Abstract

To date, the COVID-19 pandemic has still been infectious around the world, continuously causing social and economic damage on a global scale. One of the most important therapeutic targets for the treatment of COVID-19 is the main protease (Mpro) of SARS-CoV-2. In this study, we combined machine-learning (ML) model with atomistic simulations to computationally search for highly promising SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors from the representative natural compounds of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Database. First, the trained ML model was used to scan the library quickly and reliably for possible Mpro inhibitors. The ML output was then confirmed using atomistic simulations integrating molecular docking and molecular dynamic simulations with the linear interaction energy scheme. The results turned out to show that there was evidently good agreement between ML and atomistic simulations. Ten substances were proposed to be able to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. Seven of them have high-nanomolar affinity and are very potential inhibitors. The strategy has been proven to be reliable and appropriate for fast prediction of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors, benefiting for new emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants in the future accordingly.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11030-023-10601-1.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, Inhibitors, Natural compounds, Machine learning, Molecular docking, Molecular dynamic simulations, Linear interaction energy

Introduction

Despite the availability of several vaccines, the current COVID-19 pandemic, caused by SARS-CoV-2, remains a main public health concern around the world [1–7]. The emergence of new strains with faster transmission and higher vaccine resistance continues to pose major challenges in fighting the pandemic. SARS-CoV-2 contains an RNA genome made up of 11 open-reading frames that code for about 20 distinct proteins. One of the most essential proteins during viral translation is the SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro), which digests polyproteins at eleven or more conserved cleavage sites to create diverse functional proteins that are important for the viral infection [8]. While its closely similar homologs in humans are lacking, the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro is largely preserved in the Coronaviridae family [9–11], making Mpro one of the most intriguing targets for the selection of antiviral medications to stop the spread and replication of SARS-CoV-2 [11–14]. Multiple studies have been conducted to identify the prospective inhibitors of the protease accordingly [7, 15–22].

So far, two types of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors have been described, namely FDA-approved medications proposed for COVID-19 treatment (drug repurposing) and peptidomimetic and non-peptidic compounds (small molecules) established as a result of studies of SARS-CoV Mpro and other viral/retroviral objectives. Interestingly, SARS-CoV-2 has been proven to be susceptible to a variety of peptidomimetic medicines that have been demonstrated to be effective against MERS and SARS-CoV. Because of their low intrinsic oral bioavailability, the first generation of peptidomimetic SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors is limited [23]. Notably, the next generation of peptidomimetic SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors, PF-07321332/ritonavir [24], has become the first oral antiviral tablet approved by the FDA for the treatment of mild-to-moderate COVID-19 in adults and pediatric patients.

The creation of a novel medicine may now be completed faster and cheaper thanks to the computer-aided drug design (CADD) method [25–28]. Through the use of molecular dynamic (MD) simulations, the ligand-binding free energy of a compound with the intended protein may be precisely calculated [25, 29]. Therefore, it is extremely beneficial to predict the ligand-binding free energy quickly and accurately in order to identify potential inhibitors [30, 31]. The issues were, thus, addressed based on a variety of physics- and knowledge-based strategies [32–39]. When compared to experimental data, it is clear that a combination of these methods typically establishes more accurate results than a single approach [34]. The machine-learning (ML) technique has recently been raised as an effective method to rapidly estimate the binding affinities of a large number of ligand candidates [40–43]. Physics-based techniques such as molecular docking and MD simulations can be employed to subsequently verify the ML outcome [34]. It is worth noting that the computational combination of molecular docking and MD simulations was validated on existing SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors and showed good agreement between estimated and observed binding free energies [31, 44]. Here, with the aim of better anticipating effective inhibitors, a hybrid strategy combining ML models with traditional atomistic simulations was applied [17, 28, 36]. First, a trained ML model [17] was utilized to estimate the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro-binding affinities of 1500 representative natural compounds from the Open National Cancer Institute (NCI) Database [45]. Atomistic simulations involving molecular docking and MD simulations with the linear interaction energy (LIE) scheme were then employed to confirm the binding free energy of the top-lead compounds proposed by the ML model. The promising inhibitors for SARS-CoV-2 Mpro proposed are anticipated to be very reliable and provide a basis for additional experimental investigations. The findings in this study might aid in the advancement of COVID-19 medication, providing a simple and effective method that can quickly screen the promising candidates as Mpro inhibitors to limit the spread of other SARS-CoV-2 variants or other dangerous infectious coronaviruses in the future.

Materials and methods

Structure of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro and Ligands

The crystal structure of SARS-COV-2 Mpro in monomeric form was retrieved from the protein data bank with the identity of 7JYC [46]. The structure of 1581 ligands was obtained from the NCI Diversity Set VII database named representative natural products available to be downloaded at https://wiki.nci.nih.gov/display/ncidtpdata/compound+sets.

ML model

A trained ML model utilizing the extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) [17] with the Python code available at https://github.com/nguyentrunghai/SARS-CoV-2Mpro_inhibitor_ML was used. Details of feature extraction, model training, selection, and testing can be found in our previous work [17]. Briefly, for training and testing, 451 and 120 compounds with half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50) to SARS-CoV-2 Mpro found in literature reviews were chosen at random, respectively. Model selection performance metrics include root-mean-square error (RMSE), Pearson’s, and Spearman’s correlation coefficients. A tenfold cross-validation technique was used to tune model hyperparameters. The Hyperopt library [47] was used to find optimal hyperparameter values that minimize mean-square error (MSE). To train the model, XGBoost libraries was utilized.

Molecular docking simulations

The AutoDock Vina (Vina) with modified empirical parameters [48, 49] was used to assess the binding poses and affinity of the tested ligands to SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. AutoDockTools [50] was employed to generate the receptor and ligand parameters. The docking grid center was chosen to be the native ligand center of mass. The grid size was set at Å3. Referring to prior work, the Vina parameter "exhaustiveness" was selected as the default value [51]. The docking pose with lowest binding energy was saved for subsequent MD simulations.

MD simulations

MD simulations were often carried out to confirm docking results [52–54]. GROMACS 5.1.5 [55] was used to simulate the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro+ligand system. The complexes were first parameterized using the general Amber force field (GAFF) [56] for ligands, TIP3P [57] for water molecules, and the Amber99SB-iLDN force field [58] for proteins and ions. The ligands were parameterized by using the AmberTools18 [59] and ACPYPE [59] methods. Quantum chemical calculations utilizing the B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level of theory with an implicit solvent ( = 78.4) were applied to determine the chemical details of the ligands. To describe the atomic charges of the ligands, the restrained electrostatic potential (RESP) approach was employed [56]. The complex of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro and ligand was then positioned inside a dodecahedron periodic boundary condition box with a size of nm3. Thus, the total number of atoms in the solvated complex is approximately 66,000 (1 Mpro, 1 ligand, 20,410 water molecules, and about 4 Na + ions).

The simulations were run using a 1.0 nm cut-off for nonbonded interaction. The electrostatic interaction was computed using the particle mesh Ewald method, whereas the van der Waals (vdW) interaction was determined using the cut-off approach. With the use of LINCS algorithm with the order of 4 [60], all bonds were restrained throughout simulations. The steepest descent method was first utilized to minimize the parameterized complex. The minimized complex was subsequently relaxed in simulations lasting 100 ps of NVT and NPT simulations. Here, the complex's atomic locations were constrained by a harmonic force with a 1000 kJ mol−1 nm−2 spring constant. The relaxed system was finally simulated over 50 ns of MD simulations. The simulation was repeated two times to ensure the sampling of calculations.

Linear interaction energy (LIE) calculation

The ligand-binding free energy, , was computed as the mean of vdW and cou interaction differences of inhibitor with its neighboring atoms over incorporation, i.e., the individual ligand in solvent (unbound state—denoted by subscript u) and the inhibitor in binding mode with the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (bound state—denoted by subscript b).

The coefficient , a constant, is associated with the alteration of the hydrophobic nature of the binding cleft conceding to various species of inhibitors, whereas coefficients and are rating parameters for nonpolar and polar interactions [61]. According to the previous work [31], the empirical parameters were selected as , , and .

Analysis tools

The ligand protonation states in MD simulations were calculated using the ChemAxon webserver (www.chemicalize.com). The root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of non-hydrogen atoms between experimental and docking poses was used to determine the docking success rate, or . The GROMACS tool "gmx rms" was used to calculate the RMSD value [55]. The Maestro-free version was utilized to create the diagram showing how SARS-CoV-2 Mpro and its ligand interact [62].

Results

ML model

Figure 1 depicts the computational procedure used in this study to estimate the binding affinity of natural chemicals to SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. The chemical fingerprints of natural molecules were developed as input for ML regression model which predicts the ligand-binding affinity of these compounds. Atomistic simulations, which include molecular docking and MD simulations involving the LIE equation, would then be used to confirm the binding poses and affinity of top-lead compounds. Finally, top-lead SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors were proposed.

Fig. 1.

Strategy scheme used to identify promising SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors. ML and atomistic calculations were used to determine possible inhibitors for SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. Candidate inhibitors predicted by a ML algorithm were docked to the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro active site using AutoDock Vina. During MD simulations, the binding process of ligands to Mpro was refined, and the binding free energy between two molecules was then computed via the LIE calculation [61]

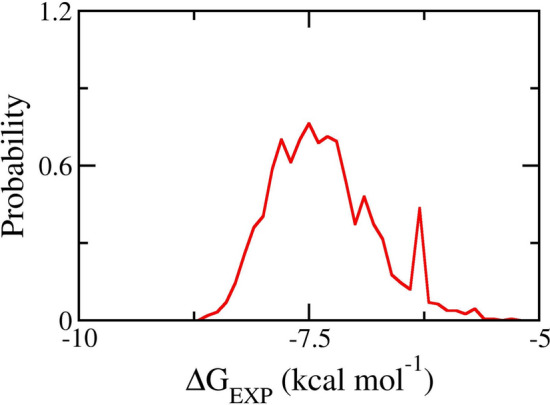

Previously, the XGBoost model [63] was shown to perform best in comparison to other models, such as linear regession, random forest, and convolutional networks on graphs in predicting the ligand-binding affinity for SARS-CoV-2 Mpro [17]. The model was trained from 451 compounds having to SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, which was obtained from literature reviews. The XGboost model adopted an RMSE of kcal mol−1 and correlation coefficient R of with respect to experimental values for 120 tested compounds [17]. In this study, the XGBoost model was, thus, employed to estimate the ligand-binding free energy of the representative natural compound set in the NCI database with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. Figure 2 depicts the distribution of binding free energy predicted by the ML model. In particular, the screening chemicals possessed the binding free energy ranging from − 5.28 to − 8.62 kcal mol−1, where the mean value was − 7.34 ± 0.56 kcal mol−1 with the error being the standard deviation.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of binding free energy of representative natural compounds predicted by XGBoost model

Docking and MD simulations

In order to gain physical insights into the binding process of ligands to Mpro, molecular docking and MD simulations were carried out accordingly. Ten compounds (see Table 1) with the lowest binding free energy predicted by XGBoost model were selected for further refinement using atomistic simulations. AutoDock Vina with the modified empirical parameters [48, 49] was first employed to estimate the binding poses of these top-lead chemicals. The modified Vina, which formed an appropriate success-docking rate of %, was indicated to possess a better performance compared to the original version, which adopted a success-docking rate of % [17]. It is worth to note that the modified Vina was proved to be appropriate to preliminarily establish the binding pose and affinity of ligands to SARS-CoV-2 Mpro [17]. The obtained binding pose between SARS-CoV-2 Mpro was mentioned in Figure S1 of the Supporting Information. Besides, the results indicated that the binding free energies obtained by molecular docking simulation were overestimated compared to ML calculations by an amount of 1.85 kcal mol−1 (Table 2). This difference may be due to the predicted binding affinity by the ML model being underestimated because the model was trained based on binding free energy approximately calculated from the experimental [17].

Table 1.

Top-lead compounds having the highest binding affinity to SARS-CoV-2 Mpro predicted by XGBoost model

| No | NSC ID | IUPAC name | (kcal mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1451 | N-benzyl-1-methylpyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4-amine | − 8.62 |

| 2 | 162,915 | 1-pyridin-4-yltriazolo[4,5-c]pyridine | − 8.59 |

| 3 | 23,247 | 3-[1-(4-methylphenyl)tetrazol-5-yl]pyridine | − 8.56 |

| 4 | 7867 | 6-chloro-N-(2-chlorophenyl)-1-methylpyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4-amine | − 8.55 |

| 5 | 55,770 | 4-chloronaphthalene-1-carboxamide | − 8.51 |

| 6 | 166,596 | 3-phenyl-6-thiophen-2-yl-[1,2,4]triazolo[3,4-b][1,3,4]oxadiazole | − 8.51 |

| 7 | 202,705 | 1-(2,1,3-benzothiadiazol-4-yl)-3-(4-chlorophenyl)urea | − 8.51 |

| 8 | 34,488 | N,N-dimethyl-9-phenylpurin-6-amine | − 8.50 |

| 9 | 19,123 | 6-chloro-1-methyl-N-(4-nitrophenyl)pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4-amine | − 8.45 |

| 10 | 379,639 | 5-amino-6-chlorotriazolo[1,5-a]quinazoline-3-carbonitrile | − 8.44 |

The calculated error is the standard error of the mean of four independent trajectories

Table 2.

The binding affinity of top-lead compounds to SARS-CoV-2 Mpro calculated by docking and LIE calculations

| N0 | NSC ID | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1451 | − 10.7 | 5.00 | − 15.67 | − 10.64 ± 0.26 |

| 2 | 162,915 | − 8.8 | 4.76 | − 11.18 | − 9.33 ± 0.05 |

| 3 | 23,247 | − 10.3 | 3.07 | − 14.04 | − 10.07 ± 0.39 |

| 4 | 7867 | − 10.6 | 7.62 | − 17.84 | − 11.39 ± 0.13 |

| 5 | 55,770 | − 8.6 | 1.39 | − 11.25 | − 9.19 ± 0.12 |

| 6 | 166,596 | − 11.8 | 2.57 | − 14.81 | − 10.27 ± 0.02 |

| 7 | 202,705 | − 11.2 | 6.56 | − 17.26 | − 11.17 ± 0.30 |

| 8 | 34,488 | − 10.3 | 6.28 | − 15.97 | − 10.79 ± 0.21 |

| 9 | 19,123 | − 11.6 | − 2.57 | − 15.35 | − 10.18 ± 0.27 |

| 10 | 379,639 | − 9.8 | 2.25 | − 11.24 | − 9.23 ± 0.19 |

Unit is kcal mol−1

Because Vina used the united-atom model, and the rigid receptor option was utilized during docking simulations. Moreover, the number of trial positions of ligands was also restricted. So, it is normally required that the docking results are refined via unbiased MD simulations [64–66]. MD simulation can establish more stable binding conformations compared to docking poses and help clarify the binding mechanism. During 50 ns of MD simulations, the solvated complex was relaxed to a stable conformation after 10 ns in both trajectories. The interaction-free energy of ligands to Mpro and the solution was, therefore, calculated over the interval 30–50 ns of MD simulations (Fig. 3 and Figure S2 of the Supporting Information). Besides, the ligand in solution system was also investigated to estimate the ligand-binding free energy via the LIE approach. The ligand in solution reached the equilibrium state after a half of the MD trajectory with a length of 5 ns (Fig. 3 and Figure S3 of the Supporting Information). The interaction-free energy between ligands and solution was computed over the interval of 2.5–5 ns.

Fig. 3.

RMSD of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro + NSC7867 complex (up) and ligand NSC7867 alone (bottom) in solution over 50 and 5 ns of MD simulation, respectively. Two different colored plot lines represent two distinct trajectories

Previously, the LIE approach [61] with the empirical parameters of the solvated Amyloid beta peptide system [67] was indicated to be able to accurately estimate the ligand-binding free energy of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. The obtained correlation coefficient was [31]. The difference in electrostatic and vdW interaction energies between an inhibitor and neighboring atoms in bound and unbound states were computed and the results are given in Table 2. The mean of the electrostatic gap was 3.85 ± 0.94 kcal mol−1, which diffuses in the range from − 2.57 to 7.62 kcal mol−1 (the error is the standard error of the mean). The obtained results imply that the hydrophobic interaction plays an important role in the binding process of a ligand to Mpro. This is consistent with vdW gap value ranging from − 17.84 to − 11.18 kcal mol−1 and having the mean value of − 14.82 ± 0.70 kcal mol−1. The binding free energy ranges from − 11.39 to − 9.19 kcal mol−1 with the mean value of − 10.33 ± 0.22 kcal mol−1. Interestingly, the RMSE between LIE and docking calculations was 0.79 kcal mol−1 with the correlation ecoefficiency was of R = 0.65, implying the consistency between the two methods. The obtained results nominated seven compounds with high-nanomolar affinity, including N-benzyl-1-methylpyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4-amine, 3-[1-(4-methylphenyl)tetrazol-5-yl]pyridine, 6-chloro-N-(2-chlorophenyl)-1-methylpyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4-amine, 3-phenyl-6-thiophen-2-yl-[1,2,4]triazolo[3,4-b][1,3,4]oxadiazole, 1-(2,1,3-benzothiadiazol-4-yl)-3-(4-chlorophenyl)urea, N,N-dimethyl-9-phenylpurin-6-amine, and 6-chloro-1-methyl-N-(4-nitrophenyl)pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4-amine all of which have the potential to significantly inhibit the biological activity of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. Besides, it should be noted that the tested compounds were representative of more than 140,000 compounds in the NCI Developmental Therapeutics Program (DTP) natural products repository. As a result, other natural products from the DTP database that are similar to the top-lead compounds can be further investigated for the ligand-binding affinity to SARS-CoV-2 Mpro and better potential candidates for preventing Mpro would, thus, be observed.

Toxicity of the top-lead compounds

PreADMET [68], an “absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion” (ADME) and toxicity descriptor evaluation tool, was applied for further analysis of promising compounds to estimate the mutagenicity and carcinogenicity by the Ames_test and hERG_inhibition values. All seven compounds were mutagenic but non-carcinogenic in mouse (except N-benzyl-1-methylpyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4-amine) and rat (except 3-[1-(4-methylphenyl)tetrazol-5-yl]pyridine) tests, thereby being at a medium risk level (Table 3). Hence, these compounds can be proposed as potential inhibitors targeting the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro protein.

Table 3.

Toxicity of promising inhibitors

| No | NSC ID | Ames_test | Carcino_mouse | Carcino_rat | hERG_inhibition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1451 | mutagen | positive | negative | medium_risk |

| 2 | 23,247 | mutagen | negative | positive | medium_risk |

| 3 | 7867 | mutagen | negative | negative | medium_risk |

| 4 | 166,596 | mutagen | negative | negative | medium_risk |

| 5 | 202,705 | mutagen | negative | negative | medium_risk |

| 6 | 34,488 | mutagen | negative | negative | medium_risk |

| 7 | 19,123 | mutagen | negative | negative | medium_risk |

Discussions

Numerous studies have documented the computational screening of compounds and their interactions with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro since the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro's first crystal structure in complex with a specially designed mechanistic inhibitor was determined [69]. Structural and biophysical approaches used in in silico virtual screening can aid in the design of specific SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors and significantly improve the quality of compounds chosen for in vitro and in vivo bioassays, increasing the success of drug discovery. Molecular docking, MD simulations, pharmacophore modeling, similarity analysis, and quantitative structure–activity relationship (QSAR) analysis are some typical CADD techniques. As expected, different works employing those techniques to screen for compounds having high binding affinity to SARS-CoV-2 Mpro from multiple database available [70–72]. The most frequently used strategy combines molecular docking and MD simulations [73–77]. However, analysis of docking-based virtual screening raised the concern that the correlation between the IC50 and docking scores was not good enough to completely endorse the use of a docking score as a threshold for choosing new potential Mpro inhibitors [78].

Regression or classification methods are frequently used in ML applications in drug design to evaluate a compound's activity against a target prior to clinical trials. Since ML techniques can be used to create predictive models based on past data, they are an important new tool for drug discovery and offer future perspectives against SARS-CoV-2. Several investigations involving an ML model to identify promising SARS-CoV-2 drugs were established [79–82]. Previously, analysis of four regression models, including linear regression (LR), random forest (RF), XGBoost, and convolutional networks on graphs (GraphConv), indicated that the XGBoost model performed the best in accurately predicting the binding free energies of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro ligands [17]. In this study, the strategy of combining the XGBoost model with molecular docking and MD simulations, therefore, effectively benefits from the advantages of both approaches. Also, the optimized LIE scheme further refined the MD outcome, efficiently nominating the compounds potentially possessing a high interacting affinity with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. This combined method is efficient, fast, requires minimal computing resources and, thus, is easy to adapt as a useful tool for virtual screening of promising inhibitors for Mpro of any future SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Conclusion

Using a combination of ML/Docking/MD calculations, seven representative compounds were identified as having the potential to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, namely N-benzyl-1-methylpyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4-amine, 3-[1-(4-methylphenyl)tetrazol-5-yl]pyridine, 6-chloro-N-(2-chlorophenyl)-1-methylpyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4-amine, 3-phenyl-6-thiophen-2-yl-[1,2,4]triazolo[3,4-b][1,3,4]oxadiazole, 1-(2,1,3-benzothiadiazol-4-yl)-3-(4-chlorophenyl)urea, N,N-dimethyl-9-phenylpurin-6-amine, and 6-chloro-1-methyl-N-(4-nitrophenyl)pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4-amine. Because these compounds are representative of natural compounds from the DTP repository, further analysis of similar compounds of seven ligands would also nominate the effective inhibitors for SARS-CoV-2 Mpro.

The values of binding affinity between SARS-CoV-2 Mpro and ligands predicted by ML calculations were underestimated in comparison to those obtained by molecular docking and LIE calculations, agreeing well with the previous work [17, 31]. The molecular docking and LIE calculations were in good agreement with each other with R of 0.65 and the RMSE of 0.79 kcal mol−1. Moreover, the suggested inhibitors form a large hydrophobic interaction with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Trung Hai Nguyen, Quynh Mai Thai, Minh Quan Pham, and Pham Thi Hong Minh. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Huong Thi Thu Phung and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology independent project under Grant number ĐL0000.07/22–23.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Code availability

The code generated during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest in this work.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Trung Hai Nguyen, Email: nguyentrunghai@tdtu.edu.vn.

Pham Thi Hong Minh, Email: minhhcsh@gmail.com.

Huong Thi Thu Phung, Email: ptthuong@ntt.edu.vn.

References

- 1.Cannalire R, Cerchia C, Beccari AR, Di Leva FS, Summa V. Targeting SARS-CoV-2 proteases and polymerase for COVID-19 treatment: state of the art and future opportunities. J Med Chem. 2022;65:2716–2746. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geng Q, Shi K, Ye G, Zhang W, Aihara H, et al. Structural basis for human receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant BA.1. J Vir. 2022;96:e00249–e1222. doi: 10.1128/jvi.00249-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Krüger N, Herrler T, et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO 2020 Coronavirus disease (2019) (COVID-19) Situation Report - 52

- 5.Huang CL, Wang YM, Li XW, Ren LL, Zhao JP, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG, Gao GF. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet. 2020;395:470–473. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu Wai C, Chin-Pang Y, Kwok-Yin W. Prediction of the SARS-CoV-2 (2019-nCoV) 3C-like protease (3CLpro) structure: virtual screening reveals velpatasvir, ledipasvir, and other drug repurposing candidates. F1000Res. 2020;9:129. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.22457.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jin Z, Du X, Xu Y, Deng Y, Liu M, et al. Structure of M pro from SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of its inhibitors. Nature. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2223-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olubiyi OO, Olagunju M, Keutmann M, Loschwitz J, Strodel B. High throughput virtual screening to discover inhibitors of the main protease of the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Molecules. 2020;25:3193. doi: 10.3390/molecules25143193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schoeman D, Fielding BC. Coronavirus envelope protein: current knowledge. Virology. 2019;16:69. doi: 10.1186/s12985-019-1182-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fauquet CM, Fargette D. International committee on taxonomy of viruses and the 3,142 unassigned species. Virology. 2005;2:64. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-2-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhavoronkov A, Aladinskiy V, Zhebrak A, Zagribelnyy B, Terentiev V, et al. Potential COVID-2019 3C-like protease inhibitors designed using generative deep learning approaches. ChemRxiv Camb: Cambr Open Engage. 2020 doi: 10.26434/chemrxiv.11829102.v2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pillaiyar T, Manickam M, Namasivayam V, Hayashi Y, Jung SH. An overview of severe acute respiratory syndrome–coronavirus (SARS-CoV) 3CL protease inhibitors: peptidomimetics and small molecule chemotherapy. J Med Chem. 2016;59:6595–6628. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freitas BT, Durie IA, Murray J, Longo JE, Miller HC, et al. Characterization and noncovalent inhibition of the Deubiquitinase and deISGylase activity of SARS-CoV-2 papain-like protease. ACS Infect Dis. 2020;6:2099–2109. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.0c00168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang L, Lin D, Sun X, Curth U, Drosten C, et al. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease provides a basis for design of improved α-ketoamide inhibitors. Science. 2020;368:409–412. doi: 10.1126/science.abb3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dai W, Zhang B, Jiang XM, Su H, Li J, et al. Structure-based design of antiviral drug candidates targeting the SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Science. 2020;368:1331–1335. doi: 10.1126/science.abb4489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nguyen TH, Tam NM, Tuan MV, Zhan P, Vu VV, et al. Searching for potential inhibitors of SARS-COV-2 main protease using supervised learning and perturbation calculations. Chem Phys. 2023;564:111709. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphys.2022.111709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ngo ST, Nguyen TH, Tung NT, Mai BK. Insights into the binding and covalent inhibition mechanism of PF-07321332 to SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. RSC Adv. 2022;12:3729–3737. doi: 10.1039/D1RA08752E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ngo ST, Hung Minh N, Le Thi TH, Pham Minh Q, Vi Khanh T, et al. Assessing potential inhibitors for SARS-CoV-2 main protease from available drugs using free energy perturbation simulations. RSC Adv. 2020;10:40284–40290. doi: 10.1039/D0RA07352K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Durdagi S, Dağ Ç, Dogan B, Yigin M, Avsar T, et al. Near-physiological-temperature serial crystallography reveals conformations of SARS-CoV-2 main protease active site for improved drug repurposing. Structure. 2021;29:1382–1396.e1386. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2021.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chauhan M, Bhardwaj VK, Kumar A, Kumar V, Kumar P, et al. Theaflavin 3-gallate inhibits the main protease (Mpro) of SARS-CoV-2 and reduces its count in vitro. Sci Rep. 2022;12:13146. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-17558-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Z, Li X, Huang YY, Wu Y, Liu R, et al. Identify potent SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors via accelerated free energy perturbation-based virtual screening of existing drugs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117:27381–27387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2010470117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vandyck K, Deval J. Considerations for the discovery and development of 3-Chymotrypsin-like cysteine protease inhibitors targeting SARS-CoV-2 infection. Curr Opin Virol. 2021;49:36–40. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2021.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao Y, Fang C, Zhang Q, Zhang R, Zhao X, et al. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease in complex with protease inhibitor PF-07321332. Protein Cell. 2021;13:689–693. doi: 10.1007/s13238-021-00883-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu W, MacKerell AD., Jr Computer-aided drug design methods. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1520:85–106. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6634-9_5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marshall GR. Computer-aided drug design. Annu Rev Pharmacol. 1987;27:193–213. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.27.040187.001205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ngo ST, Hong ND, Quynh Anh LH, Hiep DM, Tung NT. Effective estimation of the inhibitor affinity of HIV-1 protease via a modified LIE approach. RSC Adv. 2020;10:7732–7739. doi: 10.1039/C9RA09583G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nguyen TH, Tran PT, Pham NQA, Hoang VH, Hiep DM, Ngo ST. Identifying possible AChE inhibitors from drug-like molecules via machine learning and experimental studies. ACS Omega. 2022;7:20673–20682. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.2c00908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ngo ST. Estimating the ligand-binding affinity via λ-dependent umbrella sampling simulations. J Comput Chem. 2021;42:117–123. doi: 10.1002/jcc.26439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Homeyer N, Stoll F, Hillisch A, Gohlke H. Binding free energy calculations for lead optimization: assessment of their accuracy in an industrial drug design context. J Chem Theory Comput. 2014;10:3331–3344. doi: 10.1021/ct5000296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ngo ST, Tam NM, Pham MQ, Nguyen TH. Benchmark of popular free energy approaches revealing the inhibitors binding to SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. J Chem Inf Model. 2021;61:2302–2312. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.1c00159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zwanzig RW. High-temperature equation of state by a perturbation method I Nonpolar Gases. J Chem Phys. 1954;22:1420–1426. doi: 10.1063/1.1740409. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Democratizing Deep-Learning for Drug Discovery, Quantum Chemistry, Materials Science and Biology. GitHub Repository (2016) https://github.com/deepchem/deepchem

- 34.Subramanian G, Ramsundar B, Pande V, Denny RA. Computational modeling of β-secretase 1 (BACE-1) inhibitors using ligand based approaches. J Chem Inf Model. 2016;56:1936–1949. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.6b00290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim MO, Blachly PG, McCammon JA. Conformational dynamics and binding free energies of inhibitors of BACE-1: from the perspective of protonation equilibria. PLoS Comp Biol. 2015;11:e1004341. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thai QM, Pham TNH, Hiep DM, Pham MQ, Tran P-T, et al. Natural compounds inhibit AChE via machine learning and atomistic simulations. J Mol Graph Modell. 2022;115:108230. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2022.108230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Green H, Koes DR, Durrant JD. DeepFrag: a deep convolutional neural network for fragment-based lead optimization. Chem Sci. 2021;12:8036–8047. doi: 10.1039/D1SC00163A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klein JJ, Baker NC, Foil DH, Zorn KM, Urbina F, et al. Using bibliometric analysis and machine learning to identify compounds binding to sialidase-1. ACS Omega. 2021;6:3186–3193. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.0c05591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ngo ST, Nguyen TH, Tung NT, Vu VV, Pham MQ, Mai BK. Characterizing the ligand-binding affinity toward SARS-CoV-2 Mpro via physics-and knowledge-based approaches. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2022;24:29266–29278. doi: 10.1039/D2CP04476E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen JQ, Chen HY, Dai Wj, Lv QJ, Chen CYC. Artificial intelligence approach to find lead compounds for treating tumors. J Phys Chem Lett. 2019;10:4382–4400. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.9b01426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gao K, Nguyen DD, Chen J, Wang R, Wei G-W. Repositioning of 8565 existing drugs for COVID-19. J Phys Chem Lett. 2020;11:5373–5382. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.0c01579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gentile F, Fernandez M, Ban F, Ton A-T, Mslati H, et al. Automated discovery of noncovalent inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 main protease by consensus deep docking of 40 billion small molecules. Chem Sci. 2021;12:15960–15974. doi: 10.1039/D1SC05579H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Santana MVS, Silva-Jr FP. De novo design and bioactivity prediction of SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors using recurrent neural network-based transfer learning. BMC Chem. 2021;15:8. doi: 10.1186/s13065-021-00737-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ngo ST, Quynh Anh Pham N, Le Thi L, Pham DH, Vu VV. Computational determination of potential inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 main protease. J Chem Inf Model. 2020;60:5771–5780. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.0c00491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Milne GW, Miller J. The NCI drug information system. 1. System overview. J Chem Inf Comput Sci. 1986;26:154–159. doi: 10.1021/ci00052a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andi B, Kumaran D, Kreitler DF, Soares AS, Shi W, et al. Hepatitis C virus NSP3/NSP4A inhibitors as promising lead compounds for the design of new covalent inhibitors for SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro/Mpro protease. Sci Rep. 2022;12:12197. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-15930-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bergstra J, Yamins D, Cox D (2013) Making a science of model search: Hyperparameter optimization in hundreds of dimensions for vision architectures. Proc. International conference on machine learning, 2013:115–123: PMLR

- 48.Trott O, Olson AJ. Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem. 2010;31:455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pham TNH, Nguyen TH, Tam NM, Vu TY, Pham NT, et al. Improving ligand-ranking of autodock vina by changing the empirical parameters. J Comput Chem. 2021;43:160–169. doi: 10.1002/jcc.26779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morris GM, Huey R, Lindstrom W, Sanner MF, Belew RK, et al. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J Comput Chem. 2009;30:2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nguyen NT, Nguyen TH, Pham TNH, Huy NT, Bay MV, et al. Autodock vina adopts more accurate binding poses but autodock4 forms better binding affinity. J Chem Inf Model. 2020;60:204–211. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.9b00778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang CH, Stone EA, Deshmukh M, Ippolito JA, Ghahremanpour MM, et al. Potent noncovalent inhibitors of the main protease of SARS-CoV-2 from molecular sculpting of the drug perampanel guided by free energy perturbation calculations. ACS Cent Sci. 2021;7:467–475. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.1c00039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cao DT, Huong Doan TM, Pham VC, Le Minh TH, Chae JW, et al. Molecular design of anticancer drugs from marine fungi derivatives. RSC Adv. 2021;11:20173–20179. doi: 10.1039/D1RA01855H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lan NT, Vu KB, Dao Ngoc MK, Tran P-T, Hiep DM, et al. Prediction of AChE-ligand affinity using the umbrella sampling simulation. J Mol Graph Model. 2019;93:107441. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2019.107441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Abraham MJ, Murtola T, Schulz R, Páll S, Smith JC, et al. GROMACS: high performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX. 2015;1–2:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.softx.2015.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang J, Wolf RM, Caldwell JW, Kollman PA, Case DA. Development and testing of a general amber force field. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1157–1174. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura JD, Impey RW, Klein ML. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J Chem Phys. 1983;79:926–935. doi: 10.1063/1.445869. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aliev AE, Kulke M, Khaneja HS, Chudasama V, Sheppard TD, Lanigan RM. Motional timescale predictions by molecular dynamics simulations: case study using proline and hydroxyproline sidechain dynamics. Proteins: Struct Funct Bioinf. 2014;82:195–215. doi: 10.1002/prot.24350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Case DA, Ben-Shalom IY, Brozell SR, Cerutti DS, Cheatham TE, et al. AMBER 18. San Francisco: University of California; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hess B, Bekker H, Berendsen HJC, Fraaije JGEM. LINCS: a linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J Comp Chem. 1997;18:1463–1472. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(199709)18:12<1463::AID-JCC4>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Almlöf M, Brandsdal BO, Åqvist J. Binding affinity prediction with different force fields: Examination of the linear interaction energy method. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1242–1254. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schrödinger LLC P (2020) Schrödinger Release 2020–4: Maestro

- 63.Chen T, Guestrin C (2016) XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. KDD '16: Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining:785–794

- 64.Ngo ST, Vu KB, Pham MQ, Tam NM, Tran PT. Marine derivatives prevent wMUS81 in silico studies. Royal Soc Open Sci. 2021;8:210974. doi: 10.1098/rsos.210974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Quan PM, Anh HBQ, Hang NTN, Toan DH, Ha DV, Long PQ. Marine derivatives prevent E6 protein of HPV: an in silico study for drug development. Reg Stud Mar Sci. 2022;56:102619. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ngo ST, Vu VV, Thu Phung HT. Computational investigation of possible inhibitors of the winged-helix domain of MUS81. J Mol Graph Modell. 2021;103:107771. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2020.107771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ngo ST, Mai BK, Derreumaux P, Vu VV. Adequate prediction for inhibitor affinity of Aβ40 protofibril using the linear interaction energy method. RSC Adv. 2019;9:12455–12461. doi: 10.1039/C9RA01177C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lee SK, Lee IH, Kim HJ, Chang GS, Chung JE, No KT. The PreADME approach: Web-based program for rapid prediction of physico-chemical, drug absorption and drug-like properties, EuroQSAR 2002 designing drugs and crop protectants: processes, problems and solutions. Maldenh, MA: Blackwell Publishing; 2003. pp. 418–420. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jin Z, Du X, Xu Y, Deng Y, Liu M, et al. Structure of Mpro from SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of its inhibitors. Nature. 2020;582:289–293. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2223-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Banerjee R, Perera L, Tillekeratne LV. Potential SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors. Drug Discov Today. 2021;26:804–816. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2020.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Serafim MS, Gertrudes JC, Costa D, Oliveira PR, Maltarollo VG, Honorio KM. 2021. Knowing and combating the enemy: a brief review on SARS-CoV-2 and computational approaches applied to the discovery of drug candidates. Biosci Rep. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 72.Porto VA, Porto RS. In silico studies of novel synthetic compounds as potential drugs to inhibit coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2): a systematic review. Biointerface Res Appl Chem. 2022;12:4293–4306. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liang J, Pitsillou E, Karagiannis C, Darmawan KK, Ng K, et al. Interaction of the prototypical α-ketoamide inhibitor with the SARS-CoV-2 main protease active site in silico: molecular dynamic simulations highlight the stability of the ligand-protein complex. Comput Biol Chem. 2020;87:107292. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2020.107292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pant S, Singh M, Ravichandiran V, Murty U, Srivastava HK. Peptide-like and small-molecule inhibitors against Covid-19. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2021;39:2904–2913. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1757510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sasidharan S, Selvaraj C, Singh SK, Dubey VK, Kumar S, et al. Bacterial protein azurin and derived peptides as potential anti-SARS-CoV-2 agents: insights from molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2021;39:5706–5721. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1787864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kumar Y, Singh H, Patel CN. In silico prediction of potential inhibitors for the main protease of SARS-CoV-2 using molecular docking and dynamics simulation based drug-repurposing. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13:1210–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jiménez-Alberto A, Ribas-Aparicio RM, Aparicio-Ozores G, Castelán-Vega JA. Virtual screening of approved drugs as potential SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors. Comput Biol Chem. 2020;88:107325. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2020.107325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Macip G, Garcia-Segura P, Mestres-Truyol J, Saldivar-Espinoza B, Ojeda-Montes MJ, et al. Haste makes waste: a critical review of docking-based virtual screening in drug repurposing for SARS-CoV-2 main protease (M-pro) inhibition. Med Res Rev. 2022;42:744–769. doi: 10.1002/med.21862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gawriljuk VO, Zin PPK, Puhl AC, Zorn KM, Foil DH, et al. Machine learning models identify inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2. J Chem Inf Model. 2021;61:4224–4235. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.1c00683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rodrigues G, dos Santos MM, de Menezes RPB, Cavalcanti ABS, de Sousa NF, et al. Ligand and structure-based virtual screening of lamiaceae diterpenes with potential activity against a novel coronavirus (2019-NCOV) Curr Top Med Chem. 2020;20:2126–2145. doi: 10.2174/1568026620666200716114546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Alves VM, Bobrowski T, Melo-Filho CC, Korn D, Auerbach S, et al. QSAR Modeling of SARS-CoV Mpro inhibitors identifies sufugolix, cenicriviroc, proglumetacin, and other drugs as candidates for repurposing against SARS-CoV-2. Mol Inform. 2021;40:2000113. doi: 10.1002/minf.202000113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kowalewski J, Ray A. Predicting novel drugs for SARS-CoV-2 using machine learning from a> 10 million chemical space. Heliyon. 2020;6:e04639. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Serafim MS, Gertrudes JC, Costa D, Oliveira PR, Maltarollo VG, Honorio KM. 2021. Knowing and combating the enemy: a brief review on SARS-CoV-2 and computational approaches applied to the discovery of drug candidates. Biosci Rep. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

The code generated during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.