-colored solid (1c) (0.042 g, 32%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz, 25 °C): δ ppm, 7.58 (d, 1H, 3JHH = 2 Hz, NCHCHN), 7.22 (d, 2H, 3JHH = 8 Hz, 4-(CH3)C6H4), 7.11 (d, 1H, 3JHH = 2 Hz, NCHCHN), 7.10–7.08 (m, 1H, 2,6-(CH3)2C6H3), 6.99 (d, 2H, 3JHH = 8 Hz, 4-(CH3)C6H4), 6.96–6.95 (m, 2H, 2,6-(CH3)2C6H3), 5.34 (s, 2H, CH2), 2.37 (s, 3H, 4-(CH3)C6H4), 2.00 (s, 6H, 2,6-(CH3)2C6H3). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz, 25 °C): δ ppm 169.2 (NCN), 168.9 (CO), 144.7 (2,6-(CH3)2C6H3), 138.7 (4-(CH3)C6H4), 136.6 (4-(CH3)C6H4), 133.1 (2,6-(CH3)2C6H3), 129.8 (4-(CH3)C6H4), 127.6 (2,6-(CH3)2C6H3), 124.4 (2,6-(CH3)2C6H3), 124.3, (4-(CH3)C6H4), 122.9 (NCHCHN), 121.0 (NCHCHN), 58.8 (CH2), 21.0 (4-(CH3)C6H4), 18.2 (2,6-(CH3)2C6H3). IR data (cm–1) KBr pellet: 3417 (br), 3117 (w), 2919 (m), 2356 (m), 1615 (s), 1516 (s), 1418 (w), 1099 (m), 765 (w). 679 (w). HRMS (ESI): Calcd. for [M + H]+, [C40H41N6O2Au2]+m/z 1031.2617; found m/z 1031.2615. Anal. Calcd. for C40H40N6O2Au2: C, 46.61; H, 3.91; N, 8.15; Found: C, 46.43; H, 4.076; N, 8.18%.

Synthesis of 1-(Methyl)-3-N-(2,6-di-i-propylphenylacetamido)-imidazolium Chloride (2a)

1-Methyl imidazole (0.510 g, 6.21 mmol) and 2-chloro-N-(2,6-di-i-propylphenyl)acetamide (1.58 g, 7.02 mmol) were refluxed overnight in toluene (ca. 50 mL), after which the reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature. The solvent was evaporated, and the remaining solid was washed repeatedly with diethyl ether to give the white solid, which was purified by column chromatography on neutral silica using the CHCl3/CH3OH (9.5:0.5) system to give the desired product (2a) as a white solid (1.04 g, 50%). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz, 25 °C): δ ppm, 10.48 (s, 1H, NCHN), 9.24 (s, 1H, NH), 7.70 (s, 1H, NCHCHN), 7.67 (s, 1H, NCHCHN), 7.14 (t, 1H, 3JHH = 8 Hz, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 7.03 (d, 2H, 3JHH = 8 Hz, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 5.32 (s, 2H, CH2), 3.79 (s, 3H, NCH3), 2.98 (sept, 2H, 3JHH = 7 Hz, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 1.02 (br, 6H, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 0.96 (br, 6H, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3). 13C{1H} NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz, 25 °C): δ ppm, 165.3 (CO), 146.4 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 138.2 (NCHN), 132.1 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 128.2 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 123.9 (NCHCHN), 123.7 (NCHCHN), 123.4 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 51.1 (CH2), 36.3 (NCH3), 28.4 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 24.4 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 23.7 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3). IR data (cm–1) KBr pellet: 3445 (m), 3145 (m), 3051 (m), 2964 (s), 2861 (m), 1696 (s), 1540 (m), 1461 (w), 1266 (w), 1176 (m), 954 (w), 800 (w), 628 (w). HRMS (ESI): Calcd. for [M – Cl]+, [C18H26N3O]+m/z 300.2070; found m/z 300.2076. Anal. Calcd. for C18H26N3OCl: C, 64.37; H, 7.80; N, 12.51; Found: C, 64.05; H, 7.634; N, 12.39%.

Synthesis of [1-(Methyl)-3-N-(2,6-di-i-propylphenylacetamido)-imidazol-2-ylidene]2Ag2 (2b)

A solution of 1-(methyl)-3-N-(2,6-di-i-propylphenyl)acetamido-imidazolium chloride (2a) (0.504g, 1.50 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (ca. 50 mL) was stirred with Ag2O (0.358 g, 1.54 mmol) in the dark at room temperature overnight. The solvent was evaporated, and the residue was purified by column chromatography on neutral Al2O3 using the CHCl3/CH3OH (9.5:0.5) system to give the desired product (2b) as a grayish-white solid (0.152 g, 25%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz, 25 °C): δ ppm, 7.31 (s, 1H, NCHCHN), 7.18 (t, 1H, 3JHH = 9 Hz, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 7.05 (d, 2H, 3JHH = 9 Hz, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 6.92 (s, 1H, NCHCHN), 5.31 (s, 2H, CH2), 3.79 (s, 3H, NCH3), 3.03 (sept, 2H, 3JHH = 8 Hz, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 1.02 (d, 12H, 3JHH = 8 Hz, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz, 25 °C): δ ppm, 182.3 (Ag–NCN), 166.8 (CO), 146.1 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 131.2 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 128.0 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 123.2 (NCHCHN), 123.1 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 121.7 (NCHCHN), 53.9 (CH2), 38.7 (NCH3), 28.6 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 23.7 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3). IR data (cm–1) KBr pellet: 3442 (w), 3163 (w), 2957 (s), 2866 (m), 1694 (m), 1529 (s), 1460 (m), 1266 (w), 798 (w), 743 (m). Anal. Calcd. for C36H48N6O2Ag2: C, 53.21; H, 5.95; N, 10.34; Found: C, 53.40; H, 6.373; N, 10.34%.

Synthesis of [1-(Methyl)-3-N-(2,6-di-i-propylphenylacetamido)-imidazol-2-ylidene]2Au2 (2c)

[1-(Methyl)-3-N-(2,6-di-i-propylphenylacetamido)-imidazol-2-ylidene]2Ag2 (2b) (0.124 g, 0.153 mmol) and (SMe2)AuCl (0.090 g, 0.307 mmol) were mixed in CH2Cl2 and stirred for 6 h at room temperature. An off-white AgCl solid precipitated out during the course of reaction, after which it was filtered. The filtrate was dried under vacuum to give the crude product, which was purified by column chromatography on neutral Al2O3 using a mixed medium of CH2Cl2/CH3OH (9.5:0.5, v/v) to give the product as a white-colored solid (2c) (0.041 g, 27%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz, 25 °C): δ ppm, 7.30 (t, 1H, 3JHH = 8 Hz, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 7.25 (d, 1H, 3JHH = 2 Hz, NCHCHN), 7.16 (d, 2H, 3JHH = 8 Hz, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 7.00 (d, 1H, 3JHH = 2 Hz, NCHCHN), 5.07 (s, 2H, CH2), 3.87 (s, 3H, NCH3), 3.03 (sept, 2H, 3JHH = 7 Hz, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 1.16 (d, 12H, 3JHH = 7 Hz, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz, 25 °C): δ ppm, 172.1 (NCN), 165.3 (CO), 146.2 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 129.8 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 128.8 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 123.5 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 122.2 (NCHCHN), 122.1 (NCHCHN), 54.0 (CH2), 38.4 (NCH3), 28.9 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 23.7 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3). IR data (cm–1) KBr pellet: 3454 (s), 2964 (s), 2866 (m), 1666 (s), 1530 (m), 1467 (m), 1237 (w), 791 (w), 739 (m). HRMS (ESI): Calcd. for [M + Na]+, [C36H48N6O2Au2Na]+m/z 1013.3062; found m/z 1013.3067. Anal. Calcd. for C36H48N6O2Au2: C, 43.64; H, 4.88; N, 8.48; Found: C, 43.30; H, 4.768; N, 8.55%.

Synthesis of 1-(Ethyl)-3-N-(2,6-di-i-propylphenylacetamido)-imidazolium Chloride (3a)

1-Ethylimidazole (1.00 g, 10.49 mmol) and 2-chloro-N-(2,6-di-i-propylphenyl)acetamide (2.66 g, 10.49 mmol) were refluxed overnight in toluene (ca. 25 mL), after which the reaction mixture was cooled to 30 °C. The formed solid was filtered off and washed repeatedly with Et2O to give the crude product, which was purified by column chromatography on neutral alumina using CHCl3/CH3OH (9.5:0.5 v/v) mixed medium to give the product (3a) as a white solid (1.28 g, 35%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz, 25 °C): δ ppm, 10.53 (s, 1H, NCHN), 9.84 (s, 1H, NH), 7.69 (s, 1H, NCHCHN), 7.29 (s, 1H, NCHCHN), 7.25 (t, 1H, 3JHH = 8 Hz, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 7.11 (d, 2H, 3JHH = 7 Hz, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 5.57 (s, 2H, CH2), 4.16 (q, 2H, 3JHH = 7 Hz, CH2CH3), 3.03 (sept, 2H, 3JHH = 7 Hz, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 1.43 (t, 3H, 3JHH = 7 Hz, CH2CH3), 1.08 (br, 12H, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz, 25 °C): δ ppm, 164.7 (CO), 146.1 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 136.7 (NCHN), 131.0 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 128.3 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 123.7 (NCHCHN), 123.2 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 121.2 (NCHCHN), 51.6 (CH2), 45.1 (CH2CH3), 28.6 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 24.0 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 23.2 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 15.3 (CH2CH3). HRMS (ESI): Calcd. for [M – Cl]+, [C19H28N3O]+m/z 314.2227; found m/z 314.2229. Anal. Calcd. for C19H28N3OCl: C, 65.22; H, 8.07; N, 12.01; Found: C, 64.85; H, 7.979; N, 11.40%.

Synthesis of [1-(Ethyl)-3-N-(2,6-di-i-propylphenylacetamido)-imidazol-2-ylidene]2Ag2 (3b)

A solution of 1-(ethyl)-3-N-(2,6-di-i-propylphenyl)acetamido-imidazolium chloride (3a) (0.714 g, 2.04 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (ca. 40 mL) was stirred with Ag2O (0.482 g, 2.07 mmol) in the dark at room temperature overnight. The solvent was evaporated, and the residue was purified by column chromatography on neutral Al2O3 using CHCl3/CH3OH (9.5:0.5 v/v) system to give the desired product (3b) as a white solid (0.324 g, 38%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz, 25 °C): δ ppm, 7.53 (s, 1H, NCHCHN), 7.06 (br s, 3H, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 6.93 (s, 1H, NCHCHN), 4.96 (s, 2H, CH2), 3.88 (quat, 2H, 3JHH = 7 Hz, CH2CH3), 3.16 (sept, 2H, 3JHH = 7 Hz, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 1.26 (t, 3H, 3JHH = 7 Hz, CH2CH3), 1.15 (d, 6H, 3JHH = 7 Hz, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 1.06 (d, 6H, 3JHH = 7 Hz, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz, 25 °C): δ ppm, 176.2 (d, 1J109Ag–13Ccarbene = 249 Hz, 1J107Ag–13Ccarbene = 219 Hz, Ag–NCN), 169.1 (CO), 143.6 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 142.5 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 124.6 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 123.1 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 122.9 (NCHCHN), 120.1 (NCHCHN), 61.8 (CH2), 46.8 (CH2CH3), 28.1 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 23.9 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 23.8 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 16.9 (CH2CH3). IR data (cm–1) KBr pellet: 3411 (w), 3124 (w), 2962 (m), 2867 (m), 1596 (s), 1574 (s), 1463 (w), 1438 (m), 1411 (m), 1225 (w), 752 (w). Anal. Calcd. for C38H52N6O2Ag2: C, 54.30; H, 6.24; N, 10.00; Found: C, 54.80; H, 6.349; N, 9.96%.

Synthesis of [1-(Ethyl)-3-N-(2,6-di-i-propylphenylacetamido)-imidazol-2-ylidene]2Au2 (3c)

[1-(Ethyl)-3-N-(2,6-di-i-propylphenylacetamido)-imidazol-2-ylidene]2Ag2 (3b) (0.151 g, 0.180 mmol) and (SMe2)AuCl (0.107 g, 0.363 mmol) were mixed in CH2Cl2 and stirred for 6 h at room temperature. An off-white AgCl solid precipitated out during the course of reaction, after which it was filtered. The filtrate was dried under vacuum to give the crude product, which was purified by column chromatography on neutral Al2O3 using a mixed medium of CH2Cl2/CH3OH (9.5:0.5, v/v) to give the product as a white-colored solid (3c) (0.076 g, 41%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz, 25 °C): δ ppm, 7.51 (d, 1H, 3JHH = 2 Hz, NCHCHN), 7.1 (s, 3H, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 6.84 (d, 1H, 3JHH = 2 Hz, NCHCHN), 5.29 (s, 2H, CH2), 3.99 (q, 2H, 3JHH = 7 Hz, CH2CH3), 3.26 (sept, 2H, 3JHH = 7 Hz, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 1.32 (t, 3H, 3JHH = 7 Hz, CH2CH3), 1.21 (d, 6H, 3JHH = 7 Hz, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 1.02 (d, 6H, 3JHH = 7 Hz, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz, 25 °C): δ ppm, 169.9 (NCN), 168.4 (CO), 143.4 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 141.9 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 125.5 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 122.9 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 122.4 (NCHCHN), 119.5 (NCHCHN), 58.8 (CH2), 46.3 (CH2CH3), 27.7 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 24.1 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 23.8 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 16.5 (CH2CH3). IR data (cm–1) KBr pellet: 3433 (br), 3127 (w), 2961 (m), 2866 (m), 1698 (s), 1598 (s), 1578 (s), 1465 (w), 1441 (m), 1416 (m), 1229 (w), 760 (w). HRMS (ESI): Calcd. for [M + H]+, [C38H53N6O2Au2]+m/z 1019.3556; found m/z 1019.3553. Anal. Calcd. for C38H52N6O2Au2: C, 44.80; H, 5.14; N, 8.25; Found: C, 44.79; H, 5.143; N, 8.56%.

Synthesis of 1-(i-Propyl)-4-N-(2,6-di-i-propylphenylacetamido)-1,2,4-triazolium Chloride (4a)

1-i-Propyl 1,2,4-triazole (1.00 g, 9.04 mmol) and 2-chloro-N-(2,6-di-i-propylphenyl)acetamide (2.53 g, 9.97 mmol) were refluxed overnight in toluene (ca. 25 mL), after which the reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature. The solvent was evaporated, and the remaining solid was washed repeatedly with Et2O to give a solid, which was purified by column chromatography on neutral silica using the CHCl3/CH3OH (9.5:0.5 v/v) system to give the product (4a) as a white solid (1.67 g, 51%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz, 25 °C): δ, 11.26 (s, 1H, NCHN), 10.63 (s, 1H, NH), 8.89 (s, 1H, NCHCHN), 7.26 (t, 1H, 3JHH = 8 Hz, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2C6H3), 7.13 (d, 2H, 3JHH = 8 Hz, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2C6H3), 5.88 (s, 2H, CH2), 4.85 (sept, 1H, 3JHH = 7 Hz, NCH(CH3)2), 3.08 (sept, 2H, 3JHH = 7 Hz, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2C6H3), 1.58 (d, 6H, 3JHH = 6 Hz, NCH(CH3)2), 1.13 (d, 12H, 3JHH = 6 Hz, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2C6H3). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz, 25 °C): δ ppm, 164.1 (CO), 145.9 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 144.5 (NC(5)HN), 141.9 (NC(3)HN), 130.9 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 128.3 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 123.3 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 56.2 (NCH(CH3)2), 50.1 (CH2), 28.6 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 24.1 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 23.2 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 21.7 (NCH(CH3)2). IR data (cm–1) KBr pellet: 3441 (w), 3195 (m), 2964 (s), 2931 (m), 1697 (s), 1530 (m), 1468 (m), 1360 (w), 1238 (m), 1057 (w), 984 (m), 715 (w). HRMS (ESI): Calcd. for [M – Cl]+, [C19H29N4O]+m/z 329.2336; found m/z 329.2334. Anal. Calcd. for C19H29N4OCl: C, 62.54; H, 8.01; N, 15.35; Found: C, 62.65; H, 7.905; N, 15.44%.

Synthesis of [1-(i-Propyl)-4-N-(2,6-di-i-propylphenylacetamido)-1,2,4-triazol-2-ylidene]2Ag2 (4b)

A solution of 1-(i-propyl)-4-N-(2,6-di-i-propylphenyl)acetamido-1,2,4-triazolium chloride (4a) (0.502 g, 1.37 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (ca. 40 mL) was stirred with Ag2O (0.329 g, 1.42 mmol) in the dark at room temperature overnight. The solvent was evaporated, and the residue was purified by column chromatography on neutral Al2O3 using the CHCl3:CH3OH (9.5:0.5) system to give the product (4b) as a gray solid (0.207 g, 34%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz, 25 °C): δ ppm, 8.46 (s, 1H, NCHN), 7.24 (t, 1H, 3JHH = 8 Hz, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 7.10 (d, 2H, 3JHH = 7 Hz, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 5.52 (s, 2H, CH2), 4.97 (sept, 1H, 3JHH = 7 Hz, NCH(CH3)2), 3.00 (sept, 2H, 3JHH = 7 Hz, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 1.58 (d, 6H, 3JHH = 7 Hz, NCH(CH3)2), 1.06 (d, 12H, 3JHH = 7 Hz, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz, 25 °C): δ ppm, 180.9 (s, Ag–NCN), 166.0 (CO), 145.8 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 143.3 (NCHN), 130.8 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 128.3 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 123.3 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 56.3 (NCH(CH3)2), 51.3 (CH2), 28.6 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 23.6 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 22.8 (NCH(CH3)2). IR data (cm–1) KBr pellet: 3512 (m), 3190 (m), 2964 (s), 2869 (m), 1677 (m), 1590 (s), 1531 (s), 1444 (m), 1383 (m), 976 (w), 797 (w), 722 (w). Anal. Calcd. for C38H54N8O2Ag2: C, 52.42; H, 6.25; N, 12.87; Found: C, 52.37; H, 6.366; N, 12.57%.

Synthesis of [1-(i-Propyl)-4-N-(2,6-di-i-propylphenylacetamido)-1,2,4-triazol-2-ylidene]2Au2 (4c)

[1-(i-Propyl)-4-N-(2,6-di-i-propylphenylacetamido)-1,2,4-triazol-2-ylidene]2Ag2 (4b) (0.120 g, 0.138 mmol) and (SMe2)AuCl (0.082 g, 0.280 mmol) were mixed in CH2Cl2 and stirred for 6 h at room temperature. An off-white AgCl solid precipitated out during the course of reaction, after which it was filtered. The filtrate was dried under vacuum to give the crude product, which was purified by column chromatography on neutral Al2O3 using a mixed medium of CH2Cl2/CH3OH (9.5:0.5, v/v) to give the product as a white-colored solid (4c) (0.038 g, 26%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz, 25 °C): δ ppm, 8.33 (s, 1H, NCHN), 7.30 (t, 1H, 3JHH = 8 Hz, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 7.15 (d, 2H, 3JHH = 7 Hz, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 5.12–5.06 (m, 3H, CH2 and NCH(CH3)2), 3.07 (sept, 2H, 3JHH = 7 Hz, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 1.49 (d, 6H, 3JHH = 7 Hz, NCH(CH3)2), 1.16 (d, 12H, 3JHH = 7 Hz, 2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz, 25 °C): δ ppm, 171.8 (NCN), 164.7 (CO), 146.2 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 143.3 (NCHN), 129.8 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 128.8 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 123.5 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 55.9 (NCH(CH3)2), 51.0 (CH2), 28.8 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 23.7 (2,6-(CH(CH3)2)2-C6H3), 22.2 (NCH(CH3)2). IR data (cm–1) KBr pellet: 3482 (br), 3122 (w), 2965 (m), 1672 (s), 1521 (s), 1451 (m), 796 (m), 718 (w). HRMS (ESI): Calcd. for [M + H]+, [C38H55N8O2Au2]+m/z 1049.3774; found m/z 1049.3770. Anal. Calcd. for C38H54N8O2Au2: C, 43.52; H, 5.19; N, 10.68; Found: C, 42.95; H, 5.457; N, 10.03%.

General Procedure for Photophysical Study

Using a Shimadzu UV–NIR instrument, absorption spectra of compounds 1(a–c), 2(a–c), 3(a–c), and 4(a–c) were recorded in CHCl3 solution (1 × 10–3 M) at 25 °C. Using a Varian Eclipse spectrophotometer, emission spectra of compounds 1(a–c), 2(a–c), 3(a–c), and 4(a–c) were recorded in CHCl3 solution (1 × 10–3 M) at 25 °C upon excitation at 242 nm in quartz cuvettes. Solid-state emission was recorded on a Horiba Fluoromax + (RM 360) instrument at 25 °C upon excitation at 242 nm in quartz glass slab for the compounds 1(a–c), 2(a–c), 3(a–c), and 4(a–c) by mixing with NaCl in the ratio of 1:100 and grinding the mixture to a powder form.

Computational Methods

DFT calculations were done using the Gaussian 09 suite of the programs.55 All calculations were performed using the UB3LYP-D256 functional in conjunction with an all-electron def2-TZVP57 basis set for all atoms. To take into consideration the relativistic effects, Douglas–Kroll–Hess (DKH) Hamiltonian58 has been employed. To avoid the lattice effects on the geometry, X-ray structures were utilized as such. And single-point calculations, including relativistic effects, were performed, and the generated wavefunction was further used for the natural bond orbital (NBO).59 However, we assumed that intermolecular interactions present in the crystal have no significant impact on the metallophilic interactions. To comprehend the metallophilic interactions, the atoms in molecules (AIM) analysis,60 electron localization function (ELF),44 and noncovalent interaction (NCI)41 analyses were carried out on all complexes using Multiwfn software.61 Isosurfaces of the reduced density gradient (RDG)42 were rendered by the VMD 1.9.1 program62 using the output files of Multiwfn.61

Using the polarized continuum model and TD-DFT at the PBE1PBE63 hybrid functional level, which includes 25% exchange and 75% correlation in chloroform (CHCl3) media, the absorption properties were estimated. It has been demonstrated that this level of the theoretical approach is trustworthy for 5d transition-metal complex systems.64 Finally, a natural transition orbital (NTO) analysis was carried out to better understand the nature of excited states involved in absorption processes.65

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Department of Science and Technology (DST), India (Grant Nos. SR/S1/IC-50/2011, EMR/2014/000254, CRG/2019/000029) and Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), New Delhi, (01(2880)/17/EMR-II) India for financial support. The Single-Crystal X-ray Diffraction Facility, Department of Chemistry, IIT Bombay is gratefully acknowledged for the crystallographic characterization data. A.P.P. thanks CSIR, New Delhi and C.N. S.K.P. and S.R.D. thank IIT Bombay for a research fellowship.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c06729.

1H NMR, 13C{1H} NMR, IR, HRMS, and CHN data of the amido-functionalized NHC ligands 1a–4a; 1H NMR, 13C{1H} NMR, IR, CHN data, and the computational data of the silver 1b–4b; 1H NMR, 13C{1H} NMR, IR, HRMS, CHN data, and the computational data of gold 1c–4c complexes; and emission spectra for the silver 1b–4b and gold 1c–4c complexes (PDF)

Author Present Address

‡ Laboratory of Macromolecular and Organic Chemistry, Institute for Complex Molecular Systems, Department of Chemical Engineering and Chemistry, Eindhoven University of Technology, 5600 MB Eindhoven, The Netherlands

Author Contributions

† A.P.P., S.K.P., and C.N. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Sculfort S.; Braunstein P. Intramolecular d10–d10 interactions in heterometallic clusters of the transition metals. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 2741–2760. 10.1039/C0CS00102C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Pyykkö P. Theoretical Chemistry of Gold. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 4412–4456. 10.1002/anie.200300624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyykkö P. Strong Closed-Shell Interactions in Inorganic Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 1997, 97, 597–636. 10.1021/cr940396v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayaraghavan R. K.; Chandran D.; Vijayaraghavan R. K.; McCoy A. P.; Daniels S.; McNally P. J. Highly enhanced UV responsive conductivity and blue emission in transparent CuBr films: implication for emitter and dosimeter applications. J. Mater. Chem. C 2017, 5, 10270–10279. 10.1039/C7TC02838E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; Kishimura A.; Yamashita T.; Yamaguchi K.; Aida T. Rewritable phosphorescent paper by the control of competing kinetic and thermodynamic self-assembling events. Nat. Mater. 2005, 4, 546–549. 10.1038/nmat1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkelis J. J.; Barnett S. A.; Harding L. P.; Hardie M. J. Coordination Polymers Utilizing N-Oxide Functionalized Host Ligands. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 51, 10657–10674. 10.1021/ic300940k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Serpe A.; Artizzu F.; Marchiò L.; Mercuri M. L.; Pilia L.; Deplano P. Argentophilic Interactions in Mono-, Di-, and Polymeric Ag(I) Complexes with N,N′-Dimethyl-piperazine-2,3-dithione and Iodide. Cryst. Growth Des. 2011, 11, 1278–1286. 10.1021/cg1015065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; Bayler A.; Schier A.; Bowmaker G. A.; Schmidbaur H. Gold Is Smaller than Silver. Crystal Structures of [Bis(trimesitylphosphine)gold(I)] and [Bis(trimesitylphosphine)silver(I)] Tetrafluoroborate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 7006–7007. 10.1021/ja961363v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Rubio J.; Vicente J. The Coordination and Supramolecular Chemistry of Gold Metalloligands. Chem. – Eur. J. 2018, 24, 32–46. 10.1002/chem.201703574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Yam V. W.-W.; Wong K. M.-C. Luminescent metal complexes of d6, d8 and d10 transition metal centres. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 11579–11592. 10.1039/C1CC13767K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jassal A. K. Advances in ligand-unsupported argentophilic interactions in crystal engineering: an emerging platform for supramolecular architectures. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2020, 7, 3735–3764. 10.1039/D0QI00447B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J.; Lu Z.; Wu K.; Ning G.-H.; Li D. Coinage-Metal-Based Cyclic Trinuclear Complexes with Metal–Metal Interactions: Theories to Experiments and Structures to Functions. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 9675–9742. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yam V. W.-W.; Au V. K.-M.; Leung S. Y.-L. Light-Emitting Self-Assembled Materials Based on d8 and d10 Transition Metal Complexes. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 7589–7728. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Yang C.; Elbjeirami O.; Gamage C. S. P.; Dias H. V. R.; Omary M. A. Luminescence enhancement and tuning via multiple cooperative supramolecular interactions in an ion-paired multinuclear complex. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 7434–7436. 10.1039/C1CC11161B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rana A.; Kumar Jana S.; Pal T.; Puschmann H.; Zangrando E.; Dalai S. Electrical conductivity and luminescence properties of two silver(I) coordination polymers with heterocyclic nitrogen ligands. J. Solid State Chem. 2014, 216, 49–55. 10.1016/j.jssc.2014.04.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; Dennehy M.; Amo-Ochoa P.; Freire E.; Suárez S.; Halac E.; Baggio R. Structure and electrical properties of a one-dimensional polymeric silver thiosaccharinate complex with argentophilic interactions. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. C: Struct. Chem. 2018, 74, 186–193. 10.1107/S2053229618000128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidbaur H.; Schier A. Argentophilic Interactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 746–784. 10.1002/anie.201405936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidbaur H.; Schier A. Aurophilic interactions as a subject of current research: an up-date. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 370–412. 10.1039/C1CS15182G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidbaur H.; Raubenheimer H. G. Excimer and Exciplex Formation in Gold(I) Complexes Preconditioned by Aurophilic Interactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 14748–14771. 10.1002/anie.201916255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harisomayajula N. V. S.; Makovetskyi S.; Tsai Y.-C. Cuprophilic Interactions in and between Molecular Entities. Chem. – Eur. J. 2019, 25, 8936–8954. 10.1002/chem.201900332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung O.-S.; Kim Y. J.; Lee Y.-A.; Kang S. W.; Choi S. N. Tunable Transannular Silver–Silver Interaction in Molecular Rectangles. Cryst. Growth Des. 2004, 4, 23–24. 10.1021/cg0341048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez S. A cartography of the van der Waals territories. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 8617–8636. 10.1039/C3DT50599E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Hu S.-Z.; Zhou Z.-H.; Robertson B. E. Consistent approaches to van der Waals radii for the metallic elements. Z. Kristallogr. 2009, 224, 375–383. 10.1524/zkri.2009.1158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; Mantina M.; Chamberlin A. C.; Valero R.; Cramer C. J.; Truhlar D. G. Consistent van der Waals Radii for the Whole Main Group. J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113, 5806–5812. 10.1021/jp8111556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondi A. van der Waals volumes and radii. J. Phys. Chem. A 1964, 68, 441–451. 10.1021/j100785a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Batsanov S. S. Van der Waals Radii of Elements. Inorg. Mater. 2001, 37, 871–885. 10.1023/A:1011625728803. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Korneeva E. V.; Smolentsev A. I.; Antzutkin O. N.; Ivanov A. V. A novel silver(I) di-iso-butyldithiocarbamate: Unusually complicated 1-D polymeric structure, multiple ligand-supported Ag–Ag interactions and its capability to bind gold(III). Preparation, structural organisation and (13C, 15N) CP-MAS NMR of [Ag6(S2CNiBu2)6]n and [Au(S2CNiBu2)2][AgCl2]. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2021, 525, 120383 10.1016/j.ica.2021.120383. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; Vikulova E. S.; Sukhikh T. S.; Gulyaev S. A.; Ilyin I. Y.; Morozova N. B. Structural Diversity of Silver Fluorinated β-Diketonates: Effect of the Terminal Substituent and Solvent. Molecules 2022, 27, 677 10.3390/molecules27030677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Xia C.-K.; Min Y.-Y.; Yang K.; Sun W.; Jiang D.-L.; Chen M. Syntheses, Crystal Structures, and Properties of Three Novel Silver–Organic Frameworks Assembled from 1,2,3,5-Benzenetetracarboxylic Acid Based on Argentophilic Interactions. Cryst. Growth Des. 2018, 18, 1978–1986. 10.1021/acs.cgd.7b01319. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; Che C.-M.; Tse M.-C.; Chan M. C. W.; Cheung K.-K.; Phillips D. L.; Leung K.-H. Spectroscopic Evidence for Argentophilicity in Structurally Characterized Luminescent Binuclear Silver(I) Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 2464–2468. 10.1021/ja9904890. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; Kobialka S.; Müller-Tautges C.; Schmidt M. T. S.; Schnakenburg G.; Hollóczki O.; Kirchner B.; Engeser M. Stretch Out or Fold Back? Conformations of Dinuclear Gold(I) N-Heterocyclic Carbene Macrocycles. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 6100–6111. 10.1021/ic502751s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Monticelli M.; Baron M.; Tubaro C.; Bellemin-Laponnaz S.; Graiff C.; Bottaro G.; Armelao L.; Orian L. Structural and Luminescent Properties of Homoleptic Silver(I), Gold(I), and Palladium(II) Complexes with nNHC-tzNHC Heteroditopic Carbene Ligands. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 4192–4205. 10.1021/acsomega.8b03668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Espada M. F.; Campos J.; López-Serrano J.; Poveda M. L.; Carmona E. Methyl-, Ethenyl-, and Ethynyl-Bridged Cationic Digold Complexes Stabilized by Coordination to a Bulky Terphenylphosphine Ligand. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 15379–15384. 10.1002/anie.201508931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (acccessed 2022/06/30); Nakamura T.; Ogushi S.; Arikawa Y.; Umakoshi K. Preparations of a series of coinage metal complexes with pyridine-based bis(N-heterocyclic carbene) ligands including transmetalation to palladium complexes. J. Organomet. Chem. 2016, 803, 67–72. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2015.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ray L.; Shaikh M. M.; Ghosh P. Shorter argentophilic interaction than aurophilic interaction in a pair of dimeric {(NHC)MCl}(2) (M= Ag, Au) complexes supported over a N/O-functionalized N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) ligand. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 47, 230–240. 10.1021/ic701830m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilar Carranza M.; Manzano B. R.; Jalón F. A.; Rodríguez A. M.; Santos L.; Moreno M. Experimental and theoretical evidence of unsupported Ag–Ag interactions in complexes with triazine-based ligands. Subtle effects of the symmetry of the triazine substituents. New J. Chem. 2013, 37, 3183–3194. 10.1039/C3NJ00738C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; Baron M.; Dalla Tiezza M.; Carlotto A.; Tubaro C.; Graiff C.; Orian L. Di(N-heterocyclic carbene) gold(III) imidate complexes obtained by oxidative addition of N-halosuccinimides. J. Organomet. Chem. 2018, 866, 144–152. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2018.03.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidbaur H.; Graf W.; Müller G. Weak Intramolecular Bonding Relationships: The Conformation-Determining Attractive Interaction between Gold(I) Centers. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1988, 27, 417–419. 10.1002/anie.198804171. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidbaur H. The fascinating implications of new results in gold chemistry. Gold Bull. 1990, 23, 11–21. 10.1007/BF03214710. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; Jiang Y.; Alvarez S.; Hoffmann R. Binuclear and polymeric gold(I) complexes. Inorg. Chem. 1985, 24, 749–757. 10.1021/ic00199a023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; Jansen M. Homoatomic d10–d10 Interactions: Their Effects on Structure and Chemical and Physical Properties. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1987, 26, 1098–1110. 10.1002/anie.198710981. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidbaur H. The aurophilicity phenomenon: A decade of experimental findings, theoretical concepts and emerging applications. Gold Bull. 2000, 33, 3–10. 10.1007/BF03215477. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andris E.; Andrikopoulos P. C.; Schulz J.; Turek J.; Růžička A.; Roithová J.; Rulíšek L. Aurophilic Interactions in [(L)AuCl]···[(L′)AuCl] Dimers: Calibration by Experiment and Theory. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 2316–2325. 10.1021/jacs.7b12509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Q.; Borsley S.; Nichol G. S.; Duarte F.; Cockroft S. L. The Energetic Significance of Metallophilic Interactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 12617–12623. 10.1002/anie.201904207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrejić M.; Mata R. A. Study of ligand effects in aurophilic interactions using local correlation methods. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 18115–18122. 10.1039/C3CP52931B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Mirzadeh N.; Privér S. H.; Blake A. J.; Schmidbaur H.; Bhargava S. K. Innovative Molecular Design Strategies in Materials Science Following the Aurophilicity Concept. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 7551–7591. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidbaur H.; Schier A. A briefing on aurophilicity. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 1931–1951. 10.1039/B708845K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R.-F.; Franzese C. A.; Malek R.; Żuchowski P. S.; Ángyán J. G.; Szczȩśniak M. M.; Chałasiński G. Aurophilic Interactions from Wave Function, Symmetry-Adapted Perturbation Theory, and Rangehybrid Approaches. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011, 7, 2399–2407. 10.1021/ct200243s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Riedel S.; Pyykkö P.; Mata R. A.; Werner H.-J. Comparative calculations for the A-frame molecules [S(MPH3)2] (M=Cu, Ag, Au) at levels up to CCSD(T). Chem. Phys. Lett. 2005, 405, 148–152. 10.1016/j.cplett.2005.02.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pyykkö P.; Zhao Y. Ab initio Calculations on the (ClAuPH3)2 Dimer with Relativistic Pseudopotential: Is the “Aurophilic Attraction” a Correlation Effect?. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1991, 30, 604–605. 10.1002/anie.199106041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Magnko L.; Schweizer M.; Rauhut G.; Schütz M.; Stoll H.; Werner H.-J. A comparison of metallophilic attraction in (X–M–PH3)2 (M = Cu, Ag, Au; X = H, Cl). Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2002, 4, 1006–1013. 10.1039/B110624D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Grady E.; Kaltsoyannis N. Does metallophilicity increase or decrease down group 11? Computational investigations of [Cl–M–PH3]2 (M = Cu, Ag, Au, [111]). Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2004, 6, 680–687. 10.1039/B312242E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar D.; Prakasham A. P.; Das S.; Datta A.; Ghosh P. Cyanosilylation of Aromatic Aldehydes by Cationic Ruthenium(II) Complexes of Benzimidazole-Derived O-Functionalized N-Heterocyclic Carbenes at Ambient Temperature under Solvent-Free Conditions. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 1922–1938. 10.1021/acsomega.7b02090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samantaray M. K.; Pang K.; Shaikh M. M.; Ghosh P. From large 12-membered macrometallacycles to ionic (NHC)(2)M+Cl- type complexes of gold and silver by modulation of the N-substituent of amido-functionalized N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) Ligands. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 47, 4153–4165. 10.1021/ic702186g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shmelev N. Y.; Okubazghi T. H.; Abramov P. A.; Komarov V. Y.; Rakhmanova M. I.; Novikov A. S.; Gushchin A. L. Intramolecular aurophilic interactions in dinuclear gold(i) complexes with twisted bridging 2,2′-bipyridine ligands. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 12448–12456. 10.1039/D1DT02164H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Krätschmer F.; Gui X.; Gamer M. T.; Klopper W.; Roesky P. W. Systematic investigation of the influence of electronic substituents on dinuclear gold(i) amidinates: synthesis, characterisation and photoluminescence studies. Dalton Trans. 2022, 51, 5471–5479. 10.1039/D1DT03795A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi U. M.; Bauer A.; Schmidbaur H. Covalent radii of four-co-ordinate copper(I), silver(I) and gold(I): crystal structures of [Ag(AsPh3)4]BF4 and [Au(AsPh3)4]BF4. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1997, 2865–2868. 10.1039/A702582C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leang S. S.; Zahariev F.; Gordon M. S. Benchmarking the performance of time-dependent density functional methods. J. Chem. Phys. 2012, 136, 104101 10.1063/1.3689445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Jacquemin D.; Perpète E. A.; Scuseria G. E.; Ciofini I.; Adamo C. TD-DFT Performance for the Visible Absorption Spectra of Organic Dyes: Conventional versus Long-Range Hybrids. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008, 4, 123–135. 10.1021/ct700187z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brands M. B.; Nitsch J.; Guerra C. F. Relevance of Orbital Interactions and Pauli Repulsion in the Metal–Metal Bond of Coinage Metals. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 2603–2608. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b02994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatfaoui S.; Sagaama A.; Issaoui N.; Roisnel T.; Marouani H. Synthesis, experimental, theoretical study and molecular docking of 1-ethylpiperazine-1,4-diium bis(nitrate). Solid State Sci. 2020, 106, 106326 10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2020.106326. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Puyo M.; Lebon E.; Vendier L.; Kahn M. L.; Fau P.; Fajerwerg K.; Lepetit C. Topological Analysis of Ag–Ag and Ag–N Interactions in Silver Amidinate Precursor Complexes of Silver Nanoparticles. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 4328–4339. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b03166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey S.; Velmurugan G.; Rajaraman G. How important is the coordinating atom in controlling magnetic anisotropy in uranium(iii) single-ion magnets? A theoretical perspective. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 8976–8988. 10.1039/C9DT01869G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson E. R.; Keinan S.; Mori-Sánchez P.; Contreras-García J.; Cohen A. J.; Yang W. Revealing Noncovalent Interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 6498–6506. 10.1021/ja100936w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras-García J.; Johnson E. R.; Keinan S.; Chaudret R.; Piquemal J.-P.; Beratan D. N.; Yang W. NCIPLOT: A Program for Plotting Noncovalent Interaction Regions. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011, 7, 625–632. 10.1021/ct100641a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan Q.; Yang J.; To W.-P.; Che C.-M. Strong metal–metal Pauli repulsion leads to repulsive metallophilicity in closed-shell d8 and d10 organometallic complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2021, 118, e2019265118 10.1073/pnas.2019265118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becke A. D.; Edgecombe K. E. A simple measure of electron localization in atomic and molecular systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1990, 92, 5397–5403. 10.1063/1.458517. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (acccessed 2022/06/29).

- Savin A. The electron localization function (ELF) and its relatives: interpretations and difficulties. THEOCHEM 2005, 727, 127–131. 10.1016/j.theochem.2005.02.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koumpouras K.; Larsson J. A. Distinguishing between chemical bonding and physical binding using electron localization function (ELF). J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2020, 32, 315502 10.1088/1361-648x/ab7fd8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmider H. L.; Becke A. D. Chemical content of the kinetic energy density. THEOCHEM 2000, 527, 51–61. 10.1016/S0166-1280(00)00477-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen H. Localized-orbital locator (LOL) profiles of chemical bonding. Can. J. Chem. 2008, 86, 695–702. 10.1139/v08-052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kender W. T.; Turro C. Unusually Slow Internal Conversion in N-Heterocyclic Carbene/Carbanion Cyclometallated Ru(II) Complexes: A Hammett Relationship. J. Phys. Chem. A 2019, 123, 2650–2660. 10.1021/acs.jpca.9b00858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mas-Marzá E.; Peris E.; Castro-Rodríguez I.; Meyer K. Synthesis and Catalytic Properties of Two Trinuclear Complexes of Rhodium and Iridium with the N-Heterocyclic Tris-carbene Ligand TIMENiPr. Organometallics 2005, 24, 3158–3162. 10.1021/om0501531. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dash C.; Shaikh M. M.; Ghosh P. Silver complexes of 1,2,4-triazole derived N-heterocyclic carbenes: Synthesis, structure and reactivity studies. J. Chem. Sci. 2011, 123, 97–106. 10.1007/s12039-011-0105-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paczal A.; Benyei A. C.; Kotschy A. Modular Synthesis of Heterocyclic Carbene Precursors. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 5969–5979. 10.1021/jo060594+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandys M.-C.; Jennings M. C.; Puddephatt R. J. Luminescent gold(I) macrocycles with diphosphine and 4,4′-bipyridyl ligands. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 2000, 4601–4606. 10.1039/B005251P. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A: Found. Crystallogr. 2008, 64, 112–122. 10.1107/S0108767307043930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.; Trucks G. W.; Schlegel H. B.; Scuseria G. E.; Robb M. A.; Cheeseman J. R.; Scalmani G.; Barone V; Mennucci B.; Petersson G. A.. et al. Gaussian 09, revision A.1; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2009.

- Becke A. D. Density-functional exchange-energy approximation with correct asymptotic behavior. Phys. Rev. A 1988, 38, 3098–3100. 10.1103/PhysRevA.38.3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigend F.; Ahlrichs R. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297–3305. 10.1039/B508541A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiher M. Douglas–Kroll–Hess Theory: a relativistic electrons-only theory for chemistry. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2006, 116, 241–252. 10.1007/s00214-005-0003-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reed A. E.; Curtiss L. A.; Weinhold F. Intermolecular interactions from a natural bond orbital, donor-acceptor viewpoint. Chem. Rev. 1988, 88, 899–926. 10.1021/cr00088a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bader R. F. W. Atoms in molecules. Acc. Chem. Res. 1985, 18, 9–15. 10.1021/ar00109a003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T.; Chen F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 580–592. 10.1002/jcc.22885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey W.; Dalke A.; Schulten K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graphics 1996, 14, 33–38. 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamo C.; Barone V. Toward reliable density functional methods without adjustable parameters: The PBE0 model. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 6158–6170. 10.1063/1.478522. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Velmurugan G.; Ramamoorthi B. K.; Venuvanalingam P. Are Re(i) phenanthroline complexes suitable candidates for OLEDs? Answers from DFT and TD-DFT investigations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 21157–21171. 10.1039/C4CP01135J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Velmurugan G.; Venuvanalingam P. Luminescent Re(i) terpyridine complexes for OLEDs: what does the DFT/TD-DFT probe reveal?. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 8529–8542. 10.1039/C4DT02917H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R. L. Natural transition orbitals. J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 118, 4775–4777. 10.1063/1.1558471. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.