Abstract

Social determinants of health are the economic and environmental conditions under which people are born, live, work, and age that affect health. These structural factors underlie many of the long-standing inequities in cancer care and outcomes that vary by geography, socioeconomic status, and race and ethnicity in the United States. Housing insecurity, including lack of safe, affordable, and stable housing, is a key social determinant of health that can influence—and be influenced by—cancer care across the continuum, from prevention to screening, diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship. During 2021, the National Cancer Policy Forum of the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine sponsored a series of webinars addressing social determinants of health, including food, housing, and transportation insecurity, and their associations with cancer care and patient outcomes. This dissemination commentary summarizes the formal presentations and panel discussions from the webinar devoted to housing insecurity. It provides an overview of housing insecurity and health care across the cancer control continuum, describes health system interventions to minimize the impact of housing insecurity on patients with cancer, and identifies challenges and opportunities for addressing housing insecurity and improving health equity. Systematically identifying and addressing housing insecurity to ensure equitable access to cancer care and reduce health disparities will require ongoing investment at the practice, systems, and broader policy levels.

Social determinants of health are the economic and environmental conditions under which people are born, live, work, and age that affect health, well-being, and quality of life (1). These structural factors underlie many of the long-standing inequities in health that vary by geography, socioeconomic status, and race and ethnicity in the United States (2). Housing is an important social determinant of health that can influence—and be influenced by—cancer across the continuum, from prevention and screening to diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship care (3-5).

Housing insecurity is an umbrella term that encompasses housing-related issues people may experience, such as high housing cost, lack of stable housing, frequent moves, poor living conditions, and unsafe neighborhoods (6-8). Although affordable housing in safe environments provides a foundation for lifelong health, such housing is in short supply (9). Across the United States, there is no state in which a full-time minimum wage job provides enough income for monthly rent payments for a 2-bedroom apartment (10), and fewer than one-quarter of eligible households receive federal rental subsidies to reduce rent payments. This unmet need for affordable housing has contributed to cost burdens in which 70% of low-income renters spend more than 30% of their income on rent (11). Lack of affordable housing may lead to housing instability, evictions, overcrowding, and even homelessness (12,13) and contributes to low-income families living in substandard housing in neighborhoods with conditions detrimental to health (13-18).

Furthermore, racially discriminatory housing policies and practices have created inequalities, such that the burden of the affordable housing crisis falls disproportionately on communities of color, especially Black communities (19). As one visible example, the federally sponsored Home Owners’ Loan Corporation produced maps in the 1930s to determine loan “worthiness” (20). Neighborhoods where Black households and other underrepresented minorities lived were labeled in red (ie, redlined), excluding them from traditional federally backed loans and contributing to inequalities in homeownership and wealth. Discriminatory housing policies and practices also resulted in serial displacement of Black renters and homeowners through urban renewal, the foreclosure crisis, and gentrification (21). These racially unequal housing barriers intersect with other forms of structural racism such as employment discrimination and mass incarceration to further limit housing access (22,23). The result is that housing affects population health equity (24), including equity in cancer care and outcomes (25,26).

During 2021, the National Cancer Policy Forum of the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine sponsored a series of webinars addressing key aspects of social determinants of health, including food, housing, and transportation insecurity, and cancer care (27). The overarching goals of the webinars were to summarize evidence related to social determinants of health and disparities in cancer care and patient outcomes, identify promising interventions, and highlight opportunities for research to inform policy and improve health equity. This commentary summarizes the formal presentations and discussions from the housing insecurity webinar. It provides an overview of housing insecurity and health care across the cancer control continuum and describes health system interventions to minimize the impact of housing insecurity on patients with cancer. The final section identifies challenges and opportunities for addressing housing insecurity and improving health equity.

Housing and Health Care Across the Cancer Control Continuum

The current literature identifies 4 broad pathways through which housing insecurity may impact health: 1) stability: not having a stable home (eg, homelessness or living outside or in shelters); 2) housing quality: poor housing conditions that affect health and safety (eg, pest infestation or residential overcrowding); 3) housing affordability: high housing costs relative to household income (eg, difficulties paying rent, mortgage, or utility bills); and 4) the neighborhood context (eg, access to parks or exposure to crime) (24,28). Evidence suggests complex relationships between housing and health over the life course within each of these 4 pathways.

This complexity may be even more pronounced for cancer care, where housing can have dynamic, bidirectional associations with access to cancer screening, diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship care. Bidirectional means that cancer and its treatment can affect different pathways of housing insecurity (eg, financial toxicity), and housing insecurity can affect receipt of cancer care and outcomes. For example, related to the first pathway of housing stability, lack of affordable housing is associated with more frequent moves, a higher risk of eviction, and higher risk of homelessness, each of which may lead to discontinuity and gaps in cancer-related medical care. In terms of housing quality, which refers to the physical condition and environment of a person’s home (29,30), individuals who are housing insecure may live in lower-quality housing that is associated with exposures such as radon, which contributes to excess cancer risk. Lack of affordable housing leaves fewer resources to spend for medical care. Furthermore, affordable housing is often limited in economically advantaged neighborhoods (31). Neighborhood context can shape health via its proximity to health systems and health-promoting resources, such as access to specialty health-care providers (32), recreational spaces (33), stores selling fresh food (34), and social capital (35,36), as well as distance from neighborhood environmental health threats (37,38). Individuals may commute longer distances to work in order to live in affordable housing, causing more transit time, lower exercise rates, and increased risk for sedentary lifestyles (39). Finally, across these 4 pathways, housing insecurity produces stress that may impede an individual’s ability to plan for the future (24), increase cancer risk behaviors [eg, smoking (40)], and reduce adherence to recommended cancer screening and treatment (41-43). Exposure to chronic stressors is associated with biological pathways that contribute to the development and progression of cancer (41–43).

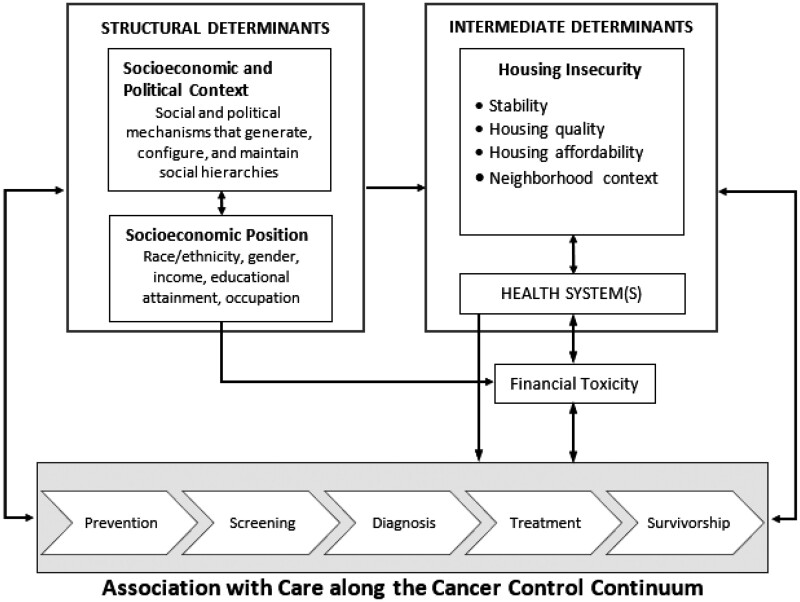

Emerging evidence suggests that housing insecurity is associated with cancer prevention and screening, diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship care (Figure 1). For example, in a large nationally representative sample of adults, housing insecurity was associated with lacking a usual source of care (45). Housing insecurity is adversely associated with cancer screening (3,46–50) and, among patients with cancer, receipt of timely treatment (51) and worse survival (52). Additionally, racially discriminatory housing policies are associated with adverse cancer outcomes, including more advanced-stage disease at diagnosis for some cancer sites (25,26). Housing insecurity adversely affected cancer survivorship care following the mortgage lending crisis of the Great Recession (December 2001 to July 2009) for some cancer sites. Breast cancer survivors who resided in high foreclosure–risk areas were more likely to report being in fair-poor health than women who lived in low foreclosure–risk areas (5). Older adults and women of color disproportionately lost their homes to foreclosure (53). Cancer mortality rates are also higher in areas with higher levels of mortgage denials and foreclosures (28,54,55).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of social determinants framework and cancer continuum [adapted from the World Health Organization Social Determinants of Health Framework (44)].

A cancer diagnosis and its management can also increase housing insecurity (as shown with bidirectional arrow in Figure 1). The financial toxicity of cancer treatment is well documented (56,57). For individuals diagnosed with cancer, medical care is characterized by resource intensive, often expensive, multimodal treatment that can have long-lasting consequences on overall well-being. Cancer is among the most expensive health conditions to treat, and cancer care costs continue to increase (58). Many patients with cancer face high out-of-pocket costs-associated medical care (eg, deductibles and co-payments and coinsurance associated with treatment) and nonmedical services (eg, transportation and lodging related to treatments) (59). Additionally, cancer patients and survivors frequently experience treatment side effects that can lead to physical and cognitive limitations impacting their ability to maintain employment, income, and employer-sponsored private health insurance coverage (60). Family members and other caregivers also face income loss and work disruptions because of caretaking (61). Medical and nonmedical financial hardships associated with cancer can negatively impact housing insecurity (62), including having to refinance homes, risking foreclosure or eviction to afford medical treatment, and moving in with family or friends to save money (63). These issues can be compounded for low-income households, without a financial cushion to absorb even small, unexpected expenses or income declines (64,65).

Health System Interventions to Minimize the Impact of Housing Insecurity on Patients With Cancer

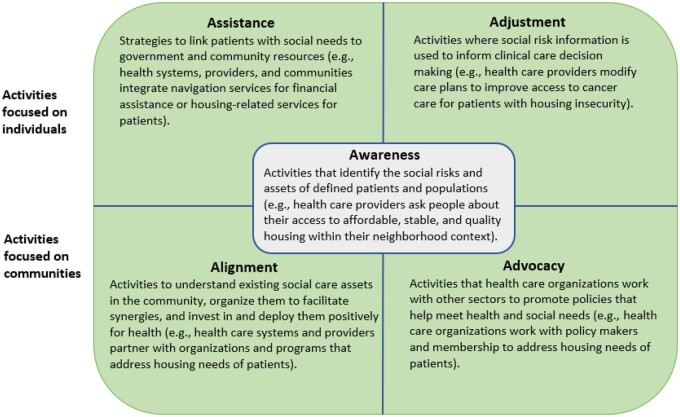

In 2019, the National Academies report “Integrating Social Care into the Delivery of Health Care to Improve the Nation’s Health” offered a 5-category framework for ways health-care stakeholders might better identify and intervene on patient and community-level social adversity to improve patient and population health (66) (Figure 2). The framework defines awareness as activities that identify social risks and patients’ priorities or needs related to those risks. It further identifies 4 types of interventions, 2 focused on the health-care delivery system (assistance and adjustment) and 2 directed toward health-care systems’ community engagement activities (alignment and advocacy). In the next sections, we discuss the 5 categories of activities that health systems can adopt to strengthen integration and provide detailed examples.

Figure 2.

Health-care system activities that strengthen social care integration [adapted from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Report Framework (66)].

Building Awareness of Housing Insecurity

Awareness refers to activities that identify social risks and assets of defined patients and populations (66). Despite growing recognition of the importance of identifying the social risk burden among patients with cancer, including those related to housing, systematic screening for these factors has not yet been broadly implemented within oncology care settings. Several studies have assessed related practices of financial hardship screening, and although they suggest widespread use (eg, 75% of participating institutions) (67,68), the content of these efforts varies widely, and they are rarely comprehensive. These studies highlight tools and approaches used to screen for financial hardship and suggest that similar efforts to screen for social risks within oncology settings would benefit from standardization of tools, guidelines, standardized data collection, mechanisms for sharing across sectors, and national standards for representing patients’ housing situation in electronic health record systems (Table 1). Furthermore, evidence that describes the practice-level resources and workflows is needed to support successful implementation of social risk screening programs (69).

Table 1.

Summary of challenges, opportunities, and recommendations for addressing housing insecurity

| Audience | Challenges | Opportunities and recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Providers and practices | Limited information about social resources (eg, housing insecurity) available in medical records | Routinely and consistently screen patients for housing insecurity and connect with community resources |

| Participate in payment models and demonstration projects addressing social determinants of health | ||

| Develop standard process for tracking referrals | ||

| Develop and maintain formal inventory of a community’s available resources to address housing insecurity available in real time | ||

| Cancer centers | Limited cross-sector partnerships | Require providers to routinely screen patients for social needs |

| Create stable partnerships with community-based safety net organizations | ||

| Develop medical–legal partnerships | ||

| Participate in payment models and demonstration projects addressing social determinants of health | ||

| Support policies that address health equity | ||

| Support equitable enrollment of patients with cancer in clinical trials | ||

| Develop standard process for tracking referrals | ||

| Develop and maintain formal inventory of a community’s available resources to address housing insecurity available in real time | ||

| Payors and health systems | Limited payor–provider partnerships | Increase collaboration and interoperability across payors and providers |

| Lack of stable funding stream | Develop sustainable models for identification of patient housing needs and referral process | |

| Create standards for the reimbursement of social risk screening and related services | ||

| Reduce the financial toxicity of cancer treatment, which increases risk of housing insecurity | ||

| Professional societies and guideline developers | Lack of consistent standard professional guidelines | Establish consistent definition and concepts around housing insecurity across all sectors including health systems, communities, and housing services |

| Challenges of implementation | Create standardized data collection, aggregation, and sharing mechanism | |

| Create national standards for representing data related to patients’ housing situation in electronic health record systems | ||

| Health policy and housing policy | Inadequate infrastructure to integrate information systems and rules and regulations | Strong leadership and commitment from key stakeholders to making the collaboration across housing and health-care providers |

| Lack of access to stable, high-quality, affordable housing in well-resourced neighborhoods | Promote policies that address funding limitations in health and housing programs at a structural level | |

| Promote housing policies to ensure adequate and affordable housing for patients with cancer | ||

| Research funders and researchers | Limited evidence about prevalence, correlates, and associations with cancer care and outcomes | Identify scope of housing insecurity and variation by geography and other characteristics |

| Lack of rigorous study design | Evaluate association between housing and cancer care across continuum and outcomes | |

| Limited data infrastructure; need additional support | Assess reciprocal relationship between cancer diagnosis and housing insecurity | |

| Identify best practices for screening and connecting patients with identified needs to services and resources | ||

| Conduct rigorous research to evaluate the effectiveness of health-care system strategies, payment models, housing interventions, and policies using evidence-based approach | ||

| Assess optimal balance of spending among treatment needs, addressing housing needs of patients, and addressing upstream social determinants of health |

As noted previously, housing insecurity can be dynamic and worsen as cancer treatment costs accumulate. As a result, screening for housing insecurity should be routine and well integrated into clinic workflows and electronic health records (70). Identifying existing and potential needs as early as the first visit increases the likelihood that patients living precariously are able to remain in care beyond that visit (70,71). When patients with housing needs are identified, referrals should be documented, as well as relevant information about if and how housing needs were addressed. Because cancer care adds complexity from primary care, including interaction between multiple types of specialty care providers for surgery, systemic treatment(s), and radiation therapy, ideally, patients’ information should be available across these multiple providers, who may practice in different networks. Interoperability across health-care payers remains a challenge, however.

In 2020, the Kaiser Permanente health system conducted a national survey of more than 10 000 of its members to assess the prevalence of social risks and acceptability of a social risk referral program. Although not specific to patients with cancer, approximately two-thirds of respondents had at least 1 social risk (44%), including financial strain, social isolation (35%), food insecurity (31%), housing instability (17%), and transportation needs (6%) (72). Most with a social risk also reported wanting help with that risk, including 59.8% of individuals with housing instability (73). Whereas Kaiser Permanente represents only 1 example of health system efforts, a growing body of evidence can inform other social risk programs within health-care settings. Similarly, the Oncology Care Model, introduced by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation in 2016 to improve care coordination and access to care for Medicare beneficiaries while controlling costs, encourages participating practices to screen for social needs, using a standardized assessment tool, as part of care planning and management (74).

Assistance and Adjustment to Address Housing-Related Needs

Beyond screening, patients with cancer need resources to address unmet housing needs and mitigate housing insecurity (eg, help paying mortgage and short-term rental assistance) and ensure receipt of optimal cancer care and management, including survivorship care. Activities that link patients with social needs to government and community resources are defined as assistance (66). A recent study sheds light on the current infrastructure within National Cancer Institute–designated cancer centers for navigation services designed to address social risks (75). Nearly all cancer centers surveyed reported having services to help patients apply for financial assistance with nonmedical costs (97%) such as transportation, housing, utility bills, and other expenses, and 68% reported providing direct financial assistance with these nonmedical costs. Accordingly, these programs serve as infrastructure that may be expanded, including enhanced training about issues and resources that are unique to cancer patients and development of workflows that streamline the coordination of social risk referrals alongside cancer care delivery.

Although not possible in all cancer care settings, having a care coordinator on the team allows social needs like housing insecurity to be identified and, ideally, addressed at the onset of care. Health systems and oncology practices vary in who on the team is able to effectively serve in this role and how the role is defined. Social workers, patient navigators, and others have been deployed to screen for and address identified patient needs (76). They also can identify emotional problems that come from social stressors like housing insecurity. Once problems are identified, oncology social workers and others can either intervene directly or link patients to community resources that can be monitored over the course of care. Because public and philanthropic resources fluctuate over time, remaining aware of resources and maintaining relationships with health service providers is critical.

Within oncology, there is historical precedence for use of patient navigation as an intervention model to help patients overcome barriers across the cancer care continuum, specifically, among vulnerable and underserved populations (77). Among the core activities of patient navigation models within oncology, 3 of the most important include identification of patient risk factors or barriers, provision of instrumental support (eg, helping a patient find transportation to a medical appointment), and relationship building that involves forming effective connections between patients and providers and, often, between interprofessional teams (78). The scope and goals of such navigation programs within oncology are highly variable, though, in part because of the heterogeneity in training and background of the individuals who serve as the navigator, including social workers, nurses, community health workers, health educators, and cancer survivors (77,78). Nonetheless, the extensive experience and evidence on the benefits of patient navigation within oncology has led to widespread recognition of its role in increasing health equity among patients with cancer and integration of this model into care standards. In particular, the American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer released standards that require all cancer programs seeking accreditation to have a patient navigation program (79). Although a large number of studies have evaluated the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of patient navigation in improving cancer outcomes, most focused on cancer screening and diagnosis (80). More research on other points along the continuum of cancer care is needed, such as ensuring timely and high-quality cancer treatment(s) and survivorship care.

Along with social workers and patient navigators, some clinical sites have worked with medical–legal partnerships (MLP) to support health equity for patients with cancer (81). The MLP model integrates doctors and lawyers who are cross-trained to mobilize resources. The inclusion of lawyers within the clinical setting can help patients address their legal needs such as identifying and addressing substandard housing conditions, negotiating payment with landlords to avoid eviction, or helping patients retain housing subsidies (82). Evidence suggests that MLPs can improve housing outcomes (82) and reduce patient stress, depression, and anxiety (83).

The process of awareness and assistance may also inform adjustments that alter clinical care to accommodate patients’ social contexts (66). Thus, social needs may be mitigated by changes in care delivery in addition to resolving the underlying social risk itself. As examples, patients experiencing homelessness should be offered medications that do not require refrigeration (84) or are not likely to increase urination; it may also be advisable to avoid prescribing any treatments requiring electricity (eg, infusion pumps) to patients living in a shelter where access to electricity may limit the possibility of treatment adherence. Another example is the Medical Respite Care program, which provides short-term residential care and medical care and other supportive services for individuals experiencing homelessness (85). However, there is limited evidence about how providers should adjust their care for cancer patients experiencing housing insecurity. Experimental studies with rigorous designs are needed, such as research focused on adjusted treatment plans for cancer patients experiencing housing needs.

Alignment and Advocacy to Address Housing Needs

Although clinical teams are able to screen for social needs and work to address those needs, they cannot meet these needs alone. Alignment with cross-sectoral community-based organizations, including safety-net organizations, to understand existing social care assets, facilitates synergies and invests in and deploys community-based organizations positively for health (66) is crucial for cancer centers. To date, however, most cancer centers have only limited cross-sector partnerships (Table 1). These partnerships often take time, trust, and resources to develop.

Health plans increasingly are piloting interventions to address social needs, including housing insecurity. Though not targeting oncology, the Accountable Health Communities model was launched by Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation in 2017 to evaluate whether connecting Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries to community resources could address social needs and improve health outcomes while reducing health-care utilization and costs. The model not only relies on awareness and assistance but also seeks to better align resources to meet beneficiary needs. Preliminary evaluation found that beneficiaries are amenable to screening and accept navigation; however, addressing and resolving social needs has been challenging, highlighting the importance of increasing alignment and investment in available resources (86,87).

In addition, multiple state Medicaid initiatives are ongoing. Most states are leveraging Medicaid-managed care to address social determinants of health, including screening for social needs, referrals, community partnerships, and employment of community health workers. States can obtain demonstration waivers to test the effects of changes in Medicaid eligibility, benefits and cost sharing, and payment and delivery systems. An increased number of health systems are engaging in collaborative work and investing in programs aimed at addressing the housing needs of people who are homeless or at risk of homelessness. For example, Kaiser Permanente is joining with national and local partners to support affordable housing programs by making impact investments and shaping public policy (88). Hospitals also made financial investments in housing capital costs directly. For instance, the Boston Medical Center is investing in affordable housing initiatives to reduce patients’ medical costs by addressing their homelessness and housing insecurity (89). Despite these efforts, millions of patients receiving cancer care do not have comprehensive health insurance coverage and are not able to benefit from these efforts. Nonetheless, as payment models and demonstration projects mature, understanding their effectiveness and sustainability from the perspective of practices and payers will be critical (90). To achieve these goals and address housing insecurity, providers and payers should take responsibility for creating and implementing more advanced payment models based on patients’ social risk. To find the best practices for implementation, rigorous research is needed to evaluate the effectiveness of the projects, payment models, and policies and inform evidence-based approaches.

Resolving unmet housing needs of patients with cancer also requires shaping policies and practices in nonhealth sectors in ways that promote health. Such strategies include increasing the availability of federal and state rental assistance for struggling households, improving neighborhood and living conditions, and providing employment opportunities and community development. Also, policy changes should address racial inequalities in housing security through enforcement of fair housing laws at the local, state, and federal levels and through desegregation efforts and zoning reforms (91). Advocacy occurs when health-care organizations work to promote policies that help meet health and social needs, often in partnership with other sectors and with the goal of optimizing community capacity to address health-related social needs (66).

Oncology professional societies and nonprofits, including but not limited to the American College of Surgeons, American Society for Clinical Oncology, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, and the American Cancer Society, have increased their support for addressing patients’ social needs as part of efforts to improve health equity. These organizations can play an important role in advocating to their members and constituents. For example, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network recently partnered with the National Minority Quality Forum to make policy recommendations to congress, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and commercial payors, and other federal agencies for improving health equity, which included reimbursement for patient navigation and community health workers. They also recommended that state governments expand Medicaid access to effective cancer screening, early detection, and treatment (92).

Challenges and Opportunities in Addressing Housing Insecurity and Improving Health Equity

As highlighted earlier and illustrated in Table 1, providers and practices, cancer centers, health systems, policy makers, and researchers have many challenges and opportunities in mitigating housing insecurity among patients with cancer.

The need for data infrastructure and interoperability across multiple sectors is central to these efforts. This need may be even more important for housing-focused community organizations, because many of these organizations have to use multiple platforms to document and report their services (93,94). Providers and practices can also face such challenges in social risk screening and referral. For example, many electronic health records systems have limited capability to document and track the delivery of social services (such as housing assistance), as well as the outcomes of social services referrals. Information technology systems should facilitate the tracking of referrals between organizations (ie, closed-loop referrals) and improve care coordination. Other issues include how best to meaningfully engage community organizations in strong partnerships and ensure that integrated social risk programs do not duplicate or complicate existing services—for example, if healthcare staff are unfamiliar with the social services organizations in their communities and may lack up-to-date information about community resources. Standardized screening tools are increasingly used in primary care delivery; adaptation and enhancement for cancer care are needed (95).

Although National Cancer Institute–designated cancer centers report having assistance-related resources and processes within their institutions, other cancer care delivery settings may face more limited infrastructure. Strong resource investment and capacity building and development of sustainable integrated social care between oncology and community organizations will foster provision of resources throughout partnerships. Although providers, cancer centers, and health systems have engaged in partnership payment models and collaborative projects that leverage existing resources in the community, it is also essential for public and private payers to develop standards for the reimbursement of social risk screening and other related activities that occur within health-care delivery. Collaborations will benefit from the development of evidence-based guidelines, standardized data collection, aggregation, and sharing across sectors. Moreover, the standardized application of screening tools as a part of clinical routines allows provider teams to quickly and consistently identify possible housing needs for further intervention.

At the institution level, health system leadership and sustained policy efforts are crucial for driving system structural changes in health and housing programs, including housing policies to ensure adequate and affordable housing for patients with cancer, especially for low-income patients, and health policies to improve extensive and equitable cancer care access and advance cancer health equity.

Rigorous research and research funding are needed to provide comprehensive information about the scope of housing insecurity; its impact on access, quality, and cost of cancer care; and its association with cancer outcomes and to inform best practices for screening patients for social needs and connecting them with services and relevant resources. Research is also critical for the evaluation of the effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and sustainability of health-care system strategies and payment models and other interventions designed to address patient social needs to inform their ongoing development (90). In addition, research evaluating the adjustment of treatment plans for cancer patients experiencing housing insecurity is also important in providing evidence and informing improvements for cancer care delivery.

Last, even with optimal screening processes, strong engagement with community resources, and deep institutional support, meeting the challenges of housing insecurity for patients with cancer will require broad structural changes designed to support access to high-quality, affordable housing and promote housing and health equity.

Social determinants of health influence human development, well-being, and quality of life. This commentary focused on an important social determinant of health, namely, housing insecurity and its relationship with cancer care and patient outcomes. We summarized existing evidence and described health system interventions to minimize the adverse effects of housing insecurity on patients with cancer. Systematically identifying and addressing housing insecurity and other social determinants of health to ensure equitable access to cancer care and reduce health disparities will require greater investment at the practice, systems, and broader policy levels.

Funding

No funding was used for this commentary.

Notes

Role of the funder: Not applicable.

Disclosures: KRY serves on the Flatiron Health Equity Advisory Board. The other authors have no disclosures. KRY, a JNCI Associate Editor and co-author on this commentary, had no role in the editorial review or decision to publish this manuscript.

Author contributions: QF, DK, MPB, SG, LMG, KRY, CEP: conceptualization; writing-original draft, writing-review & editing. KRY, CEP: project administration.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Dawn Alley, PhD; Karen Basen-Engquist, PhD, MPH; Cathy Bradley, PhD; Gwen Darien, BA; Chanita Hughes-Halbert, PhD, Lawrence Shulman, MD, MACP, FASCO; and Robert Winn, MD, for their contributions as speakers and planning group members for the National Cancer Policy Forum’s webinar on Housing Insecurity among Patients with Cancer. We are grateful for the support of the National Cancer Policy Forum staff team: Francis Amankwah, MPH; Rachel Austin, BA; Lori Benjamin Brenig, MPH; Erin Balogh, MPH; and Sharyl Nass, PhD.

The activities of the National Cancer Policy Forum are supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Cancer Institute and National Institutes of Health, the American Association for Cancer Research, the American Cancer Society, the American College of Radiology, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the Association of American Cancer Institutes, the Association of Community Cancer Centers, Bristol-Myers Squibb, the Cancer Support Community, the CEO Roundtable on Cancer, Flatiron Health, Merck, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, the National Patient Advocate Foundation, Novartis Oncology, the Oncology Nursing Society, Pfizer, Inc, Sanofi, and the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer.

Disclaimer: The authors are responsible for the content of this commentary, which does not necessarily represent the views of the American Cancer Society, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

Contributor Information

Qinjin Fan, Surveillance & Health Equity Science Department, American Cancer Society, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Danya E Keene, Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Yale School of Public Health, New Haven, CT, USA.

Matthew P Banegas, Department of Radiation Medicine and Applied Sciences, University of California, San Diego, CA, USA.

Sarah Gehlert, Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Laura M Gottlieb, Social Interventions Research and Evaluation Network, University of California, San Francisco, CA, USA.

K Robin Yabroff, Surveillance & Health Equity Science Department, American Cancer Society, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Craig E Pollack, Department of Health Policy and Management, Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA; Johns Hopkins School of Nursing, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Data Availability

No data were generated or analyzed for this commentary.

References

- 1. Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health: Commission on Social Determinants of Health Final Report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alcaraz KI, Wiedt TL, Daniels EC, Yabroff KR, Guerra CE, Wender RC. Understanding and addressing social determinants to advance cancer health equity in the United States: a blueprint for practice, research, and policy. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(1):31-46. doi: 10.3322/caac.21586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Asgary R, Garland V, Sckell B. Breast cancer screening among homeless women of New York City shelter-based clinics. Womens Health Issues. 2014;24(5):529-534. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Berchuck JE, Meyer CS, Zhang N, et al. Association of mental health treatment with outcomes for US veterans diagnosed with non-small cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(7):1055-1062. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schootman M, Deshpande AD, Pruitt SL, Jeffe DB. Neighborhood foreclosures and self-rated health among breast cancer survivors. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(1):133-141. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9929-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cox R, Henwood B, Rodnyansky S, Rice E, Wenzel S. Road map to a unified measure of housing insecurity. Cityscape. 2019;21(2):93-128. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2817626. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bucholtz S. Measuring Housing Insecurity in the American Housing Survey. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Office of Policy Development and Research; 2018. https://www.huduser.gov/portal/pdredge/pdr-edge-frm-asst-sec-111918.html. Accessed April 4, 2022.

- 8. Cox R, Rodnyansky S, Henwood B, Wenzel SL. Measuring population estimates of housing insecurity in the United States: a comprehensive approach. CESR-Schaeffer Working Paper (2017–012). 2017:1-3. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3086243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, Committee on Financial Services. Testimony of Diane Yentel, President and CEO, National Low Income Housing Coalition. https://financialservices.house.gov/uploadedfiles/12.21.201_diane_yentel_testimony.pdf. Accessed February 20, 2022.

- 10. Aurand A, Emmanuel D, Threet D, Yentel D. Out of reach: the high cost of housing 2020. National Low Income Housing Coalition; 2020:281. https://nlihc.org/sites/default/files/oor/2021/Out-of-Reach_2021.pdf. Accessed February 20, 2022.

- 11.America’s rental housing 2020. Jt Cent Hous Stud Harvard Univ.; 2020:1-44. https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/reports/files/Harvard_JCHS_Americas_Rental_Housing_2020.pdf. Accessed February 20, 2022.

- 12. Aurand A, Emmanuel D, Threet D, Rafi I. The gap: a shortage of affordable homes 2021. National Low Income Housing Coalition; 2021:31. https://reports.nlihc.org/sites/default/files/gap/Gap-Report_2021.pdf. Accessed February 20, 2022.

- 13. Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University. The State of the Nation’s Housing; 2017. http://www.jchs.harvard.edu/research/state_nations_housing. Accessed May 10, 2021.

- 14. Hahn JA, Kushel MB, Bangsberg DR, Riley E, Moss AR. Brief report: the aging of the homeless population: fourteen-year trends in San Francisco. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(7):775-778. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00493.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pollack CE, Griffin BA, Lynch J. Housing affordability and health among homeowners and renters. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39(6):515-521. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jelleyman T, Spencer N. Residential mobility in childhood and health outcomes: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(7):584-592. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.060103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hutchings HA, Evans A, Barnes P, et al. Residential moving and preventable hospitalizations. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20152836. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Oishi S, Schimmack U. Residential mobility, well-being, and mortality. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2010;98(6):980-994. doi: 10.1037/a0019389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moody HA, Darden JT, Pigozzi BW. The relationship of neighborhood socioeconomic differences and racial residential segregation to childhood blood lead levels in Metropolitan Detroit. J Urban Health. 2016;93(5):820-839. doi: 10.1007/s11524-016-0071-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hillier AE. Redlining and the homeowners’ loan corporation. J Urban Hist. 2003;29(4):394-420. doi: 10.1177/0096144203029004002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fullilove MT, Wallace R. Serial forced displacement in American cities, 1916-2010. J Urban Health. 2011;88(3):381-389. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9585-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Norman PS, Daniel E, Shumer NJN. Mass incarceration, race inequality, and health: expanding concepts and assessing impacts on well-being. Physiol Behav. 2017;176(12):139-148. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.08.042.Mass28363838 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lipsitz G. In an avalanche every snowflake pleads not guilty: the collateral consequences of mass incarceration and impediments to women’s fair housing rights. UCLA Law Rev. 2012;59(6):1746-1809. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Swope CB, Hernández D. Housing as a determinant of health equity: a conceptual model. Soc Sci Med. 2019;243:112571.doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Krieger N, Wright E, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Huntley ER, Arcaya M. Cancer stage at diagnosis, historical redlining, and current neighborhood characteristics: breast, cervical, lung, and colorectal cancers, Massachusetts, 2001-2015. Am J Epidemiol. 2020;189(10):1065-1075. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwaa045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Beyer KMM, Zhou Y, Laud PW, et al. Mortgage lending bias and breast cancer survival among older women in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(25):2749-2757. doi: 10.1200/jco.21.00112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Cancer Policy Forum of the National Academies of Science Engineering and Medicine. Housing insecurity among patients with cancer: a webinar; 2021. https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/08-09-2021/housing-insecurity-among-patients-with-cancer-a-webinar. Accessed February 6, 2022.

- 28. Taylor L. Housing and health: an overview of the literature. Heal Aff Heal Policy Br. 2018. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20180313.396577/. Accessed February 20, 2022. doi: 10.1377/hpb20180313.396577. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bonnefoy X. Inadequate housing and health: an overview. Int J Environ Pollut. 2007;30(3/4):411-429. doi: 10.1504/IJEP.2007.014819. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Krieger J, Higgins DL. Housing and health: time again for public health action. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(5):758-768. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.5.758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University. America’s Rental Housing 2022; 2022. https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/americas-rental-housing-2020. Accessed February 20, 2022.

- 32. Gaskin DJ, Dinwiddie GY, Chan KS, McCleary RR. Residential segregation and the availability of primary care physicians. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(6):2353-2376. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01417.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Estabrooks PA, Lee RE, Gyurcsik NC. Resources for physical activity participation: does availability and accessibility differ by neighborhood socioeconomic status? Ann Behav Med. 2003;25(2):100-104. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2502_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Onega T, Shi X, Wang D, Demidenko E, Goodman D. Geographic Access to Cancer Care in the U.S. Cancer. 2008;112(4):909–918. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lovasi GS, Hutson MA, Guerra M, Neckerman KM. Built environments and obesity in disadvantaged populations. Epidemiol Rev. 2009;31(1):7-20. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxp005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. Moving to opportunity: an experimental study of neighborhood effects on mental health. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(9):1576-1582. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.9.1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crowder K, Downey L. Interneighborhood migration, race, and environmental hazards: modeling micro-level processes of environmental inequality. Am J Sociol. 2010;115(4):1110–1149. doi: 10.1086/649576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Keet CA, Keller JP, Peng RD. Long-term coarse particulate matter exposure is associated with asthma among children in Medicaid. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(6):737-746. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201706-1267OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pollack C, Sadegh-Nobari T, Dekker M, Egerter S, Braveman P. Where we live matters for our health: the links between housing and health. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2008. http:// www.commissiononhealth.org/PDF/e6244e9e-f630- 4285-9ad7-16016dd7e493/Issue%20Brief%202% 20Sept%2008%20%20Housing%20and%20Health.pdf. Accessed February 20, 2022.

- 40. Foverskov E, Petersen GL, Pedersen JLM, et al. Economic hardship over twenty-two consecutive years of adult life and markers of early ageing: physical capability, cognitive function and inflammation. Eur J Ageing. 2020;17(1):55-67. doi: 10.1007/s10433-019-00523-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Miller GE. Psychological stress and disease. J Am Med Assoc. 2007;298(14):1685-1687. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.14.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Costanzo ES, Sood AK, Lutgendorf SK. Biobehavioral influences on cancer progression. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2011;31(1):109-132. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nagaraja AS, Sadaoui NC, Dorniak PL, Lutgendorf SK, Sood AK. SnapShot: stress and disease. Cell Metab. 2016;23(2):388-388.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Solar O, Irwin A. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. WHO Document Production Services; 2010:79. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44489/?sequence=1. Accessed February 20, 2022.

- 45. Martin P, Liaw W, Bazemore A, Jetty A, Petterson S, Kushel M. Adults with housing insecurity have worse access to primary and preventive care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2019;32(4):521-530. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2019.04.180374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Clark CR, Baril N, Kunicki M, et al. Addressing social determinants of health to improve access to early breast cancer detection: results of the Boston REACH 2010 Breast and Cervical Cancer Coalition Women’s Health Demonstration Project. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2009;18(5):677-690. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.0972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Clark CR, Baril N, Hall A, et al. Case management intervention in cervical cancer prevention: the Boston REACH coalition women’s health demonstration project. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2011;5(3):235-247. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2011.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Asgary R, Garland V, Jakubowski A, Sckell B. Colorectal cancer screening among the homeless population of New York City shelter-based clinics. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(7):1307-1313. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. May FP, Bromley EG, Reid MW, et al. Low uptake of colorectal cancer screening among African Americans in an integrated Veterans Affairs health care network. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80(2):291-298. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.01.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Berkowitz SA, Hulberg AC, Hong C, et al. Addressing basic resource needs to improve primary care quality: a community collaboration programme. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(3):164-172. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Costas-Muniz R, Leng J, Aragones A, et al. Association of socioeconomic and practical unmet needs with self-reported nonadherence to cancer treatment appointments in low-income Latino and Black cancer patients. Ethn Health. 2016;21(2):118-128. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2015.1034658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Banegas MP, Dickerson JF, Zheng Z, Murphy C, Tucker-Seeley R, Yabroff KR. Assessing the influence of social risks on health and health care outcomes among patients with cancer. American Public Health Association 2021 Annual Meeting & Expo; October 24-27, 2021; Denver, CO. Abstract nr 493838.

- 53. Castro Baker A, West S, Wood A. Asset depletion, chronic financial stress, and mortgage trouble among older female homeowners. Gerontologist. 2019;59(2):230-241. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnx137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Beyer KMM, , ZhouY, , MatthewsK, , BemanianA, , LaudPW, , Nattinger AB. New spatially continuous indices of redlining and racial bias in mortgage lending: links to survival after breast cancer diagnosis and implications for health disparities research. Health Place. 2016;40:34-43. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zhou Y, , BemanianA, , Beyer KMMM. Housing discrimination, residential racial segregation, and colorectal cancer survival in southeastern Wisconsin. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(4):561-568. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Altice CK, Banegas MP, Tucker-Seeley RD, Yabroff KR. Financial hardships experienced by cancer survivors: a systematic review. Jnci J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(2):djw205.doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Shankaran V, Unger JM, Darke AK, et al. S1417CD: a prospective multicenter cooperative group-led study of financial hardship in metastatic colorectal cancer patients. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022;114(3):372-380. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djab210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yabroff KR, Mariotto A, Tangka F, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, part 2: patient economic burden associated with cancer care. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113(12):1670-1682. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djab192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Pisu M, Henrikson NB, Banegas MP, Yabroff KR. Costs of cancer along the care continuum: what we can expect based on recent literature. Cancer. 2018;124(21):4181-4191. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. De Moor JS, Alfano CM, Kent EE, et al. Recommendations for research and practice to improve work outcomes among cancer survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110(10):1041-1047. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djy154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Bona K, Dussel V, Orellana L, et al. Economic impact of advanced pediatric cancer on families. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47(3):594-603. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Abrams HR, Durbin S, Huang CX, et al. Financial toxicity in cancer care: origins, impact, and solutions. Transl Behav Med. 2021;11(11):2043-2054. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibab091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Carroll A, Corman H, Curtis MA, Noonan K, Reichman NE. Housing instability and children’s health insurance gaps. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17(7):732-738. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2017.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Keene DE, Lynch JF, Baker AC. Fragile health and fragile wealth: mortgage strain among African American homeowners. Soc Sci Med. 2014;118(C):119-126. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.07.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Houle JN, Keene DE. Getting sick and falling behind: health and the risk of mortgage default and home foreclosure. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69(4):382-387. doi: 10.1136/jech-2014-204637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Integrating social care into the delivery of health care: moving upstream to improve the nation’s health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2019. doi: 10.17226/25467. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 67. McLouth LE, Nightingale CL, Dressler EV, et al. Current practices for screening and addressing financial hardship within the NCI community oncology research program. Cancer Epidemiol Prev Biomarkers. 2021;30(4):669-675. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-20-1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Khera N, Sugalski J, Krause D, et al. Current practice for screening and management of financial distress at NCCN member institutions. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(suppl 15):11615. doi:10.1200/J Clin Oncol.2019.37.15_suppl.11615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Yabroff KR, Bradley CJ, Shih Y-CT. Improving the process of screening for medical financial hardship in oncology practice. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2021;30(4):593-596. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-21-0111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Barclay ME, Abel GA, Greenberg DC, Rous B, Lyratzopoulos G. Socio-demographic variation in stage at diagnosis of breast, bladder, colon, endometrial, lung, melanoma, prostate, rectal, renal and ovarian cancer in England and its population impact. Br J Cancer. 2021;124(7):1320-1329. doi: 10.1038/s41416-021-01279-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. McCormack V, Aggarwal A. Early cancer diagnosis: reaching targets across whole populations amidst setbacks. Br J Cancer. 2021;124(7):1181-1182. doi: 10.1038/s41416-021-01276-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Lewis C. Strategies to increase awareness of social risks in cancer care. Conf Present Natl Cancer Institute Addressing Soc Risks Cancer Care Deliv Virtual Work. 2021;32(3):232-234. doi: 10.13110/antipodes.28.1.0166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Gruß I, Varga A, Brooks N, Gold R, Banegas MP. Patient interest in receiving assistance with self- reported social risks. J Am Board Fam Med. 2021;34(5):914-924. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2021.05.210069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Hamilton BA. OCM Key Drivers and Change Package. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2020. https://innovation.cms.gov/files/x/ocm-keydrivers-changepkg.pdf. Accessed February 20, 2022.

- 75. de Moor JS, Mollica M, Sampson A, et al. Delivery of financial navigation services within National Cancer Institute-designated cancer centers. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2021;5(3):3-8. doi: 10.1093/jncics/pkab033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Bona K, London WB, Guo D, Frank DA, Wolfe J. Trajectory of material hardship and income poverty in families of children undergoing chemotherapy: a prospective cohort study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63(1):105-111. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Paskett ED, Harrop JP, Wells KJ. Patient navigation: an update on the state of the science. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(4):237-249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Dixit N, Rugo H, Burke NJ. Navigating a path to equity in cancer care: the role of patient navigation. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2021;41:3-10. doi: 10.1200/edbk_100026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. American College of Surgeons. Cancer Program Standards 2012: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2011. https://apos-society.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/CoCStandards.pdf. Accessed February 20, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 80. Bernardo B, Meadows R. The efficacy and cost-effectiveness of patient navigation programs across the cancer continuum: a systematic review. Cancer. 2019;125(16):2747-2761. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Franco T, Schreiner S, Rodabaugh KJ, Stensland S. Establishing a medical-legal partnership program for cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(suppl):281. https://ascopubs.org/doi/abs/10.1200/jco.2013.31.31_suppl.281. Accessed February 20, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 82. Hernández D. ‘Extra oomph:’ addressing housing disparities through medical legal partnership interventions. Hous Stud. 2016;31(7):871-890. doi: 10.1080/02673037.2016.1150431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Tsai J, Middleton M, Villegas J, et al. Medical-legal partnerships at Veterans Affairs medical centers improved housing and psychosocial outcomes for vets. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(12):2195-2203. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Hessler D, Bowyer V, Gold R, Shields-Zeeman L, Cottrell E, Gottlieb LM. Bringing social context into diabetes care: intervening on social risks versus providing contextualized care. Curr Diab Rep. 2019;19(6):1-7. doi: 10.1007/s11892-019-1149-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. National Health Care for the Homeless Council. Medical respite care. 2021. https://nhchc.org/clinical-practice/medical-respite-care/. Accessed February 6, 2022.

- 86. Billioux A, Conway PH, Alley DE. Addressing population health: integrators in the accountable health communities model. JAMA. 2017;318(19):1865-1866. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.15063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Armstrong Brown J, Berzin O, Clayton M. Accountable Health Communities (AHC) Model Evaluation. First Evaluation Report. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI International; 2020. https://innovation.cms.gov/data-and-reports/2020/ahc-first-eval-rpt. Accessed February 20, 2022.

- 88. National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Investing in interventions that address non-medical, health-related social needs: proceedings of a workshop. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2019. doi: 10.17226/25544. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 89. Boston Medical Center. Boston Medical Center to invest $6.5 million in affordable housing to improve community health and patient outcomes, reduce medical costs [press release]; 2017. https://www.bmc.org/news/press-releases/2017/12/07/boston-medical-center-invest-65-million-affordable-housing-improve. Accessed February 6, 2022.

- 90. Mohan G, Chattopadhyay S. Cost-effectiveness of leveraging social determinants of health to improve breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening: a systematic review. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(9):1434-1444. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Hernández D, Swope CB. Housing as a platform for health and equity: evidence and future directions. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(10):1363-1366. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network, National Comprehensive Cancer Network, National Minority Quality Forum. Elevating cancer equity: recommendations to reduce racial disparities in guideline adherent cancer care; February 21, 2021. https://www.nccn.org/docs/default-source/oncology-policy-program/2021_elevating_cancer_equity_webinar_slides.pdf?sfvrsn=e11f66e4_2. Accessed February 20, 2022.

- 93. Cartier Y, Burnett J, Fichtenberg C, Morganstern E, Terens N, Altschuler SP, CBO Perspectives on Community Resource Referral Platforms: Findings from Year 1 of Highlighting and Assessing Referral Platform Participation (HARP). Trenton, NJ: Trenton Health Team; 2021. https://sirenetwork.ucsf.edu/tools-resources/resources/cbo-perspectives-community-resource-referral-platforms-findings-year-1. Accessed February 20, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 94. Cartier Y, Fichtenberg C, Gottlieb LM. Implementing community resource referral technology: facilitators and barriers described by early adopters. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(4):662-669. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Davis RE, Trickey AW, Abrahamse P, Kato I, Ward K, Morris AM. Association of cumulative social risk and social support with receipt of chemotherapy among patients with advanced colorectal cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(6):1-14. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.13533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data were generated or analyzed for this commentary.