Abstract

Coronavirus has an impact on millions of lives and has been added to the important pandemics that continue to affect with its variants. Since it is transmitted through the respiratory tract, it has had significant effects on public health and social relations. Isolating people who are COVID positive can minimize the transmission, therefore several exams are proposed to detect the virus such as reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), chest X-Ray, and computed tomography (CT). However, these methods suffer from either a low detection rate or high radiation dosage, along with being expensive. In this study, deep neural network–based model capable of detecting coronavirus from only coughing sound, which is fast, remotely operable and has no harmful side effects, has been proposed. The proposed multi-branch model takes M el Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCC), S pectrogram, and C hromagram as inputs and is abbreviated as MSCCov19Net. The system is trained on publicly available crowdsourced datasets, and tested on two unseen (used only for testing) clinical and non-clinical datasets. Experimental outcomes represent that the proposed system outperforms the 6 popular deep learning architectures on four datasets by representing a better generalization ability. The proposed system has reached an accuracy of 61.5 % in Virufy and 90.4 % in NoCoCoDa for unseen test datasets.

The Architecture of the Proposed MSCCov19Net Model for Covid-19 Detection

Keywords: Coronavirus, Coughing, Deep learning, Ensemble learning, Telehealth

Introduction

Up to date, there have been 524,878,064 confirmed cases of COVID-19 (CO ronaVI rus D isease 2019), including 6,283,119 deaths, reported by World Health Organization (WHO) [1], and cases are still increasing worldwide. Therefore, rapid and self testing tools for COVID-19 are more important than ever before not only to confirm cases, but also to prevent the spread by taking precautionary steps such as quarantine, self isolation amongst the others.

The main COVID-19 diagnostic tool is presently the RT-PCR test (i.e. the swab test), yet this is an expensive and invasive test, and most of the time it requires to take the patient to a test centre, which might not be feasible in many cases because of the severity of the case, moving ability of the patient etc.

Due to the aforementioned reasons, there have been several attempts to develop rapid, portable and self-applicable COVID-19 diagnostic tools. However, this is a challenging task, since the COVID-19 virus has intertwined symptoms with influenza or other respiratory diseases and cannot be distinguished easily, especially in winter season (when influenza or respiratory diseases circulate more). The primary symptoms of COVID-19 are loss of smell, loss of taste, continuous cough, fever and high temperature [2]. Vaccine, wearing mask and social distancing are the primary measures taken for the controlling the spread of this disease [3]. Hence, the clinicians/physician are in urgent need of novel tools to diagnose/confirm COVID-19 cases.

For this reason, machine learning–based methods have recently received a great attention for COVID-19 diagnosis. Amongst them, analysis of coughing audio signal has a tremendous importance, as COVID-19 is predominantly manifest as coughing, and it has unique characteristics belonging to COVID-19 [2, 4, 5].

In this manuscript, we come up with a deep learning–based COVID-19 diagnostic/confirmation tool that utilizes coughing audio signal. Our aim is to increase the detection accuracy so that the transmission of the virus can be diminished by taking necessary steps. The proposed method utilizes multi-branch Neural Networks by combining the features that are extracted from different domains of the coughing audio signal. Technical details of each part of the proposed approach are presented in Section 3 and validated on several datasets (see Sections 4.1 and 5) against state-of-the-art deep learning–based architectures explained in Section 5.1.

Related works

RT-PCR tests are used to validate COVID-19 infection. One other diagnostic tool for COVID-19 is medical imaging systems such as chest X-ray and CT. Furthermore, these approaches validate misclassifications resulting from RT-PCR tests. However, these are even more expensive tools and cannot be used on some vulnerable patient groups (such as pregnant) due to the radiation emitted. The need for computerized analysis for fast and accurate diagnosis comes to the fore during this pandemic. Several works using automatic deep learning algorithms on CT scans [6–10] and machine learning algorithms on cough sounds [11–22] are proposed in literature. The works on CT scans [6–10] provide information about the degree of severity of the individual’s lung damage. In a recent survey [23], numerous studies and open source datasets on CT have been examined. According to [23], it is reported that open cough-based COVID-19 datasets are few and their sizes are small. In [11], the authors combined handcrafted features with Visual Geometry Group (VGG) features and reached an Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 0.82 using only 86 cough samples. Feeding MFCC spectrograms as input to Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) architecture, an accuracy of 92.85 % was reported on 543 cough sounds (of which 70 of them was COVID-19) in the work of [12]. In [13], an ensemble of CNN classifiers is employed and an AUC of 0.77 is reached on 1502 recordings. Using CNN-based deep learning model, an AUC of 0.71 is reached on 1486 samples fusing voice, coughing and breathing information in [14]. On a dataset of 1273 samples, the work of [15] employed cough-specific CNN, pre-trained Residual Network (ResNet) model, gender-specific pre-trained ResNet model achieving an AUC of 0.62, 0.70 and 0.71, respectively. In [16], using MFCC features as input and Support Vector Machine (SVM) as classifier with the advantage of the speech enhancement technique, accuracies of 74.1 % and 85.7 % are reached on two separate datasets. However, the highest value of 0.5144 was reached as AUC value on cough sounds. Using MFCC as input to ensemble CNN model based on ResNet50, the authors in [17] achieved an AUC of 0.97 on their private dataset consisting of 5320 subjects. Employing an architecture like LeNet-1, an accuracy rate of 97.5 % is reached on a small test set of 18 samples in [18]. In [19], an AUC of 0.846 is reached on 517 samples using breath and cough information. However, using only cough recordings of 53 subjects, an AUC of 0.57 is achieved employing ResNet-based model. In [20], using cough sounds of 76 post-COVID-19 and 40 healthy subjects an accuracy of 67 % is obtained utilizing VGG19 CNN model. In [21], an AUC of 0.771 is reached on a total of 2883 cough sounds using MFCC and extra features such as the presence of respiratory diseases, fever, and muscle pain. A detailed comparison of the related works is given in Table 1. When we consider the studies using crowdsourced data in the literature, we found that the CNN-based study with the largest number of publicly available samples is [21]. Therefore, we used the work of [21] as the baseline comparison and referred to it as the Baseline Model throughout the manuscript. We noticed from the existing studies that the proposed deep learning models are not validated whether they are generalizable or not with testing unseen datasets.

Table 1.

A detailed comparison of the related works on cough-based (top part) and image-based (bottom part) approaches for COVID-19 detection

| Work | Year | Dataset | # of samples | Method | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown et al. [11] | 2020 | COVID-19 Sounds | 86 | Handcrafted + VGG | AUC 0.82 |

| Imran et al. [12] | 2020 | Own dataset | 543 | CNN | Acc 92.85 |

| Mohammed et al. [13] | 2021 | Virufy, Coswara | 1502 | Ensemble CNN | AUC 0.77 |

| Xia et al. [14] | 2021 | COVID-19 Sounds | 1486 | CNN | AUC 0.71 |

| Mallol-Ragolta et al. [15] | 2021 | DICOVA Challenge | 1273 | ResNet | AUC 0.71 |

| Dash et al. [16] | 2021 | Coswara, COVID-19 Sounds | 200 | MFCC + SVM | Acc 85.70 |

| Laguarta et al. [17] | 2020 | MIT Open Voice | 5320 | MFCC + ResNet50 | AUC 0.97 |

| Soltanian et al. [18] | 2022 | Virufy | 18 | LeNet-1 | Acc 97.50 |

| Coppock et al. [19] | 2021 | COVID-19 Sounds | 517 | ResNet | AUC 0.85 |

| Suppakitjanusant et al. [20] | 2021 | Own dataset | 116 | VGG19 | Acc 67.00 |

| Chaudhari et al. [21] | 2020 | Virufy | 2883 | MFCC + Extra features | AUC 0.77 |

| Akgun et al. [22] | 2021 | Cambridge data | 779 | MFCC + MobileNet | Acc 86.42 |

| Kiziloluk et al. [6] | 2022 | COVID-19 | 3829 | CNN | Acc 98.11 |

| Amyar et al. [7] | 2020 | HBCC COVID-19 | 1369 | Multi-task deep learning | Acc 94.67 |

| CT segmentation | |||||

| Covid-CT-dataset | |||||

| Wang et al. [8] | 2021 | Own dataset | 1065 | Modified Inception | Acc 89.50 |

| Narin et al. [9] | 2021 | Covid-chestxray-dataset | 3141 | ResNet | Acc 96.10 |

| ChestX-ray8 | |||||

| Ilhan et al. [10] | 2021 | ChestX-ray8 | 1125 | Decision and feature | Acc 90.84 |

| Covid-chestxray-dataset | 1478 | level fusion | Acc 90.50 | ||

| Actualmed COVID-19 Dataset | 1591 | Acc 90.70 |

The highest accuracy (Acc) and area under the curve (AUC) scores are taken from the corresponding papers respectively

Proposed models

In this paper, we develop four alternative deep learning–based COVID-19 detection models, namely MFCC-based, Spectrogram-based, Chromagram-based and ensemble MSCCov19Net models after deep investigations, analysis and trials. We ultimately test and compare their performances through successive experiments.

MFCC-based model

MFCCs are well-known hand-crafted attributes that have been observed to be one of the most useful features in the area of audio signal processing [24–26]. They are extracted from mel-frequency cepstrum (MFC), which can be defined as a short-term characterization of the power spectrum of an audio waveform, founded on a direct cosine transform of a log power. For this work, we extract 39 MFC coefficients from a coughing audio signal. To extract the MFC coefficients, we use Python-librosa audio signal processing package [27]. More precisely, the coughing audio waveform is first resampled to 22.5 KHz, then the feature extraction function is applied to the signal by using a hop length of 23 ms, window length of 93 ms, and a Hann window type. The output MFCC features are then averaged along the time-axis and converted into 1D 39 coefficients.

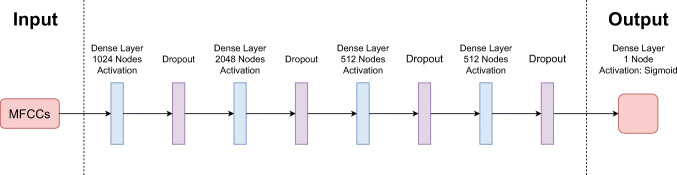

For this model, we create a small Multi Layer Perception (MLP) network (as it can be seen in Fig. 1), which consists of 4 fully connected (FC) layers and a single output layer. Each FC layer contains 1024, 2048, 512 and 512 nodes respectively with Rectified Linear Unit (ReLu) activation functions and dropout layers. The last dense layer is a single node with Sigmoid activation that gives the probability of the covidness of the given cough signal.

Fig. 1.

The complete architecture of the MFCC-based model

Spectrogram-based model

Spectrogram

is a visual illustration of the range of frequencies of a given waveform while it changes with time. To put it another way, it can be thought as a 2D signal that shows the relation between time and frequency. Recently, spectrograms have been used as input to many CNN architectures to achieve various ultimate goals, including speech recognition [28, 29], speaker verification [30, 31] and speech enhancement [32, 33]. Inspired by the previous motivational works, we propose to use spectrograms to extract meaningful information from cough audio signals. Spectrograms are extracted via librosa library by using the previously obtained MFC coefficients, then rescaled to 128 × 40 and normalized to [0,1] before inputted to the proposed network.

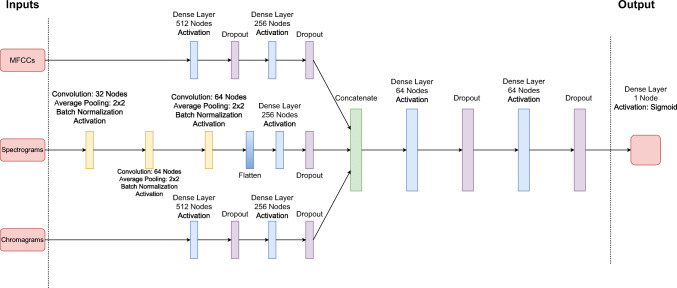

As Spectograms are 2D signals, we create a small Convolutional Deep Neural Network (CDNN) architecture (as it can be observed in Fig. 2), which is inspired by the seminal VGG network [34–36]. The network contains 3 convolutional layers, a flatten layer, and 3 FC layers and a single output layer for classification. The convolutional layers contain composite functions that consists of a convolution function with 32, 64, and 64 filter sizes respectively, a ReLu activation layer, a max pooling layer of 2 × 2 filter size with stride 2 and a Batch Normalization layer. The FC layers, on the other hand, contain 256, 64 and 64 nodes respectively with ReLu activation functions and dropout layers. The last dense layer is also a single node with Sigmoid function. The spectrogram images are rescaled to 128 × 40 to feed the network.

Fig. 2.

The complete architecture of the spectrogram-based approach

Chromagram-based model

Chromagram

which can also be expressed as Harmonic Pitch Class Profile, contains the energy distribution of an audio wave along the pitches [37]. Chroma-based features are highly used on audio signals to analyze meaningfully categorizable pitches [38–40]. For this work, we extract 12-element 1D features (via librosa) from each coughing audio signal and use them as input to feed the proposed network.

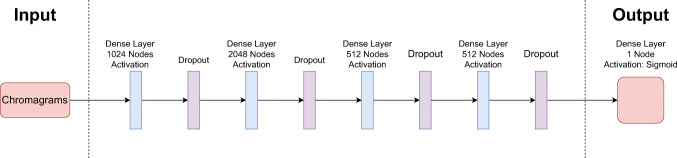

For this model, we use a similar MLP architecture to MFCC-based model. The model consists of 4 FC layers and a single output layer. Each FC layer contains 1024, 2048, 512 and 512 nodes respectively with ReLu activation functions and dropout layers. The last dense layer is a single node with Sigmoid function. The utilized model can be seen in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

The complete architecture of the chromagram-based approach

Ensemble MSCCov19Net model

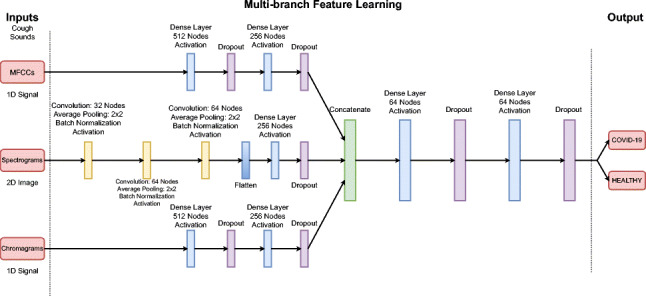

We finally propose a multi-branch CNN architecture called MSCCov19Net to detect COVID-19 from a given coughing audio signal only. The proposed architecture combines previously explained neural features extracted from diverse domains: MFCC features, Spectrogram images and Chroma features (Chromagram) of the coughing audio signal.

The overall architecture of the proposed ensembled neural network can be seen in Fig. 4. The proposed MSCCov19Net network consists of three branches, and each branch extracts distinct and informative neural features from aforementioned sources, then these neural features are concatenated and sent to the classification network.

Fig. 4.

The complete architecture of the proposed MSCCov19Net network

The first branch extract neural features , where from MFCC, using 2-layers of dense nodes. The first dense layer consists of 512 nodes with ReLU activation operation and a Dropout layer. The second dense layer, on the other hand, contains 256 nodes with ReLU activation function and a Dropout layer. Dropout layers are used to mitigate overfitting.

The second branch extracts neural features , where , from spectrogram images of size 128 × 40. The network contains 3-layers of composite functions, a flatten layer, a dense layer of 256 nodes and a Dropout layer. Each composite function consists of a convolutional layer with 32, 64, and 64 filter sizes respectively, a ReLu activation layer, a max pooling layer of 2 × 2 filter size with stride 2 and a Batch Normalization layer.

The architecture of the third branch to extract neural features of size , where , from Chroma-based features is similar to the MFCC branch. The model consists of 2-layers of dense nodes with 512 and 256 nodes respectively. Each layer also contains a ReLU activation function and a Dropout layer.

Finally, extracted neural features are combined to create a composite neural feature vector as follows:

| 1 |

where [;] depicts the concatenation operation, , and are the extracted neural features from MFCCs, Spectrogram images and Chroma-based features respectively, and is the composite neural feature vector of size 768 × 1. The extracted composite neural feature vector is then sent to the classification network which is a shallow network consisting of fully connected layers. More precisely, it contains 2-layers of dense neural blocks of which 64 filters with ReLU activations and Dropout layers. The last node is a single unit neural block with Sigmoid function, which gives the probability of being COVID-19 positive for a given coughing audio signal.

Experimental setup

Datasets

Aiming to train and validate the proposed methods, we employ several publicly available datasets: Coughvid [41], Coswara [42], Virufy [21] and NoCoCoDa [43].

Coughvid

is a crowdsourced dataset that contains 20,072 audio data. 1010 labeled COVID-19, 8562 labeled healthy, 1742 labeled symptomatic and 8758 of them have not been labeled. Some of the files in the Coughvid dataset include non-cough sounds and environmental noise. In order to have clean data for training, 651 COVID-19-labeled files and 660 healthy-labeled audio files were manually selected. Symptomatic labeled and unlabeled files were excluded from this study. Coswara dataset contains data from 1503 patients. Each with the following: deep breathing, shallow breathing, heavy cough, shallow cough, counting from zero to twenty slow and fast, vowel phonation for letters “a”, “e” and “o”. For this paper, we used heavy and shallow cough sounds. For experiments, “positive_asymp”, “positive_mild” and “positive_moderate” labeled data were used for COVID-19 class while the remaining for healthy class. Virufy is a clinical dataset. It contains data that is acquired in the clinical environment from 16 patients. Seven of them labeled positive and 9 of them labeled negative for COVID-19 which is validated using PCR test results. NoCoCoDa is a non-clinical dataset. There are 73 annotated cough events obtained from 10 patients. This dataset contains only COVID-19 positive reflex cough sounds. The cough segments are annotated from online media interviews and background noise such as talking or music is present on some of the records. In this study, the original recordings were used without any pre-processing step in order to alleviate the present noise. The types of sound files in the Coughvid database are .webm and .ogg, in the Coswara database are .wav, in the Virufy database are .mp3, and in the NoCoCoDa database are .wav format. We converted all the files to .wav format without applying noise reduction to the sounds.

For training purposes, the Coswara and Coughvid datasets are combined, and divided into training-validation-test groups by using 80%-10%-10% split ratio. The Virufy and NoCoCoDa dataset, on the other hand, are only used for inference to cross-validate the proposed model. In other words, none of the data from Virufy and NoCoCoDa is used in the training step but in testing step.

We extract cough segments using the provided code presented in the Coswara/Coughvid dataset in order to carry out data extraction. Total number of extracted segments are 2960/370/370 respectively for training/validation/testing.

Implementation details and training procedure

The proposed deep learning model is implemented using Tensorflow 2.3.0 Python library. A binary cross-entropy loss function and a Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) optimizer are utilized for training purposes. We use an adaptive learning rate strategy by starting at 0.1 that is divided by 10 at every 100 epochs with a batch size of 8. The network is trained 1000 epochs.

In order to have the optimum performance from the proposed model, we use the combination of the following hyper-parameters:

Optimizers: Adadelta, Adam, Adamax, RMSprop, SGD

Activation Functions: ReLU, Sigmoid, Softmax, Softplus, Tanh

Dropout Rate: 0.0, 0.3, 0.5, 0.8, 0.9

Optimal hyper-parameters described above (optimizer, activation function, dropout rate, etc.) are chosen via grid search strategy.

In order to avoid overfitting and provide a better generalization, we use data augmentation before, and regularization during the training phase. Data augmentation is conducted through “Pitch Shifting” and “Noise Addition” by applying them to cough audio signals on the training dataset, and regularization is conducted via a composite element on the classification network, which is defined as,

| 2 |

where λ1 and λ2 are the weighting coefficients and set to 0.01 empirically.

Experimental results

Aiming to evaluate the proposed approaches quantitatively, we present accuracy (Acc) scores along with the Area Under the Curve (AUC) scores on Coswara/Coughvid, Virufy and NoCoCoDa test sets with the model trained only on Coswara/Coughvid dataset.

Firstly, we discuss the individual performance of each proposed model. The results on Coswara/Coughvid dataset are represented in Table 2. It can be concluded that the quantitative results validate the robustness of the proposed multi-branch network by obtaining 4.5 % increase on classification accuracy and 2.9 % increase on AUC score from the second best approach (MFCC-based). The table also shows that the Chroma-based model presents the lowest performance, probably due to environmental noise (speech and music) in the crowdsourced datasets, in fact this behaviour (sensitiveness to noise) is reported before in [44, 45]. On the other hand, the multi-branch model provided a significant increase in performance thanks to multiple perspectives and diverse domain knowledge obtained from 1D and 2D features. As, to the best of our knowledge, there is currently no approach that uses Chroma-based features for this task specifically, we re-train the network with and without Chromagram branch in order to see the effect of Chroma features on the multi-branch network MSCCov19Net. It can be also noted from the table that there is a significant improvement in performance when Chroma-based features are used on the multi-branch network MSCCov19Net. Although we do not have a clear explanation for this particular behaviour, boosted performance unlike the low performance of its standalone usage, we believe that using multiple perspectives and diverse domain knowledge on the multi-branch network MSCCov19Net mitigates the noise sensitivity of the Chroma-based features.

Table 2.

Comparison of the proposed model with the individual branches tested on the Coswara/Coughvid dataset (trained on Coswara/Coughvid)

| Method | Accuracy | AUC |

|---|---|---|

| MFCC-based | 0.703 | 0.766 |

| Spectrogram-based | 0.500 | 0.536 |

| Chromagram-based | 0.500 | 0.465 |

| MSCCov19Net w/out Chroma | 0.716 | 0.789 |

| MSCCov19Net | 0.748 | 0.795 |

The bold value denotes the best performance

To further assess the proposed approach, we make a cross-validation test on Virufy (clinical and clean) dataset. In other words, we train the proposed method on Coswara/Coughvid dataset and test only on Virufy dataset.

The cross-validated outcomes on Virufy dataset are represented in Table 3. It can be concluded that, the quantitative results on the table confirmed the robustness of the proposed multi-branch method by obtaining 3.4 % increase on classification accuracy of the second best approach (MFCC-based) and 8.4 % increase on AUC score from the second best approach (Chromagram-based). Since the Virufy dataset is obtained in a clinical and controlled environment, environmental noise is minimum, so we can speculate that this is the reason why the Chroma channel has a noticeable higher AUC score than the previous experiment.

Table 3.

Comparison of the proposed model with the individual branches tested on the Virufy dataset (trained on Coswara/Coughvid)

| Method | Accuracy | AUC |

|---|---|---|

| MFCC-based | 0.581 | 0.627 |

| Spectrogram-based | 0.468 | 0.456 |

| Chromagram-based | 0.468 | 0.648 |

| MSCCov19Net | 0.615 | 0.732 |

The bold value denotes the best performance

Performance comparison with the state-of-the-art architectures

In this part, we compare the performance of MSCCov19Net with diverse deep CNN architectures: a basic CNN model [36], ResNet50 [46], EfficientNetB0 [47], MobileNetV2 [48], Xception [49] and the baseline model proposed in [21].

ResNets explore residual operations based on layer input, in lieu of exploring non-referenced operations as in traditional CNN layers. EfficientNet uses a scaling approach that adjusts all sizes of input resolution, depth and width employing combined coefficients. MobileNetV2 is a 53 layers deep CNN that aims to operate well on mobile resources. Xception is a 71 layers deep CNN that relies solely on depth-wise separable convolution layers. The methods used for comparison are trained using similar hyper-parameter settings as the proposed method.

We train ResNet50, EfficientNetB0, MobileNetV2 and Xception models using the Adam optimizer with learning rate of 0.001, binary cross-entropy loss and batch size of 32. Basic CNN architecture consists of three convolution layers with node sizes of 128, 256, 256 and kernel sizes of 3. Followed by three FC layers with node sizes of 256 and an output layer with 1 node. ReLU activation function and 0.5 dropout rate were used on all layers except for the last layer. In last layer, we used Sigmoid function. For this network, an SGD optimizer with 0.01 learning rate is used.

We first illustrate the results on Coswara/Coughvid dataset in Table 4. As it can be inferred from the table, our approach reaches the highest accuracy and AUC scores among all other approaches. Furthermore, we show the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) plot in Fig. 5 (left). It can be clearly concluded that the proposed method has a significant overall increase on both accuracy metrics.

Table 4.

Comparison with the state-of-the-art methods tested on the Coswara/Coughvid datasets (trained on Coswara/Coughvid)

| Method | Accuracy | AUC |

|---|---|---|

| Basic CNN [36] | 0.616 | 0.653 |

| EfficientNetB0 [47] | 0.562 | 0.648 |

| MobileNetV2 [48] | 0.581 | 0.626 |

| Xception [49] | 0.565 | 0.633 |

| ResNet50 [46] | 0.640 | 0.691 |

| Baseline Model [21] | 0.721 | 0.770 |

| MSCCov19Net | 0.748 | 0.795 |

The bold value denotes the best performance

Fig. 5.

ROC curves (left figure) of each individual approach (in Table 4) trained and tested on Coswara/Coughvid dataset and ROC curves (right figure) of each individual approach (in Table 5) trained on Coswara/Coughvid dataset and tested on Virufy dataset

Evaluation scores with the state-of-the-art models on Virufy test set can be examined in Table 5. Likewise, the quantitative outcomes on the table confirmed the robustness of the proposed model by yielding 1.7 % increase on classification accuracy of the second best approach (Baseline Model) and 4.2 % and 7.8 % increase on AUC scores from the second best approach (Basic CNN) and the third best approach (Baseline Model), respectively. Similarly, ROC plots can be seen in Fig. 5 (right).

Table 5.

Comparison with the state-of-the-art methods tested on the Virufy dataset (trained on Coswara/Coughvid)

| Method | Accuracy | AUC |

|---|---|---|

| Basic CNN [36] | 0.589 | 0.690 |

| EfficientNetB0 [47] | 0.548 | 0.602 |

| MobileNetV2 [48] | 0.581 | 0.563 |

| Xception [49] | 0.605 | 0.540 |

| ResNet50 [46] | 0.524 | 0.400 |

| Baseline Model [21] | 0.598 | 0.654 |

| MSCCov19Net | 0.615 | 0.732 |

The bold value denotes the best performance

Moreover, aiming to see the efficiency of the proposed approach, another unseen test dataset called NoCoCoDa (non-clinical), is employed. The classification accuracy of the compared approaches can be observed in Table 6. The proposed model outperforms the Baseline Model with a 21.9 % accuracy increase representing superior generalization ability. Besides that, the performance of the proposed method is 13.7 % higher in accuracy than the basic CNN. It can be concluded from Table 6, MSCCov19Net yields superior and promising results on an unseen test set considering the previous studies on cough-based COVID-19 detection. Since NoCoCoDa dataset includes only COVID-positive reported subjects, the AUC scores are not reported.

Table 6.

Comparison with the state-of-the-art approaches tested on the NoCoCoDa dataset (trained on Coswara/Coughvid)

| Method | Accuracy |

|---|---|

| Basic CNN [36] | 0.767 |

| EfficientNetB0 [47] | 0.541 |

| MobileNetV2 [48] | 0.564 |

| Xception [49] | 0.532 |

| ResNet50 [46] | 0.507 |

| Baseline Model [21] | 0.685 |

| MSCCov19Net | 0.904 |

The bold value denotes the best performance

The inference and training time analysis of the proposed method along with the state-of-the-art approaches are given in Table 7. Inference time represents the average classification time for a single cough audio signal. On the other hand, training time shows the average training time for a single epoch. It can be concluded that the proposed method is suitable for remote and real-time operation by looking at the inference time information. Experiments were conducted with i7-7700K 4.20GHz processor, 16GB RAM, and GTX1060 6GB GPU.

Table 7.

Comparison of the inference time (in milliseconds) and training time (in seconds) of the proposed method along with the state-of-the-art approaches

Discussion

RT-PCR technique is a baseline indicator for COVID-19 detection using pharyngeal swabs. However, it suffers from false negative rate, low detection capability and long test result waiting time [50–53].

While RT-PCR results are negative, results confirming ground-glass symptoms of COVID-19 have been reported in CT results [54]. Therefore, in suspected cases, CT confirmation after RT-PCR is recommended in literature [51, 52]. Although CT presents high sensitivity than RT-PCR [51, 55], it is not practical due to radiation damage, waiting time, and being expensive. Moreover, a patient who has a positive RT-PCR result may has a normal CT result before the beginning of indications as reported in [56]. Lower specificity is one of the main drawbacks of CT-based studies as reported in [57]. Either RT-PCR or CT-based diagnosis requires clinical visit and this situation results in breaching of isolation and social distance rule. This situation also applies to COVID-19 detection based on blood tests obtained by invasive methods, which are used as clinical data [58, 59]. However, machine learning–based remote cough sound analysis is a promising candidate for medical decision support systems for the determination of COVID-19 minimizing clinical visits.

Due to the scarcity of publicly available datasets compared to CT studies [23, 53], COVID-19 detection studies on cough sounds are less than CT studies even though the cough is one of the major symptoms. There are some limitations on COVID-19 determination based on artificial intelligence techniques. At first, outsourced data may include noisy and mislabeled samples reducing the performance of classification models. Secondly, datasets may be imbalanced providing an insufficient number of COVID-19 positive samples. At last, environmental factors may introduce bias when recording cough sounds. Furthermore, once the train, test, and validation sets are not disjoint the performance of the models may be biased [60]. These challenges make cross-datasets validation necessary to obtain robust and generalizable results. Therefore, since crowdsourced datasets include plenty of samples, we cross-validated the performance of the model using a clinical (controlled) and non-clinical dataset that has few samples taking into account the above-mentioned issues.

This study has some limitations due to the available datasets. Working on noisy data which is collected from different mobile devices negatively affects the performance of the proposed model. Furthermore, audio transmission over VoIP or cellular network is subject to compression, which can change the quality of the audio. Consequently, this may also negatively affect the performance of the proposed method.

In the literature, there are few works on cough-based COVID-19 detection. Most of them report their results either on small and controlled datasets or without cross-validating the performance on different datasets. As a solution, we employed the commonly used CNN architectures for comparison by not only training/testing on Coswara/Coughvid dataset but also cross-validating on the Virufy and NoCoCoDa datasets. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first model to cross-validate crowdsourced cough data with clinically validated and non-clinical cough data and use four separate datasets for the purpose of COVID-19 detection using cough sounds.

Conclusion

In this paper, we have presented a supervised deep neural network–based cough sound analysis for COVID-19 detection, which provides state-of-the-art performance on the benchmark datasets in metrics such as Accuracy and AUC. The proposed multi-branch network MSCCov19Net has better generalization capability than recent neural network models. As a future perspective, we intend to explore the long-term effects of COVID-19 by applying sound analysis approaches on lung sound data acquired using electronic stethoscopes/phones. This concept might follow the social distancing rule during the sample collection using smart applications or in sheltered cabins. In fact, most of the time lung sounds are collected from the back of the patient, which might minimize to receive saliva droplets that contain the virus by healthcare workers. Ideally, when a specific and acceptable accuracy is reached, these algorithms may be helpful in validating the prediction of RT-PCR tests (as sometimes repeated tests are required due to the mis-classifications [50]) in a remote and non-invasive way. Additionally, in recent years, studies on remote Parkinson’s detection with sound [61] have shown promising results even using the standard telephone network [62]. Suppose a sufficiently diverse and labeled voice dataset can be collected with mobile applications, the proposed deep learning–based system can be embedded within a cloud-based infrastructure, allowing for fast and large-scale screening. Therefore, this system can be trained to give an idea about the degree of involvement in the lungs by confirming it with simultaneous CT acquisition, and it can also reduce the harmful X-ray exposure of individuals. Since the COVID-19 cough sound literature has just begun to develop, it will be extremely important to collect follow-up data of COVID-19 patients for the progression [63] and grading of the disease in the future in terms of person-specific disease follow-up. Recently, Internet of Things–based wireless approaches have been proposed for remote health data monitoring [64, 65]. Thus, it may be adapted for rapid detection of other future diseases that may affect the lungs.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all healthcare professionals who have taken a crucial role in the fight against COVID-19 and all authors who have made cough data available to researchers.

Biographies

Sezer Ulukaya

He received PhD degree in lung sounds in EEE Dept. at Boğaziçi University, Turkey. Since 2018, he is an assistant professor in EEE Dept. at Trakya University. He has won the first place in the scientific challenge on Respiratory Signal Processing which was sponsored by the IFMBE.

Ahmet Alp Sarıca

He received his B.Sc. degree in EEE Dept. at Trakya University in 2021. He is now working towards M.Sc. at Marmara University, Istanbul, Turkey. He is currently working as an artificial intelligence engineer mainly focused on deep learning algorithms.

Oğuzhan Erdem

He is currently an associate professor at Trakya University, Turkey. He received his PhD (2011) in EEE from the Middle East Technical University. He is holder of a triadic patent on high speed computing. Currently, he conducts a project on multimodal analysis of Parkinson’s disease.

Ali Karaali

He is a Research Fellow in Trinity College Dublin, Ireland. His expertise includes computer vision, machine and deep learning. He has several papers in top-tier journals (e.g. Transactions on Image Processing). Currently, he works on health informatics.

Funding

Ali Karaali is partly funded by Department of Nephrology, St. James’s Hospital, Dublin Ireland.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the following repositories; Coswara: https://github.com/iiscleap/Coswara-Data, Coughvid: https://zenodo.org/record/4048312#.YWLO29VBypq, Virufy: https://github.com/virufy/virufy-data. NoCoCoDa: Available from the corresponding author of [43] on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Sezer Ulukaya and Ahmet Alp Sarıca contributed equally to this work.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Sezer Ulukaya, Email: sezerulukaya@trakya.edu.tr.

Ahmet Alp Sarıca, Email: alpsarica@gmail.com.

Oğuzhan Erdem, Email: ogerdem@trakya.edu.tr.

Ali Karaali, Email: karaalia@tcd.ie.

References

- 1.WHO (2022) WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. COVID-19 Facts. https://COVID19.who.int/. Accessed 29 May 2022

- 2.Menni C, Sudre CH, Steves CJ, Ourselin S, Spector TD. Quantifying additional COVID-19 symptoms will save lives. Lancet. 2020;395(10241):e107–e108. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31281-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rothan HA, Byrareddy SN. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. J Autoimmun. 2020;109:102433. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Larsen JR, Martin MR, Martin JD, Kuhn P, Hicks JB. Modeling the onset of symptoms of COVID-19. Front Public Health. 2020;8:473. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deshpande G, Batliner A, Schuller BW. AI-based human audio processing for COVID-19: a comprehensive overview. Pattern Recogn. 2022;122:108289. doi: 10.1016/j.patcog.2021.108289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiziloluk S, Sert E (2022) COVID-CCD-Net: COVID-19 and colon cancer diagnosis system with optimized CNN hyperparameters using gradient-based optimizer. Med Biol Eng Comput :1–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Amyar A, Modzelewski R, Li H, Ruan S. Multi-task deep learning based CT imaging analysis for COVID-19 pneumonia: classification and segmentation. Comput Biol Med. 2020;126:104037. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2020.104037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang S, et al. (2021) A deep learning algorithm using CT images to screen for corona virus disease (COVID-19). Eur Radiol :1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Narin A, Kaya C, Pamuk Z (2021) Automatic detection of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) using x-ray images and deep convolutional neural networks. Pattern Anal Appl :1–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Ilhan HO, Serbes G, Aydin N (2021) Decision and feature level fusion of deep features extracted from public COVID-19 data-sets. Appl Intell :1–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Brown C, et al. (2020) Exploring automatic diagnosis of COVID-19 from crowdsourced respiratory sound data, 3474–3484. 10.1145/3394486.3412865

- 12.Imran A, et al. AI4COVID-19: AI enabled preliminary diagnosis for COVID-19 from cough samples via an app. Inform Med Unlocked. 2020;20:100378. doi: 10.1016/j.imu.2020.100378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohammed EA, Keyhani M, Sanati-Nezhad A, Hejazi SH, Far BH. An ensemble learning approach to digital corona virus preliminary screening from cough sounds. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-95042-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xia T, et al. (2021) COVID-19 sounds: A large-scale audio dataset for digital respiratory screening

- 15.Mallol-Ragolta A, Cuesta H, Gómez, E, Schuller BW (2021) Cough-based COVID-19 detection with contextual attention convolutional neural networks and gender information. In: 22nd Annual Conference of the international speech communication association, INTERSPEECH 2021. http://dx.doi. org/10.21437/Interspeech.2021-1052, pp 4236–4240

- 16.Dash TK, Mishra S, Panda G, Satapathy SC. Detection of COVID-19 from speech signal using bio-inspired based cepstral features. Pattern Recogn. 2021;117:107999. doi: 10.1016/j.patcog.2021.107999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laguarta J, Hueto F, Subirana B. COVID-19 artificial intelligence diagnosis using only cough recordings. IEEE Open J Eng Med Biol. 2020;1:275–281. doi: 10.1109/OJEMB.2020.3026928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soltanian M, Borna K. COVID-19 recognition from cough sounds using lightweight separable-quadratic convolutional network. Biomed Sig Process Control. 2022;72:103333. doi: 10.1016/j.bspc.2021.103333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coppock H, et al. (2021) End-to-end convolutional neural network enables COVID-19 detection from breath and cough audio: a pilot study. BMJ Innovations 7(2) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Suppakitjanusant P, et al. Identifying individuals with recent COVID-19 through voice classification using deep learning. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1–7. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-98742-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chaudhari G, et al. (2020) Virufy: global applicability of crowdsourced and clinical datasets for AI detection of COVID-19 from cough. arXiv:2011.13320

- 22.Akgün, D. Kabakuş, AT. Şentürk, ZK. Şentürk, A. Küçükkülahlı, E A transfer learning-based deep learning approach for automated COVID-19 diagnosis with audio data. Turk J Electr Eng Comput Sci. 2021;29(8):2807–2823. doi: 10.3906/elk-2105-64. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shuja J, Alanazi E, Alasmary W, Alashaikh A. COVID-19 open source data sets: a comprehensive survey. Appl Intell. 2021;51(3):1296–1325. doi: 10.1007/s10489-020-01862-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis S, Mermelstein P. Comparison of parametric representations for monosyllabic word recognition in continuously spoken sentences. IEEE Trans Acoust Speech Sig Process. 1980;28(4):357–366. doi: 10.1109/TASSP.1980.1163420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sahidullah M, Saha G. Design, analysis and experimental evaluation of block based transformation in MFCC computation for speaker recognition. Speech Comm. 2012;54(4):543–565. doi: 10.1016/j.specom.2011.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghahramani P, Hadian H, Povey D, Hermansky H, Khudanpur S (2020) An Alternative to MFCCs for ASR,1664–1667. 10.21437/Interspeech.2020-2690

- 27.McFee B, et al. (2015) librosa: Audio and music signal analysis in python. In: Proceedings of the 14th python in science conference. 10.5281/zenodo.18369, vol 8, pp 18–25

- 28.Arias-Vergara T, et al. Multi-channel spectrograms for speech processing applications using deep learning methods. Pattern Anal Appl. 2021;24(2):423–431. doi: 10.1007/s10044-020-00921-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meghanani A, Anoop CS, Ramakrishnan AG (2021) An exploration of log-mel spectrogram and MFCC features for Alzheimer’s dementia recognition from spontaneous speech. In: 2021 IEEE spoken language technology workshop (SLT). 10.1109/SLT48900.2021.9383491, pp 670–677

- 30.Yu Y-B, et al. (2021) Attentive deep CNN for speaker verification. In: 12th international conference on signal processing systems. 10.1117/12.2581351, vol 11719. International Society for Optics and Photonics, p 117190U

- 31.Chen X, Zahorian SA (2021) Improving speaker verification in reverberant environments. In: ICASSP 2021-2021 IEEE international conference on acoustics, speech and signal processing (ICASSP). 10.1109/ICASSP39728.2021.9413731. IEEE, pp 5854–5858

- 32.Michelsanti D, et al. An overview of deep-learning-based audio-visual speech enhancement and separation. IEEE/ACM Trans Audio Speech Lang Process. 2021;29:1368–1396. doi: 10.1109/TASLP.2021.3066303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hasannezhad M, Yu H, Zhu W-P, Champagne B. PACDNN: a phase-aware composite deep neural network for speech enhancement. Speech Comm. 2022;136:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.specom.2021.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simonyan K, Zisserman A (2015) Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. In: Bengio Y, LeCun Y (eds) 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2015, San Diego, CA, USA, May 7-9, 2015 Conference Track Proceedings. 1409.1556

- 35.Krizhevsky A, Sutskever I, Hinton GE. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2012;25:1097–1105. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hershey S, et al. (2017) CNN architectures for large-scale audio classification. In: 2017 IEEE international conference on acoustics, speech and signal processing (ICASSP). 10.1109/ICASSP.2017.7952132. IEEE, pp 131–135

- 37.Mueller M, Arzt A, Balke S, Dorfer M, Widmer G. Cross-modal music retrieval and applications: an overview of key methodologies. IEEE Sig Process Mag. 2019;36(1):52–62. doi: 10.1109/MSP.2018.2868887. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Birajdar GK, Patil MD. Speech/music classification using visual and spectral chromagram features. J Ambient Intell Humaniz Comput. 2020;11(1):329–347. doi: 10.1007/s12652-019-01303-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu Y, Nakamura E, Yoshii K (2020) A variational autoencoder for joint chord and key estimation from audio chromagrams. In: 2020 asia-pacific signal and information processing association annual summit and conference (APSIPA ASC), pp 500– 506

- 40.Korvel G, Treigys P, Tamulevicus G, Bernataviciene J, Kostek B. Analysis of 2D feature spaces for deep learning-based speech recognition. J Audio Eng Soc. 2018;66(12):1072–1081. doi: 10.17743/jaes.2018.0066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Orlandic L, Teijeiro T, Atienza D. The COUGHVID crowdsourcing dataset, a corpus for the study of large-scale cough analysis algorithms. Sci Data. 2021;8(1):1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41597-021-00937-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharma N, et al. (2020) Coswara-A database of breathing, cough, and voice sounds for COVID-19 diagnosis. In: Proceedings of the Annual Conference Of The International Speech Communication Association (INTERSPEECH), pp 4811–4815

- 43.Cohen-McFarlane M, Goubran R, Knoefel F. Novel coronavirus cough database: Nococoda. IEEE Access. 2020;8:154087–154094. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3018028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schuller BW. Intelligent audio analysis. New York: Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peeters G (2006) Musical key estimation of audio signal based on hidden Markov modeling of chroma vectors. In: Proceedings of the international conference on digital audio effects (DAFx). Citeseer, pp 127–131

- 46.He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J (2016) Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: 2016 IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (CVPR). 10.1109/CVPR.2016.90, pp 770–778

- 47.Tan M, Le Q (2019) EfficientNet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In: International conference on machine learning. Available from https://proceedings.mlr.press/v97/tan19a.html. PMLR, pp 6105–6114

- 48.Sandler M, Howard A, Zhu M, Zhmoginov A, Chen L-C (2018) MobileNetV2: inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 10.1109/CVPR.2018.00474, pp 4510–4520

- 49.Chollet F (2017) Xception: Deep learning with depthwise separable convolutions. In: Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 10.1109/CVPR.2017.195, pp 1251–1258

- 50.Liu R, et al. Positive rate of RT-PCR detection of SARS-CoV-2 infection in 4880 cases from one hospital in Wuhan, China, from Jan to Feb 2020. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;505:172–175. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fang Y, et al. Sensitivity of chest CT for COVID-19: comparison to RT-PCR. Radiology. 2020;296(2):E115–E117. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xie C, et al. Comparison of different samples for 2019 novel coronavirus detection by nucleic acid amplification tests. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;93:264–267. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.02.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen J, Li K, Zhang Z, Li K, Yu PS. A survey on applications of artificial intelligence in fighting against COVID-19. ACM Comput Surv (CSUR) 2021;54(8):1–32. doi: 10.1145/3465398. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xie X, et al. Chest CT for typical coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia: relationship to negative RT-PCR testing. Radiology. 2020;296(2):E41–E45. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ai T, et al. Correlation of chest CT and RT-PCR testing for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: a report of 1014 cases. Radiology. 2020;296(2):E32–E40. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang W, Yan F. Patients with RT-PCR-confirmed COVID-19 and normal chest CT. Radiology. 2020;295(2):E3–E3. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Adams HJ, Kwee TC, Kwee RM. Coronavirus disease 2019 and chest CT: do not put the sensitivity value in the isolation room and look beyond the numbers. Radiology. 2020;297(1):E236–E237. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Deng X et al (2022) Building a predictive model to identify clinical indicators for COVID-19 using machine learning method. Med Biol Eng Comput :1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Sarwan A, Zhou Y, Patterson M (2022) Efficient analysis of COVID-19 clinical data using machine learning models. Medical & Biological Engineering & Computing [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Coppock H, Jones L, Kiskin I, Schuller B. COVID-19 detection from audio: seven grains of salt. Lancet Digit Health. 2021;3(9):e537–e538. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(21)00141-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Senturk ZK. Early diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease using machine learning algorithms. Med Hypotheses. 2020;138:109603. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.109603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tsanas A, Little MA, Ramig LO. Remote assessment of Parkinson’s disease symptom severity using the simulated cellular mobile telephone network. IEEE Access. 2021;9:11024–11036. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3050524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sattar F (2021) A fully-automated method to evaluate coronavirus disease progression with COVID-19 cough sounds using minimal phase information. Ann Biomed Eng :1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Şen, SS. Cicioğlu, M. Çalhan, A IoT-based GPS assisted surveillance system with inter-WBAN geographic routing for pandemic situations. J Biomed Inform. 2021;116:103731. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2021.103731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bayrakdar ME. Priority based health data monitoring with IEEE 802.11 AF technology in wireless medical sensor networks. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2019;57(12):2757–2769. doi: 10.1007/s11517-019-02060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the following repositories; Coswara: https://github.com/iiscleap/Coswara-Data, Coughvid: https://zenodo.org/record/4048312#.YWLO29VBypq, Virufy: https://github.com/virufy/virufy-data. NoCoCoDa: Available from the corresponding author of [43] on reasonable request.