Abstract

Tiled amplicon sequencing has served as an essential tool for tracking the spread and evolution of SARS-CoV-2 in real-time directly from environmental and clinical samples. Over 14 million SARS-CoV-2 genomes are now available on GISAID, most sequenced and assembled via tiled amplicon sequencing. While computational tools for tiled amplicon design exist, they require downstream manual optimization both computationally and experimentally, which is slow, laborious, and costly. Here, we present Olivar, the first open-source computational tool capable of fully automating the design of tiled amplicons by integrating SNPs, non-specific amplification, etc. into a “risk score” for each single nucleotide of the target genome. Olivar evaluates thousands sets of possible tiled amplicons and minimizes primer dimer in parallel. In a direct in-silico comparison with PrimalScheme, we show that Olivar has fewer SNPs overlapping with primers and predicted PCR byproducts. We also compared Olivar head-to-head with ARTIC v4.1, the most widely used tiled amplicons for SARS-CoV-2 sequencing. We next tested Olivar on real wastewater samples and found that our automated approach had up to 3-fold higher mapping rates compared to ARTIC v4.1 while retaining similar coverage. To the best of our knowledge, Olivar represents the first open-source, fully automated design tool that simultaneously evaluates and optimizes risks of known primer design issues for robust tiled amplicon sequencing. Olivar is available as a web application at https://olivar.rice.edu/. Olivar can also be installed locally as a command line tool with Bioconda. Source code, installation guide and usage are available at https://gitlab.com/treangenlab/olivar.

INTRODUCTION

The devastating COVID-19 pandemic has forever highlighted the utility and importance of biosurveillance for tracking the spread of emerging pathogens. Metagenomic sequencing of environmental samples has enabled the discovery of novel pathogens 1, provided real-time insights into the spread and evolution of infectious disease 2, and enabled the exploration of variant-specific effects on the host 3. However, the relatively high cost and long turnaround time of metagenomic sequencing remain impractical when a large number of samples and fast turnaround times are necessary, which is the baseline for monitoring pathogens from the environment. Targeted approaches offer advantages in this setting as the ratio of the targeted pathogen is typically low compared to non-target background sequences 4,5 (e.g., sequencing of wastewater samples by 6), making untargeted metagenomic sequencing both more expensive, computationally intensive, and often lacking in sensitivity.

Thus, targeted amplification or enrichment can both decrease sequencing cost and improve the sequencing sensitivity for pathogen genomes of interest 4,5. PCR tiling and DNA hybridization probes are two common approaches to amplify whole genomes of specific viruses 5,7. While DNA hybridization probes are better at preserving the relative abundance of different species, PCR tiling has the advantage of simpler experimental workflow, faster turnaround time, and less DNA input requirement 7. Therefore, PCR tiling has been widely used to monitor SARS-CoV-2 and characterize SARS-CoV-2 variant 8. As of December 27th, 2022, there are 14.4 million SARS-CoV-2 genomes on GISAID9, and 6.5 million available in NCBI GenBank 10, the vast majority of which were sequenced and assembled via tiled amplicon sequencing. However, when combining hundreds of primers within a single tube, PCR tiling has similar pitfalls as multiplexed PCR, including (i) uneven amplification of different genomic regions and (ii) excessive PCR byproducts (e.g., primer dimers and amplification of non-targeted sequences), resulting in a higher cost to reach a minimum acceptable sequencing depth 11. PCR byproducts can also result in false variant calls 12, requiring manual oversight, re-analysis and slow down the deployment which is critical in the midst of the pandemic. Moreover, PCR primers should be designed to avoid genomic regions with heavy variation 13 (e.g., single-nucleotide polymorphisms or SNPs) and secondary structures 11 to prevent amplicon dropout. Altogether, these pitfalls can lead to higher sequencing cost, uneven coverage, and lower sensitivity, which to date requires one or more runs of experimental validation and manual primer redesign, making the development of a PCR tiling assay costly and labor intensive 14.

Although there are existing tools for designing PCR tiling, some design tiled amplicons as single plex assays 15 or a number of small primer pools (<10 primers) 16, instead of multiplexed assays where tens or hundreds of primers are mixed in the same reaction. Furthermore, previous approaches do not optimize all of the aforementioned criteria simultaneously, nor do they adequately explore the solution space of possible primer combinations 4. The current state-of-art PCR tiling design software tool, PrimalScheme 4, takes a sequential approach to primer design. Specifically, starting from the left side (5’ end) of the genome, PrimalScheme sequentially designs each primer until the whole genome is covered, thus, newly designed primers will not affect the choice of previously designed primers. Although PrimalScheme also considers genomic variations, GC content, primer dimers, etc., the choice of new primers will be limited by previously designed primers. For example, the region where a new primer is generated might have high GC content, or candidates of the new primer might form primer dimers with previously designed primers. In the worst-case scenario for PrimalScheme, a gap in tiling will exist since no primer candidate satisfies the design requirements, leading to reduced genomic coverage and/or requiring manual redesign. Thus, their output primers are semi-optimized and often require further tweaking and redesign 14. This is evidenced by the most widely used PCR tiling primer set in ARTIC 17, initially designed with PrimalScheme and used to sequence millions of SARS-CoV-2 genomes at this point. ARTIC has undergone several iterations of manual tweaking and optimization 13,14,17, including the primer dimer issue of the latest ARTIC v4.1 12, and will continue to require manual tweaking and refinement as new variants arise.

Here we present Olivar, an end-to-end pipeline for rapid and automatic design of primers for PCR tiling. Olivar accomplishes this by introducing the concept of the risk of primer design at the single nucleotide level, enabling fast evaluation of thousands of potential tiled amplicon sets. Olivar looks for designs that avoid regions with high-risk scores based on SNPs, non-specificity, GC contents, and sequence complexity. We selected these four components according to known challenges with multiplexed primer design: SNPs represent sequence variation, non-specificity represents the likelihood of non-specific priming, while sequences with extreme GC content and/or low complexity are more likely to be repetitive, bearing secondary structures 18 and producing more primer dimers 11. Olivar also implements the SADDLE algorithm 11 to optimize primer dimers in parallel and provides a separate validation module that allows users to evaluate their multiplex PCR primers from various aspects, including the likelihood of dimerization, amplification of non-targeted sequences, etc.

To evaluate the performance of our method, we used Olivar to automatically design a set of primers that tile the entire SARS-CoV-2 genome in 146 amplicons in under 30 minutes. In a direct in-silico comparison with PrimalScheme, Olivar had lower predicted primer dimerization, fewer SNPs overlapping with primers (4 vs. 18), and fewer predicted non-specific amplifications (5 vs. 27). We conducted an experimental head-to-head comparison with the latest ARTIC v4.1, the most widely used tiled amplicons for SARS-CoV-2, and found that Olivar had similar mapping rates (~90%) and better coverage for synthetic RNA samples with both low (18) and high (35) cycle threshold (Ct) values.

We also tested Olivar and ARTIC v4.1 on 4 wastewater samples, and showed that Olivar has 1 to 3-fold higher mapping rates and similar coverage. Furthermore, Olivar includes an interactive visualization module that shows the targeted sequence’s risk landscape and the primer placement, allowing a convenient overview of the automated design (Figure 1).

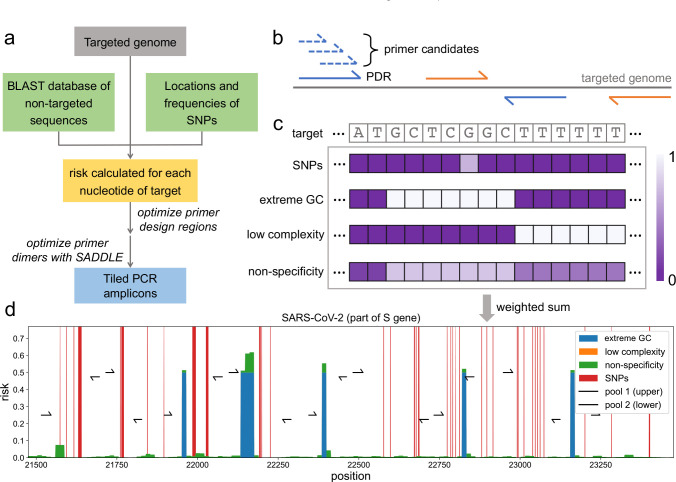

Figure 1: Overall workflow of Olivar and example output.

(a) The input of Olivar consists of three components: the targeted sequence, a BLAST database built with non-targeted sequences and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) to be avoided by primers. Based on the provided inputs, a risk score is calculated for each nucleotide of the targeted sequence. Primer design regions are optimized according to the array of risk scores. One or more primer candidates are generated for each primer design region, and the primer set with minimum primer dimerization is selected with the previously published algorithm SADDLE. (b) A primer design region (PDR) is a short region (40nt by default) on the targeted genome. A pair of PDRs (blue or orange solid lines) covers the genomic region between them, and a valid set of PDRs should cover the whole targeted genome. Primer candidates (blue dashed lines) are generated from each PDR by SADDLE. (c) A risk array consists of four components: SNPs, extreme GC, low complexity and non-specificity, and all of them are calculated for each nucleotide of target and range between 0 and 1. The final risk is calculated as the weighted sum of the four risk components. (d) An example of the risk landscape of the SARS-CoV-2 genome, as well as primers designed by Olivar. The beginning of the S gene is shown, and each risk component is shown in a different color. Different risk components shown in the figure are stacked together instead of overlapping.

RESULTS

There are three major steps in Olivar, as illustrated in Figure 1a,

Generation of a risk score for each nucleotide of the targeted sequence based on user-provided inputs (reference sequence, location of SNPs, BLAST database, etc.).

Generation and evaluation of primer design region (PDR) sets based on a Loss function.

Generation of primer candidates for each PDR and optimization of primer dimer with the SADDLE algorithm.

The primer design region (PDR) is a short DNA sequence (40nt by default) from which primer candidates are generated with SADDLE (Figure 1b). The risk score emphasizes sequence features that should be avoided for primer design (e.g., high GC regions), and its definition can be tailored for specific applications. Here, we select four components critical to primer design to calculate the risk score: single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), high/low GC content (extreme GC), homopolymers (low complexity), and repeated sequence across genomes (non-specificity). Each nucleotide is given a score for each of the four sequence features, creating four different arrays named as risk components. Risk components are then weighted with user-defined weights and summed together to generate the risk array (Figure 1c). The risk array can be visualized as a risk landscape and overlaid with the primers designed, giving users a better understanding of how primers are placed on the targeted sequence (Figure 1d). The visualization module is included in the Olivar software as well as the Olivar web app. Given an array of risk scores, Olivar can efficiently evaluate thousands of potential PDR sets and choose the best one based on a Loss function. The best PDR set is input to SADDLE and the combination of primer candidates with minimum dimerization likelihood is output as the final primer set. Detailed description of risk components, generation of PDR sets and the Loss function can be found in Methods.

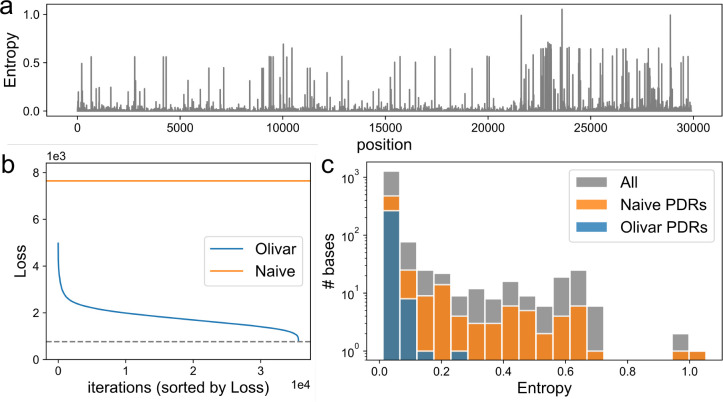

Olivar designs PDRs that effectively avoid highly variable genomic regions

To demonstrate Olivar’s ability to avoid high-risk regions in a target genome, we used the publicly available SARS-CoV-2 data on Nextstrain 19 where Shannon’s entropy of each base in the reference genome is provided (Figure 2a). Calculation of Nextstrain entropy can be found in Methods. We input locations with entropy greater than 0.01 to Olivar as an analogy of SNP location and frequency and optimized PDRs with default parameters described in Methods. Compared to a naively generated set of PDRs, the Olivar optimized PDR set has about 10-fold lower Loss (765.4 vs. 7644.0, Figure 2b), after 35,584 iterations on a personal computer (2.4GHz 8-Core CPU) in 20 minutes wall clock, with peak memory usage less than 500MB. Figure 2c shows the histogram of entropy of all bases in the reference genome, as well as bases within naive PDRs or Olivar PDRs, and every base with entropy greater than 0.3 is avoided by Olivar.

Figure 2: Optimization of PDRs with nucleotide entropy provided by the Nextstrain SARS-CoV-2 database.

(a) Shannon entropy at each base position, provided by Nextstrain. Details about entropy calculation can be found in Methods. Entropy larger than 0.01 (1,517 bases) is input to Olivar as SNP frequency. (b) 35,584 PDR sets are generated by Olivar and the optimal PDR set with minimal Loss of 765.4 is chosen (dashed line). A randomly generated naive set of PDRs has a Loss of 7644.0. (c) Histogram of entropy of bases. Of the 1,517 bases with entropy greater than 0.01 (gray), 275 overlap with Olivar PDRs (blue), while 560 overlap with naive PDRs (orange).

Olivar outperforms PrimalScheme in silico

We used Olivar and the state-of-the-art PCR tiling design software PrimalScheme to design tiled amplicons for SARS-CoV-2, based on public genomes on GISAID before March 1st, 2022. We first generated SNPs of Delta (B.1.617.2) and Omicron (B.1.1.529) variants with the software tool Variant Database 20. 440 SNPs with frequencies greater than 1% were used as input to Olivar and PrimalScheme. Since PrimalScheme takes a group of sequences (no more than 100 sequences) as input instead of locations and frequencies of SNPs, we created 100 pseudo genomes bearing those 440 SNPs as input to PrimalScheme. Human genome assembly GRCh38.p13 was used as the non-targeted BLAST database for Olivar. Desired amplicon length was set to 252nt to 420nt for Olivar and PrimalScheme, with other input parameters kept as default. Since there is randomness in the Olivar pipeline, specifically in optimizing PDRs, we conducted 6 runs to test its reproducibility. On the other hand, there is no randomness in the PrimalScheme pipeline and PrimalScheme will generate the same primer set with the same input. We first compared 1 of the 6 Olivar designs with the Primalscheme design (Figure 3a–d). Compared with PrimalScheme, Olivar primers had a lower predicted dimerization likelihood, represented by the dimer_score of SADDLE 11(Figure 3a,b), as well as lower BLAST hits against human genome (Figure 3c). The risk score of each primer was also calculated, with Olivar having a lower average risk per primer (0.14 vs. 0.28, Figure 3d). Across 6 Olivar runs, Olivar primers had fewer SNPs overlapping with primers on average (3.67 vs. 18), as well as lower average frequency of those SNPs (3.03% vs. 10.56%) (Figure 3e). We also predicted the number of non-specific amplicons with BLAST, and Olivar had fewer non-specific amplicons on average compared to PrimalScheme (5 vs. 27, Figure 3f). In addition, the PrimalScheme design has 10 gaps (regions not covered by amplicon inserts, except for the left and right ends of the genome), with total length of 427nt, while there were no gaps in any of the 6 Olivar designs. Default parameters of Olivar and PrimalScheme, SNP calling with Variant Database, generation of pseudo genomes for PrimalScheme and prediction of non-specific amplicons can be found in Methods.

Figure 3: In silico comparison between Olivar and PrimalScheme on SARS-CoV-2 genome.

(a) For each primer pool, primer dimerization is optimized with the previously published algorithm SADDLE. SADDLE calculates a dimer score for each primer within a primer pool, as an estimation of primer-primer interaction. (b) The log10(dimer_score + 1) is calculated for each primer of Olivar or PrimalScheme (pool 1 and 2 are shown together). (c) The number of hits for each primer is acquired with the BLAST database of non-targeted sequences. Here only human genome is included. log10(BLAST_hits + 1) is calculated for each primer of Olivar or PrimalScheme (pool 1 and 2 are shown together). (d) The risk of a primer is the sum of all risk scores within the primer. Risk distribution is shown for all primers of Olivar or PrimalScheme. Olivar primers have average risk of 0.14, and PrimalScheme primers have average risk of 0.29. (e,f) Results of six Olivar runs with the same settings but different random seed. (e) Frequencies of the SNPs that overlap with primers. Out of 440 input SNPs, Olivar primers overlap with 3.67 SNPs on average, with average frequency of 3.03% and highest frequency of 10.72%, while PrimalScheme primers overlap with 18 SNPs with average frequency of 10.56% and highest frequency of 98.31%. (f) Six Olivar designs have 5 predicted non-specific amplicons on average, and the PrimalScheme design has 27 predicted non-specific amplicons. Details about the prediction of non-specific amplicons can be found in Methods.

Experimental validation of Olivar on synthetic RNA

To further demonstrate Olivar’s performance in real-world applications, we ordered one of the Olivar-designed primer set described above (Figure 3a–d) and compared Illumina sequencing results with the widely used SARS-CoV-2 primer set ARTIC v4.1. Note that ARTIC v4.1 has additional primers added to target the Omicron variants and certain primers have double concentration in the primer pool for better coverage uniformity. We first tested both primer sets on synthetic SARS-CoV-2 RNA samples (Twist Bioscience), with different RNA concentrations, as determined by the Ct value from quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) targeting the N gene. For both low Ct and high Ct samples, Olivar and ARTIC v4.1 had a similar percentage of sequencing reads mapped to the reference, ranging from 75% to 95%, while Olivar had a lower amount of bases with less than 0.05× median coverage (Table 1). Detailed description of experimental protocols and analysis of sequencing results can be found in Methods.

Table 1:

Mapping rate and coverage uniformity of Olivar Sars-Cov-2 primers and ARTIC v4.1 primers.

| sample concentration1 | mapping rate2 | less than 0.05× median coverage3 | 0.1× to 10× median coverage | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Olivar | ARTIC | Olivar | ARTIC | Olivar | ARTIC | |||

| synthetic RNA control | Ct=18 (~ 5 × 105 copy/ul) | replicate 1 | 86.7% | 88.1% | 3.2% | 5.9% | 92.5% | 93.1% |

| replicate 2 | 90.2% | 85.9% | 3.7% | 6.0% | 92.7% | 91.5% | ||

| Ct=35 (~ 3 copy/ul) | replicate 1 | 92.6% | 89.4% | 10.1% | 18.5% | 73.4% | 71.5% | |

| replicate 2 | 88.8% | 84.5% | 10.7% | 20.6% | 69.8% | 73.3% | ||

| wastewater site: CB | 106.9 copy/ul | Aug. 08, 2022 | 15.0% | 4.6% | 10.4% | 14.1% | 65.6% | 70.5% |

| 83.9 copy/ul | Aug. 15, 2022 | 52.7% | 42.9% | 8.8% | 15.6% | 77.8% | 71.9% | |

| wastewater site: KB | 28.1 copy/ul | Aug. 08, 2022 | 22.0% | 10.6% | 19.1% | 17.3% | 64.1% | 59.3% |

| 35.4 copy/ul | Aug. 15, 2022 | 27.6% | 20.0% | 12.4% | 11.6% | 72.4% | 64.2% | |

Concentration of wastewater samples are measured with ddPCR.

Percentage of concordant read pairs mapped to the reference. Average of pool 1 and pool 2.

Percentage of bases with the corresponding coverage.

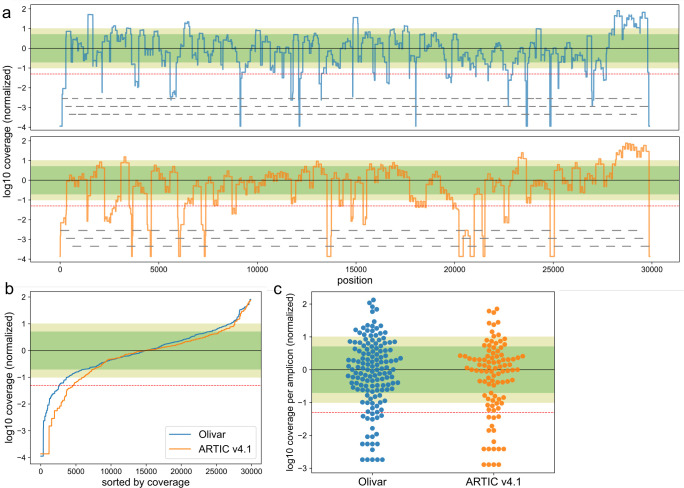

Sequencing SARS-CoV-2 from wastewater with Olivar primers and ARTIC v4.1

Targeted amplification of pathogen genomes from wastewater samples is challenging since the targeted genomes are highly fragmented, dilute, and comprised of mixtures of circulating variants 6. We collected 4 wastewater samples from two locations in Houston, USA at two time points. Using the same primer sets and experimental protocol as above, we observed 1 to 3-fold higher mapping rates of Olivar than ARTIC v4.1, shown in Table 1. Olivar also had lower or similar percentage of low coverage bases, compared with ARTIC v4.1 (Table 1). Figure 4a shows the overall genomic coverage of both Olivar and ARTIC v4.1 for one of the wastewater samples (site: CB, Aug. 15, 2022), with amplicon locations shown in gray lines. To compare the coverage uniformity of Olivar and ARTIC v4.1, genomic locations in Figure 4a are sorted by coverage (Figure 4b), showing Olivar has fewer bases with low coverage (8.8% vs. 15.6%). This is likely due to Olivar designs having shorter amplicon lengths and more overlapping of amplicons since there is a smaller difference for low coverage amplicons (13.7% and 16.2% for Olivar and ARTIC v4.1, respectively), shown in Figure 4c. Details about coverage calculation can be found in Methods.

Figure 4: Sars-Cov-2 whole genome coverage of both Olivar (blue) and ARTIC v4.1 (orange) primers. Figures showing results from one wastewater sample (site: CB, Aug. 15, 2022).

(a) log10 coverage of each base. Coverage is normalized by median coverage of all bases. Gray lines represent location of amplicons. (b) Sorted log10 coverage of each base. Black solid line represents the median coverage, green shade represents 0.2× to 5× median coverage (Olivar: 58.8% bases, ARTIC v4.1: 59.4% bases), olive shade represents 0.1× to 10× coverage (Olivar: 77.8% bases, ARTIC v4.1: 71.9% bases), red dashed line represents 0.05× median coverage (Olivar: 8.8% bases less than 0.05×, ARTIC v4.1: 15.6% bases less than 0.05×). Coverage uniformity of other samples is shown in Table 1. (c) log10 coverage of each amplicon, normalized by median amplicon coverage. (Olivar: 52.7% between 0.2× to 5× coverage, 67.8% between 0.1× to 10× coverage, 13.7% less than 0.05× coverage; ARTIC: 52.5% between 0.2× to 5× coverage, 67.7% between 0.1× to 10× coverage, 16.2% less than 0.05× coverage).

METHODS

Generation of risk array

A risk array is an array of non-negative real numbers

where is the length of the targeted sequence. The array consists of four weighted components,

where , , and are set to 1 as default. represent SNPs, represent extreme GC content, represent low sequence complexity and represent non-specificity. For each user provided single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) at position p of the targeted sequence,

where freq is the frequency or weight of the SNP to be avoided (usually between 0 and 1). To calculate the other three components, a set of equal-length, overlapping, and evenly distributed words are generated from the targeted sequence. Suppose the length of each word is ws (28 by default), is divisible by ws and ws is divisible by a positive integer (14 by default), then

where is the set of words, is the targeted sequence and i is a positive integer. If is not divisible by ws, the targeted sequence is minimally trimmed to satisfy this condition, and corresponding elements in are set to 0. GC content and sequence complexity of each word is calculated. Sequence complexity is calculated based on Shannon entropy (described below). The number of BLAST hits of each word is acquired with the user-provided BLAST database. The following parameters are set to the NCBI BLAST+ program 21 (version 2.12.0): e-value as 5, reward as 1, penalty as −3, gapopen as 5, gapextend as 2. These are the default parameters of the task blastn-short. For a nucleotide at position of the targeted sequence, there is a set of words overlapping with that nucleotide, denoted as . The average GC content of , the average sequence complexity of and the average number of BLAST hits of are denoted as gc, cmplx and hits, respectively. is an array of 0s with length of . Then,

where gcmin (0.25 by default), gcmax (0.75 by default) and cmplxlow (0.4 by default) are user defined. is then normalized to get

Calculation of sequence complexity

Sequence complexity is calculated based on Shannon’s entropy. For a DNA sequence of length with alphabet {A, T, C, G}, the number of each k-mer is stored as an array

where m is the number of a certain k-mer, and . For example, if , then since there are 4 ‘A’s, 4 ‘C’s and 5 ‘G’s. Then,

The complexity of is the smallest of e1, e2 and e3.

Optimization of PDRs

A PDR is defined by its start coordinate and stop coordinate (closed interval), where is the length of the PDR (40 by default).

Risk of a PDR

The risk of the PDR is then defined as , where r is the risk array. Each PDR is selected within a certain region , with start coordinate c1 and stop coordinate c2 (closed interval), and . The risk of all possible PDRs within is calculated, and PDRs with risk below percentile are considered candidate PDRs. Here percentile is defined as a PDR risk threshold below which percentage of PDRs fall. Therefore, a lower means a more stringent selection on PDR candidates. is set to 30 by default.

Generation of a set of PDRs

Starting from the left end of the risk array and the targeted sequence, the first PDR has

Then the start coordinate of the first PDR is selected. Here starts at 1 for simplicity. The first PDR is where the leftmost forward primer (fP) will be generated. For the rest PDRs, there are three restrictions: 1) PDRs should not overlap with each other, 2) user-defined amplicon length, 3) the targeted sequence is fully covered. 2) can be described as,

where , is minimum amplicon length and is maximum amplicon length. The two PDRs starting at and will generate a forward primer (fP) and reverse primer (rP), respectively, thus denoted as a PDR pair. Therefore, the third restriction can be more precisely described as: targeted sequence is fully covered with regions between all PDR pairs, denoted as inserts. Note that the final amplicon length might be slightly shorter than since primers are generated within PDRs. The second PDR has

The start coordinate of the second PDR is selected as . Then we have

Starting from the 5th PDR or the 3rd PDR pair,

where . The generation of PDRs will stop when there is no room to place another PDR pair.

Loss of a PDR set

The Loss of a PDR set is defined as the total risk of the top 10% high-risk PDRs. For an input genome of length , the number of PDR sets generated is

Optimizing primer candidates with SADDLE

The PDR set with the lowest Loss is input to SADDLE 11, with default parameters: temperature as 60°C, salinity as 0.18, max primer length as 36, max (Gibbs free energy) as −11.8, InitSATemp (initial simulated annealing temperature) as 1000, NUMSTEPS (number of simulated annealing steps) as 10, ZEROSTEPS (number of zero simulated annealing temperature) as 10, and TimePerStep (iterations per simulated annealing temperature) as 1000. SADDLE will generate primer candidates for each PDR and optimize the combination of primer candidates to minimize primer dimer. One primer candidate is selected for each PDR as the final PCR tiling design output.

Prediction of non-specific amplicons

The prediction of non-specific amplicons starts with running BLAST through each single primer, with the following parameters set to the NCBI BLAST+ program 21: evalue as 5000, reward as 1, penalty as −1, gapopen as 2, gapextend as 1. For each BLAST hit, the BLAST program outputs the location and orientation of that hit. A single primer could have multiple BLAST hits, distributed to different chromosomes. For each chromosome, the location and orientation of hits of all primers are analyzed together. If two hits are close enough and the orientations are legitimate for PCR, that pair of hits is reported as a predicted non-specific amplicon.

Calculation of Nextstrain nucleotide entropy

Nextstrain 19 calculates Shannon’s entropy for each nucleotide position of the reference SARS-CoV-2 genome based on MSA of genomes available on GISAID 9. Here we include global genomes date from Dec. 21, 2019 to Dec. 04, 2022. Entropy at a given position is calculated as below. Suppose we have genomes. At position , genomes has ‘A’, genomes has ‘T’, genomes has ‘C’, genomes has ‘G’. Suppose , , and are non-zero.

where is an array and is entropy at position . Of 7,774 locations with non-zero entropy, we selected 1,517 locations with entropy greater than 0.01 and input to Olivar as SNP locations and frequencies. We used the reference genome provided by Nextstrain (GenBank MN908947.3) without a BLAST database of non-targeted sequences. Other parameters are kept as default.

SNP calling with Variant Database

We downloaded MSA and metadata of GISAID SARS-Cov-2 genomes before Feb. 28, 2022 and used Variant Database 20 (version 2.4) to output SNPs of lineage B.1.617.2 and B.1.1.529, with GISAID genome EPI_ISL_402124 as reference for coordinates. We used the command “frequencies <cluster>“ to list the frequencies of individual mutations for B.1.617.2 and B.1.1.529 separately. Insertions are not generated due to the limitations of the Variant Database. Of the 10,000 output SNPs, we kept 440 SNPs with a frequency greater than 0.01 and input to Olivar.

In silico comparison of Olivar and PrimalScheme

For Olivar input, we used GISAID genome EPI_ISL_402124 as a reference, a BLAST database of human genome assembly GRCh38.p13 as non-targeted sequences, and 440 SNPs of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.617.2 and B.1.1.529 generated with Variant Database (described above). For Olivar and PrimalScheme (version 1.4.1), desired amplicon length is set to 252nt to 420 nt. Other Olivar and PrimalScheme parameters are kept as default.

Input genomes for PrimalScheme

100 artificial genomes are created, bearing the same 440 SNPs input to Olivar. Each SNP is randomly put back to of the 100 copies of the GISAID reference EPI_ISL_402124,

where is the frequency of the SNP. We did not keep the original frequency for high-frequency SNPs in the artificial genomes because PrimalScheme will consider a position to be conserved if the vast majority of genomes have the same SNP and that position will not be avoided.

Sample preparation and quantification

Synthetic RNA control for SARS-CoV-2 is purchased from Twist Bioscience (part number 105204, GISAID ID EPI_ISL_6841980). Time-weighted composite samples of raw wastewater were collected every 1h for 24 h from the influent of the two domestic wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), CB and KB, on two separate dates (Aug. 8 and Aug. 15, 2022). Samples were kept on ice during transport and stored at 4C° in the laboratory to be processed within 24 hours of collection. Sample concentration using HA filtration and bead beating methods, as well as RNA extraction method using the ChemagicTM Prime Viral DNA/RNA 300 Kit H96 (Chemagic, CMG-1433, PerkinElmer) were as decribed in ref. 6. To normalize synthetic RNA control to Ct values of 18 and 35, One-step RT-qPCR were performed with qPCRBIO probe 1-Step Go LoROX (PB25.41, PCR Biosystems) on the QuantStudio 3 Real Time PCR System (A28567, Applied Biosystems) as previously described in ref. 22. These two Ct bounds were selected to represent the high and low concentrations of SARS-CoV-2. SARS-CoV-2 concentrations of wastewater samples were quantified using RT-ddPCR on a QX200 AutoDG Droplet Digital PCR System (Bio-Rad) and a C1000 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad) in 96-well optical plates, as previously described in ref. 6.

Multiplexed PCR, library preparation and sequencing

ARTIC V4.1 primer panel was purchased from IDT (Artic V4.1 NCOV-2019 Panel, 500rxn, 10011442). Olivar primers were ordered in tubes from Sigma Aldrich and mixed by hand to achieve the final concentration of 15 nanomolar (nM) per primer. Reverse transcription of synthetic RNA control and extracted wastewater RNA were conducted using 8 uL of sample RNA and LunaScript RT SuperMix kit (NEB, E3010), as described in ref. 17. To avoid bias attributed to reverse transcription, for each sample, the total volume of 10 uL cDNA product were gently homogenized by pipetting then divided into four 2.5 uL aliquots for the downstream PCR amplification reactions (using primer pool 1 and 2 of ARTIC V4.1, and using primer pool 1 and 2 of Olivar). PCR amplification was also performed using Q5 Hot Start High-Fidelity 2X Master Mix (NEB M0494) as described in ref. 17. PCR products were purified using AmPureTM XP beads (Beckman Coulter Inc., A63880). A high bead-to-sample ratio of 1.8 was applied to maximize the potentials of capturing PCR byproduct. Purified DNA samples were normalized to 20 ng/uL in 25 uL and submitted for amplicon sequencing service at Azenta (EZ-Amplicon), with paired-end (2× 250bp), adapter trimmed Illumina reads output. The concentration of amplicons was measured using Qubit dsDNA HS kit and a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Invitrogen).

Analysis of sequencing data

Paired-end sequencing reads are mapped to the reference genome (GISAID ID EPI_ISL_402124) with Bowtie2 (version 2.4.5) 23, with maximum fragment length for valid paired-end alignments (-X) set to 1000. Coverage of each reference position is calculated as the number of reads overlapping that position, using PySAM (version 0.19.1) 24. Sequencing reads are also mapped to amplicon sequences with Bowtie2, and the coverage for each amplicon is the number of read pairs mapped to that amplicon.

DISCUSSION

We have described and presented results on Olivar, the first fully automated, end-to-end computational method for tiled primer design. Olivar quantifies undesired sequence features with single nucleotide risk scores across the whole genome, enabling efficient evaluation and optimization of primer design regions and ultimately improving the performance of output primers. In-silico validation shows that Olivar can effectively avoid high-risk regions in the targeted genome, including SNPs, extreme GC content, low sequence complexity, and repetitive sequences. Compared with the state-of-art PCR tiling design software PrimalScheme, Olivar has fewer SNPs overlapping with primer and less predicted primer dimer and non-specific priming. In addition, in a head-to-head comparison with the most commonly used SARS-CoV-2 primer set ARTIC v4.1, Olivar offers equivalent to higher mapping rates and similar genomic coverage on both synthetic RNA samples and wastewater samples. These mapping rates and coverage improvements highlight that Olivar can provide robust designs capable of being produced at lower sequencing costs. Moreover, the ARTIC primer set has undergone several versions of optimization whereas the experimentally validated Olivar primers were automatically designed, saving significant time and cost that comes with multiple rounds of manual redesign.

To highlight one of the algorithmic innovations, Olivar uses locations and frequencies to represent sequence variation. Another way to represent sequence variation is using a group of highly similar genomes (e.g, strains of a certain virus) 4. While the latter is usually more readily available than the former for viruses and bacteria, it needs more computational resources to evaluate the sensitivity of a PDR for a group of genomes through local alignment or multiple sequence alignment (MSA), especially when the number of genomes is large. For well-studied pathogens, such as SARS-CoV-2 and human monkeypox virus, the MSA Olivar uses is updated in real-time from the public database GISAID 9 and coordinates and frequencies of nucleotide change are available at Nextstrain 19. For species without publicly available MSA, tools such as Parsnp 25 can efficiently build core-genome alignment and make variant calls.

Furthermore, Olivar is a versatile approach not limited to designing tiled amplicons for viral genomes. For example, PCR tiling is frequently used in applications such as full-length sequencing of entire genes 26. An Olivar risk array could not only guide the design of tiled amplicons, but also one or a few amplicons when there is no strict requirement on amplicon location (e.g., pathogen detection with digital PCR 6 and measuring copy number variation 27), by selecting genomic regions with low-risk scores. This could help users quickly find signature sequences ideal for downstream design, such as non-repetitive and highly conserved regions. Furthermore, the modular nature of calculating a risk array allows the customization of risk components. For example, in applications where SNPs are needed to distinguish similar species or strains of pathogens 28, users could define risk scores for sensitivity and specificity to find sequences targeting desired strains while avoiding unwanted ones.

While Olivar represents an important advance toward rapidly detecting novel pathogens, it is not without limitations. One user-defined input for Olivar is the BLAST database for background non-targeted sequences. While we provide the BLAST database for the human genome as it is frequently considered as background, users likely will need more comprehensive and application-specific databases to reduce non-specific byproducts further. Leveraging GC content and sequence complexity can also help avoid low-complexity sequences. We are actively building more background databases for various scenarios, such as pathogen detection in wastewater. Additional background sequence screening improvements will be included in future updates of Olivar.

CONCLUSION

Olivar is, to our knowledge, the first open-source computational tool for fully automatic design of multiplexed PCR tiling assays while considering SNPs, primer dimers, and non-specific amplification simultaneously, bearing the potential of significantly reducing manual redesign while maintaining low sequencing cost. We anticipate that Olivar will aid the surveillance of future infectious disease outbreaks by providing an automated tool for designing tiled amplicons.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Nina G. Xie for experimental advice.

FUNDING

This work has been supported by CDC contract 75D30122C14709, the Big-Data Private-Cloud Research Cyberinfrastructure MRI-award funded by NSF under grant CNS-1338099, and by Rice Universitys Center for Research Computing (CRC). B.K. was supported by the NLM Training Program in Biomedical Informatics and Data Science (Grant: T15LM007093).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No competing interest is declared.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Sequencing data in this study is available at NCBI SRA under BioProject PRJNA911448. Sequences and coordinates of primers, Nextstrain entropy, location and frequencies of SNPs, and mapping rates of sequencing samples are available in Supplementary Dataset (also available at https://gitlab.com/treangenlab/olivar).

REFERENCES

- [1].Chiu Charles Y. Viral pathogen discovery. Current opinion in microbiology, 16(4):468–478, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Metsky Hayden C, Matranga Christian B, Wohl Shirlee, Schaffner Stephen F, Freije Catherine A, Winnicki Sarah M, West Kendra, Qu James, Baniecki Mary Lynn, Gladden-Young Adrianne, et al. Zika virus evolution and spread in the americas. Nature, 546(7658):411–415, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kousathanas Athanasios, Pairo-Castineira Erola, Rawlik Konrad, Stuckey Alex, Odhams Christopher A, Walker Susan, Russell Clark D, Malinauskas Tomas, Wu Yang, Millar Jonathan, et al. Whole genome sequencing reveals host factors underlying critical covid-19. Nature, pages 1–10, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Quick Joshua, Grubaugh Nathan D, Pullan Steven T, Claro Ingra M, Smith Andrew D, Gangavarapu Karthik, Oliveira Glenn, Robles-Sikisaka Refugio, Rogers Thomas F, Beutler Nathan A, et al. Multiplex pcr method for minion and illumina sequencing of zika and other virus genomes directly from clinical samples. Nature protocols, 12(6):1261–1276, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Metsky Hayden C, Siddle Katherine J, Gladden-Young Adrianne, Qu James, Yang David K, Brehio Patrick, Goldfarb Andrew, Piantadosi Anne, Wohl Shirlee, Carter Amber, et al. Capturing sequence diversity in metagenomes with comprehensive and scalable probe design. Nature biotechnology, 37(2):160–168, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lou Esther G, Sapoval Nicolae, McCall Camille, Bauhs Lauren, Carlson-Stadler Russell, Kalvapalle Prashant, Lai Yanlai, Palmer Kyle, Penn Ryker, Rich Whitney, et al. Direct comparison of rt-ddpcr and targeted amplicon sequencing for sars-cov-2 mutation monitoring in wastewater. Science of The Total Environment, 833:155059, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Samorodnitsky Eric, Jewell Benjamin M, Hagopian Raffi, Miya Jharna, Wing Michele R, Lyon Ezra, Damodaran Senthilkumar, Bhatt Darshna, Reeser Julie W, Datta Jharna, et al. Evaluation of hybridization capture versus amplicon-based methods for whole-exome sequencing. Human mutation, 36(9):903–914, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Gohl Daryl M, Garbe John, Grady Patrick, Daniel Jerry, Watson Ray HB, Auch Benjamin, Nelson Andrew, Yohe Sophia, and Beckman Kenneth B. A rapid, cost-effective tailed amplicon method for sequencing sars-cov-2. BMC genomics, 21(1):1–10, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Khare Shruti, Gurry Céline, Freitas Lucas, Schultz Mark B, Bach Gunter, Diallo Amadou, Akite Nancy, Ho Joses, Lee Raphael TC, Yeo Winston, et al. Gisaids role in pandemic response. China CDC Weekly, 3(49):1049, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Wheeler David L, Barrett Tanya, Benson Dennis A, Bryant Stephen H, Canese Kathi, Chetvernin Vyacheslav, Church Deanna M, DiCuccio Michael, Edgar Ron, Federhen Scott, et al. Database resources of the national center for biotechnology information. Nucleic acids research, 36(suppl_1):D13–D21, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Xie Nina G, Wang Michael X, Song Ping, Mao Shiqi, Wang Yifan, Yang Yuxia, Luo Junfeng, Ren Shengxiang, and Zhang David Yu. Designing highly multiplex pcr primer sets with simulated annealing design using dimer likelihood estimation (saddle). Nature communications, 13(1):1–10, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Wilkinson Sam. Erroneous mutations associated with 64_l-60_r primer-dimer in artic 4/4.1 — community.artic.network. https://community.artic.network/t/erroneous-mutations-associated-with-64-l-60-r-primer-dimer-in-artic-4-4-1/419/1, 2022. [Accessed 17-Jan-2023]. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Davis James J, Long S Wesley, Christensen Paul A, Olsen Randall J, Olson Robert, Shukla Maulik, Subedi Sishir, Stevens Rick, and Musser James M. Analysis of the artic version 3 and version 4 sars-cov-2 primers and their impact on the detection of the g142d amino acid substitution in the spike protein. Microbiology spectrum, 9(3):e01803–21, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Itokawa Kentaro, Sekizuka Tsuyoshi, Hashino Masanori, Tanaka Rina, and Kuroda Makoto. Disentangling primer interactions improves sars-cov-2 genome sequencing by multiplex tiling pcr. PloS one, 15(9):e0239403, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gervais Alain L, Marques Maud, and Gaudreau Luc. Pcrtiler: automated design of tiled and specific pcr primer pairs. Nucleic acids research, 38(suppl_2):W308–W312, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wingo Thomas S, Kotlar Alex, and Cutler David J Mpd: multiplex primer design for next-generation targeted sequencing. BMC bioinformatics, 18(1):1–5, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Tyson John R, James Phillip, Stoddart David, Sparks Natalie, Wickenhagen Arthur, Hall Grant, Choi Ji Hyun, Lapointe Hope, Kamelian Kimia, Smith Andrew D, et al. Improvements to the artic multiplex pcr method for sars-cov-2 genome sequencing using nanopore. BioRxiv, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Zhang Jinny X, Yordanov Boyan, Gaunt Alexander, Wang Michael X, Dai Peng, Chen Yuan-Jyue, Zhang Kerou, Fang John Z, Dalchau Neil, Li Jiaming, et al. A deep learning model for predicting next-generation sequencing depth from dna sequence. Nature communications, 12(1):1–10, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Hadfield James, Megill Colin, Bell Sidney M, Huddleston John, Potter Barney, Callender Charlton, Sagulenko Pavel, Bedford Trevor, and Neher Richard A. Nextstrain: real-time tracking of pathogen evolution. Bioinformatics, 34(23):4121–4123, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].West Anthony P, Wertheim Joel O, Wang Jade C, Vasylyeva Tetyana I, Havens Jennifer L, Chowdhury Moinuddin A, Gonzalez Edimarlyn, Fang Courtney E, Lonardo Steve S Di, Hughes Scott, et al. Detection and characterization of the sars-cov-2 lineage b. 1.526 in new york. Nature communications, 12(1):1–10, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Camacho Christiam, Coulouris George, Avagyan Vahram, Ma Ning, Papadopoulos Jason, Bealer Kevin, and Thomas L Madden. Blast+: architecture and applications. BMC bioinformatics, 10(1):1–9, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].LaTurner Zachary W, Zong David M, Kalvapalle Prashant, Gamas Kiara Reyes, Terwilliger Austen, Crosby Tessa, Ali Priyanka, Avadhanula Vasanthi, Santos Haroldo Hernandez, Weesner Kyle, et al. Evaluating recovery, cost, and throughput of different concentration methods for sars-cov-2 wastewater-based epidemiology. Water research, 197:117043, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Langmead Ben and Steven L Salzberg. Fast gapped-read alignment with bowtie 2. Nature methods, 9(4):357–359, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Gilman Paul, Janzou Steven, Guittet Darice, Freeman Janine, DiOrio Nicholas, Blair Nathan, Boyd Matthew, Neises Ty, and Wagner Michael. Pysam (python wrapper for system advisor model” sam”). Technical report, National Renewable Energy Lab.(NREL), Golden, CO (United States), 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Treangen Todd J, Ondov Brian D, Koren Sergey, and Phillippy Adam M. The harvest suite for rapid core-genome alignment and visualization of thousands of intraspecific microbial genomes. Genome biology, 15(11):1–15, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Schenk Desiree, Song Gang, Ke Yue, and Wang Zhaohui. Amplification of overlapping dna amplicons in a single-tube multiplex pcr for targeted next-generation sequencing of brca1 and brca2. PLoS One, 12(7):e0181062, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Wu Lucia Ruojia, Dai Peng, Wang Michael Xiangjiang, Chen Sherry Xi, Cohen Evan N, Jayachandran Gitanjali, Zhang Jinny Xuemeng, Serrano Angela V, Xie Nina Guanyi, Ueno Naoto T, et al. Ensemble of nucleic acid absolute quantitation modules for copy number variation detection and rna profiling. Nature communications, 13(1):1–9, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Cleary Brian, Brito Ilana Lauren, Huang Katherine, Gevers Dirk, Shea Terrance, Young Sarah, and Alm Eric J. Detection of low-abundance bacterial strains in metagenomic datasets by eigengenome partitioning. Nature biotechnology, 33(10):1053–1060, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Sequencing data in this study is available at NCBI SRA under BioProject PRJNA911448. Sequences and coordinates of primers, Nextstrain entropy, location and frequencies of SNPs, and mapping rates of sequencing samples are available in Supplementary Dataset (also available at https://gitlab.com/treangenlab/olivar).