Abstract

Aspects of glutamate neurotransmission implicated in normal and pathological conditions are often evaluated using in vivo recording paradigms in rats anesthetized with isoflurane or urethane. Urethane and isoflurane anesthesia influence glutamate neurotransmission through different mechanisms; however real-time outcome measures of potassium chloride (KCl)-evoked glutamate overflow and glutamate clearance kinetics have not been compared within and between regions of the brain. In the following experiments, in vivo amperometric recordings of KCl-evoked glutamate overflow and glutamate clearance kinetics (uptake rate and T80) in the cortex, hippocampus and thalamus were performed using glutamate-selective microelectrode arrays (MEAs) in young adult male, Sprague-Dawley rats anesthetized with isoflurane or urethane. Potassium chloride (KCl)-evoked glutamate overflow was similar under urethane and isoflurane anesthesia in all brain regions studied. Analysis of glutamate clearance determined that the uptake rate was significantly faster (53.2%, p<0.05) within the thalamus under urethane compared to isoflurane, but no differences were measured in the cortex or hippocampus. Under urethane, glutamate clearance parameters were region dependent, with significantly faster glutamate clearance in the thalamus compared to the cortex but not the hippocampus (p<0.05). No region dependent differences were measured for glutamate overflow using isoflurane. These data support that amperometric recordings of glutamate under isoflurane and urethane anesthesia result in mostly similar and comparable data. However, certain parameters of glutamate uptake vary based on choice of anesthesia and brain region. Special considerations must be given to these areas when considering comparison to previous literature and when planning future experiments.

Keywords: isoflurane, urethane, glutamate neurotransmission, amperometry, cortex, hippocampus, thalamus

INTRODUCTION

Amperometric techniques have provided fundamental information regarding brain chemical communication of neurotransmitter systems in normal and disease-related physiologies. Glutamate is the primary excitatory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system (CNS) [1]. Experimental models of many CNS disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Huntington’s disease (HD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), epilepsy, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), post-concussive symptoms, and schizophrenia have indicated changes in glutamate neurotransmission as part of their pathophysiology. Mechanisms controlling glutamate neurotransmission provide novel targets for pharmacological intervention to restore physiological norms. Laboratory studies often use different anesthetics when evaluating functional alterations in neurocircuitry. These anesthetics can influence glutamate neurotransmission through interactions with various molecular targets making it challenging to determine if observed differences are due to pathophysiology or anesthetic used. Thus, meta-analysis and literature reviews that do not consider anesthetic choice may result in inaccurate interpretations given the lack of information on the influence that anesthesia has on certain outcome measures of glutamate kinetics.

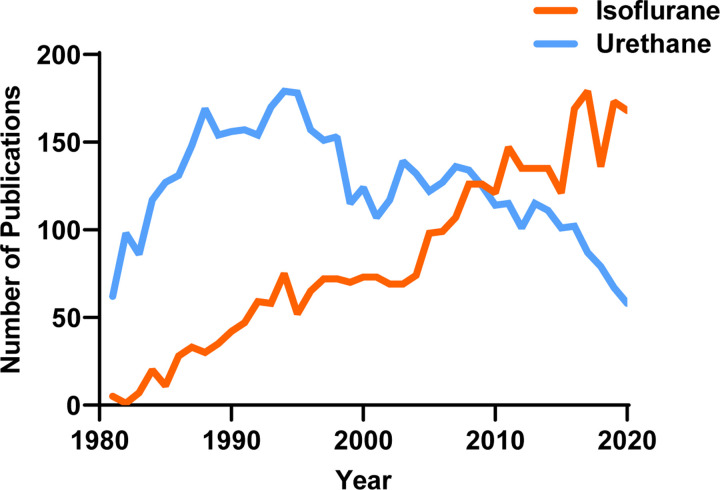

Despite the widespread use of various anesthetics, the fundamental question remains whether different anesthetics can influence neurochemical signaling and their mechanism of action. Urethane and isoflurane are commonly used anesthetics in translational neuroscience experiments, with ~8290 papers identified for urethane and isoflurane since 1981 (PubMed search for “urethane” AND “brain” or “isoflurane” AND “brain” from 1981 to 2020; Figure 1). In 1981, only five publications used isoflurane compared to 62 using urethane (7.5% isoflurane use). In 2020, 117 publications used isoflurane, and only 59 used urethane (66.5% isoflurane use). With this transition, it is important to consider whether specific outcome measures of experiments are influenced differentially between the two anesthetics so that researchers can build on previous bodies of knowledge. Furthermore, this knowledge would be a necessary consideration for experimental design and interpretation of future studies evaluating aspects of neuronal glutamatergic communication as we continue to apply them to understand neurochemical signaling under homeostatic and pathological conditions.

Figure 1. The number of publications using urethane and isoflurane for neuroscience research between 1981–2020.

A PubMed search indicates the use of urethane has decreased while the use of isoflurane has increased over the past 40 years.

KCl-evoked glutamate overflow and glutamate clearance kinetics are commonly used metrics of glutamatergic communication, measured by microdialysis or amperometry in anesthetized rats. Both urethane and isoflurane are known to suppress glutamate neurotransmission but work through dissimilar mechanisms that could differentially influence glutamate signaling. Urethane, also known as ethyl carbamate, produces long-lasting, steady levels of anesthesia with reports indicating minimal effects on circulation, respiration, autonomic function, reflex responses, and GABA neurotransmission [2–6]. Urethane also induces alternating cycles of EEG activity that resemble REM sleep and wakefulness, indicating that brain activity is preserved to a certain extent [7]. Recent complementary studies indicate that urethane anesthetized rats retained functional connectivity patterns most similar to awake animals during resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging in comparison to isoflurane [6]. While the mechanism of action is poorly understood, there is evidence that urethane primarily works through ion channels, distinct from isoflurane, influencing both inhibitory and excitatory systems [7]. These characteristics make urethane a popular anesthetic for electrophysiological experiments, but the actual influence on evoked glutamate release and clearance is unknown.

Given the benefits and ease of use with urethane, the reported carcinogenic properties of urethane primarily constrain urethane use to non-survival experiments [8, 9]. To use a more clinically relevant anesthetic, an increasing number of research papers using electrochemical and electrophysiological techniques have begun to use isoflurane. Isoflurane, a halogenated ether, has been implemented for its swift induction and recovery times and the precise control it allows over the amount of anesthesia delivered per unit time [10]. Mechanistically, evidence supports that isoflurane’s primary mechanism of action is mediated through the enhancement of GABAergic neurotransmission, thus inhibiting glutamate neurotransmission. In addition to different molecular mechanisms of action, urethane and isoflurane anesthesia have also been indicated to influence other brain regions to varying and opposing degrees. Paasonen et al. compared functional connectivity in several cortical and subcortical pathways under urethane and isoflurane protocols [5]. It was found that rats anesthetized with urethane retained similar connectivity in the cortical regions, but connectivity was suppressed in subcortical regions, including the hippocampus and thalamus. However, other studies comparing the influence of isoflurane and urethane on cortical networks in mice have shown the presence of stimulus-induced neuronal synchrony in both paradigms [11], highlighting a lack of congruency in previous reports where comparative studies are needed.

In this study, we sought to evaluate the relative comparability of KCl-evoked glutamate overflow and glutamate clearance kinetics collected via amperometric recordings from rats anesthetized by either isoflurane or urethane. Glutamate selective microelectrode arrays coupled with micropipettes filled with isotonic KCl solution or exogenous glutamate were placed within the cortex, hippocampus, or thalamus of naïve rats anesthetized with either isoflurane or urethane. The target regions were chosen because they are commonly implicated in cognition, somatosensation, and neuropathic pain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Young adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (3–4 month old; 359–438 g upon delivery) were purchased (Envigo, Indianapolis, IN) and pair housed in disposable cages (Innovive, San Diego, CA) under normal 12:12 h light:dark cycle in a temperature- and humidity-controlled vivarium. Rats were provided food (Teklad 2918, Envigo, Indianapolis, IN) and water ad libitum. Group size estimates were determined from previous work [12], where n = 6–10/group could predict >90% power to detect a significant change in outcome measures. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals care and were approved by the University of Arizona College of Medicine-Phoenix Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol #18–384).

Microelectrode Arrays

Ceramic-based MEAs encompassing four platinum recording surfaces (15 × 333 μm; S2 configuration) aligned in a dual, paired design were obtained from Quanteon LLC (Nicholasville, KY) for in vivo anesthetized recordings. MEAs were fabricated and selected for recordings using previously described measures of 0.125% glutaraldehyde and 1% GluOx [13–17]. MEAs were made glutamate selective as previously described [13, 18, 19]. Prior to in vivo recordings, a size exclusion layer of m-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (Acros Organics, NJ) was electroplated to all four platinum recording sites with the use of the FAST16 mkIII system (Fast Analytical Sensor Technology Mark III, Quanteon, LLC, Nicholasville, KY) to block potential interfering analytes such as ascorbic acid, catecholamines and other indoleamines [20]. The four platinum recording sites consisted of two glutamate-sensitive and two sentinel channels. The glutamate sensitive-channels were coated with 1% BSA, 0.125% glutaraldehyde and 1% glutamate oxidase.

Microelectrode Array Calibration

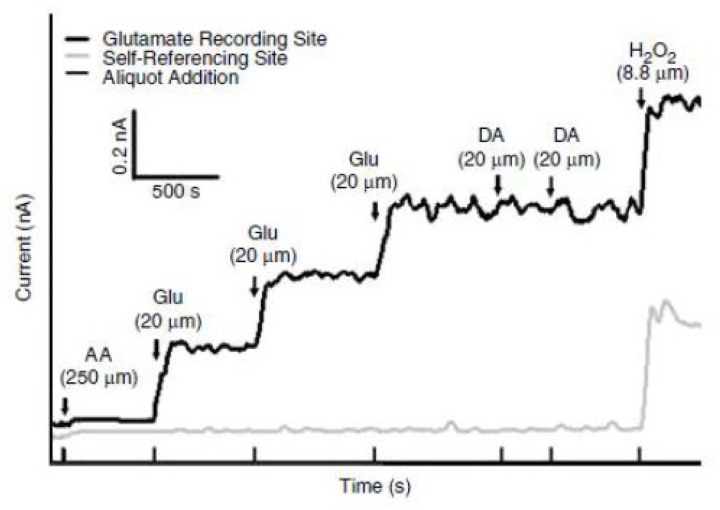

MEAs were calibrated with a FAST16 mkIII system to accurately record glutamate concentrations through the creation of a standard curve for each coated MEA within 24 hours of use in in vivo recordings, as described previously [18]. Briefly, the MEAs were submerged into 40 ml of stirred 0.05 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution kept in a water bath and allowed to reach a stable baseline before beginning the calibration. Aliquots from stock solutions were added in succession following equilibrium such that 500 μL of ascorbic acid, three additions of 40 μL of L-glutamate, two additions of 20 μL of dopamine, and 40 μL of H2O2 were added to produce final concentrations of 250 μM of ascorbic acid, 20, 40 and 60 μM of L-glutamate, 20 μM and 40 μM dopamine and 8.8 μM of H2O2 respectively in the beaker of PBS (pH 7.4). A representative calibration is depicted in Figure 2. From the MEA calibration, the following metrics were calculated and used for the determination of inclusion within the in vivo recordings: slope (sensitivity to glutamate), the limit of detection (LOD) (lowest amount of glutamate to be reliably recorded), and selectivity (ratio of glutamate to ascorbic acid). For the study, a total of 48 MEAs were used with 96 recording sites (Slopes: >5 pA/μM, LOD: <2.5 μM, and selectivity: >20:1). A representative MEA calibration is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Representative calibration of a glutamate selective microelectrode array (MEA).

Representative MEA calibration prior to in vivo recordings in which only one glutamate selective recording site and one self-referencing site are represented. Aliquots of 250 μM ascorbic acid (AA), 20 μM glutamate (Glu), 2 μM dopamine (DA), and 8.8 μM H2O2 are represented by vertical bars on the x-axis.

Microelectrode Array/Micropipette Assembly

Following calibration, a single-barrel glass micropipette was attached to the MEA with the following steps to allow for the local application of solutions during in vivo experiments. A single-barreled glass capillary with a filament (1.0 × 0.58 mm2, 6” A-M Systems, Inc., WA) was pulled to a tip using a Kopf Pipette Puller (David Kopf Instruments, CA). The pulled pipette was then bumped using a microscope and a glass rod to have an inner diameter averaging 11.1 μm ± 0.56. The pulled glass pipettes were embedded in modeling clay and attached to the circuit board above the MEA tip. Molten wax was applied to the embedded pipette to secure the MEA/micropipette assembly and prevent its movement during the recording. The pipette attachment was performed under a microscope to carefully place the tip of the pipette above the glutamate sensitive sites from the surface of the electrode. Measurements of pipette placement were confirmed using a microscope with a calibrated reticule in which the pipette was approximately 45 to 105 μm from the electrode sites (averaging 78.7 μm ± 4.9).

Reference Electrode Assembly

Silver/silver chloride reference electrodes were fabricated from Teflon-coated silver wire to provide an in vivo reference for the MEA. A 0.110-inch Teflon-coated silver wire (A-M Systems, Carlsborg, WA) was prepared by stripping approximately ¼” of Teflon coating from each end of a 6” section, soldering one end to a gold-plated socket (Ginder Scientific, Ottawa, ON) and the other being prepared to be coated with silver chloride. This end was placed into a 1 M HCl saturated with NaCl plating solution. A 9V current was applied to the silver wire (cathode) versus the platinum wire (anode) for approximately 5 minutes. Upon completion, the silver/silver chloride reference electrode was placed in a light-sensitive box until implanted.

Surgery

Rats were randomly assigned to receive either isoflurane or urethane until the pedal reflex was eliminated. Isoflurane was delivered via a nose cone (5% induction and 2% maintenance in oxygen) throughout the recordings. 25% urethane (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was administered as serial intraperitoneal injections (1.25–1.5 g/kg). Following the loss of the pedal response, each rat was then placed into a stereotaxic apparatus (David Kopf Instruments) with nonterminal ear bars. Body temperature was maintained at 37 °C with isothermal heating pads (Braintree Scientific, MA). A midline incision was made in which the skin, fascia, and temporal muscles were reflected, exposing the scalp. A bilateral craniectomy was then performed using a Dremel, exposing the stereotaxic coordinates for the somatosensory cortex, hippocampus, or thalamus. Dura was removed prior to the implantation of the MEA. Brain tissue was hydrated by applying saline-soaked cotton balls and gauze. Using blunt dissection, a silver/silver chloride-coated reference electrode wire was placed in a subcutaneous pocket on the dorsal side of the rat [21, 22]. All experiments were performed during the light phase of the 12 h-dark/light cycle.

In vivo Amperometric Recordings

Amperometric recordings performed here were similar to previously published methods [13, 23, 24]. Briefly, a constant voltage was applied to the MEA using the FAST16 mkIII recording system. In vivo recordings were performed at an applied potential of +0.7 V compared to the silver/silver chloride reference electrode wire. All data were recorded at a frequency of 10 Hz and amplified by the headstage piece (2 pA/mV). Immediately prior to implantation of the glutamate-selective MEA-pipette assembly, the pipette was filled with 120 mM of KCl (120 mM KCl, 29 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2, pH 7.2 to 7.5) or 100 μM L-glutamate (100 μM L-glutamate in 0.9% sterile saline pH 7.2–7.5) immediately prior to implantation and in vivo recording. The concentrations for both solutions have been previously shown to elicit reproducible potassium-evoked glutamate overflow or exogenous glutamate peaks [15, 25, 26]. Solutions were filtered through a 0.20 μm sterile syringe filter (Sarstedt AG & Co. Numbrecht, Germany) attached to a 1 mL syringe with a 4-inch, 30-gauge stainless steel needle with a beveled tip (Popper and Son, Inc, NY) while filling the micropipette. The open end of the micropipette end was then connected to a Picospritzer III (Parker-Hannin Corp., General Valve Corporation, OH) with settings to dispense fluid through the use of nitrogen gas in nanoliter quantities as measured by a dissecting microscope (Meiji Techno, San Jose, CA) with a calibrated reticule in the eyepiece [27, 28].

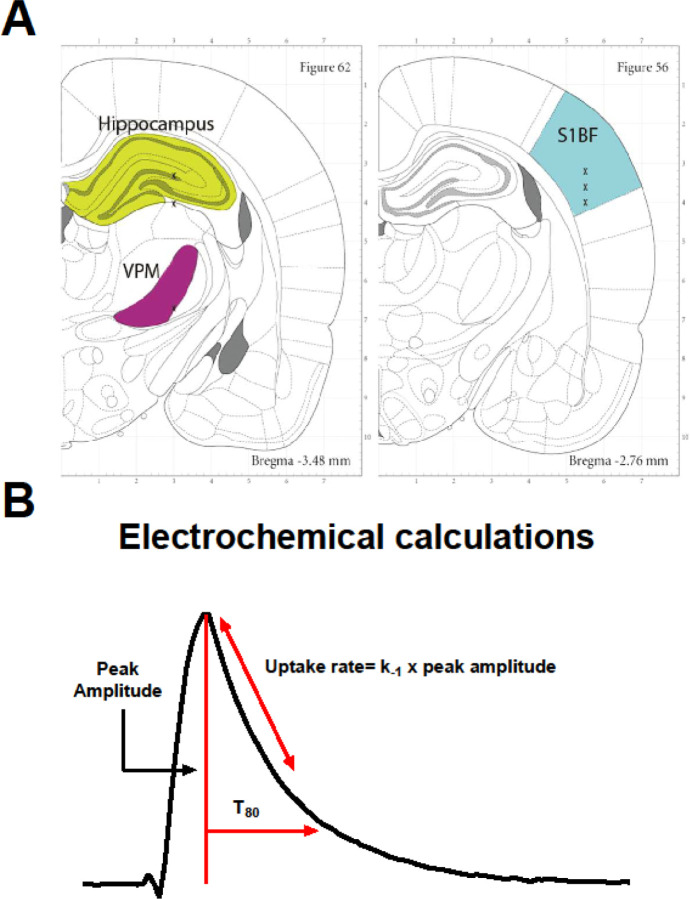

Once the MEA-micropipette apparatus was securely attached to the Picospritzer and FAST system, bregma was measured using an ultraprecise stereotaxic arm. MEA-micropipette constructs were implanted in the cortex (AP, −2.8 mm; ML, ±5.0 mm; DV, −1.0 mm vs. bregma), hippocampus (AP, −3.5 mm; ML, ±3.0 mm; DV, −2.6 to −3.75 mm vs. bregma) and thalamus (AP, −3.5 mm; ML, ±3.0 mm; DV, −5.6 mm vs. bregma) based on the coordinates from Paxinos and Watson [29] (Figure 3A). Glutamate and KCl-evoked measures were recorded in both hemispheres in a randomized and balanced experimental design to mitigate possible hemispheric variations or effects of anesthesia duration.

Figure 3. Recording regions and amperometric calculations.

(A) Anatomical regions of interest (ROI) in the rodent brain were the hippocampus (green), thalamus (purple), and cortex (blue). Image modified from Paxinos and Watson (2007). (B) Representative peak, showing glutamate concentration (μM) as a function of time in seconds. Amperometric calculations used in the analysis (peak amplitude, uptake rate, and T80) are shown.

KCl-Evoked Overflow of Glutamate Analysis Parameters

All recordings were conducted at 10 Hz and analyzed without signal processing or filtering the data. Once the glutamate MEA was lowered, and the electrochemical signal had reached stable baseline, pressure injections of a known volume of 120 mM potassium was locally applied to induce depolarization and subsequent overflow of glutamate from synapse was measured by the MEA. The volume of each application of KCl was predetermined to ensure maximal response (largest amount of glutamate released) which was confirmed by a smaller evoked peak following the 2-minute interval. The maximal amplitude of the glutamate response (μM) of the first peak was the primary outcome measure for analysis.

Glutamate Clearance Analysis Parameters

All recordings were conducted at 10 Hz and analyzed without signal processing or filtering of the data. Once the electrochemical signal had reached a baseline, 100 μM glutamate was locally applied into the extracellular space. Additions of exogenous glutamate were applied at 30-second intervals for reproducible glutamate peaks. Clearance parameters of 3 amplitude-matched peaks were averaged to create a single representative value per recorded region per rat. Primary outcome measures for analysis include the uptake rate and the time taken for 80% of the exogenous glutamate to clear the extracellular space (T80). The uptake rate is calculated by multiplying the uptake rate constant (k−1) by the peak’s maximum amplitude. Diagrammatic example of these calculations is shown in Figure 3B.

MEA Placement Verification

Immediately following in vivo anesthetized recordings, rats were transcardially perfused with PBS and post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Brains were cryoprotected, sectioned, and stained with a hematoxylin and eosin stain to confirm MEA electrode placement. No electrode tracts were excluded due to placement (data not shown).

Statistical Analysis

The amperometric data were saved on the FAST 16 mkIII system. Datasets were analyzed with FAST Analysis software (Jason Burmeister Consulting) and processed using a customized Microsoft Excel® spreadsheet. Inclusion criterion for data analysis of KCl-evoked response was maximum amount of glutamate overflow. Inclusion criterion for glutamate clearance kinetics was in the amplitude of 10 to 23 μM to control for Michaelis-Menten kinetics. All data are presented in the form of mean + standard error mean (mean ± SEM) and analyzed using the statistical software GraphPad Prism 9.4.1. Comparisons between anesthetics used a two-tailed Student’s t-test. Differences between regions were determined using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc comparison. All data sets were evaluated for variance (Brown-Forsythe) and normality (Kolmogorov-Smirnov) to ensure assumptions are met for analysis. Outliers were evaluated using a ROUT method with a false discovery rate of (Q) 1%. Differences were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Levels of evoked release of glutamate were similar in urethane and isoflurane-anesthetized rats.

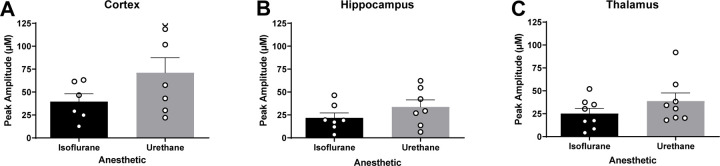

Surrounding neuronal tissue was depolarized with volume-matched (75–150 nL) applications of 120 mM isotonic KCl, and the maximum amplitude of glutamate was recorded. Cortical recordings revealed no significant differences in the amount of glutamate overflow between rats anesthetized with isoflurane or urethane (N = 6–7 rats; , ; t11 = 1.629; p = 0.131 μM; Figure 4A). Similarly, KCl-evoked glutamate overflow was independent of anesthetics in the hippocampus (N = 7 rats; , ; t12 = 1.247; p = 0.236; Figure 4B) or thalamus (N = 8 rats; , ; t14 = 1.299; p = 0.214; Figure 4C).

Figure 4. Levels of evoked release of glutamate were similar in urethane and isoflurane-anesthetized rats.

Local applications of volume-matched 120 mM potassium chloride (KCl) were made to the cortex, hippocampus, and thalamus. There was no significant difference between the glutamate overflow measured for rats anesthetized with isoflurane or urethane in the (A) cortex (t11 = 1.629, p = 0.131), (B) hippocampus (t12 = 1.247, p = 0.236), or (C) thalamus (t14 = 1.299, p=0.214). Bar graphs represent mean + SEM.

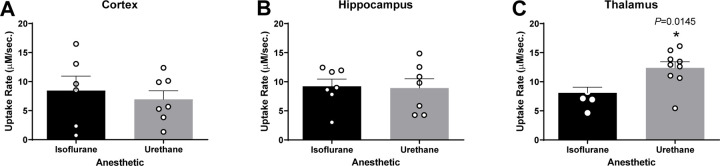

Glutamate uptake rate was faster in urethane anesthetized rats.

In each region of interest (ROI), glutamate clearance from the extracellular space was evaluated. Local applications of 100 μM exogenous glutamate were amplitude-matched at the time of administration. Cortical recordings revealed no significant differences in uptake rate between rats anesthetized with isoflurane or urethane (N = 6–7 rats; , ; t11 = 0.544; p = 0.597; Figure 5A). Uptake rate was also similar between anesthetics in the hippocampus (N = 7 rats; , ; t12 = 0.148; p = 0.884; Figure 5B). However, the thalamus of urethane anesthetized rats showed significantly faster uptake rate in comparison to isoflurane-anesthetized rats (N = 6–9 rats; , ; t13 = 2.817; p = 0.0145; Figure 5C). No differences were identified in the cortex (N = 5–7 rats; , ; t10 = 1.329; p = 0.213; Figure 6A), hippocampus (N = 5–7 rats; , ; t9 = 0.525; p = 0.612; Figure 6B), or thalamus (N = 6–9 rats; , ; t13 = 1.827; p = 0.090; Figure 6C).

Figure 5. Glutamate uptake rates were similar in the cortex and hippocampus and different in the thalamus of urethane and isoflurane-anesthetized rats.

Amplitude-matched signals from local applications of 100 μM exogenous glutamate compared for extracellular glutamate clearance in the cortex, hippocampus, and thalamus. No significant difference in the uptake rate between rats anesthetized with isoflurane or urethane in the (A) cortex (t11 = 0.544, p = 0.597) and (B) hippocampus (t12 = 0.148, p = 0.884). (C) Urethane administration was associated with a significantly faster uptake rate in thalamus than under isoflurane exposure (t13 = 2.817, p = 0.0145). Bar graphs represent mean + SEM.

Figure 6.

Extracellular clearance times (T80) were similar in urethane and isoflurane-anesthetized rats. Local application of 100 μM exogenous glutamate resulted in amplitude-matched signals to assess the T80 in the cortex, hippocampus, and thalamus. There was no significant difference in the time taken for 80% of the maximal amplitude to clear between rats anesthetized with isoflurane or urethane in the (A) cortex (t10 = 1.329, p = 0.213), (B) hippocampus (t9 = 0.525, p = 0.612), or (C) thalamus (t13 = 1.827, p = 0.090). Bar graphs represent mean + SEM.

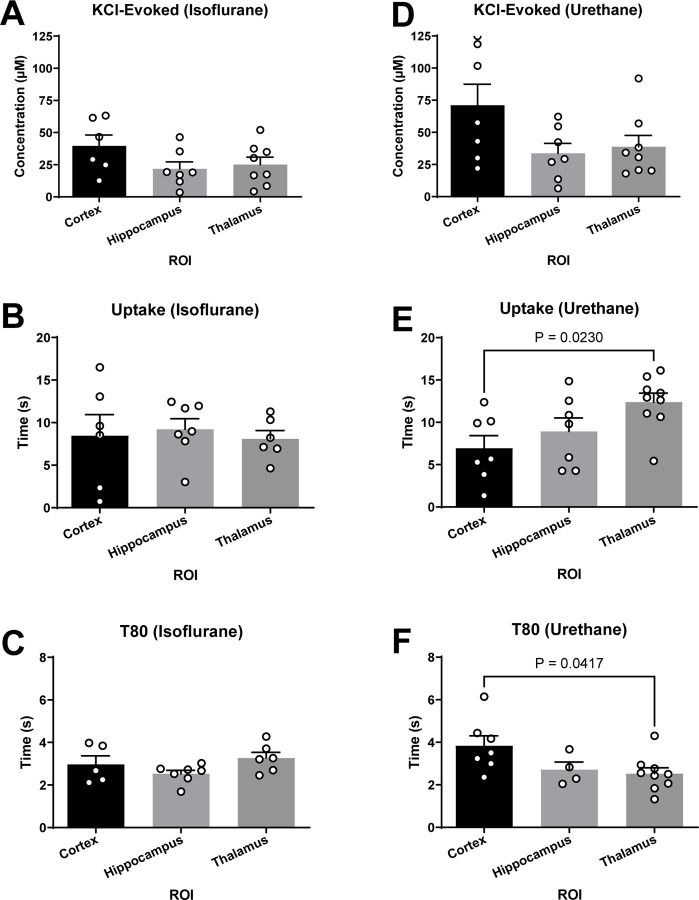

Urethane anesthesia influences brain region dependent differences of glutamate kinetics.

Aspects of glutamate neurotransmission were compared between brain regions under the influence of single anesthetic to determine region specific differences. No significant differences were detected between the cortex, hippocampus, and thalamus when using isoflurane for KCl-evoked glutamate overflow, uptake rate, and T80 (Figure 7A-C). Additionally, no differences were detected between regions for KCl-evoked overflow (Figure 7D) when using urethane anesthesia. Region dependent differences were detected in glutamate clearance with both the uptake rate (F2,20 = 4.41; p = 0.026; Figure 7E) and T80 (F2,14 = 3.79; p = 0.044; Figure 7F) being statistically significant between the thalamus and cortex recordings. Uptake rate in the thalamus was significantly faster than the cortex (p = 0.023), with no differences detected between the cortex or thalamus and the hippocampus (, ,). Faster uptake rate in the thalamus was supported by a shorter time to clear 80% of the glutamate signal in comparison to the cortex (p = 0.042). There were no differences detected between the T80 in the cortex or thalamus compared to the hippocampus (, , ).

Figure 7. Glutamate clearance under urethane was capable of distinguishing region-dependent differences.

(A-C) Under isoflurane, all outcome measures were similar between the cortex, hippocampus, and thalamus. (D) No significant differences were detected in KCl-evoked glutamate release across regions when using urethane. (E-F) Glutamate clearance kinetics under urethane changes as a function of the brain region when evaluating uptake rate (F2,20 = 4.41; p = 0.02) and T80 (F2,14 = 3.79; p = 0.04), where uptake rate was significantly faster and clearance time was significantly shorter in the thalamus compared to the cortex. Bar graphs represent mean + SEM.

DISCUSSION

These experiments were designed to test whether KCl-evoked glutamate overflow and glutamate clearance kinetics in the cortex, hippocampus, and thalamus were similar in rats anesthetized with either urethane or isoflurane. No differences in KCl-evoked glutamate overflow were identified by evaluating the maximal amplitude of glutamate released. The uptake rate and clearance time (T80) of locally applied exogenous glutamate were also similar under both anesthetics in the cortex and hippocampus, however, the uptake rate under urethane was significantly faster in the thalamus compared to isoflurane. Further, urethane treatment allowed the capability of measuring region-specific differences, where all regions were similar with isoflurane anesthetization. These data support the need for careful interpretation when comparing recordings from rodents under urethane or isoflurane anesthesia as certain parameters of glutamate uptake vary based on choice of anesthesia and brain region.

Local application of KCl causes a net positive of the resting membrane potential of surrounding neurons and glia, which results in subsequent action potentials that release stored neurotransmitters. The glutamate selective MEAs record sub-second changes in glutamate overflow into the extracellular space, such that the maximum amplitude can be statistically evaluated. Measured values are indicative of the amount of glutamate possible to be released during synaptic signaling. Alterations of values obtained from KCl-evoked glutamate overflow may result from changes to presynaptic neuron release, glutamate output from surrounding glia, decreased glutamate clearance, and the changes to glutamate transporters (GLT-1, GLAST, EAAC), GABAergic or modulatory neurotransmission, or alterations to mGluR regulation of glutamate release. [13, 23, 30–32].

Local application of exogenous glutamate enables the study of glutamate clearance kinetics in the extracellular space. The main contributors to the clearance of glutamate from the extracellular space in the cortex, hippocampus, and thalamus are astrocytic glutamate transporters EAAT1 (GLT-1; cerebral cortex: 90%; thalamus: 54%; data in comparison to the hippocampus) and EAAT2 (GLAST; cerebral cortex: 33%; hippocampus: 35%; thalamus: 22%; data in contrast to the cerebellum), and to a lesser extent, post-synaptic transporter EAAT3 [1, 33, 34]. Changes in glutamate clearance may indicate the function of glutamate transporters, transporter trafficking, transporter capacity, and transporter affinity [35]. Extracellular clearance parameters, including uptake rate, represent the velocity of the transporters, while T80 indicates the affinity of glutamate to the transporters [36]. Previous work has shown that alterations to the location (trafficking) or expression of GLT-1 and GLAST correlate to changes in glutamate clearance parameters as well [37, 38]. Conflicting literature evaluating the influence of isoflurane on glutamate uptake in in vitro models indicates enhancements in a dose-dependent manner [39–41], suppression/inhibition [42, 43], or no change [44]. Further, isoflurane use has been shown to increase the surface-level expression of EAAT3 [45]. While studies addressing the influence of urethane on glutamate transporters are lacking, the present data indicate that urethane interacts with the neurotransmitter system in the thalamus differently, such that regional dependent differences in glutamate clearance can be detected. Perhaps cellular, laminar, and regional heterogeneities of glutamate transporter distribution in the thalamus are contributing to this effect [46]. However, additional studies are needed to confirm whether this effect is due to the anesthetics having a differential influence on transporter function/expression or whether other distinct mechanisms of action culminate in minor region-dependent clearance kinetics.

The pharmacological mechanisms for anesthesia by urethane and isoflurane need to be better understood at the neurochemical level, making it difficult to predict the effect on aspects of neurotransmission [47]. Both urethane and isoflurane have been indicated to dampen overall glutamate neurotransmission, reported by evidence of less glutamate released, altered reuptake, reduced cellular excitability, decreased evoked glutamate overflow, and decreased tonic levels [2, 42, 48–53]. These effects may be mediated through the interaction between urethane and isoflurane with various GABAergic and glutamatergic receptors, as well as similar antagonistic effects at NMDA and AMPA receptors [54, 55]. Local field potential values were also similar under both anesthetics [47]. While each respective anesthetic’s molecular mechanism remains only partially understood, similarities amongst molecular targets and aspects of neuronal communication may contribute to comparable alterations in glutamate neurotransmission. Alternate sites of action of the anesthetics indicate a dose-dependent influence on factors that mediate glutamate neurotransmission [54, 56]. Isoflurane has been shown to bind to GABAa receptors [57], glutamate receptors, and glycine receptors, inhibit potassium channels [58, 59], and hyperpolarize neurons [60]. Hara et al. describes several unique molecular targets of urethane that influence glutamate neurotransmission, including enhancement of GABAa and glycine receptors, while various NMDA and AMPA subtypes are inhibited dose-dependently [54]. Furthermore, a 30% decrease in glutamate concentrations in the cerebral cortex of rats under urethane exposure is observed compared to un-anaesthetized rats [2]. It is indicated that urethane and isoflurane suppress presynaptic glutamate release associated with increased excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) in the hippocampus and thalamus, respectively [3, 61]. Further, it is shown that glutamate neurotransmission is reduced in cortical inhibitory interneurons with urethane exposure [62]. These reports indicate that other parameters, like basal extracellular levels, electrophysiological characteristics, and cell types not evaluated in these experiments, could be disrupted. Importantly, a recent study indicated that both isoflurane and urethane exposure had no significant impact on the neuronal response to whisker stimulation in mice [13, 18, 63, 64].

Valuable data may be obtained using neurochemical analysis under anesthesia. Whether accomplished through amperometry, microdialysis, or electrophysiology, a better understanding of neuronal communication helps identify pathological changes in glutamate neurotransmission within behaviorally relevant circuits [65]. Additionally, animal-specific factors (species, strain, age, and sex) influence glutamate neurotransmission, and the precise mechanism (or combination of mechanisms) that culminates in overall dampened glutamate neurotransmission remains theoretical and may confound biological relevance [13, 18, 37, 66–71]. Accordingly, our data indicate the use of either isoflurane or urethane results in similar, comparable effects on glutamatergic parameters in the cortex and hippocampus, despite being accomplished through dissimilar mechanisms. However, other functional outcomes of neuronal communication under these anesthetics have not been shown to result in a similar effect. Indeed, it is reported that anesthetic doses of isoflurane dampen sub-cortical activity inducing synchronous cortico-striatal fluctuations, while the use of urethane resulted in recordings most similar to awake rodents [5]. Neuronal activity measured utilizing BOLD fMRI reported that isoflurane and urethane dampens responses when compared to unanesthetized subjects but does not comment on which anesthetic is more comparable to the awake state [72–74]. Studies investigating changes in molecular components that are known to interact with a given anesthetic must use caution when interpreting results and attributing changes to a specific mechanism. These and other studies indicate that not all neuronal circuits respond identically under anesthesia. Thus, investigating anesthesia’s effect on other neuromodulators (5-HT, GABA, DA, ACh) and their functional outputs in specific circuits should be considered when interpreting comparisons across several studies. It is even recommended that studies evaluating physiologic parameters controlled by the CNS should use caution when measuring their output while under anesthesia since CNS-mediated physiologic functions may not result in comparable changes under isoflurane or urethane despite PCO2, O2, pH, and heart rate having been shown to be similarly affected [5]. Therefore, experiments should be carried out in preparation for moving into awake-behaving models, where simultaneous recordings of behavior and glutamate signaling are possible. In doing so, we can discover aberrant glutamate signaling and determine the efficacy of therapeutic approaches relevant to treat several brain disorders marked by maladaptive behaviors.

The safety and efficacy of anesthetic on animals has historically influenced researchers’ choice when considering study design. Urethane is classified by the International Agency for Research on Cancer as a group 2A carcinogen and thus considered “probably carcinogenic to humans.” This designation has limited urethane use primarily to non-survival studies despite its ease of use and favorable profile. In doing so, using urethane as a sole anesthetic in longitudinal studies with multiple data collection time points in the same animals is not considered humane for the risk of tumor formation. However, the inclusion of urethane as part of an anesthetic cocktail provides researchers with significant advantages. In mice, it was found that using 560 mg/kg alongside ketamine and xylazine was not carcinogenic [75]. Ultimately this cocktail was advantageous as the use of low doses of all three anesthetics limited confounding changes in electrical potentials observed when a ketamine/xylazine combination is used alone [75–77]. Of note, these studies provide evidence that the combination of multiple anesthetics leads to the capitalization of favorable effects.

Conclusions

In conclusion, these data support the hypothesis that isoflurane and urethane similarly influence KCl-evoked glutamate overflow and glutamate clearance parameters. Electrochemical recordings from outcome measures under urethane or isoflurane anesthesia with a similar protocol, inclusion, and exclusion criterion can be integrated into interpretations with careful regard to other potential influencing factors, especially region of interest. Finally, future studies evaluating glutamate neurotransmission should focus on the beneficial aspects of anesthetic when optimizing the experimental design as well as the inclusion of the female sex to evaluate any sex-specific sensitivity.

Highlights.

KCl-evoked glutamate overflow was similar under urethane and isoflurane anesthesia

Glutamate clearance parameters were similar under both anesthesias in the cortex and hippocampus but not the thalamus

Glutamate clearance kinetics differ between brain regions when anesthetized with urethane.

Experimental design, brain region of interest, and outcome parameters of glutamate clearance should be considered when designing anesthetized amperometry recordings of glutamate.

Acknowledgments

We thank Carol Haussler for critical review of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grant (R01NS100793), Valley Research Partnership (P1201607), Phoenix Children’s Hospital-Leadership Circle Grant, PCH Mission Support Funds, Midwestern University ORSP, and Midwestern Biomedical Sciences Department funds

List of abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- ADHD

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

- CNS

central nervous system

- HD

Huntington’s disease

- KCl

potassium chloride

- LOD

limit of detection

- MEAs

microelectrode arrays

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- PFA

paraformaldehyde

- ROI

region of interest

Footnotes

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Availability of data and materials

All data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Danbolt NC. Glutamate uptake. ProgNeurobiol. 2001;65 1:1–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moroni F, Corradetti R, Casamenti F, Moneti G, Pepeu G. The release of endogenous GABA and glutamate from the cerebral cortex in the rat. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1981;316 3:235–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tian Y, Lei T, Yang Z, Zhang T. Urethane suppresses hippocampal CA1 neuron excitability via changes in presynaptic glutamate release and in potassium channel activity. Brain Res Bull. 2012;87 4–5:420–6; doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maggi CA, Meli A. Suitability of urethane anesthesia for physiopharmacological investigations in various systems. Part 1: General considerations. Experientia. 1986;42 2:109–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paasonen J, Stenroos P, Salo RA, Kiviniemi V, Gröhn O. Functional connectivity under six anesthesia protocols and the awake condition in rat brain. Neuroimage. 2018;172:9–20; doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soma LR. Anesthetic and analgesic considerations in the experimental animal. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1983;406:32–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pagliardini S, Funk GD, Dickson CT. Breathing and brain state: urethane anesthesia as a model for natural sleep. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2013;188 3:324–32; doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2013.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okamura M, Unami A, Matsumoto M, Oishi Y, Kashida Y, Mitsumori K. Gene expression analysis of urethane-induced lung tumors in ras H2 mice. Toxicology. 2006;217 2–3:129–38; doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2005.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Field KJ, Lang CM. Hazards of urethane (ethyl carbamate): a review of the literature. Lab Anim. 1988;22 3:255–62; doi: 10.1258/002367788780746331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henry RT, Casto R. Simple and inexpensive delivery of halogenated inhalation anesthetics to rodents. Am J Physiol. 1989;257 3 Pt 2:R668–71; doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1989.257.3.R668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lissek T, Obenhaus HA, Ditzel DA, Nagai T, Miyawaki A, Sprengel R, et al. General Anesthetic Conditions Induce Network Synchrony and Disrupt Sensory Processing in the Cortex. Frontiers in cellular neuroscience. 2016;10:64; doi: 10.3389/fncel.2016.00064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas TC, Ogle SB, Rumney BM, May HG, Adelson PD, Lifshitz J. Does time heal all wounds? Experimental diffuse traumatic brain injury results in persisting histopathology in the thalamus. Behavioural brain research. 2018;340:137–46; doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas TC, Hinzman JM, Gerhardt GA, Lifshitz J. Hypersensitive glutamate signaling correlates with the development of late-onset behavioral morbidity in diffuse brain-injured circuitry. Journal of neurotrauma. 2012;29 2:187–200; doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burmeister J, Gerhardt G. Neurochemical arrays. Encyclopedia of sensors. 2006;6:525. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burmeister JJ, Pomerleau F, Day BK, Huettl P, Gerhardt GA. Improved ceramic-based multisite microelectrode for rapid measurements of L-glutamate in the CNS. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2002;119:163–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burmeister JJ, Gerhardt GA. Ceramic-Based Multisite Microelectrodes for Electrochemical Recordings. Analytical Chemistry. 2000;72 1:187–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burmeister JJ, Gerhardt GA. Self-Referencing Ceramic-Based Multisite Microelectrodes for the Detection and Elimination of Interferences from the Measurement of L-Glutamate and Other Analytes. Analytical Chemistry. 2001;73 5:1037–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krishna G, Bromberg C, Connell EC, Mian E, Hu C, Lifshitz J, et al. Traumatic Brain Injury-Induced Sex-Dependent Changes in Late-Onset Sensory Hypersensitivity and Glutamate Neurotransmission. Front Neurol. 2020;11:749; doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beitchman JA, Griffiths DR, Hur Y, Ogle SB, Bromberg CE, Morrison HW, et al. Experimental Traumatic Brain Injury Induces Chronic Glutamatergic Dysfunction in Amygdala Circuitry Known to Regulate Anxiety-Like Behavior. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:1434; doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.01434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burmeister JJ, Pomerleau F, Palmer M, Day BK, Huettl P, Gerhardt GA. Improved ceramic-based multisite microelectrode for rapid measurements of L-glutamate in the CNS. J Neurosci Methods. 2002;119 2:163–71; doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(02)00172-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moussy F, Harrison DJ. Prevention of the rapid degradation of subcutaneously implanted Ag/AgCl reference electrodes using polymer coatings. AnalChem. 1994;66 5:674–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quintero JE, Day BK, Zhang Z, Grondin R, Stephens ML, Huettl P, et al. Amperometric measures of age-related changes in glutamate regulation in the cortex of rhesus monkeys. ExpNeurol. 2007;208 2:238–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hinzman JM, Thomas TC, Burmeister JJ, Quintero JE, Huettl P, Pomerleau F, et al. Diffuse brain injury elevates tonic glutamate levels and potassium-evoked glutamate release in discrete brain regions at two days post-injury: an enzyme-based microelectrode array study. JNeurotrauma. 2010;27 5:889–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas TC, Lisembee A, Gerhardt GA, Lifshitz J. Glutamate Neurotransmission Recorded on A Sub-Second Timescale in A Diffuse Brain-Injured Circuit Reveals Injury-Induced Deficits That Parallel the Development of Behavioral Morbidity in Rats. J Neurotrauma. 2009;26 8:284. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stephens ML, Pomerleau F, Huettl P, Gerhardt GA, Zhang Z. Real-time glutamate measurements in the putamen of awake rhesus monkeys using an enzyme-based human microelectrode array prototype. J Neurosci Methods. 2010;185 2:264–72; doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Day BK, Pomerleau F, Burmeister JJ, Huettl P, Gerhardt GA. Microelectrode array studies of basal and potassium-evoked release of L-glutamate in the anesthetized rat brain. J Neurochem. 2006;96 6:1626–35; doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cass WA, Gerhardt GA, Mayfield RD, Curella P, Zahniser NR. Differences in dopamine clearance and diffusion in rat striatum and nucleus accumbens following systemic cocaine administration. JNeurochem. 1992;59 1:259–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Friedemann MN, Gerhardt GA. Regional effects of aging on dopaminergic function in the Fischer-344 rat. NeurobiolAging. 1992;13 2:325–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain In Stereotaxic Coordinates. Academic Press, New York; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Santhakumar V, Voipio J, Kaila K, Soltesz I. Post-traumatic hyperexcitability is not caused by impaired buffering of extracellular potassium. JNeurosci. 2003;23 13:5865–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jacob TC, Moss SJ, Jurd R. GABA(A) receptor trafficking and its role in the dynamic modulation of neuronal inhibition. Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2008;9 5:331–43; doi: 10.1038/nrn2370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watt AJ, van Rossum MC, MacLeod KM, Nelson SB, Turrigiano GG. Activity coregulates quantal AMPA and NMDA currents at neocortical synapses. Neuron. 2000;26 3:659–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petr GT, Sun Y, Frederick NM, Zhou Y, Dhamne SC, Hameed MQ, et al. Conditional deletion of the glutamate transporter GLT-1 reveals that astrocytic GLT-1 protects against fatal epilepsy while neuronal GLT-1 contributes significantly to glutamate uptake into synaptosomes. J Neurosci. 2015;35 13:5187–201; doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4255-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meldrum BS. Glutamate as a neurotransmitter in the brain: review of physiology and pathology. J Nutr. 2000;130 4S Suppl:1007S–15S; doi: 10.1093/jn/130.4.1007S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maragakis NJ, Rothstein JD. Glutamate transporters: animal models to neurologic disease. NeurobiolDis. 2004;15 3:461–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomas TC, Beitchman JA, Pomerleau F, Noel T, Jungsuwadee P, Butterfield DA, et al. Acute treatment with doxorubicin affects glutamate neurotransmission in the mouse frontal cortex and hippocampus. Brain Res. 2017;1672:10–7; doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2017.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nickell J, Salvatore MF, Pomerleau F, Apparsundaram S, Gerhardt GA. Reduced plasma membrane surface expression of GLAST mediates decreased glutamate regulation in the aged striatum. NeurobiolAging. 2007;28 11:1737–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hinzman JM, Thomas TC, Quintero JE, Gerhardt GA, Lifshitz J. Disruptions in the regulation of extracellular glutamate by neurons and glia in the rat striatum two days after diffuse brain injury. Journal of neurotrauma. 2012;29 6:1197–208; doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zuo Z. Isoflurane enhances glutamate uptake via glutamate transporters in rat glial cells. Neuroreport. 2001;12 5:1077–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Larsen M, Hegstad E, Berg-Johnsen J, Langmoen IA. Isoflurane increases the uptake of glutamate in synaptosomes from rat cerebral cortex. Br J Anaesth. 1997;78 1:55–9; doi: 10.1093/bja/78.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miyazaki H, Nakamura Y, Arai T, Kataoka K. Increase of glutamate uptake in astrocytes: a possible mechanism of action of volatile anesthetics. Anesthesiology. 1997;86 6:1359–66; discussion 8A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liachenko S, Tang P, Somogyi GT, Xu Y. Concentration-dependent isoflurane effects on depolarization-evoked glutamate and GABA outflows from mouse brain slices. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;127 1:131–8; doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Westphalen RI, Hemmings HC Jr. Effects of isoflurane and propofol on glutamate and GABA transporters in isolated cortical nerve terminals. Anesthesiology. 2003;98 2:364–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nicol B, Rowbotham DJ, Lambert DG. Glutamate uptake is not a major target site for anaesthetic agents. Br J Anaesth. 1995;75 1:61–5; doi: 10.1093/bja/75.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang Y, Zuo Z. Isoflurane induces a protein kinase C alpha-dependent increase in cell-surface protein level and activity of glutamate transporter type 3. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67 5:1522–33; doi: 10.1124/mol.104.007443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Torp R, Hoover F, Danbolt NC, Storm-Mathisen J, Ottersen OP. Differential distribution of the glutamate transporters GLT1 and rEAAC1 in rat cerebral cortex and thalamus: an in situ hybridization analysis. Anat Embryol (Berl). 1997;195 4:317–26; doi: 10.1007/s004290050051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pearce RA, Stringer JL, Lothman EW. Effect of volatile anesthetics on synaptic transmission in the rat hippocampus. Anesthesiology. 1989;71 4:591–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Larsen M, Langmoen IA. The effect of volatile anaesthetics on synaptic release and uptake of glutamate. Toxicol Lett. 1998;100–101:59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Larsen M, Valo ET, Berg-Johnsen J, Langmoen IA. Isoflurane reduces synaptic glutamate release without changing cytosolic free calcium in isolated nerve terminals. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 1998;15 2:224–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Larsen M, Haugstad TS, Berg-Johnsen J, Langmoen IA. The effect of isoflurane on brain amino acid release and tissue content induced by energy deprivation. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 1998;10 3:166–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Holmes GL, Ben-Ari Y. A single episode of neonatal seizures permanently alters glutamatergic synapses. Ann Neurol. 2007;61 5:379–81; doi: 10.1002/ana.21136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Westphalen RI, Desai KM, Hemmings HC Jr. Presynaptic inhibition of the release of multiple major central nervous system neurotransmitter types by the inhaled anaesthetic isoflurane. Br J Anaesth. 2013;110 4:592–9; doi: 10.1093/bja/aes448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zimin PI, Woods CB, Kayser EB, Ramirez JM, Morgan PG, Sedensky MM. Isoflurane disrupts excitatory neurotransmitter dynamics via inhibition of mitochondrial complex I. Br J Anaesth. 2018;120 5:1019–32; doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2018.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hara K, Harris RA. The anesthetic mechanism of urethane: the effects on neurotransmitter-gated ion channels. AnesthAnalg. 2002;94 2:313–8, table. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bickler PE, Warner DS, Stratmann G, Schuyler JA. gamma-Aminobutyric acid-A receptors contribute to isoflurane neuroprotection in organotypic hippocampal cultures. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2003;97 2:564–71, table of contents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Masamoto K, Fukuda M, Vazquez A, Kim SG. Dose-dependent effect of isoflurane on neurovascular coupling in rat cerebral cortex. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30 2:242–50; doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06812.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Garcia PS, Kolesky SE, Jenkins A. General anesthetic actions on GABA(A) receptors. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2010;8 1:2–9; doi: 10.2174/157015910790909502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu R, Ueda M, Okazaki N, Ishibe Y. Role of potassium channels in isoflurane- and sevoflurane-induced attenuation of hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction in isolated perfused rabbit lungs. Anesthesiology. 2001;95 4:939–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu X, Li R, Yang Z, Hudetz AG, Li SJ. Differential effect of isoflurane, medetomidine, and urethane on BOLD responses to acute levo-tetrahydropalmatine in the rat. Magn Reson Med. 2012;68 2:552–9; doi: 10.1002/mrm.23243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ries CR, Puil E. Mechanism of anesthesia revealed by shunting actions of isoflurane on thalamocortical neurons. Journal of neurophysiology. 1999;81 4:1795–801; doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.4.1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Woodward TJ, Timic Stamenic T, Todorovic SM. Neonatal general anesthesia causes lasting alterations in excitatory and inhibitory synaptic transmission in the ventrobasal thalamus of adolescent female rats. Neurobiol Dis. 2019;127:472–81; doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2019.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Guo J, Ran M, Gao Z, Zhang X, Wang D, Li H, et al. Cell-type-specific imaging of neurotransmission reveals a disrupted excitatory-inhibitory cortical network in isoflurane anaesthesia. EBioMedicine. 2021;65:103272; doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thrane AS, Rangroo Thrane V, Zeppenfeld D, Lou N, Xu Q, Nagelhus EA, et al. General anesthesia selectively disrupts astrocyte calcium signaling in the awake mouse cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109 46:18974–9; doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209448109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Krishna G, Bromberg CE, Thomas TC. Chapter 23 - Circuit reorganization after diffuse axonal injury: Utility of the whisker barrel circuit. In: Rajendram R, Preedy VR, Martin CR, editors. Cellular, Molecular, Physiological, and Behavioral Aspects of Traumatic Brain Injury. Academic Press; 2022. p. 281–92. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Krishna G, Beitchman JA, Bromberg CE, Currier Thomas T. Approaches to Monitor Circuit Disruption after Traumatic Brain Injury: Frontiers in Preclinical Research. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21 2; doi: 10.3390/ijms21020588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Luckl J, Keating J, Greenberg JH. Alpha-chloralose is a suitable anesthetic for chronic focal cerebral ischemia studies in the rat: a comparative study. Brain Res. 2008;1191:157–67; doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rutherford EC, Pomerleau F, Huettl P, Stromberg I, Gerhardt GA. Chronic second-by-second measures of L-glutamate in the central nervous system of freely moving rats. JNeurochem. 2007;102 3:712–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stephens ML, Quintero JE, Pomerleau F, Huettl P, Gerhardt GA. Age-related changes in glutamate release in the CA3 and dentate gyrus of the rat hippocampus. NeurobiolAging. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.Thomas TC, Grandy DK, Gerhardt GA, Glaser PE. Decreased dopamine D4 receptor expression increases extracellular glutamate and alters its regulation in mouse striatum. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34 2:436–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Beitchman JA, Griffiths DR, Hur Y, Ogle SB, Hair CE, Morrison HW, et al. Diffuse TBI-induced expression of anxiety-like behavior coincides with altered glutamatergic function, TrkB protein levels and region-dependent pathophysiology in amygdala circuitry. bioRxiv. 2019:640078; doi: 10.1101/640078. [DOI]

- 71.Kim T, Masamoto K, Fukuda M, Vazquez A, Kim SG. Frequency-dependent neural activity, CBF, and BOLD fMRI to somatosensory stimuli in isoflurane-anesthetized rats. NeuroImage. 2010;52 1:224–33; doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.03.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Martin C, Martindale J, Berwick J, Mayhew J. Investigating neural-hemodynamic coupling and the hemodynamic response function in the awake rat. Neuroimage. 2006;32 1:33–48; doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhao F, Jin T, Wang P, Kim SG. Isoflurane anesthesia effect in functional imaging studies. Neuroimage. 2007;38 1:3–4; doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhao F, Jin T, Wang P, Kim SG. Improved spatial localization of post-stimulus BOLD undershoot relative to positive BOLD. Neuroimage. 2007;34 3:1084–92; doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rex TS, Boyd K, Apple T, Bricker-Anthony C, Vail K, Wallace J. Effects of Repeated Anesthesia Containing Urethane on Tumor Formation and Health Scores in Male C57BL/6J Mice. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci. 2016;55 3:295–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jehle T, Ehlken D, Wingert K, Feuerstein TJ, Bach M, Lagrèze WA. Influence of narcotics on luminance and frequency modulated visual evoked potentials in rats. Doc Ophthalmol. 2009;118 3:217–24; doi: 10.1007/s10633-008-9160-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bricker-Anthony C, Hines-Beard J, D’Surney L, Rex TS. Exacerbation of blast-induced ocular trauma by an immune response. J Neuroinflammation. 2014;11 1:192; doi: 10.1186/s12974-014-0192-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]