Abstract

Increases in the copy number of large genomic regions, termed genome amplification, are an important adaptive strategy for malaria parasites. Numerous amplifications across the Plasmodium falciparum genome contribute directly to drug resistance or impact the fitness of this protozoan parasite. During the characterization of parasite lines with amplifications of the dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) gene, we detected increased copies of an additional genomic region that encompassed 3 genes (~5 kb) including GTP cyclohydrolase I (GCH1 amplicon). While this gene is reported to increase the fitness of antifolate resistant parasites, GCH1 amplicons had not previously been implicated in any other antimalarial resistance context. Here, we further explored the association between GCH1 and DHODH copy number. Using long read sequencing and single read visualization, we directly observed a higher number of tandem GCH1 amplicons in parasites with increased DHODH copies (up to 9 amplicons) compared to parental parasites (3 amplicons). While all GCH1 amplicons shared a consistent structure, expansions arose in 2-unit steps (from 3 to 5 to 7, etc copies). Adaptive evolution of DHODH and GCH1 loci was further bolstered when we evaluated prior selection experiments; DHODH amplification was only successful in parasite lines with pre-existing GCH1 amplicons. These observations, combined with the direct connection between metabolic pathways that contain these enzymes, lead us to propose that the GCH1 locus is beneficial for the fitness of parasites exposed to DHODH inhibitors. This finding highlights the importance of studying variation within individual parasite genomes as well as biochemical connections of drug targets as novel antimalarials move towards clinical approval.

Author Summary

Malaria is caused by a protozoan parasite that readily evolves resistance to drugs that are used to treat this deadly disease. Changes that arise in the parasite genome, including extra copies of important genes, directly contribute to this resistance or improve how well the resistant parasite competes. In this study, we identified that extra copies of one gene (GTP cyclohydrolase or GCH1) were more likely to be found in parasites with extra copies of another gene on a different chromosome (dihydroorotate dehydrogenase or DHODH). A method that allows us to view long pieces of DNA from individual genomes was especially important for this study; we were able to assess gene number, arrangement, and boundary sequences, which provided clues into how extra copies evolved. Additionally, by analyzing previous experiments, we identified that extra GCH1 copies improved resistance to drugs that target DHODH. The relationship between these two loci is supported by a direct connection between the folate and pyrimidine biosynthesis pathways that the parasite uses to make DNA. Since GCH1 amplicons are common in clinical parasites worldwide, this finding highlights the need to study metabolic connections to avoid resistance evolution.

Introduction

Malaria is a disease caused by the protozoan Plasmodium parasite and P. falciparum is the leading cause of human malaria deaths (1). Due to the lack of effective vaccines against malaria infection, antimalarial drugs are the primary approach for malaria treatment (2). However, drug efficacy is mitigated by the frequent emergence of antimalarial resistant parasites (3).

Changes in the copy number of large genomic regions, termed copy number variations or CNVs, are an important adaptive strategy for malaria parasites (4–12). Amplification, one type of CNV with increased gene copy number, plays an essential role in the evolution of resistance to various antimalarials (6,7,9,11,13–16). As one example, amplification of the dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) gene directly confers resistance to DHODH inhibitors (i.e. DSM1) in parasites propagated in vitro (11). DHODH is an important enzyme in the P. falciparum pyrimidine biosynthesis pathway that contributes resources for nucleic acid synthesis (17,18). DHODH amplicons increase transcription and presumably translation of the drug target to directly impact drug sensitivity (11).

In another example, amplification of the GTP cyclohydrolase 1 (GCH1) gene increases the fitness of clinical parasite populations that are resistant to antifolates (i.e. pyrimethamine and sulfadoxine) (4,7,8,16). GCH1 is the first enzyme in the folate biosynthesis pathway and increased flux through this pathway compensates for fitness costs of resistance-conferring mutations in dihydropteroate synthase (DHPS) and dihydrofolate synthase (DHFS) genes (4,8,15). Although the contribution of GCH1 amplicons to antifolate resistance is well studied, this locus has not been reported to contribute to resistance to other antimalarials (15,19,20).

Typically, gene copy number is studied using widely accessible high coverage short read sequencing (11,21–24). However, this approach has limitations including non-unique mapping of repetitive sequences, the inability to resolve complex genomic rearrangements, and the overall difficulty of detecting structural variations (25–27). These challenges are exacerbated by the high AT-content of the P. falciparum genome (28,29). Long read technologies such as Oxford Nanopore sequencing have the potential to span low complexity and repetitive regions and more accurately represent structural variation (Cretu Stancu et al., 2017; Sedlazeck et al., 2018a, 2018b; Ho et al., 2020). Moreover, this single molecule sequencing approach allows the examination of clonal heterogeneity within cellular populations (34,35).

In this study, we identified an unprecedented association between GCH1 and DHODH copy numbers from a previously acquired short read data set. To explore this relationship further, we performed long read sequencing and directly observed the step-wise expansion of the GCH1 amplicon in parasites with elevated DHODH copies. Using single long read visualization, we determined that the structure and orientation of the amplicon were preserved during expansion and amplicons increased in a step-wise manner. The positive correlation between GCH1 and DHODH copy number presented here, combined with the recognition that resistance to DHODH inhibitors has only been selected in parasite lines with GCH1 expansions, suggest the adaptive evolution of these two genomic loci. In addition, the direct connection between folate and pyrimidine biosynthesis supports metabolic interplay between the two pathways. Further study of this relationship is important considering the potential use of DHODH inhibitors to treat clinical malaria with preexisting GCH1 amplicons.

Results

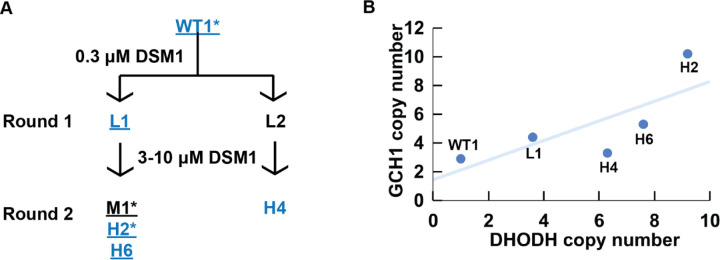

Through expanded analysis of short read data from a family of parasites selected with DSM1, originally presented in (11) (Figure 1A), we observed a positive association between GCH1 and DHODH copy number (Figure 1B). Using droplet digital PCR on the same parasite lines that had recently been propagated in our laboratory, we confirmed that GCH1 copy number trended higher as DHODH copy number increased (Table 1).

Fig 1. GCH1 copy number increase is positively correlated with DHODH copy number in one family of DSM1 selected parasites.

(A) DSM1 selection schematic, as presented previously (11). Blue text: Illumina short read sequenced lines. Underline: modern lines confirmed by ddPCR analysis (Table 1). Asterisk (*): lines subjected to long read sequencing in this study. Wild-type (WT1, Dd2) P. falciparum was selected with DSM1 in two steps; the first step selected for low-level (L) resistance and the second step selected for moderate- (M) or high-level (H) resistance. DSM1 EC50 values are as follows: L1 (1 μM), L2 (0.9 μM), M1 (7.2 μM), H2 (85 μM), H6 (56 μM), H4 (49 μM). All values were previously reported and clone names were adapted as previously (11,36). (B) Relationship between GCH1 and DHODH copy number in DSM1 selected parasites as quantified using short read data from Guler et al. 2013. A trend line was added to show the relationship between GCH1 and DHODH copy numbers but a correlation coefficient could not be calculated due to the small sample size (n=5) and dependence among the lines.

Table 1.

Positive GCH1:DHODH association is validated using Droplet Digital PCR on modern parasite lines.

| Line | Sample type | Average copy number (SD)* | GCH1 CN relative to parent | DHODH CN relative to parent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GCH1 | DHODH | ATP6 | ||||

| WT1 | Parent | 2.5 (0.2) | 0.8 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.0) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| L1 | Round 1 selection | 3.9 (0.3) | 3.2 (0.1) | 1.0 (0.1) | 1.6 | 4 |

| M1 | Round 1 selection | 3.9 (0.1) | 5.2 (0.3) | 1.0 (0.1) | 1.6 | 6.5 |

| H2 | Round 2 selection | 4.6 (0.2) | 6.0 (0.3) | 1.1 (0.1) | 1.8 | 7.5 |

| H6 | Round 2 selection | 4.3 (0.3) | 7.0 (0.4) | 1.0 (0.1) | 1.7 | 8.8 |

The average copy number is calculated by comparing the ddPCR signal to a single copy gene signal (Seryl tRNA synthetase, PF3D7_0717700). N=4. ATP6 copy number is a single copy gene expected to be 1 in all parasite lines.

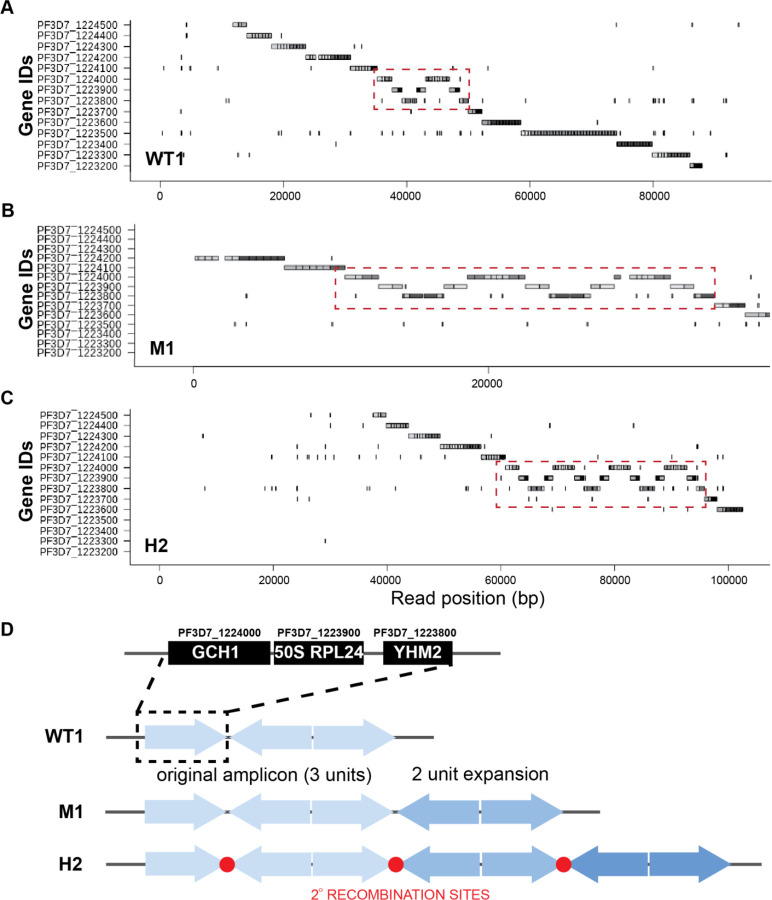

We conducted long read sequencing to more precisely define GCH1 copy number and amplicon structure in the parental line versus two DSM1-selected lines (WT1, M1, and H2, Table S1). We directly visualized single reads using an application that represents gene segments of individual long reads (Materials and Methods). Small amplicons, like those including GCH1, are especially conducive to this approach because long reads span multiple copies of the amplicon as well as both up and downstream regions. Read visualization showed that the general structure of two 3-gene amplicons, separated by an inversion of the same 3-genes, was conserved between the parental and selected lines (Figure 2A–C). This amplicon structure was reported previously in the WT1 (Dd2) parental line (Figure 2D) (4).

Fig 2. Long-read visualization shows conserved boundaries and structure of GCH1 amplicon from parental and resistance parasites.

(A-C) Representative images from the Shiny application comparing the GCH1 amplicon in WT1 (A), M1 (B), and H2 (C) spanning reads. Red dashed square: copies of GCH1 amplicon covering 3 genes. Each gene sequence from the 3D7 reference genome (no GCH1 amplicon represented) was split into <=500 bp fragments and blasted against individual Nanopore reads (dark gray: genic regions, light grey: intergenic regions, more details in Materials and Methods). (D) Orientation of GCH1 amplicons from each parasite line. The three genes within the GCH1 amplicon unit include PF3D7_1224000 (GTP cyclohydrolase I, GCH1), PF3D7_1223900 (50S ribosomal protein L24, putative, 50S RPL24), and PF3D7_1223800 (citrate/oxoglutarate carrier protein, putative, YHM2). Note: The gene order (GCH1–50S RPL24-YHM2) is reversed compared to the 3D7 reference genome (YHM2–50S RPL24-GCH1) in order to facilitate comparison with the read images in panels A-C. Red circles: amplicon junction sequences that act as potential secondary recombination sites.

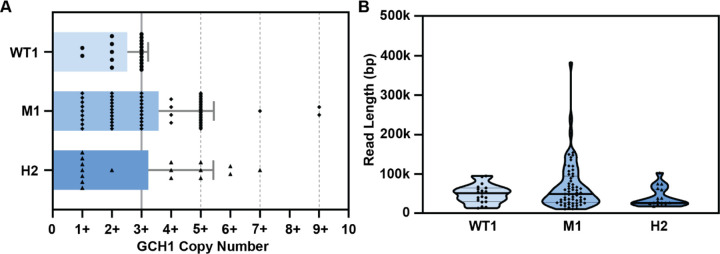

Using direct read visualization, we also recorded the number of GCH1 amplicon units (Figure 2D) from both spanning and non-spanning reads (Figure 3A, Table S2) Spanning reads cover genes both upstream and downstream of the amplicon while non-spanning reads end within the amplicon. We consistently detected up to 3 amplicon units on reads from the parental line. Although the overall mean copy number was similar for all parasite lines (Figure 3A, WT1, 2.5 copies; M1, 3.6 copies; H2; 3.2 copies, F(2,95)=[2.61], p = 0.07), we observed more reads that encompassed a higher number of GCH1 amplicon units in the selected lines (up to 9 units, Figure 3A). When we restricted our analysis to spanning reads, or those that displayed the entire amplified region, we detected a significant difference in mean copy number between the parasite lines (WT1 vs M1, p=0.0003 and WT1 vs H2, p=0.01; Figure S1). The presence of longer reads was not contributing to this observation; there was not a significant difference in the length of reads used for GCH1 analysis from each parasite line (F(2,96)=[2.51], p = 0.09, Figure 3B, median read lengths: WT1, 51144bp; M1, 49018bp; H2, 26429bp). The larger variation observed for the M1 sample (Figure 3B) was due to an improvement in ONT technology and methods leading to an increase in the number of longer reads (i.e. WT1 N50 of 15.6kb on R9.4.1 flow cell and M1 N50 of 99.7kb on R10.4.1 flow cell, Table S1, see Materials and Methods).

Fig 3. Quantification of long reads displays an increase in GCH1 amplicon number in DSM1 selected parasites that is not dependent on overall read length.

(A) GCH1 copy number from WT1 and selected (M1 and H2) parasite lines. Spanning and non-spanning reads are included; spanning reads were grouped with their corresponding non-spanning count (e.g. a read showing 2 copies of the GCH1 amplicon is counted as a 2+ read). Bars represent mean, error bars represent standard deviation (dotted lines, values that represent detected spanning reads, see Figure S1). (B) Read length distribution from long reads (>=10kb) covering the GCH1 amplicon. Thick line represents median, thin line represents quartiles.

During this analysis, we identified that >50% of reads from M1 and H2 lines depicted amplicon copy numbers greater than the expected WT copy number (Figure 3A, Table S2). To assess whether variation in the copy number of the GCH1 locus was common in other laboratory-adapted parasite lines, we evaluated several additional long read datasets (Table S2, Supporting Information, Vembar et al., 2016). In general, parasite lines exhibited the expected GCH1 amplicon size (i.e. Dd2 versus 3D7, as reported previously (4) and visualized in Figures 2D and S2) and the amplicon copy number for each line was relatively stable across diverse datasets (limited to <25% of reads above the expected copy number).

When we evaluated the amplicon structure, all M1 and H2 reads covering the GCH1 region began with a set of 3 amplicon units, as observed in the parental line (Figure 2A). This basic structure was followed by groups of 2 units, where one copy was inverted and the other was in normal orientation (Figure 2D). This suggests that increases in copy number were arising as two unit steps. We identified further evidence of the two unit amplicon expansion when we limited our analysis to only spanning reads, which allow direct quantification of amplicon copy number. Here, we did not detect any spanning reads that carried even GCH1 copy numbers (only 3, 5, 7, or 9 copies, Figure S1).

To investigate whether an increase in GCH1 amplicons was contributing generally to resistance to DHODH inhibitors, we evaluated the copy number of GCH1 amplicons using short read data collected from parasites selected with other DSM compounds in two studies (18,37). Contrary to DSM1-selected parasites (Figure 1B), we did not detect increases in GCH1 amplicon number in parasites selected with DSM265, DSM267, or DSM705 compared to parental Dd2 or 3D7 parasite lines (Figure S3, Table S3). For this analysis, we only included parasite lines that acquired DHODH amplicons to confer resistance.

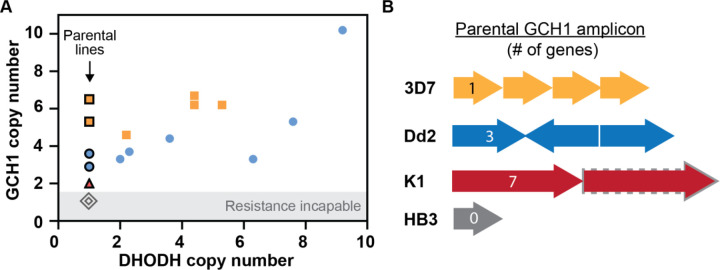

The absence of a correlation between DHODH and GCH1 copy number in these other datasets suggests that GCH1 may not play a direct role in resistance. However, parental lines used in these two studies harbored pre-existing GCH1 amplicons (~3–6 copies, Figure 4A), indicating that this locus may support the evolution of resistance involving DHODH amplification. Therefore, we compiled information on all previous resistance selections conducted in parasite lines that naturally vary in GCH1 copy number (7 total studies, Table 2). 3D7 and Dd2 parasite lines, which carry the highest GCH1 copy numbers (3–6 copies) with the smallest overall amplicon sizes of common laboratory parasites (1 and 3 genes, respectively, Figure 4B), were most commonly used in successful resistance selections (6 and 4 studies, respectively, Table 2) and were capable of acquiring DHODH amplicons (Figure 4A). K1 parasites harbor a larger low copy GCH1 amplicon (anticipated as 2 copies of 7 genes, Figure 4B) and although resistance could be selected in one study, it was 1000-fold less efficient than Dd2 selections run in parallel (38). The DHODH copy number status of this K1-derived selected line was not investigated. Finally, Hb3, which harbors one GCH1 copy (Table 2, Figure 4B), was incapable of developing resistance in two independent studies (11,38) (Figure 4A).

Fig 4. Preexisting GCH1 amplicons confer resistance competence.

(A) Relationship between GCH1 and DHODH copy number in parental (black outline) and DHODH inhibitor-selected parasite lines as quantified using short read data (see Table 2 for source data). Each data point represents a copy number from an individual parasite clone or line from a distinct selection (see Tables S3 and S4 for copy number assessment). 3D7, yellow squares (2 selections); Dd2, blue circles (2 selections); K1, red triangle (1 selection, unknown DHODH copy number post-selection); HB3, grey diamonds (2 selections). (B) GCH1 amplicon size and gene number vary between parasite lines used for DHODH inhibitor selections (see Table 2 for selection details). 3D7, 4 copy, single gene (PF3D7_1224000, 2kb, this study); Dd2, 3 copy, three genes (PF3D7_1223800- PF3D7_1224000, 5kb, this study); K1, unknown copy number (grey dash, anticipated 2 copy), 7 genes (PF3D7_1223500 - PF3D7_1224100, 19kb) (39); HB3, 1 copy of region (40).

Table 2.

Parental line GCH1 copy number determines resistance competence

| Study (author, year) | Selection Compounds | Success of Resistance Selection | DHODH amplicon | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dd2 (GCH1=3) | 3D7 (GCH1=4–6) | Hb3 (GCH1=1*) | Other lines | |||

| Guler, 2013 (11) | DSM1 | Yes | N/A | No | N/A | Yes |

| Palmer, 2021 (37) | DSM705 | Yes | Yes | N/A | N/A | Yes |

| Phillips. 2015 (38) | DSM265 | Yes | N/A | No | K1-Yes** | Yes |

| Mandt, 2019 (18) | DSM265, DSM267 | Yes | Yes | N/A | N/A | ^Yes |

| White, 2019 (41) | DSM265 | Yes | N/A | N/A | N/A | No |

| Ross, 2014 (42) | DSM74 | Yes | Yes | N/A | N/A | No |

| Lukens, 2014 (43) | Genz-666136, DSM74 | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | No |

The GCH1 copy number for the HB3 parasite line is single copy based on whole genome sequencing (40). Prior studies detected two GCH1 copies using quantitative PCR but did not detect an increase in expression from this region (8,15).

The K1 parasite line has a GCH1 amplicon that is ~19kb (961,455–980,630, (39)) but the exact copy number has not been reported. Phillips et al. reported that it was 100x more difficult to select for DSM265 resistance using K1 than Dd2 (MIR- 2 × 10^8 versus 2 × 10^6, respectively, (38). Resistance mechanisms (i.e. mutation or amplification) were not evaluated for the resistant K1 line in this study.

Discussion

Using both short-read sequencing as well as an accurate PCR-based method, ddPCR, we uncovered that GCH1 copy number is positively associated with DHODH copy number in malaria parasites selected with DSM1 (Figures 1B and 4, Table 1). However, limitations in each of these methods contribute to inaccuracies in copy number results. Most importantly, both of these methods provide an average value for the parasite population and do not reflect variation from individual genomes. Long-read sequencing combined with a custom visualization tool (44) allowed us to directly quantify the copy number of the GCH1 locus and assess the structure of all amplicons (Figures 2 and 3). In the context of this haploid, single cellular parasite, each read represents a distinct DNA strand from a single genome; this approach is an accurate way to visualize copy number and junction heterogeneity across a population (Figure 2, Figure S2). We showed that the detection of more GCH1 amplicons on reads from DSM1 selected parasite lines (Figure 3A) was not caused by sample preparation (Figure 3B, Table S2) or natural variation during in vitro culture (Table S2). The visualization of tandem amplicons on single reads (Figure 2A–C) and the step-wise increase by 2 amplicon units (from 3 to 5 to 7 copies, Figures 2D and S1) provides direct evidence for GCH1 amplicon expansion in the DSM1 resistance context.

The two-unit steps suggest that there is a secondary recombination site that leads to facile re-amplification of the region (Figure 2D). In the high coverage M1 sample, we identified long AT-rich sequences at the end of the amplicon unit (Figure S4) that may participate in further DNA breakage (AT dinucleotides at the GCH1 end, Figure S4C) and recombination after the initial event (homopolymeric A/T tracks at the YHM2 end, Figure S4A)(24). Multiple junctions at these positions provide evidence of the initial event that formed the 3 unit amplicon as well as a secondary event resulting in a two-unit step-wise expansion.

As recently recognized in organisms from bacteria to humans (34,35,45–47), long read sequencing is an exceptional tool to investigate genomic heterogeneity within populations. This method is not without its limitations; reads that end within the amplicon region lead to an underestimation in the total copy number; in our study, 65/98 (66%) of reads were non-spanning, which contributed to a similar overall mean copy number between parasite lines (Figure 3A). However, the visualization of spanning reads overcame this limitation, clearly showing the two-unit expansion of GCH1 amplicons (Figures 2A–C and S1). The quantification of spanning reads also confirms that variation in GCH1 amplicon numbers likely arises stochastically in the parasite population; while most spanning reads from the high coverage M1 line showed 5 amplicon copies (15/21 reads), we observed higher amplicon copies on a minority of reads (7 and 9 copies, 3/21 reads). In line with our previous model for malaria genome evolution (11,24), parasites with higher copy numbers are present within the population, poised to be selected under specific conditions.

The GCH1 locus is a proven hotspot for genetic change (8,39). GCH1 amplicons have previously been associated with antifolate resistance; an increase in flux through the folate biosynthesis pathway via GCH1 alleviates fitness effects of mutations that confer pyrimethamine and sulfadoxine resistance (4,8,16,19,20). A similar contribution to resistance to DHODH inhibitors would not be surprising, given the close connection of the folate and pyrimidine biosynthesis pathways (Figure 5); they both contribute to nucleotide biosynthesis and converting dUMP to dTMP in pyrimidine biosynthesis requires reciprocal conversion of N5, N10-methylene-THF to DHF by the folate pathway. Strong evidence for this metabolic connection comes from the observation that parasite lines without GCH1 amplicons are not able to develop resistance to DHODH inhibitors (Table 2) (11,38). Assessment of resistance competence, combined with our observations in the DSM1 context and folate-pyrimidine metabolic interplay, lead us to propose that increases in GCH1 copy number are also beneficial for the fitness of parasites carrying DHODH amplicons. During resistance evolution, increased DHODH protein levels interact with more of the inhibitor to cause resistance. When the inhibitor is not present, higher DHODH levels increase flux through pyrimidine biosynthesis, which in turn requires more THF for the completion of the pathway (Figure 5).

Fig 5. The connection between pyrimidine and folate biosynthesis pathways.

Enzymes with gene copy number variations are indicated in blue text (DHODH: dihydroorotate dehydrogenase; GCH1: GTP cyclohydrolase 1) and connections between the two pathways in blue arrows. Gln: Glutamine; DHO: Dihydroorotate; UMP: Uridine monophosphate; dUMP: Deoxyuridine monophosphate; dTMP: deoxythymidine monophosphate; GTP: Guanosine-5’-triphosphate; DHPS: Dihydropteroate synthase; DHFR: Dihydrofolate reductase; DHF: Dihydrofolate; THF: Tetrahydrofolate; HMDP-P2: 6-hydroxymethyl-7, 8-dihydropterin diphosphate; pABA: para-amino-benzoic acid; 5, 10-CH2-THF: 5,10-Methylenetetrahydrofolate. *Dd2 carries 3 mutations in both DHPS and DHFR (6 total) and HB3 and 3D7 have a single mutation each in DHFR and DHPS, respectively (15,48).

There are a few factors that may impact parasite reliance on folate biosynthesis including parasite genetic background and the presence of folate precursors in the host environment. Antifolate resistant parasites from different regions of the world that harbor specific mutations rely more heavily on increased GCH1 flux to alleviate fitness effects (i.e. DHFR and DHPS mutants, (4,8,15,19), Figure 5). While Dd2 and 3D7 have distinct origins and mutational patterns (49,50) (Figure 5), the fact that they both maintain the ability to develop DHODH inhibitor resistance excludes the possibility that DHFR and DHPS mutations matter in this context. Additionally, levels of folate precursors, such as para-aminobenzoic acid (pABA), vary widely in host versus in vitro environments (51–55) and exert different selective pressures on parasites during drug selection (56). Higher pABA levels in human serum, as were used during DSM1 selections (11), may drive the accumulation of higher GCH1 copy numbers and hold extra benefits by bolstering both folate and pyrimidine biosynthesis (Figure 5). Our observation of some level of variation in GCH1 amplicon number in standard parasite lines (Table S2) suggests that differing in vitro media formulations may drive copy number changes at this locus.

Importantly, DHODH inhibitors have entered trials for the treatment of clinical malaria (18) and resistance-conferring DHODH amplicons can evolve in vivo (57). Meanwhile, antifolate resistance and GCH1 amplifications are widespread in clinical P. falciparum isolates, especially in Southeast Asia (4,7,8,39) and now Africa (16,58). Additionally, a zoonotic malaria species, P. knowlesi, also acquires extra GCH1 copies after adaptation to human blood (59). The potential use of DHODH inhibitors on clinical parasites carrying GCH1 amplicons necessitates further evaluation of the interplay between these two important metabolic pathways.

Materials and Methods

DSM1 and parasite clones

DSM1 inhibits dihydroorotate dehydrogenase enzyme of Plasmodium pyrimidine biosynthesis (60). DSM1-resistant parasites were selected during a previous study and cloned by limiting dilution at the time of isolation (11) (Figure 1A). The naming scheme representing low (L), moderate (M), and high (H) levels of DSM1 resistance follows that used previously by our group (36).

Parasite culture

We thawed erythrocytic stages of P. falciparum (Dd2, MRA-150; 3D7, MRA-102, Malaria Research and Reference Reagent Resource Center, BEI Resources and DSM1 selected clones as highlighted in Figure 1A, a generous gift from Pradipsinh Rathod, University of Washington) from frozen stocks and maintained them as previously described (61). Briefly, we grew parasites at 37°C in vitro at 3% hematocrit (serotype A positive human erythrocytes, Valley Biomedical, VA or BioIVT, NY) in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen, USA) containing 24 mM NaHCO3 and 25 mM HEPES, and supplemented with 20% human type A positive heat inactivated plasma (Valley Biomedical, VA or BioIVT, NY) in sterile, sealed flasks flushed with 5% O2, 5% CO2, and 90% N2 (11). We maintained the cultures with media changes every other day and sub-cultured them as necessary to keep parasitemia below 5%. We determined all parasitemia measurements and staging using SYBR green-based flow cytometry (62). We routinely tested cultures using the LookOut Mycoplasma PCR Detection Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) to confirm negative Mycoplasma status.

Short read sequencing analysis and CNV detection

We analyzed amplifications in Illumina short read datasets of P. falciparum parasites selected by different DSM antimalarial drugs (DSM1, DSM265, DSM267, and DSM705, Table S3) (11,18,37). We first processed and mapped the reads to the reference genome as previously described (24,63). Briefly, we trimmed Illumina adapters from reads with the BBDuk tool in BBMap (version 38.57) (64). We aligned each fastq file to the 3D7 reference genome with Speedseq (version 0.1.0) through BWA-MEM alignment (65). We discarded the reads with low-mapping quality scores (below 10) and removed duplicated reads using Samtools (version 1.10) (66). We analyzed split and discordant reads from the mapped reads using LUMPY in Speedseq to determine the location and length of the previously reported GCH1, DHODH, and multidrug resistance protein 1 (MDR1) amplicons (Table S4) (67). For read-depth analysis, we further filtered the mapped reads using a mapping quality score of 30. To determine the copy number of the GCH1, DHODH, and MDR1 amplicons, we used CNVnator (version 0.4.1) with a bin size of 100 bp; the optimal bin size was chosen to detect GCH1 amplicons in all analyzed samples (68).

Droplet Digital PCR

Prior to Droplet Digital (dd) PCR, we digested DNA with restriction enzyme RsaI (Cut Site: GT/AC) following the manufacturer’s instructions (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) in 37°C incubation for one hour. We selected the restriction enzyme RsaI to cut outside of the ddPCR amplified regions of desired genes and separate amplicon copies to be distributed into droplets. We diluted the digested DNA for ddPCR reactions. We performed ddPCR using ddPCR Supermix for Probes (no dUTP, Bio-Rad Laboratories, California, USA) with DNA input 0.1 ng (in duplicate per sample), 0.025 ng (in duplicate per sample) as previously described (36). The primers and probes used in reactions are included in Table S5. The PCR protocol for probe-based assay was 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 rounds of 95°C for 30 sec and 60°C for 1 min. Seryl-tRNA synthetase and calcium-transporting ATPase (ATP6) served as single copy reference genes on chromosome 7 and chromosome 1 respectively; dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) and GTP cyclohydrolase 1 (GCH1) are multi-copy genes (Table S5). We performed droplet generation and fluorescence readings per the manufacturer’s instructions. For each reaction, we required a minimum number of 10,000 droplets to proceed with analysis. We calculated the ratio of positive droplets containing a single- (ATP6) or multi-copy gene (GCH1, DHODH) versus a single-copy gene (seryl-tRNA synthetase) using the Quantasoft analysis software (QuantaSoft Version 1.7, BioRad Laboratories) and averaged between independent replicates.

DNA extraction for long read sequencing

We lysed asynchronous P. falciparum-infected erythrocytes with 0.15% saponin (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) for 5 min at room temperature and washed them three times with 1× PBS (diluted from 10× PBS Liquid Concentrate, Gibco, USA). We then lysed parasites with 0.1% Sarkosyl Solution (Bioworld, bioPLUS, USA) in the presence of 1 mg/ml proteinase K (from Tritirachium album, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) overnight at 37°C. We first extracted nucleic acids with phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) pH 8.0 (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) three times using 1.5ml light Phase lock Gels (5Prime, USA), then further extracted nucleic acids with chloroform twice using 1.5ml light Phase lock Gels (5Prime, USA). Lastly, we precipitated the DNA with ethanol using the standard Maniatis method (69). To obtain high molecular weight genomic DNA, we avoided any pipetting during the extraction, transferred solutions by direct pouring from one tube to another, and mixed solutions by gently inverting the tubes.

Oxford Nanopore long read sequencing and analysis

For WT1 and H2 samples, we subjected ~1μg of high molecular weight genomic DNA to library preparation for Oxford Nanopore sequencing following the Nanopore Native barcoding genomic DNA protocol (version: NBE_9065_v109_revAB_14Aug2019) with 1x Ligation Sequencing kit (SQK-LSK109, Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, UK). We performed DNA repair and end preparation using NEBNext FFPE DNA Repair Mix (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) and NEBNext End Repair/dA-Tailing Module (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). We cleaned the A-tailed fragments using 0.9X AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, High Wycombe, UK). We then ligated barcodes to the end-prepped DNA using the Native Barcoding Expansion 1–12 kit (EXP-NBD104, Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, UK) and Blunt/TA Ligase Master Mix (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). We cleaned the barcoded samples using 0.9X AMPure XP beads. Then we pooled barcoded samples in equimolar ratios and subjected them to an adaptor ligation step, using the Adapter Mix II from the Native Barcoding Expansion 1–12 kit and NEBNext Quick Ligation Reaction Buffer (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) as well as Quick T4 DNA Ligase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). After adaptor ligation, we cleaned the WT1 and H2 libraries using AMPure XP beads.

For M1 samples, we isolated high molecular weight genomic DNA from 10 flasks of parasites (1–4% parasitemia, ~30–40% late stage parasites) and prepared libraries as above except that we used the cleanup and precipitation reagents provided in the Ultra-long DNA Sequencing kit (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, UK, V14). We quantified the adapter-ligated and barcoded DNA using a Qubit fluorimeter (Qubit 1X dsDNA High Sensitivity Assay Kit, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA).

We sequenced the WT1 and initial H2 libraries using the R9.4.1 flow cell (FLO-MIN106D), another H2 library using the R10 flow cell (FLO-MIN111), and M1 libraries using the R10.4.1 flow cell (FLO-MIN114) on MinION (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, UK). For WT and H2 samples, we ran flow cells for 48 hours (controlled and monitored using the MinKNOW software 3.6.5). For the M1 samples, we ran one-third of the library sequentially on the flow cell for 24 hours each (up to 72 hours in total).

For base calling and demultiplexing of the Nanopore sequencing reads, we used Guppy (version 3.4.5+fb1fbfb) with the parameter settings “-c dna_r9.4.1_450bps_hac.cfg --barcode_kits “EXP-NBD104” -x auto” for samples sequenced with R9.4.1 flow cell and “-c dna_r10_450bps_hac.cfg -x auto” for the sample sequenced with R10 flow cell. We checked the read length and read quality using “Nanoplot” (version 1.0.0) (see Table S1). We trimmed the adapters with “qcat” (version 1.1.0) (70) and filtered the reads with a cutoff “length ≥ 500 and Phred value ≥ 10” using the program “ filtlong version 0.2.0” (https://github.com/rrwick/Filtlong). To estimate the coverage of sequencing reads in each sample, we aligned the filtered reads to 3D7 reference genome (PlasmoDB) using “minimap2” (version 2.17) (71). “QualiMap” (version 2.2.1) (72) was used to calculate the coverage of the aligned reads (see Table S1).

For junction analysis, we aligned Q10-filtered M1 reads (.bam) to the 3D7 reference genome (PlasmdDB) and visualized read sequence at junctions of the GCH1 amplicon using Integrated Genome Viewer (73,74).

Direct visualization of long reads

To visualize structural variants in the parasite genome, we used a custom R Shiny script to plot the arrangement of reference gene segments on individual Nanopore reads (44). Briefly, we defined a target region in the 3D7 reference genome (chromosome 12: 932916bp – 999275bp) that contained 3 genes in the GCH1 amplicon and 11 flanking genes. We extracted the reference sequences of these genes and subsequent intergenic regions, then split these sequences into fragments of 500–1000 base pairs. We compared these fragments to individual Nanopore reads (>10kb) using BLAST (75). We used the BLAST output as input for a custom R script, which drew blocks representing homology between the defined genes (y-axis) and each individual read (x-axis). If genes on the read were arranged in the same order as the reference genome then the blocks would create a diagonal line on the plot. If there was a CNV that altered the gene order or direction then the diagonal line is disrupted. We allowed the percent identity required to draw a homologous rectangle to vary between reads, which varied in quality, using a slider in the Shiny application. To filter out long reads with potentially spurious hits to gene fragments, we also used BLAST to compare Nanopore reads to the reference genome and removed reads with <90% identity to chromosome 12. To compare the mean copy number of GCH1 amplicon and read lengths between WT1, M1, and H2 reads, we performed a one-way ANOVA in Graphpad Prism with an alpha value of 0.05. If significant, differences were further explored using Tukey’s multiple comparisons testing.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1: Spanning reads carry odd copy numbers of GCH1 amplicons

Figure S2: Long-read visualization of GCH1 amplicon from 3D7 parasite line

Figure S3: Parasites lines with DHODH amplicons are selected from parent lines with GCH1 amplicons

Figure S4: GCH1 amplicon junctions show signs of primary and secondary expansion events

Supplemental Methods: Procedures used for the preparation of long read data by Ellen Yeh’s group, Stanford University, as presented in Table S2, including in vitro cultures, mutagenesis, DNA extraction, and sequencing.

Table S1: Oxford Nanopore sequencing datasets new to this manuscript

Table S2: Quantification of long reads covering the GCH1 amplicon displays greater variability in amplicon number from DSM1 resistant parasites

Table S3: DHODH and GCH1 copy number in parasites resistant to DHODH inhibitors

Table S4: Detection of known amplifications by Illumina short reads from parasites resistant to DHODH inhibitors

Table S5: ddPCR primer and probe sequences

Acknowledgments

Our thanks to Michelle Warthan, Noah Brown, and Ali Guler (University of Virginia) for experimental, analysis, and statistical support, Martin Wu and Mercedes Campos-Lopez (University of Virginia) for Oxford Nanopore sequencing support, and the laboratory of Dr. William Petri Jr (University of Virginia) for their helpful discussions and insight. We are grateful to David Fidock (Columbia University) and Dyann F. Wirth (Harvard University) for sharing sequencing data and information on DSM-selected cell lines.

References

- 1.Rich SM, Leendertz FH, Xu G, LeBreton M, Djoko CF, Aminake MN, et al. The origin of malignant malaria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009. Sep 1;106(35):14902–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Casares S, Brumeanu TD, Richie TL. The RTS,S malaria vaccine. Vaccine. 2010. Jul 12;28(31):4880–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blasco B, Leroy D, Fidock DA. Antimalarial drug resistance: linking Plasmodium falciparum parasite biology to the clinic. Nature medicine. 2017. Aug 4;23(8):917–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kidgell C, Volkman SK, Daily J, Borevitz JO, Plouffe D, Zhou Y, et al. A Systematic Map of Genetic Variation in Plasmodium falciparum. PLOS Pathogens. 2006;2(6):e57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conway DJ. Molecular epidemiology of malaria. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007. Jan;20(1):188–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hyde JE. Drug-resistant malaria - an insight. FEBS J. 2007. Sep;274(18):4688–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ribacke U, Mok BW, Wirta V, Normark J, Lundeberg J, Kironde F, et al. Genome wide gene amplifications and deletions in Plasmodium falciparum. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology. 2007. Sep 1;155(1):33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nair S, Miller B, Barends M, Jaidee A, Patel J, Mayxay M, et al. Adaptive Copy Number Evolution in Malaria Parasites. PLOS Genetics. 2008;4(10):e1000243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheeseman IH, Gomez-Escobar N, Carret CK, Ivens A, Stewart LB, Tetteh KKA, et al. Gene copy number variation throughout the Plasmodium falciparum genome. BMC Genomics. 2009. Aug 4;10:353–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bopp SER, Manary MJ, Bright AT, Johnston GL, Dharia NV, Luna FL, et al. Mitotic Evolution of Plasmodium falciparum Shows a Stable Core Genome but Recombination in Antigen Families. PLOS Genetics. 2013. Feb 7;9(2):e1003293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guler JL, Freeman DL, Ahyong V, Patrapuvich R, White J, Gujjar R, et al. Asexual Populations of the Human Malaria Parasite, Plasmodium falciparum, Use a Two-Step Genomic Strategy to Acquire Accurate, Beneficial DNA Amplifications. PLOS Pathogens. 2013. May 23;9(5):e1003375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Menard D, Dondorp A. Antimalarial Drug Resistance: A Threat to Malaria Elimination. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2017;7(7):a025619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foote SJ, Thompson JK, Cowman AF, Kemp DJ. Amplification of the multidrug resistance gene in some chloroquine-resistant isolates of P. falciparum. Cell. 1989. Jun 16;57(6):921–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson CM, Volkman SK, Thaithong S, Martin RK, Kyle DE, Milhous WK, et al. Amplification of pfmdr1 associated with mefloquine and halofantrine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum from Thailand. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology. 1993. Jan 1;57(1):151–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heinberg A, Siu E, Stern C, Lawrence EA, Ferdig MT, Deitsch KW, et al. Direct evidence for the adaptive role of copy number variation on antifolate susceptibility in Plasmodium falciparum. Molecular microbiology. 2013. May;88(4):702–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Osei M, Ansah F, Matrevi SA, Asante KP, Awandare GA, Quashie NB, et al. Amplification of GTP-cyclohydrolase 1 gene in Plasmodium falciparum isolates with the quadruple mutant of dihydrofolate reductase and dihydropteroate synthase genes in Ghana. PLOS ONE. 2018;13(9):e0204871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phillips MA, Rathod PK. Plasmodium dihydroorotate dehydrogenase: a promising target for novel anti-malarial chemotherapy. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2010;10(3):226–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mandt REK, Lafuente-Monasterio MJ, Sakata-Kato T, Luth MR, Segura D, Pablos-Tanarro A, et al. In vitro selection predicts malaria parasite resistance to dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibitors in a mouse infection model. Science Translational Medicine. 2019;11(521):eaav1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kümpornsin K, Modchang C, Heinberg A, Ekland EH, Jirawatcharadech P, Chobson P, et al. Origin of Robustness in Generating Drug-Resistant Malaria Parasites. Mol Biol Evol. 2014. Jul;31(7):1649–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heinberg A, Kirkman L. The molecular basis of antifolate resistance in Plasmodium falciparum: looking beyond point mutations. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2015/02/18 ed. 2015;1342(1):10–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herman JD, Rice DP, Ribacke U, Silterra J, Deik AA, Moss EL, et al. A genomic and evolutionary approach reveals non-genetic drug resistance in malaria. Genome Biol. 2014;15(11):511–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manary MJ, Singhakul SS, Flannery EL, Bopp SER, Corey VC, Bright AT, et al. Identification of pathogen genomic variants through an integrated pipeline. BMC Bioinformatics. 2014. Mar 3;15(1):63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cowell AN, Istvan ES, Lukens AK, Gomez-Lorenzo MG, Vanaerschot M, Sakata-Kato T, et al. Mapping the malaria parasite druggable genome by using in vitro evolution and chemogenomics. Science. 2018;359(6372):191–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huckaby AC, Granum CS, Carey MA, Szlachta K, Al-Barghouthi B, Wang YH, et al. Complex DNA structures trigger copy number variation across the Plasmodium falciparum genome. Nucleic Acids Research. 2018. Dec 21;47(4):1615–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alkan C, Coe BP, Eichler EE. Genome structural variation discovery and genotyping. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2011. May 1;12(5):363–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Treangen TJ, Salzberg SL. Repetitive DNA and next-generation sequencing: computational challenges and solutions. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2012. Jan 1;13(1):36–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kosugi S, Momozawa Y, Liu X, Terao C, Kubo M, Kamatani Y. Comprehensive evaluation of structural variation detection algorithms for whole genome sequencing. Genome Biology. 2019. Jun 3;20(1):117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beghain J, Langlois AC, Legrand E, Grange L, Khim N, Witkowski B, et al. Plasmodium copy number variation scan: gene copy numbers evaluation in haploid genomes. Malaria Journal. 2016. Apr 12;15(1):206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miles A, Iqbal Z, Vauterin P, Pearson R, Campino S, Theron M, et al. Indels, structural variation, and recombination drive genomic diversity in Plasmodium falciparum. Genome Res. 2016/08/16 ed. 2016;26(9):1288–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cretu Stancu M, van Roosmalen MJ, Renkens I, Nieboer MM, Middelkamp S, de Ligt J, et al. Mapping and phasing of structural variation in patient genomes using nanopore sequencing. Nature Communications. 2017. Nov 6;8(1):1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sedlazeck FJ, Rescheneder P, Smolka M, Fang H, Nattestad M, von Haeseler A, et al. Accurate detection of complex structural variations using single-molecule sequencing. Nat Methods. 2018/04/30 ed. 2018;15(6):461–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sedlazeck FJ, Lee H, Darby CA, Schatz MC. Piercing the dark matter: bioinformatics of long-range sequencing and mapping. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2018. Jun 1;19(6):329–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ho SS, Urban AE, Mills RE. Structural variation in the sequencing era. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2020. Mar 1;21(3):171–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Belikova D, Jochim A, Power J, Holden MTG, Heilbronner S. “Gene accordions” cause genotypic and phenotypic heterogeneity in clonal populations of Staphylococcus aureus. Nature Communications. 2020. Jul 14;11(1):3526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rugbjerg P, Dyerberg ASB, Quainoo S, Munck C, Sommer MOA. Short and long-read ultra-deep sequencing profiles emerging heterogeneity across five platform Escherichia coli strains. Metabolic Engineering. 2021. May 1;65:197–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McDaniels JM, Huckaby AC, Carter SA, Lingeman S, Francis A, Congdon M, et al. Extrachromosomal DNA amplicons in antimalarial-resistant Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Microbiol. 2020/11/19 ed. 2021;115(4):574–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palmer MJ, Deng X, Watts S, Krilov G, Gerasyuto A, Kokkonda S, et al. Potent Antimalarials with Development Potential Identified by Structure-Guided Computational Optimization of a Pyrrole-Based Dihydroorotate Dehydrogenase Inhibitor Series. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2021. May 13;64(9):6085–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Phillips MA, Lotharius J, Marsh K, White J, Dayan A, White KL, et al. A long-duration dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibitor (DSM265) for prevention and treatment of malaria. Sci Transl Med. 2015. Jul 15;7(296):296ra111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Turkiewicz A, Manko E, Sutherland CJ, Benavente ED, Campino S, Clark TG. Genetic diversity of the Plasmodium falciparum GTP-cyclohydrolase 1, dihydrofolate reductase and dihydropteroate synthetase genes reveals new insights into sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine antimalarial drug resistance. PLOS Genetics. 2020. Dec 31;16(12):e1009268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sepúlveda N, Campino SG, Assefa SA, Sutherland CJ, Pain5 A, Clark TG. A Poisson hierarchical modelling approach to detecting copy number variation in sequence coverage data. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.White J, Dhingra SK, Deng X, El Mazouni F, Lee MCS, Afanador GA, et al. Identification and Mechanistic Understanding of Dihydroorotate Dehydrogenase Point Mutations in Plasmodium falciparum that Confer in Vitro Resistance to the Clinical Candidate DSM265. ACS Infect Dis. 2019. Jan 11;5(1):90–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ross LS, Gamo FJ, Lafuente-Monasterio MJ, Singh OMP, Rowland P, Wiegand RC, et al. In vitro resistance selections for Plasmodium falciparum dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibitors give mutants with multiple point mutations in the drug-binding site and altered growth. J Biol Chem. 2014. Jun 27;289(26):17980–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lukens AK, Ross LS, Heidebrecht R, Javier Gamo F, Lafuente-Monasterio MJ, Booker ML, et al. Harnessing evolutionary fitness in Plasmodium falciparum for drug discovery and suppressing resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014. Jan 14;111(2):799–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ebel ER, Kim BY, McDew-White M, Egan ES, Anderson TJC, Petrov DA. Antigenic diversity in malaria parasites is maintained on extrachromosomal DNA. bioRxiv. 2023. Jan 1;2023.02.02.526885. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Girgis HS, DuPai CD, Lund J, Reeder J, Guillory J, Durinck S, et al. Single-molecule nanopore sequencing reveals extreme target copy number heterogeneity in arylomycin-resistant mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021. Jan 5;118(1):e2021958118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grigorev K, Foox J, Bezdan D, Butler D, Luxton JJ, Reed J, et al. Haplotype diversity and sequence heterogeneity of human telomeres. Genome Res. 2021. Jul;31(7):1269–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dixon K, Shen Y, O’Neill K, Mungall KL, Chan S, Bilobram S, et al. Defining the heterogeneity of unbalanced structural variation underlying breast cancer susceptibility by nanopore genome sequencing. Eur J Hum Genet. 2023. May;31(5):602–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pholwat S, Liu J, Stroup S, Jacob ST, Banura P, Moore CC, et al. The Malaria TaqMan Array Card Includes 87 Assays for Plasmodium falciparum Drug Resistance, Identification of Species, and Genotyping in a Single Reaction. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy [Internet]. 2017. May 1 [cited 2020 Jul 29];61(5). Available from: https://aac.asm.org/content/61/5/e00110-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Walliker D, Quakyi IA, Wellems TE, McCutchan TF, Szarfman A, London WT, et al. Genetic analysis of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Science. 1987. Jun 26;236(4809):1661–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wellems TE, Panton LJ, Gluzman IY, do Rosario VE, Gwadz RW, Walker-Jonah A, et al. Chloroquine resistance not linked to mdr-like genes in a Plasmodium falciparum cross. Nature. 1990. May 17;345(6272):253–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chulay JD, Watkins WM, Sixsmith DG. Synergistic Antimalarial Activity of Pyrimethamine and Sulfadoxine against Plasmodium falciparum In Vitro. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1984. May 1;33(3):325–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Watkins WM, Sixsmith DG, Chulay JD, Spencer HC. Antagonism of sulfadoxine and pyrimethamine antimalarial activity in vitro by p-aminobenzoic acid, p-aminobenzoylglutamic acid and folic acid. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology. 1985. Jan 1;14(1):55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang P, Brobey RKB, Horii T, Sims P, Hyde JE, Schapira A, et al. Utilization of exogenous folate in the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum and its critical role in antifolate drug synergy The Susceptibility of Plasmodium Falciparum to Sulfadoxine and Pyrimethamine: Correlation of in Vivo and in Vitro Results Synergistic Antimalarial Activity of Pyrimethamine and Sulfadoxine against Plasmodium falciparum In Vitro. Molecular Microbiology. 1986. Mar 1;32(2):239–45. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Salcedo-Sora JE, Ochong E, Beveridge S, Johnson D, Nzila A, Biagini GA, et al. The Molecular Basis of Folate Salvage in Plasmodium falciparum: CHARACTERIZATION OF TWO FOLATE TRANSPORTERS*. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011. Dec 30;286(52):44659–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Valenciano AL, Fernández-Murga ML, Merino EF, Holderman NR, Butschek GJ, Shaffer KJ, et al. Metabolic dependency of chorismate in Plasmodium falciparum suggests an alternative source for the ubiquinone biosynthesis precursor. Scientific Reports. 2019. Sep 26;9(1):13936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kumar S, Li X, McDew-White M, Reyes A, Delgado E, Sayeed A, et al. A Malaria Parasite Cross Reveals Genetic Determinants of Plasmodium falciparum Growth in Different Culture Media. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022. May 30;12:878496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Llanos-Cuentas A, Casapia M, Chuquiyauri R, Hinojosa JC, Kerr N, Rosario M, et al. Antimalarial activity of single-dose DSM265, a novel plasmodium dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibitor, in patients with uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum or Plasmodium vivax malaria infection: a proof-of-concept, open-label, phase 2a study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018. Aug;18(8):874–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ravenhall M, Benavente ED, Mipando M, Jensen ATR, Sutherland CJ, Roper C, et al. Characterizing the impact of sustained sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine use upon the Plasmodium falciparum population in Malawi. Malar J. 2016. Nov 29;15:575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moon RW, Sharaf H, Hastings CH, Ho YS, Nair MB, Rchiad Z, et al. Normocyte-binding protein required for human erythrocyte invasion by the zoonotic malaria parasite Plasmodium knowlesi. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016. Jun 28;113(26):7231–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Phillips MA, Gujjar R, Malmquist NA, White J, El Mazouni F, Baldwin J, et al. Triazolopyrimidine-based dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibitors with potent and selective activity against the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. J Med Chem. 2008/06/04 ed. 2008;51(12):3649–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Haynes JD, Diggs CL, Hines FA, Desjardins RE. Culture of human malaria parasites Plasmodium falciparum. Nature. 1976. Oct 1;263(5580):767–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bei AK, Desimone TM, Badiane AS, Ahouidi AD, Dieye T, Ndiaye D, et al. A flow cytometry-based assay for measuring invasion of red blood cells by Plasmodium falciparum. Am J Hematol. 2010. Apr;85(4):234–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu S, Huckaby AC, Brown AC, Moore CC, Burbulis I, McConnell MJ, et al. Single-cell sequencing of the small and AT-skewed genome of malaria parasites. Genome Medicine. 2021. May 4;13(1):75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bushnell B. BBMap [Internet]. [cited 2021 Dec 1]. Available from: http://sourceforge.net/projects/bbmap/ (2019)

- 65.Chiang C, Layer RM, Faust GG, Lindberg MR, Rose DB, Garrison EP, et al. SpeedSeq: ultra-fast personal genome analysis and interpretation. Nat Methods. 2015. Oct;12(10):966–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(16):2078–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Layer RM, Chiang C, Quinlan AR, Hall IM. LUMPY: a probabilistic framework for structural variant discovery. Genome Biology. 2014. Jun 26;15(6):R84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Abyzov A, Urban AE, Snyder M, Gerstein M. CNVnator: an approach to discover, genotype, and characterize typical and atypical CNVs from family and population genome sequencing. Genome Res. 2011/02/07 ed. 2011;21(6):974–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Maniatis T, Sambrook J, Fritsch EF. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. xxxviii + 1546 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Oxford Nanopore Technologies. qcat (version 1.1.0) [Internet]. [cited 2021 Jun 1]. Available from: https://github.com/nanoporetech/qcat

- 71.Li H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2018;34(18):3094–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.García-Alcalde F, Okonechnikov K, Carbonell J, Cruz LM, Götz S, Tarazona S, et al. Qualimap: evaluating next-generation sequencing alignment data. Bioinformatics. 2012. Aug 22;28(20):2678–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdóttir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol. 2011. Jan;29(1):24–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thorvaldsdóttir H, Robinson JT, Mesirov JP. Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV): highperformance genomics data visualization and exploration. Briefings in Bioinformatics. 2013. Mar 1;14(2):178–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ye J, McGinnis S, Madden TL. BLAST: improvements for better sequence analysis. Nucleic Acids Research. 2006;34(suppl_2):W6–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: Spanning reads carry odd copy numbers of GCH1 amplicons

Figure S2: Long-read visualization of GCH1 amplicon from 3D7 parasite line

Figure S3: Parasites lines with DHODH amplicons are selected from parent lines with GCH1 amplicons

Figure S4: GCH1 amplicon junctions show signs of primary and secondary expansion events

Supplemental Methods: Procedures used for the preparation of long read data by Ellen Yeh’s group, Stanford University, as presented in Table S2, including in vitro cultures, mutagenesis, DNA extraction, and sequencing.

Table S1: Oxford Nanopore sequencing datasets new to this manuscript

Table S2: Quantification of long reads covering the GCH1 amplicon displays greater variability in amplicon number from DSM1 resistant parasites

Table S3: DHODH and GCH1 copy number in parasites resistant to DHODH inhibitors

Table S4: Detection of known amplifications by Illumina short reads from parasites resistant to DHODH inhibitors

Table S5: ddPCR primer and probe sequences