Abstract

Gliomas are the most commonly occurring primary brain tumor with poor prognosis and high mortality rate. Currently, the diagnostic and monitoring options for glioma mainly revolve around imaging techniques, which often provide limited information and require supervisory expertise. Liquid biopsy is a great alternative or complementary monitoring protocol that can be implemented along with other standard diagnosis protocols. However, standard detection schemes for sampling and monitoring biomarkers in different biological fluids lack the necessary sensitivity and ability for real-time analysis. Lately, biosensor-based diagnostic and monitoring technology has attracted significant attention due to several advantageous features, including high sensitivity and specificity, high-throughput analysis, minimally invasive, and multiplexing ability. In this review article, we have focused our attention on glioma and presented a literature survey summarizing the diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive biomarkers associated with glioma. Further, we discussed different biosensory approaches reported to date for the detection of specific glioma biomarkers. Current biosensors demonstrate high sensitivity and specificity, which can be used for point-of-care devices or liquid biopsies. However, for real clinical applications, these biosensors lack high-throughput and multiplexed analysis, which can be achieved via integration with microfluidic systems. We shared our perspective on the current state-of-the-art different biosensor-based diagnostic and monitoring technologies reported and the future research scopes. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first review focusing on biosensors for glioma detection, and it is anticipated that the review will offer a new pathway for the development of such biosensors and related diagnostic platforms.

I. INTRODUCTION

Gliomas are tumors found in the central nervous system of humans. They owe their genesis to abnormal tissue growth in the glial cells of the brain and spine. This type of malignancy shows a significantly high death rate and poor prognosis, due to multiple factors including higher chances of metastasis and recurrence.1 Around 28.2% of all deceased in Canada in 20212 were directly or indirectly linked with cancer, making it the most common cause of death in this country. Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), a subtype of glioma, is the most predominant and aggressive form of brain cancer, killing 225 000 people annually.3 It accounts for over 60% of all brain tumors in adults,3 with a merely 12–14 months of survival time (median) in Canada4 which gets even lower to less than 4% for age-group 45–64 and 14% for younger adults (20–44 years old).4 Such devastating numbers make early detection of gliomas through current biosensing technology a crucial task for glioma cancer management.

Currently, the primary diagnosis of glioma is accomplished by taking brain scans or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), followed by tissue biopsy for decisive grading and characterization of the tumor.5 Although tissue biopsies are the go-to technique for diagnosis of any form of brain tumor, resection from it during the biopsy procedure requires very invasive surgical interventions, which may cause brain swelling or degrade neural functioning.6 Moreover, some tumors might be present in a surgically inaccessible location.7 Liquid biopsy is an alternative technique to probe into the tumor in a minimally invasive manner by detecting and quantifying tumor diagnostic biomarkers in bodily fluids. Liquid biopsy can also allow to monitor a tumor prognosis via prognostic biomarker. Currently, prognosis of brain tumors is monitored by imaging methods such as MRI;5 however, there are significant chances of pseudoprognosis8 with imaging methods. This makes liquid biopsy a great technique to complement with the current standards.

At present, the mainly approved glioma detection methods are imaging techniques like magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computerized tomography (CT) scans, which are backed up by tissue biopsy. All these techniques are costly and required to be done under the supervision of an expert. Also, most of these treatment protocols start after the onset of symptoms, which sometimes is too late for the patient to get effective treatment. Advancement in biosensor technologies for sensitive and specific detection of biomarkers associated with glioma holds great promise in terms of point-of-care treatment and liquid biopsies. Biosensors can provide information about biomarkers that arise at the initial stages of cancer, providing a window for early diagnosis and thus better survival rates for glioma. Depending on the transduction principle, different biosensing technologies like optical, electrochemical, or electrical biosensors have shown great potential for cancer diagnosis. The real-time evaluation of cancer biomarkers drug resistant mutations will allow a physician to implement precision medicine, which could be beneficial for the overall survival of the patient.

Numerous reviews have been published in recent years inspecting biosensor development for different forms of cancers such as lung cancer,9–13 breast cancer,14–17 and prostate cancer.18–21 However, any such study related to brain cancer biomarkers was not found. A possible reason for such a lack of reviews could be the rarity of brain cancer occurrence when compared to the other major cancers. Nonetheless, the poor prognosis and extremely low survival rate for brain cancer have inspired numerous research groups to invest their time in developing biosensors capable of detecting associated biomarkers for glioma. In this review, we discussed the recent advances made in the development of such biosensors. We focused our review on label-free detection schemes only. While labeled detection schemes are more established and can detect cancer with very high sensitivity and accuracy, it is very difficult to implement real-time analysis with a labeled approach. Label-free detection schemes are much more suitable for real-time analysis and can provide an important drive toward precision medicine. This review presents the current advances in label-free detection schemes and indicates research gaps that need to be worked in order to establish label-free biosensing on par with labeled schemes.

The review begins with a brief literature survey of the plethora of biomarkers reported to be associated with glioma and continues to review different biosensing technologies divided according to their transduction principle. Tables have been prepared at the end of each section enlisting all the key literatures related to biosensor for the detection of glioma. At the end, a brief perspective of future research in this field has been discussed with respect to different application types like POC devices, liquid biopsies, and even implantable biosensors.

II. BIOMARKERS FOR GLIOMA

Biomarkers can be defined as a set of quantitative chemical molecules or physiological characteristics, which acts as an indicator of certain processes under normal condition or under external intervention.22 Biomarkers can range from very simple measurements, such as pH, blood pressure, or temperature, to complex biomolecules like DNA, proteins, or enzymes. Along a treatment process, biomarkers play a vital role related to the treatment direction and outcome. Depending on the clinical continuum, biomarkers can be classified into several types such as diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive biomarkers. A clinical continuum generally begins with the screening of diagnostic biomarker in order to detect the presence or absence of certain diseases. Then, prognostic biomarkers are screened to determine how likely a particular clinical event is in a patient such as disease recurrence or progression. Predictive biomarkers or therapeutic biomarkers are used to determine if an individual is more or less likely to develop a favorable or unfavorable symptom when exposed to an external factor such as a medical product or environmental agent.23

Gliomas shed different types of tumoral contents into circulation, which can be extracted from bodily fluids as potential biomarkers.24 The sampling and probing of these biomolecules from a biofluid is called liquid biopsy.25 Liquid biopsies have certain advantages over tissue biopsies during cancer management.26,27 It gives a minimally invasive route to capture real-time cancer activities, which is particularly useful for deep lying glioma tissues where surgical access is limited. It can also be a viable option for patients with recurrence and ineligible for surgical intervention. For glioma, liquid biopsy can be carried out either by sampling blood through venepuncture or by sampling cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) through a lumbar puncture.28

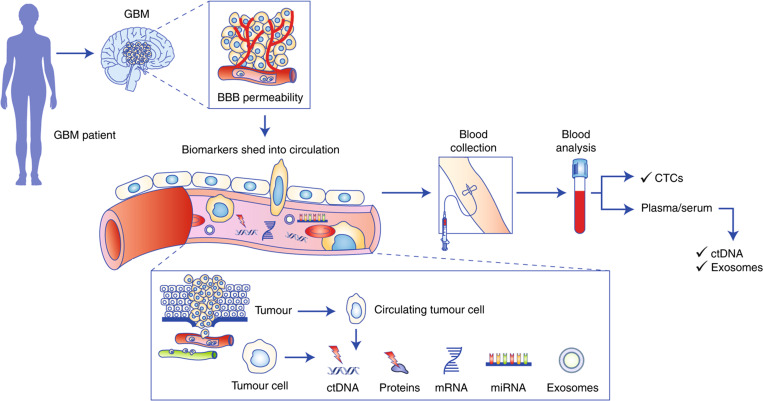

Blood–brain barrier (BBB) complicates the liquid biopsy for gliomas. For a tumor-specific material to enter the bloodstream and become a potential biomarker, it needs to cross the tight junction of BBB regulated by several transmembrane proteins like claudin-3 and claudin-5.29 Recent studies have shown that GBM can induce an inflamed microenvironment, which can decrease the “tightness” of a BBB junction30 or even disrupting its function,31 making it more permeable. This allows several biomarkers to cross the BBB junction and circulate into the bloodstream. Different types of such circulating biomarkers associated with glioma are described in the Secs. II A–II E and some important biomarkers are summarized in Table I. Most of the biomarkers mentioned in this review are “potential biomarkers” for glioma. Unlike other forms of cancer like lung cancer, breast cancer, or prostate cancer, glioma does not have specific FDA approved biomarkers yet. It is noted from the literature review that this is still a research in progress. A panel of such biomarkers, however, can be utilized to increase the accuracy of glioma detection. Figure 1 summarizes the transport of different biomarkers from a GBM.

TABLE I.

A brief summary of important glioma biomarkers. ↑: upregulation; =: presence for detection; ↓: downregulation; −: poor progression or therapeutic outcome on upregulation; +: better progression or therapeutic outcome on upregulation.

| Biomarker type | Biomarker | Classification | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| – | Diagnostic | Prognostic | Predictive | – | |

| microRNA | miR-21 | ↑ | − | − | 35, 36, 39, 41, 90–99 |

| miR-10b | ↑ | − | − | 43, 91, 98, 100, 101 | |

| miR-155 | ↑ | − | – | 93, 102 | |

| miR-15b | ↑ | + | – | 99, 103, 104 | |

| miR-222 | ↑ | − | – | 35, 38, 105, 106 | |

| miR-221 | ↑ | − | – | 39, 94, 105–109 | |

| miR-124 | ↓ | + | 39, 92, 110 | ||

| miR-125b | ↓ | − | + | 105, 111 | |

| miR-7-5p | ↓ | 112 | |||

| miR-181d | ↓ | + | 41, 44 | ||

| – | – | – | – | – | |

| Extracellular vesicles | EGFRvIII protein | − | – | 51–53, 55, 113 | |

| CD44 | ↑ | − | – | 57–60, 114–117 | |

| CD133 | ↑ | − | – | 115, 118 | |

| TGFB1 | ↑ | − | – | 56, 57, 119, 120 | |

| MCT1 | ↑ | − | – | 121–124 | |

| MCT4 | ↑ | − | – | 125, 126 | |

| – | – | – | – | – | |

| Proteins | GFAP | ↑ | – | 63–66 | |

| VEGF | ↑ | − | – | 70–72 | |

| YKL-40 | ↑ | − | – | 63, 67–69, 127 | |

| – | – | – | – | – | |

| Circulatory tumor DNA | EGFR amplification | − | – | 28, 51, 52, 81 | |

| MGMT promoter methylation | − | – | 76–80 | ||

| IDH1 mutation | − | – | 28, 81–83 | ||

| 1p/19q codeletion | − | – | 28, 76 | ||

| – | – | – | – | – | |

| Metabolites | Glutamate | ↑ | – | + | 88, 89, 128–130 |

| Cysteine | ↑ | – | 85, 87 |

FIG. 1.

A schematic representation of the pathway of biomarker flow from a brain tumor through the blood–brain barrier into the blood circulation. Reproduced from Müller Bark et al., Br. J. Cancer 122, 295–305 (2020). Copyright 2020 Springer Nature.

A. microRNA

MicroRNAs (miR) are small non-coding RNA with around 22 nucleotides. They do not participate in the protein transcription phase directly, but interact with the messenger RNAs (mRNAs) and dictate gene expression.32,33 MicroRNAs play a crucial role in the carcinogenesis of cancer cells,34 thus making them a potential biomarker for malignancy. Up to date, over 300 different miRNAs have been reported to be correlated with glioma and, therefore, a meta-analysis of these studies over a larger sample35 is required to select a panel of microRNAs for diagnostic, prognostic, or predictive applications. Nonetheless, a handful of significant microRNAs has been summarized in Table I, depending on the frequency of them reported over different literatures.

miR-21 has shown great promise as a possible diagnostic marker for glioma detection.35 Significant upregulation of miR-21 has been observed in the pre-operative serum samples of GBM patients.36 Upregulation of miR-21 is also associated with poorer progression of glioma37,38 with a negative correlation to overall survival and progression-free survival.34–40 Upregulated miR-21 correlates to poorer response to temozolomide (TMZ),41 a therapeutic drug for glioma, and radio-resistance.42 miR-10b and miR-221 have also shown great promise as prognostic biomarkers.37–43 On the other hand, as a predictive biomarker, miR-181d can be deemed very useful. Elevated levels of miR-181d are observed to be associated with a decreased level of O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) expression (a genomic marker for glioma, to be discussed in Sec. II D)44 and overall better response to TMZ therapy.41

The short lifespan of microRNA45 in body fluids (<3 h) along with their trace amount makes them a challenging biomarker for cancer management. Despite that, numerous optical and electronic biosensors have been developed with remarkably low limit of detection for analysis of microRNAs sampled from serum and blood.

B. Extracellular vesicles

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are cell released lipid bounded vesicles, which play a significant role in cell-to-cell communication. Usual contents of an EV include mRNA, miRNA, DNA, and cellular proteins.46 These vesicles carry cellular materials from one cell to another, even distance apart, and play an influential role in controlling the cellular phenotype of recipient.47 Therefore, EVs can help in glioma progression by promoting processes such as angiogenesis, invasion, and migration.48 EVs can be broadly categorized into two types based on their sizes and origin. These are exosomes and microvesicles (MVs). Exosomes are smaller EVs with a diameter ranging from 30 to 150 nm and originate from endosomal membrane. MVs are relatively larger in size, around 50–1300 nm, and originate via budding of cell membrane.47

Exosomes can be characterized by their surface proteins and inner contents, making them a viable analyte for current biosensors. The presence of membrane-associated proteins like cluster of differentiation 63 (CD63), CD9, and CD81 are signature markers for exosomes released by any cell.47 Higher concentration of exosomes has been correlated to the presence and recurrence of glioma.49 Internal environment of exosomes has also shown elevated levels of certain microRNAs associated with glioma such as miR-21.50 Other studies observed the presence of glioma-associated mutation in exosomes such as EGFRvIII mutation51–53 and IDH1 mutation.53,54

Detecting surface proteins with current biosensing strategies (optical or electrochemical) is advantageous over probing the inner environment, as fewer pre-processing steps are required for sample preparation. This makes certain membrane-associated proteins of great interest. For instance, mutation in epidermal growth factor receptor variant-III (EGFRvIII) can express itself as EGFRvIII mutant protein on the glioma cell and glioma-associated exosome surfaces.55 Another extracellular matrix protein called transforming growth factor-beta-induced protein (TGFB1) is observed to be upregulated and produced by glioma cells under hypoxic condition.56 The protein is also associated with malignant progression and promotion of angiogenesis in glioma.56,57 Cluster of differentiation protein 44 and 133 are also found to be associated with glioma progression and, thus, can be useful to track tumor malignancy.58–60 Such surface proteins can be simply captured on a biosensing surface using antibody or aptamer probes for sensitive and specific detection, given they are effectively isolated from the heterogeneous medium.

C. Proteins

Certain proteins and peptides play a pivotal role in cancer-related processes like angiogenesis, proliferation, and vascularization. Elevated levels of such proteins can act as a great diagnostic biomarker. For example, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) is important to aid in astrocytic structures and stability, thus act as a marker for brain strokes61 and trauma.62 However, GFAP levels are found elevated in glioma patients.63–66 One of the reasons for elevated GFAP in glioma patients is the destruction of glial cells and opening of BBB.30,31 This makes GFAP a potential diagnostic marker for glioma. YKL-40 (Chitinase 3-like 1) is another protein, which is known to stimulate angiogenesis, cell proliferation, and prevent apoptosis.67 YKL-40 is present in higher concentration in GBM patients and associated with a significantly worse overall survival.68 Patients with partial and total resection of glioma have shown a significant difference in YKL-40 levels, with the latter showing lower levels.69 Another example of protein biomarker for glioma is vascular endothelial growth factor or VEGF. VEGF is a growth factor that aids in formation of new blood vessels in the periphery of glioma tissue (also known as neovascularization) and has been observed at elevated levels in malignant glioma patients.70–72

D. Circulatory tumor DNA

Alterations, even a single base-pair (single nucleotide polymorphism), of specific genes like tumor-suppressor genes, protooncogenes, and cell cycle regulator genes are proven to be an essential step for cancer development.73 These genetic mutations can be monitored by capturing a trace amount of circulatory tumor DNA (ctDNA) or cell-free DNA (cfDNA) ejected into the bloodstream or CSF by apoptotic or necrotic cells.74 The amount of ctDNA also correlates with the prognosis of cancer, with a higher amount of ctDNA often present in later stage patients.75 Several genetic mutations have been reported to be linked with glioma such as MGMT promoter methylation,76–80 isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) mutation,28–83 1p/19q codeletion,28–76 EGFR amplification,28–81 and phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) methylation.28–81 Most of the reported studies have extracted ctDNA from the bloodstream or CSF of glioma patients, and quantified the sequence using PCR based techniques. Trace amounts of ctDNA (∼0.01% of total blood cfDNA pool) combined with its short lifespan84 (half-life < 1.5 h) make their detection a challenging task. A recent report, focusing on ctDNA detection, has been discussed in the Sec. V.

E. Metabolites

Metabolites are the ultimate product yields through different genomic or transcriptomic processes. Alteration in the relative concentration of these low molecular weight molecules in various biofluids can be a potential indicator of the state of the malignancy. In relation to glioma, few studies have been performed to pin down potential metabolic biomarkers. For instance, cysteine can be considered a diagnostic glioma biomarker. Cysteine is the precursor of glutathione synthesis and plays a key role in survival of glioma cells85 and poor progression-free survival in GBM.86 Upregulation of cysteine is observed in the serum of GBM patients.87 Another potential biomarker is glutamate. It is produced as a by-product of glutathione synthesis in glioma cells and plays a central part in glioma malignant phenotype.88 Release of a large amount of glutamate leads to excitotoxic death in neighboring neurons, thereby generating more space for cell motility.89 Glutamate levels in bodily fluids can be a potential biomarker for glioma.

III. OPTICAL BIOSENSORS FOR GLIOMA

Optical biosensors are analytical devices in which the biorecognition element of the sensor is integrated with an optical transduction system.131 A wide range of optical properties of the sensor surface can be probed for optical biosensing, such as refractive index, wavelength, and intensity. An effective quantitative method for liquid biopsy analysis requires a low limit of detection (LOD) with high-throughput multiplexed screening in real-time under small sample volume.132,133 Considering these requirements, optical biosensors have displayed promising performance. Depending on the principle of detection, optical biosensors are classified into several categories like surface plasmon resonance (SPR), surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS), fluorescence, and colorimetric. Sections III A and III B will discuss these major techniques with an example of research works related to glioma detection, summarized in Table II.

TABLE II.

Summary of optical biosensors for detection of glioma biomarkers.

| Optical biosensor type | Biomarkers | Specimen | Linear/dynamic range | LOD | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biotinylated anti-CD63 and anti-EGFRvIII AB on TiN chip | Exosomal protein CD63 and EGFRvIII | Exosomes derived from U251 cell line and mouse serum | 0.005–1000 μg/ml (dynamic) | CD-63: 4.29 ng/ml EGFRvIII: 2.75 ng/ml | Qiu et al.134 |

| TiN nanohole (NH) LSPR chip with biotinylated antibodies | Exosomal protein CD63, CD44, and CD133 (and EGFRvIII) | Exosomes derived from U87 GBM cell line, blood serum, and CSF | 0.005–50 μg/ml (dynamic) | CD44: 3.46 ng/ml | Thakur et al.136 |

| Self-assembly (SAM)-AuNI LSPR biosensor chip | Exosomal protein MCT1 and CD147 | Exosomes derived from U251, U87, U118, and A172 GMs and blood serum | … | … | Thakur et al.124 |

| TiO2-columnar thin films (CTFs)-Au nanoislands (AuNIs) LSPR chip | Exosomal protein CD63 and BIGH3 | Exosomes derived from U251 cell line | 0.001–500 μg/ml (dynamic) | CD63: 4.24 ng/ml BIGH3: 3.84 ng/ml | Xu et al.137 |

| Ag@AuNI LSPR chip with biotinylated anti-CD63 and anti-MCT4 AB | Exosomal protein CD63 and MCT4 | Exosomes derived from U87 cell line and mouse blood serum | 0.0005–50 μg/ml (dynamic) | CD-63: 0.38 ng/ml MCT4: 1.4 ng/ml MCT4 from blood serum: 0.4 ng/ml | Liu et al.138 |

| SPR based biosensor with streptavidin functionalized Au nanorods for signal amplification | MicroRNA-16-5p | … | Without Ste-AuNR: 0.1–100 nM (linear) With Ste-AuNR: 0.1–100 pM (linear) | Without Ste-AuNR: 0.054 nM With Ste-AuNR: 0.045 pM | Hao et al.139 |

| SERS based biosensor with head-flocked Au nanopillar | MicroRNA 10b, 21, 373 | … | … | 10b: 3.53 fM 21: 2.17 fM 373: 2.16 fM | Kim et al.149 |

| SERS based biosensor embedded with nanobowtie shaped antennas | EVs | Extracellular vesicles derived from U87 and U373 GM cell line | 105–108 particles/ml (linear) | 1.32 × 105 particles/ml | Jalali et al.147 |

A. Surface plasmon resonance

Surface plasmon resonance or SPR is the sensitive optical detection of analytes utilizing evanescent wave near the surface. When an electromagnetic wave is irradiated on the interface of a dielectric material and metal, the conduction electrons start to oscillate in resonance with the electromagnetic wave. This resonance oscillation can propagate through the interface in form of a non-radiative transverse–magnetic (TM) wave known as surface plasmon polariton (SPP) wave. The evanescent field penetrates into both the media up to a certain decay length, with a depth of penetration larger on the dielectric side. This makes the SPP wave extremely sensitive to small changes in refractive index (RI) of the dielectric medium. When analytes combine with the surface receptor probes, the RI of the medium increases, thereby increasing the propagation constant of the excited SPP wave. This property makes up the underlying principle of SPR biosensing.

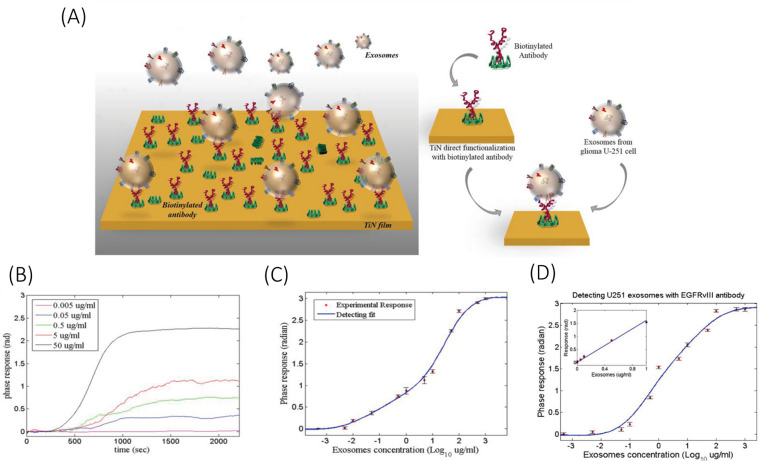

One of the first papers reported in terms of glioma detection was based on SPR. Qiu et al.134 developed a TiN SPR chip to detect U251 glioma cells derived exosomes. The exosomes were initially isolated from the U251 cultured cell line using a standard isolation protocol combining centrifuge and filtration.135 The TiN surface was functionalized with exosomal protein CD63 and EGFRvIII specific antibodies (ABs). The device reported a very low LOD of 4.29 ng/ml for CD63 exosome marker and 2.75 ng/ml for EGFRvIII exosome marker and was able to sensitively detect exosomes derived from mouse serum. The slope of the calibration curve was about 0.36 for CD63 and 1.601 for EGFRvIII, with dynamic range extending up to 500 μg/ml, as shown in Fig. 2. The paper also reported that the TiN sensor has almost twice the sensitivity when compared to a traditional Au sensor, and a 15% improvement in LOD. The increase in sensitivity, however, can be reasoned by taking into consideration the direct and indirect functionalization standards used for TiN and Au surfaces, respectively.

FIG. 2.

Schematic illustration of (a) functionalization of TiN surface with anti-CD63 ABs for detection of U251 glioma-derived exosomes, (b) SPR response of the TiN-anti-CD63 biosensor and (c) its sensor calibration curve for detection of exosomal protein CD63. (d) Sensor calibration curve for detection of exosomal protein EGFRvIII. Reprinted with permission from Qiu et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1806761 (2019). Copyright 2019 John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

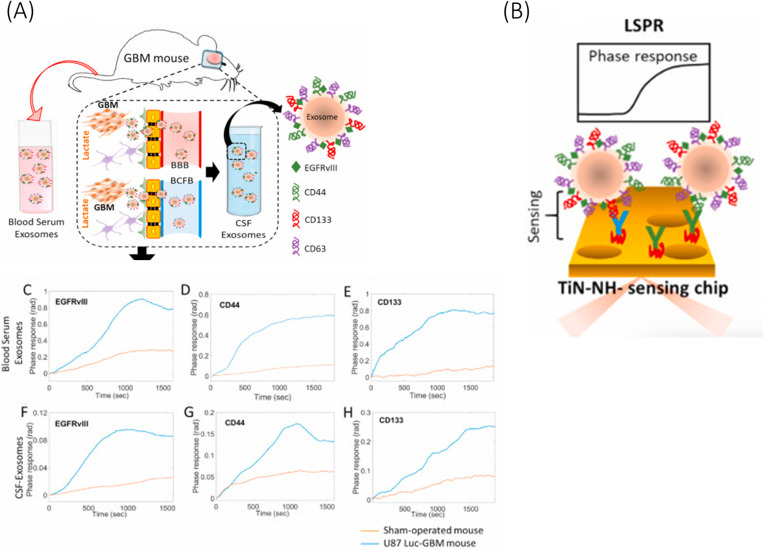

Nanostructures of a size equivalent to the wavelength of light can facilitate far more sensitive detection of biomarkers via confinement of surface plasmon, also known as localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR). Thakur et al.136 reported a modified version of their previous TiN SPR chip134 by introducing nanoholes on the surface of TiN nanofilm (Fig. 3). This allowed for localization and amplification of the surface electromagnetic wave. The sensor was functionalized with specific ABs for EGFRvIII, CD44, and CD163, respectively, and showed high sensitivity toward exosomal surface protein CD44 with a very low LOD of 3.46 ng/ml and the calibration curve slope of 1.447. Each biomarker was required to be isolated with individual pre-processing steps from the cultured cell line. Moreover, the paper demonstrated that the biosensor was able to quantify major glioma biomarkers isolated from the CSF and blood serum (with the help of a Total Exosome Isolation kit135) of a GBM mouse model, which is a potential development toward liquid biopsy.

FIG. 3.

Schematic illustration of (a) exosomes derived from the blood serum and CSF of a GBM mouse model and (b) its ultrasensitive detection using TiN nanohole LSPR biosensor. SPR phase response of the biosensor for exosomes derived from [(c)–(e)] blood serum and [(f)–(h)] CSF, [(c) and (f) for EGFRvIII, [(d) and (g)] for CD44, and [(e) and (h)] for CD163. Reprinted with permission from Thakur et al., Biosens. Bioelectron. 191, 113476 (2021). Copyright 2021 Elsevier.

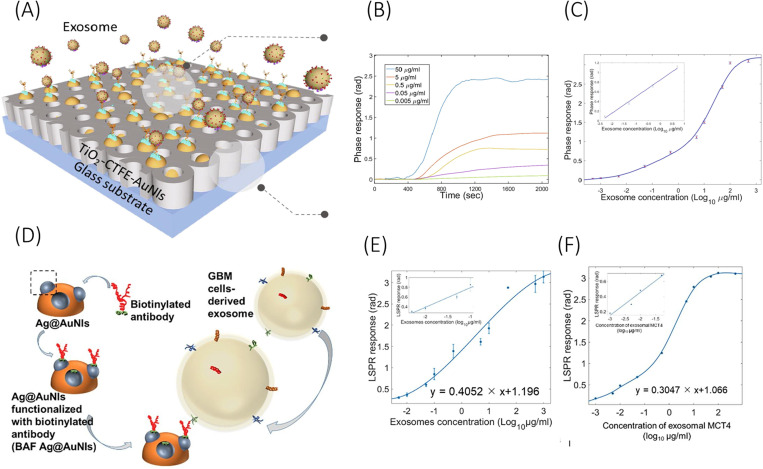

Nanoparticle enabled LSPR biosensors have also been explored in recent times. Thakur et al.135 reported a biosensor surface by self-assembled gold nanoislands (AuNIs) over the SiO2 surface. This sensor surface was utilized in one of their later publications124 for label-free quantification of exosomal surface protein CD147 and MCT1. The exosomes were derived from the blood serum of a glioma mouse model following standard protocols.135 A later publication from the same group modified the AuNIs surface of the biosensor by integrating TiO2-columnar thin films (TiO2-CTFE-AuNI).137 This device couples TiO2 with gold nanoislands for improved sensitive detection of exosomal surface protein CD63 and glioma biomarker BIGH3 (also known as TGFB1) [Fig. 4(a)]. The device functionalized with respective ABs reported a LOD of 4.24 ng/ml for CD63 and 3.84 ng/ml for BIGH3. With respect to only AuNIs, the integration of TiO2 improved the LOD by 13% and increased the sensitivity (calibration curve slope) by almost 2.5 times.

FIG. 4.

Schematic representation of (a) TiO2-CTFE-AuNI sensing chip and its (b) LSPR phase responses against BIGH3 protein from glioma-derived exosomes, and (c) sensor calibration curve. (d) Schematic illustration of the Ag@AuNI chip functionalized with anti-MCT4 antibodies along with their calibration curves for detection of MCT4 protein from (e) U87 derived exosomes and (f) blood serum derived exosomes. Schemes (a) and (c) are reprinted with permission from Xu et al., Chem. Eng. J. 415, 128948 (2021). Copyright 2021 Elsevier. Schemes (d)–(f) are reprinted with permission from Liu et al., Chem. Eng. J. 446, 137383 (2022). Copyright 2022 Elsevier.

In the report by Liu et al.,138 an LSPR chip is demonstrated by integrating Ag nanostructures over self-assembled Au nanoislands [Fig. 4(d)]. The Ag@AuNI chip functionalized with anti-CD63 and anti-MCT4 antibodies reported a very low LOD of 0.38 and 1.4 ng/ml, respectively, which is almost 75% improvement over only AuNI LSPR chip. The sensitivity of the device (slope of the calibration curve) is also improved by over 1.5 times. The device detected elevated levels of GBM biomarker exosomal protein MCT4 derived from the blood samples of a GBM mouse model with a remarkable LOD of 0.4 ng/ml. Such devices have proven to attain remarkable sensitivity for pre-processed samples with isolated exosomes, but may not be specific enough to work under complex real biofluids such as blood or CSF.

LSPR based biosensing has been implemented for microRNA detection as well. Hao et al.139 reported a highly sensitive LSPR chip based on gold nanorods. The complementary target sequence used in the sensogram experiments matches with miR-16-5p (sequence data found in miRbase140), which has been reported to be a tumor suppressor and found downregulated in glioma.141,142 The device demonstrated a LOD of 0.045 pM with the Au nanorods, which increases to 0.054 nM without the Au nanorods. The streptavidin functionalized Au nanorods can interact with the 3′ biotin of the molecular beacon receptor probe only after the microRNA hybridizes with the probe and removes the steric hindrance. The report does not present any test with real biofluids or biomarkers isolated from them.

SPR and LSPR biosensors show great promise toward clinical application with certain limitations like long pre-processing steps, lack of multiplex analysis, and low-throughput that are still required to be worked on.

B. Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy

Raman scattering occurs due to the interaction of a photon with a matter by either losing energy to a molecule, which gets promoted to its first excited vibrational state, or gaining energy from a molecule, thereby sending it back to the ground state.143 When a molecule absorbs the photon energy, it gets promoted to a virtual energy level corresponding to the wavelength of the exciting light. Upon re-emission, the molecule comes down to either a higher (Stokes scattering) or lower vibrational energy state (anti-Stokes scattering) with respect to the initial state or to the same vibrational energy state (Rayleigh scattering).144 The Raman effect directly probes into the vibrational states in a molecule and, thus, can be applied in various fields including chemical and biological sensing. However, spontaneous Raman scattering is a very weak phenomenon.145 The presence of nanostructures on the surface can significantly amplify the intensity of Raman signals through excitation of localized surface plasmons. This phenomenon is known as surface-enhanced Raman scattering or SERS. The amplification can range between 1010 and 1011, which can even allow detection at a single molecule level.146

Jalali et al.147 reported a biosensing platform based on Raman spectroscopy for detection of extracellular vesicles extracted from two different GBM cell lines—U373 and U87. Extraction was performed with a standard pre-processing protocol.148 The nanostructure implemented in the device was an optimized gold nanobowtie, which showed an enhancement factor of in average electric field. A microfluidic device is integrated with the SERS chip for effecting the loading of EVs and multiplexed detection of two EV types. The device demonstrated a LOD of 1.32 × 105 particles/ml over a linear range of 105–108 particles/ml. Another study by Kim et al.149 demonstrated a sandwich assay for sensitive and multiplexed detection of microRNAs—21, 10b, and 373. The microRNAs were isolated from a cancer cell line using an RNeasy Mini Kit. The SERS chips used head-flocked gold nanopillars for LSPR enhancement. The sandwich assay consists of two single stranded DNA probes—capture and detection probes, and the combined one forms the complementary sequence of the target miRNA. The detection probe plays a significant role in identifying the fingerprint peak of the target microRNA.150 The biosensor reported a LOD of 3.53 fM for miR-10b, 2.17 fM for miR-21, and 2.13 fM for miR-373. The study, however, used PBS as a substrate, indicating that the biosensor may fall short when concerned with real biofluids.

SERS biosensing technique is often limited by its low-throughput analysis due to time consuming spectral acquisition. Other than that, benchtop Raman detectors are bulky and required to be maintained at very low temperatures, making them costly and unsuitable for point-of-care applications. In recent times, Raman spectrometers have been efficiently miniaturized to handheld devices with detectors working under room temperature. Such devices are suitable for point-of-care applications and gained attention in the sensor research community.151 SERS integrated with microfluidic devices can be implemented for clinical liquid biopsies, where microfluidic platforms may allow high-throughput, multiplexed, and automated analysis, while SERS biosensing platform allows ultrahigh sensitive detection of clinical biomarkers. Integration of nanoparticle-based SERS biosensing platform with microfluidics can be done by immobilizing nanoparticle/ nanostructures on the microfluidic channels/chambers. Such devices can be operated in both static and continuous flow manner; however, care needs to be taken for control of injection flow, mixing of target molecules, and reaction time.152,153 Another strategy is segmented flow with microdroplet based strategies, where each microdroplet consists of target biomolecules and colloid nanoparticles. In this strategy, each droplet acts as individual reaction sites and prevents the memory effect or adsorption of nanoparticles.154,155

IV. ELECTROCHEMICAL BIOSENSORS FOR GLIOMA

Electrochemical biosensors are commonly referred to as electroactive surfaces, typically a biorecognition layer over an electrode that transduces the biochemical activity over the surface in form of electric signals. An electrochemical biosensor usually consists of three electrodes. A working electrode (WE) is where all the biorecognition reaction and chemical to electrical transduction takes place. A reference electrode (RE) which sits in the solution but at a distance from the reaction surface and provides a constant potential (measurement normal) proportional to the solution. Lastly, the auxiliary electrode (AE) which is the source of current to the working electrode.156 RE and AE are required to be conductive and stable.

Electrochemical biosensors are very attractive for point-of-care applications owing to simple design parameters, compatibility with electronics, and potential for miniaturization. These biosensors also provide detection of ultra-low analyte concentration within a very low settling time. Depending on measurement techniques, there are a few categories of electrochemical biosensing such as voltammetry, amperometry, and impedimetry.

In voltammetric measurements, the potential on the WE is varied within a certain range with respect to RE and the current between the WE and AE is monitored. Types of voltammetric techniques are as follows: Cyclic voltammetry (CV)—where the potential is varied in a ramp fashion between two potential values back and forth to find the current–voltage hysteresis curve during a redox reaction. CV measurements usually get affected by non-Faradaic currents, which lowers the overall sensitive detection.157 Differential pulse voltammetry (DPV)—where a pulsed potential of constant amplitude but varying dc base value after each pulse is applied at the WE and the current measurements are taken at two periods in time, just prior to the application of pulse and at the end of the pulse. These sampling periods are selected to allow the non-Faradaic currents to decay. The difference in the two current values with respect to the voltage forms the DPV curve with the peak height proportional to the concentration of the analyte. Square wave voltammetry (SWV)—where the potential pulses applied at the WE are similar to DPV, but the current is sampled at two time periods, one at the forward pulse and one at the reverse pulse. The SWV plot also depicts the difference in two sampled current with respect to voltage. SWV offers certain advantages over CV as the difference in two sampled current reduces the measurement of background (charging) current. SWV is often preferred over DPV as well due to its lower sweeping time, resulting in a faster scan and thus, higher sensitivity.

Amperometry measurements are simpler than voltammetry, where the WE is applied with a constant potential and the generated current is observed, which is a function of the redox reaction. Impedimetric measurements are useful when analyte–ligand reaction process changes certain resistive or capacitive properties of the electrochemical system. Electrochemical impedimetric spectroscopy (EIS) is a measurement of current response to an applied electric voltage, where the frequency of the voltage is varied, to probe the variation of complex impedance of the system.

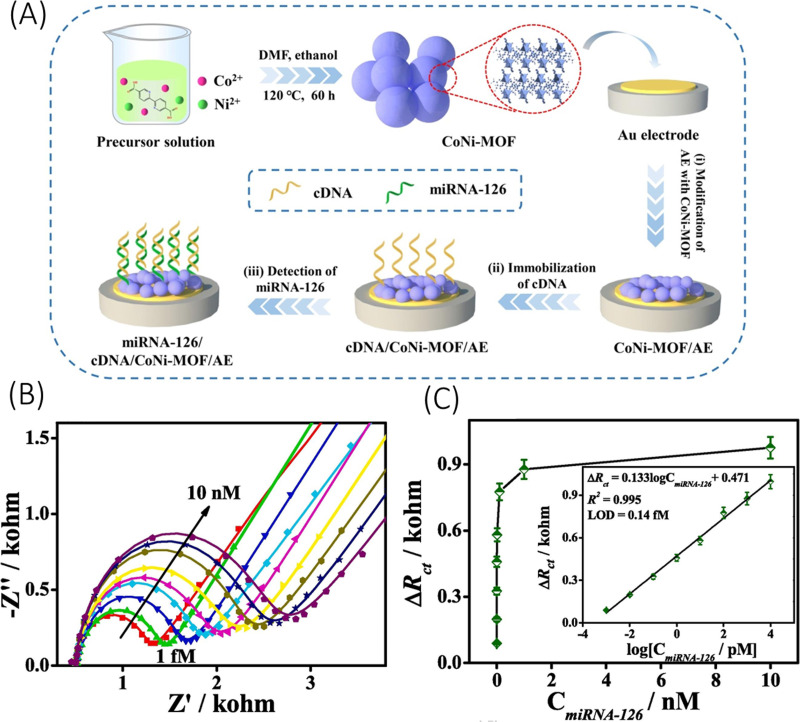

Several literatures have reported a sensitive detection of glioma biomarkers using one or more of the different electrochemical biosensing techniques. For instance, Ganganboina et al.159 recently reported an electrochemical biosensor for sensitive quantification of glioma cells derived from human serum, where isolation of glioma cells required certain pre-processing steps. Herein, they prepared a complex nanocomposite consisting of sulfur doped graphene quantum dots deposited over gold nanoparticles decorated carbon nanosphere, which served the dual role of enhancement of electrochemical activity and conjugation of angiopep-2, a receptor for lipoprotein receptor protein 1 (LRP1) expressed abundantly on glioma cell surface. Using EIS over glioma cells derived from human serum, the biosensor reported a very low LOD of 40 cells/ml over a linear range of 100–100 000 cells/ml. The device, while showing great sensitivity toward glioma cell, still requires isolation of glioma cells from human serum. Another interesting study by Hu et al.158 implemented a bimetallic (Co and Ni) metal organic framework (MOF) over a gold electrode for miRNA-126 detection expressed in rat C6 glioma cells. The MOF probes were optimized at Co: Ni = 1:1 for an enhanced electrochemical response in comparison to monometallic MOF. The complementary DNA (cDNA) strands as miRNA receptors were immobilized over the MOF through metal binding with cDNA strands, as illustrated in Fig. 5(a). Using EIS, the sensor demonstrated a LOD of 0.14 fM with a linear range of 1 fM–10 nM [Fig. 5(c)] and a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of 3. The study, however, used synthetic miRNAs for testing and, thus, miRNAs extracted from cultured cell line or real biofluids may show a reduced sensor performance. A similar method using bimetallic MOF was also reported by Guo et al.160 Herein, the MOF was made up of Cu and Ni and have a graphene-like 2D structure. The metal centers exhibited mixed valences (Cu0/Cu+/Cu2+ and Ni2+/Ni3+), which endowed for electrochemical signal amplification. Using aptamer as a probe, the biosensor detected the presence of C6 glioma cells and EGFR in human serum samples. Different concentrations of C6 glioma cells and EGFR were added to real human serum samples via standard addition. Analysis using EIS and CV techniques demonstrated a LOD of 0.72 fg/ml for EGFR 21 cells/ml for C6 glioma cells. The applicability of such devices under complex real fluids like serum is very promising.

FIG. 5.

(a) Illustration of the fabrication process of CoNi-MOF based biosensor for miR-126 detection. (b) EIS Nyquist plots for detection of miRNA-126 at different concentrations (1 fM–10 nM) and (c) calibration curve of the CoNi-MOF based biosensor with the inset as the linear fit with respect to logarithm of miR-126 concentration. Reprinted with permission from Hu et al., Appl. Surf. Sci. 542, 148586 (2021). Copyright 2021 Elsevier.

Sun et al.161 demonstrated an electrochemical biosensor with peptide as a receptor. A designed peptide (H−C-acp-acp-FALGEA-NH2) is assembled for recognition of exosomal protein EGFR and EGFRvIII derived from GBM. Isolation of exosomes was done using a differential centrifuge method. The biosensor used methylene blue (MB) attached to Zr-MOF for electrochemical signal amplification. EIS and SWV analysis revealed a LOD of 7.83 × 103 particles/μl with a linear range of 9.5 × 103–1.9 × 107 particles/μl. The biosensor demonstrated high accuracy of GBM detection when tested with clinical samples. In detail, lower SWV currents were observed for samples taken post-surgery than their presurgical values. Another study by Wang et al.162 also used MB for sensitive detection of miR-21 extracted from CSF of medulloblastoma patients using target-induced redox signal amplification. The CSF samples were centrifuged initially before diluting with 40-fold PBS solution for biosensing analysis. Herein, partial cDNAs were immobilized over AuNPs loaded over a glassy carbon electrode. When the target attaches with the partial cDNA, the unhybridized part of the target miR hybridizes with a guanine-rich auxiliary strand. This auxiliary strand acts as a binder for methylene blue near the sensor surface. With DPV technique, the sensor demonstrates a LOD of 56 fM and a SNR value of 3. Such biosensors can be applicable for human CSF samples as well.

Amperometry technique has been implemented by Scoggin et al.163 and Poorahong et al.164 for sensitive detection of metabolic biomarkers glutamate (Glu) and α-ketoglutarate (αKG), respectively. Scoggin et al.163 observed the real-time glutamate uptake of CRL-2303 glioma cells with respect to normal astrocytes cell as control. The biosensor consists of platinum microelectrode array immobilized with glutamate oxidase (GlOx). GlOx catalyzes Glu into αKG, ammonia, and H2O2, which again oxidizes over the Pt electrode to release two electrons. Thus, the current value is directly correlated to the Glu concentration. The biosensor showed a LOD of 6.3 ± 0.95 μM in the basal media and 0.16 ± 0.02 μM in PBS buffer. While such devices show good sensitivity under pathological conditioned cell cultures, isolation of metabolites for liquid biopsy usually requires long pre-processing steps. Poorahong et al.164 reported a similar device for αKG detection. The device consists of carbon fiber electrode with immobilized glutamate dehydrogenase (GluD). The device surface was further modified with ruthenium–rhodium nanoparticles. GluD catalyzes αKG into L-glutamate in the presence of β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) and ammonia. The quantification of αKG is done by the detection of depleted NADH (NAD+). Amperometric measurements revealed a LOD of 20 μM with a linear range of 100–600 μM and a sensitivity of 42 μA/M. The study only showed sensor performance under PBS solution and may not hold up against complex matrices like serum and plasma.

A summary of different electrochemical biosensors implemented for detection of glioma biomarkers is enlisted in Table III.

TABLE III.

Summary of electrochemical biosensors for detection of glioma biomarkers.

| Analysis technique | Characteristics | Biomarkers | Specimen | LOD | Linear/dynamic range | SNR | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EIS on glassy carbon electrode | Complex nanocomposite | Glioma cells | Glioma cells diluted in PBS solution and 10% human serum solution. | 40 cell/ml | 100–100 000 cells/ml (linear) | … | Ganganboina et al.159 |

| EIS on Au electrode | CoNi bimetallic MOF | microRNA 126 | miR-126 extracted from rat glioma C6 cells. | 0.14 fM | 1 fM–10 nM (linear) | SNR = 3 | Hu et al.158 |

| EIS and CV on Au electrode | Graphene-like 2D CuNi MOF. Aptamer as receptor. | C6 glioma cells and EGFR. | C6 glioma cell extracted from human serum samples. | EGFR: 0.72 fg/ml C6 glioma cells: 21 cells/ml | EGFR: 1 fg/ml–1 ng/ml (dynamic) C6 glioma cells : 50 cells/ml–105 cells/ml (dynamic) | … | Guo et al.160 |

| EIS and SWV on Au electrode | Peptide as receptor. Zr-MOF with MB. | EGFR and EGFRvIII on GBM-derived exosomes | GBM-derived exosomes in Tris-HCL solution | 7.83 × 103 particles/μl | 9.5 × 103–1.9 × 107 particles/μl (linear) | … | Sun et al.161 |

| DPV on glassy carbon electrode | Target-induced electrochemical redox amplification (e-TIRSA) | microRNA-21 | miR-21 extracted from CSF of medulloblastoma patients | 56 fM | 0.5–80 pM (dynamic) | SNR = 3 | Wang et al.162 |

| Amperometry on Ceramic-based Platinum microelectrode array | … | Glutamate | Glutamate uptake observed in cultured astrocytes (control) and CRL-2303 glioma cells (pathological condition) | 6.3 ± 0.95 μM in basal media 0.16 ± 0.02 μM in PBS buffer | 10–570 μM (linear) | … | Scoggin et al.163 |

| Amperometry on Carbon fiber electrode | Electrode doped with ruthenium–rhodium nanoparticles. | Alpha-ketoglutarate | … | 20 μM | 100–600 μM (linear) | … | Poorahong et al.164 |

V. ELECTRONIC BIOSENSORS FOR GLIOMA

Electronic biosensors can be considered a sub-category of electrochemical biosensors; however, the underlying transduction principle is very different. Electronic biosensors are often based on the principle of field effect transistors (FETs), fabricated in microelectronic technology. In a typical FET, the potential applied at the gate electrode modulates the conductivity, or more accurately carrier mobility, of the underlying channel. The modulation occurs primarily due to tuning of the electric field by the gate electrode, resulting in subsequent attractive or repulsive Coulombic interactions. FET based biosensors implement the same principle for detection of the target analyte. An electronic biosensor will replace the gate electrode of an FET with a biorecognition layer (ligands). Analytes binding with the receptor layer can modulate the channel conductance and, therefore, result in an amplified change in current.165,166 The underlying amplification of FET makes them highly sensitive to analyte concentration, even at a single molecule level.167 Along with their low settling time, low power consumption, and compatibility with MOS fabrication technology, electronic biosensors seem very promising for future clinical applications.

The most common type of FET based transducer reported for glioma detection is silicon nanowire (SiNW). It has been theoretically established that cylindrical nanowire structures have an inherent, substantial advantage over planar biosensors regarding the detection of ultra-low analyte concentration under reasonable settling time.168 The primary reason behind these orders of magnitude difference in LOD (pM vs nM) is due to the geometry of the biosensor itself. In a planar sensor, the analyte charges can influence the channel conductance from only one side, while in a cylindrical nanowire biosensor, the analyte can envelop the entire channel surface, thereby having a much higher influence over the channel conductivity.

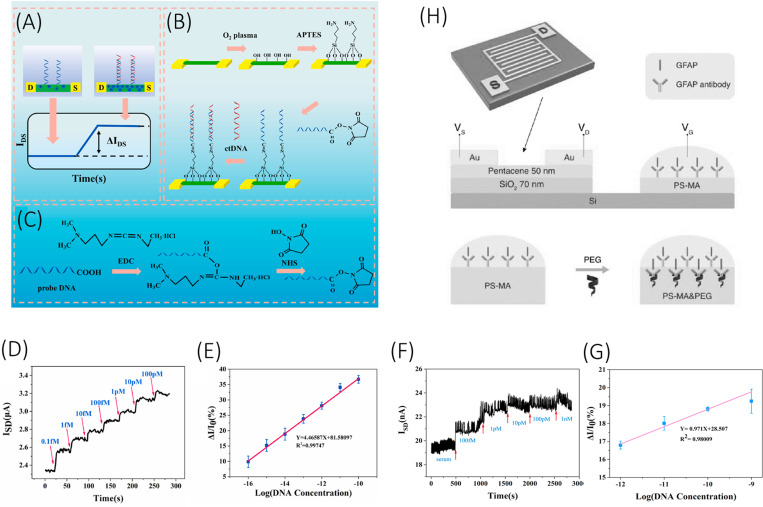

Malsagova et al.169 reported a high-k dielectric silicon-on-insulator (SOI) nanowire biosensor for detection of a synthetic analog of microRNA-21. Herein, complementary oligonucleotide probes were used as a receptor, which were covalently immobilized over the nanowire surface through the silanization process. High-k dielectric coating of Al2O3 (2 nm) and HfO2 (8 nm) was applied over the SOI nanowire for improved stability. The biosensor reported a very low LOD of 0.1 fM with only 10% alteration in the current value over 8 h of testing under K phosphate buffer. However, the paper did not report any tests with actual biofluids. Li et al.170 reported an array of 120 silicon nanowires for sensitive detection of tumor biomarker ctDNA. The specific gene target was PIK3CA E542K ctDNA, whose mutation plays a pivotal role in promoting GBM pathogenesis.171 The oligonucleotides of the ctDNA sequences were prepared synthetically. The paper reported a remarkable LOD of 10 aM over a linear range of 0.1 fM–100 pM when tested with ctDNA spiked in healthy human serum [Figs. 6(f) and 6(g)]. When tested with one or two base mismatched target sequences, the device reported a significant level of signal decrement, implementing the specificity of the device at a single nucleotide level. Such devices are very promising for high accuracy clinical applications as they can withhold real biological fluids. A similar silicon nanowire biosensor was reported by Wu et al.172 demonstrating the sensitive detection of BRAFV599E gene mutation (now designated as BRAFV600E),173 which is present in higher percentage in epithelioid GBMs.174 The 60 nm wide SiNW biosensor reported a LOD of 0.88 fM with a relative standard deviation (RSD) of only 12%. The target synthetic oligonucleotides in this study were tested only with PBS solution and not with any serum or plasma samples.

FIG. 6.

(a) Working principle of the SiNW-array FET biosensor. (b) Stepwise process of fabrication of SiNW-array FET biosensor. (c) Carboxyl groups activation by EDC/NHS. (d) The real-time response and (e) calibration curve of the SiNW-array FET biosensor for different concentrations of ctDNA. (f) The real-time response and (g) calibration curve of the SiNW-array FET biosensor for different concentrations of ctDNA in human serum. (g) Device architecture of the extended gate OFET biosensor for sensitive detection of GFAP. Schemes (a)–(g) are reprinted with permission from Li et al., Biosens. Bioelectron. 181, 113147 (2021). Copyright 2021 Elsevier. Scheme (h) is reprinted with permission from Song et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. 27, 1606506 (2017). Copyright 2017 John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Graphene FETs (gFET) have also been explored for biosensing applications owing to their high charge carrier mobility and high electronic sensitivity conveyed by surface charge.175,176 A typical gFET current–voltage characteristic consists of a current minimum at Dirac voltage point. Introduction of any charged species for partial coverage of the graphene surface shifts the Dirac voltage point proportional to the concentration of the species. Xu et al.177 demonstrated an on-chip monolayer graphene FET device for accurate quantification of metabolic biomarker GFAP derived from human plasma samples. The plasma samples were centrifuged and frozen prior to testing, but no isolation step is mentioned in the study. The on-chip gFET biosensor array contains two sensing areas, each with six gFET devices and one reference gold electrode integrated on chip for low power liquid-based gating. The sensing areas were immobilized with anti-GFAP antibodies. The LOD of the device is reported to be 400 aM when tested in buffer and 4 fM when tested with plasma. The sample-to-response time of the device was less than 15 min. On comparing the biosensor performance factors like sensitivity and response time against other standard quantification methods like single-molecule array (Simoa) and ELISA, it outperformed both of them. Another gFET device has been developed and reported by Ban et al.178 for direct DNA methylation profiling. The device incorporates a DNA tweezer probe, consisting of a normal strand and a weak strand, for sensitive detection of targeted gene. When the target gene comes near the vicinity of the probe, it hybridizes with the normal strand by displacing the weak strand due to its high binding affinity. At picomolar level concentration, the sensor was able to differentiate a non-methylated DNA from a methylated one with eight methyl cytosines (MDT8). The device also reported to differentiate between MDT2 and MDT2a and MDT2b, where the two cytosine groups are present at different locations, further demonstrating the high sensitivity of the biosensor to determine the position of methylation as well. Such biosensors can be applied for methylation screening of ctDNA derived from bodily fluids; however, biofluidic matrices may lower the screening efficiency.

Organic FETs (OFET) are also an interesting option for biosensing applications owing to their low-cost simple fabrication and biocompatibility with biofluids. Song et al.179 reported an extended gate OFET biosensor for sensitive detection of GFAP. The extended gate structure (gate far away from the transistor body) is often used in organic transistors to protect the organic layer from prolonged exposure and damage to moisture. A thin layer of pentacene has been used in this case as a p-type semiconductor as shown in Fig. 6(h). The extended gate structure is constructed with a PS-MA layer decorated with anti-GFAP antibodies and polyethylene glycol membrane (PEG). The significance of PEG in the biolayer is to address a key issue in electronic biosensing associated with the Debye screening length. The formation of a small electrical double layer (characteristic length ) on the surface of the biosensor shields the influence of charged biomolecules above the characteristic length, thereby reducing the sensitivity of the device and prohibiting its application under high salt concentration. The presence of negatively charged PEG at the biolayer extends the effective characteristic length of the double layer, thereby allowing detection of GFAP at higher PBS concentration. The device reported sensitive detection of GFAP at 0.1X PBS solution (∼15 mM) higher than the typical 0.01X PBS solution used for such applications. These devices can be applied directly to biological fluids, which usually consist of high salt concentration with minimal dilution. The sensor also reported a LOD of 1 ng/ml over a dynamic range of 0.5–100 ng/ml; however, the reported sensor performance was done at a lower gate voltage, which makes it susceptible to noise interference and lower SNR value. When tested against other proteins of similar size and charge, the device shows great specificity toward GFAP. Another study by Selvaraj et al.180 reported an electrolyte gated OFET with sensitivity toward miRNA-21-5p. The required oligonucleotide sequence is synthesized as per the miRNA-21-5p sequence. The device consists of two gold electrolyte gate electrodes, one immobilized with thiolated complementary probes (G2) and another with 2-Mercaptoethanol (ME) monolayer (G1). Before the OFET detection, G2 is first incubated in a buffer containing target analyte miR-21-5p. Upon testing the OFET driven by both gate electrodes separately, G2 showed a variation of OFET threshold voltage with different concentrations of target, while G1 acted as a control. This allows the differential response measurement between the sensing and reference electrodes. Upon testing, the device reported an excellent LOD of 35 pM over a dynamic range of up to 300 pM. Test with real biofluid may increase the LOD value obtained in this study.

A simple device consisting of aluminum interdigitated electrodes over a silicon wafer is recently reported by Li et al.181 for detection of microRNA-363. The oligonucleotide is synthesized as per miR-363 sequence. The interdigitated structure was fabricated using the standard photolithography process and complementary probes of miR-363 were immobilized over the electrodes using gold nanoparticles as the linker. The sensor working principle is based on the dipole moment between the two electrodes, where the ionic movements near the surface change the dipole moment upon molecular interaction. The device reported a LOD of 10 fM and showed good linearity over the range 1 fM to 100 pM, when tested with miR-363 spiked in human serum.

Electronic nanobiosensors can attain remarkable LOD at the attomolar level. However, fundamental problems like Debye screening length limitations and instability of silicon devices under different biofluids limit the application of such sensors, requiring further research targeting reliability of these devices. Table IV summarizes different electronic biosensors implemented for detection of glioma biomarkers.

TABLE IV.

Summary of electronic biosensors for detection of glioma biomarkers.

| Type of electronics | Biomarkers | Specimen | LOD | Linear/dynamic range | RSD | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOI nanowire coated with high k dielectric material | microRNA-21 | oDNA: synthetic analog of miR in K phosphate buffer | 10−16 M | 10−17–10−14 M | … | Malsagova et al.169 |

| Si Nanowire | PIK3CA E542K ctDNA | Oligonucleotides in PBS solution ctDNA spiked in human serum | In PBS:10 aM In serum sample: 10 fM | In PBS: 0.1 fM–100 pM (linear) In serum sample: 1 pM–1 nM (linear) | … | Li et al.170 |

| Si Nanowire | BRAFV599E (now designated as BRAFV600E) | Target DNA with respective mutation in PBS solution | 0.88 fM | 10 fM–100 pM (dynamic) | RSD: 12% | Wu et al.172 |

| Graphene FET | Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein (GFAP) | GFAP extracted from human blood samples and diluted in PBS | In buffer: 20 fg/ml (400 aM) In human plasma: 231 fg/ml (4 fM) | In buffer: 20–200 fg/ml (linear) In human plasma: 230 fg/ml–230 pg/ml (linear) | … | Xu et al.177 |

| Graphene FET | Methylation profiling | Methylated DNA in buffer solution. | … | … | … | Ban et al.178 |

| Extended Gate Organic FET | Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein (GFAP) | GFAP in 0.1X PBS solution | 1 ng/ml | 0.5–100 ng/ml (dynamic) | … | Song et al.179 |

| Dual Gate OFET | microRNA-21 | miR-21 in buffer solution | 35 pM | Up to 300 pM (dynamic) | … | Selvaraj et al.180 |

| Interdigitated electrode | microRNA-363 | miR-363 spiked in human serum samples | 10 fM | 1 fM–100 pM (linear) | … | Li et al.181 |

VI. FUTURE RESEARCH PERSPECTIVE

The detection and quantification of various biological markers related to cancer have undeniable significance in personalized medicine. Current biosensor-based detection technologies can provide high sensitivity toward a particular biomarker at an ultra-low analyte concentration, which is a promising step forward. They can outperform numerous standard biomarker detection technologies, like polymerase chain reaction (PCR), RTPCR, and ELISA. Depending on the type of application, these biosensors are required to pass certain criteria like high sensitivity, specificity, high-throughput multiplexed analysis before they can be applied to actual clinical platforms. Different biosensing applications include point-of-care (POC), liquid biopsies, and implantable devices. Current standing and future perspective of these biosensors based on the particular application have been described in Secs. VI A–VI C.

A. Point-of-care (POC) devices

POC devices are usually handheld devices, which can quickly detect the occurrence of a certain pathological condition by testing a biofluid directly or with minimum pre-processing. One of the most successful and widely available POC devices is the pregnancy test kit, which is a lateral flow assay based colorimetric sensor for quantified detection of hCG in urine samples. A POC device, in general, requires to be highly sensitive, reliable, rapid, portable and have the ability to detect analyte in a complex medium. It is also desirable to sample the medium in a minimally invasive manner. In terms of glioma, biomarkers were found from readily available biofluids like urine or saliva5 and can be used for POC applications. The required sensitivity and rapid detection can be achieved by optical biosensing; however, low signal intensity could increase the false positive rates. Electrochemical and electronic biosensors can also achieve very low LOD (at fM–aM level), rapid detection, and their compatibility with CMOS fabrication systems also allows cost reduction and swift miniaturization, making them a promising candidate for POC applications. However, certain fundamental problems in electronic biosensors such as Nernst limit, Debye screening length, and degradation of silicon in the continuous presence of salt currently limit their reliability and, thus, practical applications. Nonetheless, their ability for ultra-low aM level detection still makes them an attractive option.

B. Liquid biopsy

Liquid biopsy is a very helpful tool in cancer management by allowing a dynamic view of the tumor prognosis, specifically for glioma where tissue biopsies are often positionally complicated. Biosensor technologies can allow liquid biopsies to be a point-of-care treatment option. Simultaneous analysis of multiple biomarkers in real time is an urgent requirement in glioma management process and can be achieved using multiplexed biosensing. Most current biosensors are designed for detection of only a couple of biomarkers at most. However, a larger amount of information can be collected from single sample through multiplexing. For accurate detection and prognosis of glioma, multiplexing is necessary as multiple biomarkers with low predictive co-efficient can be combined to achieve better precision, resulting in personalized medical treatment and overall better management of disease. Microfluidic biosensors hold great promise in terms of high-throughput multiplexed analysis. It integrates the sensitive detection of biomarkers via electrochemical or electronic biosensing platforms with microfluidic separation and mixing techniques. Microfluidics-based lab-on-chip devices open a new direction in designing novel approaches for multiplexed, scaled-down automated biosensors for monitoring of glioma. These platforms can also be explored to study how different biomarkers affect the prognosis of cancer at different stages, thereby improving our understanding of cancer-related processes. Overall, POC based liquid biopsy platforms require multiplexed, high-throughput biomarker analysis, which have not been achieved with a single biosensor platform, but can be implemented by integrating microfluidic technologies with it.

C. Implantable devices

Implantable devices are a moon-shot target for current biosensor technology due to a plethora of limitations ranging from continuous monitoring to biofouling. Taking the simpler problem first, continuous monitoring of biomarkers has not been explored much in the literature. A biosensing device dies after a certain number of uses due to saturation of available receptor probes on the surface, thus requiring surface regeneration or cleaning via external methods like flushing. Some receptor–analyte bonds like antibody–antigen are so strong that they cannot be separated in some cases even with flushing. However, an implantable biosensor is required to have a longer lifetime, thus having the ability to auto-clean its surface is essential. A recent study by Fercher et al.182 showed that this can be achieved in antibody–protein interaction by changing the antibody protein sequence at specific binding sites. This allows the antibody to have a weakened interaction with the target protein, thereby allowing reversible reaction between them. The key is to increase the reverse rate constant without affecting the forward rate much. Such approaches are easier to implement in nucleic acid sequences due to their sequence simplicity and can be used to design specific receptors for implantable biosensors. This could lead to a great first step toward implantable biosensors, which can revolutionize the current medical system.

VII. SUMMARY

This literature review covers the recent advances made for label-free detection of various glioma biomarkers and to the best of our knowledge, it is the first review targeting glioma biosensors. Given the relative rarity of glioma in comparison to other forms of cancer like lung cancer and breast cancer, the reported number of literatures related to glioma biomarker detection was also less. However, given the poor prognosis and survival rate, glioma biosensors should be of given greater importance. In this review, we reported key literatures from different peer-reviewed journals that made significant development in glioma detection. We explored different biosensing schemes ranging from optical, electrochemical, and electronics and analyzed their pros and cons in perspective of future research direction. We also did a brief literature survey analyzing the plethora of biomarkers reported to be associated with glioma and summarized a few important of them based on their frequency in available papers. Overall, current biosensors have demonstrated significantly high sensitivity and specificity with ability to detect biomolecules at ultra-low concentration; however, certain other characteristics such as stability, multiplexing, and specificity under real biofluids are still some of the few problems that need to be worked on before they can be applied on clinical fields. We concluded our review with a short perspective of future research specific to different application fields. It is expected that this review will assist researchers to have a better understanding of the current state-of-the-art biosensing platforms and motivate them to develop novel approaches for biosensing glioma biomarkers for better diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutics.

AUTHOR DECLARATIONS

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Author Contributions

Soumyadeep Saha: Conceptualization (equal); Writing – review & editing (equal). Manoj Sachdev: Conceptualization (equal); Writing – review & editing (equal). Sushanta K. Mitra: Conceptualization (equal); Writing – review & editing (equal).

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ostrom Q. T. et al. , “CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2012-2016,” Neuro-Oncology 21, v1–v100 (2019). 10.1093/neuonc/noz150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.See https://cancer.ca/en/research/cancer-statistics/cancer-statistics-at-a-glance for “Cancer Statistics at a Glance” (2022).

- 3.Hanif F., Muzaffar K., Perveen K., Malhi S. M., and Simjee S. U., “Glioblastoma multiforme: A review of its epidemiology and pathogenesis through clinical presentation and treatment,” Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 18, 3–9 (2017). 10.22034/APJCP.2017.18.1.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.See https://cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/cancer-types/brain-and-spinal-cord/prognosis-and-survival/survival-statistics for Survival statistics for brain and spinal cord tumours (2022).

- 5.Müller Bark J., Kulasinghe A., Chua B., Day B. W., and Punyadeera C., “Circulating biomarkers in patients with glioblastoma,” Br. J. Cancer 122, 295–305 (2020). 10.1038/s41416-019-0603-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shankar G. M., Balaj L., Stott S. L., Nahed B., and Carter B. S., “Liquid biopsy for brain tumors,” Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 17, 943–947 (2017). 10.1080/14737159.2017.1374854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nieder C., Grosu A. L., Astner S., and Molls M., “Treatment of unresectable glioblastoma multiforme,” Anticancer Res. 25, 4506–4610 (2005). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delgado-López P. D., Riñones-Mena E., and Corrales-García E. M., “Treatment-related changes in glioblastoma: A review on the controversies in response assessment criteria and the concepts of true progression, pseudoprogression, pseudoresponse and radionecrosis,” Clin. Trans. Oncol. 20, 939–953 (2018). 10.1007/s12094-017-1816-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khanmohammadi A. et al. , “Electrochemical biosensors for the detection of lung cancer biomarkers: A review,” Talanta 206, 120251 (2020). 10.1016/j.talanta.2019.120251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Altintas Z. and Tothill I., “Biomarkers and biosensors for the early diagnosis of lung cancer,” Sens. Actuators, B: Chem. 188, 988–998 (2013). 10.1016/j.snb.2013.07.078 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arya S. K. and Bhansali S., “Lung cancer and its early detection using biomarker-based biosensors,” Chem. Rev. 111, 6783–6809 (2011). 10.1021/cr100420s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roointan A. et al. , “Early detection of lung cancer biomarkers through biosensor technology: A review,” J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 164, 93–103 (2019). 10.1016/j.jpba.2018.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang G. et al. , “Recent advances in biosensor for detection of lung cancer biomarkers,” Biosens. Bioelectron. 141, 111416 (2019). 10.1016/j.bios.2019.111416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Getachew S. et al. , “Perceived barriers to early diagnosis of breast cancer in south and southwestern Ethiopia: A qualitative study,” BMC Womens Health 20, 38 (2020). 10.1186/s12905-020-00909-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hasanzadeh M., Shadjou N., and de la Guardia M., “Early stage screening of breast cancer using electrochemical biomarker detection,” Trends Anal. Chem. 91, 67–76 (2017). 10.1016/j.trac.2017.04.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ranjan P. et al. , “Biosensor-based diagnostic approaches for various cellular biomarkers of breast cancer: A comprehensive review,” Anal. Biochem. 610, 113996 (2020). 10.1016/j.ab.2020.113996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mittal S., Kaur H., Gautam N., and Mantha A. K., “Biosensors for breast cancer diagnosis: A review of bioreceptors, biotransducers and signal amplification strategies,” Biosens. Bioelectron. 88, 217–231 (2017). 10.1016/j.bios.2016.08.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghorbani F., Abbaszadeh H., Dolatabadi J. E. N., Aghebati-Maleki L., and Yousefi M., “Application of various optical and electrochemical aptasensors for detection of human prostate specific antigen: A review,” Biosens. Bioelectron. 142, 111484 (2019). 10.1016/j.bios.2019.111484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan K. M., Gleadle J. M., O’Callaghan M., Vasilev K., and MacGregor M., “Prostate cancer detection: A systematic review of urinary biosensors,” Prostate Cancer Prostatic Diseases 25, 39–46 (2022). 10.1038/s41391-021-00480-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Healy D. A., Hayes C. J., Leonard P., McKenna L., and O’Kennedy R., “Biosensor developments: Application to prostate-specific antigen detection,” Trends Biotechnol. 25, 125–131 (2007). 10.1016/j.tibtech.2007.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh S., Gill A. A. S., Nlooto M., and Karpoormath R., “Prostate cancer biomarkers detection using nanoparticles based electrochemical biosensors,” Biosens. Bioelectron. 137, 213–221 (2019). 10.1016/j.bios.2019.03.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atkinson A. J. et al. , “Biomarkers and surrogate endpoints: Preferred definitions and conceptual framework,” Clin. Pharmacol. Therap. 69, 89–95 (2001). 10.1067/mcp.2001.113989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Group F.-N. B. W., BEST (Biomarkers, Endpoints, and Other Tools) Resource 2016 (U.S. FDA, Silver Spring, MD, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allard W. J. et al. , “Tumor cells circulate in the peripheral blood of all major carcinomas but not in healthy subjects or patients with nonmalignant diseases,” Clin. Cancer Res. 10, 6897–6904 (2004). 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuhn P. and Bethel K., “A fluid biopsy as investigating technology for the fluid phase of solid tumors,” Phys. Biol. 9, 010301 (2012). 10.1088/1478-3975/9/1/010301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heitzer E., Haque I. S., Roberts C. E. S., and Speicher M. R., “Current and future perspectives of liquid biopsies in genomics-driven oncology,” Nat. Rev. Genet. 20, 71–88 (2019). 10.1038/s41576-018-0071-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Siravegna G., Marsoni S., Siena S., and Bardelli A., “Integrating liquid biopsies into the management of cancer,” Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 14, 531–548 (2017). 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller A. M. et al. , “Tracking tumour evolution in glioma through liquid biopsies of cerebrospinal fluid,” Nature 565, 654–658 (2019). 10.1038/s41586-019-0882-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolburg H., Noell S., Fallier-Becker P., MacK A. F., and Wolburg-Buchholz K., “The disturbed blood-brain barrier in human glioblastoma,” Mol. Asp. Med. 33, 579–589 (2012). 10.1016/j.mam.2012.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen Z. and Hambardzumyan D., “Immune microenvironment in glioblastoma subtypes,” Front. Immunol. 9, 1004 (2018). 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao C., Wang H., Xiong C., and Liu Y., “Hypoxic glioblastoma release exosomal VEGF-A induce the permeability of blood-brain barrier,” Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 502, 324–331 (2018). 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.05.140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bartel D. P., “MicroRNAs: Genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function,” Cell 116, 281–297 (2004). 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00045-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kamińska K. et al. , “Prognostic and predictive epigenetic biomarkers in oncology,” Mol. Diagn. Therapy 23, 83–95 (2019). 10.1007/s40291-018-0371-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baraniskin A. et al. , “Identification of microRNAs in the cerebrospinal fluid as biomarker for the diagnosis of glioma,” Neuro-Oncology 14, 29–33 (2012). 10.1093/neuonc/nor169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang J., Che F., and Zhang J., “Cell-free microRNAs as non-invasive biomarkers in glioma: A diagnostic meta-analysis,” Int. J. Biol. Markers 34, 232–242 (2019). 10.1177/1724600819840033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.ParvizHamidi M. et al. , “Circulating miR-26a and miR-21 as biomarkers for glioblastoma multiform,” Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 66, 261–265 (2019). 10.1002/bab.1707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Song Y., He M., Zhang J., and Xu J., “High expression of microRNA 221 is a poor predictor for glioma,” Medicine 99, e23163 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Song Y., Zhang J., He M., and Xu J., “Prognostic role of MicroRNA 222 in patients with glioma: A meta-analysis,” Biomed. Res. Int. 2020, 4689689 (2020). 10.1155/2020/4689689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang Y. et al. , “Prognostic significance of MicroRNAs in glioma: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” Biomed. Res. Int. 2019, 4015969 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiang G. et al. , “Prognostic value of miR-21 in gliomas: Comprehensive study based on meta-analysis and TCGA dataset validation,” Sci. Rep. 10, 4220 (2020). 10.1038/s41598-020-61155-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shi L. et al. , “MiR-21 protected human glioblastoma U87MG cells from chemotherapeutic drug temozolomide induced apoptosis by decreasing Bax/Bcl-2 ratio and caspase-3 activity,” Brain Res. 1352, 255–264 (2010). 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gwak H. S. et al. , “Silencing of MicroRNA-21 confers radio-sensitivity through inhibition of the PI3K/AKT pathway and enhancing autophagy in malignant glioma cell lines,” PLoS One 7, e47449 (2012). 10.1371/journal.pone.0047449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gabriely G. et al. , “Human glioma growth is controlled by microRNA-10b,” Cancer Res. 71, 3563–3572 (2011). 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang W. et al. , “MiR-181d: Predictive glioblastoma biomarker that downregulates MGMT expression,” Neuro-Oncology 14, 712–719 (2012). 10.1093/neuonc/nos089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Westphal M. and Lamszus K., “Circulating biomarkers for gliomas,” Nat. Rev. Neurol. 11, 556–566 (2015). 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kahlert C. and Kalluri R., “Exosomes in tumor microenvironment influence cancer progression and metastasis,” J. Mol. Med. 91, 431–437 (2013). 10.1007/s00109-013-1020-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xu R. et al. , “Extracellular vesicles in cancer—Implications for future improvements in cancer care,” Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 15, 617–638 (2018). 10.1038/s41571-018-0036-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Quezada C. et al. , “Role of extracellular vesicles in glioma progression,” Mol. Asp. Med. 60, 38–51 (2018). 10.1016/j.mam.2017.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Osti D. et al. , “Clinical significance of extracellular vesicles in plasma from glioblastoma patients,” Clin. Cancer Res. 25, 266–276 (2019). 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Akers J. C. et al. , “miR-21 in the extracellular vesicles (EVs) of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF): A platform for glioblastoma biomarker development,” PLoS One 8, e78115 (2013). 10.1371/journal.pone.0078115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Figueroa J. M. et al. , “Detection of wild-type EGFR amplification and EGFRvIII mutation in CSF-derived extracellular vesicles of glioblastoma patients,” Neuro-Oncology 19, 1494–1502 (2017). 10.1093/neuonc/nox085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Skog J. et al. , “Glioblastoma microvesicles transport RNA and proteins that promote tumour growth and provide diagnostic biomarkers,” Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 1470–1476 (2008). 10.1038/ncb1800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shao H. et al. , “Protein typing of circulating microvesicles allows real-time monitoring of glioblastoma therapy,” Nat. Med. 18, 1835–1840 (2012). 10.1038/nm.2994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen W. W. et al. , “Beaming and droplet digital PCR analysis of mutant IDH1 mRNA in glioma patient serum and cerebrospinal fluid extracellular vesicles,” Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2, e109 (2013). 10.1038/mtna.2013.28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Choi B. D. et al. , “EGFRvIII-targeted vaccination therapy of malignant glioma,” Brain Pathol. 19, 713–723 (2009). 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2009.00318.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]