Abstract

SWI-SNF alters DNA-histone interactions within a nucleosome in an ATP-dependent manner. These alterations cause changes in the topology of a closed circular nucleosomal array that persist after removal of ATP from the reaction. We demonstrate here that a remodeled closed circular array will revert toward its original topology when ATP is removed, indicating that the remodeled array has a higher energy than that of the starting state. However, reversion occurs with a half-life measured in hours, implying a high energy barrier between the remodeled and standard states. The addition of competitor DNA accelerates reversion of the remodeled array by more than 10-fold, and we interpret this result to mean that binding of human SWI-SNF (hSWI-SNF), even in the absence of ATP hydrolysis, stabilizes the remodeled state. In addition, we also show that SWI-SNF is able to remodel a closed circular array in the absence of topoisomerase I, demonstrating that hSWI-SNF can induce topological changes even when conditions are highly energetically unfavorable. We conclude that the remodeled state is less stable than the standard state but that the remodeled state is kinetically trapped by the high activation energy barrier separating it from the unremodeled conformation.

In eukaryotic cells, DNA is compacted into chromatin, the central unit of which is the nucleosome. Nucleosomes consist of an octamer of two each of the four core histones (H2A, H2B, H3, and H4) and approximately 146 bp of DNA. Core histones are small proteins (<140 amino acids), and each has a basic N-terminal tail. While these tails have been shown to be important for a wide range of regulatory processes (11, 16, 26, 31, 41), they are not required for remodeling by SWI-SNF (15, 28).

In general, DNA constrained within a nucleosome is less accessible than free DNA. Nucleosomal DNA generally impedes the function of DNA binding factors (7, 17) (14, 23) and has been shown to hinder the rate of transcription by RNA polymerase II (30, 48). One way that the cell may regulate accessibility to nucleosomal DNA is through the use of complexes that modify chromatin structure (21). This large and diverse group of complexes can be divided into two groups. One group utilizes the energy of ATP hydrolysis to remodel nucleosomes by altering the histone-DNA contacts through a yet undefined mechanism (45), whereas the other covalently modifies the nucleosome, predominantly within the histone tails.

ATP-dependent remodeling complexes are further subcategorized based on homologies to their central ATPase. ISWI-based complexes include NURF (42), CHRAC (43), and ACF (19) in Drosophila melanogaster and RSF in humans (25). SW12-SNF2-based complexes include SWI-SNF (3, 7, 34) and RSC (4) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and human SWI-SNF (hSWI-SNF) (22, 47) in humans. Homologues to these ATPases have also been found in other organisms (10, 51).

The hSWI-SNF complex was first purified through a series of chromatographic steps (22). This procedure yielded complexes containing both the hSWI2 homologues BRG1 and hBrm. While these ATPases also copurify with the IniI protein (40, 47), they do not copurify when either BRG1 or hBrm is immunoaffinity purified (47). Thus, there are at least two distinct hSWI-SNF complexes, one containing BRG1 as its central ATPase and the other containing hBrm (47). The hSWI-SNF complex used in this work was purified via the tagged IniI subunit and, as such, contains both the BRG1- and the hBrm-based complexes (40). Both of these complexes are able to alter the topology of a nucleosomal plasmid in an ATP-dependent manner (S. Sif, A. J. Saurin, A. N. Imbalzano, and R. E. Kingston, submitted for publication).

Using both the yeast and hSWI-SNF complexes, many studies have suggested that the remodeled state is maintained after ATP hydrolysis (6, 15, 18, 38). For example, there are a number of characteristic changes that persist after remodeling, including (i) disruptions in the mononucleosomal DNase I digestion pattern (6, 15, 18), (ii) changes in mononucleosome restriction enzyme accessibility (20, 38), (iii) alterations in a nucleosomal array's micrococcal nuclease (MNase) digestion pattern (20, 33), and (iv) topological changes in a nucleosomal plasmid (15, 18). In addition, a stable remodeled species can be isolated in vitro as a result of remodeling of mononucleosomes by SWI-SNF family members (29, 38). In contrast, three other studies suggest that remodeling may be more transient than was initially suspected. Two of these studies show that restriction enzyme accessibility of a remodeled array is not detectable after active remodeling (20, 27), and the other shows that a partially remodeled 5S nucleosomal array can revert in the absence of bound Gal4 protein (33).

One explanation for these differences is that the various protocols used to assay remodeling may measure different properties of a remodeled template. SWI-SNF is known to cause nucleosomes to shift position and has also been argued to cause changes in nucleosomal conformation. Conformational changes may revert differently than changes in the translational position. Protocols such as those that measure restriction enzyme access are likely to predominantly detect the movement of nucleosomes away from a restriction site, whereas protocols such as the plasmid supercoiling assay may measure changes in nucleosomal conformation.

There are two fundamentally different explanations for the persistence of a remodeled state. If the remodeled state is more stable than the unremodeled state, then at equilibrium the remodeled state will be the dominant species. Alternatively, the remodeled state may be less stable than the unremodeled state but it may be kinetically trapped because of a high activation energy separating it from the unremodeled state. In this case, the remodeled state will persist for a length of time determined by the height of the energy barrier but will eventually reconvert to yield predominantly the unremodeled state. Here we have distinguished between these two alternatives by using the plasmid supercoiling assay.

The plasmid supercoiling assay measures remodeling through changes in linking number. These changes cannot be accounted for by simple nucleosomal sliding; rather, there has to be some alteration of the plasmid's twist or writhe. If the changes in topology that occur as a result of SWI-SNF action reflect an altered nucleosomal conformation, then that conformation might revert to a standard topology over time if it is less energetically favorable. The rate of reversion would reflect the energy barrier between the remodeled state and the standard state; a high rate of reversion would imply a low energy barrier, and a low rate of reversion would imply a high energy barrier. We show that the topological shift induced by SWI-SNF reverts toward the standard state over many hours. This result indicates the presence of a distinct remodeled conformation with altered topology that is less thermodynamically favorable than that of the standard state. Our measurements of reversion rates under different conditions suggest that a high-energy barrier separates the remodeled state from the standard state and that binding of SWI-SNF to the template, even in the absence of ATP, stabilizes the remodeled state.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Purification of hSWI-SNF.

hSWI-SNF was purified as described previously (15, 40) and judged to be approximately 50% pure by silver stain analysis.

Purification of nucleosomes, trypsinized nucleosomes, histones, and trypsinized histones.

H1-depleted HeLa nucleosomes were prepared and quantitated as described previously (8, 15, 38, 44), with the exception that extracted nuclei from a Dignam nuclear extraction preparation were used as the starting material.

Trypsinized nucleosomes were made as previously described (1, 15). HeLa histones were purified via hydroxyapatite chromatography as described previously (15, 50). Trypsinized histones were prepared by creating a stock of trypsinized nucleosomes and then purifying the histones from the DNA, trypsin, and inhibitor via hydroxyapatite chromatography as described previously (15, 50).

Reconstitution of labeled plasmid nucleosomal arrays.

An internally labeled plasmid was prepared as described previously (40) by linearizing pSAB8 (2) with EcoRI. Briefly, the plasmid was treated with alkaline phosphatase (New England Biolabs [NEB], Inc.) and then rephosphorylated with T4 polynucleotide kinase (NEB, Inc.) and [γ-32P]ATP (NEN Life Sciences, Inc.). Labeled plasmid was separated from unincorporated nucleotides with a Sephadex G-50 (Pharmacia, Inc.) spin column. The labeled linear plasmid was religated at a concentration of 1 μg/ml with T4 DNA ligase (NEB, Inc.).

Internally labeled plasmid DNA was then reconstituted into nucleosomal arrays using Xenopus heat-treated assembly extracts (50) and full-length or trypsinized histones as required. The assembled plasmids were layered onto a 10 to 40% glycerol gradient (glycerol, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mg of bovine serum albumin [BSA] per ml). The gradient was run at 110,000 × g in a Beckman SW55 rotor for 4 h at 4°C. Fractions were collected and analyzed for assembly by deproteinizing and separating on an agarose gel.

Plasmid supercoiling assay. (i) Unconstrained template.

Plasmid supercoiling experiments were carried out with 23.5 μl of reaction buffer (65 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 13 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 15% glycerol, 5.5 mM MgCl2, 0.3 mM EDTA, 0.3 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 20 μg of BSA per ml) containing approximately 2 to 4 ng of nucleosomal plasmid DNA (∼1 nM total nucleosome concentration), 0.8 U of wheat germ topoisomerase I (Promega, Inc.), and hSWI-SNF to 300 ng (approximately 5 nM), both in the presence and absence of 2.1 mM ATP. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 30°C for 30 to 45 min.

Further remodeling was stopped by adding 1.5 μl of 0.25-U/μl apyrase (Sigma) reconstituted in a solution containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA, and 1 mg of BSA per ml. This was enough apyrase to completely stop remodeling in less than 1 min (unit definition; see also Fig. 2, lane 18). For samples in which competitor DNA was added, 1 μg of the pSAB8 plasmid (in 1 μl of Tris-EDTA [TE]) was added along with apyrase. pSAB8 is a 3.3-kb pUC18-based plasmid (2). Since the plasmid can also act as a competitor for topoisomerase I, 1 μl of 5-U/μl topoisomerase I (260 mM NaCl, 30 mM KCl, 37 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 6 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 0.68 mM EDTA, 0.67 mM DTT, 32% glycerol, 10 ng of BSA per μl, 3.5 mM MgCl2, 0.06 mM PMSF) was also added along with pSAB8. This is enough topoisomerase I to completely relax 1 μg of pSAB8 in less than 30 min under the same reaction conditions (unpublished observation). To reaction mixtures without competitor pSAB8, 1 μl of 0.8-U/μl topoisomerase I (20 mM NaCl, 60 mM KCl, 12 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 12 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 0.36 mM EDTA, 0.34 mM DTT, 15% glycerol, 20 ng of BSA per μl, 7 mM MgCl2, 0.12 mM PMSF) was added. Reaction mixtures were then reincubated at 30°C for the times indicated in the figure legends (see Fig. 1C, lane 2). Since activity for topoisomerase I decreases over time (unpublished observation), additional topoisomerase I was added to lengthy incubations as required at times of approximately 2, 6, and 19 h.

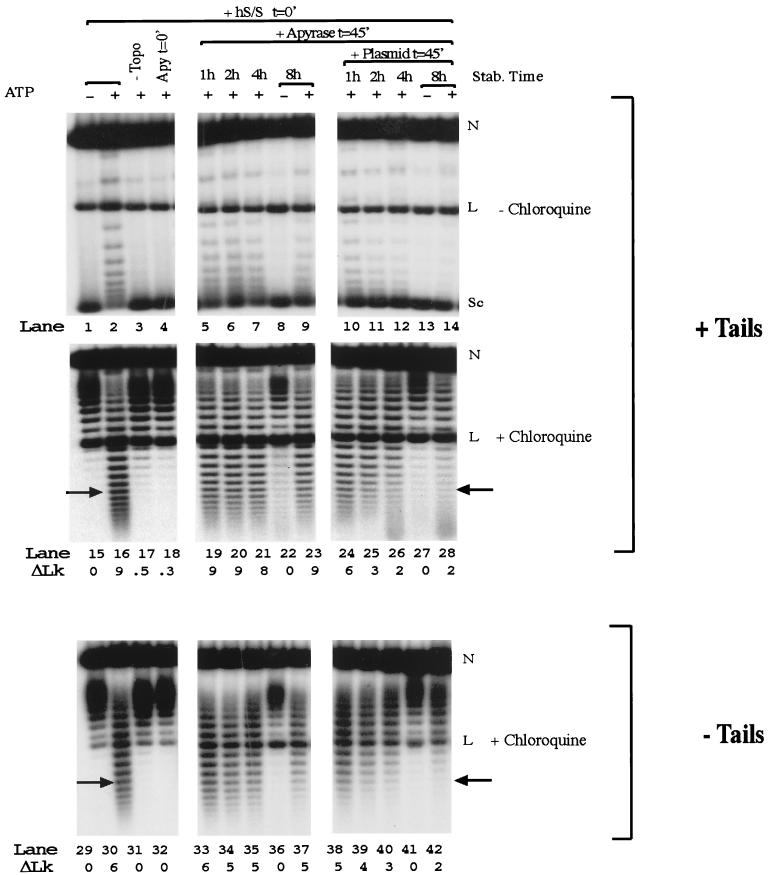

FIG. 2.

Addition of competitor DNA decreases the stability of a remodeled nucleosomal plasmid. Lanes 1 to 28, plasmid supercoiling assay using tailed nucleosomal arrays. Samples were split and run on two gels with one lacking chloroquine (lanes 1 to 14) and one containing chloroquine (lanes 15 to 28). Lanes 29 to 42, plasmid supercoiling assay using tailless nucleosomal templates run on an agarose gel containing chloroquine. Apyrase was added to samples in lanes 5 to 14, 19 to 28, and 33 to 42 after a 45-min remodeling reaction for which hSWI-SNF (hS/S), ATP, and topoisomerase I (Topo) were used. One microgram of pSAB8 was also added to lanes 10 to 14, 24 to 28, and 38 to 42. The stability (Stab.) time is the amount of time that expired between the addition of apyrase (Apy) and harvesting of the DNA. The arrow indicates the topoisomer quantitated when the rate constant was calculated (Fig. 3B). ΔLk, average change in linking number relative to that of an unremodeled array; N, nicked DNA; L, linear DNA; Sc, completely supercoiled DNA.

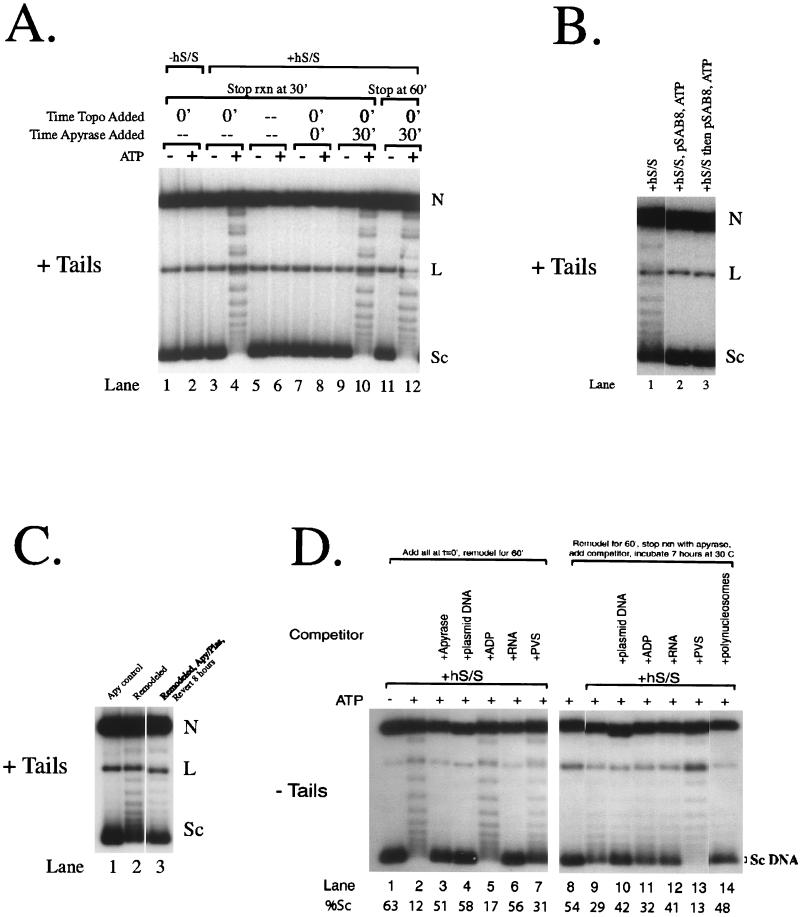

FIG. 1.

Persistence and reversion of the remodeled state. Samples were assayed on agarose gels without chloroquine. (A) Remodeling is persistent. Samples 1 to 10 were stopped at 30 min, while samples in lanes 11 to 12 were stopped at 1 h. (B) Plasmid DNA competes hSWI-SNF. Lane 1, remodeling for 45 min with hSWI-SNF, topoisomerase I, and ATP; lane 2, same as lane 1 except 1 μg of pSAB8 was added to the reaction mixture at the same time as hSWI-SNF; lane 3, hSWI-SNF incubated with the template, with 1 μg of pSAB8 being added 10 min later and ATP and topoisomerase I being added 15 min later and the DNA being harvested 25 min later. (C) Reversion of the array. Lane 1, 45-min remodeling reaction in which 0.25 U of apyrase was added with hSWI-SNF, topoisomerase I, and ATP; lane 2, 45-min remodeling reaction in the presence of hSWI-SNF, topoisomerase I, and ATP; lane 3, same as lane 2, except that, after remodeling, 0.25 U of apyrase, 1 μg of plasmid DNA (pSAB8), and 5 U of additional topoisomerase I were added to the reaction mixture, which was then reincubated at 30°C for 8 h. (D) Competitors for hSWI-SNF increase the reversion rate. Lane 2, 60-min remodeling reaction in the presence of hSWI-SNF, topoisomerase I, and ATP; lanes 3 to 7, same as lane 2 except that either apyrase or the indicated competitor was added to the reaction mixture at time zero; lanes 9 to 14, same as lane 2 except that, after remodeling, 0.25 U of apyrase, the indicated competitor, and additional topoisomerase I were added to the reaction mixtures, which were then reincubated at 30°C for 7 h. Reversion is quantitated by measuring the total proportion of highly supercoiled DNA (indicated with brackets and “Sc DNA”) versus that of all the topoisomers present on the gel. N, nicked DNA; L, linear DNA; Sc, completely supercoiled DNA; hS/S, hSWI-SNF; Topo, topoisomerase I; rxn, reaction; Apy, apyrase; Plas, plasmid DNA.

Reversion of the remodeled array was also tested in the presence of polyanions other than DNA (Fig. 1D). The amount of polyanion added was the amount necessary to mimic the charge of 1 μg of plasmid DNA. The polyanion was added after the remodeling reaction was stopped with apyrase, and the reaction mixture was then incubated for 7 h at 30°C. Additional topoisomerase I was added to all reaction mixtures after 2.5 and 5 h. As with plasmid DNA, poly(U) RNA and nucleosomal DNA can potentially compete for topoisomerase I; therefore, larger amounts of topoisomerase were used in these reactions.

Reactions were stopped at the times indicated in Fig. 1 and 2 and the plasmids were deproteinated by adding 2.5 μl of stop buffer (4.3% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 200 mM EDTA, 140 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0]) and 3 μl of proteinase K (20 mg/ml) before mixtures were incubated at 55°C for 1 h. Gel loading dye was added, and the samples were analyzed on either 1.75% agarose gel in 1× Tris-acetate-EDTA (TAE) at 40 V for 40 to 48 h or 1.5% agarose gels containing 4 mg of chloroquine/100 ml of gel in 1× Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) at 50 V for 72 h.

(ii) Constrained template.

Plasmid supercoiling experiments were carried out with 22.5 μl of reaction buffer (65 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 13 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 15% glycerol, 5.8 mM MgCl2, 0.3 mM EDTA, 0.3 mM DTT, 0.1 mM PMSF, 20 μg of BSA per ml) with approximately 2 to 4 ng of nucleosomal plasmid DNA (∼1 nM total nucleosome concentration) and hSWI-SNF to 250 ng (approximately 5 nM) both in the presence and absence of 2.2 mM ATP. The initial reaction mixtures contained no wheat germ topoisomerase I. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 30°C for 30 to 45 min. Further remodeling was stopped by adding 1.5 μl of 0.25-U/μl apyrase (Sigma, Inc.). For samples in which competitor DNA was added, 1 μg of the pSAB8 plasmid (in 1 μl of TE) was added at the same time as apyrase. The reaction mixtures were reincubated at 30°C for the times indicated (see Fig. 4) before topoisomerase I was added. To reaction mixtures without competitor pSAB8, 1 μl of 0.8-U/μl topoisomerase I was added. Since the plasmid can also act as a competitor for topoisomerase I, 1 μl of 5-U/μl topoisomerase I was added to these reaction mixtures. Topoisomerase I was incubated with the reaction mixtures for 45 min before the reaction was stopped by adding 2.5 μl of stop buffer and 3 μl of proteinase K (20 mg/ml). Reaction mixtures were then incubated at 55°C for 1 h. Gel loading dye was added, and the samples were analyzed either on 1.75% agarose gel in 1× TAE at 40 V for 40 to 48 h or on 1.5% agarose gels containing 4 mg of chloroquine/100 ml of gel in 1× TBE at 50 V for 72 h.

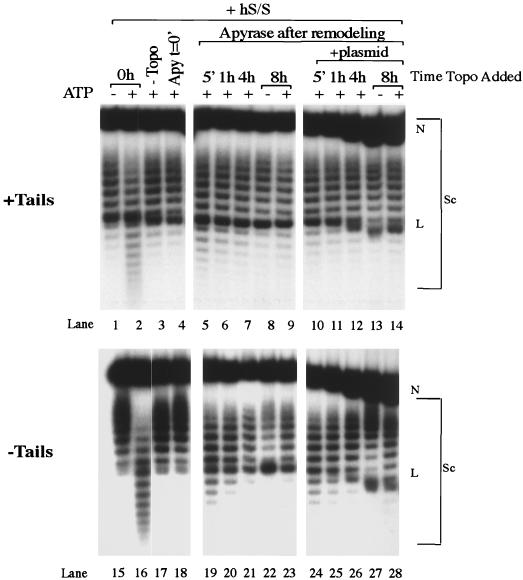

FIG. 4.

hSWI-SNF is able to remodel nucleosomes on a constrained array in the absence of topoisomerase I. Plasmid supercoiling assay mixtures were run on 1.5% agarose gels containing chloroquine. Samples in lanes 1, 2, 15, and 16 were remodeled for 45 min in the presence of hSWI-SNF (hS/S) and topoisomerase I (Topo). Samples in lanes 3, 4, 17, and 18 are the same except either topoisomerase was not added (lanes 3 and 17) or apyrase (Apy) was added at the beginning of the reaction (lanes 4 and 18). After a 45-min remodeling reaction with hSWI-SNF but without topoisomerase I, apyrase was added to samples in lanes 5 to 14 and 19 to 28. One microgram of plasmid was added to lanes 10 to 14 and 24 to 28. Topoisomerase I was added to the reaction mixture after apyrase at the times indicated. Samples were harvested 45 min later. N, nicked DNA; L, linear DNA; Sc, supercoiled DNA.

Data quantitation.

The topoisomers reflecting the different remodeled species were quantitated using a Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager. To analyze the distribution of topoisomers (see Fig. 3A), the profiles from the PhosphorImager were transferred into CricketGraph, normalized for total counts, and graphed. When necessary, 9-point averaging was used to smooth the plots.

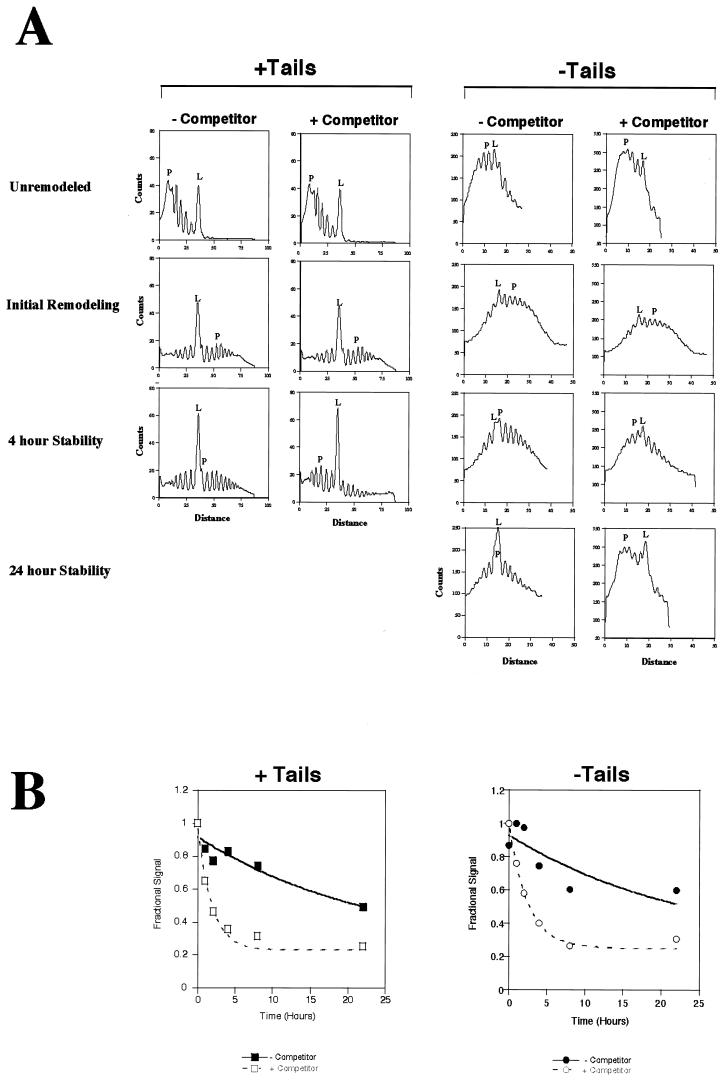

FIG. 3.

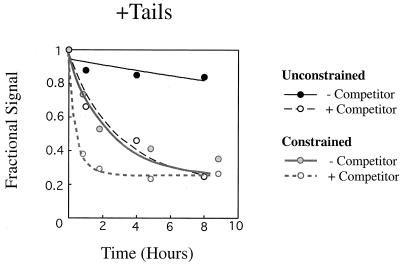

Reversion rates for tailed and tailless arrays. (A) Chloroquine gels similar to those shown in Fig. 2B were quantitated linearly using gels scanned with a PhosphorImager and analyzed with ImageQuant software. Lines were normalized for total counts and smoothed by 9-point averaging. “Distance” is the distance in millimeters from just below the nicked DNA on the gel and is specific to individual gels. The individual graphs are read from left to right as being unremodeled to remodeled. Since the contaminating nucleases affected tailless templates less than tailed templates (see the text), reversion for the 24-h time point is included only for the tailless array. “L” indicates the position of linear DNA, and “P” indicates the position of the peak of the topological distribution. (B) Reversion rates were obtained by plotting the normalized amount of a highly remodeled topoisomer versus reversion time. The particular topoisomer selected is shown with an arrow in Fig. 2B. Normalization was done by determining the fractional signal representative for the topoisomer being quantitated relative to those of all the topoisomers and adjusting to a maximum relative value of 1. First-order exponential decay curves were fit to the data with KaleidaGraph software using an apparent endpoint rather than 0 (see the text).

For the unconstrained arrays, reversion rates (see Table 1) were determined by plotting a highly remodeled topoisomer (see Fig. 2) as a fraction of all the topoisomers versus time. This fraction was normalized to a starting value of 1 and graphed (see Fig. 3B). Nonlinear least-squares fits to the data were used to determine the first-order rate constant for the reversion of a given remodeled state.

TABLE 1.

Rates of reversion and ΔG‡ under nonconstrained conditions

| Presence of tails | Presence of plasmid competitor | k1a of expt 1 (h−1) | Rb of expt 1 | k1 of expt 2 (h−1) | R of expt 2 | Avg k1 (h−1) | ΔG‡c (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | 0.03 | 0.91 | 0.03 | 0.77 | 0.03 | 24.8 |

| Yes | 0.32 | 0.97 | 0.64 | 0.97 | 0.48 | 23.1 | |

| No | No | 0.04 | 0.80 | 0.07 | 0.94 | 0.05 | 24.5 |

| Yes | 0.41 | 1.00 | 0.28 | 0.91 | 0.35 | 23.3 |

Rate constants (k1) were determined in a KaleidaGraph using a model of first-order exponential decay. When many experiments were performed (with tails), the most representative data are shown.

The R value for each curve.

Activation free energy for reversion (ΔG‡) was calculated using the formula k1 = (kT/h) × e(−ΔG‡/RT), where k1 is the average rate constant, k is the Boltzmann constant, h is the Planck constant, T is temperature (in kelvin), and R is the ideal gas constant.

When we determined rate constants for constrained arrays (see Fig. 6 and Table 2), the initial change (time [t] = 0 min after remodeling) for the measured topoisomer had to be estimated since the earliest the array could be analyzed was 50 min postremodeling (5 min for apyrase to cleave the ATP and 45 min for topoisomerase to work). This data point was estimated by extrapolation of the data points to time zero without competitor DNA using the first-order (exponential) fit mentioned above (see Fig. 6) and was necessary for data normalization. Since arrays were remodeled similarly before the addition of competitor, the estimated time zero data point was presumed to be the same whether or not competitor DNA was added after remodeling.

FIG. 6.

A constrained remodeled array is less stable than an unconstrained remodeled array. Reversion for the unconstrained array (remodeling with topoisomerase 1) is shown as in Fig. 3B. Reversion rates for the constrained array (remodeling without topoisomerase I) were obtained by plotting the normalized amount of a highly remodeled topoisomer versus reversion time.

TABLE 2.

Rates of reversion under constrained conditions

| Presence of tails | Presence of plasmid | kIa of expt 1 (h−1) | Rb of expt 1 | kI of expt 2 (h−1) | R of expt 2 | Avg constrained k1 (h−1) | Avg unconstrained k1 (from Table 1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | 0.14 | 0.86 | 0.20 | 0.82 | 0.17 | 0.03 |

| Yes | 1.40 | 0.96 | 1.95 | 0.98 | 1.68 | 0.48 | |

| No | No | 0.19 | 0.95 | 0.13 | 0.98 | 0.16 | 0.05 |

| Yes | 0.52 | 0.95 | 0.44 | 0.98 | 0.48 | 0.35 |

Rate constants (k1) were determined in a KaleidaGraph using a model of first-order exponential decay.

The R value for each curve is indicative of how well the curve fits the data.

Assembly of linear array.

The p2085S-G5E4 plasmid containing the linear array was the gift of J. Workman and K. Neely (Pennsylvania State University) (32). The 5S-G5E4 sequence (see Fig. 7A) was excised from the plasmid with the restriction enzymes Asp718 (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Inc.) and ClaI (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Inc.). DdeI (NEB, Inc.) was included in the restriction digest to facilitate band identification. The fragment was gel purified and end labeled by a Klenow fragment fill-in reaction at the Asp718 site. The linear DNA was assembled into a polynucleosomal template by gradient dialysis as described previously (35).

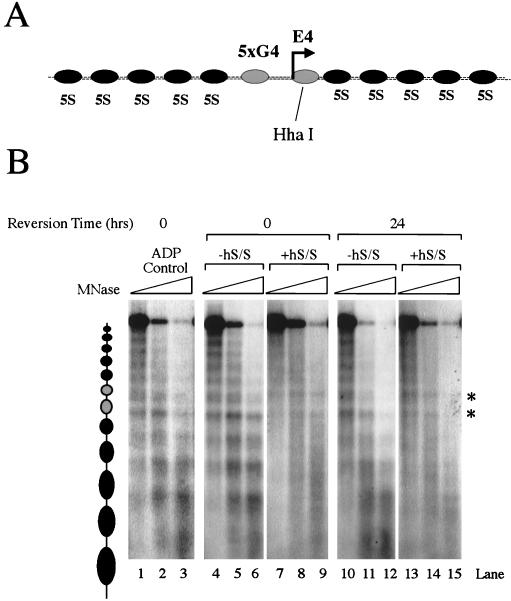

FIG. 7.

Reversion of an hSWI-SNF remodeled linear array. (A) Schematic of the array used for both the restriction enzyme accessibility experiment (see the text) and the MNase experiment, whose results are shown in panel B. The array contains two central nonpositioned nucleosomes flanked on either side by five nucleosomes positioned by repetitive 5S nucleosome positioning sequences (32). (B) The MNase nucleosome ladder of the array does not return after 24 h. Lanes 1 to 3 contain a control in which 10 mM ADP (final) is added with 0.3 mM ATP (final), hSWI-SNF, and topoisomerase I to test remodeling inhibition. Lanes 4 to 6 and 10 to 12 contain reaction mixtures in which the arrays were incubated in the presence of ATP for 1 h at 30°C; 10 mM ADP (final) was then added, and the samples were harvested either immediately after addition of the ADP or 24 h later. Lanes 7 to 9 and 13 to 15 include the addition of hSWI-SNF at time zero. Asterisks indicate areas of the array that are hypersensitive for MNase cutting. hS/S, hSWI-SNF.

MNase analysis of the remodeled array.

To ease comparison between the different assays, the MNase accessibility assay was performed similarly to the plasmid supercoiling assay (unconstrained), except that less hSWI-SNF was used (125 ng of hSWI-SNF instead of 250 ng) and less ATP was used (0.3 versus 2.2 mM). Although topoisomerase I was not included in the experiment whose results are shown in Fig. 7B, its inclusion had no effect on the experimental results (data not shown). The samples were remodeled for 1 h at 30°C. To analyze the stability of the remodeled array, further hSWI-SNF remodeling was stopped by adding 100 mM ADP–MgCl2 (in H2O) to a final concentration of 10 mM. This was enough ADP to inhibit continued remodeling by hSWI-SNF (see Fig. 7B). At this time, 1 μg of linear pSAB8 (in 1 μl of TE) was added to all reaction mixtures. Samples were analyzed at the indicated times (0 or 24 h postremodeling) by an MNase analysis by adding CaCl2 to 0.5 mM and then adding either 1, 3, or 10 mU of MNase (reconstituted in 50% glycerol–50 mM Tris [pH 8.0]–0.05 mM CaCl2). Samples were digested at 37°C for 3 min before addition of 2.5 μl of stop buffer (4.3% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 200 mM EDTA, 140 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0]) and 3 μl of proteinase K (20 mg/ml). Reaction mixtures were then incubated at 55°C for 1 h. Gel loading dye was added, and the samples were analyzed on a 1.5% agarose gel in 1× TAE at 40 V for approximately 16 h.

RESULTS

It has been shown using several assays that nucleosome remodeling by human and yeast SWI-SNF family complexes is stable for 30 min to 1 h following the removal of ATP from the reaction mixture (6, 15, 18, 38). To analyze the extent of that stability on nucleosomal arrays, and the effects of histone tail removal and SWI-SNF association on stability, we used the plasmid supercoiling assay. This protocol monitors ATP-dependent changes in topology of nucleosomal arrays (22). While the specific mechanism responsible for these changes is currently unknown, nucleosomal remodeling by hSWI-SNF presumably alters the original histone-DNA interactions in a manner that changes either the twist or the writhe of the DNA as it wraps around the octamer. These changes result in significant topological shifts on remodeled templates. This assay was chosen because it is sensitive for remodeling and because it is more specific to the SWI-SNF family of remodelers than either DNase I susceptibility or restriction enzyme access protocols. In addition, whereas SWI-SNF has been shown to facilitate nucleosomal sliding, the plasmid supercoiling assay is not expected to score for this since synchronized sliding would not manifest itself as stable changes in twist or writhe.

The basic experimental design was to generate changes in the topologies of nucleosomal arrays, either in the presence of topoisomerase I (nonconstrained conditions) or in the absence of topoisomerase I (constrained conditions), and then to compare the rate of reversion of the remodeled topology to that of a nonremodeled array. Changes in topology of a closed circular template come at a significant energetic cost. The free energy of a supercoiled template increases exponentially with the addition of each successive supercoil (e.g., introduction of one supercoil in a 3.4-kbp template with 16 nucleosomes is associated with an unfavorable change in free energy [ΔG] of approximately 0.7 kcal/mol and introduction of four supercoils results in a ΔG of approximately 11 kcal/mol [5, 9]). Thus, inclusion of topoisomerase I throughout the reaction allows for an assessment of remodeling and stability under conditions where the template is being constantly relaxed. Performing the remodeling reaction in the absence of topoisomerase I measures the ability of hSWI-SNF to change topology against a significantly larger energetic barrier.

Persistence of remodeled arrays under nonconstrained conditions is affected by the presence of SWI-SNF.

Topological changes in a closed circular template can be measured by analyzing the DNA on an agarose gel following deproteinization. Performing the electrophoresis under standard conditions (TAE buffer) results in supercoiled plasmids migrating more rapidly than relaxed plasmids. Addition of appropriate amounts of chloroquine, which intercalates and relaxes negatively supercoiled DNA, causes negatively supercoiled DNA to migrate more slowly and also causes previously relaxed closed circular DNA to adopt positive supercoils and thus migrate more rapidly. A 3.4-kbp plasmid that has been assembled into nucleosomes, relaxed with topoisomerase I, and deproteinized has 17 negative supercoils (approximately 1 per nucleosome [13, 39]) and thus migrates relatively rapidly on a TAE gel (e.g., Fig. 1A, lane 1) but slowly on a chloroquine gel (Fig. 2, lane 15). When topoisomerase is continually present in the reaction, hSWI-SNF dramatically changes topology in an ATP-dependent manner (Fig. 1A, compare lanes 3 and 4) (22). As reported previously (18), this remodeling is stable for 30 min following removal of ATP (Fig. 1A, compare lane 12 to lanes 10 and 4).

We wished to assess the effect of hSWI-SNF association on stability, so we developed conditions where we used free DNA to compete hSWI-SNF away from the template. Addition of 200-fold more free DNA than nucleosomal DNA completely inhibited SWI-SNF action (Fig. 1B, compare lanes 1 and 2; SWI-SNF was present at 5 nM, or in an ∼5-fold excess of the amount of nucleosomes), even when hSWI-SNF was prebound to the template (Fig. 1B, lane 3). Interestingly, some remodeling could be reversed after 8 h, when competitor DNA was added following remodeling (Fig. 1C, compare lanes 2 and 3 and see below). We also examined the effects of adding other potential competitors for SWI-SNF, including ADP, RNA, and polyvinylsulfate (PVS). Each was added at the same polyanion concentration as 1 μg of plasmid DNA. Using these potential competitors, we found that DNA and RNA inhibited SWI-SNF if they were added at the beginning of the reaction and that they were both effective at reversing remodeling (Fig. 1D, lanes 4, 6, 10, and 12). In addition, these compounds are unlikely to serve as transient “sinks” for nucleosomes, as fully assembled polynucleosomes (which bind SWI-SNF) are also effective at reversing remodeling (Fig. 1D, lane 14). At the concentrations used, ADP and PVS did not greatly inhibit SWI-SNF and were less effective at reversing remodeling (Fig. 1D, lanes 5, 7, 11, and 13). The inability of PVS to reverse remodeling suggests that reversion is not caused by simple polyanion effects; instead, the compounds that compete SWI-SNF away from the template appear to be the most effective at promoting reversion of the remodeled template. Tailless templates were used in this competition experiment (Fig. 1D) since the effects were most clear.

To determine the rate of reversion of the remodeled template back to a nonremodeled state, we performed a time course experiment. We remodeled the plasmid arrays in the presence of human SWI-SNF, ATP, and topoisomerase I for a sufficient time (30 to 45 min, depending upon the experiment) to ensure essentially complete remodeling (Fig. 2, lanes 1, 2, 15, and 16). The ATP was then hydrolyzed with apyrase, and the reaction continued at 30°C for 8 h. When the reaction was analyzed without the addition of competitor DNA, there was only a small change in the topological distribution of supercoiled isoforms over 8 h (Fig. 2, compare lane 2 to lanes 5 to 9 and compare lane 16 to lanes 19 to 23). In contrast, when competitor plasmid DNA was added after apyrase, there was a redistribution of topoisomers towards the highly supercoiled, unremodeled conformation over the same time scale (Fig. 2, compare lane 2 to lanes 10 to 14 and compare lane 16 to lanes 24 to 28). (The increase in nondiscrete, low-molecular-weight species at increasing times [e.g., lanes 26 and 28] may be caused by a nuclease in the apyrase used. We do not believe that this contaminating nuclease affects the interpretation of our results [see below].)

While the histone tails are not required for remodeling by SWI-SNF, they are important for nucleosome compaction (12) and factor accessibility (24, 46) and have been proposed to affect the ability of SWI-SNF to cycle efficiently during remodeling (28). We investigated the role of histone tails on reversion of the remodeled array. Tailless histones were prepared through a limited tryptic digest of HeLa nucleosomes, purified, and assembled into arrays. The remodeled tailless arrays were stable in the absence of competitor DNA (Fig. 2, compare lane 30 to lanes 33 to 37) but were again less stable in the presence of a DNA competitor (Fig. 2, compare lane 30 to lanes 38 to 42). In the majority of repeat experiments, reversion was more visually apparent on templates without tails.

Rates of reversion to the nonremodeled state are increased by competing DNA.

Reversion of remodeled nucleosomes should result in both the loss of the least supercoiled topoisomers and a concomitant increase in the most supercoiled DNA. This trend was best observed by quantifying topoisomers similar to those of Fig. 2 using a PhosphorImager, normalizing for total counts, and plotting the resultant profiles (Fig. 3A; data from chloroquine gels). This method confirmed that there was greater reversion after 4 h when DNA was present than when DNA was absent (Fig. 3A, compare positions of “P's,” the peaks of the topological distributions). It is also apparent that the amount of linear DNA (Fig. 3A, the sharp peak in the middle of the graph designated with an “L”) increases with time. We have attributed this increase to a contaminating nuclease in our apyrase stock. While this contaminant makes an extended analysis impossible, we do not believe this nuclease affects our interpretation of the data for the following reasons: (i) DNA-dependent reversion is visually apparent as an increase in the amount of highly supercoiled DNA (Fig. 2, compare lanes 2 to 12), (ii) the nuclease appears to cut all topoisomers essentially equally (Fig. 2, total counts in lanes 13 and 14 and also lanes 27 and 28 are within 90% of each other), (iii) DNA-dependent reversion occurs when calf intestinal phosphatase (not contaminated with nuclease) is used to cleave the ATP instead of apyrase (data not shown), and (iv) reversion also occurs when EDTA is added to a concentration of 10 mM along with apyrase to inhibit the nuclease (data not shown).

Rates for reversion for a series of experiments were calculated by quantifying a topoisomer representing a substrate which had been substantially remodeled (Fig. 2) and then comparing it to the total counts of all topoisomers. Topoisomers for quantitation were chosen in this way to minimize effects from more highly remodeled conformations transiting through the band being quantified. Since hSWI-SNF activity is typified by a wide distribution of topoisomers (Fig. 2, lanes 16 and 30), the band selected for quantitation typically represented 2 to 5% of the total topoisomers. The same band was used when results of experiments with and without DNA competitor were compared. The amount of the topoisomer was normalized to 1 and graphed for several reaction conditions (Fig. 3B). We note that background bands tend to increase slightly over time, which we attribute to a loss of a fraction of nucleosomes from the arrays over the lengthy incubations used. This background prevents the normalized signal from approaching 0. Hence, nonzero endpoints were used in first-order fits to the data to give a rate constant for reversion of the particular remodeled state (Table 1). The activation free energy for reversion (ΔG‡) was obtained from the rate constants (Table 1). Based on our analysis, the rate of reversion for remodeled tailed arrays increased approximately 16-fold by the addition of competitor DNA. For tailless arrays, there was a sevenfold increase in the reversion rate when competing DNA was added. Since hSWI-SNF is dissociated from the array quickly in the presence of competitor DNA (Fig. 1B, lane 3), we believe that the rates we have measured reflect the reversion of the remodeled nucleosome rather than the dissociation of SWI-SNF from the remodeled template.

hSWI-SNF can remodel nucleosomal arrays under topological constraints.

The results above suggest that the remodeled nucleosomal array has a long lifetime because it is kinetically trapped by the high ΔG‡ separating it from the unremodeled conformation. This result raised the possibility that the remodeled conformation resulting from hSWI-SNF action might have a sufficiently high ΔG‡ separating it from the unremodeled conformation so as to be observed on a constrained array. Less extensive remodeling is expected, however, because in the absence of topoisomerase, remodeling-induced topological changes will greatly destabilize arrays undergoing remodeling of multiple nucleosomes.

To determine if hSWI-SNF could remodel nucleosomes in a topologically constrained system, we incubated hSWI-SNF, ATP, and the plasmid nucleosomal array in the absence of topoisomerase I for 45 min. Remodeling was stopped by the addition of apyrase, and then topoisomerase I was added to the reaction mixtures to score for remodeling. Remodeling of constrained nucleosomal arrays resulted in a change in the distribution of topoisomers (Fig. 4, compare lanes 1 to 5 and compare lanes 15 to 19), suggesting that remodeling against topological constraints was possible. As anticipated, this change was not as extensive as that seen under nonconstrained conditions (Fig. 4, compare lanes 2 to 5 and lanes 16 to 19). In similar experiments with yeast SWI-SNF, remodeling was not very apparent under topologically constrained conditions; however, it is possible that this result was influenced by the lesser degree of assembly of the array or the amount of SWI-SNF in the reaction mixture (20).

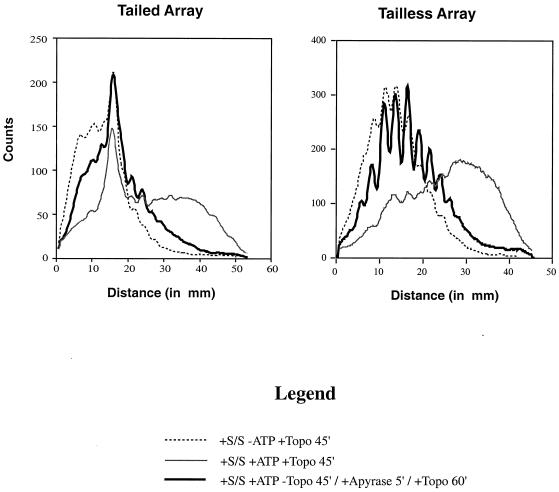

To quantify changes in the topological distribution that resulted from remodeling of a constrained array, chloroquine gels similar to those shown in Fig. 4 were scanned and plotted. Figure 5 shows that the array remodeled on a constrained plasmid (black line) is shifted away from the unremodeled array (dashed line) in the direction of a remodeled unconstrained array (gray line). The distribution of topoisomers showed that remodeling of a constrained array reproducibly (n = 4) yielded an average change in linking number of between 2 and 3. The topological change was not affected by whether or not histones had tails (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

The entire distribution of topoisomers is shifted on an hSWI-SNF remodeled constrained array. Chloroquine gels similar to those in Fig. 4 were quantitated linearly using gels scanned with a PhosphorImager and analyzed with ImageQuant software. “Distance” is the distance in millimeters from just below the nicked DNA on the gel and is specific to individual gels. The individual graphs are read from left to right as being unremodeled to remodeled. As a reference, the gray line shows the extent of remodeling with hSWI-SNF (S/S) and ATP in the presence of topoisomerase (Topo). The dotted line shows no remodeling in the absence of ATP. The black line shows remodeling by hSWI-SNF with ATP in the absence of topoisomerase I for 45 min; remodeling was stopped with apyrase for 5 min, and then topoisomerase I added for 45 min to score for stable remodeling. The sharp peak in the “+Tails” graph is linear DNA.

Analysis of the stability of the remodeled nucleosome on a constrained plasmid.

The high energy of remodeled templates in a constrained system might affect the ΔG‡ for reversion to the nonremodeled state, and therefore the rate of reversion might be altered (likely increased) when reversion is measured on a constrained template. We analyzed the rates of reversion by treating remodeled, constrained reactions with apyrase and then incubated the mixtures for periods up to 8 h before adding topoisomerase I. Topoisomerase I was allowed to work for 45 min before the reaction mixtures were deproteinized and run on a 1.5% chloroquine gel (Fig. 4). Under these conditions, tailed arrays reverted back to the unremodeled conformation within 8 h (Fig. 4, compare lanes 5 through 9). As with the unconstrained arrays, the addition of plasmid DNA significantly increased the rate of reversion, such that the less remodeled template was seen even at the earliest time point (Fig. 4, compare lanes 5 to 10). Similar results were seen when arrays lacking histone tails were analyzed (Fig. 4, lanes 19 to 28).

The rates for reversion of constrained arrays were obtained as with unconstrained arrays. The addition of free DNA had an approximately 10-fold effect on the rate of reversion of the remodeled conformation for tailed arrays and a 3-fold effect on tailless arrays (Fig. 6 and Table 2). Thus, conditions that compete hSWI-SNF from the template increase the rate of reversion under both constrained and unconstrained conditions. We compared the rates of reversion from constrained and unconstrained arrays. Note that we quantify the most substantially altered topoisomer, which differs on constrained and unconstrained arrays because of the different extents of remodeling. Even without normalization for this bias, we find that the rates for reversion of both tailed and tailless arrays are higher under the constrained conditions (Fig. 6 and Table 2), consistent with a higher energy of the remodeled state on a constrained versus an unconstrained template.

Analysis of the stability of a remodeled linear 5S array.

The plasmid supercoiling assay is thought to measure a unique conformational change of the DNA as it wraps around an SWI-SNF-remodeled nucleosome. This type of change may indicate the presence of an altered nucleosome conformation similar to that of the stable remodeled species described previously (29, 38). Other groups have also shown that SWI-SNF can move nucleosomes in cis (49); presumably, at least some of these nucleosomes are in a standard conformation following sliding. To examine the stability of the remodeled state with protocols that are sensitive to changes in nucleosome position, we used MNase digestion and restriction enzyme accessibility on 5S arrays.

MNase cleaves preferentially between nucleosomes such that a limited digest produces a characteristic nucleosomal ladder on a template that contains an array of 5S nucleosomes (Fig. 7A and B, lanes 1 to 3) (32). When the array is remodeled in the presence of both hSWI-SNF and ATP, the pattern is disrupted and appears as a smear (Fig. 7B, compare lanes 4 to 6 with lanes 7 to 9). This smear most likely represents both the generation of a stable remodeled species and also the movement of nucleosomes in cis. When the array is remodeled with hSWI-SNF and ATP for 1 h and then remodeling is stopped by adding a 30-fold excess of ADP (inhibits hSWI-SNF by competing ATP), the array does not revert back to its initial state after 24 h (Fig. 7B, compare lanes 10 to 12 to lanes 13 to 15). In some experiments, some faint nucleosomal banding did reappear (Fig. 7B, lanes 13 to 15), but the array did not return to its initial starting point even after 48 h (data not shown). These data potentially suggest that conformational changes as detected by the plasmid supercoiling assay may be less stable than nucleosomal movement in cis as detected by the MNase assay.

In addition, we also assayed for remodeling using restriction enzyme accessibility (27, 36). While some of the results obtained using this assay suggested remodeling reversion similar to that of the plasmid supercoiling assay, the high degree of background cutting of the nonremodeled template precluded us from drawing rigorous conclusions.

DISCUSSION

A number of previous studies have suggested that SWI-SNF induces persistent alterations to a nucleosomal template (6, 15, 18, 20, 38), whereas others suggest that remodeling may be more transient (20, 27, 33). This study addresses the persistence of these changes on a nucleosomal array. In agreement with previously published results (22), we show that hSWI-SNF is able to alter the topology of a closed nucleosomal plasmid in the presence of topoisomerase I and that this change is stable (18). We now show that these topological changes can be reversed in the absence of ATP hydrolysis. Since remodeled arrays predominantly revert back to the unremodeled conformation at equilibrium, this suggests that the remodeled array is of higher energy than the unremodeled form. Finally, the finding that reversion to the unremodeled conformation is slow suggests that the energy barrier between the two conformations is high. Interestingly, the reversion profile for a yeast-SWI-SNF remodeled mononucleosome (6) appears similar to our reversion profile for a nucleosomal array, suggesting that similar conclusions could potentially be drawn.

Since we do not know the mechanism for reversion, we have made an assumption and calculated the transition energy for this process based on the loss of a signal for a specific highly remodeled topoisomer over time. We recognize that the loss of signal from this one topoisomer could potentially come from reversion of any one of the many remodeled nucleosomes on the array. For example, if all 15 to 17 nucleosomes on the array were remodeled and reverted independently of each other, the rates for reversion of individual nucleosomes could be 15 to 17 times lower.

To begin to understand how the remodeled conformation is stabilized, we analyzed rates of reversion under different conditions. We find that the histone tails are not required for maintaining the remodeled conformation. In contrast, we find that the addition of free plasmid DNA accelerates reversion of the remodeled state to the unremodeled topology by more than 10-fold. Since plasmid DNA is a competitor for hSWI-SNF (Fig. 1B), we have interpreted this data to mean that hSWI-SNF binds to and stabilizes the remodeled conformation against reversion. Binding by hSWI-SNF to the remodeled conformation has also been suggested in other reports (38).

The observation that free DNA decreases the stability of the remodeled array also provides good evidence that topological changes in the plasmid supercoiling assay are not due to a dissociation of the histone octamer from the template. If this were true, then free plasmid DNA (a nucleosomal sink) would compete for the histone octamers and the supercoils lost during remodeling would never be restored. In contrast, we see significant restoration of supercoiling even in the presence of a vast excess of free DNA (Fig. 2).

While topoisomerase I is required in the plasmid supercoiling assay to maintain a topologically relaxed plasmid, it is not required for creating a remodeled state since hSWI-SNF can still remodel nucleosomes in its absence (Fig. 4). Topoisomerase I relaxes closed circular templates to states where they have low writhe and thus low supercoiled density. Introducing writhe into a constrained nucleosomal plasmid is highly energetically unfavorable, and thus remodeling of a relaxed, closed circular plasmid in the absence of topoisomerase I will create a state which is of significantly higher energy than that of the starting state. Consistent with our results for an unconstrained array, we show that a remodeled constrained array collapses at equilibrium to the more stable unremodeled topology. However, the low rates of reversion even under these constrained conditions suggest that a large activation energy barrier separates the remodeled nucleosome from an unremodeled one. This barrier serves as an effective kinetic trap which allows the unstable remodeled conformation to persist over a long time scale.

While it is not understood exactly how hSWI-SNF functions in the plasmid supercoiling assay, it is accepted that the DNA conformation has to be altered. Interestingly, it has been shown that yeast SWI-SNF can introduce positive supercoils into relaxed plasmid DNA (37). Control experiments show that if hSWI-SNF can introduce similar positive supercoils on naked plasmid DNA, then these changes are not stable in the presence of topoisomerase I (data not shown). This result suggests that the stable change in linking number observed on a nucleosomal plasmid as a consequence of hSWI-SNF remodeling is potentially the result of some conformational change within the nucleosome itself.

Finally, to buttress our conclusions, we assayed for reversion on a linear array using an MNase analysis. Using this assay, which detects remodeling as a loss of a nucleosomal ladder, hSWI-SNF remodeling appears to be more stable since the remodeled array does not revert back to the unremodeled conformation even after 24 h (Fig. 7B). This fact can potentially be explained if the MNase experiment detects both the generation of an altered remodeled nucleosome and nucleosome movement in cis. If nucleosomes are moved to a new translational position, it is unlikely that they would revert back to their starting position unless the starting position was more stable.

This study shows that, in the presence of topoisomerase, hSWI-SNF induces changes to a nucleosomal array that persist for an extended period of time. We propose that hSWI-SNF may stabilize the remodeled array by remaining bound to it, suggesting that hSWI-SNF dissociation may serve as a regulatory mechanism for chromatin structure. While topoisomerase and hSWI-SNF are both nuclear proteins, these enzymes may or may not be active on the same piece of DNA at the same time. Without topoisomerase I activity, the remodeled nucleosome appears to be less stable, suggesting that coordination of these enzymes may serve a role in modulating hSWI-SNF activity in vivo.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. Workman and K. Neely from Pennsylvania State University for providing the plasmid p2085S-G5E4 (32), which was used to make the template for the linear array used in Fig. 7. We thank N. Francis from our laboratory for labeling the linear template and assembling it into a nucleosomal array. We also appreciate critical reading of the manuscript by N. Francis, A. Saurin, G. Schnitzler, L. Corey, K. Lee, and others from our laboratory, who provided many insightful comments. In addition, we are grateful to M. Hirschel and C. Varughese from Cellex Biosciences, Inc., for growing the Ini-1 cell line used to purify hSWI-SNF.

This work was supported by grants from the NIH (to R.E.K.) and the Damon Runyon-Walter Winchell Foundation (to G.J.N.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ausio J, Dong F, van Holde K E. Use of selectively trypsinized nucleosome core particles to analyze the role of the histone “tails” in the stabilization of the nucleosome. J Mol Biol. 1989;206:451–463. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90493-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown S A, Imbalzano A N, Kingston R E. Activator-dependent regulation of transcriptional pausing on nucleosomal templates. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1479–1490. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.12.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cairns B R, Kim Y-J, Sayre M H, Laurent B C, Kornberg R D. A multisubunit complex containing the SWI1/ADR6, SWI2/SNF2, SWI3, SNF5, and SNF6 gene products isolated from yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1950–1954. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.5.1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cairns B R, Lorch Y, Li Y, Zhang M, Lacomis L, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Du J, Laurent B, Kornberg R D. RSC, an essential, abundant chromatin-remodeling complex. Cell. 1996;87:1249–1260. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81820-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark D J, Felsenfeld G. Formation of nucleosomes on positively supercoiled DNA. EMBO J. 1991;10:387–395. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07960.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Côté J, Peterson C L, Workman J L. Perturbation of nucleosome core structure by the SWI/SNF complex persists after its detachment, enhancing subsequent transcription factor binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4947–4952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.4947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Côté J, Quinn J, Workman J L, Peterson C L. Stimulation of GAL4 derivative binding to nucleosomal DNA by the yeast SWI/SNF complex. Science. 1994;265:53–60. doi: 10.1126/science.8016655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Côté J, Utley R T, Workman J L. Basic analysis of transcription factor binding to nucleosomes. Methods Mol Genet. 1995;6:108–128. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)74024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Depew D E, Wang J C. Conformational fluctuations of DNA helix. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:4275–4279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.11.4275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dingwall A K, Beek S J, McCallum C M, Tamkun J W, Kalpana G V, Goff S P, Scott M P. The Drosophila snr1 and brm proteins are related to yeast SWI/SNF proteins and are components of a large protein complex. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:777–791. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.7.777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Durrin L K, Mann R K, Kayne P S, Grunstein M. Yeast histone H4 N-terminal sequence is required for promoter activation in vivo. Cell. 1991;65:1023–1031. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90554-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia-Ramirez M, Dong F, Ausio J. Role of the histone “tails” in the folding of oligonucleosomes depleted of histone H1. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:19587–19595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Germond J E, Hirt B, Oudet P, Gross-Bellark M, Chambon P. Folding of the DNA double helix in chromatin-like structures from simian virus 40. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:1843–1847. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.5.1843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golding A, Chandler S, Ballestar E, Wolffe A P, Schlissel M S. Nucleosome structure completely inhibits in vitro cleavage by the V(D)J recombinase. EMBO J. 1999;18:3712–3723. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.13.3712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guyon J R, Narlikar G J, Sif S, Kingston R E. Stable remodeling of tailless nucleosomes by the human SWI-SNF complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2088–2097. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.2088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang L, Zhang W, Roth S Y. Amino termini of histones H3 and H4 are required for al-α2 repression in yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6555–6562. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.11.6555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imbalzano A N, Kwon H, Green M R, Kingston R E. Facilitated binding of TATA-binding protein to nucleosomal DNA. Nature. 1994;370:481–485. doi: 10.1038/370481a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Imbalzano A N, Schnitzler G R, Kingston R E. Nucleosome disruption by human SWI/SNF is maintained in the absence of continued ATP hydrolysis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:20726–20733. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ito T, Bulger M, Pazin M J, Kobayashi R, Kadonaga J T. ACF, an ISWI-containing and ATP-utilizing chromatin assembly and remodeling factor. Cell. 1997;90:145–155. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80321-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaskelioff M, Gavin I M, Peterson C L, Logie C. SWI-SNF-mediated nucleosome remodeling: role of histone octamer mobility in the persistence of the remodeled state. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:3058–3068. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.9.3058-3068.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kingston R E, Narlikar G J. ATP-dependent remodeling and acetylation as regulators of chromatin fluidity. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2339–2352. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.18.2339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwon H, Imbalzano A N, Khavari P A, Kingston R E, Green M R. Nucleosome disruption and enhancement of activator binding by a human SWI/SNF complex. Nature. 1994;370:477–481. doi: 10.1038/370477a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwon J, Imbalzano A N, Matthews A, Oettinger M A. Accessibility of nucleosomal DNA to V(D)J cleavage is modulated by RSS positioning and HMG1. Mol Cell. 1998;2:829–839. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80297-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee D Y, Hayes J J, Pruss D, Wolffe A P. A positive role for histone acetylation in transcription factor access to nucleosomal DNA. Cell. 1993;72:73–84. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90051-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.LeRoy G, Loyola A, Lane W S, Reinberg D. Purification and characterization of a human factor that assembles and remodels chromatin. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:14787–14790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000093200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ling X, Harkness T A, Schultz M C, Fisher-Adams G, Grunstein M. Yeast histone H3 and H4 amino termini are important for nucleosome assembly in vivo and in vitro: redundant and position-independent functions in assembly but not in gene regulation. Genes Dev. 1996;10:686–699. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.6.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Logie C, Peterson C L. Catalytic activity of the yeast SWI/SNF complex on reconstituted nucleosome arrays. EMBO J. 1997;16:6772–6782. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.22.6772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Logie C, Tse C, Hansen J C, Peterson C L. The core histone N-terminal domains are required for multiple rounds of catalytic chromatin remodeling by the SWI/SNF and RSC complexes. Biochemistry. 1999;38:2514–2522. doi: 10.1021/bi982109d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lorch Y, Cairns B R, Zhang M, Kornberg R D. Activated RSC-nucleosome complex and persistently altered form of the nucleosome. Cell. 1998;94:29–34. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81218-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lorch Y, LaPointe J W, Kornberg R D. Nucleosomes inhibit the initiation of transcription but allow chain elongation with the displacement of histones. Cell. 1987;49:203–210. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90561-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Megee P C, Morgan B A, Mittman B A, Smith M M. Genetic analysis of histone H4: essential role of lysines subject to reversible acetylation. Science. 1990;247:841–845. doi: 10.1126/science.2106160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neely K E, Hassan A H, Wallberg A E, Steger D J, Cairns B R, Wright A P, Workman J L. Activation domain-mediated targeting of the SWI/SNF complex to promoters stimulates transcription from nucleosome arrays. Mol Cell. 1999;4:649–655. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80216-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Owen-Hughes T, Utley R T, Côté J, Peterson C L, Workman J L. Persistent site-specific remodeling of a nucleosome array by transient action of the SWI/SNF complex. Science. 1996;273:513–516. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5274.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peterson C L, Dingwall A, Scott M P. Five SWI/SNF gene products are components of a large multisubunit complex required for transcriptional enhancement. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:2905–2908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.2905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Phelan M L, Schnitzler G R, Kingston R E. Octamer transfer and creation of stably remodeled nucleosomes by human SWI/SNF and its isolated ATPases. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:6380–6389. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.17.6380-6389.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Polach K J, Widom J. Mechanism of protein access to specific DNA sequences in chromatin: a dynamic equilibrium model for gene regulation. J Mol Biol. 1995;254:130–149. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quinn J, Fyrberg A M, Ganster R W, Schmidt M C, Peterson C L. DNA-binding properties of the yeast SWI/SNF complex. Nature. 1996;379:844–847. doi: 10.1038/379844a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schnitzler G, Sif S, Kingston R E. Human SWI/SNF interconverts a nucleosome between its base state and a stable remodeled state. Cell. 1998;94:17–27. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81217-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shure M, Vinograd J. The number of superhelical turns in native virion SV40 DNA and minicol DNA determined by the band counting method. Cell. 1976;8:215–226. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(76)90005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sif S, Stukenberg P T, Kirschner M W, Kingston R E. Mitotic inactivation of a human SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2842–2851. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.18.2842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thompson J S, Ling X, Grunstein M. The histone H3 amino terminus is required for telomeric and silent mating locus repression in yeast. Nature. 1994;369:245–247. doi: 10.1038/369245a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsukiyama T, Wu C. Purification and properties of an ATP-dependent nucleosome remodeling factor. Cell. 1995;83:1011–1020. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90216-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Varga-Weisz P D, Wilm M, Bonte E, Dumas K, Mann M, Becker P B. Chromatin-remodelling factor CHRAC contains the ATPases ISWI and topoisomerase II. Nature. 1997;388:598–602. doi: 10.1038/41587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vettese-Dadey M, Walter P, Chen H, Juan L-J, Workman J L. Role of the histone amino termini in facilitated binding of a transcription factor, GAL4-AH, to nucleosome cores. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:970–981. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.2.970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vignali M, Hassan A H, Neely K E, Workman J L. ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1899–1910. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.6.1899-1910.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vitolo J M, Thiriet C, Hayes J J. The H3–H4 N-terminal tail domains are the primary mediators of transcription factor IIIA access to 5S DNA within a nucleosome. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:2167–2175. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.6.2167-2175.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang W, Côté J, Xue Y, Zhou S, Khavari P A, Biggar S R, Muchardt C, Kalpana G V, Goff S P, Yaniv M, Workman J L, Crabtree G R. Purification and biochemical heterogeneity of the mammalian SWI-SNF complex. EMBO J. 1996;15:5370–5382. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wasylyk B, Chambon P. Transcription by eukaryotic RNA polymerases A and B of chromatin assembled in vitro. Eur J Biochem. 1979;98:317–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1979.tb13191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Whitehouse I, Flaus A, Cairns B R, White M F, Workman J L, Owen-Hughes T. Nucleosome mobilization catalysed by the yeast SWI/SNF complex. Nature. 1999;400:784–787. doi: 10.1038/23506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Workman J L, Taylor I C A, Kingston R E, Roeder R G. Control of class II gene transcription during in vitro nucleosome assembly. Methods Cell Biol. 1991;35:419–447. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60582-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang Q, Ekhterae D, Kim K H. Molecular cloning and characterization of P113, a mouse SNF2/SWI2-related transcription factor. Gene. 1997;202:31–37. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00446-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]