Abstract

α-Agglutinin and a-agglutinin are complementary cell adhesion glycoproteins active during mating in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. They bind with high affinity and high specificity: cells of opposite mating types are irreversibly bound by a few pairs of agglutinins. Equilibrium and surface plasmon resonance kinetic analyses showed that the purified binding region of α-agglutinin interacted similarly with purified a-agglutinin and with a-agglutinin expressed on cell surfaces. At 20°C, the KD for the interaction was 2 × 10−9 to 5 × 10−9 M. This high affinity was a result of a very low dissociation rate (≈ 2.6 × 10−4 s−1) coupled with a low association rate (= 5 × 104 M−1 s−1). Circular-dichroism spectroscopy showed that binding of the proteins was accompanied by measurable changes in secondary structure. Furthermore, when binding was assessed at 10°C, the association kinetics were sigmoidal, with a very low initial rate. An induced-fit model of binding with substantial apposition of hydrophobic surfaces on the two ligands can explain the observed affinity, kinetics, and specificity and the conformational effects of the binding reaction.

There has been little work on the binding characteristics of microbial cell adhesion proteins, which can function under a variety of conditions not encountered in cell adhesion systems of multicellular organisms (28). Sexual cell adhesion in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is mediated through two interacting cell wall glycoproteins, a-agglutinin and α-agglutinin, which are expressed on haploid a and α cells, respectively (29, 41). These proteins are expressed at low levels constitutively, and gene expression and cell surface concentration are upregulated in response to a sex pheromone produced by the opposite mating type. The pheromones do not change the binding affinity (40).

a-Agglutinin consists of two subunits. The binding subunit Aga2p is a glycopeptide containing 69 amino acid residues and about 20 O-linked oligomannosyl chains (3). Aga2p carries the adhesive domain, and its C-terminal 10 amino acids (sequence GSPINTQYVF ) can act as a ligand for α-agglutinin (2). A pair of disulfide bonds links Aga2p to the anchorage subunit of a-agglutinin Aga1p (2, 35). Aga1p itself is a highly O-glycosylated protein of 725 amino acid residues including an N-terminal secretion signal and a C-terminal signal for addition of a glycosyl phosphatidylinositol anchor (GPI). Aga1p anchors Aga2p onto the cell surface but has no direct role in binding (35, 35a).

α-Agglutinin, the other cell adhesion molecule responsible for agglutination, is the product of the AGα1 (SAG1) gene. The N-terminal half of α-agglutinin is homologous to the immunoglobulin superfamily and contains the binding site for a-agglutinin (4, 16, 42). This region is β-sheet rich and shows a high degree of conformational flexibility (45, 46). Residues near His292 and Lys154 have been implicated in binding (2, 4, 6, 45). The C-terminal half of α-agglutinin anchors the protein and consists of a highly glycosylated “stalk” of about 300 amino acids. This is followed by a modified GPI anchor that covalently attaches the molecule to β1,6-glucan, a cell wall polysaccharide (31, 32, 42). These features of the α-agglutinin sequence are similar to those of several Candida albicans cell adhesion proteins that mediate host-pathogen interactions (11–13, 17, 18).

The agglutinins bind tightly to each other at low to moderate ionic strengths and with a pH optimum of 5.5. Binding of 125I-α-agglutinin fragments to cell-bound a-agglutinin showed a specific and complex interaction consistent with at least two states, weak and tight. Weakly bound 125I-α-agglutinin was removed from the a cells by washing. The tight state had a KD of about 10−9 M and was essentially irreversible, implying a low rate of dissociation (30). Formation of this state was cold sensitive.

We now describe a study of the binding interaction based on highly purified recombinant agglutinins. A surface plasmon resonance (SPR) analysis confirmed the original estimates of KD and together with circular dichroism (CD) showed a conformational basis for complex binding kinetics. The binding kinetics demonstrated a basis for the cold sensitivity of sexual agglutination.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

The following reagents were obtained from Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, Mo: cycloheximide, p-chloromercuribenzoic acid (PCMB), α-methylmannoside, and bovine serum albumin (BSA). Protein standards, Bio-Gel P-60, and Bio-Gel P-100 were purchased from Bio-Rad (Richmond, Calif.). Restriction enzymes were from New England Biolabs. Endoglycosidase H was from Boehringer Mannheim. Plasmon resonance experiments were performed on BIACORE X, which together with C1 sensor chips, N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS), N-ethyl-N′-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide hydrochloride, and 1 M ethanolamine (pH 8.5) were obtained from Pharmacia Biosensor AB (Uppsala, Sweden). Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) reagents and standards were from Bio-Rad.

Purification of Aga2p.

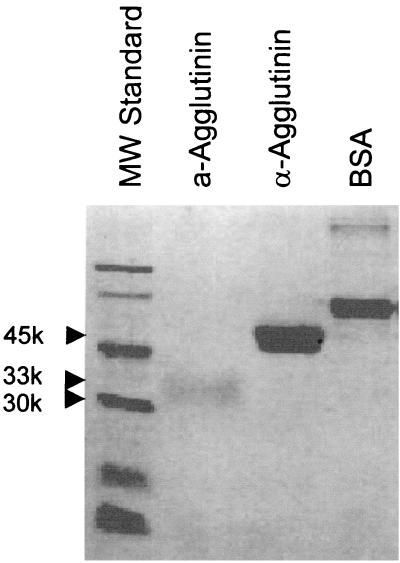

W303 diploid cells containing plasmid YEpPGK-AGA2 constitutively expresses Aga2p under the control of the PGK promoter. Cells were grown in synthetic medium without uracil to 4 × 107/ml and harvested. Cell culture supernatants were then collected and concentrated 10-fold through a Millipore filter with a 10-kDa molecular-mass cutoff. Concentrated supernatant was further dialyzed against 20 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.5)–1 mM EDTA, lyophilized, and resuspended in the same buffer with 10% (vol/vol) glycerol. Aga2p was purified using a Bio-Gel P-60 size exclusion column equilibrated in 20 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.5. Because of its extensive glycosylation, Aga2p has an apparent molecular mass of 33 kDa on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gels stained with Coomassie blue (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

SDS-PAGE analysis of α-agglutinin and Aga2p. Protein samples were electrophoresed in SDS on a 10% polyacrylamide minigel and stained with Coomassie blue. First lane, molecular weight (MW) standards (phosphorylase b, 97,400; BSA, 66,200; ovalbumin, 45,000; carbonic anhydrase, 31,000; soybean trypsin inhibitor, 21,500; lysozyme 14,400); second lane, Aga2p, glycosylated protein with apparent molecular mass of 33 kDa; third lane, α-agglutinin, glycosylated protein with an apparent molecular mass of 45 kDa; fourth lane, BSA, 1 μg.

Purification of α-agglutinin.

α-Agglutinin containing residues 20 to 351 (α-agglutinin20–351) was purified from the cell culture supernatant (4 liters) of yeast strain Lα21 (MAT α ade2-1 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trpl-1 ura3-1 can1-100 agα1-3) containing pPGK-AGαl351. A DEAE-Sephadex A-25 column and a Bio-Gel P-60 size exclusion column were used for the purification (4). Partially deglycosylated α-agglutinin20–351 had an apparent molecular mass of 45 kDa on Coomassie blue-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel and was of 99% purity by scanning densitometry (Molecular Dynamics) (Fig. 1).

PAGE.

The protein samples were electrophoresed in SDS- or non-SDS-polyacrylamide gels with 10% running gels and 4% stacking gels (26).

Anti-α-agglutinin antibody preparation.

Anti-α-agglutinin antibody was produced by injecting purified protein (100 μg, twice) in Hunter's Titermax into rabbits. The sera were then collected 10 to 25 weeks after the initial injection and were absorbed twice against washed, heat-killed a cells.

Separation of α-agglutinin aggregates and immunodetection.

A sample of purified α-agglutinin was thawed and filtered through a Bio-Gel P-100 column in 100 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.5. The samples collected from the column were electrophoresed in non-SDS– and SDS–10% polyacrylamide gels and then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane by electrophoresis. The blot was first incubated in 10 mM Tris–140 mM NaCl (pH 7.4; buffer B), with 3% gelatin for 30 min and then in anti-α-agglutinin antibody (diluted 1:500) for 1 h. Afterwards, the blot was washed and incubated in anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G peroxidase conjugate (diluted 1:1,000) in buffer B with 1% gelatin for 1 h. The blot was then washed and visualized with 4-chloro-1-naphthol in 10 ml of cold methanol and 3% hydrogen peroxide in 50 ml of buffer B. The fractions containing no aggregates were used for BIACORE experiments.

SPR.

The detection of binding or dissociation in SPR is based on the change in the refractive index due to association of a soluble analyte to an immobilized ligand. The resulting signal is proportional to the amount of protein bound, and 1,000 resonance units correspond to 1 ng/mm2 (20). The flat carboxymethylated surface of a C1 sensor chip was first cleaned with 10 μl of 0.1 M glycine-NaOH and then activated by 35 μl of a solution containing 0.2 M N-ethyl-N′-3-aminopropyl carbodiimide and 0.05 M NHS at a flow rate of 5 μl/min. Then, two 25-μl aliquots of purified Aga2p (5 μg/ml) in 100 mM phosphate buffer were injected over the surface at a flow rate of 5 μl/min. The remaining unreacted NHS-ester groups were deactivated by injection of 25 μl of 1 M ethanolamine-HCl, pH 8.5, and the surface was further blocked by injecting if twice with 25 μl of 100-μg/ml BSA in HBS buffer (10 mM HEPES and 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4). The flow rate was 5 μl/min.

The buffer was then switched to MES buffer (10 mM MES [morpholineethanesulfonic acid] and 150 mM NaCl, pH 5.9), and the chip was blocked twice more by injection of BSA. MES buffer was used as the association and dissociation buffer for the interaction of a-agglutinin and α-agglutinin. Association and subsequent dissociation were measured by the injection of 100 μl of an α-agglutinin solution at a flow rate of 20 μl/min, using several concentrations of α-agglutinin The sensor surface was regenerated by injection of 100 μl of 4 M MgCl2.

The association rate constant (Kon) and the dissociation rate constant (koff) were obtained from curve fitting by nonlinear least-squares regression. The equilibrium dissociation constant was calculated from the following equation: KD = koff/kon. Data analysis was performed using the BIA Evaluation 3.0 software package (Pharmacia Biosensor AB) (21), which calculates nonlinear regressions according to the Langmuir isotherm theory. Curves from 20°C isotherms were fitted over 200-s intervals, with mean residuals of 2%. The sigmoidal associations at 10°C were fitted in two independent regions of the binding curve, an early region (110 to 180 s) and a later one (200 to 330s). For the early regions, the mean residual was <3%, and for the late regions, it was <2%. Estimates of koff were obtained from 30-min dissociation curves to compensate for the low rate and the apparent linearity at shorter times. The values were also checked by hand on semilogarithmic plots.

Isotopic labeling of α-agglutinin with 125I-Bolton Hunter reagent.

Purified α-agglutinin (0.1 mg/ml) was dialyzed against 200 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 8.5, overmight. The protein (20 μg) was reacted with 250 μCi of 125I-Bolton Hunter reagent (New England Nuclear Corp.) for 3 h at 0°C. The reaction mixture was diluted 20-fold in the reaction buffer (100 mM sodium acetate [pH 5.5], 1 μM CaCl2, and 1 μM MnSO4). The diluted sample was applied to a 1-ml prepacked lentil lectin-agarose column, which was preequilibrated with reaction buffer. The protein was eluted with 1 M α-methylmannoside and 500 mM sodium chloride in 100 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.5. The labeled α-agglutinin was stored at 4°C in the eluting buffer supplemented with 10% glycerol and 1 mg of BSA per ml.

Binding of 125I-α-agglutinin to yeast cells.

Various concentrations of 125I-α-agglutinin were incubated with 2 × 106 X2180-1A (MATaSUC2 mal mel gal2 CUP1) or X2180-1B (MATα SUC2 mal mel gal2 CUP1) cells in a total volume of 250 μl on a rotary shaker at 200 rpm at 25 or 0°C for 90 min, the time required to reach equilibrium. The buffer used for this study was 100 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.5, supplemented with 1 mg of BSA per ml, 1μg of cycloheximide per ml, 1 μM p-chloromercuribenzoic acid (39). After the incubation, cells with bound α-agglutinin were centrifuged, the supernatants were aspirated, and the cells were then washed three times. The bound 125I-α-agglutinin was counted in a Compugamma 1282 (LKB Wallac Inc.), and specific binding was determined as the difference in the levels of binding between MATa and MATα cells under identical conditions. The nonspecific binding to MATα cells was not saturable and was similar to noncompetable binding to MATa cells, as previously reported. (39). Equilibrium constants were determined from Scatchard analysis of the binding.

Concentration determination of 125I-α-agglutinin.

Samples of 125I-α-agglutinin (10 μl) were incubated with 2 × 106 a or α cells in a 200-μl total volume to obtain the maximum specific binding capacity of a cells. Specific binding was then determined in a competition assay between 125I-α-agglutinin (5 μl) and different concentrations of unlabeled α-agglutinin of known concentration. After incubation, the cells with bound 125I-α-agglutinin were washed and counted. The concentration of 125I-α-agglutinin was calculated to be 0.105 μM in the stock solution, based on the concentration of unlabeled α-agglutinin giving 50% inhibition of binding (1).

Peptide synthesis.

A peptide containing the C-terminal 10 residues of Aga2p was synthesized by the solid-phase method using fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl chemistry on an Applied Biosystems automated model 432A peptide. The peptide resins were treated with 80% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)–5% water–5% ethanedithiol–10% thioanisole at room temperature for 2 h to cleave and deprotect the peptides, which were then precipitated and washed in cold methyl t-butyl ether and collected by centrifugation at 25°C.

Purification of the peptides was achieved by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography on a C18 column (21.4 by 250 mm) using 0.1% TFA as buffer A and 70% acetonitrile in 0.1% TFA as buffer B. A linear gradient between 0 and 100% buffer B in buffer A was used at a flow rate of 5 ml/min over a period of 60 min. The elution profile was monitored at 215 nm. The purified peptides were lyophilized and redissolved in deionized water at 25°C and stored at 4°C.

Agglutination assay.

S. cerevisiae wild-type haploid strains X2180-1A (MATa SUC2 mal mel gal2 CUP1) and X2180-1B (MAT α SUC2 mal mel gal2 CUP1) were used for bioassays. a cells and α cells were grown separately in minimal medium to 2 × 107 cells per ml, and a cells were treated with the sex pheromone α-factor as described previously (41). These cells were harvested and washed in 100 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.5, at 25°C. α-Agglutinin was incubated with a cells on a rotary shaker at 25°C for 90 min, and α cells were then added. The activity of α-agglutinin was determined by its ability to inhibit the agglutination of a cells (41), with 1 U being the amount of protein needed to inhibit agglutination by 10%.

CD spectroscopy.

Far-UV CD spectra were recorded on a Jasco J-710 spectropolarimeter equipped with a thermo-regulated cell holder with a 0.05-cm path length (HELLMA). Each spectrum represents the average of 10 spectra taken at 0.5-nm intervals from 250 to 200 nm. The spectra were corrected by subtraction of the appropriate buffer baseline spectra and smoothed by Jasco Series 700 software. Each experiment was repeated three times. CD data presented here were analyzed by the self-consistent method (SELCON) (36, 37).

RESULTS

Binding of 125I-α-agglutinin to intact cells.

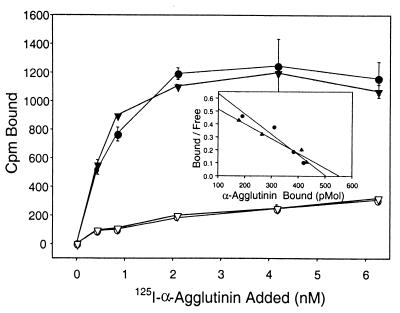

As indicated in Fig. 2, the binding of 125I-α-agglutinin to a cells at 25 and 0°C showed only slight differences in affinity or site numbers. There was little nonspecific binding to cells of mating type α. When the protein concentration was 5 nM or higher, the binding approached saturation. The inset of Fig. 2 shows Scatchard plots of the binding, with cells displaying a KD of 6.34 × 10−10 M at 0°C and 8.6 × 10−10 M at 25°C, values similar to that previously reported (30). There were about 7.5 × 104 α-agglutinin molecules bound per a cell at saturation. For samples incubated at either temperature, washing the cells before counting did not reduce the specific binding significantly. Therefore, no weak interactions were observed at either temperature. We speculate that the weak and cold-sensitive binding seen in a previous study might have been due to low-affinity binding of partially active fragments of α-agglutinin (30).

FIG. 2.

Binding of purified 125I-α-agglutinin to a cells. Increasing concentrations of 125I-α-agglutinin were incubated with 2 × 106 MATa cells or MATα cells for 90 min. After a thorough washing, levels of bound 125I-α-agglutinin were determined. Binding isotherms are shown for 25°C (circles) and 0°C (triangles). Binding to MATa cells is shown with filled symbols; binding to MATα cells is shown with open symbols. Error bars represent the ranges for results of triplicate samples. (Inset) Scatchard plots for specific binding at each temperature.

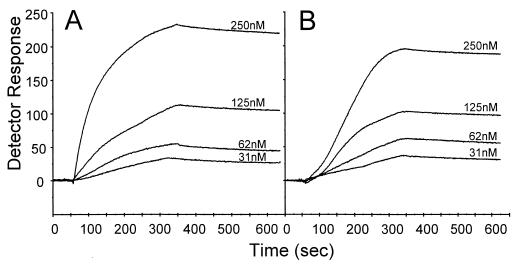

SPR analysis of binding kinetics.

In equilibrium binding experiments with radioactively labeled α-agglutinin, low temperature had little effect on the binding isotherm. However, previous studies showed that low temperature does reduce cellular agglutinability both in vivo and in vitro (41, 43). SPR was used to obtain the koff and the kon and to detect the effect of low temperature on the interaction of the agglutinins in real time.

SPR detects changes in the refractive index in proportion to the mass of the surface-bound analyte (23). Therefore, to increase the sensitivity of the system, it is advantageous to immobilize the lower-molecular-weight reactant as the ligand and to use the higher-molecular-weight reactant as the analyte in the solution phase. Also, in order to limit mass transportation and to make sure that the reaction reaches equilibrium within reasonable time limits, optimal conditions for kinetic experiments require a relatively low concentration of the protein covalently bound on the surface of the detector chip. Therefore, purified Aga2p was immobilized on the sensor surface and the amount of α-agglutinin was adjusted so that the response amplitude of the binding would be in the desired range (22, 33). “Sensorgrams” for the interaction of various concentrations of α-agglutinin with the immobilized a-agglutinin at 20 and 10°C are shown in Fig. 3. At 20°C there was a very low koff of (7.0 ± 1.4) × 10−5 s−1 and a single kon of (4.61 ± 0.03) × 104 M−1 s−1. These values give a KD of (1.55 ± 0.31) × 10−9. At 10°C, the koff was (5.4 ± 0.5) × 10−5 s−1 (Fig. 3), slightly lower than that at 20°C. A sigmoid association curve was observed with an initial very low kon of (0.13 ± 0.07) M−1 s−1 and a later higher kon of (5.59 ± 0.4) × 104 M−1 s−1, similar to the single kon at 20°C. Therefore, at 10°C there were two apparent dissociation constants, (6.18 ± 3.49) × 10−4 M and (9.8 ± 1.0) × 10−10 M.

FIG. 3.

SPR analysis of binding of α-agglutinin to Aga2p. Aga2p was coupled to a C1 pioneer chip through amine chemistry. Aliquots (100 μl) at various concentrations of α-agglutinin were then injected over the sensor chip at 20 μl/min in 10 mM MES buffer plus 150 mM NaCl, pH 5.9. (A) Binding at 20°C; (B) binding at 10°C.

Effects of protein aggregates.

Protein aggregates may sometimes bind with high affinity, and dissociation rates decrease in geometric proportion to the number of the binding sites in the aggregates (24, 44). To correct the estimate of koff for the presence of aggregates, gel-filtered α-agglutinin was prepared and injected into the BIACORE instrument. This material had a kon of (5.6 ± 2.2) × 104 M−1, similar to that of the experiment shown in Fig. 3, and a higher koff of (2.6 ± 0.6) × 10−4 s−1, corresponding to a KD of (5.5 ± 2.6) × 10−9 M.

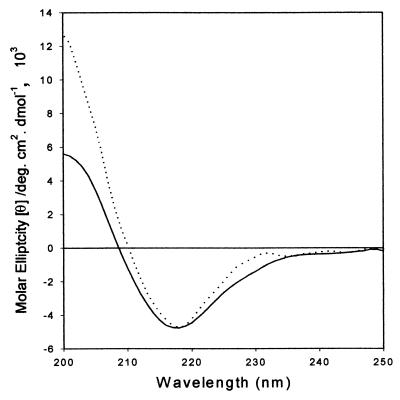

Conformational changes of the agglutinins induced by a-agglutinin peptide binding.

Sigmoidal association kinetics and low kon and koff are characteristics of binding dependent on conformational change in the ligands (induced-fit models [25]). A CD analysis of binding of α-agglutinin binding to an a-agglutinin peptide tested for conformational changes on binding.

A peptide containing the C-terminal 10 residues (GSPINTQYVF) of Aga2p binds to α-agglutinin and competes with Aga2p (2). We synthesized this peptide and found its specific activity to be 2.6 × 1010 U/mol, similar to that previously determined (3) and corresponding to an affinity 250-fold less than that of native of a-agglutinin). We have also found that site-specific mutations in the C-terminal residues of Aga2p inactivate it. No other region of the protein was required for activity (35a).

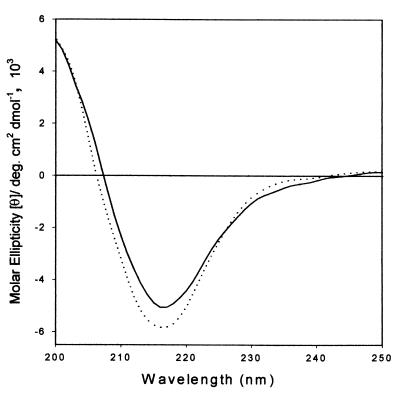

We then determined far-UV CD spectra of 5 × 10−6 M α-agglutinin and the 1 × 10−5 M Aga2p C-terminal decapeptide. A spectrum of a complex of these components was acquired after coincubation in 10 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.5, at 25°C for 30 min. Under these conditions, at least 96% of the α-agglutinin would have ligand bound. The CD spectrum of the a-agglutinin peptide in the same buffer was then subtracted from that of the complex. The difference spectrum (Fig. 4) showed that the complex still contained a principal negative magnitude band at 217 nm, which was narrower than that of α-agglutinin alone. The positive peak below 207 nm was strongly intensified, and there was an extra positive shoulder at 225 to 234 nm. All these changes came either from conformational changes of α-agglutinin upon binding or a combination of secondary-structure changes of both α-agglutinin and the a-agglutinin peptide. Secondary-structure analysis was consistent with a slight increase in each of the periodic structural components and a decrease in aperiodic structure from 38.6 to 31.6% (36). These changes are greater than the measured experimental errors, so some unstructured regions of a- and α-agglutinin became more structured upon ligand binding (15). An increase in structure for 7% of the residues would correspond to about 24 amino acid residues.

FIG. 4.

Far-UV CD of α-agglutinin induced by binding of the a-agglutinin peptide. Far-UV CD spectra of α-agglutinin were measured at 25°C in 10 mM sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.5 (—). Also shown is a difference spectrum of α-agglutinin incubated with the Aga2p C-terminal peptide, with the CD contribution of the peptide subtracted (····). deg., degrees.

Effect of reduced temperature on the conformation of α-agglutinin.

To determine if cold temperature affected the secondary structure of α-agglutinin, far-UV CD spectra of α-agglutinin were measured and compared at 25 and 0°C. As shown in Fig. 5, CD spectra at both temperatures showed a major band at 217 nm, a contribution of peptide chromophores in β-conformation. However, at 0°C, the magnitude of the negative band at 217 nm was intensified and broadened at lower wavelengths, indicating a possible increase of β-sheet structure. In addition, at 0°C, the spectrum was less negative between 227 and 237 nm. The protein appeared to be more structured at low temperature than at room temperature: the total β-sheet content increased from 47.8 to 54.4%, and the random structure dropped from 36.5 to 26.1%. Such a change corresponds to an addition of about 24 to 34 residues to regions with periodic secondary structures (α-helix or β-sheet).

FIG. 5.

Effect of cold temperature on far-UV CD of α-agglutinin. Far-UV CD spectra of α-agglutinin were measured in 10 mM sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.5, at 25°C (—) and after incubation at 0°C for 20 min (····). deg., degrees.

DISCUSSION

Complexity of binding.

Kinetics and secondary-structure analysis of interacting yeast sexual agglutinins showed complexity and the characteristics of an induced-fit interaction (25). The binding parameters obtained in various experiments yield KDs of 1 × 10−9 to 5 × 10−9 M, corresponding to a binding energy of −11 to −12 kcal/mol. The uncertainty in KD results from the uncertainty in the koff, which is close to the limit of reliability of SPR, and indeed equilibrium binding gives a KD corresponding to the tighter binding value.

The initial binding was slow and temperature dependent. Formation of tight bonds was accompanied by a change in the secondary structure of the receptor α-agglutinin and also the ligand a-agglutinin. All of these observations are compatible with a model in which initial interaction of the agglutinins triggers a conformational shift that greatly increases the contact area between the glycoproteins, resulting in tight binding and a very low dissociation rate, as observed.

Effect of low temperature on protein flexibility.

Incubation at 0 to 10°C results in poor agglutination of intact cells (41, 43). In SPR experiments (Fig. 3), there was also a marked decrease in the initial association rate of the agglutinins at low temperatures. This result can be interpreted as reduced flexibility in one or both of the components. There is direct evidence for such reduced flexibility in α-agglutinin at reduced temperatures. This protein showed a 7 to 10% increase in the fraction of the periodic secondary structure (α-helix and β-sheet) and a concomitant decrease in the fraction of the aperiodic secondary structure. The increase in the fraction of the periodic secondary structure encompasses 24 to 34 residues, far greater than the standard deviation for secondary-structure assignments (about 1.3% or 4 residues). This change represents a decrease in the inherent flexibility of α-agglutinin (45, 46), because the conformations of residues in sheets and helices are stabilized by backbone hydrogen bonding, as well as by side chain interactions. However, the binding characteristics implied that, at low temperatures, the rate-limiting step was a conformational change in the ligand a-agglutinin.

Conformational changes on binding.

The conformational change observed on binding includes removal of about 24 amino acids from less structured aperiodic conformations to helix or sheet. There are 10 residues in the a-agglutinin peptide used as the ligand, so there is an approximate minimum of 14 residues of α-agglutinin whose secondary-structural state is altered by binding. There is a precedent for this type of interaction: PDZ domains bind the C-terminal regions of their ligands, with the ligand forming an extra β-strand in a sheet. Like the agglutinin system, the ligand-receptor complex is more structured than the sum of the individual components. Also, like in the agglutinin system, binding is tight and dissociation is extremely slow (5, 7).

A model of the interaction of the agglutinins at different temperatures.

A model of the interaction between the agglutinins based on binding data and secondary-structure analysis is shown below: inhibited at low temperature +[α] [a'] →←⊥[a] →← [a·α]

In this model, unliganded a-agglutinin can exist in either of two conformations: open [a] or closed [a′]. The conformational change between the states is reversible, but [a′] is favored at low temperature and conversion from [a′] to [a] is inhibited at low temperature. α-Agglutinin binds to state [a] with high affinity in a multistep reaction at room temperature. α-Agglutinin binds to state [a′] poorly, if it binds at all. The result is a sigmoidal kinetic association curve at low temperature. As the α-agglutinin binds to the small amount of agglutinin available in the [a] state, the resulting depletion of agglutinin in the [a] state promotes the slow formation of more agglutinin in the [a] state from that in the [a′] inactive state. At low temperatures the apparent initial kon is 5 × 105-fold lower than at 25°C; this difference is enough to delay bond formation measurably in agglutination assays (41) as well as in the SPR association experiment (Fig. 3B). There is no significant effect on binding in extended incubations with 125I-α-agglutinin (Fig. 2), because the a-agglutinin is present in great excess in those experiments, and there is sufficient material in the [a] state to bind the available α-agglutinin.

Similar binding systems.

The above model of binding-induced conformational changes of the agglutinins is similar to the induced-fit model of interaction of substrate and enzyme, where the active site of the enzyme assumes a shape complementary to that of the substrate after it is bound (25). Well-characterized examples include interactions of antigens with antibodies. For example, a structural rearrangement next to the helical binding site of a tobacco mosaic virus protein occurs during the high-affinity interaction between the protein and its antibody (9, 34). Slow conformational changes of human immunodeficiency virus core protein p24 are involved in the high-affinity interaction of the protein to its own monoclonal antibody (14). Conformational changes of the integrin αIIbβ3 (platelet GPIIb-IIIa) triggered by binding of Arg-Gly-Asp sequences in fibrinogen generate a high-affinity binding state of integrin (8). Using SPR, Huber also studied the interaction of αIIbβ3 with fibrinogen and found an initial low-affinity interaction leading to a higher-affinity state (19). Conformational changes of the cell adhesion protein thrombrospondin are induced by binding to the receptor CD36 (GPIIIb or GPIV) (27).

A sigmoidal kinetic association curve has also been observed by Friguet et al. in an antigen-antibody interaction (10). They described such interaction to be a multistep association interaction, and conformational rearrangement occurs upon binding. An initial encounter of the complex is believed to be responsible for inducing and stabilizing the second-step interaction, a change due to conformational rearrangement. A similar conformationally driven two-phase association was also reported in the interaction of antigen HIVp24 with an antibody using SPR technology (14).

Biological consequences of binding.

In the yeast sexual agglutination system, the situation in vivo is that cellular aggregation is irreversible. Cell surface concentrations of the agglutinins are about 10−3 M after their expression has been upregulated by sex pheromones (35a). At this concentration, strong adhesive bonds between agglutinating cells would form within a few seconds, as has been observed previously (38). A dissociation rate of 10−4 s−1 would mean that two singly tethered cells likely dissociate in several hours, about the time two cells take to fuse. The koff values for bivalent systems are the products of the univalent rates. So, if two cells were attached through two adhesive bonds, the dissociation of most pairs would take 108 s (more than a year). Thus, in contrast to the transient interactions that characterize cell interactions in the immune system, yeast sexual agglutination makes adhesive bonds that are irreversible within biologically relevant times.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dixie Goss, in the Department of Chemistry at Hunter College, for use of the CD spectrophotometer.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of General Medical Science (1R01-GM47176) to Janet Kurjan, University of Vermont; the Research Center in Minority Institutions Program of the NIH (RR-03037); and the New Jersey Agriculture Experiment Station (paper D-01405-1-01).

REFERENCES

- 1.Berson S A, Yalow R S. Radioimmunoassays of peptide hormones in plasma. N Engl J Med. 1967;277:640–647. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196709212771208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cappellaro C, Baldermann C, Rachel R, Tanner W. Mating type-specific cell-cell recognition of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: cell wall attachment and active sites of a- and alpha-agglutinin. EMBO J. 1994;13:4737–4744. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06799.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cappellaro C, Hauser K, Mrsa V, Watzele M, Watzele G, Gruber C, Tanner W. Saccharomyces cerevisiae a- and alpha-agglutinin: characterization of their molecular interaction. EMBO J. 1991;10:4081–4088. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04984.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen M H, Shen Z M, Bobin S, Kahn P C, Lipke P N. Structure of Saccharomyces cerevisiae alpha-agglutinin. Evidence for a yeast cell wall protein with multiple immunoglobulin-like domains with atypical disulfides. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26168–26177. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.44.26168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daniels D L, Cohen A R, Anderson J M, Brunger A T. Crystal structure of the hCASK PDZ domain reveals the structural basis of class II PDZ domain target recognition. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:317–325. doi: 10.1038/nsb0498-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Nobel H, Lipke P N, Kurjan J. Identification of a ligand-binding site in an immunoglobulin fold domain of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae adhesion protein alpha-agglutinin. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:143–153. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.1.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doyle D A, Lee A, Lewis J, Kim E, Sheng M, MacKinnon R. Crystal structures of a complexed and peptide-free membrane protein-binding domain: molecular basis of peptide recognition by PDZ. Cell. 1996;85:1067–1076. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81307-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Du X P, Plow E F, Frelinger A L, O'Toole T E, Loftus J C, Ginsberg M H. Ligands “activate” integrin alpha IIb beta 3 (platelet GPIIb-IIIa) Cell. 1991;65:409–416. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90458-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dubs M C, Altschuh D, Van Regenmortel M H. Interaction between viruses and monoclonal antibodies studied by surface plasmon resonance. Immunol Lett. 1992;31:59–64. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(92)90011-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friguet B, Djavadi-Ohaniance L, Goldberg M E. Polypeptide-antibody binding mechanism: conformational adaptation investigated by equilibrium and kinetic analysis. Res Immunol. 1989;140:355–376. doi: 10.1016/0923-2494(89)90142-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fu Y, Rieg G, Fonzi W A, Belanger P H, Edwards J E, Jr, Filler S G. Expression of the Candida albicans gene ALS1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae induces adherence to endothelial and epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1783–1786. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1783-1786.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaur N K, Klotz S A. Expression, cloning, and characterization of a Candida albicans gene, ALA1, that confers adherence properties upon Saccharomyces cerevisiae for extracellular matrix proteins. Infect Immun. 1997;65:5289–5294. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.5289-5294.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaur N K, Klotz S A, Henderson R L. Overexpression of the Candida albicans ALA1 gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae results in aggregation following attachment of yeast cells to extracellular matrix proteins, adherence properties similar to those of Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 1999;67:6040–6047. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.6040-6047.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glaser R W, Hausdorf G. Binding kinetics of an antibody against HIV p24 core protein measured with real-time biomolecular interaction analysis suggest a slow conformational change in antigen p24. J Immunol Methods. 1996;189:1–14. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(95)00221-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenfield N J. Methods to estimate the conformation of proteins and polypeptides from circular dichroism data. Anal Biochem. 1996;235:1–10. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grigorescu A, Chen M-H, Zhao H, Kahn P C, Lipke P N. A CD2-based model of yeast alpha-agglutinin elucidates solution properties and binding characteristics. IUBMB Life. 2000;50:105–113. doi: 10.1080/713803692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoyer L L, Hecht J E. The ALS6 and ALS7 genes of Candida albicans. Yeast. 2000;16:847–855. doi: 10.1002/1097-0061(20000630)16:9<847::AID-YEA562>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoyer L L, Payne T L, Bell M, Myers A M, Scherer S. Candida albicans ALS3 and insights into the nature of the ALS gene family. Curr Genet. 1998;33:451–459. doi: 10.1007/s002940050359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huber W, Hurst J, Schlatter D, Barner R, Hubscher J, Kouns W C, Steiner B. Determination of kinetic constants for the interaction between the platelet glycoprotein IIb-IIIa and fibrinogen by means of surface plasmon resonance. Eur J Biochem. 1995;227:647–656. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnsson B, Lofas S, Lindquist G. Immobilization of proteins to a carboxymethyldextran-modified gold surface for biospecific interaction analysis in surface plasmon resonance sensors. Anal Biochem. 1991;198:268–277. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90424-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jonsson U, Fagerstam L, Ivarsson B, Johnsson B, Karlsson R, Lundh K, Lofas S, Persson B, Roos H, Ronnberg I, et al. Real-time biospecific interaction analysis using surface plasmon resonance and a sensor chip technology. BioTechniques. 1991;11:620–627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karlsson R. Real-time competitive kinetic analysis of interactions between low-molecular-weight ligands in solution and surface-immobilized receptors. Anal Biochem. 1994;221:142–151. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karlsson R, Michaelsson A, Mattsson L. Kinetic analysis of monoclonal antibody-antigen interactions with a new biosensor based analytical system. J Immunol Methods. 1991;145:229–240. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(91)90331-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kishore U, Leigh L E A, Eggleton P, Strong P, Perdikoulis M V, Willis A C, Reid K B. Functional characterization of a recombinant form of the C-terminal, globular head region of the B-chain of human serum complement protein, C1q. Biochem J. 1998;333:27–32. doi: 10.1042/bj3330027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koshland D E, Jr, Neet K E. The catalytic and regulatory properties of enzymes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1968;37:359–410. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.37.070168.002043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leung L L, Li W X, McGregor J L, Albrecht G, Howard R J. CD36 peptides enhance or inhibit CD36-thrombospondin binding. A two-step process of ligandreceptor interaction. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:18244–18250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lipke P N. Cell adhesion proteins in the nonvertebrate eukaryotes. Prog Mol Subcell Biol. 1996;17:119–157. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-80106-8_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lipke P N, Kurjan J. Sexual agglutination in budding yeasts: structure, function, and regulation of adhesion glycoproteins. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:180–194. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.1.180-194.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lipke P N, Terrance K, Wu Y S. Interaction of α-agglutinin with Saccharomyces cerevisiaea cells. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:483–488. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.2.483-488.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu C F, Kurjan J, Lipke P N. A pathway for cell wall anchorage of Saccharomyces cerevisiae α-agglutinin. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:4825–4833. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.7.4825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu C F, Montijn R C, Brown J L, Klis F, Kurjan J, Bussey H, Lipke P N. Glycosyl phosphatidylinositol-dependent cross-linking of alpha-agglutinin and beta 1,6-glucan in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell wall. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:333–340. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.3.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malmqvist M, Karlsson R. Biomolecular interaction analysis: affinity biosensor technologies for functional analysis of proteins. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 1997;1:378–383. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(97)80077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rini J M, Schulze-Gahmen U, Wilson I A. Structural evidence for induced fit as a mechanism for antibody-antigen recognition. Science. 1992;255:959–965. doi: 10.1126/science.1546293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roy A, Lu C F, Marykwas D L, Lipke P N, Kurjan J. The AGA1 product is involved in cell surface attachment of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell adhesion glycoprotein a-agglutinin. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:4196–4206. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.8.4196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35a.Shen, Z. M., L. Wang, H. Zhao, J. Kurjan, J. Pike, and P. N. Lipke. Delineation of functional regions within the subunits of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell adhesion molecule a-agglutinin. J. Biol. Chem., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Sreerama N, Woody R W. Protein secondary structure from circular dichroism spectroscopy. Combining variable selection principle and cluster analysis with neural network, ridge regression and self-consistent methods. J Mol Biol. 1994;242:497–507. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sreerama N, Woody R W. A self-consistent method for the analysis of protein secondary structure from circular dichroism. Anal Biochem. 1993;209:32–44. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Terrance K. Ph.D. dissertation. New York, N.Y: City University of New York; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Terrance K, Heller P, Wu Y S, Lipke P N. Identification of glycoprotein components of α-agglutinin, a cell adhesion protein from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:475–482. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.2.475-482.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Terrance K, Lipke P N. Pheromone induction of agglutination in Saccharomyces cerevisiaea cells. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:4811–4815. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.10.4811-4815.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Terrance K, Lipke P N. Sexual agglutination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1981;148:889–896. doi: 10.1128/jb.148.3.889-896.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wojciechowicz D, Lu C F, Kurjan J, Lipke P N. Cell surface anchorage and ligand-binding domains of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell adhesion protein α-agglutinin, a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:2554–2563. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.4.2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamaguchi M, Yoshida K, Yanagishima N. Isolation and partial characterization of cytoplasmic alpha agglutination substance in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 1982;139:125–129. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(82)80502-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yurchenco P D, Cheng Y S. Self-assembly and calcium-binding sites in laminin. A three-arm interaction model. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:17286–17299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao H. Ph.D. dissertation. New York, N.Y: City University of New York; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao, H., M. H. Chen, Z.-M. Shen, P. C. Kahn, and P. N. Lipke. Environmentally-induced conformational switching in the yeast cell adhesion protein, α-agglutinin. Protein Sci., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]