Abstract

Objectives

The COVID-19 pandemic presented new challenges for general practitioners’ (GPs’) mental health and well-being, with growing international evidence of its negative impact. While there has been a wide UK commentary on this topic, research evidence from a UK setting is lacking. This study sought to explore the lived experience of UK GPs during COVID-19, and the pandemic’s impact on their psychological well-being.

Design and setting

In-depth qualitative interviews, conducted remotely by telephone or video call, with UK National Health Service GPs.

Participants

GPs were sampled purposively across three career stages (early career, established and late career or retired GPs) with variation in other key demographics. A comprehensive recruitment strategy used multiple channels. Data were analysed thematically using Framework Analysis.

Results

We interviewed 40 GPs; most described generally negative sentiment and many displayed signs of psychological distress and burnout. Causes of stress and anxiety related to personal risk, workload, practice changes, public perceptions and leadership, team working and wider collaboration and personal challenges. GPs described potential facilitators of their well-being, including sources of support and plans to reduce clinical hours or change career path, and some described the pandemic as offering a catalyst for positive change.

Conclusions

A range of factors detrimentally affected the well-being of GPs during the pandemic and we highlight the potential impact of this on workforce retention and quality of care. As the pandemic progresses and general practice faces continued challenges, urgent policy measures are now needed.

Keywords: mental health, qualitative research, primary care, health policy, COVID-19

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

While there is growing international evidence demonstrating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on general practitioners’ (GPs’) well-being and much UK media coverage, this qualitative interview study provides much-needed research evidence of UK GPs’ lived experiences and well-being during COVID-19.

Overall, 40 GPs were sampled purposively to include GPs with different demographic and practice characteristics.

While there are no easy solutions to the problems highlighted, this research provides contextualised understanding of how these experiences may impact future workforce retention and the sustainability of health systems longer term.

Subgroup differences by gender and age are reported, highlighting a potential need for further research and support targeted at specific groups.

Findings are necessarily limited to the time of data collection (spring/summer 2021). Further tensions in general practice have since arisen, particularly regarding negative and misleading media portrayal.

Introduction

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, rising demands on UK National Health Service (NHS) general practitioners (GPs), including increasing work complexity and intensity and falling numbers of doctors, was leading to GP mental health difficulties1 and a growing gap between GP demand and supply.2 A total of 80% of the doctors participating in a British Medical Association (BMA) survey appear to be at high or very high risk of burnout,3 with research suggesting primary care doctors are at highest risk.4 5 Not only does chronic stress and burnout threaten the mental health of GPs, but it also presents challenges for the sustainability of the healthcare system and the quality of patient care. Pre-COVID-19, one in three GPs planned to leave medicine within 5 years6 and a shortage of 2500 GPs was estimated to increase to 7000 within 5 years if trends continued.2 The link between doctor well-being and patient safety has been demonstrated in a systematic review,7 while in general practice specifically, lower well-being has been associated with increased likelihood of reporting ‘near miss’ events and worse perceptions of patient safety.8

Clear new risks to workforce well-being occurred during the pandemic: GPs experienced rapid change, risks of infection, remote working and reductions in face-to-face patient care. A growing international evidence base has explored the impact of the pandemic on healthcare workforce well-being.9–15 Indeed, 31 studies in general practice were included in a recent systematic review of the international literature.16 While these studies highlight pressures during the pandemic and impact on GPs’ psychological well-being, just three research studies including UK GPs were identified. One of these studies explores experiences of GPs with long COVID, one focuses on one geographical location and one presents the findings of UK GPs alongside other countries.16

We sought to address this evidence gap by exploring the lived experience of UK GPs during COVID-19, and the pandemic’s impact on their psychological well-being.

Method

We adopted an exploratory qualitative methodology, conducting qualitative interviews to understand UK GPs’ lived experiences and well-being during COVID-19. While our analytical approach was inductive in nature and a predefined theoretical framework was not imposed, our approach was guided by our existing knowledge of the relevant literature. We interpret our findings within the policy context using Michael West’s ABC of doctors’ needs,17 which highlights the importance of doctors’ sense of autonomy, belonging and contribution in their working lives and is based on Deci and Ryan’s self-determination theory.18

Interviews were semi-structured in nature, using topic guides (see online supplemental file 1) to explore GPs’ well-being during the pandemic, encouraging reflections on their working lives and well-being before the pandemic, views around challenges during the pandemic, facilitators of improved working practices, future intentions, motivations and thoughts on how to improve GPs’ working lives.

bmjopen-2022-061531supp001.pdf (221KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

A multidisciplinary team developed and piloted topic guides in consultation with an expert panel comprising four GPs and a project steering committee consisting of an international expert in organisational psychology, NHS mental health and two senior Royal College of General Practitioner (RCGP) representatives. Three patient representatives were also consulted during the design and implementation of this research.

Sampling and recruitment

We sampled GPs purposively across three career stages: ‘early-career GPs’ (in final stages of training and first 5 years of practice); ‘established GPs’ and ‘late-career' GPs (including retired GPs returning to practice during COVID-19). We sampled for variation in key demographics including ethnicity, age, gender, contract type and local area characteristics (geographical spread, deprivation level and COVID-19 rates) using a comprehensive, multichannel recruitment strategy. Our initial recruitment approach through social media (Twitter) using a project infographic and shared by leading experts in the field, proved so successful that over 40 GPs offered to participate within 24 hours. In order to obtain maximum variation in participant characteristics and reduce the potential for bias, we also recruited through communications with the Yorkshire and Humber deanery, snowballing our networks of clinicians nationally, email circulation to the RCGP late career and recently retired group and emails directly to participants in the GP Worklife Survey who had indicated they would be willing to participate in research of this type.

Potential participants were asked to complete a brief survey to provide contact details and basic demographic information, and sent consent forms and participant information leaflets explaining the nature and rationale for the research. GPs meeting the sampling framework were contacted to arrange virtual interviews, conducted by LJ and CH via zoom or telephone. Informed verbal consent was obtained prior to commencing interviews. We provided a £100 honorarium to thank participants for their time.

Analysis

We used transcriptions and recordings to analyse data thematically, facilitated using NVivo V.12 data sorting software (QSR International, 2018). Our approach to analysis was inductive, with themes emerging from the data rather than using prespecified theory. We used framework analysis19 following the steps described in table 1. Two researchers (LJ and CH) coded the interviews independently, checking a 20% sample for consistency and meeting weekly to enable triangulation; refining the coding framework as analysis progressed. No member checking was needed.

Table 1.

Process of framework analysis

| Stage of analysis | Description |

| Managing the data | We managed transcriptions using Nvivo V.12 software (QSR International, 2018) to supplement the researchers’ analytical thinking and familiarisation with the data. |

| Familiarisation | Both researchers undertaking interviews (CH and LJ) immersed themselves in the data by reading and re-reading transcripts, listening to audio recordings and producing detailed notes for each interview in order to help facilitate the following analysis stages. |

| Identifying a thematic framework | Researchers independently developed two thematic frameworks and met on multiple occasions to discuss and refine these into one thematic framework. This was tested on four transcripts prior to use, and further iterations continued to be made through discussion with the study team as the coding developed. |

| Indexing the data | Both researchers then indexed, or coded, the interview data according to 10 themes and 95 subthemes which were identified in the thematic framework. Data were recoded where needed whenever revisions to the coding framework were made. |

| Charting | Once coding was complete, we explored the relationships between themes using mindmaps, research team discussions and creation of overarching themes, or ‘supercodes.’ This process identified six overarching themes made up of 30 subthemes. We also explored categories of participants, particularly focusing on relationships between career stage, gender, job role, ethnicity, previous or current experience of mental illness and working in a deprived geographical area. Qualitative analysis of the data was facilitated through mapping themes according to these key characteristics. |

| Mapping and interpretation | In order to go beyond the purely descriptive account of the data and develop wider meanings about links between phenomena and subgroups of participants, we mapped themes to build patterns in the data, bearing in mind the original research objectives and also exploring negative or deviant cases to explore alternative explanations. |

Reflexivity

We maintained a reflexive approach throughout the design and analysis stages to limit potential for preconceptions to influence research findings. All researchers were female, with non-medical backgrounds; it is possible that our experiences may have generated more open discussion among women participants or affected our interpretations of women GPs’ experiences. LJ and KB’s previous work on medical workplace culture and gendered norms may also have influenced this research process. To avoid the impact of such potential bias, we undertook researcher triangulation (during data collection and analysis) and consulted a committee of experts, GPs and patients in order to appropriately frame the topic guides for interviews, recruitment materials and user-test these approaches before wider rollout. During analysis, we sense checked our findings with stakeholders through meetings with our steering committee and informal discussions with GPs outside the committee in order to gain deeper understanding. While our analysis was inductive in nature, this research was undertaken simultaneously to our wider research projects on GP well-being, and is therefore underpinned by our knowledge of that evidence base.

Results

Sample characteristics

Interviews with 40 GPs took place between March and June 2021, lasting between 43 and 72 min. Participants were from a range of career stages: 13 ‘early career’, 19 ‘established’ and 8 ‘late career’ or retired GPs. Twenty GPs were aged 30–39, and we interviewed more women than men (29/40). There was a slightly higher proportion of white GPs in our sample to those reported nationally (67.5% compared with 56.6% nationally20). Further demographic characteristics can be found in table 2. Though we sampled according to a purposive sampling strategy, data saturation was reached.

Table 2.

Participant characteristics

| Career stage | N (%) |

| Early | 13 32.5 |

| Established | 19 47.5 |

| Late | 8 20.0 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 11 27.5 |

| Female | 29 72.5 |

| Age | |

| <30 | 3 7.5 |

| 30–39 | 20 50.0 |

| 40–49 | 9 22.5 |

| 50–59 | 6 15.0 |

| >60 | 2 5.0 |

| Ethnicity | |

| Ethnic minority groups | 10 25.0 |

| White British | 27 67.5 |

| White non-British | 3 7.5 |

| Location | |

| England—East | 3 7.5 |

| England—London | 5 12.5 |

| England—North East | 1 2.5 |

| England—North West | 3 7.5 |

| England—South East | 3 7.5 |

| England—South West | 4 10.0 |

| England—West Midlands | 5 12.5 |

| England—Yorkshire and Humber | 14 35.0 |

| Northern Ireland | 2 5.0 |

| Job role | |

| GP trainee | 6 15.0 |

| GP retainer | 1 2.5 |

| Salaried GP | 17 42.5 |

| GP partner | 14 35.0 |

| Retired GP | 2 5.0 |

| Clinical sessions | |

| Median (IQR) | 6 (3.63) |

| 1–4 | 11 27.5 |

| 5–7 | 16 40.0 |

| ≥8 | 9 22.5 |

| Retired | 2 5.0 |

| Unknown | 2 5.0 |

| Portfolio roles | 18 45.0 |

| Area demographics | |

| Highly deprived | 10 25.0 |

| Pockets of deprivation | 9 22.5 |

| Rural or semirural | 4 10.0 |

| Large elderly population | 4 10.0 |

| COVID-19 history | |

| Suspected COVID-19 | 8 20.0 |

| COVID-19 diagnosis | 4 10.0 |

GP, general practitioner.

Thematic findings

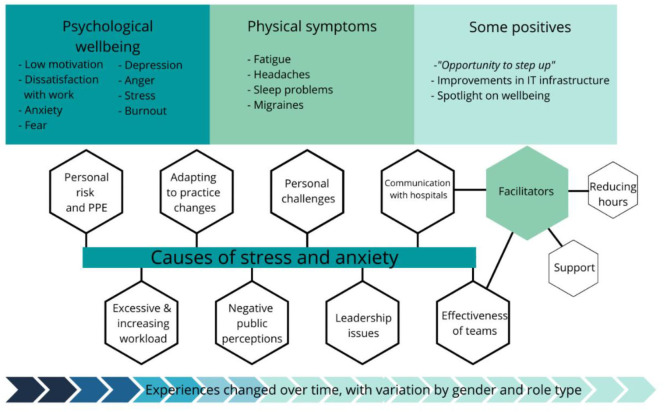

Overarching themes highlighting (1) the impact of the pandemic on GPs’ psychological well-being, (2) causes of stress and anxiety and (3) facilitators that improved GPs’ working lives are described. These are displayed graphically in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of the study findings.PPE: Personal protective equipment, IT: Information technology

Psychological well-being

Causes of stress and anxiety altered during the course of the pandemic. Many reflected on concerns at the start of the pandemic around managing adaptations to work (eg, movement to remote working and development of hot sites), and dealing with uncertainty around what lay ahead. GPs described fear of the unknown and potential risk to themselves and their families. Anxiety increased as levels of unmet patient need grew from the autumn of 2020 onwards; there were concerns about future demand, as well as support available for patients’ mental and physical needs.

GPs talked about low motivation, dissatisfaction with work, frustration and anger during interviews, which they described as having been particularly difficult during the winter of 2020. For some, this related to general stress of the pandemic (social isolation, lack of enjoyment in things and pressures of homeschooling). Work-related feelings of stress and anxiety were, however, very widely expressed. Often referred to as being overwhelmed, GPs described their work as ‘all consuming’ (Female salaried GP2) and having a ‘background level of anxiety’ (Female GP3 partner).

Five GPs reported having clinically diagnosed mental health problems; all were female (though with variation in age and job roles). The following quotation displays signs characteristic of burnout:

You’re just filling and filling the bucket, and at some point it will overspill. And you've just got to hope that you don't miss something really important… So I want to remove myself from that situation for at least a period of time, just while I rebuild my armour I suppose and see if I want to do it again. Female salaried GP34

Many GPs described the negative impact on their families and relationships, and held concerns about quality of patient care due to increasing impatience or fear of making mistakes due to extreme fatigue. Difficulties with sleep and fatigue were common. A minority of GPs (one of whom experienced long COVID) described difficulties with concentration, resulting in driving incidents.

I think the work, particularly in the last few months, has left me pretty exhausted, and, you know, I kind of come home in the afternoon, or in the evening, and I’m pretty useless to my wife, or to anyone else really. Male salaried GP28

decision fatigue… towards the end of the day, I’d get a phone call at five o’clock, with someone talking about how low they’re feeling, and they need a bit of support… at the end of the day, I couldn’t give the same support to that patient that I perhaps would have done, if it was eight o’clock that I was speaking to them. Male salaried GP4

Stigma and presenteeism

GPs tended to downplay experiences of stress and, despite the impact on their mental well-being, many did not seek formal support:

I am normally very ‘just get on with it’ in life. I massively took a dive. Just very anxious, not in a way that I needed any kind of help… but just completely changed who I was. I was a bit of a mess, much like most of us were. Female trainee GP26

GPs described reluctance to seek support because of stigma and guilt from taking time off as this would burden their colleagues without a ‘buffer in the system’ (Female GP partner3). All had worked additional clinical sessions to cover absences, which increased during the pandemic due to mental well-being or self-isolation of colleagues. This appeared more problematic for GP partners and smaller practices.

I think we all were put under huge stress and people have gone off sick that have never been sick. And I think people have just cracked up basically, but the trouble is, it’s like a domino effect Female GP partner24

Positive emotions

Approximately half of participants expressed some element of positivity when reflecting on their well-being during the pandemic, though negative comments around challenges dominated discussions. Positive comments related to their enjoyment of work and seeing the pandemic as providing a catalyst for long-needed change. Some recently qualified GPs welcomed the challenge and ability to ‘step up’ during the pandemic.

In all honesty, that time felt really positive. It felt really refreshing. It felt empowering and as though…we’d known that general practice was struggling and not fit for purpose and we knew we needed to make some changes, but no-one could agree on the changes. And we’d been having these conversations for what, ten years? And not getting anywhere. And all of a sudden overnight we had to change, and we all did and it was fine. Female salaried GP8

Causes of stress and anxiety

Personal risk

Most interviewees reported fear of putting themselves and family members at risk, particularly at the start of the pandemic. GPs in high-risk categories (older GPs, GPs from minority ethnic groups or those with asthma) described particular concerns. For example, a GP from an ethnic minority group described:

I didn’t feel I was particularly protected in any way, you know, they just expect you to get on with it Male GP partner7

Changing guidance around implementation of ‘hot’ sites, use of and access to Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) heightened anxiety. GPs were frustrated and felt neglected compared with hospital colleagues due to lower standards of PPE, even in COVID-19 ‘hot sites’.

The psychiatrists were being fitted with FFP3 masks, specialist masks… working at home doing telephone reviews, and us in primary care and our district nurses… going out to visit cancer people were given flimsy surgical masks and told that these will be fine, get on with it… we felt disappointed that we were neglected Female GP partner30

Workload

GPs described workload issues before COVID-19, with treatment advances and shifting care out of hospitals adding pressure. The vast majority of GPs felt their workload had increased during the pandemic, reducing their well-being further.

It’s a different world, isn’t it? I mean I think I thought I was busy [before COVID], but I didn't have a clue what busy was, basically. I just can't believe the workload explosion since COVID… it was stressful [before COVID], but I had my head above water. Female GP partner24

Reports of working 12–14-hour days and additional unpaid administration sessions were commonplace. Patient demand for urgent on-the-day appointments was described as unmanageable, and practices also struggled to meet ‘non-urgent’ demand within reasonable timeframes.

Most days there were 50 or 60 contacts on that appointment list where the RCGP says that they reckon the safe limit is about 30. So probably double. Female salaried GP8

GP partners, in particular, commented on increases in administrative workload at the start of the pandemic; reading and implementing sometimes contradictory guidance from multiple sources which evolved daily. At the start of the pandemic, though, the increased management workload was balanced by initial reduced patient demand. Management workload increased again during the planning and implementation of the vaccination programme, with additional time pressures from cleaning and PPE measures.

GPs reflected that patient demand became most challenging from the end of summer 2020 onwards, particularly from late presentations with more serious pathologies, leading to greater workload and emotional strain. Higher demand from patients with mental health problems also increased workload, alongside difficulties in consulting these patients remotely and lack of support services:

Our mental health service is shocking… mental health services play ping pong between themselves… IAPT say, oh, too severe for us, and the secondary care mental health service say, oh, no, not severe enough for us, we’re not dealing with that. And then they just fall into this black hole. Female GP partner35

Practice changes

Participants described the many changes that the pandemic had brought about, including new triage systems, use of remote consultations, the vaccination rollout and changes for trainees. Some associated these changes with stress and increased workload, but there was a general sentiment that the pandemic had provided a positive impetus for technological development. GPs described the importance of triage systems for prioritisation and reallocating patients during staff absences. E-consultation systems were perceived to increase demand due to greater accessibility:

Now eConsults have come in there’s no barrier… there’ll be 200 eConsults on a Monday that we have to deal with as well as all the other general practice workload and the vaccination programme and PCNs, and it’s just really unsustainable and unsafe. Female GP partner30

There were mixed emotions around the movement to telephone and video consultations, which were viewed positively for minor conditions, reducing attendances and enabling more focused face-to-face appointments. GPs in multisite practices covering large geographical areas described their increased ability to share workload across practices. GPs also described feeling isolated, ‘decision fatigue’ and felt that consultations lacked personal contact with patients, which had encouraged their career choice. While telephone consultations were well received among younger and working patients, there were concerns around inequalities in access and potential missed diagnoses. These concerns were particularly expressed by trainee and early-career GPs.

Vaccination rollout

The vaccination programme was described as a great morale booster, coming at a time when many GPs and the wider public needed hope. GPs described working additional hours to manage vaccinations, but with a sense of teamwork and pride.

There was a point when we were doing the 80 year olds where you had to vaccinate 14 people to save one life. And I'm feeling tearful about it even now. Like just the actual practical difference that you could make in a terrible situation. Female salaried GP34

Practices had also faced workload increases due to patient queries about vaccinations and GPs expressed frustration with public messaging around the vaccination rollout.

Public perceptions and leadership

Despite the initial public appreciation for the NHS at the start of the pandemic, GPs described how this had been eroded at the time of conducting our interviews with negative public perceptions of general practice greatly impacting GPs’ well-being and being one of the most widely cited causes of stress. Patients facing problems with access or referrals became increasingly frustrated, and GPs felt this was fuelled by negative media portrayals, described by participants as ‘GP bashing’. GPs described ‘simmering discontent amongst communities’ (Male salaried GP28) who they felt had been ‘whipped up to a frenzy by the government and by the media’ (Female GP partner24).

Several GPs described positively the outpouring of appreciation for NHS workers at the beginning of the pandemic, but most felt that public appreciation was eroded due to inaccurate messaging from the government, NHS England and the media about general practice being 'closed':

That was really upsetting at one point, thinking that people thought we were closed. I was like, I’ve been working my socks off, I’ve been working at COVID hubs or I’ve been doing back-to-back telephone consulting… no matter what we do or what we try, people just assume that we’re not working hard enough. Female trainee GP10

GPs expressed frustration around national decision-making, which they felt had directly risked NHS capacity and heightened anxiety in anticipation of repeat waves of the pandemic. Communication about delays in out-patient appointments and routine surgery was seen as vital, as were government campaigns encouraging health awareness about common illnesses and more signposting to appropriate specialists.

Retired GPs described lengthy bureaucratic processes at the start of the pandemic, which prohibited them from returning to practice; certain training requirements were viewed as unnecessary for remote working and one described the process taking 2 months. Two volunteered to support practices and vaccinations, but their offers were declined.

Wider collaboration

Almost half of the interviewees felt that the pandemic offered opportunities to foster collaboration across primary care networks (PCNs), hospitals, community and wider services. A greater sense of camaraderie and improved working across PCNs was reported, with groups of practices ‘pulling together’ during the vaccine rollout.

A minority reported greater access to specialist support from hospitals and some actually described conflict between the primary and secondary care. This related to lengthy hospital waiting lists and some service closures increased workload for GPs, who felt they were the only support for some high-risk patients:

Eating disorder services stopped. They just stopped. So for a nine month period any new referrals, you couldn't refer. And there wasn't an alternative. So we set up a high risk list to look after the highest risk eating disorders patients. … Mental health services, closed to routine referrals. They would only see suicidal people. Female salaried GP34

General practice teams

Experiences and perceptions of the effectiveness of practice teams varied, affecting GP well-being and ability to cope with challenges. Isolation from teams was problematic particularly for early-career GPs who lacked support and found it difficult to integrate. Concerns were raised around trainees’ well-being, feeling that they had been used ‘as cannon fodder’ in front-line hospital roles and had faced much disruption to their training. Disproportionate numbers of women raised difficulties with teams.

The majority of GPs cited examples of good teamworking and described a sense of pulling together during the pandemic. An increased focus on personal and team mental well-being was reported, though some participants were disenchanted with initiatives that sought to improve ‘resilience’ as they felt that this placed the onus of responsibility at an individual rather than structural level. Others suggested well-being support was perhaps more easily adopted by larger practices with greater infrastructure. Team ‘huddles’ were used to debrief on complex cases, provide social support and share anxieties, but small rooms and safe distancing in some practices prohibited in-person staff meetings. Shared breaks provided opportunities to raise difficulties informally, which was important to some who felt less inclined to seek formal support either due to workload pressures or stigma.

Personal challenges

Negative financial impacts of the pandemic were described by some GPs, mostly due to reduced availability of locum work, and one GP from a University practice described a reduction in practice earnings and associated stress due to reduced student/patient numbers. Challenges of homeschooling and reduced access to childcare were discussed by many GPs (almost all of whom were women); they described juggling telephone consultations and administrative work with childcare:

So I was at home trying to get through more patients than normal remotely, trying to learn the technology and I had my children at home, so it was huge. I can remember feeling just running on adrenaline and just feeling constantly stressed. Female GP partner30

Facilitators

Informal and formal support

Interviewees sought informal support through family and friends, colleagues and peers. They described the benefits of talking to other medics who could relate to their experiences; this was particularly important to trainees, some of whom were isolated from family and other networks.

If it wasn’t for the support of my own GP trainees… I think I would have just… become even lower in mood. Because the trainees were going through a similar thing, some of them, and they couldn’t go back to their own families… So we just came [to the hospital] during Christmas time and helped give [children] gifts, and it was something to do to keep us occupied, otherwise we would just be sitting by ourselves at home Female trainee GP10

There appeared to be good awareness of the different formal support structures available; ranging from coaching and mentoring support (which several participants had used) to more formal mental health support. Only two male participants discussed using these support services, and, similarly, gender differences were apparent in discussion of approaches to ‘self-care’; with comments predominately made by women.

Reducing clinical hours and future plans

Some GPs (mostly women) had reduced their clinical sessions or developed portfolio careers in order to manage work pressure and support well-being. There was greater variation in the number of clinical sessions reported by women (median: 6, IQR: 3.0) than men (median 6, IQR 1.88) as some women had low numbers of clinical sessions, described as a reaction to risk of burnout and seeking work–life balance.

I only work three sessions, and the reason for that is… I'm busy the rest of my time. It’s just because I physically can't do those sessions. They are brutal and that’s the most that I've found I could tolerate without being ill essentially… Ten years ago, I worked eight sessions. I didn't find that difficult. But if I tried to work eight sessions now, I would literally fall over. It wouldn't be feasible. Female salaried GP34

Portfolio careers (eg, including teaching and mentoring) provided an opportunity to achieve greater balance, while others planned to specialise, become locums, work abroad or retire. GPs were concerned about retention, particularly of those approaching retirement. Greater use of retainer schemes or a phased retirement stage were seen as opportunities to reduce workload, stress and retain GPs.

Discussion

Summary

Our interviewees offered in-depth accounts of their experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic, highlighting an exacerbation of difficulties that were already causing challenges in general practice prior to the pandemic. For some, this had led to dissatisfaction with work and mental health problems, or plans to reduce clinical or overall working hours, take on locum work, work abroad or retire. GPs described feelings characteristic of burnout and raised concerns around quality of patient care.

Pressures changed as the pandemic evolved. Early on, GPs experienced stress, rapid change, uncertainty and personal risks, but this time also catalysed technological change. Later, GPs faced anxiety relating to unmet patient need, delayed presentations and growing demand, particularly for mental health support, while negative patient perceptions and media portrayal of practices being ‘closed’ during this time increased GPs’ work stress and reduced job satisfaction. There were calls for improved public relations from leadership bodies in order to counteract inaccuracies in the media and to improve health literacy, particularly as uptake of e-consultation services was perceived as increasing patient demand.

A greater sense of camaraderie and working across Primary Care Networks (PCNs) was reported, particularly to deliver vaccines. Effective team working was seen as vital and GPs welcomed an increasing focus on well-being. They also, however, described a culture of presenteeism, exacerbated during the pandemic due to staff absences and, for some, a sense of stigma around doctors’ mental health.

Comparison with the existing literature

While this research outlines key sources of stress for GPs that have been the subject of much recent commentary, there is a lack of qualitative research exploring UK GPs’ psychological well-being during the pandemic. This research also offers insights into potential subgroup variations. International literature highlights similar trends in GP well-being during the pandemic—doctors from varied settings report increased rates of burnout, related to high workload, job stress, time pressure and limited organisational support.16 21 International studies have found higher stress in general practice doctors compared with other healthcare workers and settings.11 22 23 The expanding public commentary and campaigns from UK doctor groups highlight the need to support the GP workforce.24

Subgroup variations in GPs’ experiences are important to understand as workforce pressures continue. Our research revealed different effects on men and women GPs and different use of support services. This is consistent with the international literature, which reports gender differences in stress, burnout, anxiety and depression10 22 23 25–28 and greater job strain among women in dual-doctor marriages during the pandemic.29 These differences may also arise as a result of gendered social norms around willingness to disclose difficulties, or due to socially constructed gender roles in the home that proliferated during COVID-19 lockdowns, negatively impacting women in employment.30 31 Our research also suggests gender differences may exist in GPs’ perceptions around effective team working, perhaps highlighting women’s differential support needs or expectations. Women may require targeted interventions to support their well-being and encourage continued participation, particularly as they were more likely to report future plans to reduce clinical sessions or adopt portfolio roles. GP partners may also require targeted support as they described greater pressures associated with management workload due to changes to service delivery, staff shortages and vaccination rollout, which supports other recent studies showing an association between older age and higher stress in GPs.26 32 33 Further research may be needed to explore recently qualified and trainee GPs’ experiences as our findings suggest they have faced differing challenges that may affect longer-term retention and well-being.

Strength and limitations

This research provides rich and contextualised understanding of the experiences of a varied sample of GPs during the pandemic, which our recent systematic review16 identified as lacking from a UK setting. While there may be selection bias in the views expressed by GPs willing to share experiences, for example, GPs experiencing particular difficulties may have been more willing to participate, our interview findings are consistent with other international research and wider commentary on this topic. Our findings are necessarily limited to the time of data collection (spring/summer 2021); further tensions in general practice have since arisen, particularly regarding negative and misleading media portrayal.34

Implications for research, policy and practice

This research demonstrates the effect of the pandemic on GP well-being, with potential wider impacts, for example, around workforce retention and patient safety; highlighting a need for national and local intervention. A report for the General Medical Council (GMC)17 described the ‘ABC of doctors’ needs’, advising that doctors’ sense of autonomy, belonging and competence need to be promoted for them to thrive in their working lives. All three components have been threatened during the pandemic. GPs’ ability to control and influence their work has reduced, and patient frustrations and media blaming of GPs has affected their sense of belonging and competence. There is a need for policy to support GPs, prevent work stress and foster collaborations across wider teams.

Further research could explore these findings more widely through quantitative methods, preferably with some comparison with prepandemic well-being scores. E-consultation systems, which appear to have increased demand, could be further evaluated, as should schemes to supplement the GP workforce with other non-medical staff through the Additional Roles Reimbursement Scheme that formed part of UK GP contract revisions.35

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic created some positive impacts on general practice—changing working systems, increasing wider team working and placing a spotlight on staff well-being. Nevertheless, a range of factors affected the well-being of GPs detrimentally during the pandemic, and substantial challenges to GPs remain. This could affect workforce retention, quality of care and the sustainability of health systems longer term. Targeted support strategies may be required to address the subgroup variations, particularly the apparently more detrimental effects on women and on early-career GPs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the general practitioners (GPs) who gave their time and support through participating in this research. We would like to thank the members of our Project Steering Committee meeting for their contributions throughout the design and conduct of this study: Professor Dame Clare Gerada, Professor Michael West CBE, Professor Michael Holmes and our Patient and Public Representatives for their contributions throughout: Patricia Thornton, Stephen Rogers and Emma Williams. We also thank Dr Shanthi Antill, Dr Madeleine Bradman and Dr Drew Bradman for their contributions during the design and development of this study, and Professor Katherine Checkland and Professor Matt Sutton for supporting the project and enabling recruitment of participants through the GP Worklife Survey.

Footnotes

Twitter: @KBloor

Contributors: This study was designed and conceived by LJ and KB. LJ and CH conducted interviews and qualitative analysis. LJ wrote the first draft of this manuscript, to which all authors commented. All authors have read and agreed the final version. LJ is study guarantor.

Funding: This report is independent research commissioned and funded by the Department of Health and Social Care NIHR Policy Research Programme (Exploring the impact of COVID-19 on GPs’ wellbeing, NIHR202329). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Method section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Materials and data used for the conduct of this research are available from the study authors on request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Department of Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee approval was granted in November 2020 (HSRGC/2020/SC/001). National Health Service (NHS) ethical and Health Research Authority approval was not required as we studied the experiences of staff recruited through methods not involving NHS organisations.

References

- 1.Riley R, Spiers J, Chew-Graham CA, et al. “Treading water but drowning slowly”: what are gps’ experiences of living and working with mental illness and distress in england? A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2018;8:e018620. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.King’s Fund . Closing the gap report. chapter 7: modelling the impact of reform and funding on nursing and GP shortages. 2019. Available: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/2019-03/closing-the-gap-health-care-workforce-full-report.pdf#page=107

- 3.BMA . Caring for the mental health of the medical workforce. 2019. Available: https://www.bma.org.uk/media/1365/bma-caring-for-the-mental-health-survey-oct-2019.pdf

- 4.GMC . The state of medical education and practice in the UK. 2019. Available: https://www.gmc-uk.org/about/what-we-do-and-why/data-and-research/the-state-of-medical-education-and-practice-in-the-uk

- 5.McKinley N, McCain RS, Convie L, et al. Resilience, burnout and coping mechanisms in UK doctors: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2020;10:e031765. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibson J, Sutton M, Spooner S, et al. Ninth national GP worklife survey, university of manchester: policy research unit in commissioning and the healthcare system manchester centre for health economics. 2018.

- 7.Hall LH, Johnson J, Watt I, et al. Healthcare staff wellbeing, burnout, and patient safety: a systematic review. PLoS One 2016;11:e0159015. 10.1371/journal.pone.0159015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall LH, Johnson J, Watt I, et al. Association of GP wellbeing and burnout with patient safety in UK primary care: a cross-sectional survey. Br J Gen Pract 2019;69:e507–14. 10.3399/bjgp19X702713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Monte C, Monaco S, Mariani R, et al. From resilience to burnout: psychological features of italian general practitioners during COVID-19 emergency. Front Psychol 2020;11:567201. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.567201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dutour M, Kirchhoff A, Janssen C, et al. Family medicine practitioners’ stress during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Fam Pract 2021;22:36. 10.1186/s12875-021-01382-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rossi R, Socci V, Pacitti F, et al. Mental health outcomes among healthcare workers and the general population during the COVID-19 in italy. Front Psychol 2020;11:608986. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.608986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sitanggang FP, Wirawan GBS, Wirawan IMA, et al. Determinants of mental health and practice behaviors of general practitioners during COVID-19 pandemic in Bali, Indonesia: a cross-sectional study. Risk Manag Healthc Policy 2021;14:2055–64. 10.2147/RMHP.S305373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sotomayor-Castillo C, Nahidi S, Li C, et al. General practitioners’ knowledge, preparedness, and experiences of managing COVID-19 in australia. Infect Dis Health 2021;26:166–72. 10.1016/j.idh.2021.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ta SB, Ozceylan G, Ozturk GZ, et al. Evaluation of job strain of family physicians in COVID-19 pandemic period- an example from turkey. J Community Health 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trivedi N, Trivedi V, Moorthy A, et al. Recovery, restoration, and risk: a cross-sectional survey of the impact of COVID-19 on GPs in the first UK City to lock down. BJGP Open 2021;5:BJGPO.2020.0151. 10.3399/BJGPO.2020.0151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jefferson L, Golder S, Heathcote C, et al. GP wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 2022;72:e325–33. 10.3399/BJGP.2021.0680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.West M, Coia D. GMC report: caring for doctors, caring for patients: how to transform UK healthcare environments to support doctors and medical students to care for patients. 2019. Available: https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/caring-for-doctors-caring-for-patients_pdf-80706341.pdf

- 18.Deci PA, Lopez LM, Robinson JD, et al. Computer prediction of serum theophylline concentrations in ambulatory patients. Ther Drug Monit 1985;7:421–5. 10.1097/00007691-198512000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bryman A, Burgess RG. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 1994. 10.4324/9780203413081 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.General Medical Council . The state of medical education and practice in the UK: 2020. reference tables - table 19. 2020. Available: https://wwwgmc-ukorg/-/media/documents/gmc-somep-2020-reference-tables-about-the-register-of-medical-practitioners_pdf-84716406pdf

- 21.Morgantini LA, Naha U, Wang H, et al. Factors contributing to healthcare professional burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic: a rapid turnaround global survey. PLoS One 2020;15:e0238217. 10.1371/journal.pone.0238217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lange M, Joo S, Couette PA, et al. Impact on mental health of the COVID-19 outbreak among general practitioners during the sanitary lockdown period. Ir J Med Sci 2022;191:93–6. 10.1007/s11845-021-02513-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ortega-Galán ÁM, Ruiz-Fernández MD, Lirola M-J, et al. Professional quality of life and perceived stress in health professionals before COVID-19 in Spain: primary and hospital care. Healthcare (Basel) 2020;8:484. 10.3390/healthcare8040484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.BMA . COVID-19 workload prioritisation unified guidance. London, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stafie CS, Profire L, Apostol MM, et al. The professional and psycho-emotional impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical care-a romanian gps’ perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:1–14. 10.3390/ijerph18042031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vilovic T, Bozic J, Vilovic M, et al. Family physicians’ standpoint and mental health assessment in the light of COVID-19 pandemic-a nationwide survey study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:1–17. 10.3390/ijerph18042093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baptista S, Teixeira A, Castro L, et al. Physician burnout in primary care during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study in portugal. J Prim Care Community Health 2021;12:21501327211008437. 10.1177/21501327211008437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Monterrosa-Castro A, Redondo-Mendoza V, Mercado-Lara M. Psychosocial factors associated with symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder in general practitioners during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Investig Med 2020;68:1228–34. 10.1136/jim-2020-001456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soares A, Thakker P, Deych E, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on dual-physician couples: a disproportionate burden on women physicians. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2021;30:665–71. 10.1089/jwh.2020.8903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adisa TA, Aiyenitaju O, Adekoya OD. The work–family balance of British working women during the COVID-19 pandemic. JWAM 2021;13:241–60. 10.1108/JWAM-07-2020-0036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martucci S. He’s working from home and I’m at home trying to work: experiences of childcare and the work-family balance among mothers during COVID-19. J Fam Issues 2023;44:291–314. 10.1177/0192513X211048476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Filfilan NN, Alzhrani EY, Algethamy RF, et al. Psychosocial impact of COVID-19 on family physicians in the kingdom of saudi arabia. World Family Medicine 2020;18:91–7. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zeng X, Peng T, Hao X, et al. Psychological distress reported by primary care physicians in China during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychosom Med 2021;83:380–6. 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pearce C. GPs fear mail campaign for ‘default’ face-to-face appointments will fuel abuse. 2021. Available: https://wwwpulsetodaycouk/news/breaking-news/gps-fear-mail-campaign-for-default-face-to-face-appointments-will-fuel-abuse/

- 35.NHS England and NHS Improvement . Network contract directed enhanced service: guidance for 2020/21 in england. 2020. Available: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/network-contract-des-guidance-2020-21.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-061531supp001.pdf (221KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Materials and data used for the conduct of this research are available from the study authors on request.