Abstract

The US physician workforce does not reflect the racial and ethnic makeup of the country’s population, despite efforts to promote diversity. Becoming a physician requires significant time and financial investment, and populations that are underrepresented in medicine have also been excluded from building wealth. Understanding the differential burden of debt by race and ethnicity may inform strategies to improve workforce diversity. We used 2014–19 data on postgraduate resident trainees from the Association of American Medical colleges to examine the association between race and ethnicity and debt independent of other demographics and residency characteristics. Black trainees were significantly more likely to have every type of debt than the overall sample and all other racial and ethnic groups (96 percent of Black trainees had any debt versus 83 percent overall; 60 percent had premedical education loans versus 35 percent overall, and 50 percent had consumer debt versus 25 percent overall). American Indian/Alaska Native, Hispanic, and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander trainees were more likely to have debt compared with White and Asian trainees. Overall, debt prevalence decreased over time and varied by specialty; however, for Black trainees, debt decreased minimally over time and was stable across specialties. Scholarships, debt relief, and financial guidance should be explored to improve diversity and inclusion in medicine across specialties.

The US physician workforce does not reflect the racial and ethnic diversity of the national population,1-3 despite the benefits attributed to a more diverse workforce.4-10 American Indian/Alaska Native, Black, Hispanic, and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander populations are broadly underrepresented in medicine, and they are underrepresented to a greater extent in some specialties.11-15 The reasons why these populations are underrepresented are multifactorial and, collectively, a result of historical and ongoing socioeconomic inequities as well as exclusion in academic medicine and other educational opportunities.4,16,17 As a result of structural forms of racism, populations that are underrepresented in medicine have also had more limited access to financial resources, fewer opportunities to build wealth, and lower incomes at the same level of educational attainment.11,13,15 Black Americans, in particular, have the highest rates of debt for educational loans.18,19 Understanding the differences in debt burden by race and ethnicity among medical trainees may help guide strategies to increase diversity and inclusion within the physician workforce.

The time and financial investment necessary to become a physician in the US is substantial. Debt influences physicians’ experiences and their choices throughout the pipeline from medical school to independent practice. Debt is associated with higher rates of burnout and stress among trainees,20-26 influences specialty choice,27-29 and is also associated with lower productivity30 and greater attrition.31 Limited data demonstrate racial and ethnic disparities in debt among medical students,32,33 yet these trends have not been examined in the context of the overall decrease in debt prevalence among medical school graduates over time or across specialties among postgraduate residents.33,34 Understanding the independent predictors of debt burden among trainees may be informative for various stakeholders with an interest in increasing diversity in the physician workforce. Among these stakeholders are medical schools, which may wish to provide financial assistance to alleviate debt; residency programs, which could provide targeted financial guidance and assistance; universities and academic institutions, which could provide additional support for indebted junior faculty; and policy makers, who could expand scholarship or loan forgiveness programs.

Accordingly, the goal of our study was to characterize the association between debt and the race and ethnicity of medical resident trainees independent of other trainee sociodemographic and residency program characteristics. Secondary objectives were to examine differences by race and ethnicity across three types of debt—loans for premedical education, loans for medical education, and noneducational consumer debt—as well as to examine differences by race and ethnicity in the amount of debt held. We hypothesized that race and ethnicity would be an independent predictor of debt and that all types of debt would be more common among trainees from populations underrepresented in medicine.

Study Data And Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study of active postgraduate residents who trained in the US during the period 2014–19 and who completed the Medical School Graduation Questionnaire on graduating from medical school. The Medical School Graduation Questionnaire is administered by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) to all medical students who graduate from a medical school in the US with a doctor of medicine (MD) degree. Students who do not graduate do not complete the questionnaire.We chose to analyze data on resident trainees so that we could incorporate information on specialty and program location into our models. Data were provided by the AAMC and included all programs accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Postgraduate trainee information came from the AAMC’s Graduate Medical Education Track Resident Survey, which had a 94.1–95.0 percent response rate between 2014 and 2019, according to email correspondence with the AAMC. Response rates for the past four years are available online as part of executive summaries of the Resident Survey data.35

Debt data were obtained from the Medical School Graduation Questionnaire. Of the 161,995 US-trained allopathic postgraduate residents active during 2014–19, 131,439 (81.1 percent) completed this questionnaire at the time of graduation from medical school. We excluded 10,573 (8.0 percent) of these trainees because they did not answer any questions about debt (see data in online appendix exhibit A4).36 Our study was exempted from review by the Yale University Institutional Review Board and followed STROBE reporting guidelines.37

MEASURES OF DEBT BURDEN

We assessed three subtypes of debt: loans for premedical education, loans for medical education, and noneducational consumer debt. The survey questions used to assess these three types of debt changed minimally, but not substantively, over the years (appendix exhibits A1 and A2).36 Questions about debt were structured with an initial “yes or no” question asking about the presence of the particular debt. For educational loans, loan service commitments were explicitly included. For noneducational consumer debt, trainees who completed the questionnaire before 2015 were told to exclude debt from home mortgages, whereas from 2015 on, mortgages were included. Because mortgage debt may be different from other consumer debt (for example, credit card debt), we focused our analysis on consumer debt without mortgages and included consumer debt from later years in the appendix.36 All yes-or-no debt questions were followed with a fill-in-the-blank question that asked trainees to list the principal amount borrowed for that type of debt (appendix exhibit A2).36 We defined having any debt as a “yes” response to any of the yes-or-no questions.

DEMOGRAPHIC VARIABLES

Race and ethnicity were self-designated by trainees. Options were coded on the basis of recommendations by the National Academy of Medicine:38 American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Hispanic or Latino, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic White, and some other race (“other”). Trainees could select multiple race and ethnicity categories, and we grouped these trainees into one of two categories: “multiracial, Hispanic” and “multiracial, non-Hispanic.” The multiracial, Hispanic category includes those who self-designated multiple races and ethnicities, with at least one being Hispanic. The multiracial, non-Hispanic category includes those who self-designated multiple races and ethnicities, none of which were Hispanic. Finally, trainees could self-identify as “other.”

Gender, age at graduation, and the specialty and location of the trainee’s residency program were provided by the AAMC. We created six categories for specialty: surgery, internal medicine, pediatrics, family medicine, emergency medicine, and other. We grouped all surgical specialties into one “surgery” category, which is made up of postgraduate residents in general, colon and rectal, orthopedic, vascular, thoracic, and plastic surgery, as well as neurosurgery, otolaryngology, ophthalmology, and urology. These six categories account for the five most common specialties, comprising 65.6 percent of all postgraduate residents in our sample, and one category for all other specialties. Residency program regions were categorized as central, northeast, south, and west. We categorized graduation year into three relatively even periods: 2013 or earlier, 2014–16, and 2017 or later.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

We calculated descriptive statistics for trainee demographics, residency program specialty and location, and prevalence and amount of each type of debt. To compare the prevalence of all types of debt across race and ethnicity, we used chi-square tests. Next, we used logistic regression models to determine the odds of having any debt and each type of debt by race and ethnicity. We used “White” as the referent category because non-Hispanic White trainees are represented fairly adequately relative to their representation in the US population. Our multivariable models included demographic variables, including trainee gender, age, and graduation year, as well as residency program variables (specialty and region). After identifying independent predictors of debt in our multivariable models, we conducted analysis-of-variance tests to examine differences in these associations by race and ethnicity, as well as chi-square tests stratified by race. Among trainees reporting debt, we compared the median amount of each type of debt across race and ethnicity, using Kruskal-Wallis tests. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. We performed all analyses using Stata, version 14.2.

LIMITATIONS

Our analysis had limitations, including that our sample did not capture medical students who did not go on to residency. Medical students who do not graduate do not complete the Medical School Graduation Questionnaire, so these data were not available on people who withdrew from medical school; however, more than 99 percent of allopathic graduates ultimately enter graduate medical education.39 This analysis contained a high proportion of trainees across specialties over six years and is thus a rich source of insight on allopathic graduates. Further, loan forgiveness programs in the US are particularly applicable to this group, as well as to doctor of osteopathic medicine (DO) graduates. Our recommendations for increasing diversity and inclusion are relevant to MD- and DO-granting institutions in the US.

Also, our sample had differential nonresponse rates by race and ethnicity. Because we expected trainees with debt to be less likely to respond, our estimates of debt prevalence and inequities of debt burden were likely conservative. Small numbers of American Indian/Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander trainees limited our statistical power to draw conclusions about trainees from these groups, but our use of six years of data provided enough power for us to disaggregate populations underrepresented in medicine. However, our analysis did not disaggregate trainees within racial and ethnic groups. This may be of particular importance for trainees who identify as Asian, as Asian Americans have the largest within-group income inequality in the US,40 which is also reflected in medical students’ family incomes.41

Finally, we did not include family income or the private/public status of the trainee’s medical school, which were not available in our data set. Future work examining differences in debt by family income and between private and public schools would be valuable.

Study Results

Of the 131,439 postgraduate resident trainees who completed the Medical School Graduation Questionnaire when they graduated from medical school, we excluded 10,573 who did not answer questions on debt. Survey nonresponse rates were lowest among White trainees, as were debt question nonresponse rates (appendix exhibits A3 and A4).36 Our final sample of 120,866 trainees represented 74.5 percent of postgraduate residents active at any point during 2014–19 who graduated from MD-granting US medical schools. Of respondents, 74,010 were White (61.2 percent); 24,361 were Asian (20.2 percent); 6,253 were Black (5.2 percent); 5,151 were Hispanic (4.3 percent); 167 were American Indian/Alaska Native (0.1 percent); 61 were Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (0.1 percent); 4,168 were multiracial, Hispanic (3.4 percent); 4,585 were multiracial, non-Hispanic (3.8 percent); and 1,877 self-identified as other (1.6 percent). The majority (61,985, or 51.3 percent) were male. Among respondents, 24,848 were training in surgery specialties (20.6 percent), 22,292 in internal medicine (18.4 percent), 12,153 in pediatrics (10.1 percent); 10,227 in family medicine (8.5 percent), and 9,767 in emergency medicine (8.1 percent). Exhibit 1 shows additional cohort characteristics.

EXHIBIT 1.

Characteristics of US postgraduate medical resident trainees in the study cohort active during 2014–19

| Characteristics | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 120,866 | 100.0 |

| Race and ethnicity | ||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 167 | 0.1 |

| Asian | 24,361 | 20.2 |

| Black | 6,253 | 5.2 |

| Hispanic | 5,151 | 4.3 |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 61 | 0.1 |

| White | 74,010 | 61.2 |

| Multiracial, Hispanic | 4,168 | 3.4 |

| Multiracial, non-Hispanic | 4,585 | 3.8 |

| Other | 1,877 | 1.6 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 58,876 | 48.7 |

| Male | 61,985 | 51.3 |

| Age at graduation, years | ||

| Under 24 | 459 | 0.4 |

| 24–26 | 51,715 | 42.8 |

| 27–29 | 48,429 | 40.1 |

| 30–32 | 13,605 | 11.3 |

| 33 and older | 6,602 | 5.5 |

| Specialty | ||

| Surgerya | 24,848 | 20.6 |

| Internal medicine | 22,292 | 18.4 |

| Pediatrics | 12,153 | 10.1 |

| Family medicine | 10,227 | 8.5 |

| Emergency medicine | 9,767 | 8.1 |

| Other | 41,579 | 34.4 |

| Residency program region | ||

| Central | 27,523 | 22.8 |

| Northeast | 35,831 | 29.6 |

| South | 33,901 | 28.0 |

| West | 23,611 | 19.5 |

| Graduation year | ||

| 2013 or earlier | 37,265 | 30.8 |

| 2014–16 | 40,061 | 33.1 |

| 2017 or later | 43,540 | 36.0 |

source Authors’ analysis of trainee data from the Medical School Graduation Questionnaire and the Graduate Medical Education Track Resident Survey, both administered by the Association of American Medical Colleges.

Includes residents active in all surgical specialties, including general, colon and rectal, orthopedic, vascular, thoracic, and plastic surgery, as well as neurosurgery, otolaryngology, ophthalmology, and urology.

DEBT PREVALENCE

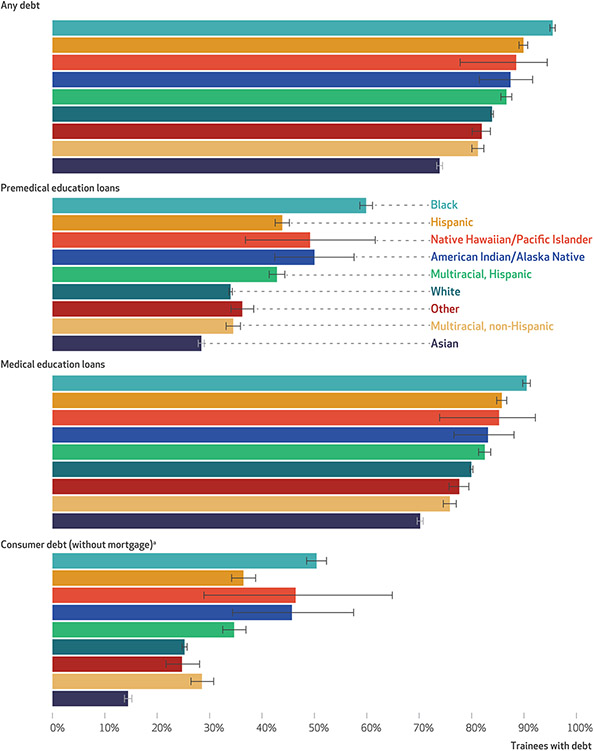

Debt was reported by 82.7 percent of trainees (95% confidence interval: 82.5, 82.9). Debt from loans for medical education was most common (78.7 percent; 95% CI: 78.4, 78.9), whereas fewer trainees had loans from premedical education (35.0 percent; 95% CI: 34.8, 35.3) or consumer debt (25.3 percent; 95% CI: 25.0, 25.7) (data not shown). However, all types of debt were significantly more common among trainees from populations underrepresented in medicine compared with White and Asian trainees (p < 0.001). Black trainees were consistently most likely to have debt, including 95.5 percent with any debt (95% CI: 94.9, 96.0), and a majority of Black trainees had debt from premedical education loans (59.9 percent; 95% CI: 58.7, 61.1) and consumer debt (50.4 percent; 95% CI: 48.5, 52.3). Exhibit 2 shows that patterns of debt prevalence by race and ethnicity were consistent across debt types, with Black trainees consistently most likely to have debt, followed by Hispanic, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native, White, and Asian trainees. The appendix also includes consumer debt with mortgages (appendix exhibit A5).36

EXHIBIT 2. Percent of US postgraduate medical resident trainees with debt, by type of debt and by race and ethnicity, 2014–19.

source Authors’ analysis of trainee data from the Medical School Graduation Questionnaire and the Graduate Medical Education Track Resident Survey, both administered by the Association of American Medical Colleges. notes Across all debt types, debt prevalence differed by race and ethnicity (p < 0.001). Appendix exhibit A5 shows prevalence of consumer debt, including mortgages (see note 36 in text). “Question on noneducational consumer debt not including mortgage was asked of those who completed the Medical School Graduation Questionnaire before 2015 (42 percent of the sample).

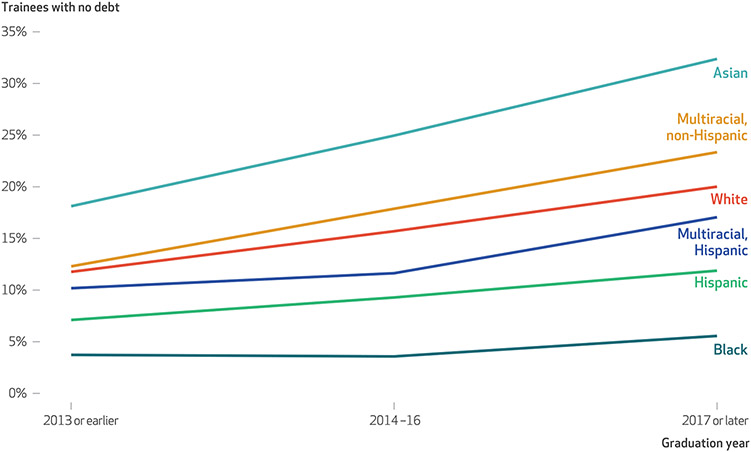

Adjusting for other demographic variables and residency program characteristics made little difference in the odds of debt by race and ethnicity (exhibit 3). In all models, Black trainees had the highest odds of having debt, and Asian trainees had the lowest. More recent cohorts of graduates were less likely to have debt, but this varied by race and ethnicity (p < 0.001). When we stratified by race, debt prevalence decreased over time, consistent with our adjusted models; however, declines in debt prevalence by graduation year were significantly greater for White and Asian residents compared with trainees from populations underrepresented in medicine. Exhibit 4 considers the inverse and shows trainees with no debt by graduation year stratified by race according to the groups for which we had an adequate sample: Asian, Black, Hispanic, multiracial (both Hispanic and non-Hispanic), and White trainees. This demonstrates that although the percentage of debt-free residents increased over time across race and ethnicity, the rate of increase was significantly higher for Asian and White trainees compared with trainees from populations underrepresented in medicine. We also identified differences in debt prevalence by specialty, with family medicine residents the most likely to have debt (89.2 percent; 95% CI: 88.5, 89.7) and internal medicine residents the least likely (78.5 percent; 95% CI: 78.0, 79.0) (data not shown).Yet these differences differed by race and ethnicity (p < 0.001). Specialty was not associated with debt for Black trainees; appendix exhibit A6 shows the percentage of trainees without debt by specialty, stratified by race and ethnicity.36

EXHIBIT 3.

Association between debt prevalence and characteristics of US postgraduate medical resident trainees active during 2014–19

| Characteristics | Model 1a |

Model 2b |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted odds ratio (N = 120,663) |

95% CI | Adjusted odds ratio (N = 120,573) |

95% CI | Adjusted odds ratio (N = 120,573) |

95% CI | |

| Race and ethnicity (ref: White) | ||||||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1.32 | 0.83, 2.08 | 1.24 | 0.78, 2.0 | 1.17 | 0.73, 1.85 |

| Asian | 0.55 | 0.53, 0.57 | 0.58 | 0.56, 0.60 | 0.62 | 0.60, 0.64 |

| Black | 4.16 | 3.70, 4.71 | 4.19 | 3.71, 4.75 | 4.27 | 3.77, 4.83 |

| Hispanic | 1.71 | 1.56, 1.88 | 1.82 | 1.66, 2.0 | 1.87 | 1.70, 2.06 |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 1.46 | 0.66, 3.21 | 1.39 | 0.63, 3.07 | 1.39 | 0.63, 3.07 |

| Multiracial, Hispanic | 1.25 | 1.14, 1.37 | 1.25 | 1.14, 1.37 | 1.27 | 1.26, 1.39 |

| Multiracial, non-Hispanic | 0.83 | 0.77, 0.89 | 0.85 | 0.79, 0.92 | 0.87 | 0.80, 0.94 |

| Other | 0.87 | 0.77, 0.98 | 0.92 | 0.81, 1.03 | 0.96 | 0.85, 1.09 |

| Gender (ref: female) | ||||||

| Male | —c | —c | 1.03 | 1.0, 1.06 | 1.04 | 1.01, 1.08 |

| Age at graduation, years (ref: under 24) | ||||||

| 24–26 | —c | —c | 2.18 | 1.79, 2.66 | 2.25 | 1.84, 2.74 |

| 27–29 | —c | —c | 2.74 | 2.25, 3.34 | 2.84 | 2.33, 3.47 |

| 30–32 | —c | —c | 2.87 | 2.34, 3.51 | 2.98 | 2.43, 3.64 |

| 33+ | —c | —c | 4.45 | 3.60, 5.50 | 4.49 | 3.63, 5.56 |

| Specialty (ref: family medicine) | ||||||

| Surgery | —c | —c | —d | —d | 0.62 | 0.58, 0.67 |

| Internal medicine | —c | —c | —d | —d | 0.52 | 0.49, 0.56 |

| Pediatrics | —c | —c | —d | —d | 0.69 | 0.63, 0.74 |

| Emergency medicine | —c | —c | —d | —d | 0.78 | 0.72, 0.85 |

| Other | —c | —c | —d | —d | 0.60 | 0.56, 0.64 |

| Residency program region (ref: central) | ||||||

| Northeast | —c | —c | —d | —d | 0.74 | 0.71, 0.77 |

| South | —c | —c | —d | —d | 0.83 | 0.80, 0.87 |

| West | —c | —c | —d | —d | 0.80 | 0.76, 0.84 |

| Graduation year (ref: 2013 or earlier) | ||||||

| 2014–16 | —c | —c | 0.70 | 0.67, 0.73 | 0.69 | 0.67, 0.72 |

| 2017 or later | —c | —c | 0.50 | 0.48, 0.52 | 0.50 | 0.48, 0.52 |

source Authors’ analysis of trainee data from the Medical School Graduation Questionnaire and the Graduate Medical Education Track Resident Survey, both administered by the Association of American Medical Colleges. notes The results are odds ratios of having debt. Reference groups (value = 1.00) are in parentheses.

Model 1 adjusted for demographic characteristics (gender, age at graduation, and graduation year).

Model 2 adjusted for demographic and residency program characteristics (gender, age at graduation, graduation year, region, and specialty).

Not applicable.

Not adjusted for in the indicated model.

EXHIBIT 4. Percent of US postgraduate medical resident trainees active during 2014–19 with no debt, by graduation year, stratified by race and ethnicity.

source Authors’ analysis of trainee data from the Medical School Graduation Questionnaire and the Graduate Medical Education Track Resident Survey, both administered by the Association of American Medical Colleges. note Differences in debt prevalence over time differed by race and ethnicity (p < 0.001).

Our fully adjusted models demonstrated significantly higher odds of all types of debt for trainees from populations underrepresented in medicine. Black, Hispanic, and multiracial, Hispanic trainees consistently had significantly higher odds of having every type of debt compared with White and Asian trainees. American Indian/Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander trainees also reported every type of debt at higher rates than White trainees, but these differences were not consistently statistically significant (appendix exhibit A7).36

AMOUNT OF DEBT

PREMEDICAL EDUCATION LOANS:

Among respondents reporting debt from premedical education loans, the median amount of principal borrowed was $20,000 (interquartile range: $12,000–$45,000) (data not shown). This differed across race and ethnicity: Black trainees and trainees self-designating as other reported the highest median amount ($25,000 [IQR: 12,000–50,000] and $25,000 [IQR: 13,000–50,000], respectively), whereas American Indian/Alaska Native trainees reported the lowest ($17,000; IQR: 10,000–32,500; p < 0.001) (appendix exhibit A8).36

MEDICAL EDUCATION LOANS:

Among those reporting debt from medical education loans, the median amount of principal borrowed was $175,000 (IQR: 118,000–225,000) (data not shown). This differed across race and ethnicity: Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander trainees reported the highest median amount borrowed ($200,000; IQR: 130,000–270,000), and Asian trainees and American Indian/Alaska Native trainees reported the lowest ($160,000 [IQR: 88,000–200,000] and $160,000 [IQR: 83,000–200,000], respectively; p < 0.001) (appendix exhibit A8).36

NONEDUCATIONAL CONSUMER DEBT:

Among those reporting noneducational consumer debt, not including mortgages, the median amount was $10,000 (IQR: 4,000–15,000) (data not shown). This differed across race and ethnicity, and Asian trainees reported the least consumer debt, not including mortgages ($7,000; IQR: 3,000–15,000; p < 0.001) (appendix exhibit A8).36

Discussion

Using data on US postgraduate medical resident trainees who were active during the period 2014–19, we identified racial and ethnic disparities in debt that are reflective of racial wealth gaps in the United States—one consequence of structural racism.11-14 All types of debt were significantly more common for trainees from populations underrepresented in medicine. Black trainees, in particular, were consistently most likely to have debt. Moreover, rates of debt from loans for premedical education or consumer debt were twice as high among Black trainees compared with the group overall. Among trainees with each type of debt, the median amount differed relatively little across racial and ethnic groups. Thus, the effects of debt on the workforce are clearest at the population level. Specifically, debt may undermine diversity and inclusion among medical trainees because far more trainees from populations underrepresented in medicine are exposed to financial stress than trainees who are not from those populations. Racial disparities in educational debt are an important contributing factor to racial wealth gaps,18 and debt accrued during medical training perpetuates these gaps in the US, which exist even for high income earners.

High rates of debt may contribute to higher attrition among trainees and faculty members from populations underrepresented in medicine.31,42,43 Debt is a source of stress,20 which compounds other sources of stress more common among such trainees and faculty members.16 Trainees and physicians from populations underrepresented in medicine are more likely to report microaggressions and social isolation,44,45 as well as mistreatment such as public humiliation.46 Further, they experience bias in performance evaluations, funding, awards, and promotions.31,47-51 Thus, addressing debt may reduce one important source of stress for trainees and physicians from populations underrepresented in medicine and contribute to increasing both diversity and inclusion for physicians from these populations.

Differences in debt by specialty suggest that financial burdens may indeed shape the racial and socioeconomic demographics of some specialties, and future work could test this directly. Interestingly, family medicine residents were the most likely to have debt, whereas internal medicine residents were the least likely. Prior work has demonstrated that internal medicine residents with debt are more likely to become generalists,52 whereas the vast majority subspecialize.53 Multiple factors likely contribute to this finding. One study identified that both debt and intention to practice primary care were associated with plans to care for underserved populations, which raises the possibility that residents with debt may be more likely to select primary care fields as a means of serving underserved communities.54 Our findings are consistent with prior work suggesting that trainees with debt favor a shorter residency, but they are at odds with multiple studies suggesting that trainees with debt prefer higher-paying subspecialties.20 Students with debt may also be discouraged from applying to some highly competitive specialties because of costs associated with visiting rotations, a larger number of applications, and the need to travel for a greater number of interviews.55 Primary care physicians may benefit most from student loan relief.

Our finding that the decrease in debt prevalence over time was significantly smaller for trainees from populations underrepresented in medicine warrants further study. Prior work by the AAMC was not able to identify a clear cause for the overall decrease in debt prevalence.56 One as-yet-underexplored source is the growing number of medical schools that offer free tuition. One institution that introduced a means-tested debt-free education program noted an increase in matriculating students from populations underrepresented in medicine and from low-income backgrounds.57 However, it is unknown whether other institutions are seeing similar increases in diversity. Programs providing scholarships and medical schools providing free tuition could consider monitoring recipients’ demographics to ensure the equitable distribution of these financial resources.

The largest absolute differences by race and ethnicity were in loans for premedical education and consumer debt. Although our study looked at postgraduate resident trainees, our findings add to prior work suggesting that application costs and the prospect of additional loans discourage students from populations underrepresented in medicine from applying to medical school.58,59 This is supported by a dramatic increase in medical school applications from prospective students from these populations in 2021, when travel was not required for interviews, and a similar increase in the number of applicants who qualified for fee waivers.60 Further, consumer debt may be particularly stressful, given that it is unlikely to be deferred during training and may have high interest rates. Given the relatively smaller amounts of debt and larger racial and ethnic debt gaps, loan relief or guidance for loans obtained before medical school may be a good initial target for increasing diversity and inclusion within medicine.

The identified differences in debt prevalence are amenable to many policy solutions, including loan forgiveness, targeted repayment, and scholarships. For example, a US government–administered loan forgiveness program designed with equity in mind15 may increase diversity and inclusion within medicine. Existing loan repayment and scholarship programs also could be highlighted and expanded. For example, the National Health Service Corps offers scholarships and loan repayment for trainees entering primary care in underserved areas. Expanding those programs to include specialty care may increase diversity across specialties. Pre-health advisors and medical school counselors should be aware of these programs and discuss them with trainees. Scholarship programs may be particularly important for college students who would be interested in medicine but are discouraged by the prospect of additional debt. Prior work has identified that trainees who planned to serve underserved populations were also likely to plan to use loan forgiveness programs.54

Conclusion

In this study we found that Black postgraduate resident trainees were consistently most likely to have debt, to have debt before entering medical school, and to have multiple types of debt. We also found that all trainees from populations that are underrepresented in medicine were generally more likely to have debt compared with Asian and White trainees. Addressing disparities in debt burden may promote increased diversity and inclusion within medicine. This could be pursued through multiple avenues, including scholarships and expanded loan forgiveness programs. Institutions could also provide financial guidance to trainees and junior faculty members to reduce associated stress. Given the country’s interest in fostering a diverse health care workforce, addressing student loan debt may make matriculation to medical school, and success throughout medical training, more attainable for a diverse group of Americans.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This article was made possible by the National Clinician Scholars Program at Yale University and by Clinical and Translational Science Awards Grant No. TL1 TR001864 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science, a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the NIH. This article was also made possible by support provided by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Office of Academic Affiliations through the VA/National Clinician Scholars Program and Yale University. The contents do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government. Both Louisa Holaday and Jasmine Weiss were postdoctoral fellows in the Yale National Clinician Scholars Program when this study was initiated. Holaday currently receives research support through the National Institute on Aging, NIH (Grant No. T32AG066598). Hector Perez receives research support through the National Institute on Drug Abuse, NIH (Grant No. K23DA044327). Joseph Ross currently receives research support through Yale University from Johnson & Johnson to develop methods of clinical trial data sharing; from the Medical Device Innovation Consortium as part of the National Evaluation System for Health Technology; from the Food and Drug Administration for the Yale–Mayo Clinic Center for Excellence in Regulatory Science and Innovation program (Grant No. U01FD005938); from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Grant No. R01HS022882); from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, NIH (Grants Nos. R01HS025164 and R01HL144644); and from Arnold Ventures to establish the Good Pharma Scorecard at Bioethics International. In addition, Ross is an expert witness at the request of Relator’s attorneys, the Greene Law Firm, in a qui tam suit alleging violations of the False Claims Act and Anti-Kickback Statute against Biogen Inc. This material is based on data provided by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the AAMC. The authors thank Maureen Canavan for assistance with a key coding question, Lindsay Roskovensky for her guidance on the AAMC data, and Karenna Thomas for her assistance in formatting tables.

Contributor Information

Louisa W. Holaday, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York.

Jasmine M. Weiss, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Sire D. Sow, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Hector R. Perez, Montefiore Medical Center, New York, New York.

Joseph S. Ross, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.

Inginia Genao, Yale University..

NOTES

- 1.Yancy C, Bauchner H. Diversity in medical schools—need for a new bold approach. JAMA. 2021;325(1):31–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Association of American Medical Colleges. FACTS: applicants, matriculants, enrollment, graduates, MD-PhD, and residency applicants data.Washington (DC): AAMC; 2021. Nov 18. Table B-3, Total US MD-granting medical school enrollment by race/ethnicity (alone) and sex, 2017–2018 through 2021–2022. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lett E, Murdock HM, Orji WU, Aysola J, Sebro R. Trends in racial/ethnic representation among US medical students. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(9):e1910490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tilghman S, Alberts B, Colón-Ramos D, Dzirasa K, Kimble J, Varmus H. Concrete steps to diversify the scientific workforce. Science. 2021;372(6538):133–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gurin P, Dey E, Hurtado S, Gurin G. Diversity and higher education: theory and impact on educational outcomes. Harv Educ Rev. 2002;72(3):330–66. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitla DK, Orfield G, Silen W, Teperow C, Howard C, Reede J. Educational benefits of diversity in medical school: a survey of students. Acad Med. 2003;78(5):460–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bollinger LC. The need for diversity in higher education. Acad Med. 2003;78(5):431–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saha S, Guiton G, Wimmers PF, Wilkerson L. Student body racial and ethnic composition and diversity-related outcomes in US medical schools. JAMA. 2008;300(10):1135–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Onyeador IN, Wittlin NM, Burke SE, Dovidio JF, Perry SP, Hardeman RR, et al. The value of interracial contact for reducing anti-Black bias among non-Black physicians: a Cognitive Habits and Growth Evaluation (CHANGE) Study report. Psychol Sci. 2020;31(1):18–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Colburn L, Evans CH. The right thing to do, the smart thing to do: enhancing diversity in the health professions. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mineo L. Racial wealth gap may be a key to other inequities. Harvard Gazette [serial on the Internet]. 2021. Jun 3 [cited 2022 Oct 31]. Available from: https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2021/06/racial-wealth-gap-may-be-a-key-to-other-inequities/ [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kochhar R, Cilluffo A. Income inequality in the U.S. is rising most rapidly among Asians [Internet]. Washington (DC): Pew Research Center; 2018. Jul 12 [cited 2022 Oct 31]. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2018/07/12/income-inequality-in-the-u-s-is-rising-most-rapidly-among-asians/ [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhutta N, Chang AC, Dettling LJ, Hsu JW. Disparities in wealth by race and ethnicity in the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances [Internet]. Washington (DC): Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System; 2020. Sep 28 [cited 2022 Oct 31]. Available from: https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/disparities-in-wealth-by-race-and-ethnicity-in-the-2019-survey-of-consumer-finances-20200928.html [Google Scholar]

- 14.Asante-Muhammad D, Kamra E, Sanchez C, Ramirez K, Tec R. Racial wealth snapshot: Native Americans [Internet]. Washington (DC): National Community Reinvestment Coalition; 2022. Feb 14 [cited 2022 Nov 7]. Available from: https://ncrc.org/racial-wealth-snapshot-native-americans/ [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charron-Chénier R, Seamster L, Shapiro TM, Sullivan L. A pathway to racial equity: student debt cancellation policy designs. Soc Currents. 2021;9(1):4–24. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nguemeni Tiako MJ, South EC, Ray V. Medical schools as racialized organizations: a primer. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(8):1143–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodríguez JE, Campbell KM, Mouratidis RW.Where are the rest of us? Improving representation of minority faculty in academic medicine. South Med J. 2014;107(12):739–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Addo FR, Houle JN, Simon D.Young, Black, and (still) in the red: parental wealth, race, and student loan debt. Race Soc Probl. 2016;8(1):64–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Percheski C, Gibson-Davis C. A penny on the dollar: racial inequalities in wealth among households with children. Socius. 2020. June 1. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pisaniello MS, Asahina AT, Bacchi S, Wagner M, Perry SW, Wong ML, et al. Effect of medical student debt on mental health, academic performance, and specialty choice: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019;9(7):e029980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hill MR, Goicochea S, Merlo LJ. In their own words: stressors facing medical students in the millennial generation. Med Educ Online. 2018;23(1):1530558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Shanafelt TD. Medical student distress: causes, consequences, and proposed solutions. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80(12):1613–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.West CP, Shanafelt TD, Kolars JC. Quality of life, burnout, educational debt, and medical knowledge among internal medicine residents. JAMA. 2011;306(9):952–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garrett CC, Doonan RL, Pyle C, Azimov MB. Student loan debt and financial education: a qualitative analysis of resident perceptions and implications for resident well-being. Med Educ Online. 2022;27(1):2075303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kovar A, Carmichael H, Harms B, Nehler M, Tevis S. Over worked and under paid: how resident finances impact perceived stress, career choices, and family life. J Surg Res. 2021;258:82–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Young TP, Brown MM, Reibling ET, Ghassemzadeh S, Gordon DM, Phan TH, et al. Effect of educational debt on emergency medicine residents: a qualitative study using individual interviews. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;68(4):409–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grayson MS, Newton DA, Thompson LF. Payback time: the associations of debt and income with medical student career choice. Med Educ. 2012;46(10):983–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phillips JP, Peterson LE, Fang B, Kovar-Gough I, Phillips RL Jr. Debt and the emerging physician workforce: the relationship between educational debt and family medicine residents’ practice and fellowship intentions. Acad Med. 2019;94(2):267–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gray K, Kaji AH, Wolfe M, Calhoun K, Amersi F, Donahue T, et al. Influence of student loan debt on general surgery resident career and lifestyle decision-making. J Am Coll Surg. 2020;230(2):173–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kibbe MR, Troppmann C, Barnett CC Jr, Nwomeh BC, Olutoye OO, Doria C, et al. Effect of educational debt on career and quality of life among academic surgeons. Ann Surg. 2009;249(2):342–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeffe DB, Yan Y, Andriole DA. Competing risks analysis of promotion and attrition in academic medicine: a national study of U.S. medical school graduates. Acad Med. 2019;94(2):227–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dugger RA, El-Sayed AM, Dogra A, Messina C, Bronson R, Galea S. The color of debt: racial disparities in anticipated medical student debt in the United States. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e74693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Youngclaus J, Fresne JA. Physician education debt and the cost to attend medical school: 2020 update [Internet]. Washington (DC): Association of American Medical Colleges; 2020. Oct [cited 2022 Nov 3]. Available from: https://store.aamc.org/downloadable/download/sample/sample_id/368/ [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grischkan J, George BP, Chaiyachati K, Friedman AB, Dorsey ER, Asch DA. Distribution of medical education debt by specialty, 2010–2016. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(10):1532–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Association of American Medical Colleges. Report on residents (various years) [Internet]. Washington (DC): AAMC; [cited 2022 Nov 7]. (Executive Summaries). Available for download from: https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/students-residents/report/report-residents [Google Scholar]

- 36.To access the appendix, click on the Details tab of the article online.

- 37.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ. 2007;335(7624):806–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ulmer C, McFadden B, Nerenz DR, editors. Race, ethnicity, and language data: standardization for health care quality improvement. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sondheimer HM, Xierali IM, Young GH, Nivet MA. Placement of US medical school graduates into graduate medical education, 2005 through 2015. JAMA. 2015;314(22):2409–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Asante-Muhammad D, Sim S. Racial wealth snapshot: Asian Americans and the racial wealth divide [Internet]. Washington (DC): National Community Reinvestment Coalition; 2020. May 14 [cited 2022 Oct 31]. Available from: https://ncrc.org/racial-wealth-snapshot-asian-americans-and-the-racial-wealth-divide/ [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shahriar AA, Puram VV, Miller JM, Sagi V, Castañón-Gonzalez LA, Prasad S, et al. Socioeconomic diversity of the matriculating US medical student body by race, ethnicity, and sex, 2017–2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(3):e222621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nguyen M, Chaudhry SI, Desai MM, Chen C, Mason HRC, McDade WA, et al. Association of sociodemographic characteristics with US medical student attrition. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182(9):917–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baldwin DC Jr, Rowley BD, Daugherty SR, Bay RC. Withdrawal and extended leave during residency training: results of a national survey. Acad Med. 1995;70(12):1117–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Osseo-Asare A, Balasuriya L, Huot SJ, Keene D, Berg D, Nunez-Smith M, et al. Minority resident physicians’ views on the role of race/ethnicity in their training experiences in the workplace. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(5):e182723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anderson N, Lett E, Asabor EN, Hernandez AL, Nguemeni Tiako MJ, Johnson C, et al. The association of microaggressions with depressive symptoms and institutional satisfaction among a national cohort of medical students. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(2):298–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hill KA, Samuels EA, Gross CP, Desai MM, Sitkin Zelin N, Latimore D, et al. Assessment of the prevalence of medical student mistreatment by sex, race/ethnicity, and sexual orientation. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(5):653–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boatright D, Ross D, O’Connor P, Moore E, Nunez-Smith M. Racial disparities in medical student membership in the Alpha Omega Alpha honor society. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(5):659–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ross DA, Boatright D, Nunez-Smith M, Jordan A, Chekroud A, Moore EZ. Differences in words used to describe racial and gender groups in Medical Student Performance Evaluations. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0181659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ginther DK, Haak LL, Schaffer WT, Kington R. Are race, ethnicity, and medical school affiliation associated with NIH R01 type 1 award probability for physician investigators? Acad Med. 2012;87(11):1516–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nunez-Smith M, Ciarleglio MM, Sandoval-Schaefer T, Elumn J, Castillo-Page L, Peduzzi P, et al. Institutional variation in the promotion of racial/ethnic minority faculty at US medical schools. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):852–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ly DP, Seabury SA, Jena AB. Differences in incomes of physicians in the United States by race and sex: observational study. BMJ. 2016;353:i2923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Diehl AK, Kumar V, Gateley A, Appleby JL, O’Keefe ME. Predictors of final specialty choice by internal medicine residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(10):1045–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.West CP, Dupras DM. General medicine vs subspecialty career plans among internal medicine residents. JAMA. 2012;308(21):2241–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garcia AN, Kuo T, Arangua L, Pérez-Stable EJ. Factors associated with medical school graduates’ intention to work with underserved populations: policy implications for advancing workforce diversity. Acad Med. 2018;93(1):82–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tabakin AL, Srivastava A, Polotti CF, Gupta NK. The financial burden of applying to urology residency in 2020. Urology. 2021;154:62–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Youngclaus J. An exploration of the recent decline in the percentage of US medical school graduates with education debt [Internet]. Washington (DC): Association of American Medical Colleges; 2018. Sep [cited 2022 Oct 31]. (Analysis In Brief, Vol. 18, No. 4). Available from: https://www.aamc.org/media/9411/download [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kang Y, Ibrahim SA. Debt-free medical education—a tool for health care workforce diversity. JAMA Health Forum. 2020;1(12):e201435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Millo L, Ho N, Ubel PA. The cost of applying to medical school—a barrier to diversifying the profession. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(16):1505–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jolly P. Medical school tuition and young physicians’ indebtedness. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(2):527–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Boyle P. Medical school applicants and enrollments hit record highs; underrepresented minorities lead the surge [Internet]. Washington (DC): Association of American Medical Colleges; 2021. Dec 8 [cited 2022 Oct 31]. Available from: https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/medical-school-applicants-and-enrollments-hit-record-highs-underrepresented-minorities-lead-surge [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.