Abstract

Salmonella enterica is a major cause of foodborne illness, and the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria has led to huge pressures on public health. Phage is a promising strategy for controlling foodborne pathogens. In this study, a novel Salmonella phage vB_SalM_SPJ41 was isolated from poultry farms in Shanghai, China. Phage vB_SalM_SPJ41 was able to lyse multiple serotypes of antibiotic-resistant S. enterica, including S. Enteritidis, S. Typhimurium, S. Shubra, S. Derby, and S. Nchanga. It had a short incubation period and was still active at a temperature <80 °C and in the pH range of 3~11. The phage can effectively inhibit the growth of S. enterica in liquid culture and has a significant inhibitory and destructive effect on the biofilm produced by antibiotic-resistant S. enterica. Moreover, the phage was able to reduce S. Enteritidis and MDR S. Derby in lettuce to below the detection limit at 4 °C. Furthermore, the phage could reduce S. Enteritidis and S. Derby in salmon below the limit of detection at 4 °C, and by 3.9 log10 CFU/g and· 2.1 log10 CFU/g at 15 °C, respectively. In addition, the genomic analysis revealed that the phages did not carry any virulence factor genes or antibiotic resistance genes. Therefore, it was found that vB_SalM_SPJ41 is a promising candidate phage for biocontrol against antibiotic-resistant Salmonella in ready-to-eat foods.

Keywords: bacteriophage, antibiotic-resistant Salmonella, biocontrol, genome

1. Introduction

Salmonella enterica is one of the greatest threats to human health. Approximately 99% of human salmonellosis is caused by S. enterica, with symptoms such as diarrhea, fever, and stomach cramps [1]. It is commonly spread through contaminated food of animal origin, such as dairy products, meat, eggs, and seafood [2,3,4]. Fresh produce can be contaminated with bacterial pathogens at multiple points throughout its production and supply chain [5]. Salmonella infection has caused about 115 million illnesses and about 370,000 deaths annually worldwide, and 70–80% of bacterial food poisoning in China is caused by Salmonella [6].

However, the overuse of antibiotics on animal-derived products has led to the rise and spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB), as well as a series of problems such as drug residues and environmental pollution [7]. Given its tendency to have high rates of adaptation, the acquisition of virulence and resistance genes by S. enterica can facilitate the rapid spread of resistant S. enterica along the food chain [8]. S. enterica isolated from cabbage and lettuce in the Tamale metropolis of Ghana, was resistant to ampicillin (72.22%), erythromycin (94.44%), and ofloxacin (100%) [9]. The World Health Organization has identified antibiotic-resistant S. enterica as a critical-priority bacterium [10]. Therefore, new strategies and products for the prevention and control of antibiotic-resistant S. enterica need to be studied urgently.

Bacteriophages are viruses that can specifically adsorb and infect bacteria, with a wide range of sources and strong proliferation ability [11]. They have become the focus of attention in recent years due to their efficient bactericidal properties and the advantages of no residue. Phages that specifically eliminate target strains, regardless of target strain resistance, and are not harmful to the normal flora, are an attractive option to replace or complement other existing therapies [12]. The use of bacteriophages to control the growth of Salmonella has been reported in various food products, including but not limited to chicken [13], egg fluid [14], milk [15], and lettuce [16]. Furthermore, there have been some commercial phage products on the market, such as the phage product EcoShieldTM and Salmonelex, which are allowed to be added to foods to control contaminants such as Escherichia coli and Salmonella [17].

With the growing demand for food that is both tasty and convenient, ready-to-eat foods are becoming more and more popular. However, ready-to-eat foods may be potential sources of antibiotic-resistant Salmonella, posing a threat to food safety. Phages are a promising or effective method of removing pathogenic bacteria from raw food. Therefore, in this study, we isolated a novel phage with lytic activity against antibiotic-resistant Salmonella strains, characterized its biology, and analyzed the whole genome. The effect of this phage on the inhibition of S. Enteritidis and MDR S. Derby in lettuce and raw salmon was further investigated. Our study presented a broad-spectrum phage as a promising antibacterial agent against antibiotic-resistant Salmonella in foods.

2. Results

2.1. Isolation of Phage SPJ41 and Its Morphology

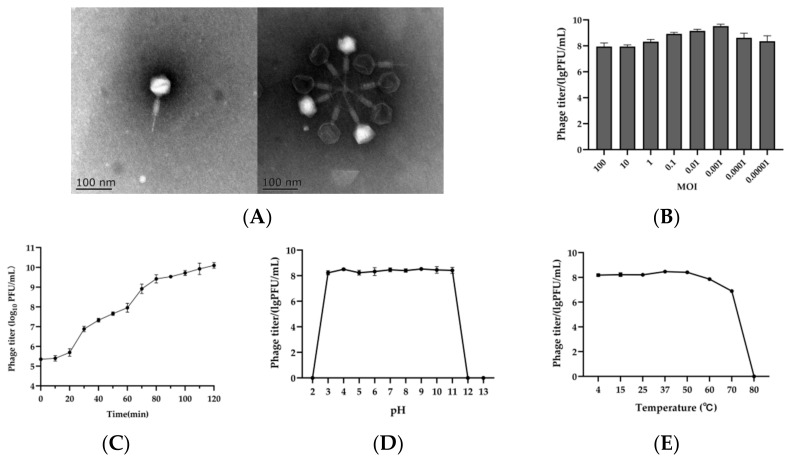

A lytic phage was isolated from chicken manure using Salmonella as a host and named vB_SalM_SPJ41. The morphology of phage SPJ41 observed by transmission electron microscopy is shown in Figure 1A. Phage SPJ41 has an icosahedral head with a diameter of 60.78 nm, a long contractile tail with a length of 110.50 nm, and a width of 17.13 nm. These morphological features indicated that it might be classified as the family Myoviridae [18].

Figure 1.

Biological characteristics of phage SPJ41. (A) Transmission electron micrographs of SPJ41. (B,C) Optimal MOI and replication curve of phage SPJ41. (D,E) Stability of SPJ41 at different pH values and temperatures.

2.2. Lysis Profiles of Phage SPJ41

The lysis profiles of phage SPJ41 are shown in Table 1. SPJ41 has a broad host spectrum, infecting 11 strains of S. enterica (5 serovars) with varying degrees of antibiotic resistance. It failed to lyse any of the non-Salmonella strains in this study. SPJ41 was able to completely lyse not only S. Typhimurium Sal4 and S. Enteritidis ATCC13076, but also multidrug-resistant (MDR) S. Derby A174 and S. Derby A176. More importantly, the phage could also play an influential lytic role, even though MDR S. Derby A63 was resistant to 12 antibiotics and MDR S. Derby A64 was resistant to 10 antibiotics.

Table 1.

Phage SPJ41 lysis profiles.

| Strains | Source | Drug Resistance d | Lytic e |

|---|---|---|---|

| Salmonella Enteritidis | |||

| ATCC13076 | ATCC a | ERY | +++ |

| A184 | Customs b | AMP, CFZ, FEP, TET, DOX, CIP, OFX, SMZ, ERY, AZM, KAN | ++ |

| Salmonella Typhimurium | |||

| Sal4 | Customs | AMP, ERY | +++ |

| A18 | Customs | AMP, DOX, SMZ, ERY, GEN | |

| Salmonella Shubra | |||

| Sal6 | Customs | AMP, TET, CHL, SMZ, ERY | ++ |

| Salmonella Derby | |||

| Sal18 | Customs | AMP, DOX, SMZ, ERY | + |

| A63 | Customs | AMP, CFZ, TET, DOX, CHL, CIP, OFX, SMZ, ERY, AZM, GEN, KAN | ++ |

| A64 | Customs | AMP, TET, DOX, CIP, OFX, SMZ, ERY, AZM, KAN, GEN | ++ |

| A174 | Customs | AMP, TET, DOX, SMZ, ERY | +++ |

| A176 | Customs | AMP, TET, DOX, SMZ, ERY | +++ |

| Salmonella Nchanga | |||

| A91 | Customs | AMP, TET, DOX, CHL, SMZ, ERY, AZM, GEN | + |

| A92 | Customs | AMP, TET, DOX, CHL, SMZ, ERY, AZM, GEN | + |

| Listeria monocytogenes | |||

| ATCC19115 | ATCC | − | |

| ATCC19116 | ATCC | − | |

| CMCC25926 | CMCC c | − | |

| Escherichia coli | |||

| ATCC25922 | ATCC | − | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | |||

| ATCC29213 | ATCC | − | |

| CMCC26003 | CMCC | − | |

a ATCC, American Type Culture Collection. b Customs, Preserved by Shanghai Customs Animal, Plant, and Food Inspection and Quarantine Technology Center. c CMCC, Shanghai Preserved Biology Company. d AMP, ampicillin; CFZ, cefazolin; FEP, cefepime; TET, tetracycline; DOX, doxycycline; CHL, chloramphenicol; CIP, ciprofloxacin; OFX, doxycycline; SMZ, sulfamethoxazole; ERY, erythromycin, AZM, azithromycin; GEN, gentamicin; KAN, kanamycin. e Lytic, +++, complete lysis; ++, lysis; +, turbid lysis; −, no plagues.

2.3. Optimal MOI and Replication Kinetic

The phage titer was the highest at an MOI of 0.001, which was significantly different from the MOI of 0.01 (p < 0.05), indicating that the optimal infection multiplicity of phage SPJ41 was 0.001 (Figure 1B). The growth curve of bacteriophage SPJ41 is shown in Figure 1C. The latent period of SPJ41 was 20 min. The curve can be divided into two phases (from 20 min to 60 min and from 60 min to 120 min). The relative burst size was calculated as approximately 255 PFU/cell in the first stage.

2.4. Stability of SPJ41 at Different pH Values and Temperatures

For the pH stability, there was no noticeable reduction in phage titer at 1 h after exposure to pH 3~11 (Figure 1D). However, when the phage was exposed to an extremely acidic or alkaline environment (pH = 2.0 or pH ≥ 12.0), no phage was detectable. Phage SPJ41 exhibited a high thermal tolerance, as manifested by its stability at 4~50 °C (Figure 1E). When the phage was cultured at 60 °C, the titer decreased slightly by 0.75 log10 PFU/mL, and at 70 °C, the phage titer decreased by 1.77 log10 PFU/mL. At a high temperature of 80 °C, the phage was undetectable. In general, phage SPJ41 exhibited good temperature tolerance (<80 °C) and wide pH stability (pH 3~11).

2.5. Genomic Characterization of SPJ41

The genome of bacteriophage SPJ41 was sequenced, which revealed a linear dsDNA sequence with 89,584 bp and a GC content of 38.76%. Meanwhile, we found three ncRNAs in the genome of phage SPJ41, including two introns and one sRNA. After the screening, the genome of SPJ41 contained 23 tRNAs, and antibiotic resistance and virulence factor genes were not detected. Meanwhile, transposition and integrase functions that promote horizontal gene transfer were not found in the SPJ4 genome. This genetic background confirms the safety of bacteriophage SPJ41 in food pathogen control and bacteriophage therapy, and that it does not integrate gene fragments into the host bacterial chromosome during its life cycle. The whole genome sequence was uploaded to the GenBank database with the accession number ON868915.1.

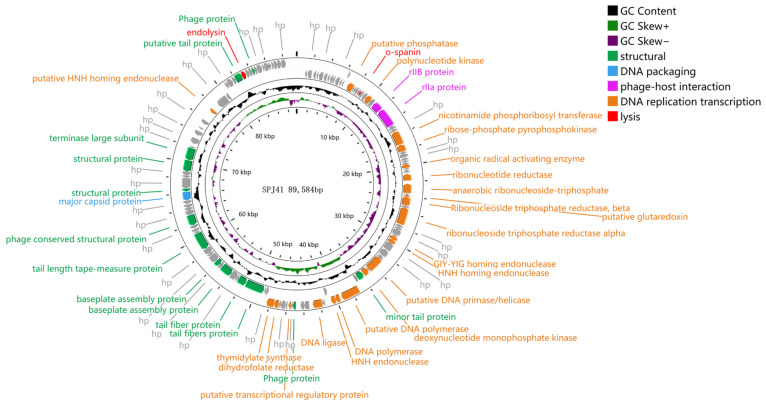

A total of 133 open reading frames (ORFs) were identified with 97 ORFs on the positive strand and 38 on the negative strand (Figure 2). The 38 ORFs were assigned functions, which were classified into five functional groups: structural protein module, packaging module, cell lysis module, phage host module, and DNA replication/modification/regulation module. The first structural protein module includes 22 ORFs: tail protein, tail fiber protein, substrate component, tape measure protein, a conserved structural protein, and major capsid protein. The second packaging module contains the terminal enzyme large subunit. The third functional group is the DNA replication recombination and regulation module, which mainly includes 11 ORFs: nucleotide metabolism regulators (deoxynucleotide monophosphate kinases, transcriptional regulatory genes, HNH homing endonucleases, thymidylate synthases, dihydrofolate reductase, anaerobic nucleotide reductase, and glutaredoxin) and DNA replication(DNA primerase/helicase, DNA polymerase, and DNA ligase). Endolysin and o-spanin belong to the fourth functional group, which is the cell lysis module. The last functional group for phage–host interactions includes the rIIa and rIIB proteins [19].

Figure 2.

Circular genome annotation of SPJ41. Circular genome maps of SPJ41 using GCview server. The rings from the inside out represent GC skew (green and purple), GC content (black), and CDS (blue). The different colored arrows represent the different functions of the predictive open reading frame (ORF): red, cell lysis module; gray, hypothetical protein; orange, DNA replication/modification/regulation; green, phage structure; blue, DNA packaging; and purple, phage–host interactions.

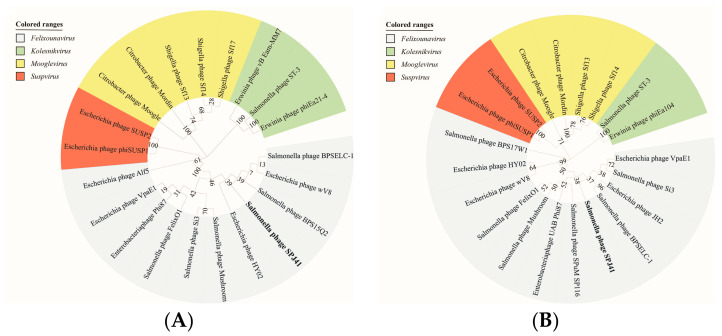

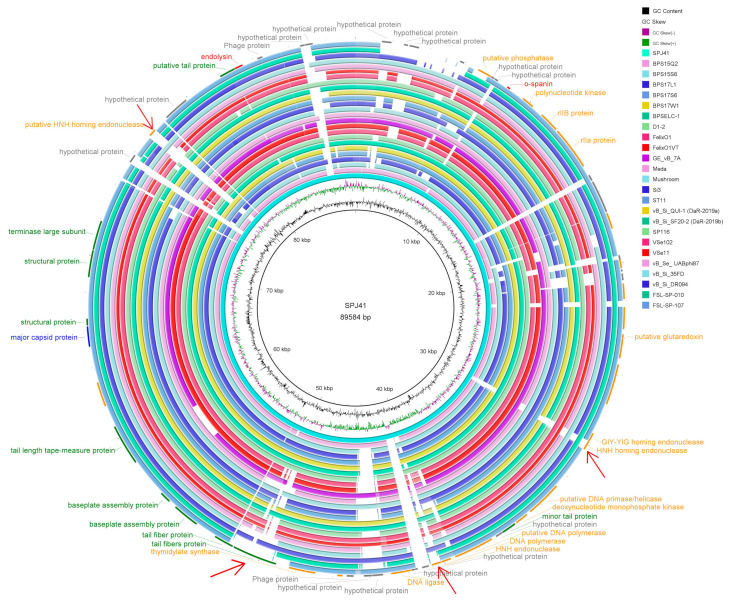

2.6. Classification and Genome Comparison of Lytic Phage SPJ41

When compared to all sequenced phages on NCBI, SPJ41 shared the highest nucleotide identity (94.00% coverage and 95.99% identity) with Salmonella phage BPSELC-1 (accession no. MN227145). BPSELC-1 is a member of the genus Felixounavirus of the subfamily Ounavirinae [20]. According to the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) classification [21], phage sequences of different genera of the Ounavirinae subfamily were downloaded from NCBI, and a phylogenetic tree was constructed with terminal enzyme large subunit and major capsid protein. Both phylogenetic trees showed that SPJ41 was classified into the Ounavirinae subfamily, Felixounavirus genus (Figure 3). To further compare the differences between phage SPJ41 and members of the genus Felixounavirus, a comparative genome circle diagram based on the Brig software is shown in Figure 4. The phage genomes of the genus Felixounavirus showed high similarity and only showed differences in some hypothetical protein regions and four functional protein regions. In the 50k bp region, these phage tail fiber proteins exhibited divergence, which correlates with the phage host range. In addition, there are differences in the three homing endonuclease (HNH endonuclease) gene sequence regions, which are site-specific enzymes for breaking DNA double strands and play a regulatory role in transcription.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic analyses of SPJ41. (A,B) Phylogenetic analyses of selected phages and phages of the proposed new genus based on the protein sequence of terminase large subunit and major capsid protein. Members of the genera Felixounavirus, Kolesnikvirus, Mooglevirus, and Suspvirus virus were illustrated with sky blue, pale green, yellow, and red, respectively.

Figure 4.

The phage comparative genome circle map of 25 strains of the genus Felixounavirus. From the inner circle to the outer circle are GC content, GC skew, reference genome SPJ41, and the phages of the genus Felixounavirus. The outermost circle is the functional annotation: red, cell lysis module; gray, hypothetical protein; orange, DNA replication/modification/regulation; green, phage structure; blue, DNA packaging; and purple, phage–host interactions. The red arrows are functional protein difference regions.

2.7. Inhibition Curves of Phage SPJ41 on Salmonella

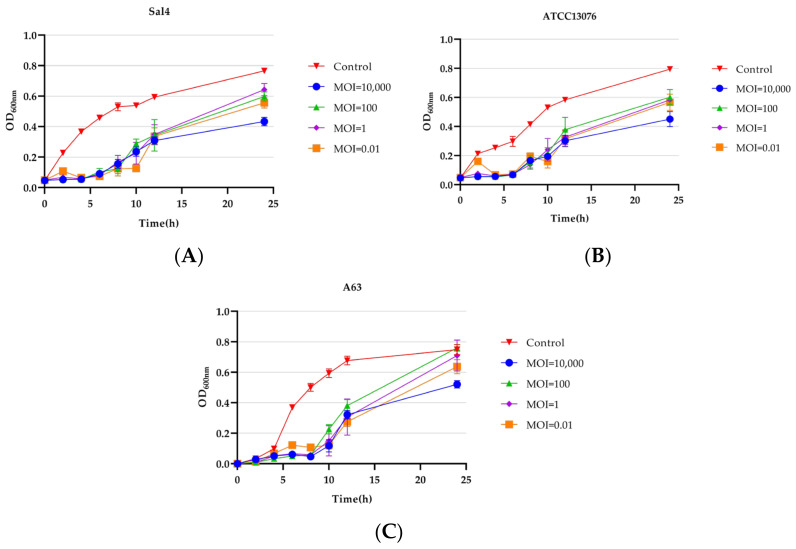

The inhibitory effect of phage SPJ41 on S. Typhimurium Sal4, S. Enteritidis ATCC13076, and MDR S. Derby A63 was evaluated in LB broth. The result is shown in Figure 5. The bacterial cell densities (OD600) of S. Typhimurium Sal4 and S. Enteritidis ATCC 13076 remained less than 0.2 until 6 h, and until 8 h for MDR S. Derby A63. In the phage treatment group, except for the MOI of 0.01, the measured OD600 value was always lower than 0.1 in the first 5 h. After incubation for 24 h, the phage-treated group with an MOI of 10,000 had the lowest bacterial cell density, which was significantly different from the other treated groups (p < 0.01).

Figure 5.

Phage SPJ41 inhibition of S. Typhimurium Sal4 (A), S. Enteritidis ATCC 13076 (B), and MDR S. Derby A63 (C).

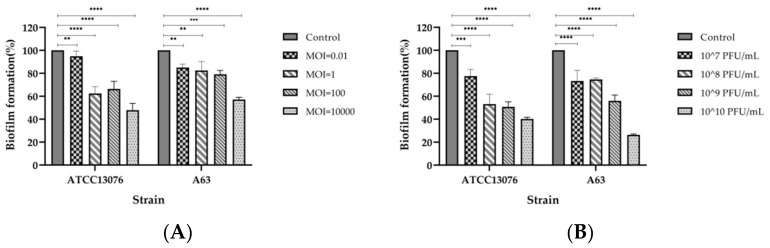

2.8. Inhibition and Disruption of Biofilms by SPJ41 Phage Treatment

Phage SPJ41 exhibited significant inhibitory and disruptive effects on the biofilm of S. Enteritidis ATCC13076 and MDR S. Derby A63 at different MOIs (Figure 6). Phage SPJ41 inhibited S. Enteritidis ATCC13076 from forming biofilms by approximately 6% to 53%. For MDR S. Derby A63, it was able to inhibit biofilm formation by 15% to 43% (Figure 6A). Biofilms formed by S. Enteritidis ATCC13076 were treated with phage SPJ41, and a 33% to 60% disruption in the attached biofilm was recorded. For MDR S. Derby A63, the attached biofilm was disrupted by 37% to 74% (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

(A) Effect of phage SPJ41 on inhibition of biofilm formation of S. Enteritidis ATCC 13076 and MDR S. Derby A63. (B) Effect of phage SPJ41 on the removal of biofilms of S. Enteritidis ATCC 13076 and MDR S. Derby A63. Statistical comparisons were performed relative to the control using the two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons test (**, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001).

2.9. Phage SPJ41 Biological Control of Salmonella in Two Ready-to-Eat Foods

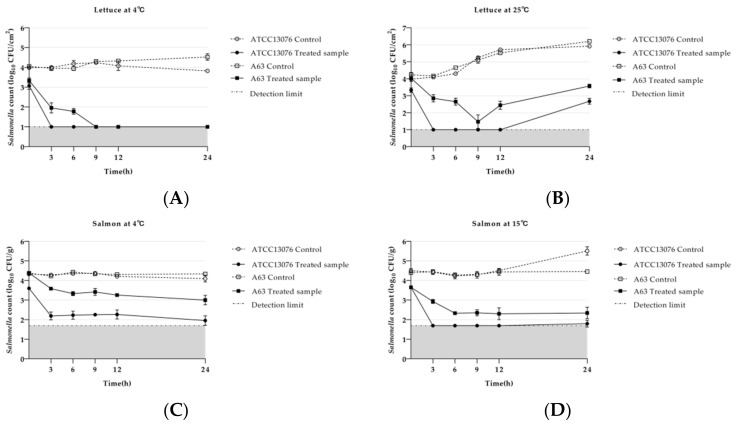

The effect of phage SPJ41 on reducing S. Enteritidis ATCC13076 and MDR S. Derby A63 on lettuce is shown in Figure 7A,B. Phage treatment reduced S. Enteritidis ATCC13076 to below the detection limit (10 CFU/cm2) at 3 h at 4 °C. However, for MDR S. Derby A63, there was a reduction of 1.9 log10 CFU/cm2 at 3 h and below the detection limit at 9 h (Figure 7A). Compared to the control, S. Enteritidis ATCC13076 and MDR S. Derby A63 on lettuce with phage SPJ41 treatment reduced 3.2 log10 CFU/cm2 and 2.5 log10 CFU/cm2 at 25 °C for 24 h (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Effect of phage SPJ41 on reducing Salmonella in lettuce. (A,B) Effect of phage SPJ41 on reducing S. Enteritidis ATCC13076 and MDR S. Derby A63 on lettuce at 4 °C and 25 °C. (C,D) Effect of phage SPJ41 on reducing S. Enteritidis ATCC13076 and MDR S. Derby A63 in salmon at 4 °C and 15 °C.

The results of phage SPJ41 reducing S. Enteritidis ATCC13076 and MDR S. Derby A63 on salmon are shown in Figure 7C,D. A reduction of approximately 2.2 log10 CFU/g of S. Enteritidis ATCC13076 was measured in the treated group compared to the control, incubated at 4 °C for 24 h. For MDR S. Derby A63, a decrease of approximately 0.7 log10 CFU/g and 1.1 log10 CFU/g was measured for 3 h and 24 h incubation at 4 °C, respectively (Figure 7C). S. Enteritidis ATCC 13076 on salmon treated with phage SPJ41 had viable counts below the detection limit (50 CFU/g) at 15 °C for 6~12 h. After treatment for 24 h, S. Enteritidis ATCC13076 decreased by 3.9 log10 CFU/g, exhibiting a remarkably significant bacteriostatic effect (p < 0.0001) at 15 °C. MDR S. Derby A63 in phage-treated salmon after 3 h and 24 h decreased by 1.5 log10 CFU/g and 2.1 log10 CFU/g, respectively, which was significantly lower than the control at 15 °C (Figure 7D).

3. Discussion

In the fight against antibiotic-resistant pathogens, there is renewed interest in phages as alternative or complementary antimicrobials [22,23,24]. In this study, a lytic phage SPJ41, subjected to a member of the genus Felixounavirus of the Ounavirinae subfamily, was isolated from chicken manure. The result of TEM showed that the morphological features of SPJ41 were similar to those of other members of the genus Felixounavirus, such as Felix O1 (73 nm diameter icosahedral head and 17 × 113 nm diameter retractable tail) and BPSELC-1 (about 83.3~91.6 nm diameter nm head and 16 × 116.6 nm diameter tail) [20,25]. The phages were observed to aggregate together, which was presumably attributable to the low sodium concentration in the phage medium [26]. Previous reports have shown that phages of the genus Felixounavirus, such as SP116 and Felix O1, were capable of infecting several different serovars of Salmonella [27,28]. The phage SPJ41 isolated in this study was also able to lyse five Salmonella serotypes, including S. Typhimurium, S. Enteritidis, S. Shubra, S. Derby, and S. Nchanga. And most of these strains were antibiotic-resistant Salmonella. In particular, the phage SPJ41 can lyse S. Derby A63, resistant to 12 kinds of antibiotics, which was increasing in fresh foods [29]. This indicated that the phage SPJ41 was a promising candidate to control the MDR S. enterica.

Phages with short incubation periods are more suitable for biocontrol because they can lyse more bacteria in a certain time [30]. The replication kinetic curve of phage SPJ41 was determined with an optimal MOI of 0.001, and the results showed that the latent period was 20 min, and the burst size was 255 PFU/cell. The latent period was similar to that of phage Felix O1 (20 min), but the burst size was larger than that of Felix O1 [28]. Phage SPJ41 exhibited good temperature tolerance (<80 °C) and broad pH stability (pH 3~11). Compared with the Salmonella phage reported previously [14,31], phage SPJ41 showed higher tolerance to an extreme environment, being naturally resistant to harsh physicochemical environmental influences, making it more beneficial as a biocontrol agent in food and processing environments [32].

Based on morphological observation and genome comparison, SPJ41 belongs to the subfamily Ounavirinae. Phage SPJ41 is a linear dsDNA sequence with a genome size of 89,584 bp. The genome sizes found here were in the range reported by the Felixounavirus genus, which described a wide range of sizes from approximately 83,000 to 90,000 bp [33]. In the genome of SPJ41, endolysin, o-spanin, and dihydrofolate were found. Dihydrofolate reductase reduces 7,8-dihydrofolate to tetrahydrofolate and acts as a cofactor in the conversion of dUMP to dTMP by thymidylate synthase enzyme [34]. Endolysin and o-spanin belong to the fourth functional group, the cell lysis module. Spanins are phage lysis proteins that act together to form a bridge between i-spanin and o-spanin [35]. While only o-spanin genes were found in SPJ4, further studies are needed to understand the function of spanins in these phages. The SPJ41 genome contains 23 tRNAs, and studies have shown that tRNAs play an important role in the synthesis of phage coat and tail proteins [36]. The genetic background confirms the safety of bacteriophage SPJ41 in food pathogen control and bacteriophage therapy, and it does not integrate gene fragments into the host bacterial chromosome during its life cycle.

When compared to all sequenced phages on NCBI, SPJ41 shared the highest nucleotide identity (90.23%) with Salmonella phage BPSELC-1. According to the ICTV [21], the main species classification standard for bacterial and archaeal viruses is 95% genome similarity. Thus, SPJ41 isolated in this study was a new species of Felixounavirus. The genomes revealed a high similarity in the phage genomes of the genus Felixounavirus according to the mapping of the comparative genomic circles. However, phages of the genus Felixounavirus showed considerable diversity in the tail fiber protein because the bacterial receptor of this genus corresponds to liposaccharides, which is a molecule with high variability [33,37]. Barron-Montenegro [33] found that the genomes of phages of the genus Felixounavirus distributed in different geographical locations are highly conserved, while the tail fibers show considerable diversity. Interestingly, we also found differences in the HNH homing endonuclease, which plays a regulatory role in transcription. HNH homing endonucleases are site-specific enzymes that disrupt DNA duplexes, allowing insertion or mobilization of genes, and play an important role in the evolution of the Siphovirus genome [25,33].

Ready-to-eat food is a potential source of antibiotic-resistant Salmonella that poses a threat to food safety. In addition to S. Enteritidis, S. Derby serovars have recently been found to be more common [29]. Phages have previously been used to control antibiotic-resistant Salmonella on lettuce [15], milk [38], and egg fluid [14]. In this study, phage SPJ41 was able to reduce S. Enteritidis ATCC13076 and MDR S. Derby A63 in lettuce to below the detection limit at 4 °C by 3.2 log10 CFU/cm2 and 2.5 log10 CFU/cm2 at 25 °C, respectively, which was nearly three times higher than that reported by Guo et al. [39]. Phage SPJ41 reduced S. Enteritidis ATCC13076 and MDR S. Derby A63 on salmon by about 2.2 log10 CFU/g and 1.1 log10 CFU/g at 4 °C, respectively. Finally, at 15 °C, it reduced S. Enteritidis ATCC13076 and MDR S. Derby A63 on salmon by 3.9 log10 CFU/g and 2.1 log10 CFU/g, respectively. At the inoculum level of 104 CFU/g in salmon, phage SLMP1 at a dose of 108 PFU/g could reduce approximately 1.5 to 2.5 log CFU/g of Salmonella counts compared with the control [40]. Therefore, phage SPJ41 was effective in controlling antibiotic-resistant S. enterica in ready-to-eat foods.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacteria Strains and Culture Conditions

A total of 12 antibiotic-resistant S. enterica strains representing five serotypes (S. Enteritidis, S. Typhimurium, S. Shubra, S. Derby, and S. Nchanga) and six non-Salmonella bacterial strains were used in this study (Table 1). A total of 12 antibiotic-resistant S. enterica exhibited varying degrees of antibiotic resistance, nine of which were antibiotic-resistant strains. S. Derby A63 was the most resistant, and it was resistant to 12 antibiotics (AMP, CFZ, TET, DOX, CHL, CIP, OFX, SMZ, ERY, AZM, GEN, and KAN). S. Derby A64 was resistant to 11 antibiotics (AMP, TET, DOX, CIP, OFX, SMZ, ERY, AZM, KAN, and GEN). All strains were used for phage lytic range determination. S. Typhimurium Sal4 was used as a host strain for phage isolation, propagation, and purification. To carry out bacterial cultures, each strain was cultured by picking an isolated colony from Luria–Bertani agar (LB, Land Bridge Technology, Beijing, China) plate, and then inoculated into Luria–Bertani broth at 37 °C overnight with agitation at 200 rpm.

4.2. Bacteriophage Isolation and Purification

Phage was isolated from chicken stool in Shanghai, China, using the method described previously by Cao et al. [41]. Briefly, 25 g of sample was mixed homogeneously with 40 mL of LB broth, supplemented with 350 μL of 1 M CaCl2, and inoculated with 1 mL of Salmonella suspension (109 CFU/mL). After incubation at 37 °C overnight, the medium was centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 15 min (5424, Eppendorf AG 22331, Hamburg, Germany). The supernatant was filtered with a 0.22 μm pore (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) size syringe filter, and the presence of lytic phage in the sample was confirmed by spot testing. A district plaque was observed and suspended in 1 mL of salt magnesium (SM) buffer for purification. The phages were purified at least three times to create phage stock, using a double-layer agar technique [42].

4.3. Determination of Phage Host Range

The host range of the isolated phage was determined by the spot test method as described elsewhere with some modifications [27]. Ten microliters of a suspension containing phage particles (109 PFU/mL) were dropped on the surface of lawn cultures of selected 12 S. enterica and six non-Salmonella strains. The plates were observed for the appearance of the clear zone after incubation at 37 °C overnight.

4.4. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) of SPJ41

The enriched phages were purified by cesium chloride density gradient centrifugation. Twenty microliters of purified phage solution (109 PFU/mL) was added dropwise to copper mesh and fixed for 10 min, and the residual liquid was absorbed by filter paper. Then, 2% phosphotungstic acid was added to the stain for 2 min. The sample was dried in a sterilized biosafety cabinet and observed by a transmission electron microscope (Philips, Eindhoven, The Netherlands).

4.5. Optimal Multiplicity of Infection (MOI) Determination

The MOI of the phage was determined using the method described previously by Li et al. with minor modifications [20]. Briefly, the phage and its host cells were mixed at 10:1, 1:1, 1:10, 1:100, 1:1000, 1:10,000, and 1:100,000, respectively. Then, the mixture was added to 5 mL of fresh LB medium and incubated with shaking at 37 °C for 4 h. The culture was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm (5424, Eppendorf AG 22331, Hamburg, Germany) for 5 min and filtered using 0.22 µm filters. The phage titer was determined using the double-layer agar method. The group with the highest titer was the optimal MOI for phage.

4.6. Replication Kinetic Curve of Phage SPJ41

A one-step growth curve experiment was performed according to the method described by Yi et al. with modifications [43]. Briefly, S. Typhimurium Sal4 was infected with the phage at the optimal MOI of 0.001 and incubated at 37 °C for 15 min without shaking. The mixture was centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 15 min in a bench-top centrifuge (5810R, Eppendorf, Avanti J-26XP, Germany) and the supernatant was discarded. The bacteria–phage pellet was washed with SM buffer and resuspended in 10 mL of fresh LB, followed by incubation at 37 °C with shaking at 200 rpm. Samples were taken at 10 min intervals, then immediately diluted, and plated for phage titer quantification. Relative burst size = (phage titer at the end of the burst cycle − initial phage titer)/initial phage titer.

4.7. pH and Temperature Stability of Phage SPJ41

To evaluate the pH stability of phage SPJ41, 100 μL of phage suspension (109 PFU/mL) was transferred into 900 μL of SM buffer at different pH values (pH 2–13, adjusted using NaOH or HCl). The phage suspensions were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. To access the temperature stability of phage SPJ41, 100 μL of the phage suspensions (108 PFU/mL) were incubated at 4, 15, 25, 37, 50, 60, 70, and 80 °C for 60 min. To measure the pH or temperature stability of phage SPJ41, the phage titers were tested after incubating using the double-layer agar plate method.

4.8. Phage SPJ41 Genome Sequencing, Annotation, and Comparison

Phage DNA was subjected to phenol/chloroform DNA extraction [41]. Libraries of different inserts were constructed using the whole-genome shotgun (WGS). Paired-end (PE) sequencing of these libraries was performed on the Illumina NovaSeq sequencing platform using next-generation sequencing (NGS). De novo assembly of high-quality next-generation sequencing data was performed using A5-miseq v20160825 [44] and SPAdesv3.12.0 [45] to construct contig sequences. GeneMarkS v4.32 (http://topaz.gatech.edu/GeneMark/) [46] software was used to perform gene prediction on the whole gene sequence, and protein-coding genes were functionally annotated based on the non-redundant database (NR) on NCBI. The tRNAscan-SE [47] was used to predict tRNA genes in the genome. The Antibiotic Resistance Database (ARDB, https://card.mcmaster.ca/analyze/rgi accessed on 1 April 2022) and Virulence Factor Database (VFDB http://www.mgc.ac.cn/VFs/ accessed on 1 April 2022) were used to analyze antibiotic resistance and virulence factor, respectively. Phage gene maps were constructed using GCview server [48].

Phylogenetic analyses of the phage major capsid protein and terminase large subunit were also performed using MEGA 7 [14] and further refined using the website evolview (https://evolgenius.info//evolview-v2/#login accessed on 20 June 2022). The overall DNA sequence homolog was defined as coverage multiplied by identity according to the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) [21]. Subsequently, phage SPJ41 and other phages of the genus Felixounavirus were compared and visualized with highly similar specific sequence fragments using BRIG, with parameters set by default.

4.9. Inhibition Curve of Bacteriophage SPJ41 against Salmonella

To examine the inhibitory activity of phage SPJ41, we incubated the phage with liquid cultures of S. Typhimurium Sal4, S. Enteritidis ATCC 13076, and MDR S. Derby A63 at MOIs of 0.01, 1, 100, and 10,000 for 24 h. An amount of 100 μL of suspension (106 CFU/mL) of bacterial broth was mixed with 100 μL of phage SPJ41 lysate at different MOIs. The experimental group without phage and only bacterial culture was set as the control group, and the phage and bacterial culture were not added to the blank group. At 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 24 h, the OD600 value was measured by a microplate reader to monitor bacterial growth.

4.10. Effect of Phage SPJ41 against Salmonella Biofilms

Phage SPJ41 inhibited and disrupted S. Enteritidis ATCC 13076 and MDR S. Derby A63 biofilms as previously described in García et al. [49] and Xie et al. [50] with minor modifications. To inhibit the formation of biofilm, 100 μL of Salmonella suspension (106 CFU/mL) was added to a 96-well polystyrene microplate, followed by 100 μL of phage liquid at different MOIs (10,000, 100, 1, and 0.01) and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. For the disrupted biofilm, 200 μL (1 × 106 CFU/mL) of Salmonella was added to sterile 96-well plates and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h to form biofilm. The planktonic cells were washed with PBS, and a liquid medium containing different concentrations of phage (1 × 107, 1 × 108, 1 × 109, and 1 × 1010 PFU/mL) was added and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The cultures were removed, and the 96-well plates were washed three times with PBS and placed in an oven to air dry at 40 °C for 30 min. Then, 200 μL of 0.1% crystal violet was added and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Excess crystal violet was washed off. An amount of 200 μL of absolute ethanol was added and dissolved at 37 °C for 5 min, and the OD570 value was measured with a microplate reader.

4.11. Effect of Phage SPJ41 against Salmonella in Food Samples

Lettuce and salmon, purchased from the Nong Gong Shang Supermarket in Shanghai, China, were sliced aseptically in the laboratory. Lettuce and salmon samples were inoculated with S. Enteritidis ATCC13076 and MDR S. Derby A63 followed by phage addition described by Xu et al. [19] and Guo et al. [39,40].

The inner leaves of the lettuce were disinfected with 75% ethanol and UV-treated, then cut into a 1 cm × 1 cm square using a sterile knife. Sterility was ensured by cultivation on TSA agar. The lettuce samples were inoculated with 10 μL of Salmonella suspension to achieve a viable count of approximately 1 × 104 CFU/cm2 and left at room temperature for 10 min. Then, 10 μL of phage solution was added to the final titer to 1 × 108 PFU/cm2. PBS buffer instead of phage fluid was used as a control. Aliquots were extracted after 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 h of incubation at 4 °C and 25 °C and suspended in 1 mL sterile PBS buffer solution. The suspension samples were homogenized for 2 min, and then the viable bacterial count (CFU/mL) was determined by serial dilution plate counting.

Fresh salmon meat was aseptically cut into slices (2 × 2 cm, ~1 g). Subsequently, 20 μL of Salmonella suspension (1 × 106 CFU/mL) was inoculated onto the surface of the salmon fillets and adhered at room temperature for 10 min. An amount of 20 μL of phage SPJ41 (1 × 1010 CFU/mL) was added to the salmon fillets to make a final dose of 2 × 108 PFU/g. All samples were prepared in triplicate after incubation at 4 °C and 15 °C for 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 h, collected and resuspended in 5 mL PBS. The suspension was vortexed and homogenized for 2 min, and the number of viable bacteria (CFU/mL) was determined.

4.12. Statistical Analysis

All experiments in this study were repeated three times. The data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and the differences were analyzed with two-way ANOVA using GraphPad Prism 9.0. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we isolated and characterized a novel lytic phage vB_SalM_SPJ41 from chicken manure. Phage SPJ41 tolerates high temperatures and extreme pH, and exhibits a broad lysis profile (11/12). Genome comparison revealed that phage SPJ41 is a new member of the genus Felixounavirus of the subfamily Ounavirinae. In addition, the phage does not carry any virulence factor genes or antibiotic resistance genes. It can effectively control the growth of antibiotic-resistant S. enterica in two ready-to-eat foods. Therefore, phage SPJ41 can be used as a candidate biocontrol agent to inhibit antibiotic-resistant S. enterica in the processing and preservation of ready-to-eat foods.

Author Contributions

Methodology, X.S.; software, T.L.; investigation, H.C., J.Z. and Z.T.; data curation, T.L.; writing—original draft preparation, T.L.; writing—review and editing, X.S. and W.L.; supervision, Y.Z.; project administration, X.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Sequences generated in this study are publicly available at ncbi. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Shanghai Agriculture Applied Technology Development Program, China (Grant No. 2019-02-08-00-10-F01149).

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Jajere S.M. A review of Salmonella enterica with particular focus on the pathogenicity and virulence factors, host specificity and antimicrobial resistance including multidrug resistance. Vet. World. 2019;12:504–521. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2019.504-521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Popa G.L., Papa M.I. Salmonella spp. Infection—A continuous threat worldwide. Germs. 2021;11:88–96. doi: 10.18683/germs.2021.1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim S., Chang Y. Anti-Salmonella polyvinyl alcohol coating containing a virulent phage PBSE191 and its application on chicken eggshell. Food Res. Int. 2022;162:111971. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2022.111971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheng L.N., Wang L.X. The microbial safety of fish and fish products: Recent advances in understanding its significance, contamination sources, and control strategies. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021;20:738–786. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rahman M., Alam M.U., Luies S.K., Kamal A., Ferdous S., Lin A.D., Sharior F., Khan R., Rahman Z., Parvez S.M., et al. Contamination of Fresh Produce with Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria and Associated Risks to Human Health: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022;19:360. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19010360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seif Y., Kavvas E., Lachance J.C., Yurkovich J.T., Nuccio S.P., Fang X., Catoiu E., Raffatellu M., Palsson B.O., Monk J.M. Genome-scale metabolic reconstructions of multiple Salmonella strains reveal serovar-specific metabolic traits. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:3771. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06112-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michael G.B., Schwarz S. Antimicrobial resistance in zoonotic nontyphoidal Salmonella: An alarming trend? Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2016;22:968–974. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monte D.F., Lincopan N., Fedorka-Cray P.J., Landgraf M. Current insights on high priority antibiotic-resistant Salmonella enterica in food and foodstuffs: A review. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2019;26:35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cofs.2019.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adzitey F. Antibiotic resistance of Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica isolated from cabbage and lettuce samples in Tamale metropolis of Ghana. Int. J. Food Contam. 2018;5:7. doi: 10.1186/s40550-018-0068-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tacconelli E., Carrara E., Savoldi A., Harbarth S., Mendelson M., Monnet D.L., Pulcini C., Kahlmeter G., Kluytmans J., Carmeli Y., et al. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: The WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018;18:318–327. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30753-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.LeLièvre V., Besnard A., Schlusselhuber M., Desmasures N., Dalmasso M. Phages for biocontrol in foods: What opportunities for Salmonella sp. control along the dairy food chain? Food Microbiol. 2019;78:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2018.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alsaadi A., Imam M., Alghamdi A.A., Alghoribi M.F. Towards promising antimicrobial alternatives: The future of bacteriophage research and development in Saudi Arabia. J. Infect. Public Health. 2022;15:1355–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2022.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wattana P., Kitiya V. Combined effects of Salmonella phage cocktail and organic acid for controlling Salmonella Enteritidis in chicken meat. Food Control. 2022;133:108653 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Z., Ma W., Li W., Ding Y., Zhang Y., Yang Q., Wang J., Wang X. A broad-spectrum phage controls multidrug-resistant Salmonella in liquid eggs. Food Res. Int. 2020;132:109011. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li J., Li Y., Ding Y., Huang C., Zhang Y., Wang J., Wang X. Characterization of a novel Siphoviridae Salmonella bacteriophage T156 and its microencapsulation application in food matrix. Food Res. Int. 2021;140:110004. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2020.110004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Islam M.S., Yang X., Euler C.W., Han X., Liu J., Hossen M.I., Zhou Y., Li J. Application of a novel phage ZPAH7 for controlling multidrug-resistant Aeromonas hydrophila on lettuce and reducing biofilms. Food Control. 2021;122:107785. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2020.107785. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper I.R. A review of current methods using bacteriophages in live animals, food and animal products intended for human consumption. J. Microbiol. Methods. 2016;130:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2016.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ackermann H.W. Frequency of morphological phage descriptions in 1995. Arch. Virol. 1996;141:209–218. doi: 10.1007/BF01718394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simoliunas E., Vilkaityte M., Kaliniene L., Zajanckauskaite A., Kaupinis A., Staniulis J., Valius M., Meskys R., Truncaite L. Incomplete LPS Core-Specific Felix01-Like Virus vB_EcoM_VpaE1. Viruses. 2015;7:6163–6181. doi: 10.3390/v7122932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li P., Zhang X., Xie X., Tu Z., Gu J., Zhang A. Characterization and whole-genome sequencing of broad-host-range Salmonella-specific bacteriophages for bio-control. Microb. Pathog. 2020;143:104119. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2020.104119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adriaenssens E.M., Sullivan M.B., Knezevic P., van Zyl L.J., Sarkar B.L., Dutilh B.E., Alfenas-Zerbini P., Łobocka M., Tong Y., Brister J.R., et al. Taxonomy of prokaryotic viruses: 2018-2019 update from the ICTV Bacterial and Archaeal Viruses Subcommittee. Arch. Virol. 2020;165:1253–1260. doi: 10.1007/s00705-020-04577-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodea G.E., González-Villalobos E., Medina-Contreras O., Castelán-Sánchez H.G., Aguilar-Rodea P., Velázquez-Guadarrama N., Hernández-Chiñas U., Eslava-Campos C.A., Balcázar J.L., Molina-López J. Genomic characterization of two bacteriophages (vB_EcoS-phiEc3 and vB_EcoS-phiEc4) belonging to the genus Kagunavirus with lytic activity against uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Microb. Pathog. 2022;165:105494. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2022.105494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oliveira H., Pinto G., Oliveira A., Noben J.-P., Hendrix H., Lavigne R., Łobocka M., Kropinski A.M., Azeredo J. Characterization and genomic analyses of two newly isolated Morganella phages define distant members among Tevenvirinae and Autographivirinae subfamilies. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:46157. doi: 10.1038/srep46157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chegini Z., Khoshbayan A., Vesal S., Moradabadi A., Hashemi A., Shariati A. Bacteriophage therapy for inhibition of multi drug-resistant uropathogenic bacteria: A narrative review. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2021;20:30. doi: 10.1186/s12941-021-00433-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whichard J.M., Weigt L.A., Borris D.J., Li L.L., Zhang Q., Kapur V., Pierson F.W., Lingohr E.J., She Y.-M., Kropinski A.M., et al. Complete Genomic Sequence of Bacteriophage Felix O1. Viruses. 2010;2:710–730. doi: 10.3390/v2030710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Szermer-Olearnik B., Drab M., Mąkosa M., Zembala M., Barbasz J., Dąbrowska K., Boratyński J. Aggregation/dispersion transitions of T4 phage triggered by environmental ion availability. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2017;15:32. doi: 10.1186/s12951-017-0266-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bao H., Shahin K., Zhang Q., Zhang H., Wang Z., Zhou Y., Zhang X., Zhu S., Stefan S., Wang R. Morphologic and genomic characterization of a broad host range Salmonella enterica serovar Pullorum lytic phage vB_SPuM_SP116. Microb. Pathog. 2019;136:103659. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2019.103659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuhn J., Suissa M., Chiswell D., Azriel A., Berman B., Shahar D., Reznick S., Sharf R., Wyse J., Bar-On T., et al. A bacteriophage reagent for Salmonella: Molecular studies on Felix 01. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2002;74:217–227. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(01)00682-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang X., Huang J., Wu Q., Zhang J., Yang S., Wang J., Ding Y., Chen M., Xue L., Wu S., et al. Occurrence, serovars and antibiotic resistance of Salmonella spp. in retail ready-to-eat food products in some Chinese provinces. LWT. 2022;154:112699. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2021.112699. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abedon S.T. Selection for bacteriophage latent period length by bacterial density: A theoretical examination. Microb. Ecol. 1989;18:79–88. doi: 10.1007/BF02030117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fong K.R., LaBossiere B., Switt A.I.M., Delaquis P., Goodridge L., Levesque R.C., Danyluk M.D., Wang S.Y. Characterization of Four Novel Bacteriophages Isolated from British Columbia for Control of Non-typhoidal Salmonella in Vitro and on Sprouting Alfalfa Seeds. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8:2193. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Binetti A.G., Quiberoni A., Reinheimer J.A. Phage adsorption to Streptococcus thermophilus. Influence of environmental factors and characterization of cell-receptors. Food Res. Int. 2002;35:73–83. doi: 10.1016/S0963-9969(01)00121-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barron-Montenegro R., Garcia R., Duenas F., Rivera D., Opazo-Capurro A., Erickson S., Moreno-Switt A.I. Comparative Analysis of Felixounavirus Genomes Including Two New Members of the Genus That Infect Salmonella Infantis. Antibiotics. 2021;10:806. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10070806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lundin D., Torrents E., Poole A.M., Sjöberg B.-M. RNRdb, a curated database of the universal enzyme family ribonucleotide reductase, reveals a high level of misannotation in sequences deposited to Genbank. BMC Genom. 2009;10:589. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cahill J., Young R. Phage Lysis: Multiple Genes for Multiple Barriers. Adv. Virus Res. 2019;103:33–70. doi: 10.1016/bs.aivir.2018.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Savalia D., Westblade L.F., Goel M., Florens L., Kemp P., Akulenko N., Pavlova O., Padovan J.C., Chait B.T., Washburn M.P., et al. Genomic and Proteomic Analysis of phiEco32, a Novel Escherichia coli Bacteriophage. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;377:774–789. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.12.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lindberg A.A. Studies of a Receptor for Felix 0-1 Phage in Salmonella Minnesota. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1967;48:225–233. doi: 10.1099/00221287-48-2-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park H., Kim J., Kim H., Cho E., Park H., Jeon B., Ryu S. Characterization of the lytic phage MSP1 for the inhibition of multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serovars Thompson and its biofilm. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2023;385:110010. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2022.110010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guo Y., Li J., Islam M.S., Yan T., Zhou Y., Liang L., Connerton I.F., Deng K., Li J. Application of a novel phage vB_SalS-LPSTLL for the biological control of Salmonella in foods. Food Res. Int. 2021;147:110492. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2021.110492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu D., Jiang Y., Wang L., Yao L., Li F., Zhai Y., Zhang Y. Biocontrol of Salmonella Typhimurium in Raw Salmon Fillets and Scallop Adductors by Using Bacteriophage SLMP1. J. Food Prot. 2018;81:1304–1312. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-17-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cao Y., Zhang Y., Lan W., Sun X. Characterization of vB_VpaP_MGD2, a newly isolated bacteriophage with biocontrol potential against multidrug-resistant Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Arch. Virol. 2021;166:413–426. doi: 10.1007/s00705-020-04887-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang C., Virk S.M., Shi J., Zhou Y., Willias S.P., Morsy M.K., Abdelnabby H.E., Liu J., Wang X., Li J. Isolation, Characterization, and Application of Bacteriophage LPSE1 Against Salmonella enterica in Ready to Eat (RTE) Foods Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:1046. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yi Y., Abdelhamid A.G., Xu Y., Yousef A.E. Characterization of broad-host lytic Salmonella phages isolated from livestock farms and application against Salmonella Enteritidis in liquid whole egg. LWT. 2021;144:111269. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2021.111269. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coil D., Jospin G., Darling A.E. A5-miseq: An updated pipeline to assemble microbial genomes from Illumina MiSeq data. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:587–589. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bankevich A., Nurk S., Antipov D., Gurevich A.A., Dvorkin M., Kulikov A.S., Lesin V.M., Nikolenko S.I., Pham S., Prjibelski A.D., et al. SPAdes: A new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012;19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blake J.D., Cohen F.E. Pairwise sequence alignment below the twilight zone. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;307:721–735. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kortright K.E., Chan B.K., Koff J.L., Turner P.E. Phage Therapy: A Renewed Approach to Combat Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria. Cell Host Microbe. 2019;25:219–232. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2019.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stothard P., Wishart D.S. Circular genome visualization and exploration using CGView. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:537–539. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.García-Heredia A., García S., Merino-Mascorro J., Feng P., Heredia N. Natural plant products inhibits growth and alters the swarming motility, biofilm formation, and expression of virulence genes in enteroaggregative and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Food Microbiol. 2016;59:124–132. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xie T., Liao Z., Lei H., Fang X., Wang J., Zhong Q. Antibacterial activity of food-grade chitosan against Vibrio parahaemolyticus biofilms. Microb. Pathog. 2017;110:291–297. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Sequences generated in this study are publicly available at ncbi. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available.