Abstract

A novel fimbrial type in Escherichia coli was identified and characterized. The expression of the fimbria was associated with the O18acK1H7 clonal group of E. coli, which cause newborn meningitis and septicemia when grown at low temperature; hence, it was named the Mat (meningitis associated and temperature regulated) fimbria. The fimbriae were purified from a fimA::cat sfaA::Gm fliC::St derivative of the O18K1H7 isolate E. coli IHE 3034. The purified Mat fimbrillin had an apparent molecular mass of 18 kDa and did not serologically cross-react with the type 1 or S fimbria of the same strain. The matB gene encoding the major fimbrillin was cloned from the genomic DNA of the fimA::cat sfaA::Gm fliC::St derivative of IHE 3034. The predicted MatB sequence was of 195 amino acids, contained a signal sequence of 22 residues, and did not show significant homology to any of the previously characterized fimbrial proteins. The DNA sequence of matB was 97.8% identical to a region from nucleotides 17882 to 18469 in the 6- to 8-min region of the E. coli K-12 chromosome, reported to encode a hypothetical protein. The 7-kb DNA fragment containing matB of IHE 3034 was found by restriction mapping and partial DNA sequencing to be highly similar to the corresponding region in the K-12 chromosome. Trans complementation of the matB::cat mutation in the IHE 3034 chromosome showed that matB in combination with matA or matC restored surface expression of the Mat fimbria. A total of 27 isolates representing K-12 strains and the major pathogroups of E. coli were analyzed for the presence of a matB homolog as well as for expression of the Mat fimbria. A conserved matB homolog was found in 25 isolates; however, expression of the Mat fimbriae was detected only in the O18acK1H7 isolates. Expression of the Mat fimbria was temperature regulated, with no or a very small amount of fimbriae or intracellular MatB fimbrillin being detected in cells cultivated at 37oC. Reverse transcriptase PCR and complementation assays with mat genes controlled by the inducible trc promoter indicated that regulation of Mat fimbria expression involved both transcriptional and posttranscriptional events.

Numerous proteinaceous adhesins have been detected in Escherichia coli (for recent reviews, see references 20 and 27). These adhesins occur in the form of fimbrial filaments or are nonfimbrial proteins of the outer membrane. The adhesins recognize different receptor molecules on the mammalian epithelia or extracellular matrices and function to enable colonization of E. coli at specific ecological niches. Many of the adhesins are associated with E. coli isolates from specific disease manifestations and contribute to the establishment of the infections. Examples of such disease-associated adhesins include the P fimbria of uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) (55) and the various adhesin types detected in E. coli pathogroups causing diarrheal diseases (reviewed in references 13 and 36). Some adhesin genes, such as those encoding the mannoside-binding type 1 fimbriae (26) and the fibronectin-binding curli (39), are present on and expressed by a large proportion of natural E. coli isolates. The type 1 fimbriae are important for the spread of E. coli from one host individual to another (6) and also enhance bacterial colonization in the human and animal gut and the urinary tract (20, 27). The curli are expressed at low temperature and low osmolarity and may convey a selective advantage for E. coli in the environment and in the early phases of intestinal tract colonization (40).

The natural populations of E. coli exhibit extensive genetic diversity that is organized into a limited number of genetically distinct clonal groups (reviewed in reference 59). Such widespread, homogenous clonal groups have been well characterized in E. coli strains from separate outbreaks of disease. The isolates in the clonal groups are characterized by several identical phenotypic traits, such as serotype, biotype, phage type, outer membrane protein profiles, and production of hemolysins, other toxins, specific iron-scavenging systems, and specific adhesins. Multilocus enzyme electrophoresis has shown that isolates in a given clonal group are genetically conserved (50, 59), and the clonal groups appear sufficiently stable that they have spread into human populations on several continents. Clonal groups in pathogenic E. coli include several UPEC clones (10, 43, 55), enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC), enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC), enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC), and enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC) clones (reviewed in references 13 and 35). The association of specific adhesins with these pathogroups has resulted from horizontal gene transfer of plasmid genes or chromosomal pathogenicity islands from other pathogens. On the other hand, diversification of adhesin alleles may result from within-host evolution of E. coli, in which random point mutations affect the tissue tropism of the bacterium (52).

The O18acK1H7 isolates represent the major clonal group of E. coli associated with newborn meningitis and septicemia (MENEC) (1, 31, 51). Electrophoretic analysis of chromosomally encoded enzymes revealed that the O18acK1H7 MENEC isolates are genetically highly conserved and form a distinct clone, which is phenotypically characterized by expression of the S and the type 1 fimbriae and a conserved outer membrane protein profile, as well as, on the other hand, by lack of the P and the type 1C fimbriae and hemolysin (1, 31, 51). In this report, we describe a novel fimbrial gene that is common in E. coli isolates, including laboratory K-12 strains, but is expressed only in O18acK1H7 MENEC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria, growth conditions, and plasmids.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work are listed in Table 1. For expression studies, the bacteria were cultivated in static Luria broth at 20 or 37°C and under shaking at 37°C for other purposes. Antibiotics, when necessary, were added at concentrations of 100 (ampicillin), 25 (chloramphenicol), 30 (gentamicin [Gm]), 75 (rifampin [Rif]), 100 (streptomycin [Sm] and streptothricin [St]), or 12.5 (tetracycline) μg ml−1. The antibiotics were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co, St Louis, Mo., except for streptomycin and streptothricin, which were a gift from Helmuth Tschäpe, Robert Koch Institute, Wernigerode, Germany. Induction of mat genes in recombinant E. coli strains was done with 5 μM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (Promega Corporation, Madison, Wis.).

TABLE 1.

E. coli strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference | Presence of matBa | Expression of Mat fimbriaeb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||||

| IHE 3034 | 018:K1:H7, MENEC | 31, 51 | + | + |

| IHE 3035 | 018:K1:H7, MENEC | 31, 51 | + | + |

| IHE 3040 | 018:K1:H7, MENEC | 31, 51 | + | + |

| IHE 3047 | 018:K1:H7, MENEC | 31, 51 | + | + |

| IHE 3080 | 018:K1:H7, MENEC | 31, 51 | + | + |

| IHE 1041 | 01:K1:H7, UPEC | 55 | + | − |

| IHE 1049 | 01:K1:H7, UPEC | 55 | + | − |

| IHE 1086 | 04:K12:H7, UPEC | 55 | + | − |

| IHE 1402 | 06:K2:H1, UPEC | 55 | + | − |

| IHE 1431 | 06:K2:H1, UPEC | 55 | + | − |

| IHE 1190 | 018:K5:H7, UPEC | 55 | + | − |

| IHE 1268 | 018:K5:H7, UPEC | 55 | + | − |

| IHE 1106 | 06:K13:H1, UPEC | 55 | + | − |

| IHE 1152 | 06:K13:H1, UPEC | 55 | + | − |

| 536 | 06:K15:H31 UPEC | 16 | + | − |

| RHE 4260 | EAEC | 23, 24 | + | − |

| IHE 10162 | EAEC | KTL, Helsinki, Finland | + | − |

| ATCC 43895 | 0157:H7, EHEC | + | − | |

| IHE 53430 | 0157:H7, EHEC | 41 | + | − |

| RHE 4283 | EPEC | KTL, Helsinki, Finland | + | − |

| IHE 110156 | EPEC | KTL, Helsinki, Finland | + | − |

| RHE 3532 | ETEC | KTL, Helsinki, Finland | − | − |

| IHE 96057 | ETEC | 23, 24 | − | − |

| LE392 | K-12 | Promega | + | − |

| MG1655 | K-12 | 5 | + | − |

| AAEC072A | K-12 | 7 | + | − |

| XL1 Blue MRF′ | K-12 | Stratagene | + | − |

| IHE 3034-Sm | Streptomycin-resistant IHE 3034 | 45 | ||

| IHE 3034-2 | IHE3034 fimA::cat | 45 | ||

| IHE 3034-8 | IHE3034 sfaA::Gm | 45 | ||

| IHE 3034-59 | IHE3034 fimA::cat sfaA::Gm | 45 | ||

| IHE 3034-79 | IHE3034 fimA::cat sfaA::Gm fliC::sat | This study | ||

| IHE 3034-Rif | Rifampin-resistant IHE 3034 | This study | ||

| IHE 3034-90 | IHE 3034 matB::cat | This study | ||

| Plasmids | ||||

| pHC79 | Cosmid vector | 19 | ||

| pACYC184 | Plasmid vector | New England Biolabs | ||

| pSE380 | Expression vector, trc promoter | Invitrogen | ||

| pMAT1 | IHE3034 mat genes in ∼40 kb | This study | ||

| Sau3 AI fragment in pHC79 | ||||

| pMAT2 | 3034-79 matABC orf1, -2, and -3 in 7 kb | This study | ||

| EcoRI fragment in pACYC184 | ||||

| pMAT3 | matABC orf1, -2, and -3 in pSE380 | This study | ||

| pMAT4 | matABC in pSE380 | This study | ||

| pMAT5 | matAB in pSE380 | This study | ||

| pMAT6 | matBC orf1, -2, and -3 in pSE380 | This study | ||

| pMAT7 | matBC orf1, and -2 in pSE380 | This study | ||

| pMAT8 | matBC orf1 in pSE380 | This study | ||

| pMAT9 | matBC in pSE380 | This study | ||

| pMAT10 | matB in pSE380 | This study | ||

| pMAT11 | matC orf1, -2, and -3 in pSE380 | This study | ||

| pMMS1 | fimA::cat in pBluescript II KS+ | 58 | ||

| pIE934 | sat | 54 | ||

| pMRK1 | pla of Yersinia pestis in pSE380 | M. Kukkonen |

Detected by PCR and DNA hybridization with IHE 3034 matB as a probe.

Detected in cells cultivated at 20°C by indirect immunofluorescence microscopy and agglutination with anti-Mat fimbria antiserum.

The influence of growth conditions on expression of Mat fimbria was tested by cultivating the bacteria in static Luria broth at 20 or 37°C, as well as at 37°C in a 5% (vol/vol) CO2 atmosphere, under anaerobic conditions, in the presence of 0.2% (wt/vol) d-glucose, with a low (0.1%) or high (2%) concentration of NaCl, in the presence of 0.2 mM iron chelator 2,2-dipyridyl (Sigma Chemical Co.), or in the presence of 10% (vol/vol) human whole blood. The bacteria were passaged three times under these conditions before they were tested for Mat fimbria expression.

DNA techniques.

Isolation of plasmid and chromosomal DNA from E. coli cells and DNA manipulations were performed by routine procedures (47). Restriction enzymes (Promega Corp., Madison, Wis., and New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.) were used according to the manufacturers' instructions. Cloning of IHE 3034–79 chromosomal DNA into cosmid pHC79 was done according to the manufacturer's instructions (DNA-Packaging kit; Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany), resulting in the plasmid pMAT1. A 7-kb EcoRI fragment of pMAT1 that reacted in Southern hybridization (47) with the degenerate oligonucleotides designed on the basis of the peptide sequences obtained from MatB was subcloned into pACYC184 to give pMAT2. The DNA sequences of the degenerate oligonucleotides used in the hybridization were 5′ GCIGAIGTIACIGCICAIGCIGTIGCIACITGG 3′ and 5′ TTIGAIGTIGCIATIGAIGGIGAI 3′. The nucleotide sequence of the DNA region encoding matA and matB in pMAT2 was determined by using a commercially available sequencing service (MedProbe AS, Oslo, Norway). The matB gene in the chromosome of clinical E. coli isolates was detected by PCR with primers designed on the basis of the sequence of the matB homolog of MG1655 (5) and DyNAzyme II DNA-polymerase (Finnzymes, Espoo, Finland) according to manufacturer's instructions. The obtained PCR products were analyzed by Southern hybridization with matB gene of E. coli IHE 3034 as a probe by using the ECL enhanced chemiluminescence direct nucleic acid labeling and detection system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Amersham Place, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, England) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

For expression, DNA fragments representing different regions of the mat gene cluster were amplified by PCR with Pfu polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.), pMAT2 as a template, and primers designed on the basis of the DNA sequence of the mat region in E. coli MG1655 (5). The forward primer contained an EcoRI restriction site, and the reverse primer contained a SalI restriction site at the 5′ end. The amplified DNA fragments were cloned into the EcoRI-SalI-site of pSE380 and used in the complementation assays.

For reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR), total RNA from E. coli strains IHE 3034, IHE 3034–90, and MG1665 was extracted with Qiagen Rneasy kit, following the manufacturer's guidelines. The enhanced avian RT-PCR kit (Sigma) and a PTC-200 Peltier thermal cycler (MJ Research) were used to amplify mRNA by the two-step method according to the manufacturer's instructions. The same amounts of template RNA were used for comparing the mat transcripts; the amounts varied from 0.5 to 2.0 μg in different experiments. Specific primers corresponded to the following nucleotides of the E. coli MG1665 sequence available in GenBank (accession no. U73857): matA forward, 19117 to 19134; matA reverse, 18547 to 18569; matB forward, 18449 to 18469; matB reverse, 17882 to 18002; matC forward, 17807 to 17824; matC reverse, 17156 to 17176. Amplimers were separated by electrophoresis in a 1% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide; their relative amounts were evaluated from the gels by using the Tina (version 2.0) image analysis program (Raytest Isotopenmessgeräte Gmbh, Straubenhardt, Germany).

A fimA sfaA fliC triple mutant of IHE 3034, named IHE 3034–79, was constructed by inserting the sat gene encoding streptothricin acetyltransferase from pIE934 (54) into the NcoI site within the cat gene in a fliC::cat fusion (58) cloned to the suicide plasmid pGP704 (34). The resulting plasmid was used to silence the fliC gene of the fimA::cat sfaA::Gm derivative IHE 3034–59 (45) by allelic replacement essentially as described in reference 58. A MatB-null variant of IHE3034, named E. coli IHE 3034–90, was constructed by inserting a cat cassette encoding chloramphenicol acetyltransferase from pMMS1 (58) into the Bsu36I site in matB by the same methodology described above. The correct genotypes of IHE 3034–79 and IHE 3034–90 were confirmed by Southern hybridization with fliC and sat as DNA probes for IHE 3034–79 and matB and cat for IHE 3034–90. The correct phenotypes of IHE 3034–79 and IHE 3034–90 were confirmed by agglutination in an antiserum against H7 flagella available from previous work (58) or in an antiserum against the Mat-fimbriae obtained in this study as well as by immunoelectron microscopy (IEM).

Sequence comparisons.

Homology searches in the databases were performed with the BLAST (available at http://www.expasy.ch/sprot/sprot-top.html) and FASTA (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/fasta3/) package programs. Comparison of MatB with other fimbrillins was done by using Align for global alignment (http: //molbiol.soton.ac.uk/compute/align.html) and SIM for local alignment (http://www.expasy.ch/tools/sim-prot.html). Prediction of the presence of stem-loop structures and signal sequences in the mat genes of MG1655 and IHE 3034 was done by using programs available at http://www.fruitfly.org/seq_tools/promoter.html, http://www.genebee.msu.su/services/rna2_reduced.html, and http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/. DNA-binding motifs were identified by using the ProfileScan program at http://www.isrec.isb-sib.ch/.

Protein chemical methods.

Mat fimbriae were purified from E. coli IHE 3034–79 and E. coli LE392(pMAT1) by using deoxycholate and concentrated urea (29). Prior to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (47), the type 1 and Mat fimbriae were denaturated at low pH (33).

Protein and peptide sequencing was performed with an Applied Biosystems 494A Procise sequencer. For analysis the protein was, after SDS-PAGE, electroblotted onto a ProBlott (Applied Biosystems, Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.) membrane. For internal sequencing, the protein was digested with trypsin, the peptides generated were separated by reverse-phase chromatography, and a selected peptide was subjected to analysis (61).

Immunological methods.

The anti-type 1 fimbria and anti-Mat fimbria sera were obtained by immunizing rabbits according to standard procedures with the type 1 fimbriae purified from E. coli IHE 3034–8 and the Mat fimbriae purified from E. coli IHE 3034–79 and E. coli LE392(pMAT1) used as antigens. The rabbit antiserum raised against the S fimbriae of IHE 3034 was available from previous work (56). Polyclonal anti-Mat, anti-type 1, and anti-S fimbria sera were titrated against the purified type 1, S, and Mat fimbriae by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as described previously (30) with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated swine anti-rabbit immunoglobulins (Dako A/S, Denmark; diluted to 1:500) as secondary antibodies and phosphatase substrate (Sigma Diagnostics, Inc., St. Louis, Mo.) at a concentration of 1 mg/ml in diethanolamine-magnesium chloride buffer (OY Reagena AB, Kuopio, Finland). Results were recorded with a Multiscan MS ELISA reader (Labsystems OY, Helsinki, Finland). Western blotting of SDS-PAGE-separated fimbrial proteins with anti-Mat fimbria antibodies was done by routine procedures as described in reference 11.

Mat fimbria expression on E. coli strains was detected by indirect immunofluorescence according to the procedure described in reference 42. Briefly, the bacteria were immobilized on glass slides, fixed with 3.5% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and stained with anti-Mat fimbria antibodies diluted 1:50 and with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled swine anti-rabbit immunoglobulins (Dako A/S) diluted to 1:50. Stained bacteria were mounted in nicetamid and examined in an Olympus BX50 fluorescence microscope (Olympus Optical Co., Hamburg, Germany) equipped with epi-illumination and interference filters for FITC. For detection of Mat fimbria expression by whole-cell ELISA as described in reference 8, the bacteria were immobilized onto ELISA plates (Nunc A/S, Roskilde, Denmark) for 16 h at 37°C, washed, and left to react with anti-Mat antibodies diluted from 10−2 to 10−7, and the amount of bound antibodies was measured by ELISA as described above.

Electron microscopy.

For electron microscopy, the bacteria were suspended in Luria broth and immobilized on copper grids coated with Pioloform and carbon. For negative staining, the bacteria were stained with 1% (wt/vol) potassium tungstate (pH 6.5) for 1 min. For IEM, the bacteria were left to react with anti-Mat antibodies diluted to 1:500 in PBS and 10-nm-particle-diameter gold-labeled protein A (Amersham Life Science) diluted to 1:40 and negatively stained as described above. The grids were examined in a JEOL JEM-1200EX transmission electron microscope at an operation voltage of 60 kV. The micrographs were taken at the Section of Electron Microscopy, Institute of Biotechnology, University of Helsinki.

Hemagglutination assays.

Treatment of human O1 erythrocytes with endo-β-galactosidase, neuraminidase, trypsin, and pronase and agglutination of the erythrocytes by E. coli 3034–79 were performed by routine procedures (28).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the 6- to 8-min region of the E. coli MG1655 chromosome (5) is available at GenBank under accession no. U73857, and the sequence of the matAB region of the E. coli IHE 3034 chromosome is available under accession no. AF325731. Identity comparisons were performed with predicted protein sequences of matB and the following adhesin genes of E. coli: MG1655 fimA (9), GenBank accession no. AAC77270; PC31 fimA (25), GenBank accession no.X00981; IHE 3034 sfaA (15), GenBank accession no. S53211; J96 papA (3), GenBank accession no. X03391, K01176, X03392, X61239, and S45610; F17 a-A (32), GenBank accession no. AF022140, M36649, and M62503; MG1655 ppdD, GenBank accession no. AE000119 and U00096; K-12 csgA (40), GenBank accession no. L04979; C921b-1 cooA (44), GenBank accession no. M58550 and M37148; cooB, GenBank accession no. X62495; and LMC10 cooC and cooD (14), GenBank accession no.X76908.

RESULTS

Purification and characterization of fimbriae from the fimA sfaA fliC mutant derivative of E. coli IHE 3034.

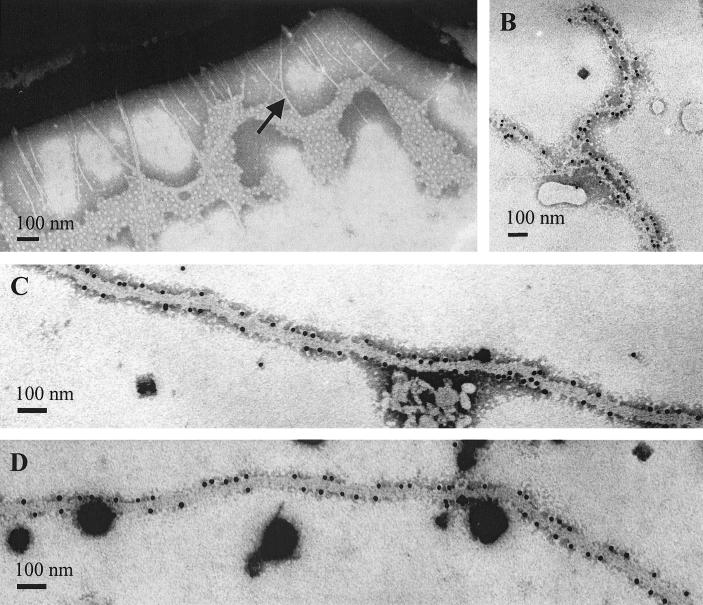

The O18acK1H7 meningitis isolate E. coli IHE 3034 and the S- and type 1-fimbria-negative double mutant IHE 3034–59 have been described earlier (15, 30, 31, 45, 51). In order to obtain a derivative that is devoid of all surface filaments, the H7 flagellin gene fliC of IHE 3034–59 was inactivated by allelic exchange with fliC::cat::sat. The sat cassette was positioned within the cat DNA because it contained a suitable NcoI restriction site. Transconjugants with the correct antibiotic markers were assessed for flagellation by agglutination in anti-H7 antiserum, and a nonflagellate mutant was isolated and named IHE 3034–79. The correct genotype of IHE 3034–79 was confirmed by Southern hybridization of PvuI-digested chromosomal DNA by using fliC and the sat cassette as probes (data not shown). Transmission electron microscopy of IHE 3034–79 cells cultivated at 20°C revealed a lack of flagella, but, unexpectedly, showed the presence of fimbrial filaments on the bacteria (Fig. 1A). The strain IHE 3034–79 was not agglutinated in antisera raised against the type 1 or S fimbriae from the same strain, indicating that the strain expressed a third fimbrial type. This fimbria had a diameter of 5 to 7 nm and was 0.4 to 5 μm in length. Because the expression of this fimbrial type was found to be associated with the major clonal group of MENEC as well as with low temperature (see below), we named it the Mat (meningitis associated and temperature regulated) fimbria.

FIG. 1.

Electron microscopy of Mat fimbriae. (A) Negatively stained cells of the fimA sfaA fliC mutant strain E. coli IHE 3034–79 cultivated at 20°C. (B to D) IEM of fimbriae from XL1 Blue MRF′ harboring pMAT3 (B), pMAT9 (C), or pMAT5 (D). Size bars, 100 nm.

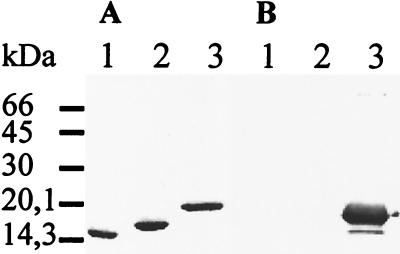

Mat fimbrial filaments were purified from strain IHE 3034–79 by using deoxycholate and concentrated urea. An SDS-PAGE analysis of the purified Mat fimbriae showed a major peptide with an apparent molecular mass of 18 kDa (Fig. 2A). The apparent molecular size of the Mat fimbrillin was larger than the apparent sizes of the FimA fimbrillin and the SfaA fimbrillin of the same strain (30, 45), which are also shown in Fig. 2A.

FIG. 2.

SDS-PAGE (A) and Western blotting (B) of the S fimbria (lane 1), the type 1 fimbria (lane 2), and the Mat fimbria (lane 3) of E. coli IHE 3034. The blotting was done with anti-MAT fimbria antiserum as primary antibodies. The migration distances of molecular mass marker proteins (size in kilodaltons) are indicated on the left.

Polyclonal antisera against Mat fimbriae purified from E. coli IHE 3034–79 and E. coli LE392(pMAT1) (see below) were raised in rabbits. In Western blotting, the antibodies detected in the Mat fimbria preparation a major peptide with an apparent molecular mass of 18 kDa as well as a minor peptide with an apparent molecular mass of 16 kDa (Fig. 2B). The antisera against the Mat fimbriae did not recognize the FimA or the SfaA proteins (Fig. 2B). In accordance, ELISA analysis of purified fimbriae showed that the Mat fimbriae did not react with the anti-S fimbria or anti-type 1 fimbria antisera; neither were the type 1 or S fimbriae recognized by the anti-Mat fimbria sera (Table 2). The reactivities of the two anti-Mat fimbriae sera were closely similar.

TABLE 2.

Cross-reaction between E. coli fimbriae

| Specificity of antiserum to E. coli fimbria | Titer of antibody to E.

coli fimbriaa

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Type 1 | S | Mat | |

| Type 1 | 4.5 | 2.4 | <2.0 |

| S | 2.1 | 4.6 | <2.0 |

| Mat | <2.0 | <2.0 | 4.1 |

Antibody titer, as tested by the ELISA, is given as the logarithm of the reciprocal of the highest dilution of the antiserum giving an A405 of 0.5.

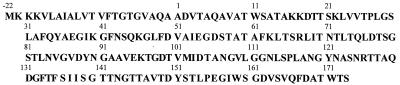

Amino acid sequencing of the Mat fimbriae gave the N-terminal sequence ADVTAQAVATWSATAKKDTTSKLVVTPLGSLAFQYAEGIK and the internal peptide sequence GLFDVAIEGDSTATAFK. These sequences do not have homologs in the FimA or SfaA sequences, nor did we find any significant homology in any other fimbrial protein sequences deposited in the SWISS-PROT data bank. It was thus concluded that the Mat fimbria represents a novel E. coli fimbrial type.

Cloning and sequencing of mat genes.

We next ligated random 40-kb fragments from the genome of 3034–79 into the cosmid cloning vector pHC79, and transfectants of E. coli LE392 expressing the Mat fimbria were identified by bacterial agglutination in anti-Mat fimbria serum and by electron microscopy. A positive recombinant was isolated, and the cosmid was named pMAT1. Cosmid pMAT1 was digested with the EcoRI restriction enzyme, and a 7-kb DNA fragment reacting in Southern hybridization with the oligonucleotide probes was identified and cloned into pACYC184, to obtain plasmid pMAT2. Electroporation of pMAT2 into E. coli LE392 gave a recombinant strain reacting with the anti-Mat-fimbria antibodies (data not shown).

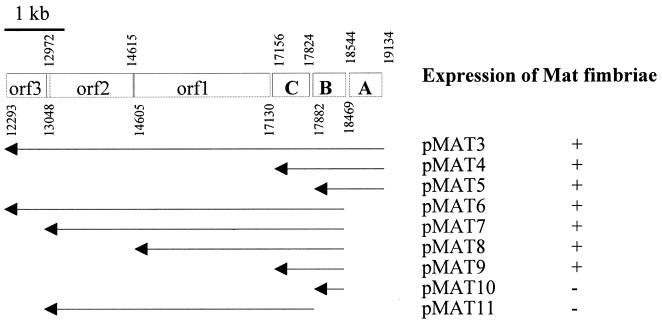

An extensive homology search revealed that the amino acid sequences obtained from the Mat fimbrillin perfectly matched the predicted amino acid sequence of an open reading frame at nucleotides 17882 to 18469 in the 6- to 8-min region of the E. coli K-12 chromosome (5). This DNA encodes a hypothetical protein of 195 amino acids, which was identical to the 57 amino acids sequenced from the Mat fimbrillin. The region surrounding the mat homolog at the 6- to 8-min region in the K-12 chromosome encodes six hypothetical proteins, which are located on a 6,841-bp DNA fragment (Fig. 3). Restriction mapping with the enzymes NcoI, NruI, PstI, PvuI, SacII, SmaI, and SnaBI of the 7-kb fragment in pMAT2 gave a pattern closely similar to the one predicted from the K-12 chromosomal sequence (details not shown). We named three of these genes matA, matB, and matC, because they appeared to affect the synthesis of Mat fimbriae (see below); matB encodes the Mat fimbrillin homolog (Fig. 3). The DNA sequence containing the matA and matB genes of IHE 3034 was determined and compared to the corresponding region in the DNA sequence of MG1655. DNA sequence identity was 93.0% in the 156-bp region upstream of matA, 97.0% within matA, 93.2% in the 74-bp intergenic region separating matA and matB, 97.8% within matB, and 98.2% in the 57-bp intergenic region between matB and matC. The mat nucleotide sequences are available from the GenBank database under accession no. AF325731.

FIG. 3.

Gene organization of the 6.8-kb fragment containing mat at the 6- to 8-min region in the chromosome of E. coli MG1665 (5). The nucleotide numbers refer to the gene location in the sequence available in GenBank (accession no. U73857). Arrows below the sequence indicate DNA fragments cloned into pSE380 and tested for in trans complementation of the matB::cat mutation in the chromosome of E. coli IHE 3034–90 as well as for expression in E. coli XL1 Blue MRF′ (on the right).

The predicted amino acid sequence of MatB of IHE 3034 is shown in Fig. 4; it contains a 22-amino-acid signal sequence and differs from the predicted sequence of the MatB homolog of E. coli MG1655 only at the position −6, which is within the signal sequence. The calculated molecular mass of mature MatB is 17,853 Da. The predicted MatB sequence of 195 amino acids exhibits 19 to 25% identity with the FimA, SfaA, PapA, F17A, PpdD, CooA, and CsgA fimbrillin sequences, with no areas of significant local identity. The MatB sequence lacks typical motifs identified in E. coli fimbrillins. The C terminus of MatB lacks the β-zipper motif recognized by fimbrial chaperones (21), and its signal sequence and N terminus are not related to those in the type IV fimbrillins (53). MatB also lacks cysteine residues and hence disulfide bonds. The predicted MatA sequence is of 196 amino acids, lacks a detectable signal sequence, and contains at residues 145 to 195 a predicted helix-turn-helix DNA-binding motif similar to the consensus pattern in the LuxR family of regulatory proteins (17).

FIG. 4.

Predicted amino acid sequence of MatB of E. coli IHE 3034. The sequence has a 22-mer signal sequence. No. 1 indicates the N-terminal amino acid residue of the mature protein. The predicted amino acid sequence from E. coli MG1665 (5) contains methionine at the position −6.

Mutagenesis, complementation, and expression of matB.

We next inactivated the matB gene of E. coli IHE 3034 by allelic exchange with a matB::cat fusion. A transconjugant with the correct antibiotic markers as well as genotype was isolated and named IHE 3034–90. The correct genotype of IHE 3034–90 was confirmed by Southern hybridization of BamHI-SacII-digested DNA by using matB and the cat cassette as probes (data not shown). The strain IHE 3034–90 did not express Mat fimbriae, as analyzed by agglutination in anti-Mat fimbriae antisera, as well as by IEM (data not shown) and whole-cell ELISA with anti-Mat fimbria antibodies (Fig. 5A).

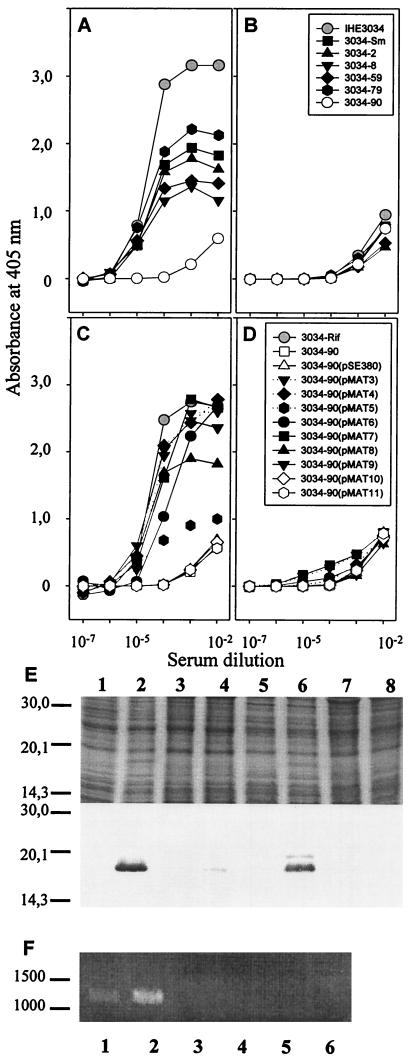

FIG. 5.

Expression of Mat fimbriae in E. coli, as analyzed by whole-cell ELISA with anti-Mat fimbriae as primary antibodies. (A and C) Expression in cells grown at 20°C. (B and D) Expression in cells grown at 37°C. (A and B) Expression is shown for the wild-type IHE 3034, the spontaneous streptomycin-resistant strain IHE 3034-Sm, the fimA::cat derivative IHE 3034–2, the sfaA::Gm derivative IHE 3034–8, the fimA::cat sfaA::Gm double mutant IHE 3034–59, the fimA::cat sfaA::Gm fliC::St triple mutant IHE 3034–79, and the matB::cat derivative IHE 3034–90. (C and D) Complementation of the matB::cat mutation in IHE 3034–90 by the pMAT-plasmids encoding regions of the putative mat gene cluster. (E) SDS-PAGE (top) and Western blotting (bottom) of cellular proteins in E. coli XL1 Blue MRF′(pSE380) (lanes 1 and 3), E. coli XL1 Blue MRF′(pMAT3) (lanes 2 and 4), E. coli IHE 3034–90(pSE380) (lanes 5 and 7), and E. coli IHE 3034–90(pMAT3) (lanes 6 and 8). The bacteria were cultivated at 20°C (lanes 1, 2, 5, and 6) or at 37°C (lanes 3, 4, 7, and 8). (F) RT-PCR of RNA from E. coli IHE 3034 (lanes 1 and 2), MG1665 (lanes 3 and 4), and IHE 3034–90 (lanes 5 and 6). The bacteria were cultivated at 37°C (lanes 1, 3, and 5) or 20°C (lanes 2, 4,and 6). Amplification was done with a primer pair specific for matBC.

Most pathogenic E. coli strains express more than one fimbrial type, and recently regulatory cross talk between fimbrial operons in E. coli was reported (60). We originally detected Mat fimbriae in the fimA sfaA fliC triple mutant, which raised the question of whether Mat fimbriae are expressed in the wild-type IHE 3034 as well. Expression levels of Mat fimbriae in IHE 3034 mutants were measured by whole-cell ELISA technology with anti-Mat fimbria antisera as primary antibodies. For screening purposes, the mutations had been introduced into a spontaneous streptomycin-resistant mutant of IHE 3034, IHE 3034-Sm (45), and it appeared that IHE 3034-Sm expressed less Mat fimbriae on the cell surface than did IHE 3034 (Fig. 5A). The mutant strains IHE 3034–2 fimA, IHE 3034–8 sfaA, IHE 3034–59 fimA sfaA, and IHE 3034–79 fimA sfaA matB did not exhibit expression levels significantly different from that shown by IHE 3034-Sm, whereas IHE 3034–90 matB reacted very poorly with the anti-Mat fimbria antibodies.

A dramatic difference in Mat fimbria expression was seen between cells cultivated in Luria broth at 20 and and those cultivated at 37°C. At the higher temperature, the bacteria exhibited a very low level of Mat fimbria expression, the reactivity with the anti-Mat antibodies being closely similar to that seen with the IHE 3034–90 cells (Fig. 5B). Indirect immunofluorescence staining of IHE 3034 grown at 20°C indicated that only a fraction of cells, ranging from 1 to 10% in different cultures, expressed Mat fimbriae on their surface (data not shown). This finding is indicative of phase variation in the Mat fimbria expression (38).

In order to analyze how many genes of the putative mat gene cluster are needed for Mat fimbria expression, the matB::cat mutation on the IHE 3034–90 chromosome was complemented in trans with pSE380 containing different fragments of the matB-containing region of pMAT2 (Fig. 3). The PCR cloning was done on the basis of the MG1655 sequence, so that in the pSE380 derivative, the mat genes were under the inducible trc promoter. The expression of the Mat fimbria was assessed with bacteria grown at 20°C by agglutination, whole-cell ELISA, and IEM with anti-Mat fimbria antibodies. Complementation with pMAT11 lacking matB did not restore Mat fimbria formation (Fig. 3), nor did the cells react in whole-cell ELISA (Fig. 5C) or in agglutination with the anti-Mat-fimbria antibodies (data not shown). Similarly, complementation with matB alone in pMAT10 did not restore the surface expression of the Mat fimbriae (Fig. 3 and 5C). A low level of Mat expression was detected in E. coli IHE 3034–90(pMAT5) complemented with the matA-B DNA, and a higher expression level was seen in cells complemented with pMAT9 containing matBC and with pMAT8 containing matB-orf1. The expression levels by the other complementation derivatives did not differ significantly from each other (Fig. 3 and 5C). Expression of the same pMAT plasmids in E. coli XL1 Blue MRF′ gave essentially similar results (data not shown). IEM did not reveal any major differences in the morphology or immunological reactivity of the fimbriae of E. coli harboring the pMAT plasmids: examples with pMAT3, pMAT 5, and pMAT9 are shown in Fig. 1.

A striking feature of the complementation assays detected with E. coli IHE 3034–90 was that the amount of Mat fimbriae expressed on the surface of the complemented strains grown at 37°C was greatly decreased, as analyzed by whole-cell ELISA (Fig. 5D). We also analyzed by Western blotting the amount of MatB in cells of E. coli IHE 3034–90(pMAT3) and XL1 Blue MRF′(pMAT3) grown at 37 and 20°C. MatB was detected in cells grown at 20°C, but only in trace amounts or not at all in cells grown at 37°C (Fig. 5E). As a control, we expressed under the trc promoter in pSE380 the pla gene (pMRK1) encoding an outer membrane protease. Analysis of expression of Pla in IHE 3034–90 by Western blotting showed expression at similar amounts at both temperatures (data not shown).

We used RT-PCR to analyze whether transcription of matB and matC is affected by temperature. DNA fragments of the expected sizes of matB (not shown) and matBC (Fig. 5F) were amplified from RNA of IHE 3034 cells grown at 20°C, and the matBC signal was weaker by 70% in cells grown at 37°C. No matB-C transcripts were detected in MG1665 or IHE 3034–90 cells at either temperature (Fig. 5F). A matA transcript was detected in all three strains grown at both temperatures, whereas PCR amplification with primer specific for matAB or matAC did not produce detectable amplimers (data not shown).

In order to detect other environmental signals besides low temperature that might influence expression of the Mat fimbria, we assessed Mat expression by E. coli strains IHE 3034, LE392, and MG1655 grown at 37°C under different conditions. The conditions included cultivation in the presence of 5% (vol/vol) CO2 atmosphere, 0.2% (wt/vol) glucose, 0.2 mM iron chelator 2,2-dipyridyl, low (0.1%) or high (2%) concentrations of NaCl, or 10% (vol/vol) human blood, as well as anaerobic conditions. None of these conditions induced detectable Mat fimbria expression.

Presence of matB and expression of the Mat fimbria in isolates of E. coli

IHE 3034 belongs to the serogroup O18acK1H7, which forms the major clonal group of MENEC. These isolates form a homogenous and distinct group of E. coli, as analyzed by several phenotypic assays and isoenzyme polymorphism (30, 31, 51). We analyzed 27 isolates representing various pathogroups of E. coli (Table 1) for the presence of matB as well as expression at 20 and 37°C of the Mat fimbria. The analyzed strains belonged to the O18K1H7 MENEC clonal group or to the clonal groups of UPEC (O1K1H7, O4K12H7, O6K2H1, O18K5H7, and O6K13H1), or they represented the diarrhea-causing pathogroups EAEC, EHEC, EPEC, and ETEC. Additionally, K-12 strains and the widely used UPEC strain 536 were analyzed. PCR and Southern hybridization showed the presence of a matB homolog in all strains except the two ETEC isolates (Table 1). The apparent size of the amplified matB fragment in the isolates was invariant and equalled the one seen in IHE 3034 (data not shown). However, expression of the Mat fimbria was detected only in the MENEC isolates grown at 20°C (Table 1).

Hemagglutination by E. coli IHE 3034–79.

Many fimbrial types of E. coli recognize specific carbohydrate sequences. In order to test whether this might be the case for the Mat fimbria as well, we assessed hemagglutination of human erythrocytes by the strain IHE 3034–79 cultivated at 20°C. No agglutination was detected; neither did enzymatic treatments known to reveal cryptic carbohydrates on the erythrocyte surface induce detectable hemagglutination.

DISCUSSION

Mat fimbria represents a novel type of E. coli fimbria that is morphologically similar to the type 1 or P fimbriae, but serologically and in a subunit sequence unrelated to the previously characterized fimbrial proteins of E. coli or other bacteria. Although the matB gene encoding the major subunit was found to be common in E. coli isolates, it was expressed on the bacterial surface only in the genetically conserved clonal group of O18acK1H7 MENEC cultivated at low temperature. The matB gene is the fourth fimbrillin gene detected in laboratory K-12 strains, which previously have been shown to harbor fim genes encoding the type 1 fimbria, the csg genes encoding curli, as well as ppdD encoding the type IV fimbrillin (5, 9,25, 40, 48). Of these, only the type 1 fimbriae are expressed by E. coli K-12 under routine laboratory conditions at 37°C. Curli expression takes place at low temperature and low osmolarity (40). It was recently found that a fraction of E. coli isolates from cases of human adult urosepsis also express curli at 37°C (4). The type IV fimbriae require an exogeneous secretion apparatus for surface expression in E. coli K-12 (49), but are expressed in EPEC that harbor the EPEC adherence factor plasmid (35, 36). The matB fimbrillin gene appears to be common in E. coli and is expressed at low temperature by isolates of a genetically distinct pathogroup.

matB encodes the major subunit of the Mat fimbria. The complete nucleotide sequence of matB was determined and the deduced protein sequence matched the sequence of 57 amino acids obtained from the Mat fimbria. The knockout matB::cat mutation abolished Mat fimbria production, which was complemented in trans by matB-containing DNA together with at least either matA or matC. The predicted sequence of MatB was not related to the fimbrillin sequences deposited in data banks and lacks the N-terminal motifs of type IV fimbrillins (53) and CsgA-related fimbrillins (12, 40). MatB also lacks cysteine residues and the C-terminal β-zipper motif of chaperone-assisted fimbrillins (21). These characteristics are also lacking in the CooA fimbrillin of the CS1 filaments and in the other fimbrillins detected on human ETEC strains (46). The fimbrillins on human ETEC share 40 to 50% sequence identity with each other, and their plasmid-borne gene clusters are closely related in gene organization (46). However, we found only 23% sequence identity between MatB and CooA, and the matA and matC gene products showed a similar low sequence identity with the four Coo proteins of the CS1 fimbria (46). The ELISAs, Western blotting, and IEM with anti-Mat fimbria antibodies showed that the Mat fimbria was immunologically distinct from the type 1 and S fimbriae expressed by MENEC. We thus conclude that the Mat fimbria represents a novel fimbrial type of E. coli. We could not detect any carbohydrate binding by the Mat fimbria and are currently analyzing the binding of Mat fimbria to epithelial cells and tissue proteins.

A matB homolog was detected in 25 of the 27 E. coli strains analyzed in this study. The analyzed isolates represented major pathogroups of E. coli as well as K-12 strains; the two matB-negative strains were ETEC isolates. The nucleotide sequence of matB of IHE 3034 was 97.8% identical to the matB from MG1665, and the matB homologs amplified from the genomic DNA of the E. coli isolates were of invariable size, also in isolates found not to express MatB. These findings indicate conservation of the matB gene in E. coli. We detected Mat fimbria expression only in the O18acK1H7 clonal group of MENEC, and it is noteworthy that the O1K1H7 isolates, which on the basis of isoenzyme polymorphism form a clonal group of E. coli strains genetically closest to the O18acK1H7 MENEC group (43, 51), did not express their matB gene under the conditions we tested.

We subcloned matB from IHE 3034–79 on a 7-kb fragment that supported Mat fimbria expression when transformed into E. coli K-12. This DNA fragment has a homolog in the MG1665 chromosome at the 6- to 8-min region and contains six putative genes (5), of which we found matA, matB, and matC affected Mat fimbria formation. The two chromosomal regions are highly similar; nucleotide sequencing showed that the matAB region was 96.6% identical for the sequenced 1,471-bp fragment, and a high level of identity of the whole 7-kb region was also evident in the restriction mapping. At present, the number of genes that are involved in Mat fimbria sythesis and regulation remains open. We also do not know whether genes located at a distance from the matB region are involved in fimbria synthesis. The fimbrial gene clusters of E. coli usually contain four or more genes needed for the structure, assembly, or regulation of the fimbrial filament (reviewed in references 20 and 27). Our complementation assays indicated that matB alone is not sufficient to confer Mat fimbria expression on E. coli XL1 or the strain IHE 3034–90 with the polar matB::cat mutation. Complementation was slightly more efficient in the matAB transformant and further increased in the matBC transformant, but was not significantly enhanced when fragments encompassing more than the matBC genes were introduced into IHE 3034 matB::cat or XL1 Blue MRF′. The RT-PCR analysis indicated that matB and matC are part of the same transcript, whereas we did not detect a matABC transcript, which suggests that matA is transcribed independently from matBC. It is noteworthy that the E. coli strain MG1665 contained a matA transcript, but we failed to amplify a matBC RNA from this strain. IEM did not reveal any major structural differences between Mat fimbrial filaments on E. coli K-12 expressing the pMAT plasmids. Western blotting of the Mat fimbriae showed the presence of a minor protein apparently smaller than MatB; its size, however, did not match those of any of the gene products from the mat region, and it may be a degradation product from MatB. On the other hand, in trans expression of mat genes in IHE 3034–90(pMAT3) showed a minor protein with an apparent size of ca. 20 kDa, which is close to the calculated size of mature MatC (22.4 kDa). The function of MatC in fimbria formation remains open. Lack of the chaperone target motif in the C terminus of MatB suggests that Mat fimbriae are not assembled by the classical chaperone-usher pathway of the P and the type 1 fimbriae (20), and the assembly mechanism of the Mat fimbria remains to be elucidated. The predicted sequence of MatA does not contain a signal sequence, whereas a putative signal sequence is present in the matB and matC gene products. The predicted MatA sequence contained a C-terminal helix-turn-helix DNA-binding motif of the LuxR family of regulatory proteins (17). This indicates that MatA may be a cytoplasmic protein functioning in regulation.

We found that transcription of matBC in IHE 3034 cells was reduced but not abolished at 37°C and that expression of mat genes from the plasmid pMAT3 with the inducible trc promoter also was temperature sensitive. These findings indicate that the temperature regulation of the mat genes involves transcriptional as well as posttranscriptional events. Expression of curli in E. coli K-12 is favored at low temperatures. The transcription of csgA is positively regulated by the RpoS sigma factor and repressed by the histone-like protein H-NS, but the temperature and osmolarity regulation of curli expression involves other factors (40). The mechanisms of the temperature regulation of Mat expression remain to be determined. Temperature is known to regulate translation by affecting mRNA conformation (2, 18) or the translational machinery itself (reviewed in reference 22). The matA sequence contains four copies of putative RNase E target sequences (37), which might become accessible upon temperature-induced conformational change. Temperature may also affect the stability of the MatB protein. The mechanisms behind the repression of mat expression in most E. coli isolates also remain open. We found by DNA sequencing and restriction mapping that the 7-kb mat regions in IHE 3034 and MG1655 are highly similar, which indicates that the lack of Mat fimbria expression in E. coli MG1655 does not result from truncation or lack of genes at this chromosomal region. E. coli IHE 3034 and another O18acK1H7 MENEC isolate were recently found to be rpoS mutants (57); whether this holds true for the entire O18acK1H7 MENEC clone and how RpoS influences mat expression are to be elucidated. RpoS is a positive regulator of curli expression, and we indeed have not detected curli expression in IHE 3034 cells cultivated at 20°C (B. Westerlund-Wikström and R. Pouttu, unpublished data). Our ongoing work has shown that silencing of rpoS does not alone lead to expression of the Mat fimbria. The regulation of the Mat fimbria expression appears complex and is particularly interesting because it seems to be a clonal property in E. coli.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Kaarina Lähteenmäki for help in initial electron microscopy and Raili Lameranta, Annu Alho, Lena Blomqvist, Ulla-Maija Nakari, Riikka Pirilä, and Suvi Simpanen for technical assistance.

This work was supported by the Sigrid Jusélius Foundation, the Academy of Finland (project no. 42103 and 42107), and the University of Helsinki.

REFERENCES

- 1.Achtman M, Mercer A, Kusecek B, Pohl A, Heuzenroeder M, Aaronson W, Sutton A, Silver R P. Six widespread bacterial clones among Escherichia coliK1 isolates. Infect Immun. 1983;39:315–335. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.1.315-335.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altuvia S, Kornitzer D, Teff D, Oppenheim A B. Alternative mRNA structure of the cIIIgene of bacteriophage λ determine the rate of its translation initiation. J Mol Biol. 1989;210:265–280. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90329-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Båga M, Normark S, Hardy J, O'Hanley P, Lark D, Olsson O, Schoolnik G, Falkow S. Nucleotide sequence of the papA gene encoding the Pap pilus subunit of human uropathogenic Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1984;157:330–333. doi: 10.1128/jb.157.1.330-333.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bian Z, Brauner A, Li Y, Normark S. Expression of and cytokine activation by Escherichia colifibers in human sepsis. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:602–612. doi: 10.1086/315233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blattner F R, Plunkett III G, Bloch C A, Perna N T, Burland V, Riley M, Collado-Vides J, Glasner J D, Rode C K, Mayhew G F, Gregor J, Wayne Davis N, Kirkpatrick H A, Goeden M A, Rose D J, Mau B, Shao Y. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coliK-12. Science. 1997;227:1453–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bloch C A, Stocker B A D, Orndorf P E. A key role for type 1 pili in enterobacterial communicability. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:697–701. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blomfield I C, McClain M S, Eisenstein B I. Type 1 fimbriae mutants of Escherichia coli K12: characterization of recognized afimbriate strains and construction of new fimdeletion mutants. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1439–1445. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boylan M, Coleman D C, Smyth C J. Molecular cloning and characterization of the genetic determinant encoding CS3 fimbriae of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Microb Pathog. 1987;2:195–209. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(87)90021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burland V, Plunkett III G, Sofia H J, Daniels D L, Blattner F R. Analysis of the Escherichia coligenome VI: DNA sequence of the region from 92.8 through 100 minutes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:2105–2119. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.12.2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caugant D A, Levin B R, Lidin-Janson G, Whittam T S, Svanborg-Edén C, Selander R K. Genetic diversity and relationships among strains of Escherichia coliin the intestine and those causing urinary tract infections. Prog Allergy. 1983;33:203–227. doi: 10.1159/000318331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coligan J E, Kruisbeek A M, Margulies D H, Shevach E M, Strober W, editors. Current protocols in immunology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collinson S K, Emödy L, Trust T J, Kay W W. Thin aggregative fimbriae from diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4490–4495. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.13.4490-4495.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frankel G, Phillips A D, Rosenshine I, Dougan G, Kaper J B, Knutton S. Enteropathogenic and enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli: more subversive elements. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:911–921. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Froehlich B J, Karakashian A, Melsen L R, Wakefield J C, Scott J R. CooC and CooD are required for assembly of Cs1 pili. Mol Microbiol. 1994;12:387–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hacker J, Kestler H, Hoschützky H, Jann K, Lottspeich F, Korhonen T K. Cloning and characterization of the S fimbrial adhesin II complex of an Escherichia coliO18:K1 meningitis isolate. Infect Immun. 1993;61:544–550. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.2.544-550.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hacker J, Schmidt G, Hughes C, Knapp S, Marget M, Goebel W. Cloning and characterization of genes involved in production of mannose-resistant, neuraminidase-susceptible (X) fimbriae from a uropathogenic O6:K15:H31 Escherichia colistrain. Infect Immun. 1985;47:434–440. doi: 10.1128/iai.47.2.434-440.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henikoff S, Wallace J C, Brown J P. Finding protein similarities with nucleotide sequence databases. Methods Enzymol. 1990;183:111–132. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)83009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoe N P, Goguen J D. Temperature sensing in Yersinia pestis: translation of the LcrF activator protein is thermally regulated. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7901–7909. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.24.7901-7909.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hohn B, Collins J. A small cosmid for efficient cloning of large DNA fragments. Gene. 1980;11:291–298. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(80)90069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hultgren S J, Jones C H, Normark S. Bacterial adhesins and their assembly. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Vol. 2. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 2730–2756. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hung D L, Knight S D, Woods R M, Pinkner J S, Hultgren S J. Molecular basis of two subfamilies of immunoglobulin like chaperones. EMBO J. 1996;15:3792–3805. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hurme R, Rhen M. Temperature sensing in bacterial gene regulation—what it all boils down to. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:1–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keskimäki M, Saari M, Heiskanen T, Siitonen A. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coliin Finland from 1990 through 1997: prevalence and characteristics of isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3641–3646. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.12.3641-3646.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keskimäki M, Mattila L, Peltola H, Siitonen A. Prevalence of diarrheagenic Escherichia coliin Finns with or without diarrhea during a round-the-world trip. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:4425–4429. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.12.4425-4429.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klemm P. The fimA gene encoding the type-1 fimbrial subunit of Escherichia coli. Nucleotide sequence and primary structure of the protein. Eur J Biochem. 1984;143:395–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1984.tb08386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klemm P, Jorgensen B J, van Die I, de Ree H, Bergmans H. The fim genes responsible for synthesis of type 1 fimbriae in Escherichia coli, cloning and genetic organization. Mol Gen Genet. 1985;199:410–414. doi: 10.1007/BF00330751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klemm P, Schembri M A. Bacterial adhesins: function and structure. Int J Med Microbiol. 2000;290:27–35. doi: 10.1016/S1438-4221(00)80102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Korhonen T K, Finne J. Agglutination assays for detecting bacterial binding specificities. In: Korhonen T K, Dawes EA, Mäkelä P H, editors. Enterobacterial surface antigens: methods for molecular characterization. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science Publishers; 1985. pp. 301–303. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Korhonen T K, Nurmiaho E L, Ranta H, Svanborg-Edén C. New method for isolation of immunologically pure pili from Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1980;27:569–575. doi: 10.1128/iai.27.2.569-575.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Korhonen T K, Väisänen-Rhen V, Rhen M, Pere A, Parkkinen J, Finne J. Escherichia colifimbriae recognizing sialyl galactosides. J Bacteriol. 1984;159:762–766. doi: 10.1128/jb.159.2.762-766.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Korhonen T K, Valtonen M V, Parkkinen J, Väisänen-Rhen V, Finne J, Ørskov F, Ørskov I, Svenson S B, Mäkelä P H. Serotypes, hemolysin production and receptor recognition of Escherichia colistrains associated with neonatal sepsis and meningitis. Infect Immun. 1985;48:486–491. doi: 10.1128/iai.48.2.486-491.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lintermans P, Pohl P, Deboeck F, Bertels A, Schlicker C, Vandekerckhove J, Van Damme J, Van Montagu M, De Greve H. Isolation and nucleotide sequence of the F17-A gene encoding the structural protein of the F17 fimbriae in bovine enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1998;56:1475–1484. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.6.1475-1484.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McMichael J C, Ou J T. Structure of common pili from Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1979;138:969–975. doi: 10.1128/jb.138.3.969-975.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller V L, Mekalanos J J. A novel suicide vector and its use in construction of insertion mutations: osmoregulation of outer membrane proteins and virulence determinants in Vibrio cholerae requires toxR. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:2575–2583. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.6.2575-2583.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nataro J P, Kaper J B. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:142–201. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.1.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nataro J P, Scaletsky L C A, Kaper J B, Levine M M, Trabulsi L R. Plasmid-mediated factors conferring diffuse and localized adherence of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1985;48:378–383. doi: 10.1128/iai.48.2.378-383.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nilsson P, Uhlin B E. Differential decay of a polycistronic Escherichia coliis initiated by RNaseE-dependent endonucleolytic processing. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1791–1799. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nowicki B, Rhen M, Väisänen-Rhen V, Pere A, Korhonen T K. Immunofluorescence study of fimbrial phase variation in Escherichia coliKS71. J Bacteriol. 1984;160:691–695. doi: 10.1128/jb.160.2.691-695.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Olsén A, Jonsson A, Normark S. Fibronectin binding mediated by a novel class of surface organelles on Escherichia coli. Nature. 1989;338:652–655. doi: 10.1038/338652a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Olsén A, Arnqvist A, Hammar M, Sukupolvi S, Normark S. The RpoS sigma factor relieves H-NS-mediated transcriptional repression of csgA, the subunit gene of fibronectin-binding curli in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:523–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paunio M, Peabody R, Keskimäki M, Kokki M, Ruutu P, Oinonen S, Vuotari V, Siitonen A, Tast E, Leinikki P. Swimming associated outbreak of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli(EHEC) O157:H7. Epidemiol Infect. 1999;122:1–5. doi: 10.1017/s0950268898001927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pere A, Nowicki B, Saxén H, Siitonen A, Korhonen T K. Expression of P, type-1, and type-1C fimbriae of Escherichia coliin the urine of patients with acute urinary tract infection. J Infect Dis. 1987;156:567–574. doi: 10.1093/infdis/156.4.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pere A, Selander R K, Korhonen T K. Characterization of P fimbriae on O1, O7, O75, rough, and nontypable strains of Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1988;56:1288–1294. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.5.1288-1294.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perez-Casal J, Swartley J S, Scott J R. Gene encoding the major subunit of CS1 pili of human enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3594–3600. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.11.3594-3600.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pouttu R, Puustinen T, Virkola R, Hacker J, Klemm P, Korhonen T K. Amino-acid residue Ala-62 in the FimH fimbrial adhesin is critical for the adhesiveness of meningitis-associated Escherichia colito collagens. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1747–1757. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sakellaris H, Scott J R. New tools in an old trade: CS1 pilus morphogenesis. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:681–687. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sauvonnet N, Gounon P, Pugsley A P. PpdD type IV pilin of Escherichia coli K-12 can be assembled into pili in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:848–854. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.3.848-854.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sauvonnet N, Vignon G, Pugsley A P, Gounon P. Pilus formation and protein secretion by the same machinery in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 2000;19:2221–2228. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.10.2221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Selander R K, Lewin B R. Genetic diversity and structure in Escherichia colipopulations. Science. 1980;210:545–547. doi: 10.1126/science.6999623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Selander R K, Korhonen T K, Väisänen-Rhen V, Williams P H, Pattison P E, Caugant D A. Genetic relationships and clonal structure of strains of Escherichia colicausing neonatal septicemia and meningitis. Infect Immun. 1986;52:213–222. doi: 10.1128/iai.52.1.213-222.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sokurenko E V, Chesnokova V, Dykhuizen D E, Ofek I, Wu X-R, Krogfelt K A, Struve C, Schembri M A, Hasty D L. Pathogenic adaptation of Escherichia coliby natural variation of the FimH adhesin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:8922–8926. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Strom M S, Lory S. Structure function and biogenesis of the type IV pili. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1993;47:565–596. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.003025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tietze E, Brevet J, Tschäpe H, Voigt W. Cloning and preliminary characterization of the streptothricin resistance determinants of the transposons Tn 1825 and Tn 1826. J Basic Microbiol. 1988;28:129–136. doi: 10.1002/jobm.3620280116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Väisänen-Rhen V, Elo J, Väisänen E, Siitonen A, Ørskov I, Ørskov F, Svenson S B, Mäkelä P H, Korhonen T K. P-fimbriated clones among uropathogenic Escherichia colistrains. Infect Immun. 1984;43:149–155. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.1.149-155.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Virkola R, Parkkinen J, Hacker J, Korhonen T K. Sialyloligosaccharide chains of laminin as an extracellular matrix target for S fimbriae of Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4480–4484. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.10.4480-4484.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang Y, Kim K S. Effect of rpoS mutations on stress-resistance and invasion of brain microvascular endothelial cells in Escherichia coliK1. FEMS Lett. 2000;182:241–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb08902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Westerlund-Wikström B, Tanskanen J, Virkola R, Hacker J, Lindberg M, Skurnik M, Korhonen T K. Functional expression of adhesive peptides as fusions to Escherichia coliflagellin. Prot Eng. 1997;10:1319–1326. doi: 10.1093/protein/10.11.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Whittam T S. Genetic variation and evolutionary processes in natural populations of Escherichia coli. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Vol. 2. Washington D.C.: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 2708–2720. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xia Y, Gally D, Forsman-Semb K, Uhlin B E. Regulatory cross-talk between adhesin operons in Escherichia coli: inhibition of type 1 fimbriae expression by the PapB-protein. EMBO J. 2000;19:1450–1457. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.7.1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ylönen A, Rinne A, Herttuainen J, Bögwald J, Järvinen M, Kalkkinen N. Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) skin contains a novel kininogen and another cysteine proteinase inhibitor. Eur J Biochem. 1999;266:1–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]