Abstract

The complexity of the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) presents higher requirements for intrusion detection systems (IDSs). An adversarial attack is a threat to the security of machine learning-based IDSs. For such a complex situation, this paper analyses adversarial attackers’ ability to deceive IDSs used in the IIoT and proposes the evaluation of an IDS with function-discarding adversarial attacks in the IIoT (EIFDAA), a framework that can evaluate the defence performance of machine learning-based IDSs against various adversarial attack algorithms. This framework is composed of two main processes: adversarial evaluation and adversarial training. Adversarial evaluation can diagnose IDS that is unfitting in adversarial environments. Then, adversarial training is used to treat the weak IDS. In this framework, five well-known adversarial attacks, the fast-gradient sign method (FGSM), basic iterative method (BIM), projected gradient descent (PGD), DeepFool and Wasserstein generative adversarial network with gradient penalty (WGAN-GP) are used to convert attack samples into adversarial samples to simulate the adversarial environment. This study evaluates the capability of mainstream machine learning techniques as intrusion detection models to defend against adversarial attacks, and retrains these detectors to improve the robustness of IDSs through adversarial training. In addition, the framework includes an adversarial attack model that discards the attack function of the attack samples in the IIoT. Through the experimental results on the X-IIoTID dataset, the dropped adversarial detection rate of these detectors to nearly zero demonstrates that an adversarial attack has black-box attack capabilities for these IDSs. Additionally, the improved IDSs retrained with adversarial samples can effectively defend against adversarial attackers while maintaining the original detection rate for the attack samples. EIFDAA is expected to be a solution that can be applied to IDS for improving the robustness in the IIoT.

Keywords: Adversarial attack, Intrusion detection system, Industrial internet of things, Machine learning

1. Introduction

The Internet of Things (IoT) is an important product of the third industrial revolution and has profoundly affected people's way of life. Predictably, the future will include the continuous development of the IoT. Industry has always been an essential cornerstone and guarantee for national development. Using the IoT to improve the level of industrial development and to provide a solid guarantee to improve the lives of citizens is the original intention of the Industrial IoT (IIoT). Construction of the IIoT has occurred in various countries [1]. However, preliminary research on the security of the IIoT shows that large areas of infrastructure are frequently affected by vulnerabilities that are difficult to patch due to the complexity of the network [2]. Under the temptation of extremely large profits, IoT devices have received increasing attention from hackers [3].

As a typical approach for network security guarantees, network intrusion detection technologies are widely used in the construction of IIoT security platforms. Network intrusion technology has shown excellent performance in identifying abnormal network traffic, locating sources of threats, resisting malicious access and other network security tasks, and has become an indispensable link in network security systems [4]. Network intrusion detection can monitor and analyse flows, behaviours and states of a protected network and then issue an alarm and take defensive measures if the network is attacked [5]. Machine learning (ML) is widely used in intrusion detection systems (IDSs). Advances in ML techniques have improved the accuracy and efficiency of IDS. However, adversarial attackers can transform attack samples into adversarial samples, which renders the ML-based IDS of the target network platform of adversarial attackers unable to perceive the abnormal state of the platform and creates conditions for nonadversarial attacks (such as denial of service, distributed denial of service, and injection attacks). Obviously, such detectors built with ML support cannot be applied in a real-world environment, or it would be a security risk. Hence, evaluation and defence measures are taken against adversarial attacks to ensure the security of IDSs based on machine learning [6].

Adversarial attackers continuously focus on IIoT platforms, and adversarial attacks conceal nonadversarial attacks so that an IDS cannot accurately identify the true state of the platform. However, the platform loss can appear to be caused by a nonadversarial attacker, and cybersecurity personnel typically attribute this loss to a failure of the IDS while ignoring the possibility of the adversarial attack. Therefore, it is particularly important to evaluate whether an IDS is resistant to adversarial attacks. To avoid the detection of nonadversarial attacks, adversarial attackers attack the supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) or the undetected database of the IDS and convert the attack records into normal records to cause the IDS in the protected IIoT platform to misclassify. In addition, whether the transformed normal samples (i.e., adversarial samples) retain functional features is frequently considered. According to Ref. [7], adversarial attacks should preserve attack features to preserve the attack ability of adversarial samples to the target platform. However, this paper argues that in the adversarial attack model, it is not necessary to use the strategy to maintain the combat capability of adversarial attacks.

Investigating the capability of IDSs to defend against adversarial attacks is important for building a secure IIoT. This paper selects a publicly released dataset, that is suitable for intrusion detection in the IIoT, to analyse the defence performance of intrusion detection methods against adversarial attacks through experiments and provides an evaluation scheme for IDSs in industry.

The major contributions of this paper are as follows:

-

1)

Using adversarial attack algorithms and intrusion detection methods, the evaluation of an IDS with function-discarding adversarial attacks in the IIoT (EIFDAA) framework, is proposed to evaluate an IDS's ability to resist black-box adversarial attacks in the IIoT and provide an indicator for the security evaluation of IDSs.

-

2)

In this paper, five adversarial sample generation algorithms and seven ML techniques are used to establish the EIFDAA framework, and the X-IIoTID [8] dataset is applied to simulate the historical state of the IIoT platform to analyse the evaluation effect on the IIoT.

-

3)

This paper proposes an adversarial attack model suitable for various complex systems. Adversarial attackers transform attack samples into adversarial samples to fool IDSs. Moreover, adversarial samples do not retain the functional characteristics and attack capabilities of the attack samples.

-

4)

The EIFDAA framework not only evaluates the robustness of the IDS against adversarial samples but also analyses the defence mechanism of adversarial training. When the framework finds that the detectability of the IDS is reduced due to the adversarial attack, the adversarial samples and original training dataset are fused into the adversarial training dataset, and the IDS is repeatedly trained to recover the attack detectability so that the IDS can defend against an adversarial attack in advance.

The rest of this paper is organised as follows: Section 2 reviews the related work on adversarial attacks and IDSs and presents the core problems and solutions of this paper. Section 3 describes the proposed adversarial attack model in detail and the objectives and components of the EIFDAA evaluation framework. In Section 4, the defence situation of various intrusion detection methods against adversarial attacks is evaluated, and the effect of adversarial training on improving the robustness of the IDSs is analyzed. Finally, Section 5 concludes this work and discusses future work directions.

2. Motivation and related work

The motivation for investigating the security of the IDS is inherited from the following works [9]. proposed a general attack and defence framework by using the football tactic TIKI-TAKA, which examined the defence ability of a deep learning-based IDS against the adversarial operation of network traffic. They integrate related techniques, including three neural network-based IDSs, five adversarial attack strategies, and three defence mechanisms. Their experimental results show that defence mechanisms (such as model voting, integrated adversarial training and query detection) can improve the robustness of an IDS against adversarial samples in multiple scenarios. Adversarial samples are generated through two steps [10]. The first step is to construct a saliency graph from the network packets to identify the critical features that affect the classification results. The second step utilises the iterative fast gradient symbol method (FGSM) approach to implement the desired perturbations over the critical features. The network IDS (NIDS), named Kitsune, has been successfully attacked by generating adversarial samples with the Mirai Botnet and VideoInjection dataset. Features have been grouped and then fused by multiple detection models to propose the feature grouping and multi-model fusion detector (FGMD) intrusion detection method for defence against adversarial attacks [11]. The results on the IoT datasets show that the proposed method has a higher detection rate (DR) for adversarial samples than the benchmark detection model. To confront the threat of adversarial attacks, the idea of explainable AI has been incorporated into intrusion detection models [12]. The local interpretable model-agnostic explanations (LIME) are used to extract the features of training datasets as the important feature set S. It is worth noting that an IDS can be evaded only if all features of the sample that are classified as normal by IDS belong to set S. The Jacobian-based saliency map attack (JSMA) and FGSM are token as an adversary to attack machine learning-based IDS [13]. In addition, various machine learning algorithms are trained on adversarial training to enhance the detection performance on three network intrusion detection datasets. Deep neural networks, such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs), have been evaluated for resilience performance as IDSs against adversarial attacks [14]. However, the aforementioned studies have not investigated IDS in the IIoT environment and proposed an overall framework for addressing the problem of misclassification of the IDS induced by an adversarial attack.

A framework named DIGFuPAS was proposed to generate adversarial samples that cause IDSs to misclassify in software-defined networks (SDNs), and it was used to improve the robustness of IDSs against adversarial samples through adversarial training [15]. The Wasserstein generative adversarial network (WGAN) was employed as a generation model for creating adversarial samples to attack a target IDS protecting SDN-enabled models. Various inputs that differ only slightly from the original samples are adopted by the WGAN to generate adversarial samples. The first input includes the nonfunctional characteristics of attack samples to reverse intrusion threats to target networks. Furthermore, a noise vector of dimension 9 and a nonfunctional number are adopted as input. The experimental results show that the 9 machine learning or deep learning based IDSs can barely detect the adversarial samples generated by WGAN from attack samples, but the retrained IDSs using a training set that includes adversarial samples can improve the detection success rate of adversarial samples. However, adopting a similar strategy as in Refs. [[9], [10], [11]], the DIGFuPAS architecture only modified the nonfunctional features of attack samples. This strategy reverses the features related to the nature of the network traffic or attack pattern to guarantee straightforward performance in creating samples in the target platform. However, there is a critical question: is it necessary for the adversarial sample to retain continuously attack function in the actual network environment? Can an adversarial attacker exploit information about the functional features of a sample? The answers to these questions may determine how adversarial samples are generated and their attack power.

Unfortunately, preserving functional features is not mentioned in studies of adversarial attacks [[16], [17], [18], [19]]. Adversarial attack algorithms were originally applied in the field of image recognition to generate an adversarial image that interferes with the recognition process of a classification model but appears trivial to humans [20]. Goodfellow et al. [16] suggested updating the pixel value once with the sign direction of the gradient of the loss function to a fool classifier. This approach was named the FGSM. The basic iterative method (BIM) was proposed after FGSM, and it prevents substantial changes from the original sample with clipped multiple iterations of FGSM [17]. The projected gradient descent attack (PGD), which was improved from BIM using the initialisation of uniform random noise, was recognised [18]. Adversarial samples created by the DeepFool attack borrow the concept of generalisability to fool a particular model as well as other models [19]. These attack methods are also used in industrial control systems or IoT environments [21,22]. Nevertheless, some of the character features are discrete after conversion to numerical values, but lose their practical importance. These generative algorithms are designed without any consideration of preserving the functional features of the samples. Since no study, to the best of our knowledge, has responded to this issue in the IIoT, this study analyses the particularity of an IDS deployed in IIoT platforms to fill this gap.

In the answer of this paper, to confront complex network environments such as IIoT environments, it is not necessary to adopt adversarial samples again on the target network platform. The functional features are optional when adversarial samples are generated by adversarial attackers. There are many types of vulnerable industrial devices that exist at every node of a network, which lead hackers to achieve a diversity of targets. Hence, the detected samples should reflect all the information of the target platform, including the infrastructure, network cloud, and operator, etc. Every part of the network platform has the potential to be hacked. However, the NIDS deployed on network nodes determines whether to allow the traffic to be forwarded to the next node by detecting the security of the traffic to defend against external network attacks [23]. The host-based IDS only analyses the security state of a machine. In both cases, IDS cannot provide security protection for the entire network platform. In contrast to a single IDS, an IDS deployed in the IIoT needs to monitor the security status of the entire platform by integrating network-based and host-based IDSs. It also means that the detected samples should consist of network traffic, host resources, logs, and alerts, etc [8]. This leads to attack or adversarial samples not arising after detection in real world environments. Therefore, discarding the attack function through modifying the functional features of the attack sample cannot affect its attack effect on the target platform. Adversarial attacks applying this evolution pose many challenges in sensing anomalous states in IIoT environments using IDSs. This paper proposes an adversarial attack model suitable for such revolutionary adversarial attack methods.

According to the above analysis, the exiting IDSs can diagnose general network attacks to a high level but are still unknown to this new adversarial attack model. The particularity of the IIoT platform requires a secure design of IDS to cope with the adversarial attack environment. How to realize and improve the security of currently deployed IDS in IIoT should be taken into consideration. Hence, this paper proposes an EIFDAA framework applied in an IIoT platform for evaluating the capability of an IDS against adversarial attacks. Different from DIGFuPAS in Ref. [15], EIFDAA is designed for the IIoT platform and provides a regular process for evaluating and enhancing the IDS.

3. Architecture design

Industries that have a decisive influence on people's lives and economies are important to the country. Network security is a fundamental guarantee for the normal operation of an IIoT platform. In network security technologies, an IDS is a critical module that senses anomalies and takes certain defensive measures. If the IDS is attacked and fails to work properly, the industrial network and its underlying devices are compromised and exposed to cyber hackers and criminals. This makes it clear that due to the complexity of IIoT and the existence of adversarial attacks, there is a need to evaluate and heighten the security of IDS.

Thus, the definition and description of an adversarial attack model that threatens IDSs are presented in this section, and detailed manifestations of the attack characteristics and methods of adversarial attackers are discussed. To evaluate the security performance of IDSs, a security architecture, named EIFDAA, is introduced to benchmark the performance of IDSs against adversarial attacks in IIoT platforms and use adversarial training to improve the strength of IDSs against various types of malicious records and adversarial examples.

3.1. Attack model

This paper proposes an adversarial attack model in which the attacker aims to conceal a nonadversarial attack from an IDS and disable the IDS from alerting and defending itself after the attack behaviour. This attack model represents the intrusion pattern of adversarial attackers threatening IDSs.

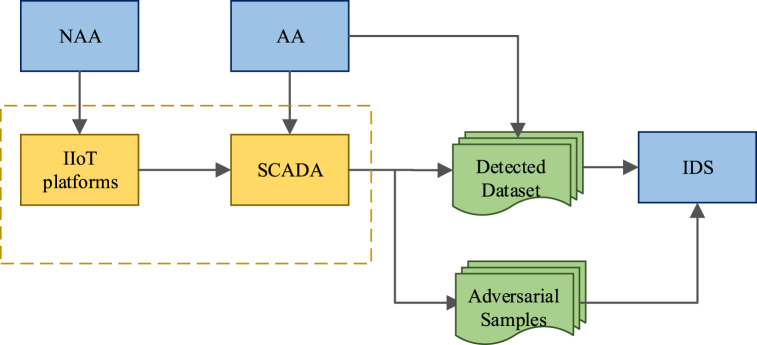

The question of whether the functional characteristics of adversarial samples can be preserved has attracted much attention from the academic community. The functional characteristics of adversarial samples (such as the IP address, port number, and protocol type) must comply with domain-specific constraints, otherwise they lose practical ability after adding perturbations [9]. This means that only a portion of a feature set can be modified and the function of the adversarial samples is inherited from the original samples. In fact, detected samples must possess functional characteristics in real-time NIDSs and will continue to circulate on the network after detection [24]. However, due to the large scale of data, wide range of sources, complex data types and other reasons, some complex systems (such as IoT and IIoT systems) have trouble achieving real-time detection. In the ecosystem applied in industrial applications described in Ref. [25], there are various types of underlying devices supporting different communication protocols in edge IT. Large amounts of data generated in industrial processes are preprocessed and handed over to the data centre or the cloud for analysis and management. Therefore, the detected data (e.g., network traffic, host resources, logs, and alerts) are collected as merely a memory of the system state and no longer have an impact on the platform. The target of an adversarial attacker becomes the SCADA or the database management system. Therefore, the adversarial attacker unnecessarily holds the attack payload to ensure the effectiveness of the attack on the target platform. Fig. 1 shows the attack pattern of an adversarial attacker.

Fig. 1.

Adversarial attack model.

The adversarial attack model proposed in this paper has three main components. The first component is the IDS, which protects the target IIoT platform from intrusion. The second component, which generates attack samples, is named the nonadversarial attacker (NAA). It directly attacks the IIoT platform to simulate hackers who are interested in the underlying infrastructure. The third component is the adversarial attacker (AA), which attacks the SCADA or the database management system with the goal of causing the IDS to misclassify and fail to successfully detect the NAA attacks. Under normal circumstances, the SCADA periodically gains status data of the IIoT platform and then sends it to the detected database for storage after simple preprocessing. The IDS takes the database to be detected as input to sense whether the platform is in a secure state. When the IIoT platform is invaded by an NAA, the SCADA still integrates the information reflecting the current state of the platform into the database. A successfully trained IDS can recognize abnormal states of the platform and issue alerts. However, the system complexity of the IIoT platform and SCADA makes it so that this process cannot be realised in real time. This creates a vulnerability, which makes the illegal invasion of an AA possible, and shows the particularity of the IIoT environment. Adversarial attackers directly attack the SCADA or database instead of the platform and transform the detected samples into adversarial samples to make the IDS misclassify and fail to correctly judge the real situation of the platform. The existence of this vulnerability also leads to serious consequences. Even if the adversarial attacker does not retain the attack characteristics of the adversarial sample, the target platform does not detect the occurrence of an adversarial attack. Therefore, the revolutionary adversarial attack method has a greater potential threat to the security of IDS. This adversarial attack model provides a new direction for the design and security evaluation of IDSs.

3.2. EIFDAA architecture

Adversarial attackers and IDSs are similar to adversaries in a game, where both must compete to accomplish their specific tasks. This section analyses their adversarial process and proposes a security evaluation framework for IDSs against adversarial attacks in an IIoT platform. The design idea of EIFDAA originates from the adversarial attack security problem of IDSs. More specifically, the threat of adversarial attacks to machine learning poses a security crisis for machine learning adoption in IDSs that protect IIoT platforms. EIFDAA investigates the performance of intrusion detection methods against adversarial attack algorithms and then uses adversarial training to improve the success rate of intrusion detection methods against adversarial samples. In addition, this framework does not preserve the functional characteristics of attack samples according to the particularity of the IIoT.

3.2.1. Overview of the EIFDAA architecture

By simulating adversarial attacks, EIFDAA converts attack samples into adversarial samples to conceal nonadversarial attacks. Then, EIFDAA investigates whether the IDS implemented by machine learning can detect adversarial samples. Finally, the IDS is retrained to enable the discovery of adversarial samples through adversarial training, and the detection success rate of the attack samples is maintained. EIFDAA provides an evaluation program for the adversarial attack security of the IDS in the IIoT, and the whole process is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The whole process of the EIFDAA.

This architecture has two important components: adversarial evaluation and adversarial training. Estimating the safety of IDS has become a fascinating study [15]. Defending adversarial attacks is the considered security measure within the evaluating process to diagnose IDS in the IIoT. Adversarial evaluation can discover the weak IDS that has robust infeasibility on adversarial samples. Additionally, adversarial training takes an active defence strategy to update the weak IDS. Original samples and adversarial samples to retrain the original IDS are fused in a balanced manner. It should be noted that EIFDAA covers major machine learning-based IDSs and adversarial attack algorithms. In other words, this framework can be applied in black-box IDSs in unexploitable IIoT environments. In addition, the detected datasets represent the historical state data of the target IIoT platform with the assumption that the architecture is deployed on the real SCADA of the platform. More details about the data source are discussed in Section 3.1.

3.2.2. Intrusion detection system

The IDS of the IIoT platform is the subjective aspect of EIFDAA framework evaluation and optimization, which not only undertakes the responsibility of ensuring the security of the target platform but is also one of the targets of the attackers. The ability of machine learning to improve the power of IDSs has been investigated in several studies [26]. Understanding the principle and security status of machine learning is the basic premise for ensuring the security of IDSs. Training a classification model on a dataset to detect nonadversarial attacks without considering the impact of adversarial attacks on the robustness of the model can leave potential security risks for future applications in real IDSs [27]. One of the goals in this framework is to provide a security indicator reference for evaluating the security of IDSs by investigating the defence power of machine learning models against adversarial attacks.

3.2.3. Adversarial attack

Adversarial attacks, also known as adversarial machine learning, cause classifiers to fail to recognize real samples by transforming real samples into fake samples [28]. Adversarial attacks have been extensively studied in the fields of image recognition [29], speech recognition and transformation [30], three-dimensional physical world processing [31] and text processing [32]. In the field of network security, the goal of adversarial attackers is to threaten the security of IDSs to enable NAAs to attack target networks. The adversarial attacker will cooperate with the nonadversarial attacker to convert the attack samples into adversarial samples simulating normal samples to bypass the IDS. Then, the attack samples can enter the target networks without being realised to achieve the goal to attack. Whether a network platform and its IDS can resist adversarial attacks is a core indicator for system security evaluation. Mastering and analysing advanced adversarial attack techniques in time is a crucial module of the EIFDAA framework.

3.2.4. Adversarial evaluation

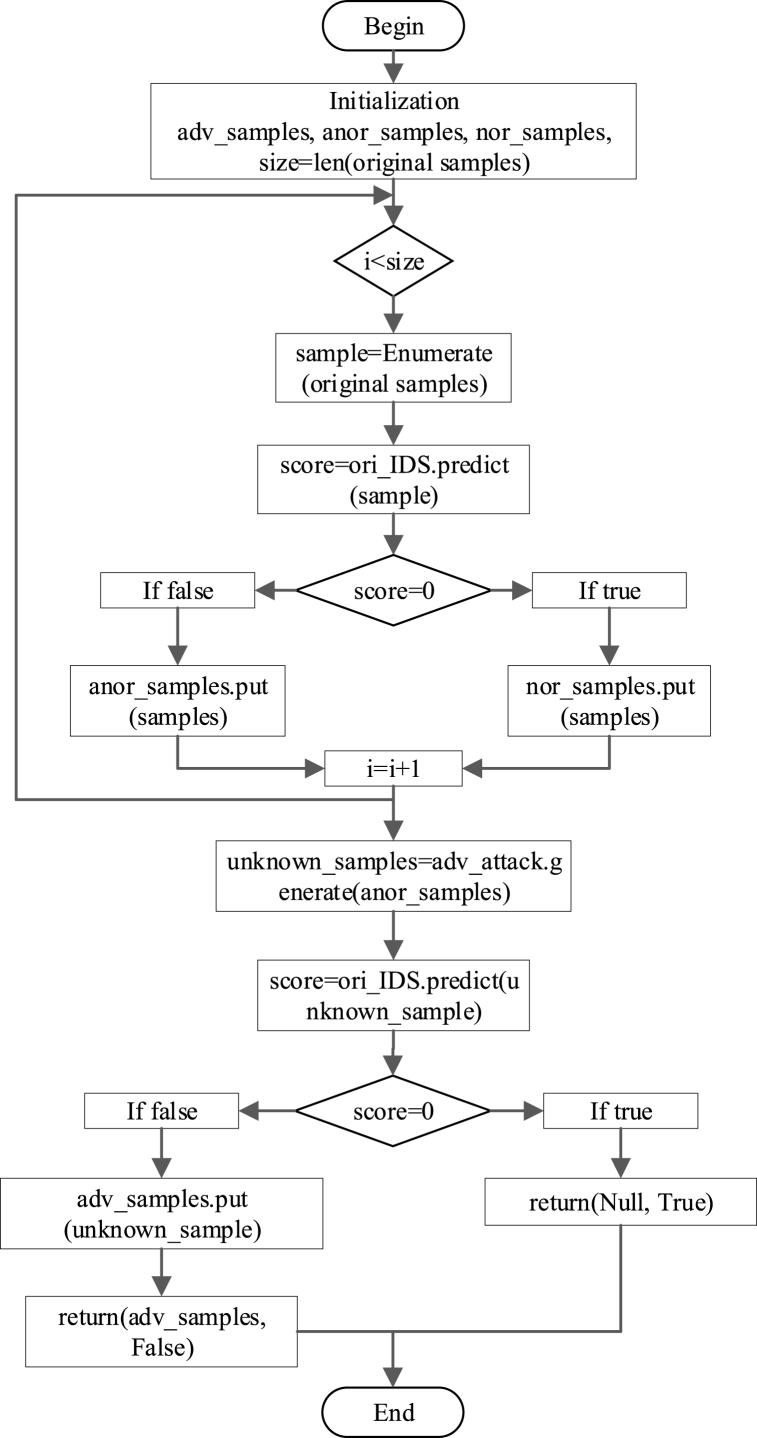

Adversarial evaluation plays a crucial role in identifying a threatened IDS and guiding the study of hunting adversarial samples. It is a general and easy way to detect the sensitivity of the black-box IDS to adversarial samples. This process can be implemented by any security administrator with data access. The flow chart of the adversarial evaluation is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

The adversarial evaluation of the EIFDAA.

The procedure and terms in Fig. 3 are explained in detail below. The original dataset is tested using the IDS in EIFDAA to split the samples into normal and abnormal samples. The abnormal samples represent the aggressive behaviour of a nonadversarial attacker. However, the normal samples represent two possible situations: one is that the platform is indeed secure, and the other is that the platform has been attacked by an adversarial attacker due to the IDS's failure to identify adversarial samples disguised as normal samples. To confront this complex situation, the adversarial attack module in EIFDAA generates adversarial samples by using abnormal samples to judge the IDS's ability to detect adversarial samples. If the detection is abnormal, the IDS can resist adversarial attacks. Otherwise, the normal samples may be insecure or even the target IIoT platform may be subjected to nonadversarial attacks under the cover of adversarial attacks. Finally, adversarial samples and the status of the IDS are returned. See algorithm 1 for the adversarial evaluation.

| Algorithm 1 Adversarial evaluation. |

|---|

| Input: |

| ori_IDS: The pretrained IDS, AEG: The adversarial example generator, OD: The original datasets |

| Output: |

| adv_samples, whether IDS is robust adv_samples = null; nor_samples = null; anor_samples = null; for x in OD: score = ori_IDS.predict(x); if score = = 1: anor_samples.put(x); else: nor_samples.put(x); end if end for unknown_samples = AEG.genarate(anor_samples); score = ori_IDS.predict(unknown_samples); if score = = 1: alert;//ori_IDS misclassification adv_samples.put(unknown_samples); return adv_samples, False; else: return null, True; end if |

3.2.5. Adversarial training

To overcome adversarial attacks, adversarial training, which utilises adversarial samples generated by the generation algorithms to retrain the classification model, is a simple and effective method to improve the robustness of the classification model [33]. The strategy of adversarial training is to fuse adversarial samples with attack labels into the original training set so that the classifier can learn the data distribution of adversarial samples. In this paper, adversarial samples are used to enrich the training set of the IDS. Then, the IDS diagnosed as weak needs to be retained with this new adversarial training set. The retrained IDS is expected to have a better classification effect for nonadversarial attacks and accurately identify adversarial samples. The adversarial training process is shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

The adversarial training process of the EIFDAA c) 3.3 Evaluation metrics.

The EIFDAA framework starts adversarial training when the number of adversarial samples exceeds num_adversarial_samples. Since normal events appear more frequently than AAs or NAAs, the adversarial samples and attack samples in the retrained dataset are not represented equally compared to normal samples, which may deteriorate the performance of the detection model. To reduce the impact of data imbalance, the adversarial samples and original samples including normal and attack samples, are fused into the training set of the IDS with the same proportion. The process of adversarial training is described in Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2 Adversarial training. |

|---|

| Input: |

| ori_IDS: The pretrained IDS, OTD: The original training datasets, num_adv_samples, adv_samples |

| Output: |

| opt_IDS: The optimization of IDS; |

| size = length(adversarial_samples); if size > num_adv_samples: part_samples = OTD.take(2*num_adv_samples); balance_samples = part_samples.contact(adv_samples); opt_IDS = ori_IDS.train(balance_samples); return opt_IDS; end if |

As defined in Ref. [34], measures such as accuracy, precision, recall and F1-score (F1) are used to evaluate the performance of IDSs. However, as attacks in IIoT environments are small probability events, most of the open intrusion detection datasets, whose attack records account for only a small proportion, suffer from the data imbalance problem. This problem causes the prediction of the classification model trained on these datasets to be more inclined to the labels of normal records. Specifically, the accuracy value is kept at a high level. Therefore, in this paper, only recall, precision and F1 are used to evaluate the performance of IDSs. In addition, the reduction in the performance of the IDS defending against an adversarial attack can be reflected by the detection rate (DR) and the evasion increase rate (EIR) calculated in Ref. [15]. Notably, the DR is equivalent to the recall value. Inspired by studies [15,34], the measures in this paper are formulated by equation (1) ∼ (4).

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

To show the IDS's defence capability for various types of attacks, TP, FP, and FN focus on multiclassification tasks inspired by Ref. [34]. For a certain type of attack, TP is the number of attack samples correctly classified, FP is the number of other samples misclassified as attack samples, and FN is the number of samples misclassified as other samples. Recall represents the proportion of the number of samples successfully predicted to the total number of attack samples. Precision represents the proportion of attack samples to the samples predicted as attack samples. Recall and precision are usually not discussed separately, and F1 is taken as a supplement. The original sample DR (DRori) and adversarial sample DR (DRadv) represent the power of the original IDSs on the original dataset and adversarial sample dataset respectively.

4. Experiments and evaluation

This section verifies and analyses the feasibility of the EIFDAA framework through experiments. The implementation of the evaluation framework is introduced, including the IIoT dataset, IDSs, and adversarial attack algorithms. Additionally, the evaluation results of the IDSs against adversarial attack algorithms are discussed and analyzed, and then adversarial training as an adversarial defence technique is used to improve the robustness of intrusion detection models.

4.1. EIFDAA implementation

In this paper, the TensorFlow package is used as a deep learning framework to implement the EIFDAA framework and neural networks [35]. The Sklearn and FoolBox libraries [36,37] are used to separately conduct ML-based intrusion detection models and various evasion attack algorithms. The experiments are carried out on an Intel(R) Core (TM) i5-7300hq CPU @ 2.50 GHz and an NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1050, 24 GB RAM with Python version 3.8.

4.1.1. Dataset

In this paper, the X-IIoTID dataset is used to verify the feasibility and effectiveness of the EIFDAA framework; it represents the new trend of current network attacks and is a novel dataset from the IIoT environment. Combining various OTs and the new generation of ITs in the IIoT causes challenges for constructing a unified and standard dataset. The author proposed a new approach to adapt to the heterogeneity and interoperability of the IIoT [8]. A generic attack life cycle extracted from the existing threat-driven frameworks (such as CKC, MALC and TT&CK) describes various types and stages of network attacks. It generates nine stages of attacks in which attack techniques and procedures are implemented. The description and label of each stage are shown in Table 1. There are 820834 samples with 59 features after the unnecessary features in this dataset are removed, and 48.66% of the samples are attack samples.

Table 1.

Attack types and description of the X-IIoTID dataset.

| Labels | Stages of attacks | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Normal | Normal samples extracted from benign/normal behaviour |

| 1 | RDoS | Sending a message through the IIoT application protocol threatening to launch a massive DDoS traffic attack to disable the physical devices |

| 2 | Reconnaissance | Searching for desired targets, gathering information, and identifying and selecting attack methods |

| 3 | Weaponization | Gaining a foothold in the target environment and delivering malware to a victim's machine |

| 4 | Lateral Movement | Exploring the target environment, unceasingly thoroughly, and destroying more systems and networks |

| 5 | Exfiltration | Disclosing private and sensitive information associated with IIoT devices |

| 6 | Tampering | Intentionally destroying, manipulating or editing data in transit or at rest |

| 7 | C&C | Establishing a C&C channel that connects its server to the compromised device to perform multiple activities |

| 8 | Exploitation | Exploiting vulnerabilities, writing scripts, and persisting and upgrading permissions |

| 9 | Crypto-Ransomware | Injecting malware to deny access to data or systems and forcing victims to pay in the form of cryptocurrency |

The use and division of the dataset are as follows. The dataset is divided into two parts for training and testing the IDS. Next, the testing set is split into two parts for the original and retrained IDS. In this way, the training set uses 60% of the total samples to train the intrusion detection models and adversarial attack algorithms. Then, 20% of the total samples are chosen to test the original performance of the detectors, and they are transformed into adversarial samples to form an adversarial training set fused with the training set. Finally, the performance of the retrained IDS is assessed with the remaining 20% of the samples.

4.1.2. Data preprocessing

Datasets are often not directly useful for validating programs. For example, character features do not meet the input requirements of machine learning, while numeric features have a wide range of values. The two preprocessing steps are as follows:

-

(1)

Numeration. As the name implies, nonnumeric features are properly transformed into numerical features that can be recognised by machine learning. In the X-IIoTID dataset, protocols and services are character features that are mapped to corresponding numbers. In the case of protocols, “TCP”, “UDP”, and “ICMP” are represented by the numbers 1, 2, and 3, respectively. In particular, the feature OSSEC_alert_lever is numeric but has only five discontinuous values, so it is treated as a character feature.

-

(2)

Normalization. The range of feature values is a crucial factor affecting the experimental results. In this paper, the minimax normalization method is used to standardise each feature within the range of 0–1 for achieving linear mapping, as shown in equation (5).

| (5) |

where is the original value of the feature, is transformed , and 和 are the maximum and minimum of , respectively.

4.1.3. Intrusion detection method

This framework utilises typical machine learning algorithms as intrusion detection methods, referring to Ref. [38], including support vector machine (SVM), decision tree (DT), random forest (RF) and K-nearest neighbour (KNN) methods, whose parameters are the default values in the Sklearn library. To verify that the framework described in this paper closely follows the research frontier of IDS, the experimental subjects also include HyDL-IDS, a hybrid deep learning intrusion detection method proposed in 2022 [39]. This algorithm automatically extracts spatial and temporal features by fusing a CNN and LSTM and has achieved great success on vehicular network intrusion datasets. Table 2, Table 3 show the parameters and structure of the model. Because of the difference in feature numbers of the test dataset, the parameters of the model are modified. The changed model adopts four convolution blocks, and the last layer is altered to adapt the multiclassification task. In addition, 1D-CNN [40] and GRU [41] deep learning algorithms are used as intrusion detection models to enrich the evaluation results, as shown in Table 4.

Table 2.

The parameters of HyDL-IDS.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Conv1 layer | Filters: 8, Kernel size: 3, Activation: “relu” |

| Filters: 16, Kernel size: 5, Activation: “relu” | |

| Filters: 32, Kernel size: 5, Activation: “relu” | |

| Filters: 64, Kernel size: 3, Activation: “relu” | |

| Max pooling layer | Pool_size: 2, Stride: 2 |

| Dropout layer | Rate: 0.2 |

| LSTM layer | Units: 128 |

| dense layer | Units: 128, Activation: “relu” or “softmax" |

| Loss function | Categorical Cross-entropy |

| Optimizer | Adam |

| learning rate | 0.01 |

| Epoch | 20 |

| Batch size | 256 |

Table 3.

The structure of HyDL-IDS.

| Layer (type) | Output Shape | Param # |

|---|---|---|

| conv1d (Conv1D) | (None, 57, 16) | 64 |

| batch_normalization (BatchNo) | (None, 57, 16) | 64 |

| max_pooling1d (MaxPooling1D) | (None, 28, 16) | 0 |

| dropout (Dropout) | (None, 28, 16) | 0 |

| conv1d_1 (Conv1D) | (None, 24, 32) | 2592 |

| batch_normalization_1 (BatchNo) | (None, 24, 32) | 128 |

| max_pooling1d_1 (MaxPooling1D) | (None, 12, 32) | 0 |

| dropout_1 (Dropout) | (None, 12, 32) | 0 |

| conv1d_2 (Conv1D) | (None, 8, 64) | 10304 |

| batch_normalization_2 (BatchNo) | (None, 8, 64) | 256 |

| max_pooling1d_2 (MaxPooling1D) | (None, 4, 64) | 0 |

| dropout_2 (Dropout) | (None, 4, 64) | 0 |

| conv1d_3 (Conv1D) | (None, 2, 128) | 24704 |

| batch_normalization_3 (BatchNo) | (None, 2, 128) | 512 |

| max_pooling1d_3 (MaxPooling1D) | (None, 1, 128) | 0 |

| dropout_3 (Dropout) | (None, 1, 128) | 0 |

| lstm (LSTM) | (None, 256) | 394240 |

| flatten (Flatten) | (None, 256) | 0 |

| dense_6 (Dense) | (None, 256) | 65792 |

| dropout_4 (Dropout) | (None, 256) | 0 |

| dense_7 (Dense) | (None, 10) | 2750 |

| Total params: 501,226 | ||

| Trainable params: 500,746 | ||

| Nontrainable params: 480 |

Table 4.

The structure and parameters of the CNN and GRU.

| Model | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| CNN | Conv1 layer1 | filters: 8, kernel size: 3, activation: “relu” |

| Max pooling layer1 | pool_size: 2, strides: 2 | |

| Conv1 layer2 | filters: 16, kernel size: 5, activation: “relu” | |

| Max pooling layer2 | pool_size: 2, strides: 2 | |

| Conv1 layer3 | filters: 32, kernel size: 5, activation: “relu” | |

| Max pooling layer3 | pool_size: 2, strides: 2 | |

| Conv1 layer4 | filters: 64, kernel size: 3, activation: “relu” | |

| Max pooling layer4 | pool_size: 2, strides: 2 | |

| Flatten | – | |

| Dense1 | units: 128, activation: “relu” | |

| Dense2 | units: 10, activation: “softmax” | |

| Loss function | Categorical Cross-entropy | |

| Optimizer | Adam | |

| learning rate | 0.02 | |

| Epoch | 20 | |

| Batch size | 256 | |

| GRU | GRU layer1 | units: 128, return_sequences = True |

| GRU layer2 | units: 256, return_sequences = False | |

| Flatten | – | |

| Dense1 | units: 256, activation: “relu” | |

| Dense2 | units: 10, activation: “softmax” | |

| Loss function | Categorical Cross-entropy | |

| Optimizer | Adam | |

| learning rate | 0.02 | |

| Epoch | 20 | |

| Batch size | 256 |

4.1.4. Adversarial attack algorithm

The adversarial sample generation library FoolBox implements FGSM, BIM, PGD and DeepFool. The default parameters of FoolBox are set to the hyperparameters of these methods, except eps, which is the disturbance amplitude and uses the disturbance size determined by the classification models.

WGAN is an improved version of the generative adversarial network and uses the EM distance instead of the JS divergence to generate a theoretically stable loss function during the training process [42]. However, WGAN requires the discriminator function to satisfy the 1-Lipschitz function constraint realised by weight clipping, which leads to sample generation with poor quality or failure to converge. Gulrajani et al. [43] proposed WGAN with gradient penalty (WGAN-GP) by using the gradient penalty method instead of weight clipping, which can make the training process of the generative model more stable. In this paper, WGAN-GP is also taken as an adversarial sample generation algorithm to evaluate its capability in adversarial attacks. The structure and parameters of its generator and discriminator modules are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

The structure and parameters of WGAN-GP.

| Module | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| generator | Dense1 | 128 |

| Dense2 | 256 | |

| Dense3 | 128 | |

| Dense4 | Number of features | |

| Activation | Relu | |

| Optimizer | Adam | |

| Learning rate | 0.02 | |

| discriminator | Dense1 | 128 |

| Dense2 | 64 | |

| Dense3 | 32 | |

| Dense4 | 1 | |

| Activation | Relu | |

| Optimizer | Adam | |

| Learning rate | 0.02 | |

| training | Epoch | 10 |

| Batch size | 256 |

4.2. Results and evaluations on X-IIoTID

This section shows the validation results of the EIFDAA framework on the X-IIoTID dataset. The first step is to determine the resilience of the original IDS against nonadversarial attacks. Then, the second step is to evaluate the anti-jamming capability of the IDS against adversarial samples generated by nonadversarial attack samples. The last step is to verify the robustness of the IDS against adversarial samples after adversarial training.

4.2.1. Robustness of various IDSs

The evaluation subjection of EIFDAA is the IDS identifying nonadversarial attacks. This means that the original DR (DRori or Recall) of the detection models against the nonadversarial samples is the core content. The detection results of each intrusion detection model on the nine types of attacks in the X-IIoTID dataset are described in Table 6. It can be seen that the values of DRori for the RDoS class in all intrusion detection models reach an extremely high level above 99%. This shows that they have sufficient ability to detect RDoS attacks in the X-IIoTID datasets. In contrast, the detection models are relatively insensitive to exploitation attacks, where the original DR of the HYDL-IDS decreases to 54.29%, and the other models are only between 71.43% and 94.87%. The reason for this may be that the exploitation attack samples have the smallest proportion in the training set. However, the precision of detecting exploitation attacks by HYDL-IDS reached 95.00%, which shows that there is a high belief in exploitation threats among the samples detected as this attack. It should be noted that there is no considerable difference in the attack detection performance of these classifiers participating in the EIFDAA framework. They are sensitive to all types of attacks in this industrial dataset, which indicates that the current IDSs can defend against nonadversarial attacks.

Table 6.

Original performance of various IDSs on the X-IIoTID dataset.

| Attack | Metric | SVM | DT | RF | KNN | CNN | GRU | HyDL-IDS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C&C | DRori | 72.66 | 89.44 | 85.21 | 75.70 | 82.86 | 85.92 | 68.57 |

| Pre | 73.94 | 85.23 | 97.19 | 81.75 | 98.31 | 79.22 | 1.00 | |

| F1 | 73.30 | 87.29 | 90.81 | 78.61 | 89.92 | 82.43 | 81.36 | |

| Crypto-Ransomware | DRori | 76.36 | 93.48 | 97.83 | 95.65 | 88.89 | 84.78 | 77.78 |

| Pre | 91.30 | 84.31 | 1.00 | 93.62 | 1.00 | 92.86 | 87.50 | |

| F1 | 83.17 | 88.66 | 98.90 | 94.62 | 94.12 | 88.64 | 82.35 | |

| Exfiltration | DRori | 99.66 | 99.77 | 99.82 | 96.78 | 96.82 | 97.73 | 96.25 |

| Pre | 93.97 | 99.77 | 99.95 | 98.61 | 94.86 | 97.78 | 95.01 | |

| F1 | 96.73 | 99.77 | 99.89 | 97.69 | 95.83 | 97.75 | 95.63 | |

| Exploitation | DRori | 94.87 | 88.62 | 84.55 | 71.54 | 71.43 | 78.86 | 54.29 |

| Pre | 60.16 | 93.16 | 99.05 | 88.89 | 96.15 | 88.18 | 95.00 | |

| F1 | 73.63 | 90.83 | 91.23 | 79.28 | 81.97 | 83.26 | 69.09 | |

| Lateral Movement | DRori | 96.27 | 98.52 | 98.05 | 96.76 | 97.98 | 96.63 | 96.31 |

| Pre | 91.12 | 98.52 | 98.05 | 96.76 | 97.98 | 98.84 | 96.31 | |

| F1 | 93.63 | 98.10 | 98.86 | 96.89 | 97.63 | 97.72 | 95.85 | |

| RDoS | DRori | 99.56 | 1.00 | 99.99 | 99.96 | 99.92 | 99.94 | 99.94 |

| Pre | 99.82 | 99.99 | 99.99 | 99.94 | 1.00 | 99.89 | 1.00 | |

| F1 | 99.89 | 99.99 | 1.00 | 99.95 | 99.96 | 99.92 | 99.97 | |

| Reconnaissance | DRori | 97.46 | 98.71 | 98.79 | 96.11 | 89.80 | 93.30 | 87.59 |

| Pre | 86.66 | 98.69 | 99.57 | 96.46 | 99.72 | 97.84 | 98.77 | |

| F1 | 91.73 | 98.70 | 99.18 | 96.28 | 94.50 | 95.51 | 92.84 | |

| Tampering | DRori | 95.66 | 99.04 | 99.42 | 85.55 | 83.48 | 98.84 | 73.91 |

| Pre | 72.25 | 98.47 | 99.61 | 96.31 | 98.97 | 91.44 | 96.59 | |

| F1 | 82.32 | 98.75 | 99.52 | 90.61 | 90.57 | 95.00 | 83.74 | |

| Weaponization | DRori | 94.19 | 99.91 | 99.97 | 99.73 | 98.12 | 99.62 | 97.82 |

| Pre | 91.12 | 99.94 | 1.00 | 98.82 | 98.54 | 98.84 | 97.52 | |

| F1 | 93.63 | 99.92 | 99.98 | 99.27 | 98.33 | 97.72 | 97.67 |

4.2.2. EIFDAA evaluation results

The experiment tests the adversarial attack capabilities of the five generative models, which convert attack samples in the X-IIoTID dataset into the corresponding adversarial samples according to the attack model described in Section 3.1. The IDSs implemented by seven classification models are attacked by the adversarial attacker. This section selects the representative attack behaviours including the reconnaissance and lateral movement attacks to analyse the impact of their adversarial samples on the performance of various detection models. The experimental results are shown in Table 7, Table 8.

Table 7.

EIFDAA framework performance against reconnaissance attack.

| Adversarial method | Metric | SVM | DT | RF | KNN | CNN | GRU | HyDL-IDS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WGAN-GP | Recall | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Precision | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| F1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| EIR | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | |

| FGSM (eps = 10) | Recall | 1.93 | 2.68 | 0.05 | 3.46 | 4.74 | 0.16 | 0.44 |

| Precision | 96.88 | 12.78 | 0.38 | 22.20 | 16.87 | 5.81 | 21.54 | |

| F1 | 3.79 | 4.43 | 0.10 | 5.99 | 7.40 | 0.25 | 0.86 | |

| EIR | 98.10 | 97.28 | 99.95 | 96.40 | 94.72 | 99.83 | 99.50 | |

| BIM (eps = 30) | Recall | 0.00 | 6.28 | 0.99 | 3.75 | 7.70 | 10.01 | 1.99 |

| Precision | 0.00 | 46.84 | 77.30 | 44.51 | 31.83 | 31.50 | 70.67 | |

| F1 | 0.00 | 11.07 | 1.95 | 6.92 | 12.4 | 15.19 | 3.86 | |

| EIR | 100.00 | 93.64 | 99.00 | 96.10 | 91.43 | 89.27 | 97.73 | |

| PGD (eps = 30) | Recall | 0.00 | 14.25 | 0.35 | 6.95 | 11.29 | 0.29 | 35.14 |

| Precision | 0.00 | 27.72 | 33.85 | 33.25 | 30.96 | 18.59 | 21.40 | |

| F1 | 0.00 | 18.82 | 0.68 | 11.49 | 16.54 | 0.57 | 24.30 | |

| EIR | 100.00 | 85.56 | 99.69 | 92.77 | 87.43 | 99.69 | 59.88 | |

| DeepFool (eps = 10) | Recall | 3.21 | 14.19 | 6.66 | 22.76 | 12.78 | 1.90 | 20.39 |

| Precision | 39.77 | 29.41 | 58.11 | 69.33 | 29.69 | 28.91 | 78.51 | |

| F1 | 5.94 | 19.14 | 11.96 | 34.27 | 17.87 | 3.57 | 32.38 | |

| EIR | 96.71 | 85.62 | 93.26 | 76.32 | 85.77 | 97.96 | 76.72 |

Table 8.

EIFDAA framework performance against lateral movement attack.

| Adversarial method | Metric | SVM | DT | RF | KNN | CNN | GRU | HyDL-IDS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WGAN-GP | Recall | 0.00 | 1.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Precision | 0.00 | 17.59 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| F1 | 0.00 | 2.24 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| EIR | 100.00 | 98.78 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | |

| FGSM (eps = 10) | Recall | 0.71 | 8.57 | 0.00 | 4.76 | 6.31 | 0.00 | 0.48 |

| Precision | 5.71 | 15.38 | 0.00 | 4.80 | 6.65 | 0.00 | 2.21 | |

| F1 | 1.27 | 11.01 | 0.00 | 4.78 | 6.48 | 0.00 | 0.79 | |

| EIR | 99.26 | 91.30 | 100.00 | 95.08 | 93.56 | 100.00 | 99.50 | |

| BIM (eps = 30) | Recall | 0.00 | 14.89 | 0.00 | 2.77 | 0.66 | 8.91 | 4.16 |

| Precision | 0.00 | 6.48 | 0.00 | 18.07 | 3.49 | 4.49 | 6.78 | |

| F1 | 0.00 | 9.03 | 0.00 | 4.80 | 1.11 | 5.97 | 5.15 | |

| EIR | 100.00 | 84.89 | 100.00 | 97.13 | 99.33 | 90.78 | 95.68 | |

| PGD (eps = 30) | Recall | 0.00 | 8.44 | 0.00 | 16.72 | 8.41 | 0.09 | 10.36 |

| Precision | 0.00 | 8.06 | 0.00 | 8.01 | 6.76 | 13.64 | 17.90 | |

| F1 | 0.00 | 8.25 | 0.00 | 10.83 | 7.49 | 0.19 | 13.12 | |

| EIR | 100.00 | 91.43 | 100.00 | 82.72 | 91.42 | 99.91 | 89.24 | |

| DeepFool (eps = 10) | Recall | 6.43 | 14.05 | 4.35 | 24.05 | 15.00 | 10.35 | 30.24 |

| Precision | 58.69 | 30.49 | 94.52 | 12.75 | 41.04 | 29.10 | 38.37 | |

| F1 | 11.59 | 19.23 | 8.31 | 16.67 | 21.97 | 15.28 | 33.82 | |

| EIR | 93.32 | 85.74 | 95.56 | 75.14 | 84.69 | 89.29 | 68.60 |

As shown in Table 7, in the rows representing WGAN-GP, the recall, precision and F1 indicators for all detection models are decreased to 0%. An EIR of 100% indicates that all attack samples pass the examination of the IDS. When the target platform is attacked by a reconnaissance attack, all intrusion detection methods will be negated if the WGAN-GP-based adversarial attacker assists the reconnaissance attacker. The IDS's weakness in facing adversarial attacks with WGAN-GP may be ascribed to the adversarial nature of generative adversarial networks. In addition, SVM-based IDS also completely loses detection performance when the detection rate drops to zero when confronting adversarial samples generated by PGD and BIM. Fortunately, the vast majority of experimental results indicate that adversarial attacks do not have such devastating impacts on IDSs, and the WGAN-GP algorithm is just an exception. Whereas, the detection rate of these results is also mostly below 10%. It is worth mentioning that the HyDL-IDS against the PGD algorithm seems to have the best result with the highest recall of 35.14% and EIR of 59.88%. It might be determined that HyDL-IDS is still robust under PGD threat. Furthermore, this shows that the precision of all IDSs detecting adversarial samples generated by FGSM, BIM, PGD, and DeepFool surpasses the recall. This proves that there is a high belief degree that the predicted reconnaissance attack samples are indeed the attack type.

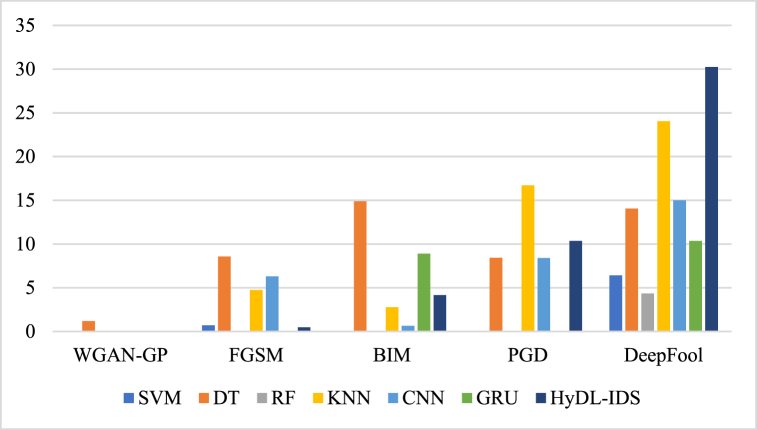

Regarding lateral movement attack, these detection models follow a similar trend on the five adversarial attacks. These IDSs have nearly no ability to handle risks posed by adversarial attacks. The main differences with respect to the reconnaissance attack are as follows. Table 8 shows that DT performs better than other classifiers against adversarial attacks concealing lateral movement attack, with detection rates in the range of 1.2%–14.89%. RF is the worst classifier for detecting adversarial samples generated by 4 of 5 adversarial attack algorithms, and its DR dropped from 98.05% to 0%. IDSs Based on RF, GRU also have a declined detection rate to zero with FGSM. Meanwhile, SVM and RF among these IDSs experience the lowest detection rate of 0% with BIM and PGD. These results indicate that they have no power to handle corresponding adversarial samples. Quite interestingly, HyDL-IDS is still the best player in the game with the DeepFool adversary. It achieves the highest DR of 30.24% and the lowest EIR of 68.6%. However, unlike the WGAN-GP adversarial attack concealing reconnaissance attack in Table 7, DT can still detect the adversarial samples generated by the attack. Although the DR is as low as 1.2%, the WGAN-GP adversarial attack is not indefensible. Moreover, to display the detectability of these IDSs on adversarial samples intuitively, the recall and visualisation of the lateral movement attack can be seen in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Recall of the detection models on the adversarial samples of lateral movement attack.

While observing Fig. 5, it should be noted that classifiers except DT perform best in detection rate for adversarial samples based on DeepFool. In the meantime, a group of adversarial samples using WGAN-GP, FGSM, BIM, and PGD have their DR obtained several classifiers diminish to zero. However, due to the detection rate of nonzero values on each classifier, DeepFool falls out of this group. These results suggest that the attack effect of the DeepFool hiding lateral movement attack is obviously inferior to that of the other attacks. Nevertheless, cybersecurity experts should pay close attention to WGAN-GP-based adversarial attack. Overall, the findings discussed above focus on only two attack types: reconnaissance, and lateral movement attack. However, five other attack types also show the same trend. As HyDL-IDS shows relatively high performance, the original and adversarial DRs (recall) of HyDL-IDS against nine attack samples are depicted in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Recall of HyDL-IDS against multiple types of adversarial attack.

Fig. 6 shows that the HyDL-IDS cannot maintain the detection performance on the original dataset in the face of malicious confusion caused by adversarial samples. Correspondingly, the adversarial samples of the reconnaissance attack concealed PGD and DeepFool have detection rates of 35.14% and 20.39%, respectively. Additionally, HyDL-IDS can maintain detection power against DeepFool on C&C and lateral movement attacks with detection rates of 28.57% and 30.24%, respectively. However, the remaining experimental results have a lower detection rate, which is reduced to less than 13% or even zero. This means that HyDL-IDS almost disrupts its recognisability on adversarial samples crafted by these adversarial attacks.

Overall, the IDSs using these seven machine learning models have quite low detection success rates for adversarial samples generated by each adversarial attack algorithm. Comparing five adversarial attacks, DeepFool is relatively easy to resist for some classifiers with the least decreases. In contrast, WGAN-GP makes many IDSs completely misclassify with a detection rate of nearly zero or even zero. In addition, for seven ML/DL based IDSs, it is difficult to choose the one with the best performance. This situation poses a great threat to IDSs and target IIoT platforms. Hence, the adversarial evaluation of this study is operated as a solution. When the EIFDAA evaluation architecture is deployed in real IIoT platforms, the learned adversarial evaluation can diagnose the IDS and generate adversarial samples to treat the weak IDS.

4.2.3. Adversarial training

This section utilises the experimental results of the evaluating process in EIFDAA for adversarial training of IDSs to improve their sensitivity to adversarial samples. For the lateral movement attack, the retraining results of each detection model are shown in Table 9.

Table 9.

Adversarial training with the lateral movement attacks in X-IIoTID dataset.

| Adversarial method | Metric | SVM | DT | RF | KNN | CNN | GRU | HyDL-IDS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WGAN-GP | DRori | 96.13 | 97.65 | 97.71 | 98.84 | 95.42 | 97.12 | 94.39 |

| DRadv | 80.96 | 91.61 | 98.31 | 96.25 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Precisionori | 55.35 | 99.78 | 99.71 | 96.36 | 99.12 | 99.42 | 98.56 | |

| Precisionadv | 58.01 | 92.65 | 98.09 | 97.27 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| F1ori | 70.25 | 98.70 | 98.70 | 97.59 | 97.24 | 98.26 | 96.43 | |

| F1adv | 67.59 | 92.13 | 98.20 | 96.76 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| FGSM | DRori | 97.19 | 99.59 | 99.36 | 96.39 | 97.09 | 99.45 | 95.05 |

| DRadv | 98.60 | 97.94 | 99.64 | 98.46 | 74.03 | 96.93 | 97.29 | |

| Precisionori | 80.31 | 97.88 | 97.46 | 98.81 | 96.36 | 96.77 | 95.14 | |

| Precisionadv | 99.03 | 98.18 | 99.78 | 98.64 | 90.66 | 96.90 | 94.51 | |

| F1ori | 87.95 | 98.72 | 98.40 | 97.59 | 96.73 | 98.09 | 95.09 | |

| F1adv | 99.44 | 98.06 | 99.71 | 98.56 | 81.51 | 96.91 | 95.88 | |

| BIM | DRori | 97.22 | 99.25 | 99.46 | 98.81 | 95.34 | 99.52 | 95.59 |

| DRadv | 93.01 | 13.43 | 53.29 | 95.72 | 54.41 | 82.88 | 91.45 | |

| Precisionori | 78.99 | 97.18 | 97.46 | 96.39 | 96.30 | 97.08 | 97.30 | |

| Precisionadv | 87.27 | 42.02 | 66.10 | 89.09 | 9.28 | 79.08 | 40.58 | |

| F1ori | 87.16 | 98.19 | 98.45 | 97.59 | 95.82 | 98.29 | 96.44 | |

| F1adv | 90.05 | 20.36 | 59.01 | 92.29 | 15.86 | 80.94 | 56.21 | |

| PGD | DRori | 97.09 | 98.47 | 99.52 | 98.81 | 92.82 | 98.2 | 98.88 |

| DRadv | 76.67 | 17.63 | 59.31 | 35.08 | 8.70 | 38.77 | 0.00 | |

| Precisionori | 77.52 | 96.86 | 97.46 | 96.39 | 95.2 | 97.55 | 91.56 | |

| Precisionadv | 0.72 | 15.77 | 27.47 | 14.27 | 0.25 | 18.34 | 0.00 | |

| F1ori | 86.21 | 97.66 | 98.48 | 97.59 | 93.99 | 97.88 | 95.08 | |

| F1adv | 1.43 | 16.56 | 37.55 | 20.29 | 0.49 | 24.90 | 0.00 | |

| DeepFool | DRori | 97.45 | 98.72 | 99.81 | 98.85 | 97.76 | 99.58 | 98.59 |

| DRadv | 96.97 | 97.59 | 99.42 | 97.59 | 90.34 | 98.71 | 91.50 | |

| Precisionori | 70.62 | 96.74 | 97.84 | 97.08 | 86.14 | 96.96 | 94.58 | |

| Precisionadv | 85.42 | 95.23 | 97.59 | 96.68 | 83.29 | 96.08 | 92.82 | |

| F1ori | 81.89 | 97.72 | 98.81 | 97.96 | 91.58 | 98.25 | 96.54 | |

| F1adv | 90.83 | 96.40 | 98.50 | 97.13 | 86.67 | 97.38 | 92.15 |

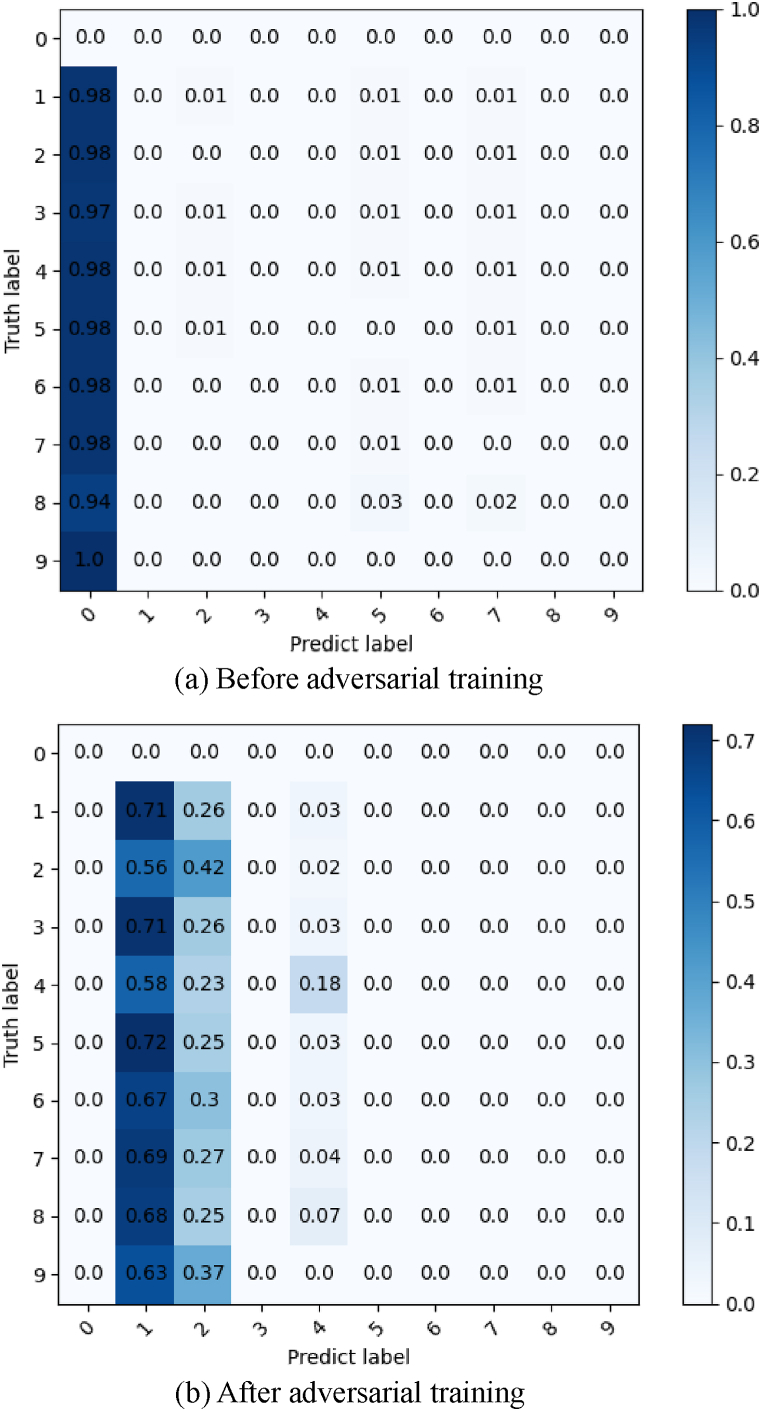

It should be stated that the measures with ori subindices are used to evaluate retrained IDS on original samples. Compared with Table 8, Table 9 shows that the detector after adversarial training still maintains an original detection success rate for nonadversarial attacks. Meanwhile, the detection results of most adversarial samples have returned to the original level. However, some adversarial samples seem to have strong attack capabilities, and the new IDSs still cannot regain the original detection effect. It can be observed that IDSs using CNN, GRU, and HyDL do not have any increases in DR, precision, or F1 with adversarial samples from WGAN-GP. Strangely, the detection rate of the fresh HyDL-IDS against PGD dropped from 10.36% to zero. A similar decline from 14.89% to 13.43% also appears in the period of DT against BIM. Furthermore, for the PGD attack, 6 of 7 classifiers were able to regain slight detection power but not to the original level. These results mean that the IDSs based on these models cannot retrieve excellent performance through adversarial training. To explain and analyse this situation, the confusion matrix of the CNN before and after adversarial training, on the adversarial samples generated by the WGAN-GP, is shown in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Confusion matrix of a CNN against adversarial samples generated by WGAN-GP.

As illustrated in Fig. 7, the first row in this confusion matrix has a value of zero, which indicates that there are no adversarial samples transformed from normal samples. In Fig. 7a, before adversarial training, the CNN-based IDS misclassifies more than 94% of the adversarial samples as the normal class. This result confirms the findings in Table 8 and provides an interpretation of how WGAN-GP can destroy the CNN-based IDS. Afterwards, the results after retraining with adversarial samples are represented in Fig. 7b. The optimised CNN classifier can identify attack samples due to the ratio of all zeros in the first predicted label. The crafted samples are aggregated into RDoS and reconnaissance attacks and are not placed in corresponding attack types. This means that the fresh CNN-based IDS can correctly diagnose these adversarial samples that are harmful to the target platform, but the actual attack types cannot be determined. Hence, in this case, the platform is still secure while the IDS is not considered robust.

According to the results of all the experiments, the feasibility and effectiveness of the EIFDAA have been confirmed. The adversarial evaluation of this framework can diagnose the weak IDS against adversarial attacks deployed in the IIoT platform. Additionally, adversarial training can improve the robustness of the weak IDS on adversarial samples. This EIFDAA framework is recommended for deployment in the IDS of the IIoT platform.

5. Conclusion and future work

This paper introduces a security assessment framework, called EIFDAA, that is designed for IDS deployed in IIoT platforms. EIFDAA evaluates the ability of the IDS to detect deceptive samples created by adversarial attacks. This framework includes two important steps: adversarial evaluation and adversarial training. First, diagnosing the security status of the IDS confronting adversarial attacks and collecting adversarial samples for the next step are the crucial tasks of adversarial evaluation. As the IDS using machine learning techniques can be easily fooled by adversarial attackers with tricked samples, estimating the evasion capability of the IDS to adversarial attack is the primary matter in real scenarios. Second, deceptive samples are leveraged to harden the IDS deployed in the practical network to enhance the robustness in adversarial samples. Furthermore, the adversarial attack model proposed in this paper does not retain the attack capability by modifying all features. The experiments on the IIoT dataset show that adversarial attack with this attack model can cause a devastating effect on the IDSs. The optimised IDSs also have remarkable increases in the detection rate while maintaining the original detection level. In addition, the security framework can be integrated into IIoT business platforms to ensure the security of the IDSs.

Nevertheless, cyber attack events are not frequent in the network environment, and the IDS cannot completely hunt all attack records. Therefore, collecting enough adversarial samples in adversarial evaluation may be unrealistic. In addition, the retrained classifiers do not have the capability to achieve target attack detection, which may be the imperious demands of the platforms. In the future, the generality of the EIFDAA framework will be verified on more IIoT datasets by considering other advanced adversarial attack algorithms and intrusion detection models. Meanwhile, more adversarial defence techniques with better performance are appended into this framework. Target adversarial attack detection is also considered in adversarial defence. Finally, for the security of IIoT platforms, in addition to adversarial attacks that can threaten IDS, other cyber threats or even unknown attacks can also cause detriment to complex systems. Fully guaranteeing the security of IIoT platforms is an important issue for future work.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Shiming Li, Jingxuan Wang: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper. Yuhe Wang, Guohui Zhou, Yan Zhao: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the Provincial Universities Basic Business Expense Scientific Research Projects of Heilongjiang Province (No. 2021-KYYWF-0179), the Science and Technology Project of Henan Province (No. 212102310991), the Key Scientific Research Project of Henan Province (No. 21A413001), and the Postgraduate Innovation Project of Harbin Normal University (No. HSDSSCX2021-121).

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supp. material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interest's statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Zhang P., Wu Y., Zhu H. Open ecosystem for future industrial Internet of things (IIoT): architecture and application. CSEE Journal of Power and Energy Systems. 2020;6(1):1–11. doi: 10.17775/CSEEJPES.2019.01810. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sisinni E., Saifullah A., Han S., Jennehag U., Gidlund M. Industrial internet of things: challenges opportunities and directions. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 2018;14(11):4724–4734. doi: 10.1109/TII.2018.2852491. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marzano A., et al. The evolution of bashlite and Mirai IoT botnets. Proc. IEEE Symp. Comput. Commun. 2018:813–818. doi: 10.1109/ISCC.2018.8538636. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abosata N., Al-Rubaye S., Inalhan G., Emmanouilidis C. Internet of things for system integrity: a comprehensive survey on security, attacks and countermeasures for industrial applications. Sensors. 2021;21:11. doi: 10.3390/s21113654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alanazi M., Aljuhani A. Anomaly detection for internet of things cyberattacks. Comput. Mater. Continua (CMC) 2022;72(1):261–279. doi: 10.32604/cmc.2022.024496. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jmila Houda, Mohamed Ibn Khedher Adversarial machine learning for network intrusion detection: a comparative study. Comput. Network. 2022;214 doi: 10.1016/j.comnet.2022.109073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen J., Gao X., Deng R., He Y., Fang C., Cheng P. Generating adversarial examples against machine learning-based intrusion detector in industrial control systems. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secure Comput. 2022;19(3):1810–1825. doi: 10.1109/TDSC.2020.3037500. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Hawawreh M., Sitnikova E., Aboutorab N., IioTID X.- A connectivity-agnostic and device-agnostic intrusion data set for industrial internet of things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;9(5):3962–3977. doi: 10.1109/JIOT.2021.3102056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang C., Costa-Pérez X., Patras P. Adversarial attacks against deep learning-based network intrusion detection systems and defense mechanisms. IEEE/ACM Trans. Netw. 2022;30(3):1294–1311. doi: 10.1109/TNET.2021.3137084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qiu H., Dong T., Zhang T., Lu J., Memmi G., Qiu M. Adversarial attacks against network intrusion detection in IoT systems. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021;8(13):10327–10335. doi: 10.1109/JIOT.2020.3048038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang H.L., Lin J.Z., Kang H.Y. FGMD: a robust detector against adversarial attacks in the IoT network. Future Generation Computer Systems-The Int. J. ESci. 2022;132:194–210. doi: 10.1016/j.future.2022.02.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tcydenova E., Kim T.W., Lee C., Park J.H. Detection of adversarial attacks in AI-based intrusion detection systems using explainable AI. Human-Centric Comput. Info. Sci. 2021;11 doi: 10.22967/HCIS.2021.11.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muhammad Shahzad H., Husnain Mansoor A. Adversarial training against adversarial attacks for machine learning-based intrusion detection systems. Comput. Mater. Continua (CMC) 2022;73:3513–3527. doi: 10.32604/cmc.2022.029858. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khamis R.A., Matrawy A. 2020 International Symposium on Networks, Computers and Communications (ISNCC) 2020. Evaluation of adversarial training on different types of neural networks in deep learning-based IDSs; pp. 1–6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duy P.T., Le K.T., Khoa N.H., et al. DIGFuPAS: deceive IDS with GAN and function-preserving on adversarial samples in SDN-enabled networks. Comput. Secur. 2021;109 doi: 10.1016/j.cose.2021.102367. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodfellow I.J., Shlens J., Szegedy C. 2014. Explaining and Harnessing Adversarial Examples. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurakin A., Goodfellow I., Bengio S. Adversarial machine learning at scale. ICLR. 2017 doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1611.01236. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Madry A., Makelov A., Schmidt L., Tsipras D., Vladu A. International Conference on Learning Representations; 2018. Towards Deep Learning Models Resistant to Adversarial Attacks. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moosavi-Dezfooli S.M., Fawzi A., Frossard P. Proc. of the IEEE Computer Society Conf. on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Las Vegas, NV; USA: 2016. DeepFool: a simple and accurate method to fool deep neural networks; pp. 2574–2582. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szegedy C., Zaremba W., Sutskever I., et al. Intriguing properties of neural networks. Computer Sci. 2013 doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1312.6199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ibitoye O., Shafiq O., Matrawy A. IEEE Global Communications Conference (GLOBECOM) 2019. Analyzing adversarial attacks against deep learning for intrusion detection in IoT networks; pp. 1–6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anthi E., Williams L., Rhode M., et al. Adversarial attacks on machine learning cybersecurity defences in Industrial Control Systems. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2021;58:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jisa.2020.102717. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang E., Prasad Joshi G., Seo C. Improving the detection rate of rarely appearing intrusions in network-based intrusion detection systems. Comput. Mater. Continua (CMC) 2021;66(2):1647–1663. doi: 10.32604/cmc.2020.013210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim T., Pak W. Real-time network intrusion detection using deferred decision and hybrid classifier. Future Generat. Comput. Syst. 2022;132:51–66. doi: 10.1016/j.future.2022.02.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boyes H., Hallaq B., Cunningham J., Watson T. The industrial internet of things (IIoT): an analysis framework. Comput. Ind. 2018;101:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.compind.2018.04.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahmad Z., Shahid Khan A., Wai Shiang C., Abdullah J., Ahmad F. Network intrusion detection system: a systematic study of machine learning and deep learning approaches. Transact. Emerging Telecommun. Technol. 2021;32 doi: 10.1002/ett.4150. 1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Priya V., Sumaiya Thaseen I., Reddy Gadekallu T., Aboudaif M.K., Abouel Nasr E. Robust attack detection approach for IIoT using ensemble classifier. Comput. Mater. Continua (CMC) 2021;66(3):2457–2470. doi: 10.32604/cmc.2021.013852. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vaccari I., Carlevaro A., Narteni S., Cambiaso E., Mongelli M. eXplainable and reliable against adversarial machine learning in data analytics. IEEE Access. 2022;10:83949–83970. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3197299. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nowroozi E., Dehghantanha A., Parizi R.M., Choo K.K.R. A survey of machine learning techniques in adversarial image forensics. Comput. Secur. 2021;100 doi: 10.1016/j.cose.2020.102092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carlini N., Wagner D. IEEE Security and Privacy Workshops (SPW); 2018. Audio Adversarial Examples: Targeted Attacks on Speech-To-Text; pp. 1–7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tu J., et al. Physically realizable adversarial examples for LiDAR object detection. IEEE/CVF Conf. Comput. Vision Pattern Recognit. (CVPR) 2020;13:13713–13722. doi: 10.1109/CVPR42600.2020.01373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Izzat A., Nura A., Mahmoud N., et al. Adversarial machine learning in text processing: a literature survey. IEEE Access. 2022;10:17043–17077. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3146405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim H., Han J. Effects of adversarial training on the safety of classification models. Symmetry-Basel. 2022;14 doi: 10.3390/sym14071338. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zheng W. Deep learning-based intrusion detection with adversaries. IEEE Access. 2018;6:38367–38384. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2854599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.TensorFlow. https://www.tensorflow.org Accessed: Apr. 21, 2018. [Online]. Available:

- 36.Pedregosa F., Varoquaux G., Gramfort A., Michel V., et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011;12:2825–2830. doi: 10.1524/auto.2011.0951. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rauber J., Brendel W., Bethge M. 2017. FoolBox: A Python Tool-Box to Benchmark the Robustness of Machine Learning Models. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shuang Z.A., Jing L.B., Jw C., et al. AttackGAN: adversarial attack against black-box IDS using generative adversarial networks. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021;187:128–133. doi: 10.1016/j.procs.2021.04.118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lo W., Alqahtani H., Thakur K., et al. A hybrid deep learning based intrusion detection system using spatial-temporal representation of in-vehicle network traffic. Vehicular Communications. 2022;35 doi: 10.1016/j.vehcom.2022.100471. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qazi E.U., Almorjan A., Zia T. A one-dimensional convolutional neural network (1D-CNN) based deep learning system for network intrusion detection. Appl. Sci.-Basel. 2022;12:16. doi: 10.3390/app12167986. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ma H.Y., Cao J.Q., Mi B., Huang D.R., Liu Y., Li S.Q. A GRU-based lightweight system for CAN intrusion detection in real time. Secur. Commun. Network. 2022;2022 doi: 10.1155/2022/5827056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arjovsky M., Chintala S., Bottou L., Gan Wasserstein. International Conference on Machine Learning. 2017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gulrajani I., Ahmed F., Arjovsky M., Dumoulin V., Courville A.C. NIPS); 2017. Improved Training of Wasserstein GAN, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; pp. 5769–5779. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supp. material/referenced in article.