Learning objectives.

By reading this article, you should be able to.

-

•

Explain how anticoagulation with heparin is achieved and monitored during cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB).

-

•

Discuss the mechanisms of heparin resistance and rebound.

-

•

Detail the important aspects of reversing the anticoagulant effects of heparin with protamine.

Key points.

-

•

Extracorporeal circulation requires adequate anticoagulation to prevent catastrophic clot formation within the oxygenator, circuit failure, or both.

-

•

Anticoagulation for CPB is usually achieved with heparin on a weight-based dose strategy.

-

•

The anticoagulant effect of heparin is monitored routinely using the activated clotting time in the operating theatre.

-

•

Heparin resistance can be managed with additional heparin, antithrombin supplementation or adjuvant anticoagulants.

-

•

Protamine, used to reverse heparin after CPB, has significant haemodynamic and haematological effects.

Extracorporeal circulation (ECC) is any process whereby the blood volume is circulated outside the body. Depending on the duration and extent of artificial surface exposure, systemic anticoagulation is required to offset contact activation of coagulation. A systemic inflammatory response that is modulated by the level of anticoagulation occurs both during and after ECC.1 Heparin has remained the primary mechanism of accomplishing anticoagulation since the advent of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) more than half a century ago but only recently has there been a move to standardise practice.2, 3, 4

This review comprises two parts. In the first part we use international guidelines on anticoagulation for CPB as a basis to summarise the current evidence surrounding the use of heparin and protamine. In the second paper we will address when alternatives are required, how they are given and the pathological states that influence anticoagulation.

Heparin

Anticoagulation

Heparin belongs to the glycosaminoglycan (GAG) family of molecules in which there are repeated disaccharide units of uronic acid residues (l-iduronic or d-glucoronic acid) and N-acetyl-d-glucosamine. Unfractionated heparin (UFH) is the least processed form of natural GAG and is derived from purified porcine intestinal tissue. Its molecular weight is 3–30 kDa.

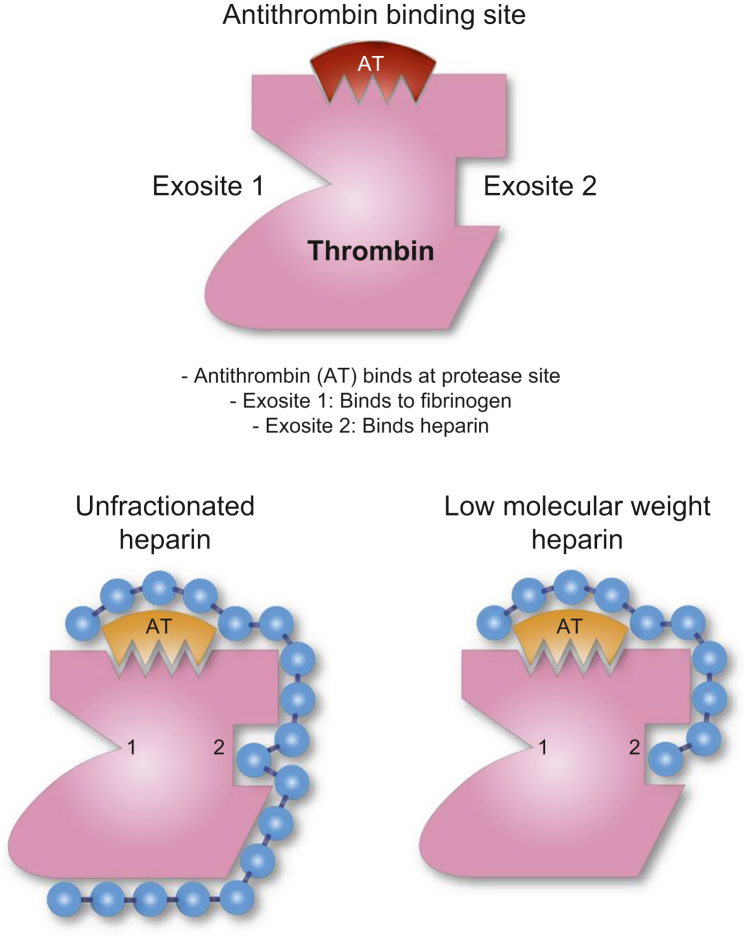

Unfractionated heparin containing the pentasaccharide sequence is responsible for its interaction with antithrombin (AT) on thrombin (Fig 1). Heparin is anionic and binds to the positive residues of the protease inhibitor AT. The result is a conformational change at the AT arginine reactive centre and an increase in the binding rapidity and activity of AT by up to 1000-fold. In addition, the arginine reactive centre on AT binds covalently to the active serine protease centre of thrombin (factor IIa), factor Xa and other serum proteases, thereby irreversibly inhibiting their pro-coagulant activity. Heparin molecules that maintain a pentasaccharide sequence have strong anticoagulant effects via binding with AT, facilitated by binding at exosite II. As access to exosite II is obstructed, heparin does not act on fibrin-bound thrombin, unlike direct thrombin inhibitors.5, 6

Fig. 1.

Interactions between thrombin, antithrombin and heparin. Thrombin (Factor IIa) exosite I: orientates fibrinogen binding and is important for platelet receptor (PAR) recognition; exosite II: binding site for heparin and fibrin, when fibrin is bound this blocks access for heparin. Antithrombin binds at the primary protease site.

Furthermore, fragments of any length with the pentasaccharide sequence also exert an anticoagulant effect by direct inhibition of factor Xa. At concentrations >4 IU ml−1, heparin can have anticoagulant effects independent of the pentasaccharide AT effect: there is inhibition of thrombin by the activation of the enzyme heparin cofactor II (HC II) and interaction with tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI).5

Owing to the heterogeneity of UFH, the binding and anticoagulant activity is broad and variable. Some heparin binds to plasma proteins that have adverse consequences such as osteopenia, and potentially immunoglobulins, as seen in heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.

Other effects

Heparin also has other pharmacodynamic effects in addition to anticoagulation such as hyperkalaemia, hypotension and different effects on platelets. Hyperkalaemia, mediated through an inhibition of aldosterone synthesis, is more common in patients with predisposition to hyperkalaemia, such as renal failure.

Hypotension can occur after a large dose of heparin. It is attributed to the release of histamine, cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) and endothelium-derived nitric oxide, as well as calcium inhibition. Infrequently this can be profound enough to require emergency institution of CPB.7

Heparin has been shown to reduce macroaggregate platelet formation, and increases the activation and consumption of platelets while on CPB. There are changes in platelet morphology by direct activity on the platelet surface, as well as altering fibrinogen binding and impaired platelet adhesion.8

Dose for CPB

Recent guidelines from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) and Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists (SCA) in 2018 have given recommendations on the dosing and monitoring of heparin for CPB.4 Key principles from this document are.

-

•

Before commencing CPB, there must be a demonstration of adequate anticoagulation, achieved through an activated clotting time (ACT).

-

•

Heparin doses for CPB commence at 300–400 IU kg−1 total body weight but individual response to heparin is heterogeneous.

-

•

Adequate anticoagulation is determined as an activated clotting time (ACT) >480 s.

There is significant molecular variability in UFH, and therefore, the dose–response relationship is complicated. Dosage based on weight has been shown to deliver variable ACTs between patients in observational studies.9 In a single-centre study, 6 of 100 patients who received heparin 300 IU kg−1, had an ACT <350 s.4

Alternative methods for calculating the initial dose of heparin are ex vivo heparin dose–response curves that compare the ACT with spiked UFH concentrations. The HepCon heparin dose response is based on spiking the patient's blood with two heparin concentrations, 1.7 IU and 2.84 IU ml−1, and assuming the dose–response relationship is linear. It then estimates the dose of heparin to achieve concentrations of 2 IU ml−1, which is between the two heparin concentrations. However, studies have demonstrated poor correlation of the calculated in vitro heparin dose–response curve compared with the actual patient heparin dose response.10

When redosing heparin, a two-compartmental model for heparin adequately models clearance pharmacodynamics. This model relies on the rapid saturation of heparin within the central compartment through the interaction with heparin binding proteins and the endothelial glycocalyx, followed by a slower first-order clearance mechanism, which is largely renal dependent. Thus, heparin dose response demonstrates non-linear kinetics such that with larger doses of the heparin, the response and duration of anticoagulation increase, for example after 25 IU kg−1 the terminal half-life is 30 min, after 100 IU kg−1 it is 60 min and after 400 IU kg−1 it is 150 min.

In addition, other factors alter dosing regimens of heparin, such as cooling, liver disease, renal dysfunction and other thrombotic disease states. The current guidelines advocate for multiple methods of redosing heparin, based on availability of assays, and clinical expertise in the absence of clear evidence. The technique in common use is routine redosing, seeking to avoid the variable disparity between measured heparin concentration and ACT that occurs with increasing duration of CPB because of haemodilution, hypothermia and changes in clotting factor concentrations.2,4

Routine redosing of UFH achieves higher ACT values; however, these patients often achieve high plasma concentrations of heparin >4 IU ml−1, which may be associated with increased bleeding complications postoperatively. The proposed strategy for redosing in the STS guidelines is: one third of the initial heparin bolus at 90 min after the start of CPB, followed by repeat doses every 60 min thereafter. Consideration of renal function and thereby renal clearance should be made with repeat dosing.4

Monitoring of anticoagulation

The ACT is considered the ‘standard of care’ for assessment of anticoagulation on bypass simply because of the available data and safety profile established from its use over several decades.4 Activated clotting time measurement was initially derived by placing whole blood into a glass tube containing celite, mixed manually and heated until clotting occurred, and was timed by ‘eyeballing’ the duration until visible clot formed. This method was used to determine the ‘safety zone’ of anticoagulation during CPB as between 300 and 600 s, in the early days of CPB.11

There are various types of ACT machines, but the principle remains the same. Fresh blood is added to a tube that contains a surface activator high in silicate, either celite or kaolin. Contact with this material in the presence of endogenous phospholipid (as present on platelets) and calcium results in activation of the contact pathway of coagulation. The conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin, by the activity of thrombin is detected mechanically, or through an electrogenic assay.11 Fundamentally, the ratio of activators to heparin concentration in an ACT test will determine the response curve. In the clinical context of an ACT for safe anticoagulation during CPB, the heparin concentration and ACT maintain an approximately linear relationship. All tests work with different methodologies (amount/type of activator); the results cannot be used interchangeably, although studies investigating celite vs kaolin activators found no significant clinical differences in heparin dose or repeat dosing. Celite ACT cartridges are not recommended for patients receiving aprotinin, as prolongation of clotting times caused by celite–aprotinin binding, factor XI interaction and the difference in charge between celite and kaolin is variable.12

When UFH is used at lower therapeutic concentrations, the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) has stronger correlation with plasma concentrations than ACT. However, at serum concentrations of UFH of >1 IU ml−1, the aPTT is inaccurate and at concentrations for CPB (2–4 IU ml−1), the aPTT requires sample dilution and is therefore not practical for measuring anticoagulation for CPB.13

Anti-Xa concentrations quantify the inhibitory effect of AT on factor Xa, and are used to estimate UFH concentration, and low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) and anti-Xa drugs such as apixaban. However, anti-Xa assays are not point-of-care tests and measuring of anti-Xa is impractical because of the delay in obtaining test results, typically 30 min. At present, there is no evidence of improved safety for patients managed with anti-Xa measurement and their use is restricted to specific indications.14

Heparin resistance

Heparin resistance (HR) is defined as the inability to achieve adequate anticoagulation with an ACT >480 s using an appropriate dose of heparin (300–400 U kg−1). There are various causes such as antithrombin deficiency, mechanisms independent of antithrombin and pseudo resistance.

AT deficiency

A normal AT concentration is typically 80–120% (units per 100 ml plasma) using a functional assay, with deficiency usually defined as <80%.

Treatment with heparin before CPB results in a lower AT. Furthermore, CPB and the cohort of patients having cardiac surgery, have reduced AT concentrations with endothelial dysfunction and other pathophysiological changes that alter coagulation. During CPB, AT activity can decrease up to 40–50% below preoperative values, and low AT concentrations after CPB are associated with a prolonged duration of ICU stay, and increased incidences of thromboembolic events and surgical complications.15

Antithrombin activity less than 60% increases the likelihood of HR. This can be acquired, related to decreased production in patients with liver disease, or from increased clearance. Antithrombin clearance is increased with preoperative use of heparin, nephrotic syndrome, sepsis and in the setting of mechanical devices such as ventricular assist devices and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). Increased clearance because of preoperative heparin use, results in a decline in AT activity of up to 5–7% per day achieved through AT/thrombin complex clearance via the reticuloendothelial system.15

Congenital AT deficiency is a rare, autosomal dominant disorder, with an incidence of 1:3000–5000 and is attributable to a deficiency in the SERPINC1 gene. Patients have AT concentrations 40–60% of normal. Inherited AT deficiency is associated with thrombophilia, and usually presents with prothrombotic sequelae. These patients are usually under the management of a haematologist.15

AT-independent mechanisms

Heparin is a large negatively charged GAG molecule that binds not only to AT but also to chemokines, growth factors, positively charged extracellular proteins in the endothelial glycocalyx and platelets. The result is reduced bioavailability of heparin through an increase in the volume of distribution. In states of increased proportions of extracellular positive proteins, such as infective endocarditis and sepsis, there is a reduction in the effective concentration of heparin anticoagulation. This effect is proportional to the heparin dose, that is [Heparin] + [Heparin binding proteins and surfaces] ⇌ [Bound heparin].16

Thrombocytosis also increases the likelihood of HR, particularly with platelet counts >300,000 cells mm−3. This can be from non-specific binding or by platelet activation with release of platelet factor 4 (PF4). Other poorly understood mechanisms include treatment with i.v. nitroglycerin or oestrogen.15

Pseudo resistance

Acute phase reactants are associated with endothelial dysfunction and are frequently elevated in cardiovascular disease. Increased factor VIII activity and fibrinogen have been shown to be associated with HR with normal AT concentrations. In this circumstance, the ACT or aPTT will be relatively low whereas the anti-Xa heparin concentration, not influenced by acute phase reactants, will demonstrate the expected result.17

Whether this is in vitro Pseudo resistance or true in vivo resistance is debatable, but an alternative to heparin anticoagulation could be considered to avoid heparin overdose.

Management of acquired HR

In the setting of HR, the STS guidelines advocate to give repeated doses of heparin, or consider the use of AT supplementation.4

The therapeutic options are additional heparin, AT supplementation and use of an adjuvant anticoagulant.

Additional heparin

Heparin resistance is commonly overcome with additional doses of heparin but there is a ceiling effect, which can occur at the upper end of the therapeutic range (i.e. 4 U ml−1). Case reports document failure to achieve an adequate ACT despite doses as high as 1200 U kg−1, necessitating AT supplementation.18 Issues with increasing the dose of heparin are platelet effects and heparin rebound, which are associated with bleeding after CPB.

Supplementing AT with fresh frozen plasma

Early studies and case reports identified fresh frozen plasma (FFP) as a potential management strategy for HR.15 Fresh frozen plasma typically contains approximately 1 IU ml−1 (varying between 0.3 and 1.5 IU ml−1) of AT to potentiate the anticoagulant effect of heparin. Thus, 2 units of FPP will usually contain 500 U of AT but may contain between 150 and 750 U. Allogeneic blood transfusion, however, carries the risk of volume overload, haemodilution, lung injury and immune modulation.18

Supplementing AT with AT concentrate

More evidence exists for the use of synthetic AT. Previously available as recombinant AT (Atryn), this product has been withdrawn in 2015, and fractionated human plasma derived AT, for example Anbinex or Thrombotrol-VF, 1000 U per vial is used.

Compared with additional heparin doses, a single dose of AT more frequently achieves an ACT >480 than FFP; however, the dose of AT described varies from 500 up to 5000 IU. Most commonly a single dose of 1000 U (1 ampoule) is used. As the half-life ranges from 2 to 4 days, repeat dosing is not required. Alternatively, a dose of (100-AT activity)×(weight [kg]×0.8) if the AT activity is known, has been used to target 100% activity.19

In a study by Ranucci and colleagues,19 patients with normal AT concentrations before surgery were given AT to achieve values of 120% normal. The outcomes in the intervention group showed higher numbers of patients with postoperative AT concentrations >80%, with lower doses of heparin and protamine required and fewer instances of HR. There were no significant differences in chest tube drainage at 24 h, duration of ICU stay or surgical complications.19

Adjuvant anticoagulants

Single case reports (and our institutional experience) describe the use of low dose bivalirudin to prolong the ACT. Boluses of 0.1 mg kg−1 are given by titration, and an infusion at 0.1–0.2 mg kg−1 h−1 can also be considered. The advantages are faster offset of bivalirudin combined with the ability to reverse heparin anticoagulation, whilst avoiding heparin overdose and an alternative anticoagulation mechanism in the event of inadequate ACT despite AT supplementation.20

Heparin rebound

The detection of residual heparin in the blood after reversal with protamine occurs either from incorrect protamine dosing, or mismatching protamine and heparin clearance rates. This is compounded by heparin sequestration in fat stores and binding to plasma proteins, which redistributes after protamine neutralisation.21

Doses >400 IU kg−1 of heparin to establish anticoagulation results in 10–15% of patients having detectable heparin concentrations up to 2 h after surgery, and an anti-Xa effect 6 h postoperatively. However, currently there is no evidence that this is associated with increased transfusion rates. The SCA guidelines state a continuous low-dose protamine infusion (25 mg h−1) over 6 h reduces the risk of heparin rebound and drain outputs.4

Protamine

Pharmacology

Protamine reverses the anticoagulation effect of heparin through the formation of an ionic bond, that is anionic heparin, with the cationic protamine. This new complex impairs heparin binding to AT, and causes heparin bound to AT to dissociate, thus allowing AT function to return to normal. The neutralisation of heparin by protamine is amplified by the activity of PF4. Platelet factor 4 is released by platelets that are activated during CPB and acts to stabilise the heparin–protamine salt.22 The protamine–heparin complex is cleared via the reticuloendothelial system. The elimination half-life is 7.4 min, and so and the majority of protamine is eliminated from the body after 15 min.

Haemodynamic effects

Protamine has a range of unwanted effects that vary in severity and morbidity. The rate of adverse effects is documented between 0.1% and 13% and comprise hypotension, pulmonary hypertension and anaphylaxis. Most severe reactions occur within the first 10 min of injection.22 Independent risk factors for protamine reaction are use of protamine-containing insulin, previous protamine reaction, allergy to protamine or fish, and any history of non-protamine drug allergy.22

Hypotension is the most common haemodynamic effect and varies in severity from minor instability to cardiovascular collapse. It is defined as SBP <100 mmHg or a reduction of MAP >10 mmHg. It has been found to be an independent risk factor for in-hospital mortality after coronary grafting in retrospective studies.23 The precise mechanism for how protamine reduces systemic vascular resistance is unknown. Rapid infusion of protamine, producing a higher plasma concentration, increases the risk of developing hypotension. In vitro studies have found a protamine interaction with endothelial nitric oxide/cGMP function as a potential mechanism.22

Protamine-induced pulmonary hypertension (PIPH) with an incidence of 0.6% is a potentially catastrophic reaction to protamine thought to be mediated by thromboxane A2 release and perioperative continuation of aspirin may decrease the risk. Protamine-induced pulmonary hypertension is defined as an abrupt increase in PA pressure >7 mmHg or right ventricular (RV) dysfunction with SBP <90 mmHg within the first 3–5 min after administration of protamine.24 Management of PIPH includes cessation of protamine, RV supportive measures that reduce further increases in pulmonary vascular resistance and pulmonary arterial dilators, such as inhaled nitric oxide or prostacyclin (PGI2). In severe or refractory cases, institution of CPB may be indicated.

Anaphylaxis associated with protamine has an incidence of 0.19%. Both immunoglobulin E (IgE)- and IgG-mediated anaphylaxis have been described. Severity and incidence are linked to the presence of protamine-specific antibodies.25

Haemodynamic collapse during anaphylaxis is associated with previous protamine exposure, previous drug or protamine allergy, and fish allergy. The most common factor predisposing patients to anaphylaxis is prior treatment with neutral protamine hagedorn (NPH) insulin.4 Moreover, there are multiple case reports of patients having anaphylactoid, or non-immune anaphylaxis, thought to result from complement activation.25 Heparin–protamine complexes are known to activate the classic complement pathway causing degranulation of basophils and mast cells via C3a and C5a. Vasogenic molecules such as interleukin (IL)-1 can also be released.26

Effects on coagulation

Protamine has independent effects on haemostasis through an action on platelets, coagulation factors and on fibrinolysis.22 The deleterious effect of protamine on platelets is dose dependent and occurs both independently and in the presence of heparin. Independently, protamine causes an immune response that activates platelets resulting in a consumptive thrombocytopenia. Protamine also reduces platelet aggregation and adhesion by reduction of thrombin sensitivity, inhibition of glycoprotein 1b–vWF interaction at high doses and inhibition of platelet–collagen adhesion.

In the presence of heparin, protamine reduces platelet aggregation by up to 50% especially when protamine/heparin ratios are greater than 1:1 (i.e. 1 mg for every 100 U). In addition, a reduction in ADP induced platelet aggregation occurs as the protamine/heparin ratio increases above 1.3:1.22 Protamine also exerts effects on coagulation factors producing downregulation of thrombin in a dose-dependent fashion when ratios exceed 1.3:1, increasing exponentially from 2.6:1, which results in decreased fibrin formation and thrombin-dependent platelet activation. Reduction in activation of factor V by IIa and Xa, together with a decrease in factor VII activation by tissue factor manifests as prolonged clotting times on the ACT and point-of-care assays, such as the rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) InTEM test. This can be overcome by addition of platelets or by increasing the concentrations of VIII or von Willebrand factor (vWF), such as with desmopressin.22

Finally, protamine enhances fibrinolysis and reduces clot strength by sequestration of fibrinogen and enhanced activation of t-PA mediated clot breakdown. This effect is counteracted by the addition of tissue factor to plasma and the use of anti-fibrinolytics is theorised to reduce protamine induced fibrinolysis.27

Dose

Successful anticoagulation for bypass requires reversal of anticoagulation both at the conclusion of CPB and throughout the postoperative course. Insufficient reversal doses are known to increase postoperative bleeding; however, high doses of protamine have also been associated with increased postoperative bleeding.28

Regimens based on initial heparin dose result in increased clotting times and microvascular bleeding compared with protamine based on measured heparin concentration and protamine/heparin ratios >1.3 are associated with increased postoperative bleeding compared with 0.8, without affecting ACT or heparin rebound.4 Furthermore, a 0.6 protamine/heparin ratio may be better than a 0.8 ratio. At the lower dose, a protamine/heparin ratio <0.6 is associated with increased blood loss within 12 h postoperatively.29

The dosing strategy by the STS/SCA makes the following Class IIa recommendations.

-

•

The reversal dose should be based on a titration to existing heparin.

-

•

Protamine doses should not exceed 2.6:1 (protamine/heparin) ratio, as doses in excess are associated with increased bleeding risk, platelet dysfunction and prolonged ACT.

and Class IIb recommendation:

-

•

Low-dose protamine infusion (25 mg h−1) for as long as 6 h reduces the risk of heparin rebound.

The guidelines from the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery and the European Association of Cardiothoracic Anaesthesiology (EACTS/EACTA) recommend a lower total dose and make the following points.

-

•

Ideally, protamine dose should match the actual heparin concentration after termination of ECC.

-

•

It is advised that protamine dose should not exceed a 1:1 ratio to the initial heparin bolus.

Determining residual heparin concentration for protamine dosing

Both the STS/SCA and EACTS/EACTA guidelines recommend giving protamine according to the existing heparin concentration. Decreased protamine/heparin ratios are associated with improved haemostatic measurements on viscoelastic assays such as the ROTEM and reduce the incidence of severe blood loss, compared with a fixed protamine/heparin ratio of 1:1.30 Three methods are in current use for determining the residual heparin concentration: protamine titration, tests involving heparinase and calculations based on ACT.

Protamine titration can be performed both in vitro via a point-of-care (POC) testing device such as the Medtronic HMS Plus HepCon or in vivo using a similar methodology.31 With the HepCon, the user selects one of 11 available cartridges that contain four or six ACT channels with increasing protamine concentrations designed to neutralise heparin between concentrations of 0–6.0 mg kg−1. A single cartridge that reflects an institution's heparin practice is selected, such as the gold cartridge designed for concentrations between 1.5 and 4.0 mg kg−1. A calculation based on the nadir ACT value and estimated blood volume enables derivation of the protamine dose. There is limited clinical evidence of benefit using Hepcon rather than ACT for reversing heparin.32 Alternatively, as an in vivo technique, protamine can be given at a ratio of 0.6:1 to the initial dose of heparin, and repeated incremental protamine doses can be given either as boluses or an infusion against a measure of residual heparin.22

Viscoelastic POC haemostasis devices contain a mechanism to compare the time to initiation of clot, with and without the addition of heparinase. Heparinase from Flavobacterium heparinum is an enzyme that neutralises heparin. In addition, some ACT devices can compare clotting times in a similar fashion, such as the Medtronic HMSTM ACT.33

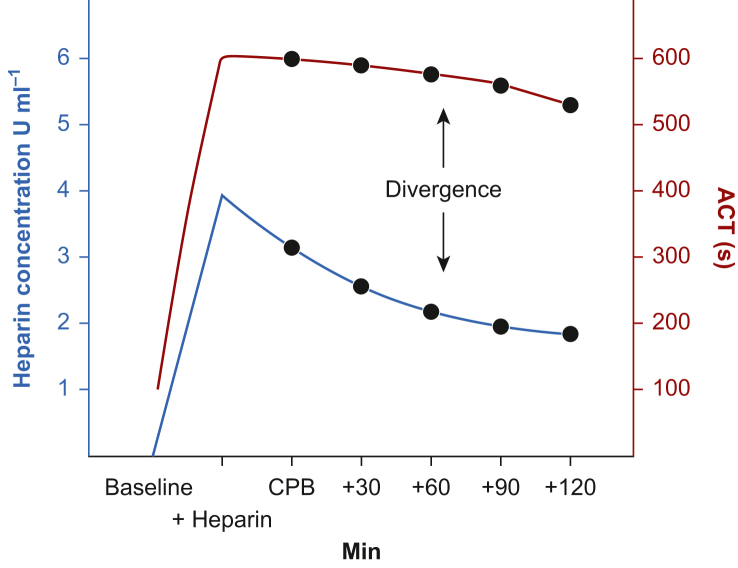

Simple ACT measurement-based calculations are the least accurate method of detecting residual heparin effect as the relationship between ACT and heparin concentration diverges with increasing time of CPB (Fig 2). Thus, novel calculations of protamine dose based on multi-compartment pharmacokinetic modelling corrected for ideal body weight have been proposed. One such calculation is PRODOSE, which when compared with a fixed protamine/heparin ratio of 1:1, resulted in an average reduction of 36% total protamine dose being given. This produced a reduction of 1.5 min on the kaolin TEG r-time, the primary outcome. However, there were no differences in secondary outcomes such as red cell transfusion rates, drainage volume, or the ACT after reversal with protamine.34

Fig. 2.

An example of divergence between heparin concentration and measured ACT. ACT, activated clotting time; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass.

Protamine after reinfusion of pump blood after CPB

It is common practice to give an additional dose of protamine with reinfusion of pump blood. However, given the amount of heparin, it is debatable whether this extra dose is required, especially as the common trigger for this is a change in a standard ACT which is known to be insensitive to residual heparin.

Using a two-compartment model with a typical bypass run of more than 60 min in which heparin has not been redosed, the heparin concentration should approximately be half. Assuming a standard dose of heparin of 300–400 U kg−1 and a concentration of 2 IU ml−1, there will be approximately 2000 U of heparin per 1000 ml. Protamine 20 mg would reverse the residual heparin, such as contained in a protamine infusion at 25 mg h−1, as recommended by the STS/SCA.4,22

Conclusions

In the absence of pathological states, heparin anticoagulation followed by reversal with protamine remains the most common method of achieving anticoagulation for CPB. Before commencing CPB, heparin 300–400 IU kg−1 should achieve an ACT >480 s. In the presence of HR, a single dose of AT more frequently achieves an ACT >480 s than FFP. To reduce heparin rebound after CPB, protamine 25 mg h−1 over 6 h can be given. The dose of protamine should be based on a titration to existing heparin concentration: it should not exceed a 1 mg:100 U ratio to the initial heparin bolus.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Biographies

Bruce Cartwright MBBS, FANZCA is a consultant cardiothoracic anaesthetist at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital and St Vincent's Hospital, Sydney. He is an examiner for the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (ANZCA) fellowship and clinical lecturer at the University of Sydney.

Nicholas Mundell MBBS, FANZCA is a consultant anaesthetist at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital.

Matrix codes: 1A02, 2A04, 3G00

MCQs

The associated MCQs (to support CME/CPD activity) will be accessible at www.bjaed.org/cme/home by subscribers to BJA Education.

References

- 1.Ranucci M., Balduini A., Ditta A., Boncilli A., Brozzi S. A systematic review of biocompatible cardiopulmonary bypass circuits and clinical outcome. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:1311–1319. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.09.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunning J., Versteegh M., Fabbri A., et al. Guideline on antiplatelet and anticoagulation management in cardiac surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;34:73–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wahba A., Milojevic M., Boer C., et al. EACTS/EACTA/EBCP guidelines on cardiopulmonary bypass in adult cardiac surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2019;57:210–251. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezz267. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shore-Lesserson L., Baker R.A., Ferraris V.A., et al. The society of thoracic Surgeons, the society of cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, and the American society of ExtraCorporeal technology: clinical practice guidelines — anticoagulation during cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;105:650–662. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2017.09.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garcia D.A., Baglin T.P., Weitz J.I., Samama M.M. Parenteral anticoagulants: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e24S–43S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oduah E.I., Linhardt R.J., Sharfstein S.T. Heparin: past, present, and future. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2016;9:38. doi: 10.3390/ph9030038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kotoda M., Ishiyama T., Nakajima H., Matsukawa T. Prediction of heparin induced hypotension during cardiothoracic surgery: a retrospective observational study. Anaesth Pain Intensive Care. 2019:145–150. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao C., Boylan B., Fang J., Wilcox D.A., Newman D.K., Newman P.J. Heparin promotes platelet responsiveness by potentiating αIIbβ3-mediated outside-in signaling. Blood. 2011;117:4946–4952. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-307751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garvin S., FitzGerald D.C., Despotis G., Shekar P., Body S.C. Heparin concentration–based anticoagulation for cardiac surgery fails to reliably predict heparin bolus dose requirements. Anesth Analg. 2010;111:849–855. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181b79d09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gausman J.N., Marlar R.A. Inaccuracy of a “spiked curve” for monitoring unfractionated heparin therapy. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;135:870–876. doi: 10.1309/AJCP60ZGXCJKRMJO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Falter F., MacDonald S., Matthews C., Kemna E., Cañameres J., Besser M. Evaluation of point-of-care ACT coagulometers and anti-Xa activity during cardiopulmonary bypass. J Cardiothor Vasc Anesth. 2020;34:2921–2927. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2020.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vries A.J.D., Lansink-Hartgring A.O., Fernhout F.-J., Huet R.C.G., Heuvel ER van den. The activated clotting time in cardiac surgery: should Celite or kaolin be used? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2017;24:549–554. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivw435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monagle P. Humana Press; New York: 2013. Haemostasis, methods and protocols. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bolliger D., Maurer M., Tanaka K. Toward optimal anticoagulation monitoring during cardiopulmonary bypass: it is still a tough “ACT”. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2020;34:2928–2930. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2020.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finley A., Greenberg C. Heparin sensitivity and resistance. Anesth Analg. 2013;116:1210–1222. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31827e4e62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levy J.H., Connors J.M. Heparin resistance — clinical perspectives and management strategies. New Engl J Med. 2021;385:826–832. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra2104091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thota R., Ganti A.K., Subbiah S. Apparent heparin resistance in a patient with infective endocarditis secondary to elevated factor VIII levels. J Thromb Thrombolys. 2012;34:132–134. doi: 10.1007/s11239-012-0692-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spiess B.D. Treating heparin resistance with antithrombin or fresh frozen plasma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85:2153–2160. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ranucci M., Baryshnikova E., Crapelli G.B., Woodward M.K., Paez A., Pelissero G. Preoperative antithrombin supplementation in cardiac surgery: a randomized controlled trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;145:1393–1399. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.09.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McNair E., Marcoux J.-A., Bally C., Gamble J., Thomson D. Bivalirudin as an adjunctive anticoagulant to heparin in the treatment of heparin resistance during cardiopulmonary bypass-assisted cardiac surgery. Perfusion. 2016;31:189–199. doi: 10.1177/0267659115583525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ichikawa J., Kodaka M., Nishiyama K., Hirasaki Y., Ozaki M., Komori M. Reappearance of circulating heparin in whole blood heparin concentration-based management does not correlate with postoperative bleeding after cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2014;28:1003–1007. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boer C., Meesters M.I., Veerhoek D., Vonk A.B.A. Anticoagulant and side-effects of protamine in cardiac surgery: a narrative review. Br J Anaesth. 2018;120:914–927. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2018.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kimmel S.E., Sekeres M., Berlin J.A., Ellison N. Mortality and adverse events after protamine administration in patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:1402. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200206000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Comunale M.E., Maslow A., Robertson L.K., Haering J.M., Mashikian J.S., Lowenstein E. Effect of site of venous protamine administration, previously alleged risk factors, and preoperative use of aspirin on acute protamine-induced pulmonary vasoconstriction. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2003;17:309–313. doi: 10.1016/s1053-0770(03)00055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nybo M., Madsen J.S. Serious anaphylactic reactions due to protamine sulfate: a systematic literature review. Basic Clin Pharmacol. 2008;103:192–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2008.00274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Welsby I.J., Newman M.F., Phillips-Bute B., Messier R.H., Kakkis E.D., Stafford-Smith M. Hemodynamic changes after protamine administration. Anesthesiology. 2005;102:308–314. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200502000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nielsen V.G. Protamine enhances fibrinolysis by decreasing clot strength: role of tissue factor-initiated thrombin generation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:1720–1727. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J. Blood loss after cardiopulmonary bypass, standard vs titrated protamine: a meta-analysis. Neth J Med. 2013;71:123–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goedhart A.L.M., Gerritse B.M., Rettig T.C.D., et al. A 0.6-protamine/heparin ratio in cardiac surgery is associated with decreased transfusion of blood products. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac. 2020;31:391–397. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivaa109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vonk A.B.A., Veerhoek D., Brom CE van den, Barneveld LJM van, Boer C. Individualized heparin and protamine management improves rotational thromboelastometric parameters and postoperative hemostasis in valve surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2014;28:235–241. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2013.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lax M., Pesonen E., Hiippala S., Schramko A., Lassila R., Raivio P. Heparin dose and point-of-care measurements of hemostasis in cardiac surgery—results of a randomized controlled trial. J Cardiothor Vasc Anesth. 2020;34:2362–2368. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2019.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aziz K.A.A., Masood O., Hoschtitzky J.A., Ronald A. Does use of the Hepcon® point-of-care coagulation monitor to optimise heparin and protamine dosage for cardiopulmonary bypass decrease bleeding and blood and blood product requirements in adult patients undergoing cardiac surgery? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2006;5:469–482. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2006.133785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wand S., Heise D., Hillmann N., et al. Is there a “blind spot” in point-of-care testing for residual heparin after cardiopulmonary bypass? A prospective, observational cohort study. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2020;26 doi: 10.1177/1076029620946843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miles L.F., Burt C., Arrowsmith J., et al. Optimal protamine dosing after cardiopulmonary bypass: the PRODOSE adaptive randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2021;18 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]