Abstract

Acute severe bronchial asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by hyperresponsiveness of the airways leading to bronchoconstriction. We present a case of refractory life‐threatening bronchial asthma that was managed with sevoflurane gas along with the standard treatment and achieved stability and clinical improvement through its bronchodilator and anesthetic effect.

Keywords: asthma, bronchodilators, corticosteroids, inhalation anesthesia, sevoflurane

1. INTRODUCTION

Acute severe asthma is a life‐threatening emergency characterized by severe tachypnea, tachycardia, and type 1 respiratory failure. 1 According to the international standard guidelines, it is managed with bronchodilators, systemic steroids, and magnesium sulfate in emergency cases. 2 Here, we describe a case of a 38 years old male who presented with a severe asthmatic attack resistant to conventional therapy of bronchodilators and corticosteroids. Subsequently, the patient was started on noninvasive ventilator support; he could not tolerate it and was intubated. Later the patient had a good recovery after managing with an anesthetic inhalation agent sevoflurane and mechanical ventilator support by using an anesthesia machine. This case report highlights the potential management of severe acute asthma in the critical care unit with sevoflurane.

2. CASE PRESENTATION

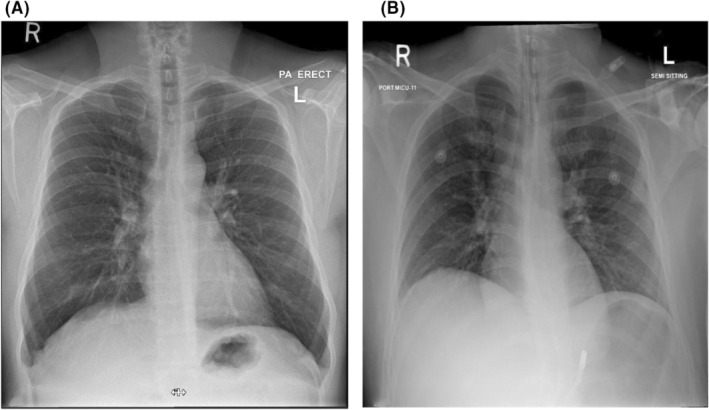

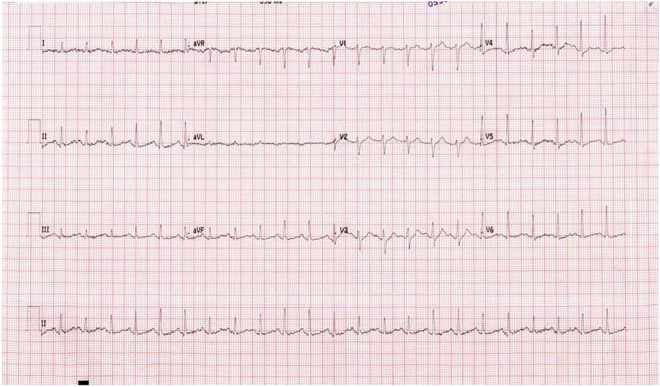

A 38‐year‐old man with a background of bronchial asthma presented to the Emergency Department with a 2‐day history of progressive shortness of breath following cold exposure. He was on a regular metered‐dose inhaler of Salbutamol 100 μg, one puff Q6hrly at home. He mentioned having a mild cough and audible wheezes before admission but no associated fever, rhinorrhea, cough, or upper respiratory tract symptoms. He was compliant with his medications. The patient had a recent admission with a severe asthma attack treated with intravenous corticosteroids with Hydrocortisone 200 mg three times daily, nebulizer therapy Budesonide 500 μg BID, Salbutamol 2.5 mg Q8hrly, Ipratropium bromide 125 μg QID 2 days before this admission. He was discharged home with a salbutamol inhaler, one puff Q6H, and a Budesonide inhaler 500 μg two puff BID. On day two of discharge, the patient was readmitted with complaints of cough and audible wheezes. On clinical assessment, he was oriented but was unable to complete entire sentences. He was using accessory muscles for breathing. Vitally, he had tachypnea of 35 breaths/min, oxygen saturation of 99% on 10 L of the nonrebreather oxygen mask, tachycardia of 145 beats/min, and blood pressure of 145/91 mmHg, and an oral temperature of 37.3°C. His chest XR is shown in Figure 1A and was unremarkable for any pulmonary infiltrates, pneumothorax, pleural effusion, or pathology. Initial ECG was also unremarkable, as mentioned in Figure 2. Initial arterial blood gas revealed respiratory acidosis, pH 7.314, PCO2 72 mmHg, PO2 132 mmHg and the bicarbonate level 32 mEq/L. Salbutamol 2.5 mg Q2hrly and Ipratropium bromide 125 μg Q2hrly nebs were given immediately.

FIGURE 1.

(A) Before intubation and (B) after intubation

FIGURE 2.

Unremarkable ECG

Nevertheless, the patient kept deteriorating clinically. He was given 4 g of magnesium sulfate along with a trial of noninvasive ventilation (NIV) with the settings of ST (spontaneous timed) mode, PS (pressure support) 12, PEEP (positive end‐expiratory pressure) 6, and FiO2 40%. Arterial blood gases showed worsening respiratory acidosis—pH 7.130, PCO2 83 mmHg, PO2 111 mmHg, and HCO3 30 mEq/L. Due to the increased work of breathing and drowsy state of the patient, he was intubated and started on mechanical ventilation with volume‐controlled mode, and settings of tidal volume 450 ml, respiratory rate of 14 breaths/min, PEEP of 5 cm·H2O, and FiO2 of 60%. Chest XR postintubation is shown in Figure 1B. The flow volume scale was not touching the baseline due to severe bronchial constriction. The metered‐dose inhaler was started with bronchodilator therapy and steroids (Salbutamol 2.5 mg Q4hrly through the endotracheal tube). Auto‐PEEP showed 4 cm·H2O. Settings were altered as Inspiratory (I): Expiratory (E) ratio from 1:2.5 to 1:5. Secretions were cleared with closed inline suctioning regularly. Two days later, the patient did not show any improvement. Subsequently, it was decided by the ICU team to give bronchodilator therapy through an anesthetist agent, sevoflurane, in‐between 0.5% and 2% for 48 h. After starting inhaling sevoflurane patient, the peak pressure started to come down. Presevoflurane therapy and postsevoflurane therapy pressures are summarized in Table 1. The arterial blood gas showed an improvement in ventilation. The comparison of ABG values is also mentioned in Table 2. The patient gradually improved and was eventually extubated without any complications.

TABLE 1.

The comparison of ventilator status from pretherapy and post‐therapy treatment with sevoflurane

| Pressures | Pretherapy | Post‐therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Ppeak | 48 cm·H2O | 30 cm·H2O |

| Pplat | 22 cm·H2O | 23 cm·H2O |

| Stat. comp | 21.6 cm·H2O | 26 cm·H2O |

| Auto‐PEEP | 4 cm·H2O | 0 |

Abbreviations: Ppeak, peak pressure; Pplat, plateau pressure; Stat. comp, static lung compliance.

TABLE 2.

The ABG values from pretherapy and postsevoflurane therapy treatment

| ABG | Pretherapy | Post‐therapy |

|---|---|---|

| pH | 7.314 | 7.443 |

| PCO2 | 72 mmHg | 38 mmHg |

| PO2 | 132 mmHg | 102 mmHg |

| HCO3 | 32 mEq/L | 25.9 mEq/L |

| Lactate | 0.40 | 0.40 |

Abbreviations: HCO3, bicarbonate; PCO2, partial pressure of carbon dioxide; pH, hydrogen ion; PO2, partial pressure of oxygen.

3. DISCUSSION

Severe bronchial asthma can be life‐threatening if not timely managed. However, patient response varies even on a standard guideline treatment. Ng et al. 3 described acute asthma as a dangerous disease‐causing acute dyspnea leading to increase work of breathing. In the United States, 1.8‐million asthma attack cases visit the emergency department annually. Nearly 10 cases of death occur per day. 4 Most patients will recover with standard treatment. However, few cases reported resistant status‐asthmaticus, which responded only to sevoflurane and the standard treatment. 3 Our case describes the successful treatment of inhaled anesthesia gas in addition to standard treatment. Inhaled anesthesia gas (sevoflurane) has been shown to reduce Auto‐PEEP, bronchial constriction, and dynamic hyperinflation. 4 sevoflurane has a rapid bronchodilator effect and smooth muscle relaxant effect, easily ventilating the patient without asynchrony. sevoflurane is usually used in anesthesia to sedate the patient during a procedure; in selected cases, only using sevoflurane in critical care settings. 5 The main drawbacks of sevoflurane use are its high cost, monitoring, and scavenging of exhaled gas. With conservative anesthesia devices, the exhaled gas and sevoflurane can be filtered and reused. 2 Intravenous sedation could be reduced or discontinued during sevoflurane administration through ventilator support. 6 Soukup et al. evaluated the impact of sevoflurane during long‐term treatment of critical care unit patients, which showed high effectiveness on patient safety and reduced weaning time in comparison with standard conventional intravenous sedation concept. 7 Routine use of sevoflurane is easily feasible, effective, and safe, has a short awakening time, and has an adequate bronchodilator effect. 8 Current studies show that sevoflurane has significant bronchodilator properties and is an effective treatment option for severe acute asthma before rescue therapies. 9 The beneficial effect of sevoflurane in our case is supported by alveolar unit and distal airway dilation, which reduce distortion of the surrounding parenchyma and amount of alveolar collapse and finally reduce viscoelastic stress adaptation. sevoflurane has a rapid bronchodilator effect and muscle relaxant properties by reducing intracellular calcium in smooth muscle cells to ventilate the patient efficiently without asynchrony. 10 Despite the presence of nephrotoxic metabolites upon sevoflurane degradation, it can be considered a safe option in long‐term use and challenging intubation case scenarios. 11 , 12 This case aims to show there is an effect of sevoflurane for acute severe asthma cases treatment in addition to standard treatment.

4. CONCLUSION

Our objective is to highlight the potential of sevoflurane in the management of severe acute asthma refractory to standard management in mechanically ventilated patients. sevoflurane can be considered a lifesaving add‐on therapy to the standard treatment of severe asthma in resourceful countries. Considering endotracheal intubation should not be delayed in severe asthma to avoid fatal outcomes. Further meta‐analysis and studies are recommended to evaluate the long‐term efficacy and clinical applicability.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Satheesh Munusamy: Conceptualization; investigation; methodology; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Seyedeh Saba Nabavi Monfared: Writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Phool Iqbal: Formal analysis; supervision; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Ahmed Lutfe Mohamad Abdussalam: Supervision; visualization.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research has been funded by Qatar National Library.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors certify that they have no conflict of interest and no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial or nonfinancial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

The study is conducted ethically in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

CONSENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this report in accordance with the journal's patient consent policy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

None.

Munusamy S, Monfared SSN, Iqbal P, Abdussalam ALM. Challenging case of severe acute asthma in a mechanically ventilated patient managed with sevoflurane. Clin Case Rep. 2023;11:e06571. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.6571

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

None.

REFERENCES

- 1. 2022. [online]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6157154/v. Accessed February 20, 2022.

- 2. Sorour K, Vyas PA, Raval DS, et al. Successful treatment of severe asthma exacerbation with sevoflurane inhalation in the intensive care unit. J Anesth Crit Care Open Access. 2015;3(2):11‐12. doi: 10.15406/jaccoa.2015.03.00092 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ng D, Fahimi J, Hern HG. Sevoflurane administration initiated out of the ED for life‐threatening status asthmaticus. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33(8):1110.e3‐6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Keenan LM, Hoffman TL. Refractory status asthmaticus: treatment with sevoflurane. 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6837338/ Accessed February 23, 2022. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5. Ruszkai Z, Bokrétás GP, Bartha PT. Sevoflurane therapy for life‐threatening acute severe asthma: a case report. Can J Anaesth. 2014;61(10):943‐950. doi: 10.1007/s12630-014-0213-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sackey PV, Martling CR, Radell PJ. Three cases of PICU sedation with isoflurane delivered by the 'AnaConDa'. Paediatr Anaesth. 2005;15(10):879‐885. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2005.01704.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Soukup J, Selle A, Wienke A, Steighardt J, Wagner NM, Kellner P. Efficiency and safety of inhalative sedation with sevoflurane in comparison to an intravenous sedation concept with propofol in intensive care patients: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2012;13:135. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-13-135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. L'her E, Dy L, Pili R, et al. Feasibility and potential cost/benefit of routine isoflurane sedation using an anesthetic‐conserving device: a prospective observational study. Respir Care. 2008;53(10):1295‐1303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Littlefield L, Donaldson R, Kagunye S, Bilello K, Balasubramanian V. Successful use of inhaled Sevoflurane in refractory adult status asthmaticus: a case series. CHEST. 2019;158(4):A53‐A54. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Prakash YS, Iyanoye A, Ay B, Sieck GC, Pabelick CM. Store‐operated Ca2+ influx in airway smooth muscle: interactions between volatile anesthetic and cyclic nucleotide effects. Anesthesiology. 2006;105(5):976‐983. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200611000-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Spalding MB, Ala‐Kokko TI. The use of inhaled sevoflurane for endotracheal intubation in epiglottitis. Anesthesiology. 1998;89(4):1025‐1026. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199810000-00029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen X, Yamakage M, Tsujiguchi N, Kamada Y, Namiki A. Interaction between volatile anesthetics and hypoxia in porcine tracheal smooth muscle. Anesth Analg. 2000;91(4):996‐1002. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200010000-00042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

None.