Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Community health workers (CHWs) are trusted community members who provide health education and care. However, no consensus exists regarding whether community health worker-based interventions are effective within the school setting.

OBJECTIVE:

To determine outcomes and best practices of school-based community health worker interventions.

DATA SOURCES:

PubMed, CINAHL, and SCOPUS databases

STUDY ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA:

This systematic literature review examined articles that described an intervention led by community health workers, targeted children and/or parents, and took place primarily within a Kindergarten-12th grade school setting. Articles were excluded if they described an intervention outside the United States.

PARTICIPANTS:

Community health workers, children, and/or their parents

INTERVENTIONS:

School-based community health worker programs

RESULTS:

Of 1,875 articles identified, 13 met inclusion criteria and were included in the final analysis. Of these, five described a statistically significant primary outcome. Seven articles provided details regarding community health worker recruitment, training, and roles that would enable reproduction of the intervention.

LIMITATIONS:

This review focused on interventions in the United States. Bias of individual studies had a wide range of scores (9–21). Heterogeneity of studies also precluded a meta-analysis of primary outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS OF KEY FINDINGS:

The utilization of Community health workers in school-based interventions for children and/or parents is promising. This review identified a lack of detail and uniformity in program presentation, specifically with Community health worker recruitment, training, and roles. A standardized reporting mechanism for Community health worker interventions in schools would better allow for reproducibility and scalability of existing studies.

Keywords: children, community health workers, schools

INTRODUCTION

The school environment, while traditionally and primarily focused on ensuring children in the United States receive academic education, serves other diverse purposes. Often the setting of community meetings, athletic competitions, or local celebrations, the school setting holds promise as a place to also provide health programs and resources to youth, parents, and school staff. For example, previous studies show school-based interventions have succeeded in achieving weight reduction and improving asthma self-management among students.1,2

One potential strategy for school-based interventions is the use and integration of community health workers. The American Public Health Association defines a community health worker (CHW) as a “frontline public health worker who is a trusted member of and/or has an unusually close understanding of the community served.”3 The role of CHWs can take on many forms, including building individual and community capacity to deliver health education, implementing health-related programs, providing care coordination, advocating for individuals and communities, conducting outreach, or providing additional support to existing structures.3,4 CHW models have often been used to address social determinants of health by working in health promotion, disease prevention, and chronic disease management – areas of health that rely primarily on education and health choices, as opposed to acute medical needs.5,6 CHWs also regularly provide care for hard-to-reach populations and marginalized groups who may not have access to necessary health resources.7,8

CHW interventions have the potential to expand the reach of healthcare professionals or provide creative opportunities to deliver programming on their own to ensure every child receives the education and services they deserve. However, CHWs are more commonly used in homes, community centers, clinics, and hospitals than schools.7 Studies to date show that school-based interventions utilizing CHWs have been successful in decreasing BMI scores, decreasing A1C levels, and increasing asthma knowledge.9,10,11 However, it is unclear whether models that integrate CHWs within schools are broadly successful and, if so, the structure associated with the highest likelihood of success and best outcomes. To our knowledge, there is no systematic literature review that specifically examines CHW programs operating within the Kindergarten-12th grade school environment. The focus of the review is to determine if programs that include CHWs in schools lead to improved outcomes and to examine how CHWs are recruited, trained, and deployed in such interventions to elucidate best practices for future school-based CHW interventions. This systematic review seeks to fill this existing gap in the literature by examining interventions that applied a CHW model primarily in schools in the United States.

METHODS

Search Instruments and Strategy

We conducted a systematic literature review in PubMed, CINAHL and SCOPUS of articles published between 2000 and 2020. The most recent search occurred on December 15, 2020. We included studies that had some form of CHWs operating within the Kindergarten to 12th grade school building to intervene or educate at the level of the child or their parent(s). The researchers identified three key constructs: “community health workers”, “school”, and “children”. In partnership with a librarian, we developed the following search for PubMed: (“Community health workers”[Mesh] OR community health worker[tw] OR promotor*[tw] OR community aides[tw] OR lay health*[tw] OR health coach[tw] OR health aide[tw] OR health educator[tw] OR “patient navigation”[Mesh] OR peer counselor[tw] OR outreach worker[tw] OR chw [tiab]) AND (“Child”[Mesh] OR child*[tw] OR “youth” OR “school-aged” OR “adolescent”[Mesh] OR “student” OR “parent”) AND (“schools”[Mesh] OR school[tw] OR “elementary school” OR “high school” OR “preschool”). The search was adapted for the other databases with the librarian’s support. For the purposes of this manuscript, the term “community health worker” encompasses promotor, community aide, lay health worker, health coach, health aide, health educator, or outreach worker.12 This study was not registered with PROSPERO as PROSPERO does not accept “literature reviews that use a systematic approach.”13

Study Selection

A broad definition of CHW was used to create a wide net of inclusion given the many alternative titles used. Specifically, we included the following terms for CHW: health educator, lay health educator, health coach, promotor, community aide, peer counselor, or outreach worker. 12 Published studies were selected for inclusion in this review based on the following criteria: 1) study took place in the United States, 2) study was published in English, 3) study was published between 2000 and 2020, 4) research was focused on a CHW-based intervention that took place primarily in a Kindergarten-12th grade school setting (e.g. elementary school, middle school, high school, alternative school), and 5) recipients/target group of the intervention included children and/or parents. Alternative high school programs were included, while programs in the college or university setting were excluded. Articles were excluded if children or parents were recruited for the intervention in a school, but the intervention took place in a different setting or if only a portion of the intervention took place in a school.10,14–22 Articles were also excluded if they utilized peers, college students, or health professions (e.g. medical, pharmacy) students as the CHW. 9,23–32 Articles that took place in Head Start settings were also excluded.33–39 Finally, we found the term “health educator” was used with varying definitions, including to describe individuals who met CHW criteria or those who were permanent classroom health teachers. Studies were excluded if they used the term “health educator” to refer to a permanent classroom teacher.

Two reviewers (MH, NX, or MB) determined inclusion for each article. First, each reviewer independently examined the title and abstract of each article and determined if they should be included, excluded, or unsure according to the criteria above. Then, the independent reviews were matched. If the two reviewers disagreed or both reviewers marked unsure, both reviewers completed a full-text review to determine inclusion or exclusion of those articles. In cases where agreement could not be reached at that point, the research team discussed the article to reach consensus. All articles from the initial search were deemed included or excluded following the full-text review and discussion.

Data Extraction and Analysis

Data extraction from each article was completed by an independent reviewer (MH, IX). A subset of articles (n=3, 18%) were chosen at random and data was extracted for these articles by both reviewers for quality control; the reviewers had high levels of agreement. Topics for data extraction focused on the following: study objective/purpose, study design, power calculation, funding sources, school type and location, health issue/condition, target population (child, parent, school staff) information, CHW intervention information, and results. Specific data collected about the target population included: child age range/grade level, child race/ethnicity, inclusion criteria, and sample size. Specific data collected about the CHWs included: sample size, intervention site(s), recruitment/selection, training, role and activities, and persons interacted with. Data extracted about the intervention focused on activities, duration, follow-up(s), and outcomes. Given the heterogeneous participants and topics, we extracted the principal or primary outcomes as defined by the authors of each study.

For each article, risk of bias was assessed using the Downs and Black tool.40 This tool was specifically chosen to minimize subjectivity as it had rigorous criteria for evaluating studies. The tool consists of 27 questions focused on study quality in reporting, external validity, internal validity (bias and confounding), and power. For each article included in this review, one reviewer completed the Downs and Black tool, answering “yes”, “no”, or “unable to determine” for each question. The scores were then compiled per the tool to provide a summative score.

RESULTS

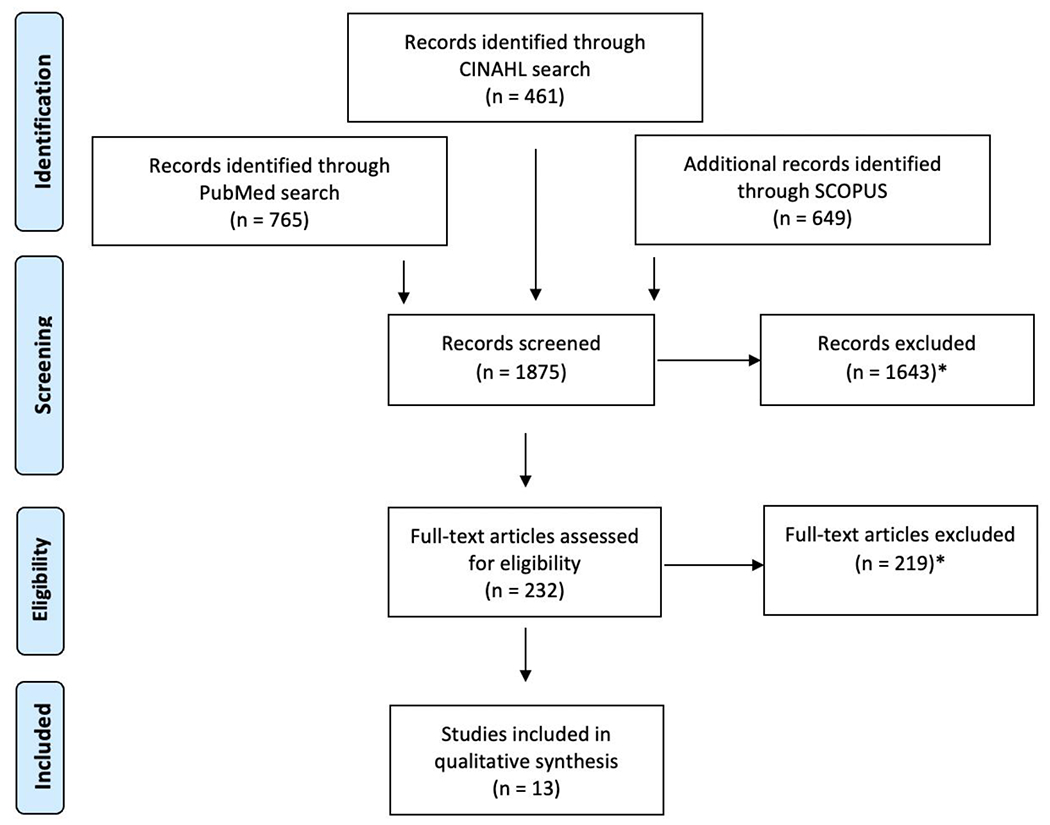

The initial search yielded a total of 1,875 articles, with 765 from PubMed, 461 from CINAHL, and 649 from SCOPUS. Following title and abstract review, a full text review was conducted for 232 articles, which yielded 13 unique studies for inclusion in the data extraction and analysis (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1: PRISMA Diagram.

*Reasons for exclusion included: not U.S. based, articles not in English, non-CHW intervention, intervention not in school or the intervention did not target children or parents. Many articles met multiple exlusionary criteria.

Study Characteristics

The included studies varied considerably (Table 1). They targeted a range of topics including oral caries prevention,41 asthma,11 violence prevention,42 resilience development,43 HIV and pregnancy prevention,44–45 knowledge around skin protection,46 obesity,47 smoking cessation,48–49 drug and alcohol abuse,50–53 community engagement,54 and parental involvement in schools.55 The largest number of studies (77%, n=10) targeted students in middle school and/or high school. The remaining studies sought to impact elementary age children (15%, n=2), and parents only (7%, n=1). Most studies took place in urban areas (69%, n=9), with geographical location ranging widely, including California, Colorado, Hawaii, Illinois, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, and Tennessee. Intervention length varied considerably from a single session to multiple sessions over the course of a year, with follow up times ranging from the same day to multiple years.

Table 1:

Characteristics of studies evaluating community health worker programs in schools

| Authors | Target Population | Health Issue or Condition | School type and location | Study Design | Funding Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nelson S & Milgrom M. (2012)41 | Youth grades K-2 (n=492), 96% African American | Oral caries prevention | Public schools, urban Ohio | Cluster-randomized trial lasting 3 years with 5 CHWs | US Dept of Health and Human Services |

| Horner SD & Fouladi RT. (2008)11 | Youth grades 2-5 (n=183), racially diverse cohort | Asthma | Unspecified, rural | Randomized control trial lasting 3 months with 18 CHWs | National Institute of Health |

| Fagen MC & Flay BR. (2009)42 | Youth grades 5-8 from five schools, predominantly African American | Prevention of violence, risky behavior, and substance abuse | Public school, urban Chicago | Multiple case study lasting 1 year with unknown number of CHWs | Illinois Violence Prevention Authority |

| Lee JA, et al.(2021)43 | Youth grade 6 (n=287), majority Caucasian (68%) | Resilience development | Unspecified, urban Colorado | Single group intervention lasting 8 weeks with 8 CHWs | Children’s Hospital Colorado Springs and Community Donors |

| Siegel DM, et al. (2001)44 | Youth grades 6-12 (n=4001), racially diverse | HIV and pregnancy prevention | Public school, urban northeast city | Quasi-experimental design lasting 2-7 weeks with unknown number of CHWs | National Institute of Health |

| Irwin B, et al. (2007)46 | Youth grades 6-12 (n=844), racially diverse | Knowledge pertaining to skin protection | Unspecified, urban New Jersey | Non-randomized quantitative study lasting 1 hour with 1 CHW | Women’s Dermatological Society |

| Love-Osborne K, et al. (2014)47 | Youth grades 6-12 (n=149), 88% Hispanic | Obesity | Public schools, Colorado | Randomized control trial lasting 6-8 months with unknown number of CHWs | Colorado Health Foundation |

| Ferketich AK, et al. (2007)48 | Youth grades 7-8 (n=51), 100% Chinese or Taiwanese | Smoking cessation | Public school, urban New York City | Non-randomized cohort study lasting 5 months with 1 CHW | American Legacy Foundation |

| Anderman EM, et al. (2009)45 | Youth ages 13-18 (n=697), racially diverse | HIV and Pregnancy prevention | Unspecified, Midwest | Quasi-experimental randomized study lasting unknown length of time with 5 CHWs | No documentation |

| Robinson LA, et al. (2003)49 | Youth ages 13-19 (n=261), racially diverse | Smoking cessation | Unspecified, urban Memphis | Randomized control trial lasting 13 months with 2 CHWs | National Institute on Drug Abuse |

| Sun, et al. (2008)50–53 | Youth ages 14-19 (n=1074), racially diverse | Drug abuse | Continuation high schools, urban southern California | Randomized control trial lasting 3 weeks with 9 CHWs | National Institute on Drug Abuse |

| Garcia BK, et al. (2019)54 | Youth grades 7-12 (n=133), racially diverse | Engage and empower students to assess their health needs and community interests | Public school, rural Hawaii | Qualitative needs assessment lasting a single session with 2 CHWs | No documentation |

| Snell P, et al. (2009)55 | Parents of middle school students (n=23), majority Hispanic | Parental Involvement in schools | Unspecified, urban Colorado | Participatory action research study lasting 9 months with 4 CHWs | National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research |

Risk of Bias

A risk of bias analysis using the Downs and Black tool showed total scores ranging from 9 to 22. Most studies adequately reported the study hypothesis, objectives, target population characteristics, and intervention details. Given the range of study types included in this analysis, several questions in the tool, including those related to blinding, randomization concealment, and whether the control/intervention arms occurred at the same time, received “unable to determine” designations and thus a score of 0. Originally, the scores from this tool were to be used to determine which studies should be incorporated into a larger meta-analysis. However, due to the heterogeneity of study design, topics, and results, we were unable to do so.

Study Outcomes

Of the 13 studies, eight reported positive primary outcomes (62%), of which five (38%) reported statistically significant positive outcomes (Table 2). Seven of the 13 studies (54%) provided details regarding CHW recruitment, training, and role (Table 3). There was no correlation between studies that presented CHW specific information and those that had positive primary outcomes – two studies reported statistically significant positive outcomes (n=2, 29%),11,43 three studies reported non-statistically significant positive outcomes (n=3, 43%)41,54–55 and two studies reported no positive primary outcomes (n=2, 29%).42,48 Of the 5 studies (38%) that did not report a positive outcome, one found limited success in moving an intervention from initiation to stabilization phase,42 one found a larger decrease in BMI z-score for a control group when compared to intervention group,47 two found no changes in self-reported smoking cessation behavior rates,48–49 and one found students responded better to their primary classroom teacher than a temporary health educator when presented with HIV and pregnancy prevention information.45

Table 2:

Primary outcomes of studies evaluating community health worker programs in schools

| Authors | Health Issue or Condition | Primary Outcome | Risk of Bias Total Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nelson S & Milgrom M. (2012)41 | Oral caries prevention | Successfully recruited 86% of eligible school children into program, confirming recruitment strategies that are helpful in enhancing minority participation rates. No test of statistical significance. | 17 |

| Horner SD & Fouladi RT. (2008)11 | Asthma | Treatment group, when compared to controlled group resulted in: -Better asthma knowledge (- 4.47% greater mean change, p=0.03) -Self-efficacy (−.24% greater mean change, p=0.15) -Asthma management (−.22% greater mean change, p=0.02) -MDI skill (−1.23% greater mean change, p=<0.001) |

19 |

| Fagen MC & Flay BR. (2009)42 | Prevention of violence, risky behavior, and substance abuse | Minimal success in moving project from initiation to stabilization phase given high variability between schools and difficulty of having parent educators fully deliver curriculum. The average percentage of curriculum taught by the Parent Educators ranged from 23-71% at the 5 schools. No test of statistical significance. | 12 |

| Lee JA, et al. (2021)43 | Resilience development | Student resilience increased significantly by 1.9 units (p<0.001), youth personal resilience significantly increased by 1.3 units (p<0.001), and youth relational resilience significantly increased by 0.7 units (p=0.006). | 18 |

| Siegel DM, et al. (2001)44 | HIV and pregnancy prevention | Intervention groups resulted in positive, sustained, long-term effect in knowledge (p<0.001 in middle school females and p<0.01 in middle school males) and self-efficacy regarding sexual matters (p<0.05 in middle school females and p<0.01 in high school females) when compared to control. | 19 |

| Irwin B, et al. (2007)46 | Knowledge pertaining to skin protection | Education resulted in a significant increase of 35.3% in correct answers on pre vs. post-test (p<0.001). | 20 |

| Love-Osborne K, et al. (2014)47 | Obesity | More students in the control group had decreased or maintained BMI z-score than the intervention group (72.2% vs 54.5%, p=0.025). | 20 |

| Ferketich AK, et al. (2007)48 | Smoking cessation | From pre to post-test, no change in number of students reporting they would not smoke a cigarette if offered, a 4% decrease in students reporting they definitely will not smoke a cigarette anytime during the next year, and 6.1% increase in students reporting they feel tobacco companies have tried to mislead them. No significance testing was completed due to small sample size. | 15 |

| Anderman EM, et al. (2009)45 | HIV and pregnancy prevention | Primary classroom teachers had more significant effects than temporary health educators on student-reported teacher creditability (main effect=0.4, p<0.05), classroom mastery (main effect=0.37, p<0.001) and teacher affinity (main effect=0.27, p<0.05). | 17 |

| Robinson LA, et al. (2003)49 | Smoking cessation | No difference in smoking cessation rates for treated adolescents when compared with control group (20.1% vs 24.2%, p=0.45). | 21 |

| Sun, et al. (2008)50–53 | Drug abuse | Significantly reduced hard drug use (42%, p=0.02) in number of times hard drugs were used in last 30 days when program groups were compared to control. | 20 |

| Garcia BK, et al. (2019)54 | Engage and empower students to assess their health needs and community interests | Qualitatively reported effectively engaging parents within the school on numerous topics including student performance, violence, and community respect. No test of statistical significance. | 9 |

| Snell P, et al. (2009)55 | Parental involvement in schools | Surveys obtained from 133 students, yielding rich information from students on importance and strengths of Native Hawaiian community, culture and ‘ohana’. No test of statistical significance. | 10 |

Table 3:

Community health worker (CHW) recruitment, training, and roles in school programs

| Authors | Health Issue or Condition | CHW identifying name | Recruitment/Selection | Training | Roles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nelson S & Milgrom M. (2012)41 | Oral caries prevention | Community outreach workers | - Recommended by elementary school principals - Previously served as parent-liaison in the school, substitute teacher, or as parent volunteers |

- Weeklong session on background and prevention of tooth decay, study and recruitment procedures, oral health education curriculum, protection of human subjects, and completion of data collection forms | - Recruited children and implemented study procedures at classroom level - Recruited students at open houses, curriculum nights, health fairs and prearranged pick up/drop off times for forms |

| Horner SD & Fouladi RT. (2008)11 | Asthma | Lay Health Educator | - Nominated by school personnel - Identified as dependable school volunteers who lived in the community |

- Sixteen hours of intensive content review, presentation strategies, classroom management, individual review of manuals and practice with educational materials and feedback session | - Implemented sixteen sequential, fifteen-minute sessions during school lunch breaks |

| Fagen MC & Flay BR. (2009)42 | Prevention of violence, risky behavior, and substance abuse | Health Educator | - School principals recommended parents | - Two-hour session for every 45 minutes spent delivering lesson | - Taught Aban Aya Youth Project curriculum |

| Lee JA, et al. (2021)43 | Resilience development | Health Coach | - Health coaches required to have one of following credentials: 1) certification from either accredited coaching program with National Commission for Certifying Agencies, or International Coach Federation accreditation, or 2) Master’s degree in health promotion, with health coaching class within degree curriculum | - Six, half-day sessions on defining resilience, therapeutic communication skills including reflections of meaning, feeling, content, and summarizing, creating focus and building motivation, motivational interviewing, and cultural competency | - Built rapport with youth - Held weekly one-on-one coaching sessions lasting 15 minutes where they helped youth develop goals and oversaw completion of pre and post surveys |

| Siegel DM, et al. (2001)44 | HIV and Pregnancy Prevention | RAPP Adult Health Educator | Not documented | Not documented | - Implemented Rochester AIDS Prevention Project for Youth curriculum in health classes |

| Irwin B, et al. (2007)46 | Skin protection | Health Educator | Not documented | Not documented | - Administered one-hour intervention including narrating PowerPoint slides for the lesson and administering pre and post-test |

| Love-Osborne K, et al. (2014)47 | Obesity | Health Educator | Not documented | - Full-day session on motivational interviewing techniques conducted by local expert - Follow-up session two months later |

- Pulled students out of class for visits - Measured height/weight, reviewed and modified student goals during visits - Linked students with existing resources |

| Ferketich AK, et al. (2007)48 | Smoking Cessation | Lay Educator | - Chosen from Chinese Progressive Association - Chinese immigrant with experience working with youth and training on tobacco control |

- Session on youth peer health education program design and implementation and tobacco-related topics and leadership skills | - Delivered smoking prevention curriculum. |

| Anderman EM, et al. (2009)45 | HIV and Pregnancy Prevention | Temporary Health Educator | Not documented | - Two days of curriculum training and practice teaching actual classes | - Taught fourteen lessons from the Reducing the Risk curriculum |

| Robinson LA, et al. (2003)49 | Smoking Cessation | Health Educator | Not documented | - Two days of motivational interviewing led by certified expert - Included program implementation practice until deemed proficient |

- Taught four weekly, fifty minute sessions - Called students monthly over the course of one year to check in and deliver brief interventions |

| Sun, et al. (2008)50–53 | Drug Abuse | Health Educator | No documented | - Two-and-a-half-hour session practicing curriculum delivery including observation | - Delivered Project Towards No Drug Abuse programming to two program conditions for three, fifty-minute sessions per week for three consecutive weeks |

| Garcia BK, et al. (2019)54 | Engage and empower students to assess their health needs and community interests | Health Educator | - Native Hawaiian from community - Graduates of Waianae Coast public schools and the University of Hawai’i at Manoa |

- Both CHWs had previous training in using participatory methods research and health programming | - Facilitated student lōkahi, health, and wellness by understanding needs of students - Provided health education on broad array of topics - Connected students to services and each other |

| Snell P, et al. (2009)55 | Parental Involvement in schools | Promotora Researchers | - Identified via teacher recommendations and sign-in sheets during parent-teacher conferences - Recruits mailed personalized invitation to participate in leadership training provided by local Latina parent and prominent community figure |

- Four-week session led by local Latina parent and prominent community figure | - Facilitated parent focus group sessions on feelings of parental involvement - Collectively analyzed data - Presented findings to school community |

While we found consistency in reporting information about the CHWs’ role in participant recruitment and intervention implementation, variability existed in reporting about CHW recruitment and training. Regarding CHW recruitment, most studies utilized convenience methods with referrals most commonly coming from other stakeholders in the project (i.e. principals, parents, community members). In one study, CHWs were required to have an advanced degree or coaching certificate,43 while in other studies they simply needed to be acquainted with the community.11,41–42,55 The CHW training mechanisms varied more widely. Some studies only required a single training session,48,50–53 while others required longitudinal training over the course of the study.42,47 Additionally, the most common term used to describe the CHW role was Health Educator (n=9, 69%).

The successful interventions led to better oral caries prevention,41 better asthma management,11 increased resilience development,43 improved HIV and pregnancy prevention,44 and improved knowledge around skin protection.46 There were two studies that examined the following topics: HIV and pregnancy prevention44–45 and smoking cessation.48–49 In the case of HIV and pregnancy prevention, there were two studies included in the analysis, with one reporting a sustained long term effect on knowledge gained (p<0.05, risk of bias score = 19)44 and the other showing no difference between education provided between a primary classroom teacher or temporary health educator (risk of bias score = 17).45 However, the studies’ varying objectives made direct comparison difficult. In the case of smoking cessation, there was no significant change in self-reported behavior or smoking cessation rates in either study.48–49

DISCUSSION

As the first systematic literature review focused on this topic, this study builds upon existing literature about CHW programs in communities and fills in gaps related to their impact in the school setting.12 The review identified significant heterogeneity of topics and participants among programs or interventions that integrate CHWs in schools, with most focused on one topic. A majority of studies demonstrated positive outcomes for children and/or parents, however outcomes ranged widely from recruitment, self-efficacy, and knowledge to condition-specific measures. These studies also provided incomplete information about the recruitment, training, and roles of CHWs in these programs, thus limiting reproducibility and leading to a call for standardized reporting criteria.

This review sheds light on the potential role of CHWs in schools to increase access to care, impact health outcomes, or prevent disease. We found over half of the studies resulted in a positive primary outcome (62%), and of those the majority (71%) provided information for all three categories of CHW evaluation: recruitment, training, and role. This finding may suggest that clear delineation of the CHW’s background and scope within an intervention may positively influence success, although there is insufficient power to evaluate statistically. Additionally, we found a wide variety of study topics and objectives were associated with positive outcomes. This is consistent with CHW interventions outside of the school setting that have similarly described success across a wide array of conditions and objectives.56–58 This finding suggests that CHW interventions can be flexible, carrying the potential to be individualized to the needs of each school and the specific population served by that school. It suggests that the intervention design and implementation is vital to attain positive outcomes, perhaps more so than the objective itself.

For this reason, we were particularly interested in the data regarding CHW recruitment, training, and roles. This review found studies reported limited information. In fact, only approximately half of the studies (54%) provided enough information in this area to allow for study reproduction. This limited information made it difficult to reach a consensus around what makes a school-based CHW program successful. In particular, studies often had minimal or no documentation pertaining to CHW recruitment. Additionally, while every study included some information regarding CHW roles, it was often incomplete or lacked enough detail to allow for reproducibility. This finding aligns with prior literature by Scott et. al that also found gaps in existing CHW literature pertaining to effective approaches to training and supervising CHWs. 59 As such, it is necessary to standardize the reporting criteria for CHW interventions to allow comparison across studies and build evidence-based findings that can contribute to best practices. Based on the results of this review, we propose that the following information should be reported for all school-based CHW interventions: specific details pertaining to the recruitment of CHWs (including where, when, and how, they were recruited), the training of CHWs (including the length, topics, and necessary renewal of the training), and the roles of the CHWs (including the details of their role(s) in program implementation and evaluation, as well as the length of their involvement in the study). Programs like the Community Healthy Worker Common Indicator Project, which seeks to standardize and improve measurement of CHW programs, have potential to significantly advance the field.60

It is also critical to note that most of the included studies were grant funded, predominantly by state or national organizations. As schools consider implementing CHW-based interventions, it will be important to consider alternative sources of funding as well. If such programs are to be sustained and grow, it will be important for program administrators to identify sustainable revenue sources beyond grants which tend to have a short duration and focus on short to medium-term outcomes. Given the relative lack of diversity of funding streams for the CHW initiatives examined in this review, this area may benefit from further study and action as well. Consideration must be given to financing of such school-based CHW programs through Medicaid or managed care organizations, given the broader movement of payment for CHWs in this mechanism.61

The broad array of study types and outcomes within this systematic literature review precluded quantitative comparison of outcomes and completion of a meta-analysis. The study was not registered in PROSPERO given “literature reviews that use a systematic approach” are ineligible.13 Also, the databases we used (PubMed, CINAHL and SCOPUS) predominantly include peer-reviewed manuscripts, however we did not include that articles must be peer-reviewed as part of our inclusion criteria. This review focused on studies completed since 2000 given the role of the CHW has changed over time, as have school structures and health services delivered. Additionally, this review only examined school-based CHW initiatives in the United States, in English. Given the long history and success of CHW interventions outside of the United States, international data on this subject could help establish best practices.62 However, due to the differences in policies related to education and health across countries, we decided it would be prudent to focus domestically.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of school-based CHW interventions. The results of this study are especially pertinent for school administrators and school-based health care professionals (i.e. nurses, pediatricians), who are commonly tasked with addressing health within the school. Additionally, the school nursing shortages across the country are pushing school leadership to find practical means to ensure students receive needed medical care as well as health prevention and education lessons.63 School leaders, school-based health providers, pediatric clinicians, and policy makers can use these findings to help develop and study community health worker programs in the school setting with the potential to further reach, educate, and care for United States children.

WHAT THIS SYSTEMATIC REVIEW ADDS

The first review to examine interventions that apply a community health worker model within schools and concisely summarize successful interventions.

It documents the need for a uniform reporting mechanism of school-based community health worker interventions to support reproducibility and establish best practices.

HOW TO USE THIS SYSTEMATIC REVIEW

Consider leveraging community health workers to support policy and models of care in schools or connected to school based community health workers

Utilize studies to create and implement common indicators of success for community health worker programs to enable reproducibility and comparison of outcomes

MESH TERMS

(“Community health workers”[Mesh] OR community health worker[tw] OR promotor*[tw] OR community aides[tw] OR lay health*[tw] OR health coach[tw] OR health aide[tw] OR health educator[tw] OR “patient navigation”[Mesh] OR peer counselor[tw] OR outreach worker[tw] OR chw [tiab]) AND (“Child”[Mesh] OR child*[tw] OR “youth” OR “school-aged” OR “adolescent”[Mesh] OR “student” OR “parent”) AND (“schools”[Mesh] OR school[tw] OR “elementary school” OR “high school” OR “preschool”).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Deborah Werner for her help facilitating this review and informing our search strategy in her role as medical librarian for the University of Chicago Biological Sciences Division.

Funding/Declaration of Competing Interests:

This project was funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Program. The funder did not play any role in study design, procedures, or analysis. Anna Volerman was also supported by the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (Award Number K23HL143128). No other authors have any competing interests to declare.

Appendix

PubMed Search Query:

(“Community health workers”[Mesh] OR community

health worker[tw] OR promotor*[tw] OR community aides[tw] OR lay health*[tw] OR health coach[tw] OR

health aide[tw] OR health educator[tw] OR “patient

navigation”[Mesh] OR peer counselor[tw] OR outreach worker[tw] OR chw [tiab]) AND

(“Child”[Mesh] OR child*[tw] OR “youth” OR “school-aged” OR “adolescent”[Mesh] OR “student” OR “parent”) AND (“schools”[Mesh] OR school[tw] OR “elementary school” OR “high school” OR “preschool”)

Filters: 2000–2020, English

Results: 765

SCOPUS Search Query:

(TITLE-ABS-KEY ("community health workers" OR "community health worker" OR promotora* OR promotore* OR "community aid*" OR "lay health*" OR "health coach" OR "health aide" OR

"health educator" OR "patient navigation" OR "peer counselor" OR "outreach worker" ) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "child*" OR "youth" OR "adolescent" OR "student" OR "parent" ) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ("school"))

Filters: 2000–2020, English, and Document type = Article or Review

Results: 808

CINAHL Search Query:

Search 3, 12/15/2020: ( MH "Community Health Workers" OR "community health worker" OR promotora* OR promotore* OR community aides OR lay health* OR health coach OR health aide OR health educator ) AND ( child* OR “youth” OR “adolescent” OR “student” OR “parent” ) AND ( school OR “preschool” OR “elementary school” OR “high school” )

Search mode: Boolean/phrase

Filters: Published Date: 2000–2020; Language: English; Source types: Academic journals

Results: 835

REFERENCES

- 1.Bruzzese J-M, Sheares BJ, Vincent EJ, et al. Effects of a School-based Intervention for Urban Adolescents with Asthma: A Controlled Trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(8):998–1006. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201003-0429OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katz DL, O’Connell M, Njike VY, Yeh M-C, Nawaz H. Strategies for the prevention and control of obesity in the school setting: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obes. 2008;32(12):1780–1789. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Community Health Workers. Accessed March 29, 2021. https://www.apha.org/apha-communities/member-sections/community-health-workers

- 4.Rosenthal EL; Menking P; and John J. St. The Community Health Worker Core Consensus (C3) Project: A Report of the C3 Project Phase 1 and 2, Together Leaning Toward the Sky A National Project to Inform CHW Policy and Practice Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center El Paso, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Community Health Worker National Workforce Study. Published online 2007. http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/reports/chwstudy2007.pdf

- 6.Zuvekas A, Nolan L, Tumaylle C, Griffin L. Impact of Community Health Workers on Access, Use of Services, and Patient Knowledge and Behavior: Journal of Ambulatory Care Management. 1999;22(4):33–44. doi: 10.1097/00004479-199910000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenthal EL, Wiggins N, Ingram M, Mayfield-Johnson S, De Zapien JG. Community Health Workers Then and Now: An Overview of National Studies Aimed at Defining the Field. Journal of Ambulatory Care Management. 2011;34(3):247–259. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0b013e31821c64d7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Viswanathan M, Kraschnewski JL, Nishikawa B, et al. Outcomes and Costs of Community Health Worker Interventions: A Systematic Review. Medical Care. 2010;48(9):792–808. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e35b51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arlinghaus KR, Moreno JP, Reesor L, Hernandez DC, Johnston CA. Compañeros : High School Students Mentor Middle School Students to Address Obesity Among Hispanic Adolescents. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017;14:170130. doi: 10.5888/pcd14.170130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malik FS, Yi-Frazier JP, Taplin CE, et al. Improving the Care of Youth With Type 1 Diabetes With a Novel Medical-Legal Community Intervention: The Diabetes Community Care Ambassador Program. Diabetes Educ. 2018;44(2):168–177. doi: 10.1177/0145721717750346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horner SD, Fouladi RT. Improvement of rural children’s asthma self-management by lay health educators. J Sch Health. 2008;78(9):506–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00336.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hartzler AL, Tuzzio L, Hsu C, Wagner EH. Roles and Functions of Community Health Workers in Primary Care. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(3):240–245. doi: 10.1370/afm.2208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.PROSPERO. Accessed July 28, 2022. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/#aboutpage

- 14.Stiles S, Thomas R, Beck AF, et al. Deploying Community Health Workers to Support Medically and Socially At-Risk Patients in a Pediatric Primary Care Population. Acad Pediatr. 2020;20(8):1213–1216. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2020.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gustafson EL, Atkins M, Rusch D. Community Health Workers and Social Proximity: Implementation of a Parenting Program in Urban Poverty. Am J Community Psychol. 2018;62(3–4):449–463. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kegler MC, Malcoe LH. Results from a lay health advisor intervention to prevent lead poisoning among rural Native American children. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(10):1730–1735. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.10.1730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burns BM, Merritt J, Chyu L, Gil R. The Implementation of Mindfulness-Based, Trauma-Informed Parent Education in an Underserved Latino Community: The Emergence of a Community Workforce. Am J Community Psychol. 2019;63(3–4):338–354. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castañeda X, Clayson ZC, Rundall T, Dong L, Sercaz M. Promising outreach practices: enrolling low-income children in health insurance programs in California. Health Promot Pract. 2003;4(4):430–438. doi: 10.1177/1524839903255523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bryant-Stephens T, Kenyon C, Apter AJ, et al. Creating a community-based comprehensive intervention to improve asthma control in a low-income, low-resourced community. J Asthma. 2020;57(8):820–828. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2019.1619083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crespo NC, Elder JP, Ayala GX, et al. Results of a multi-level intervention to prevent and control childhood obesity among Latino children: the Aventuras Para Niños Study. Ann Behav Med. 2012;43(1):84–100. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9332-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Findley S, Rosenthal M, Bryant-Stephens T, et al. Community-based care coordination: practical applications for childhood asthma. Health Promot Pract. 2011;12(6 Suppl 1):52S–62S. doi: 10.1177/1524839911404231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Edberg M, Cleary SD, Andrade E, et al. SAFER Latinos: a community partnership to address contributing factors for Latino youth violence. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2010;4(3):221–233. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2010.0009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee JB, DeFrank G, Gaipa J, Arden M. Applying a Global Perspective to School-Based Health Centers in New York City. Ann Glob Health. 2017;83(5–6):803–807. doi: 10.1016/j.aogh.2017.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun A, Kessell E, Tsoh J, Chan J, Chang J. Can Preschoolers be Health Messengers to Promote Breast Health among Chinese Americans? Californian Journal of Health Promotion. 2013;11:74–79. doi: 10.32398/cjhp.v11i3.1543 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aten MJ, Siegel DM, Enaharo M, Auinger P. Keeping middle school students abstinent: outcomes of a primary prevention intervention. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31(1):70–78. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00367-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tencati E, Kole SL, Feighery E, Winkleby M, Altman DG. Teens as Advocates for Substance use Prevention: Strategies for Implementation. Health Promotion Practice. 2002;3(1):18–29. doi: 10.1177/152483990200300104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin WH, Griest SE, Sobel JL, Howarth LC. Randomized trial of four noise-induced hearing loss and tinnitus prevention interventions for children. Int J Audiol. 2013;52 Suppl 1:S41–49. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2012.743048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomas AB, Ward E. Peer power: how Dare County, North Carolina, is addressing chronic disease through innovative programming. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2006;12(5):462–467. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200609000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tacker KA, Dobie S. MasterMind: Empower Yourself With Mental Health. A program for adolescents. J Sch Health. 2008;78(1):54–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00266.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ige TJ, DeLeon P, Nabors L. Motivational Interviewing in an Obesity Prevention Program for Children. Health Promot Pract. 2017;18(2):263–274. doi: 10.1177/1524839916647330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Timpe EM, Wuller WR, Karpinski JP. A regional poison prevention education service-learning project. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(4):87. doi: 10.5688/aj720487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wong VSS, Naguwa GS. The School Health Education Program (SHEP): medical students as health educators. Hawaii Med J. 2010;69(3):60–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Foster BA, Aquino CA, Gil M, Gelfond JAL, Hale DE. A Pilot Study of Parent Mentors for Early Childhood Obesity. J Obes. 2016;2016:2609504. doi: 10.1155/2016/2609504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Foster BA, Aquino C, Gil M, Flores G, Hale D. A randomized clinical trial of the effects of parent mentors on early childhood obesity: Study design and baseline data. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;45(Pt B):164–169. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flores-Peña Y, He M, Sosa ET, Avila-Alpirez H, Trejo-Ortiz PM. Study protocol: intervention in maternal perception of preschoolers’ weight among Mexican and Mexican-American mothers. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):669. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5536-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Braun PA, Quissell DO, Henderson WG, et al. A Cluster-Randomized, Community-Based, Tribally Delivered Oral Health Promotion Trial in Navajo Head Start Children. J Dent Res. 2016;95(11):1237–1244. doi: 10.1177/0022034516658612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quissell DO, Bryant LL, Braun PA, et al. Preventing caries in preschoolers: successful initiation of an innovative community-based clinical trial in Navajo Nation Head Start. Contemp Clin Trials. 2014;37(2):242–251. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2014.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Diaz-Linhart Y, Silverstein M, Grote N, et al. Patient Navigation for Mothers with Depression who Have Children in Head Start: A Pilot Study. Soc Work Public Health. 2016;31(6):504–510. doi: 10.1080/19371918.2016.1160341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Silverstein M, Diaz-Linhart Y, Grote N, Cadena L, Cabral H, Feinberg E. Harnessing the Capacity of Head Start to Engage Mothers with Depression in Treatment. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2017;28(1):14–23. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2017.0003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(6):377–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nelson S, Milgrom P. Minority participation in a school-based randomized clinical trial of tooth decay prevention in the United States. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33(1):60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2011.09.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fagen MC, Flay BR. Sustaining a school-based prevention program: results from the Aban Aya Sustainability Project. Health Educ Behav. 2009;36(1):9–23. doi: 10.1177/1090198106291376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee JA, Heberlein E, Pyle E, et al. Evaluation of a Resiliency Focused Health Coaching Intervention for Middle School Students: Building Resilience for Healthy Kids Program. Am J Health Promot. 2021;35(3):344–351. doi: 10.1177/0890117120959152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Siegel DM, Aten MJ, Enaharo M. Long-term effects of a middle school- and high school-based human immunodeficiency virus sexual risk prevention intervention. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(10):1117–1126. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.10.1117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anderman EM, Lane DR, Zimmerman R, Cupp PK, Phebus V. Comparing the efficacy of permanent classroom teachers to temporary health educators for pregnancy and HIV prevention instruction. Health Promot Pract. 2009;10(4):597–605. doi: 10.1177/1524839907309375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Irwin B, Mauriello D, Hemminger L, Pappert A, Kimball AB. Skin sun-acne tutorial evaluation among middle- and high-school students in central New Jersey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(3):407–412. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.11.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Love-Osborne K, Fortune R, Sheeder J, Federico S, Haemer MA. School-based health center-based treatment for obese adolescents: feasibility and body mass index effects. Child Obes. 2014;10(5):424–431. doi: 10.1089/chi.2013.0165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ferketich AK, Kwong K, Shek A, Lee M. Design and evaluation of a tobacco-prevention program targeting Chinese American youth in New York City. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(2):249–256. doi: 10.1080/14622200601080356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Robinson LA, Vander Weg MW, Riedel BW, Klesges RC, McLain-Allen B. “Start to stop”: results of a randomised controlled trial of a smoking cessation programme for teens. Tob Control. 2003;12 Suppl 4:IV26–33. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.suppl_4.iv26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sussman S, Dent CW, Stacy AW, Craig S. One-year outcomes of Project Towards No Drug Abuse. Prev Med. 1998;27(4):632–642. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun P, Sussman S, Dent CW, Rohrbach LA. One-year follow-up evaluation of Project Towards No Drug Abuse (TND-4). Prev Med. 2008;47(4):438–442. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Skara S, Rohrbach LA, Sun P, Sussman S. An evaluation of the fidelity of implementation of a school-based drug abuse prevention program: project toward no drug abuse (TND). J Drug Educ. 2005;35(4):305–329. doi: 10.2190/4LKJ-NQ7Y-PU2A-X1BK [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Coronges K, Stacy AW, Valente TW. Social network influences of alcohol and marijuana cognitive associations. Addict Behav. 2011;36(12):1305–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garcia BK, Agustin ML, Okihiro MM, Sehgal VM. Empowering ‘Ōpio (Next Generation): Student Centered, Community Engaged, School Based Health Education. Hawaii J Health Soc Welf. 2019;78(12 Suppl 3):30–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Snell P, Miguel N, East J. Changing directions: participatory action research as a parent involvement strategy. Educational Action Research. 2009;17(2):239–258. doi: 10.1080/09650790902914225 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Carrasquillo O, Lebron C, Alonzo Y, Li H, Chang A, Kenya S. Effect of a Community Health Worker Intervention Among Latinos With Poorly Controlled Type 2 Diabetes: The Miami Healthy Heart Initiative Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(7):948–954. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Northridge ME, Wu Y, Troxel AB, et al. Acceptability of a community health worker intervention to improve the oral health of older Chinese Americans: A pilot study. Gerodontology. 2021;38(1):117–122. doi: 10.1111/ger.12522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xavier D, Gupta R, Kamath D, et al. Community health worker-based intervention for adherence to drugs and lifestyle change after acute coronary syndrome: a multicentre, open, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;4(3):244–253. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00480-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Scott K, Beckham SW, Gross M, et al. What do we know about community-based health worker programs? A systematic review of existing reviews on community health workers. Hum Resour Health. 2018;16(1):39. doi: 10.1186/s12960-018-0304-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rodela K, Wiggins N, Maes K, et al. The Community Health Worker (CHW) Common Indicators Project: Engaging CHWs in Measurement to Sustain the Profession. Front Public Health. 2021;9:674858. Published 2021 Jun 22. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.674858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.State Community Health Worker Models. The National Academy for State Health Policy. Published December 10, 2021. Accessed January 21, 2022. https://www.nashp.org/state-community-health-worker-models/

- 62.van Ginneken N, Lewin S, Berridge V. The emergence of community health worker programmes in the late apartheid era in South Africa: An historical analysis. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;71(6):1110–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wilgerodt MA, Brock DM, Maughan EM. Public School Nursing Practice in the United States. 2018;34(3):232–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]