Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the third leading cause of death worldwide, following strokes and cardiovascular diseases. Chronic lung inflammation is believed to play a role in the development of COPD. In addition, accumulating evidence shows that the immune system plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of COPD. Significant advancements have been made in research on the pathogenesis of immune diseases and chronic inflammation in recent years, and T helper 17 (Th17) cells and regulatory T (Treg) cells have been found to play a crucial role in the autoimmune response. Th17 cells are a proinflammatory subpopulation that causes autoimmune disease and tissue damage. Treg cells, on the other hand, have a negative effect but can contribute to the occurrence of the same disease when their antagonism fails. This review mainly summarizes the biological characteristics of Th17 cells and Treg cells, their roles in chronic inflammatory diseases of COPD, and the role of the Th17/Treg ratio in the onset, development, and outcome of inflammatory disorders, as well as recent advancements in immunomodulatory treatment targeting Th17/Treg cells in COPD.

Keywords: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, immune system, T helper cells, T‐regulatory cells

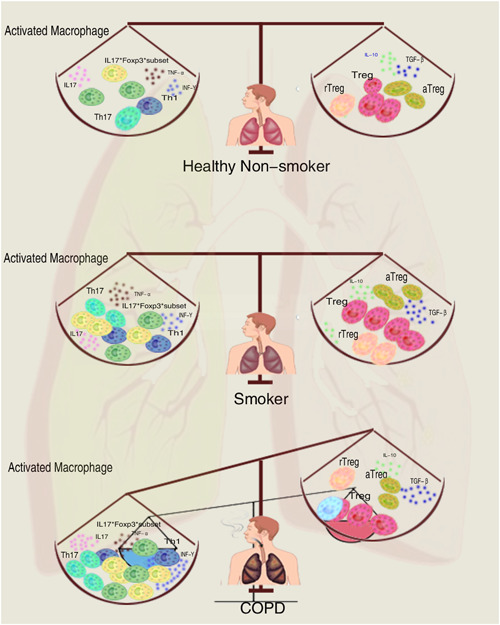

Disturbed immune homeostasis in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. There was an increase in the number and function of T helper 17 cells and their associated cytokines and, conversely, a decrease in the number and function of regulatory T cells and their associated cytokines.

1. INTRODUCTION

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is an inflammatory disease caused by airway and/or alveolar abnormalities that results in chronic airflow limitation and respiratory problems. 1 This irreversible airflow obstruction further results in high morbidity and mortality. 2 According to the World Health Organization, COPD will remain the third leading cause of mortality until 2030. 3 Additionally, the finding of genetic risk factors for various COPD subtypes implies that the condition is a spectrum with numerous forms, each with its own unique histopathological characteristics. 4 , 5 , 6 As a result, any incomplete combustion of organic matter, in combination with its own inherited susceptibility, initiates and propagates an immunological response, resulting in a variety of COPD‐related symptoms. 7

The immune system responds to environmental stimuli and strives to protect the host by killing rogue cells like cancer, neutralizing potential invaders like infections, and organizing tertiary immune structures in mucosal tissues like the airways. 8 , 9 , 10 T‐cell‐mediated adaptive immunity plays a significant role in controlling airway inflammation. 11 CD4+ T cells are divided into two subsets: T helper 17 (Th17) and regulatory T (Treg) cells, which differ in development and function. The maintenance of the balance of these cells is crucial for controlling the body's immune conditions, and an imbalance can cause systemic or local abnormal immune responses. In this article, we will concisely summarize the function of Th17 cells and Treg cells, as well as evidence of their involvement in the pathogenesis of COPD. We also anticipate their future application in COPD management.

2. TH17 CELLS

2.1. Overview of Th cells

Lung nesting CD4+ T lymphocytes distinguish secreted cytokines as Th1 (interleukin‐2 [IL‐2] and interferon‐γ [IFN‐γ] secretion), Th2 (IL‐4, IL‐5, and IL‐13 secretion), or Th17 (IL‐17a, IL‐17f, and IL‐22 secretion) subpopulations. 12 , 13 , 14

In animal experiments, Th17 cells have two different upstream signal transduction pathways due to their different differentiation sources. The first upstream pathway includes IL‐6 and transforming growth factor‐β (TGF‐β), both of which costimulate Th0 cells. The combination of IL‐6 and IL‐6R stimulates signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), and the combination of TGF‐β and TGF receptor activates the phosphorylation of bone morphogenetic protein‐related proteins (Smads), which triggers IL‐17 and the transcription factor retinoic acid‐related orphan receptor‐γ (RORt) to differentiate Th17 cells. 15 In addition, IL‐21 plays a crucial role in Th17 elaboration and differentiation. Although not as effective as IL‐6, TGF‐β and IL‐21 can also cause differentiation of Th cells in the absence of IL‐6. 16 , 17 , 18 A second upstream pathway includes the secretion of IL‐21 by natural killer cells following TGF‐β binding. In the presence of IL‐17, IL‐21 stimulates the production of STAT‐3 and RORt, while TGF‐β upregulates RORt expression to secrete IL‐17, which works on transcription factor RORt and provides positive feedback to Th17 cells. The autocrine IL‐21 and STAT3 effects of Th17 cells are fed back to Th17 cells to form an IL‐21 autocrine loop and enhance the expression of IL‐23 and RORγt, which further promotes the increase in the number of Th17 and presents an amplifying effect. 19 Early cell proliferation can be induced by the primary components of the autocrine loop of Th17 cells, TGF‐β and IL‐21. 16 , 17 , 18 Furthermore, the downstream activity includes members of the IL‐23 and IL‐21 cytokine families stimulated in Th17 after the initiation and expansion of differentiation and maintaining phenotypic stability. However, since natural T cells do not put IL‐23 receptors, this cytokine alone cannot induce naive T cells to differentiate into Th17 cells. 20 TGF‐β and IL‐6 prompt the expression of IL‐23 receptors on Th17 cells, and these cells are also sensitive to IL‐23, 16 , 17 , 18 , 21 resulting in upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9). In short, Th17 differentiation includes three measures, TGF‐β and IL‐6 promote its differentiation, IL‐21 assists in its amplification, and IL‐23 maintains its stability. 22

In humans, Th17 cells are copied from the CD161+CD4+ T‐cell subsets of the thymus, which differentiate into Th17 cells expressing RORγt and IL‐23R in the presence of IL‐1β and IL‐23 and maintain their survival. Moreover, the development of human Th17 cells from naive T cells requires TGF‐β. 23 , 24 In summary, human IL‐1β and IL‐23 are complicated in Th17 cell differentiation, and Th17 cells autocrinely produce IL‐21 to expand the scale of separation, activate STAT3, and induce the expression of RORγt. Although IL‐23 does not initially promote Th17 differentiation, it is crucial for T‐cell survival, growth, and maintenance. 25

2.2. Th17 cells and COPD

Th17 cells play a significant role in the systemic inflammation associated with COPD. Activated Th17 cells can produce inflammatory cytokines such as IL‐17 to stimulate the Janus kinase/STAT signaling cascade. 26 In addition, differentiated Th17 cells directly stimulate the activation of the RANK/RANKL signaling pathway to enhance RANKL expression. This pathway is involved in mediating cigarette smoke‐induced increases in alveolar macrophage MMP‐9 expression, which leads to increased airway inflammation and emphysema. 27 Additionally, RANK was found to be involved in IL‐17A‐dependent lymphoid neogenesis, which might shed light on the molecular basis of smoking‐related pulmonary lymphoid neogenesis in COPD patients. 28 At present, most studies on the role of Th17 cells in the pathogenesis of COPD have focused on the expression and impact of IL‐17 in the airway, with IL‐17A being the most identified in the IL‐17 family and most comparable to IL‐17F.

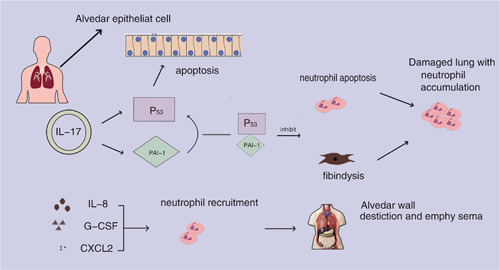

IL‐17A has been found to facilitate neutrophil inflammation in COPD patients. COPD (18 cases, average age 72 years, 13 male, FEV1% = 63.5% [FEV1% is first second expiratory volume as a percentage of expiratory lung volume]) increased numerous IL‐17‐expressing inflammatory cells in the small airway epithelium compared to smokers and nonsmokers. 29 Smokers with COPD showed higher levels of IL‐17A, p53, and plasminogen activator inhibitor‐1 (PAI‐1) than healthy smokers (HSs) and healthy control subjects (HCs). 30 The upregulation of IL‐17A promoted alveolar basal epithelial cell motility and raised p53 and PAI‐1 production in the experiment using bleomycin‐induced alveolar basal epithelial cells to simulate the inflammation in vitro. 31 Furthermore, IL‐17 can increase the expression of p53 and PAI‐1, as well as increase C–X–C motif chemokine ligand 1 (CXCL1), CXCL2, and C–X–C chemokine receptor 2 to induce neutrophil influx, hence enhancing the neutrophil inflammatory reaction in COPD. IL‐17 can also induce the expression of neutrophil chemokines IL‐8, granulocyte‐colony stimulating factor, and CXCL2, and recruit neutrophils to reach inflammatory lesions. 32 A rise in neutrophils could release more myeloperoxidase and neutrophil elastase (NE), which can erode collagen, weaken alveolar walls, and result in emphysema 33 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

By raising p53 and plasminogen activator inhibitor‐1 (PAI‐1), interleukin‐17A (IL‐17A) encourages neutrophil infiltration and lung damage. Alveolar epithelial cells can undergo apoptosis when exposed to both p53 and PAI‐1; however, PAI‐1 prevents neutrophil apoptosis and fibrinolysis in lung tissue. Additionally, IL‐17A stimulates the production of IL‐8, granulocyte‐colony stimulating factor (G‐CSF), and C–X–C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CXCL2), which draws in neutrophils and causes them to produce neutrophil elastase and myeloperoxidase, leading to the breakdown of the alveolar wall and the development of emphysema.

Meanwhile, IL‐17A was also found to promote airway remodeling in COPD. COPD‐related lung structural remodeling can result in permanent airflow obstruction. 34 In animal models of pneumonia and fibrosis, IL‐17A modulates collagen synthesis and secretion in alveolar epithelial cells and promotes epithelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition, while also inhibiting autophagy and promoting autophagy‐related cell death in inflamed lung tissue in a TGF‐dependent manner. 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 Because collagen and inflammation‐related mediators cannot be degraded by autophagy, this results in more severe inflammation and airway remodeling. 40 There have been claims that IL‐17A is associated with histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2) on airway remodeling and collagen deposition in COPD, with contrary effects. While IL‐17A exacerbates CS‐induced airway remodeling and causes inflammatory cells to release the profibrotic cytokine TGF‐1, HDACs prevent the development of Th17 cells by reversing the hyperacetylation of core histones. As a result, the less IL‐17 produced by Th17 cells, the more attenuated or even inhibited airway remodeling in COPD patients. 41 Taken together, IL‐17 can stimulate airway remodeling by increasing TGF‐1 and suppressing inflammatory mediators and autophagy in injured lung tissue.

2.3. Targeting key mediators of inflammation: IL‐17A

Evidence from preclinical and clinical trials demonstrates the role of adaptive immunity in the progression of COPD. Only CD4+ Th17 cells from the T‐lymphocyte lineage have been found to express IL‐17A. Other experimental studies have revealed the existence of numerous IL‐17a induction pathways, including bone‐bridging proteins and other proinflammatory mediators. These are primarily induced by CD1a+ conventional dendritic cells, primary lung antigen‐presenting cells (APCs) that promote Th17 cell differentiation through the action of a secreted cytokine, osteopontin (Spp1). 42 In line with other preclinical indicators, neutral inhibition of IL‐17a and bone‐bridging proteins are tested at the prophylactic level. Therefore, the question of how effectively inhibition of IL‐17a affects COPD progression remains a clinical question. The clinical practice uses commercially accessible, Food and Drug Administration‐approved anti‐TNF, anti‐IL‐6, and anti‐IL‐17A biologics to treat autoimmunity; as predicted, these treatments eventually raise the risk of infection. These treatment options may potentially increase the risk of COPD exacerbation. Abrogating adaptive (memory) immune cells against smokers' self‐antigens is hence the suggested line of action. Studies on Treg cells are required, for instance, to look into the possibility of enhancing Treg cell subsets or, alternatively, the removal of autoreactive T cells utilizing cutting‐edge cellular therapies like chimeric antigen receptor T cells.

3. TREG CELLS

3.1. Development, differentiation, functional mechanism, and phenotypic characteristics of Treg cells

In the thymic selection process, T lymphocytes with high affinities for self‐proteins are removed, whereas those with low affinities can differentiate into Treg cells, a specialized subgroup of CD4+ T cells (Treg cells). These cells block T‐lymphocyte activation by expressing the canonical transcription factor forkhead box P3 (Foxp3). 43 , 44 , 45 In addition to immunosuppressive effects, Treg cells can also maintain tissue balance. For instance, amphiregulin released by Treg cells promotes tissue repair in addition to its well‐known immunoregulatory role. 46 , 47 Research has shown that the proliferation of Th cells mainly depends on glycolytic metabolic pathways. The inhibitory function of Treg cells is more dependent on the mitochondrial oxidation pathway. Gerriets et al. 48 found that activating the PI3K–AKT–mTORC1 axis in Treg cell makes glycolysis promote the proliferation of Treg cell, and the toll‐like receptor signaling route activates the axis.

Treg cells protect themselves against overactivated immune responses. The reduction in the number of Treg cells is linked to the dysfunction of many immune diseases. 49 Therefore, understanding the mechanism of Treg cell function is critical. Studies have found that Treg cells are activated and release granzyme A and perforin to kill effector cells or APCs. 50 or express the costimulatory molecules CTLA‐4 and CD80 and/or CD86 on dendritic cells to regulate them. 51 , 52 Treg cells can also function through mediator‐mediated mechanisms. Immunomodulatory molecules such IL‐35, IL‐10, TGF‐β, and lymphocyte‐activation gene 3 are critically involved in Treg cell function, according to studies. 53 , 54 , 55 Akkaya et al. 56 confirmed that the antigen‐specific Treg cells can downregulate the antigen presentation function of DCs by reducing the peptide–major histocompatibility complex class II on the surface of DCs. Treg cells regulate the function of DCs by microRNA transfer from Tregs to DCs, especially miR‐150‐5p and miR‐142‐3p, 57 which can upregulate IL‐10 and downregulate IL‐6 production. 58

3.2. Treg cells and COPD

Treg cells are marked by the expression of Foxp3 and CD25, which inhibit the proliferation of other T cells, as well as the release of anti‐inflammatory cytokines such as IL‐10 and TGF‐β, which are essential for immune tolerance and immune homeostasis. 59 , 60 Moreover, Treg cells play an important role in respiratory viral infections by suppressing hyperstimulated inflammatory responses and tissue damage induced by other innate and adaptive immune elements. 61 Treg cells may contribute to the onset of autoimmune disorders; however, research on their function in COPD is ongoing.

In patients with acute COPD, the number of Treg cells is higher, and the number of Treg cells in patients with stable COPD and normal people is lower. It shows that patients with acute COPD are greatly affected by Treg cells. When inflammation develops more severely, negative feedback immune regulation can cause Treg cells to inhibit the inflammatory response and reduce the severity of the disease. 62 Certain microenvironments may be highly helpful for the differentiation of Treg cells in the acute phase of COPD, which is positively connected with the severity of the disease. 63

The amount of Treg cells in BAL fluid and different lung tissues vary in people with COPD. Patients with moderate COPD had more CD4+Foxp3+ T cells in lung lymphocyte follicles and no CD4+Foxp3+ T cells in the pulmonary parenchyma. 64 Studies have shown that Foxp3+ cells are upregulated in the large airways and downregulated in the tiny airways. Recent studies have demonstrated that CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cells can develop into proinflammatory Th17 cells, which may contribute to the persistence of COPD‐related chronic inflammation. 65 Inferring from the function of Treg cells, there are data suggesting that smokers with normal lung function may increase Treg cells, while COPD patients should decrease Treg cells. Damage to Treg cells may destroy the homeostasis of the body, resulting in persistent lung inflammation, accompanied by severe lung injury and COPD (Figure 2). This immunological equilibrium exists between several functional subsets of Treg cells and inflammatory cells, such as Th17, Th1, and CD8+ T cells. Given that little is known about the cellular plasticity of Treg cells in vivo, targeting them in the lung parenchyma is a considerable challenge. Furthermore, cytokines like TGF‐β, which are essential for Treg polarization, can also cause fibrosis, and the plasticity of inducible Treg cells in the presence of IL‐6, which promotes a pathogenic FOXP3+IL‐17A+ double‐positive population in vivo, are also known to have these effects. 66 , 67 Therapeutic studies on Treg cells have been shown to be effective in other models of autoimmune disease. 68 , 69 Increased IL‐10, for example, can promote cytostatic action and control inflammation in the lungs.

Figure 2.

Immune homeostasis disturbance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients. Smoking causes a proinflammatory response, but the compensatory anti‐inflammatory system maintains immunological homeostasis in smokers just as it does in healthy nonsmokers. Long‐term smoking can exhaust the anti‐inflammatory compensatory capacity in COPD patients, which causes an imbalance between pro‐ and anti‐inflammatory pathways and eventually disturbs immunological homeostasis. aTreg, activated regulatory T cell; Foxp3, forkhead box P3; IL, interleukin; rTreg, resting Treg; TGF‐β, transforming growth factor‐β; Th, T helper.

4. TH17/TREG IMBALANCE IN COPD

Two CD4+ T‐cell subpopulations (Th17 and Treg cells) have opposing roles in the immunopathogenesis of autoimmune and chronic inflammatory diseases. Th17 cells, as proinflammatory effector T cells, promote autoimmunity, although Treg cells can help by maintaining self‐tolerance and controlling autoimmune responses. Dysregulation of the Th17/Treg cell balance has been linked to the onset and development of various diseases, including cancer, inflammatory diseases, and autoimmune diseases. A variety of factors, including T‐cell receptor (TCR) signaling, cytokines, and metabolic and epigenetic regulators, can influence the differentiation of Th17 and Treg cells and affect their homeostasis. Increasing evidence suggests that the number of posttranslational modifications (PTMs), including phosphorylation, methylation, nitrosylation, acetylation, glycosylation, lipidation, ubiquitination, and SUMOylation, regulates the activity of important molecules, including Foxp3, RORt, and STAT. 69 In addition, PTMs may influence protein folding efficiency and conformational stability, which affects protein structure, location, and function, and hence influences the balance of Th17 and Treg cells. Hence, Th17/Treg cells are believed to be involved in the pathogenesis and disease progression of autoimmune diseases like COPD.

In tissue from COPD Stage I and Stage II patients, Zheng et al. 70 examined the imbalance of Th17/Treg cells and compared it to HSs and nonsmoking control people. Both immunohistochemical and flow cytometry measurements of the COPD group revealed a gradual rise in Th17 cells and a fall in Treg cells. 70 Th17/Treg imbalance in tissue samples from COPD subjects was also found in previous studies. 71 In the present study, IL‐17+ cells were increased in both the COPD group and HSs, while the number of Treg (Foxp3+) and IL‐10+ cells in the small airways of smokers with obstructive lung disease compared with HSs and controls was reduced. Conversely, the authors discovered an increase in Treg cells in lymphoid tissue. 71 Moreover, an increase in the Th17/Treg ratio was found to be negatively associated with lung function. There is an interventricular imbalance of Th17 cells relative to Treg cells in COPD patients' airways, implying a flaw in COPD anti‐inflammatory homeostasis. 72 Another finding suggests that plasma fossa 1 plays a role in Th17/Treg balance. Loss of plasma fossa 1 causes Th17/Treg imbalance. 73 There is also evidence that damage to the TGF‐β/BAMBI (BMP, activin, membrane‐bound inhibitor) pathway may increase the inflammatory response, resulting in a Th17/Treg imbalance. 74

HSs, stable COPD, and acute exacerbation COPD all had more peripheral blood Th17 cells and fewer Treg cells than healthy nonsmokers, 70 indicating an imbalance in the Th17/Treg ratio. These findings are also consistent with the lung tissue damage; however, peripheral blood mononuclear cell samples and lung tissue samples were not from the same subject. 70 Indeed, a few research have assessed lung and peripheral blood samples obtained from the same patient, 75 , 76 which may be related to a limiting element when studying human samples. A study on Th17/Treg cell balance in periodontitis showed that the immune system, skeletal muscle, and microorganisms all affect the balance between Th17/Treg cells. 77 The next step might be to determine whether the microbial environment in COPD patients can impact the balance of Th17/Treg cells and regulate their differentiation.

5. CONCLUSION

The pathogenesis of COPD is very complicated. The existing evidence indicates that several immune cell subgroups interact with one another to contribute to the development of COPD. This article reviews the role of Th17 and Treg cells and their associated cytokines in the pathogenesis and progression of COPD, as well as the latest research on their role in COPD diagnosis and management. The immune pathogenesis of COPD chronic injury is closely connected to the continuous airway inflammation mediated by CD4+ T cells and the changes in the serum cytokine microenvironment. At the same time, the normal balance between Th17 and Treg cells in COPD patients was disrupted. Patients with acute exacerbations of COPD showed a proinflammatory response, while patients with stable COPD showed an anti‐inflammatory response. Since the Th17/Treg imbalance is essential in the COPD lung immune response, the Th17/Treg ratio can be utilized to predict COPD progression. Therefore, specific targeting of Th17/Treg effector cell regulation and/or cytokines that promote their differentiation may provide new strategies for COPD prevention, management, and treatment. Overall, numerous lines of evidence show that T lymphocytes are increased in the lungs of emphysema patients. These findings also raise several questions: How do CD8 and CD4 T lymphocytes differentially contribute to COPD? How do T lymphocytes interact with other immune and nonimmune cells in the lung and how the interactions may differ in disease and homeostasis? The most intriguing question is perhaps why there is augmented TCR signaling in COPD? What triggers and sustains this TCR activation? Not only that but it is also crucial to differentiate between Treg cell populations with different phenotypes and functions to better understand their immunosuppressive activity in COPD. Suppression of adaptive immunity in patients with COPD does not lead to optimal clinical care. While a strong innate immunity is required as the first line of defence against respiratory pathogens, effective eradication of viral, bacterial, or fungal pathogens requires an adaptive immune response. There are still many challenges in the pathogenesis of cigarette smoke‐induced COPD, and we need to develop more effective animal models that realistically replicate the natural history, pathological features, and comorbidities of COPD in humans, as well as explore new treatment approaches.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Ru Ma: Data curation; investigation; methodology; writing—original draft. Kongling Su and Keping Jiao: Data acquisition and interpretation. Jian Liu: Review and editing; supervision; validation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of Lanzhou University, the First Clinical Hospital of Lanzhou University, Gansu Provincial People's Hospital, and all the authors who participated in this study. This work was supported by the Science and Technology Projects of Gansu Province (grant number 18JR3RA344).

Ma R, Su H, Jiao K, Liu J. Role of Th17 cells, Treg cells, and Th17/Treg imbalance in immune homeostasis disorders in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Immun Inflamm Dis. 2023;11:e784. 10.1002/iid3.784

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

REFERENCES

- 1. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) . Global Strategy for Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD, 2020 Report. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD); 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Silva LEF, Lourenço JD, Silva KR, et al. Th17/Treg imbalance in copd development: suppressors of cytokine signaling and signal transducers and activators of transcription proteins. Sci Rep. 2020;10:15287. 10.1038/s41598-020-72305-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. WHO. Projections of Mortality and Causes of Death, 2016 to 2060. WHO; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Young KA, Regan EA, Han MK, et al. Subtypes of Copd have unique distributions and differential risk of mortality. J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019;6:400‐413. 10.15326/jcopdf.6.5.2019.0150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bourbeau J, Pinto LM, Benedetti A. Phenotyping of Copd: challenges and next steps. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:172‐174. 10.1016/s2213-2600(14)70039-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wain LV, Shrine N, Artigas MS, et al. Genome‐wide association analyses for lung function and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease identify new loci and potential druggable targets. Nat Genet. 2017;49:416‐425. 10.1038/ng.3787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moll M, Sakornsakolpat P, Shrine N, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and related phenotypes: polygenic risk scores in Population‐Based and Case–Control Cohorts. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:696‐708. 10.1016/s2213-2600(20)30101-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Philip M, Schietinger A. Cd8(+) T cell differentiation and dysfunction in cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2022;22:209‐223. 10.1038/s41577-021-00574-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Davis MM, Brodin P. Rebooting human immunology. Annu Rev Immunol. 2018;36:843‐864. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-042617-053206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Davis‐Marcisak EF, Deshpande A, Stein‐O'Brien GL, et al. From bench to bedside: single‐cell analysis for cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Cell. 2021;39:1062‐1080. 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lourenço JD, Ito JT, Martins MA, Tibério IFLC, Lopes FDTQS. Th17/Treg imbalance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: clinical and experimental evidence. Front Immunol. 2021;12:804919. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.804919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Krueger PD, Osum KC, Jenkins MK. CD4(+) memory T‐cell formation during type 1 immune responses. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Biol. 2021;13:a038141. 10.1101/cshperspect.a038141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yin X, Chen S, Eisenbarth SC. Dendritic cell regulation of T helper cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2021;39:759‐790. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-101819-025146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Spinner CA, Lazarevic V. Transcriptional regulation of adaptive and innate lymphoid lineage specification. Immunol Rev. 2021;300:65‐81. 10.1111/imr.12935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhou L, Lopes JE, Chong MMW, et al. Tgf‐β‐induced Foxp3 inhibits T(H)17 cell differentiation by antagonizing RORγt function. Nature. 2008;453:236‐240. 10.1038/nature06878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhou L, Ivanov II, Spolski R, et al. Il‐6 programs T(H)‐17 cell differentiation by promoting sequential engagement of the Il‐21 and Il‐23 pathways. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:967‐974. 10.1038/ni1488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nurieva R, Yang XO, Martinez G, et al. Essential autocrine regulation by Il‐21 in the generation of inflammatory T cells. Nature. 2007;448:480‐483. 10.1038/nature05969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Korn T, Bettelli E, Gao W, et al. Il‐21 initiates an alternative pathway to induce proinflammatory T(H)17 cells. Nature. 2007;448:484‐487. 10.1038/nature05970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wei L, Laurence A, Elias KM, O'Shea JJ. Il‐21 is produced by Th17 cells and drives Il‐17 production in a Stat3‐dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:34605‐34610. 10.1074/jbc.M705100200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Veldhoen M, Hocking RJ, Atkins CJ, Locksley RM, Stockinger B. Tgfβ in the context of an inflammatory cytokine milieu supports de novo differentiation of Il‐17‐producing T cells. Immunity. 2006;24:179‐189. 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mangan PR, Harrington LE, O'Quinn DB, et al. Transforming growth factor‐β induces development of the T(H)17 lineage. Nature. 2006;441:231‐234. 10.1038/nature04754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Noack M, Miossec P. Th17 and regulatory T cell balance in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:668‐677. 10.1016/j.autrev.2013.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yang L, Anderson DE, Baecher‐Allan C, et al. Il‐21 and Tgf‐β are required for differentiation of human T(H)17 cells. Nature. 2008;454:350‐352. 10.1038/nature07021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Manel N, Unutmaz D, Littman DR. The differentiation of human T(H)‐17 cells requires transforming growth factor‐β and induction of the nuclear receptor RORγt. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:641‐649. 10.1038/ni.1610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bunte K, Beikler T. Th17 cells and the Il‐23/IlL‐17 axis in the pathogenesis of periodontitis and immune‐mediated inflammatory diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:3394. 10.3390/ijms20143394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liu J, Ouyang Y, Zhang Z, et al. The role of Th17 cells: explanation of relationship between periodontitis and Copd? Inflamm Res. 2022;71:1011‐1024. 10.1007/s00011-022-01602-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhou L, Le Y, Tian J, et al. Cigarette smoke‐induced Rankl expression enhances Mmp‐9 production by alveolar macrophages. Int J Chronic Obstruct Pulm Dis. 2019;14:81‐91. 10.2147/copd.S190023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Xiong J, Zhou L, Tian J, et al. Cigarette smoke‐induced lymphoid neogenesis in Copd involves Il‐17/Rankl pathway. Front Immunol. 2021;11:588522. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.588522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Eustace A, Smyth LJC, Mitchell L, Williamson K, Plumb J, Singh D. Identification of cells expressing Il‐17a and Il‐17f in the lungs of patients with Copd. Chest. 2011;139:1089‐1100. 10.1378/chest.10-0779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gouda MM, Prabhu A, Bhandary YP. Curcumin alleviates Il‐17A‐mediated p53‐Pai‐1 expression in bleomycin‐induced alveolar basal epithelial cells. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119:2222‐2230. 10.1002/jcb.26384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gouda MM, Prabhu A, Bhandary YP. Il‐17a suppresses and curcumin up‐regulates Akt expression upon bleomycin exposure. Mol Biol Rep. 2018;45:645‐650. 10.1007/s11033-018-4199-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hansen MJ, Chan SPJ, Langenbach SY, et al. Il‐17a and serum amyloid a are elevated in a cigarette smoke cessation model associated with the persistence of pigmented macrophages, neutrophils and activated Nk cells. PLoS One. 2014;9:e113180. 10.1371/journal.pone.0113180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cohen AB, Chenoweth DE, Hugli TE. The release of elastase, myeloperoxidase, and lysozyme from human alveolar macrophages. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1982;126:241‐247. 10.1164/arrd.1982.126.2.241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Barnes PJ, Burney PGJ, Silverman EK, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15076. 10.1038/nrdp.2015.76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Li X, Ye Y, Zhou X, Huang C, Wu M. Atg7 enhances host defense against infection via downregulation of superoxide but upregulation of nitric oxide. J Immunol. 2015;194:1112‐1121. 10.4049/jimmunol.1401958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ye Y, Tan S, Zhou X, et al. Inhibition of P‐Iκbα ubiquitylation by autophagy‐related gene 7 to regulate inflammatory responses to bacterial infection. J Infect Dis. 2015;212:1816‐1826. 10.1093/infdis/jiv301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li X, He S, Zhou X, et al. Lyn delivers bacteria to lysosomes for eradication through Tlr2‐initiated autophagy related phagocytosis. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005363. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhuang Y, Li Y, Li X, Xie Q, Wu M. Atg7 knockdown augments concanavalin A‐induced acute hepatitis through an Ros‐mediated P38/Mapk pathway. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0149754. 10.1371/journal.pone.0149754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wang Y, Xu J, Meng Y, Adcock IM, Yao X. Role of inflammatory cells in airway remodeling in Copd. Int J Chronic Obstruct Pulm Dis. 2018;13:3341‐3348. 10.2147/copd.S176122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Xie Q, Liu Y, Li X. The interaction mechanism between autophagy and apoptosis in colon cancer. Transl Oncol. 2020;13:100871. 10.1016/j.tranon.2020.100871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lai T, Tian B, Cao C, et al. Hdac2 suppresses Il17a‐mediated airway remodeling in human and experimental modeling of Copd. Chest. 2018;153:863‐875. 10.1016/j.chest.2017.10.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shan M, You R, Yuan X, et al. Agonistic induction of PPARγ reverses cigarette smoke‐induced emphysema. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:1371‐1381. 10.1172/jci70587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Savage PA, Klawon DEJ, Miller CH. Regulatory T cell development. Annu Rev Immunol. 2020;38:421‐453. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-100219-020937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Takeuchi Y, Hirota K, Sakaguchi S. Impaired T cell receptor signaling and development of T cell‐mediated autoimmune arthritis. Immunol Rev. 2020;294:164‐176. 10.1111/imr.12841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yi J, Kawabe T, Sprent J. New insights on T‐cell self‐tolerance. Curr Opin Immunol. 2020;63:14‐20. 10.1016/j.coi.2019.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Akamatsu M, Mikami N, Ohkura N, et al. Conversion of antigen‐specific effector/memory T cells into Foxp3‐expressing T(Reg) cells by inhibition of Cdk8/19. Science Immunol. 2019;4:eaaw2707. 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaw2707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sakaguchi S, Mikami N, Wing JB, Tanaka A, Ichiyama K, Ohkura N. Regulatory T cells and human disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 2020;38:541‐566. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-042718-041717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gerriets VA, Kishton RJ, Johnson MO, et al. Foxp3 and Toll‐like receptor signaling balance T(Reg) cell anabolic metabolism for suppression. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:1459‐1466. 10.1038/ni.3577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Dejaco C, Duftner C, Grubeck‐Loebenstein B, Schirmer M. Imbalance of regulatory T cells in human autoimmune diseases. Immunology. 2006;117:289‐300. 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02317.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Grossman WJ, Verbsky JW, Tollefsen BL, Kemper C, Atkinson JP, Ley TJ. Differential expression of granzymes a and B in human cytotoxic lymphocyte subsets and T regulatory cells. Blood. 2004;104:2840‐2848. 10.1182/blood-2004-03-0859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Cederbom L, Hall H, Ivars F. Cd4+Cd25+ regulatory T cells down‐regulate co‐stimulatory molecules on antigen‐presenting cells. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:1538‐1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Fallarino F, Grohmann U, Hwang KW, et al. Modulation of tryptophan catabolism by regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1206‐1212. 10.1038/ni1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Collison LW, Workman CJ, Kuo TT, et al. The inhibitory cytokine Il‐35 contributes to regulatory T‐cell function. Nature. 2007;450:566‐569. 10.1038/nature06306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tang Q, Bluestone JA. The Foxp3+ regulatory T cell: a jack of all trades, master of regulation. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:239‐244. 10.1038/ni1572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Paterson AM, Lovitch SB, Sage PT, et al. Deletion of Ctla‐4 on regulatory T cells during adulthood leads to resistance to autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2015;212:1603‐1621. 10.1084/jem.20141030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Akkaya B, Oya Y, Akkaya M, et al. Regulatory T cells mediate specific suppression by depleting peptide‐Mhc Class ii from dendritic cells. Nat Immunol. 2019;20:218‐231. 10.1038/s41590-018-0280-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Tung SL, Boardman DA, Sen M, et al. Regulatory T cell‐derived extracellular vesicles modify dendritic cell function. Sci Rep. 2018;8:6065. 10.1038/s41598-018-24531-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. King BC, Esguerra JLS, Golec E, Eliasson L, Kemper C, Blom AM. Cd46 activation regulates Mir‐150‐mediated control of Glut1 expression and cytokine secretion in human Cd4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2016;196:1636‐1645. 10.4049/jimmunol.1500516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bruzzaniti S, Bocchino M, Santopaolo M, et al. An immunometabolic pathomechanism for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:15625‐15634. 10.1073/pnas.1906303116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Attridge K, Walker LSK. Homeostasis and function of regulatory T cells (Tregs) in vivo: lessons from Tcr‐transgenic Tregs. Immunol Rev. 2014;259:23‐39. 10.1111/imr.12165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Huang S, He Q, Zhou L. T cell responses in respiratory viral infections and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chin Med J. 2021;134:1522‐1534. 10.1097/cm9.0000000000001388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lundell S, Holmner Å, Rehn B, Nyberg A, Wadell K. Telehealthcare in Copd: a systematic review and meta‐analysis on physical outcomes and dyspnea. Respir Med. 2015;109:11‐26. 10.1016/j.rmed.2014.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Miravitlles M, Vogelmeier C, Roche N, et al. A review of National Guidelines for Management of Copd in Europe. Eur Respir J. 2016;47:625‐637. 10.1183/13993003.01170-2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Plumb J, Smyth LJC, Adams HR, Vestbo J, Bentley A, Singh SD. Increased T‐regulatory cells within lymphocyte follicles in moderate Copd. Eur Respir J. 2009;34:89‐94. 10.1183/09031936.00100708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wu JH, Zhou M, Jin Y, et al. Generation and immune regulation of Cd4(+)Cd25(−)Foxp3(+) T cells in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Front Immunol. 2019;10:220. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Bluestone JA, Trotta E, Xu D. The therapeutic potential of regulatory T cells for the treatment of autoimmune disease. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2015;19:1091‐1103. 10.1517/14728222.2015.1037282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Dong S, Hiam‐Galvez KJ, Mowery CT, et al. The effect of low‐dose IL‐2 and Treg adoptive cell therapy in patients with type 1 diabetes. JCI Insight. 2021;6. 10.1172/jci.insight.147474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Raffin C, Vo LT, Bluestone JA. T(reg) cell‐based therapies: challenges and perspectives. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:158‐172. 10.1038/s41577-019-0232-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Ferreira LMR, Muller YD, Bluestone JA, Tang Q. Next‐generation regulatory T cell therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019;18:749‐769. 10.1038/s41573-019-0041-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zheng X, Zhang L, Chen J, Gu Y, Xu J, Ouyang Y. Dendritic cells and Th17/Treg ratio play critical roles in pathogenic process of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;108:1141‐1151. 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.09.113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Sales DS, Ito JT, Zanchetta IA, et al. Regulatory T‐cell distribution within lung compartments in Copd. J Chron Obstruct Pulm Dis. 2017;14:533‐542. 10.1080/15412555.2017.1346069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Li H, Liu Q, Jiang Y, Zhang Y, Xiao W, Zhang Y. Disruption of Th17/Treg balance in the sputum of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Med Sci. 2015;349:392‐397. 10.1097/maj.0000000000000447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Sun N, Wei X, Wang J, Cheng Z, Sun W. Caveolin‐1 promotes the imbalance of Th17/Treg in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Inflammation. 2016;39:2008‐2015. 10.1007/s10753-016-0436-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Polverino F, Seys LJM, Bracke KR, Owen CA. B cells in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: moving to center stage. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiology. 2016;311:L687‐L695. 10.1152/ajplung.00304.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Lourenço JD, Teodoro WR, Barbeiro DF, et al. Th17/Treg‐related intracellular signaling in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: comparison between local and systemic responses. Cells. 2021;10:1569. 10.3390/cells10071569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Sileikiene V, Laurinaviciene A, Lesciute‐Krilaviciene D, Jurgauskiene L, Malickaite R, Laurinavicius A. Levels of Cd4+ Cd25+ T regulatory cells in bronchial mucosa and peripheral blood of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease indicate involvement of autoimmunity mechanisms. Adv Respir Med. 2019;87:159‐166. 10.5603/arm.2019.0023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Deng J, Lu C, Zhao Q, Chen K, Ma S, Li Z. The Th17/Treg cell balance: crosstalk among the immune system, bone and microbes in periodontitis. J Periodont Res. 2022;57:246‐255. 10.1111/jre.12958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.