Abstract

Purified integrase protein (Int) of the conjugative transposon Tn916 was shown, using nuclease protection experiments, to bind specifically to a site within the origin of conjugal transfer of the transposon, oriT. A sequence similar to the ends of the transposon that are bound by the C-terminal DNA-binding domain of Int was present in the protected region. However, Int binding to oriT required both the N- and C-terminal DNA-binding domains of Int, and the pattern of nuclease protection differed from that observed when Int binds to the transposon ends and flanking DNA. Binding of Int to oriT may be part of a mechanism to prevent premature conjugal transfer of Tn916 prior to excision from the donor DNA.

Conjugative transposons such as Tn916 are mobile genetic elements that move between different species and genera of bacteria by a mechanism that requires cell-cell contact (4, 22, 24). They are found in a wide variety of both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria and are responsible for the spread of antibiotic resistance in many gram-positive pathogens. Most conjugative transposons encode resistance to tetracycline, carrying either a tetM or tetQ determinant that confers resistance by a ribosome protection mechanism (28). Many conjugative transposons also encode resistance to other antibiotics. One of the best-studied conjugative transposons is Tn916, which was first isolated from Enterococcus faecalis (8). Tn916 can move between many different gram-positive bacteria, including E. faecalis and Bacillus subtilis, and can transfer from gram-positive bacteria to gram-negative bacteria (18). Tn916 is an 18-kb element containing 24 open reading frames, one of which encodes resistance to tetracycline (tetM) (7).

Conjugative transposition of Tn916 has three stages: excision to produce a circular form of the transposon, conjugal transfer of the excised transposon from donor to recipient, and integration of the transferred transposon into the genome of the recipient (2, 25). Excision requires the activity of the products of two transposon genes, int and xis (19, 20, 29) (Fig. 1). Int is an integrase family recombinase (1). It is a bivalent DNA-binding protein whose C-terminal domain recognizes and binds to imperfect 26-bp repeats at each end of the transposon and to flanking host DNA (12). Its N-terminal domain binds specifically to short repeated sequences (called DR-2 repeats) 150-bp from the left end of the transposon and 90 bp from the right end (5, 12, 32). Int catalyzes DNA cleavage and strand exchange by making staggered cleavages 6-bp apart in the DNA at each end of the transposon to produce 5′ OH termini (14, 31). Following strand exchange, the ends of Tn916 are joined to form the circular intermediate (25). The junction of the circular intermediate contains a 6-bp heteroduplex created by the joining of single stands of the 6-bp sequences, termed coupling sequences (2), that flank the transposon in the donor DNA.

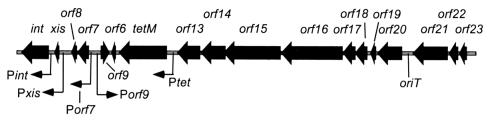

FIG. 1.

Genetic map of Tn916. The gray background line represents transposon DNA, and the thick black arrows represent open reading frames. Four short reading frames, orf24 (to the right of orf23), orf12 (to the right of tetM), orf10 (to the right of orf6), and orf5 (to the right of xis), are not shown. The position of the origin of conjugal DNA transfer, oriT, is indicated between orf21 and orf20. The thin arrows indicate five promoters and their direction of transcription.

Xis is a small, basic sequence-specific DNA-binding protein that binds near the ends of Tn916, close to the binding sites for the N-terminal domain of Int (21). Xis is necessary for excision in vivo and in vitro at physiological salt concentrations (17, 20, 30). The mechanism of action of Xis is not currently understood.

Conjugal transfer of Tn916 requires a series of genes located in the right end of the transposon (orf23 to orf13 in Fig. 1) (26). During conjugal transfer of Tn916, genetic evidence suggests that a single strand is transferred from the donor cell to a recipient cell, where the complementary strand is synthesized (23). Tn916 oriT was identified as a segment of DNA that, when cloned onto a plasmid, results in mobilization of the plasmid by a Tn916 transposon (10). It is located between orf21 and orf20 (Fig. 1). The oriT of Tn916 is presumably where the DNA is nicked to initiate the transfer of a single strand of DNA, although this has not been demonstrated directly.

Expression of the tra genes of Tn916 is dependent on int and occurs from the Porf7 promoter (Fig. 1) (3). This suggests that the tra genes are only expressed upon excision of the transposon. This is consistent with the observation that Tn916, when resident on a nonconjugative plasmid, cannot mobilize the markers associated with the plasmid (6) and implies that conjugal transposition of Tn916 is regulated at the level of excision (15). However, if Int and Xis are expressed from a heterologous promoter, excision occurs at a high frequency but the frequency of conjugal transfer and integration remains unchanged, implying that excision is not sufficient for conjugal transfer to occur and that the transfer step in conjugative transposition might be regulated (16).

We found that within oriT is a DNA sequence that is similar to the DNA at the end of Tn916 to which the C terminus of Int binds. Binding of Int to oriT could prevent transfer of Tn916 and play a role in the regulation of conjugative transposition. We show that Tn916 Int binds specifically to oriT in vitro and that this binding is dependent on both the N terminus and the C terminus of Int.

Tn916 Int binds specifically to oriT.

To assess the ability of Int to bind to oriT, we performed DNase I footprinting experiments. As a probe we used an agarose gel-purified BamHI-SalI restriction fragment containing oriT from plasmid pAM5160 (10). This fragment contains 466 bp of Tn916 DNA containing the entire functional oriT region. In all experiments, the oriT-containing DNA fragment was labeled at the SalI site with [α-32P]dTTP by using DNA polymerase I Klenow exonuclease-negative fragment (Promega). Int was purified as described (31). Footprinting experiments were performed as described by Lu and Churchward (13) except that the reactions were incubated for 1 h prior to DNase I treatment and were not treated with phenol-chloroform following treatment. The concentration of DNase used for all reactions was 1.3 ng/μl.

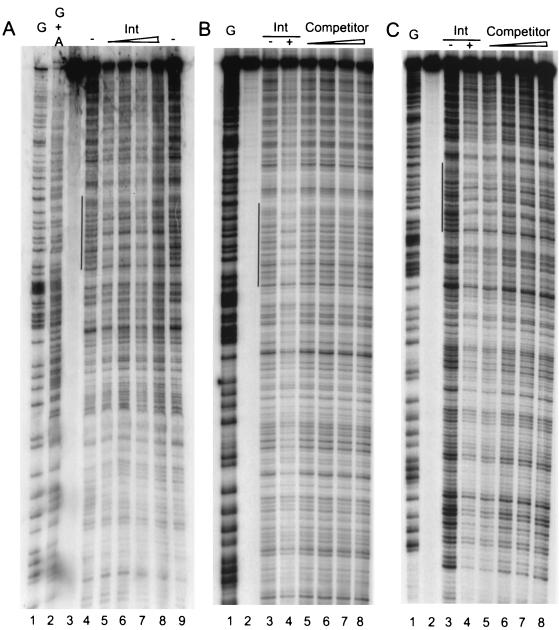

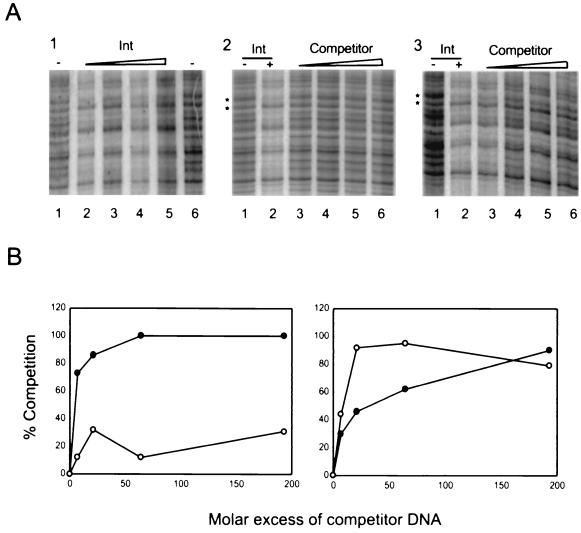

In Fig. 2, lanes 5 to 8 in panel A show that increasing concentrations of Int from 1.3 to 36 ng/μl bound and protected a region of oriT from DNase I digestion. In panel B, lanes 5 to 8 show the effect of unlabeled oriT-containing DNA fragment as a specific competitor. As the concentration of specific competitor was increased in threefold steps to a 200-fold molar excess, binding of Int to the radiolabeled probe decreased. In panel C, lanes 5 to 8 show the effect of increasing amounts of nonspecific competitor using an unlabeled, double-stranded 50-bp oligonucleotide derived from the promoter of a human class II major histocompatibility complex (MHC) gene. There was no effect on binding of Int to the radiolabeled oriT fragment. Apart from the protected region indicated by the vertical lines in Fig. 2, there was no sign of any protection from nuclease cleavage by Int elsewhere in the oriT fragment. Figure 3 shows a quantitation of these results using a phosphoimager. The protected areas of the gels in Fig. 2 are shown in enlarged form in Fig. 3A. For the competitor titrations shown in panels 2 and 3, we determined the ratio of protected to unprotected bands using the bands marked by the upper and lower asterisks, respectively. The results of these comparisons are shown in the left panel of Fig. 3B and clearly demonstrate the effectiveness of the specific competitor DNA fragment in abolishing binding of Int to the radiolabeled oriT fragment.

FIG. 2.

(A) Nuclease protection of radiolabeled oriT DNA by increasing concentrations of Int. Lanes 1 and 2, G− and G+A Maxam-Gilbert sequence reactions. Lane 3, no DNase I. Lanes 4 and 9, DNase I, no Int. Lanes 5 to 8, increasing concentrations of Int. The vertical bar to the left of lane 4 indicates the protected region. (B) Competitor titration using unlabeled oriT fragment as competitor. Lane 1, Maxam-Gilbert G-specific sequence reactions. Lane 2, no DNase I. Lane 3, DNase I, no Int. Lane 4, DNase I, Int, no competitor. Lanes 5 to 8, increasing amounts of competitor DNA. The vertical bar to the left of lane 3 indicates the protected region. (C) Competitor titration using unlabeled nonspecific DNA fragment as competitor. Lane 1, Maxam-Gilbert G-specific sequence reactions. Lane 2, no DNase I. Lane 3, DNase I, no Int. Lane 4, DNase I, Int, no competitor. Lanes 5 to 8, increasing amounts of competitor DNA. The vertical bar to the left of lane 3 indicates the protected region.

FIG. 3.

Quantitation of DNA competitor titrations. (A) Panels 1 to 3 are enlargements of the protected regions from panels A to C of Fig. 2, respectively. Panel A1, lanes 4 to 9 of panel A from Fig. 2. Panel A2, lanes 3 to 8 of panel B from Fig. 2. Panel A3, lanes 3 to 8 of panel C from Fig. 2. The asterisks to left of panels A2 and A3 indicate the bands used for quantitation. (B) Left graph: competitor titration using unlabeled oriT fragment (solid-circles) and nonspecific fragment (open circles). Percent competition was determined by taking the ratio of the protected (upper) band and the unprotected (lower) band. For each competitor concentration, this ratio was then normalized, assuming that the value obtained from lane 1 of panels A2 and A3 with no Int was equal to 100% competition (no binding) and the value from lane 2 of panels A2 and A3 with no competitor was equal to 0% competition. Right graph: competitor titration using Int C-terminus-specific competitor (solid circles) and N-terminus-specific competitor (open circles). Quantitation and analysis were carried out as for the left graph.

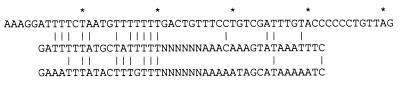

Figure 4 shows an alignment of the region of oriT protected by Int and the joined ends of Tn916 (NNNNNN indicates the variable coupling sequences that flank the transposon in the donor molecule) in either orientation. We have used the joined transposon ends simply as a matter of convenience for the sake of this comparison, although this region of the circular intermediate is protected by Int (B. Limbago and G. Churchward, unpublished data). It appears that the oriT sequence protected by Int contains a segment of DNA that is similar to the transposon ends. The bases denoted by the asterisks are the bases that are left unprotected when Int binds to oriT. Their regular spacing of 11 bases suggests that Int binds to one face of the DNA and thus leaves these bases unprotected from DNase I cleavage (9).

FIG. 4.

Comparison of the Int-protected region of oriT with the ends of Tn916. Upper line: protected oriT sequence. The asterisks indicate unprotected bases (not distance along the sequence). Middle line: joined transposon ends in 5′-to-3′ orientation. Lower line: complementary strand of the joined transposon ends in 5′-to-3′ orientation. Vertical dashes indicate bases in the transposon end sequences that are identical to bases in oriT.

Both the C-terminal and the N-terminal DNA-binding domains of Int are necessary for binding oriT.

In order to determine which domain of Int interacts with oriT, we used double-stranded oligonucleotides that are specific to the N-terminal and the C-terminal domains as competitors in the DNase I protection assays using the same molar excess of competitor as described above. The N-terminus-specific oligonucleotide was DR22, and the C-terminus-specific oligonucleotide was CL (11). Each of these oligonucleotides contains the region protected from nuclease cleavage by the N- and C-terminal domains of Int, respectively. The degree of competition was quantitated as described above. The right panel of Fig. 3B shows that both oligonucleotides abolished binding of Int to oriT when used as competitors. In addition, using DNase I protection, we were unable to see any binding of oriT by either the N-terminal or C-terminal domain of Int alone (data not shown), while these domains protect separate defined regions of the ends of Tn916. We conclude that both the N-terminal and C-terminal DNA-binding domains of Int are necessary for binding to oriT.

Specific binding of Int to oriT.

The results described here show that Tn916 integrase binds specifically to a site within oriT that is similar to the ends of the transposon to which Int also binds (12). Comparing between experiments using different DNA substrates, the apparent affinity of Int for oriT is similar to that for the transposon ends and flanking bacterial DNA. Two protein molecules bearing the C-terminal domain of Int bind to the transposon end and flanking DNA (11). The binding of Int to the site within oriT differs in three ways from binding to the transposon ends. First, although a region of approximately the same length (∼50 nucleotides) is protected in each case, the sequence comparison indicates that this region may only contain a specific binding site for a single Int molecule. Second, there are sites within the protected region of oriT that remain susceptible to DNase I cleavage. In contrast, the sequences at the transposon ends and flanking DNA are completely protected from DNase I cleavage (13). Third, Int binding to oriT is inhibited by oligonucleotides containing specific binding sites for both N- and C-terminal domains of Int, indicating that both domains contribute to the observed protection of oriT. This is despite the fact there are no sequences of DNA within the oriT fragment that are recognizably similar to the DR-2 repeats located near the ends of the transposon to which the N-terminal domain of Int binds (5, 12). In contrast, oligonucleotides containing specific N-terminal domain binding sites do not compete with binding of the C-terminal domain of Int to the transposon ends and flanking DNA (13).

The similarity in size of the protected region within oriT to that at the transposon ends indicates that two Int molecules may bind to oriT. We assume, because of the DNA sequence similarity to the C-terminal domain binding sites at the ends of the transposon, that the primary interaction between Int and oriT DNA occurs through the C-terminal domain of Int. The unprotected sites within this region are spaced almost exactly 11 bp apart, and so we propose that, within oriT, binding of Int occurs to only one face of the DNA molecule (9). We have not observed binding of either the C- or N-terminal domain of Int alone to oriT (data not shown), so it appears that the N-terminal domain of Int is required for this interaction of Int with oriT in some role other than DNA binding. We have observed that the N-terminal domain of Int can form dimeric and tetrameric complexes with segments of DNA containing its specific binding sites, indicating that N-terminal domains of Int can interact with each other (11). The binding of C-terminal domains of Int shows significant positive cooperativity, indicative of interactions between C-terminal domains (11). We therefore propose that binding of Int to oriT involves specific binding of a single Int molecule, with stabilization of a second Int molecule in the complex by primarily protein-protein interactions. According to this model, competition for binding by an oligonucleotide containing the C-terminal binding site is due to saturation of the available binding sites on the C-terminal domains of proteins. Competition for binding by oligonucleotides containing N-terminal binding sites would be due to occupancy of N-terminal domains preventing appropriate protein-protein interactions. Since the solution structures of the N-terminal domain of Int when free and when bound to a 14-bp oligonucleotide containing a single DR-2 repeat are very similar (5, 32), binding of DNA to the intact Int protein seems unlikely to significantly alter the structure of the N-terminal domain of Int unless such alterations require longer segments of DNA containing multiple repeats. However, the properties of Int are hard to predict based on our current understanding of its DNA-binding activities. Although the structural studies show that a monomeric N-terminal domain can form a complex with a single DR-2 repeat (32), a chimeric protein carrying the N-terminal domain of Int fused to maltose-binding protein can interact as a dimer with a DNA molecule containing two DR-2 repeats, but only as a tetramer with DNA molecules containing single DR-2 repeats (11). No complex containing a monomer of the chimeric protein bound to a single DR-2 repeat is observed.

Consequences of Int binding to oriT.

Binding of Int to oriT is probably significant in vivo. Tn916 does not effectively mobilize a nonconjugative plasmid into which it is inserted (6). This can be explained by the observation that int, and thus presumably transposon excision, is required for expression of the transfer genes (3). However, there is apparently nothing to prevent the transfer genes from being expressed if Tn916 inserts downstream of an active transcriptional promoter. Binding of Int to oriT, if it inhibits oriT function, could provide a mechanism to prevent transfer from occuring prior to excision even if the transfer genes are transcribed, thus preventing transfer of only a portion of the transposon to a recipient cell. Int can potentially be expressed from Pint, Pxis, and Porf7 (Fig. 1) (3, 17), and all these promoters are constitutively active in all cells in the population (D. Muller and G. Churchward, unpublished results), indicating that Int is constitutively expressed in all cells, not just the minority of cells that act as conjugal donors of Tn916.

There is an apparent precedent for a direct interaction between the excision and conjugation machinery of a transposable element (27). NBU1, a mobilizable element found in Bacteroides species, encodes an integrase, IntN1, and an Xis-like protein, but these are not sufficient for excision of the element. Excision also requires two other open reading frames and a segment of DNA including the origin of conjugal DNA transfer of the element. When the segment of DNA containing the origin of transfer is cloned on a plasmid, excision of NBU1 is inhibited. This observation has led to the proposal that the origin of transfer and related bound proteins interact with IntN1 and the ends of the element to form a complex competent for excision of the element. In the absence of the origin of transfer or in the presence of multiple copies in the cell that perturb the formation of the putative complex, excision does not occur.

There is no similar requirement for a functional oriT for excision of Tn916 (19, 20), and copies of oriT cloned on a plasmid do not inhibit conjugative transposition of Tn916 (10). However, it may be that under normal conditions, interactions between Int and oriT not only help to prevent premature transfer of Tn916, but also prevent excision from occurring until such time as an appropriate signal, such as the presence of the recipient, is received. The existence of such a mechanism would explain why Int and Xis are expressed constitutively, yet conjugative transposition only occurs in a small fraction, typically 10−4 or less, of the donor cells.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation (MCB 9876427). D. H. was supported in part by a training grant from the National Institutes of Health (T32 AI07470) and a fellowship from the ARCS Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Argos P, Landy A, Abremski K, Egan J B, Haggard-Ljungquist E, Hoess R H, Kahn M J, Kalionis W, Narayana S V L, Pierson L S, Sternberg N, Leong J M. The integrase family of site-specific recombinases: regional similarity and global diversity. EMBO J. 1986;5:433–440. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04229.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caparon M G, Scott J R. Excision and insertion of the conjugative transposon Tn916 involves a novel recombination mechanism. Cell. 1989;59:1027–1034. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90759-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Celli J, Trieu-Cuot P. Circularization of Tn916 is required for expression of the transposon-encoded transfer functions: characterization of long tetracycline-inducible transcripts reading through the attachment site. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:103–117. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clewell D B, Gawron-Burke C. Conjugative transposons and the dissemination of antibiotic resistance in Streptococci. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1986;40:635–659. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.40.100186.003223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Connolly K M, Wojciak J M, Clubb R T. Site-specific DNA binding using a variation of the double stranded RNA binding motif. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;7:546–550. doi: 10.1038/799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flannagan S E, Clewell D B. Conjugative transfer of Tn916 in Enterococcus faecalis: trans activation of homologous transposons. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:7136–7141. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.22.7136-7141.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flannagan S E, Zitzow L A, Su Y A, Clewell D B. Nucleotide sequence of the 18-kb conjugative transposon Tn916 from Enterococcus faecalis. Plasmid. 1994;32:350–354. doi: 10.1006/plas.1994.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gawron-Burke C, Clewell D B. A transposon in Streptococcus faecalis with fertility properties. Nature. 1982;300:281–284. doi: 10.1038/300281a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hochschild A, Ptashne M. Cooperative binding of lambda repressors to sites separated by integral turns of the DNA helix. Cell. 1986;44:681–687. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90833-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jaworski D D, Clewell D B. A functional origin of transfer (oriT) on the conjugative transposon Tn916. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6644–6651. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.22.6644-6651.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jia Y, Churchward G. Interactions of the integrase protein of the conjugative transposon Tn916 with its specific DNA binding sites. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6114–6123. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.19.6114-6123.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu F, Churchward G. Conjugative transposition: Tn916 integrase contains two independent DNA binding domains that recognize different DNA sequences. EMBO J. 1994;13:1541–1548. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06416.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu F, Churchward G. Tn916 target DNA sequences bind the C-terminal domain of integrase protein with different affinities that correlate with transposon insertion frequency. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1938–1946. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.8.1938-1946.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manganelli R, Ricci S, Pozzi G. Conjugative transposon Tn916: evidence for excision with formation of 5′-protruding termini. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5813–5816. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.19.5813-5816.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manganelli R, Romano L, Ricci S, Zazzi M, Pozzi G. Dosage of Tn916 circular intermediates in Enterococcus faecalis. Plasmid. 1995;34:48–57. doi: 10.1006/plas.1995.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marra D, Pethel B, Churchward G, Scott J R. The frequency of conjugative transposition of Tn916 is not determined by the frequency of excision. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5414–5418. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.17.5414-5418.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marra D, Scott J R. Regulation of excision of the conjugative transposon Tn916. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:609–621. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poyart C, Celli J, Trieu-Cuot P. Conjugative transposition of Tn916-related elements from Enterococcus faecalis to Eschericia coli and Pseudomonas fluorescens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:500–506. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.2.500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poyart-Salmeron C, Trieu-Cuot P, Carlier C, Courvalin P. Molecular characterization of two proteins involved in the excision of the conjugative transposon Tn1545: homologies with other site-specific recombinases. EMBO J. 1989;8:2425–2433. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08373.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rudy C, Taylor K L, Hinerfeld D, Scott J R, Churchward G. Excision of a conjugative transposon in vitro by the Int and Xis proteins of Tn916. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4061–4066. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.20.4061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rudy C K, Scott J R, Churchward G. DNA binding by the Xis protein of the conjugative transposon Tn916. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2567–2572. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.8.2567-2572.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scott J R. Conjugative transposons. In: Sonenshein A L, Hoch J A, Losick R, editors. Bacillus subtilis and other gram-positive bacteria. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 597–614. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scott J R, Bringel F, Marra D, Van Alstine G, Rudy C K. Conjugative transposition of Tn916: preferred targets and evidence for conjugative transfer of a single strand and for a double-stranded circular intermediate. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:1099–1108. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scott J R, Churchward G G. Conjugative transposition. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1995;49:367–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.002055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scott J R, Kirchman P A, Caparon M G. An intermediate in the transposition of the conjugative transposon Tn916. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:4809–4813. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.13.4809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Senghas E, Jones J M, Yamamoto M, Gawron-Burke C, Clewell D B. Genetic organization of the bacterial conjugative transposon Tn916. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:245–249. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.1.245-249.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shoemaker N B, Wang G-R, Salyers A A. Multiple gene products and sequences required for excision of the mobilizable integrated Bacteroides element NBU1. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:928–936. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.4.928-936.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Speer B S, Shoemaker N B, Salyers A A. Bacterial resistance to tetracycline: mechanisms, transfer, and clinical significance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1992;5:387–399. doi: 10.1128/cmr.5.4.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Storrs M J, Carlier C, Poyart-Salmeron C, Trieu-Cuot P, Courvalin P. Conjugative transposition of Tn916 requires the excisive and integrative activities of the transposon-encoded integrase. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4347–4352. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.14.4347-4352.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Su A Y, Clewell D B. Characterization of the left 4 kb of conjugative transposon Tn916: determinants involved in excision. Plasmid. 1993;30:234–250. doi: 10.1006/plas.1993.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor K, Churchward G. Specific DNA cleavage mediated by the integrase of conjugative transposon Tn916. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1117–1125. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.4.1117-1125.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wojciak J M, Connolly K M, Clubb R T. Solution structure of the Tn916 integrase-DNA complex: specific binding using a three-strand beta-sheet. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:366–373. doi: 10.1038/7603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]