Abstract

To improve the care of older adults with cancer, the traditional approach to clinical trial design needs to be reconsidered. Older adults are underrepresented in clinical trials with limited or no information on geriatric-specific factors, such as cognition or comorbidities. To address this knowledge gap and increase relevance of therapeutic clinical trial results to the real-life population, integration of aspects relevant to older adults is needed in oncology clinical trials. Geriatric assessment (GA) is a multidimensional tool comprising validated measures assessing specific health domains that are more frequently affected in older adults, including aspects related to physical function, comorbidity, medication use (polypharmacy), cognitive and psychological status, social support, and nutritional status. There are several mechanisms for incorporating either the full GA or specific GA measures into oncology therapeutic clinical trials to contribute to the overarching goal of the trial. Mechanisms include utilizing GA measures to better characterize the trial population, define trial eligibility, allocate treatment receipt within the context of the trial, develop predictive models for treatment outcomes, guide supportive care strategies, personalize care delivery, and assess longitudinal changes in GA domains. The objective of this manuscript is to review how GA measures can contribute to the overall goal of a clinical trial, to provide a framework to guide the selection and integration of GA measures into clinical trial design, and ultimately enable accrual of older adults to clinical trials by facilitating the design of trials tailored to older adults treated in clinical practice.

Treatment paradigms in oncology are continually evolving and driven by advances made through clinical trials. Over time, these advances have yielded significant improvements in clinical outcomes and treatment tolerability (1). However, progress has disproportionately been observed in younger patients, and older adult populations have derived less overall benefit (2). One reason for this disparity is that, historically, the populations enrolled in clinical trials do not reflect the actual populations affected with the disease, and generally, older adults are underrepresented in oncology clinical trials (3-5). This disparity creates a knowledge gap regarding the benefit and tolerability of treatments in older adults because results from younger, healthier populations cannot necessarily be extrapolated to older patients. Additionally, the aging process is heterogeneous; older adults of the same chronologic age may have different physiologic ages and varying degrees of other health issues, such as comorbidities, physical function, psychological health, cognitive function, and social support (6,7). Reporting solely the chronologic age of older trial participants does not describe their overall health status and does not allow clinicians to fully understand the characteristics of the older patients enrolled (8). In 2013, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) recognized these gaps and emphasized the need to improve the quality of care of older adults with cancer. Specific recommendations were to 1) increase the representation of older adults in trials, particularly those who are frail or have other comorbidities; 2) expand the information gathered about the characteristics of older adults enrolled on trials (eg, comorbidities, physical and cognitive function); and 3) incorporate clinical trial endpoints important to older adults (eg, impact of treatment on physical and cognitive function) (9).

Clinical trial design must adopt novel tools and strategies to meet the IOM recommendations and close the evidence gap for older adults. Integration of geriatric assessment (GA) into oncology clinical trials represents such a strategy. GA can facilitate the collection of more detailed information of older trial participants’ characteristics and overall health status and plays a critical role in addressing the knowledge gaps previously identified (10). The GA is a compilation of validated tools that assesses multiple health domains, including functional status and physical function, comorbid conditions, polypharmacy, cognitive function, psychological status, social support, and nutritional status. GA detects vulnerabilities that are routinely missed by standard oncology assessments (11,12). Numerous studies have demonstrated the feasibility of integrating GA into oncology care (13–15) including cooperative group clinical trials (16). Importantly, growing evidence shows that vulnerabilities detected by GA measures predict chemotherapy toxicity across varied settings and tumor types (17–19) and survival in older adults with cancer (20). GA can guide management interventions targeting identified vulnerabilities thereby tailoring supportive care to enhance resilience (eg, implementing physical therapy for older patients with impaired physical function) (21). More recently, randomized trials have shown that integration of the GA with GA-guided management interventions into oncology care improves communication about aging-related concerns between older patients and their oncologists (22) and reduces severe chemotherapy toxicity (23,24). With the mounting evidence of GA benefit, national guidelines now recommend the use of GA in the care of older adults with cancer (6,7).

As GA is increasingly recommended for use in clinical practice (6), it is timely and imperative that GA measures are used in National Cancer Institute and industry-sponsored clinical trials. These measures can assist oncologists in determining if the populations studied are reflective of those seen in practice and can provide meaningful information on which subsets of older adults are more or less likely to experience treatment benefits or toxicity. GA tools are also critical for moving beyond using chronologic age to define fitness and to facilitate trial design that provides treatment and management strategies for vulnerable and frail patients who have largely been excluded from trial participation. Ultimately, inclusion of GA measures into clinical trials may facilitate further uptake of GA use in routine clinical practice, as oncologists would assess patients with GA measures to compare and match with clinical trial populations. Additionally, this may enable inclusion of GA variables into larger datasets, such as cancer registries, or real-world datasets such as CancerLinQ.

Successful integration of GA measures into oncology clinical trials requires thoughtful consideration of the overall goal of the trial and how inclusion of GA measures could contribute to that goal. This manuscript describes recommendations developed by members of the Study Design Working Group that participated in the National Cancer Institute Virtual Workshop conducted in April 2021, supported by the Cancer MoonshotSM Network for Direct Patient Engagement Implementation Team. The purpose of this manuscript is to outline a framework for investigators when they are considering how GA may contribute to a clinical trial and detail various approaches to integrating GA into the clinical trial design. The concepts presented apply broadly to therapeutic clinical trials including older adults and should be considered for NIH-sponsored as well as industry-funded trials.

Detailed Considerations When Integrating GA Into Oncology Clinical Trials

Consideration 1: How Can GA Measures Contribute to the Goal of the Clinical Trial?

There are several key ways that GA information can contribute to the overall goal of the clinical trial (Table 1).

Table 1.

Utilizing geriatric assessment (GA) measures in clinical trial design and how approaches may contribute to overarching trial goal

| Roles for GA measures | What is the goal? |

|---|---|

| Characterize the patient population (“Ideal Table 1” for clinical trial manuscripts) |

|

| Define eligibility |

|

| Predict treatment outcomes |

|

| Utilize GA as the intervention to personalize cancer treatment |

|

| Utilize GA as the intervention to guide supportive care |

|

| Utilize GA as the intervention to guide care delivery |

|

| Utilize GA as outcome measures |

|

Better characterize the patient population: When considering an older adult for a specific cancer treatment option, a clinician may refer to the published characteristics of enrolled participants. However, most clinical trials report only chronologic age and performance status (PS), despite substantial evidence that age and PS alone do not adequately describe the health status of older adults (17,18,25). A clear role for GA in clinical trials is to describe the health status at baseline for enrolled older participants (eg, cognitive function, psychological health, detailed comorbidities). This would allow clinicians to better compare the characteristics of trial participants to older patients who they are considering for a specific treatment regimen in clinical practice. For example, in the FOCUS2 study (26), a 2 x 2 randomized study assessing the benefit of dose-reduced chemotherapy in older adults with metastatic colorectal cancer deemed not fit for full-dose chemotherapy by their oncologists, investigators gathered GA measures after enrollment to better understand the characteristics of the patients deemed ineligible for standard chemotherapy and to conduct secondary analyses exploring correlation of GA measures with treatment overall utility

Define eligibility for the clinical trial: Defining eligibility criteria is critical to successful clinical trial design and interpretation of results. Though age is infrequently used to explicitly exclude older adults, other restrictive criteria, such as performance status, prior malignancy, or strict organ function criteria, have resulted in de facto exclusion of older adults with cancer. Recent efforts to “modernize” eligibility criteria are important to increase opportunities for enrollment of older patients (27–29). Beyond removing eligibility barriers, there is an increasing interest in defining fitness for clinical trials to move beyond reliance on age as a primary criterion (30). Fitness describes the overall health status of an older adult and can range from fit (excellent overall health status) to frail (poor overall health status with decreased physiologic reserve). It is important to recognize that although individuals are typically categorized on this spectrum (eg, fit, vulnerable, frail), the fitness–frailty construct is a continuum of varying degrees of vulnerability. Use of GA measures provides an evidence-based characterization of fitness to minimize age bias and facilitate the design of trials that avoid over- or undertreatment. For investigators aiming to target a specific population of older adults, integration of GA measures or a GA screening measure [eg, the Geriatric-8 (G8) (20)] could facilitate inclusion or exclusion of specific older adult groups. For example, if an investigator is aiming to test a de-escalated therapy option for frail older patients, GA measures could be included in the eligibility criteria to ensure that fit older adults are not enrolled. One example of this approach is the ongoing Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG)-American College of Radiology Imaging Network (ACRIN) GIANT trial (EA2186; NCT04233866), where 2 modified and/or dose-reduced treatment options are being evaluated in older adults with metastatic pancreatic cancer deemed vulnerable. Hence, investigators chose a validated screening GA to exclude both fit and frail patients and only include older adults who met their screening GA definition of vulnerable. Utilizing GA-guided eligibility criteria to design trials for fit, vulnerable, and frail older adults will increase opportunities for clinical trial accrual

Utilize GA measures to predict treatment outcomes: Capture of GA variables at baseline can help identify characteristics related to treatment outcomes (eg,, treatment toxicity) or survival outcomes based on more detailed patient aspects captured by the GA. Multiple prior studies in geriatric oncology have sought to characterize baseline variables, including GA measures, that are predictive of treatment-related toxicity (17,18) and overall survival (31). In many of these models, information from the GA improves outcome prediction as compared with more traditional methods, such as use of chronologic age and/or PS alone. Clinical implications include the development of indices that can be used in practice to guide treatment such as the simplified GA for older adults with diffuse large cell lymphoma (32), the chemotherapy toxicity prediction calculators (17,18,33), or recent data supporting the added value of geriatric measures to mortality prediction models in acute myeloid leukemia (34). Identification of subsets likely to experience greater toxicity or shorter survival can also guide interpretation of therapeutic trial data and adaptive trial design. Additionally, this information could contribute to a more detailed understanding of the mechanistic underpinnings of toxicity risk

Utilize GA as the intervention to personalize cancer treatment: Personalized medicine often refers to the selection of treatment regimens based on cancer-specific aspects. However, tailored treatment approaches could be developed based on patient-level characteristics of older adults. For example, the GA could be used within the construct of the clinical trial to define patient-level characteristics for treatment allocation, such as fit patients assigned to receive a more intensive regimen as compared with vulnerable or frail patients. One such example using GA in this manner was led by Corre and colleagues (35,36). In this study of patients aged 70 years and older with advanced lung cancer, patients were randomly assigned to GA intervention (treatment allocation based on GA results) or usual care (treatment based on PS and chronologic age alone). This study demonstrated that utilizing the GA to guide treatment allocation was a more appropriate method for selecting treatment as compared with the traditional method (age and PS) and reduced treatment toxicity without compromising survival (36).

Employ the GA to guide supportive care interventions: As described, the GA identifies vulnerabilities previously undetected by the oncology team (11,12), allowing clinicians to intervene on GA impairments to potentially optimize outcomes for older patients. Recent examples of this study design include the GAP-70 -Geriatric Assessment for Patients 70 years and Older (GAP70+) (24) and GAIN-Geriatric Assessment-Driven Intervention (GAIN) (23) trials, which demonstrated reduced chemotherapy-related toxicities in their GA-based intervention arms. These studies incorporated validated GA measures that are known to predict treatment toxicity and employed GA-guided management interventions targeting the identified vulnerabilities to decrease chemotherapy toxicity.

Utilize GA as an intervention to test risk-adapted care delivery strategies: In addition to adapting treatment to vulnerable or frail older adults, age-friendly care delivery interventions can be tested to improve outcomes for older adults. For example, older adults are at higher risk of complications during cancer treatment including health-care utilization. The risk of hospitalization during or after treatment is a particular concern with 20%-30% of older adults receiving chemotherapy at risk for hospitalization during therapy (17,24,37). Older adults with vulnerabilities or frailty are at particularly high risk. Utilizing geriatric measures to identify those at higher risk of poor outcomes can facilitate testing novel models of care, such as navigation, modified visit scheduling, novel methods for heightened symptom monitoring (eg, digital reporting), or enhanced supportive care strategies, to decrease the risk of hospitalization.

Utilize GA as an outcome measure: As described in the IOM report, there is a need for increased integration of clinical trial endpoints important to older adults (38). In addition to traditional clinical trial outcomes, many older adults also care about the maintenance of their independence, including preservation of physical and cognitive function. Integration of relevant GA variables at multiple time points longitudinally throughout a clinical trial would capture these types of endpoints as outcomes prioritized by many older adults, thus allowing clinicians to better counsel older patients regarding the risks related to loss of independence, cognitive decline, development of frailty characteristics, and other aspects important for older adults that may occur with cancer treatment (39). Additionally, grade 2 adverse events with clinical significance may also be more important in contributing to change in functional outcomes for older adults (eg, grade 2 neuropathy contributing to falls or loss of independence). The previously mentioned GIANT trial (NCT04233866) is also evaluating how treatment regimens impact these important GA aspects, thus investigators chose to also include repeat modified GA every 8 weeks throughout the trial.

Consideration 2: Which GA Measures Should We Include?

Selection of geriatric measures to include in clinical trials should match the study goal(s). Measure selection should consider validity and reliability, data to support use in the intended study population or setting, and measure performance characteristics. In general, use of established, validated measures is preferred, if available. This provides the opportunity to benefit from what is already known about the measure to enhance the likelihood that it will perform sufficiently to meet the study objective.

Types of geriatric measures vary widely and are fit for different purposes. In general, they range from a full GA [battery of tests including the 4 cardinal domains of function, comorbid or physical health, socio-environmental health, and psychological status; ie, Cancer and Aging Research Group [CARG] GA (17)], abbreviated or simplified sets of geriatric measures typically including 2-3 geriatric domains [ie, myeloma frailty index (40)], geriatric screening tools that typically include less than 15 questions that identify individuals at high risk for specific outcomes [ie, Vulnerable Elders Survey-13 (41), G8 (42), or CARG chemotherapy toxicity tool (17)], and single domain measures [ie, gait speed (43), activities of daily living, cognitive screen]. CARG has developed a summary list of GA measures that can be considered for use in clinical trials with referenced examples where available (CARG Measures Core; www.mycarg.org). Characterization of frailty may also be considered depending on the study goal. GA measures can be used to assist in the characterization of frailty, but there are distinct approaches to define frailty in geriatrics (44). The 2 most common approaches include a phenotypic method or deficit accumulation method. Fried’s phenotype model—which includes weight loss, poor grip strength, slow gait speed, low physical activity, and self-reported exhaustion—has been used in multiple oncology settings (45). A deficit accumulation frailty index is a summary measure of vulnerability that can characterize populations as nonfrail (robust), prefrail, and frail by quantifying age-related deficits in health (ie, clinical signs, symptoms, diseases, lab abnormalities, health behaviors) as a proportion of the total number measured. This approach, often referred to as the Rockwood model, typically evaluates 30 or more variables across varied health domains to calculate a robust frailty index (46). An advantage of this approach is that it does not prescribe the specific variables to be assessed, and the ratio of vulnerabilities to measured characteristics can be analyzed as categories (nonfrail robust, prefrail, and frail using standard thresholds) or on a continuum. A disadvantage of this approach is that it can be challenging to calculate in a clinical setting at the point of care. This approach has been applied using the CARG GA and is predictive of grade 3 or higher toxicity of chemotherapy (44). Both approaches have been tested in oncology populations and are predictive of clinical outcomes such as toxicity and survival (47,48). In the context of clinical trial design, each has advantages and disadvantages to be considered, including practical considerations such as resources required for data collection.

Examples of geriatric measures used for different purposes in clinical trials are highlighted in Table 2 (49-61). To achieve the goal of describing the patient population, a full GA battery may be optimal to highlight performance on multiple domains of function. Similarly, when developing predictive models in geriatric populations, use of a GA battery provides the opportunity to ensure that all relevant vulnerabilities are included. If the goal is to utilize geriatric measures to define eligibility for a trial, various strategies may be considered ranging from the use of geriatric screening tools such as the G8 or the use of core measures that define vulnerability or fitness in a given setting. Careful consideration should be given to the study population that is intended for the trial. For example, a trial testing an intensive therapeutic strategy that intends to enroll physically fit individuals might utilize an objective physical performance measure such as the short physical performance battery (62,63) to “rule in” eligible patients. The short physical performance battery reliably predicts outcomes for older adults with established impairment thresholds and is a more sensitive characterization of physical function than commonly used self-report surveys (64,65). By contrast, a study that intends to exclude physically frail older adults might utilize a self-report measure such as the basic activities of daily living. Finally, when considering the use of geriatric measures as outcomes, a measure should be chosen that is sensitive to change over the time frame planned.

Table 2.

Considerations for use of geriatric measures in clinical trials

| Role of GA measures in trial design | Rationale | Considerations | Study examples and resources | Strategies and measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characterize the patient population |

|

|

|

|

| Define eligibility: identify older patients who may be more vulnerable to adverse outcomes |

|

|

|

|

| GA measures as outcomes: include as a study aim to examine the effect of intervention on GA measures |

|

|

|

|

| Evaluate a GA-based model as an intervention | Two main ways that the GA is integrated into the trial design as an intervention:

|

|

||

| Examine relationships between aging-related conditions and tolerability of therapeutic strategies |

|

|

Cytotoxic therapy:

Surgery: Radiotherapy: |

Cancer and Aging Research Group; www.mycarg.org. ADLs = activities of daily living; CALGB = Cancer and Leukemia Group B; CARG = Cancer and Aging Research Group; CRASH = Chemotherapy Risk Assessment Scale for High-Age Patients; ECOG = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; EORTC QLQ = European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire; G8 = Geriatric 8; GA = geriatric assessment; HRQOL = health-related quality of life; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living; MPI = Multidimensional Prognostic Index; NCT = National Clinical Trial; PACE = preoperative assessment of cancer in the elderly; PRO = patient-reported outcome; PS = performance status; QOL = quality of life; SPPB = Short Physical Performance Battery; VES = Vulnerable Elders Survey.

Measure selection should also consider the disease setting. For example, prevalence estimates of impairment may differ using the same measure in a population of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer vs those being evaluated for adjuvant breast cancer therapy. Accordingly, the utility of measures may differ to achieve the same study goal. Further, the thresholds that predict outcomes may differ using the same measure based on the natural history of a given disease and the type of treatment planned. Where possible, using the existing literature evaluating geriatric measures in a specific disease or treatment setting can guide measure selection in trial design.

Finally, measure selection should also take into consideration the setting in which the study will be conducted. For example, studies planned to enroll patients from community sites or resource-limited settings may benefit from selection of validated measures that are time efficient and require limited training to administer. Consideration should be given to utility of measures across diverse patient populations.

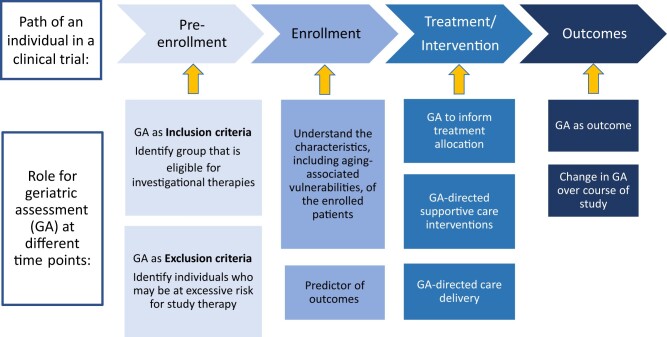

Consideration 3: At What Time Point(s) in the Trial Should Specific GA Measures Be Integrated?

Figure 1 highlights time points for measure integration into clinical trial design based on the intended use of the measures. It should be noted that GA measures may serve multiple roles in a single clinical trial although the individual measures chosen to achieve these roles may differ. The timing required for the collection of GA information may also inform the choice of a measure. For example, measures used for eligibility are obtained before trial enrollment. A focus on those used in usual care or those easier to implement into usual care will minimize barriers in screening. Measures used as outcomes during the course of the trial should match the opportunities for data collection and the research question. For example, evaluation of change in physical function at a specific single-time posttreatment may be suited to self-report and objective measures of strength and mobility obtained in an in-person study visit. Alternatively, assessing the trajectory of functional change during therapy may require repeated self-report measures collected virtually between study visits.

Figure 1.

Time points for integration of geriatric measures in clinical trial design

More broadly, there are opportunities to integrate GA into study design across the drug development and treatment continuum, though some approaches may be more appropriate in different phases.

In summary, the integration of GA measures into oncology clinical trial design is a key step to improving our knowledge base about treatment tolerability and efficacy for older adults with cancer and, ultimately, for expanding generalizability to real-world older adult populations. There are several approaches to consider in determining how the collection of GA measures will contribute to the overall goal of the trial. We have highlighted commonly used approaches, such as gathering GA information to better describe the study population, defining enrollment criteria, prescribing treatment allocation in the trial design, better understanding and predicting treatment outcomes such as treatment toxicity or survival, guiding supportive care interventions for identified GA impairments, personalizing care delivery, and assessing for longitudinal change in health status. These approaches are not exclusive, and several successful studies have incorporated GA measures in 2 or more of these described approaches, depending on the overall goal of the study. Depending on the approach used and the objective of the study, the complement of GA measures collected and time points of the collection will vary and should be thoughtfully considered to minimize participant burden while optimizing data collection to fully capture the heterogeneity of older trial participants.

Funding

This work was also supported in part by the National Institute of Health (NIH) National Institute on Aging (NIA) Beeson Career Development Award (K76 AG064394 to Magnuson, K76AG064431 to Wong), Sustainable Interdisciplinary Research Infrastructure to Address Challenges in Aging and Cancer NCI P30 Cancer Center Support Grant Supplement (3P30CA060553-26S2) (McKoy), NIA R33AG059206-03 (Klepin).

Notes

Role of the funder: Funding supported author time to contribute to the manuscript.

Disclosures: Dr Magnuson: None. Dr VanderWalde: Immediate family member is an employee of CARIS Life Sciences, Travel expenses: Alpha Tau Medical. Dr McKoy: None. Dr Wildes: Consulting: Carevive Systems, Sanofi; Janssen: Research Funding; Seattle Genetics: Advisory Board. Dr Wong: Immediate family member is an employee of Genentech with stock ownership. UpToDate contributor. Dr Le-Rademacher: None. Dr Little: None. Dr Klepin: UpToDate contributor.

Author contributions: Concept and design: A Magnuson, N VanderWalde, J McKoy, T Wildes, M Wong, J Le-Rademacher, R Little, H Klepin.

Prior presentations: Content presented in this manuscript was presented at the NCI Virtual Workshop Engaging Older Adults in the National Cancer Insitute Clinical Trials Network: Challenges and Opportunities, April 26-27, 2021, supported by the Cancer MoonshotSM Network for Direct Patient Engagement Implementation Team.

Contributor Information

Allison Magnuson, Department of Medicine, University of Rochester Medical Center, Wilmot Cancer Institute, Rochester, NY, USA.

Noam Van der Walde, Department of Radiation Oncology, West Cancer Center and Research Institute, University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Germantown, TN, USA.

June M McKoy, Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL, USA.

Tanya M Wildes, Division of Hematology and Oncology, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Nebraska Medicine, Omaha, NE, USA.

Melisa L Wong, Divisions of Hematology and Oncology and Geriatrics, Department of Internal Medicine, Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA.

Jennifer Le-Rademacher, Department of Quantitative Health Sciences, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA.

Richard F Little, Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Heidi D Klepin, Department of Medicine, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC, USA.

References

- 1. Flannery MA, Culakova E, Canin BE, Peppone L, Ramsdale E, Mohile SG. Understanding treatment tolerability in older adults with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(19):2150-2163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zeng C, Wen W, Morgans AK, Pao W, Shu X-O, Zheng W. Disparities by race, age, and sex in the improvement of survival for major cancers: results from the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program in the United States, 1990 to 2010. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(1):88-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Scher KS, Hurria A. Under-representation of older adults in cancer registration trials: known problem, little progress. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(17):2036-2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Talarico L, Chen G, Pazdur R. Enrollment of elderly patients in clinical trials for cancer drug registration: a 7-year experience by the US Food and Drug Administration. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(22):4626-4631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Singh H, Kanapuru B, Smith C, et al. FDA analysis of enrollment of older adults in clinical trials for cancer drug registration: a 10-year experience by the US Food and Drug Administration. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(suppl 15):10009–10009. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dotan E, Walter LC, Browner IS, et al. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Older Adult Oncology, Version 1.2021. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19(9):1006-1019. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2021.0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mohile SG, Dale W, Somerfield MR, et al. Practical assessment and management of vulnerabilities in older patients receiving chemotherapy: ASCO Guideline for Geriatric Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(22):2326-2347. doi: 10.1200/jco.2018.78.8687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McKoy JM, Samaras AT, Bennett CL. Providing cancer care to a graying and diverse cancer population in the 21st century: are we prepared? J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(17):2745-2746. doi:10.1200/J Clin Oncol.2009.22.4352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hurria A, Naylor M, Cohen HJ. Improving the quality of cancer care in an aging population: recommendations from an IOM report. JAMA. 2013;310(17):1795-1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hurria A, Levit LA, Dale W, et al. ; for the American Society of Clinical Oncology. Improving the evidence base for treating older adults with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology statement. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(32):3826-3833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hamaker M, Prins M, Stauder R. The relevance of geriatric assessments for elderly patients with a haematological malignancy—a systematic review. Leuk Res. 2014;38(3):275–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jolly TA, Deal AM, Nyrop KA, et al. Geriatric assessment‐identified deficits in older cancer patients with normal performance status. Oncologist. 2015;20(4):379-385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hurria A, Gupta S, Zauderer M, et al. Developing a cancer-specific geriatric assessment: a feasibility study. Cancer. 2005;104(9):1998-2005. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Williams GR, Deal AM, Jolly TA, et al. Feasibility of geriatric assessment in community oncology clinics. J Geriatr Oncol. 2014;5(3):245-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hurria A, Akiba C, Kim J, et al. Reliability, validity, and feasibility of a computer-based geriatric assessment for older adults with cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(12):e1025-e1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hurria A, Cirrincione CT, Muss HB, et al. Implementing a geriatric assessment in cooperative group clinical cancer trials: CALGB 360401. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(10):1290-1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hurria A, Togawa K, Mohile SG, et al. Predicting chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer: a prospective multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(25):3457-3465. doi: 10.1200/jco.2011.34.7625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Magnuson A, Sedrak MS, Gross CP, et al. Development and validation of a risk tool for predicting severe toxicity in older adults receiving chemotherapy for early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(6):608-618. doi:10.1200/J Clin Oncol.20.02063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hurria A, Mohile S, Gajra A, et al. Validation of a prediction tool for chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(20):2366-2371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. van Walree IC, Scheepers E, van Huis-Tanja L, et al. A systematic review on the association of the G8 with geriatric assessment, prognosis and course of treatment in older patients with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2019;10(6):847-858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mohile SG, Velarde C, Hurria A, et al. Geriatric assessment-guided care processes for older adults: a Delphi consensus of geriatric oncology experts. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015;13(9):1120-1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mohile SG, Epstein RM, Hurria A, et al. Communication with older patients with cancer using geriatric assessment: a cluster-randomized clinical trial from the National Cancer Institute community oncology research program. JAMA Oncol. 2019;6(2):196–204. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.4728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Li D, Sun C-L, Kim H, et al. Geriatric assessment-driven intervention (GAIN) on chemotherapy-related toxic effects in older adults with cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(11):e214158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mohile SG, Mohamed MR, Xu H, et al. Evaluation of geriatric assessment and management on the toxic effects of cancer treatment (GAP70+): a cluster-randomised study. Lancet. 2021;398(10314):1894-1904. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01789-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Repetto L, Fratino L, Audisio RA, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment adds information to Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status in elderly cancer patients: an Italian Group for Geriatric Oncology Study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(2):494-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Seymour MT, Thompson LC, Wasan HS, et al. ; for the National Cancer Research Institute Colorectal Cancer Clinical Studies Group. Chemotherapy options in elderly and frail patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (MRC FOCUS2): an open-label, randomised factorial trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9779):1749-1759. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60399-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lichtman SM, Harvey RD, Damiette Smit MA, et al. Modernizing clinical trial eligibility criteria: recommendations of the American Society of Clinical Oncology-Friends of Cancer Research organ dysfunction, prior or concurrent malignancy, and comorbidities working group. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(33):3753-3759. doi: 10.1200/jco.2017.74.4102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Magnuson A, Bruinooge SS, Singh H, et al. Modernizing clinical trial eligibility criteria: recommendations of the ASCO-Friends of Cancer research performance status work group. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(9):2424-2429. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-20-3868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kanesvaran R, Mohile S, Soto-Perez-de-Celis E, Singh H. The globalization of geriatric oncology: from data to practice. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2020;40:e107-e115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. DiNardo CD, Jonas BA, Pullarkat V, et al. Azacitidine and venetoclax in previously untreated acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(7):617-629. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2012971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hshieh TT, Jung WF, Grande LJ, et al. Prevalence of cognitive impairment and association with survival among older patients with hematologic cancers. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(5):686-693. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.5674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Merli F, Luminari S, Tucci A, et al. Simplified geriatric assessment in older patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: the prospective elderly project of the Fondazione Italiana Linfomi. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(11):1214-1222. doi: 10.1200/jco.20.02465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Extermann M, Boler I, Reich RR, et al. Predicting the risk of chemotherapy toxicity in older patients: the Chemotherapy Risk Assessment Scale for High-Age Patients (CRASH) score. Cancer. 2012;118(13):3377-3386. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Min GJ, Cho BS, Park SS, et al. Geriatric assessment predicts non-fatal toxicities and survival for intensively treated older adults with AML. Blood. 2022;139(11):1646-1658. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021013671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Corre R, Greillier L, Le CH, et al. Use of a comprehensive geriatric assessment for the management of elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: the phase III randomized ESOGIA-GFPC-GECP 08-02 study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(13):1476-1483. doi: 10.1200/jco.2015.63.5839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gajra A, Loh KP, Hurria A, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment-guided therapy does improve outcomes of older patients with advanced lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(33):4047-4048. doi:10.1200/J Clin Oncol.2016.67.5926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Klepin HD, Sun C-L, Smith DD, et al. Predictors of unplanned hospitalizations among older adults receiving cancer chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol Pract. 2021;17(6):e740-e752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wildiers H, Mauer M, Pallis A, et al. End points and trial design in geriatric oncology research: a joint European organisation for research and treatment of cancer—Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology—International Society of Geriatric Oncology position article. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(29):3711-3718. doi: 10.1200/jco.2013.49.6125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Klepin HD, Ritchie E, Major-Elechi B, et al. Geriatric assessment among older adults receiving intensive therapy for acute myeloid leukemia: report of CALGB 361006 (Alliance). J Geriatr Oncol. 2020;11(1):107-113. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2019.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Palumbo A, Bringhen S, Mateos MV, et al. Geriatric assessment predicts survival and toxicities in elderly myeloma patients: an International Myeloma Working Group report. Blood. 2015;125(13):2068-2074. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-12-615187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Saliba D, Elliott M, Rubenstein LZ, et al. The Vulnerable Elders Survey: a tool for identifying vulnerable older people in the community. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(12):1691-1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bellera C, Rainfray M, Mathoulin-Pelissier S, et al. Screening older cancer patients: first evaluation of the G-8 geriatric screening tool. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(8):2166-2172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Liu MA, DuMontier C, Murillo A, et al. Gait speed, grip strength and clinical outcomes in older patients with hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2019;134(4):374-382. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019000758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cohen HJ, Smith D, Sun CL, et al. ; for the Cancer and Aging Research Group. Frailty as determined by a comprehensive geriatric assessment-derived deficit-accumulation index in older patients with cancer who receive chemotherapy. Cancer. 2016;122(24):3865-3872. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. ; for the Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146-M156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rockwood K, Mitnitski A. Frailty in relation to the accumulation of deficits. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Medical Sci. 2007;62(7):722-727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ruiz J, Miller AA, Tooze JA, et al. Frailty assessment predicts toxicity during first cycle chemotherapy for advanced lung cancer regardless of chronologic age. J Geriatr Oncol. 2019;10(1):48-54. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2018.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Patel BG, Luo S, Wildes TM, Sanfilippo KM. Frailty in older adults with multiple myeloma: a study of US veterans. J Clin Oncol Clin Cancer Inform. 2020;4:117-127. doi: 10.1200/cci.19.00094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Woyach JA, Ruppert AS, Heerema NA, et al. Ibrutinib regimens versus chemoimmunotherapy in older patients with untreated CLL. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(26):2517-2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Boulahssass R, Chand M-E, Gal J, et al. Quality of life and Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) in older adults receiving accelerated partial breast irradiation (APBI) using a single fraction of multi-catheter interstitial high-dose rate brachytherapy (MIB). The SiFEBI phase I/II trial. J Geriatr Oncol. 2021;12(7):1085-1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Guigay J, Le Caer H, Mertens C, et al. Elderly Head and Neck Cancer (ELAN) study: personalized treatment according to geriatric assessment in patients age 70 or older: first prospective trials in patients with squamous cell cancer of the head and neck (SCCHN) unsuitable for surgery. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(suppl 15). doi: 10.1200/jco.2014.32.15_suppl.tps6099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Guigay J, Auperin A, Mertens C, et al. Personalized treatment according to geriatric assessment in first-line recurrent and/or metastatic (R/M) head and neck squamous cell cancer (HNSCC) patients aged 70 or over: ELAN (ELderly heAd and Neck cancer) FIT and UNFIT trials. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(suppl 5):v450. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Magnuson A, Dale W, Mohile S. Models of care in geriatric oncology. Curr Geriatr Rep. 2014;3(3):182-189. doi: 10.1007/s13670-014-0095-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Neve M, Jameson MB, Govender S, Hartopeanu C. Impact of geriatric assessment on the management of older adults with head and neck cancer: a pilot study. J Geriatr Oncol. 13 2016;7(6):457-462. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2016.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Guerard EJ, Deal AM, Chang Y, et al. Frailty index developed from a cancer-specific geriatric assessment and the association with mortality among older adults with cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15(7):894-902. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pata G, Bianchetti L, Rota M, et al. Multidimensional Prognostic Index (MPI) score has the major impact on outcome prediction in elderly surgical patients with colorectal cancer: the FRAGIS study. J Surg Oncol. 2021;123(2):667-675. doi: 10.1002/jso.26314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Audisio RA, Pope D, Ramesh HS, et al. ; for the PACE participants. Shall we operate? Preoperative assessment in elderly cancer patients (PACE) can help. A SIOG surgical task force prospective study. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;65(2):156-163. doi:S1040-8428(07)00232-6. [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. VanderWalde NA, Deal AM, Comitz E, et al. Geriatric assessment as a predictor of tolerance, quality of life, and outcomes in older patients with head and neck cancers and lung cancers receiving radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017;98(4):850-857. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Pottel L, Lycke M, Boterberg T, et al. Serial comprehensive geriatric assessment in elderly head and neck cancer patients undergoing curative radiotherapy identifies evolution of multidimensional health problems and is indicative of quality of life. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2014;23(3):401-412. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Pope D, Ramesh H, Gennari R, et al. Pre-operative assessment of cancer in the elderly (PACE): a comprehensive assessment of underlying characteristics of elderly cancer patients prior to elective surgery. Surg Oncol. 2006;15(4):189-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Brunello A, Fontana A, Zafferri V, et al. Development of an oncological-multidimensional prognostic index (Onco-MPI) for mortality prediction in older cancer patients. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2016;142(5):1069-1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Pieper CF, et al. Lower extremity function and subsequent disability: consistency across studies, predictive models, and value of gait speed alone compared with the short physical performance battery. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55(4):M221-M231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Klepin HD, Geiger AM, Tooze JA, et al. Geriatric assessment predicts survival for older adults receiving induction chemotherapy for acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2013;121(21):4287-4294. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-12-471680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Studenski S, Perera S, Wallace D, et al. Physical performance measures in the clinical setting. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(3):314-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Volpato S, Cavalieri M, Sioulis F, et al. Predictive value of the short physical performance battery following hospitalization in older patients. J Gerontol Ser A Biomed Sci Med Sci. 2011;66A(1):89-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]