Abstract

The four genes pyrR, pyrP, pyrB, and carA were found to constitute an operon in Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis MG1363. The functions of the different genes were established by mutational analysis. The first gene in the operon is the pyrimidine regulatory gene, pyrR, which is responsible for the regulation of the expression of the pyrimidine biosynthetic genes leading to UMP formation. The second gene encodes a membrane-bound high-affinity uracil permease, required for utilization of exogenous uracil. The last two genes in the operon, pyrB and carA, encode pyrimidine biosynthetic enzymes; aspartate transcarbamoylase (pyrB) is the second enzyme in the pathway, whereas carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase subunit A (carA) is the small subunit of a heterodimeric enzyme, catalyzing the formation of carbamoyl phosphate. The carA gene product is shown to be required for both pyrimidine and arginine biosynthesis. The expression of the pyrimidine biosynthetic genes including the pyrRPB-carA operon is subject to control at the transcriptional level, most probably by an attenuator mechanism in which PyrR acts as the regulatory protein.

The de novo synthesis of pyrimidines is universal. The pathway consists of six enzymatic steps leading to the formation of UMP, which is further converted into UTP, CTP, dCTP, and dTTP. In order to coregulate expression, genes are often found to be organized in operons in procaryotes. The pyrimidine biosynthetic genes (pyr genes) have been found to constitute a single operon in a number of different gram-positive organisms including Bacillus subtilis (37), Bacillus caldolyticus (13), Enterococcus faecalis (23), and Lactobacillus plantarum (9). In addition a pyrimidine biosynthetic operon is found in Mycobacterium tuberculosis (6). The pyrimidine metabolism in Lactococcus lactis has been studied for a number of years. Surprisingly it was found that the pyr genes of L. lactis are scattered on the chromosome in small operons, the pyrKDbF operon (2), the carB gene (35), the pyrEC operon (5), and the pyrDa gene (1). This paper describes the genomic organization of the pyrimidine biosynthetic genes of L. lactis, since we demonstrate the presence of an operon including pyrB, encoding aspartate transcarbamoylase, and carA, encoding the small subunit of the carbamoyl-phosphate (CP) synthetase (CPSase). Moreover, the operon includes pyrR, the regulatory gene controlling expression of the pyr genes, and pyrP, encoding the uracil transporter.

Regulation of the expression of the pyr genes of L. lactis has not been subject to a detailed analysis. It has, however, been shown that the transcription of the carB gene is repressed by addition of uracil to the growth medium (35). Moreover, in front of both the carB gene (35) and the pyrKDbF operon (2) a putative attenuator similar to those found in B. subtilis (41) can be identified. These findings suggest that the expression of the pyr genes of L. lactis is regulated by the same attenuator mechanism as that suggested for B. subtilis (41). An RNA binding protein, PyrR, mediates the regulation of the expression of the pyr operon in B. subtilis by stabilizing the formation of a transcriptional terminator in the mRNA leader sequence. The binding of PyrR to the mRNA is dependent on the formation of a PyrR-UMP complex. In the absence of a PyrR-UMP complex, an antiterminator structure is preferentially formed (25). In the work presented here, the presence of a protein with a high degree of homology to the PyrR of B. subtilis and responsible for repressing expression of the pyrimidine biosynthetic enzymes by exogenous pyrimidines is documented.

The first step in the pyrimidine biosynthetic pathway is the formation of CP utilizing CO2, ATP, and glutamine. CP is also a precursor for the biosynthesis of arginine. The formation of CP is catalyzed by CPSase. This enzyme consists of a small subunit and a large subunit. The small subunit of the enzyme functions as a glutamine amidotransferase, whereas the other catalytic properties are found in the large subunit. In all procaryotes described so far, two genes, commonly called carA and carB, encode the CPSase. Procaryotes may contain either a single CPSase encoded by a single set of genes responsible for all CP synthesized or, alternatively, two different sets of CPSase-encoding genes (8). The two sets differ in their regulatory features; the level of pyrimidines in the cell regulates the expression of one set of genes, whereas the other responds to changes in arginine concentration (8). The genes encoding the two subunits have been sequenced for many procaryotes and are almost exclusively transcribed as an operon in the order carA-carB. Previously we have been able to show that the carB gene in L. lactis is transcribed as a monocistronic message and that the carA gene is not in the immediate proximity of carB (35). This finding was confirmed by the publication of the gene map of another L. lactis strain, showing that the carA and carB genes are separated by approximately 240 kb (5). In this work we show that the carA gene is part of an operon including other genes involved in pyrimidine metabolism and regulation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth conditions.

Lactococcal cultures were grown either on M17 glucose broth (39) or on synthetic media based on MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid) and containing seven vitamins and either 19 (SA) or 8 (BIV) amino acids (19) supplied with 1% glucose. Escherichia coli cultures were grown on Luria-Bertani broth. L. lactis was cultured at 30°C in filled culture flasks without aeration. E. coli in batch cultures was grown at 37°C with vigorous shaking. For all plates, agar was added to 15 g/liter. When needed, the following compounds were added to the different media: arginine at 200 μg/ml, uracil at 20 or 200 μg/ml, uridine at 40 μg/ml, erythromycin at 1 μg/ml for lactococci and 150 μg/ml for E. coli, and ampicillin at 100 μg/ml. In order to assay for growth on pyrimidines and sensitivity to the toxic analogue 5-fluorouracil, cells were plated on minimal medium containing pyrimidine or the analogue at different concentrations. After incubation at 30°C, the colony sizes were estimated on an arbitrary scale from 0.1 to 1, where the size of the largest colony was set to 1.

Transformation, DNA isolation, manipulations, and sequencing.

L. lactis was transformed by electroporation (17). E. coli cells were transformed as described previously (38). Chromosomal lactococcal DNA was prepared as described by Johansen and Kibenich (20). The methods described by Sambrook et al. (38) were used for general DNA methods in vitro. DNA sequences were determined from plasmid DNA by the dideoxy chain termination method using the Thermo Sequenase radiolabeled terminator cycle sequencing kit (product no. US 79750) from Amersham in accordance with the protocol of the manufacturer.

Southern blot analysis.

Southern blot analysis was performed with GeneScreen nylon membranes (New England Nuclear) and the DIG system (Boehringer Mannheim) for colorimetric detection of hybridized products in accordance with the protocols of the manufacturers.

PCR amplification of DNA.

L. lactis chromosomal DNA was amplified by PCR with 1 μg of DNA in a final volume of 100 μl containing deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates (0.25 mM each), oligonucleotides (10 μM), and 2.5 U of AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer). Amplification was performed in one of the following two ways: (i) standard PCR, 30 cycles at 94°C for 1 min and 55°C for 1 min, followed by 3 min at 72°C; easy gene walking, 25 cycles at 94°C for 1 min, and 55°C for 1 min, followed by 3 min at 72°C (10 min for the last cycle).

pGhost9::ISS1 transposon mutagenesis and selection for pyrimidine auxotrophs.

A pool of L. lactis strain MG1363 pGh9::ISS1 transposition mutants was obtained as previously described (21). After resuspension of the mutant library in SA medium supplemented with glucose and erythromycin but without pyrimidine addition, the cells were grown at 37°C for 30 min to stop the growth of auxotrophs. Then the culture was diluted 100-fold in the same medium, reaching an optical density at 450 nm (OD450) of 0.8, and grown for one additional hour. Ampicillin counterselection for the auxotrophs was performed overnight at 37°C, after addition of ampicillin at 100 μg/ml to the diluted culture. After the washing and resuspension of the cells in 0.9% NaCl solution, aliquots of a 100-μl culture, both undiluted and 10-fold diluted, were plated on SA-glucose medium containing uracil. After incubation at 37°C overnight, colonies were screened for a pyrimidine requirement on SA-glucose medium with and without uracil. Pyrimidine-requiring strain MB400 was chosen for further analysis.

Plasmid rescue.

Chromosomal DNA was extracted from MB400 and digested with SpeI. Following ligation and transformation of E. coli strain DH5α an erythromycin-resistant transformant was obtained. This strain was shown to harbor plasmid pJS50.

Construction of plasmids and strains.

The strains and plasmids used in this study are shown in Table 1. The primers used for plasmid constructions are shown in Table 2 and the relevant genetic maps of strains and plasmids are presented in Fig. 1. Plasmid pAM111 was obtained in the following way. With primers PyrR-Nterm and PyrR_CTny and L. lactis MG1363 chromosomal DNA as the template a PCR fragment was obtained. Subsequently, the PCR fragment and pRC1 were digsted with XhoI and PstI, mixed, ligated, and transformed into DH5α. Plasmid pAM122 was constructed in exactly the same way using primers PyrB-Nterm and PyrB-Cterm. By the same strategy, plasmid pAM117 was constructed using primers PyrR_4F and PyrB_14R and restriction enzymes HindIII and EcoRI. Strains MB411, MB417, and MB422 were constructed by transformations of MG1363 with nonreplicative plasmids pAM111, pAM117, and pAM122, respectively. Integrants were isolated on M17 plates supplied with glucose and 1 μg of erythromycin/ml and confirmed by PCR analysis of their chromosomal DNA.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this work

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or construction | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | F80lacZDM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 recA1 endA1 hsdR17 supE44 thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 | Laboratory strain |

| SØ990 | pyrB | |

| BM604 | HfrH thi galE Δ(attλ-bio) deoA103 deoC argA cytR upp udp pyrF30 | 3 |

| L. lactis | ||

| MG1363 | Plasmid-free strain | 10 |

| PSA001 | MG1363 pyrF Emr; uracil requirement | 2 |

| MB36 | MG1363 carB::lacLM (carB Emr); arginine requirement; partial uracil requirement | 35 |

| MB400 | MG1363 pyrB::pG+host9::ISS1 (pyrB Emr); uracil requirement | This study |

| MB401 | MB36 pyrR::pG+host8::ISS1 (pyrR Emr Tetr); partial uracil requirement | This study |

| MB411 | MG1363 pyrR::pAM111 (pyrP pyrB carA Emr); arginine requirement; partial uridine requirement | This study |

| MB417 | MG1363 pyrP::pAM117 (pyrP pyrB carA Emr); arginine requirement; partial uridine requirement | This study |

| MB422 | MG1363 pyrB::pAM122 (carA Emr); arginine requirement; partial uracil requirement | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pRC1 | L. lactis integration vector | 22 |

| pG+host9::ISS1 | Orits used for ISS1 mutagenesis; Emr | 30 |

| pG+host8::ISS1 | Orits used for ISS1 mutagenesis; Tetr | 30 |

| pJS50 | SpeI rescue from MB400 | This study |

| pAM111 | pyrR open reading frame in pRC1; Emr | This study |

| pAM117 | Internal pyrP fragment in pRC1; Emr | This study |

| pAM122 | pyrB open reading frame in pRC1; Emr | This study |

TABLE 2.

Synthetic oligonucleotides used in PCR amplifications

| Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) | Usagea | Coordinateb |

|---|---|---|---|

| PyrR_Ctny | AAACTGCAGCTTAATCTTCACGTTTGATT | Cloning | 945 |

| PyrR_F4 | CCTTTAAGATTGTCCAGAGAG | RT-PCR | 248 |

| PyrR_F5 | GACGGACATCTTATTAATGG | RT-PCR | 369 |

| PyrRPintR | GTTGAGCCAAACATGG | RT-PCR | 1147 |

| CarA-R6 | GCTCTTGTATCTACACCA | RT-PCR | 3952 |

| PyrR-Nterm | AGCTCGAGAATGAAAGGAGCCCC | Cloning | 440 |

| PyrB-Nterm | AGCTCGAGGGTAAAGGAGACCTT | Cloning | 2603 |

| PyrB-Cterm | AAACTGCAGCTTACTTCGCTTTTTTTCC | Cloning | 3518 |

| PyrP_F2 | GACAGGGGATGGTTTAG | RT-PCR | 1927 |

| PyrR_4F | CAACTTAGAGTTTTAGGAG | Cloning | 1057 |

| PyrR_2R | CGGAATGGACGTGTATCC | EGW | 639 |

| PyrR_3R | AGTGATCCGTGTAATTGC | Primer ext., EGW, RT-PCR | 484 |

| PyrR_4R | CCAAAGAGAATGCAGGTAG | EGW, RT-PCR | 309 |

| PyrB_14R | CTCCACCAATAACTGGTG | Cloning | 2101 |

| PyrRB_3F | GGATACACGTCCATTCCG | RT-PCR | 657 |

| pyrB2 | CATATGCTCTTACGCGTG | RT-PCR | 3278 |

| pyrB_12R | CACCTTTACTGATTGAACTGGC | RT-PCR | 2846 |

| PyrRB_2F | GCATTCTCTTTGGAATGCAGC | RT-PCR | 336 |

| Prbind-1 | TCCAGAGAGGCTNGCAAG | PCR | 257 |

| PyrB11 | CACGCGTAAGAGCATATG | PCR | 3260 |

| EcoRI | NNNNNNNNNNGAATTC | EGW | |

| HindIII | NNNNNNNNNNAAGCTT | EGW | |

| Sau3AI | NNNNNNNNNNGATC | EGW |

The applications of the different primers used in this study. Cloning, obtaining L. lactis DNA used for construction of plasmids; RT-PCR, primers used in the RT-PCR experiments; EGW and PCR, primers used for obtaining DNA templates for sequencing; primer ext., primer used in the primer extension experiment.

The coordinates refer to the corresponding 3′ end of pyrRPB-carA database sequence AJ13262.

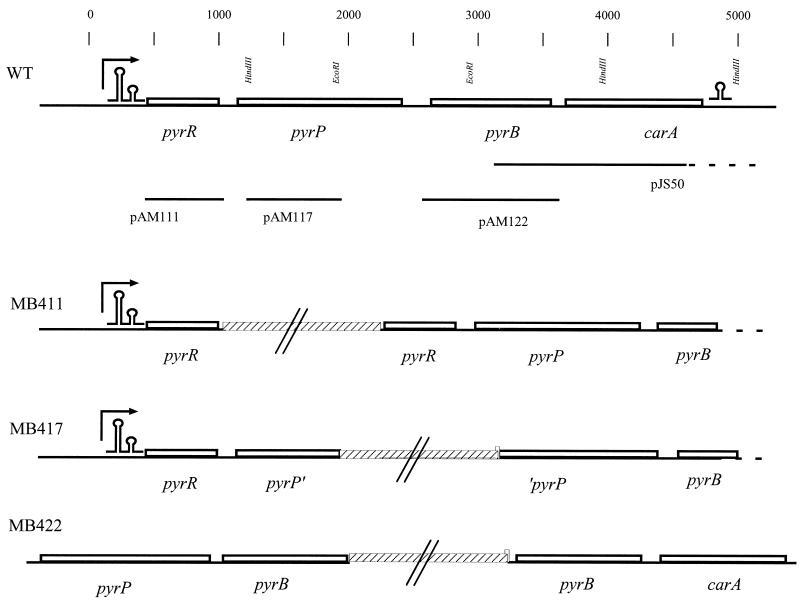

FIG. 1.

Genetic maps of the pyrRPB-carA region, the plasmids, and the strains used in this work. The physical map and the positions of selected restriction endonuclease sites are shown in the top line. The scale indicates numbers of base pairs in the sequenced region. Lines below the map show the L. lactis DNA contained in the different plasmids. The dotted line in pJS50 indicates that the cloned lactococcal DNA extends to a distal SpeI site beyond the sequenced DNA. Arrow, position of the promoter. The maps of the chromosomal DNA in the pyrRPB-carA regions of the wild-type (WT) strain, MB411, MB417, and MB422 are shown. Hatched bars, E. coli plasmid DNA (not drawn to scale); omega-like and double-omega-like structures, terminator and attenuator of the operon, respectively.

RNA extraction.

L. lactis RNA was harvested from strain MG1363 grown exponentially in SA-glucose medium to a cell density represented by an OD450 of approximately 0.8. Total RNA from a 20-ml culture was isolated according to the method of Arnau and coworkers (4).

Primer extension.

Synthetic oligonucleotide PyrR_3R, complementary to the sense strand, was radioactively labeled in the 5′ end using [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase and used for primer extensions on 20 μg of total RNA isolated from L. lactis strain MG1363 as previously described (11). The elongation was performed at 41°C using a SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (RT) (Gibco BRL).

RT-PCR.

L. lactis RNA was used as the template in the Titan one-tube RT-PCR system from Boehringer Mannheim in accordance with the protocols of the manufacturer.

Enzyme assays.

Exponentially growing cells were harvested at an OD450 of 0.8, washed, and resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HC1 (pH 7.0)–1 mM EDTA–1 mM dithiothreitol, resulting in a 100-fold concentration. The cells were lysed using a French pressure cell press at 18,000 lb/in2. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation, and the supernatant was used directly as the enzyme source in the assays. The protein concentration was determined as described by Lowry et al. (24). All assays were performed at 30°C using crude extracts with a final concentration of about 200 μg of protein/ml. Specific activities are expressed as milliunits per milligram of protein, and 1 mU is defined as 1nmol of product formed or substrate used per min.

(i) Aspartate transcarbamoylase (PyrB) activity.

PyrB activity was determined at pH 7.0 in the following way. Potassium aspartate (50 mM), potassium phosphate (25 mM), and enzyme extract were mixed and equilibrated at 30°C. The assay was started by addition of CP (3 mM). Aliquots (150 μl) were extracted between 0 and 20 min, and the formation of carbamoylaspartate was measured using the colorimetric procedure described by Prescott and Jones (36), in which 10−3 M carbamoylaspartate corresponds to an absorption of 18 at 560 nm.

(ii) Dihydroorotase (PyrC) activity.

PyrC activity was determined essentially as described for the aspartate transcarbamoylase (PyrB) assay with the following alterations. Potassium aspartate and potassium phosphate were replaced by Tris-HCl (100 mM)–EDTA (2 mM), and the assay was started by adding dihydroorotate (2 mM) instead of CP.

(iii) Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase A (PyrDa) activity.

PyrDa activity was determined by monitoring orotate formation in a spectrophotometer at 295 nm (ɛ = 3.67 × 103 M−1). The reaction mixture contained 0.1 M sodium phosphate (pH 7.0), 50 mM KCN, and 0.1 mM fumarate. After equilibration the assay was started by addition of dihydroorotate (0.1 mM).

(iv) Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase B (PyrDb) activity.

PyrDb activity was assayed by the same procedure as that used for dihydroorotate dehydrogenase A, except that fumarate was replaced by 0.1 mM NAD+.

(v) Orotate phosphoribosyltransferase (PyrE) activity.

PyrE activity was measured in a buffer at pH 7.5 containing Tris-HCl (20 mM), EDTA (2 mM), and orotate 300 μM. The reaction was monitored spectrophotometrically at 295 nm after addition of 5-phosphoribosyl-1-pyrophosphate (PRPP). A decrease in absorbancy of 3.67 is equivalent to an increase in OMP of 1 mM.

(vi) OMP decarboxylase (PyrF) activity.

PyrF activity was determined in a buffer (pH 7.5) containing 20 mM Tris-HCl and 2 mM EDTA. After calibration at 30°C, the reaction was initiated by the addition of 50 μM OMP. The activity was monitored in a spectrophotometer at 285 nm. A reduction of the OMP concentration by 1 mM corresponds to a decrease in absorbancy of 1.65.

β-Galactosidase.

For enzyme assays the cells were grown in SA- or BIV-glucose medium and aliquots were harvested at different times during exponential growth between OD450s of 0.2 and 0.8. The amount of β-galactosidase in the cells was assayed as previously described (18), but the cell density was measured at 450 nm. The specific enzymatic activity was determined as OD420/(OD450 per minute per milliliter of culture).

Preparation and analysis of protein extracts from E. coli.

E. coli cells were grown exponentially in Luria-Bertani broth exponentially in and, at an OD450 of 0.7, IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) was added, resulting in a final concentration of 1 mM. The cells were incubated at 37°C overnight. The 1-ml cell culture was harvested, washed, and resuspended in a 200-μl solution consisting of 0.5 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0). The proteins were extracted with 200 μl of phenol equilibrated with the buffer. The proteins were precipitated with 500 μl of ethanol and recovered by centrifugation. The protein pellets were resuspended in 100 μl of sodium dodecyl sulfate loading buffer and analyzed by 12.5% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis as previously described (38).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence reported in this paper has been submitted to the EMBL data library and assigned accession no. AJ132624.

RESULTS

Cloning and sequencing of the operon.

From a library of approximately 6,000 pGh9::ISS1 transposon mutants four pyrimidine auxotrophic mutants were obtained after ampicilin counterselection in medium without pyrimidines added. Marker rescue experiments were conducted in order to obtain the DNA regions flanking the pGh9::ISS1 insertions. Marker rescues from two of the strains resulted in plasmids with chromosomal inserts. The nucleotide sequence of the Lactococcus chromosomal DNA was determined. The DNA in one clone was found to be identical to the previously cloned and sequenced carB gene from L. lactis (35). The other plasmid obtained by an SpeI digestion was termed pJS50 and was shown to contain a 5-kb chromosomal fragment, including part of an open reading frame showing extensive homology to those encoding aspartate transcarbamoylases from a number of different organisms. Consequently, the gene was named pyrB. The ISS1 element was inserted in the middle of pyrB. Despite numerous attempts using different restriction endonucleases, only clones harboring DNA encoding the C-terminal part of PyrB were obtained.

In order to obtain the upstream sequences, we used a PCR strategy. A pyrB primer was used together with a PyrR binding site primer to amplify the upstream DNA. The rationale for doing this was as follows. By assaying the aspartate transcarbamoylase activity in wild-type cells grown in SA-glucose medium in the absence and presence of uracil, we were able to show that the expression of pyrB was repressed twofold by addition of uracil. This has previously been shown also to be the case for the carB gene (35) and the pyrKDbF operon (2) of L. lactis. In the leader sequences of these operons, PyrR binding sites very homologous to the PyrR binding sites in B. subtilis have been found. Therefore, a similar sequence could very well be present upstream of pyrB. Based on the PyrR binding sequences found in B. subtilis (14) and L. lactis (2, 35), the consensus PyrR binding site (5′-UCCAGAGAGGCUNGCAAG-3′) was proposed. A degenerate PyrR binding site primer (Prbind-1) was synthesized (Table 2) and used in a PCR experiment together with a pyrB-specific primer (PyrB11) and chromosomal DNA as the template. A 3-kb fragment was obtained and used as the template for sequencing reactions. By analyzing the sequence obtained, putative open reading frames with homology to those of the PyrB, PyrP, and PyrR proteins from B. subtilis could be identified.

Since the PyrR binding sites have been found exclusively in the mRNA leader, the promoter is not expected to be present on the PCR fragment. In order to obtain the upstream sequence, the easy gene walking method was used (16). This method is based on nested PCR. A set of three nested oligonucleotides (PyrR_4R, PyrR_3R, and PyrR_2R) was used together with partly degenerate oligonucleotides containing either an EcoRI, HindIII, or Sau3AI restriction site in the 3′ end of the primer (see Table 2 for the sequences of the oligonucleotides). Fragments covering the flanking DNA were obtained in combination with all three degenerate oligonucleotides. These PCR fragments were sequenced without prior cloning. This procedure eliminated errors caused by mutations in individual PCR fragments. The sequence data obtained in the different experiments were merged, resulting in a continuous 4.5-kb DNA sequence. Using a probe covering part of pyrB, a Southern blot experiment on ClaI-, HindIII-, and EcoRI-digested chromosomal DNA from L. lactis MG1363 showed that the DNA originated from L. lactis (data not shown).

The open reading frames in the operon.

On the 4.5-kb fragment, four open reading frames can be detected (Fig. 1 and Table 3). The Genemark program (29) predicts the identified open reading frames including ribosome binding sites as coding sequences. In order to assign a function to the open reading frames, Blast searches in protein databases were conducted. The first open reading frame showed homology to pyrimidine regulatory protein PyrR, first identified in B. subtilis (41). The second reading frame shows homology to that encoding uracil permease from a number of gram-positive organisms including B. subtilis (41). The third open reading frame was the already-identified PyrB gene, whereas the last one was homologous to carA, which encodes the small subunit of CPSase. The organization of the four open reading frames is shown in Fig. 1. In Table 3, the sizes, positions on the DNA, and translational initiation signals of the four open reading frames are presented. Moreover, the positions and sequences of the putative promoter and terminator are shown.

TABLE 3.

Sequence properties of the pyrRPB-carA region

| Genetic segment | No. of codons | Predicted mol wt | Nucleotide coordinatesb | Sequencea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pyrRPB-carA promoter | 191–227 | TTGACAAAGTTCTAAAACTTTGCTATAATCTATCTAA | ||

| PyrR binding site | TCCAGAGAGGCAGGCAAG | |||

| pyrR | 173 | 19,817 | 443–961 | AAGAATGAAAGGAGCCCCAAATG |

| pyrP | 430 | 45,232 | 1063–2352 | GAGTTATTTTAGGAGAAAAAGTG |

| pyrB | 310 | 34,567 | 2604–3533 | GTCAGGGTAAAGGAGAAAAAATG |

| carA | 357 | 39,647 | 3624–4694 | AAAGCAAAGTTTAAAGGAAATAATTATG |

| pyrRPB-carA terminator | 4763–4792 | AAAAAAAGAGCCTGTTTTATAGCAGGCTCTTTTTTAT |

The putative start codons are in boldface. Single underlining, nucleotides of the mRNA complementary to the 3′ end of the 16S rRNA from L. lactis (3′-UCUUUCCUCCA-5′); double underlining, inverted repeats in the putative terminator. The −10 and −35 sequences of the promoter and the first nucleotide in the corresponding mRNA are also in boldface.

The nucleotide numbers refers to the sequence submitted to the database.

The four open reading frames are transcribed as an operon.

In order to show whether the four open reading frames constitute an operon, two kinds of experiments were conducted. An RT-PCR experiment was used to define the size of the mRNA in vitro, whereas the phenotypes of strains constructed by gene disruption were used to define the transcriptional units in vivo.

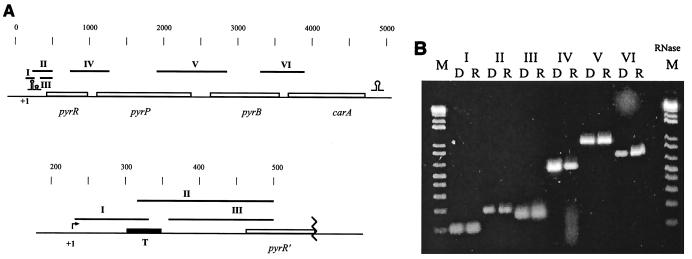

Total RNA was isolated from an exponentially growing culture of the wild-type L. lactis MG1363 and treated with DNase. RT-PCR experiments using primers covering the noncoding regions between the open reading frames were conducted. The positions of the primers and the expected PCR products are presented in Fig. 2A. In order to test whether any DNA is present in the samples resulting in false-positive signals, conventional PCR using the same primers and RNA preparation as the template was conducted. No products were observed (not shown). Moreover, in another experiment, the RNA sample was treated with RNase prior to amplification by RT-PCR. One example is shown in Fig. 2B. Only conventional PCR on chromosomal DNA and RT-PCR on RNA templates resulted in products (Fig. 2B). This result shows that the four open reading frames are present on the same message and suggests the presence of a promoter upstream of pyrR.

FIG. 2.

RT-PCR analysis of the transcription products of the pyrRPB-carA region. (A) Genetic map with the expected PCR products. Black box (T), putative terminator in the attenuator. Omega-like and double-omega-like structures are as defined for Fig. 1. (B) Agarose gel electrophoresis of the products obtained by the PCRs. Lanes R, results of the RT-PCR amplifications using RNA extracted from L. lactis; lanes D, standard PCRs with chromosomal DNA using the same primers. The following primers were used: I, PyrR_F4 and PyrR_4R; II, PyrRB_2F and PyrR_3R; III, PyrR_F5 and PyrR_3R; IV, PyrRB_3F and PyrRPintR; V, PyrP_F2 and PyrB_12R; VI, PyrB2 and CarA_R6. Marker (M), 100-bp DNA ladder; lane RNase, result of RT-PCR amplification with primers used in lanes VI after treatment of the RNA with RNase.

The presence of an operon structure was also demonstrated by data obtained from in vivo experiments. Plasmids conferring erythromycin resistance to the cell but unable to replicate in L. lactis carrying either the pyrR open reading frame without its promoter (pAM111) or an internal part of pyrP (pAM117) were transformed into L. lactis MG1363. By selecting for erythromycin resistance, strains in which the plasmids were integrated were readily obtained. The two strains were named MB411 and MB417, respectively (Fig. 1). If the genes are part of an operon, integration of the plasmids will disrupt transcription, thus resulting in polar mutations and no expression of pyrB. As expected the two mutants were found to have a uridine requirement. Thus, the finding obtained by RT-PCR, that pyrB is expressed by a promoter upstream of pyrR, was sustained by the uridine requirement of strains MB411 and MB417. Moreover, pyrB was shown to be unexpressed in these strains, since no aspartate transcarbamoylase activity could be detected in an enzyme assay performed using cell extracts obtained from strain MB411 or MB417.

Two determine whether carA is included in the operon, the growth requirements of strain MB422 were established. If carA is part of the operon, the integration of pAM122 would result in an operon disruption (Fig. 1), resulting in an arginine requirement (see below). In a growth experiment it was shown that arginine was required; thus the carA gene is no longer expressed in the mutant strains. In conclusion, the in vivo experiments confirm the existence of a four-gene operon with a promoter upstream of pyrR.

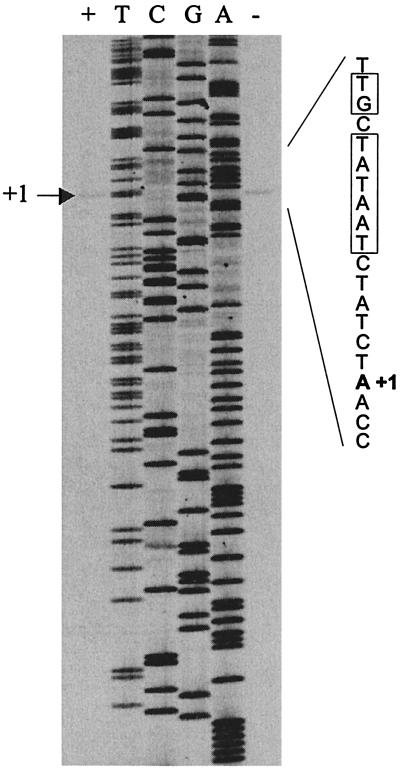

In order to map the precise location of the promoter, the 5′ end of the transcript was determined by a primer extension experiment using primer PyrR_3R labeled with 32P on RNA isolated from MG1363 grown in SA-glucose medium in the presence and absence of uracil. The result is presented in Fig. 3. A sequencing reaction with unlabeled PyrR_3R as the primer is included as a size marker. Since the extension product carries an additional charged phosphate compared to the product of the sequencing reaction, it migrates as if it was one nucleotide shorter. Hence, this experiment maps the first nucleotide to be transcribed (+1) to position 226 on the submitted sequence. This finding is supported by sequence analysis since a perfect consensus extended −10 sequence (TGCTATAAT) can be identified. In lactococcal promoters an extended −10 sequence is characterized by a TGN sequence adjacent to the −10 sequence (TATAAT) (42). Furthermore, spaced by 17 nucleotides upstream of the −10 sequence, a consensus −35 sequence (TTGACA) is present. Moreover, there seems to be more transcripts when the cells are grown in the absence of uracil. In order to quantify the amount of RNA, the radioactivity in each band was determined in an instant imager. A 2.9-fold increase in RNA was found when the cells was grown in the absence of RNA, suggesting that the expression of the operon is regulated at the level of transcription.

FIG. 3.

Primer extension mapping of the 5′ end of the pyrRPB-carA mRNA. Sequencing ladders generated with the oligonucleotide used for the primer extension were loaded next to the reaction mixture. The DNA sequence of the sense strand around the first nucleotide in the transcript (+1) is presented, and the −10 sequence is boxed. The experiment was conducted on RNA extracted from cells growing exponentially in the presence (+) and absence (−) of uracil at 200 μg/ml.

PyrR is the pyr regulatory protein.

As previously discussed, in front of all pyrimidine biosynthetic genes of L. lactis identified so far, except for pyrDa, a putative PyrR binding site identical to the PyrR boxes in B. subtilis has been found. Moreover, the pyr leaders of L. lactis can be folded in a manner similar to that found in B. subtilis forming alternative antiterminator or terminator structures, which suggests the presence of a transcriptional attenuator immediately in front of the structural genes. These findings strongly predict the presence of a PyrR homologue in L. lactis. Indeed, the PyrR open reading frame shows extensive homology to the PyrR open reading frame of B. subtilis. In order to identify the gene encoding the regulator of pyrimidine biosynthetic gene expression, the following experiment was conducted. Strain MB36 has a partial pyrimidine requirement due to a disruption of the carB gene by an integrative plasmid. Moreover, the truncated carB allele is fused to a promoterless lacLM gene encoding β-galactosidase. It was previously shown that the expression of β-galactosidase in this strain is repressed by the addition of uracil to the growth medium (35). Plasmid pG+host8::ISS1 is a transposon delivery vector conferring tetracycline resistance to the cell and is unable to replicate at 37°C (30). Strain MB36 was transformed with plasmid pG+host8::ISS1, and a transposon-induced mutant library comprising several thousand integrants was obtained. In a previous study, we were able to show that B. subtilis carrying a deletion of its pyrR allele is resistant to the toxic pyrimidine analog 5-fluorouracil at a concentration of 1 μg/ml (32). Therefore, strains were selected for growth in the presence of 5-fluorouracil and screened for high levels of β-galactosidase by plating on SA-glucose medium supplied with 5-fluorouracil (1 μg/ml) and 160 μg of X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside)/ml. Two independent mutants with the expected phenotype were isolated, and their chromosomal DNA was extracted. Attempts to amplify the pyrR gene by PCR was unsuccessful, suggesting that the integration takes place in the pyrR gene (not shown). Furthermore, the presence of an ISS1 element in the pyrR gene was clearly shown in a Southern blot experiment (not shown). One of the strains was selected for further analysis and named MB401.

Together with wild-type strain MG1363, MB401 was propagated in the defined SA-glucose medium in the presence and absence of uracil. The activities encoded by the different pyrimidine biosynthetic genes were assayed, and the results are presented in Table 4. The results clearly demonstrate that, upon addition of uracil, the expression of the different genes becomes repressed between two- and fourfold in a wild-type background. An exception is pyrDa, which is not regulated by exogenous uracil. On the other hand, the repression vanishes in a strain carrying the pyrR mutation. Moreover, the expression of the individual pyrimidine biosynthetic genes is generally enhanced. These findings suggest that pyrR is the general regulator of expression of the pyrimidine biosynthetic genes in L. lactis.

TABLE 4.

Specific activities of the pyrimidine de novo biosynthetic enzymes in the pyrR mutant compared to wild-type L. lactis

| Enzyme assayedc | Sp acta for strain (genotyped):

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MG1363 (wt) inb:

|

MB401 (pyrR::ISS1) in:

|

|||

| No | Uracil | No | Uracil | |

| PyrB | 38 | 19 | NDe | ND |

| PyrC | 26 | 11 | 53 | 67 |

| PyrDa | 22 | 17 | 25 | 20 |

| PyrDb | 36 | 18 | 50 | 44 |

| PyrE | 190 | 80 | 695 | 560 |

| PyrF | 77 | 36 | 203 | 201 |

Specific activity in crude extracts was determined as nanomoles/(minute · milligram of protein) at 30°C.

Cells were grown in defined medium in the absence (no) and presence (uracil) of uracil at a concentration of 200 μg/ml.

PyrB, aspartate transcarbamoylase; PyrC, dihydroorotase; PyrDa, dihydroorotate dehydrogenase A; PyrDb, dihydroorotate dehydrogenase B; PyrE, orotate phosphoribosyltransferase; PyrF, OMP decarboxylase.

wt, wild type.

ND, not determined.

The PyrR protein of B. subtilis has been shown to have the ability to catalyze the formation of UMP from uracil and PRPP, thus being a uracil phosphoribsyltransferase (UPRTase) as well as a regulatory protein. This activity did not seem to have physiological importance, since a true UPRTase encoded by upp was identified (32). To test whether the L. lactis PyrR protein has catalytic activity, plasmid pAM111 carrying the L. lactis pyrR gene expressed from an E. coli lac promoter was transformed into E. coli BM604 (upp pyrF). Transformants were tested on minimal medium in the presence of either uracil or uridine. As controls the previously cloned L. lactis upp gene (33) and vector pRC1 were included. The results showed that only the strain harboring the true upp gene is able to grow on uracil. Even after 7 days no growth on uracil of the strain harboring pyrR plasmid pAM111 was observed, showing that the L. lactis pyrR gene is unable to complement the upp defect and suggesting that the L. lactis PyrR protein does not contain a UPRTase activity. Crude extracts from E. coli BM604 cells harboring either vector pRC1 or pAM111 were prepared and analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. A distinct band corresponding to the expected size of the PyrR protein could be identified only in cells harboring pAM111 (data not shown).

The pyrP gene encodes a uracil transporter.

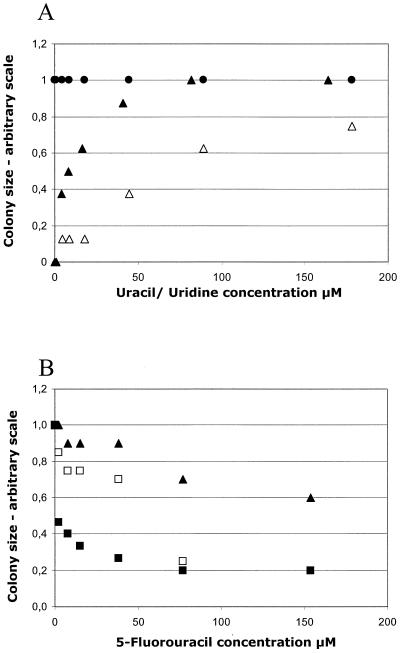

As previously stated PyrP shows extensive similarity to the uracil permease from B. subtilis, shown to be encoded by pyrP (41). To test whether pyrP from L. lactis encodes a uracil permease, strain MB417 (pyrP::pAM117) was tested on SA-glucose plates with increasing concentrations of uracil and uridine. This strain carries pyrP and has a pyrimidine requirement due to an interrupted transcription of the downstream genes, including pyrB. A wild-type strain and a strain carrying a mutated pyrF gene (PSA001) were included as controls. The results are presented in Fig. 4A, and it is clearly seen that a strain carrying a mutation in pyrP is unable to exploit uracil present at low concentrations, whereas no effect is seen at higher concentrations.

FIG. 4.

Growth dependence of an L. lactis pyrP mutant on different pyrimidine compounds. The growth was monitored by determining colony size after 40 h of incubation at 30°C on SA-glucose plates with the indicated additions. The size of the largest colonies was arbitrarily set to 1. (A) Growth of MB417 (pyrP pyrB) on uracil (▵) and uridine (▴). The pyrF mutant PSA001 gave the same result with uracil and uridine as MB417 with uridine. Wild-type strain MG1363 was included as a control (●). (B) Growth of MB417 on uridine (16.4 μM) and increasing concentrations of 5-fluorouracil (▴). As controls pyrF mutant PSA001 (■) and wild-type strain MG1363 (□) were included. All curves intercept the y axis at 1.0.

Pyrimidine analog 5-fluorouracil is toxic to L. lactis only after entering the cell and after metabolic conversion to phosphorylated derivatives (34). Therefore, strain MB417 was tested for its sensitivity to 5-fluorouracil. Uridine at a low concentration (16 μM) was used as the pyrimidine source in order to minimize competition between the drug and the required pyrimidine. As a control pyrimidine-requiring strain PSA001 (2) was used. At a concentration of 2 μM 5-fluorouracil strain PSA001 is clearly affected whereas only a concentration beyond 50 μM inhibited the growth of a strain carrying a defective pyrP allele (Fig. 4B). These findings define pyrP as the gene encoding the sole, high-affinity uracil transporter in L. lactis.

The pyrB allele of L. lactis MG1363 encodes a functional aspartate transcarbamoylase.

In order to show the functional properties of the protein, a complementation experiment was conducted. The pyrB open reading frame was amplified from the chromosome of L. lactis MG1363 and cloned into E. coli vector pRC1, thus creating pAM122. Plasmid DNA was propagated in an E. coli wild-type strain and transformed into pyrimidine-requiring E. coli strain SØ990, which carries a defective pyrB allele. Transformed strains carrying either pAM122 or vector pRC1 were screened for their ability to grow in the absence of uracil, and only strains harboring pAM122 were able to grow, thus demonstrating that the pyrB allele of L. lactis cloned in this work complements the pyrB defect of SØ990.

The carA gene encodes the small subunit of CPSase.

In a previous study it was concluded that, since no carA gene could be identified in the immediate proximity of the carB gene, it must be present somewhere else on the chromosome (35). Moreover it was shown that a carB mutation results in an arginine requirement, in accordance with CP being a precursor for both pyrimidine and arginine biosynthesis. In order to show that the carA gene actually encodes the small CPSase subunit, the ability of strain MB422 (carA) to grow in the absence of arginine was tested. Addition of arginine ensures the formation of CP for pyrimidine synthesis through the degradation of arginine by the arginine deiminase pathway (7). Together with MG1363 (wild type) and MB35 (carB), MB422 was plated on BIV-glucose plates without additional nutrients or BIV-glucose plates supplied with uracil, arginine, or uracil and arginine simultaneously. Strain MB422 had the same growth pattern as MB35, i.e., it requires arginine for growth, whereas uracil is unable to support growth of the strain. This finding suggests that carA is the sole gene encoding a functional small subunit in the CPSase of L. lactis.

DISCUSSION

Genetic organization of the pyrimidine biosynthetic genes.

The pyrimidine biosynthetic genes in L. lactis are scattered on the chromosome in at least five different transcriptional units. Four of these, pyrKDbF (2), pyrDa (1), carB (35), and pyrRPB-carA (this work), have been described, whereas it is presently unknown whether pyrC and pyrE are cotranscribed or are members of two different transcriptional units. The carB gene encoding the large subunit of CPSase is transcribed as a monocistronic message and does not have the same message as carA, as is normally found (35). This, in conjunction with the observation that L. lactis harbors two different pyrD alleles (1), makes L. lactis a unique organism with respect to the organization of the pyr genes.

L. lactis harbors only one carA gene.

The first step in the pyrimidine biosynthetic pathway is the formation of CP catalyzed by the CPSase complex comprising large and small subunits encoded by carB and carA, respectively. The small subunit is responsible for the binding of glutamine and the transfer of its amide nitrogen group to an ammonia binding site on the large subunit. The other activities in the formation of CP from ammonia, bicarbonate, and ATP are located on the large subunit (8). CP is not only used in the biosynthesis of pyrimidines but is also required for arginine biosynthesis. In a previous paper we presented evidence for the presence of only one CPSase activity in L. lactis, since a carB mutant required arginine for growth (35). In the work presented here, we were able to show that a carA mutant also acquired arginine, thus supporting the theory that only one CPSase is present in L. lactis.

The expression of the pyrRPB-carA operon is regulated by pyrimidines.

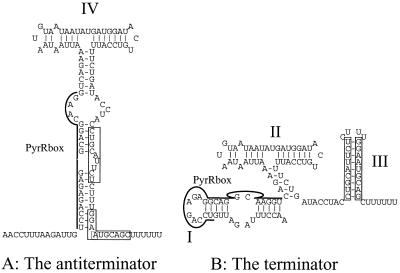

The presented data show that the pyrRPB-carA operon is regulated by the presence of uracil in the growth medium. At the enzymatic level aspartate transcarbamoylase (PyrB) is reduced twofold by the addition of uracil, whereas the mRNA level is repressed threefold as judged by primer extension. Note that the primer binds within the pyrR open reading frame. By analyzing the sequence of the mRNA leader a structure including a PyrR binding site similar to the one found in the pyrKDbF (2) and carB (35) leaders can be identified. The mechanism by which B. subtilis regulates its expression of the pyr operon by transcriptional attenuation through the PyrR regulatory protein has been studied in great detail (14, 15, 25–28). The structures that may be formed by the RNA in the carB and pyrKDbF leaders in L. lactis are similar to the structures found in the RNA transcribed from the B. subtilis pyr operon. Figure 5 shows the two mutually exclusive structures believed to result in antitermination (stem IV) or termination at stem III. Although the potential structures that may be formed by the pyrR leader are somewhat different from those found in the other pyr attenuators in L. lactis and B. subtilis, the functionality is preserved. A potential functional terminator (stem III) can be identified, and stem-loop structure I, including the PyrR binding site (Fig. 5), is highly homologous to a similar structure found in the B. subtilis pyr operon designated the antiantiterminator by Lu and coworkers (28).

FIG. 5.

Sequence of the pyrRPB-carB attenuator. Boxes, sequences constituting the stems of the terminator. (A) pyrRPB-carA antiterminator including stem IV. (B) Structure of the terminator. Stem III indicates the putative terminator. PyrRbox (stem I), putative PyrR binding site.

In this work we show that the uracil regulation of the L. lactis pyr genes is mediated by the PyrR protein encoded by the first open reading frame in the pyrRPB-carA operon. PyrR shows extensive homology to the PyrR protein from B. subtilis. Since PyrR binding sites identical to the ones found in B. subtilis (14) can be identified in the antiterminator structures of L. lactis, it is very likely that pyr gene expression is regulated by the same mechanism in L. lactis and B. subtilis.

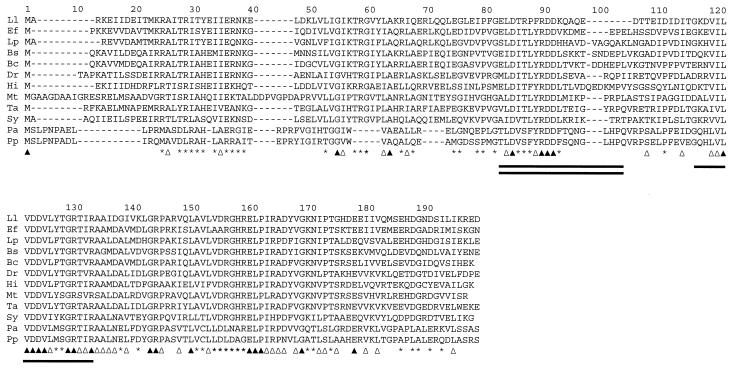

The PyrR protein of L. lactis does not possess UPRTase activity.

Unlike the finding for B. subtilis (32), the PyrR protein of L. lactis was shown not to encode UPRTase activity. The Blast search using the L. lactis PyrR amino acid sequence as the query revealed the presence of a class of proteins with a size of 170 to 193 amino acid residues with the highest similarity to PyrR from L. lactis. The different sequences are aligned in Fig. 6. The overall similarity among the different PyrR proteins is extended over the entire sequence, but especially the C-terminal part is highly conserved (Fig. 6). This part includes the binding site for PRPP. The most-pronounced deviation of the L. lactis PyrR sequence from those of the other PyrRs is the eight-amino-acid-residue deletion around amino acid residue 80 of the L. lactis PyrR sequence, corresponding to position 100 of the arbitrary scale in Fig. 6. The PyrR protein from E. faecalis has only a four-amino-acid-residue deletion at the same position (Fig. 6), and it has been shown that the PyrR protein from E. faecalis retains its catalytic activity (12). Moreover, the amino acid residues immediately before the 8-bp deletion (Fig. 6) are less conserved in the L. lactis pyrR. Assuming that the three-dimensional structure of PyrR from L. lactis is similar to that of PyrR from B. subtilis, this region is part of the “phosphoribosyltransferase flexible loop,” important for enzyme activity (40). Moreover, flexible-loop motif LDITLYRDD, which is fully conserved in B. subtilis, B. caldolyticus, and E. faecalis, in which the enzymatic activity is known to be retained, is changed in L. lactis to LDTRPFRDD. Whether this change accounts for the loss of enzyme activity remains to be solved.

FIG. 6.

Clustal W alignment of amino acid sequences deduced from pyrR homologues of L. lactis (Ll), E. faecalis (Ef), L. plantarum (Lp), B. subtilis (Bs), B. caldolyticus (Bc), Deinococcus radiodurans (Dr), Haemophilus influenzae (Hi), Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mt), Thermus aquaticus (Ta), Synechocystis sp. (Sy), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Pa), and Pseudomonas putida (Pp). The sequences were retrieved from protein databases after a Blast search using the search engine at the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Solid triangles, amino acid residues conserved in all sequences; open triangles, positions where only conservative substitutions have occurred; asterisks, positions where the amino acid residues are conserved in more than 66% of sequences; single line, putative binding site for PRPP; double line, flexible-loop domain.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Danish government program for food science and technology (FØTEK) through the Center for Advanced Food Studies.

We sincerely appreciate the expert technical assistance of Susan Outzen Jørgensen.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersen P S, Jansen P J, Hammer K. Two different dihydroorotate dehydrogenases in Lactococcus lactis. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3975–3982. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.13.3975-3982.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersen P S, Martinussen J, Hammer K. Sequence analysis and identification of the pyrKDbF operon from Lactococcus lactis including a novel gene, pyrK, involved in pyrimidine biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5005–5012. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.16.5005-5012.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersen P S, Smith J M, Mygind B. Characterization of the upp gene encoding uracil phosphoribosyltransferase of Escherichia coli K12. Eur J Biochem. 1992;204:51–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnau J, Sørensen K I, Appel K F, Vogensen F K, Hammer K. Analysis of heat shock gene expression in Lactococcus lactis MG1363. Microbiology. 1996;142:1685–1691. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-7-1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolotin A, Mauger S, Malarme K, Ehrlich S D, Sorokin A. Low-redundancy sequencing of the entire Lactococcus lactis IL1403 genome. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1999;76:27–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cole S T, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon S V, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry C E, Tekaia F, Badcock K, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingworth T, Connor R, Davies R, Devlin K, Feltwell T, Gentles S, Hamlin N, Holroyd S, Hornsby T, Jagels K, Barrell B G. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crow V L, Thomas T D. Arginine metabolism in lactic streptococci. J Bacteriol. 1982;150:1024–1032. doi: 10.1128/jb.150.3.1024-1032.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cunin R, Glansdorff N, Piérard A, Stalon V. Biosynthesis and metabolism of arginine in bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1986;50:314–352. doi: 10.1128/mr.50.3.314-352.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elagöz A, Abdi A, Hubert J C, Kammerer B. Structure and organisation of the pyrimidine biosynthesis pathway genes in Lactobacillus plantarum: a PCR strategy for sequencing without cloning. Gene. 1996;182:37–43. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00461-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gasson M J. Plasmid complements of Streptococcus lactis NCDO 712 and other lactic streptococci after protoplast-induced curing. J Bacteriol. 1983;154:1–9. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.1.1-9.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerdes K, Thisted T, Martinussen J. Mechanism of post-segregational killing by the hok/sok system of plasmid R1: sok antisense RNA regulates formation of a hok mRNA species correlated with killing of plasmid-free cells. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1807–1818. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb02029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghim S Y, Kim C C, Bonner E R, D'Elia J N, Grabner G K, Switzer R L. The Enterococcus faecalis pyr operon is regulated by autogenous transcriptional attenuation at a single site in the 5′ leader. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1324–1329. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.4.1324-1329.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghim S Y, Neuhard J. The pyrimidine biosynthesis operon of the thermophile Bacillus caldolyticus includes genes for uracil phosphoribosyltransferase and uracil permease. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3698–3707. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.12.3698-3707.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghim S Y, Switzer R L. Characterization of cis-acting mutations in the first attenuator region of the Bacillus subtilis pyr operon that are defective in pyrimidine-mediated regulation of expression. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2351–2355. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.8.2351-2355.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghim S Y, Switzer R L. Mutations in Bacillus subtilis PyrR, the pyr regulatory protein, with defects in regulation by pyrimidines. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;137:13–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harrison R W, Miller J C, D'Souza M J, Kampo G. Easy gene walking. BioTechniques. 1997;22:650–653. doi: 10.2144/97224bm17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holo H N I F. High-frequency transformation by electroporation of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris grown with glycine in osmotically stabilized media. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:3119–3123. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.12.3119-3123.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Israelsen H, Madsen S M, Vrang A, Hansen E B, Johansen E. Cloning and partial characterization of regulated promoters from Lactococcus lactis Tn917-lacZ integrants with the new promoter probe vector pAK80. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2540–2547. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.7.2540-2547.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jensen P R, Hammer K. Minimal requirements for exponential growth of Lactococcus lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:4363–4366. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.12.4363-4366.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johansen E, Kibenich A. Characterization of Leuconostoc isolates from commercial mixed strain mesophilic starter cultures. J Dairy Sci. 1992;75:1186–1191. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kilstrup M, Martinussen J. A transcriptional activator, homologous to the Bacillus subtilis PurR repressor, is required for expression of purine biosynthetic genes in Lactococcus lactis. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3907–3916. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.15.3907-3916.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Le Bourgeois P, Lautier M, Mata M, Ritzenthaler P. New tools for the physical and genetic mapping of Lactococcus strains. Gene. 1992;111:109–114. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90610-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li X, Weinstock G M, Murray B E. Generation of auxotrophic mutants of Enterococcus faecalis. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6866–6873. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.23.6866-6873.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lowry O H, Rosebrough N J, Farr A L, Randall R J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu Y, Switzer R L. Evidence that the Bacillus subtilis pyrimidine regulatory protein PyrR acts by binding to pyr mRNA at three sites in vivo. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5806–5809. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.19.5806-5809.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu Y, Switzer R L. Transcriptional attenuation of the Bacillus subtilis pyr operon by the PyrR regulatory protein and uridine nucleotides in vitro. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:7206–7211. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.24.7206-7211.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu Y, Turner R J, Switzer R L. Roles of the three transcriptional attenuators of the Bacillus subtilis pyrimidine biosynthetic operon in the regulation of its expression. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1315–1325. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.5.1315-1325.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu Y, Turner R J, Switzer R L. Function of RNA secondary structures in transcriptional attenuation of the Bacillus subtilis pyr operon. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14462–14467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lukashin A V, Borodovsky M. GeneMark.hmm: new solutions for gene finding. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:1107–1115. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.4.1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maguin E, Prévost H, Ehrlich S D, Gruss A. Efficient insertional mutagenesis in lactococci and other gram-positive bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:931–935. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.3.931-935.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martinussen J, Andersen P S, Hammer K. Nucleotide metabolism in Lactococcus lactis: salvage pathways of exogenous pyrimidines. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1514–1516. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.5.1514-1516.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martinussen J, Glaser P, Andersen P S, Saxild H H. Two genes encoding uracil phosphoribosyltransferase are present in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:271–274. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.1.271-274.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martinussen J, Hammer K. Cloning and characterization of upp, a gene encoding uracil phosphoribosyltransferase from Lactococcus lactis. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6457–6463. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.21.6457-6463.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martinussen J, Hammer K. Powerful methods to establish chromosomal markers in Lactococcus lactis: an analysis of pyrimidine salvage pathway mutants obtained by positive selections. Microbiology. 1995;141:1883–1890. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-8-1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martinussen J, Hammer K. The carB gene encoding the large subunit of carbamoylphosphate synthetase from Lactococcus lactis is transcribed monocistronically. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4380–4386. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4380-4386.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prescott L M, Jones M E. Modified methods for the determination of carbamyl aspartate. Anal Biochem. 1969;32:408–419. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(69)80008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quinn C L, Stephenson B T, Switzer R L. Functional organization and nucleotide sequence of the Bacillus subtilis pyrimidine biosynthetic operon. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:9113–9127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Terzaghi B E, Sandine W E. Improved medium for lactic streptococci and their bacteriophages. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1975;29:807–813. doi: 10.1128/am.29.6.807-813.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tomchick D R, Turner R J, Switzer R L, Smith J L. Adaptation of an enzyme to regulatory function: structure of Bacillus subtilis PyrR, a pyr RNA-binding attenuation protein and uracil phosphoribosyltransferase. Structure. 1998;6:337–350. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Turner R J, Lu Y, Switzer R L. Regulation of the Bacillus subtilis pyrimidine biosynthetic (pyr) gene cluster by an autogenous transcriptional attenuation mechanism. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3708–3722. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.12.3708-3722.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van de Guchte M, Kok J, Venema G. Gene expression in Lactococcus lactis. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1992;8:73–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb04958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]