Abstract

Intracellular Ca2+ signals are temporally controlled and spatially restricted. Signaling occurs adjacent to sites of Ca2+ entry and/or release, where Ca2+-dependent effectors and their substrates co-localize to form signaling microdomains. Here we review signaling by calcineurin, the Ca2+/calmodulin regulated protein phosphatase and target of immunosuppressant drugs, Cyclosporin A and FK506. Although well known for its activation of the adaptive immune response via NFAT dephosphorylation, systematic mapping of human calcineurin substrates and regulators reveals unexpected roles for this versatile phosphatase throughout the cell. We discuss calcineurin function, with an emphasis on where signaling occurs and mechanisms that target calcineurin and its substrates to signaling microdomains, especially binding of cognate short linear peptide motifs (SLiMs). Calcineurin is ubiquitously expressed and regulates events at the plasma membrane, other intracellular membranes, mitochondria, the nuclear pore complex and centrosomes/cilia. Based on our expanding knowledge of localized CN actions, we describe a cellular atlas of Ca2+/calcineurin signaling.

Keywords: Calcium, Calcineurin, Phosphatase, Signaling, SLiMs, phosphorylation

1. Calcium signaling is temporally and spatially regulated

Calcium, Ca2+, is a universal messenger that regulates cell functions throughout the life of an organism, from fertilization to differentiation and from survival to aging and death. Intracellular Ca2+ concentrations are highly regulated and range from ~100 nM at basal, resting conditions to 0.5–1 μM in localized microdomains during signaling [1]. Dynamic changes in Ca2+ concentration control essential cell processes such as proliferation, secretion, migration metabolism, gene expression, and even apoptosis. But how do cells translate one message into such diverse responses? The answer lies in the complexity of the message, whose duration, amplitude, oscillatory frequency, and source all encode specific instructions [2]. In brief, cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations can increase via 1) entry of external Ca2+ through ion channels or exchangers at the plasma membrane (PM), 2) exit of Ca2+ from internal sources, i.e. mitochondria, the endo-lysosomal system, Golgi, nuclear envelope and especially the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), through Ca2+ release channels [3], or 3) a combination of both mechanisms, which influence each other through both positive and negative feedback loops that finely tune the temporal and spatial properties of the signal [2]. Similarly, an extensive network of Ca2+ pumps, exchangers and buffering proteins ensure that cytosolic Ca2+ increases are transient and highly localized by rapidly removing Ca2+ ions from the cytoplasm and either expelling it or sequestering it within organelles [4, 5]. These elaborate Ca2+ dynamics can be locally monitored in real time thanks to a large tool-box of genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators that can be targeted to different cellular compartments and tuned to detect a wide range of Ca2+ concentrations [6]. Similarly, Ca2+-sequestering proteins such as calbindin can be targeted to locally perturb these signals (as shown in [7, 8]).

Because Ca2+ ions are spatially restricted, Ca2+ effectors as well as their regulators and substrates cluster into signaling microdomains through interactions with Ca2+-conducting proteins. Ca2+ ions bind directly to a wide variety of proteins that participate in signaling. Some of these modulate the Ca2+ signal itself, i.e. pumps, channels and buffering/sequestering proteins, while other Ca2+-binding proteins control downstream cellular processes, i.e. kinases and other enzymes, cytoskeletal proteins and transcription factors [1]. Calmodulin (CaM), a highly conserved protein that contains four Ca2+-binding motifs called EF hands, is a key intracellular Ca2+ receptor that, once bound to Ca2+ regulates a host of proteins including Ca2+ channels and pumps as well as structural proteins and enzymes [9]. Ca2+-bound CaM regulates phosphorylation by activating a variety of protein kinases [10] and a single conserved protein phosphatase, called calcineurin (CN), also known as PP2B or PPP3, which is the focus of this review.

2. Calcineurin, the Ca2+/calmodulin-regulated protein phosphatase

Calcineurin was first isolated as the most abundant Ca2+/CaM binding protein in the brain [11] and was soon determined to be ubiquitously expressed and to function as a protein phosphatase [12]. Notably, as the only phosphatase regulated by Ca2+ and Ca2+-bound CaM, CN effects Ca2+ signaling in eukaryotes ranging from fungi to mammals but excluding plants. In yeast, CN regulates environmental stress responses and is required for pathogenesis [13]. In mammals, CN has well-established roles in the cardiovascular, nervous, and immune systems. Humans that are heterozygous for loss of function mutations in CN display epilepsy, developmental delay, and autism spectrum disorder, while mutations that lead to increased CN activity cause movement and craniofacial disorders as well as seizures [14, 15]. CN’s most highly studied function is to dephosphorylate the Nuclear Factor of Activated T-cells (NFAT) family of transcription factors, causing them to translocate to the nucleus where they activate gene expression [16]. In T-cells, NFAT activation initiates the adaptive immune response. Thus, the CN inhibitors, FK506 and cyclosporin A (CsA) have been used clinically as immunosuppressants for 40 years, and are routinely prescribed to solid organ transplant recipients to prevent organ rejection and for autoimmune disorders such as atopic dermatitis and psoriasis [17]. However, by reducing CN function in non-immune tissues these drugs also cause wide-ranging adverse effects, including diabetes, hypertension, hypomagnesemia, seizures, pain and increased hair growth [18, 19]. Most of these complications occur via unknown etiologies, highlighting the importance of elucidating tissue and disease-specific roles for CN and discovering fundamental knowledge of the signaling pathways that are regulated by this phosphatase.

2.1. CN structure, isoforms and activation

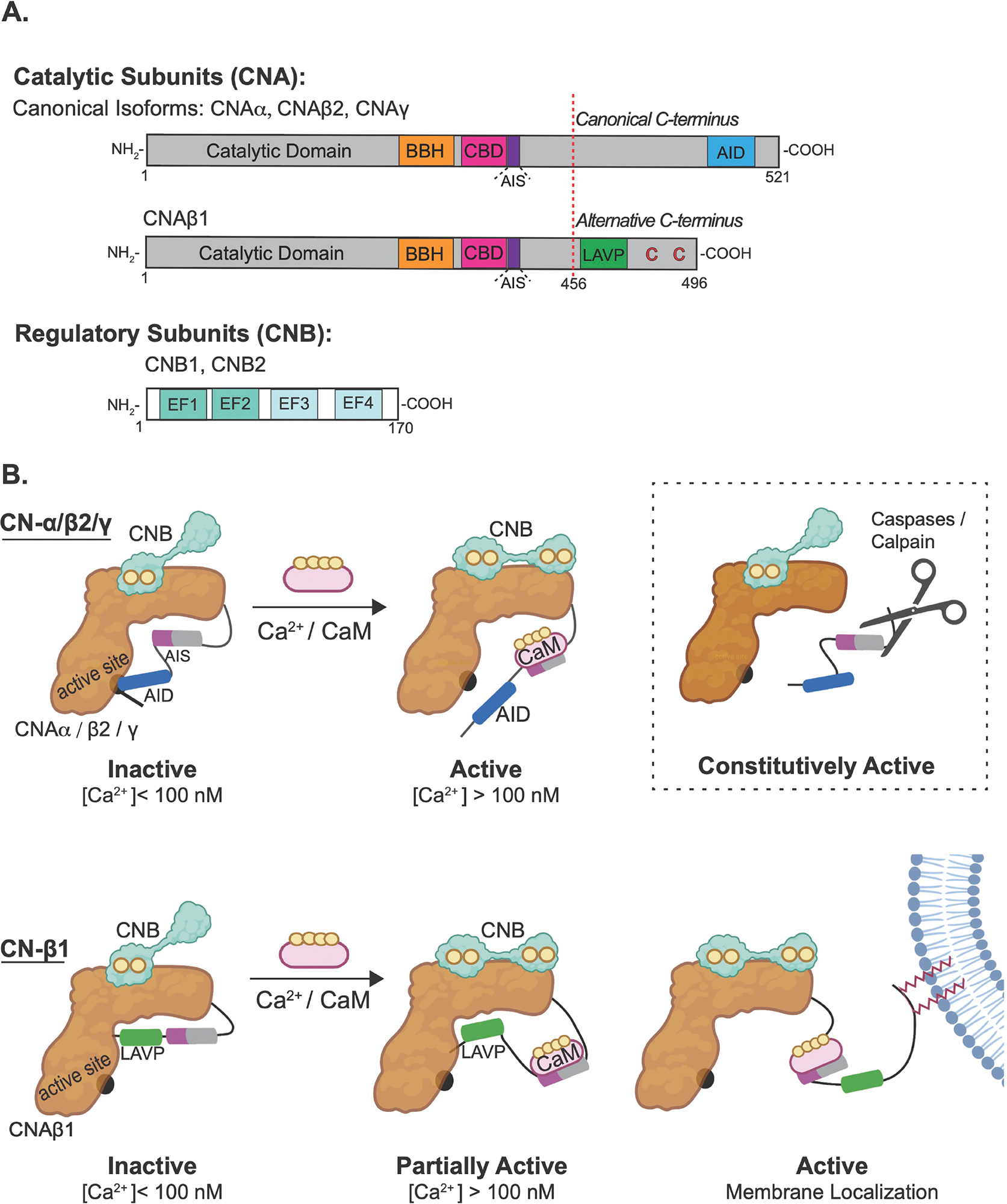

Calcineurin is an obligate heterodimer that is always composed of one catalytic subunit, CNA, complexed with a dedicated regulatory subunit, CNB. In this regard, CN differs from related PPP phosphatases such as PP1 and PP2A whose arsenal of regulator subunits give rise to a large number of isozymes with distinct properties [20]. In humans, the CNA subunit is encoded by three genes: PPP3CA (CNAα), PPP3CB (gives rise to CNAβ1 and CNAβ2) and PPP3CC (CNAγ), which show tissue-specific expression. Of these α, β2 and γ are canonical isoforms that diverge somewhat at their amino and carboxyl termini, but overall display a highly homologous domain architecture (Figure 1A): CNA contains a catalytic domain with an active site that coordinates two dinuclear (Zn2+ and Fe3+) metal ions, followed by a CNB-binding helix, an autoinhibitory sequence (AIS) which blocks an essential substrate recognition site for LxVP motifs (see section 2.3) [21], a CaM-binding domain which tightly binds one molecule of Ca2+-bound CaM (in low picomolar range), and a C-terminal autoinhibitory domain (AID) which blocks the active site under resting conditions ([Ca2+] ≤ 100 nM) [22, 23]. The small regulatory CNB subunit, encoded by PPP3R1 and PPP3R2, contains two pairs of Ca2+ binding EF-hands; one with high affinity (KD in nanomolar range) that constitutively binds Ca2+, and the other with a significantly lower Ca2+ affinity (10–50 μM) that serves as a calcium sensor [24–26] (Figure 1A). CN activation occurs when intracellular [Ca2+] rises, and maximal Ca2+ occupancy of CNB induces conformational changes in CNA that promote Ca2+/CaM binding, which causes autoinhibition by the AIS and the AID to be disrupted (Figure 1B) [21, 27]. Thus Ca2+ binding to CNB and Ca2+/CaM binding to CNA both contribute to Ca2+-dependent regulation of CN. CN activation is generally reversible, although under some pathophysiological conditions including Alzheimer’s Disease, cleavage of the C-terminal region removes the autoinhibitory domain and produces a constitutively active phosphatase (Figure 1B) [28, 29]. This highly conserved CN activation mechanism was also leveraged to develop genetically encoded, fluorescence resonance energy transfer-based reporters, CaNAR, CaNARi [30, 31] and DuoCaN /UniCaN [32] which measure spatio-temporal dynamics of CN activity in living cells. Such studies revealed that the level of Ca2+/CN activity is determined locally by the availability of free Ca2+/CaM. In vivo, CN activity is also modulated by endogenous protein regulators including Regulator of Calcineurin (RCAN1–3), Calcineurin Binding Protein-1 (CABIN/CAIN), and Calcineurin and Ras Binding protein (CARABIN), which will not be discussed here but were recently reviewed [33].

Fig. 1. Calcineurin domain structure and activation.

(A) Schematic of canonical (α, β2 and γ) and β1 catalytic subunit (CNA) and regulatory (CNB) subunits of calcineurin. CNB binding helix (BBH); calmodulin (CaM)-binding domains (CBD); autoinhibitory sequence (AIS); autoinhibitory domain (AID); EF-hand Ca2+ -binding sites (EF1 and EF2 are low-affinity, EF3 and EF4 are high affinity sites) are represented in the cartoons. (B) Cartoons of activation mechanisms for canonical (α, β2 and γ) and non-canonical calcineurin-β1 (CN- β1) isozymes. CN is inactive under resting conditions. For canonical isozymes, Ca2+ binding to CNB and CaM binding to CNA relieves the autoinhibition by the AIS (purple) and AID (blue). Under pathophysiological conditions, cleavage of the regulatory domain can produce a constitutively active enzyme (boxed). CN-β1 is only partially activated by Ca2+ and CaM binding due persistent occlusion of a substrate-binding grove by the LAVP sequence (green) found within the non-canonical carboxy terminal. Full activation may involve tethering of the inhibitory tail to membranes via palmitoylation of two cysteines (red).

2.2. Calcineurin-β1 Isozyme

The Calcineurin-β1 (CN-β1) isozyme (i.e. CNAβ1 complexed with CNB) exhibits an alternative mechanism of CN autoinhibition and activation (Figure 1B). This isozyme is conserved in vertebrates and ubiquitously expressed, albeit at low levels [34–36]. Alternative 3’ end processing of the PPP3CB transcript gives rise to CNAβ1, which is identical to canonical CNAβ2 through the CaM-binding domain but contains a unique C-tail (Figure 1A) [35]. This divergent C-terminal domain lacks the AID but contains a sequence motif, LAVP, which autoinhibits CN-β1 by blocking substrate-binding [36]. In vitro, this novel autoinhibitory mechanism confers higher basal and Ca2+-dependent activity to CN-β1 compared to canonical CN-β2 and decreases its dependence on CaM [36]. Furthermore, while CN-β2 is fully activated by Ca2+ and Ca2+/CaM, CN-β1 is still partially inhibited due to LAVP binding to the substrate-binding pocket (Figure 1B) [36]. Recent studies show that the unique CNAβ1 C-tail also contains a pair of conserved cysteine residues that are palmitoylated in vivo [37], and mediate CN-β1 localization to the Golgi, intracellular vesicles, and PM where it encounters a distinct set of interactors and substrates (see section 3.1.3). Palmitoylation is reversible, and palmitates on CNAβ1 turn over rapidly in vivo suggesting that CN-β1-modifying enzymes may be key regulators of this enzyme [37]. Which of the 23 human palmitoyl transferases target CN-β1 is not yet known, but the PM-localized thioesterase, α/β-Hydrolase Domain-Containing protein 17A (ABHD17A), depalmitoylates CN-β1 as well as other PM proteins [37, 38]. CN-β1 does not activate NFAT [39] and mice lacking CNAβ1 (but still expressing CNAβ2) are viable but display metabolic abnormalities and develop cardiac hypertrophy [40]. The Phosphoinositide-4-kinase type IIIα (PI4KIIIα) protein complex was identified as a substrate for CN-β1 (see section 3.1.3), but its full range of functions and substrates remain to be discovered [37].

2.3. Short Linear Motifs (SLiMs) are key for CN signaling

Despite its ubiquitous expression and essential roles beyond the immune system, only a ~100 proteins have been identified as CN substrates since its discovery more than 40 years ago, in part due to the transient nature of CN-substrate interactions [41]. However, it is now clear that CN and other protein phosphatases bind to their substrates via cognate short linear peptide motifs (SLiMs) [20]. This concept explains phosphatase substrate specificity and can be leveraged to map phosphatase signaling pathways systematically [20, 41, 42]. SLiMs are degenerate 3–10 aa-long sequences that lie within intrinsically disordered regions [43]. By forming transient interactions with globular domains that can be tuned and regulated, SLiMs form the backbone of signaling networks [43]. CN specifically recognizes two SLiMs, termed PxIxIT and LxVP, whose positioning with respect to each other, and to sites of dephosphorylation varies between substrates [19, 44]. This mechanism of substrate selection is highly conserved, and the two motifs serve different functions during dephosphorylation: PxIxIT binds to the CNA subunit of active or inactive CN, thus tethering CN to substrates and regulators and determining its distribution within cells [41, 45]. High affinity PxIxIT motifs inhibit CN in vivo by preventing substrate engagement [44, 46, 47] and mutations in CNA that impair PxIxT binding compromise its function [45, 48]. Furthermore, the primary sequence of each PxIxIT motif, as well as post translational modifications determine PxIxIT-CN affinity, which in turn specifies the Ca2+-concentration dependence of dephosphorylation in vivo [48–50]. Finally, acquisition and loss of PxIxIT motifs drive evolutionary rewiring of the CN signaling network [51]. In contrast, LxVP docks in a hydrophobic groove at the CNA/B interface that is accessible only after enzyme activation and thus engages only during dephosphorylation [21, 44]. Small molecules and peptides that block LxVP binding, including the immunosuppressants, FK506 and cyclosporin A and autoinhibitory sequences in CNA regulatory domains, inhibit dephosphorylation of protein substrates by CN without engaging the catalytic center of the enzyme [21, 36, 44].

Combining computational (http://slim.icr.ac.uk/motifs/calcineurin/) and experimental identification of PxIxIT and LxVP motifs in humans has identified hundreds of proteins that contain putative CN-binding SLiMs, several of which have been verified as new CN substrates, while others (as indicated in this review) are ripe for investigation [37, 41, 42, 52]. Furthermore, identifying SLiMs in a candidate substrate increases confidence that it interacts directly with CN, and mutating confirmed SLiMs allows the functional consequences of CN-binding to be assessed [37, 41, 42, 52]. These systematic approaches have revealed hitherto unknown functions for CN in Notch signaling, nucleocytoplasmic transport, phosphoinositide signaling and at centrosomes and cilia [37, 41, 42, 52].

Although there is no single phosphorylation motif that is uniquely dephosphorylated by CN, it does show a preference for sequences that contain basic residues upstream of the phosphosite at the −3 position, slightly prefers phosphothreonine over phosphoserine and, unlike other phosphatases, is not negatively impacted by the presence of a proline just after the phosphorylated residue [53–55]. Finally, within substrates, CN seems to preferentially dephosphorylate sites that contain the T/S(p)xxP motif, which is also found in the CN regulator, RCAN1 [54, 56].

2.4. Proximity labelling reveals SLiM-dependent CN interactions throughout the cell

Experimental approaches to identify CN substrates have historically relied on phosphoproteomics and/or physical capture of CN-substrate complexes [37, 42, 51, 57]. However, recently developed proximity-dependent labeling methods allow low affinity protein-protein interactions within a living cell to be detected [57]. Chief among these are proximity-dependent biotinylation methods in which a promiscuous biotin ligase is coupled to a bait protein of choice to identify a variety of labelled prey proteins [58–60]. For CN, proximal proteins that rely on SLiM binding were identified via proximity labelling coupled to mass spectrometry using fusions of both wild-type and SLiM-binding defective CNA to biotin ligases [41]. Of 397 CN-proximal proteins identified in HEK293 cells, approximately half showed SLiM-dependent proximity to CN and were enriched for the presence of CN-binding SLiMs [41]. These studies revealed CN proximity to multiple cellular locations. While some of these are known sites of Ca2+ signaling, i.e. the PM, ER, mitochondria, and endo-lysosomal compartments, others, especially the centrosome and nuclear pore complex, were unexpected and suggest new locations for Ca2+ signaling [41, 61].

3. CN containing signalosomes occur throughout mammalian cells

Because dephosphorylation occurs only when the phosphatase and its substrate co-localize with a source of Ca2+, CN signaling pathways must be mapped both spatially and temporally. The subcellular distribution of CN is determined by SLiM-mediated binding to its substrates, regulators and signaling scaffolds. In particular, these scaffolds include members of the A Kinase Anchoring Protein (AKAP) family, which target protein kinase A (PKA), cAMP-related enzymes and other signaling proteins to discrete subcellular compartments [52]. Several AKAPs coordinate CN and cAMP signaling including AKAP5 (also termed AKAP79/AKAP150 in human and rodent cells, respectively), AKAP6 and AKAP1, which will be discussed [52]. Below we review the evidence for localized CN functions in different intracellular compartments, with the goal of establishing a cellular atlas of CN signaling.

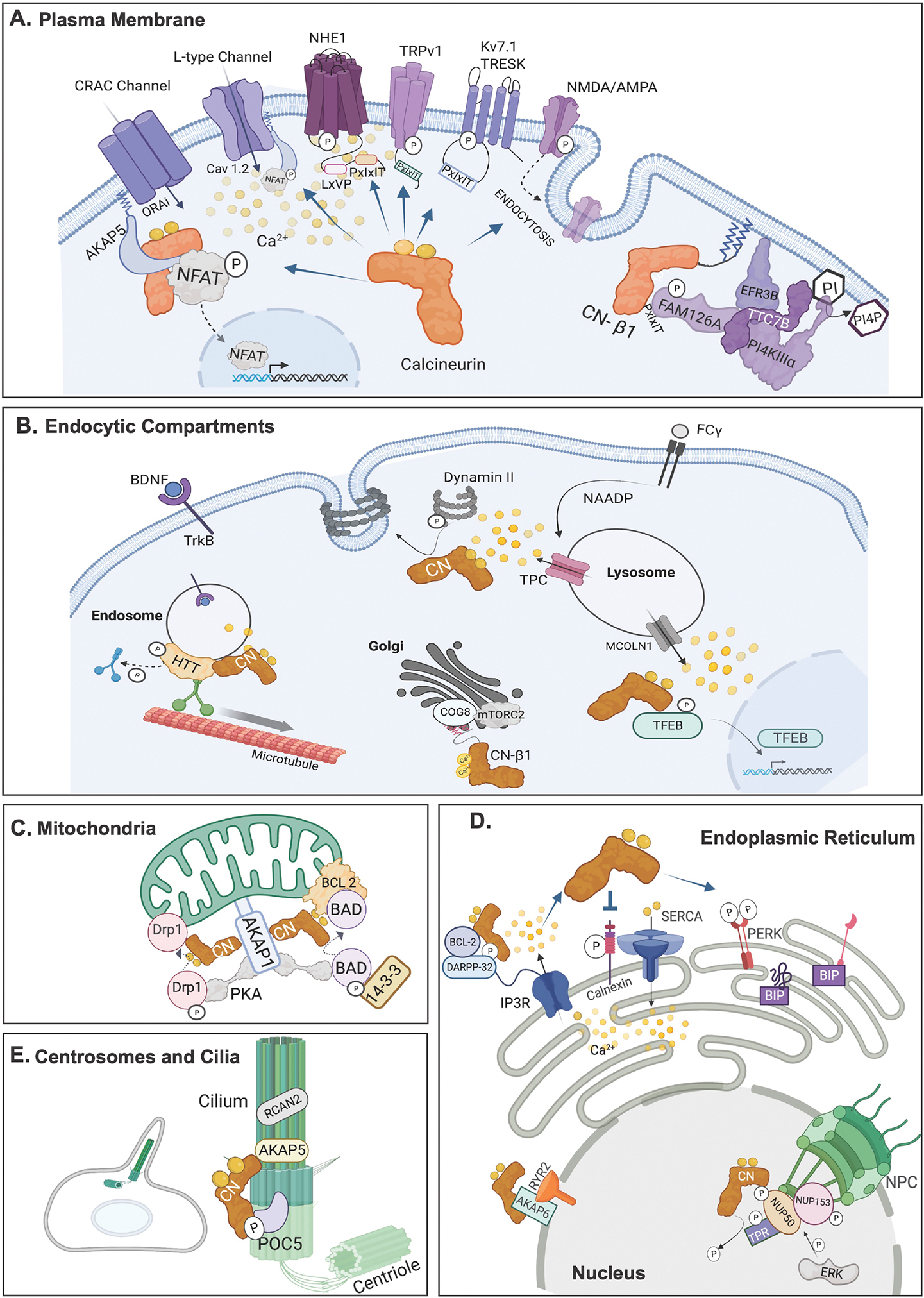

3.1. CN signaling at the plasma membrane

With multiple sites of Ca2+ entry, the PM is a major site for Ca2+ signaling. Canonical CN isoforms, CN-β2 and CNα, localize to the PM indirectly, via SLiM-mediated binding to PM substrates or to signaling scaffolds, such as AKAP5. In contrast, the CN-β1 isozyme associates directly with membranes via palmitoylation of its C-tail. Some of CN’s many functions and targets at the PM are highlighted below and shown in Figure 2A.

Fig. 2. CN signaling occurs in localized microdomains throughout the cell.

CN substrates and scaffolds in different subcellular locations are shown as discussed in the text. (A) Plasma Membrane. (B) Endocytic compartments. Endosomes, Lysosome and the Golgi Apparatus are shown. (C) Mitochondria (D) Endoplasmic Reticulum and Nucleus. In the nucleus the nuclear pore complex (NPC) is shown. (E) Centrosome and Cilia. All figures were created with BioRender.com.

3.1.1. CN regulates PM proteins that contain CN-binding SLiMS

NHE1:

CN dephosphorylates and inhibits sodium-hydrogen exchanger isofom-1 (NHE1), which couples cellular entry of Na+ with proton extrusion to regulate intracellular pH and cell volume [54]. This 12-transmembrane domain-containing protein contains a disordered, phosphorylated cytosolic tail that serves as a signaling scaffold by binding extracellular signal regulated kinase 2 (ERK2) and CN [54, 62]. The NHE1 tail binds to CN via a PxIxIT and an LxVP motif, separated by a dynamic linker that sweeps the CN surface. These interactions target CN to a particular phosphorylated residue (T779), which lies within a favored TxxP dephosphorylation motif. Thus, CN antagonizes ERK2 to inhibit NHE1, but pHi increases caused by NHE1 also activate CN-NFAT signaling [63] suggesting that these proteins may dynamically regulate each other’s function in vivo.

TRESK:

TWIK-related spinal cord potassium channel (TRESK) is a member of the two-pore K+ channel family that is encoded by the KCNK18 gene and harbors mutations associated with migraines [64]. TRESK is abundantly expressed in the dorsal root and trigeminal ganglia, where it contributes to resting potential and thus negatively regulates neuronal activity associated with neuropathic pain [64, 65]. TRESK also contributes to the development of neuropathic pain by regulating inflammation and apoptosis mediated by MAPK signaling [66]. Ca2+/CN activates TRESK, which contains a PxIxIT and an LxVP motif that mediate dephosphorylation of the channel [67, 68]. TRESK activation may decrease activity of the nociceptive transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1 (TRPV1) Ca2+ channel [69], which is also desensitized directly by CN [70].

TRPV1:

This non-selective cation channel responds to capsaicin, heat and other noxious stimuli to transduce signals that produce pain [71]. TRPV1 associates with AKAP5, which promotes sensitization of the channel via phosphorylation by PKA and/or protein kinase C (PKC) [72]. CN dephosphorylates and desensitizes TRPV1, which does not require AKAP5 [70] but may be mediated via two computationally predicted PxIxIT motifs in its C-tail [41]. Modulation of both TRESK and TRPV1 by CN may explain why some patients taking CN inhibitors experience pain [73]. In addition, CN associates with and reduces the current density of the T-type Ca2+ channel, CaV3.2 (encoded by CACNA1H), which is implicated in chronic pain, and also regulates pace-making in the heart [74, 75]. Both CACNA1H and closely related CACNA1G (CaV3.1) contain CN-binding motifs that were identified in silico and have not yet been verified experimentally [41].

Other ion channels that contain CN-binding SLiMs:

Systematic discovery of CN-binding SLiMs in the human proteome revealed that the resulting CN network is statistically enriched in ion channels, and especially K+ channels [41]. The CN-regulated ATP-sensitive inward rectifier l, Kir6.1 (KCNJ8) [76], voltage gated, Kv7.1 (KCNQ1), and Ca2+-regulated small conductance or SK channels (KCNN2, KCNN3) all contain predicted CN-binding motifs. These K+ channels regulate heart contractions and give rise to mutations that are associated with arrhythmogenic disorders [77]. Interestingly, mice with cardiac-specific deletions of CNB (and thus lacking CN activity) develop arrythmia [78]. Thus, possible regulation of these channels by CN should be further examined, and could underly the arrythmia observed in CN mutant mice. In sum, in silico prediction of CN-binding SLiMs suggests that additional roles for CN at the PM, and particularly in regulation of ion channel activity, await experimental validation.

3.1.2. AKAP5 organizes CN-regulated signalosomes at the PM

AKAP5 is a member of the AKAP family which, in addition to binding PKA, also anchors calmodulin, PKC, adenylate cyclases, phosphodiesterases and CN [79, 80]. CN interacts with AKAP5 via, a high affinity atypical PxIxIT motif, IAIIIT [81], an LxVP motif [82], and additional, low affinity sequences [83]. The role of CN in many AKAP5-mediated functions has been elucidated through studies of mice that express AKAP5 lacking the PxIxIT site [84]. AKAP5 is broadly expressed, and associates with a wide range of ion channels and receptors to create localized signalosomes that coordinate the antagonistic regulation of substrates by cAMP/PKA and Ca2+/CN [79]. Below we highlight only functions for AKAP5-PKA-CN signaling in synaptic plasticity and NFAT activation. Note that CN is highly abundant in neural tissue [85], and its functions in neuronal signaling and neurodegenerative disease have been reviewed elsewhere [86, 87].

Regulation of synaptic plasticity by AKAP5-PKA-CN:

Learning and memory occurs in the hippocampus, largely through phosphorylation dependent modification of synaptic strength, i.e. synaptic plasticity [88]. AKAP5 plays an important role in this process by targeting PKA and CN to neuronal membranes, where they phosphorylate/dephosphorylate the same residue on a critical Ca2+ channel, i.e. Ca2+ permeable AMPA receptors (CP-AMPAR) [89]. CP-AMPAR conductance as well as its insertion into vs removal from synaptic membranes (via endocytosis) is dictated by its phosphorylation status and AKAP5 targets CN and PKA to either synaptic or endosomal membranes depending on its palmitoylation status [90]. This activity-dependent regulation of CP-AMPAR directly impacts synaptic strength [90], and is disrupted by the β-amyloid (Aβ) oligomers that are produced during Alzheimer’s disease [91].

Regulation of CN-NFAT signaling by AKAP5:

Long lasting forms of memory require coupling of neuronal activity to changes in gene expression, and this is also regulated by AKAP5-CN-PKA signaling [92, 93]. AKAP5 associates with L-type voltage gated Ca2+ channels (LTCCs) and mediates their rapid phosphorylation by PKA, which activates Ca2+ influx and allows CN to dephosphorylate and inactivate the channel [92, 93]. Thus, AKAP5-targeted actions of PKA and CN on the LTCC determines the shape and magnitude of the Ca2+ signal generated by this channel. Furthermore, Ca2+ signals from LTCCs induce gene expression by NFAT, which requires dephosphorylation by CN to translocate to the nucleus [16]. AKAP organizes CN-NFAT signaling by directly recruiting both NFAT [94], and CN, which binds to a PxIxIT SLiM in AKAP5 [81]. CN affinity for this PxIxIT must be accurately tuned to allow both concentration of CN near the mouth of the LTCC, and sufficient dissociation so CN can engage with NFAT [81]. This dynamic AKAP-CN-LTCC-NFAT complex explains how Ca2+ entry through LTCCs selectively activates NFAT-mediated gene expression. Furthermore, in a neuron, Ca2+ signals generated at the dendrites, far from the nucleus, must be propagated through the cell to the neuronal cell body via a series of LTCC-Ca2+ spikes to achieve efficient activation of NFAT [95]. Thus, NFAT molecules that enter the nucleus are those localized to LTCCs in the soma, and the level of NFAT activity is determined by the total somatic Ca2+ signal [95].

Similarly, in T-cells AKAP5 associates with Orai1, the pore forming subunit of the Ca2+ release activated (CRAC) channel, which mediates store-operated calcium entry (SOCE) [96], to couple Ca2+ entry through this channel with NFAT activation [89]. This signaling is critical for adaptive immunity, as mutations in Orai1 lead to severe combined immunodeficiency [97]. Orai is activated by the ER Ca2+-sensing stromal interaction molecule (STIM) proteins [96]. In response to Ca2+ depletion from the ER lumen, caused by prolonged signaling, STIM clusters at ER-PM junctions, where it binds to and activates Orai, allowing both refilling of the Ca2+ store and CN-mediated activation of NFAT [96, 98]. The binding site for AKAP5 in the N terminus of Orai1 (specifically the Ora1alpha or long isoform) is absent in other Orai family members (Orai2 and 3) [99]. Loss-of-function mutations in Orai1, disruption of its AKAP5 binding site or knockdown of AKAP5 all block the activation and nuclear translocation of NFAT1, whereas buffering of cytoplasmic Ca2+ with the slow-acting Ca2+ chelator EGTA has no effect [99]. Overall, the requirement for AKAP5 in CN-NFAT signaling in both excitable and non-excitable cells illustrates how precise localization of these signaling complexes to sites of Ca2+ influx allows focal signaling events at the PM to directly impact nuclear processes.

3.1.3. The CN-β1 isozyme regulates the PI4KIIIα complex at the PM

Palmitoylation of the unique CNAβ1 C-tail allows this isozyme to associate directly with the PM, Golgi and intracellular vesicles where it is targeted to membrane-associated substrates [37]. Compared to cytosolic CN-β2, CN-β1, preferentially interacts with membrane-associated proteins, including the PM-localized phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase type IIIα (PI4KIIIα) complex, which phosphorylates phosphatidylinositol at the fourth position of the inositol ring to produce phosphatidylinositol-4 phosphate (PI4P), a rate limiting precursor for the signaling lipid, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PI(4,5)P2). The PI4KIIIα complex is composed of four proteins: PI4KA, TTC7B, FAM126A and EFR3B. PI4KA, the catalytic subunit, combines with regulatory proteins TTC7A/B and FAM126A in the cytosol, and this trimer is recruited to the PM via binding to the anchoring protein, EFR3A/B [100] (Figure 2A). The disordered C-tail of FAM126A regulates PI4KIIIα complex activity [101, 102] and contains a high affinity CN-binding PxIxIT motif that is required for dephosphorylation of FAM126A by CN, while PI4KA contains a second non-canonical PxIxIT motif [37]. CN-β1 is thought to regulate PI4P synthesis by the PI4KIIIα complex during signaling by G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs). GPCR receptors that couple to Gq-type members of the heterotrimeric family of GTP-binding proteins initiate Ca2+ release from the ER by activating phospholipase C-mediated production of inositol 1,4,5,-trisphosphate (IP3). Under these conditions, PI(4,5)P2 is rapidly depleted from the PM, and activation of PI4P synthesis by the PI4KIIIα complex is required to sustain signaling [103]. Inhibiting either PKC or CN reduce this activation of PI4P synthesis, presumably by modifying PI4KIIIα complex phosphorylation, although further elucidation of this mechanism is required. These studies show that palmitoylation allows CN-β1 to carry out unique regulatory roles at membranes. Furthermore, association of the palmitoylated CNAβ1 C-terminus with the PM may also displace the autoinhibitory LxVP sequence, causing activation of the phosphatase (Figure 1B). Additional substrates and functions for this enzyme await identification as studies of mice lacking this isoform are viable but exhibit cardiac hypertrophy and metabolic changes [40].

3.2. CN signaling at endocytic compartments:

The Golgi apparatus, endosomes, and lysosomes all store and release Ca2+ [104, 105] and are emerging as sites for CN signaling. Little is known about roles for CN at the Golgi, although CN-β1 was reported to bind to COG8 and activate signaling by mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTORC2) and AK strain transforming (Akt) kinases [106] (Figure 2B). CN regulates the biogenesis of lysosomes via activation of transcription factor EB (TFEB) [107, 108] and also regulates the formation of endosomes via the clathrin-independent mechanism termed activity-dependent bulk endocytosis in neurons, where it also participates in synaptic vesicle recycling [109–112]. Here, we focus on newly identified roles for CN signaling at endo-lysosomal compartments.

3.2.1. CN signaling at endo-lysosomal Ca2+ nanodomains regulates phagocytosis

Macrophages kill pathogens through a process termed phagocytosis, which is initiated when immunoglobulin G-coated pathogens bind to Fc-γ receptors on the surface of macrophages, causing an increase in intracellular [Ca2+] [113]. The pathogen is subsequently internalized into a phagosome, which then fuses with lysosomes to create an acidic compartment that digests the pathogen [113]. Surprisingly, phagocytosis is initiated by a Ca2+ signal that originates from lysosomes and locally activates CN (Figure 2B) [7] Upon activation of the Fc-γ receptor the Ca2+ mobilizing messenger, nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate, triggers highly localized Ca2+ release from lysosomes via two-pore channels (TPCs), which is efficiently blocked by targeting the Ca2+-binding protein, calbindin, to the lysosome but not by disrupting Ca2+ signaling more globally with the slow Ca2+ chelator, EGTA. This TPC- released Ca2+ rapidly activates CN, which in turn dephosphorylates and stimulates the GTPase dynamin-2, allowing its trafficking to the PM where it is required for phagosome scission and endocytosis. Thus, this study elegantly reveals that peri-lysosomal Ca2+ signaling nanodomains drive phagocytosis. However, mechanisms that recruit CN and phosphorylated dynamin-2 to this Ca2+ signaling nanodomain remain to be identified.

3.2.2. CN regulates directional transport of neurotrophic signaling endosomes

CN on endosomes was recently shown to regulate neurotrophic signaling, which promotes neural connectivity (Figure 2B) [114]. At the pre-synapse of neurons, Brain-derived Neurotrophic Factor binds to and activates its receptor, tyrosine receptor kinase B (TrkB), and ligand-receptor complexes are then packaged into ‘signaling endosomes’ which must travel to the cell soma to deliver survival signals. CN dephosphorylates the huntingtin protein (HTT) on the surface of signaling endosomes to determine their transport direction. When phosphorylated, HTT promotes anterograde endosome transport (i.e. away from the soma) via interaction with the kinesin microtubule motor. However, in response to the Ca2+ signal generated downstream of TrkB activation, CN dephosphorylates HTT, causing dynein-mediated retrograde transport of endosomes toward the soma. Thus, CN acts locally, allowing endosomal vesicles to “choose” their transport direction, a mechanism that may be generalizable to other signaling endosomes. How CN associates with the endosomal surface and whether endosomal Ca2+ stores contribute to signaling are yet to be investigated. However, this new pathway promises to shed new light on CN signaling in pathologies such as Huntington`s Disease and Rett syndrome, in which retrograde trafficking of signaling endosomes is disrupted [115].

3.3. CN signaling at the mitochondria

In addition to being sites of cellular ATP production, mitochondria also regulate lipid metabolism, apoptosis, and participate in Ca2+ signaling [116]. Mitochondria sequester Ca2+ via the Mitochondrial Calcium Uniporter and expel Ca2+ via specific efflux pathways [117]. These activities alter the amplitude and dynamics of cytosolic Ca2+ signals and regulate mitochondrial metabolism [2]. CN signaling at mitochondria promotes apoptosis through substrates dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) and Bcl-2 associated death promoter protein (BAD), and sperm motility via Spermatogenesis-Associated 33 protein (SPATA33) (Figure 2C).

3.3.1. Regulation of mitochondrial dynamics

Mitochondria undergo dynamic fusion and fission which regulate their shape and function, with mitochondrial fragmentation being an early step in apoptosis [118]. Drp1, a large GTPase that causes fission by physically constricting and severing the outer mitochondrial membrane, is regulated by phosphorylation [119]. PKA inhibits Drp1, and phospho-mimetic mutations decrease fission and cell sensitivity to apoptosis [120]. CN dephosphorylates Drp1 through an LxVP motif to promote fission which sensitizes cells for apoptosis [121]. Modulating the affinity of this SLiM for CN directly impacts dephosphorylation efficiency, mitochondrial shape and the amount of neuronal death induced by oxygen-glucose deprivation [121]. PKA is targeted to mitochondria by binding the AKAP1 scaffold, which has also been shown to associate with CN [122] and with NCX3, a mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, to facilitate Ca2+ efflux from the mitochondria, and potentially activate CN [123]. Thus, like AKAP5, AKAP1 may organize a mitochondrially localized signalosome that fine-tunes Drp1 function and allows PKA and CN to antagonistically regulate mitochondrial function. This interplay is particularly critical in cardiomyocytes and hippocampal neurons, where preventing Drp1 mediated mitochondrial fission is linked to defects in cardiac metabolism, hypertrophy, neuronal development/morphogenesis and Parkinson’s disease [124].

3.3.2. Activation of apoptosis

CN also regulates the pro-apoptotic protein BAD [104]. Under nonapoptotic conditions, phosphorylated BAD is sequestered in the cytosol via binding to 14-3-3 proteins [125]. Upon apoptotic stimuli, such as starvation, CN dephosphorylates BAD, causing its translocation to the mitochondrial outer membrane where it binds to the antiapoptotic protein B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) and B-cell lymphoma-extra large (Bcl-XL) proteins [104]. This displaces Bcl-2-associated X protein (Bax), which initiates mitochondrial membrane permeability and the caspase-3 apoptotic signaling cascade [126]. PKA is a key kinase that inactivates BAD, and as for Drp1, AKAP1 targeting of PKA to the outer mitochondrial membrane modulates BAD phosphorylation and sensitivity to apoptotic signals [124]. Thus, AKAP1 seems to organize a mitochondrial signaling hub that coordinates signaling by PKA and CN to critically regulate mitochondrial function in multiple tissues [127].

3.3.3. Regulation of sperm motility

CN is essential for male fertility and sperm motility [128], where a specialized form of CN composed of PPP3CC (catalytic subunit) and PPP3R2 (regulatory subunit) is expressed [129]. Recently the sperm protein SPATA33 was shown to recruit CN to mitochondria in these cells [130]. SPATA33 was identified first as a testis-enriched PxIxIT-containing protein whose deletion compromises sperm motility [41, 130]. SPATA33 localizes to mitochondria in the sperm midpiece by binding to the mitochondrial Voltage-Dependent Anion Channel 2 (VDAC2), and may function in sperm motility by targeting CN to mitochondria, where CN potentially regulates VDAC2 and/or other mitochondrial proteins [130].

Together, these studies show that CN targeting to mitochondria enables rapid regulation of these organelles. Future studies are required to identify all CN substrates at mitochondria as well as the source and regulation of Ca2+ signals that activate this phosphatase.

3.4. CN signaling at the Endoplasmic Reticulum

The ER is a major intracellular Ca2+ store that contains approximately 2mM Ca2+ [2]. In response to a variety of cellular stimuli, Ca2+ is released from the ER through either inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (IP3Rs) and/or ryanodine receptors (RyRs), leading to global increases in intracellular Ca2+ [ 2, 119]. Thus, Ca2+ homeostasis within the ER is not only necessary for ER functions such as protein folding, quality control and lipid synthesis, but also to generate intracellular Ca2+ signals, and to activate SOCE, which refills this Ca2+ store when it is depleted [131]. Roles for CN at this major source of Ca2+ are summarized below and shown in Figure 2D.

3.4.1. CN negatively regulates Ca2+ release from IP3R

Under many signaling conditions, IP3 binds to ER-localized IP3Rs to release Ca2+ from this organelle [2]. Thus, IP3Rs are signaling hubs that bind to and are regulated by many proteins, including kinases and phosphatases, in part because excessive Ca2+ release leads to cell death [132]. PKA phosphorylates IP3R which stimulates Ca2+ release, and Protein Phosphatase 1 (PP1) reverses this phosphorylation [133]. Bcl-2 also binds directly to the IP3R and inhibits Ca2+ release, which contributes to Bcl-2 antiapoptotic activity, especially in cancers such as Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) in which Bcl-2 is highly expressed [134, 135]. This occurs through a rapid negative feedback pathway that requires CN and Dopamine- and cAMP-regulated phosphoprotein-32 (DARPP-32), which inhibits PP1 when phosphorylated by PKA, but is dephosphorylated and inactivated by CN [122]. Bcl-2 binds directly to DARPP-32 and CN and targets both signaling molecules to the IP3R [136, 137]. Thus, in Bcl-2 overexpressing cells, when PKA phosphorylates the IP3R and stimulates Ca2+ release, activation of CN then dephosphorylates DARPP-32 allowing activation of PP1 and IP3R dephosphorylation, which inhibits Ca2+ release. Treating primary human CLL cells with a peptide that releases Bcl-2 from the IP3R causes elevated Ca2+ and apoptosis, likely because this Bcl2-CN-DARPP-32-dependent negative feedback is disrupted [137, 138].

3.4.2. CN promotes refilling of ER calcium

The efficient refilling of ER Ca2+ stores from the cytosol by the sarcoendoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase, SERCA, is regulated by a CN-dependent feedback loop: Calnexin, a Ca2+-transmembrane ER protein, interacts with and inhibits the activity of SERCA when the ER lumen is optimally loaded with Ca2+ [124]. However, following IP3-mediated Ca2+ release from ER, CN dephosphorylates calnexin on its cytosolic domain, causing its release from SERCA, which activates the pump to refill the Ca2+ store [125].

3.4.3. CN regulates the unfolded protein response pathway

In addition to activating SERCA, CN modulates one arm of the Unfolded Protein Response (UPR), a signaling pathway that restores ER function when an imbalance between protein folding and degradation causes the accumulation of misfolded proteins [139]. Under normal conditions, the luminal domain of Protein kinase R-like Endoplasmic Reticulum kinase (PERK), binds to the major ER chaperone, Binding Immunoglobulin Protein (BIP) (Figure 2D) [139]. However, during ER stress, increased binding of unfolded proteins to BIP cause its dissociation from PERK, and activation of the cytoplasmic PERK kinase domain via autophosphorylation [139]. Active PERK then phosphorylates eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 (eIF2a), causing attenuation of protein translation which allows the ER to recover [139]. In Xenopus oocytes, Ca2+ release during ER stress was shown to induce CN binding to and activation of PERK through an undetermined mechanism [140]. Furthermore, knockdown or inhibition of CN attenuated PERK-activated UPR and potentiated apoptotic responses. PERK was also shown to phosphorylate and inhibit CN suggesting mutual regulation of these proteins [140]. UPR activation is especially critical in the nervous system, where accumulation of misfolded proteins and ER stress is the hallmark of many neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and Huntington’s diseases [141]. Recent studies have also suggested a role for the CN-PERK interaction in regulating Ca2+ dynamics during insulin secretion in pancreatic β cells [142], induction of ventricular arrhythmias in diabetic cardiomyopathies [143], as well as the coordination of ER/PM contact site formation through F-actin remodeling [144].

Thus, CN may regulate ER function through complementary mechanisms that promote refilling of the Ca2+ store and induce the ER response to stress. How CN associates with the ER is not yet clear, although CN-proximal and SLiM-containing proteins include the ER structuring Reticulon family proteins, Rtn1 and Rtn4, and BIP, which also has roles in the cytoplasm [41, 145].

3.5. Nuclear functions for CN

CN has roles in the nucleus (Figure 2D), and Ca2+ dynamics in this compartment are distinct from those in the cytosol [146, 147]. Ca2+ can enter the nucleus from the cytosol through nuclear pores, or be released from the nuclear envelope, which is contiguous with the ER and contains both IP3Rs and RyRs [148, 149]. CN contains both nuclear localization (NLS) and nuclear export sequences (NES) that allow it to access nuclear proteins [150] and can also ‘hitchhike’ with partner proteins, such as NFAT, which has been reported to shuttle CN in and out of the nucleus [151]. In addition to NFAT, CN dephosphorylates and activates other transcription factors, including CREB-Regulated Transcription Coactivator 1, TFEB, and Myocyte Enhancer Factor-2 (MEF2), to mediate Ca2+ regulated gene expression [108, 152, 153]. How these events are spatially organized is unknown. By analogy with NFAT-CN-AKAP signaling, as yet undiscovered mechanisms may couple activation of these transcription factors to specific Ca2+ microdomains.

3.5.1. CN signaling at the Nuclear Envelope

CN localizes both to the nuclear envelope via binding to AKAP6, and to nuclear pore complexes (Figure 2D). AKAP6, also known as mAKAPβ, is expressed primarily in striated muscle including cardiomyocytes, and associates with the nuclear envelope via a cluster of spectrin-like repeats [154]. AKAP6 directly scaffolds multiple proteins including RyR, calcineurin (the CNAβ isoform), PKA and MEF2, and is required for CN-dependent regulation of NFAT and MEF2 that promotes cardiac hypertrophy in response to β–adrenergic signaling [154]. Thus, AKAP6 is proposed to organize a ‘signalosome’ at the nuclear envelope that locally organizes and integrates CN activity with other signaling pathways during cardiac hypertrophy.

3.5.2. CN signaling at the Nuclear Pore Complex

Recently, CN was shown to interact in a SLiM-dependent manner with several proteins in the nuclear pore complex (NPC), including components of the nuclear basket which projects into the nucleoplasm (Nucleoporin-153, Translocated promoter region protein and Nucleoporin-50) (Figure 2D) [41]. In vitro, CN directly dephosphorylates these nuclear basket proteins after phosphorylation by ERK, a kinase that phosphorylates NPC proteins in vivo to inhibit nucleocytoplasmic transport [41, 155, 156]. Incubating cells with CN inhibitors decreased the nuclear accumulation of an NLS-containing transport reporter, and increased phosphorylation of several nuclear pore proteins, also called nucleoporins [41]. These surprising findings suggest that a pool of NPC-localized CN dephosphorylates nucleoporins to increase transport through the pore, and that the NPCs may function as a local Ca2+ signaling microdomain. Indeed, Proximity-Ligation assays showed that endogenous CN and NPC proteins interact in a PxIxIT-dependent manner in vivo [41]. While previous work showed that changes in cytosolic [Ca2+] alter the structure of key transport nucleoporins [148, 157–159], there are conflicting reports in the literature as to whether Ca2+ regulates nucleocytoplasmic transport [160, 161]. Recent evidence that CN binds to and regulates NPC proteins indicates that Ca2+ signaling at NPCs should be re-examined using modern tools.

3.6. CN signaling at centrosomes and cilia

Centrosomes are microtubule organizing centers, composed of two centrioles associated with pericentriolar material, that nucleate microtubules in interphase and form the poles of the mitotic spindle [162]. Centrosomes contain Ca2+-binding proteins, calmodulin and centrin, and Ca2+ signals have been observed at these organelles during mitosis [163]. A pool of CN localizes to centrosomes, where CN binds directly to POC5, one component of a protein scaffold in the centriole lumen that stabilizes this structure [61, 164] (Figure 2E). CN dephosphorylates POC5 in vitro and CN inhibitors alter POC distribution within the centriole lumen [51]. Whether CN regulates POC5 phosphorylation and function in vivo and how it is targeted to centrosomes remains to be determined.

In most non-proliferating cells, centrioles transform into basal bodies which direct formation of primary cilia, i.e. non-motile appendages that are specialized sites for Hedgehog and Ca2+ signaling whose disruption causes a group of disorders known as ciliopathies (Figure 2E) [165, 166]. POC5 is also required for ciliogenesis [167]. However, inhibiting CN does not affect cilia number but rather increases cilia length [51], consistent with previous findings that deletion of RCAN2, a negative regulator of CN that also localizes to cilia, shortens cilia [168] (Figure 2E). How CN alters cilia length is not yet known, but may occur via regulation of POC5 or other centrosomal proteins that contain predicted CN-binding SLiMs such as HAUS6, a component of the augmin complex [41, 169]. Interestingly, AKAP5 also localizes to primary cilia [170], and could mediate CN-dependent modulation of ciliary cAMP/PKA signaling, which also impacts cilia length [171]. Thus, unraveling CN actions in cilia and at centrosomes promises to reveal new aspects of CN signaling and possible connections to ciliopathies.

4. Conclusion

Our current state of knowledge shows that CN plays critical roles throughout the body, and that NFAT is just one of an arsenal of CN substrates. New SLiM-directed approaches are revealing CN functions systematically, and techniques like proximity-dependent biotinylation allow these SLiM-dependent interactions, which influence the subcellular targeting of CN, to be identified. Elucidating where and when CN acts is essential for mapping CN and its substrates to specific Ca2+ signaling microdomains throughout the cell, and disrupting these local interactions provides exquisite insights into the discrete functions of each localized signaling event. In total, these advances are providing a much more comprehensive view of CN signaling than ever before, which promises to explain adverse effects of CN inhibitors (CysA, FK506) and the clinical presentations associated with mutations in human CN genes. Far from being a one-note song, it is clear that CN directs a symphony of Ca2+ dependent signaling events, many of which are yet to be revealed.

Highlights.

Calcineurin, the Ca2+/calmodulin-activated phosphatase acts throughout the cell

Calcineurin regulates substrates in localized Ca2+ signaling microdomains

Calcineurin acts at PM, endosomes, ER, mitochondria, nuclear pores and centrosomes.

Calcineurin binds cognate Short Linear Motifs in substrates, scaffolds, regulators

Discovery of SLiMs systematically maps calcineurin signaling pathways

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Angela Barth, Eirini Tsekitsidou and Sneha Roy for critical reading of this manuscript. M.S.C. and I.U.T. are supported by grant R35GM136243 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

CRediT author statement:

M.S.C. and I.U.T. conceptualized and wrote the manuscript

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- [1].Berridge MJ, Lipp P, Bootman MD, The versatility and universality of calcium signalling, Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 1(1) (2000) 11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bootman MD, Bultynck G, Fundamentals of Cellular Calcium Signaling: A Primer, Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 12(1) (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Verkhratsky AJ, Petersen OH, Neuronal calcium stores, Cell Calcium 24(5–6) (1998) 333–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Schwaller B, Cytosolic Ca(2+) Buffers Are Inherently Ca(2+) Signal Modulators, Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 12(1) (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Chen J, Sitsel A, Benoy V, Sepulveda MR, Vangheluwe P, Primary Active Ca(2+) Transport Systems in Health and Disease, Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 12(2) (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Mehta S, Zhang J, Dynamic visualization of calcium-dependent signaling in cellular microdomains, Cell Calcium 58(4) (2015) 333–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Davis LC, Morgan AJ, Galione A, NAADP-regulated two-pore channels drive phagocytosis through endo-lysosomal Ca(2+) nanodomains, calcineurin and dynamin, EMBO J 39(14) (2020) e104058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Rodrigues MA, Gomes DA, Leite MF, Grant W, Zhang L, Lam W, Cheng YC, Bennett AM, Nathanson MH, Nucleoplasmic calcium is required for cell proliferation, J Biol Chem 282(23) (2007) 17061–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Andrews C, Xu Y, Kirberger M, Yang JJ, Structural Aspects and Prediction of Calmodulin-Binding Proteins, Int J Mol Sci 22(1) (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Takemoto-Kimura S, Suzuki K, Horigane SI, Kamijo S, Inoue M, Sakamoto M, Fujii H, Bito H, Calmodulin kinases: essential regulators in health and disease, J Neurochem 141(6) (2017) 808–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Klee CB, Crouch TH, Krinks MH, Calcineurin: a calcium- and calmodulin-binding protein of the nervous system, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 76(12) (1979) 6270–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Stewart AA, Ingebritsen TS, Manalan A, Klee CB, Cohen P, Discovery of a Ca2+- and calmodulin-dependent protein phosphatase: probable identity with calcineurin (CaM-BP80), FEBS Lett 137(1) (1982) 80–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Park HS, Lee SC, Cardenas ME, Heitman J, Calcium-Calmodulin-Calcineurin Signaling: A Globally Conserved Virulence Cascade in Eukaryotic Microbial Pathogens, Cell Host Microbe 26(4) (2019) 453–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Mizuguchi T, Nakashima M, Kato M, Okamoto N, Kurahashi H, Ekhilevitch N, Shiina M, Nishimura G, Shibata T, Matsuo M, Ikeda T, Ogata K, Tsuchida N, Mitsuhashi S, Miyatake S, Takata A, Miyake N, Hata K, Kaname T, Matsubara Y, Saitsu H, Matsumoto N, Loss-of-function and gain-of-function mutations in PPP3CA cause two distinct disorders, Hum Mol Genet 27(8) (2018) 1421–1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Myers CT, Stong N, Mountier EI, Helbig KL, Freytag S, Sullivan JE, Ben Zeev B, Nissenkorn A, Tzadok M, Heimer G, Shinde DN, Rezazadeh A, Regan BM, Oliver KL, Ernst ME, Lippa NC, Mulhern MS, Ren Z, Poduri A, Andrade DM, Bird LM, Bahlo M, Berkovic SF, Lowenstein DH, Scheffer IE, Sadleir LG, Goldstein DB, Mefford HC, Heinzen EL, De Novo Mutations in PPP3CA Cause Severe Neurodevelopmental Disease with Seizures, Am J Hum Genet 101(4) (2017) 516–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Jain J, McCaffrey PG, Miner Z, Kerppola TK, Lambert JN, Verdine GL, Curran T, Rao A, The T-cell transcription factor NFATp is a substrate for calcineurin and interacts with Fos and Jun, Nature 365(6444) (1993) 352–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Liu J, Farmer JD Jr., Lane WS, Friedman J, Weissman I, Schreiber SL, Calcineurin is a common target of cyclophilin-cyclosporin A and FKBP-FK506 complexes, Cell 66(4) (1991) 807–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Azzi JR, Sayegh MH, Mallat SG, Calcineurin inhibitors: 40 years later, can’t live without, J Immunol 191(12) (2013) 5785–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Roy J, Cyert MS, Identifying New Substrates and Functions for an Old Enzyme: Calcineurin, Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 12(3) (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Brautigan DL, Shenolikar S, Protein Serine/Threonine Phosphatases: Keys to Unlocking Regulators and Substrates, Annu Rev Biochem 87 (2018) 921–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Li SJ, Wang J, Ma L, Lu C, Wang J, Wu JW, Wang ZX, Cooperative autoinhibition and multi-level activation mechanisms of calcineurin, Cell Res 26(3) (2016) 336–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Hashimoto Y, Perrino BA, Soderling TR, Identification of an autoinhibitory domain in calcineurin, J Biol Chem 265(4) (1990) 1924–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kissinger CR, Parge HE, Knighton DR, Lewis CT, Pelletier LA, Tempczyk A, Kalish VJ, Tucker KD, Showalter RE, Moomaw EW, et al. , Crystal structures of human calcineurin and the human FKBP12-FK506-calcineurin complex, Nature 378(6557) (1995) 641–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Stemmer PM, Klee CB, Dual calcium ion regulation of calcineurin by calmodulin and calcineurin B, Biochemistry 33(22) (1994) 6859–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kakalis LT, Kennedy M, Sikkink R, Rusnak F, Armitage IM, Characterization of the calcium-binding sites of calcineurin B, FEBS Lett 362(1) (1995) 55–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gallagher SC, Gao ZH, Li S, Dyer RB, Trewhella J, Klee CB, There is communication between all four Ca(2+)-bindings sites of calcineurin B, Biochemistry 40(40) (2001) 12094–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Perrino BA, Ng LY, Soderling TR, Calcium regulation of calcineurin phosphatase activity by its B subunit and calmodulin. Role of the autoinhibitory domain, J Biol Chem 270(1) (1995) 340–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Wu HY, Tomizawa K, Matsui H, Calpain-calcineurin signaling in the pathogenesis of calcium-dependent disorder, Acta Med Okayama 61(3) (2007) 123–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Liu F, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Oda Y, Tomizawa K, Gong CX, Truncation and activation of calcineurin A by calpain I in Alzheimer disease brain, J Biol Chem 280(45) (2005) 37755–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Newman RH, Zhang J, Visualization of phosphatase activity in living cells with a FRET-based calcineurin activity sensor, Mol Biosyst 4(6) (2008) 496–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Mehta S, Aye-Han NN, Ganesan A, Oldach L, Gorshkov K, Zhang J, Calmodulin-controlled spatial decoding of oscillatory Ca2+ signals by calcineurin, Elife 3 (2014) e03765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Bazzazi H, Sang L, Dick IE, Joshi-Mukherjee R, Yang W, Yue DT, Novel fluorescence resonance energy transfer-based reporter reveals differential calcineurin activation in neonatal and adult cardiomyocytes, J Physiol 593(17) (2015) 3865–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Chaklader M, Rothermel BA, Calcineurin in the heart: New horizons for an old friend, Cell Signal 87 (2021) 110134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Guerini D, Klee CB, Cloning of human calcineurin A: evidence for two isozymes and identification of a polyproline structural domain, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 86(23) (1989) 9183–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Lara-Pezzi E, Winn N, Paul A, McCullagh K, Slominsky E, Santini MP, Mourkioti F, Sarathchandra P, Fukushima S, Suzuki K, Rosenthal N, A naturally occurring calcineurin variant inhibits FoxO activity and enhances skeletal muscle regeneration, J Cell Biol 179(6) (2007) 1205–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Bond R, Ly N, Cyert MS, The unique C terminus of the calcineurin isoform CNAbeta1 confers non-canonical regulation of enzyme activity by Ca(2+) and calmodulin, J Biol Chem 292(40) (2017) 16709–16721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ulengin-Talkish I, Parson MAH, Jenkins ML, Roy J, Shih AZL, St-Denis N, Gulyas G, Balla T, Gingras AC, Varnai P, Conibear E, Burke JE, Cyert MS, Palmitoylation targets the calcineurin phosphatase to the phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase complex at the plasma membrane, Nat Commun 12(1) (2021) 6064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Remsberg JR, Suciu RM, Zambetti NA, Hanigan TW, Firestone AJ, Inguva A, Long A, Ngo N, Lum KM, Henry CL, Richardson SK, Predovic M, Huang B, Dix MM, Howell AR, Niphakis MJ, Shannon K, Cravatt BF, ABHD17 regulation of plasma membrane palmitoylation and N-Ras-dependent cancer growth, Nat Chem Biol 17(8) (2021) 856–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Felkin LE, Narita T, Germack R, Shintani Y, Takahashi K, Sarathchandra P, Lopez-Olaneta MM, Gomez-Salinero JM, Suzuki K, Barton PJ, Rosenthal N, Lara-Pezzi E, Calcineurin splicing variant calcineurin Abeta1 improves cardiac function after myocardial infarction without inducing hypertrophy, Circulation 123(24) (2011) 2838–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Padron-Barthe L, Villalba-Orero M, Gomez-Salinero JM, Acin-Perez R, Cogliati S, Lopez-Olaneta M, Ortiz-Sanchez P, Bonzon-Kulichenko E, Vazquez J, Garcia-Pavia P, Rosenthal N, Enriquez JA, Lara-Pezzi E, Activation of Serine One-Carbon Metabolism by Calcineurin Abeta1 Reduces Myocardial Hypertrophy and Improves Ventricular Function, J Am Coll Cardiol 71(6) (2018) 654–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Wigington CP, Roy J, Damle NP, Yadav VK, Blikstad C, Resch E, Wong CJ, Mackay DR, Wang JT, Krystkowiak I, Bradburn DA, Tsekitsidou E, Hong SH, Kaderali MA, Xu SL, Stearns T, Gingras AC, Ullman KS, Ivarsson Y, Davey NE, Cyert MS, Systematic Discovery of Short Linear Motifs Decodes Calcineurin Phosphatase Signaling, Mol Cell 79(2) (2020) 342–358 e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Brauer BL, Moon TM, Sheftic SR, Nasa I, Page R, Peti W, Kettenbach AN, Leveraging New Definitions of the LxVP SLiM To Discover Novel Calcineurin Regulators and Substrates, ACS Chem Biol 14(12) (2019) 2672–2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Tompa P, Davey NE, Gibson TJ, Babu MM, A million peptide motifs for the molecular biologist, Mol Cell 55(2) (2014) 161–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Grigoriu S, Bond R, Cossio P, Chen JA, Ly N, Hummer G, Page R, Cyert MS, Peti W, The molecular mechanism of substrate engagement and immunosuppressant inhibition of calcineurin, PLoS Biol 11(2) (2013) e1001492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Li H, Rao A, Hogan PG, Structural delineation of the calcineurin-NFAT interaction and its parallels to PP1 targeting interactions, J Mol Biol 342(5) (2004) 1659–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Aramburu J, Yaffe MB, Lopez-Rodriguez C, Cantley LC, Hogan PG, Rao A, Affinity-driven peptide selection of an NFAT inhibitor more selective than cyclosporin A, Science 285(5436) (1999) 2129–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Roy J, Cyert MS, Cracking the phosphatase code: docking interactions determine substrate specificity, Sci Signal 2(100) (2009) re9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Roy J, Li H, Hogan PG, Cyert MS, A conserved docking site modulates substrate affinity for calcineurin, signaling output, and in vivo function, Mol Cell 25(6) (2007) 889–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Nguyen HQ, Roy J, Harink B, Damle NP, Latorraca NR, Baxter BC, Brower K, Longwell SA, Kortemme T, Thorn KS, Cyert MS, Fordyce PM, Quantitative mapping of protein-peptide affinity landscapes using spectrally encoded beads, Elife 8 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Li H, Zhang L, Rao A, Harrison SC, Hogan PG, Structure of calcineurin in complex with PVIVIT peptide: portrait of a low-affinity signalling interaction, J Mol Biol 369(5) (2007) 1296–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Goldman A, Roy J, Bodenmiller B, Wanka S, Landry CR, Aebersold R, Cyert MS, The calcineurin signaling network evolves via conserved kinase-phosphatase modules that transcend substrate identity, Mol Cell 55(3) (2014) 422–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Sheftic SR, Page R, Peti W, Investigating the human Calcineurin Interaction Network using the piLxVP SLiM, Sci Rep 6 (2016) 38920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Donella-Deana A, Krinks MH, Ruzzene M, Klee C, Pinna LA, Dephosphorylation of phosphopeptides by calcineurin (protein phosphatase 2B), Eur J Biochem 219(1–2) (1994) 109–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Hendus-Altenburger R, Wang X, Sjogaard-Frich LM, Pedraz-Cuesta E, Sheftic SR, Bendsoe AH, Page R, Kragelund BB, Pedersen SF, Peti W, Molecular basis for the binding and selective dephosphorylation of Na(+)/H(+) exchanger 1 by calcineurin, Nat Commun 10(1) (2019) 3489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Li X, Wilmanns M, Thornton J, Kohn M, Elucidating human phosphatase-substrate networks, Sci Signal 6(275) (2013) rs10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Li Y, Sheftic SR, Grigoriu S, Schwieters CD, Page R, Peti W, The structure of the RCAN1:CN complex explains the inhibition of and substrate recruitment by calcineurin, Sci Adv 6(27) (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].St-Denis N, Gupta GD, Lin ZY, Gonzalez-Badillo B, Veri AO, Knight JDR, Rajendran D, Couzens AL, Currie KW, Tkach JM, Cheung SWT, Pelletier L, Gingras AC, Phenotypic and Interaction Profiling of the Human Phosphatases Identifies Diverse Mitotic Regulators, Cell Rep 17(9) (2016) 2488–2501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Roux KJ, Kim DI, Raida M, Burke B, A promiscuous biotin ligase fusion protein identifies proximal and interacting proteins in mammalian cells, J Cell Biol 196(6) (2012) 801–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Han Y, Branon TC, Martell JD, Boassa D, Shechner D, Ellisman MH, Ting A, Directed Evolution of Split APEX2 Peroxidase, ACS Chem Biol 14(4) (2019) 619–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Cho KF, Branon TC, Rajeev S, Svinkina T, Udeshi ND, Thoudam T, Kwak C, Rhee HW, Lee IK, Carr SA, Ting AY, Split-TurboID enables contact-dependent proximity labeling in cells, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117(22) (2020) 12143–12154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Tsekitsidou E, Wang JT, Wong CJ, Ulengin-Talkish I, Stearns T, Gingras A-C, Cyert MS, Calcineurin associates with centrosomes and regulates cilia length maintenance, bioRxiv (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Hendus-Altenburger R, Lambrughi M, Terkelsen T, Pedersen SF, Papaleo E, Lindorff-Larsen K, Kragelund BB, A phosphorylation-motif for tuneable helix stabilisation in intrinsically disordered proteins - Lessons from the sodium proton exchanger 1 (NHE1), Cell Signal 37 (2017) 40–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Hisamitsu T, Nakamura TY, Wakabayashi S, Na(+)/H(+) exchanger 1 directly binds to calcineurin A and activates downstream NFAT signaling, leading to cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, Mol Cell Biol 32(16) (2012) 3265–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Enyedi P, Czirjak G, Properties, regulation, pharmacology, and functions of the K(2)p channel, TRESK, Pflugers Arch 467(5) (2015) 945–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Tulleuda A, Cokic B, Callejo G, Saiani B, Serra J, Gasull X, TRESK channel contribution to nociceptive sensory neurons excitability: modulation by nerve injury, Mol Pain 7 (2011) 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Zhou J, Lin W, Chen H, Fan Y, Yang C, TRESK contributes to pain threshold changes by mediating apoptosis via MAPK pathway in the spinal cord, Neuroscience 339 (2016) 622–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Czirjak G, Enyedi P, The LQLP calcineurin docking site is a major determinant of the calcium-dependent activation of human TRESK background K+ channel, J Biol Chem 289(43) (2014) 29506–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Czirjak G, Enyedi P, Targeting of calcineurin to an NFAT-like docking site is required for the calcium-dependent activation of the background K+ channel, TRESK, J Biol Chem 281(21) (2006) 14677–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Lengyel M, Hajdu D, Dobolyi A, Rosta J, Czirjak G, Dux M, Enyedi P, TRESK background potassium channel modifies the TRPV1-mediated nociceptor excitability in sensory neurons, Cephalalgia 41(7) (2021) 827–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Por ED, Samelson BK, Belugin S, Akopian AN, Scott JD, Jeske NA, PP2B/calcineurin-mediated desensitization of TRPV1 does not require AKAP150, Biochem J 432(3) (2010) 549–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Julius D, TRP channels and pain, Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 29 (2013) 355–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Btesh J, Fischer MJM, Stott K, McNaughton PA, Mapping the binding site of TRPV1 on AKAP79: implications for inflammatory hyperalgesia, J Neurosci 33(21) (2013) 9184–9193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Huang Y, Chen SR, Pan HL, Calcineurin Regulates Synaptic Plasticity and Nociceptive Transmissionat the Spinal Cord Level, Neuroscientist (2021) 10738584211046888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Todorovic SM, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Targeting of CaV3.2 T-type calcium channels in peripheral sensory neurons for the treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy, Pflugers Arch 466(4) (2014) 701–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Huang CH, Chen YC, Chen CC, Physical interaction between calcineurin and Cav3.2 T-type Ca2+ channel modulates their functions, FEBS Lett 587(12) (2013) 1723–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Orie NN, Thomas AM, Perrino BA, Tinker A, Clapp LH, Ca2+/calcineurin regulation of cloned vascular K ATP channels: crosstalk with the protein kinase A pathway, Br J Pharmacol 157(4) (2009) 554–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Schreiber JA, Seebohm G, Cardiac K(+) Channels and Channelopathies, Handb Exp Pharmacol 267 (2021) 113–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Maillet M, Davis J, Auger-Messier M, York A, Osinska H, Piquereau J, Lorenz JN, Robbins J, Ventura-Clapier R, Molkentin JD, Heart-specific deletion of CnB1 reveals multiple mechanisms whereby calcineurin regulates cardiac growth and function, J Biol Chem 285(9) (2010) 6716–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Perino A, Ghigo A, Scott JD, Hirsch E, Anchoring proteins as regulators of signaling pathways, Circ Res 111(4) (2012) 482–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Patel N, Stengel F, Aebersold R, Gold MG, Molecular basis of AKAP79 regulation by calmodulin, Nat Commun 8(1) (2017) 1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Li H, Pink MD, Murphy JG, Stein A, Dell’Acqua ML, Hogan PG, Balanced interactions of calcineurin with AKAP79 regulate Ca2+-calcineurin-NFAT signaling, Nat Struct Mol Biol 19(3) (2012) 337–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Nygren PJ, Mehta S, Schweppe DK, Langeberg LK, Whiting JL, Weisbrod CR, Bruce JE, Zhang J, Veesler D, Scott JD, Intrinsic disorder within AKAP79 fine-tunes anchored phosphatase activity toward substrates and drug sensitivity, Elife 6 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Watson M, Almeida TB, Ray A, Hanack C, Elston R, Btesh J, McNaughton PA, Stott K, Hidden Multivalency in Phosphatase Recruitment by a Disordered AKAP Scaffold, J Mol Biol 434(16) (2022) 167682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Hinke SA, Navedo MF, Ulman A, Whiting JL, Nygren PJ, Tian G, Jimenez-Caliani AJ, Langeberg LK, Cirulli V, Tengholm A, Dell’Acqua ML, Santana LF, Scott JD, Anchored phosphatases modulate glucose homeostasis, EMBO J 31(20) (2012) 3991–4004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Jiang H, Xiong F, Kong S, Ogawa T, Kobayashi M, Liu JO, Distinct tissue and cellular distribution of two major isoforms of calcineurin, Mol Immunol 34(8–9) (1997) 663–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Saraf J, Bhattacharya P, Kalia K, Borah A, Sarmah D, Kaur H, Dave KR, Yavagal DR, A Friend or Foe: Calcineurin across the Gamut of Neurological Disorders, ACS Cent Sci 4(7) (2018) 805–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Chen L, Song M, Yao C, Calcineurin in development and disease, Genes Dis 9(4) (2022) 915–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Woolfrey KM, Dell’Acqua ML, Coordination of Protein Phosphorylation and Dephosphorylation in Synaptic Plasticity, J Biol Chem 290(48) (2015) 28604–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Purkey AM, Dell’Acqua ML, Phosphorylation-Dependent Regulation of Ca(2+)-Permeable AMPA Receptors During Hippocampal Synaptic Plasticity, Front Synaptic Neurosci 12 (2020) 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Purkey AM, Woolfrey KM, Crosby KC, Stich DG, Chick WS, Aoto J, Dell’Acqua ML, AKAP150 Palmitoylation Regulates Synaptic Incorporation of Ca(2+)-Permeable AMPA Receptors to Control LTP, Cell Rep 25(4) (2018) 974–987 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Sanderson JL, Freund RK, Gorski JA, Dell’Acqua ML, beta-Amyloid disruption of LTP/LTD balance is mediated by AKAP150-anchored PKA and Calcineurin regulation of Ca(2+)-permeable AMPA receptors, Cell Rep 37(1) (2021) 109786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Oliveria SF, Dell’Acqua ML, Sather WA, AKAP79/150 anchoring of calcineurin controls neuronal L-type Ca2+ channel activity and nuclear signaling, Neuron 55(2) (2007) 261–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Oliveria SF, Dittmer PJ, Youn DH, Dell’Acqua ML, Sather WA, Localized calcineurin confers Ca2+-dependent inactivation on neuronal L-type Ca2+ channels, J Neurosci 32(44) (2012) 15328–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Murphy JG, Crosby KC, Dittmer PJ, Sather WA, Dell’Acqua ML, AKAP79/150 recruits the transcription factor NFAT to regulate signaling to the nucleus by neuronal L-type Ca(2+) channels, Mol Biol Cell 30(14) (2019) 1743–1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Wild AR, Sinnen BL, Dittmer PJ, Kennedy MJ, Sather WA, Dell’Acqua ML, Synapse-to-Nucleus Communication through NFAT Is Mediated by L-type Ca(2+) Channel Ca(2+) Spike Propagation to the Soma, Cell Rep 26(13) (2019) 3537–3550 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Lewis RS, Store-Operated Calcium Channels: From Function to Structure and Back Again, Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 12(5) (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Feske S, Gwack Y, Prakriya M, Srikanth S, Puppel SH, Tanasa B, Hogan PG, Lewis RS, Daly M, Rao A, A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function, Nature 441(7090) (2006) 179–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Kar P, Samanta K, Kramer H, Morris O, Bakowski D, Parekh AB, Dynamic assembly of a membrane signaling complex enables selective activation of NFAT by Orai1, Curr Biol 24(12) (2014) 1361–1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Kar P, Lin YP, Bhardwaj R, Tucker CJ, Bird GS, Hediger MA, Monico C, Amin N, Parekh AB, The N terminus of Orai1 couples to the AKAP79 signaling complex to drive NFAT1 activation by local Ca(2+) entry, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 118(19) (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Baskin JM, Wu X, Christiano R, Oh MS, Schauder CM, Gazzerro E, Messa M, Baldassari S, Assereto S, Biancheri R, Zara F, Minetti C, Raimondi A, Simons M, Walther TC, Reinisch KM, De Camilli P, The leukodystrophy protein FAM126A (hyccin) regulates PtdIns(4)P synthesis at the plasma membrane, Nat Cell Biol 18(1) (2016) 132–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Dornan GL, Dalwadi U, Hamelin DJ, Hoffmann RM, Yip CK, Burke JE, Probing the Architecture, Dynamics, and Inhibition of the PI4KIIIalpha/TTC7/FAM126 Complex, J Mol Biol 430(18 Pt B) (2018) 3129–3142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Balla A, Kim YJ, Varnai P, Szentpetery Z, Knight Z, Shokat KM, Balla T, Maintenance of hormone-sensitive phosphoinositide pools in the plasma membrane requires phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase IIIalpha, Mol Biol Cell 19(2) (2008) 711–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Toth JT, Gulyas G, Toth DJ, Balla A, Hammond GR, Hunyady L, Balla T, Varnai P, BRET-monitoring of the dynamic changes of inositol lipid pools in living cells reveals a PKC-dependent PtdIns4P increase upon EGF and M3 receptor activation, Biochim Biophys Acta 1861(3) (2016) 177–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Morgan AJ, Platt FM, Lloyd-Evans E, Galione A, Molecular mechanisms of endolysosomal Ca2+ signalling in health and disease, Biochem J 439(3) (2011) 349–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Yang Z, Kirton HM, MacDougall DA, Boyle JP, Deuchars J, Frater B, Ponnambalam S, Hardy ME, White E, Calaghan SC, Peers C, Steele DS, The Golgi apparatus is a functionally distinct Ca2+ store regulated by the PKA and Epac branches of the beta1-adrenergic signaling pathway, Sci Signal 8(398) (2015) ra101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Gomez-Salinero JM, Lopez-Olaneta MM, Ortiz-Sanchez P, Larrasa-Alonso J, Gatto A, Felkin LE, Barton PJR, Navarro-Lerida I, Angel Del Pozo M, Garcia-Pavia P, Sundararaman B, Giovinazo G, Yeo GW, Lara-Pezzi E, The Calcineurin Variant CnAbeta1 Controls Mouse Embryonic Stem Cell Differentiation by Directing mTORC2 Membrane Localization and Activation, Cell Chem Biol 23(11) (2016) 1372–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Medina DL, Di Paola S, Peluso I, Armani A, De Stefani D, Venditti R, Montefusco S, Scotto-Rosato A, Prezioso C, Forrester A, Settembre C, Wang W, Gao Q, Xu H, Sandri M, Rizzuto R, De Matteis MA, Ballabio A, Lysosomal calcium signalling regulates autophagy through calcineurin and TFEB, Nat Cell Biol 17(3) (2015) 288–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Puertollano R, Ferguson SM, Brugarolas J, Ballabio A, The complex relationship between TFEB transcription factor phosphorylation and subcellular localization, EMBO J 37(11) (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Cheung G, Cousin MA, Synaptic vesicle generation from activity-dependent bulk endosomes requires a dephosphorylation-dependent dynamin-syndapin interaction, J Neurochem 151(5) (2019) 570–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Cheung G, Cousin MA, Synaptic vesicle generation from activity-dependent bulk endosomes requires calcium and calcineurin, J Neurosci 33(8) (2013) 3370–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Clayton EL, Cousin MA, The molecular physiology of activity-dependent bulk endocytosis of synaptic vesicles, J Neurochem 111(4) (2009) 901–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Peng YJ, Geng J, Wu Y, Pinales C, Langen J, Chang YC, Buser C, Chang KT, Minibrain kinase and calcineurin coordinate activity-dependent bulk endocytosis through synaptojanin, J Cell Biol 220(12) (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Flannagan RS, Jaumouille V, Grinstein S, The cell biology of phagocytosis, Annu Rev Pathol 7 (2012) 61–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Scaramuzzino C, Cuoc EC, Pla P, Humbert S, Saudou F, Calcineurin and huntingtin form a calcium-sensing machinery that directs neurotrophic signals to the nucleus, Sci Adv 8(1) (2022) eabj8812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Ehinger Y, Bruyere J, Panayotis N, Abada YS, Borloz E, Matagne V, Scaramuzzino C, Vitet H, Delatour B, Saidi L, Villard L, Saudou F, Roux JC, Huntingtin phosphorylation governs BDNF homeostasis and improves the phenotype of Mecp2 knockout mice, EMBO Mol Med 12(2) (2020) e10889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Nunnari J, Suomalainen A, Mitochondria: in sickness and in health, Cell 148(6) (2012) 1145–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]