Abstract

Cells use highly regulated transcriptional networks to control temporally regulated events. In the bacterium Caulobacter crescentus, many cellular processes are temporally regulated with respect to the cell cycle, and the genes required for these processes are expressed immediately before the products are needed. Genes encoding factors required for DNA replication, including dnaX, dnaA, dnaN, gyrB, and dnaK, are induced at the G1/S-phase transition. By analyzing mutations in the dnaX promoter, we identified a motif between the −10 and −35 regions that is required for proper timing of gene expression. This motif, named RRF (for repression of replication factors), is conserved in the promoters of other coordinately induced replication factors. Because mutations in the RRF motif result in constitutive gene expression throughout the cell cycle, this sequence is likely to be the binding site for a cell cycle-regulated transcriptional repressor. Consistent with this hypothesis, Caulobacter extracts contain an activity that binds specifically to the RRF in vitro.

The cell cycle of Caulobacter crescentus requires that the transcription of many genes be temporally regulated. In fact, the transcription of ∼20% of the genes in Caulobacter is regulated as a function of the cell cycle (6). In some cases, the elements that mediate cell cycle-regulated transcription have been characterized, most notably those that are controlled by the response regulator CtrA (11). CtrA controls approximately one-fourth of the cell cycle-regulated genes (6), but little is known about the factors that are responsible for the regulation of the remaining three-fourths of the genes. In many cases, genes that are required for a cell cycle-regulated process are induced shortly before the gene product is needed (6). This observation suggests that there are transcription factors responsible for the coordinated expression of functionally related genes.

The timing of DNA replication is tightly controlled in Caulobacter. Each cell division in Caulobacter produces two different cell types, but in each cell, DNA replication is initiated only once per cell cycle (3, 9, 10). The swarmer cell enters the cell cycle in G1 phase and initiates DNA replication at a discrete time during the swarmer-to-stalked cell transition, whereas the stalked cell immediately initiates replication and enters the cell cycle in S phase (Fig. 1). Before initiation of replication, transcription of genes encoding many replication factors is induced, suggesting that these genes are regulated by a shared repressor or activator (Fig. 1) (6, 12, 14). The promoter region has been mapped for genes that encode five replication factors: dnaN, encoding the β subunit of DNA polymerase III (12); dnaX, encoding the γ and τ subunits of DNA polymerase III (14); gyrB, encoding the β subunit of DNA gyrase (12); dnaA, encoding a replication initiation factor (15); and dnaK, encoding a chaperone required for initiation of replication (5). For each of these genes, the primary promoter has canonical −10 and −35 sequences for ς73, the major sigma factor in Caulobacter (7). dnaA, dnaX, and gyrB each have a single ς73 promoter; dnaK has a ς73 promoter and a heat shock promoter; and dnaN has a ς73 promoter, a heat shock promoter, and an additional promoter. The transcription of each of these genes is induced before DNA replication is initiated, although there is some divergence in the expression patterns (Fig. 1). Transcription from the dnaA promoter is induced first, followed by coordinated induction of dnaN, dnaX, gyrB, and dnaK. These promoters do not contain CtrA binding sites and are not directly controlled by CtrA (6), so understanding how they are coordinately induced requires identification of novel cell cycle regulatory elements.

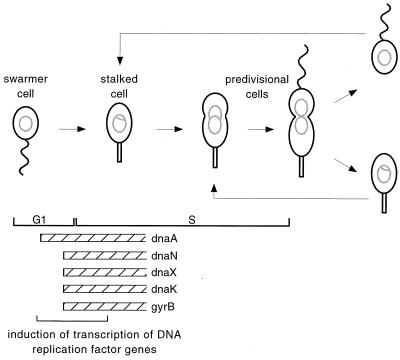

FIG. 1.

Induction of the replication genes during the G1/S-phase transition in the Caulobacter cell cycle. A swarmer cell (G1 phase) with a single flagellum (wavy line) and nonreplicating chromosome (open gray circle) differentiates into a stalked cell and initiates DNA replication (gray theta-structure). The stalked cell elongates, continues DNA replication, and forms a division plane to become a predivisional cell. The predivisional cell divides asymmetrically to generate a swarmer cell and a stalked cell. The locations of the G1- and S-phase cells are indicated by black brackets. The relative timing of induction of transcription of replication factors is shown by the hatched boxes (5, 6, 12, 14, 15).

Alignments of the promoter sequences for these five genes have suggested that there are two conserved sequence motifs, called the “8-mer” and the “13-mer” (the number of bases in the 13-mer motif varies among promoters) (12, 14), which may be binding sites for transcription factors. The 13-mer lies in the region between the −10 and −35 sequences, and two conflicting consensus sequences have been proposed for this element (12, 14). In order to characterize this regulatory element, we systematically mutagenized each position in this region of the dnaX promoter and examined the effects on the level and timing of transcription. Our results show that there is a regulatory element present between the −35 and −10 sequences in the dnaX promoter and that this element is required for cell cycle regulation of transcription. This element is required for the repression of transcription during periods of the cell cycle when the replication factor genes are not expressed, so we have named it RRF (for repression of replication factors). Furthermore, we demonstrate that Caulobacter extracts contain an activity that binds stably to the RRF of the dnaX promoter and to the analogous regions of the dnaA, dnaN, gyrB, and dnaK promoters.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and plasmids.

The wild-type Caulobacter crescentus strain used in these studies is CB15N (4). Caulobacter cultures were grown at 30°C in PYE medium (2 g of peptone, 1 g of yeast extract, 0.2 g of MgCl2, 73 mg of CaCl2 per liter) containing 1 μg of tetracycline per ml as necessary. The dnaX promoter constructs were made by PCR from pEW135 (14) by using a primer with 1 base randomized, cloning the product into pBluescript II KS+, and transforming the resulting plasmids into Escherichia coli strain DH5α. Plasmid clones were sequenced to identify mutations and subcloned in front of the lacZ gene in the plasmid pRKlac290 (2), and the resulting reporter plasmids were transformed into wild-type Caulobacter. Synchronous cultures were obtained by purifying swarmer cells in a Ludox density gradient as previously described (4).

Promoter activity assays.

Promoter activity was assayed by measuring the increase in activity of β-galactosidase in cultures growing in the log phase (13). β-Galactosidase activity was measured at a minimum of four time points during log-phase culture growth, and the rate of β-galactosidase production was determined from the increase in activity over time. At least three independent time courses were examined for each promoter mutant, and in all cases, the standard deviation was less than 5%.

Promoter activity in synchronous cultures was measured by pulse-labeling cells at different times and immunoprecipitating β-galactosidase. Cells growing in M2 minimal medium (6.1 mM Na2HPO4, 3.9 mM KH2PO4, 4.7 mM NH4Cl, 0.5 mM MgSO4, 0.2% glucose, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 10 μM FeSO4) were labeled for 2 min by addition of [35S]methionine (Amersham), the labeling was terminated, and the cells were lysed by addition of trichloroacetic acid to a final concentration of 5%. The protein was precipitated by centrifugation and resuspended in buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA, and 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate. β-Galactosidase was immunoprecipitated by incubating the resuspended protein with polyclonal anti-β-galactosidase antibody (5′→3′, Inc.) for 2 h, washing it with radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (13), incubating it with protein A-conjugated Sepharose for 1 h, and collecting it by centrifugation. The labeled β-galactosidase was quantified by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis followed by analysis on a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). To correct for sampling errors, the β-galactosidase signal was normalized with respect to the signal from an unrelated protein present at constant levels throughout the cell cycle and which cross-reacts with the anti-β-galactosidase antibody.

DNA binding assays.

DNA probes were constructed by end labeling oligonucleotides corresponding to the following sequences with T4 polynucleotide kinase (13) and annealing them to complementary oligonucleotides: complete dnaX, GTTGGGTGCGAGGCTTTTCGTGCGCCCTCCGCCCCACTACACTCCGCGCC; dnaX, TTCGTGCGCCCTCCGCCCCACTACAA; gyrB, GGCGTGCGGAATCCGCGCCGAATCCG; dnaA, TTGACCGGCCCCCTCCGCTGGCTAGT; dnaN, GCCCCGCGCGCGTCTTTCGCTAATGC; dnaK, CCGACGGGCTCGTCAACTCGCACAAG; and arb. (arbitrary sequence), TTCGTGGGAGTTAAGGTTCACTACAA. Caulobacter extracts were made by sonication or by extraction with a detergent mixture (B-PER; Pierce) and assayed for DNA-binding activity by gel mobility shift assays. Typically, a 300-ml log-phase culture of Caulobacter was harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 30 ml of buffer B (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 100 mM NaCl, 50 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol). The cells were lysed by the addition of lysozyme to a final concentration of 10 μg/ml and then sonicated until the optical density at 600 nm was reduced to less than 10% of the initial level. The insoluble material was removed by centrifugation for 30 min at 27,000 × g. Alternatively, extracts were made by extraction with B-PER detergent following the manufacturer's protocol (Pierce). The concentration of total protein in the extracts was 1 to 3 mg/ml, and 1 to 5 μl of extract was used for a 25-μl DNA-binding reaction. For gel-shift assays, extract was incubated for 2 h with 200 μM 32P-end-labeled DNA probe in buffer B containing 10 μg of bovine serum albumin per ml and 50 μg of sheared calf thymus DNA per ml as a nonspecific competitor, separated by electrophoresis on native 10% polyacrylamide gels in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer, and visualized by autoradiography (1). Nearly identical results were obtained under the range of conditions described above.

RESULTS

Mutagenesis of the dnaX promoter.

Previous mutagenic studies with the dnaX promoter have defined the −10 and −35 sequences required for transcription and have suggested that there is a negative regulatory element in this region (14). In order to define this regulatory element more precisely, we performed a thorough mutational analysis of the promoter. Each of the 14 bases in this region was individually changed to the other 3 possible bases, and transcriptional activity was measured by β-galactosidase assays. Figure 2 shows the activity of each mutant promoter relative to the wild-type promoter in unsynchronized log-phase culture. Mutations at seven positions resulted in a change in transcription of at least 50%. In all cases in which a sizable change in transcription was observed, the promoter activity increased, suggesting that these mutations disrupted a negative regulatory element. Overall, these mutations define a redundant sequence preference extending over 12 bases, starting at position −29 and continuing to position −18. There is a lesser preference at positions −17 and −16. Sequences upstream of −29 and downstream of −16 may also be required for the RRF, but since these bases are also part of the RNA polymerase binding site (14) (Fig. 2A), mutations at these positions cannot be interpreted.

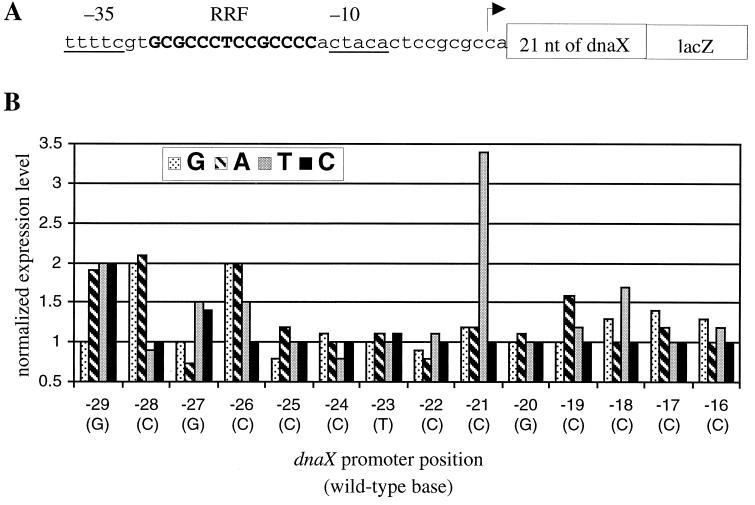

FIG. 2.

Effect of single substitutions in the dnaX promoter on gene expression. (A) Wild-type reporter construct used to assay gene expression. The promoter sequence is shown with the RRF in boldface and uppercase, the −10 and −35 regions are underlined, and the transcription start site is indicated by an arrow. The seven residues of the dnaX reading frame and the lacZ gene are represented by boxes. nt, nucleotides. (B) Relative gene expression of dnaX promoter variants determined from β-galactosidase assays. Each position of the dnaX promoter was individually mutated to the three non-wild-type bases, the promoter activity was assayed, and the data were normalized to the wild-type expression level, such that a value of 1 is equivalent to wild-type expression, values greater than 1 indicate increased promoter activity, and values less than 1 indicate decreased promoter activity. For each position, the wild-type base is shown in parentheses.

Four positions, −29, −28, −26, and −21, are crucial for regulation, because mutations at these positions result in an increase in promoter activity of twofold or more (Fig. 2). There is a strong preference for a G at −29 and a C at −26, because no other bases at these positions produce wild-type promoter activity. At −28, a pyrimidine is preferred. The greatest change in activity was observed for the C(−21)T substitution, which increased activity by 3.4-fold, but other substitutions at this position had only a mild effect. The individual mutations studied here provide a redundant sequence preference for the RRF: GYRCnnnnCnSMYM (Y = C or T; R = A or G; S = G or C; M = A or C; and n = any base).

Cell-cycle regulation of a mutant promoter.

A priori, mutations in the RRF could increase the observed promoter activity by increasing transcription throughout the cell cycle while retaining the normal regulatory pattern, by increasing the peak level of transcription, or by relieving repression so that peak-level transcription occurs throughout the cell cycle. To determine how mutations in the RRF affect the cell cycle regulation of the dnaX promoter, we isolated swarmer cells from Caulobacter bearing a lacZ reporter driven by either the wild-type dnaX promoter or the C(−21)T variant. We then allowed the cells to pass synchronously through the cell cycle and assessed transcription at different times by using a pulse-label immunoprecipitation assay (Fig. 3). The major effect of the C(−21)T mutation is loss of repression of the dnaX promoter in the swarmer and late predivisional cells. Whereas the wild-type promoter is induced 10-fold during the swarmer-to-stalked cell transition, expression from the C(−21)T variant changes by only 1.5-fold and exhibits expression levels throughout the cell cycle that are near the wild-type maximum. In fact, the minimal level of expression from the C(−21)T variant is 7.5-fold higher than that in the wild type. There is also a small change in the peak expression from the C(−21)T variant: maximal expression is approximately 15% higher than in the wild type and occurs earlier in the swarmer-to-stalked cell transition. It is possible that this increase in peak expression level is due to a positive regulatory factor that prefers the C(−21)T variant. However, the increased expression levels in the swarmer and predivisional cells are more significant than the small increase during the swarmer-to-stalked cell transition. Therefore, the increased amount of gene expression in unsynchronized cultures bearing the C(−21)T variant appears to be due primarily to a loss of cell cycle-regulated repression.

FIG. 3.

Expression from the wild-type dnaX promoter and the C(−21)T variant as a function of the cell cycle. Synchronized populations of Caulobacter were assayed for promoter activity at different points in the cell cycle by pulse-labeling and immunoprecipitation of β-galactosidase. The position of the population with respect to the cell cycle is indicated by the schematic diagram. Expression is given in arbitrary (arb.) units.

DNA-binding activity for the RRF.

The most straightforward explanation for the activity of the RRF is that a repressor binds to this sequence and inhibits transcription. Mutations that disrupt this binding site would then decrease repression and lead to a higher level of transcription. To investigate whether such a repressor exists, we assayed Caulobacter extracts for a DNA-binding activity specific for the dnaX RRF. Binding site probes were constructed that correspond to the dnaX RRF (positions −50 to −1) or to the RRF flanked by shorter DNA sequences to control for binding of RNA polymerase ς factors to the −35 and −10 regions. We found that Caulobacter extracts contain an activity that binds to the dnaX promoter RRF, but does not bind to a similar DNA probe in which the RRF has been replaced by an arbitrary sequence (Fig. 4). A dnaX promoter probe containing the C(−21)T mutation was also shifted (data not shown), indicating that this sequence retains enough of the protein-DNA contacts to bind under these assay conditions.

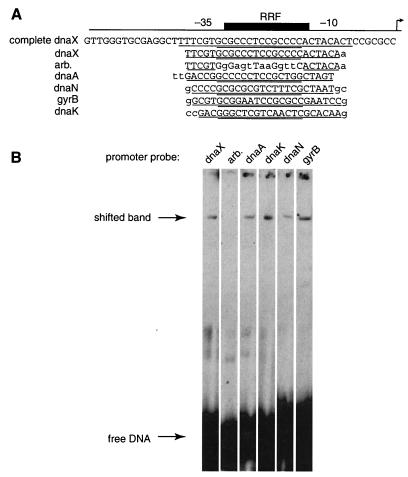

FIG. 4.

Caulobacter cell extracts contain RRF-binding activity. (A) Sequence of DNA probes used for gel mobility shift assays. The promoter region is shown schematically with the −10 and −35 regions labeled, the RRF indicated by a black box, and the transcription start site indicated by an arrow. The sequence of each probe is shown with the RRF double underlined, the −10 and −35 regions single underlined, and bases different from the wild-type promoter sequence in lowercase. (B) Gel mobility shift assays of DNA probes corresponding to replication gene promoters with Caulobacter cell extract. The positions of free probe DNA and the shifted band are indicated by arrows.

We tested these extracts for binding activity to the comparable region of the dnaA, dnaN, dnaK, and gyrB promoters and found that these probes are also shifted (Fig. 4). Since the different promoter probes are shifted to the same mobility, it is likely that they are bound by the same protein or protein complex. These results are consistent with the model that a transcriptional repressor binds to this region in all of the promoters.

Identification of RRFs in other promoters.

Based on the redundant RRF sequence from the dnaX promoter, we identified putative RRF sequences in the promoters of dnaA, dnaN, dnaK, and gyrB (Fig. 5). Although these promoters are induced in a similar fashion and are all proposed to have ς73 binding sites, none of the −10 or −35 sequences is the same, and none exactly matches the ς73 consensus sequence (8). Similarly, none of the RRF sequences is an exact match with the preferences defined for the dnaX promoter. It is possible that bases in the −10 or −35 regions also influence the RRF, so that each RRF sequence is optimized to the surrounding DNA. Another possible reason for variation in the RRF sequences is that changes in the RRF among the promoters alter the affinity of the repressor and thereby account for the differences in cell cycle regulation observed for the different promoters. For instance, the dnaA RRF is the most divergent, so it would be predicted to bind the repressor with altered affinity. In fact, the dnaA gene is induced earlier in the cell cycle than the other replication genes, consistent with weaker binding of the repressor.

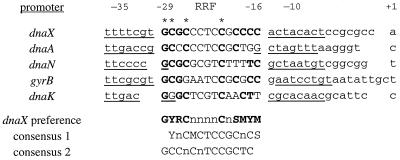

FIG. 5.

Alignment of RRF sequences from replication factor gene promoters based on the dnaX preference. The −10 and −35 sequences are underlined, and the RRF is shown in uppercase. Bases consistent with the dnaX preference are in boldface, and the four positions at which mutations can cause at least a twofold increase in gene expression are indicated by asterisks. The dnaX promoter preference is shown below as well as consensus sequence 1 (14) and consensus sequence 2 (12), based on promoter alignments. In all cases, Y = C or T, R = A or G, S = G or C, M = A or C, and n = any base.

DISCUSSION

Control of the cell cycle in Caulobacter requires coordinated expression of functionally related groups of genes. The genes for DNA replication factors are coordinately induced, but the mechanism of this regulation is not known. To gain a better understanding of how these genes are controlled, we performed a thorough mutational analysis of the region between the −35 and −10 sequences of the dnaX promoter. This study identified a promoter element, the RRF, which is required for cell cycle-regulated expression from the dnaX promoter and is present in all of the coordinately regulated genes of replication factors. Our results show that the RRF is a negative regulatory element essential for the correct timing of gene expression and suggest that it is the binding site for a repressor protein.

The analysis of single-base substitutions in the dnaX promoter has defined the RRF preference as GYRCnnnnCnSMYM. Three mutations in this region consisting of multiple substitutions (Table 1) have previously been studied and can now be more precisely interpreted (14). A double substitution of C(−26)A/C(−25)T resulted in 1.4-fold-higher transcription, but because a C(−26)A substitution results in a 2-fold increase in the level of transcription, and a C(−25)T substitution has no effect, the effect of C(−26)A/C(−25)T is likely to be due solely to the change at position −26 (Table 1). In the case of a double substitution of C(−19)A/C(−18)T, the result represents the additive effects of the individual mutations. The double mutation resulted in 3.6-fold-higher transcription, a single C(−19)A substitution results in 1.6-fold-higher transcription, and a single C(−18)T substitution results in 1.7-fold-higher transcription. Finally, a mutation that inserts two G's in place of T at −23 was found to decrease transcription 5.3-fold, but single substitutions at position −23 do not change promoter activity. Therefore, it is likely that the effect observed for the T(−23)GG mutation is due to the change in spacing between the −35 and −10 sequences, decreasing RNA polymerase binding and transcription initiation rather than increasing repressor activity.

TABLE 1.

Relative activity of doubly and singly substituted variants of the dnaX promoter

| dnaX promoter variant | RRF sequencea | Fold induction (repression) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | GCGCCCTCCGCCCC | 1.0 | |

| C(−26)A/C(−25)T | GCGCATTCCGCCCC | 1.4 | 14 |

| C(−26)A | GCGCACTCCGCCCC | 2.0 | This study |

| C(−25)T | GCGCCTTCCGCCCC | 1.0 | This study |

| C(−19)A/C(−18)T | GCGCCCTCCGATCC | 3.6 | 14 |

| C(−19)A | GCGCCCTCCGACCC | 1.6 | This study |

| C(−18)T | GCGCCCTCCGCTCC | 1.7 | This study |

| T(−23)GG | GCGCCCGGCCGCCCC | (5.3) | 14 |

| T(−23)G | GCGCCCGCCGCCCC | 1.0 | This study |

Substitutions are given in boldface.

Previous studies defined a regulatory element in the replication factor gene promoters by aligning the promoter regions and looking for a consensus sequence. However, two different alignments produced different but overlapping consensus sequences: GCCnCTCCGCTC (12) and YnCMCTCCGCnCS (14). Although the bases we identified as comprising the RRF in the dnaX promoter overlap the previously described consensus sequences, there is not complete agreement between the bases that are important for dnaX regulation and those that are highly conserved with other promoters in these previous alignments (Fig. 5). For example, T at −23 and G at −20 are highly conserved in both alignments, but mutations at these positions do not affect the transcription from the dnaX promoter. Likewise, G at −29 is sensitive to substitution, but is not part of the first alignment consensus, and C at −26 is also sensitive to substitution, but is not found in the second alignment consensus. The revised promoter alignment presented in Fig. 5 is not as conserved as the previously published consensus sequences, but since it is based on mutational data, it is likely to be more functionally relevant than those based wholly or largely on manual sequence alignment. This consensus sequence has been thoroughly tested and refined for the dnaX promoter. Further analyses of the dnaA, dnaN, dnaK, and gyrB promoters and characterization of the RRF-binding activity in Caulobacter extracts will reveal whether the RRF sequence preference in the dnaX promoter is unique or generally conserved.

It is not surprising that the other replication factor RRFs differ from the dnaX RRF preference, because even in the context of the dnaX promoter, the dnaX RRF is not the optimal repressor binding site. Some mutations resulted in lower promoter activity, by as much as 30%, consistent with increased binding of a repressor to the RRF. There may be physiological reasons why an optimal repressor binding site is not used. For example, if the RRF repressor is bound too tightly, it could not be removed when the gene needs to be expressed.

Caulobacter extracts contain an activity that binds to the RRF, and although the repressor has not yet been identified, the dnaX promoter mutants predict some characteristics of the repressor-DNA interaction. The bases that are important for the RRF, −29 to −26 and −21 to −18, are predicted to be on the same face of B-form DNA, so a repressor (or repressor complex) could bind without wrapping around the DNA helix. Because G(−29) and C(−26) cannot be functionally replaced by any other bases, it is likely that these residues are directly recognized by the repressor. The discrimination against T at position −21 suggests an interaction between a protein and the major groove of the RRF at this position, since T has a bulky methyl group protruding into the major groove, which can cause steric hindrance.

Although a probe with the C(−21)T mutation is shifted by cell extracts, this mutation clearly affects promoter activity. It is possible that the C(−21)T mutant binds to the repressor with lower affinity than the wild-type sequence, such that in vivo the wild-type promoter is bound and the C(−21)T promoter is not. Such a difference in affinity would not be detected in our assays if the concentration of repressor is above the dissociation constant for the C(−21)T promoter. Alternatively, it is possible that the C(−21)T mutant binds to the repressor with comparable affinity to the wild type, but in a conformation that does not result in transcriptional repression. Identification of the repressor that binds to the RRF and characterization of its interactions with wild-type and mutant replication factor promoters are essential to distinguish between these possibilities and to understand how the RRF mediates its effects on transcription.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Sarah Ades and members of the Shapiro laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript.

K. C. Keiler is a DOE-EnergyBiosciences Research Fellow of the Life Sciences Research Foundation. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM51426.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ades S E, Sauer R T. Differential DNA-binding specificity of the engrailed homeodomain: the role of residue 50. Biochemistry. 1994;33:9187–9194. doi: 10.1021/bi00197a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alley M R K, Gomes S L, Alexander W, Shapiro L. Genetic analysis of a temporally transcribed chemotaxis gene cluster in Caulobacter crescentus. Genetics. 1991;129:333–342. doi: 10.1093/genetics/129.2.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Degnan S T, Newton A. Chromosome replication during development in Caulobacter crescentus. J Mol Biol. 1972;64:671–680. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(72)90090-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evinger M, Agabian N. Envelope-associated nucleoid from Caulobacter crescentus stalked and swarmer cells. J Bacteriol. 1977;132:294–301. doi: 10.1128/jb.132.1.294-301.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomes S L, Gober J W, Shapiro L. Expression of Caulobacter heat shock gene dnaK is developmentally controlled during growth at normal temperatures. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3051–3059. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.6.3051-3059.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laub M T, McAdams H H, Feldblyum T, Fraser C, Shapiro L. Global analysis of the genetic network controlling a bacterial cell cycle. Science. 2000;290:2144–2148. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5499.2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malakooti J, Ely B. Principal sigma subunit of the Caulobacter crescentus RNA polymerase. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6854–6860. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.23.6854-6860.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malakooti J, Wang S P, Ely B. A consensus promoter sequence for Caulobacter crescentus genes involved in biosynthetic and housekeeping functions. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4372–4376. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.15.4372-4376.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marczynski G, Dingwall A, Shapiro L. Plasmid and chromosomal DNA replication and partitioning during the Caulobacter crescentus cell cycle. J Mol Biol. 1990;212:709–722. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90232-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marczynski G T. Chromosome methylation and measurement of faithful, once and only once per cell cycle chromosome replication in Caulobacter crescentus. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1984–1993. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.7.1984-1993.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quon K C, Marczynski G T, Shapiro L. Cell cycle control by an essential bacterial two-component signal transduction protein. Cell. 1996;84:83–93. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80995-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roberts R C, Shapiro L. Transcription of genes encoding DNA replication proteins is coincident with cell cycle control of DNA replication in Caulobacter crescentus. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2319–2330. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.7.2319-2330.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winzeler E, Shapiro L. A novel promoter motif for Caulobacter cell cycle-controlled DNA replication genes. J Mol Biol. 1996;264:412–425. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zweiger G, Shapiro L. Expression of Caulobacter dnaA as a function of the cell cycle. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:401–408. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.2.401-408.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]