Abstract

Background:

Hip strength is an important factor for control of the lumbo-pelvic-hip complex. Deficits in hip strength may affect throwing performance and contribute to upper extremity injuries.

Hypothesis:

Deficits in hip abduction isometric strength would be greater in those who sustained an upper extremity injury and hip strength would predict injury incidence.

Study Design:

Prospective cohort study.

Level of Evidence:

Level 3.

Methods:

Minor League baseball players (n = 188, age = 21.5 ± 2.2 years; n = 98 pitchers; n = 90 position players) volunteered. Hip abduction isometric strength was assessed bilaterally with a handheld dynamometer in side-lying position, expressed as torque using leg length (N·m). Hip abduction strength asymmetry was represented by [(trail leg/lead leg) × 100]. Overuse or nontraumatic throwing arm injuries were prospectively tracked. Poisson regression models were used to estimate relative risk ratios associated with hip asymmetry; confounders, including history of prior overuse injury in the past year, were included.

Results:

Hip abduction asymmetry ranged from 0.05% to 57.5%. During the first 2 months of the season, 18 players (n = 12 pitchers) sustained an upper extremity injury. In pitchers, for every 5% increase in hip abduction asymmetry, there was a 1.24 increased risk of sustaining a shoulder or elbow injury. No relationship between hip abduction strength and injury was observed for position players.

Conclusion:

Hip abduction asymmetry in pitchers was related to subsequent upper extremity injuries. The observed risk ratio indicates that hip abduction asymmetry may contribute a significant but small increased risk of injury.

Clinical Relevance:

Hip abduction muscle deficits may affect pitching mechanics and increase arm stress. Addressing hip asymmetry deficits that exceed 5% may be beneficial in reducing upper extremity injury rates in pitchers.

Keywords: core stability, elbow injury, pitching, shoulder injury

The baseball throw is a coordinated sequence of motion from the lower extremities through the trunk to the upper extremities. The hip complex and lower extremities provide a stable base for the transfer of force in a proximal to distal sequence.10,21 Specifically, the hip abductor muscles stabilize and control hip motion during a pitch or throw. Deficits of the hip abductors can negatively affect the force transfer and contribute to poor performance during pitching and throwing.15,24,25 Hip abduction weakness in pitchers was related to increased knee and pelvic motion during a dynamic single-leg step-down task. 26 Specifically, decreased hip torque was related to increased knee valgus, and increased pelvic drop on the trail leg during the single-leg step-down task. 26 Lumbo-pelvic-hip stability deficits have also been shown to relate to shoulder strength deficits and injuries in throwers.6,9,13,20 However, the relationship between arm injuries and hip abductor strength deficiencies in professional baseball players has not been identified.

Upper extremity injuries accounted for 51% of injuries in professional baseball players in 2002-2008. 19 Of these injuries, 21% occurred at the shoulder and 16% occurred at the elbow.5,19 Elbow injuries represent the highest average number of days missed of all musculoskeletal injuries in professional baseball. 7 Identification of modifiable physical factors related to upper extremity injuries is critically needed. Despite the importance of the role of the kinetic chain, very few studies have examined hip abduction strength profiles and their relationship to injuries in baseball players. In a small sample of professional players, Laudner et al 15 reported that position players have greater hip abduction strength on the trail leg compared with pitchers. Additionally, collegiate pitchers have similar isokinetic hip abduction strength profiles between their lead and trail legs. 23 Investigations into hip strength deficits as possible risk factors for upper extremity injuries are needed. Specifically, exploring the relationship between hip abduction strength and upper extremity injuries can help inform the development of injury prevention programs.

The purpose of this study was to determine if hip abductor isometric strength deficits are related to the incidence of upper extremity injuries in professional baseball pitchers and position players. It was hypothesized that deficits in hip abduction isometric strength would be greater in those who sustained an upper extremity injury and that hip strength would predict injury incidence. Understanding the relationship between preseason hip abduction isometric strength with upper extremity injury will provide foundational knowledge to optimize screening for injury risk and the development of prevention and treatment programs.

Methods

Participants

This study was approved by the University of Southern California Institutional Review Board. Before participation, the approved procedures, risks, and benefits were explained to all participants. Written informed consent was obtained from the participants. Data were routinely collected as part of 2017 and 2018 preseason physical examinations on Minor League baseball players from a single organization. Participant data were included for those with the inclusion criteria of (1) freedom from injury at the time of preseason testing and (2) on team roster for the full competitive season. Participants were excluded if any of the following criteria were met: (1) not cleared to participate in baseball activities, (2) currently receiving treatment for an injury, and (3) players joining the organization after spring training. History of an upper extremity injury was not considered for exclusion from participation but was assessed in the analysis. Preseason strength training program records were not available. Standard strength and conditioning programs for the organization were performed during the season, but details were not available.

Sample size calculation assumed the healthy group has on average no hip abduction torque asymmetry, size of injured versus healthy subjects 2:3, and the injured group has 15% asymmetry as the cutoff to increase risk of injury. 14 The standard deviation (SD) can vary; we performed a sample size calculation on a range of SDs (5%-20%), resulting in a required minimum sample size of 25 injured participants (Table 1).

Table 1.

Estimated sample size calculations

| Mean Hip Asymmetry Healthy | Mean Hip Asymmetry Injured | SD | N1 (Healthy) | N2 (Injured) | Total N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.15 | 0.05 | 5 | 3 | 8 |

| 0 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 7 | 5 | 12 |

| 0 | 0.15 | 0.1 | 11 | 7 | 18 |

| 0 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 14 | 10 | 24 |

| 0 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 22 | 14 | 36 |

| 0 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 30 | 20 | 50 |

| 0 | 0.15 | 0.2 | 37 | 25 | 62 |

Procedures

Data were collected at the organization’s Minor League training facility. A health history questionnaire was used to collect information regarding current upper extremity injury status and upper extremity overuse injury history from the past year. Specific injury questions included the following: body part injured, injury diagnosis, time lost due to the injury, and upper extremity surgical history. Demographic data of age, height, weight, position, throwing arm, and years of Minor League Baseball participation were recorded.

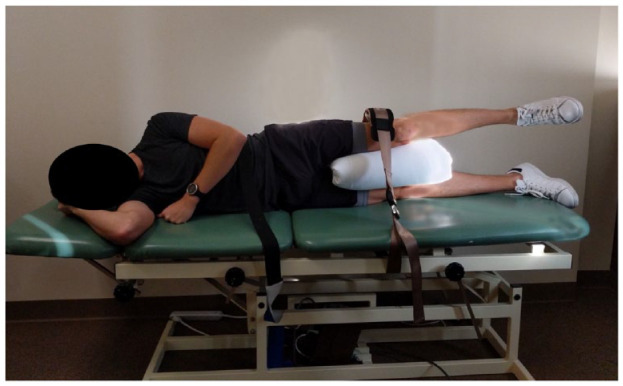

Hip Abduction Isometric Strength

Strength was assessed with the participants in a side-lying position with the top leg fully extended and in line with the trunk. A pillow was placed between the participant’s legs, so the testing leg was in a neutral hip abduction. A strap was placed just proximal to the iliac crest and secured firmly around the underside of the table to stabilize the participant’s trunk (Figure 1). A handheld dynamometer (HHD) (MicroFet 2, Hoggan Scientific) was used to obtain bilateral strength measurements. The HHD was placed 5 cm proximal to the lateral knee joint line on the top leg and a stabilization strap was placed over the HHD and around the table. 11 Once positioned, the participants performed 2 maximal effort isometric contractions against the HHD for 5 seconds, measured in newtons (N). Leg length in meters (m) was measured from the greater trochanter to the placement of the HHD, and then multiplied by isometric strength to present normalized hip abduction torque (N·m). Hip abduction strength ratio was calculated by dividing the trail leg strength by the lead leg strength and then multiplied by 100 to represent the percent of hip asymmetry. Two trials were measured bilaterally, and the average was used for data analysis. One minute of rest was provided between trials. The lead leg is the leg contralateral to the throwing arm, and the trail leg is ipsilateral to the throwing arm. Test-retest reliability for hip abduction isometric strength was established before data collection. Interclass correlation coefficient (3, 2), standard error of the mean, and minimal detectable change (MDC90) calculated for hip abduction isometric strength were 0.98, 18.6 N·m, and 26.1 N·m, respectively.

Figure 1.

Testing position for isometric hip abduction strength.

Injury Tracking

All players who reported upper extremity pain were examined and diagnosed by the sports medicine staff, and injuries were recorded. An upper extremity–related injury was defined as (1) occurred as a result of baseball participation, (2) missed at least 1 day of practice or a game because of the injury, and (3) diagnosed as a related injury of any shoulder, elbow, or wrist muscle, joint, tendon, bone, and nerve-related pain of the throwing arm. Injuries occurring outside of baseball-related training were excluded. Upper extremity injuries were recorded during the entire season; however, for this current study, only injuries from March through April (2 months) were examined.

Statistical Analysis

Hip abduction torque asymmetry greater than 100% indicates the leading side hip is stronger than the trail hip. As the dataset contains multiple records of the same player, a mixed effect model was built to check intraclass correlation between repeated measurements and determine if multilevel models were needed. 16 A 15% threshold was used for the power analysis, but in the analysis we did not find nonlinearity indicating a cut-point for hip abduction asymmetry in the association between the risk of upper extremity injury, so hip abduction asymmetry was treated as a continuous variable. The risk of upper extremity injury for each 5% hip strength asymmetry was assessed by using robust Poisson regression models to estimate relative risks (RRs). 27 Fractional polynomial was used to assess linearity of the relationship between injury and hip strength asymmetry. If complicated modeling of hip strength asymmetry is needed, asymmetry would be categorized for better interpretation with cut points being the turning points of a plot with log-transformed P(injury) versus hip strength asymmetry.

Potential confounders including player demographics (age, weight, and height), throwing arm prior injury (yes/no), throwing arm surgery history (yes/no), shoulder pain on testing day (yes/no), years of professional experience, and directionality of asymmetry (lead strong vs trail strong) were assessed and those that change the parameter estimate of hip strength asymmetry by more than 15% were kept in the model. Interaction between directionality and hip strength asymmetry was also tested. Any observations with missing variables mentioned above were removed. Analysis was completed on 2 sets of data, with players stratified by position (pitcher vs position player). The analyses were generated using SAS software (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

A total of 188 players (98 pitchers and 90 position players) had complete datasets. During the first 2 months of the season, 18 players were classified as injured—12 pitchers and 6 position players (Table 2). The characteristics of pitchers and position players are shown in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. Mixed effect model was attempted to measure intraclass correlation coefficient and we did not find evidence of significant intraclass correlation. Therefore, single-level models were performed.

Table 2.

Upper extremity injuries sustained by study participants

| Injury | Pitchers | Position Players |

|---|---|---|

| Shoulder injury | ||

| Biceps tendonitis | 1 | 0 |

| Biceps strain | 0 | 0 |

| Glenohumeral ligament tear | 1 | 0 |

| SLAP tear | 0 | 1 |

| Pectoralis minor strain | 1 | 0 |

| Rotator cuff strain | 1 | 2 |

| Impingement | 1 | 1 |

| Latissimus dorsi strain | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 5 | 4 |

| Elbow injury | ||

| Ulnar collateral ligament sprain | 3 | 0 |

| Triceps strain | 0 | 0 |

| Valgus extension overload | 1 | 1 |

| Ulnar neuritis | 1 | 0 |

| Flexor strain | 2 | 0 |

| Olecranon fracture | 0 | 0 |

| Ulnar nerve irritation | 0 | 0 |

| Lateral epicondylitis | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 7 | 2 |

SLAP tear, superior labrum anterior and posterior tear.

Table 3.

Hip strength and characteristic data for injured and noninjured pitchers

| Pitchers’ characteristics | Injured (n = 12) | Noninjured (n = 86) |

|---|---|---|

| Ag, y | 21.3 (2.6) | 22(2.3) |

| Height, cm | 186.3 (7.6) | 188.3(6.3) |

| Weight, kg | 86.2 (9.2) | 91.8 (11.5) |

| Years in MiLB | 3.3 (1.6) | 3.7 (2) |

| Prior injury, % | 33.3 | 25.6 |

| History of surgery on throwing arm, % | 0.0 | 15.1 |

| Hip asymmetry ratio, % | 15.6 (14.4) | 10 (9.6) |

| Lead leg stronger than trail leg, % | 33.3 | 47.7 |

MiLB, Minor League Baseball.

Table 4.

Hip strength and characteristic data for injured and noninjured position players

| Position players’ characteristics | Injured (n = 6) | Noninjured (n = 84) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 19.5 (2.1) | 21.2 (2) |

| Height, cm | 181.2 (5.9) | 181.6 (5.6) |

| Weight, kg | 81.4 (10.7) | 85.1 (10.3) |

| Years in MiLB | 3.3 (1.4) | 3.5 (1.6) |

| Prior injury, % | 33.3 | 21.8 |

| History of surgery on throwing arm, % | 0 | 9.5 |

| Hip asymmetry ratio, % | 8.2 (5) | 10.6 (9.5) |

| Lead leg stronger than trail leg, % | 50 | 48.8 |

MiLB, Minor League Baseball.

Using fractional polynomial, the relationship between injury and hip strength asymmetry was linear for pitchers while quadratic for position players. None of the injured players had a history of surgery on the throwing arm, or pain in shoulder or elbow on the testing day; therefore, these 2 variables were omitted from all the models. History of prior injury was included in the model as a predictor for injury; however, it did not meet the threshold of 15% for a confounder of the relationship between hip abduction torque and injury. Specifically, history of injury changed the RR per 5% hip abduction torque asymmetry by 2% for pitchers and 4% for position players. All potential confounders and interactions were not significant and removed from the model.

In pitchers, the regression model revealed a marginally significant association between hip strength asymmetry and injury; with each 5% increase in asymmetry the risk of injury was 1.17 times higher (95% CI 0.99-1.38), P = 0.05. In position players, there was no significant association between hip asymmetry and risk of upper extremity injury (P = 0.18). A sensitivity analysis was done by removing extreme observations with Cook’s D for values greater than 2 SDs to assess their impact on the final models. This removed 2 observations for pitchers and 1 observation for position players. The 2 removed pitchers were both not injured and had hip strength asymmetry of 57.5% and 8.4%; the position player removed was not injured and had an asymmetry of 8.7%. The final model summaries are shown in Tables 5 and 6. In pitchers, the association between hip abduction asymmetry and injury was significant (P < 0.01) with an RR of 1.24 (95% CI 1.06-1.46). Using the model estimates, the percent increased risk of injury based on the amount of hip asymmetry can be calculated; 5% asymmetry has an increased risk of injury of 17%, 10% asymmetry has an increased risk of 37%, and 15% asymmetry has an increased risk of injury of 60%. For position players, there was no significant association between hip asymmetry and risk of upper extremity injury after outlier removal.

Table 5.

Final model after sensitivity analysis for pitchers (n = 98)

| 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Relative Risk | P | Lower Limit | Upper Limit |

| Intercept | 0.07 | <0.0001 | 0.03 | 0.16 |

| Asymmetric (continuous, every 5% increment) | 1.24 | 0.008 | 1.06 | 1.46 |

Table 6.

Final model summary for position players (n = 89)

| 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Relative Risk | P | Lower Limit | Upper Limit |

| Intercept | 0.02 | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.31 |

| Asymmetric (continuous, every 5% increment) | 6.01 | 0.17 | 0.47 | 76.68 |

| Asymmetric squared | 0.63 | 0.08 | 0.38 | 1.06 |

Discussion

This is the first study to quantify upper extremity injury risk related to hip abduction strength. Hip abduction strength asymmetry increases the risk of injury incidence in professional baseball pitchers within the first 2 months of the baseball season. Specifically, for a 5% increase in hip abduction strength asymmetry, there was a 1.24 increased risk of sustaining a shoulder or elbow injury. This RR indicates a small but significant increased risk of injury with hip abduction strength asymmetry. The 5% increment is arbitrary, as a continuous variable any percentage increment will give the same conclusion. Hip abduction asymmetry contributes to arm injury in pitchers. Interestingly, absolute hip abduction torque for the trail leg and the lead leg did not differentiate injured and noninjured pitchers or position players. Asymmetry in hip abduction strength in pitchers appears to be related to the development of upper extremity injuries. Hip abduction strength asymmetry may indicate that altered adaptations or strength compensations occur between hips as a result of pitching, which contributes to increased likelihood injury.

Upper extremity injuries represent a significant source of disability among professional baseball players. Identifying modifiable physical factors related to these injuries provide foundational knowledge for the developmental of targeted prevention and treatment strategies. Hip abductor muscles are critical for optimal throwing and pitching mechanics. Specifically, hip abductor muscle performance in the trail leg enables hip stabilization during both the single- and double-leg stance phases of pitching and throwing. 15 The hip abductors of the trail leg function to lengthen the pitcher’s stride and prevent pelvic drop during the wind-up and early cocking phases of the motion.12,15 In the lead leg, the hip abductors provide stabilization to the leg at foot contact that contributes to increased rotation and flexion of the trunk after the late cocking phase. 24 Hip abductor muscle performance in both limbs is critical for hip stability and movement during pitching and throwing. Hip abductor strength asymmetry is of greater importance than individual hip abductor limb muscle performance for identifying upper extremity injury risk in pitchers.

Previous lower extremity research has identified leg strength asymmetry as a risk factor for injury.1,17 Hip abductor weakness inhibits energy transfer from the lower extremity to the wrist at ball release and increases loads at the shoulder and elbow, which may contribute to injury. 4 Hip abductor muscle strength asymmetry may be a more sensitive metric of altered hip stabilization than absolute hip abductor strength. Pitchers who were injured had higher hip asymmetry compared with those who were healthy. This same trend was not observed in position players. Position players who did not sustain an injury had greater mean hip asymmetry, but lower median hip asymmetry than the players who were injured. The sample size of injured pitchers and position players was relatively small, thus limiting generalizability. Beckett et al 3 examined normalized hip abduction strength in adolescent baseball players and the ratio of hip abduction between legs was 1.02. Strength asymmetry greater than 10% between limbs may increase injury rates in athletes. 14 Similarly, a cutoff of less than 10% between limbs is a suggested benchmark for determining return to play in injured athletes.2,18,22

Altered muscle performance and hip stabilization have been speculated to contribute to upper extremity injury in baseball players, but the evidence supporting this is limited. Culiver et al 8 suggest that larger hip abduction strength asymmetry may affect a pitcher’s ability to generate and transfer forces during pitching, which may increase the risk of injury. Hip abduction strength or asymmetry did not contribute to increased risk in position players. Position players generally sustain less shoulder and elbow injuries compared with pitchers and they also face different sport-related demands, which may help explain why no difference in upper extremity injury risk was observed. Zipser et al 26 reported that hip abduction strength was not related to single-leg step-down mechanics in position players and speculated that these results may be due to position players having throwing patterns that vary in distance and intensity. Position players also do not throw from a mound.

Previous studies have identified that a history of injury increases the risk of injury in the subsequent competitive season. History of upper extremity overuse injury in the past year was assessed in the current study; however, it was not found to be a confounder and was not included in the final model. Adjusting for history of upper extremity overuse injury changed the RR per 5% increase in hip abduction torque asymmetry by 2% for pitchers and 4% for position players. It is speculated that the small sample size of both players with a history of upper extremity overuse injury in the past year and players who sustained an injury during the season were small. Further research is needed to more comprehensively examine the contributions of other hip strength measures on injury risk and how these measures are related to the severity or time-loss of an injury.

There are several major limitations to this study. Because of time constraints during testing, only hip abduction strength was assessed. Other hip abduction muscle strength assessments may contribute to the ability to differentiate baseball players who are more susceptible to injury. Hip abduction strength was measured in an anatomic static position, which does not represent the dynamic position of the pitcher’s hips during the push-off and landing phases of the pitch when propulsion and stabilization are important. This study did not account for training, rehabilitation, and injury prevention programs that may have occurred after preseason testing. Hip abduction strength was measured during preseason, leaving time for changes in muscle performance with training as the season progressed. By limiting the time to primarily pre- to early-season, we controlled for longer term changes in hip abduction strength over the season. Comparisons for hip abduction strength for the position players should be interpreted with caution because of the low number of injured players. Including the findings for the position players is important because the results indicate hip asymmetry and injury risks are different between pitchers and position players. Too often, null findings are removed and then no one knows that a group may not have similar injury risk profiles. Results could vary across position; however, we did not have enough participants to do a subgroup analysis that stratified the data by position. Unfortunately, the accuracy of the HHD tested against another testing device was not obtained.

Conclusion

Hip abduction torque asymmetry in pitchers was related to subsequent incidence of upper extremity injury in the first 2 months of the baseball season. For each 5% increase in hip abduction strength asymmetry between legs, the risk of sustaining a shoulder or elbow injury was 1.24 times higher in pitchers. Hip abduction asymmetry muscle deficits may affect pitching mechanics and increase arm stress. No relationship between hip abduction strength and injury was observed for position players.

Footnotes

The following authors declared potential conflicts of interest: L.A.M. received grant from Major League Baseball. J.C.S. received grant from Major League Baseball. H.A.P. received grant from Major League Baseball to support travel to meetings or other purposes. Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education provided support for H.A.P. for manuscript preparation.

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Funding for this study was provided by Major League Baseball. This research was supported in part by an appointment to the postgraduate research program at the U.S. Army Aeromedical Research Laboratory administered by Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy and the U.S. Army Medical Research and Development Command.

Disclaimer: The views, opinions, and/or findings contained in this report are those of the author(s) and should not be construed as an official Department of the Army position, policy, or decision, unless so designated by other official documentation. Citation of trade names in this report does not constitute an official Department of the Army endorsement or approval of the use of such commercial items.

ORCID iD: Hillary A. Plummer  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3282-2538

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3282-2538

References

- 1. Abt JP, Sell TC, Crawford K, et al. Warrior model for human performance and injury prevention: Eagle Tactical Athlete Program Part II. J Spec Oper Med. 2010;10:22-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Augustsson J, Thomee R, Karlsson J. Ability of a new hop test to determine functional deficits after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2004;12:350-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beckett M, Hannon M, Ropiak C, Gerona C, Mohr K, Limpisvasti O. Clinical assessment of scapula and hip joint function in preadolescent and adolescent baseball players. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:2502-2509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Burkhart SS, Morgan CD, Ben Kibler W. The disabled throwing shoulder: spectrum of pathology Part III: the SICK scapula, scapular dyskinesis, the kinetic chain, and rehabilitation. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:641-661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Camp CL, Conte S, D’Angelo J, Fealy SA, Ahmad CS. Effect of predraft ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction on future performance in professional baseball: a matched cohort comparison. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46:1459-1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chaudhari AM, McKenzie CS, Pan X, Onate JA. Lumbopelvic control and days missed because of injury in professional baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:2734-2740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ciccotti MG, Pollack KM, Ciccotti MC, et al. Elbow injuries in professional baseball: epidemiological findings from the Major League Baseball Injury Surveillance System. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45:2319-2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Culiver A, Garrison JC, Creed KM, Conway JE, Goto S, Werner S. Correlation among Y-balance test-lower quarter composite scores, hip musculoskeletal characteristics, and pitching kinematics in NCAA Division I baseball pitchers.J Sport Rehabil. 2019;28:432-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Endo Y, Sakamoto M. Correlation of shoulder and elbow injuries with muscle tightness, core stability, and balance by longitudinal measurement in junior high baseball players. J Phys Ther Sci. 2014;26:689-693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fortenbaugh D, Fleisig GS, Andrews JR. Baseball pitching biomechanics in relation to injury risk and performance. Sports Health. 2009;1:314-320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ireland ML, Willson JD, Ballantyne BT, Davis IM. Hip strength in females with and without patellofemoral pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2003;33:671-676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kageyama M, Sugiyama T, Takai Y, Kanehisa H, Maeda A. Kinematic and kinetic profiles of trunk and lower limbs during baseball pitching in collegiate pitchers. J Sports Sci Med. 2014;13:742-750. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kantrowitz DE, Trofa DP, Woode DR, Ahmad CS, Lynch TS. Athletic hip injuries in Major League Baseball pitchers associated with ulnar collateral ligament tears. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018;6:2325967118800704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Knapik JJ, Bauman CL, Jones BH, Harris JM, Vaughan L. Preseason strength and flexibility imbalances associated with athletic injuries in female collegiate athletes. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19:76-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Laudner KG, Moore SD, Sipes RC, Meister K. Functional hip characteristics of baseball pitchers and position players. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:383-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McGraw KO, Wong SP. Forming inferences about some intraclass correlation coefficients. Psychol Methods. 1996;1:30-46. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nadler SF, Malanga GA, DePrince M, Stitik TP, Feinberg JH. The relationship between lower extremity injury, low back pain, and hip muscle strength in male and female collegiate athletes. Clin J Sport Med. 2000;10:89-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Orchard J, Best TM, Verrall GM. Return to play following muscle strains. Clin J Sports Med. 2005;15:436-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Posner M, Cameron KL, Wolf JM, Belmont PJ, Jr, Owens BD. Epidemiology of Major League Baseball injuries. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:1676-1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Radwan A, Francis J, Green A, et al. Is there a relationship between shoulder dysfunction and core instability? Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2014;9:8-13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Seroyer ST, Nho SJ, Bach BR, Bush-Joseph CA, Nicholson GP, Romeo AA. The kinetic chain in overhand pitching: its potential role for performance enhancement. Sports Health. 2010;2:135-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Thorborg K, Serner A, Petersen J, Madsen TM, Magnusson P, Holmich P. Hip adduction and abduction strength profiles in elite soccer players: implications for clinical evaluation of hip adductor muscle recovery after injury. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:121-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tippett SR. Lower extremity strength and active range of motion in college baseball pitchers: a comparison between stance leg and kick leg. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1986;8:10-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yanagisawa O, Taniguchi H. Changes in lower extremity function and pitching performance with increasing numbers of pitches in baseball pitchers. J Exerc Rehabil. 2018;14:430-435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yanagisawa O, Wakamatsu K, Taniguchi H. Functional hip characteristics and their relationship with ball velocity in college baseball pitchers. J Sport Rehabil. 2019;28:854-859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zipser MC, Plummer HA, Kindstrand N, Sum JC, Li B, Michener LA. Hip abduction strength: relationship to trunk and lower extremity motion during a single-leg step-down task in professional baseball players. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2021;16:342-349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zou G. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:702-706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]