Abstract

The ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has boosted the development of antiviral research. Microfluidic technologies offer powerful platforms for diagnosis and drug discovery for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) diagnosis and drug discovery. In this review, we introduce the structure of SARS-CoV-2 and the basic knowledge of microfluidic design. We discuss the application of microfluidic devices in SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis based on detecting viral nucleic acid, antibodies, and antigens. We highlight the contribution of lab-on-a-chip to manufacturing point-of-care equipment of accurate, sensitive, low-cost, and user-friendly virus-detection devices. We then investigate the efforts in organ-on-a-chip and lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) synthesizing chips in antiviral drug screening and mRNA vaccine preparation. Microfluidic technologies contribute to the ongoing SARS-CoV-2 research efforts and provide tools for future viral outbreaks.

Key words: Microfluidic, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Lab-on-a-chip, Detection, Organ-on-a-chip, Drug screen

Graphical abstract

Microfluidic technologies play an important role in virus pandemic. This review highlights the applications of microfluidic chip in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 detection and drug discovery.

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has led to an unprecedented worldwide pandemic. The World Health Organization (WHO) data suggests over 600 million confirmed cases and over 6.4 million deaths as of 4 September 2022. Compared with the case fatality rate of the 1918 influenza pandemic (2%) and the 1957 influenza pandemic (0.6%), SARS-CoV-2 is higher (about 3.3%). Furthermore, the spread rate of SARS-CoV-2 is 40-fold higher than that of SARS-CoV, which makes it more difficult to control1. Thus, collaborating measures must be implemented to contain an emerging pandemic virus or slow its spread worldwide.

SARS-CoV-2 is an RNA virus containing a 30 kb genomes, encoding four structural proteins, including the spike protein (S), envelope protein (E), membrane protein (M), and nucleocapsid protein (N)2, 3, 4 (Fig. 1). Viral replication requires other auxiliary genes, including open reading frame 1a (ORF1a), ORF1b, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), and hemagglutinin esterase (HE)3. With the appearance of many variants of SARS-CoV-2, their propagation speed and virulence became more challenging to predict. Therefore, accurate, rapid, long-term detection strategies, frequent updating of therapies, and efficient protection are needed to control the spread of viruses. These require multidisciplinary solutions to achieve coordinated diagnosis and drug discovery5.

Figure 1.

The structure of SARS-CoV-2.

Microfluidic technologies allow processing or manipulating small (10−9–10−18 L) amounts of fluids based on designed channels with dimensions of tens to hundreds of micrometers in the chip6, 7, 8. Many operations like separation, reaction, detection of different ingredients, and culture of cells or tissues can be integrated into miniaturized microscale devices9,10. Microfluidic devices have played an important role in quickly responding to infectious diseases by developing point-of-care devices for accurate and fast diagnosis and constructing instruments to reveal the pathogenic mechanisms and conduct drug screens11, 12, 13. Microfluidic devices can be lab-on-a-chip14,15, organ-on-a-chip9,16,17, and microreactor8,18,19, depending on their application for COVID-19 management. Based on their destination use, microfluidic chips can be manufactured from different types of materials employing diverse fabrication methods. In Table 1, we emphasize the most common materials and fabrication methods used for disposable devices and provide a brief description of the applications, advantages, and disadvantages of each material20, 21, 22, 23. Among them, polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), paper, and polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) are the most common materials employed for SARS-CoV-2 detection and drug discovery.

Table 1.

Summary on the materials of microfluidic devices.

| Material | Application | Fabrication technology | Advantage | Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silicon | Point-of-care diagnostics Organ-on-chip devices | Photolithography Wet and dry etching Electron beam lithography |

Availability, chemical compatibility, thermostability, ease of fabrication, design flexibility, semiconducting properties, possibility of surface modifications | Opacity, relatively high cost |

| Glass | Chemical reactions Synthesis of emulsions Polymeric nanoparticles Optical detection |

Chemically inert, thermostable, electrically insulating, rigid, biologically compatible, allowing easy surface functionalization, higher resolution, thermal and chemical stability | Expensive and complex fabrication | |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) | Organ-on-a-chip Multi-channels Array of a special pattern High-throughput models |

Soft photolithography | Cheap, easy to mold, good for prototyping, presenting optical transparency, gas permeability, biocompatibility, low autofluorescence, natural hydrophobicity, high elasticity. | Non-specific molecule adsorption, absorption of less hydrophobic molecules, incompatibility with many solvents, reagents, release of uncrosslinked small PDMS molecules, high cost. |

| Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) | Organ-on-a-chip Micro-physiological systems |

Embossing Injection Molding Laser ablation |

Better solvent compatibility, no small-molecule absorption, optically transparent, good mechanical properties, allowing surface modification | Poor thermal performance, poor resistance to chemical corrosion, complex processing |

| Perfluorinated polymers | Cell cultures High-precision assays Super-clean tools Valve and pump fabrications Synthesis devices |

Soft lithography | Thermo-processability, chemical inertness, compatibility with organic solvents, excellent antifouling properties | Lack of easy micropatterning and satisfactory elasticity |

| Cyclo-olefin polymers and copolymers (COPs/COCs) | Synthesis devices in which aggressive solvents are employed | Embossing | Optical transparency, enhanced chemical resistance, low water absorptivity, good electrical insulating properties, long-term stability of surface treatments, low level of impurities | Poor flexibility and lowly biocompatible |

| Epoxy resins | Organ-on-a-chip | 3D printing | Enhanced stability at high temperatures, chemical resistance, transparency, very high resolution with small features. | High cost, poor flexibility, oxygen permeability |

| Paper | Rapid point-of-care diagnostic testing and medical screening | Wax patterning Alkyl ketene dimer printing Flexographic printing Shaping/cutting |

Simplicity, accessibility, significant low costs, high porosity, high physical absorption, ease of manipulation and sterilization, potential for chemical or biological modifications, similarity to the native ECM, bio-affinity, biocompatibility, light weights, the ability to operate without supporting equipment, direct and in situ operation | Poor mechanical strength in a wet state, thickness requirements for achieving transparency |

In this review, we discuss the role of microfluidic technology in SARS-CoV-2 detection and drug discovery. Firstly, we reviewed three kinds of COVID-19 diagnosis strategies based on the nucleic acid, antibodies, and antigens of SARS-CoV-2, respectively, and investigated the advantages and disadvantages of those methods. Secondly, we demonstrated organ-on-a-chip's application in studying the molecular mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 and drug screening. Finally, we examined the role of the microfluidic chip in preparing mRNA delivery nanoparticles. In a word, microfluidic technologies offer a great chance to respond to the current COVID-19 pandemic and will play a significant role in future viral outbreaks.

2. Microfluidic technology for SARS-CoV-2 detection

2.1. Nucleic acid detection

Nucleic acid detection is currently the gold standard for SARS-CoV-2 detection of its capacity to measure the viral genomic parts directly. SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid exists in the nasopharyngeal fluids of infected patients, and nucleic acid test helps prevent infectious spread between people and communities24. Traditional methods include quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)25,26, isothermal amplification reaction27, and clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats-associated systems (CRISPR–Cas) technology28, which are used to detect SARS-CoV-2 RNA sequences29. Among them, RT-PCR is the gold standard of nucleic acid detection for COVID-19 diagnosis. The procedure of RT-PCR begins with the isolation and conversion of viral RNA to complementary DNA (cDNA) and then the amplification of cDNA by Taq DNA polymerase. Finally, it ends with the quantification of the viral load. Although RT–PCR serves as a sensitive, precise, and specific viral detection method, limitations of RT–PCR tests still exist, including sample storage, outside aerosol contamination, long waiting time, large-scale instruments, and professional operators24,30.

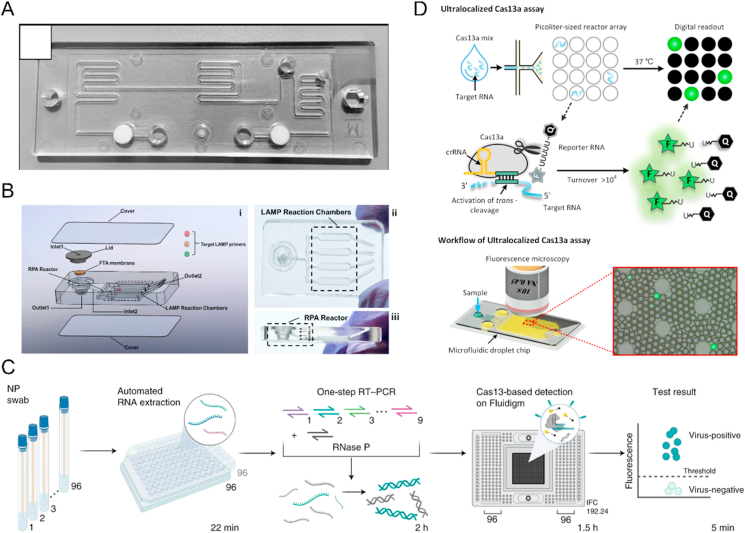

In comparison, microfluidic devices can seal the chips' sample, reagent, and reaction system, dramatically reducing the outside aerosol contamination31,32. In addition, microscale structure on microfluidic chips and fast heat transmission sharply decrease the reaction volume and the thermal cycle time, improving the nucleic acid amplification efficiency33. Furthermore, lab-on-a-chip platforms highly integrate sets of microfluidic elements, which are dedicated to multiple operations of many laborious benchtop protocols without human intervention, thus able to perform complex jobs34,35. For example, a plasmofluidic PCR chip with glass nanopillar arrays and gas-permeable microfluidic channels allows both automatic sample loading and microbubble-free PCR reaction. At the same time, the plasmonic nanopillar arrays result in ultrafast photothermal cycling. PCR results showed 306 s for plasmids expressing SARS-CoV-2 envelope protein, and the amplification efficiency is more than 91% (Table 2)36. Another PCR system, named GeneSoC, has one heater for the reverse transcription (RT) reaction and two heaters for thermal cycling, and two micro blowers at both flow ends for the high-speed shuttle of the PCR solution, which achieves specific gene amplification within 15 min (Fig. 2A) (Table 2)37.

Table 2.

Summary on microfluidic technology for SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid detection.

| Method | Fluid manipulation technique | Material | Immobilized antigen/antibody/gene | Detected biomolecules | Detector | Sensitivity/% | Specificity/% | Sample size/donor/standard | Limit of detection (LOD) | Detection time | Advantage | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanoplasmonic on-chip RT-PCR | Vacuum pump | PDMS | E gene | cDNA | Fluorescence | 91 | – | – | – | 326 s | Rapid, small volume, efficient thermal cycling | 36 |

| GeneSoC | – | – | N gene | cDNA | Fluorescence | 92 | 100 | 66 nasopharyngeal swab samples | 10 copies/reaction | within 15 min | Simplicity and portability, capacity for high-speed and real-time monitoring, and the use of a single disposable tip per analysis. | 37 |

| Microfluidic nano-scale qPCR | – | – | SARS-CoV-1 N gene | cDNA | Fluorescence | 94.50 | 81.30 | 182 clinical NP swab samples | Below 1 copy/μL | – | Ultra-sensitive detection, lower reagent consumption increased throughput, increased precision, increased confidence in test results, and the capacity to simultaneously test for multiple pathogens | 42 |

| Bio-markTM | – | – | SARS-CoV-2 N gene | cDNA | Fluorescence | – | 100 | 20 clinical nasopharyngeal swab samples, 92 + 74 purified RNA samples | 7 copies/reaction | 192 samples in less than 3 h | Analyzing a larger number of reactions per run, making the assay more cost-effective and less time-consuming. | 43 |

| Automated multiplex RT-PCR on chip | Siphon valve | PMMA | SARS-CoV-2 N gene | cDNA | Fluorescence | – | 100 | 29 SARS-CoV-2 samples, and 1572 negative samples | 20 copies/reaction | 57 min | High-throughput sample-to-answer multiplex detection | 33 |

| Fully automated centrifugal RT-LAMP microfluidic system | Automated syringe pumps | PMMA, PDMS | SARS-CoV-2 N, E and ORF1ab genes | cDNA | Fluorescence | – | 100 when 100 copies/μL | – | 2 copies/reaction | Less than 70 min | Fully automated | 44 |

| Centrifugal LAMP microfluidic nucleic acid assay | Centrifugal forces | – | SARS-CoV-2 targeting N and ORF1ab sequence | cDNA | Fluorescence | – | 100 | 54 samples | – | 40 min | Capable of discriminating HCoV-229E, HCoV-OC43, HCoV-NL63, HCoV-HKU1, SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2 simultaneously within 40 min | 45 |

| Two-stage isothermal amplification | Syringe pump | Clear resin | N gene, E gene and Orf1a gene of SARS-CoV-2 RNA | cDNA | Smartphone | – | – | Heat-inactivated SARS-CoV-2 and quantitative PCR control RNA | 100 genome equivalent/mL | 60 min | Simple readout, high sensitivity, and multiple analyte detection | 47 |

| Nucleic acid isothermal amplification analyzer | Centrifugal force | Polycarbonate | N gene | cDNA | Fluorescent detector | – | – | 201 preclinical samples, 14 positive samples, and 614 clinical samples | 50 copies/μL | 90 min | High sensitivity, good specificity, strong robustness, and excellent repeatability | 48 |

| Lateral flow recombinase polymerase amplification assay | Gravitational force | PMMA | N gene, ORF1ab, E gene | cDNA | Naked eye | 97 | 100 | 37 positive samples and 17 negative samples | 1 copy/μL | 30 min | Low-cost, rapid, high specificity and high sensitivity detection | 49 |

| Combines CRISPR-based diagnostics | Syringe pump | – | Spike gene | cDNA | Fluorescent detector | 98.4 | 99 | 2088 patient specimens | 100 copies/μL | 5 h | High-throughput, multiplexed and microfluidic diagnostic | 51 |

| Digital CRISPR/Cas-assisted assay | Pipette | Polycarbonate | N gene | cDNA | Fluorescent detector | – | – | 2 positive samples, 1 negative sample, and influenza sample | 20 genome equivalent/mL | 20 min | Rapid, and high sensitivity detection without RNA extraction | 50 |

| Electric field-driven microfluidics for rapid CRISPR-based diagnostics | Isotachophoresis | Glass | N gene, E gene, Rnase P gene | cDNA | Inverted epifluorescence microscope | – | 96.9 | 40 negative swab samples | 10 copies/μL | 35 min | Minimal consumption of reagents, and rapid detection | 52 |

| RNA-triggered Cas13a catalysis system | Syringe pump | PDMS | Open reading frame 1a (O) gene and nucleocapsid (N) gene | cDNA | Fluorescence microscopy | – | 100 | SARS-CoV-2 RNA | 6 copies/μL | 60 min | Avoiding the need for expensive thermocyclers and professional technicians, simplicity, single-molecule quantitation capability, and broad applicability | 53 |

| Droplet digital PCR platform | Pipette | Polypropylene | N gene, ORF1ab | cDNA | A smartphone and a portable trans-illuminator | – | – | Template sample | 3.8 copies/20 μL | 90 min | Low-cost, and rapid detection without bulky and expensive micropumps and optical detectors | 54 |

| Direct reverse-transcription-loop-mediated isothermal amplification | Syringe pump | PMMA | As1e, N, and E genes | cDNA | A smartphone with a 488 nm LED light | – | – | 4 clinical respiratory virus samples | 20 copies/μL | 33 min | High sensitivity, accuracy, low-cost, and rapid detection | 55 |

| Amplification-free CRISPR/Cas12a-based diagnostic technology | Pipette | PMMA | ORF1ab gene | cDNA | Smartphone | – | 100 | 11 samples from BEI resources | 50 copies/μL | 71 min | Visible readout, amplification-free detection without using any optical hardware | 56 |

‒, not applicable.

Figure 2.

Example of microfluidic technology for SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid detection. (A) A high-speed but low-throughput RT-qPCR system for the detection of SARS-CoV-2. Reprinted with the permission from Ref. 37. Copyright © 2021 Elsevier. (B) A 3D printed integrated microfluidic chip for multiplexed colorimetric detection of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater. Reprinted with the permission from Ref. 47. Copyright © 2020 Elsevier. (C) Multiplexed CRISPR-based microfluidic platform for identification of SARS-CoV-2 variants. Reprinted with the permission from Ref. 51. Copyright © 2022 Springer Nature. (D) An ultralocalized Cas13a assay enables universal and nucleic acid amplification-free single-molecule RNA diagnostics. Reprinted with the permission from Ref. 53. Copyright © 2021 American Chemical Society.

Although qRT-PCR provides acceptable sensitivity for early infection identification, the possibility of false-negative or false-positive findings is one of the most critical clinical factors for pandemic transmission38. Such findings occur when the viral content is low, as evident in asymptomatic or weakly positive individuals39. Henceforth, timely diagnosis is required to avoid such outcomes40,41. Xie et al.42 developed a three-step microfluidic qPCR method that could incorporate reverse transcription and targeted cDNA pre-amplification to address the issue of false-negative results while simultaneously keeping high sensitivity in the RT-PCR technique. They could enable detection below 1 copy/μL as a nanoscale PCR method (Table 2). Fassy et al.43 also included the pre-amplification step enabling the detection of seven transcript copies per reaction for N genes (Table 2). Moreover, as the integration, simplicity, bubble easy removal, and hundreds of individual units driven by a single spindle motor, centrifugal microfluidic technology has been widely used in SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid amplification reaction (Table 2)33,44,45.

Unlike RT-PCR, isothermal amplification reaction does not need heating or cooling, simplifying the outside condition. Among them, loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) technology has high sensitivity, rapid response speed, simple operation, and easy readout46. More and more methods based on LAMP and microfluidic chips for SARS-CoV-2 detection have been established. For example, a device integrated nucleic acid extraction, two-stage isothermal amplification, and colorimetric detection on the chip to achieve sensitive multiplexed colorimetric detection. The authors detected SARS-CoV-2 with sensitivities of 100 genome equivalent (GE)/mL and 500 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL, respectively, in wastewater within 1 h (Fig. 2B) (Table 2)47. Other isothermal amplification methods, including nucleic acid sequence-based amplification (NASBA) (Table 2)48 and recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA) (Table 2)49, have been integrated with lab-on-a-chip and used to detect SARS-CoV-2 pathogens.

With the rise of CRISPR–Cas technology in nucleic acid sensing and infectious pathogens diagnosis, more and more studies have proved its elegant detection mechanism, including fast assay time and low reaction temperature50. Such devices are further integrated with microfluidic technology to achieve more powerful detection. A cost-effective virus and variant detection platform, which combines CRISPR-based diagnostics and commercially available Fluidigm microfluidics with a streamlined workflow for clinical use, performed on 525 patient specimens in an academic setting and 166 specimens in a clinical setting. Besides, the platform also enables the identification of 6 SARS-CoV-2 variant lineages, including Delta and Omicron, and evaluated it on 2088 patient specimens, which achieved high-throughput surveillance of multiple viruses and variants simultaneously (Fig. 2C) (Table 2)51. Similarly, to integrate commercially available microfluidic digital chip with CRISPR/Cas12a-assisted RT-PCR, the assay achieved rapid detection: within 15 min for qualitative detection and 30 min for quantitative detection. It also showed a high signal-to-background ratio, broad dynamic range, and high sensitivity—down to 1 genome equivalent (GE)/μL of SARS-CoV-2 RNA and 20 GE/μL of heat-inactivated SARS-CoV-2 (Table 2)50. A selective ionic focusing technique based on an appropriate electric field gradient and a microfluidic chip was utilized to purify target RNA from raw nasopharyngeal swab samples automatically. It detected SARS-CoV-2 RNA in about 35 min by LAMP and CRISPR-Cas12 assay from both contrived and clinical nasopharyngeal swab samples (Table 2)52. For droplet microfluidics, the RNA-triggered Cas13a catalysis system in cell-like-sized droplet reactors enhanced target and local reporter concentrations simultaneously. It achieves >10,000-fold enhancement in sensitivity compared to the bulk Cas13a assay and enables absolute digital single-molecule RNA quantitation (Fig. 2D) (Table 2)53.

More and more researchers have combined microfluidic devices with smartphones to achieve automated image analysis free of optical detectors. Chen et al.54 used a flattened pipette tip with an elliptical cross-section, which extended a high aspect-ratio microfluidic chip design to pipette scale for rapid (<5 min) generation of several thousand monodispersed droplets for digital PCR. A smartphone can image positive droplets, and the detection of limit is 3.8 copies per 20 μL (Table 2). Nguyen et al.55 developed an internet of things-based device that could complete a series of operations on a miniaturized chip (Table 2). The results were processed by a microprocessor and displayed on the phone. The method based on RT-LAMP achieved a limit of detection of 20 genome copies/μL, and the clinical sample of SARS-CoV-2 was successfully analyzed with high sensitivity and accuracy. Yin et al.47 integrated RPA and LAMP on a 3D-printed microfluidic chip, and by taking advantage of smartphone connectivity, test results could be reported and tracked. Silva et al.56 presented a cellphone-based amplification-free system with CRISPR/CAS-dependent enzymatic (CASCADE) assay. It relied on mobile phone imaging of a catalase-generated gas bubble signal within a microfluidic channel and achieved high accuracy (AUC = 1.0; CI: 0.715–1.00) (Table 2).

Paper-based POC tests also play a crucial role in the current COVID-19 pandemic. Considering the strength of paper, it has been widely used to develop paper-based devices for SARS-CoV-2 detection. Among these, Lateral flow assay (LFA) is a highly mature paper-based diagnostic technology. Researchers and manufacturers have invested the most effort and cost in developing COVID-19 diagnostic kits using LFA57. The conventional LFA test detects the target molecule on an absorbent membrane with detection molecules aligned to form the test and control lines. The signal is analyzed qualitatively in a visual or semi-quantitative reading, a very simple, rapid, and portable analytical platform58. In 2000, Wang et al.59 designed an amplification-free nucleic acid immunoassay, implemented on a lateral flow strip for the fluorescence detection of SARS-CoV-2 ORF1ab, E, N gene in less than 1 h and achieved 100% of sensitivity and 99% specificity. In the same year, Zhu et al.60 devised a multiplex RT-LAMP coupled with a nanoparticle-based lateral flow biosensor. Limit of detection (LOD) was 12 copies per reaction, and the sensitivity and specificity of SARS-CoV-2 ORF1ab and N gene were 100%. Subsequently, a lateral flow-based RT-LAMP detection of SARS-CoV-2 using enzymatic incorporation of biotin-labeled dUTP enhanced the sensitivity and decreased the detection time to 15 min61. In 2022, Li et al.62 integrated isothermal amplification, CRISPR cleavage, and lateral flow detection in a single closed microfluidic platform, enabling contamination-free visual detection and achieving excellent sensitivity (94.1%), specificity (100%) and accuracy (95.8%) for COVID-19 samples.

2.2. Antibody detection

Although RT-PCR is the gold standard for COVID-19 identification, it could not provide evidence of past infection, as nucleic acid only increases highly at acute stage63,64. On the contrary, serological assays detecting antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 not only indicate the previous infection but also help to track the immune response of the host65,66. Furthermore, serological analysis is an effective supplement to nucleic acid testing in COVID-19 epidemiological studies and vaccine development67,68. Traditional methods for COVID-19 management, including enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) and chemiluminescent immunoassays (CLIA), are currently available. However, ELISA and CLIA depend on large laboratory instruments, professional skills, and complex operation69. A large amount of sample and reagent consumption also increases the cost of tests. Compared with the methods above, serological assays based on lab-on-a-chip achieve more convenient and rapid detection of COVID-19-associated antibodies.

Lab-on-a-chip assays, which allow a high degree of integration of all operations of the conventional laboratory on micro-size chips, have performed user-friendly assays for COVID-19 antibodies analysis. The essential step to complete multiple actions independently is reagent storage on the chip. Yafia et al.70 introduced the microfluidic chain reaction (MCR) as the conditional, structurally programmed propagation of capillary flow events (Table 3). With MCR, the authors automated a protocol for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies detection in saliva by continuous subsampling and analysis of coagulation-activated plasma with parallel operations, including timers, iterative cycles of synchronous flow, and stop-flow operations. Another assay introduced a device fabricated by inkjet printing antibodies detection reagent as stable and spatially discrete capture spots. It is an entirely self-contained immunoassay platform and dramatically simplifies the detector design and assay readout (Fig. 3A) (Table 3)71.

Table 3.

Summary on microfluidic technology for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies detection.

| Method | Fluid manipulation technique | Material | Immobilized antigen/antibody/gene | Detected biomolecule | Detector | Sensitivity/% | Specificity/% | Sample size/donor/standard | Limit of detection (LOD) | Detection time | Advantage | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monolithic chips integrating a microfluidic chain reaction | Paper capillary pump | Transparent resin | N | Anti-N Abs | Naked eye or smartphone integrated with a folded origami box | – | – | – | 0.3 ng/mL | – | Frugal, versatile, bona fide lab-on-a-chip, sensitive, quantitative and reproducible. | 70 |

| Microfluidic DA-D4 point-of-care test (POCT) | Pipette pump | POEGMA | S1, N, RBD | Anti-S1, anti-N, anti-RBD Abs | Fluorescent detector | 100 (anti-S1 &anti-RBD) 96.3 (anti-N) | 100 | 46 plasma samples from 31 positive patients and 41 negative samples. | 0.12 ng/mL | 60 min | Easy to use, quantitative, high specificity and sensitivity, capable of measuring antibody kinetics and seroconversion directly from unprocessed blood or plasma, capable of detecting IP-10, low sample volume requirement, low cost. | 71 |

| Microfluidic nanoimmunoassay platform based on MITOMI | Pneumatic valves | PDMS | His-tagged S | Anti-S IgG | Nikon ECLIPSE Ti microscope equipped with a LED fluorescent excitation system and a Cy3 filter set | 98 | 100 | 289 positive and 134 negative samples | 1 nmol/L IgG | – | High sensitivity and specificity, high-throughput, negligible reagent consumption, ultra-flow volume blood sampling | 72 |

| Semi-automatic serological assay | Valve pump | PDMS | S, S1, RBD and N | Anti-S/S1/RBD/N IgG/IgN | Inverted fluorescence microscope | 95 | 91 | 100 serum samples from 66 positive patients | 1.6 ng/mL | 2.6 h | Low-cost, low sample/reagent consumption, multiple analyte detection, and high throughput. | 73 |

| Single molecule arrays | Commercial products | Commercial products | S ligated micron-sized beads | Anti-S Abs | Simoa HD-1 analyzer | – | – | 28 plasma samples from 10 positive patients | – | – | High throughput, rapid detection, and high specificity | 74 |

| An immunoassay based on dual-encoded beads and rolling circle amplification | Syringe pump | PDMS | S, N, RBD | Anti-S, anti-N, anti-RBD Abs | Fluorescent detector | 100 | 100 | 11 positive samples and 11 negative samples | – | – | High throughput, high sensitivity, tunable detection range | 75 |

| Decentralized, instrument-free microfluidic device | Capillary force | PDMS | S-RBD ligated magnetic beads, secondary Abs against human IgG ligated polystyrene beads | Anti-S RBD IgG | Direct visual inspection | 99 | 100 | 91 vaccinees | 13.3 ng/mL | 20 min | High specificity, low-cost, user-friendly interfaces, power-free operation, and quantification by visual inspection | 76 |

| Sandwich-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay on electrodes | DC pump | Grey resin | S1, N, RBD | Anti-S1, anti-N, anti-RBD Abs | Electrochemical biosensors | 100 | 100 | 3 saliva samples from actively infectious patients | 2.3 copies/μl | 50 min | Low-cost, self-contained, simple and sensitive readout for both viral RNA as well as host antibodies, and user-friendly | 77 |

‒, not applicable.

Figure 3.

Example of microfluidic technology for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies detection. (A) A point-of-care test for multiplexed, quantitative serological profiling of COVID-19. Reprinted with the permission from Ref. 71. Copyright © 2021 American Association for the Advancement of Science. (B) A high-throughput microfluidic nano immunoassay for detecting anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. Reprinted with the permission from Ref. 72. Copyright © 2021 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. (C) Microfluidic particle dam for direct visualization of SARS-CoV-2 antibody levels. Reprinted with the permission from Ref. 76. Copyright © 2022 American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Microfluidic technology also supports high-throughput analysis to facilitate large-scale detection of SARS-CoV-2. A microfluidic nano immunoassay for detecting anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies in 1024 samples per device is a low-cost, ultralow-volume whole blood sampling method based on two commercial devices and repurposed a blood glucose test strip. The glucose test strip permits the collection, shipment, and analysis of 0.6 μL of whole blood easily obtained from a simple finger prick. The microfluidic device is a standard two-layer PDMS device consisting of a flow and a control layer. Fluids in the flow layer can be manipulated with pneumatic valves formed by the control layer. The device contains 1024-unit cells, each consisting of an assay and a spotting chamber (Fig. 3B) (Table 3)72.

Similarly, a high-throughput microfluidic device can parallel assess the reactivities of four kinds of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies from up to 50 sera samples. The device contains an array of 200 microchambers (4 rows and 50 columns) with a volume of 5.5 nL each. Each microchamber was surrounded by valves and a button valve in the center. All the reagents were loaded into microchambers by valve control and automated computer operation. The assay achieved a sensitivity of 95% and a specificity of 91% (Table 3)73. Gilboa et al.74 used Single Molecule Arrays (Simoa) to develop an assay to assess antibody neutralization with high sensitivity and multiplexing capabilities based on antibody-mediated blockage of the ACE2-spike interaction (Table 3). The assay did not require live viruses or cells and could be performed in a biosafety level 2 laboratory within 2 h. Our group75 also reported a multiplexed strategy for chip-based sandwich immunoassays integrated with color/size dual-barcoded beads and rolling circle amplification, which achieved simultaneous antibodies and inflammatory biomarkers detection, with the detection range spanning 10 orders of magnitude (Table 3).

Furthermore, detection based on chips permits direct readout without relying on any detection module like a decentralized, instrument-free microfluidic device that directly visualizes SARS-CoV-2 antibody levels. Magnetic microparticles (MMPs) and polystyrene microparticles (PMPs) can bind to SARS-CoV-2 antibodies simultaneously. In a microfluidic chip, this binding reduces the incidence of free PMPs escaping from magnetic separation and shortens PMP accumulation length at a particle dam. This visual, quantitative result enables application in either sensitive mode or rapid mode (Fig. 3C) (Table 3)76. Additionally, simultaneous detection of the RNA of SARS-CoV-2 and serological host antibodies to the virus would facilitate the determination of the immune status of COVID-19 patients. A 3D-printed microfluidic chip that simultaneously detects SARS-CoV-2 RNA in saliva and anti-SARS-CoV-2 immunoglobulins in saliva or blood plasma via multiplexed electrochemical outputs within 2 h. Low-cost point-of-care microfluidic electrochemical sensors for performing multiplexed diagnostics would facilitate the widespread monitoring of COVID-19 infection and immunity (Table 3)77.

Under an urgent need to develop a sensitive and specific assay for rapid detection of antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 infection within minutes, especially in medically underserved areas, readout enabled by a smartphone is more popular and valuable. An electrochemical method based on aerosol jet nano-printed reduced-graphene-oxide-coated 3D electrodes and smartphone-assisted readout achieved a limit-of-detection of 2.8 × 10−15 and 16.9 × 10−15 mol/L of S1 and RBD antibodies78. Another electrochemical capillary-flow immunoassay can quantify IgG antibodies targeting anti-N antibodies down to 5 ng/mL in 10 μL of human whole blood samples in under 20 min. The device can be coupled to a near-field communication potentiostat operated from a smartphone, confirming its true POC potential79. Moakhar et al.80 reported a cost-effective multiplexed fluidic device (NFluidEX), which integrated nano gold electrodes, a multiplexed fluidic-impedimetric readout, built-in saliva collection/preparation, and smartphone-enabled data acquisition and interpretation. It achieved 100% sensitivity and 100% specificity for RBD IgG and IgM.

LFA was also used to detect SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. Chen et al.81 reported a lateral flow immunoassay(LFIA) that uses lanthanide-doped polystyrene nanoparticles (LNPs). Feng et al.82 used lanthanide, Eu(III) fluorescent microsphere to determine the solid phase immunochromatographic assay. It could detect anti-SARV-CoV-2 IgG within 10 min. However, these methods were qualitative/semi-quantitative analyses. To further improve the sensitivity, Zhou et al.83 prepared highly luminescent quantum dot nanobeads (QBs) by embedding numerous quantum dots into a polymer matrix and then applied it as a signal-amplification label in LFIA. It allowed one order of magnitude improvement in analytical sensitivity compared to conventional gold nanoparticle-based LFIA. Moreover, Chen et al.84 developed an ultra-sensitive surface-enhanced Raman scattering-based LFIA strip for simultaneous detection of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgM and IgG. It used gap-enhanced Raman nanotags, in which 1-nm gaps between the core and shell produced the “hot spots” and provided about 30-fold enhancement compared to conventional nanotags.

2.3. Antigen detection

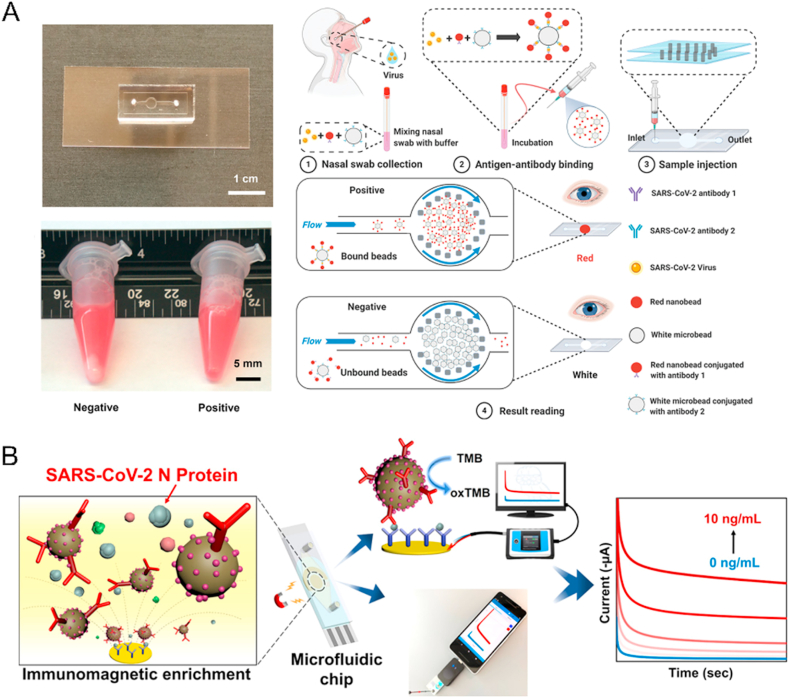

Because of the kinetics of antibody production in the body, serological antibodies need at least a week to reach a detectable concentration85, which cannot quickly respond to the SARS-CoV-2 infection. Direct detection of viral antigens provided rapid evidence for COVID-19. Many microfluidic devices have enabled rapid, low-cost, and high-sensitive self-testing of SARS-CoV-2 antigens—a handheld microfluidic filtration platform combined ultrahigh throughput hydrodynamic filtration and sandwich immunoassay. The immunoassay used nano and microbeads to capture SARS-CoV-2 N proteins and exhibited high throughput separation (<30 s) and a low limit of detection (LOD) < 100 copies/mL (Fig. 4A) (Table 4)86. A microfluidic magneto immunosensor based on a unique sensing scheme, utilizing dually-labeled magnetic nanobeads for immunomagnetic enrichment and signal amplification, can detect SARS-CoV-2 N antigen at 50 pg/mL in whole serum and 10 pg/mL in 5 × diluted serum (Fig. 4B) (Table 4)87.

Figure 4.

Example of microfluidic technology for SARS-CoV-2 antigens detection. (A) The handheld microfluidic filtration platform enables rapid, low-Cost, and robust self-testing of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Reprinted with the permission from Ref. 86. Copyright © 2021 John Wiley and Sons. (B) Microfluidic magneto immunosensor for rapid, high sensitivity measurements of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein in serum. Reprinted with the permission from Ref. 87. Copyright © 2021 American Chemical Society.

Table 4.

Summary on microfluidic technology for SARS-CoV-2 antigens detection.

| Method | Fluid manipulation technique | Material | Immobilized antigen/antibody/gene | Detected biomolecule | Detector | Sensitivity/% | Specificity/% | Sample size/donor/standard | Limit of detection (LOD) | Detection time | Advantage | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Handheld microfluidic filtration platform | Hand-held syringe | PDMS | Monoclonal antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 S and N protein | SARS-CoV-2 | Naked eye detection | 95.4 and 100 | 100 | 93 nasal swab samples | <100 copies/mL | 15–30 min incubation | Without dependence on a fluorescence or optoelectronic detector, fast, naked-eye visible results, robust and easy operation | 86 |

| microfluidic Magneto immunosensor | Syringe pump | PET, PMMA | Capture antibodies against N protein | SARS-CoV-2 N protein | Electrochemical measurements | NR | – | 11 samples | 10 pg/mL | <1 h | Minimal sample and reagent consumption, simplified sample handling, and enhanced detection sensitivity | 87 |

| Serological assay and antigen assay biosensing on chip | Centrifugal force | – | SARS-CoV-2 N/RBD or anti-SARS-CoV-2 | SARS-CoV-2 antibodies or antigens | Chemilumine scence | 98–100 | 84–98 | 135 serum samples and 147 nasopharyngeal specimens | – | 6 samples in 30 min | The first POCT technology using a consumer electronics device, coupling serological and viral antigen testing in parallel to detect respiratory infections | 88 |

| A portable microfluidic chemiluminescent ELISA technology | Liquid pump | Polystyrene | SARS-CoV-2 antibodies against S1 and N | SARS-CoV-2 S1 and N protein | Chemiluminescence | 75 | 100 | 19 patient samples and the two negative controls | 2 ng/mL for IgG, 4 pg/mL and 62 pg/mL for S1 and N protein | 15 min for antibody and 40 min for antigen | Rapid, sensitive, and quantitative analysis of COVID-19 related markers | 89 |

‒, not applicable.

Parallel viral antigen and antibody analysis is a fast and robust all-in-one point-of-care strategy for multiplexed detection of respiratory infections. A biosensing approach consists of a functionalized polycarbonate disc-shaped surface with microfluidic structures, where specific bio-reagents are immobilized in microarray format, and a portable optoelectronic analyzer. The device was used to quantify the concentration of viral antigens and specific immunoglobulins G and M for SARS-CoV-2 using 30 μL of a sample in 30 min (Table 4)88. Similarly, a portable microfluidic ELISA technology profiled anti-SARS-CoV-2 S1 IgG in human serum with only 8-μL sample volume and accurately detected SARS-CoV-2 antigens (S1 and N proteins) with pg/mL level sensitivities in 40 min (Table 4)89. The versatility of the POCT device paves the way for detecting other pathogens and analytes in the incoming post-pandemic world.

Deep-learning (DL)-based image processing has been combined with a smartphone to apply SARS-CoV-2 antigen detection. Shokr et al.90 employed adversarial neural networks with conditioning to develop an easy-reconfigurable virus diagnostic platform that leveraged a smartphone-taken microfluidic chip photos dataset to generate image classifiers for different target pathogens on-demand rapidly. The generalizability of the system was confirmed by rapid reconfiguration to detect SARS-CoV-2 antigens in nasal swab samples (n = 62) with 100% accuracy. As SARS-CoV-2 can spread through bioaerosol, Kim et al.91 proposed a handheld, rapid, low-cost, smartphone-based paper microfluidic assay capable of directly detecting SARS-CoV-2 in the droplets/aerosols from the air without the need for air samplers and long collecting time.

LFAs have also been widely used in SARS-CoV-2 antigens detection. In 2021, Wang et al.92 developed a magnetic quantum dot-based dual-mode LFIA biosensor for the high-sensitivity simultaneous detection of SARS-CoV-2 S and NP antigens, and LODs achieved 1 and 0.5 pg/mL, respectively. In 2022, Peng et al.93 reported an immunoassay based on colloidal gold nanoparticles for rapid NP antigen detection. The sensitivity was improved through copper deposition-induced signal amplification, and three orders of magnitude promoted the LOD to 10 pg/mL after copper deposition signal amplification.

In conclusion, microfluidic technology has been broadly used for SARS-CoV-2 detection. Although several commercial products have appeared in the market, there is still a gap between scientific research and commercialization as their temporarily poor stability and high cost. Development of higher throughput, cheaper, more targets, and automated systems are common goals to address the current COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, the detection sensitivity and speed need to be improved according to more novel designs and more straightforward processes, especially to omit the sample pretreatment procedure. Additionally, the generation of machine learning, mobile networks, and artificial networks would also help to boost the development of SARS-CoV-2 detection methods.

3. Microfluidic technology for COVID-19 drug discovery

3.1. Organ-on-a-chip for mimicking SARS-CoV-2 infection and drug screen

The current COVID-19 pandemic has harmed the whole world. It is significant to explore the mechanism of how SARS-CoV-2 injures the immune system and each organ and further develop more efficient drugs for COVID-19 treatment. Nowadays, cell lines (e.g., human airway epithelial cells and Vero E6 cells) and animal models (such as rhesus macaques and cynomolgus macaques) are mainly used to study the pathogenesis mechanism of viruses and drug testing94, 95, 96, 97. However, their biological structures and functions could not mimic the actual viral response in the human body, thus not the same compared with humen12. Organoid technology has been a helpful tool and could facilitate COVID-19 drug screen. Organoids, induced by pluripotent stem cells, embryonic progenitors, and organ-specific adult stem cells, consist of multiple tissue-specific cell types and present similar organization of cells as well as crucial tissue-specific functions compared with their in vivo correspondents98,99. Thus, organoids can provide the virus with a more natural environment and virus-host interactions in vivo, better to access drug responses in 3D microenvironment100,101.

However, organoids still have some limitations, including incomplete tissue microenvironment, incomplete maturation, and presence of the often-used Matrigel, and lack of crosstalk between different organs102. Organoids incorporated with the microfluidic systems can optimize the organoid culture environment and improve the simulation. The organ-on-a-chip system combines the development of organoid culture, tissue engineering, microfluidic chip design, and micro-electromechanical system assistance, including single or multiple organoids13. Besides, flow in microchannels mimics the blood circulation in vivo, providing a dynamic culture condition instead of a traditional static state. Furthermore, high-throughput performance and low-volume reaction allow larger-scale drug testing incorporating drug gradient and dose studies on organ chips103.

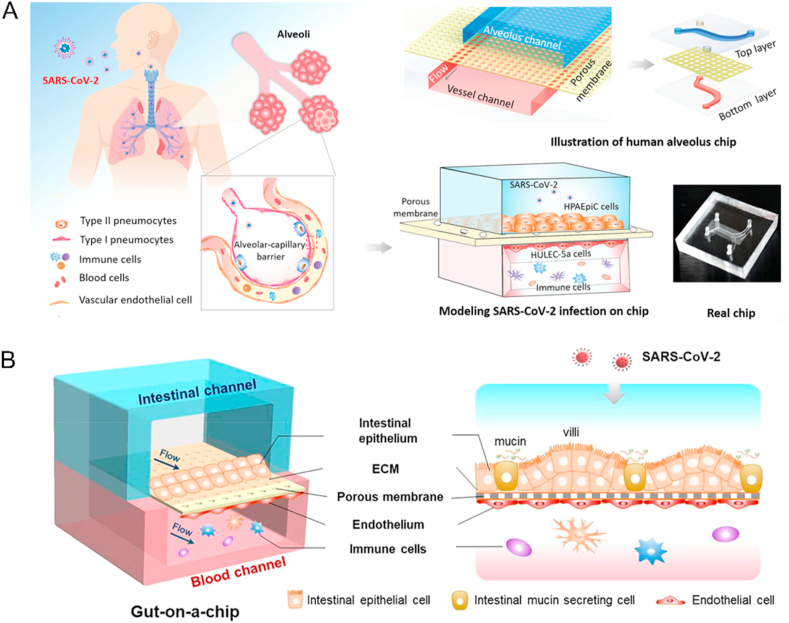

As the most susceptible organ to SARS-CoV-2, the lung and airway organ systems are common objectives for virus pathological studies. A human alveolar chip cocultured human alveolar epithelium, microvascular endothelium, and circulating immune cells under fluidic flow to recapitulate lung injury and immune responses induced by SARS-CoV-2. They proved that viral infection caused immune cell recruitment, endothelium detachment, and increased inflammatory cytokines release (Fig. 5A) (Table 5)104. As the only US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drug for treating COVID-19105, remdesivir was proven to inhibit viral replication and alleviate barrier disruption on chips. On the other hand, Thacker et al.106 used a vascularized lung-on-chip model and found that rapid endotheliitis and vascular damage characterized SARS-CoV-2 infection (Table 5). They validated that inhibition of IL-6 signaling with tocilizumab reduced but did not prevent loss of barrier integrity. Thus, SARS-CoV-2-mediated endothelial cell damage occurred independently of the cytokine storm. Another microfluidic bronchial-airway-on-a-chip lined by human bronchial-airway epithelium and pulmonary endothelium can model viral infection, strain-dependent virulence, cytokine production, and the recruitment of circulating immune cells. In the chips infected with SARS-CoV-2, clinically relevant doses of the antimalarial drug amodiaquine inhibited infection. However, clinical doses of hydroxychloroquine and other antiviral drugs did not inhibit the entry of SARS-CoV-2 in cell lines under static conditions (Table 5)107. However, the above lung models lack a microvascular network to investigate viral infectivity and infection-induced thrombotic events. Jung's team108 developed two novel and vascularized lower respiratory tract multi-chip models for the alveoli and the small airway based on a high throughput, 64-chip microfluidic plate-based platform (Table 5). They demonstrated the physiologically relevant cellular composition, architecture, and perfusion of the vascularized lung tissue models. The platforms will enable the development of respiratory viral infection and disease models for research investigation and drug discovery.

Figure 5.

Example of organ-on-a-chip for SARS-CoV-2 drug screening. (A) The biomimetic human disease model of SARS-CoV-2-induced lung injury and immune responses on organ chip. Reprinted with the permission from Ref. 104. Copyright © 2020 John Wiley and Sons. (B) SARS-CoV-2 induced intestinal responses with a biomimetic human gut-on-chip. Reprinted with the permission from Ref. 110. Copyright © 2020 Elsevier.

Table 5.

Summary on organ-an-a-chip for mimicking SARS-CoV-2 infection and drug screen.

| Material | Fabrication method | Organ type | Key finding | Limitation | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDMS | Soft lithographic | Lung | Treatment with remdesivir can inhibit viral replication and alleviate barrier disruption on chip | Use of only one cell type of alveolus epithelium and assess of only one type of antiviral candidates | 104 |

| PDMS | Soft lithographic | Lung | Rapid endotheliitis and vascular damage characterize SARS-CoV-2 infection | Lack of a complete recapitulation of resident innate immunity and the absence of an adaptive immune response and other cell types necessary for the complete recapitulation of vascular function | 106 |

| PDMS | Soft lithographic | Airway | Amodiaquine inhibited SARS-CoV-2 infection, but hydroxychloroquine did not. | Not use of native SARS-CoV-2 in BSL3 laboratories | 107 |

| Commercial device | Commercial device | Respiratory epithelial tissue | Models can recapitulate key, essential epithelial–capillary interactions specifically observed from in vivo pulmonology. | Timeline limit of three weeks | 108 |

| PDMS | Soft lithographic | Gut | In regard to the brain endothelium, the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein induced destabilization of the BBB, promoted a pro-inflammatory status but did not appear to alter cell viability acutely | Use of immortalized intestinal epithelial cell lines and lack of a comprehensive study on the complex responses of the immune cells involved in the host-virus interactions in this gut-on-a-chip system | 110 |

| PDMS | Soft lithographic | Blood–brain barrier | Introduction of spike proteins to in vitro models of the blood–brain barrier (BBB) showed significant changes to barrier properties | Ignorance on how permeability dynamics may change once these 3D microfluidic constructs are used with the whole SARS-CoV-2 virus | 111 |

| PDMS | Soft lithographic | Vasculature | Identification and inhibition of patient blood-specific coagulation in response to spike mutation or SARS-CoV-2 | – | 112 |

| PDMS polystyrene | Soft lithographic Hot-embossing |

Vasculature | Identification of angiopoietin-1-derived peptide as a therapeutic for SARS-CoV-2-induced inflammation | Use of HUVEC to understand SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis while some studies have shown that endothelial cells may not be the primary target of SARS-CoV-2 infection in all organs; the complex interplay between parenchymal tissue and endothelial cells in the context of infection was not demonstrated | 113 |

| PDMS | Soft lithographic | Lung endothelial barrier | SARS-CoV-2 disrupts respiratory vascular barriers by suppressing Claudin-5 expression | Lack immune cells, the mechanism is not fully understood | 114 |

‒, not applicable.

The intestine is also a high-risk organ for SARS-CoV-2 infection109. A micro-engineered gut-on-chip reconstitutes the critical features of the intestinal epithelium-vascular endothelium barrier through the three-dimensional (3D) coculture of human mucin-secreting intestinal epithelial and vascular endothelial cells under physiological fluid flow. Transcriptional analysis revealed abnormal RNA and protein metabolism. It activated immune responses in both epithelial and endothelial cells after viral infection, which may contribute to the intestinal barrier injury associated with gastrointestinal symptoms. This human organ system can partially mirror intestinal barrier injury and the human response to viral infection, which is impossible in existing in vitro culture models (Fig. 5B) (Table 5)110. In addition, other organ chips are also used to study the potential mechanism of SARS-CoV-2. For example, the introduction of spike proteins to in vitro models of the blood–brain barrier (BBB) showed significant changes in barrier properties. Key to the authors' findings is that S1 promotes loss of barrier integrity in an advanced 3D microfluidic model of the human BBB. This platform resembles the physiological conditions at this central nervous system interface. Evidence suggests that the SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins trigger a pro-inflammatory response in brain endothelial cells that may contribute to an altered state of BBB function. These results are the first time to show the direct impact of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein on brain endothelial cells, thereby offering a plausible explanation for the neurological consequences seen in COVID-19 patients (Table 5)111.

Evidence shows that vascular pathology could substantially affect COVID-19 disease outcomes, as endothelial cells are susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Besides, cases of thrombotic events are reported following vaccination. Satta et al.112 recapitulated the human microcirculation environment using a novel microfluidic platform to elucidate Spike proteins underlying patient-specific vascular thrombosis (Table 5). It was coated with human endothelial cells and exposed to patient-specific whole blood. The blood coagulation effect is tested after exposure to Spike protein in nanoparticles and Spike variant D614G in viral vectors, and the results are corroborated using live SARS-CoV-2. Finally, the authors proved that nanoliposome-hACE2 and anti-Interleukin (IL) 6 antibodies can reduce blood clot formation. To further study the immune reaction of vascular after SARS-CoV-2 infection, Lu et al.113 also developed a vasculature-on-a-chip to model the interaction of the virus with the endothelial and virus-exposed-endothelial cells with peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (Table 5). They demonstrated the compounding effects of inter-cellular crosstalk between endothelial cells and monocytes in facilitating the hyperinflammatory state. They identified angiopoietin-1 derived peptide QHREDGS as a potential therapeutic capable of profoundly attenuating the inflammatory state of the cells consistent with the levels in non-infected controls, thereby improving the barrier function and endothelial cell survival against SARS-CoV-2 infection in the presence of PBMC. Moreover, Hashimoto et al.114 investigated the effect of SARS-CoV-2 on the endothelial barrier using an airway-on-a-chip and found that SARS-CoV-2 disrupts the respiratory endothelial barrier by decreasing CLDN5 expression and disorganizing the VE-cadherin-mediated junction (Table 5). They proved that CLDN5 over-expression and Fluvastatin treatment could suppress the respiratory endothelial barrier disruption.

However, the application of organs on chips for studying virus infection still needs to be improved in research for unsatisfying reproducibility, stability, user-friendliness, and incomplete biological functions of engineering chips. In the future, many aspects need to improve, including a universal medium or a management system for different media, upscaled devices to accommodate growing organoids with higher resolution, strengthening the crosstalk between different organoids, integrating with different biosensors to monitor cells in real-time and machine learning for computational drug screen13,115.

3.2. Microfluidic technology for COVID-19-associated nanoparticle engineering

Nowadays, the delivery of messenger RNA (mRNA) in vivo has been used to prevent and treat many diseases, including SARS-CoV-2116, 117, 118, 119. The carriers for the delivery have a significant effect on such strategies, including clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) antisense oligonucleotides (ASO), short interfering RNA (siRNA), microRNA (miRNA), and mRNA120. Gene delivery based on engineered nanoparticles has the feasibility and tenability, proved to reduce the off-target related risks121. Nanoparticles enable the effective delivery of drugs, improving circulation time, targeting efficiency, and reducing potential adverse side effects. Nanoscale materials have features of a smaller size, high surface-to-volume ratio, tunable surface chemistry, and the capacity to load drugs122. Nanocarriers can also be used to deliver antiviral therapeutics into cells to intervene with the viral-replication cycle at the molecular level or to deliver plasmid DNA123 and mRNA124 for vaccination. Several mRNA nanoparticle-based vaccines have been used for COVID-19 prevention, even for clinical development125. LNPs with properties of proper sizes, stable storage, efficient payload capture, and release rates will meet the requirements for nucleic acid delivery126. However, they still lack high encapsulation efficiency and excellent scalability.

Microfluidic technology has significant benefits in preparing LNPs. By being highly versatile with a wide range of channel dimensions, multiple fabrication materials (e.g., polymers or glass), and lipid formulations, microfluidic devices can produce homogenous-sized LNPs127. A simple microfluidic-reactor-platform designed with continuous circular serpentine was reported for in-situ metal-nanoparticle synthesis128. This novel microfluidic platform has the advantages of in-situ synthesis, flow parameter control, and reduced agglomeration of nanoparticles over the bulk synthesis due to the segregation of nucleation and growth stages inside a microchannel. Importantly, nanoparticle production does not need complex instrumentation. The fluid behavior in microfluidic chips is not controlled by the inertial ones but by the viscous forces129. The continuous flows ensure that obtained nanoparticles have the same quality over time, preventing the issues of batch-to-batch variability. By utilizing the different geometries of microfluidic channels designed, the formation of different types of fast mixing patterns and controlled nanoparticle production becomes feasible130, 131, 132.

Nanomaterials also play roles in virus treatment to provide cofactors such as Zn2+, inhibiting RNA polymerase and transcription133. Zn−-based nanomaterials that bind RNA polymerase could be designed and administered to inhibit virus replication. In contrast to dendrimers or polymers, DNA nanostructures' valency, and spatial structures can be efficiently designed. In addition, DNA nanomaterials are stable and non-toxic. Therefore, DNA nanostructures with particular shapes, modified with virus-targeting aptamers, can be applied for virus detection and inhibition134. Owing to their customized spatial structure, such DNA nanostructures precisely match the viral surface, enabling efficient virus capture5. The proposed in-situ synthesized nanoparticle can also be utilized as a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine.

Additionally, the technology integrated with high-throughput microfluidic droplets, mammalian cell engineering, and molecular genomics were reported to capture diverse mammalian antibody repertoires and generate recombinant hyperimmune globulins, which were proven high specificity and activity against therapeutic targets, including SARS-CoV-2135. When primary B cells ran through the microfluidic channels, antibody repertoires were created by fusing heavy and light chain immunoglobulin nucleic acid sequences on a single-cell level. The authors applied the technology to develop 103 to 104 diverse recombinant hyperimmune globulin drug candidates to address unmet clinical needs for the COVID-19 pandemic and validated them in vivo. In addition, there are other nanomedicines for COVID-19-associated symptom control. Achieving protection from the virus in the whole respiratory tract, avoiding blood dissemination, and calming the subsequent cytokine storm remain significant challenges. Wang et al.136 developed an inhaled microfluidic microsphere based on droplet using dual camouflaged methacrylate hyaluronic acid hydrogel microspheres with genetically engineered membranes from angiotensin-converting enzyme II (ACE2) receptor-overexpressing cells and macrophages. By timely competing with the virus for ACE2 binding, the inhaled microspheres significantly reduced SARS-CoV-2 infective effectiveness over the whole course of the respiratory system in vitro and in vivo. Moreover, the inhaled microspheres efficiently neutralized pro-inflammatory cytokines, caused an alternative landscape of lung-infiltrated immune cells, and alleviated lymph nodes and spleen hyperinflammation.

LNP production based on microfluidics proved scalable, cost-effective, and versatile7. Besides, microfluidic systems can be integrated with multiple micromixers to achieve parallel reactions137. However, the multifunctionality and biodegradability of lipids should be considered in practice to boost the payload's efficacy, minimizing long-term genome integration and immunogenicity127.

4. Conclusions

As microfluidic technology entered the field of biomedicine in the early 2000s, it has dramatically affected many aspects. Like a small-sized laboratory, a microfluidic chip provides a platform to accomplish all the operations of traditional detection methods. On the other hand, organ-on-a-chip creates biomimetic and mini-organs to simulate the reactions and biological processes in vivo. When a viral disease outbreak occurs, it is essential to rapid response to get the basic information and continuously study antiviral strategies. Microfluidic technology plays a crucial role in anti-SARS-CoV-2 research, including constructing point-of-care devices to identify infected patients, establishing organ chips to study viral pathogenic mechanisms, and screening drugs for efficient antiviral therapies, and the design of nanoparticle synthesis methods to deliver mRNA as vaccination.

To prepare for new viral outbreaks and to accelerate and coordinate our responses to COVID-19, we still need to overcome many challenges. Firstly, portable and inexpensive devices for separating and purifying viruses from saliva and whole blood samples are required to obtain viral knowledge rapidly. Secondly, microfluidic chips need to integrate with higher resolution microscopy and more advanced materials-enabled technologies to enable the evaluation of the real-time dynamics of viruses in cells or tissues and further the observation of the interaction between drugs and viruses. Thirdly, the cost of current diagnosis kits should be lowered when maintaining accuracy and sensitivity, considering resource-poor people who live in medical conditions limited regions. Finally, using the vectors based on biocompatible materials would benefit the delivery of antiviral drugs and vaccines, reduce systemic toxicity, improve circulation time, co-deliver multiple components, increase drug or vaccine stability, and target specific cells or tissues.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82072087, 31970893, 32270976) and funding by Science and Technology Projects in Guangzhou (202206010087, China).

Author contributions

Zhun Lin, Zhengyu Zou, and Zhe Pu drafted the manuscript. Minhao Wu and Yuanqing Zhang revised the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Peer review under the responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Contributor Information

Minhao Wu, Email: wuminhao@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Yuanqing Zhang, Email: zhangyq65@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Gates B. Responding to Covid-19 – a once-in-a-century pandemic? N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1677–1679. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2003762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou P., Yang X.L., Wang X.G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W., et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim D., Lee J.Y., Yang J.S., Kim J.W., Kim V.N., Chang H. The architecture of SARS-CoV-2 transcriptome. Cell. 2020;181:914–921. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jungreis I., Sealfon R., Kellis M. SARS-CoV-2 gene content and COVID-19 mutation impact by comparing 44 SarbeCoVirus genomes. Nat Commun. 2021;12:2642. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22905-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang Z.M., Kong N., Zhang X.C., Liu Y., Hu P., Mou S., et al. A materials-science perspective on tackling COVID-19. Nat Rev Mater. 2020;5:847–860. doi: 10.1038/s41578-020-00247-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitesides G.M. The origins and the future of microfluidics. Nature. 2006;442:368–373. doi: 10.1038/nature05058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ren K.N., Zhou J.H., Wu H.K. Materials for microfluidic chip fabrication. Acc Chem Res. 2013;46:2396–2406. doi: 10.1021/ar300314s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shrimal P., Jadeja G., Patel S. A review on novel methodologies for drug nanoparticle preparation: microfluidic approach. Chem Eng Res Des. 2020;153:728–756. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamdallah S.I., Zoqlam R., Erfle P., Blyth M., Alkilany A.M., Dietzel A., et al. Microfluidics for pharmaceutical nanoparticle fabrication: the truth and the myth. Int J Pharm. 2020;584 doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hwang J., Cho Y.H., Park M.S., Kim B.H. Microchannel fabrication on glass materials for microfluidic devices. Int J Precis Eng Man. 2019;20:479–495. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basiri A., Heidari A., Nadi M.F., Fallahy M.T.P., Nezamabadi S.S., Sedighi M., et al. Microfluidic devices for detection of RNA viruses. Rev Med Virol. 2021;31:1–11. doi: 10.1002/rmv.2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang C., Liu M., Wang Z.F., Li S., Deng Y., He N.Y. Point-of-care diagnostics for infectious diseases: from methods to devices. Nano Today. 2021;37 doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2021.101092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramezankhani R., Solhi R., Chai Y.C., Vosough M., Verfaillie C. Organoid and microfluidics-based platforms for drug screening in COVID-19. Drug Discov Today. 2022;27:1062–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2021.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wongkaew N., Simsek M., Griesche C., Baeumner A.J. Functional nanomaterials and nanostructures enhancing electrochemical biosensors and lab-on-a-Chip performances: recent progress, applications, and future perspective. Chem Rev. 2019;119:120–194. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi H.H., Nie K.X., Dong B., Long M.Q., Xu H., Liu Z.C. Recent progress of microfluidic reactors for biomedical applications. Chem Eng J. 2019;361:635–650. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun W.J., Luo Z.M., Lee J.M., Kim H.J., Lee K.J., Tebon P., et al. Organ-on-a-chip for cancer and immune organs modeling. Adv Healthc Mater. 2019;8 doi: 10.1002/adhm.201801363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moradi E., Jalili-Firoozinezhad S., Solati-Hashjin M. Microfluidic organ-on-a-chip models of human liver tissue. Acta Biomater. 2020;116:67–83. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2020.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song Y.J., Hormes J., Kumar C.S.S.R. Microfluidic synthesis of nanomaterials. Small. 2008;4:698–711. doi: 10.1002/smll.200701029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pan L.J., Tu J.W., Ma H.T., Yang Y.J., Tian Z.Q., Pang D.W., et al. Controllable synthesis of nanocrystals in droplet reactors. Lab Chip. 2017;18:41–56. doi: 10.1039/c7lc00800g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niculescu A.G., ChirCoV C., Bîrcă A.C., Grumezescu A.M. Fabrication and applications of microfluidic devices: a review. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:2011. doi: 10.3390/ijms22042011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fiorini G.S., Chiu D.T. Disposable microfluidic devices: fabrication, function, and application. Biotechniques. 2005;38:429–446. doi: 10.2144/05383RV02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song K., Li G.Q., Zu X.Y., Du Z., Liu L.Y., Hu Z.G. The fabrication and application mechanism of microfluidic systems for high throughput biomedical screening: a review. Micromachines. 2020;11:297. doi: 10.3390/mi11030297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yetisen A.K., Akram M.S., Lowe C.R. Paper-based microfluidic point-of-care diagnostic devices. Lab Chip. 2013;13:2210–2251. doi: 10.1039/c3lc50169h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kevadiya B.D., Machhi J., Herskovitz J., Oleynikov M.D., Blomberg W.R., Bajwa N., et al. Diagnostics for SARS-CoV-2 infections. Nat Mater. 2021;20:593–605. doi: 10.1038/s41563-020-00906-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.La Rosa G., Iaconelli M., Mancini P., Bonanno Ferraro G., Veneri C., Bonadonna L., et al. First detection of SARS-CoV-2 in untreated wastewaters in Italy. Sci Total Environ. 2020;736 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Razzini K., Castrica M., Menchetti L., Maggi L., Negroni L., Orfeo N.V., et al. SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection in the air and on surfaces in the COVID-19 ward of a hospital in Milan, Italy. Sci Total Environ. 2020;742 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deng H.M., Gao Z.Q. Bioanalytical applications of isothermal nucleic acid amplification techniques. Anal Chim Acta. 2015;853:30–45. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2014.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ackerman C.M., Myhrvold C., Thakku S.G., Freije C.A., Metsky H.C., Yang D.K., et al. Massively multiplexed nucleic acid detection with Cas13. Nature. 2020;582:277–282. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2279-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kilic T., Weissleder R., Lee H. Molecular and immunological diagnostic tests of COVID-19: current status and challenges. iScience. 2020;23 doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2020.101406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smyrlaki I., Ekman M., Lentini A., Rufino de Sousa N., Papanicolaou N., Vondracek M., et al. Massive and rapid COVID-19 testing is feasible by extraction-free SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR. Nat Commun. 2020;11:4812. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18611-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trinh T.N.D., La H.C., Lee N.Y. Fully integrated and foldable microdevice encapsulated with agarose for long-term storage potential for point-of-care testing of multiplex foodborne pathogens. ACS Sens. 2019;4:2754–2762. doi: 10.1021/acssensors.9b01299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mitsakakis K., D'Acremont V., Hin S., von Stetten F., Zengerle R. Diagnostic tools for tackling febrile illness and enhancing patient management. Microelectron Eng. 2018;201:26–59. doi: 10.1016/j.mee.2018.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ji M.H., Xia Y., Loo J.F.C., Li L., Ho H.P., He J.N., et al. Automated multiplex nucleic acid tests for rapid detection of SARS-CoV-2, influenza A and B infection with direct reverse-transcription quantitative PCR (dirRT-qPCR) assay in a centrifugal microfluidic platform. RSC Adv. 2020;10:34088–34098. doi: 10.1039/d0ra04507a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haeberle S., Zengerle R. Microfluidic platforms for lab-on-a-chip applications. Lab Chip. 2007;7:1094–1110. doi: 10.1039/b706364b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schumacher S., Nestler J., Otto T., Wegener M., Ehrentreich-Förster E., Michel D., et al. Highly-integrated lab-on-chip system for point-of-care multiparameter analysis. Lab Chip. 2012;12:464–473. doi: 10.1039/c1lc20693a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kang B.H., Lee Y., Yu E.S., Na H., Kang M., Huh H.J., et al. Ultrafast and real-time nanoplasmonic on-chip polymerase chain reaction for rapid and quantitative molecular diagnostics. ACS Nano. 2021;15:10194–10202. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.1c02154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sakai J., Tarumoto N., Orihara Y., Kawamura R., Kodana M., Matsuzaki N., et al. Evaluation of a high-speed but low-throughput RT-qPCR system for detection of SARS-CoV-2. J Hosp Infect. 2020;105:615–618. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tahamtan A., Ardebili A. Real-time RT-PCR in COVID-19 detection: issues affecting the results. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2020;20:453–454. doi: 10.1080/14737159.2020.1757437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giri B., Pandey S., Shrestha R., Pokharel K., Ligler F.S., Neupane B.B. Review of analytical performance of COVID-19 detection methods. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2021;413:35–48. doi: 10.1007/s00216-020-02889-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chau C.H., Strope J.D., Figg W.D. COVID-19 clinical diagnostics and testing technology. Pharmacotherapy. 2020;40:857–868. doi: 10.1002/phar.2439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jamiruddin M.R., Meghla B.A., Islam D.Z., Tisha T.A., Khandker S.S., Khondoker M.U., et al. Microfluidics technology in SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis and beyond: a systematic review. Life. 2022;12:649. doi: 10.3390/life12050649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xie X., Gjorgjieva T., Attieh Z., Dieng M.M., Arnoux M., Khair M., et al. Microfluidic nano-scale qPCR enables ultra-sensitive and quantitative detection of SARS-CoV-2. Processes. 2020;8:1425. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fassy J., Lacoux C., Leroy S., Noussair L., Hubac S., Degoutte A., et al. Versatile and flexible microfluidic qPCR test for high-throughput SARS-CoV-2 and cellular response detection in nasopharyngeal swab samples. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tian F., Liu C., Deng J.Q., Han Z.W., Zhang L., Chen Q.H., et al. A fully automated centrifugal microfluidic system for sample-to-answer viral nucleic acid testing. Sci China Chem. 2020;63:1498–1506. doi: 10.1007/s11426-020-9800-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xiong H.W., Ye X., Li Y., Wang L.J., Zhang J., Fang X.E., et al. Rapid differential diagnosis of seven human respiratory coronaviruses based on centrifugal microfluidic nucleic acid assay. Anal Chem. 2020;92:14297–14302. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.0c03364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Song W.D., Zhang T.Y., Lin H.C., Yang Y.J., Zhao G.Z., Huang X.W. Conventional and microfluidic methods for the detection of nucleic acid of SARS-CoV-2. Micromachines. 2022;13:636. doi: 10.3390/mi13040636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yin K., Ding X., Xu Z.H., Li Z.Y., Wang X.Y., Zhao H., et al. Multiplexed colorimetric detection of SARS-CoV-2 and other pathogens in wastewater on a 3D printed integrated microfluidic chip. Sens Actuators B Chem. 2021;344 doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2021.130242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xing W.L., Liu Y.Y., Wang H.L., Li S.L., Lin Y.P., Chen L., et al. A high-throughput, multi-index isothermal amplification platform for rapid detection of 19 types of common respiratory viruses including SARS-CoV-2. Engineering. 2020;6:1130–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.eng.2020.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu D., Shen H.C., Zhang Y.Q., Shen D.Y., Zhu M.Y., Song Y.L., et al. A microfluidic-integrated lateral flow recombinase polymerase amplification (MI-IF-RPA) assay for rapid COVID-19 detection. Lab Chip. 2021;21:2019–2026. doi: 10.1039/d0lc01222j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Park J.S., Hsieh K., Chen L., Kaushik A., Trick A.Y., Wang T.H. Digital CRISPR/Cas-assisted assay for rapid and sensitive detection of SARS-CoV-2. Adv Sci. 2021;8 doi: 10.1002/advs.202003564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Welch N.L., Zhu M.L., Hua C., Weller J., Mirhashemi M.E., Nguyen T.G., et al. Multiplexed CRISPR-based microfluidic platform for clinical testing of respiratory viruses and identification of SARS-CoV-2 variants. Nat Med. 2022;28:1083–1094. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01734-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ramachandran A., Huyke D.A., Sharma E., Sahoo M.K., Huang C., Banaei N., et al. Electric field-driven microfluidics for rapid CRISPR-based diagnostics and its application to detection of SARS-CoV-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:29518–29525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2010254117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tian T., Shu B.W., Jiang Y.Z., Ye M.M., Liu L., Guo Z.H., et al. An ultralocalized Cas13a assay enables universal and nucleic acid amplification-free single-molecule RNA diagnostics. ACS Nano. 2021;15:1167–1178. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c08165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen L., Yadav V., Zhang C.G., Huo X.Y., Wang C.M., Senapati S., et al. Elliptical pipette generated large microdroplets for POC visual ddPCR quantification of low viral load. Anal Chem. 2021;93:6456–6462. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.1c00192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nguyen H.Q., Bui H.K., Phan V.M., Seo T.S. An internet of things-based point-of-care device for direct reverse-transcription-loop mediated isothermal amplification to identify SARS-CoV-2. Biosens Bioelectron. 2022;195 doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2021.113655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Silva F.S.R., Erdogmus E., Shokr A., Kandula H., Thirumalaraju P., Kanakasabapathy M.K., et al. SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection by a cellphone-based amplification-free system with CRISPR/CAS-dependent enzymatic (CASCADE) assay. Adv Mater Technol. 2021;6 doi: 10.1002/admt.202100602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim S., Lee J.H. Current advances in paper-based biosensor technologies for rapid COVID-19 diagnosis. Biochip J. 2022;16:376–396. doi: 10.1007/s13206-022-00078-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Castrejón-Jiménez N.S., García-Pérez B.E., Reyes-Rodríguez N.E., Vega-Sánchez V., Martínez-Juárez V.M., Hernández-González J.C. Challenges in the detection of SARS-CoV-2: evolution of the lateral flow immunoassay as a valuable tool for viral diagnosis. Biosensors. 2022;12:728. doi: 10.3390/bios12090728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang D.M., He S.G., Wang X.H., Yan Y.Q., Liu J.Z., Wu S.M., et al. Rapid lateral flow immunoassay for the fluorescence detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA. Nat Biomed Eng. 2020;4:1150–1158. doi: 10.1038/s41551-020-00655-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhu X., Wang X.X., Han L.M., Chen T., Wang L.C., Li H., et al. Multiplex reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification combined with nanoparticle-based lateral flow biosensor for the diagnosis of COVID-19. Biosens Bioelectron. 2020;166 doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2020.112437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Agarwal S., Warmt C., Henkel J., Schrick L., Nitsche A., Bier F.F. Lateral flow-based nucleic acid detection of SARS-CoV-2 using enzymatic incorporation of biotin-labeled dUTP for POCT use. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2022;414:3177–3186. doi: 10.1007/s00216-022-03880-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li Z.Y., Ding X., Yin K., Avery L., Ballesteros E., Liu C.C. Instrument-free, CRISPR-based diagnostics of SARS-CoV-2 using self-contained microfluidic system. Biosens Bioelectron. 2022;199 doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2021.113865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lieberman J.A., Pepper G., Naccache S.N., Huang M.L., Jerome K.R., Greninger A.L. Comparison of commercially available and laboratory-developed assays for in vitro detection of SARS-CoV-2 in clinical laboratories. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58 doi: 10.1128/JCM.00821-20. e00821–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nalla A.K., Casto A.M., Huang M.W., Perchetti G.A., Sampoleo R., Shrestha L., et al. Comparative performance of SARS-CoV-2 detection assays using seven different primer-probe sets and one assay Kit. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58 doi: 10.1128/JCM.00557-20. e00557–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wölfel R., Corman V.M., Guggemos W., Seilmaier M., Zange S., Müller M.A., et al. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature. 2020;581:465–469. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]