Abstract

To identify cis-acting genetic elements essential for mammalian chromosomal DNA replication, a 5.8-kb fragment from the Chinese hamster dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) locus containing the origin beta (ori-β) initiation region was stably transfected into random ectopic chromosomal locations in a hamster cell line lacking the endogenous DHFR locus. Initiation at ectopic ori-β in uncloned pools of transfected cells was measured using a competitive PCR-based nascent strand abundance assay and shown to mimic that at the endogenous ori-β region in Chinese hamster ovary K1 cells. Initiation activity of three ectopic ori-β deletion mutants was reduced, while the activity of another deletion mutant was enhanced. The results suggest that a 5.8-kb fragment of the DHFR ori-β region is sufficient to direct initiation and that specific DNA sequences in the ori-β region are required for efficient initiation activity.

Initiation of DNA replication in Escherichia coli, mammalian viruses, and the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (23, 67) is controlled primarily by trans-acting initiator proteins that interact with cis-acting DNA sequence elements (the replicators) (46). In these simple replicons, the cis-acting element consists of an essential core sequence, containing initiator protein binding sites and easily unwound sequences (DNA unwinding elements [DUEs]), and auxiliary sequences which enhance the efficiency of replication initiation (23, 67). In S. cerevisiae, the initiation of replication requires an autonomously replicating sequence (ARS) element in cis and occurs within a region flanked by a DUE and the binding sites for the origin recognition complex (ORC) and other initiator proteins (10). The initiation site for leading-strand synthesis appears to be restricted to a single nucleotide in a chromosomal ARS element (11). Replication initiation in fission yeast is also controlled by the sequence-specific recognition of a cis-acting replicator by ORC and associated initiator proteins, but the fission yeast replicators are larger than those of its budding yeast counterpart (18, 19, 50, 66, 68, 69). Initiation activity of yeast ARS elements in chromosomal DNA depends not only on specific DNA sequences in the ARS but also on chromatin structure and chromosomal position (13, 34, 36, 51, 63, 67, 70, 79, 88).

Extensive mapping of replication start sites in mammalian chromosomes has revealed that replication at most but not all loci begins at a few high-frequency start sites contained within a broad zone of initiation (4, 37, 59, 62, 82, 83; see also studies reviewed in references 12, 24, and 40). One of the most thoroughly mapped high-frequency initiation regions (IRs) in mammalian chromosomes is the region downstream from the dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) gene in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells (Fig. 1A). This region contains a 55-kb zone of delocalized origin activity containing three preferred start sites: origin beta (ori-β), centered approximately 17 kb downstream from the DHFR gene; ori-β′ just downstream from ori-β; and ori-γ, located 23 kb further downstream (5, 14, 42, 43, 44, 52, 55, 57, 71, 85, 86, 89).

FIG. 1.

(A) Features of the endogenous DHFR ori-β IR. Preferred start sites of DNA replication—the ori-β, ori-β′, and ori-γ sites; a 55-kb initiation zone (shaded area) between the DHFR- and 2BE2121-coding sequences; and matrix-attached regions (MARs, stippled boxes)—are indicated (5, 14, 42, 43, 44, 52, 55, 57, 71, 85, 86, 89). The 5.8-kb fragment of the DHFR ori-β region (pMCD), extending from the BamHI to the KpnI recognition sequences, is indicated. Arrows denote the positions of the primers used in the competitive PCR assay for origin function and correspond to primer pairs used in previous DHFR ori-β mapping studies (71). (B) Strategy for quantitating initiation occurring in exogenous DHFR ori-β fragments in ectopic chromosomal locations. A 5.8-kb wild-type or mutated DHFR ori-β fragment was coelectroporated with a neomycin resistance gene into the DR12 cell line, a CHO derivative containing a 150-kb deletion encompassing the entire DHFR locus (47). After selection with G418, total DNA was isolated, heat denatured, and size fractionated on a 5 to 30% linear neutral sucrose gradient. The fraction containing single-stranded DNA with a length of 1 to 2 kb, representing nascent DNA, was isolated, and the abundance of ori-β target sequences contained in the fraction was quantitated by competitive PCR.

Despite the progress in mapping initiation sites, the specific genetic elements necessary to direct initiation of mammalian DNA replication remain poorly understood. The existence of preferred IRs raises the question of whether specific DNA sequences within or neighboring an IR may direct initiation of replication at the IR or even in a broad zone more distant from the preferred IR. Several lines of evidence are consistent with the notion that sequences neighboring a preferred IR may constitute a mammalian replicator element. In the human lamin B2 IR, DNase I footprinting has revealed that a specific sequence is protected in a cell cycle-dependent manner, suggesting that it may be a binding site for an initiator protein complex (1, 29, 39). Moreover, replication at the lamin B2 origin was shown to initiate within a 3-bp sequence that overlaps the footprint region (2). A site hypersensitive to micrococcal nuclease has been mapped in the DHFR ori-β IR locus (72), and there is preliminary evidence that hamster ORC2, a subunit of the ORC complex, binds within the DHFR ori-β IR (cited in reference 12). Recent genetic analysis of the human β-globin (4) and the human c-myc (62) IRs at an ectopic chromosomal locus demonstrated that a defined sequence of 2 to 8 kb can be sufficient to direct initiation in the ectopic locus. Furthermore, the putative c-myc replicator even induced new start sites in the flanking chromosomal DNA (62). Taken together, these studies suggest that initiation of chromosomal DNA replication in mammalian cells may be directed by specific cis-acting DNA sequence elements that constitute a replicator similar to those characterized in yeasts.

The complex organization of the DHFR initiation zone raises the question of whether it differs structurally from the putative replicators containing the c-myc, lamin B2, and β-globin IRs. For example, the cluster of preferred IRs may represent a novel replicator organization with multiple elements dispersed throughout the 55-kb initiation zone that are interdependent and cannot function independently as replicators. Alternatively, the three preferred start sites, ori-β, ori-β′, and ori-γ, within the delocalized initiation zone could represent separable but redundant genetic elements that ensure the faithful replication of this locus (72). In this latter case, the regions surrounding each of the three start sites might serve as individual replicators able to direct initiation when placed at an ectopic chromosomal location.

To address the question of whether a defined DNA sequence encompassing DHFR ori-β can direct initiation of DNA replication in chromosomal DNA, we have generated stably transfected cells containing the exogenous ori-β IR in random ectopic chromosomal locations and measured ori-β initiation activity by using a competitive PCR-based nascent strand abundance assay. The results presented here demonstrate that a 5.8-kb sequence containing the ori-β IR is sufficient to direct initiation in multiple ectopic chromosomal sites and that specific DNA sequences within and flanking the IR are essential for efficient initiation activity at the DHFR ori-β region.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Diploid Chinese hamster ovary K1 (CHOK1) cells and DR12 cells—CHOK1 derivatives containing 150-kb deletions of the entire DHFR locus (47)—were grown in Ham's F12 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Life Technologies, Rockville, Md.) at 37°C and 4% CO2.

Plasmid constructs.

The plasmid pMCD, containing the 5.8-kb BamHI-KpnI fragment, nucleotides (nts) 1 through 5793 (GenBank accession no. Y09885) of the DHFR ori-β locus in the vector pUC19 (90), was the kind gift of N. H. Heintz (16). Deletion mutant pAKO was generated by digestion of pMCD with ApaI (nt position 1127), removal of overhanging ends using T4 DNA polymerase, and religation. Mutant pMCDΔAT was created by partial digestion of pMCD with SphI (nt position 2163), followed by complete digestion with EcoRV (nt position 2507), releasing a 344-bp fragment; the other fragment was then blunt ended and religated. The mutant pMCDΔDNR was created by partial digestion of pMCD with XbaI (nt position 4454) followed by complete digestion with NheI (nt position 4219), releasing a 235-bp fragment; the remaining fragment was blunt ended and religated. Mutant pMCDΔTR was created by using PCR and mutagenic primers (5′GACAAAAACAATCGATAAATAAG and 5′CTTATTTATCGATTGTTTTTGTC) to insert a ClaI restriction site at nt position 686, relative to the BamHI site. The resulting plasmid was partially digested with PvuII (nt position 949), followed by complete digestion with ClaI, releasing a 263-bp fragment; the remaining fragment was blunt ended and religated. The pSV2neo plasmid contains a full-length neomycin resistance gene (Clontech Laboratories, Inc., Palo Alto, Calif.). Plasmid K126 contains the 3-kb BamHI-XbaI fragment of the DHFR ori-β region in the vector pBluescript. Plasmid Mut8-2 contains the SacI/AccI fragment of the DHFR ori-β region in the vector pBluescript.

Transfection.

The BamHI-KpnI ori-β fragment cloned in pUC19 was linearized with AatII to generate the 5.8-kb DHFR insert flanked by 1,271 and 1,401 bp of vector DNA. Four micrograms of the digest mixed in a 3:1 molar ratio with PvuI-linearized pSV2neo DNA was electroporated into 5 × 106 DR12 cells using a BioRad Gene Pulser at 360 V and 600 μF. Cells were plated in 75-cm2 tissue culture flasks. After 24 h, the medium was replaced with Ham's F12 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 0.5 mg of G418 (Life Technologies) per ml. After 4 weeks of growth under selection, exponentially proliferating cells from four 150-cm2 flasks, grown to 70% confluency, were harvested, and total DNA was isolated and analyzed as described below. Under these transfection conditions, the average number of copies of exogenous DHFR ori-β integrated per cell in pools of cells was highly reproducible (see below). Single cell clones were isolated through serial dilution into a 96-well plate and expanded under drug selection for 14 weeks to four 150-cm2 flasks. Isolation of total genomic DNA and its analysis were carried out as described below for pools of transfected cells.

Quantitation of stably transfected DNA.

The integration of ectopic DHFR ori-β fragments into DR12 genomic DNA was monitored by PCR analysis of DNA from transfected cells. PCR amplification was carried out with primer set 2 (Table 1) and with 5 ng of total genomic DNA, isolated from transfected DR12 cells or from CHOK1 cells, in a Perkin-Elmer 4800 thermal cycler (35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 56°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s). Amplification products were resolved by 7% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), stained with ethidium bromide, and quantified by densitometry (IPLab Gel software; Signal Analytics Corp., Vienna, Va.). The ratio of the exogenous DHFR ori-β products to the endogenous CHOK1 ori-β products, termed the integration ratio, was consistently close to 1 after 4 weeks of drug selection. Thus, although the integration ratio is not used to calculate the initiation activity, the copy number of integrated pMCD fragments in DR12 cells, on average, mimics the copy number of the endogenous DHFR ori-β in CHOK1 cells. In some experiments, the PCR analysis was carried out in parallel with primer pairs 2 and 3; the resulting ratios did not differ significantly.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primer sequences and positions relative to the BamHI site of pMCD

| Primer | Sequence 5′–3′ | Positiona |

|---|---|---|

| 8SX | CTCTCTCATAGTTCTCAGGC | 470–489 |

| 8DX | GTCCTCGGTATTAGTTCTCC | 651–670 |

| 2SX | GTCCCTGCCTCAAAACACAA | 1070–1089 |

| 2DX | CCTTCATGCTGACATTTGTC | 1329–1348 |

| 6SX | AACTGGCTTCCCAAGAAATT | 1517–1536 |

| 6DX | AACCTCTGAACTGTAAGCTG | 1666–1685 |

| 3SX | GGACACTAAGTCTAGGTACTACA | 3882–3904 |

| 3DX | GCTGGGATAAGTTGAAATCC | 4121–4140 |

| 8SXCOMb | GTCGACGGATCCCTGCAGGTCATTCATCAAGCTGGAAAGC | 529–548 |

| 8DXCOM | ACCTGCAGGGATCCGTCGACTCCATGGCAGTCTTCACACT | 549–569 |

| 2SXCOM | GTCGACGGATCCCTGCAGGTAAGGAAGGAAAGAAAGGGCCC | 1126–1146 |

| 2DXCOM | ACCTGCAGGGATCCGTCGACCTCAGTGAGTCCACTTGCTTT | 1147–1168 |

| 6SXCOM | GTCGACGGATCCCTGCAGGTATAGAAACCCCAGCTAAGAC | 1587–1606 |

| 6DXCOM | ACCTGCAGGGATCCGTCGACTGCTGTGAAGAGACACCATG | 1607–1626 |

| 3SXCOM | GTCGACGGATCCCTGCAGGTTAGGAAACTGAGATGCCAGG | 3992–4010 |

| 3DXCOM | ACCTGCAGGGATCCGTCGACAGGACTCAGCTCTTACTAAC | 4011–4031 |

nt position relative to the BamHI recognition sequence in the DHFR ori-β fragment pMCD, defined as position 1 (GenBank accession no. Y09885).

Underlined sequence is the 5′ tail of the PCR primer which gave rise to the 20-bp insertion in the competitor plasmids (see Materials and Methods for construction).

The structure of the integrated DHFR ori-β fragment was confirmed through PCR analysis of the integrated DHFR ori-β fragment using six sets of PCR primers (FullF [5′-GCTATGACCATGATTACGCC] and 8DX, 8SX and 2DX, 2SX and 6DX, 6SX and 3ATR [5′-CAGGCCAGTGTTTAGATGCTGG], 3ATF [5′-GGGATTAAAGGCATGCACCACC] and 3DX, and 3SX and FullR [5′-GGTTTTCCCAGTCACGACG]) on 20 ng of pMCD plasmid DNA or 1 μl of the largest DNA fraction from the sucrose gradient containing pMCD-transfected DR12 cells. PCR amplification was carried out in a Perkin-Elmer 4800 thermal cycler (50 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 56°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 5 min). Amplification products were resolved by 7% PAGE, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized under UV light.

DNA isolation and gradient centrifugation.

Total genomic DNA was isolated from harvested cells according to the manufacturer's instructions (Nucleon II; Scotlabs). Five-hundred micrograms of resuspended total genomic DNA in 1 ml of TE (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0]–1 mM EDTA) was heat denatured at 100°C for 10 min, followed by a 10-min incubation in ice-water. DNA was loaded onto a 5 to 30% linear neutral sucrose gradient and centrifuged at 26,000 rpm (Sorvall AH-629 rotor) for 17 h at 20°C. Fractions of 1 ml each were collected, and the fraction enriched in nascent single-stranded DNA (ca. 1 to 2 kb in length) was dialyzed against TE and used as a template for PCR amplification. As size markers, 50 μg of pMUT8-2 digested with KpnI and NdeI to produce fragment sizes of 921 and 2,972 bp and 50 μg of pK126 digested with StuI and BgIII to produce fragment sizes of 1,636 and 4,338 bp were loaded on a sucrose gradient and run concurrently with each set of experiments. A 50-μl aliquot of each marker fraction was subjected to electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel at 200 mA for 2 h, and DNA was visualized by ethidium bromide staining. For control PCR, total genomic DNA was sheared to fragments 1 to 2 kb in size by sonication for 15 s at 25% power (250/450 Sonifier; Branson Ultrasonics Corp., Danbury, Conn.), heat denatured, and fractionated on a 5 to 30% linear neutral sucrose gradient as described above.

Construction of PCR competitive templates.

Competitors were constructed essentially as previously described (71). Briefly, PCR amplification was performed with pMCD template using the standard primer sets 8, 2, 6, and 3 and their corresponding competitor primer sets, as denoted by the suffix COM, which contain 20-bp insertions (Table 1). These PCR products were used as templates for another round of PCR amplification with the standard primer sets, resulting in PCR amplification products which were identical to their pMCD target sequence except for the 20-bp insertion. The mutated PCR amplification products were cloned into pMCD to create competitive templates for the PCR-based nascent strand abundance assay.

PCR-based nascent strand abundance assay.

The competitive PCR nascent strand abundance assay was performed using primer sets 8, 2, 6, and 3 (31, 53, 71; Table 1) essentially as previously described. Each PCR mixture included the corresponding competitor plasmid DNA, which had been precalibrated against 20 ng of total genomic DNA from asynchronously growing CHOK1 cells. Assuming 3 × 109 bp per haploid genome, 20 ng of genomic DNA would correspond to 6,000 molecules of competitor (31). Amplification reactions with each primer set contained increasing amounts of the size-fractionated nascent DNA and the precalibrated amount of the corresponding competitor DNA. PCR was carried out in a Perkin-Elmer 4800 thermal cycler (50 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 56°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s). Similar results were obtained using 35 cycles with the same program (data not shown), consistent with the expectation that competitive PCR should be independent of cycle number (31). Amplification products were resolved by 7% PAGE, stained with ethidium bromide, and quantified by densitometry (IPLab Gel software; Signal Analytics Corp.). The intensity of the signal was linearly proportional to the amount of stained DNA under the conditions used.

The ratio of PCR amplification products from nascent genomic template relative to the PCR amplification products from the competitive template (nascent/competitor) was plotted on the x axis against the volume of input nascent genomic DNA template on the y axis. Linear regression analyses were performed on the data (KaleidaGraph software; Synergy Software, Reading, Pa.), resulting in correlation coefficients greater than 0.97. In order for the calculations to be accurate, the correlation coefficient must be at least 0.97, and the equivalence point must be contained within the volumes used in the PCR analysis. The slope of this linear regression, along with the known molecules of calibrated competitor per microliter, was used to calculate the molecules of nascent DNA per microliter for each primer set. Since the number of base pairs in each amplification product is known, the grams per mole of target DNA can be calculated using the conversion of 660 g/mol of base pairs. By converting the molecules of nascent DNA target per microliter for each primer set to moles per microliter using Avogadro's number and multiplying this by the grams of target DNA per mole, the DNA concentration of nascent DNA target for each primer pair can be calculated. The concentration of target molecules for each primer pair can then be expressed relative to the concentration of total DNA in the nascent fraction, as determined by absorbance at 260 nm (termed abundance). To facilitate comparison between separate experiments, the abundance of target sequences for each primer pair was expressed relative to the abundance of the target sequences for the distal pp3 in the same experiment (defined as 1), and this ratio was termed initiation activity.

RESULTS

A DHFR ori-β fragment functions efficiently as an origin in ectopic chromosomal locations.

Given that DNA fragments containing the β-globin (4) and the c-myc (62) IRs supported efficient DNA replication at ectopic chromosomal locations, we asked whether a small DNA fragment containing DHFR ori-β and flanking DNA but lacking the downstream ori-β′ and ori-γ regions would direct initiation of DNA replication when located at ectopic chromosomal sites. To address this question, we chose the experimental strategy diagramed in Fig. 1B. A 5.8-kb fragment containing the ori-β IR (pMCD [16]) but not the ori-β′, ori-γ, or matrix attachment regions or the DHFR coding sequences was cotransfected by electroporation with an unlinked neomycin resistance marker into DR12 cells, a CHOK1-derived line lacking both DHFR loci (47). We chose an unlinked resistance marker to ensure that any initiation of DNA replication occurring within the ori-β fragment would not be influenced by transcription of the neomycin gene in the same construct. To facilitate the stable integration of the DNA fragments into the chromosomal DNA, plasmids containing the ori-β DNA fragment were first linearized in the vector portion by restriction endonuclease digestion. Under these conditions, integration of exogenous DNA fragments has been reported to be random and without significant loss of DNA sequences at the ends of the fragment (35, 77).

As a strategy to minimize potential position effects of the integration site, nascent DNA was isolated from pools of uncloned transfectants. We reasoned that if position effects caused by flanking DNA at the integration sites of the ectopic chromosomal ori-β fragments occurred, they might be masked in pools of uncloned cells, thereby enhancing the reproducibility of the assay. Total DNA was heat denatured and size fractionated by centrifugation. The fraction containing single-stranded DNA (ca. 1 to 2 kb in length) was used as a template for PCR amplification in competitive PCR-based nascent strand abundance assays with four sets of primers (Fig. 1A). Three of the selected primer sets (pp8, pp2, and pp6) were located within and directly flanking the IR, as determined by previous mapping studies (52, 57, 71). A fourth primer set (pp3), located distal to the IR and outside of the 1- to 2-kb nascent DNA strand template, was used to normalize the data to an outlying non-origin primer set and facilitate comparison between separate experiments. Since the 5.8-kb DNA fragment integrates randomly into the genome, it is important to normalize to a primer set contained within the fragment. In this way, if the initiation activity of the construct is affected by neighboring chromatin, then the entire fragment will be affected, including all primer sites. Hence, the initiation activity of the ectopic IR was expressed as the ratio of the IR target sequences over the non-IR sequence in the 1- to 2-kb single-stranded DNA fraction.

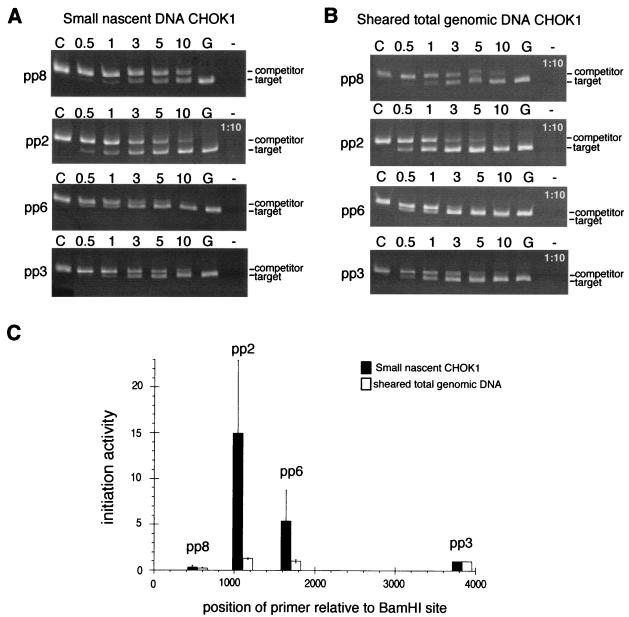

To first validate our competitive PCR-based nascent strand abundance assay, we used it to confirm the preferential initiation at the endogenous DHFR ori-β region in CHOK1 cells. DNA sequences that are close to the ori-β IR are expected to be enriched in the short single-stranded DNA fraction, compared to more distal DNA sequences which are expected to be represented only in longer nascent DNA strands. Consistent with previous studies (52, 57, 71), the amount of nascent DNA template required to amplify an amount of target DNA equivalent to the precalibrated competitor DNA with primer pair 2 (pp2), centered over the previously mapped ori-β IR, was smaller than with primer pairs 8, 6, and 3, which were more distant from the IR (Fig. 2A). To better illustrate the differences among the 4 sets of primers in amplification of the genomic target, the gels shown in Fig. 2A are from a single experiment using equal volumes of the nascent DNA template fraction, except for a 1:10 dilution of the fraction used for pp2. When the equivalence point was not reached within the tested volumes of the nascent DNA fraction, the experiment was repeated using either increased or decreased amounts of the nascent fraction until the equivalence point was included (data not shown). Quantitative evaluation of one such experiment is shown in Table 2. The abundance of pp2 target DNA sequences was more than 10-fold higher than the abundance of target sequences for the outlying pp3 in the nascent CHOK1 DNA fraction. To compare the abundance of pp2 target sequence in nascent CHOK1 DNA among multiple independent experiments, this abundance was expressed relative to the abundance of pp3 sequences in each experiment to give initiation activity. The average initiation activity from five independent experiments with CHOK1 cells is shown in Fig. 2C (black bars). Consistent with previous studies (52, 57, 71), the initiation activity centered over the previously mapped IR in the endogenous DHFR ori-β region was strongly enhanced compared to that in the flanking sequences (Fig. 2C, black bars).

FIG. 2.

Initiation of DNA replication at the endogenous DHFR ori-β site in asynchronous CHOK1 cells. (A) PCR amplifications were performed with each of the four primer pairs and with size-fractionated nascent DNA template from asynchronous CHOK1 cells in the presence of a precalibrated amount of the corresponding competitor DNA. Amplification products were analyzed by PAGE and ethidium bromide staining. Control lanes: C, competitor template only; G, nascent genomic DNA template only; −, no template. Numbers above each lane represent the volume in microliters of nascent DNA added to the PCR mixture. Amplification reactions with pp2 used a 1:10 dilution of the nascent DNA. (B) PCRs were performed and analyzed as in panel A, except that the template was a 1:10 dilution of sheared, denatured total genomic CHOK1 DNA 1 to 2 kb in length. (C) Amplification products generated with either nascent DNA from asynchronous CHOK1 cells (black bars) or sheared total genomic DNA from asynchronous CHOK1 cells (white bars) were quantitatively evaluated for five independent experiments with each type of template. As a measure of initiation activity, the abundance of each target sequence in nascent genomic DNA was normalized to the abundance of pp3 target sequences in the corresponding experiment, which was set equal to 1 (see example in Table 2), and the average of five experiments is shown. Bars indicate the standard error of the mean (SEM).

TABLE 2.

Abundance of DHFR ori-β target sequences in nascent DNAa

| DNA source | Abundanceb of DHFR ori-β target sequences (initiation activityc) with primer pair:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pp8 | pp2 | pp6 | pp3 | |

| CHOK1 | 8.49 × 10−8 (0.4) | 2.80 × 10−6 (12.8) | 3.65 × 10−7 (1.7) | 2.18 × 10−7 (1.0) |

| pMCD pool | 1.32 × 10−7 (1.3) | 2.59 × 10−6 (25.4) | 6.63 × 10−7 (6.5) | 1.02 × 10−7 (1.0) |

| Total sheared DNA | 3.45 × 10−7 (0.3) | 1.37 × 10−6 (1.3) | 1.03 × 10−6 (1.0) | 1.06 ×10−6 (1.0) |

Values in the table are from a typical experiment.

Abundance was calculated as described in Materials and Methods.

Initiation activity was calculated as described in Materials and Methods.

To establish a baseline or background value for comparison with nascent strand abundance data, the experiment was repeated under identical conditions, except that total CHOK1 DNA, isolated from asynchronously growing cells, was sheared to 1- to 2-kb fragments, heat denatured, and size fractionated. The fraction containing the sheared, single-stranded DNA of 1 to 2 kb in size was used as the template in competitive PCR assays. In total genomic DNA, the target sequences for each primer pair should be essentially equally represented, and thus, the amounts of amplification product generated with each primer pair should be similar. Indeed, the amounts of amplified DNA were similar with three of the four primer pairs and somewhat reduced for pp8 compared to the other primer pairs (Fig. 2B; Table 2). Comparison of these results with the enhanced abundance of pp2, pp6, and pp8 target sequences in the nascent DNA fraction from asynchronous CHOK1 cells indicated that the peak of initiation activity depended on the enrichment for nascent DNA template and did not arise through differences between primers in amplification efficiency or calibration error (Fig. 2C, compare black and white bars). Thus, the abundance of target sequences generated by amplification of the sheared-DNA control was considered to represent the empirical background activity of the assay system.

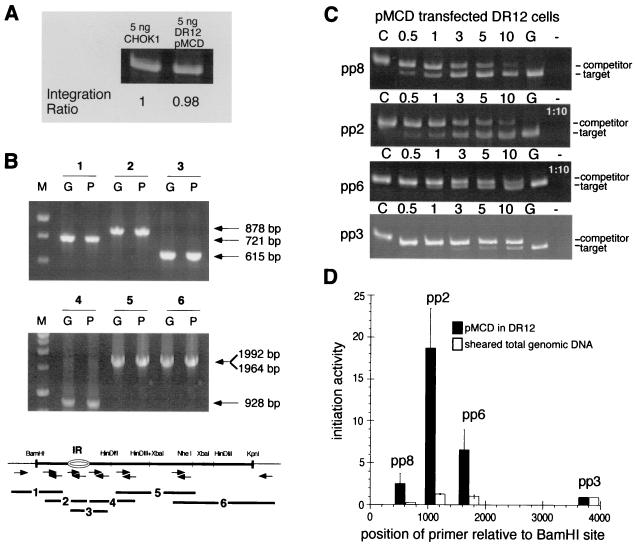

The PCR-based nascent strand abundance assay was then used to measure initiation activity at ectopic ori-β sequences in genomic DNA from pools of stably transfected DR12 cells. The transfection conditions were chosen so that the average copy number of ectopic ori-β fragments per cell in the pool of cells would mimic that of the endogenous ori-β in CHOK1 DNA. To confirm this, total genomic DNA isolated from uncloned drug-resistant pools of DR12 cells was used as a template for PCR amplification. For comparison, an equal amount of total genomic DNA isolated from CHOK1 cells was used as a template in a parallel amplification. The amplification products of both reactions were visualized by PAGE and ethidium bromide staining. Amounts of amplification product obtained with both samples were quantitated and found to be very similar, implying that the average copy number of ori-β per transfected cell in the pool was close to that of the endogenous ori-β in CHOK1 cells (Fig. 3A). However, it should be noted that the determination of the initiation activity of the transfected DHFR ori-β fragments does not depend on this approximate copy number (see Materials and Methods).

FIG. 3.

Initiation of DNA replication in the exogenous 5.8-kb ori-β fragment in DR12 cells. (A) The integrated exogenous DHFR ori-β fragment in 5 ng of DNA from uncloned pools of DR12 cells and the endogenous ori-β in 5 ng of CHOK1 DNA were amplified by PCR. The ratio of the amplification products in DR12 relative to those of endogenous ori-β in CHOK1 is indicated, and this ratio suggests that the copy number of exogenous ori-β fragments present in the pool of transfectants mimics that of the endogenous locus in CHOK1. (B) The structure of the integrated DHFR ori-β fragments in DR12 pools was determined by PCR amplification of either pMCD plasmid DNA (lanes P) or large single-stranded genomic DNA isolated from uncloned drug-resistant pools of pMCD-transfected DR12 cells (lanes G). Amplification reactions were performed with a panel of six primer sets spanning the 5.8-kb DHFR ori-β fragment and the flanking vector sequences (bottom). The resulting overlapping PCR amplification products, labeled 1 through 6, were analyzed by PAGE and ethidium bromide staining. M indicates a DNA size marker. The sizes of the resulting PCR amplification products are indicated. (C) PCR amplifications were performed with each of the four primer pairs and size-fractionated nascent DNA from asynchronous pMCD-transfected DR12 cells in the presence of a precalibrated amount of the corresponding competitor DNA. Amplification products were analyzed by PAGE and ethidium bromide staining. Control lanes: C, competitor template only; G, nascent genomic DNA template only; −, no template. Numbers above each lane represent the volume in microliters of nascent DNA added to the PCR mixture. Amplification reactions for pp2 and pp6 used a 1:10 dilution of the nascent DNA. (D) Amplification products generated with either nascent DNA from a pool of asynchronous pMCD-transfected DR12 cells (black bars) or sheared total genomic DNA from asynchronous pMCD-transfected DR12 cells (white bars) were quantitatively evaluated for seven independent transfection experiments. As a measure of initiation activity, the abundance of each target sequence in nascent genomic DNA was normalized to the abundance of pp3 target sequences in the corresponding experiment, which was set equal to 1 (see example in Table 2), and the average of the seven experiments is shown. Bars indicate the SEM.

To confirm that the structure of the integrated DHFR ori-β fragments was not rearranged or truncated, large single-stranded genomic DNA isolated from uncloned drug-resistant pools of pMCD-transfected DR12 cells was used as a template for PCR amplification. PCR amplification was carried out with a series of primer sets which would result in overlapping amplification products, extending from the flanking vector sequences on one side of the DHFR insert through the insert and into the flanking vector sequences on the other side of the insert (Fig. 3B). For comparison, pMCD plasmid DNA was used as a template in a parallel amplification. The amplification products of both reactions were visualized by PAGE and ethidium bromide staining. As seen in Fig. 3B, the amplification products generated from the transfected DNA (lanes G) were identical to those generated from the plasmid (lanes P). This result demonstrates that most of the integrated DNA fragments in DR12 pools were intact and had not undergone rearrangement during integration into the genome.

The abundance of ori-β target sequences in nascent DNA originating from the ectopic pMCD fragment in pools of transfected DR12 cells was then quantitated by competitive PCR. As seen in Fig. 3C, the amount of nascent DNA needed to amplify an amount of target DNA equivalent to the precalibrated competitor DNA with primer pair 2 was 10-fold less than with the flanking pp8 and the distal pp3, and severalfold less than with the flanking pp6. The abundance of target DNA for each primer pair in the nascent DNA fraction of the transfected cell pool was similar to that of the corresponding target DNA in nascent DNA from CHOK1 cells, as shown in the example in Table 2. Combining data from seven independent transfection experiments revealed that the target sequence for pp2 was significantly more abundant in the nascent DNA fraction than flanking target sequences, as would be expected for an active origin of DNA replication (Fig. 3D, black bars). The initiation activity of the ectopic ori-β IR was enhanced more than 10-fold relative to that in the distal pp3 sequences, closely resembling the results obtained with endogenous ori-β in CHOK1 cells (compare Fig. 3D and Fig. 2C). These results suggest that the 5.8-kb fragment of the DHFR ori-β region is sufficient to direct initiation in ectopic chromosomal locations and that the ectopic ori-β fragment functions with an efficiency comparable to that in the endogenous locus.

Ori-β functions in multiple ectopic locations, but exhibits some position effects.

Since chromosomal context is an important determinant of origin function in mammalian cells (3, 17, 27, 30, 33, 54, 56), the function of the exogenous ori-β IR may be sensitive to position effects that were not detected in the uncloned cell pools. If initiation activity of the 5.8-kb fragment is affected by chromosomal context, one might expect to find that initiation activity of the ectopic ori-β region would vary among clonal cell lines with different ori-β integration sites. To test for variability in initiation activity, six individual cell lines were cloned from a resistant-cell pool. To estimate the amount of integrated exogenous ori-β fragment in each clone, total genomic DNA isolated from each cell line was used as a template for PCR amplification with pp2. For comparison with the endogenous ori-β region, an equal amount of total genomic DNA isolated from CHOK1 cells was used as a template in a parallel amplification. The amplification of the exogenous ori-β DNA fragments differed slightly from clone to clone. Clones 1, 3, and 5 contained about the same copy number found for the endogenous ori-β region in CHOK1 DNA (Table 3). Clones 2, 4, and 6 had 20 to 30% less ori-β fragment, possibly suggesting some loss of ori-β sequences during expansion of the cloned cell lines.

TABLE 3.

Abundance of DHFR ori-β target DNA sequences in nascent DNAa

| DNA source | Copy no.d | Abundanceb of DHFR ori-β target DNA (initiation activityc) with primer pair:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pp8 | pp2 | pp6 | pp3 | ||

| Clone 1 | 1 | 2.04 × 10−7 (0.6) | 2.49 × 10−6 (6.9) | 1.41 × 10−7 (0.4) | 3.62 × 10−7 (1.0) |

| Clone 2 | 0.7 | 6.16 × 10−8 (0.9) | 5.03 × 10−7 (7.4) | 7.73 × 10−8 (1.1) | 6.79 × 10−8 (1.0) |

| Clone 3 | 0.9 | 8.11 × 10−8 (0.4) | 7.05 × 10−7 (3.5) | 7.09 × 10−8 (0.4) | 2.04 × 10−7 (1.0) |

| Clone 4 | 0.8 | 4.07 × 10−8 (0.4) | 6.04 × 10−7 (5.8) | 5.81 × 10−8 (0.5) | 1.05 × 10−7 (1.0) |

| Clone 5 | 1 | 3.03 × 10−8 (0.4) | 6.87 × 10−7 (9.4) | 8.50 × 10−8 (1.2) | 7.31 × 10−8 (1.0) |

| Clone 6 | 0.7 | 8.77 × 10−8 (0.6) | 3.88 × 10−7 (2.7) | 7.36 × 10−8 (0.5) | 1.45 × 10−7 (1.0) |

Values in the table are from a typical experiment with each clone.

Abundance was calculated as described in Materials and Methods.

Initiation activity was calculated as described in Materials and Methods.

Integration ratio of ori-β fragment relative to endogenous ori-β in CHOK1 cells.

The abundance of the exogenous ori-β IR target sequences in the nascent DNA fraction was quantitated for each cell clone, as shown in the examples in Table 3. For each cell clone, the abundance of target DNA for pp2 was higher than the abundance of target DNA for the flanking primer sets (Table 3). The relative initiation activity of the clones varied from 2.7- to 9.4-fold higher than in the distal pp3 sequences. Thus, the initiation activity of the clones ranged from just over background in two of the clones to about half the activity observed with uncloned pools of cells (compare Table 3 and Fig. 3D). The strong activity observed for the pMCD-transfected cell pools in repeated experiments (Fig. 3D) suggests that the variability from one clone to another was probably masked when pools of transfected cells containing many different integration sites were tested. Although the ectopic ori-β region was less active in each of the clones than in a typical experiment with an uncloned pool of transfectants (compare Tables 2 and 3), these results suggest that the exogenous 5.8-kb ori-β fragment was functional to some degree in six ectopic locations.

Specific cis-acting sequences are required for efficient DHFR ori-β initiation activity.

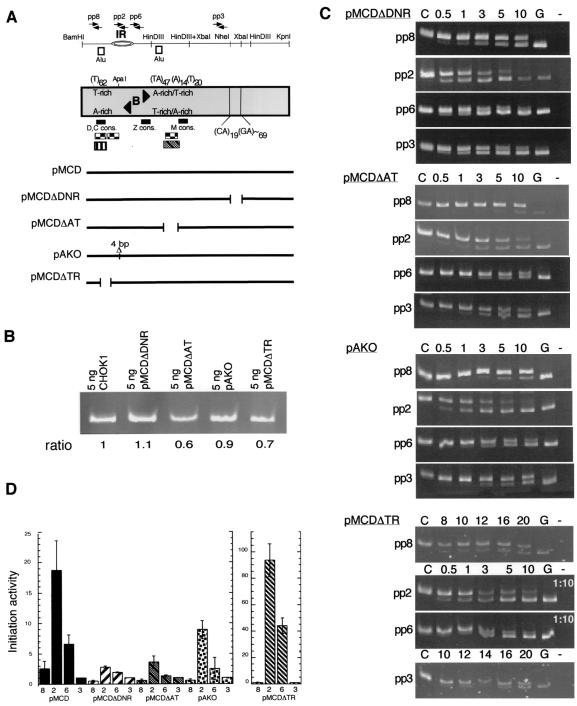

To assess whether specific DNA sequences within the 5.8-kb fragment of the ori-β region were required for efficient initiation at the preferred IR, several ori-β deletion mutants were constructed (Fig. 4A). The regions chosen for deletion contain DNA sequences that could be functionally important in mammalian origins based on their resemblance to DNA elements identified in other origins as discussed below. To permit comparison of the initiation activity of mutated fragments with that of the parental pMCD ori-β fragment, mutations that would delete primer sites for PCR amplification were avoided.

FIG. 4.

Initiation of DNA replication in wild-type and mutant exogenous ori-β DNA fragments. (A) Unusual DNA sequences in the 5.8-kb ori-β fragment and the location of the deletion mutants are indicated on the restriction map of the region. Positions of AluI repetitive elements (white boxes) and AT-rich sequences homologous to the S. pombe origin consensus motifs D, C, Z, and M (50) (small black boxes) are marked. AT-rich sequences homologous to a cell cycle-dependent DNase I genomic footprint in the human lamin B2 IR (1, 29, 39) (hatched box) and to the ORC-binding region in the Drosophila chorion ACE3 (6, 80) (checkered boxes) are noted. AT-rich sequences containing stably bent DNA (B) and binding sites for a zinc finger protein of unknown function, RIP60 (black arrowheads), are indicated (15, 16, 21, 45, 64). The position of a cell cycle-dependent nuclease-hypersensitive site (72) is indicated (striped box). (B) The integrated mutant DHFR ori-β fragments in 5 ng of DNA from uncloned pools of DR12 cells and the endogenous ori-β region in 5 ng of CHOK1 DNA were amplified by PCR and visualized by gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining. The ratio of the mutant amplification products in DR12 relative to those of the endogenous ori-β region in CHOK1 is indicated and suggests that the copy number of the exogenous ori-β region present in the pool of transfectants mimics that of the endogenous locus in CHOK1. (C) PCR amplifications were performed with each of the four primer pairs and size-fractionated nascent DNA from asynchronous mutant-transfected DR12 cells in the presence of a precalibrated amount of the corresponding competitor DNA. Amplification products were analyzed by PAGE and ethidium bromide staining. Control lanes: C, competitor template only; G, nascent genomic DNA template only; −, no template. Numbers above each lane represent the volume in microliters of nascent DNA added to the PCR mixture; note that for pMCDΔTR, the nascent genomic DNA was used at a 1:10 dilution with pp2 and pp6. (D) The abundance of nascent DNA from pools of mutant-transfected DR12 cells from three independent transfection experiments was quantitatively evaluated. As a measure of initiation activity, the abundance of each target sequence in nascent genomic DNA was normalized to the abundance of pp3 target sequences in the corresponding experiment, which was set equal to 1 (see Table 4 for a typical experiment), and the average of three experiments with each mutant is shown. For comparison, the average initiation activity measured with nascent DNA from a pool of asynchronous wild-type pMCD-transfected DR12 cells (Fig. 3D) is also shown. Bars indicate the SEM.

The downstream end of the 5.8-kb DHFR fragment contains a region of GA dinucleotide repeats which has been shown to adopt non-B-form DNA (16). Such dinucleotide repeats have been postulated to slow or arrest replication fork progression in rodent cells (7, 74). To determine whether the GA repeat element affected ori-β initiation activity, we created a construct which deleted the GA repeat (pMCDΔDNR [Fig. 4A]).

The 5.8-kb ori-β DNA fragment contains a central AT-rich region (Fig. 4A) that was previously proposed to be a DUE (16). This region shares sequence homology with a cell cycle-dependent protein binding site in the human lamin B2 IR (1, 29, 39), suggesting it as a candidate for an initiator protein binding site (Fig. 4A, hatched box). Moreover, the AT-rich region has homology to the recently reported ORC-binding sequences in chorion gene amplification control element (ACE) ACE3 (6, 80) (Fig. 4A, checkered box). It also has homology with an AT-rich motif M found in Schizosaccharomyces pombe ARS elements (50). In order to determine whether the central AT-rich sequence in the DHFR ori-β region contributes to initiation activity, we deleted a 344-bp region containing this element from the 5.8-kb fragment (pMCDΔAT [Fig. 4A]).

The DHFR ori-β IR contains an AT-rich DNA sequence similar to ACE3 ORC binding sites (Fig. 4A, checkered box) (6, 12, 80). It also contains a stably bent DNA sequence and binding sites for the RIP60 protein (15, 16, 21, 45, 64). A deletion of 4 bp in a GC hexanucleotide between these elements was constructed to explore the effects of a small deletion on initiation activity (Fig. 4A, pAKO). Such minimal mutations in the ARS consensus sequence of budding yeast ARS elements have been shown to reduce or completely abolish ARS activity (58, 76, 84) by preventing ORC binding to the ARS (9, 32, 75, 78). A single-base-pair insertion between two T-antigen-binding sites in the simian virus 40 origin has also been shown to destabilize T-antigen binding by altering the spacing and consequently the interactions between the two T-antigen hexamers on DNA (20, 87).

Finally, a region upstream of the DHFR ori-β IR with an extensive T-rich stretch in one strand was chosen for deletion. Many characterized origins contain a sequence composed of a T-rich and an A-rich strand, the length of which appears to be critical for origin function, perhaps to facilitate strand separation (reviewed in reference 23). The T-rich stretch in the ori-β region contains a prominent cell cycle-dependent nuclease-hypersensitive site (72) (Fig. 4A, striped box) and an Alu repeat. Some Alu repeats have been correlated with DNA amplification and with autonomous replication activity of plasmid DNA (8, 48, 65). The T-rich region has sequence homology to the Drosophila ACE3 element (6, 80) (Fig. 4A, checkered box) and homology with AT-rich motifs C and D found in S. pombe ARS elements (50). In order to determine whether this T-rich region affects the initiation activity of the 5.8-kb fragment, we deleted a 263-bp region containing this element (pMCDΔTR [Fig. 4A]).

Mutant DNA fragments were transfected into DR12 cells, and drug-resistant pools of cells were selected. The amount of integrated exogenous ori-β fragment in each pool was monitored by PCR analysis of the genomic DNA as in Fig. 3A. Fig. 4B shows that the amount of exogenous ori-β in DNA from the mutant-transfected cell pools was about the same as the endogenous ori-β in an equal amount of CHOK1 DNA. Thus, the mutant origins were stably associated with chromosomal DNA in the same manner as the transfected wild-type 5.8-kb ori-β fragment (compare Fig. 4B and Fig. 3A).

The abundance of ori-β sequences in the small nascent DNA fraction prepared from pools of uncloned transfectants was then assayed by competitive PCR. A typical experiment with each mutant is shown in Fig. 4C and quantitatively evaluated in Table 4. The abundance of target DNA for pp2 in the nascent DNA fraction from three of the transfected mutants (pMCDΔDNR, pMCDΔAT, and pAKO) was significantly lower than the abundance of pp2 target sequences in nascent DNA from the transfected wild-type ori-β region (Table 4). Comparing the abundance of pp2 target sequence in nascent DNA with that of flanking target sequences demonstrates that the initiation activity of these three deletion mutants was markedly reduced. In contrast, deletion of the upstream T-rich element (pMCDΔTR) resulted in a fourfold increase in the abundance of pp2 target sequence relative to the abundance of the flanking pp3 target sequence (Table 4), indicating that deletion of the upstream T-rich element enhanced initiation activity at the ectopic ori-β locus.

TABLE 4.

Abundance of DHFR ori-β target DNA sequences in nascent DNAa

| DNA source | Abundanceb of DHFR ori-β target DNA (initiation activityc) with primer pair:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pp8 | pp2 | pp6 | pp3 | |

| pMCD pool | 1.13 × 10−6 (3.7) | 9.10 × 10−6 (29.6) | 2.00 × 10−6 (6.5) | 3.08 × 10−7 (1.0) |

| pMCDΔDNR pool | 4.18 × 10−8 (0.3) | 3.56 × 10−7 (2.5) | 2.69 × 10−7 (1.9) | 1.44 × 10−7 (1.0) |

| pMCDΔAT pool | 1.98 × 10−7 (0.7) | 1.18 × 10−6 (4.3) | 4.45 × 10−7 (1.6) | 2.73 × 10−7 (1.0) |

| pAKO pool | 1.54 × 10−7 (0.4) | 3.34 × 10−6 (7.6) | 6.56 × 10−7 (1.5) | 4.52 × 10−7 (1.0) |

| pMCDΔTR pool | 1.26 × 10−7 (1.3) | 1.20 × 10−5 (118.0) | 4.66 × 10−6 (45.9) | 1.01 × 10−7 (1.0) |

| Total DNA (pMCD pool) | 1.60 × 10−6 (0.4) | 5.60 × 10−6 (1.3) | 3.37 × 10−6 (0.8) | 4.18 × 10−6 (1.0) |

Values in the table are from a typical experiment.

Abundance was calculated as described in Materials and Methods.

Initiation activity was calculated as described in Materials and Methods.

To facilitate comparison between the mutants, the abundance of target sequences for each primer pair in three separate transfection experiments with each mutant was normalized to the abundance of target sequences for pp3 in the same experiment. As seen in Fig. 4D, the initiation activity for pMCDΔDNR-transfected cell pools was strongly and reproducibly reduced compared to that in pMCD-transfected cell pools (two-tailed t test, P value = 0.01, representing a confidence level of 98%). Initiation activity of pMCDΔAT-transfected cell pools was also significantly reduced compared to wild-type-transfected pools (two-tailed t test, P value = 0.02, representing a confidence level of 96%). Indeed, the initiation activities with the pMCDΔDNR and pMCDΔAT mutants were only slightly above the empirical background for the assay as determined using sheared total DNA (Table 4; Fig. 3C, white boxes). Deletion of 4 bp within the IR (pAKO) significantly diminished the initiation activity, but the reduction was more modest (two-tailed t test, P value = 0.10, representing a confidence level of 80%). Deletion of the upstream T-rich element (pMCDΔTR) clearly stimulated initiation activity (two-tailed t test, P value = 0.01, representing a confidence level of 98%) compared to the wild-type activity. The results demonstrate that the sequences deleted in three of the mutants were critical for ori-β activity. In contrast, the T-rich region was dispensable for the initiation of DNA replication at the ori-β site and suggests that this region may suppress initiation activity of the 5.8-kb fragment.

DISCUSSION

A 5.8-kb region surrounding the DHFR ori-β IR functions as an independent chromosomal replicator.

Evidence presented in this study indicates that a 5.8-kb fragment of the DHFR ori-β region placed in random ectopic chromosomal locations was sufficient to direct initiation of DNA replication from the ori-β start site (Fig. 3C). These data were obtained by using a competitive PCR-based nascent strand abundance assay with nascent template DNA enriched only by heat denaturation and size selection. Thus, a possible concern is that the template fraction contained not only nascent DNA but probably also small DNA fragments generated by shearing in vitro and single-strand breaks in vivo. To validate the preparation methods and assays used to assess the initiation activity of the 5.8-kb ectopic ori-β fragment, we initially tested these procedures with the endogenous DHFR locus (Fig. 2C). Direct comparison of our data on nascent strand abundance at the ori-β site in CHOK1 cells with data obtained by using lambda exonuclease digestion to further enrich for RNA-primed nascent DNA after the size fractionation (38) reveals remarkable congruence (52). The ratio of nascent DNA at the center of the ori-β IR to flanking nonreplicating DNA in our study averaged about 15-fold in multiple experiments (Fig. 2C), quantitatively comparable to the 12-fold enrichment reported by Kobayashi et al. for an experiment with CHOK1 cells (compare Fig. 2C of this report with Fig. 6B in reference 52). The reproducibility of the results obtained with the two different methods of enrichment for nascent DNA in the endogenous ori-β locus in CHOK1 cells argues strongly that the application of our methods to analysis of the ectopic ori-β fragments in DR12 hamster cells accurately reflects the initiation activity emanating from the ectopic fragments. However, it should be noted that the variability in our experiments was somewhat greater than was observed with the additional enrichment for nascent DNA using lambda exonuclease (52).

The initiation activity of the exogenous ori-β region in uncloned pools of stably transfected cells was at least as great as that observed for the endogenous ori-β region in CHOK1 cells (compare Fig. 2C and Fig. 3D). This result indicates that the ori-β region does not require either ori-β′ or ori-γ to direct initiation of chromosomal DNA replication. Since the ectopic ori-β fragments were incorporated at random in the genome of the transfected cells, the exogenous DNA fragments could conceivably integrate into a chromosomal context that directed efficient initiation from the ori-β IR. However, this possibility seems unlikely since at least some initiation activity was detected at the ectopic ori-β IR in each individual cell clone tested (Table 3). A simpler interpretation is that the 5.8-kb fragment contains all of the sequences necessary to specify the start sites for replication at ori-β, and hence this fragment serves as an independent chromosomal replicator. Further support for this interpretation is provided by the demonstration that specific DNA sequences within the 5.8-kb fragment were necessary for efficient initiation at the ori-β start site (Fig. 4; Table 4).

Although the exogenous 5.8-kb ori-β fragment was functional to some degree in at least six random ectopic locations, the initiation activity of the ori-β fragment varied among the individual cell clones from just above background to about half of that detected in uncloned pools of transfectants (Table 3). This clonal variation may reflect position effects exerted by the flanking chromatin that were masked when ori-β activity was measured in uncloned pools of pMCD-transfected cells (Fig. 3D). The notion that ectopic ori-β was subject to position effects would be consistent with the lower initiation activity of the ectopic fragments in the cloned lines compared to that in uncloned pools of transfected cells. It should be noted that initiation activity of the ectopic ori-β fragment in the pools of transfectants was determined 4 to 5 weeks after transfection, whereas the initiation activity of the ori-β fragment in the subclones was determined 14 weeks after transfection due to the time required to expand the cloned cells. The decreased initiation activity of the subclones could thus be due to progressive chromatin-mediated repression of the integrated ori-β fragment over time. Gradual extinction of gene expression from stably transfected genes has been frequently observed after long-term propagation of transfected cells, but this extinction was avoided when the transfected genes were flanked by insulators (73). Similarly, Drosophila ACEs placed at ectopic sites have been shown to be subject to position effects that were prevented by flanking the ACE with insulators (60).

The possibility that the ectopic ori-β region may be subject to position effects raises the question of how the endogenous DHFR initiation zone escapes position effects and whether it may be protected by elements such as insulators. Interestingly, a 3.2-kb fragment at the 3′ end of the DHFR coding sequence in the endogenous locus appeared to be required for all replication activity in the 55-kb initiation zone (49). This 3.2-kb DNA fragment was not included in the 5.8-kb ori-β fragment that was shown here to function as an independent replicator at ectopic sites in uncloned pools of stably transfected DR12 cells (Fig. 3). However, given that the 3.2-kb sequence in the endogenous DHFR locus flanks the initiation zone at one end, one possibility is that it may promote replication over the entire zone by insulating it from position effects that would prevent its initiation activity. Although other possible functions for this element can also be imagined, this speculation makes specific predictions that could be tested experimentally.

In the endogenous DHFR locus, the three preferred replication start sites in the initiation zone have been suggested to represent redundant genetic elements (72). One prediction of this hypothesis is that each preferred site should be sufficient, on its own, to direct initiation of DNA replication. Our data show that this prediction is met by the ori-β region. Another prediction is that deletion of one of the preferred start sites from the endogenous locus might be compensated for by increased activity at the remaining two preferred start sites. Consistent with this prediction, deletion of a 4.5-kb ori-β sequence in the endogenous locus overlapping the 5.8-kb ori-β fragment used in our study failed to reduce initiation activity in a broad zone that retained ori-β′ and ori-γ sequences, as detected by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (49). Since this 4.5-kb deletion encompassed two of the same regions in the 5.8-kb fragment that we found to be critical for initiation activity (pMCDΔAT and pAKO in Fig. 4), we speculate that the ori-β′ and ori-γ regions may be sufficient to direct initiation over the entire zone in the endogenous locus. It would be interesting to determine whether either the ori-β′ or ori-γ region could also serve as an independent chromosomal replicator in an ectopic location. The working model that the preferred start sites in the endogenous DHFR locus are redundant may provide additional insight into the complex patterns of replication intermediates observed for the 55-kb initiation zone by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (26, 28, 41, 86, 89).

Is the ori-β region composed of essential modular elements?

Studies of model systems have shown that replicators usually have a modular organization (reviewed in reference 22). The origin core consists of discrete elements: a DUE, an origin recognition element that contains binding sites for initiator proteins, and sometimes an AT-rich region. The core is often flanked by auxiliary elements that bind transcription factors and enhance the replication activity of the core element up to 1,000-fold.

In the ectopic DHFR ori-β region, at least two well-separated DNA sequence elements were critical for full activity (Fig. 4; Table 4). Deletion of the GA dinucleotide repeat in pMCDΔDNR or the central AT-rich sequence in pMCDΔAT reduced initiation activity nearly 10-fold. The markedly different sequence compositions of these two elements suggest that they probably serve different functions. Although these functions remain to be elucidated, several possible functions are suggested by previous studies. For example, GA dinucleotide repeats direct the establishment of a functionally important nucleosomal array in the transcription control region upstream of a Drosophila heat shock gene (61) and could play such a role in the ectopic DHFR ori-β region. The central AT-rich region that was deleted in pMCDΔAT harbors a potential DUE (16) and sequences homologous to a cell cycle-dependent protein footprint in the human lamin B2 (1, 25, 29, 39) and to the ORC binding sites in ACE3 (6, 80). Either DNA unwinding or protein binding could account for the requirement for the central AT-rich region in the 5.8-kb ori-β fragment. Alternatively, either or both of these two deletions could alter the spacing between flanking sequence elements, which may be critical for replication initiation.

A deletion of only 4 bp in the 5.8-kb ori-β fragment (pAKO) cut its initiation activity by half (Fig. 4D). Although this result was initially quite surprising, inspection of the DNA sequences around the deletion suggests at least two possible explanations for the striking effect of this mutation. The mutation removed 4 GC bp from a 6-bp run of GC sequence, one of only two such GC hexanucleotides in an AT-rich region of 1.2 kb between the pMCDΔAT and pMCDΔDNR mutations (Fig. 4A). Maintenance of this stretch of GC may be important for full initiation activity. Another possibility is that the 4-bp deletion altered the spacing between flanking modular elements that must cooperate to initiate replication. For example, insertions of approximately half of a DNA helical turn between neighboring elements in the SV40 early promoter was reported to decrease transcription activity by about 90%, whereas separation of the elements by a full helical turn was consistently less detrimental (81). Interestingly, the 4-bp deletion in pAKO resides just three nucleotides downstream of an AT-rich element that is homologous to ORC-binding sites in ACE3 (Fig. 4A) and may bind to hamster ORC protein (cited in reference 12). If ORC binding in this region indeed plays a role in ori-β activity, the 4-bp deletion may disrupt ORC interactions with flanking elements such as the stably bent region and the RIP60-binding sites whose functional importance remains unknown (15, 16).

In contrast with the other mutations, deletion of the upstream T-rich element (pMCDΔTR) more than tripled the activity of the DHFR ori-β IR (Fig. 4D), indicating that the T-rich element is not required for activity of the 5.8-kb fragment in ectopic sites. The deleted sequences encompassed an Alu repeat, a previously described cell cycle-dependent nuclease-hypersensitive site, and sequences homologous to ORC-binding sites in ACE3 and to S. pombe ARS elements (Fig. 4A), indicating that none of these elements is essential for ori-β activity. One possible interpretation of these data is that the T-rich element may limit the initiation activity of the ori-β region, either only in the ectopic fragment or also in the endogenous locus. Deletion of the T-rich element might eliminate a protein binding site that competes with the proposed ORC-binding site (12) immediately downstream from the deletion (Fig. 4A, checkered boxes) or possibly enhance cooperation between flanking DNA sequence elements that contribute to replicator activity. Alternatively, the deletion may affect chromatin structure, increasing protein access to the origin or promoting unwinding at the ori-β IR.

In summary, the results presented here strongly suggest that DNA sequences in the 5.8-kb DHFR fragment are sufficient to direct efficient initiation at the ori-β IR in multiple ectopic chromosomal sites and that initiation activity depends on discrete genetic elements located at or near the IR. Further characterization of these elements will be required to confirm their proposed modular nature and to elucidate their biochemical functions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank A. Schmidt and S. Dehde for their important contributions to the early phase of this project, M. Giacca for valuable technical advice, A. Carothers for DR12 cells, N. Heintz for DHFR DNA fragments, and A. Schmidt, M. Giacca, J. Hamlin, N. Heintz, and M. L. DePamphilis for sharing DHFR DNA sequence data. We appreciate the help of A. K. Patten with homology searches, R. Stein with statistical analysis, J. Francis with mutant construction, and U. Herbig and V. Podust with the manuscript.

The financial support of the NIH (GM 52948 and training grant CA 09385), the Army Breast Cancer Program (BC980907), and Vanderbilt University is gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdurashidova G, Riva S, Biamonti G, Giacca M, Falaschi A. Cell cycle modulation of protein-DNA interactions at a human replication origin. EMBO J. 1998;17:2961–2969. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.10.2961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdurashidova G, Deganuto M, Klima R, Riva S, Biamonti G, Giacca M, Falaschi A. Start sites of bidirectional DNA synthesis at the human lamin B2 origin. Science. 2000;287:2023–2026. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5460.2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aladjem M I, Groudine M, Brody L L, Dieken E S, Fournier K, Wahl G M, Epner E M. Participation of the human β-globin locus control region in initiation of DNA replication. Science. 1995;270:815–819. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5237.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aladjem M I, Rodewald L W, Koleman J L, Wahl G M. Genetic dissection of a mammalian replicator in the human β-globin locus. Science. 1998;281:1005–1009. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5379.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anachkova B, Hamlin J L. Replication in the amplified dihydrofolate reductase domain in CHO cells may initiate at two distinct sites, one of which is a repetitive sequence element. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:532–540. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.2.532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Austin R J, Orr-Weaver T L, Bell S P. Drosophila ORC specifically binds to ACE3, an origin of DNA replication control element. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2619–2623. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.20.2639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baran N, Lapidot A, Manor H. Unusual sequence element found at the end of an amplicon. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:2636–2640. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.7.2636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beitel L K, McArthur J G, Stanners C P. Sequence requirements for the stimulation of gene amplification by a mammalian genomic element. Gene. 1991;102:149–156. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90072-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bell S P, Stillman B. ATP-dependent recognition of eukaryotic origins of DNA replication by a multiprotein complex. Nature. 1992;357:128–134. doi: 10.1038/357128a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bielinsky A-K, Gerbi S A. Discrete start sites for DNA synthesis in the yeast ARS1 origin. Science. 1998;279:95–98. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5347.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bielinsky A-K, Gerbi S A. Chromosomal ARS1 has a single leading strand start site. Mol Cell. 1999;3:477–486. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80475-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bogan J A, Natale D A, DePamphilis M L. Initiation of eukaryotic DNA replication: conservative or liberal? J Cell Physiol. 2000;184:139–150. doi: 10.1002/1097-4652(200008)184:2<139::AID-JCP1>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brewer B J, Fangman W L. Initiation at closely spaced replication origins in a yeast chromosome. Science. 1993;262:1728–1731. doi: 10.1126/science.8259517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burhans W C, Vassilev L T, Caddle M S, Heintz N H, DePamphilis M L. Identification of an origin of bidirectional replication in mammalian chromosomes. Cell. 1990;62:955–965. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90270-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caddle M S, Dailey L, Heintz N H. RIP60, a mammalian origin-binding protein, enhances DNA bending near the dihydrofolate reductase origin of replication. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:6236–6243. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.12.6236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caddle M S, Lussier R H, Heintz N H. Intramolecular DNA triplexes, bent DNA and DNA unwinding elements in the initiation region of an amplified dihydrofolate reductase replicon. J Mol Biol. 1990;211:19–33. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90008-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calza R E, Eckhardt L, DelGiudice T, Schildkraut C L. Changes in gene position are accompanied by a change in time of replication. Cell. 1984;36:689–696. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90349-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chuang R Y, Kelly T J. The fission yeast homologue of Orc4p binds to replication origin DNA via multiple AT-hooks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2656–2661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clyne R K, Kelly T J. Genetic analysis of an ARS element from the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. EMBO J. 1995;14:6348–6357. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00326.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen G L, Wright P J, DeLucia A L, Lewton B A, Anderson M E, Tegtmeyer P. Critical spatial requirement within the origin of simian virus 40 DNA replication. J Virol. 1984;51:91–96. doi: 10.1128/jvi.51.1.91-96.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dailey L, Caddle M S, Heintz N, Heintz N H. Purification of RIP60 and RIP100, mammalian proteins with origin-specific DNA-binding and ATP-dependent DNA helicase activities. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:6225–6235. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.12.6225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DePamphilis M L. Origins of DNA replication that function in eukaryotic cells. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1993;5:434–441. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(93)90008-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DePamphilis M L. Origins of DNA replication. In: DePamphilis M L, editor. DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. pp. 45–86. [Google Scholar]

- 24.DePamphilis M L. Replication origins in metazoan chromosomes: fact or fiction? Bioessays. 1999;21:5–16. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199901)21:1<5::AID-BIES2>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeStanchina E, Gabellini P, Norio P, Giacca M, Peverali F A, Riva S, Falaschi A, Biamonti G. Selection of homeotic proteins for binding to a human DNA replication origin. J Mol Biol. 2000;299:667–680. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dijkwel P A, Hamlin J L. The Chinese hamster dihydrofolate reductase origin consists of multiple potential nascent-strand start sites. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3023–3031. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.6.3023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dijkwel P A, Hamlin J L. Sequence and context effects on origin function in mammalian cells. J Cell Biochem. 1996;62:210–222. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4644(199608)62:2%3C210::AID-JCB9%3E3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dijkwel P A, Vaughn J P, Hamlin J L. Replication initiation sites are distributed widely in the amplified CHO dihydrofolate reductase domain. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4989–4996. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.23.4989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dimitrova D S, Giacca M, Demarchi F, Biamonti G, Riva S, Falaschi A. In vivo protein-DNA interactions at a human DNA replication origin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1498–1503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dimitrova D S, Gilbert D M. The spatial position and replication timing of chromosomal domains are both established in early G1 phase. Mol Cell. 1999;4:983–993. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80227-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diviacco S, Norio P, Zentilin L, Menzo S, Clementi M, Biamonti G, Riva S, Falaschi A, Giacca M. A novel procedure for quantitative polymerase chain reaction by coamplification of competitive templates. Gene. 1992;122:313–320. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90220-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dutta A, Bell S P. Initiation of DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1997;13:293–332. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ermakova O V, Nguyen L H, Little R D, Chevillard C, Riblet R, Ashouian N, Birshtein B K, Schildkraut C L. Evidence that a single replication fork proceeds from early to late replicating domains in the IgH locus in a non-B cell line. Mol Cell. 1999;3:321–330. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80459-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferguson B M, Fangman W L. A position effect on the time of replication orign activation in yeast. Cell. 1992;68:333–339. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90474-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Folger K R, Wong E A, Wahl G, Capecchi M R. Patterns of integration of DNA microinjected into cultured mammalian cells: evidence for homologous recombination between injected plasmid DNA molecules. Mol Cell Biol. 1982;2:1372–1387. doi: 10.1128/mcb.2.11.1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Friedman K L, Diller J D, Ferguson B M, Nyland S V M, Brewer B J, Fangman W L. Multiple determinants controlling activation of yeast replication origins in late S phase. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1595–1607. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.13.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gale J M, Tobey R A, D'Anna J A. Localization and DNA sequence of a replication origin in the rhodopsin gene locus of Chinese hamster cells. J Mol Biol. 1992;224:343–358. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90999-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gerbi S A, Bielinsky A K. Replication initiation point mapping. Methods. 1997;13:271–280. doi: 10.1006/meth.1997.0526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giacca M, Zentilin L, Norio P, Diviacco S, Dimitrova D, Contreas G, Biamonti G, Perini G, Weighardt F, Riva S, Falaschi A. Fine mapping of a replication origin of human DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7119–7123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gilbert D M. Replication origins in yeast versus metazoa: separation of the haves and have nots. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1998;8:194–199. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(98)80141-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hamlin J L, Dijkwel P A, Vaughn J P. Initiation of replication in the Chinese hamster dihydrofolate reductase domain. Chromosoma. 1992;102:S17–S23. doi: 10.1007/BF02451781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Handeli S, Klar A, Meuth M, Cedar H. Mapping replication units in animal cells. Cell. 1989;57:909–920. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90329-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heintz N H, Hamlin J L. An amplified chromosomal sequence that includes the gene for dihydrofolate reductase initiates replication within specific restriction fragment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:4083–4087. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.13.4083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heintz N H, Milbrandt J D, Greisen K S, Hamlin J L. Cloning of the initiation region of a mammalian chromosomal replicon. Nature. 1983;302:439–441. doi: 10.1038/302439a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Houchens C R, Montigny W, Zeltser L, Dailey L, Gilbert J M, Heintz N H. The dhfr ori beta-binding protein RIP60 contains 15 zinc fingers: DNA binding and looping by the central three fingers and an associated proline-rich region. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:570–581. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.2.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jacob F, Brenner J, Cuzin F. On the regulation of DNA replication in bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1963;28:329–348. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jin Y, Yie T, Carothers A. Non-random deletions at the dihydrofolate reductase locus of Chinese hamster ovary cells induced by α-particle stimulating radon. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16:1981–1991. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.8.1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnson E M, Jelinek W R. Replication of a plasmid bearing a human Alu-family repeat in monkey COS-7 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:4660–4664. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.13.4660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kalejta R F, Li X, Mesner L D, Dijkwel P A, Lin H-B, Hamlin J L. Distal sequences, but not ori-beta/OBR-1, are essential for initiation of DNA replication in the Chinese hamster DHFR origin. Mol Cell. 1998;2:797–806. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80294-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim S-M, Huberman J A. Multiple orientation-dependent, synergistically interacting, similar domains in the ribosomal DNA replication origin of the fission yeast, Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:7294–7303. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.7294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim S-M, Huberman J A. Influence of a replication enhancer on the hierarchy of origin efficiencies within a cluster of DNA replication origins. J Mol Biol. 1999;288:867–882. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kobayashi T, Rein T, DePamphilis M L. Identification of primary initiation sites for DNA replication in the hamster dihydrofolate reductase gene initiation zone. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3266–3277. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kumar S, Giacca M, Norio P, Biamonti G, Riva S, Falaschi A. Utilization of the same DNA replication origin by human cells of different derivation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:3289–3294. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.17.3289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Leffak M, James C D. Opposite replication polarity of the germ line c-myc gene in HeLa cells compared with that of two Burkitt lymphoma cell lines. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:586–593. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.2.586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Leu T-H, Hamlin J L. High-resolution mapping of replication fork movement through the amplified dihydrofolate reductase domain in CHO cells by in-gel renaturation analysis. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:523–531. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.2.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Leu T-H, Hamlin J L. Activation of a mammalian origin of replication by chromosomal rearrangement. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:2804–2812. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.6.2804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li C, Bogan J A, Natale D A, DePamphilis M L. Selective activation of pre-replication complexes in vitro at specific sites in mammalian nuclei. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:887–898. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.5.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li J J, Herskowitz I. Isolation of ORC6, a component of the yeast origin recognition complex by a one-hybrid system. Science. 1993;262:1870–1874. doi: 10.1126/science.8266075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Little R D, Platt T H, Schildkraut C L. Initiation and termination of DNA replication in human rRNA genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:6600–6613. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.10.6600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lu L, Tower J. A transcriptional insulator element, the su(Hw) binding site, protects a chromosomal DNA replication origin from position effects. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2202–2206. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.2202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lu Q, Wallrath L L, Granok H, Elgin S C R. (CT)n(GA)n repeats and heat shock elements have distinct roles in chromatin structure and transcriptional activation of the Drosophila hsp26 gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:2802–2814. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.5.2802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Malott M, Leffak M. Activity of the c-myc replicator in an ectopic chromosomal location. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5685–5695. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.8.5685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Marahrens Y, Stillman B. Replicator dominance in a eukaryotic chromosome. EMBO J. 1994;13:3395–3400. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06642.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mastrangelo I A, Held P G, Dailey L, Wall J S, Hough P V, Heintz N, Heintz N H. RIP60 dimers and multiples of dimers assemble link structures at an origin of bidirectional replication in the dihydrofolate reductase amplicon of Chinese hamster ovary cells. J Mol Biol. 1993;232:766–778. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McArthur J G, Beitel L K, Chamberlain J W, Stanners C P. Elements which stimulate gene amplification in mammalian cells: role of recombinogenic sequences/structures and transcriptional activation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:2477–2484. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.9.2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moon K Y, Kong D, Lee J K, Raychaudhuri S, Hurwitz J. Identification and reconstitution of the origin recognition complex from Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12367–12372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Newlon C S. DNA replication in yeast. In: DePamphilis M L, editor. DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. pp. 873–914. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ogawa Y, Takahashi T, Masukata H. Association of fission yeast Orp1 and Mcm6 proteins with chromosomal replication origins. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:7228–7236. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.7228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Okuno Y, Satoh H, Sekiguchi M, Masukata H. Clustered adenine/thymine stretches are essential for function of a fission yeast replication origin. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:6699–6707. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.6699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pasero P, Braguglia D, Gasser S M. ORC-dependent and origin-specific initiation of DNA replication at defined loci in isolated yeast nuclei. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1504–1518. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.12.1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pelizon C, Diviacco S, Falaschi A, Giacca M. High-resolution mapping of the origin of DNA replication in the hamster dihydrofolate reductase gene domain by competitive PCR. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5358–5364. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]