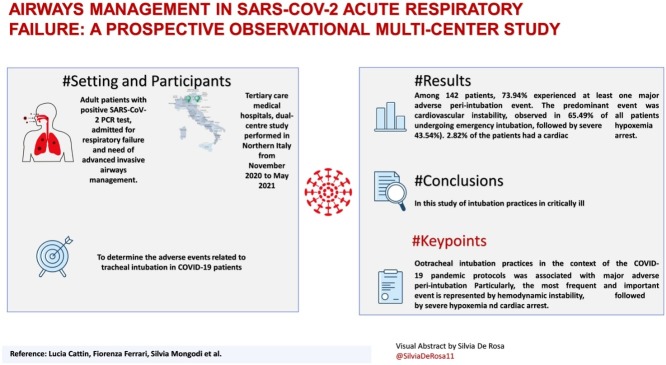

Graphical abstract

Abbreviations: ETT, Emergency Endotracheal intubation; COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; SARS-Cov2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; HR, heart rate; ICU, intensive care unit; SpO2, Peripheral oxygen saturation; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; RR, respiratory rate; PaO2/FiO2, arterial partial oxygen pressure / fraction of inspired oxygen; HFNO, High flow nasal oxygen; CPAP, continuous positive airways pressure; NIV, noninvasive ventilation; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; ECG, electrocardiography; EtCO2, end-tidal carbon dioxide; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval

Keywords: Airway management, Critical care, Respiratory failure, SARS-CoV infection, Tracheal intubation

Abstract

Objective

Few studies have reported the implications and adverse events of performing endotracheal intubation for critically ill COVID-19 patients admitted to intensive care units. The aim of the present study was to determine the adverse events related to tracheal intubation in COVID-19 patients, defined as the onset of hemodynamic instability, severe hypoxemia, and cardiac arrest.

Setting

Tertiary care medical hospitals, dual-centre study performed in Northern Italy from November 2020 to May 2021.

Patients

Adult patients with positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test, admitted for respiratory failure and need of advanced invasive airways management.

Interventions

Endotracheal Intubation Adverse Events.

Main variables of interests

The primary endpoint was to determine the occurrence of at least 1 of the following events within 30 minutes from the start of the intubation procedure and to describe the types of major adverse peri-intubation events: severe hypoxemia defined as an oxygen saturation as measured by pulse-oximetry <80%; hemodynamic instability defined as a SBP 65 mmHg recoded at least once or SBP < 90 mmHg for 30 minutes, a new requirement or increase of vasopressors, fluid bolus >15 mL/kg to maintain the target blood pressure; cardiac arrest.

Results

Among 142 patients, 73.94% experienced at least one major adverse peri-intubation event. The predominant event was cardiovascular instability, observed in 65.49% of all patients undergoing emergency intubation, followed by severe hypoxemia (43.54%). 2.82% of the patients had a cardiac arrest.

Conclusion

In this study of intubation practices in critically ill patients with COVID-19, major adverse peri-intubation events were frequent.

Clinical Trial registration

www.clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT04909476

Abstract

Objetivo

Pocos estudios han informado las implicaciones y los eventos adversos de realizar una intubación endotraqueal para pacientes críticos con COVID-19 ingresados en unidades de cuidados intensivos. El objetivo del presente estudio fue determinar los eventos adversos relacionados con la intubación traqueal en pacientes con COVID-19, definidos como la aparición de inestabilidad hemodinámica, hipoxemia severa y paro cardíaco.

Ámbito

Hospitales médicos de atención terciaria, estudio de doble centro realizado en el norte de Italia desde noviembre de 2020 hasta mayo de 2021.

Pacientes

Pacientes adultos con prueba PCR SARS-CoV-2 positiva, ingresados por insuficiencia respiratoria y necesidad de manejo avanzado de vías aéreas invasivas.

Intervenciones

Eventos adversos de la intubación endotraqueal.

Principales variables de interés

El punto final primario fue determinar la ocurrencia de al menos 1 de los siguientes eventos dentro de los 30 minutos posteriores al inicio del procedimiento de intubación y describir los tipos de eventos adversos periintubación mayores. : hipoxemia severa definida como una saturación de oxígeno medida por pulsioximetría <80%; inestabilidad hemodinámica definida como PAS 65 mmHg registrada al menos una vez o PAS < 90 mmHg durante 30 minutos, nuevo requerimiento o aumento de vasopresores, bolo de líquidos > 15 mL/kg para mantener la presión arterial objetivo; paro cardiaco.

Resultados

Entre 142 pacientes, el 73,94% experimentó al menos un evento periintubación adverso importante. El evento predominante fue la inestabilidad cardiovascular, observada en el 65,49% de todos los pacientes sometidos a intubación de urgencia, seguido de la hipoxemia severa (43,54%). El 2,82% de los pacientes tuvo un paro cardíaco.

Conclusión

En este estudio de prácticas de intubación en pacientes críticos con COVID-19, los eventos adversos periintubación mayores fueron frecuentes.

Registro de ensayos clínicos

www.clinicaltrials.gov identificador: NCT04909476

Palabras clave: Manejo de la vía aérea, Cuidado crítico, Insuficiencia respiratoria, Infección por SARS-CoV, Intubación traqueal

Introduction

COVID-19 pneumonia

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is characterized mainly by moderate/severe pneumonia due to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)1 in 42% of patients, and among them 61–81% of patients require intensive care unit (ICU) admission.2 COVID-19 pneumonia, and related hypoxemia and desaturation patterns, are atypical and not comparable to that of the “standard” acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) patients, as these patients show a low arterial partial oxygen pressure / fraction of inspired oxygen (PaO2/FiO2) ratio and initially higher compliance and pulmonary shunt fraction.3

Emergency Endotracheal intubation in COVID-19

The Emergency Endotracheal intubation (ETT) of SARS Cov2 patient is a high-risk procedure and represent an additional challenge to all intensivists due to barrier enclosures.4 Silent hypoxia often leads to late intubation which is linked to a high risk of complications. Non-survivors showed worse blood gas analyzes than survivors, both before and after intubation.5 Few studies reported the implications and adverse events of performing endotracheal intubation for critically ill COVID-19 patients admitted to ICUs.6 The choice of supplementary oxygen delivery interface is challenging and the decision to provide invasive ventilatory support is crucial.

Preoxygenation in COVID-19

The application of non-invasive support, with e.g. as high-flow nasal oxygen (HFNO), continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) and non-invasive ventilation (NIV), might correct hypoxemia and could avoid endotracheal intubation.7 The Italian outbreak experience resulted in a series of clinical protocols, suggesting the use of a short NIV trials with the need of intubation with a PaO2/FiO2 below 150.8 In this setting, it is advocated to prefer anticipated endotracheal intubation in order to minimize related complications.8 In the setting of critically ill-patients’ intubation, hypoxia, hemodynamic failure and cardiac arrest are common and well described events and given the COVID-19 physio-pathological evidence, these might be much more common in this context due to limited safe apnea time and poor oxygenation reserve.9 The aim of the present study was to determine the incidence of major adverse events related to tracheal intubation in COVID-19 patients defined as the onset of severe hypoxemia, hemodynamic instability and cardiac arrest within 30 minutes from the procedure

Patients and Methods

Study design and setting

This was a prospective, observational, dual-center study. Data were collected prospectively on patients admitted into two ICUs.

The study was designed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The ethics committees waived the need for written consent, allowing constant verbal consent (N° 125/20 of December 15, 2020). This was attained from all participants after explaining purposes, significance and advantages of the research by the trained data collectors and through a covering letter provided to each respondent. Patients were also informed that they had the right to withdraw from the study at any time. For each enrolled patient, their personal information was recorded and kept in a secure folder. To protect their privacy, patients’ information were only accessible to the researchers. Reporting was adapted from the STROBE checklist for observational research.10 The study was registered (ClinicalTrial.Gov Trials Register NCT04909476) on June 01, 2021.

Participants

All patients admitted for respiratory failure that needed advanced airways management were eligible for the study. Inclusion criteria were: 18 years of age and older; a positive SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test; intubation for respiratory failure or muscle exhaustion. Exclusion criteria were:

-

-

a negative SARS-CoV-2 PCR test;

-

-

intubated outside the hospital, thus secondary transfer;

-

-

intubated because of a cardiac arrest;

-

-

undergoing general anaesthesia for surgery;

-

-

incomplete data for enrollment.

All intubations were performed by attending physiscian specialized in anesthesia and intensive care or by residents under supervision.All anesthesia and intensive care residents had at least 4 yr of intraoperative anesthesiology experience.

Variables and measurements

Demographic variables and data about the procedure were collected prospectively for all patients at intubation using a Case Report Form (CRF). Hemodynamic parameters and temperature were measured continuously through invasive monitoring. Pre-procedural collected data included date and time of the intubation, the level of monitoring, patient’s parameters, ongoing vasoactive drugs and oxygen delivery method. Before the procedure patients were evaluated for anticipated difficult airways, according to SIAARTI task force Recommendation, and based on carefully assessment of the need for tracheal intubation, blood gas analysis and radiological findings.11 Healthcare professional performance data included the number of attempts at intubation, the expertise of the different attempts, the number of laryngoscopies per week usually performed, the hours on shift already worked before intubation. We recorded pre-oxygenation data focusing on type and tyming of the device used and the peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) at the end. Drugs and dosage, the device used, grading of Cormack-Lehane views, the lowest SpO2 during laryngoscopy were also recorded. End-tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO2) level was also recorded when available. We recorded the occurrence of difficult airways (more than 3 attempts of intubation), the need of front of neck airways, the onset of any arrhythmias, the detection of esophageal intubation. Within 30 minutes from the intubation, we recorded the occurrence of severe hypoxia, defined as a SpO2 <80%, hemodynamic instability defined as SBP 65 mmHg recoded at least once or SBP < 90 mmHg for 30 minutes, a new requirement or increase of vasopressors, fluid bolus >15 mL/kg to maintain the target blood pressure, and the occurrence of cardiac arrest. Within 6 hours from the intubation the onset of new pneumomediastinum and/or pneumothorax was collected.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was to determine the occurrence of at least 1 of the following events within 30 minutes from the start of the intubation procedure and to describe the types of major adverse peri-intubation events12: severe hypoxemia defined as an oxygen saturation as measured by pulse-oximetry (SpO2) <80%; hemodynamic instability defined as a SBP 65 mmHg recoded at least once or SBP < 90 mmHg for 30 minutes, a new requirement or increase of vasopressors, fluid bolus >15 mL/kg to maintain the target blood pressure; cardiac arrest. The secondary endpoint included the occurrence of cardiac arrhythmias, difficult intubation defined according to SIAARTI task force Recommendation, a cannot-intubate or cannot-oxygenate scenario (defined as impossibility to achieve a successful tracheal intubation and adequate patient’s oxygenation), emergency front-of neck airway, pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents, esophageal intubation, airway injury and the occurrence of pneumothorax or pneumomediastinum within 6 hours from the intubation.

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata software v. 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). The cumulative incidence of major adverse events during intubation is estimated to be 0.28.13 The primary endpoint of our study was to estimate the cumulative incidence of a major adverse event in patients with COVID-19, a figure currently not estimated in the literature. We assumed a larger cumulative incidence of the major adverse event in the COVID-19 patients who need intubation. We considered that the major adverse event can occur in 0.45 of COVID-19 patients who need intubation; the sample size of 80 achieves 80% power to reject the null hypothesis of zero effect size when the population effect size is 0.30 and the significance level (alpha) is 0.050 using a two-sided one-sample z test. Supplement online 1 shows the dropout-Inflated Sample Size and the estimated power for a one-sample proportion test. The primary and secondary endpoints were expressed as absolute frequency and percentage (number of each event on total intubations). Normal distribution was assessed by Shapiro-Wilk test. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median [interquartile range], as adequate. Categorical variables were shown as absolute and percentage frequencies. Two groups were identified: patients who had at least one adverse event at intubation and patients without adverse events. The descriptive comparison between the two groups was performed by Student's T test or Wilcoxon's Ranksum test for continuous variables and by the Chi-squared/Fisher’s exact test for categorical ones. A logistic regression model with stepwise forward modality was carried out to define the risk factors for the major adverse event. A multivariable logistic regression model was performed including as covariates variables with P values < 0.05 in the bivariable analyses or with a clinically relevant meaning. A post-estimation analysis was performed to evaluate the goodness of the model with the Hosmer-Lemeshow tests, Akaike's information criterion, Bayesian information criterion, accuracy, sensitivity and specificity of the model.

Results

Participants

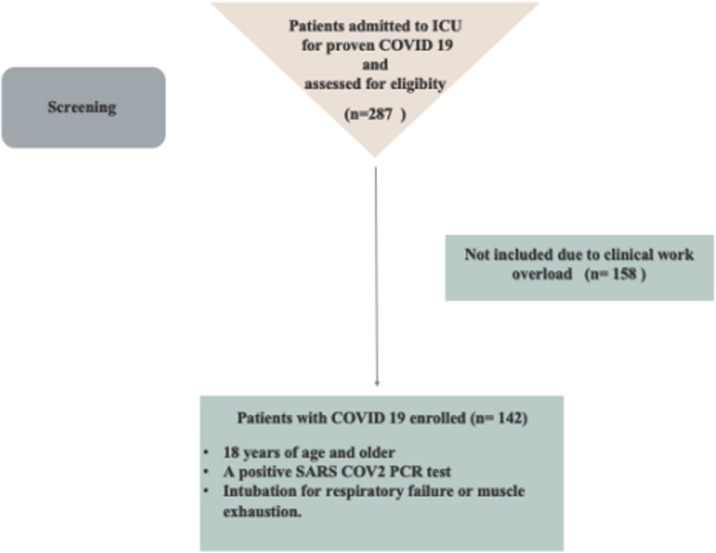

Between November 2020 and May 2021, we enrolled 142 COVID-19 patients needing endotracheal intubation. Fig. 1 shows the flow study population. The type of our data and the electronic health record let us to collect all data without missing. However, we exceed the estimated sample size, improving the power of the study. Demographic data are represented in Table 1 .

Figure 1.

Flow study population.

Table 1.

Demographic Data.

| Variable | No. (%) (n = 142) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 64 (57-71) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.35 (25.95-32.87) |

| Comorbidities | |

| No comorbidities | 13 (9.1) |

| Obesity | 57 (40.1) |

| Asthma | 7 (4.9) |

| COPD | 6 (4.2) |

| Interstitial lung disease | 2 (1.4) |

| OSAS | 4 (2.8) |

| Hypertension | 74 (52.1) |

| Diabetes type II | 38 (27.8) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 16 (11.3) |

| Chronic heart failure | 1 (0.7) |

| Arrhythmia | 2 (1.4) |

| Vascular disease | 11 (7.7) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 9 (6.3) |

| Chronic liver disease | 4 (2.8) |

| Autoimmune disease | 10 (7.0) |

| Previous malignancy | 12 (8.4) |

| Hematological disease | 1 (0.7) |

| Previous Department | |

| Emergency department | 25 (17.6) |

| Medical | 115 (81) |

| Surgical | 3 (2.1) |

| Recovery room | 1 (0.7) |

| Other ICU in the hospital | 1 (0.7) |

| Other hospital | 0 (0) |

| Radiological finding | |

| Lung opacities | 142 (100) |

| Bilateral | 136 (95.8) |

| Unilateral | 5 (3.5) |

| Pleural effusion | 3 (2.1) |

| Pneumothorax | 7 (4.9) |

| Pneumomediastinum | 4 (2.9) |

| Subcutaneous emphysema | 6 (4.2) |

| Pulmonary thrombo-embolism | 2 (1.4) |

Abbreviation: COPD, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; SpO2: peripheral oxygen saturation; ICU: intensive care unit; BMI: body mass index; OSAS: obstructive sleep apnea syndrome; ICU: intensive care unit.

Continuous variables are expressed as median [IQR], qualitative data as number (%).

Setting and monitoring of intubation

Airways Assessment and Indication of Intubation are shown in Table 2 . Particularly, thyroimental distance was calculated as a straight line from mentum to thyroid notch with mouth closed and neck fully extended.

Table 2.

Airways assessment and peri-intubation.

| Variable | No. (%) (n = 142) |

|---|---|

| Anticipated difficult intubation | 55 (38.7) |

| Thyromental distance | 18 (12.7) |

| Mouth opening | 5 (3.5) |

| Inability to prognathy | 1 (0.7) |

| Neck Stiffness | 7 (4.9) |

| Cardiorespiratory parameters pre-intubation | |

| SpO2 (%) | 93 (89-95) |

| Heart rate, (bpm/min) | 87 (75-100) |

| Systolic blood pressure, (mm Hg) | 133 (116-148,5) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, (mmHg) | 70 (60-80) |

| Location of intubation | |

| ICU | 137 (96.5) |

| Emergency Department | 2 (1.4) |

| Other | 3 (2.1) |

| Peri-intubation | |

| Receiving vasopressor or inotropic support | 11 (7.7) |

| Fluid bolus 30 minutes before intubation | 27 (19.0) |

Abbreviation: SpO2: peripheral oxygen saturation; ICU: intensive care unit.

Continuous variables are expressed as median [IQR], qualitative data as number (%).

Table 3 presents intubation characteristics and performance. Midazolam was the most frequently used induction agent (110 patients (77.46%), 48 (43.63%) times in co-administration with propofol and 50 (45.45%) times in co-administration with ketamine. Rocuronium was the unique neuromuscular blocking administered with a median dose 1.11 mg/kg (0.94-1.25). The average doses for midazolam, propofol e ketamine were 0.06 (0.04-0.08) mg/kg, 1 (0.6 – 1.41) mg/kg and 1.11 (0.94 -1.33) mg/kg, respectively. Fentanyl was the only opioid used. All drugs were administered on actual body weight. Characteristics concerning methods used to confirm intubation and attemps are reported in Table 3. Particularly, waveform capnografy was used in the 21.1 %, while monitor capnometry was ised in 27.5 of patients. Colorimetric carbon dioxide detection was never used. Macintosh Laryngoscope was used as the primary device for tracheal intubation for 21(14.89%) patients and a video laryngoscope (GlideScope®). in 121(85.21%) patients. No patients experienced impossibility to achieve a successful tracheal intubation and adequate patient’s oxygenation. First-pass intubation success was achieved for 129 (90.84%) patients.

Table 3.

Intubation Characteristics and Performance.

| Variable | No. (%) (n = 142) |

|---|---|

| Preoxygenation method | |

| Bag-valve mask | 74 (52.1) |

| Noninvasive ventilation | 51 (35.9) |

| Continuous positive airway pressure | 17 (12) |

| Apneic oxygenation | 0 (0) |

| Rapid sequence induction | 127 (89.4) |

| Cricoid pressure | 3 (2.1) |

| Induction agent | |

| Propofol | 77 (54.2) |

| Midazolam | 110 (77.5) |

| Ketamine | 56 (39.4) |

| Muscle relaxant | |

| Rocuronium | 141 (99.3) |

| Succinylcholine | 0 (0) |

| Vecuronium | 0 (0) |

| Cisatracurium | 0 (0) |

| Opioid use for intubation:fentanyl | 100 (70.4) |

| Laryngoscopy | |

| Direct laryngoscopy | 21 (14.9) |

| Video laryngoscopy | 121(85.2) |

| Other methods | 0 (0) |

| First method used to confirm intubation | |

| Auscultation | 12 (8.4) |

| Waveform capnography | 30 (21.1) |

| Colorimetric carbon dioxide detection | 0 (0) |

| Monitor capnometry | 39 (27.5) |

| Rx | 14 (9.9) |

| Fiberscope | 3 (2.1) |

| Video-laryngoscope | 99 (69.7) |

| Thoracic excursion | 112 (78.9) |

| Ventilator wave | 2 (1.4) |

| Lung ultrasound | 4 (2.8) |

| Success | 142 (100) |

| First pass | 129 (90.8) |

| Second pass | 13 (9.1) |

| Emergency front-of-neck access | 0 (0) |

| Cannot-intubate | 0(0) |

| Cannot-oxygenate | 0(0) |

Continuous variables are expressed as median [IQR], qualitative data as number (%).

Adverse events

Adverse events are shown in Table 4 . Particulalry, among the 142 enrolled patients, 105 (73.94%) experienced at least 1 major adverse peri-intubation event,and 35 (24.65%) more than one adverse events simultaneously.

Table 4.

Adverse events within 30 minutes and 6 hours.

| Variable | No. (%) (n = 142) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Within 30 minutes | Within 6 hours | |

| Severe Hypoxemia | 64 (43.5) | - |

| Cardiovascular | ||

| Hemodynamic instability | 93 (65.5) | - |

| Supra-ventricular ventricular | 13 (9.1) | - |

| Ventricular arrhythmia | 2 (1.4) | - |

| CA with ROSC | 2 (1.4) | - |

| CA without ROSC | 2 (1.4) | - |

| Mechanic | ||

| Gastric aspiration | 0 (0) | |

| Esophageal intubation | 1 (0.7) | |

| Airways lesions | 1 (0.7) | |

| Death | 2 (1.4) | - |

| Pneumothorax/Pneumomediastinum | - | 16 (11.3) |

Abbreviation: CA: cardiac arrest; ROSC: return of spontaneous circulation.

Continuous variables are expressed as median [IQR], qualitative data as number (%).

Cardiovascular instability accounted for most of the events, followed by severe hypoxemia. Four patients (2.82 %) had a cardiac arrest following tracheal intubation. Particularly, among the secondary outcomes, 13 (9.15%) patients had new onset of supraventricular arrhythmia and at six hours from intubation, 16 (11.26%) patients developed pneumothorax/pneumomediastinum.

All pneumothorax/pneumomediastinum were successfully managed with chest tube drainage.

The rate of major adverse events was significantly lower with first-pass intubation success than it was for patients requiring 2 attempts (67.61% vs 84.62%; p < 0.001).

Multivariable analysis is shown in Table 5 . The model correctly classified the occurrence of a major adverse events with a accuracy of 82%. Overall, 97 (31.7%) of patients discharged from ICU survived, while 67 (47.18%) died in hospital. No difference was found for ICU length of stay between patients with a major adverse peri-intubation event and patients without events: 21 (14.5-32) days vs 20 (14-32) days; (p = 0.44).

Table 5.

Multivariable Logistic Regression Analysis of Factors Associated with the occurrence of major adverse events.

| Adverse Event | Odds Ratio | P value | [95% Conf. Interval] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 1.25 | 0.70 | 0.40 - 3.87 |

| Age | 1.02 | 0.51 | 0.97 - 1.07 |

| DBP | 0.95 | 0.007 | 0.91 - 0.98 |

| HR | 1.04 | 0.006 | 1.02 - 1.07 |

| Lowest SpO2 | 0.89 | 0.001 | 0.83 - 0.95 |

Abbreviation: DBP: diastolic blood pressure, HR: heart rate, SpO2: peripheral oxygen saturation.

Observation n = 142; goodness of fit p = 0.98.; area under the receiver operating characteristic curve = 0.86 (CI: 0.83 – 0.89); Se = 94.34%, Sp = 35.71%. Akaike score 105.35.

Continuous variables are expressed as median [IQR], qualitative data as number (%).

Discussion

The present prospective study is the first to provide data on orotracheal intubation practices in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic protocols. In this study, we observed that orotracheal intubation practices in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic protocols was associated with major adverse peri-intubation Particularly, the most frequent and important event is represented by hemodynamic instability that occurred in 65.5% of all patients, followed by severe hypoxemia 43.5% and cardiac arrest 2.8 %.

Based on the available literature, the incidence of post-intubation hemodynamic instability following ETT is between 5 to 440 cases per 1,000 intubations, with a pooled estimate of 110 cases per 1,000 intubations (95% CI 65–167).14 Russotto et al. reported that severe hemodynamic instability occurred in 42.6 % of all patients.12 Although in literature no standard definition of blood pressure threshold for post-intubation hemodynamic instability exists, we defined hemodynamic instability according to Russotto et al.12 In a recent retrospective study of 202 COVID-19 patients undergoing ETT, Yao W. et al. reported that hypotension (SBP <90 mmHg and a DBP < 60mmhg), occurred in 36 (17.8%) patients during intubation and in 45 (22.3%) patients after intubation.5 COVID-19 patients are characterized by a cardiovascular syndrome including acute myocardial injury, arrhythmias, and cardiomyopathy.15 Unfortunately, evidence for interventions aiming to achieve cardiovascular stability before tracheal intubation is currently limited. Janz DR et al. showed that administration of an intravenous fluid bolus did not decrease the overall incidence of cardiovascular collapse during tracheal intubation of critically ill adults compared with no fluid bolus.16

Hypoxemia, defined SpO2 <80%, was the second frequent complication that occurred in 43.54% of all patients.Hypoxemia is a common complication during tracheal intubation of critically ill adults,17 as suggested by 2017 guidelines a comprehensive strategy to optimize oxygenation could be performed18 and a severe hypoxemia during tracheal intubation could be accurately predicted.19

COVID 19 is characterized by the phenomenon of “silent hypoxemia”.19 In our study, we defined severe hypoxemia based on SpO2 <80%, considering the current target oxygen saturation range for patients with COVID-19 recommended 92% and 96%.20 Yao W. et al. defined SpO2 <90% as the target to define hypoxemia after the intubation.5 Although NIV systems and HFNC may promote microorganism aerosolisation,21 preoxygenation should be performed keeping attention to individual protection and minimizing the risk of contamination.22 Unfortunately, at this moment, it is not known which of the devices allows to perform a more adequate pre-oxygenation in COVID- 19 patients.

In our COVID-19 patients, 4 (2.82%) patients, two of which with a shockable rhythm, experienced cardiac arrest following oro-tracheal intubation, compared to 2% reported in literature5 and 2-3% reported in critically ill patients.9, 23 Considering both hypotension and hypoxemia before intubation as predictors of cardiac arrest,9 it is not suggested to prolong nonresponsive NIV or HFNO.24

Minor adverse events were found to be in a minimal percentage compared to major events. Particularly, although arrhythmias are one of the major complications in COVID 19 patients,25 the occurrence of atrial fibrillation during orotracheal intubation was lower (9.15%) compared to critically ill patients.13 Pneumothorax/pneumomediastinum was slightly higher and occurred in 16 patients (11.26%) and are frequent complications despite the employment of a protective NIV strategy.26

Endotracheal intubation is a high-risk, lifesaving advanced airway skill, nad complicated by personal protective equipment worn. Training and maintaining post training competency were also a challenging during the pandemic. However, in a recent study,were observed adherence to society guidelines regarding performance of tracheal intubation by an expert laryngoscopist and the use of videolaryngoscopy.27 The choice of induction and paralyzing agents during rapid sequence intubation is based on situational needs, experience,28, 29 but also patient’s characteristics.21 Yao W. et al. in their study reported a prophylactic administration of a vasopressor to mitigate the hypotensive effect of propofol (and/or other co-induction agents).5, 30 Although guidelines recommended to use always videolaryngoscopy as the method of choice to perform endotracheal intubation in COVID-19,31 it was used in 85.21% of patients, in the remaining percentage a direct laryngoscopy was performed.

Our study presents some limitations. First, we analyzed a small cohort from a two single city, and a larger sample size from more different hospitals would be ideal for this type of study. While 65.5% of patients had hemodynamic instability, it is difficult to assess the significance of results with the lack of a control group. In addition, no data were reported on duration of hemodynamic instability, acute cardiovascular dysfunction and patterns of myocardial injury. Second, only patients who finally needed an intubation were included and followed. This study only included patients who underwent invasive mechanical ventilation, and it does not provide insights into those who responded well on non-invasive mechanical ventilation and never required intubation. In addition, during the second wave, a proportion of patients underwent delayed intubation strategy. Third, the enrolment phase was compromised by massive amount workload, probably due to the number of night shift. Fourth, we did not assess the success rate based on experience of each health care provide and the association with major complications.

Fifth, practice variation with respect drug dosing and administration may serve as a study confounder. To conclude, this study did not collect information on direct long-term consequences of adverse peri-intubation events.

Conclusions

In this prospective, observational, dual-center study of intubation practices in critically ill patients with COVID-19, major adverse peri-intubation events, such as cardiovascular instability, were frequently observed.

Authors' contributions

All authors have contributed to this manuscript and approved this version for submission. LC and SDR designed the study. EP, FD, GB and LC contributed in recruitment of patients and data collection. FF processed analysis of results. FF, LC and SDR wrote the first draft of the manuscript. FM, KD, SM, EP and VD helped to revise the manuscript. All coauthors participated in subsequent revisions of the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

The publication of paper is supported by institutional funding.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study will be carried out according to the Declaration of Helsinki, the NHMRC National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Research Involving Humans. The study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of all participating hospitals. The informed consents will be obtained from the eligible participants before participation in the study.

Consent for publication

The authors declare that they consent for publication.

Competing interests

FM received fees for lectures from GE Healthcare, Hamilton Medical, SEDA SpA, outside the present work. SM received fees for lectures from GE Healthcare, outside the present work. A research agreement is active between University of Pavia and Hamilton Medical. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgement

We thank all investigators, doctors and nurses of the participating Intensive Care Unit for their invaluable collaboration.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medin.2022.07.002.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Rezoagli E., Magliocca A., Bellani G., Pesenti A., Grasselli G. Development of a Critical Care Response - Experiences from Italy During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic. Anesthesiol Clin. 2021;39(2):265–284. doi: 10.1016/j.anclin.2021.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calabrese F., Pezzuto F., Fortarezza F., Boscolo A., Lunardi F., Giraudo C., et al. Machine learning-based analysis of alveolar and vascular injury in SARS-CoV-2 acute respiratory failure. J Pathol. 2021;254(2):173–184. doi: 10.1002/path.5653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gattinoni L., Coppola S., Cressoni M., Busana M., Rossi S., Chiumello D. COVID-19 Does Not Lead to a "Typical" Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(10):1299–1300. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0817LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Y., Wang Y., Chen Y., Qin Q. Unique epidemiological and clinical features of the emerging 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) implicate special control measures. J Med Virol. 2020;92(6):568–576. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yao W., Wang T., Jiang B., Gao F., Wang L, et al. collaborators. Emergency tracheal intubation in 202 patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: lessons learnt and international expert recommendations. Br J Anaesth. 2020;125(1):e28–e37. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang L., Li J., Zhou M., Chen Z. Summary of 20 tracheal intubation by anesthesiologists for patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia: retrospective case series. J Anesth. 2020;34(4):599–606. doi: 10.1007/s00540-020-02778-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leone M., Einav S., Chiumello D., Constantin J.M., De Robertis E. De Abreu MG, et Al; Guideline contributors. Noninvasive respiratory support in the hypoxaemic peri-operative/periprocedural patient: a joint ESA/ESICM guideline. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(4):697–713. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05948-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sorbello M., El-Boghdadly K., Di Giacinto I., Cataldo R., Esposito C., Falcetta S, et al. Società Italiana di Anestesia Analgesia Rianimazione e Terapia Intensiva (SIAARTI) Airway Research Group, and The European Airway Management Society. The Italian coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak: recommendations from clinical practice. Anaesthesia. 2020;75(6):724–732. doi: 10.1111/anae.15049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Jong A., Rolle A., Molinari N., Paugam-Burtz C., Constantin J.M., Lefrant J.Y., et al. Cardiac arrest and mortality related to intubation procedure in critically ill adult patients: a multicenter cohort study. Critical Care Med. 2018;46:532–539. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vandenbroucke J.P., von Elm E., Altman D.G., Gøtzsche P.C., Mulrow C.D., Pocock S.J., et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):W163–94. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010-w1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petrini F., Accorsi A., Adrario E., Agrò F., Amicucci G., Antonelli M., et al. Gruppo di Studio SIAARTI "Vie Aeree Difficili"; IRC e SARNePI; Task Force. Recommendations for airway control and difficult airway management. Minerva Anestesiol. 2005;71(11):617–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Russotto V., Myatra S.N., Laffey J.G., Tassistro E., Antolini L., Bauer P, et al. INTUBE Study Investigators. Intubation Practices and Adverse Peri-intubation Events in Critically Ill Patients From 29 Countries. JAMA. 2021;325(12):1164–1172. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jaber S., Amraoui J., Lefrant J.Y., Arich C., Cohendy R., Landreau L., et al. Clinical practice and risk factors for immediate complications of endotracheal intubation in the intensive care unit: a prospective, multiple-center study. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(9):2355–2361. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000233879.58720.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green R., Hutton B., Lorette J., Bleskie D., McIntyre L., Fergusson D. Incidence of postintubation hemodynamic instability associated with emergent intubations performed outside the operating room: a systematic review. CJEM. 2014;16(1):69–79. doi: 10.2310/8000.2013.131004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hendren N.S., Drazner M.H., Bozkurt B., Cooper LT Description and Proposed Management of the Acute COVID-19 Cardiovascular Syndrome. Circulation. 2020;141(23):1903–1914. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janz D.R., Casey J.D., Semler M.W., Russell D.W., Dargin J., Vonderhaar DJ, et al. PrePARE Investigators; Pragmatic Critical Care Research Group. Effect of a fluid bolus on cardiovascular collapse among critically ill adults undergoing tracheal intubation (PrePARE): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7(12):1039–1047. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30246-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKown A.C., Casey J.D., Russell D.W., Joffe A.M., Janz D.R., Rice T.W., et al. Risk Factors for and Prediction of Hypoxemia during Tracheal Intubation of Critically Ill Adults. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15(11):1320–1327. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201802-118OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgs A., McGrath B.A., Goddard C., Rangasami J., Suntharalingam G., Gale R, et al. Difficult Airway Society; Intensive Care Society; Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine; Royal College of Anaesthetists. Guidelines for the management of tracheal intubation in critically ill adults. Br J Anaesth. 2018;120(2):323–352. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2017.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKown A.C., Casey J.D., Russell D.W., Joffe A.M., Janz D.R., Rice T.W., et al. Risk Factors for and Prediction of Hypoxemia during Tracheal Intubation of Critically Ill Adults. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15(11):1320–1327. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201802-118OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shenoy N., Luchtel R., Gulani P. Considerations for target oxygen saturation in COVID-19 patients: are we under-shooting? BMC Med. 2020;18(1):260. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01735-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tran K., Cimon K., Severn M., Pessoa-Silva C.L., Conly J. Aerosol generating procedures and risk of transmission of acute respiratory infections to healthcare workers: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2012;7(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meng L., Qiu H., Wan L., Ai Y., Xue Z., Guo Q., et al. Intubation and Ventilation amid the COVID-19 Outbreak: Wuhan’s Experience. Anesthesiology. 2020;132(6):1317–1332. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nolan JP, Kelly FE. Airway challenges in critical care. Anaesthesia. 2011;66(Suppl 2):81–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2011.06937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boscolo A., Pasin L., Sella N., Pretto C., Tocco M., Tamburini E, et al. FERS, for the COVID-19 VENETO ICU Network. Outcomes of COVID-19 patients intubated after failure of non-invasive ventilation: a multicenter observational study. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):17730. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-96762-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., Zhu F., Liu X., Zhang J., et al. Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lemmers D.H.L., Abu Hilal M., Bnà C., Prezioso C., Cavallo E., Nencini N., et al. Pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema in COVID-19: barotrauma or lung frailty? ERJ Open Res. 2020;6(4):00385–02020. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00385-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hawkins A., Stapleton S., Rodriguez G., Gonzalez R.M., Baker W.E. Emergency Tracheal Intubation in Patients with COVID-19: A Single-center, Retrospective Cohort Study. West J Emerg Med. 2021;22(3):678–686. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2020.2.49665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Law J.A., Broemling N., Cooper R.M., Drolet P., Duggan L.V., Griesdale DE, et al. Canadian Airway Focus Group. The difficult airway with recommendations for management--part 1--difficult tracheal intubation encountered in an unconscious/induced patient. Can J Anaesth. 2013;60(11):1089–1118. doi: 10.1007/s12630-013-0019-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mosier J.M., Sakles J.C., Law J.A., Brown CA, 3rd, Brindley P.G. Tracheal Intubation in the Critically Ill. Where We Came from and Where We Should Go. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(7):775–788. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201908-1636CI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ho AM, Mizubuti GB. Co-induction with a vasopressor "chaser" to mitigate propofol-induced hypotension when intubating critically ill/frail patients-A questionable practice. J Crit Care. 2019;54:256–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2019.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cook T.M., El-Boghdadly K., McGuire B., McNarry A.F., Patel A., Higgs A. Consensus guidelines for managing the airway in patients with COVID-19: Guidelines from the Difficult Airway Society, the Association of Anaesthetists the Intensive Care Society, the Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine and the Royal College of Anaesthetists. Anaesthesia. 2020;75(6):785–799. doi: 10.1111/anae.15054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.