Abstract

Clinical trials showed that upadacitinib, a selective Janus kinase-1 inhibitor, is effective for treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. However, daily practice studies are limited. This multicentre prospective study evaluated the effectiveness of 16 weeks of upadacitinib treatment for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in adult patients, including those with previous inadequate response to dupilumab and/or baricitinib, in daily practice. A total of 47 patients from the Dutch BioDay registry treated with upadacitinib were included. Patients were evaluated at baseline, and after 4, 8 and 16 weeks of treatment. Effectiveness was assessed by clinician- and patient-reported outcome measurements. Safety was assessed by adverse events and laboratory assessments. Overall, the probabilities (95% confidence intervals) of achieving Eczema Area and Severity Index ≤ 7 and Numerical Rating Scale – pruritus ≤ 4 were 73.0% (53.7–86.3) and 69.4% (48.7–84.4), respectively. The effectiveness of upadacitinib was comparable in patients with inadequate response to dupilumab and/or baricitinib and in patients who were naïve for these treatments or who had stopped such treatments due to adverse events. Fourteen (29.8%) patients discontinued upadacitinib due to ineffectiveness, adverse events or both (8.5%, 14.9% and 6.4%, respectively). Most frequently reported adverse events were acneiform eruptions (n = 10, 21.3%), herpes simplex (n = 6, 12.8%), nausea and airway infections (both n = 4, 8.5%). In conclusion, upadacitinib is an effective treatment for patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis, including those with previous inadequate response to dupilumab and/or baricitinib treatment.

Key words: atopic dermatitis, daily practice, Janus kinase inhibitor, patient-reported outcome measure, upadacitinib

SIGNIFICANCE

Only a few daily practice studies have been published on the effectiveness and safety of upadacitinib treatment in patients with atopic dermatitis. The current study, of 47 adult patients treated with upadacitinib for 16 weeks in a real-life setting, showed that upadacitinib is an effective treatment option for patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis, including those with previous inadequate response to dupilumab and/or baricitinib treatment. Although most adverse events were considered to be mild, 7/47 (14.9%) patients permanently discontinued upadacitinib treatment due to at least 1 adverse event.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common chronic inflammatory skin disease with a complex pathophysiology and an unmet need for adequate treatment options, especially in patients with moderate-to-severe AD (1, 2). An improvement in the treatment for AD occurred with the advent of dupilumab in 2017, the first registered biologic for the treatment of moderate-to-severe AD (3–5). In the Netherlands baricitinib was the second new advanced systemic treatment, and therefore the first commercially available Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor (3, 6). However, there is still a need for additional treatment options in case of side effects or treatment failure (7).

Recently, several other advanced systemic therapies have become commercially available for the treatment of AD. One of them is upadacitinib, a selective JAK-1 inhibitor (2, 8). Although the pathophysiology of AD is primarily T-helper 2 (Th2)-driven, several other inflammatory pathways are involved, providing multiple therapeutic targets that may vary in different patients.

These Th1-, Th2-, Th17- and Th22- pathways mediate their effect by using JAK-1 to induce signalling of many pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g. interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5, IL-13, IL-17, IL-22, IL-31 and IFN-γ), leading to epidermal thickening, skin barrier dysfunction and itch. By blocking JAK-1, the cytokine signalling pathways are downregulated, leading to a decrease in AD severity and itch, and consequent improvement in quality of life (QoL) and daily functioning (7, 9). So far, clinical trials have shown the effectiveness of upadacitinib in moderate-to-severe AD and even demonstrated a superior response to upadacitinib compared with dupilumab treatment in patients with AD (10–12). However, daily practice data are limited (13–16).

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of 16 weeks of treatment with upadacitinib in adult patients with moderate-to-severe AD, including those with previous inadequate response to dupilumab and/or baricitinib in daily practice. A secondary aim was to evaluate the short-term safety profile of upadacitinib.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population and treatment

This prospective multicentre observational cohort study included patients with moderate-to-severe AD (≥ 18 years) who were participating in the Dutch BioDay registry (a Dutch registry that contains daily practice data on effectiveness and safety of new advanced systemic therapies for the treatment of atopic dermatitis). Patients were treated with upadacitinib 15 mg (in case of a standard dosage or patients aged ≥ 65 years) or 30 mg (in case of severe AD based on physician’s decision) once daily (QD) between October 2021 until May 2022. Patients visited the outpatient clinic at the start of upadacitinib treatment (baseline), and after 4, 8 and 16 weeks of treatment. Patients were recorded as using other immunosuppressive treatment at baseline if washout criteria were not fulfilled (washout < 1 week for cyclosporine A, JAK-inhibitors and prednisolone, < 4 weeks for methotrexate, and < 10 weeks for biologics). Background therapy with topical corticosteroids was allowed. The study was approved by the local medical research ethics committee (Utrecht, the Netherlands, number 18-239) as a non-interventional study, and was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent.

Clinical outcome measures

Effectiveness was assessed at every visit by the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) (17) and the Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) (18). In addition, patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) were collected and included the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) (19) of the average weekly pruritus, the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) (20), the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) (21), and the Patient Global Assessment of Disease Status (PGADS) (Table SI) (22). The Atopic Dermatitis Control Tool (ADCT) (23) was assessed at baseline and after 16 weeks of treatment. Primary endpoints were the mean EASI, NRS-pruritus, DLQI and POEM at weeks 4, 8 and 16. Secondary endpoints were evaluated by absolute cut-off scores EASI≤7 (24), IGA≤1 (18), NRS-pruritus≤4 (24), DLQI≤5 (23), ADCT<7 (23) and PGADS≥3 (22) at weeks 4, 8 and 16.

Dupilumab and baricitinib responder analysis

Effectiveness outcomes were stratified by dupilumab and baricitinib non-responders (dup-NR, bari-NR) (i.e. discontinuation of treatment due to ineffectiveness or a combination of ineffectiveness/adverse events (AEs)) vs dupilumab and baricitinib responders/naïve patients (dup-R/naïve, bari-R/naïve) (i.e. discontinuation due to AEs/other reasons and patients with no previous dupilumab/baricitinib treatment). This stratification was performed to evaluate whether the effectiveness of upadacitinib was different for dupilumab and/or baricitinib non-responders, suggesting that these patients might have a more difficult-to-treat AD.

Safety

AEs were evaluated and laboratory assessments (blood count, liver enzymes, serum creatinine, creatinine phosphokinase (CPK)) were performed at every visit. Lipid status was monitored at baseline and week 16. AEs and laboratory abnormalities were ranked based on frequency and severity. Severity of the AEs was based on the guideline of Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) and expert opinion. AEs that led to treatment discontinuation were reported as severe.

Statistical analysis

At first, the overall percentage of missing values for clinical scores and PROMs was calculated (33.4%). To avoid bias and loss of statistical power, multiple imputation (MI) was performed (25, 26). MI was performed with linear regression for continuous variables. Age, sex, concomitant use of immunosuppressive treatment and number/reason of dropouts (i.e. patients who discontinued upadacitinib treatment before or at week 16) were used as predictors. Outcomes of patients after discontinuation, although included in the imputation, were excluded from the analysis to avoid bias. The data was imputed 34 times and all analyses were performed on each imputation separately. Subsequently, the results were pooled with Rubin’s rule (27).

For continuous outcomes, a linear regression model was used, in which a residual covariance (i.e. GEE-type) matrix was included to correct for multiple measurements per patient over time. The effect of follow-up time and interaction of the time with dupilumab and baricitinib (non-)responders was tested with likelihood ratio tests. For dichotomous outcomes, a logistic regression with a random intercept was used. Secondly, the interaction of time with dupilumab or baricitinib (non-)responders was included. Outcomes were used to estimate means (for continuous outcomes) and probabilities (for dichotomous outcomes) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). The model did not converge for the IGA ≤ 1 due to no patients achieving this outcome at baseline, therefore the baseline IGA ≤ 1 was excluded from analysis.

Differences in baseline characteristics between dupilumab and baricitinib (non-)responders were analysed by a t-test for normally distributed and continuous outcomes. For dichotomous/categorical outcomes a χ2 test was used. Statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (version 27.0) (Armonk, NY, USA.) and SAS v9.4. Miceadds package in Rstudio (Boston, MA, USA) was used to pool the likelihood ratio tests (27, 28). p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Figures were constructed with Graphpad Prism (version 8.3) (Boston, MA, U.S.A).

RESULTS

Patient and baseline characteristics

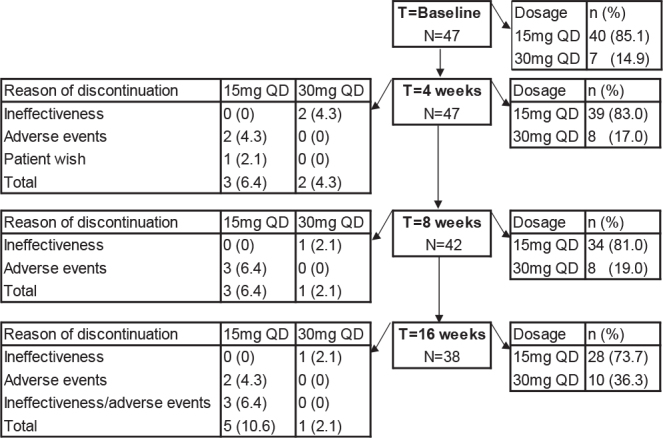

A total of 47 adult patients with AD treated with upadacitinib in academic (n = 43) and non-academic hospitals (n = 4) were included. The patients’ median age was 33.0 years (interquartile range (IQR) 26.0–43.0 years) and most patients were male (n = 31, 66.0%). Only 1 patient was diagnosed with hypertension; none of the patients had a medical history of deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, stroke or any other underlying cardiovascular disease. Forty-three (91.5%) and 15 (29.4%) patients had been previously exposed to dupilumab or baricitinib, respectively. Of these, 23 (48.9%) and 14 (29.8%) patients were defined as dupilumab and baricitinib inadequate/non-responders (dup-NR and bari-NR, respectively). Twenty-four (51.1%) and 33 (70.2%) patients were defined as dupilumab and baricitinib responder/naïve patients (dup-R/naïve and bari-R/naïve, respectively) (Table I). Moreover, almost all patients (n = 14/15) who were previously treated with baricitinib discontinued dupilumab treatment due to ineffectiveness/AEs, of which 7 (14.9%) patients had inadequate response to both dupilumab and baricitinib treatment. Only 1 patient was also previously treated with tralokinumab and 3 patients received abrocitinib in clinical trial setting prior to upadacitinib treatment. In total, 32 patients (68.1%) were using (or in the washout of) concomitant systemic immunosuppressive/immunomodulating treatment for their AD or comorbidity (polymyalgia rheumatic (PMR), n = 1; tertiary adrenal insufficiency, n = 1) at baseline. In 7 (14.9%) patients the initial dose of upadacitinib was 30 mg once daily, all other patients (85.1%) started with 15 mg once daily (Fig. 1 and Table SII). Baseline characteristics and a flowchart of patients are shown in Table I and Fig. 1.

Table I.

Baseline and patient characteristics

| Total cohort (n = 47) | Dup-R/naïve(n = 24) | Dup-NR(n = 23) | p - valuea | Bari-R/naïve(n = 33) | Bari-NR(n = 14) | p - valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 31 (66.0) | 13 (54.2) | 18 (78.3) | 0.081 | 21 (63.6) | 10 (71.4) | 0.606 |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 33.0 (26.0–43.0) | 37.0 (29.0–49.0) | 30.0 (25.0–42.0) | 0.337 | 37.0 (24.5–46.0) | 32.5 (29.8–42.8) | 0.681 |

| Age of onset ADc, n (%) | 0.548 | 0.008 | |||||

| Childhood | 41 (87.2) | 21 (87.5) | 20 (87.0) | 32 (97.0) | 9 (64.3) | ||

| Adolescence | 5 (10.6) | 3 (12.5) | 2 (8.7) | 1 (3.0) | 4 (28.6) | ||

| Adult | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (7.1) | ||

| Atopic disease at baseline, n (%) | 41 (87.2) | 23 (95.8) | 18 (78.3) | 0.071 | 28 (84.8) | 13 (92.9) | 0.452 |

| Allergic asthma | 28 (59.6) | 17 (70.8) | 11 (47.8) | 0.108 | 20 (60.6) | 8 (57.1) | 0.825 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 33 (70.2) | 20 (83.3) | 13 (56.5) | 0.045 | 22 (66.7) | 11 (78.6) | 0.414 |

| Allergic conjunctivitis | 32 (68.1) | 19 (79.2) | 13 (56.5) | 0.197 | 21 (63.6) | 11 (78.6) | 0.545 |

| Missing | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.3) | 1 (3.0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Food allergy | 19 (40.4) | 10 (41.7) | 9 (39.1) | 0.335 | 14 (42.4) | 5 (35.7) | 0.774 |

| Missing | 2 (4.3) | 0 (0) | 2 (8.7) | 1 (3.0) | 1 (7.1) | ||

| ≥ 2 atopic comorbidities | 33 (70.2) | 21 (87.5) | 12 (52.2) | 0.008 | 24 (72.7) | 9 (64.3) | 0.563 |

| History of conventional immunosuppressive drugs, n (%) | 47 (100) | ||||||

| Cyclosporine A | 43 (91.5) | 23 (95.8) | 20 (87.0) | 0.276 | 31 (93.9) | 12 (85.7) | 0.827 |

| Methotrexate | 20 (42.6) | 9 (37.5) | 11 (47.8) | 0.474 | 13 (39.4) | 7 (50.0) | 0.501 |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 11 (23.4) | 5 (20.8) | 6 (26.1) | 0.671 | 8 (24.2) | 3 (21.4) | 0.835 |

| Oral tacrolimus | 3 (6.4) | 1 (4.2) | 2 (8.7) | 0.525 | 3 (9.1) | 0 (0) | 0.244 |

| Azathioprine | 2 (4.3) | 1 (4.2) | 1 (4.3) | 0.975 | 1 (3.0) | 1 (7.1) | 0.523 |

| History of ≥ 2 immunosuppressive drugs | 26 (55.3) | 13 (54.2) | 13 (56.5) | 0.871 | 19 (57.6) | 7 (50.0) | 0.870 |

| History of biological, n (%) | |||||||

| Dupilumab | 44 (93.6) | 21 (87.5) | 23 (100) | NA | 33 (100) | 11 (78.6) | 0.890 |

| Tralokinumab | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (43.5) | 0.302 | 1 (3.0) | 0 (0) | 0.510 |

| Reason of discontinuation dupilumab, n (%) | NA | NA | |||||

| Ineffectiveness | 13 (29.5) | 0 (0) | 13 (56.5) | 12 (36.4) | 1 (7.1) | ||

| Adverse events | 20 (45.5) | 20 (95.2) | 0 (0) | 14 (42.4) | 6 (42.9) | ||

| Ineffectiveness/AEs | 10 (22.7) | 0 (0) | 10 (43.5) | 6 (18.2) | 4 (28.6) | ||

| Patient wish* | 1 (2.3) | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Reason of discontinuation tralokinumab, n (%) | |||||||

| Ineffectiveness | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | NA | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | NA |

| History of JAK-inhibitor, n (%) | |||||||

| Baricitinib | 15 (29.4) | 7 (29.2) | 8 (34.8) | 0.680 | 1 (3.0) | 14 (100) | NA |

| Abrocitinib | 3 (6.4) | 2 (8.3) | 1 (4.3) | 0.576 | 1 (3.0) | 2 (14.3) | 0.149 |

| Reason of discontinuation baricitinib, n (%) | NA | NA | |||||

| Ineffectiveness | 13 (86.7) | 6 (85.7) | 7 (87.5) | 0 (0) | 13 (92.9) | ||

| Adverse events | 1 (6.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | ||

| Ineffectiveness/AEs | 1 (6.7) | 1 (14.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (7.1) | 0.083 | |

| Reason of discontinuation abrocitinib, n (%) | 0.386 | ||||||

| Ineffectiveness | 1 (33.3) | 1 (50.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | ||

| Patient wish | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 1 (50.0) | ||

| Pregnancy wish | 1 (33.3) | 1 (50.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (50.0) | ||

| Immunosuppressive therapy at | 0.401 | 0.083 | |||||

| baseline, n (%) | 32 (68.1) | 15 (62.5) | 17 (73.9) | 25 (75.8) | 7 (50.0) | ||

| Cyclosporine A | 1 (2.1) | 1 (4.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Methotrexate | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (7.1) | ||

| Prednisolone | 3 (6.4) | 3 (12.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (6.1) | 1 (7.1) | ||

| Hydrocortisone | 1 (2.1) | 1 (4.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Dupilumab | 22 (46.8) | 9 (37.5) | 13 (56.5) | 21 (63.6) | 1 (7.1) | ||

| Tralokinumab | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.3) | 1 (3.0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Baricitinib | 5 (10.6) | 2 (8.3) | 3 (13.0) | 0 (0) | 5 (35.7) | ||

| EASI score, mean (SD) | 16.6 (10.4) | 15.8 (12.0) | 17.3 (8.5) | 0.630 | 16.4 (11.1) | 17.0 (7.0) | 0.869 |

| IGA score, n (%) | 0.111 | 0.546 | |||||

| Clear | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Almost clear | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Mild | 9 (19.1) | 6 (25.0) | 3 (13.0) | 8 (24.2) | 1 (7.1) | ||

| Moderate | 21 (44.7) | 13 (54.2) | 8 (34.8) | 14 (42.4) | 7 (50.0) | ||

| Severe | 15 (31.9) | 4 (16.7) | 11 (47.8) | 9 (27.3) | 6 (42.9) | ||

| Very severe | 2 (4.3) | 1 (4.2) | 1 (4.3) | 2 (6.1) | 0 (0) | ||

| NRS-pruritus, mean (SD) | 7.0 (2.1) | 7.0 (1.8) | 6.9 (2.4) | 0.924 | 6.9 (2.2) | 7.1 (1.9) | 0.773 |

| DLQI score, mean (SD) | 11.3 (5.5) | 11.0 (5.4) | 11.5 (5.5) | 0.784 | 11.6 (5.7) | 10.4 (4.6) | 0.500 |

| POEM score, mean (SD) | 19.9 (5.3) | 20.3 (5.2) | 19.5 (5.4) | 0.597 | 19.6 (5.5) | 20.8 (5.1) | 0.509 |

| ADCT score, mean (SD) | 12.5 (5.0) | 12.5 (4.4) | 12.5 (5.6) | 0.970 | 12.3 (5.1) | 12.9 (4.8) | 0.667 |

| PGADS, n (%) | 0.459 | 0.320 | |||||

| Poor | 12 (25.5) | 6 (25.0) | 6 (26.1) | 9 (27.3) | 3 (21.4) | ||

| Fair | 19 (40.4) | 9 (37.5) | 10 (43.5) | 14 (42.4) | 5 (35.7) | ||

| Good | 10 (21.3) | 7 (29.2) | 3 (13.0) | 6 (18.2) | 4 (38.6) | ||

| Very good | 6 (12.8) | 2 (8.3) | 4 (17.4) | 4 (12.1) | 2 (14.3) | ||

| Excellent | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

p-value calculated for differences between dupilumab non-responder(NR) vs. dupilumab responder(R)/naïve patients(naïve),

and baricitinib-NR vs. baricitinib-R/naïve.

Reference categories: childhood aged < 12 years, adolescence aged 12-17 years, adult ≥18 years.

Standard deviation (SD) was calculated by the standard error of the mean (SEM) multiplied by √n. AD: Atopic Dermatitis; EASI: Eczema Area and Severity Index; IGA: Investigator Global Assessment; NRS: Numeric Rating Scale; DLQI: Dermatology Life Quality Index; POEM: Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure; ADCT: Atopic Dermatitis Control Tool; PGADS: Patient Global Assessment of Disease Status; JAK: Janus Kinase; IQR: Interquartile Range. NA: Not Applicable.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of 47 patients during the first 16 weeks of upadacitinib treatment. QD: once daily.

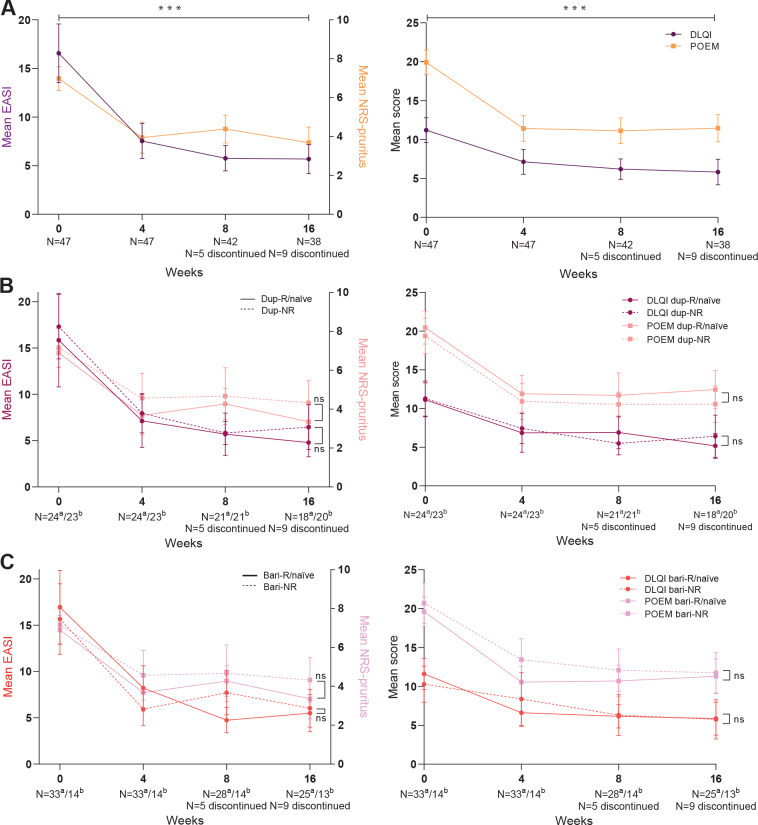

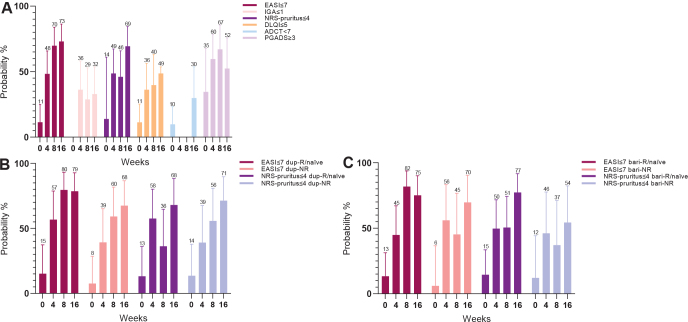

Overall effectiveness

Of the total cohort, all primary outcomes showed a significant improvement during 16 weeks of upadacitinib treatment with the largest change from baseline to week 4 (Figs 2A, 3A and Table II). The mean EASI score improved significantly from 16.6 (95% 13.6–19.6) to 5.7 (95% CI 4.3–7.2) and the mean NRS-pruritus score changed significantly from 7.0 (95% CI 6.4–7.6) to 3.7 (95% CI 2.9–4.5) (p < 0.001). At week 16, the probability of achieving EASI≤7 and NRS-pruritus ≤ 4 was 73.0% (53.7–86.3) and 69.4% (48.7–84.4), respectively. For the IGA ≤ 1, DLQI ≤ 5, ADCT < 7, and PGADS ≥ 3 the probabilities were 32.9% (95% CI 17.2–53.5), 48.6 (95% CI 26.5–71.2), 29.9% (95% CI 14.7–53.6), and 52.4% (95% CI 27.9–75.8), respectively (Table III and Fig. 3A). At week 16, 1 patient used prednisolone indicated for PMR, 1 patient used hydrocortisone indicated for a tertiary adrenal insufficiency. All patients with concomitant (or washout of) immunosuppressive/immunomodulating therapy indicated for AD were able to discontinue these treatments before week 16.

Fig 2.

Primary effectiveness outcomes (mean, 95% confidence interval (95% CI)) of 16 weeks’ treatment with upadacitinib. (A) Outcomes of the total cohort. (B) Outcomes stratified by adup-R/naïve and bdup-NR. (C) Outcomes stratified by abari-R/naïve and bbari-NR. dup-R/naïve: dupilumab responders/naïve patients; dup-NR: dupilumab non-responders; bari-R/naïve: baricitinib responders/naïve patients; bari-NR: baricitinib non-responders; EASI: Eczema Area and Severity Index; NRS: numerical rating scale; DLQI: Dermatology Life Quality Index; POEM: Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure; ns: non-significant. ***p<0.001, bars represent 95% CI.

Fig. 3.

Secondary effectiveness outcomes (probability, 95% confidence interval (95% CI)) of 16 weeks’ treatment with upadacitinib. (A) Outcomes of the total cohort. (B) Outcomes stratified by adup-R/naïve and bdup-NR. (C) Outcomes stratified by abari-R/naïve and bbari-NR. dup-R/naïve: dupilumab responders/naïve patients; dup-NR: dupilumab non-responders; bari-R/naïve: baricitinib responders/naïve patients; bari-NR: baricitinib non-responders; EASI: Eczema Area and Severity Index; NRS: numerical rating scale; DLQI: Dermatology Life Quality Index; ADCT: Atopic Dermatitis Control Tool; PGADS: Patient Global Assessment of Disease Status. Bars represent 95% CI.

Table II.

Primary effectiveness outcomes of 16 weeks’ treatment with upadacitinib in 47 patients with atopic dermatitis

| Baseline | Week 4 | Week 8 | Week 16 | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cohort | n=47 | n=47 | n=42 | n=38 | – |

| Patients who discontinued treatment, n (%) | 0 (0) | 5 (10.6) | 4 (8.5) | 5 (10.6) | – |

| Concomitant immunosuppressive therapy, n (%) | 32 (68.1) | 13 (27.7) | 4 (9.5)b | 2 (5.3)c | – |

| Primary endpoints, mean (95% CI) | |||||

| EASI score | 16.6 (13.6–19.6) | 7.5 (5.7–9.3) | 5.8 (4.5–7.1) | 5.7 (4.2–7.2) | <0.001 |

| Weekly average NRS-pruritus | 7.0 (6.4–7.6) | 3.9 (3.1–4.7) | 4.4 (3.7–5.1) | 3.7 (2.9–4.5) | <0.001 |

| DLQI score | 11.2 (9.6–12.8) | 7.1 (5.5–8.7) | 6.2 (4.9–7.5) | 5.8 (4.2–7.5) | <0.001 |

| POEM score | 19.9 (18.4–21.5) | 11.4 (9.8–13.1) | 11.1 (9.5–12.8) | 11.5 (9.7–13.2) | <0.001 |

| Responder subgroups | – | ||||

| Dup-NR | n=23 | n=23 | n=21 | n=20 | |

| Dup-R/naïve | n=24 | n=24 | n=21 | n=18 | |

| Bari-NR | n=14 | n=14 | n=14 | n=13 | |

| Bari-R/naïve | n=33 | n=33 | n=28 | n=25 | |

| Patients who discontinued treatment, n (%) | – | ||||

| Dup-NR | 0 (0) | 2 (8.7) | 1 (4.8) | 2 (10.0) | |

| Dup-R/naïve | 0 (0) | 3 (12.5) | 3 (14.3) | 3 (16.7) | |

| Bari-NR | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (7.1) | 1 (7.7) | |

| Bari-R/naïve | 0 (0) | 5 (15.2) | 3 (10.7) | 4 (16.0) | |

| Primary endpoints, mean (95% CI) | |||||

| EASI score | |||||

| Dup-NR | 17.3 (13.8–20.8) | 8.0 (5.9–10.1) | 5.8 (4.6–7.1) | 6.5 (4.0–8.9) | 0.938 |

| Dup-R/naïve | 15.8 (10.8–20.9) | 7.1 (4.3–10.0) | 5.7 (3.4–8.0) | 4.8 (3.3–6.3) | |

| Bari-NR | 15.7 (11.9–19.5) | 5.9 (4.1–7.7) | 7.7 (5.3–10.1) | 6.0 (4.0–8.1) | 0.187 |

| Bari-R/naïve | 16.9 (13.0–20.9) | 8.2 (5.8–10.6) | 4.7 (3.4–6.1) | 5.5 (3.5–7.5) | |

| Weekly average NRS-pruritus | |||||

| Dup-NR | 7.0 (6.0–7.9) | 4.4 (3.3–5.4) | 4.2 (3.4–5.1) | 3.7 (2.7–4.7) | 0.311 |

| Dup-R/naïve | 7.0 (6.2–7.8) | 3.5 (2.4–4.7) | 4.5 (3.4–5.7) | 3.7 (2.5–5.0) | |

| Bari-NR | 7.2 (6.2–8.2) | 4.6 (3.3–5.8) | 4.7 (3.2–6.1) | 4.3 (3.2–5.5) | 0.443 |

| Bari-R/naïve | 6.9 (6.1–7.7) | 3.7 (2.7–4.7) | 4.3 (3.5–5.1) | 3.4 (2.3–4.4) | |

| DLQI score | |||||

| Dup-NR | 11.3 (9.0–13.6) | 7.4 (5.5–9.4) | 5.5 (4.0–7.0) | 6.4 (3.7–9.1) | 0.601 |

| Dup-R/naïve | 11.1 (8.9–13.3) | 6.9 (4.3–9.4) | 6.9 (4.8–9.0) | 5.2 (3.6–6.8) | |

| Bari-NR | 10.3 (8.0–12.6) | 8.4 (5.0–11.8) | 6.3 (3.7–8.9) | 5.8 (3.2–8.3) | 0.541 |

| Bari-R/naïve | 11.6 (9.6–13.6) | 6.6 (4.9–8.4) | 6.2 (4.7–7.6) | 5.9 (3.7–8.0) | |

| POEM score | |||||

| Dup-NR | 19.4 (17.1–21.7) | 10.9 (8.6–13.2) | 10.5 (9.0–12.1) | 10.6 (8.2–12.9) | 0.970 |

| Dup-R/naïve | 20.5 (18.3–22.6) | 11.9 (9.5–14.3) | 11.7 (8.8–14.6) | 12.4 (10.0–14.9) | |

| Bari-NR | 20.7 (18.1–23.3) | 13.4 (10.8–16.1) | 12.1 (9.3–14.8) | 11.7 (8.9–14.2) | 0.679 |

| Bari-R/naïve | 19.6 (17.7–21.5) | 10.6 (8.6–12.5) | 10.7 (8.7–12.7) | 11.3 (9.2–14.3) | |

p-values based on overall likelihood ratio tests for time. – Not measured.

Data after multiple imputation.

AD: atopic dermatitis; 95% CI; 95% confidence interval; dup: dupilumab; bari: baricitinib; NR: non-responders; R/naïve: responders/naïve patients; EASI: Eczema Area and Severity Index; IGA: Investigator Global Assessment; NRS: numerical rating scale; DLQI: Dermatology Life Quality Index; POEM: Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure; ADCT: Atopic Dermatitis Control Tool; PGADS: Patient Global Assessment of Disease Status.

Table III.

Secondary effectiveness outcomes of 16 weeks’ treatment with upadacitinib in 47 patients with atopic dermatitis

| Baseline | Week 4 | Week 8 | Week 16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cohort, probability % (95% CI) | ||||

| EASI≤7 | 11.4 (4.7–24.9) | 48.3 (31.1–65.8) | 69.8 (50.7–83.9) | 73.0 (53.7–86.3) |

| IGA≤1 | NA | 36.2 (18.9–58.1) | 28.8 (12.7–52.9) | 32.9 (17.2–53.5) |

| NRS-pruritus≤4 | 13.9 (6.1–28.9) | 48.6 (30.4–67.3) | 46.0 (27.3–65.9) | 69.4 (48.7–84.4) |

| DLQI≤5 | 11.3 (4.6–25.2) | 36.2 (19.9–56.3) | 39.7 (20.3–63.0) | 48.6 (26.5–71.2) |

| ADCT<7 | 9.8 (3.8–23.2) | – | – | 29.9 (13.7–53.6) |

| PGADS≥3 | 34.5 (11.7–67.7) | 59.6 (37.7–78.3) | 67.0 (41.2–85.5) | 52.4 (27.9–75.8) |

| Responder subgroups, probability % (95% CI) | ||||

| EASI≤7 | ||||

| Dup-NR | 7.6 (0.2–28.6) | 39.3 (18.3–65.2) | 59.5 (32.5–81.8) | 67.5 (39.7–86.7) |

| Dup-R/naïve | 15.2 (5.1–37.4) | 56.8 (31.8–78.8) | 79.6 (52.7–93.2) | 78.6 (50.9–92.8) |

| Bari-NR | 6.0 (0.7–36.6) | 56.0 (24.6–83.3) | 45.3 (17.2–76.7) | 69.7 (36.0–90.4) |

| Bari-R/naïve | 13.4 (5.0–31.3) | 44.9 (24.6–67.1) | 81.8 (57.8–93.7) | 75.1 (50.2–90.0) |

| IGA≤1 | ||||

| Dup-NR | NA | 32.5 (11.4–64.2) | 16.4 (2.6–59.5) | 22.2 (6.7–53.0) |

| Dup-R/naïve | 39.6 (17.9–66.4) | 40.4 (17.9–67.9) | 44.3 (20.1–71.5) | |

| Bari-NR | 35.5 (11.0–71.0) | 17.6 (3.0–59.8) | 36.4 (12.4–70.0) | |

| Bari-R/naïve | 36.3 (16.7–61.9) | 34.0 (14.0–62.5) | 30.6 (12.7–57.2) | |

| NRS-pruritus≤4 | ||||

| Dup-NR | 13.6 (3.9–37.9) | 39.1 (16.5–67.6) | 55.8 (27.3–80.9) | 71.4 (41.6–89.8) |

| Dup-R/naïve | 13.2 (4.0–36.0) | 57.6 (31.4–80.2) | 36.3 (15.0–64.8) | 68.0 (37.3–88.4) |

| Bari-NR | 12.1 (2.3–44.3) | 46.1 (17.4–77.6) | 37.1 (12.5–71.1) | 54.4 (22.7–82.3) |

| Bari-R/naïve | 14.5 (5.4–33.5) | 49.7 (27.7–71.7) | 50.5 (26.5–74.3) | 77.3 (51.4–91.6) |

| DLQI≤5 | ||||

| Dup-NR | 7.7 (1.6–29.6) | 23.1 (6.8–55.2) | 44.9 (18.9–74.0) | 49.9 (19.8–80.0) |

| Dup-R/naïve | 14.2 (4.5–37.1) | 48.8 (23.5–74.7) | 33.7 (11.0–67.6) | 46.5 (16.7–79.1) |

| Bari-NR | 11.7 (2.3–43.0) | 27.8 (6.8–66.8) | 40.6 (11.0–79.0) | 52.7 (19.1–84.0) |

| Bari-R/naïve | 10.8 (3.5–28.5) | 39.3 (19.5–63.4) | 38.9 (16.2–67.7) | 46.3 (20.0–74.9) |

| ADCT<7 | ||||

| Dup-NR | 11.8 (3.3–34.3) | – | – | 28.8 (9.1–61.9) |

| Dup-R/naïve | 7.5 (1.6–28.5) | 30.3 (9.3–64.9) | ||

| Bari-NR | 6.4 (0.8–38.3) | 25.9 (5.8–66.4) | ||

| Bari-R/naïve | 11.0 (3.7–28.5) | 31.5 (12.4–59.8) | ||

| PGADS≥3 | ||||

| Dup-NR | 31.4 (6.0–76.7) | 53.9 (26.6–79.0) | 69.6 (30.4–92.3) | 55.2 (23.5–83.2) |

| Dup-R/naïve | 36.8 (13.1–69.2) | 65.3 (36.9–85.8) | 65.0 (36.8–85.5) | 49.3 (20.9–78.1) |

| Bari-NR | 44.4 (10.4–84.6) | 58.8 (21.8–88.0) | 63.1 (24.6–90.0) | 61.9 (26.8–87.8) |

| Bari-R/naïve | 29.8 (7.7–68.2) | 60.1 (36.5–79.8) | 69.2 (41.6–87.6) | 47.5 (19.9–76.7) |

Data after multiple imputation. 95% CI: 95% confidence Interval; dup-NR: dupilumab non-responders; dup-R/naïve: dupilumab naïve/responders; bari-NR: baricitinib non-responders; bari-R/naïve: baricitinib naïve/responders; EASI: Eczema Area and Severity Index; NRS: numerical rating scale; DLQI: Dermatology Life Quality Index; PGADS: Patient Global Assessment of Disease Status; NA: not applicable; –: not measured.

Differences in treatment response and disease course of patients treated with upadacitinib 15 mg once daily vs 30 mg once daily are shown in Fig. 1, Tables SII and SIII. In total, 7 (14.9%) patients switched from 15 mg to 30 mg once daily due to inadequate response on upadacitinib treatment. Only 1 patient (2.1%) switched from 30 mg to 15 mg once daily due to controlled disease (Table SIII). All 4 (8.5%) patients who discontinued treatment due to ineffectiveness were treated with upadacitinib 30 mg once daily. Three of these patients (75.0%) also had inadequate response to previous dupilumab treatment, of which 1 patient also failed on baricitinib treatment. All 3 (6.4%) patients who discontinued upadacitinib treatment due to a combination of ineffectiveness and AEs were treated with upadacitinib 15 mg once daily (Fig. 1). The decision to discontinue treatment due to ineffectiveness was made by shared-decision making and was based on the EASI and NRS-pruritus.

Dupilumab and baricitinib (non-)responders

In total, 24 dup-R/naïve vs 23 dup-NR and 33 bari-R/naïve vs 14 bari-NR were included of which differences in baseline characteristics are shown in Table I. In the bari-R/naïve group only 1 baricitinib responder was included; all other 32 patients were naïve for baricitinib treatment. Overall, no significant differences on effectiveness over time were found between the dup-NR vs dup-R/naïve and bari-NR vs bari-R/naïve groups (Figs 2B, 2C, 3B, 3C and Table II). Of the 7 patients who previously failed on both dupilumab and baricitinib treatment, only 1 patient discontinued upadacitinib treatment, due to ineffectiveness in the first 16 weeks (Table SIV).

Safety

In total 57 AEs were reported during 16 weeks of upadacitinib treatment, of which 36 patients (76.6%) experienced at least 1 AE (Table IV). The majority of AEs were evaluated as mild (77.2%). Most frequently reported AEs were acneiform eruptions (n = 10, 21.3%), herpes simplex infections (n = 6, 12.8%), nausea and upper airway infections (both n = 4, 8.5%). A total of 14 laboratory abnormalities were documented (Table IV), mostly increased triglycerides levels or increased CPK (both n = 4, 8.5%). Seven patients (14.9%) discontinued treatment due to 1 or more AEs (all treated with upadacitinib 15mg once daily). One patient experienced dyspnoea a few weeks after treatment initiation, which could not be explained by an underlying disease or illness. Another patient, who experienced worsening of itch, pain and erythematous lesions after initial response to upadacitinib treatment, developed a reactive lymphoid infiltrate in the skin. All of the AEs permanently leading to treatment discontinuation diminished or resolved after upadacitinib was stopped.

Table IV.

Reported adverse events and laboratory abnormalities in 47 patients with atopic dermatitis during 16 weeks’ upadacitinib treatment

| Adverse events | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Number of patients with AE | 36 (76.6) |

| Total number of AEs | 57 |

| Severity of AEs | |

| Mild | 44 (77.2) |

| Moderate | 8 (14.0) |

| Severe | 5 (8.8) |

| Number of patients with AE leading to treatment discontinuation | 7 (14.9) |

| Dyspnoea | 1 (2.1) |

| Nausea | 1 (2.1) |

| Recurrent herpes simplex | 1 (2.1) |

| Reactive lymphoid infiltrate | 1 (2.1) |

| Elevated liver enzymes † | 1 (2.1) |

| Combination of headache and acne | 1 (2.1) |

| Combination of headache, nausea, acne | 1 (2.1) |

| Infections | 14 (29.8) |

| Herpes simplex | 6 (12.8) |

| Upper airway infection | 4 (8.5) |

| Herpes zoster* † | 2 (4.3) |

| Impetiginization | 1 (2.1) |

| Folliculitis | 1 (2.1) |

| Non-infectious skin-related | 14 (29.8) |

| Acneiform eruptions | 10 (21.3) |

| Hair growth** | 1 (2.1) |

| Psoriasis pustulosa | 1 (2.1) |

| Reactive lymphoid infiltrate | 1 (2.1) |

| Hair loss | 1 (2.1) |

| General | 8 (17.0) |

| Weight gain | 3 (6.4) |

| Headache | 3 (6.4) |

| Fever | 1 (2.1) |

| Malaise | 1 (2.1) |

| Gastrointestinal | 4 (8.5) |

| Nausea | 4 (8.5) |

| Other | 4 (8.5) |

| Dry eyes | 1 (2.1) |

| Paraesthesia | 1 (2.1) |

| Renal calculi | 1 (2.1) |

| Dyspnoea | 1 (2.1) |

| Laboratory abnormalities | 14 (29.8) |

| Hypertriglyceridaemiaa | 4 (8.5) |

| Increase of CPKb † | 4 (8.5) |

| Hypercholesterolaemiac | 3 (6.4) |

| Increase of ALATb † | 2 (4.3) |

| Increase of creatinined † | 1 (2.1) |

Upadacitinib treatment was temporarily discontinued.

Referring to a patient with alopecia areata.

Adverse events of special interest according clinical trials with upadacitinib treatment (10).

Triglycerides > 2.0 mmol/l.

Increase > 3 times upper limit of normal (ULN).

Hypercholesterolaemia > 8.0 mmol/L.

Creatinine increase of > 130%.

Other reference categories; anaemia: haemoglobin < 8.5 mmol/l (men) or < 7.5 mmol/l (women) and if clinically relevant by physician’s decision, leukocytes < 2.0× 109/l, thrombocytosis >600× 109/l, neutropaenia < 1.0× 109/l, lymphocytopaenia < 0.5× 109/l. AE: adverse event; ALAT: alanine aminotransferase; CPK: creatinine phosphokinase.

DISCUSSION

This study provides insight into the clinical effectiveness of upadacitinib treatment in adult patients with moderate-to-severe AD who failed on multiple systemic therapies including biological and/or small molecule treatment (dupilumab and baricitinib) in a real-world setting. Both clinical outcomes and PROMs improved significantly during 16 weeks of upadacitinib treatment with a rapid change in the first 4 weeks, even in patients with previous inadequate response to dupilumab and/or baricitinib treatment. However, a subgroup of patients (29.8%) discontinued upadacitinib treatment due to ineffectiveness, AEs or both (8.5%, 14.9% and 6.4%, respectively).

This study found that upadacitinib effectively reduced clinician- and patient-reported outcomes in patients with AD. The probability of achieving EASI≤7 and NRS-pruritus≤4 after 4 weeks of treatment was 48.3% and 48.6%, respectively. After 16 weeks of treatment, these outcomes further improved, to a probability of 73.0% and 69.4%, respectively. In addition, the probability of achieving PGADS≥3 was 52.4%, which indicates a good to excellent well-being regarding AD. However, the results on clinical effectiveness of upadacitinib might be underestimated, as more than two-thirds of the patients were using concomitant systemic treatment at upadacitinib initiation, leading to lower EASI scores at baseline, and resulting in a smaller difference between baseline and follow-up scores. Since a minority of the patients was treated with 30 mg once daily, profound statistical analyses on differences between 15 mg and 30 mg treatment groups were difficult to perform. During upadacitinib treatment, 7 patients switched from 15 mg to 30 mg once daily due to inadequate response. In 4 of these patients, 30 mg once daily was still inadequate and upadacitinib was discontinued. Three (6.4%) patients who discontinued upadacitinib treatment due a combination of ineffectiveness and AEs were treated with upadacitinib 15 mg once daily. Nevertheless, AD severity decreased significantly (based on EASI≤7 and NRS-pruritus≤4) in almost three-quarters of the cohort, which was mostly achieved by an upadacitinib dosage of 15 mg once daily.

Interestingly, no significant differences were found in effectiveness between dup/bari-NR and dup/bari-R/naïve. The study hypothesis was that patients who previously failed on multiple systemic treatments due to ineffectiveness were more difficult to treat. However, on the primary endpoints, dupilumab and baricitinib-NR achieved a similar response on upadacitinib compared with the R/naïve group, which is an important finding. On the secondary endpoints, the dup-R/naïve tended to have a better effect in the first 4 weeks of treatment than the dup-NR, which difference diminished in weeks 4–16. The temporary difference might be explained by the fact that the dup-R/naïve group had slightly less severe AD (lower IGA scores) and fewer patients using other systemic treatments at upadacitinib initiation. Since the bari-R/naïve group mainly consisted of baricitinib-naïve patients, it was not possible to perform a comparison with baricitinib responders. Also, the 6/7 patients with inadequate response to both dupilumab and baricitinib treatment, indicating very difficult-to-treat AD, showed a substantial improvement in AD severity during upadacitinib treatment. Even though not all patients achieved an EASI≤7 and/or NRS-pruritus≤4, these results suggest that patients with inadequate response to dupilumab and/or baricitinib treatment can benefit from treatment with upadacitinib.

To compare the current results with clinical trials, some difficulties need to be addressed. Concomitant use of systemic immunosuppressive treatment is an exclusion criterion in clinical trials (10, 11); however, in the current study 68.1% of the patients did not fulfil the washout criteria of immunosuppressive drugs at baseline, which might have led to lower clinical scores at baseline and an underestimation of the effectiveness of upadacitinib. As a consequence, it might be more difficult to achieve relative outcomes (e.g. EASI-75) as used in clinical trials. Therefore, we used absolute cut-off scores, as defined by international expert consensus (24), to measure the effectiveness of upadacitinib more adequately in a real-life setting. Furthermore, the use (or washout) of concomitant immunosuppressive treatment at baseline, as well as the fact that 93.6% and 29.4% failed on previous biological or small molecule treatment, respectively, implicates a more difficult-to-treat cohort in the current study. In clinical trials all patients were naïve for biological or small molecule treatment (10, 11). The only endpoint that is similar in the current study and in clinical trials is the IGA≤1: this was achieved in 38.8–62.0% of the patients in clinical trials, compared with 32.9% in our daily practice study (10, 11). Other endpoints used in clinical trials were not comparable with the current study results.

At present, few studies have been published on the effectiveness of upadacitinib in daily practice (13–16). These studies mostly used other endpoints, which makes it difficult to compare the results with those of the current study. Only the study of Chiricozzi et al. (16) used several similar endpoints as used in the current study. They found that 94.9–97.5% of the patients achieved an EASI≤7, NRS-pruritus≤4 and DLQI≤5. In 3 studies all patients were treated with 30 mg once daily, whereas in the current study only a minority of the patients was treated with the highest dose (13, 15, 16). The current study found that most of the patients could achieve controlled AD by using 15 mg once daily; increasing the dose to 30 mg once daily in patients with suboptimal response was not always possible due to AEs. Almost all patients included in the published daily practice studies were previously treated with dupilumab. However, it remains unknown whether they discontinued dupilumab treatment due to non-responsiveness or AEs (suggesting a less difficult-to-treat AD). In the current study 29.5% and 22.7% of the patients, respectively, discontinued previous dupilumab treatment due to ineffectiveness or a combination of ineffectiveness and AEs. Moreover, in the published daily practice studies it is unclear if, and how many, patients were in the washout of other systemic immunosuppressive treatment, which might have influenced the reported effectiveness of upadacitinib in these studies (13–16). Therefore, outcome measures and thereby corresponding effectiveness of upadacitinib might differ between daily practice studies.

A considerable number of patients (76.6%) experienced 1 or more AEs during 16 weeks of upadacitinib treatment, most of them being mild to moderate. This is slightly higher than described in clinical trials (60.0–73.0%) (10, 11). In other daily practice studies only 30.2–37.2% of the patients experienced an AE, which is remarkably low (15, 16). Most frequently reported AEs and laboratory abnormalities in the current study were similar, as observed in both clinical and daily practice studies (e.g. acneiform eruptions, herpes simplex/zoster infections, upper airway infections, nausea and increased CPK) (10, 11, 13–16, 28). In 7 (14.9%) patients upadacitinib was permanently discontinued due to at least 1 AE. Dyspnoea without any underlying disease and a reactive lymphoid skin infiltrate were not previously described as possible AE during upadacitinib treatment.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the clinical effectiveness of upadacitinib treatment in patients with an inadequate response to dupilumab and/or baricitinib. Another strength is the multicentre and prospective design, together with the use of many validated clinical outcomes and PROMs at baseline and week 4/8/16 visits. However, the study is limited by the amount of missing data, which was caused mainly by a relatively low response rate on the PROMs. Multiple imputation was therefore applied. Also, confidence intervals of several primary and secondary effectiveness outcomes are rather wide, which is probably reflected by the relatively small sample size. Daily practice data based on a larger cohort are needed to define the outcomes more precisely. Furthermore, the concomitant use of immunosuppressive treatment at baseline, and the patients who prematurely discontinued upadacitinib treatment, might have influenced the current results. For that reason, a bias could not fully be excluded. Nevertheless, these limitations reflect real-world daily practice.

Conclusion

Upadacitinib is an effective treatment for patients with moderate-to-severe AD, including those with previous inadequate response to dupilumab and/or baricitinib treatment. A relatively high proportion of patients experienced 1 or more AEs, which led to (temporary) treatment discontinuation in several patients. This study demonstrates the additional value of daily practice data to assess the benefit-risk profile of upadacitinib in patients with AD, including very difficult-to-treat patients.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Patients included in this study participated in the BioDay registry sponsored by Eli Lilly, Sanofi Genzyme, Leo Pharma, Abbvie and Pfizer.

The study was approved by the local medical research ethics committee as a non-interventional study (METC 18-239) and was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Conflicts of interest

CMB is a speaker for Abbvie and Eli Lilly. BSB is a speaker for Sanofi Genzyme and LEO Pharma. LSS is a speaker for Abbvie. IMH is a consultant, advisory board member, and/or speaker for Sanofi Genzyme and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, LEO Pharma, AbbVie, Janssen and Eli Lilly. MdG is a consultant, advisory board member, and/or speaker for Sanofi Genzyme and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, LEO Pharma, Pfizer, Abbvie, Novartis, and Eli Lilly. MSdB-W is a consultant, advisory board member, and/or speaker for AbbVie, Almirall, Aslan, Arena, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Janssen, Leo Pharma, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Sanofi-Genzyme. LFvsG, NPAZ and MK have nothing to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weidinger S, Novak N. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet 2016; 387: 1109–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbarot S, Auziere S, Gadkari A, Girolomoni G, Puig L, Simpson EL, et al. Epidemiology of atopic dermatitis in adults: results from an international survey. Allergy 2018; 73: 1284–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pereyra-Rodriguez JJ, Alcantara-Luna S, Dominguez-Cruz J, Galan-Gutierrez M, Ruiz-Villaverde R, Vilar-Palomo S, et al. Short-term effectiveness and safety of biologics and small molecule drugs for moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Life 2021; 11: 927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Domaingroup Allergy and Eczema and Association for Atopic Dermatitis (VMCE), the Netherlands . Dupilumab (opinion). Published April 2018 [accessed August 4, 2022]. Available from https://nvdv.nl/professionals/nvdv/standpunten-en-leidraden/introductie-van-dupilumab-voor-ernstig-constitutioneel-eczeem-ce-standpunt

- 5.Miniotti M, Lazzarin G, Ortoncelli M, Mastorino L, Ribero S, Leombruni P. Impact on health-related quality of life and symptoms of anxiety and depression after 32 weeks of dupilumab treatment for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Ther 2022; 35: e15407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Domaingroup Allergy and Eczema and Association for Atopic Dermatitis (VMCE), the Netherlands . Baricitinib (opinion). Published December 2020 [accessed August 4, 2022]. Available from https://nvdv.nl/professionals/nvdv/standpunten-en-leidraden/baricitinib-standpunt

- 7.He Helen, Guttman-Yasky E. JAK inhibitors for atopic dermatitis: an update. Am J Clin Derm 2019; 20: 181–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Domaingroup Allergy and Eczema and Association for Atopic Dermatitis (VMCE), the Netherlands . Upadacitinib (opinion). Published October 2021 [accessed August 4, 2022] Available from https://nvdv.nl/nvdv/standpunten-en-leidraden/upadacitinib-standpunt

- 9.Nezamololama N, Fieldhouse K, Metzger K, Gooderham M. Emerging systemic JAK inhibitors in the treatment of atopic dermatitis: a review of abrocitinib, baricitinib, and upadacitinib. Drugs in Context 2020; 9: 5–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guttman-Yassky E, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, Papp KA, Pangan AL, Blauvelt, et al. Once-daily upadacitinib versus placebo in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2): results from two replicate double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet 2021; 397: 2151–2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reich K, Teixeira HD, de Bruin-Weller M, Bieber T, Soong W, Kabashima K, et al. Safety and efficacy of upadacitinib in combination with topical corticosteroids in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD Up): results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2021; 397: 2169–2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blauvelt A, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, Costanzo A, de Bruin-Weller M, Barbarot S, et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib vs dupilumab in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2021; 157: 1047–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Napolitano N, Fabbrocini G, Genco L, Martora F, Potestio L, Patruno C. Rapid improvement in pruritus in atopic dermatitis patients treated with upadacitinib: a real-life experience. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2022; 36: 1497–1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feraru G, Nevet MJ, Samuelov L, Hodak E, Avitan-Hersh E, Ziv M, et al. Real-life experience of upadacitinib for the treatment of adult patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis - a case series. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2022; 36: e832–e833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pereyra-Rodriguez JJ, Herranz P, Figueras-Nart I, Perez B, Elosua M, Munera-Campos M, et al. Treatment of severe atopic dermatitis with upadacitinib in real clinical practice. Short-term efficacy and safety results. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2022; Jun 2. [Online ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiricozzi A, Gori N, Narcisi A, Balato A, Gambardella A, Ortoncelli M, et al. Effectiveness and safety of upadacitinib in the treatment of moderate‑severe atopic dermatitis: a multicentric, prospective, real‑world, cohort study. Drugs in R&D 2022; 22: 245–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leshem YA, Hajar T, Hanifin JM, Simpson EL. What the Eczema Area and Severity Index score tells us about the severity of atopic dermatitis: an interpretability study. Br J Dermatol 2015; 172: 1353–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Futamara M, Leshem YA, Thomas KS, Nankervis H, Williams HC, Simpson EL. A systematic review of Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) in atopic dermatitis (AD) trials: many options, no standards. JAAD 2016; 74: 288–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phan NQ, Blome C, Fritz F, Gerss J, Reich A, Ebata T, et al. Assessment of pruritus intensity: prospective study on validity and reliability of the visual analogue scale, numerical rating scale and verbal rating scale in 471 patients with chronic pruritus. Acta Derm Venereol 2012; 92: 502–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) – a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol 1994; 19: 210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charman CR, Venn AJ, Williams HC. The Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure: development and initial validation of a new tool for measuring atopic eczema severity from the patients’ perspective. Arch Dermatol 2004; 140: 1513–1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Griffiths C, de Bruin-Weller M, Deleuran M, Concetta Fargnoli M, Staumont-Sallé D, et al. Dupilumab in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis and prior use of systemic non-steroidal immunosuppressants: analysis of four phase 3 trials. Dermatol Ther 2021; 11: 1357–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pariser DM, Simpson EL, Gadkari A, Bieber T, Margolis DJ, Brown M, et al. Evaluating patient-perceived control of atopic dermatitis: design, validation, and scoring of the Atopic Dermatitis Control Tool (ADCT). Curr Med Res Opin 2020; 36: 367–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Bruin-Weller M, Biedermann T, Bissonnette R, Deleuran M, Foley P, Girolomoni G, et al. Treat-to-target in atopic dermatitis: an International Consensus on a set of core decision points for systemic therapies. Acta Derm Venereol 2021; 17: 101–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Donders ART, Van der Heijden GJMG, Stijnen T, Moons KGM. Review: a gentle introduction to imputation of missing values. J Clin Epidemiol 2006; 59: 1087–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Graham JW, Olchowski AE, Gilreath TD. How many imputations are really needed? Some practical clarifications of multiple imputation theory. Prev Sci 2007; 8: 206–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robitzsch A, Grund S. Miceadds: Some Additional Multiple Imputation Functions, Especially for ’mice’. R package version 3.13-1. 2022. [Accessed 17 August 2022] Available from: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/miceadds/index.html.

- 28.RStudio Team . RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA. 2020. [Accessed 17 August 2022] Available from: URL:http://www.rstudio.com/. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guttman-Yassky E, Thyssen JP, Silverberg JI, Papp KA, Paller AS, Weidinger S, et al. Safety of upadacitinib in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: an integrated analysis of phase 3 studies. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2023; 151: 172–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.