Abstract

Tissue functions are determined by the types and ratios of cells present, but little is known about self-organizing principles establishing correct cell type compositions. Mucociliary airway clearance relies on the correct balance between secretory and ciliated cells, which is regulated by Notch signaling across mucociliary systems. Using the airway-like Xenopus epidermis, we investigate how cell fates depend on signaling, how signaling levels are controlled, and how Hes transcription factors regulate cell fates. We show that four mucociliary cell types each require different Notch levels and that their specification is initiated sequentially by a temporal Notch gradient. We describe a novel role for Foxi1 in the generation of Delta-expressing multipotent progenitors through Hes7.1. Hes7.1 is a weak repressor of mucociliary genes and overcomes maternal repression by the strong repressor Hes2 to initiate mucociliary development. Increasing Notch signaling then inhibits Hes7.1 and activates first Hes4, then Hes5.10, which selectively repress cell fates. We have uncovered a self-organizing mechanism of mucociliary cell type composition by competitive de-repression of cell fates by a set of differentially acting repressors. Furthermore, we present an in silico model of this process with predictive abilities.

Keywords: Xenopus, airway epithelium, development, multi-ciliated cells, mucus, basal cells, mathematical modeling

Introduction:

Tissue functions are determined by morphology and by cell type composition, the types, numbers and ratios of cells present, but little is known about the self-organizing principles that govern the establishment of correct cell type compositions. Mucociliary epithelia line various organs in animals(Walentek, 2021b; Walentek and Quigley, 2017), including the mammalian airways and the epidermis of Xenopus laevis embryos, where they provide an innate immune barrier through mucociliary clearance(Dubaissi et al., 2014; Whitsett, 2018). This relies on the correct balance between secretory and ciliated cells, which is varied across organs and adapted to location within an organ(Volckaert and De Langhe, 2014). Alterations in cell type composition are characteristic of airway diseases, such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cancer(Hogan et al., 2014). Lung diseases are a global health burden, but the development of treatments is impeded by our incomplete understanding of the mechanisms regulating correct mucociliary cell type compositions(Walentek, 2021a). Notch regulation of ciliated and secretory cells was shown to be evolutionarily conserved in mucociliary epithelia across species, and frequently disturbed in human airway diseases(Deblandre et al., 1999; Hogan et al., 2014; Kiyokawa and Morimoto, 2020; Rock et al., 2011; Walentek, 2021a). Despite efforts to unravel how Notch signaling regulates mucociliary patterning, precisely how cell fates depend on signaling levels, how signaling levels are generated, and how signaling is interpreted by cells during fate decisions have remained enigmatic. Here, we show that four mucociliary cell types require different Notch signaling levels for specification. Cell fates are initiated sequentially by a temporal Notch gradient generated by ligand-expressing multipotent progenitors. We describe a novel role of the forkhead-box transcription factor Foxi1 in the generation of multipotent progenitors through the activation of Hes7.1, which is required to overcome a maternally deposited repression system. Further cell fate choices are governed by the integration of Notch signaling levels through additional Hes factors and Hes-independent mechanisms. Finally, we present a mathematical model that recapitulates the establishment of mucociliary cell type composition in silico, which can be used to predict critical gaps in our understanding of mucociliary patterning mechanisms in development and disease.

Results:

All mucociliary cell types are specified at distinct Notch levels

In the Xenopus embryonic mucociliary epidermis, ionocytes (ISCs) and multi-ciliated cells (MCCs) are specified prior to small secretory cells (SSCs)(Dubaissi et al., 2014; Walentek et al., 2014). Elevated ΔN-tp63 expression induces mature basal stem cells (BCs) and blocks all other cell fates, terminating cell fate specification(Haas et al., 2019). ISCs and MCCs are generated in low Notch conditions, while secretory cells are induced by Notch activation(Deblandre et al., 1999; Quigley and Kintner, 2017; Quigley et al., 2011; Walentek, 2018). It was proposed that early and late progenitors with different potential generate ISCs/MCCs and SSCs, respectively(Briggs et al., 2018).

To elucidate how different Notch signaling levels affect cell type composition, we strongly reduced signaling-induced transcription using dominant-negative RBPJ (suh-dbm) or overactivated it using Notch intracellular domain (nicd). At stage (st.) 32, we immuno-stained for cell type markers to analyze control and targeted (=GFP+) specimens by confocal microscopy (Fig. S1A)(Walentek, 2018). Notch inhibition increased ISC and decreased SSC numbers, but did not increase MCC numbers (Fig. 1A,B; S1A). Notch activation lead to a loss of ISCs and MCCs, but intermediate (med.) levels expanded SSC numbers, while high levels suppressed SSCs (Fig. 1A; S1A).

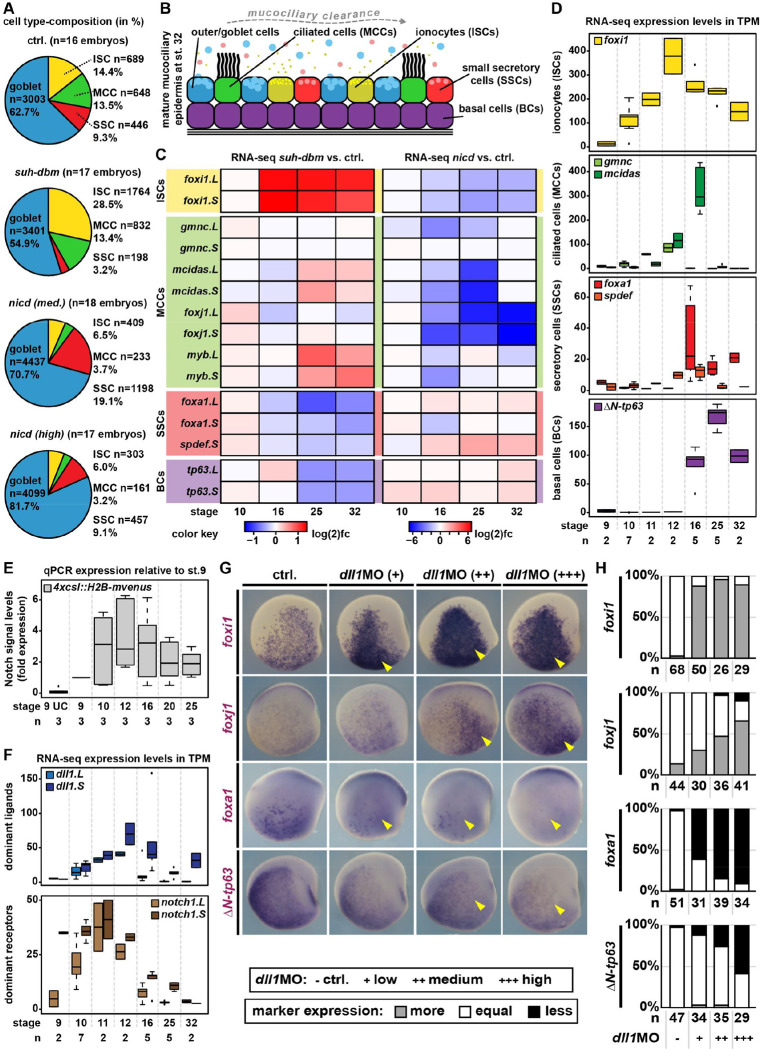

Figure 1: Cell fate specification in response to a temporal Notch gradient.

A: Quantification of epidermal cell types after Notch manipulations and immunofluorescent staining at st. 32. B: Schematic representation of mucociliary epidermal cell types. C: Changes in cell type marker expression relative to stage-matched controls after manipulation of Notch signaling in Xenopus mucociliary organoids (RNA-seq). D,F: Expression levels of indicated genes in unmanipulated mucociliary organoids across different stages of development (RNA-seq). E: Notch reporter activity in mucociliary organoids relative to 4xcsl::H2B-mvenus injected st. 9 samples over time (qPCR). G: Lateral view, WMISH for indicated transcripts at st. 16/17 in controls and after knockdown of dll1. +=low dose, ++=medium dose, +++=high dose. H: Quantification of results depicted in G. Expression levels were scored more, equal, less expression on the injected vs. uninjected side.

Using different concentrations of suh-dbm or nicd mRNA overexpression, we confirmed the graded effects of Notch on cell type composition by whole mount in situ hybridization (WMISH) at the end of specification (st. 16/17) (Fig. S1B,C). These data indicated that ISCs (foxi1) were generated at low levels, MCCs (foxj1) at low to medium levels, SSCs (foxa1) at medium to high levels, and that BCs (ΔN-tp63) were promoted by NICD. Goblet cells were not analyzed, as they emerge earlier through asymmetric cell division(Huang and Niehrs, 2014).

Next, we analyzed transcriptional changes over time in control and manipulated Xenopus mucociliary organoids by mRNA-sequencing (RNA-seq). Based on both published(Haas et al., 2019; Quigley and Kintner, 2017) and our own data, we defined marker sets for each cell type including factors necessary and sufficient to induce cell fates (Fig. S2A,B). Expression dynamics of these markers confirmed that cell fate specification starts at st. 9/10 (shortly after mid-blastula transition, MBT(Jukam et al., 2017)) and is largely accomplished by st. 16 as early markers increase only between st. 9–16 (Fig. S2A,B).

RNA-seq at st. 10, 16, 25 and 32 after manipulations confirmed that Notch inhibition strongly induced ISCs, decreased MCC marker expression at st. 16, and suppressed SSCs as well as BCs (Fig. 1C; S2B). Interestingly, MCC marker expression recovered during later stages, which might explain why MCC numbers are not reduced by Notch inhibition. Notch overactivation suppressed ISCs and MCCs, but promoted expression of SSC and BC markers (Fig. 1C; S2B).

Contrary to the current assumption that ISCs and MCCs are specified both by the lack of Notch signaling, these data indicate that MCCs are specified at higher Notch levels than ISCs, but at lower levels than SSCs and BCs.

Cell types are specified sequentially by a temporal Notch signaling gradient

We plotted RNA-seq expression levels (normalized to TPM) of cell type master regulators over developmental time. This showed that foxi1 (ISCs) was expressed first and peaked by st. 12, while gmnc and mcidas (MCCs) were expressed from st. 10/11 and mcidas peaked at st. 16 (Fig. 1D). foxa1 and spdef (SSCs) expression started at st. 11/12 and either peaked at st. 16 (spdef) or further increased until st. 32 (foxa1), while ΔN-tp63 (BCs) expression started at st. 16 and peaked at st. 25 (Fig. 1D). These results were confirmed by WMISH (Fig. S2C,D) and revealed the sequential initiation of cell type specification in the Xenopus epidermis.

These results predicted a systemic increase in Notch signaling during specification. Using quantitative RT-PCR (qPCR) on mucociliary organoids injected with a Notch reporter (4xcsl::H2B-mvenus)(Nowotschin et al., 2013), we detected an increase in signaling at st. 9–12, sustained activity until st. 16, and decrease in activity until st. 25 (Fig. 1E).

Delta-like 1 (Dll1) was previously implicated in mucociliary patterning(Deblandre et al., 1999), but other Notch components were not systematically analyzed so far. We found that dll1 and notch1 were the increasingly and dominantly expressed ligand and receptor, respectively (Fig. 1F and S3A). RNA-seq and WMISH revealed that notch1 increased until st. 11 and was homogenously expressed in the basal layer of the epidermis, while dll1 expression increased for a longer time and was expressed by differentiating cells (starting to undergo intercalation;(Deblandre et al., 1999)) (Fig. 1F; S3B,C).

To validate that graded Dll1 levels could tune cell type composition, we knocked down dll1 by different (low to high) morpholino-oligonucleotide (MO) concentrations. Analysis of cell type markers at st. 16/17 confirmed that modifying Dll1 levels sufficed to coordinately shift cell type ratios (Fig. 1G,H). Thus, the initiation of and temporal increase in ligand expression were critical parameters for patterning the mucociliary system.

Loss-of-function experiments targeting all ligands and receptors (except for dll4) followed by WMISH at st. 16/17 revealed that the depletion of any ligand or receptor affected mucociliary patterning but to variable degrees (Fig. S4). Especially SSCs that are specified last, were robustly reduced after knockdown of ligands and receptors (Fig. S4). Thus, the sum of all ligands and receptors generates Notch levels required for a correct cell type composition, similar to findings in the mammalian airway epithelium(Morimoto et al., 2012).

In conclusion, we found that mucociliary cell types specification is initiated sequentially, from low Notch-dependent ISCs to high Notch-dependent BCs. The increase in signaling is predominantly achieved by ligand expression from a growing pool of differentiating cells.

Foxi1 induces ligand-expressing multipotent progenitors

Similar expression dynamics (Fig. 1D,F) and previous reports suggested a role for Foxi1 in dll1 regulation(Quigley and Kintner, 2017). Analysis of ligand and receptor expression after Notch manipulations as well as after depletion of MCCs, SSCs or BCs confirmed that blocking specification by NICD suppressed dll1 and dlc.L ligands, and revealed the induction of notch receptors (Fig. S5A)(Dubaissi et al., 2014; Haas et al., 2019; Quigley and Kintner, 2017). In all other conditions, where foxi1 expression was stimulated, dll1 and dlc.L were increased (Fig. S5A).

We overexpressed foxi1, mcidas, foxj1, foxa1 or ΔN-tp63, and analyzed dll1 and dlc induction before the onset of their endogenous expression. Only foxi1 robustly induced dll1/dlc (Fig. 2A; S5B,C). To test whether foxi1 was acting directly, we analyzed induction at MBT (st. 8) and additionally, at the onset of any transcription (st.6/7), which showed dll1/dlc induction at both stages (Fig. 2B; S5D,E). Conversely, depletion of Foxi1 prevented dll1 expression and caused embryonic lethality (Fig. S5F–H), in line with previous reports(Mir et al., 2007).

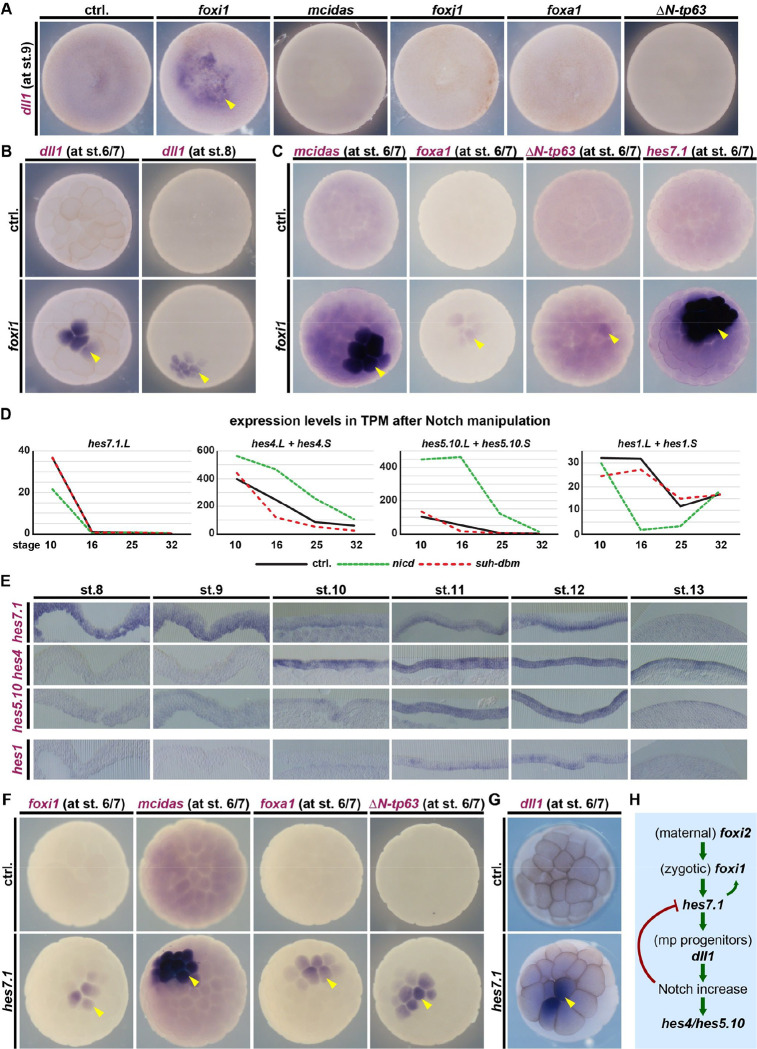

Figure 2: Foxi1 induces multipotent ligand-expressing progenitors via hes7.1.

A-C, F,G: Animal view, WMISH. A: dll1 at st. 9 in controls and after overexpression of master cell type inducers. Only foxi1 induces dll1 expression (yellow arrowhead). B: dll1 at st. 6/7 and 8 in controls and after foxi1 (induction=yellow arrowhead). C: Marker gene expression at st. 6/7 in controls and after foxi1 (induction=yellow arrowhead). D: Expression levels of indicated hes transcripts in unmanipulated mucociliary organoids (black line) and after Notch manipulations (loss=red line; gain=green line) across different stages of development (RNA-seq). E: Epidermis sections, WMISH for indicated hes transcripts from st. 8 to st. 13. F,G: Marker gene expression at st. 6/7 in controls and after hes7.1 (induction=yellow arrowhead). H: Schematic summary of Notch, hes and dll1 regulation in multipotent progenitors.

Foxi1 could have an additional role during mucociliary development besides ISC specification(Mir et al., 2007; Yan et al., 2006). We overexpressed foxi1 and analyzed mucociliary markers at st. 6/7. We found strong induction of mcidas (MCCs) as well as weaker induction of foxa1 (SSCs) and ΔN-tp63 (BCs) by Foxi1 (Fig. 2C; S5I). This supported a novel role for Foxi1 in the induction of multipotent mucociliary progenitors.

In summary, the onset of foxi1 expression induces mucociliary development and multipotent mucociliary progenitors, which predominantly express dll1/dlc ligands to increase Notch signaling during cell fate specification.

Foxi1 and Notch regulate sequential Hes transcription factor expression

Notch signaling confers cell fate decisions through Hairy enhancer of split (Hes/Hey) transcription factors. Multiple Hes proteins have been implicated in mucociliary patterning across models, but how they are employed for cell fate decisions remains unresolved(Gomi et al., 2015; Morimoto et al., 2010; Ou-Yang et al., 2013; Tsao et al., 2008; Tsao et al., 2009).

We analyzed how all known Xenopus hes/hey genes react to Notch manipulations, and investigated their temporal expression dynamics in mucociliary organoids by RNA-seq (Fig. S6A,B). We found that hes7 paralogs were expressed first, followed by hes4 paralogs, and hes1/hes5 paralogs (Fig. S6B). Within the four paralog groups, hes7.1.L (hes7.1), hes4.L/.S (hes4), hes5.10.L/.S (hes5.10), and hes1.L/.S (hes1) were the dominantly expressed members.

hes7.1 and hes1 were inhibited by NICD, due to auto-(Kageyama et al., 2007) or Notch repression(Takada et al., 2005), while hes4 and hes5.10 were induced by NICD, with hes5.10 showing a stronger response (Fig. 2D; S6A). We confirmed the expression of these hes genes by WMISH and found that hes7.1 was expressed only in the deep cell layer; hes4 and hes5.10 were expressed across both cell layers with variable expression levels between individual cells; and hes1 was expressed weakly and only in a few cells (Fig. 2E; S6C,D).

These data indicate that hes7.1 is expressed in early progenitors and turned off by increased Notch, suggesting a potential role in the initiation of mucociliary patterning. We overexpressed hes7.1 and analyzed cell type marker induction. hes7.1 was able to induce all markers as well as dll1 at st. 6/7 (Fig. 2F,G; 3A; S7A), similar to Foxi1. Overexpression of foxi1 induced hes7.1 expression at st. 6/7, while foxi1MO inhibited hes7.1 expression at st. 9 (Fig. 2C; S7B–D).

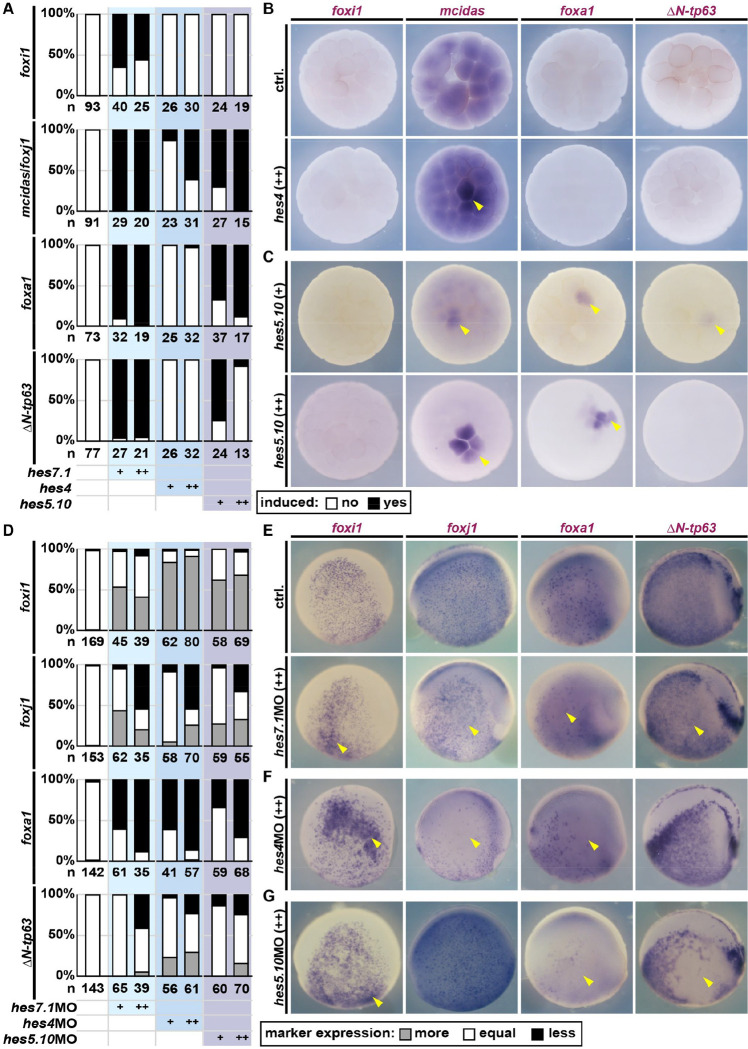

Figure 3: Hes factors regulate mucociliary cell fates.

A: Quantification of results depicted in B,C. B,C: Animal view, WMISH. Marker gene expression at st. 6/7 in controls and after overexpression of indicated hes, +=low dose; ++=high dose (induction=yellow arrowhead). D: Quantification of results depicted in E-G. Expression levels were scored more, equal, less expression on the injected vs. uninjected side. E-G: Lateral view, WMISH. Marker gene expression at st. 16/17 in controls and after knockdown of indicated hes, +=low dose; ++=high dose (changes in expression=yellow arrowhead).

Taken together, we identified a set of sequentially expressed and Notch-regulated Hes transcription factors, and found that Foxi1 establishes multipotent mucociliary progenitors, at least in part, by initializing hes7.1.L expression (Fig. 2H).

Hes factors act in a cell type-specific and concentration-dependent manner

hes4 seems to be induced by intermediate and hes5.10 by high Notch levels, which suggests that they could integrate signaling levels during patterning. Interestingly, hes1 expression and its reaction to Notch manipulations argued against a prominent role in cell fate specification in Xenopus, similar to findings from the mouse airways(Tsao et al., 2009).

In induction assays, hes4 only induced MCC fate while hes5.10 induced MCC, SSC and BC fates (Fig. 3A–C; S7E). Graded responses were observed for the induction of MCCs by Hes4, which was more efficient at higher levels, and for BC induction by Hes5.10, which was more efficient at lower levels (Fig. 3A–C; S7E). These results argued for cell type-specificity of hes genes during mucociliary patterning.

To reveal the endogenous effects of these Hes factors, we conducted loss-of-function experiments using low and high MO concentrations, and analyzed marker expression at st. 16/17. Mild (+) and strong (++) knockdown of all Hes factors suppressed SSCs and promoted ISC specification, with hes4MO having the strongest effect (Fig. 3D–G; S7F–H). MCC specification was promoted (hes7.1MO and hes5.10MO) or remained unaffected (hes4MO) after mild knockdown, but was reduced by strong knockdowns of the tested Hes factors (Fig. 3D–G; S7F–H). BCs were relatively unaffected by Hes knockdown (Fig. 3D–G; S7F–H), suggesting the presence of an additional Notch-dependent factor regulating ΔN-tp63.

Thus, we have identified a set of differentially Notch-regulated hes paralogs with sequential expression, which regulate sequential cell fate specification. hes7.1 is first expressed, restricted to progenitors and negatively Notch-regulated. hes4 is activated next at intermediate Notch levels, suppressing ISCs while predominantly promoting MCCs. hes5.10 is activated last by high Notch signaling and required for SSC specification. The overall weak effects of Hes depletions on BCs indicate additional Hes-independent routes of Notch-dependent ΔN-tp63 regulation.

Hes factors act through competitive de-repression of cell fate choices

The Xenopus embryo is largely transcriptionally silent before MBT, in part because of the presence of repressors(Schulz and Harrison, 2019; Skirkanich et al., 2011). Hes factors are repressors, supporting the hypothesis that hes7.1 could induced mucociliary genes by competitive de-repression of a maternally deposited stronger inhibitor(Jukam et al., 2017; Kageyama et al., 2007). Another Hes family member could potentially restrict mucociliary genes pre-MBT(Kageyama et al., 2007).

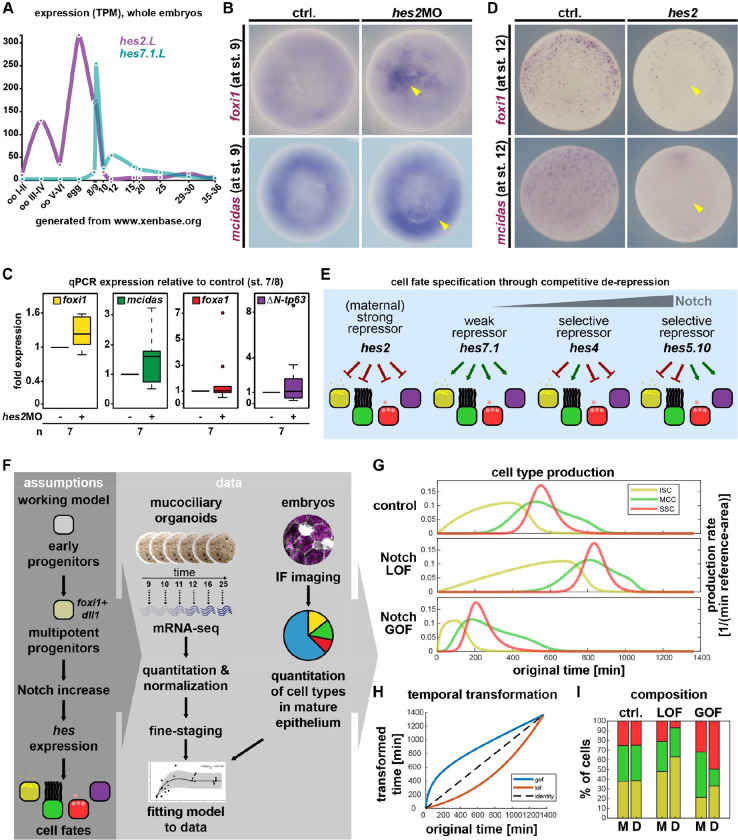

Using xenbase.org(Karpinka et al., 2014), we identified hes2.L as the most abundant maternal deposited hes (Fig. 4A). We knocked down hes2 by MO injections, which robustly induced premature foxi1 at st. 9, while mcidas induction was hard to assess, and foxa1/ΔN-tp63 were not induced (Fig. 4B; S8A). Analysis of mucociliary transcripts by qPCR at st. 7/8 confirmed de-repression of foxi1 and mcidas by hes2MO, and less robust elevation of foxa1 and ΔN-tp63 (Fig. 4C). Conversly, overexpression of hes2 disrupted expression of foxi1 and mcidas at st. 12 (Fig. 4C; S8B,C) as revealed by WMISH.

Figure 4: Competitive de-repression and modeling of mucociliary cell fate decisions.

A: Expression levels of hes2.L and hes7.1.L in whole Xenopus eggs and embryos during early development. (RNA-seq.) B: Animal view, WMISH. Marker gene expression at st. 9 in controls and after knockdown of hes2. (induction=yellow arrowhead). C: Induction of mucociliary marker genes after knockdown of hes2 at st. 7/8 in whole embryos. (qPCR). D: Ventral view, WMISH. Marker gene expression at st. 12 in controls and after overexpression of hes2. (loss of expression=yellow arrowhead). E: Schematic summary of Hes-mediated competitive de-repression of cell fates in Xenopus. F: Schematic representation of minimal-component model building. G-I: In silico modeling of the cell fate specification process. G: Cell type production rates over time (control), and the effect of deceleration (LOF) or acceleration (GOF) on the production rates of ISCs, MCCs, and SSCs. H: The in-silico model could explain Notch loss- (LOF) and gain-of-function (GOF) experiments by deceleration (LOF) or acceleration (GOF) of the whole cell specification process via the depicted nonlinear transformation of the time axis. I: Comparison of modeled [M] and experimentally determined [D] cell type ration of ISCs (yellow), MCCs (green) and SSCs (red).

These results suggest that Hes2 acts as strong maternal repressor of mucociliary genes, and that the weak repressor Hes7.1 de-represses mucociliary gene activity at MBT. Subsequently, Hes4 and Hes5.10 are expressed in a Notch-dependent manner to promote MCC and SSC/BC fates by selective repression of alternative cell fates (Fig. 4E).

A mathematical model emulates mucociliary patterning in silico

To test our understanding of the newly defined self-organizing mechanism (Fig. S8D,E), we used our experimentally-based hypotheses for building a minimal-component mathematical model of the generation of mucociliary cell type ratios (see methods for modeling details), and Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) to fine-stage RNA-seq data (Fig. S9A–C; Table S1). Maximum likelihood estimates of the parameter values were derived by fitting data from time-resolved RNA-seq and cell type quantifications (Fig. 4F; S10A–D). Using this approach, we found a solution (model 1) that recapitulated the endogenous generation of cell type composition, but which failed to fit dynamic ligand levels as well as hes5 expression (Fig. S10A,G), and which failed to predict cell type production phases for Notch gain- and loss-of-function experiments (Fig. S10E,F). Furthermore, prediction of the effect of altering the production rate of ligands from multipotent progenitors contradicted experimental results (Fig. S10H; cf. Fig. 1A,G,H). This indicated, that missing knowledge on how ΔN-tp63 and BCs are maintained even when Notch levels decrease constituted a major gap in the model.

The Ets-transcription factor Spdef is Notch-regulated and required for secretory cells in the mammalian airways(Guseh et al., 2009; Rock et al., 2011), but it is also expressed in human airway basal cells (https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000124664-SPDEF/summary/rna)(Karlsson et al., 2021). In Xenopus mucociliary organoids, spdef expression precedes SSC specification and the initiation of ΔN-tp63 (Fig. 1D). We therefore speculated that Spdef could promote SSC-specification at lower levels, while blocking SSCs and promoting BC at higher levels. Thereby, it could provide a switch for the transition from specification to long-term maintenance of mucociliary patterns, and allowing for the drop in Notch ligand expression after st. 16 (Fig. 1E,F). We introduced these regulatory connections into our mathematical model, re-fitted parameters, and modeled cell type production (model 2) (Fig. 4G; S9C). Model 2 improved fitting quality (Table S2), and could explain Notch gain- and loss-of-function effects by a temporal transformation representing de- (for LOF) and acceleration (for GOF) of cell type production rates (Fig. 4G–I; S10B,D). Furthermore, model 2 also generated results in line with experimental observations on altering ligand expression from multipotent progenitors (Fig. S10I; cf. Fig. 1A,G,H).

Taken together, we were able to generate a minimal component mathematical model that recapitulates normal mucociliary patterning in silico, and that can be used to predict critical gaps in our understanding of mucociliary patterning - in our case, modeling predicts an additional role for Spdef in Notch-mediated regulation of BCs.

Discussion:

We elucidated how a morphogen-like temporal Notch gradient regulates mucociliary cell type composition in Xenopus. We found a novel role for Foxi1 in the induction of hes7.1 to generate Notch ligand-expressing multipotent progenitors, which partially explains why it acts as ectodermal determinant(Mir et al., 2007). Expansion of the progenitor population increases systemic Notch levels, inhibiting hes7.1 and inducing first hes4, then hes5.10 to specify other cell types. This self-organized patterning system leads to sequential initiation of cell type specification, and the generation of correct cell numbers and ratios. Our data indicate that a set of repressors is used to regulate onset of mucociliary development as well as cell fate decisions. This suggests that cell fates are not actively induced, but facilitated by restricting alternative fate choices in multipotent progenitors. Thus, we refer to this mode of regulation as “competitive de-repression”.

foxi1 is induced by maternally deposited Foxi2 at MBT(Cha et al., 2012) and is negatively regulated by Hes4/Hes5.10. Sustained Foxi1 specifies ISC fate, and consequently, ISCs are specified first and only at very low Notch levels. hes4 is induced at intermediate Notch levels and favors MCC specification, while hes5.10 is induced at higher Notch levels and required for SSCs, which are specified last. BC are promoted by Notch and partially by Hes5.10, but our results suggest additional Hes-independent routes of ΔN-tp63 regulation, which need further investigation. Our minimal-component in silico model recapitulates some of the most important features of the patterning process, such as the order of cell fate specification, temporal dependency, and changes in cell type compositions upon reduced Notch ligand expression. It the latter case, it produces results in line with our own and published data, e.g. the over-production of MCCs after Notch loss-of-function, that cannot be fully appreciated in our IF datasets, because not all MCCs can intercalate into the outer epithelium(Stubbs et al., 2006). Furthermore, the model predicts a new function of Spdef, which can be tested in future experiments.

In the mammalian lung, developmental time and location are coupled, with new cells emerging at the growing distal tips(Morimoto et al., 2010; Tsao et al., 2008). ISCs are rare and specified by higher Notch levels indicating that Foxi1 is not required for lung mucociliary development(Montoro et al., 2018). MCCs are specified first, emerge more distally than club cells, and produce Jag1/Jag2 ligands required for club cell specification(Morimoto et al., 2010; Rawlins et al., 2007), indicating a conservation of the general patterning mechanism. Airway BCs are not positively regulated by Notch during patterning, but sustained Notch inhibition prevents differentiation of MCCs and secretory cells in human ALI cultures, and leads to the thinning of the epithelium(Gomi et al., 2015; Rock et al., 2011), strongly suggesting a positive role for Notch in mammalian BCs maintenance as well. Similar to Xenopus, Hes5 is required for secretory cells, while Hes1 does not play a dominant role in mucociliary patterning in mammals(Tsao et al., 2009; Xing et al., 2012). Whether a similar competitive de-repression mechanism exists in airway mucociliary development remains unclear, but recent reports suggest a potentially similar function to Hes7.1 for Inhibitor of differentiation 2 (Id2) in the regulation of basal cells and differentiation(Kiyokawa et al., 2021).

Hence, we have uncovered a novel and potentially highly conserved self-organization mechanism regulating mucociliary cell type composition in vertebrates.

Methods:

Animal models and data availability

Xenopus laevis

Wild-type Xenopus laevis were obtained from the European Xenopus Resource Centre (EXRC) at University of Portsmouth, School of Biological Sciences, UK, or Xenopus 1, USA. Frog maintenance and care was conducted according to standard procedures in the AquaCore facility, University Freiburg, Medical Center (RI_00544) and based on recommendations provided by the international Xenopus community resource centers NXR (RRID:SCR_013731) and EXRC as well as by Xenbase (http://www.xenbase.org/, RRID:SCR_003280)(Nenni et al., 2019).

Ethics statements on animal experiments

This work was done in compliance with German animal protection laws and was approved under Registrier-Nr. G-18/76 by the state of Baden-Württemberg.

Material, data and code availability

NGS datasets are available via NCBI GEO (cf. RNA-sequencing on Xenopus mucociliary organoids and bioinformatics analysis). Imaging and quantification data are available to the scientific community upon request to peter.walentek@medizin.uni-freiburg.de. Mathematical modeling details and code are available to the scientific community upon request to ckreutz@imbi.uni-freiburg.de.

Xenopus experiments

Manipulation of Xenopus Embryos, Constructs and In Situ Hybridization

X. laevis eggs were collected and in vitro-fertilized, then cultured and microinjected by standard procedures (Sive et al., 2010). Embryos were injected with Morpholino oligonucleotides (MOs, Gene Tools), mRNAs or plasmid DNA at two-cell or four-cell stage using a PicoSpritzer setup in 1/3x Modified Frog Ringer’s solution (MR) with 2.5% Ficoll PM 400 (GE Healthcare, #17-0300-50), and were transferred after injection into 1/3x MR containing Gentamycin. Drop size was calibrated to about 7–8nL per injection.

Embryos injected with hormone-inducible constructs of (GFP-ΔN-tp63-GR(Haas et al., 2019) and MCI-GR(Stubbs et al., 2012)) were treated with 10μM Dexamethasone (Sigma-Aldrich/Merck #D4902) in ethanol from eight-cell stage until fixation. Ultrapure Ethanol (NeoFroxx #LC-8657.3) was used as vehicle control.

Morpholino oligonucleotides (MOs) were obtained from Gene Tools targeting dlc, dll1, foxa1, foxi1, hes2, hes4, hes5.10, hes7.1, jag1, jag2, notch1, notch2, notch3, and ΔN-tp63, and used at doses as indicated below.

Morpholino Sequences

| Name | Sequence | Concentration Range |

|---|---|---|

| foxi1MO | 5’-GTGCTTGTGGATCAAATGCACTCAT-3’ | 3 pmol |

| hes4.LMO | 5’-CAGGCATGTTCAGATGTTGTATCCG-3’ | 1–4 pmol |

| hes5.10.L/SMO | 5’-TGCAGATTGGGAGCCATTCTTTATG-3’ | 1–4 pmol |

| hes7.1.LMO | 5’-CTTCACTTGTTCCCTTCATGGTAAG-3’ | 1–4 pmol |

| notch1MO | 5’-GCACAGCCAGCCCTATCCGATCCAT-3’ | 1–4 pmol |

| notch2.L/sMO | 5’-CAAACACAGCCTGCACCCCCATC-3’ | 3 pmol |

| notch3.L/sMO | 5’-CCCATGATGCTCTCCTCCCCC-3’ | 3 pmol |

| dll1.LMO | 5’-CCCATGTTGTCTGATATGCGATTG-3’ | 1–4 pmol |

| dll1.sMO | 5’-AGGCACTGCTGTCCCATGTTG-3’ | 1–4 pmol |

| dlc.LMO | 5’-CAGTCTCCTGGCACTGACAAGGTG-3’ | 3 pmol |

| jag1.LMO | 5’-CTCTCCTTGGGAAACGCATTGCTTC-3’ | 4 pmol |

| jag2.L/sMO | 5’-TACTTATATCCAACATTGCTGGGAA-3’ | 4 pmol |

| foxa1MO | 5’-ATGGCAAGTGCCCGAGAGAATCATT-3’ | 3 pmol |

| tp63MO | 5’-GATACAACATCTTTGCAGTGAGGTT-3’ | 4 pmol |

| hes2.LMO | 5’-GCTCCCAATGTAGCGCTCGCAGACT-3’ | 5–8 pmol |

Full-length hes1, hes4, hes5.10, hes7.1 and hes2 constructs were cloned from total reverse-transcribed cDNA into pCS107 for overexpression and/or pGEM-T Easy (Promega #A137A) for anti-sense probes using primers listed below. All sequences were verified by Sanger sequencing and linearized with Apa1 (New England BioLabs #R0114S) to generate mRNAs (used at 25–150ng/μl). Anti-sense probe templates were either linearized with Sac2 (New England BioLabs #R0157S) and synthesized with SP6 RNA polymerase (Promega #P108G) or Sac1 (New England BioLabs #r3156S) and synthesized with T7 (Promega #P207E)

mRNA encoding membrane-GFP was used in some experiments as lineage tracers at 50ng/μL. All mRNAs were prepared using the Ambion mMessage Machine kit using Sp6 (#AM1340) supplemented with RNAse Inhibitor (Promega #N251B).

Notch reporter 4xcsl::H2B-mvenus plasmid(Nowotschin et al., 2013) was injected at 30ng/μl after purification using the PureYield Midiprep kit (Promega, #A2492). For antisense in situ hybridization probes, notch1, notch2, notch3, dlc, and jag2 fragments were cloned from whole-embryo cDNAs derived from stages between 3 and 30 using primers listed below (ISH-primers). All sequences were verified by Sanger sequencing. In addition, the following, previously published probes were used: foxi1(Quigley et al., 2011) , foxj1(Stubbs et al., 2008), mcidas(Stubbs et al., 2012), foxa1(Hayes et al., 2007) , tp63(Haas et al., 2019), dll1(Deblandre et al., 1999) and jag1(Tasca et al., 2021).

Cloning Primer Sequences

| Name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| ISH-notch1-F | CATTATCTCCCATCTGCTCC |

| ISH-notch1-R | CGTCTGGTTTATGTCGCTG |

| ISH-notch2-F | CAAATTCTCTTTCACCAGCAG |

| ISH-notch2-R | GTTTGAGATAACTGTCCATCGT |

| ISH-notch3-F | GCTTCTGGAGGAACACAACAC |

| ISH-notch3-R | GTAACATCATTGGGCACGCT |

| ISH-dlc-F | GAAGATTGATCGCTGTACC |

| ISH-dlc-R | AATTGGGACTTTCTGATTGG |

| BamH1-hes1-F | AAAGGATCCATGCCGGCTGATGTGATGGAG |

| hes1-Sal1-R | AAAGTCGACTTACCAGGGCCTCCAAACAG |

| BamH1-hes4-F | AAAGGATCCATGCCTGCAGATAGTATGGAG |

| hes4-Sal1-R | AAAGTCGACTCACCATGGTCGCCACACGG |

| BamH1-hes5.10-F | AAAGGATCCATGGCTCCAAATCTGCAGATG |

| hes5.10-Sal1-R | AAAGTCGACTTAAGGAGGAGAAAGAACCTG |

| BamH1-hes7.1-F | AAAGGATCCATGAAGGGAACAAGTGAAGTC |

| hes7.1-Sal1-R | AAAGTCGACTCATACCCAGGGTCTCCAGG |

| BamH1-hes2-F | AAAAGGATCCATGGCTCCCAATGTAGC |

| hes2-Sal1-R | AAAAGTCGACTCACCACGGCCTCCAG |

Whole mount in situ hybridization

Embryos were fixed in MEMFA (100mM MOPS pH7.4, 2mM EGTA, 1mM MgSO4, 3.7% (v/v) Formaldehyde) overnight at 4°C and stored in 100% Ethanol at −20°C until used. DNAs were purified using the PureYield Midiprep kit and were linearized before in vitro synthesis of anti-sense RNA probes using T7 or Sp6 polymerase (Promega, #P2077 and #P108G), RNAse inhibitor and dig-labeled rNTPs (Roche, #3359247910 and 11277057001). Embryos were in situ hybridized according to (Harland and Biology, 1991), bleached (Sive et al., 2000) after staining with BM Purple (Roche #11442074001) and imaged. Sections were made after embedding in gelatin-albumin with Glutaraldehyde at 70μm as described in (Walentek et al., 2012).

Stage series and morphological evaluations

Embryos were staged according to Nieuwkoop and Faber (1994) Normal Table of Xenopus laevis (Daudin). Garland Publishing Inc, New York ISBN 0-8153-1896-0. Onset of marker gene expression was quantified after in situ hybridization according to the number of stained dots visible in (prospective) epidermal cells. Marker expression was categorized into three groups (no expression; <20 dots; >20 dots). For embryos injected with foxi1MO, cell morphology and cell size were evaluated to determine that the embryos were dying. These embryos showed the features of aberrant cell morphology, increased cell size and cells/whole embryos that had completely turned white.

Preparation of mucociliary organoids (animal caps)

Injected and wildtype embryos were cultured until st. 8. Animal caps were dissected in 1x Modified Barth’s solution (MBS) and transferred to 0.5x MBS + Gentamycin(Sive et al., 2000). 10–15 organoids were collected in TRIzol (Thermo Fisher #15596026) per stage and used for qPCR or RNAsequencing.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using a standard Trizol (Invitrogen #15596026) protocol and used for cDNA synthesis with either iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad #1708891) or for the Notch reporter analysis with iScript gDNA Clear cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad #1725035). qPCR-reactions were conducted using Sso Advanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad #172-5275) on a CFX Connect Real-Time System (Bio-Rad) in 96-well PCR plates (Brand #781366). Experiments for Notch reporter analysis were conducted in biological triplicates and technical duplicates and normalized by ef1a and odc expression levels. Induction assays were performed in 7 biological replicates from 5 different clutches and each with two technical replicates. Expression levels were normalized by ef1α and odc expression and analyzed in Excel. Graphs were generated using R.

qPCR Primer Sequences

| Name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| qEf1a-F | CCCTGCTGGAAGCTCTTGAC |

| qEf1a-R | GGACACCAGTCTCCACACGA |

| qOdc-F | GGGCTGGATCGTATCGTAGA |

| qoOdc-R | TGCCAGTGTGGTCTTGACAT |

| qH2BVenus-F | CACCATCTTCTTCAAGGACGA |

| qH2BVenus-R | GGCTGTTGTAGTTGTACTCC |

| qFoxi1-F | TACCAAGAGATGAAGATGATC |

| qFoxi1-R | CTTGTCAGAAGATAACTGTCCA |

| qMci-F | AATCAAAAGCATCTGTC |

| qMci-R | TTTCTTAGAGATTTCCCGCA |

| qFoxa1-F | GGAGCAACTATTACCAGGAC |

| qFoxa1-R | ATGGGATTCATAGTCATGTAGG |

| qTP63DN-F2 | AAGCTCTACCTTTGATGCTC |

| qTP63DN-R2 | GATCTGTGGAATACGTCCAG |

| qFoxj1-F | CCAGTGATAGCAAAAGAGGT |

| qFoxj1-R | GCCATGTTCTCCTAATGGAT |

| qHes1-F | TGCGCTCAAGAAAGATAGCTC |

| qHes1-R | TTACTTCATTCATGCACTCGCT |

| qHes4-F | GATAAACCCAAGAGTGCCAG |

| qHes4-R | GTGCTTGACTGTCATTTCCA |

| qHes5.10-F | CTACAGCAACAGAAGAAACATCAG |

| qHes5.10-R | CCCACTGTCTCTTTCAAACAC |

| qHes7.1-F | GAAAGCTATTAAAGCCGTTGGTG |

| qHes7.1-R | GTGGGAGAAGTTTCCTGGAC |

| qDll1.L-F | TCACGAACTGAAGAATGAGGA |

| qDll1.L-R | TTGACGTTGAGTAGGCAGAG |

| qDlc.s-F | GGCACCTGTATCGAGAAGAG |

| qDlc.s-R | GACCCATATCTAGACACTGACC |

| qDll4.L-F | CATCTTTGGCTTGACGTTTCTC |

| qDll4.L-R | GACTTTCCATTCACCAACATCC |

| qJag1.L-F | CCAAACCCTGTGTAAATGCC |

| qJag1.L-R | GCGAAACCCATTAACCAAGTC |

| qJag2.L+s-F | GATATTTCTGTCACTGCCTTCC |

| qJag2.L-F | TCTTGCCAATGAAACCACGA |

| qJag2.s-R | GCTCTATCTCACAATGTTTCCCA |

Immunofluorescence Staining and Sample Preparation

Whole Xenopus embryos, were fixed at indicated stages in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C overnight or 2h at room temperature, then washed 3× 15min with PBS, 2× 30min in PBST (0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS), and were blocked in PBST-CAS (90% PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100, 10% CAS Blocking; ThermoFischer #00-8120) for 30min-1h at RT.

Mouse anti-Acetylated-α-tubulin (Sigma/Merck #T6793) was used as a primary antibody (1:1000) to mark cilia / MCCs applied at 4°C overnight, AlexaFlour 405-labeled goat anti-mouse antibody (Invitrogen # A30104) was used as a secondary antibody for 2 h at RT (1:250). Both antibodies were applied in 100% CAS Blocking (ThermoFischer #00-8120). Actin was stained by incubation (30–120 min at room temperature) with AlexaFluor 405-labeled Phalloidin (1:800 in PBSt; Invitrogen #A30104), mucus-like compounds were stained by incubation (overnight at 4°C) with AlexaFluor 647-labeled PNA (1:1000 in PBSt; Molecular Probes #L32460).

Confocal imaging, image processing and analysis

Confocal imaging was conducted using a Zeiss LSM880 and Zeiss Zen software. Confocal images were adjusted for channel brightness/contrast, Z-stack projections were generated and cell types were quantified based on their morphology using ImageJ(Schindelin et al., 2012). A detailed protocol for quantification of Xenopus epidermal cell types was published(Walentek, 2018) . Images of embryos after in situ hybridization and corresponding sections were imaged using an AxioZoom setup or AxioImager.Z1, and images were adjusted for color balance, brightness and contrast using Adobe Photoshop.

RNA-sequencing on Xenopus mucociliary organoids and bioinformatics analysis

X. laevis embryos were either injected 4x into the animal hemisphere at four-cell stage with mRNAs or MOs or remained uninjected, animal caps were prepared and used for RNA-sequencing at indicated stages. For RNA-seq dataset 1 (cf. Fig. S2A), uninjected organoids were collected at st. 9, st. 10.5 (labeled st. 10), st. 11.5 (labeled st. 11) and st. 12.5 (labeled st. 12) and organoids were derived from two independent experiments. For RNA-seq dataset 2 (cf. Fig. S2A), organoids were collected at st. 10.5 (labeled st. 10), st. 16 (st. 16) st. 25 (st. 25) and st. 32 (st. 32). Organoids were derived from 2 independent experiments. A previously published dataset (ΔN-tp63MO RNA-seq, GSE130448; cf. Fig. S2B) was used additionally(Haas et al., 2019).

500–1000 ng total RNA per sample was used, poly-A selection and RNA-sequencing library preparation was done using non strand massively-parallel cDNA sequencing (mRNA-Seq) protocol from Illumina, the TruSeq RNA Library Preparation Kit v2, Set A (Illumina #RS-122-2301) according to manufacturer’s recommendation. Quality and integrity of RNA was assessed with the Fragment Analyzer from Advanced Analytical by using the standard sensitivity RNA Analysis Kit (Advanced Analytical #DNF-471). For accurate quantitation of cDNA libraries, the QuantiFluor™dsDNA System from Promega was used. The size of final cDNA libraries was determined using the dsDNA 905 Reagent Kit (Advanced Bioanalytical #DNF-905) exhibiting a sizing of 300 bp on average. Libraries were pooled and paired-end 100bp sequencing on a HiSeq4000 was conducted at the Transcriptome and Genome Analysis Laboratory, University of Göttingen (RNA-seq dataset 1) or at the Functional Genomics Laboratory, University of California at Berkeley (RNA-seq dataset 2). Sequence images were transformed with Illumina software BaseCaller to BCL files, which was demultiplexed to fastq files with bcl2fastq v2.17.1.14. Quality control was done using FastQC v0.11.5 (Andrews, Simon (2010). “FastQC a quality-control tool for high-throughput sequence data” available at http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc).

After adapter-trimming, paired-end reads were mapped to Xenopus laevis genome assembly v9.2 using RNA STAR v2.6.0b-1(Dobin et al., 2013). featureCounts v1.6.3(Liao et al., 2014) was used to count uniquely mapped reads per gene and statistical analysis of differential gene expression was conducted in DEseq2 v1.22.1(Love et al., 2014). Heatmaps were generated in R v3.5.1 using ggplot2/heatmap2 v2.2.1. All bioinformatic analysis was performed on the Galaxy / Europe platform (usegalaxy.eu)(Community, 2022).

NGS data generated for this study was deposited at NCBI GEO under the accession numbers GSE215419 (RNA-seq dataset 1) and GSE215373 (RNA-seq dataset 2). Additionally, published data from Haas et al. (GSE130448) were used(Haas et al., 2019).

Gene expression plots over time of whole embryos for hes2.L and hes7.1L (cf. Fig. 4A) were generated using Xenbase (http://www.xenbase.org/, RRID:SCR_003280)(Fortriede et al., 2020; Session et al., 2016).

Quantification and statistical evaluation

Stacked bar graphs were generated in Microsoft Excel, box plots (the line represents the median; 50% of values are represented by the box; 95% of values are represented within whiskers; values beyond 95% are depicted as outliers) were generated in R. Heatmaps and Venn diagrams were generated using the Galaxy Europe platform (usegalaxy.eu)(Community, 2022). Sample sizes for all experiments were chosen based on previous experience and used embryos derived from at least two different females. No randomization or blinding was applied.

Use of shared controls

For some of the in situ experiments shared controls were used in multiple graphs.

Mathematical modeling

A Notch signaling ODE model for cell fate specification in mucociliary tissue

Our final ordinary differential equation (ODE) model (model 2) consists of 27 dynamical states, 38 reactions, 12 observables, 209 data points and 98 fitted parameters. In the following, it is explained what these quantities represent and how they are linked to each other in the model.

Dynamical states: Molecules and cells

The ODE model elucidates the influence of different molecular compounds on the cell type composition. This implies the model to act on two different scales: the molecular scale on the one hand, the cellular scale on the other. Therefore, unlike most ODE models in systems biology, the 27 dynamical states only partly represent the abundance of molecular compounds. Instead, 7 of them represent cell type abundances (Table S3 and S4).

Time evolution of the states

The rate equations, which govern the time evolution of system, can be divided into 3 categories:

Rate equations that represent cell state transitions (for simplicity, we still call them “reactions”): Initially, (nearly) all cells start as early progenitors (EPs). In a first step, these early progenitors are assumed to become multipotent progenitors (MPPs) at a constant rate (Reaction 1 in report), i.e. independent from any molecular abundances. This is different in the second step: MPPs themselves turn into ionocytes (ISCs), ciliated cells (MCCs), small secretory cells (SSCs) or basal cells (BCs) based on ΔN-tp63 repression and the effective levels of Hes4, Hes5, Hes7.1 and Spdef. The production rates of ISCs, MCCs, SSCs and BCs are given by hill equations, where each hill equation represents an activating or inhibiting effect from one of the mentioned transcription factors. The precise activations/inhibitions assumed in the model are depicted in the model flow chart (Fig. S9C). Most transcription factors act on a cell type either only activating or only inhibiting. The only exception is the effective Spdef level: It activates SSCs at lower levels but inhibits SSCs at higher levels. It was presumed that MPPs have to decide on a cell fate. This is ensured by a prior, that penalizes high MPP abundances compared to BC abundances at a late time point. For MCCs, two different dynamical states are introduced, because the related cell marker mcidas is only transiently expressed. The transition from the MCC marker expressing state to the later MCC state is assumed at a constant rate, i.e. independently of transcription factors represented in the model.

- Rate equations that represent production and degradation of molecules: All the dynamical states representing molecular abundances (cf. Table S4) have a production rate and a degradation rate. The degradation rates are assumed to be proportional to the abundances of all molecular states with individual rate constants. In contrast, the production rate depends on either the molecular abundances or on the cell type composition:

- For all the dynamical states representing RNA (cf. Table S4) except the acute Notch level, the production rates depend on other molecular abundances. The precise activation/inhibition connections between the transcription factors are depicted in the model flow chart (Fig. S9C). Hes4 is activated for low and inhibited for high effective Notch levels. This is reflected by a product of two hill equations at the according production rate. All others are given by a single hill equation. For all the dynamical states representing protein abundances (cf. Table S4), the production rates depend linearly or via a delay chain of length n=4 on the related RNA state.

- The production rate for the acute Notch level depends on the cell composition. It is defined as the weighted mean over the production rates of the individual cell types. The weights are given by the cell type proportions, i.e. the cell type composition. Initially, all the states from Table S4 are in steady state condition. These steady state conditions are calculated analytically. The starting point of modeling the whole specification process is the transition from EPs to MPPs and the resulting change in cell composition and acute Notch level production. All other transcription factors are direct or intermediate targets of the acute Notch level.

Embryonic stage representation in the model

The mapping between development stages and physical time in minutes was implemented according to Xenbase.org (http://www.xenbase.org/anatomy/static/xenopustimetemp.jsp). In particular, the values for Xenopus laevis, 22°C, average were used. Time point zero (physical time) was chosen to be at stage 9. Stages, where only one sample is present in the weblink table (i.e., where the columns “Average”, “Minimum” and “Maximum” coincide), were omitted. The value for the last considered stage, i.e. stage 25, is not present/taken in/from the table, but represents an interpolated value for stage 16 + 8 hours. Values for the physical time are obtained by linear interpolating the values from the columns A and B (Table S5).

Link to data

The parameters of the ODE model were fitted by two different types of data: time-resolved RNA-seq TPM data and cell counts from immunofluorescence (IF) images at a single later time of development (st. 32). The RNA-seq data observables (cf. Table S6) are linked to the dynamical ODE states via scaling parameters / proportionality factors (cf. Table S7), and in some cases offsets (mcidas, foxa1). The magnitude of the measurement errors for each observable were fitted by assuming constant error models on the logarithmic scale. The cell count observables for the three specified cell types (ISCs, MCCs, SSCs) coincide with the related dynamical ODE state, i.e. there are no additional parameters in the observation function. Here, measurement errors were taken from the estimated standard deviations over repeated measurements.

Software used

All modelling analyses were conducted using the Data2Dynamics modelling toolbox (https://github.com/Data2Dynamics/d2d)(Raue et al., 2015) which runs under Matlab, The MathWorks, Natick, MA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We thank: S. Schefold, M. Hansen, C. Softley for expert technical help; W. Driever, G. Pyrowolakis, C. Kintner for discussions and/or critical reading; Xenbase, EXRC for Xenopus resources; Light Imaging Center Freiburg and Aqua Core Facility for microscope/animal resources; B. Grüning and the Freiburg Galaxy Team for the bioinformatics platform and continuous support. This study was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) under the Emmy Noether Programme (grant WA3365/2-1) and by the NHLBI through a Pathway to Independence Award (K99HL127275) to PW; and under Germany’s Excellence Strategy (CIBSS – EXC-2189 – Project ID 390939984) to PW and CK.

References:

- Briggs J. A., Weinreb C., Wagner D. E., Megason S., Peshkin L., Kirschner M. W. and Klein A. M. (2018). The dynamics of gene expression in vertebrate embryogenesis at single-cell resolution. Science (80-. ). 360, eaar5780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha S. W., McAdams M., Kormish J., Wylie C. and Kofron M. (2012). Foxi2 is an animally localized maternal mRNA in xenopus, and an activator of the zygotic ectoderm activator foxi1e. PLoS One 7, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Community T. G. (2022). The Galaxy platform for accessible , reproducible and collaborative biomedical analyses : 2022 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, 345–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deblandre G. A., Wettstein D. A., Koyano-Nakagawa N. and Kintner C. (1999). A two-step mechanism generates the spacing pattern of the ciliated cells in the skin of Xenopus embryos. Development 126, 4715–4728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobin A., Davis C. A., Schlesinger F., Drenkow J., Zaleski C., Jha S., Batut P., Chaisson M. and Gingeras T. R. (2013). STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubaissi E., Rousseau K., Lea R., Soto X., Nardeosingh S., Schweickert A., Amaya E., Thornton D. J. and Papalopulu N. (2014). A secretory cell type develops alongside multiciliated cells, ionocytes and goblet cells, and provides a protective, anti-infective function in the frog embryonic mucociliary epidermis. Development 141, 1514–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortriede J. D., Pells T. J., Chu S., Chaturvedi P., Wang D., Fisher M. E., James-zorn C., Wang Y., Nenni M. J., Burns K. A., et al. (2020). Xenbase : deep integration of GEO & SRA RNA-seq and ChIP-seq data in a model organism database. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 776–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomi K., Arbelaez V., Crystal R. G. and Walters M. S. (2015). Activation of NOTCH1 or NOTCH3 Signaling Skews Human Airway Basal Cell Differentiation toward a Secretory Pathway. PLoS One 10, e0116507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guseh J. S., Bores S. A., Stanger B. Z., Zhou Q., Anderson W. J., Melton D. A. and Rajagopal J. (2009). Notch signaling promotes airway mucous metaplasia and inhibits alveolar development. Development 136, 1751–1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas M., Gómez Vázquez J. L., Sun D. I., Tran H. T., Brislinger M., Tasca A., Shomroni O., Vleminckx K. and Walentek P. (2019). ΔN-Tp63 Mediates Wnt/β-Catenin-Induced Inhibition of Differentiation in Basal Stem Cells of Mucociliary Epithelia. Cell Rep. 28, 3338–3352.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harland R. M. and Biology C. (1991). In situ hybridization: an improved whole-mount method for Xenopus embryos. Methods Cell Biol. 36, 685–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes J. M., Kim K. S., Abitua P. B., Park T. J., Herrington E. R., Kitayama A., Grow M. W., Ueno N. and Wallingford J. B. (2007). Identification of novel ciliogenesis factors using a new in vivo model for mucociliary epithelial development. Dev. Biol. 312, 115–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan B. L. M., Barkauskas C. E., Chapman H. A., Epstein J. A., Jain R., Hsia C. C. W., Niklason L., Calle E., Le A., Randell S. H., et al. (2014). Repair and Regeneration of the Respiratory System: Complexity, Plasticity, and Mechanisms of Lung Stem Cell Function. Cell Stem Cell 15, 123–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y. and Niehrs C. (2014). Polarized Wnt signaling regulates ectodermal cell fate in Xenopus. Dev. Cell 29, 250–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jukam D., Shariati S. A. M. and Skotheim J. M. (2017). Zygotic Genome Activation in Vertebrates. Dev. Cell 42, 316–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kageyama R., Ohtsuka T. and Kobayashi T. (2007). The Hes gene family: Repressors and oscillators that orchestrate embryogenesis. Development 134, 1243–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson M., Zhang C., Méar L., Zhong W., Digre A., Katona B., Sjöstedt E., Butler L., Odeberg J., Dusart P., et al. (2021). A single–cell type transcriptomics map of human tissues. Sci. Adv. 7, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpinka J. B., Fortriede J. D., Burns K. a, James-Zorn C., Ponferrada V. G., Lee J., Karimi K., Zorn A. M. and Vize P. D. (2014). Xenbase, the Xenopus model organism database; new virtualized system, data types and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 756–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyokawa H. and Morimoto M. (2020). Notch signaling in the mammalian respiratory system, specifically the trachea and lungs, in development, homeostasis, regeneration, and disease. Dev. Growth Differ. 62, 67–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyokawa H., Yamaoka A., Matsuoka C., Tokuhara T., Abe T. and Morimoto M. (2021). Airway basal stem cells reutilize the embryonic proliferation regulator, Tgfβ-Id2 axis, for tissue regeneration. Dev. Cell 56, 1917–1929.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y., Smyth G. K. and Shi W. (2014). featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30, 923–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love M. I., Huber W. and Anders S. (2014). Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mir A., Kofron M., Zorn A. M., Bajzer M., Haque M., Heasman J. and Wylie C. C. (2007). FoxI1e activates ectoderm formation and controls cell position in the Xenopus blastula. Development 134, 779–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoro D. T., Haber A. L., Biton M., Vinarsky V., Lin B., Birket S. E., Yuan F., Chen S., Leung H. M., Villoria J., et al. (2018). A revised airway epithelial hierarchy includes CFTR-expressing ionocytes. Nature 560, 319–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto M., Liu Z., Cheng H.-T., Winters N., Bader D. and Kopan R. (2010). Canonical Notch signaling in the developing lung is required for determination of arterial smooth muscle cells and selection of Clara versus ciliated cell fate. J. Cell Sci. 123, 213–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto M., Nishinakamura R., Saga Y. and Kopan R. (2012). Different assemblies of Notch receptors coordinate the distribution of the major bronchial Clara, ciliated and neuroendocrine cells. Development 139, 4365–4373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nenni M. J., Fisher M. E., James-Zorn C., Pells T. J., Ponferrada V., Chu S., Fortriede J. D., Burns K. A., Wang Y., Lotay V. S., et al. (2019). XenBase: Facilitating the use of Xenopus to model human disease. Front. Physiol. 10, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowotschin S., Xenopoulos P., Schrode N. and Hadjantonakis A. K. (2013). A bright single-cell resolution live imaging reporter of Notch signaling in the mouse. BMC Dev. Biol. 13, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou-Yang H. F., Wu C. G., Qu S. Y. and Li Z. K. (2013). Notch signaling downregulates MUC5AC expression in airway epithelial cells through hes1-dependent mechanisms. Respiration 86, 341–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley I. K. and Kintner C. (2017). Rfx2 Stabilizes Foxj1 Binding at Chromatin Loops to Enable Multiciliated Cell Gene Expression. PLoS Genet. 1–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley I. K., Stubbs J. L. and Kintner C. (2011). Specification of ion transport cells in the Xenopus larval skin. Development 138, 705–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raue A., Steiert B., Schelker M., Kreutz C., Maiwald T., Hass H., Vanlier J., Tönsing C., Adlung L., Engesser R., et al. (2015). Data2Dynamics: A modeling environment tailored to parameter estimation in dynamical systems. Bioinformatics 31, 3558–3560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlins E. L., Ostrowski L. E., Randell S. H. and Hogan B. L. M. (2007). Lung development and repair: Contribution of the ciliated lineage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104, 410–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock J. R., Gao X., Xue Y., Randell S. H., Kong Y. Y. and Hogan B. L. M. M. (2011). Notch-dependent differentiation of adult airway basal stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 8, 639–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin J., Arganda-Carreras I., Frise E., Kaynig V., Longair M., Pietzsch T., Preibisch S., Rueden C., Saalfeld S., Schmid B., et al. (2012). Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz K. N. and Harrison M. M. (2019). Mechanisms regulating zygotic genome activation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 20, 221–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Session A. M., Uno Y., Kwon T., Chapman J. A., Toyoda A., Takahashi S., Fukui A., Hikosaka A., Suzuki A., Kondo M., et al. (2016). Genome evolution in the allotetraploid frog Xenopus laevis. Nature 538, 336–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sive H. L., Grainger R. M. and Harland R. M. (2000). Early Development of Xenopus laevis. Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sive H. L., Grainger R. M. and Harland R. M. (2010). Microinjection of xenopus oocytes. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 5,. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skirkanich J., Luxardi G., Yang J., Kodjabachian L. and Klein P. S. (2011). An essential role for transcription before the MBT in Xenopus laevis. Dev. Biol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs J. L., Davidson L., Keller R. and Kintner C. (2006). Radial intercalation of ciliated cells during Xenopus skin development. Development 133, 2507–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs J. L., Oishi I., Izpisúa Belmonte J. C. and Kintner C. (2008). The forkhead protein Foxj1 specifies node-like cilia in Xenopus and zebrafish embryos. Nat. Genet. 40, 1454–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs J. L., Vladar E. K., Axelrod J. D. and Kintner C. (2012). Multicilin promotes centriole assembly and ciliogenesis during multiciliate cell differentiation. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada H., Hattori D., Kitayama A., Ueno N. and Taira M. (2005). Identification of target genes for the Xenopus Hes-related protein XHR1, a prepattern factor specifying the midbrain-hindbrain boundary. Dev. Biol. 283, 253–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasca A., Helmstädter M., Brislinger M. M., Haas M., Mitchell B. and Walentek P. (2021). Notch signaling induces either apoptosis or cell fate change in multiciliated cells during mucociliary tissue remodeling. Dev. Cell 56, 525–539.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao P. N., Chen F., Izvolsky K. I., Walker J., Kukuruzinska M. A., Lu J. and Cardoso W. V. (2008). γ-Secretase activation of notch signaling regulates the balance of proximal and distal fates in progenitor cells of the developing lung. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 29532–29544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao P.-N. N., Vasconcelos M., Izvolsky K. I., Qian J., Lu J. and Cardoso W. V. (2009). Notch signaling controls the balance of ciliated and secretory cell fates in developing airways. Development 136, 2297–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volckaert T. and De Langhe S. (2014). Lung epithelial stem cells and their niches: Fgf10 takes center stage. Fibrogenes. Tissue Repair 7, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walentek P. (2018). Manipulating and Analyzing Cell Type Composition of the Xenopus Mucociliary Epidermis. In Methods in Molecular Biology, pp. 251–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walentek P. (2021a). Signaling Control of Mucociliary Epithelia: Stem Cells, Cell Fates, and the Plasticity of Cell Identity in Development and Disease. Cells Tissues Organs. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walentek P. (2021b). Xenopus epidermal and endodermal epithelia as models for mucociliary epithelial evolution, disease, and metaplasia. Genesis 1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walentek P. and Quigley I. K. I. K. (2017). What we can learn from a tadpole about ciliopathies and airway diseases: Using systems biology in Xenopus to study cilia and mucociliary epithelia. Genesis 55, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walentek P., Beyer T., Thumberger T., Schweickert A. and Blum M. (2012). ATP4a is required for Wnt-dependent Foxj1 expression and leftward flow in Xenopus left-right development. Cell Rep. 1, 516–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walentek P., Bogusch S., Thumberger T., Vick P., Dubaissi E., Beyer T., Blum M. and Schweickert A. (2014). A novel serotonin-secreting cell type regulates ciliary motility in the mucociliary epidermis of Xenopus tadpoles. Dev. 141, 1526–1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitsett J. A. (2018). Airway epithelial differentiation and mucociliary clearance. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 15, S143–S148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing Y., Li A., Borok Z., Li C., Minoo P., Medicine C., Angeles L., Xing Y., Li A., Borok Z., et al. (2012). NOTCH1 Is Required for Regeneration of Clara Cells During Repair of Airway Injury. Stem Cells 30, 946–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J., Xu L., Crawford G., Wang Z. and Burgess S. M. (2006). The Forkhead Transcription Factor FoxI1 Remains Bound to Condensed Mitotic Chromosomes and Stably Remodels Chromatin Structure. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 155–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

NGS datasets are available via NCBI GEO (cf. RNA-sequencing on Xenopus mucociliary organoids and bioinformatics analysis). Imaging and quantification data are available to the scientific community upon request to peter.walentek@medizin.uni-freiburg.de. Mathematical modeling details and code are available to the scientific community upon request to ckreutz@imbi.uni-freiburg.de.