Abstract

Xenorhabdus nematophilus, a gram-negative bacterium, is a mutualist of Steinernema carpocapsae nematodes and a pathogen of larval-stage insects. We use this organism as a model of host-microbe interactions to identify the functions bacteria require for mutualism, pathogenesis, or both. In many gram-negative bacteria, the transcription factor ςS controls regulons that can mediate stress resistance, survival, or host interactions. Therefore, we examined the role of ςS in the ability of X. nematophilus to interact with its hosts. We cloned, sequenced, and disrupted the X. nematophilus rpoS gene that encodes ςS. The X. nematophilus rpoS mutant pathogenized insects as well as its wild-type parent. However, the rpoS mutant could not mutualistically colonize nematode intestines. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a specific allele that affects the ability of X. nematophilus to exist within nematode intestines, an important step in understanding the molecular mechanisms of this association.

All eukaryotes interact with microbes in relationships that can be benign, beneficial, or detrimental to one or both organisms. Research to elucidate the molecular mechanisms of host-microbe interactions has focused primarily on pathogenic relationships. Less well studied are the long-term mutualistic relationships of microbes that are intimately associated with plant or animal hosts. Recent studies have suggested that pathogens and mutualists use similar molecular strategies to interact with their hosts. For example, both pathogenic and mutualistic bacteria use type III secretion systems to deliver proteins directly into host cells and initiate specific host cell responses (13, 38). The mutualistic association between Vibrio fischeri bacteria and Euprymna scolopes squid also bears a striking resemblance to the interactions between pathogens and immune systems (28). The squid produces a halide peroxidase that converts hydrogen peroxide into hypohalous acid, a microbicidal compound that may help kill pathogens (46). V. fischeri requires a periplasmic catalase, which can prevent hypohalous acid formation, to competitively colonize the squid. This scenario mirrors the competition typically associated with pathogenic bacterium-host interactions, and yet V. fischeri and E. scolopes live together in a mutually beneficial relationship (43). If the molecular cross-talk between host and microbe is fundamentally similar in mutualistic and pathogenic relationships then one must raise the following question: what mechanisms distinguish these two relationships?

The gram-negative γ-proteobacterium Xenorhabdus nematophilus possesses specific relationships with two types of eukaryotic hosts: a species-specific mutualistic relationship with the nematode Steinernema carpocapsae and a pathogenic relationship with a wide range of insect species (11). X. nematophilus resides as a mutualistic symbiont in a specialized intestinal vesicle of the free-living stage of the nematode. Together, the nematode and its X. nematophilus symbionts infect, kill, and reproduce inside the larval stage of many insects (21). X. nematophilus is primarily responsible for killing the insect host; it produces exo- and endotoxins to which the insect succumbs within 48 h of infection (7, 10). Once inside an insect host, X. nematophilus also expresses proteases and lipases that likely degrade insect host tissues into smaller products that can be utilized by the nematode (3, 11). Thus, X. nematophilus represents both bacterial symbionts that form stable relationships with hosts and bacterial pathogens that invade and kill hosts.

Investigations of the molecular mechanisms of mutualism and pathogenicity in a single organism should provide insights into both beneficial and detrimental interactions of microbes with their plant and animal hosts. X. nematophilus is particularly well suited for such experimental studies because: (i) it is genetically and technically tractable; (ii) it can be cultivated under laboratory conditions in the absence of its eukaryotic hosts; and (iii) its mutualistic and pathogenic interactions with its hosts can be assayed separately and easily. Thus, each aspect of the host-microbe interaction can be dissected and analyzed individually. In addition, insect hosts such as Galleria mellonella (wax moth) and Manduca sexta (tobacco hornworm) can be maintained inexpensively. Nematodes can also be propagated easily; 105 nematodes can be generated from the infection of a single insect host, and bacterium-free nematode eggs can be isolated and grown on selected lawns of bacteria in the absence of an insect host.

Like many bacteria that interact with plant or animal hosts, X. nematophilus presumably possesses the capacity to adapt to and exploit host environments because it can sense and respond to changes in nutrient availability, pH, osmolarity, temperature, oxygen, carbon dioxide, and nitrogen (16). In many gram-negative bacteria, the transcription factor ςS mediates, in part, the response to these factors. ςS controls a regulon that can mediate stress resistance, survival, or host interactions. For example, in Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5, ςS is required for survival on plant surfaces and affects biocontrol antibiotic production (40). The ςS of the insect pathogen Serratia entomophila controls expression of an insect toxin (15). Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium ςS controls expression of spv virulence genes necessary for systemic infection (36) and appears to be important for S. enterica serovar Typhimurium colonization of gut-associated lymphoid tissue of mice (33).

We have investigated the possibility that ςS might mediate X. nematophilus mutualistic and/or pathogenic functions. We isolated, sequenced, and disrupted rpoS, the gene that encodes ςS in X. nematophilus. We determined that the X. nematophilus rpoS mutant is at least as virulent as its wild-type parent and reproduces as well as the wild type in insecta. In contrast, the rpoS mutant fails to colonize nematode intestines. To our knowledge, this work represents the first characterization of a gene that affects the ability of X. nematophilus to exist within nematode intestines and provides insight into the processes that mediate this interaction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

X. nematophilus strains used were ATCC 19061 and its rpoS mutant derivative, HGB151. Escherichia coli strains used were ZK918 (4) harboring an rpoS::kan insertion, DH5α (Bethesda Research Laboratories, Gaithersburg, Md.) for plasmid maintenance, and S17-1λpir (42) for conjugations.

A 1.9-kb fragment of X. nematophilus DNA containing the rpoS gene and flanking regions was amplified by PCR (primers XNBAUP [5′GCGGGATCCAAAAATATCTACAGCAA3′] and XnHind [5′GCGAAGCTTCACTGTTCCAGCATATCAT3′]) and cloned into the EcoRV site of pBCSK+ (Stratagene) to give pBCrpoS or into plasmid pCR 4-TOPO (Invitrogen) to give plasmid pTOPrpoS. An EcoRV site located in the coding region of rpoS was used to insert a kanamycin resistance (kan) cassette from mini-Tn10-kan (45) into pTOPrpoS to create pTOPrpoS::kan. pTOPrpoS::kan was digested with EcoRI to isolate the rpoS::kan DNA with its flanking regions, blunt ended with Klenow enzyme and cloned into the EcoRV site of pKR100 to give plasmid prpoS::kan. Plasmid pKR100 (kindly provided by Karen Visick, Loyola University of Chicago, Chicago, Ill.) was derived from pGP704(pJM703.1) (30) by replacing the PstI bla-containing fragment with the chloramphenicol transacetylase gene of pACYC184.

Bacterial media and growth conditions.

Permanent stocks of all strains were maintained at −80°C in Luria-Bertani medium (LB) broth (29) supplemented with 15% (vol/vol) glycerol or 10% (vol/vol) dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma). X. nematophilus was grown at 30°C in LB that either had been stored in the dark or was supplemented with 0.1% (wt/vol) pyruvate (48). E. coli strains were grown at 30°C in LB. rpoS complementation experiments were performed on MacConkey-lactose agar (Difco). Dye uptake was analyzed on NBTA (14). The following supplements were added when required: ampicillin (150 μg/ml), kanamycin (50 μg/ml for E. coli and 20 μg/ml for X. nematophilus), and chloramphenicol (30 μg/ml). To monitor CFU, cultures were serially diluted in M63 salts (29) and plated on LB. To support nematode growth, X. nematophilus was plated on lipid agar (LA; 8 g of nutrient broth, 5 g of yeast extract, 2 g of MgCl2, 7 ml of corn syrup [Karo], 4 ml of corn oil [Sigma], and 15 g of Bacto Agar [Difco] per liter) and incubated for 24 h before addition of nematodes (see below).

DNA manipulations.

Chromosomal DNA preparations, ligations, electrophoresis, E. coli transformation and electroporation, and Southern blotting were carried out by standard procedures (39). Plasmid DNA was isolated with Quantum Prep kits (Bio-Rad). Plasmids were introduced into X. nematophilus by conjugal transfer (12) or transformation (49). Restriction enzymes and DNA-modifying enzymes were obtained from Promega. For sequencing the 3′ flanking region of rpoS, arbitrary PCR was performed as described elsewhere (6), with −20GAP as the first-round primer (5′GTGTGCCAGCTCTCTTGCA3′) and −20END as the second-round primer (5′AGAGTGCGTCAGATTCAAGT3′).

Genomic library construction.

X. nematophilus chromosomal DNA was sonicated and size fractionated by gel purification to give a pool of fragments between 2 and 10 kb. These fragments were ligated to SfiI linkers and cloned into pAC215 (provided by Andrew Camilli, Tufts University) digested with SfiI (24).

Isolation of a plasmid encoding rpoS from X. nematophilus.

The library was introduced into strain ZK918, which lacks functional ςS and therefore appears white on MacConkey-lactose agar. Red transformants were tested for catalase activity by monitoring bubbling upon exposure to H2O2 (51). Restriction analysis of a clone conferring positive β-galactosidase and catalase activities on ZK918 (indicating a ςS coding region present on the clone) revealed an insert of ∼1.5 kb. This plasmid, designated prpoS15, was selected for sequencing.

Sequence analysis of rpoS.

DNA sequencing was carried out by the University of Wisconsin—Madison (UW-Madison) Biotechnology Sequencing Center, sequences were analyzed with MegAlign (DNASTAR Inc.), and database searches were conducted on the National Center for Biotechnology Information BLAST server.

Construction of an rpoS insertion mutation.

An X. nematophilus mutant with a kan cassette in the rpoS coding region was created as follows. prpoS::kan was conjugated into X. nematophilus. Of 100 Kanr exconjugants tested, 11 were Cms, suggesting they had undergone allelic exchange and lost the wild-type copy of rpoS and the plasmid vehicle. This was confirmed by analyzing the size of PCR amplification products (data not shown) with primers XNBAUP and XnHind (see above). In addition, Southern hybridization was performed (data not shown) with an rpoS-specific probe (obtained by PCR amplification from pBCrpoS using the primers revgap [5′CAAGGGAAAATCCGTAA3′] and rpomia [5′AATAAAAAGGTGGGGTCCATAA3′]) or a kan-specific probe (obtained by BamHI digestion of mini-Tn10-kan). One Kanr Cms exconjugant was selected and designated HGB151.

Phenotypic assays.

Plate assays were performed for protease (2), lipase (41), and antibiotic (26) activities, with Bacillus subtilis AD623 (courtesy of Adam Driks, Loyola University of Chicago) and Micrococcus luteus (Department of Bacteriology, UW-Madison Strain Collection no. 2001) as antibiotic indicator strains. In addition, protease activity was monitored by single-dimension zymography (34). Motility on 0.25% (wt/vol) LB agar was monitored after 10 μl of 16-h LB cultures was spotted on plates. Crystal proteins in 48-h X. nematophilus cultures were visualized by phase-contrast microscopy. Outer membrane protein profiles (12) of bacteria and the ability of bacteria to attach to plastic (35) were assayed as described elsewhere.

Bacterial survival assays.

Starvation survival in LB broth was measured by taking 10-μl samples every 24 h to determine CFU/per milliliter. To monitor survival on solid media, 1 ml of 16-h X. nematophilus culture was poured uniformly over 12 sterile 13-mm MF filter membranes (Millipore) on an agar plate (LB and LA were used with similar results) and incubated at room temperature. Every 3 days, one filter was removed and its lawn was resuspended in 1 ml of M63 salts before dilution and plating. To measure sensitivity to osmotic stress or H2O2, 16-h LB cultures were washed once with M63 and resuspended in M63 with 2 mM NaCl or 10 mM H2O2, respectively. Resuspended cells were incubated at room temperature, and samples were taken at indicated times to determine CFU.

Nematode growth conditions.

S. carpocapsae (strain All) was maintained by passage through larval-stage G. mellonella (Vanderhorst Wholesale Inc., St. Marys, Ohio) and harvested on White traps (47). Nematodes were also cultivated on X. nematophilus lawns seeded with either 500 to 800 infective-juvenile-stage nematodes or 1,500 first-instar-juvenile-stage nematodes (isolation described below) and incubated at room temperature. Infective-juvenile-stage nematodes were harvested from bacterial lawns by placing the agar slab in a petri dish lid floating in sterile deionized H2O. Nematode eggs were isolated from adult female nematodes as described elsewhere (44) except that the eggs were washed and resuspended in LB. The nematode eggs were incubated at room temperature for 16 h, and hatching into first-instar juveniles was visually assessed under a dissecting microscope.

Guillotine assay.

To visualize bacteria, the heads of individual infective juvenile nematodes were severed with a razor blade, causing the foregut to be extruded. Dissected nematodes were stained with 0.1% (wt/vol) crystal violet and observed by bright-field microscopy. At least 30 foreguts from each of three independent cocultivations on each strain of bacteria were observed for the presence of bacteria. To determine CFU of internal bacteria per milliliter, nematodes were surface sterilized with 2% (vol/vol) NaOCl, resuspended in 5 ml of LB, and ground in a Ten Broeck tissue grinder. The homogenate was then serially diluted and plated.

Pathogenesis assays.

M. sexta eggs (Walter Goodman [UW-Madison] or Carolina) were raised on an artificial diet (gypsy moth wheat germ agar; ICN). Third, fourth, or fifth instars were injected with bacteria as follows. Sixteen-hour cultures were washed once in M63 and then resuspended and diluted 10-fold in the same medium; cell counts were estimated by phase-contrast microscopy using a Petroff-Hausser counter. Washed cells were then further diluted in M63, and the number of CFU was determined for each dilution injected. Insects were injected with bacteria using a syringe with a 30-gauge needle (Hamilton) and then incubated at 26°C under 16 h-8 h light-dark periods with a constant supply of food. Insect death was monitored every 12 h. Percent mortality data are given for the 48-h observation since no further death occurred during an additional 7 days of observation. Bacterial growth inside M. sexta was determined by plating hemolymph samples extracted with a 30-gauge needle syringe from insect carcasses every 24 h after death.

Statistical analyses.

Arcsin-square-root-transformed mortality data were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) on grouped injection levels of bacteria (shown in Table 1) as well as regression analyses using the actual plate counts of injected bacteria (data not shown) as the independent variable. Statistical analyses of injection data were performed using SAS version 8 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, N.C.). Log-transformed in insecta bacterial growth data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA (strain and time as main factors). Statistical analyses of growth data were performed using Minitab 12.1 (Minitab Inc., State College, Pa.).

TABLE 1.

Virulence of the rpoS mutant

| Dose (CFU injected/insect) | Strain | % Mortality at 48 ha |

|---|---|---|

| 1–10 | Wild type | 12.5 ± 9.6 |

| rpoS::kan | 25 ± 26.5 | |

| 11–100 | Wild type | 30.0 ± 8.2 |

| rpoS::kan | 52.5 ± 25.0 | |

| 101–1,000 | Wild type | 56.7 ± 15.3 |

| rpoS::kan | 73.3 ± 11.6 |

Ten M. sexta larvae were injected per treatment. The means of three independent experiments are shown. Error terms represent standard deviations.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The rpoS sequence reported in this study has been submitted to GenBank under accession number AF198628.

RESULTS

Cloning and characterization of the X. nematophilus rpoS gene.

We cloned the X. nematophilus rpoS homolog by complementation in ZK918, an E. coli strain with a disrupted rpoS gene and a ςS-dependent bolAp1::lacZ fusion (4). ZK918 was transformed with an X. nematophilus chromosomal library (see Materials and Methods) and screened for red colonies on MacConkey-lactose. Red colonies were then tested for catalase activity, indicating the presence of a plasmid that encodes a functional ςS. From ∼105 colonies screened, we identified one transformant that harbored an rpoS candidate (prpoS15). prpoS15 contains an insert of ∼1.5 kb that we sequenced in its entirety on both strands. Sequence analysis revealed an open reading frame (ORF), incomplete at its 3′ end, with similarity to E. coli rpoS (31). As in E. coli, immediately upstream and in the same orientation as rpoS resides a 154-amino-acid ORF, incomplete at its 5′ end, whose predicted product shares 78% identity and 88% similarity with the C terminus of E. coli NlpD, a putative lipoprotein (20). The expected stop codon of the putative X. nematophilus nlpD gene sits 52 nucleotides upstream of the rpoS predicted translational start site.

We used arbitrary PCR to sequence the 3′ end of the X. nematophilus rpoS gene from chromosomal DNA. Based on this sequence, we predict that X. nematophilus rpoS encodes a protein of 331 amino acids with 82% identity and 91% similarity to E. coli ςS. This sequencing also revealed 39 codons of a putative ORF, incomplete at its 5′ end, 134 nucleotides downstream of the predicted rpoS stop codon and convergently transcribed. The predicted product of this ORF possesses 62% identity and 86% similarity with the C terminus of a S. enterica serovar Typhimurium hydroxylase involved in the synthesis of 2-methylthio-cis-ribozeatin in tRNA, encoded by miaE (37). The presence of a miaE homolog downstream of rpoS contrasts with the genomic organization of E. coli in which a convergently transcribed ORF of unknown function (orf454) resides downstream of rpoS (5).

Construction and phenotypic characterization of an X. nematophilus rpoS mutant.

We constructed the rpoS mutant strain HGB151 by allelic exchange with prpoS::kan, a plasmid that harbors a kan cassette inserted into rpoS (see Materials and Methods for details). The kan insertion in rpoS is unlikely to exert a polar effect on miaE because of its convergent transcription. To identify functions that might be affected by a loss of rpoS, we examined several phenotypic traits of HGB151. In our assays, the rpoS mutant produced protease, antibiotic, lipase, and crystal proteins at levels indistinguishable from those of the wild-type (data not shown). In addition, the lesion in rpoS exerted no effect on production of outer membrane proteins (including the stationary-phase-induced OpnB and OpnS proteins), exponential growth rate, stationary-phase cell morphology, or the ability to attach to an abiotic surface (data not shown). We examined motility on 0.25% (wt/vol) agar and found that the rpoS mutant reproducibly migrated farther from the point of inoculation than did the wild type. rpoS supplied from pBCrpoS restored motility to its normal pattern (data not shown).

Influence of the rpoS insertion mutation on X. nematophilus stress resistance.

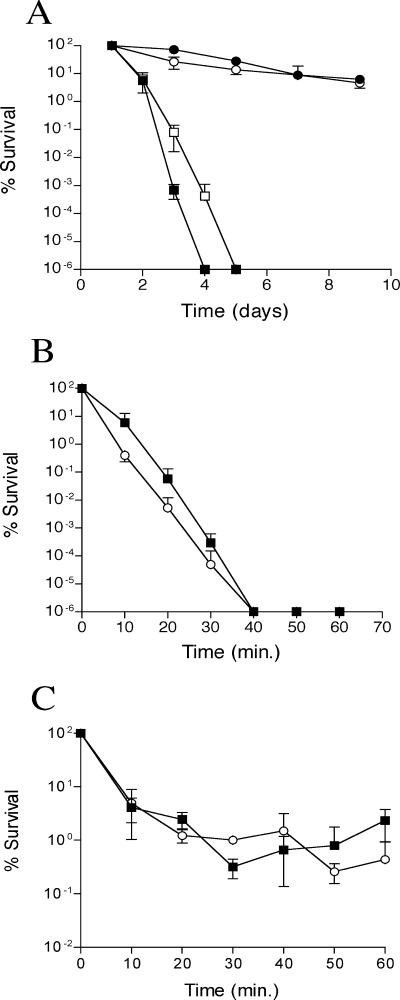

In many bacteria, disruption of rpoS causes increased sensitivity to environmental stresses such as starvation, high osmolarity, and reactive oxygen species (8, 9, 17, 18, 25, 50). For example, E. coli rpoS mutants do not survive starvation in liquid culture as well as their wild-type parents (23, 27, 32). To examine starvation survival in X. nematophilus, we monitored persistence of the rpoS mutant and its wild-type parent in liquid LB (Fig. 1A). Wild-type X. nematophilus exhibited a rapid decline in CFU/per milliliter in liquid culture; we detected no CFU by day 4 after inoculation. The rpoS mutant also had a rapid declined in CFU per milliliter but consistently survived 1 day longer than the wild type. The latter result is not unprecedented, as an rpoS mutation in Legionella pneumophila confers a reproducible delay in the decline of CFU (17).

FIG. 1.

Effect of rpoS disruption on resistance of X. nematophilus wild-type (solid symbols) and rpoS mutant (open symbols) cells to survival in liquid (squares) or on solid (circles) LB (A), 10 mM H2O2 (B), and 2 M NaCl (C). Experiments were repeated at least two times for each analysis, and error bars represent standard deviations.

To examine the role of rpoS in X. nematophilus-nematode interactions, we must culture bacteria and nematodes on a solid substrate for up to 2 weeks (see below). Therefore, we deemed it important to examine the survival of X. nematophilus during long-term culture on solid media. The viability of the rpoS mutant and wild type decreased steadily over 9 days on LB agar. Initially viability decreased faster in the rpoS mutant. However, at the time infective juvenile nematodes develop on such lawns (i.e., 7 to 9 days), wild-type and rpoS mutant cells were equally viable (Fig. 1A).

In addition to starvation survival, rpoS appears to mediate resistance to a number of other stresses in other bacteria (23). Therefore, we examined survival of both wild-type X. nematophilus and the rpoS mutant after peroxide and osmotic stress and found that the rpoS mutant was four- to sevenfold more sensitive to 10 mM H2O2 than its wild-type parent (Fig. 1B). In contrast, we detected no consistent difference between the rpoS mutant and its wild-type parent upon exposure to 2 M NaCl (Fig. 1C).

Effect of the rpoS mutation on X. nematophilus-nematode interactions.

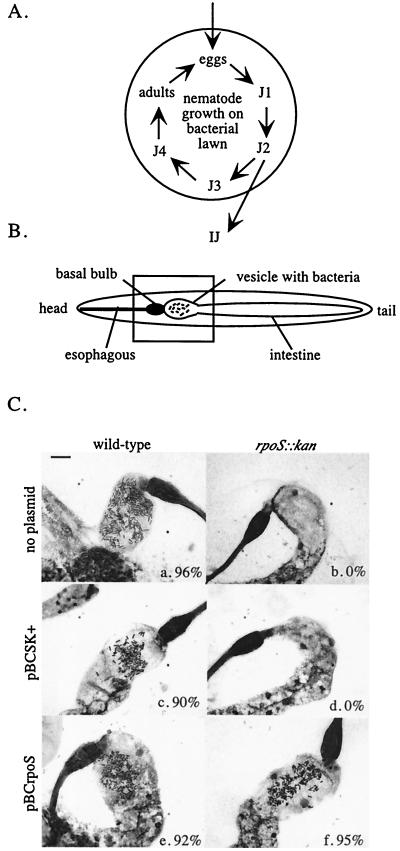

We investigated whether X. nematophilus requires rpoS to support nematode growth and/or to colonize nematode intestines. Sterile nematode eggs can hatch, develop, and reproduce on lawns of X. nematophilus bacteria (Fig. 2A). When nutrients are exhausted, nematodes develop into the infective juvenile stage (Fig. 2B) and migrate off the agar plate. Infective juvenile nematodes harbor wild-type X. nematophilus in the anterior portion of the intestine, which can be visualized by the guillotine assay (see Materials and Methods). To determine if nematodes exhibit altered growth and development on X. nematophilus lacking rpoS, we added sterile eggs to lawns of wild-type or rpoS mutant cells (Fig. 2A). Nematode development on, and the final yield of infective juvenile nematodes from, rpoS mutant lawns was indistinguishable from that obtained on wild-type lawns (data not shown), suggesting that X. nematophilus does not require ςS to support nematode development. To ascertain if X. nematophilus requires rpoS to inhabit nematode intestines, we analyzed progeny infective juvenile nematodes from in vitro cultivations for the presence of bacteria (Fig. 2C). We observed no X. nematophilus rpoS bacteria in nematode intestines; 0% of infective juvenile nematodes reared on rpoS mutant lawns carried bacteria (Fig. 2C, image b), compared to 96% of infective juvenile nematodes from wild-type lawns (Fig. 2C, image a). We confirmed this result by surface sterilizing, crushing, and plating infective juvenile nematodes for CFU. With this method we detected 55 ± 6 CFU per infective juvenile (average and standard deviation of three replicates) in nematodes cultivated on wild-type bacteria with an intact rpoS gene. In contrast, infective juvenile nematodes harvested from rpoS mutant lawns (performed in triplicate) yielded no colonies (detection limit of 0.005 CFU per infective juvenile). This result further demonstrates that X. nematophilus requires rpoS to exist in the intestines of infective juvenile nematodes.

FIG. 2.

Effect of rpoS on X. nematophilus-nematode mutualism. (A) Schematic diagram illustrating nematode cultivation on X. nematophilus lawns. The circle represents an LA petri dish seeded with a lawn of a test bacterial strain. Bacteria-free S. carpocapsae nematode eggs are applied and monitored for development through their life cycle of four juvenile stages (J1 to J4) and adults that mate and lay eggs. After multiple rounds of development, the nematodes exhaust available nutrients and develop into the alternate infective juvenile stage that migrates off the plate. (B) Schematic diagram of infective-juvenile-stage nematode morphology, with key structures indicated. The rectangle indicates the portion of the nematode's internal organs, including the normal site of bacterial colonization, which are shown in the images in panel C. (C) Microscopic images of representative intestines of infective juvenile nematodes cultivated on lawns of wild-type (a), rpoS::kan (b), wild-type/pBCSK+ (c), rpoS::kan/pBCSK+ (d), wild-type/pBCrpoS (e), and rpoS::kan/pBCrpoS (f) cells. The percentage of nematodes (out of at least 30 visible foreguts for each cocultivation) harboring bacteria is indicated within each image and represents the mean of at least three independent experiments. The size bar represents 10 μm and applies to all images in panel C.

To verify that the rpoS mutation causes the nematode colonization phenotype, we transformed plasmid pBCrpoS, which contains the wild-type rpoS gene, into the rpoS mutant and tested the ability of this strain to colonize nematode intestines. Nematodes cultivated on the rpoS mutant carrying plasmid pBCrpoS were colonized by bacteria at a similar frequency (95%) as those cultivated on the wild type (Fig. 2C, image f). In contrast, nematodes cultivated on the rpoS mutant transformed with the control plasmid, pBCSK+, carried no bacteria (Fig. 2C, image d). These data support the conclusion that X. nematophilus requires rpoS to exist in infective juvenile nematode intestines.

The rpoS mutant may be unable to reside in infective juvenile nematode intestines because ςS regulates the production of an extracellular factor necessary for colonization. If so, the rpoS mutant should obtain such a factor by cocultivation with wild-type X. nematophilus. To test this possibility, we cultivated nematodes on mixed lawns of the rpoS mutant and its wild-type parent (neither the wild type nor the rpoS mutant was at a competitive survival disadvantage in mixed lawns for the duration of the experiment [data not shown]). Ninety-five percent of the infective juvenile nematodes emerging from these mixed lawns carried bacteria (as visualized by guillotine assay of 43 nematodes), a number similar to that obtained in infective juvenile nematodes cultivated on wild-type lawns alone. This finding indicates that disruption of rpoS does not cause the synthesis of an extracellular factor that inhibits colonization. Next, we surface sterilized, crushed, and plated infective juvenile nematodes to determine the number of CFU (data not shown). Colonies formed on LB (a medium on which both wild-type and rpoS mutant cells can grow) but not on LB supplemented with kanamycin (on which only rpoS mutant cells can grow; limit of detection was 0.005 rpoS mutant CFU per infective juvenile). These results suggest that the presence of wild-type cells cannot extracellularly complement the inability of the rpoS mutant to exist in infective juvenile nematode intestines.

Effect of the rpoS mutation on virulence toward and survival within insects.

A powerful aspect of the X. nematophilus model system is that both mutualistic and pathogenic functions can be assayed separately. Thus, although the mutualism defect of the rpoS mutant prevents it from infecting insects via the nematode, the role of rpoS in virulence can still be monitored by injection. As few as 5 CFU of wild-type X. nematophilus can kill insects when injected directly into their blood (hemolymph) (11). To determine if the rpoS mutation affects X. nematophilus virulence, we injected wild-type or rpoS mutant cells into M. sexta larvae and monitored insect mortality at 48 h postinjection (Table 1). The rpoS mutant cells killed insects at least as well as the wild-type cells. ANOVA on grouped injection levels shown in Table 1 indicated no significant difference between the strains (P > 0.05), as did linear regression analysis using actual plate counts of injected bacteria (P > 0.05). However, a quadratic model best fits the data, and quadratic regression analyses suggested that the rpoS mutant causes a significantly higher percent insect mortality (for linear and quadratic components, P < 0.05). Thus, we conclude that X. nematophilus does not require rpoS to kill insects or to regulate the production of its insecticidal toxin (10). Furthermore, statistical analyses of our data suggest that rpoS may negatively affect X. nematophilus virulence toward insects.

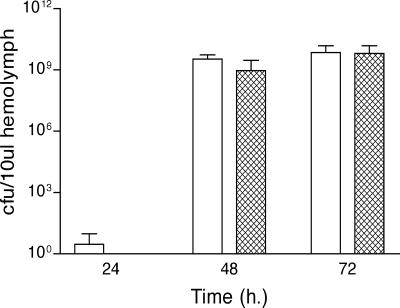

X. nematophilus does not proliferate to detectable levels within the hemolymph until after insect death (11). Therefore, it is possible that rpoS, while not required for virulence, is required for X. nematophilus to survive and/or proliferate in the insect carcass. To examine this possibility, M. sexta was killed by injection with either wild-type or rpoS mutant cells, and every 24 h after death hemolymph was removed and plated for a determination of CFU per milliliter (Fig. 3). After insect death, the rpoS mutant proliferated and survived to the same extent as did its wild-type parent, demonstrating that X. nematophilus proliferation within the insect carcass does not require rpoS.

FIG. 3.

Survival of wild-type and rpoS mutant X. nematophilus cells in M. sexta carcasses. Fifth-instar larvae of M. sexta were injected with approximately 2,000 CFU of either wild-type (white bars) or rpoS mutant (hatched bars) cells, and bacterial growth was monitored over time. Bars indicate averages; error bars indicate standard deviations. There was no significant difference between the strains (P > 0.05) (see Materials and Methods).

DISCUSSION

X. nematophilus, an insect pathogen and a nematode mutualist, functions as a resource for understanding both types of host interactions. In gram-negative bacteria, ςS, encoded by rpoS, controls regulons that can mediate stress resistance, survival, or host interactions. Here we show that a mutation in rpoS abolishes mutualistic existence of X. nematophilus in nematode intestines but not pathogenesis toward or survival within insects. This first demonstration of a defined mutation affecting the ability of X. nematophilus to exist within nematode intestines represents a significant step in elucidating the factors that mediate this association. Our findings also illustrate the ease with which the X. nematophilus system can be tested for both mutualism and pathogenesis.

X. nematophilus requires rpoS for mutualism.

The association between X. nematophilus and infective juvenile nematodes requires rpoS. However, it is unclear whether X. nematophilus requires rpoS to colonize or survive; rpoS could be required to regulate the expression of either a specific host interaction factor or genes required for stress resistance. X. nematophilus rpoS mutants survived as well as wild-type cells within insect carcasses and during starvation in LB. Therefore, while the inability of X. nematophilus rpoS mutants to colonize nematodes could be due to a decrease in stress resistance, the stress is likely to be specific to the nematode intestine. A stress survival defect could prevent initial colonization of the intestine or, alternatively, persistence within the infective juvenile nematode. Consistent with the former possibility is the fact that no X. nematophilus rpoS mutants were detected in nematodes newly emerged from the bacterial lawn, as would be expected for a persistence defect. Based on our current data, however, we cannot rule out the possibility that the X. nematophilus rpoS mutant colonizes the intestine but is eliminated prior to infective juvenile nematode emergence from the lawn. To address this question, we are monitoring the localization of green fluorescent protein-labeled X. nematophilus within nematodes.

If rpoS regulates the expression of a specific factor required or inhibitory for nematode colonization, this putative factor cannot be extracellular since the presence of wild-type bacteria could not complement the rpoS mutant, and the presence of the rpoS mutant did not affect wild-type colonization. However, the factor could be a cell surface structure that either promotes or inhibits attachment to nematode host cells.

The X. nematophilus ςS-dependent regulon.

We are currently characterizing the X. nematophilus ςS regulon to identify the ςS-dependent function(s) required for colonization. The rpoS mutation did not affect protease, lipase, and antibiotic activities or the production of crystal proteins and outer membrane proteins. Thus, genes that encode these activities or proteins are not likely members of the ςS-dependent regulon. Since the rpoS mutant exhibited four- to sevenfold-increased sensitivity to peroxide challenge (Fig. 1B), the ςS-dependent regulon may include genes whose products confer some resistance to this stress. The rpoS mutation is also associated with enhanced motility, and genes required for this function are likely regulated by ςS. Although we have not determined the underlying mechanism, enhanced motility could be due to inappropriate expression of flagella that could, in turn, inhibit colonization. For example, ectopic expression of flagella in Bordetella bronchiseptica inhibits colonization of rat trachea (1). We are therefore examining the cause of enhanced motility in the rpoS mutant and its possible link to the observed mutualism defect. The ςS-dependent regulon of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium contains genes not present in E. coli (19). Thus, the ςS-dependent regulon of any given bacterium may reflect the specific environmental challenges faced by that bacterium. If so, then the ςS-dependent regulon of X. nematophilus may include novel gene products that mediate nematode colonization.

X. nematophilus does not require rpoS for virulence.

The rpoS mutant is as virulent as and survives and proliferates as well as the wild-type parent when injected directly into the hemolymph of insect larvae. Therefore, X. nematophilus does not require rpoS to evade the insect immune system, express the insecticidal toxin (10), or utilize nutrients in the insect carcass. We found that the rpoS mutant was either as virulent as its parent or slightly more virulent, depending on the statistical analysis used. It is therefore possible that rpoS negatively regulates virulence properties in X. nematophilus. We have not yet analyzed whether the rpoS mutant possesses a competitive phenotype when coinoculated with wild-type cells. Such experiments have the potential to reveal subtle contributions of rpoS to virulence. For example, wild-type E. coli and an rpoS mutant can colonize mouse large intestines equally well when singly inoculated. However, the rpoS mutant exhibits a competitive advantage over the wild type in coinoculation experiments (22).

The development of the X. nematophilus-host interaction model will assist our dissection of molecular mechanisms that underlie both mutualism and pathogenesis, and it will provide valuable insight into the mechanisms used by bacteria to differentially sense and respond to two distinct host environments. In addition, this model can be extended to include investigations of host-response mechanisms, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the intimate associations between bacteria and animals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grant GM59776.

We owe many thanks to Harry Kaya (UC Davis), Patricia Stock (UC Davis), Steve Forst (UW-Milwaukee) (particularly for his help with outer membrane protein analyses), Alan Wolfe (Loyola University of Chicago), and members of the Ensign and Goodrich-Blair labs (UW-Madison) for experimental recommendations and useful discussions. We also thank Roberto Kolter (Harvard Medical School) for providing ZK918, Kurt Heungens, Murray Clayton, and Rick Nordheim (UW-Madison) for statistical analyses, and Karl Reich (Abbott Laboratories) for construction of pKR100.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akerley B J, Cotter P A, Miller J F. Ectopic expression of the flagellar regulon alters development of the Bordetella-host interaction. Cell. 1995;80:611–620. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90515-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boemare N, Thaler J-O, Lanois A. Simple bacteriological tests for phenotypic characterization of Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus phase variants. Symbiosis. 1997;22:167–175. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boemare N E, Akhurst R J. Biochemical and physiological characterization of colony form variants in Xenorhabdus spp. (Enterobacteriaceae) J Gen Microbiol. 1988;134:751–761. doi: 10.1099/00221287-134-7-1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bohannon D E, Connell N, Keener J, Tormo A, Espinosa-Urgel M, Zambrano M M, Kolter R. Stationary-phase-inducible “gearbox” promoters: differential effects of katF mutations and the role of ς70. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4482–4492. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.14.4482-4492.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burland V, Plunkett G I, Daniels D L, Blattner F R. DNA sequence and analysis of 136 kilobases of the Escherichia coli genome: organizational symmetry around the origin of replication. Genomics. 1993;16:551–561. doi: 10.1006/geno.1993.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caetano-Annoles G. Amplifying DNA with arbitrary oligonucleotide primers. PCR Methods Appl. 1993;3:85–92. doi: 10.1101/gr.3.2.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunphy G B, Webster J M. Lipopolysaccharides of Xenorhabdus nematophilus (Enterobacteriaceae) and their haemocyte toxicity in non-immune Galleria mellonella (Insecta: Lepidoptera) larvae. J Gen Microbiol. 1988;134:1017–1028. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eisenstark A, Calcutt M J, Becker-Hapak M, Ivanova A. Role of Escherichia coli rpoS and associated genes in defense against oxidative damage. Free Radic Biol Med. 1996;21:975–993. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(96)00154-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elias A F, Bono J L, Carroll J A, Stewart P, Tilly K, Rosa P. Altered stationary-phase response in a Borrelia burgdorferi rpoS mutant. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:2909–2918. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.10.2909-2918.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.ffrench-Constant R, Bowen D. Photorhabdus toxins: novel biological insecticides. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2:284–288. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(99)80049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forst S, Nealson K. Molecular biology of the symbiotic-pathogenic bacteria Xenorhabdus spp. and Photorhabdus spp. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:21–43. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.1.21-43.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forst S A, Tabatabai N. Role of the histidine kinase, EnvZ, in the production of outer membrane proteins in the symbiotic-pathogenic bacterium Xenorhabdus nematophilus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:962–968. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.3.962-968.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galán J E, Collmer A. Type III secretion machines: bacterial devices for protein delivery into host cells. Science. 1999;284:1322–1328. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerritsen L J M, DeRaay G, Smits P H. Characterization of form variants of Xenorhabdus luminescens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:1975–1979. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.6.1975-1979.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giddens S R, Tormo A, Mahanty H K. Expression of the antifeeding gene anfA1 in Serratia entomophila requires RpoS. Appl Env Microbiol. 2000;66:1711–1714. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.4.1711-1714.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guiney D G. Regulation of bacterial virulence gene expression by the host environment. J Clin Investig. 1997;100:S7–S10. doi: 10.1172/JCI119196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hales L M, Shuman H A. The Legionella pneumophila rpoS gene is required for growth within Acanthamoeba castellanii. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:4879–4889. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.16.4879-4889.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hengge-Aronis R. Survival of hunger and stress: the role of rpoS in early stationary phase gene regulation in Escherichia coli. Cell. 1993;72:165–168. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90655-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ibanez-Ruiz M, Robbe-Saule V, Hermant D, Labrude S, Norel F. Identification of RpoS (ςS)-regulated genes in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:5749–5756. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.20.5749-5756.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ichikawa J K, Li C, Fu J, Clarke S. A gene at 59 minutes on the Escherichia coli chromosome encodes a lipoprotein with unusual amino acid repeat sequences. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1630–1638. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.6.1630-1638.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaya H K, Gaugler R. Entomopathogenic nematodes. Annu Rev Entomol. 1993;38:181–206. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krogfelt K A, Hjulgaard M, Sørensen K, Cohen P S, Givskov M. rpoS gene function is a disadvantage for Escherichia coli BJ4 during competitive colonization of the mouse large intestine. Infect Immun. 2000;68:2518–2524. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.5.2518-2524.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lange R, Hengge-Aronis R. Identification of a central regulator of stationary phase gene expression in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:49–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee S H, Angelichio M J, Mekalanos J J, Camilli A. Nucleotide sequence and spatiotemporal expression of the Vibrio cholerae vieSAB genes during infection. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2298–2305. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.9.2298-2305.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matin A. The molecular basis of carbon-starvation-induced general resistance in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:3–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maxwell P W, Chen G, Webster J M, Dunphy G B. Stability and activities of antibiotics produced during infection of the insect Galleria mellonella by two isolates of Xenorhabdus nematophilus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:715–721. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.2.715-721.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCann M P, Kidwell J P, Matin A. The putative ς factor KatF has a central role in development of starvation-mediated general resistance in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4188–4194. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.13.4188-4194.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McFall-Ngai M J, Ruby E G. Sepiolids and Vibrios: when first they meet. BioScience. 1998;48:257–265. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller V L, Mekalanos J J. A novel suicide vector and its use in construction of insertion mutations: osmoregulation of outer membrane proteins and virulence determinants in Vibrio cholerae requires toxR. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:2575–2583. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.6.2575-2583.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mulvey M R, Loewen P C. Nucleotide sequence of katF of Escherichia coli suggests KatF protein is a novel ς transcription factor. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:9979–9991. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.23.9979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mulvey M R, Switala J, Borys A, Loewen P C. Regulation of transcription of katE and katF in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6713–6720. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.12.6713-6720.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nickerson C A, Curtis R I., III Role of sigma factor RpoS in initial stages of Salmonella typhimurium infection. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1814–1823. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.5.1814-1823.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ong K L, Chang F N. Analysis of proteins from different phase variants of the entomopathogenic bacteria Photorhabdus luminescens by two-dimensional zymography. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:834–839. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150180530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O'Toole G A, Kolter R. Initiation of biofilm formation in Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS365 proceeds via multiple, convergent signalling pathways: a genetic analysis. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:449–461. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pardon P, Popoff M Y, Coynault C, Marly J, Miras I. Virulence-associated plasmids of Salmonella serotype Typhimurium in experimental murine infection. Ann Microbiol (Paris) 1986;137B:47–60. doi: 10.1016/s0769-2609(86)80093-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Persson B C, Bjork G R. Isolation of the gene (miaE) encoding the hydroxylase involved in the synthesis of 2-methylthio-cis-ribozeatin in tRNA of Salmonella typhimurium and characterization of mutants. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7776–7785. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.24.7776-7785.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Preston G M, Haubold B, Rainey P B. Bacterial genomics and adaptation to life on plants: implications for the evolution of pathogenicity and symbiosis. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1998;1:589–597. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(98)80094-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sarniguet A, Kraus J, Henkels M D, Muehlchen A M, Loper J E. The sigma factor ςS affects antibiotic production and biological control activity of Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:12255–12259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sierra G. A simple method for the detection of lipolytic activity of micro-organisms and some observations on the influence of the contact between cells and fatty substrates. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1956;23:15–22. doi: 10.1007/BF02545855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simon R, Priefer U, Pühler A. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in gram negative bacteria. Biotechnology. 1983;1:784–791. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Visick K L, Ruby E G. The periplasmic, group III catalase of Vibrio fischeri is required for normal symbiotic competence and is induced both by oxidative stress and by approach to stationary phase. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2087–2092. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.8.2087-2092.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Volgyi A, Fodor A, Szentirmai A, Forst S. Phase variation in Xenorhabdus nematophilus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1188–1193. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.4.1188-1193.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Way J C, Davis M A, Morisato D, Roberts D E, Kleckner N. New Tn10 derivatives for transposon mutagenesis and for construction of lacZ operon fusions by transposition. Gene. 1984;32:369–379. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weis V M, Small A L, McFall-Ngai M J. A peroxidase related to the mammalian antimicrobial protein myeloperoxidase in the Euprymna-Vibrio mutualism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13683–13688. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Woodring J L, Kaya H K. Steinernematid and Heterorhabditid nematodes: a handbook of biology and techniques. Southern Cooperative Series Bulletin 331. Fayetteville, Ark: Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu J, Hurlbert R E. Toxicity of irradiated media for Xenorhabdus spp. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:815–818. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.3.815-818.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu J, Lohrke S, Hurlbert I M, Hurlbert R E. Transformation of Xenorhabdus nematophilus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:806–812. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.4.806-812.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yildiz F H, Schoolnik G K. Role of rpoS in stress survival and virulence of Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:773–784. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.4.773-784.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zambrano M M, Siegele D A, Almirón M, Tormo A, Kolter R. Microbial competition: Escherichia coli mutants that take over stationary phase cultures. Science. 1993;259:1757–1760. doi: 10.1126/science.7681219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]