Abstract

Compelling shreds of evidence derived from both clinical and experimental research have demonstrated the crucial contribution of receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) axis activation in the development of neoplasms, including gastric cancer (GC). This new actor in tumor biology plays an important role in the onset of a crucial and long-lasting inflammatory milieu, not only by supporting phenotypic changes favoring growth and dissemination of tumor cells, but also by functioning as a pattern-recognition receptor in the inflammatory response to Helicobacter pylori infection. In the present review, we aim to highlight how the overexpression and activation of the RAGE axis contributes to the proliferation and survival of GC cells as and their acquisition of more invasive phenotypes that promote dissemination and metastasis. Finally, the contribution of some single nucleotide polymorphisms in the RAGE gene as susceptibility or poor prognosis factors is also discussed.

Keywords: Gastric cancer, Advanced glycation end-products, Receptor of advanced glycation end-products, Alarmins, Helicobacter pylori, Chronic inflammation

Core Tip: During the last two decades, new evidence supported by basic and clinical research has supported the role of the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) axis as a crucial actor in gastric carcinogenesis. We herein discuss how RAGE overexpression and RAGE activation-mediated signaling mechanisms are the main contributions of the RAGE axis to tumor development, migration, and metastasis in gastric cancer.

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer (GC) is the fifth most common cancer and the fourth leading cause of cancer death worldwide[1]. It remains one of the most lethal neoplasms, with a 5-year survival rate of around 20%[2].

Although GC incidence and mortality rates have declined worldwide during the last decades, it still remains a very important clinical and public health issue. Important research efforts have shed new light not only on the main associated risk factors for development of GC, but also to the identification of crucial mechanistic contributors to gastric carcinogenesis[3-7]. Among these newly defined contributors to tumor growth and development of many cancer types, the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) multiligand axis has gained the attention of many research groups due to the diversity of mechanistic contributions to cancer growth and development supported by the complex signaling of the axis[5,8-11].

This review primarily highlights how the RAGE axis is involved in gastric carcinogenesis, focusing on its early contribution to the onset of a chronic inflammatory condition at the gastric epithelium and its role in tumor growth and development.

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF GC

A stated above, GC is the fourth most common cancer and the fourth leading cause of cancer death worldwide[1], despite the improvement of public health policies throughout the world to decrease the incidence and mortality rates from GC[12,13]. International reports have shown that the annual number of new GC cases is estimated to increase by 62% by 2024, especially in geographic areas of high-burden disease such as Asia, Eastern Europe, and South America[14]. The main risk factor for GC is infection by the bacterium Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), due to this microorganism’s ability to induce chronic inflammation in the gastric mucosa, atrophy of gastric glands, gastric intestinal metaplasia (IM), and carcinogenesis[14,15]. H. pylori infection is associated with 60%-80% of GC cases, as evidenced by extensive cohort studies of high-risk populations[16,17].

It is estimated that H. pylori infection is currently present in more than half of the world’s population (4.4 billion people)[18]. Strikingly, only a small fraction of these H. pylori-infected individuals develop GC, with incidence ranging from 2% to 5%[19], strongly suggesting that GC development cannot only be explained by H. pylori infection. Accordingly, we must consider the role of different contributors to the sustained chronic inflammation observed in H. pylori-induced gastric carcinogenesis[5,20].

INFLAMMATION AND GC

In the 19th century, Rudolf Virchow outlined the putative connection between inflammation and cancer[21]. At present, there is compelling evidence supporting the role of chronic inflammation in organ-specific carcinogenesis, as is observed with H. pylori-induced gastric inflammation and the development of GC, gastric mucosa lymphoma[22], prostatitis and prostate cancer[23], chronic cholecystitis and gallbladder carcinoma[24], acid reflux–induced esophageal adenocarcinoma[25], and hepatocellular neoplasms associated with chronic viral hepatitis[26].

These data have increased our understanding of how chronic inflammation can promote not only the initiation of malignant transformation, but also the sculpting of the tumor microenvironment, and its transformation into a tumor-supportive niche. Through these mechanisms, inflammation can promote proliferation and survival of malignant cells, cancer cell acquisition of invasive phenotypes, dysregulation of the antitumoral immune response, and cancer cell resistance to chemotherapeutic agents[27,28]. The International Agency for Research on Cancer has recognized the bacterium H. pylori as a class 1 carcinogen[29]. In addition, recent evidence supports H. pylori’s causal role in the majority of cases of cardia- and non-cardia GC[17].

The persistent inflammation caused by chronic H. pylori infection in the gastric mucosal epithelium is a critical initiating factor in the multistep processes of gastric carcinogenesis, also known as Correa’s cascade: (1) Chronic inflammation; (2) atrophic gastritis; (3) metaplasia; (4); dysplasia; and (5) adenocarcinoma[16].

H. PYLORI-MEDIATED INFLAMMATION

H. pylori infection incites an inflammatory reaction through myriad mechanisms in gastric epithelial cells and circulating immune cells recruited to the site of infection. Inflammation can be triggered by classical pathogenicity factors such as CagA, cagPAI, urease, and outer membrane proteins, which all play roles in nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) activation[30]. Outer membrane adhesion proteins such as OipA and BabA are involved in the induction of cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and IL-8. CagA can also induce a marked IL-8 production, which is crucial to the recruitment of inflammatory cells and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production. Additionally, the contribution of H. pylori to an inflammatory milieu is supported by its induction of cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) and inducible nitric oxide synthase transcription, which lead to enhanced production of inflammatory mediators prostaglandin E2 and nitric oxide, respectively[31-33].

However, the earliest activation of proinflammatory pathways is associated with the sensing capacity of the innate immune response via pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), which can recognize evolutionarily-conserved structures found on pathogens, termed pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs)[34]. Of note, PRRs can also recognize many structures known as alarmins, or damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), which are associated with cellular necrosis in the setting of noxious stimuli such as inflammation[35]. PRRs play a pivotal role in the inflammatory response to H. pylori infection by recognizing both PAMPs and DAMPs. A compelling body of evidence supports the relevance of several PRRs in the immune response to H. pylori, including Toll-like receptors, NOD-like receptors, RIG-I-like receptors, C-type lectin receptors, and more recently the RAGE[36,37].

THE RAGE AXIS

RAGE was initially recognized due to its ability to bind advanced glycation end products (AGEs). AGEs are a wide and diverse group of molecules derived via structural modifications of proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, which all become non-enzymatically glycated by reducing sugars[38].

RAGE is a member of the immunoglobulin (Ig) superfamily. The human RAGE gene is located on chromosome 6p21.3, in the class II/III junction of the major histocompatibility complex locus and lies adjacent to the homeobox gene HOX12. The mature RAGE protein is 404 amino acids long with three major regions: an extracellular segment, a transmembrane segment, and an intracellular segment. The extracellular segment of RAGE is responsible for its ligand binding capacity and has three Ig domains, termed V-type, C1-type, and C2-type[39-42].

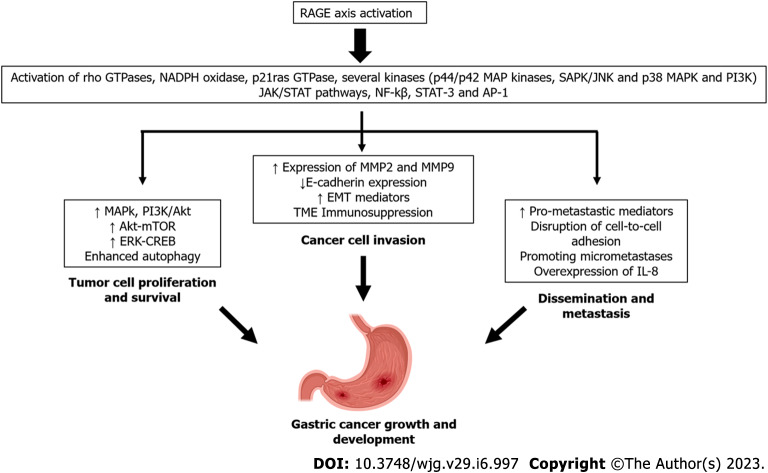

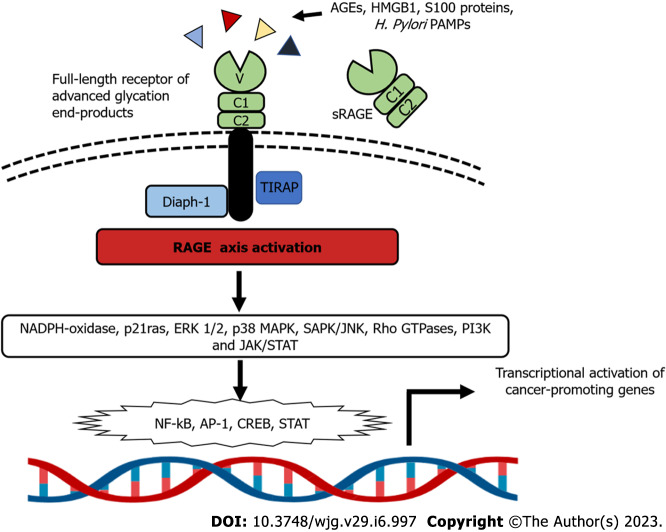

The integrated structural unit of the V and C1 domains is primarily responsible for interactions with a diverse group of negatively-charged RAGE ligands, including S100/calgranulins, AGEs, high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) proteins, and Aβ-proteins[43]. The intracellular region of RAGE can also bind key molecules to activate downstream signaling, as reported in the cases of diaphanous-related formin 1 and toll-interleukin 1 receptor domain-containing adaptor protein (TIRAP)[44-46]. Soluble forms of RAGE, also known as soluble RAGE (sRAGE), have been identified and found in many fluid compartments, including serum[47,48]. These soluble variants arise from two main mechanisms: (1) Alternative splicing; and (2) enzymatic cleavage via the actions of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), disintegrin, and metalloprotease domain-containing protein 10[49]. RAGE activation by ligand binding triggers complex signaling cascades, leading to the activation of transcription factors such as NF-κB, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), hypoxia-inducible factor-1α, activator protein-1, and cyclic-AMP response element binding (CREB). RAGE activation also stimulates p21ras, extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) 1/2, p38 MAPK, stress-activated protein kinase/c-Jun n-terminal kinase, Rho GTPase, the PI3K and Janus kinase/STAT pathways. Accordingly, RAGE activation leads to a robust proinflammatory gene expression profile[50,51] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Receptor for advanced glycation end products engagement by several ligands such as advanced glycation end products, high mobility group box 1, S-100 calgranulin family proteins, and pathogen-associated molecular patterns from Helicobacter pylori. Receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) activation by these various ligands triggers complex signaling cascades and consequently, the activation of a gene transcriptional profile that supports growth and development of gastric cancer. Soluble forms of RAGE (sRAGE) function as decoy receptors and do not activate RAGE signaling. Some adaptor molecules, such as mDia1 and toll-interleukin 1 receptor domain-containing adaptor protein, are required for optimal signaling. AP-1: Activator protein-1; CREB: Cyclic-AMP response element binding; EMT: Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition; ERK: Extracellular signal-regulated kinase; H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori; IL-8: Interleukin-8; JAK: Janus kinase; JNK: c-Jun n-terminal kinase; MMP: Metalloproteinases; mTOR: Mechanistic target of rapamycin; NF-ҡB: Nuclear factor-kappa B; SAPK: Stress-activated protein kinase; STAT: Signal transducer and activator of transcription.

Additionally, RAGE activation causes a positive feed-forward loop, where inflammatory stimuli activate NF-κB, which induces RAGE expression followed by sustained NF-κB activation[52].

The complexity of RAGE signaling is further expanded by its interaction at the plasma membrane with other receptors, such as the chemotactic G-protein-coupled receptors formyl peptide receptors 1 (FPR1) and FPR2, as well as the leukotriene B4 receptor 1[53]. Additionally, adaptor proteins for Toll like receptor 2 (TLR-2) and TLR-4 such as TIRAP and MyD88 also bind to the cytoplasmatic domain of RAGE, when phosphorylated at Ser 391 by PKC-zeta, following other ligand-mediated activation of RAGE[54].

The gene encoding RAGE is highly polymorphic, and several single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within this gene have been described. Compelling data support the role of RAGE gene polymorphisms in the onset and severity of several diseases, including cancer[55].

At present, RAGE is widely recognized as a PRR[56-58]. Beyond the AGEs, RAGE also acts a signaling receptor for various DAMPs or alarmins, such as members of the S100/calgranulin family, HMGB1, amyloid-beta (β) peptide, β-sheet fibrils, lysophosphatidic acid, Mac-1, phosphatidylserine, lipopolysaccharide, the complement component C3a, CpG oligos, and nucleic acids[59,60]. The emerging role of RAGE in sensing not only DAMPs but also PAMPs has been documented[61,62]. RAGE has also been reported to mediate the adherence of some pathogens to target cells by recognizing outer membrane proteins, as reported in the case of mycobacteria[63]. Of note, RAGE not only contributes to the adherence of H. pylori to gastric epithelial cells, but also to the production of the inflammatory response. This increase in RAGE expression and the amplification of the inflammatory cascade therefore culminates in H. pylori-induced gastric inflammation[64]. This finding is particularly interesting because this pathogen also uses another PRR, TLR-4, as a receptor for binding to gastric epithelial cells[65,66].

THE RAGE AXIS: AN EMERGING ACTOR IN TUMOR BIOLOGY

In the year 2000, an article published by Schmidt et al[67] outlined various RAGE axis contributions to pathophysiology. This study demonstrated its active participation in tumor biology, as the blockage of RAGE was shown to decrease tumor growth and metastases in vivo. Since then, additional compelling pieces of evidence have also demonstrated RAGE’s contribution to carcinogenesis and have highlighted its expression levels on both tumor and stromal cells, the high diversity of signaling cascades triggered upon RAGE activation, its wide repertoire, and the abundance of RAGE ligands in the tumor microenvironment[68-70]. RAGE axis activation contributes to critical processes during tumorigenesis, such as the promotion of genetic instability, the initiation of chronic inflammation, the induction of phenotypic changes in tumor cells favoring growth and dissemination, and the support of an immunosuppressive environment[71,72].

Based on the growing body of evidence supporting the crucial role of the RAGE axis in many human pathologies, including cancer, and the availability of the 1.5 Å resolution crystal structure of the receptor, the RAGE axis has become an attractive target for the development of pharmacological interventions. Notably, the design and even the virtual screening of RAGE antagonists and signaling inhibitors (e.g., small-molecule inhibitors, natural products) has demonstrated the feasibility for inhibition of RAGE signal transduction, regardless of the nature of the ligand[51,73].

RAGE AXIS CONTRIBUTION TO GC

Tumor cell proliferation and survival

HMGB1 is a classical RAGE ligand with recognized roles in tumor biology. Of note, HMGB1 is overexpressed in gastric tumors, and a recent systematic meta-analysis demonstrated that HMGB1 plays an important role in GC, and its expression significantly correlates with tumor pT stage[74].

HMGB1-mediated RAGE activation triggers either MAPK or PI3K/AKT signaling and thus enhances tumor cell proliferation in different cancer cell types[75,76]. Additionally, data derived from in vitro experiments support the role of HMGB1 in promoting GC cell proliferation and migration via activation of RAGE-mediated Akt-mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) and ERK-CREB signaling pathways, as well by initiation of a positive feedback loop that increases RAGE expression via these pathways. Furthermore, HMGB1 increases the expression levels of cyclin D1, cyclin E1, and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), and HMGB1 knockdown reduces the expression of these proteins in GC cells[77].

The role in cancer cell proliferation of the S100 Calcium Binding Protein A16 (S100A16) remains controversial in some cancer types[78,79]. However, this alarmin is reported to promote cancer cell proliferation, migration, and invasion. in vivo and in vitro analyses revealed that S100A16 promotes both tumor cell proliferation and migration, whereas S100A16 knockdown abolished both[80]. Autophagy is a lysosome-mediated, self-degradation process that has emerged as key in protecting normal cells via the elimination of damaged organelles and protein aggregates and supporting bioenergetic homeostasis[81]. Autophagy can suppress the initiation of tumor development, or, in contrast, activate tumor cell survival, growth, and malignancy by facilitating access to metabolic demands during tumor progression and supporting tumor cell survival under stress[82-84].

The role of autophagy in GC progression, metastasis, and overall prognosis has been extensively documented[85,86]. Of note, HMGB1 released by autophagic GC cells through a RAGE-dependent mechanism acts as a pro-survival signal for remaining tumor cells, supporting cancer cell survival and promoting resistance to chemotherapy[87] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Overview of RAGE-dependent intracellular signaling. RAGE binding triggers myriad mechanisms that support tumor proliferation and survival, invasion, and metastasis. AGE: Advanced glycation end product; AP-1: Activator protein-1; CREB: cyclic-AMP response element binding; ERK: Extracellular signal-regulated kinase; HMGB1: High mobility group box 1; JAK: Janus kinase; JNK: c-Jun n-terminal kinase; NF-ҡB: Nuclear factor-kappa B; PAMP: Pathogen-associated molecular patterns; RAGE: Receptor for advanced glycation end products; SAPK: Stress-activated protein kinase; STAT: Signal transducer and activator of transcription; TIRAP: Toll-interleukin 1 receptor domain-containing adaptor protein.

Cancer cell invasion

Decades of research have demonstrated that the RAGE axis and its associated proinflammatory downstream pathways act as key mediators of carcinogenesis[88], especially in gastrointestinal tumor development[89].

Among different cancer cell types, RAGE overexpression has been largely recognized as a pathological feature associated with increased tumor development, high invasiveness of cancer cells, and overall poor clinical prognosis[90-92].

The first experimental evidence supporting a correlation between RAGE overexpression and increased invasive and metastatic activity of GC cells was reported in 2002 by Kuniyasu et al[93]. This study revealed that RAGE axis signaling in gastric tumors may promote the acquisition of an invasive phenotype by increasing MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression, decreasing E-cadherin expression, and promoting tumor growth in a MAPkinase-dependent manner.

More recently, the analysis of RAGE expression in primary GC tissue reported by Wang et al[94] demonstrates that the upregulation of RAGE is associated with histological grade, nodal status, metastasis status, and American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage in GC. RAGE upregulation is also associated with shorter overall survival rates. These data suggest that RAGE expression could be considered an independent predictor of GC aggressiveness and prognosis.

RAGE axis activation can have great influence on the invasive capacity of GC tumor cells through the modulation of cellular adhesion, motility, and production of MMPs. These functions are critical for epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT)[9,10], a complex process by which epithelial cells transdifferentiate to mesenchymal phenotypes. EMT is normally present during embryogenesis, tissue morphogenesis, wound healing, and regulation of stem cell behavior[95]. During this process, epithelial cells lose basal adhesion and demonstrate downregulation of epithelial cell markers (e.g., E-cadherin) and upregulation of mesenchymal markers (e.g., vimentin and fibronectin). These changes are also accompanied by increased expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9, which favors the degradation of ECM proteins[96]. EMT is a key mediator of the invasive and dissemination capacities of almost all types of cancer cells[97], including GC[98,99].

RAGE ligands have also been associated with cancer cell invasion and progression[100,101]. For example, the cancer-promoting role of HMGB1 has been extensively reported as a prognostic factor in many cancer types[74]. Importantly, differential expression analysis has shown that HMGB1 is increased in gastric adenocarcinoma cells[100] and has been directly associated with higher tumor stage, lymph node metastasis, depth of invasion, macrophage infiltration in the tumor microenvironment, and antineoplastic drug resistance[102-105]. Moreover, increased HMGB1 has also been correlated with poor prognosis and overall survival in GC[106-109].

In vitro and in vivo assays have demonstrated that high concentrations of extracellular HMGB1 can directly impact the progression of GC cells through the induction of IL-8, which promotes tumor angiogenesis via increasing vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and TNF-α expression[110]. Increased HMGBI also works to favor tumor invasiveness and promote EMT through RAGE-dependent activation of ERK 1/2 and NF-κB[111]. Recent experiments have also confirmed that HMGB1 activation of the RAGE axis can strongly regulate direct EMT mediators in GC cells via downregulation of E-cadherin, as well as by upregulation of transcription factors of Snail and Slug[111] and MMPs (e.g., MMP-9 and MMP-2), whereas the knockdown of HMGB1 showed opposite effects. These results implicate HMGB1 is a key mediator of RAGE-dependent EMT, acting to favor the expression of more invasive GC cell phenotypes[77]. To this end, compelling data have revealed that RAGE knockdown in GC cells suppresses cell growth, invasion, and metastasis through the downregulation of RAGE-related pro-tumoral mediators of EMT (e.g., Akt, PCNA, and MMP-2)[112]. Additionally, the knockdown of the HMGB1 gene inhibits cell proliferation and the invasive potential of GC cells via suppression of RAGE-dependent NF-κB activation[113].

The S100 calcium-binding protein family member S100A8/A9 is a proinflammatory heterodimer produced by both myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and tumor cells[114]. S100A8 and S100A9 form a heterodimeric complex to interact with RAGE, promoting pro-tumoral signaling pathways within cancer cells[115]. Of note, serial analyses of gene expression reported significant overexpression of the genes encoding S100A8 and S100A9 in GC cells when compared to normal gastric epithelial cells[116]. In addition, in vitro evidence has revealed that these calcium-binding proteins are critical in promoting the invasive and migratory phenotype in GC cells through the engagement of RAGE and its pro-tumoral signaling pathways (e.g., p38, MAPK, and NF-ҡB). These RAGE-activated pathways further mediate S100A8/A9-induced migration and invasion in GC[116,117]. For example, Yong and Moon[118] studied siRNA blockade of S100A8/A9 in a human GC cell line, and found a drastic decrease in the invasive ability of malignant cells. This finding suggests the critical role of S100A8 and S100A9 and their heterodimer in promoting progression and invasion in GC. Novel evidence has also shown a significant increase in MDSC-induced S100A8/A9 plasma levels in GC patients, which is thought to induce immunosuppressive effects through RAGE-dependent T-cell proliferation and interferon-γ production, which directly correlate with advanced cancer stage and reduced survival[119].

Interestingly, the emerging role of calprotectin as a modulator of apoptosis has been recently reported. Calprotectin has been shown to be involved in the regulation of apoptotic mediators such as Bax, Bcl-2 family proteins, and ERK signaling pathway proteins through RAGE engagement in GC cell lines[120].

Dissemination and metastasis

The dissemination of malignant cells from their primary site and the subsequent development of secondary tumors in distant organs, a process called metastasis, is a main consequence of cancer therapy failure and a major cause of cancer-related mortality[1,14]. The complex process of metastasis is supported by different mechanisms that require primary tumor cells to leave their origin, circulate within the microvasculature, escape immune surveillance, and colonize distant niches to promote the formation of secondary tumors[121].

A pivotal step in the development of secondary metastasis is the establishment of a complex interplay of tumor-derived factors, a favorable microenvironment in the distant site (i.e. a “pre-metastatic niche”). The pre-metastatic niche favors tumor cell colonization and promotes micro- and macrometastasis. Processes that contribute to the cultivation of the niche include inflammation, immunosuppression, neoangiogenesis, lymphangiogenesis, and organotropism[122].

Strikingly, the niche-promoting molecules described in various malignancies, including GC, are closely regulated by RAGE axis activation[71]. Examples of niche-promoting factors include S100A8/A9 ligand[39,123], VEGF-A, TNF-α, TGF-β, MMPs[43,46,124], extracellular vesicles, exosomes, and various microRNAs[5,7]; these mediators sculpt the cellular crosstalk that allows the initiation of metastatic secondary tumor formation[125,126]. In GC, it has been documented that patients with advanced stage and distant dissemination have a poor prognosis with a 5-year survival of approximately 20% depending on the population analyzed, tumor histological features, and the antineoplastic therapy used[1-3].

Experimental results suggest that RAGE overexpression is closely associated with the disruption of cell-to-cell adhesion and acceleration of GC cell motility, both of which support the metastatic activity of GC cells[93]. To this end, RAGE knockdown reduces GC cell proliferation and invasion and decreases the expression of pro-tumoral mediators (e.g., Akt, PCNA, and MMP-2) consequently inducing aberrant cell apoptosis and cell cycle arrest[112]. For example, in vivo and in vitro evidence has shown that AGE binding to RAGE can accelerate gastric tumor progression and dissemination through the dose-dependent upregulation of the pro-tumoral mediators Specificity Protein 1 and MMP-2 via activation of ERK signaling[126,127].

In addition to its actions discussed above, HMGB1 also facilitates the progression and metastasis of various types of cancer[128], including GC[105,107]. In recent years, a growing body of evidence has begun to unravel the molecular mechanisms behind this contribution HMGB1 to CG metastasis[106]. For example, several studies have revealed increased expression of RAGE and HMGB1 in gastric tumor samples, which correlates with local and distant advanced disease and poor overall prognosis[102,107,109,110,113]. This association is accentuated under hyperglycemic conditions such as in diabetes mellitus, which enhance endogenous AGE formation and RAGE signaling[105]. Furthermore, other experimental research has shown that the overexpression of HMGB1 and the subsequent induction of IL-8 in the gastric tumor microenvironment (TME) may contribute to EMT and GC micrometastasis through the activation of downstream pathways of the RAGE axis, including ERK 1/2 and NF-ҡB[110]. In addition, overexpression of HMGB1 promotes the recruitment of neutrophils to the TME; this inflammation and associated production of ROS further promotes GC proliferation and metastasis[128,129].

Another recent investigation has demonstrated that the HMGB1/RAGE axis can regulate GC cell proliferation and migration via the enhanced expression of cyclins and MMPs, the induction of EMT, and activation of several cellular proliferation pathways including the Akt/mTOR and ERK/CREB signaling pathways[77].

Moreover, the in vivo or in vitro knockdown of HMGB1 leads to downregulation of NF-ҡB, PCNA, and MMP-9 expression in gastric tumor cells. This finding suggests that targeting the HMGB1 pathway may be a promising approach to inhibit the growth and metastasis of GC cells through the regulation of RAGE-dependent pathways[113]. Also, the overexpression of HMGB1 has been shown to enhance gastric tumor cell secretion of IL-8, supporting EMT during the early stages of tumor progression. Conversely, reduction in HMGB1/RAGE signaling by in vivo targeting of extracellular HMGB1 produces a significant reduction in tumor growth[111].

The overexpression of calgranulins in invasive GC cell lines has also been demonstrated[116]. These recognized RAGE ligands can promote not only more invasive phenotypes of the malignant cells, but can also enhance their migration capacity via RAGE-dependent mechanisms (e.g., p38 MAPK-dependent NF-ҡB activation and MMP2 upregulation)[117].

RAGE polymorphisms

The expression level of RAGE has been associated with invasion, metastasis, and poor prognosis in GC[93,94]. RAGE levels also correlate with the severity of gastric mucosal lesions in patients infected with H. pylori, where the highest RAGE expression was observed in precancerous lesions (e.g., atrophy or IM), dysplastic lesions, or in situ adenocarcinoma[130].

Compelling data have identified diverse polymorphisms within exons, introns, and regulatory regions of the gene encoding RAGE[131]. Interestingly, some of these polymorphisms may affect either RAGE gene transcriptional activity or the binding affinity of RAGE for its ligands[55,132]. Thus, RAGE polymorphisms are now potentially considered as susceptibility or poor prognostic factors in different cancer types. In this regard, several research groups have investigated the association between RAGE gene polymorphisms and the risk of various cancers[133-137]. For example, studies have demonstrated the association of certain RAGE polymorphisms and GC. The pioneering work of Wang et al[136] demonstrated that the rs2070600 RAGE polymorphism [Gly82Ser] confers an increased risk of GC in the Chinese population[138]. Of note, this polymorphism is associated with enhanced RAGE signaling[132].

More recently, Liu et al[125] further confirmed that the rs2070600 variant AG genotype plays a predominant role in the development of GC. On the contrary, the rs184003 GT genotype represents a significantly reduced risk for GC. Additionally, the rs2070600 and rs184003 polymorphisms affect the serum levels of the splice variant of sRAGE, where the first is associated with a decreased level of while the latter with an increased serum level of sRAGE[139].

In addition to the protease-mediated cleavage soluble RAGE variants, sRAGE can arise from alternative splicing of the RAGE gene. These soluble variants lack the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains, allowing them to function as decoy receptors, that do not lead to the activation of RAGE-associated signaling[46]. Reduced sRAGE has been associated with increased cancer risk and tumor progression in many other cancer types[140,141].

In summary, a diverse and compelling body of data shows the wide range of mechanistic contributions of the RAGE axis to gastric carcinogenesis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Main contributions of the receptor for advanced glycation end products axis to gastric carcinogenesis

|

Mechanism

|

Impact in gastric carcinogenesis

|

Year of publication

|

Ref.

|

| RAGE overexpression | Promote tumor growth, migration and highly invasive phenotypes | 2002 | Kuniyasu et al[93] |

| Association with high invasive histopathological grade, and poor overall survival | 2015 | Wang et al[94] | |

| RAGE polymorphisms | |||

| rs2070600 | Association with increased risk of GC and highly invasive features | 2008 | Gu et al[138] |

| Association with increased risk of GC | 2017 | Li et al[139] | |

| rs184003 | Association with decrease risk of GC | 2017 | Li et al[139] |

| RAGE activation | |||

| HMGB1 | Association with advance pT stage | 2021 | Zhou and Yang[74] |

| Promotes GC cell proliferation and migration | 2021 | Tang et al[77] | |

| Support cancer cell survival and chemoresistance | 2015 | Zhang et al[86] | |

| Association to higher TNM stage, lymph node metastasis, and depth of invasion | 2021 | Zhou et al[105] | |

| Increased macrophage infiltration | 2007 | Akaike et al[103] | |

| Enhance tumor angiogenesis through induction of IL-8 | 2017 | Chung et al[110] | |

| Promotes EMT activation and increased cell motility/invasiveness | 2015 | Chung et al[111] | |

| Promote GC progression via EMT | 2020 | Jin et al[104] | |

| AGEs | Upregulation of pro-tumoral mediators | 2017 | Deng et al[127] |

| S100 proteins | Enhance tumor cell proliferation and migration | 2021 | You et al[80] |

| Induced migration and invasion in GC cells | 2013 | Kwon et al[117] | |

| Promoting progression and invasion in GC cells | 2007 | Yong and Moon[118] | |

| Immunosuppressive RAGE-mediated effects | 2013 | Wang et al[119] | |

| Dysregulation of apoptotic factors | 2020 | Shabani et al[120] |

AGE: Advanced glycation end products; EMT: Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition; GC: Gastric cancer; HMGB1: High mobility group box 1; IL: Interleukin; RAGE: Receptor for advanced glycation end products.

CONCLUSION

The RAGE axis is emerging as a relevant actor in gastric carcinogenesis. In this regard, a high expression level of RAGE and many RAGE ligands has been associated with tumor cell growth, invasion, metastasis, and poor prognosis. Furthermore, polymorphisms in the gene encoding RAGE have been linked to strengthening of RAGE ligand affinity, enhanced intracellular signaling, and modulation of the serum levels of the soluble form of the receptor (sRAGE), which have been postulated as potential biomarkers of poor prognosis in GC patients.

However, additional research efforts are needed to fully understand the role of RAGE signaling in gastric carcinogenesis, particularly in those populations with a high prevalence of GC. Of note, increasing focus is being placed on diet and lifestyle modification as potential methods for preventing GC. This is particularly interesting, considering that in modern society, the consumption of AGEs is markedly increased (due in part to increased consumption of modern Westernized diets). Dietary intervention to restrict the intake of AGEs is recognized as a useful intervention, as demonstrated in several pathologies[10,11].

Today, clinical and experimental data demonstrate the therapeutic potential of blocking activation of the RAGE axis, as demonstrated by gene-silencing technologies, the use of aptamers, and the use of natural and synthetic molecules, all of which decrease RAGE ligand binding and/or RAGE-dependent intracellular signaling[51,70]. However, more clinical research is needed to establish the effectiveness of these promising options.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors report having no relevant conflicts of interest for this article.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: October 21, 2022

First decision: November 14, 2022

Article in press: January 11, 2023

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Chile

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kanaoujiya R, India; Kong M, China S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Fan JR

Contributor Information

Armando Rojas, Biomedical Research Laboratories, Medicine Faculty, Catholic University of Maule, Talca 34600000, Chile. arojasr@ucm.cl.

Cristian Lindner, Medicine Faculty, Catholic University of Maule, Talca 34600000, Chile.

Iván Schneider, Medicine Faculty, Catholic University of Maule, Talca 34600000, Chile.

Ileana González, Biomedical Research Laboratories, Medicine Faculty, Catholic University of Maule, Talca 34600000, Chile.

Miguel Angel Morales, Molecular and Clinical Pharmacology Program, Institute of Biomedical Sciences, University of Chile, Santiago 8320000, Chile.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ilic M, Ilic I. Epidemiology of stomach cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28:1187–1203. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v28.i12.1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thrift AP, El-Serag HB. Burden of Gastric Cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:534–542. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Astudillo P. Wnt5a Signaling in Gastric Cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:110. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.00110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rojas A, Araya P, Gonzalez I, Morales E. Gastric Tumor Microenvironment. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1226:23–35. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-36214-0_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li N, Zeng A, Wang Q, Chen M, Zhu S, Song L. Regulatory function of DNA methylation mediated lncRNAs in gastric cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2022;22:227. doi: 10.1186/s12935-022-02648-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bin YL, Hu HS, Tian F, Wen ZH, Yang MF, Wu BH, Wang LS, Yao J, Li DF. Metabolic Reprogramming in Gastric Cancer: Trojan Horse Effect. Front Oncol. 2021;11:745209. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.745209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wen J, Lau HC, Peppelenbosch M, Yu J. Gastric Microbiota beyond H. pylori: An Emerging Critical Character in Gastric Carcinogenesis. Biomedicines. 2021;9 doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9111680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muthyalaiah YS, Jonnalagadda B, John CM, Arockiasamy S. Impact of Advanced Glycation End products (AGEs) and its receptor (RAGE) on cancer metabolic signaling pathways and its progression. Glycoconj J. 2021;38:717–734. doi: 10.1007/s10719-021-10031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palanissami G, Paul SFD. RAGE and Its Ligands: Molecular Interplay Between Glycation, Inflammation, and Hallmarks of Cancer-a Review. Horm Cancer. 2018;9:295–325. doi: 10.1007/s12672-018-0342-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahmad S, Khan H, Siddiqui Z, Khan MY, Rehman S, Shahab U, Godovikova T, Silnikov V, Moinuddin AGEs, RAGEs and s-RAGE; friend or foe for cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2018;49:44–55. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rojas A, Figueroa H, Morales E. Fueling inflammation at tumor microenvironment: the role of multiligand/RAGE axis. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:334–341. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eusebi LH, Telese A, Marasco G, Bazzoli F, Zagari RM. Gastric cancer prevention strategies: A global perspective. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;35:1495–1502. doi: 10.1111/jgh.15037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arnold M, Rutherford MJ, Bardot A, Ferlay J, Andersson TM, Myklebust TÅ, Tervonen H, Thursfield V, Ransom D, Shack L, Woods RR, Turner D, Leonfellner S, Ryan S, Saint-Jacques N, De P, McClure C, Ramanakumar AV, Stuart-Panko H, Engholm G, Walsh PM, Jackson C, Vernon S, Morgan E, Gavin A, Morrison DS, Huws DW, Porter G, Butler J, Bryant H, Currow DC, Hiom S, Parkin DM, Sasieni P, Lambert PC, Møller B, Soerjomataram I, Bray F. Progress in cancer survival, mortality, and incidence in seven high-income countries 1995-2014 (ICBP SURVMARK-2): a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:1493–1505. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30456-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morgan E, Arnold M, Camargo MC, Gini A, Kunzmann AT, Matsuda T, Meheus F, Verhoeven RHA, Vignat J, Laversanne M, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I. The current and future incidence and mortality of gastric cancer in 185 countries, 2020-40: A population-based modelling study. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;47:101404. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Correa P. Human gastric carcinogenesis: a multistep and multifactorial process--First American Cancer Society Award Lecture on Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6735–6740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang L, Kartsonaki C, Yao P, de Martel C, Plummer M, Chapman D, Guo Y, Clark S, Walters RG, Chen Y, Pei P, Lv J, Yu C, Jeske R, Waterboer T, Clifford GM, Franceschi S, Peto R, Hill M, Li L, Millwood IY, Chen Z China Kadoorie Biobank Collaborative Group. The relative and attributable risks of cardia and non-cardia gastric cancer associated with Helicobacter pylori infection in China: a case-cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6:e888–e896. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00164-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hooi JKY, Lai WY, Ng WK, Suen MMY, Underwood FE, Tanyingoh D, Malfertheiner P, Graham DY, Wong VWS, Wu JCY, Chan FKL, Sung JJY, Kaplan GG, Ng SC. Global Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:420–429. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, Matsumura N, Yamaguchi S, Yamakido M, Taniyama K, Sasaki N, Schlemper RJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa001999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar S, Patel GK, Ghoshal UC. Helicobacter pylori-Induced Inflammation: Possible Factors Modulating the Risk of Gastric Cancer. Pathogens. 2021;10 doi: 10.3390/pathogens10091099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet. 2001;357:539–545. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao W, Liu M, Zhang M, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Wang S, Zhang N. Effects of Inflammation on the Immune Microenvironment in Gastric Cancer. Front Oncol. 2021;11:690298. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.690298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sfanos KS, Yegnasubramanian S, Nelson WG, De Marzo AM. The inflammatory microenvironment and microbiome in prostate cancer development. Nat Rev Urol. 2018;15:11–24. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2017.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mishra SK, Kumari N, Krishnani N. Molecular pathogenesis of gallbladder cancer: An update. Mutat Res. 2019;816-818:111674. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2019.111674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han D, Zhang C. The Oxidative Damage and Inflammation Mechanisms in GERD-Induced Barrett's Esophagus. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022;10:885537. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2022.885537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tu T, Bühler S, Bartenschlager R. Chronic viral hepatitis and its association with liver cancer. Biol Chem. 2017;398:817–837. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2017-0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Balkwill FR, Mantovani A. Cancer-related inflammation: common themes and therapeutic opportunities. Semin Cancer Biol. 2012;22:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schistosomes, liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 1994;61:1–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lamb A, Yang XD, Tsang YH, Li JD, Higashi H, Hatakeyama M, Peek RM, Blanke SR, Chen LF. Helicobacter pylori CagA activates NF-kappaB by targeting TAK1 for TRAF6-mediated Lys 63 ubiquitination. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:1242–1249. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Backert S, Naumann M. What a disorder: proinflammatory signaling pathways induced by Helicobacter pylori. Trends Microbiol. 2010;18:479–486. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang F, Meng W, Wang B, Qiao L. Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric inflammation and gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 2014;345:196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bravo D, Hoare A, Soto C, Valenzuela MA, Quest AF. Helicobacter pylori in human health and disease: Mechanisms for local gastric and systemic effects. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:3071–3089. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i28.3071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Janeway CA Jr. Approaching the asymptote? Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1989;54 Pt 1:1–13. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1989.054.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang D, Han Z, Oppenheim JJ. Alarmins and immunity. Immunol Rev. 2017;280:41–56. doi: 10.1111/imr.12577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bianchi ME. DAMPs, PAMPs and alarmins: all we need to know about danger. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:1–5. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0306164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gonzalez I, Araya P, Schneider I, Lindner C, Rojas A. Pattern recognition receptors and their roles in the host response to Helicobacter pylori infection. Future Microbiol. 2021;16:1229–1238. doi: 10.2217/fmb-2021-0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldin A, Beckman JA, Schmidt AM, Creager MA. Advanced glycation end products: sparking the development of diabetic vascular injury. Circulation. 2006;114:597–605. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.621854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rouhiainen A, Kuja-Panula J, Tumova S, Rauvala H. RAGE-mediated cell signaling. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;963:239–263. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-230-8_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leclerc E, Fritz G, Vetter SW, Heizmann CW. Binding of S100 proteins to RAGE: an update. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793:993–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koch M, Chitayat S, Dattilo BM, Schiefner A, Diez J, Chazin WJ, Fritz G. Structural basis for ligand recognition and activation of RAGE. Structure. 2010;18:1342–1352. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fritz G. RAGE: a single receptor fits multiple ligands. Trends Biochem Sci. 2011;36:625–632. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singh H, Agrawal DK. Therapeutic potential of targeting the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) by small molecule inhibitors. Drug Dev Res. 2022;83:1257–1269. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dong H, Zhang Y, Huang Y, Deng H. Pathophysiology of RAGE in inflammatory diseases. Front Immunol. 2022;13:931473. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.931473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hudson BI, Kalea AZ, Del Mar Arriero M, Harja E, Boulanger E, D'Agati V, Schmidt AM. Interaction of the RAGE cytoplasmic domain with diaphanous-1 is required for ligand-stimulated cellular migration through activation of Rac1 and Cdc42. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:34457–34468. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801465200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rojas A, Delgado-López F, González I, Pérez-Castro R, Romero J, Rojas I. The receptor for advanced glycation end-products: a complex signaling scenario for a promiscuous receptor. Cell Signal. 2013;25:609–614. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Santilli F, Vazzana N, Bucciarelli LG, Davì G. Soluble forms of RAGE in human diseases: clinical and therapeutical implications. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16:940–952. doi: 10.2174/092986709787581888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yan SF, Ramasamy R, Schmidt AM. Soluble RAGE: therapy and biomarker in unraveling the RAGE axis in chronic disease and aging. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;79:1379–1386. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang L, Bukulin M, Kojro E, Roth A, Metz VV, Fahrenholz F, Nawroth PP, Bierhaus A, Postina R. Receptor for advanced glycation end products is subjected to protein ectodomain shedding by metalloproteinases. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:35507–35516. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806948200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kang R, Hou W, Zhang Q, Chen R, Lee YJ, Bartlett DL, Lotze MT, Tang D, Zeh HJ. RAGE is essential for oncogenic KRAS-mediated hypoxic signaling in pancreatic cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1480. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rojas A, Morales M, Gonzalez I, Araya P. Inhibition of RAGE Axis Signaling: A Pharmacological Challenge. Curr Drug Targets. 2019;20:340–346. doi: 10.2174/1389450119666180820105956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bierhaus A, Humpert PM, Morcos M, Wendt T, Chavakis T, Arnold B, Stern DM, Nawroth PP. Understanding RAGE, the receptor for advanced glycation end products. J Mol Med (Berl) 2005;83:876–886. doi: 10.1007/s00109-005-0688-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Slowik A, Merres J, Elfgen A, Jansen S, Mohr F, Wruck CJ, Pufe T, Brandenburg LO. Involvement of formyl peptide receptors in receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE)--and amyloid beta 1-42-induced signal transduction in glial cells. Mol Neurodegener. 2012;7:55. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-7-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sakaguchi M, Murata H, Yamamoto K, Ono T, Sakaguchi Y, Motoyama A, Hibino T, Kataoka K, Huh NH. TIRAP, an adaptor protein for TLR2/4, transduces a signal from RAGE phosphorylated upon ligand binding. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23132. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Serveaux-Dancer M, Jabaudon M, Creveaux I, Belville C, Blondonnet R, Gross C, Constantin JM, Blanchon L, Sapin V. Pathological Implications of Receptor for Advanced Glycation End-Product (AGER) Gene Polymorphism. Dis Markers. 2019;2019:2067353. doi: 10.1155/2019/2067353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Teissier T, Boulanger É. The receptor for advanced glycation end-products (RAGE) is an important pattern recognition receptor (PRR) for inflammaging. Biogerontology. 2019;20:279–301. doi: 10.1007/s10522-019-09808-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xie J, Reverdatto S, Frolov A, Hoffmann R, Burz DS, Shekhtman A. Structural basis for pattern recognition by the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) J Biol Chem. 2008;283:27255–27269. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801622200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lin L. RAGE on the Toll Road? Cell Mol Immunol. 2006;3:351–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.González I, Romero J, Rodríguez BL, Pérez-Castro R, Rojas A. The immunobiology of the receptor of advanced glycation end-products: trends and challenges. Immunobiology. 2013;218:790–797. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ibrahim ZA, Armour CL, Phipps S, Sukkar MB. RAGE and TLRs: relatives, friends or neighbours? Mol Immunol. 2013;56:739–744. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2013.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hudson BI, Lippman ME. Targeting RAGE Signaling in Inflammatory Disease. Annu Rev Med. 2018;69:349–364. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-041316-085215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van Zoelen MA, Achouiti A, van der Poll T. RAGE during infectious diseases. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 2011;3:1119–1132. doi: 10.2741/215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arce-Mendoza A, Rodriguez-de Ita J, Salinas-Carmona MC, Rosas-Taraco AG. Expression of CD64, CD206, and RAGE in adherent cells of diabetic patients infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Arch Med Res. 2008;39:306–311. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2007.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rojas A, González I, Rodríguez B, Romero J, Figueroa H, Llanos J, Morales E, Pérez-Castro R. Evidence of involvement of the receptor for advanced glycation end-products (RAGE) in the adhesion of Helicobacter pylori to gastric epithelial cells. Microbes Infect. 2011;13:818–823. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Su B, Ceponis PJ, Lebel S, Huynh H, Sherman PM. Helicobacter pylori activates Toll-like receptor 4 expression in gastrointestinal epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2003;71:3496–3502. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3496-3502.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gąsiorowski K, Brokos B, Echeverria V, Barreto GE, Leszek J. RAGE-TLR Crosstalk Sustains Chronic Inflammation in Neurodegeneration. Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55:1463–1476. doi: 10.1007/s12035-017-0419-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Taguchi A, Blood DC, del Toro G, Canet A, Lee DC, Qu W, Tanji N, Lu Y, Lalla E, Fu C, Hofmann MA, Kislinger T, Ingram M, Lu A, Tanaka H, Hori O, Ogawa S, Stern DM, Schmidt AM. Blockade of RAGE-amphoterin signalling suppresses tumour growth and metastases. Nature. 2000;405:354–360. doi: 10.1038/35012626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sims GP, Rowe DC, Rietdijk ST, Herbst R, Coyle AJ. HMGB1 and RAGE in inflammation and cancer. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:367–388. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sparvero LJ, Asafu-Adjei D, Kang R, Tang D, Amin N, Im J, Rutledge R, Lin B, Amoscato AA, Zeh HJ, Lotze MT. RAGE (Receptor for Advanced Glycation End products), RAGE ligands, and their role in cancer and inflammation. J Transl Med. 2009;7:17. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-7-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.El-Far AH, Sroga G, Jaouni SKA, Mousa SA. Role and Mechanisms of RAGE-Ligand Complexes and RAGE-Inhibitors in Cancer Progression. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21 doi: 10.3390/ijms21103613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Waghela BN, Vaidya FU, Ranjan K, Chhipa AS, Tiwari BS, Pathak C. AGE-RAGE synergy influences programmed cell death signaling to promote cancer. Mol Cell Biochem. 2021;476:585–598. doi: 10.1007/s11010-020-03928-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rojas A, Schneider I, Lindner C, Gonzalez I, Morales MA. The RAGE/multiligand axis: a new actor in tumor biology. Biosci Rep. 2022;42 doi: 10.1042/BSR20220395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kim HJ, Jeong MS, Jang SB. Molecular Characteristics of RAGE and Advances in Small-Molecule Inhibitors. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22 doi: 10.3390/ijms22136904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhou C, Yang Q. Value of HMGB1 expression for assessing gastric cancer severity: a systematic meta-analysis. J Int Med Res. 2021;49:300060521993312. doi: 10.1177/0300060521993312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Amornsupak K, Thongchot S, Thinyakul C, Box C, Hedayat S, Thuwajit P, Eccles SA, Thuwajit C. HMGB1 mediates invasion and PD-L1 expression through RAGE-PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2022;22:578. doi: 10.1186/s12885-022-09675-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kang R, Tang D, Schapiro NE, Loux T, Livesey KM, Billiar TR, Wang H, Van Houten B, Lotze MT, Zeh HJ. The HMGB1/RAGE inflammatory pathway promotes pancreatic tumor growth by regulating mitochondrial bioenergetics. Oncogene. 2014;33:567–577. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tang T, Wang S, Cai T, Cheng Z, Meng Y, Qi S, Zhang Y, Qi Z. High mobility group box 1 regulates gastric cancer cell proliferation and migration via RAGE-mTOR/ERK feedback loop. J Cancer. 2021;12:518–529. doi: 10.7150/jca.51049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ou S, Liao Y, Shi J, Tang J, Ye Y, Wu F, Wang W, Fei J, Xie F, Bai L. S100A16 suppresses the proliferation, migration and invasion of colorectal cancer cells in part via the JNK/p38 MAPK pathway. Mol Med Rep. 2021;23 doi: 10.3892/mmr.2020.11803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Leclerc E, Vetter SW. The role of S100 proteins and their receptor RAGE in pancreatic cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1852:2706–2711. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.You X, Li M, Cai H, Zhang W, Hong Y, Gao W, Liu Y, Liang X, Wu T, Chen F, Su D. Calcium Binding Protein S100A16 Expedites Proliferation, Invasion and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition Process in Gastric Cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:736929. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.736929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Das G, Shravage BV, Baehrecke EH. Regulation and function of autophagy during cell survival and cell death. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a008813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cerda-Troncoso C, Varas-Godoy M, Burgos PV. Pro-Tumoral Functions of Autophagy Receptors in the Modulation of Cancer Progression. Front Oncol. 2020;10:619727. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.619727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mulcahy Levy JM, Thorburn A. Autophagy in cancer: moving from understanding mechanism to improving therapy responses in patients. Cell Death Differ. 2020;27:843–857. doi: 10.1038/s41418-019-0474-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Galluzzi L, Pietrocola F, Bravo-San Pedro JM, Amaravadi RK, Baehrecke EH, Cecconi F, Codogno P, Debnath J, Gewirtz DA, Karantza V, Kimmelman A, Kumar S, Levine B, Maiuri MC, Martin SJ, Penninger J, Piacentini M, Rubinsztein DC, Simon HU, Simonsen A, Thorburn AM, Velasco G, Ryan KM, Kroemer G. Autophagy in malignant transformation and cancer progression. EMBO J. 2015;34:856–880. doi: 10.15252/embj.201490784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Qian HR, Yang Y. Functional role of autophagy in gastric cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:17641–17651. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhang QY, Wu LQ, Zhang T, Han YF, Lin X. Autophagy-mediated HMGB1 release promotes gastric cancer cell survival via RAGE activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2. Oncol Rep. 2015;33:1630–1638. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.3782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Xu JL, Yuan L, Tang YC, Xu ZY, Xu HD, Cheng XD, Qin JJ. The Role of Autophagy in Gastric Cancer Chemoresistance: Friend or Foe? Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:621428. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.621428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gebhardt C, Riehl A, Durchdewald M, Németh J, Fürstenberger G, Müller-Decker K, Enk A, Arnold B, Bierhaus A, Nawroth PP, Hess J, Angel P. RAGE signaling sustains inflammation and promotes tumor development. J Exp Med. 2008;205:275–285. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Heijmans J, Büller NV, Hoff E, Dihal AA, van der Poll T, van Zoelen MA, Bierhaus A, Biemond I, Hardwick JC, Hommes DW, Muncan V, van den Brink GR. Rage signalling promotes intestinal tumourigenesis. Oncogene. 2013;32:1202–1206. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nankali M, Karimi J, Goodarzi MT, Saidijam M, Khodadadi I, Razavi AN, Rahimi F. Increased Expression of the Receptor for Advanced Glycation End-Products (RAGE) Is Associated with Advanced Breast Cancer Stage. Oncol Res Treat. 2016;39:622–628. doi: 10.1159/000449326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ishiguro H, Nakaigawa N, Miyoshi Y, Fujinami K, Kubota Y, Uemura H. Receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) and its ligand, amphoterin are overexpressed and associated with prostate cancer development. Prostate. 2005;64:92–100. doi: 10.1002/pros.20219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zill H, Günther R, Erbersdobler HF, Fölsch UR, Faist V. RAGE expression and AGE-induced MAP kinase activation in Caco-2 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;288:1108–1111. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kuniyasu H, Oue N, Wakikawa A, Shigeishi H, Matsutani N, Kuraoka K, Ito R, Yokozaki H, Yasui W. Expression of receptors for advanced glycation end-products (RAGE) is closely associated with the invasive and metastatic activity of gastric cancer. J Pathol. 2002;196:163–170. doi: 10.1002/path.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wang D, Li T, Ye G, Shen Z, Hu Y, Mou T, Yu J, Li S, Liu H, Li G. Overexpression of the Receptor for Advanced Glycation End products (RAGE) is associated with poor prognosis in gastric cancer. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0122697. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lamouille S, Xu J, Derynck R. Molecular mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:178–196. doi: 10.1038/nrm3758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Jayachandran J, Srinivasan H, Mani KP. Molecular mechanism involved in epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2021;710:108984. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2021.108984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Dongre A, Weinberg RA. New insights into the mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and implications for cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20:69–84. doi: 10.1038/s41580-018-0080-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zhao L, Li W, Zang W, Liu Z, Xu X, Yu H, Yang Q, Jia J. JMJD2B promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition by cooperating with β-catenin and enhances gastric cancer metastasis. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:6419–6429. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Peng Z, Wang CX, Fang EH, Wang GB, Tong Q. Role of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in gastric cancer initiation and progression. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:5403–5410. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i18.5403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wu T, Zhang W, Yang G, Li H, Chen Q, Song R, Zhao L. HMGB1 overexpression as a prognostic factor for survival in cancer: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Oncotarget. 2016;7:50417–50427. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bresnick AR, Weber DJ, Zimmer DB. S100 proteins in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15:96–109. doi: 10.1038/nrc3893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Xiang YY, Wang DY, Tanaka M, Suzuki M, Kiyokawa E, Igarashi H, Naito Y, Shen Q, Sugimura H. Expression of high-mobility group-1 mRNA in human gastrointestinal adenocarcinoma and corresponding non-cancerous mucosa. Int J Cancer. 1997;74:1–6. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970220)74:1<1::aid-ijc1>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Akaike H, Kono K, Sugai H, Takahashi A, Mimura K, Kawaguchi Y, Fujii H. Expression of high mobility group box chromosomal protein-1 (HMGB-1) in gastric cancer. Anticancer Res. 2007;27:449–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Jin GH, Shi Y, Tian Y, Cao TT, Mao Y, Tang TY. HMGA1 accelerates the malignant progression of gastric cancer through stimulating EMT. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24:3642–3647. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202004_20826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zhou Y, Liu SX, Zhou YN, Wang J, Ji R. Research on the relationship between RAGE and its ligand HMGB1, and prognosis and pathogenesis of gastric cancer with diabetes mellitus. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021;25:1339–1350. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202102_24841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kishi S, Nishiguchi Y, Honoki K, Mori S, Fujiwara-Tani R, Sasaki T, Fujii K, Kawahara I, Goto K, Nakashima C, Kido A, Tanaka Y, Luo Y, Kuniyasu H. Role of Glycated High Mobility Group Box-1 in Gastric Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22 doi: 10.3390/ijms22105185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hu D, Lin XD, Shen WC, Zhu WF, Zhang HJ, Xia Y, Liu W, Chen G, Zheng XW. [Expression of HMGB1 and RAGE protein in gastric cancer and its prognostic significance] Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2018;47:542–543. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0529-5807.2018.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Fang J, Ge X, Xu W, Xie J, Qin Z, Shi L, Yin W, Bian M, Wang H. Bioinformatics analysis of the prognosis and biological significance of HMGB1, HMGB2, and HMGB3 in gastric cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235:3438–3446. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Chang HP, Sun JT, Cheng CY, Liang YJ, Chen YL. High Mobility Group A 1 Expression as a Poor Prognostic Marker Associated with Tumor Invasiveness in Gastric Cancer. Life (Basel) 2022;12 doi: 10.3390/life12050709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Chung HW, Lim JB. High-mobility group box-1 contributes tumor angiogenesis under interleukin-8 mediation during gastric cancer progression. Cancer Sci. 2017;108:1594–1601. doi: 10.1111/cas.13288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Chung HW, Jang S, Kim H, Lim JB. Combined targeting of high-mobility group box-1 and interleukin-8 to control micrometastasis potential in gastric cancer. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:1598–1609. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Xu XC, Abuduhadeer X, Zhang WB, Li T, Gao H, Wang YH. Knockdown of RAGE inhibits growth and invasion of gastric cancer cells. Eur J Histochem. 2013;57:e36. doi: 10.4081/ejh.2013.e36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zhang J, Kou YB, Zhu JS, Chen WX, Li S. Knockdown of HMGB1 inhibits growth and invasion of gastric cancer cells through the NF-κB pathway in vitro and in vivo. Int J Oncol. 2014;44:1268–1276. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2014.2285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Gebhardt C, Németh J, Angel P, Hess J. S100A8 and S100A9 in inflammation and cancer. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;72:1622–1631. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Allgöwer C, Kretz AL, von Karstedt S, Wittau M, Henne-Bruns D, Lemke J. Friend or Foe: S100 Proteins in Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12 doi: 10.3390/cancers12082037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.El-Rifai W, Moskaluk CA, Abdrabbo MK, Harper J, Yoshida C, Riggins GJ, Frierson HF Jr, Powell SM. Gastric cancers overexpress S100A calcium-binding proteins. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6823–6826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kwon CH, Moon HJ, Park HJ, Choi JH, Park DY. S100A8 and S100A9 promotes invasion and migration through p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent NF-κB activation in gastric cancer cells. Mol Cells. 2013;35:226–234. doi: 10.1007/s10059-013-2269-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Yong HY, Moon A. Roles of calcium-binding proteins, S100A8 and S100A9, in invasive phenotype of human gastric cancer cells. Arch Pharm Res. 2007;30:75–81. doi: 10.1007/BF02977781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Wang L, Chang EW, Wong SC, Ong SM, Chong DQ, Ling KL. Increased myeloid-derived suppressor cells in gastric cancer correlate with cancer stage and plasma S100A8/A9 proinflammatory proteins. J Immunol. 2013;190:794–804. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Shabani F, Mahdavi M, Imani M, Hosseinpour-Feizi MA, Gheibi N. Calprotectin (S100A8/S100A9)-induced cytotoxicity and apoptosis in human gastric cancer AGS cells: Alteration in expression levels of Bax, Bcl-2, and ERK2. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2020;39:1031–1045. doi: 10.1177/0960327120909530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Fares J, Fares MY, Khachfe HH, Salhab HA, Fares Y. Molecular principles of metastasis: a hallmark of cancer revisited. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5:28. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-0134-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Peinado H, Zhang H, Matei IR, Costa-Silva B, Hoshino A, Rodrigues G, Psaila B, Kaplan RN, Bromberg JF, Kang Y, Bissell MJ, Cox TR, Giaccia AJ, Erler JT, Hiratsuka S, Ghajar CM, Lyden D. Pre-metastatic niches: organ-specific homes for metastases. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17:302–317. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Hiratsuka S, Watanabe A, Sakurai Y, Akashi-Takamura S, Ishibashi S, Miyake K, Shibuya M, Akira S, Aburatani H, Maru Y. The S100A8-serum amyloid A3-TLR4 paracrine cascade establishes a pre-metastatic phase. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1349–1355. doi: 10.1038/ncb1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Kaplan RN, Riba RD, Zacharoulis S, Bramley AH, Vincent L, Costa C, MacDonald DD, Jin DK, Shido K, Kerns SA, Zhu Z, Hicklin D, Wu Y, Port JL, Altorki N, Port ER, Ruggero D, Shmelkov SV, Jensen KK, Rafii S, Lyden D. VEGFR1-positive haematopoietic bone marrow progenitors initiate the pre-metastatic niche. Nature. 2005;438:820–827. doi: 10.1038/nature04186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Liu Y, Cao X. Characteristics and Significance of the Pre-metastatic Niche. Cancer Cell. 2016;30:668–681. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Zhong J, Chen Y, Wang LJ. Emerging molecular basis of hematogenous metastasis in gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:2434–2440. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i8.2434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Deng R, Mo F, Chang B, Zhang Q, Ran H, Yang S, Zhu Z, Hu L, Su Q. Glucose-derived AGEs enhance human gastric cancer metastasis through RAGE/ERK/Sp1/MMP2 cascade. Oncotarget. 2017;8:104216–104226. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.22185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Tripathi A, Shrinet K, Kumar A. HMGB1 protein as a novel target for cancer. Toxicol Rep. 2019;6:253–261. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2019.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Abe A, Kuwata T, Yamauchi C, Higuchi Y, Ochiai A. High Mobility Group Box1 (HMGB1) released from cancer cells induces the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in peritoneal fibroblasts. Pathol Int. 2014;64:267–275. doi: 10.1111/pin.12167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Morales M E, Rojas R A, Monasterio A V, González B I, Figueroa C I, Manques M B, Romero E J, Llanos L J, Valdés M E, Cofré L C. [Expression of RAGE in Helicobacter pylori infested gastric biopsies] Rev Med Chil. 2013;141:1240–1248. doi: 10.4067/S0034-98872013001000002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Hudson BI, Carter AM, Harja E, Kalea AZ, Arriero M, Yang H, Grant PJ, Schmidt AM. Identification, classification, and expression of RAGE gene splice variants. FASEB J. 2008;22:1572–1580. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9909com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Hofmann MA, Drury S, Hudson BI, Gleason MR, Qu W, Lu Y, Lalla E, Chitnis S, Monteiro J, Stickland MH, Bucciarelli LG, Moser B, Moxley G, Itescu S, Grant PJ, Gregersen PK, Stern DM, Schmidt AM. RAGE and arthritis: the G82S polymorphism amplifies the inflammatory response. Genes Immun. 2002;3:123–135. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Chou YE, Hsieh MJ, Wang SS, Lin CY, Chen YY, Ho YC, Yang SF. The impact of receptor of advanced glycation end-products polymorphisms on prostate cancer progression and clinicopathological characteristics. J Cell Mol Med. 2021;25:10761–10769. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.17025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Xu Y, Lu Z, Shen N, Wang X. Association of RAGE rs1800625 Polymorphism and Cancer Risk: A Meta-Analysis of 18 Case-Control Studies. Med Sci Monit. 2019;25:7026–7034. doi: 10.12659/MSM.916260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Pan H, He L, Wang B, Niu W. The relationship between RAGE gene four common polymorphisms and breast cancer risk in northeastern Han Chinese. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4355. doi: 10.1038/srep04355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Wang X, Cui E, Zeng H, Hua F, Wang B, Mao W, Feng X. RAGE genetic polymorphisms are associated with risk, chemotherapy response and prognosis in patients with advanced NSCLC. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43734. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Zhang S, Hou X, Zi S, Wang Y, Chen L, Kong B. Polymorphisms of receptor for advanced glycation end products and risk of epithelial ovarian cancer in Chinese patients. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2013;31:525–531. doi: 10.1159/000350073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Gu H, Yang L, Sun Q, Zhou B, Tang N, Cong R, Zeng Y, Wang B. Gly82Ser polymorphism of the receptor for advanced glycation end products is associated with an increased risk of gastric cancer in a Chinese population. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3627–3632. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Li T, Qin W, Liu Y, Li S, Qin X, Liu Z. Effect of RAGE gene polymorphisms and circulating sRAGE levels on susceptibility to gastric cancer: a case-control study. Cancer Cell Int. 2017;17:19. doi: 10.1186/s12935-017-0391-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.He L, Bao H, Xue J, Zheng L, Zhang Q, Sun L, Pan H. Circulating soluble advanced glycation end product is inversely associated with the significant risk of developing cancer: evidence from a meta-analysis. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:8749–8755. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Huang Q, Mi J, Wang X, Liu F, Wang D, Yan D, Wang B, Zhang S, Tian G. Genetically lowered concentrations of circulating sRAGE might cause an increased risk of cancer: Meta-analysis using Mendelian randomization. J Int Med Res. 2016;44:179–191. doi: 10.1177/0300060515617869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]