Abstract

As the number of elderly drivers rapidly increases worldwide, interest in the dangers of driving is growing as accidents rise. The purpose of this study was to conduct a statistical analysis of the driving risk factors of elderly drivers. In this analysis, data from the government organization’s open data were used for the secondary processing of 10,097 people. Of the 9990 respondents, 2168 were current drivers, 1552 were past drivers but were not driving presently, and 6270 did not have a driver’s license; the participants were divided into groups accordingly. The elderly drivers who were current drivers had a better subjective health status than those who were not. Visual and hearing aids were used in the current driving group, and their depression symptoms reduced as they drove. The elderly who were current drivers experienced difficulties while driving in terms of decreased vision, hearing loss, reduced arm/leg reaction speed, decreased judgment of the road conditions such as signals and intersections, and a decreased sense of speed. The results suggest that elderly drivers are unaware of the medical conditions that can negatively affect their driving. This study contributes to the safety management of elderly drivers by understanding their mental and physical status.

Keywords: elderly, driving risk, medical conditions, recognition, discomfort, health

1. Introduction

Globally, the number of elderly drivers aged 65 and over was 7685 million in 2019, accounting for 14.9% of the total population [1]. This number is rapidly and continuously increasing. Therefore, as many accidents occur among elderly drivers, interest in the dangers of driving is increasing [2]. One study reported that elderly people with a driver’s license can improve their independence by self-driving: thus, increasing their autonomy in participating in old-age activities [3]. Among the elderly, driving is considered an essential action that expands the scope of activities, such as leisure activities, visits to hospitals, and shopping, and provides opportunities for independence in their daily lives [4]. In this way, elderly drivers have positive emotional and social functions, given the increasing opportunities for social activities [5]. Thus, elderly people who drive themselves are considered to have a relatively high level of life satisfaction [6]. Approximately 30,000 cases were reported in 2018 in the Republic of Korea, and this number is continuously increasing [7,8]. When accidents occur, the elderly suffer serious injuries and have a slow recovery rate compared to young people [2,4]. As such, elderly drivers have a high risk of traffic accidents, and their anxiety about accidents is severe compared to the other age groups [5,9].

The ability of elderly drivers to self-regulate changes in their driving ability by becoming more aware of and managing their health status is naturally strengthened with increasing age [10]. Nevertheless, the reliability of elderly drivers’ awareness of their health status and driving ability is controversial [11]. In countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia, a self-reporting evaluation method was used to investigate the characteristics of elderly drivers [12,13]. Although they tend to avoid certain driving situations, such as night driving, long-distance driving, and driving when the roads are congested [8,14,15], they are affected by society and the culture to which they belong [16]. Some studies analyzed changes in behavior, cognition, perception, and physical function of elderly drivers while driving using the Self-report Assessment Forecasting Elderly Driving Risk (SAFE-DR), which was developed to assess the situation in the Republic of Korea [15,17,18].

Owing to medical advances and changes in the social environment, the proportion of elderly drivers is rapidly increasing and will continue to increase [1]. If elderly drivers are not aware of their physical changes and do not avail themselves of treatment in a timely manner, it interferes with their driving ability [5] and, consequently, increases the risk of accidents. This study aimed to analyze the physical characteristics, underlying diseases, and health consciousness of elderly drivers to identify their mental and physical conditions and help prevent traffic accidents. In addition, the researchers provide basic data for related research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sampling

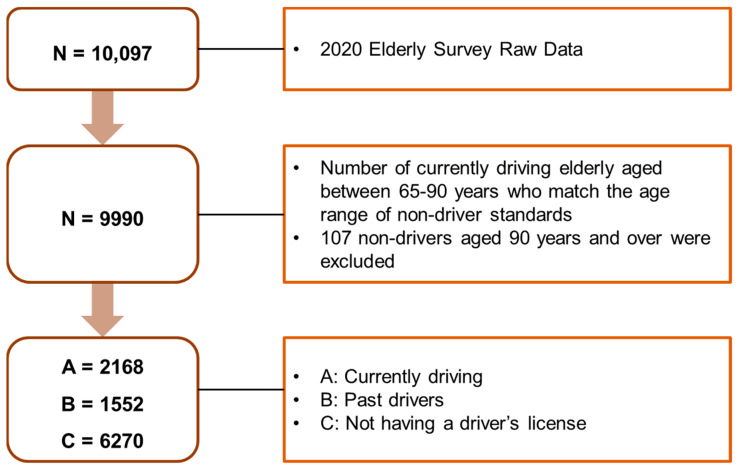

The data for this study were obtained from the Health and Welfare Data Portal of the Korea Institute of Health and Social Affairs and included the data of 10,097 elderly people in the Republic of Korea aged 65 years and over (National Statistics approval no. 117071). A total of 10,097 people were surveyed; 107 people who did not drive were excluded from the total, and the remaining 9990 people were divided into three groups: 2168 people who were currently driving, 1552 people who were past drivers but were not currently driving at the time of the survey, and 6270 people who had no driver’s license. Those with the highest age of elderly drivers at the time of the survey were selected and further classified as those without a driver’s license, past drivers, or not current drivers, who were at the time of the survey. The participants’ ages ranged from 65–90 years (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Data cleaning process flow.

2.2. Data Variables

The data description of the variables used in this study is as follows:

-

(1)

Driving status, which was divided into two groups: past drivers (not currently driving) and not having a driver’s license.

-

(2)

Health status and health behavior, which included thoughts on health in general; presence of chronic diseases (diseases lasting for more than 3 months as diagnosed by a doctor, namely circulatory diseases: high blood pressure, stroke (stroke, cerebral infarction), hyperlipidemia (dyslipidemia), angina pectoris, and myocardial infarction (heart failure and arrhythmia); endocrinal disease: diabetes and thyroid disease; musculoskeletal diseases: osteoarthritis (degenerative arthritis), rheumatoid arthritis, osteoporosis, low back pain, sciatica, fracture, dislocation, and after effects of accidents; respiratory diseases: chronic bronchitis, emphysema, asthma, pulmonary tuberculosis, and tuberculosis, neuropsychiatric diseases: depression, dementia, Parkinson’s disease, and insomnia; sensory diseases: cataract, glaucoma, chronic otitis media, senile deafness, skin disease, and cancer (malignant neoplasm); digestive diseases: gastroduodenal ulcer, hepatitis, and liver cirrhosis; genitourinary diseases: chronic kidney disease, prostatic hyperplasia, urinary incontinence, and anemia, etc.

-

(3)

State of physical function, including eyesight (watching TV, reading newspapers), hearing (talking on the phone, talking to the person next to you), chewing (chewing meat or hard things), and determining muscle strength (active movement (running about one lap (400 m) on the playground), walking around the playground (400 m), climbing 10 steps without a break, bending over, squatting, or kneeling, and reaching out for something higher than one’s head). Physical functioning was divided into lifting, moving, and disability determination.

-

(4)

Depressive symptoms were measured using the shortened geriatric depression scale (SGDS)-K15, which is a Korean translation of the SGDS developed by [19] to evaluate depressive symptoms in the elderly population (out of a total score of 15, individuals with a score of 8 or higher were classified as having depressive symptoms).

-

(5)

Social activities and discomfort in social activities were classified into two categories, namely, difficulty in using the information necessary for life and the inconvenience caused by using information technology in everyday life.

-

(6)

Economic activity was classified into current income, work, and desired work.

-

(7)

Precognitive function: cognitive function was confirmed and measured using the Mini-Mental State Examination for Dementia Screening (MMSE-DS) test tool. A representative screening test developed by [20] is widely used for simple and rapid measurement as well as screening for any cognitive impairment; the standardized Korean version of the mini-mental state examination (MMSE-K) [21], the Korean mini-mental state examination (K-MMSE) [22], and the mini-mental state examination-Korean children (MMSE-KC) [23] have been used in the Republic of Korea. A total mini-mental state examination (MMSE) score of 30 points is considered the cut-off point for cognitive impairment; a score of 0–10 indicates severe cognitive impairment, 10–20 indicates moderate cognitive impairment, 20–24 indicates mild cognitive impairment, and 24–30 indicates no cognitive impairment [14].

-

(8)

General characteristics, such as gender, height (cm), weight (kg), body mass index (kg/m²), drinking, smoking, education level, subjective age of the elderly, suicidal ideation, and health-type factors, were obtained.

2.3. Data Analysis

All continuous variables in this study are expressed as standard deviation mean (SD), and categorical variables are expressed as percentages (%) in their respective groups. A normality test was performed, and the significance of Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk was lower than the p-value of 0.05, so it was judged to be non-normal. The difference between all dependent variables, according to the presence or absence of driving, was verified using the Kruskal-Wallis test and the Chi-square test (frequency was 20.0% over performing a Fisher’s exact test). For the analysis, we used IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and the statistical significance level was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

The elderly who currently drive had a better subjective health status than those who did not. Among the current drivers, seven people had severe disabilities (grades 1–3), 44 had moderate disabilities (grades 4–6), 32 had physical disabilities, 11 had hearing impairments, three had visual impairments, and two had respiratory problems. At the time of the data investigation, most of the diseases had been cured, but there were differences between the groups in the treatment status of diabetes and chronic diseases, such as back pain, sciatica, pulmonary tuberculosis, and tuberculosis. The people who were not driving had more chronic diseases. In the currently driving group, the use of visual and hearing aids was 52.7% and 7.7%, respectively. Among the participants, 25.9% had discomfort due to bad eyesight, 15.1% had a hearing discomfort, and 28.0% experienced discomfort due to bending, squatting, kneeling, or reaching out for something higher than their heads. Of the respondents, 19.5% reported that it was difficult to perform touch movements. Depression symptoms decreased as they drove, and cognitive function was better in the driving group than in the other groups; however, it was also lower than the cut-off points for those over the age of 80. Among the elderly who were current drivers, 12.0% said that they experienced difficulties while driving in terms of decreased vision, hearing loss, decreased arm/leg reaction speed, decreased judgment (understanding of road conditions such as signals and intersections), and sense of speed. In other words, to prevent accidents due to aging, it is necessary to contribute to the safety management of elderly drivers by identifying their mental and physical conditions through precise identification of their mental and physical conditions.

3.1. General Characteristics

The general characteristics of the study participants were as follows: “current drivers” included 1729 men and 439 women; “past drivers but not current drivers” included 1237 men and 315 women; and 1045 men and 5225 women had “no driver’s license”. There was a difference between the groups with regard to age: “current drivers” 69.3(4.22), “past drivers but not current drivers” 74.08(5.74), and “no driver’s license” 74.58(6.54) (p < 0.001). Regarding the subjectively considered age of the elderly, there was a difference between the groups: 71.32(4.60) were “current drivers”, 69.72(4.14) were “past drivers but not current drivers”, and 70.02(4.04) had “no driver’s license” (p < 0.001). There was a difference in the presence or absence of disability determination as follows: 51 people were “current drivers”, 92 were “past drivers but not current drivers”, and 301 people had “no driver’s license” (p < 0.001). Regarding the degree of disability, “current drivers” comprised 7 people with severe disability (grades 1–3) and 44 people with moderate disability (grades 4–6); “past drivers but not current drivers” comprised 29 people with severe disability (grades 1–3) and 63 people with moderate disability (4–6); those with “no driver’s license” comprised 68 people with severe disability (1–3) and 233 people with moderate disability (4–6), exhibiting a group difference of p = 0.046. As for the usual subjective health status, 1598 people said they were “current drivers”, 749 people stated they were “past drivers but not current drivers”, and 2576 people stated they had “no driver’s license”; the perceived health difference was p < 0.001 (Table 1).

Table 1.

General characteristics of the participants.

| Characteristics | Driving | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current Drivers | Past But Not Current Drivers | No Driver’s License | X2 3/H 4 | p-Value | |||||

| N 5/M 1 | %/SD 2 | N/M | %/SD | N/M | %/SD | ||||

| Sex | Man | 1729 | 79.8 | 1237 | 79.7 | 1045 | 16.7 | 3864.248 | <0.001 |

| Female | 439 | 20.2 | 315 | 20.3 | 5225 | 83.3 | |||

| Height (cm) | 167.68 | 6.77 | 166.22 | 6.92 | 157.29 | 7.13 | 3209.849 | <0.001 | |

| Weight (kg) | 66.74 | 7.56 | 65.02 | 7.78 | 58.29 | 7.98 | 1940.261 | <0.001 | |

| Body mass index (BMI) | 23.71 | 2.09 | 23.52 | 2.35 | 23.55 | 2.82 | 13.557 | 0.001 | |

| Age (years) | 69.34 | 4.22 | 74.08 | 5.74 | 74.58 | 6.54 | 1192.218 | <0.001 | |

| Recognition of elderly age criteria | 71.32 | 4.60 | 69.72 | 4.14 | 70.02 | 4.04 | 167.758 | <0.001 | |

| Education Level | Uneducated (not reading) | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0.5 | 297 | 4.7 | 2320.532 | <0.001 |

| Uneducated (reading) | 10 | 0.5 | 50 | 3.2 | 739 | 11.8 | |||

| Elementary school | 261 | 12.0 | 394 | 25.4 | 2694 | 43.0 | |||

| Middle school | 483 | 22.3 | 431 | 27.8 | 1447 | 23.1 | |||

| High school | 1109 | 51.2 | 544 | 35.1 | 1013 | 16.2 | |||

| College | 126 | 5.8 | 41 | 2.6 | 36 | 0.6 | |||

| University | 179 | 8.3 | 85 | 5.5 | 44 | 0.7 | |||

| Disability | Yes | 51 | 2.4 | 92 | 5.9 | 301 | 4.8 | 32.257 | <0.001 |

| No | 2117 | 97.6 | 1460 | 94.1 | 5969 | 95.2 | |||

| Degree of disability | Severe disability (1–3 degree) |

7 | 13.7 | 29 | 31.5 | 68 | 22.6 | 6.154 | 0.046 |

| Moderate disability (4–6 degree) |

44 | 86.3 | 63 | 68.5 | 233 | 77.4 | |||

| Disability type | Mental retardation | 32 | 62.7 | 50 | 54.3 | 175 | 58.1 | - | - |

| Brain lesion disorder | 1 | 2.0 | 8 | 8.7 | 19 | 6.3 | |||

| Visual impairment | 3 | 5.9 | 6 | 6.5 | 26 | 8.6 | |||

| Deafness | 11 | 21.6 | 16 | 17.4 | 51 | 16.9 | |||

| Speech disorders | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.1 | 4 | 1.3 | |||

| Intellectual disability | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.1 | 5 | 1.7 | |||

| Autistic disorders | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |||

| Mental disorders | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.1 | 6 | 2.0 | |||

| Renal failure | 1 | 2.0 | 2 | 2.2 | 6 | 2.0 | |||

| Heart disorders | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 2.2 | 5 | 1.7 | |||

| Respiratory disorders | 2 | 3.9 | 3 | 3.3 | 1 | 0.3 | |||

| Hepatic impairment | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |||

| Facial disorders | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.1 | 0 | 0.0 | |||

| Stoma disorder | 1 | 2.0 | 1 | 1.1 | 2 | 0.7 | |||

| Epilepsy disorder | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.3 | |||

| Regular exercise | Yes | 1364 | 62.9 | 910 | 58.6 | 2951 | 47.1 | 191.752 | <0.001 |

| No | 804 | 37.1 | 642 | 41.4 | 3319 | 52.9 | |||

| Exercise time(min) / (1 time) | 57 | 28 | 48 | 28 | 44 | 24 | 272.011 | <0.001 | |

| Exercise frequency in 1 week |

1 time | 40 | 2.9 | 15 | 1.6 | 58 | 2.0 | 25.204 | 0.014 |

| 2 times | 141 | 10.3 | 85 | 9.3 | 242 | 8.2 | |||

| 3 times | 287 | 21.0 | 207 | 22.7 | 595 | 20.2 | |||

| 4 times | 102 | 7.5 | 63 | 6.9 | 222 | 7.5 | |||

| 5 times | 370 | 27.1 | 212 | 23.3 | 794 | 26.9 | |||

| 6 times | 93 | 6.8 | 86 | 9.5 | 270 | 9.1 | |||

| 7 times | 331 | 24.3 | 242 | 26.6 | 770 | 26.1 | |||

| Smoking | Yes | 514 | 23.7 | 278 | 17.9 | 310 | 4.9 | 666.616 | <0.001 |

| No | 1654 | 76.3 | 1274 | 82.1 | 5960 | 95.1 | |||

| Average amount of alcohol consumed (oz) | 4.46 | 2.40 | 4.07 | 2.17 | 3.21 | 1.98 | 290.814 | <0.001 | |

| Health status | Very healthy | 247 | 11.4 | 54 | 3.5 | 131 | 2.1 | 889.457 | <0.001 |

| Healthy | 1351 | 62.5 | 695 | 45.6 | 2445 | 39.8 | |||

| Normal | 450 | 20.8 | 497 | 32.6 | 2139 | 34.8 | |||

| Bad | 113 | 5.2 | 234 | 15.4 | 1286 | 20.9 | |||

| Very bad | 1 | 0.0 | 43 | 2.8 | 145 | 2.4 | |||

1 M: average, 2 SD: standard deviation, 3 X2: Chi-square test, 4 H: Kruskal-Wallis test, 5 N; frequency, p-value < 0.05.

3.2. Current Disease Status and Their Treatment

The results of the current disease status and whether there were patients receiving treatment are as follows: although there were differences in most diseases, treatment was completed at the time of investigation; however, there was a difference between the groups in the presence or absence of treatment for diabetes (p = 0.01), musculoskeletal diseases (back pain, sciatica) (p < 0.001), and respiratory diseases (pulmonary tuberculosis, tuberculosis) (p = 0.037). The total number of chronic diseases diagnosed by doctors was 1.37 (1.24) for “current drivers”, 1.78 (1.50) for “past drivers but not current drivers”, and 2.02 (1.50) for “no driver’s license” exhibiting differences between the groups (p < 0.001). The number of prescription drugs being taken for more than 3 months was 1.31 (1.20) for “current drivers”, 1.78 (1.74) for “past drivers but not current drivers”, and 1.94 (1.55) for “no driver’s license” (p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Health status and health behavior.

| Characteristics | Driving | X2 3/H 4 | p-Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current Drivers | Past But Not Current Drivers | No Driver’s License | |||||||

| N 5/M 1 | %/SD 2 | N/M | %/SD | N/M | %/SD | ||||

| Doctor’s diagnosis of hypertension | Yes | 1134 | 52.3 | 899 | 57.9 | 3710 | 59.2 | 31.204 | <0.001 |

| No | 1034 | 47.7 | 653 | 42.1 | 2560 | 40.8 | |||

| Treatment of hypertension | Yes | 1121 | 98.9 | 893 | 99.3 | 3657 | 98.6 | 3.518 | 0.172 |

| No | 13 | 1.1 | 6 | 0.7 | 53 | 1.4 | |||

| Doctor’s diagnosis of stroke (Stroke, cerebral infarction) |

Yes | 37 | 1.7 | 81 | 5.2 | 295 | 4.7 | 41.999 | <0.001 |

| No | 2131 | 98.3 | 1471 | 94.8 | 5975 | 95.3 | |||

| Treatment of stroke (Stroke, cerebral infarction) |

Yes | 37 | 100.0 | 80 | 98.8 | 285 | 96.6 | 2.251 | 0.325 |

| No | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.2 | 10 | 3.4 | |||

| Doctor’s diagnosis of hyperlipidemia (dyslipidemia) |

Yes | 324 | 14.9 | 193 | 12.4 | 1188 | 18.9 | 46.082 | <0.001 |

| No | 1844 | 85.1 | 1359 | 87.6 | 5082 | 81.1 | |||

| Treatment of hyperlipidemia (dyslipidemia) |

Yes | 313 | 96.6 | 190 | 98.4 | 1164 | 98.0 | 2.662 | 0.264 |

| No | 11 | 3.4 | 3 | 1.6 | 24 | 2.0 | |||

| Doctor’s diagnosis of angina pectoris and myocardial infarction |

Yes | 76 | 3.5 | 69 | 4.4 | 312 | 5.0 | 8.050 | 0.018 |

| No | 2092 | 96.5 | 1483 | 95.6 | 5958 | 95.0 | |||

| Treatment of angina pectoris and myocardial infarction |

Yes | 74 | 97.4 | 67 | 97.1 | 306 | 98.1 | 0.335 | 0.846 |

| No | 2 | 2.6 | 2 | 2.9 | 6 | 1.9 | |||

| Doctor’s diagnosis of heart diseases | Yes | 65 | 3.0 | 63 | 4.1 | 329 | 5.2 | 19.785 | <0.001 |

| No | 2103 | 97.0 | 1489 | 95.9 | 5941 | 94.8 | |||

| Treatment of heart diseases | Yes | 63 | 96.9 | 62 | 98.4 | 327 | 99.4 | 3.222 | 0.200 |

| No | 2 | 3.1 | 1 | 1.6 | 2 | 0.6 | |||

| Doctor’s diagnosis of diabetes | Yes | 421 | 19.4 | 401 | 25.8 | 1581 | 25.2 | 32.829 | <0.001 |

| No | 1747 | 80.6 | 1151 | 74.2 | 4689 | 74.8 | |||

| Treatment of diabetes | Yes | 419 | 99.5 | 401 | 100.0 | 1557 | 98.5 | 8.644 | 0.013 |

| No | 2 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 24 | 1.5 | |||

| Doctor’s diagnosis of thyroid disease | Yes | 36 | 1.7 | 38 | 2.4 | 235 | 3.7 | 25.968 | <0.001 |

| No | 2132 | 98.3 | 1514 | 97.6 | 6035 | 96.3 | |||

| Treatment of thyroid disease | Yes | 34 | 94.4 | 37 | 97.4 | 231 | 98.3 | 2.120 | 0.346 |

| No | 2 | 5.6 | 1 | 2.6 | 4 | 1.7 | |||

| Doctor’s diagnosis of osteoarthritis (Degenerative arthritis) |

Yes | 140 | 6.5 | 143 | 9.2 | 1288 | 20.5 | 299.936 | <0.001 |

| No | 2028 | 93.5 | 1409 | 90.8 | 4982 | 79.5 | |||

| Treatment of osteoarthritis (Degenerative arthritis) |

Yes | 126 | 90.0 | 133 | 93.0 | 1193 | 92.6 | 1.318 | 0.517 |

| No | 14 | 10.0 | 10 | 7.0 | 95 | 7.4 | |||

| Doctor’s diagnosis of osteoporosis | Yes | 50 | 2.3 | 73 | 4.7 | 701 | 11.2 | 198.134 | <0.001 |

| No | 2118 | 97.7 | 1479 | 95.3 | 5569 | 88.8 | |||

| Treatment of osteoporosis | Yes | 44 | 88.0 | 68 | 93.2 | 650 | 92.7 | 1.550 | 0.461 |

| No | 6 | 12.0 | 5 | 6.8 | 51 | 7.3 | |||

| Doctor’s diagnosis of low back pain and sciatica | Yes | 75 | 3.5 | 95 | 6.1 | 776 | 12.4 | 173.448 | <0.001 |

| No | 2093 | 96.5 | 1457 | 93.9 | 5494 | 87.6 | |||

| Treatment of low back pain and sciatica | Yes | 63 | 84.0 | 88 | 92.6 | 651 | 83.9 | 5.048 | 0.080 |

| No | 12 | 16.0 | 7 | 7.4 | 125 | 16.1 | |||

| Doctor’s diagnosis of fracture, dislocation, and aftereffects of accidents |

Yes | 17 | 0.8 | 19 | 1.2 | 93 | 1.5 | 6.242 | 0.044 |

| No | 2151 | 99.2 | 1533 | 98.8 | 6177 | 98.5 | |||

| Treatment of fracture, dislocation, and aftereffects of accidents |

Yes | 15 | 88.2 | 16 | 84.2 | 83 | 89.2 | 0.390 | 0.823 |

| No | 2 | 11.8 | 3 | 15.8 | 10 | 10.8 | |||

| Doctor’s diagnosis of fracture, chronic bronchitis, and emphysema |

Yes | 37 | 1.7 | 34 | 2.2 | 51 | 0.8 | 24.973 | <0.001 |

| No | 2131 | 98.3 | 1518 | 97.8 | 6219 | 99.2 | |||

| Treatment of chronic bronchitis and emphysema | Yes | 34 | 91.9 | 33 | 97.1 | 45 | 88.2 | 2.111 | 0.348 |

| No | 3 | 8.1 | 1 | 2.9 | 6 | 11.8 | |||

| Doctor’s diagnosis of asthma | Yes | 19 | 0.9 | 40 | 2.6 | 116 | 1.9 | 16.151 | <0.001 |

| No | 2149 | 99.1 | 1512 | 97.4 | 6154 | 98.1 | |||

| Treatment of asthma | Yes | 17 | 89.5 | 37 | 92.5 | 110 | 94.8 | 0.924 | 0.630 |

| No | 2 | 10.5 | 3 | 7.5 | 6 | 5.2 | |||

| Doctor’s diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis | Yes | 1 | 0.0 | 4 | 0.3 | 7 | 0.1 | 3.477 | 0.176 |

| No | 2167 | 100.0 | 1548 | 99.7 | 6263 | 99.9 | |||

| Treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis | Yes | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 75.0 | 7 | 100.0 | 6.600 | 0.037 |

| No | 1 | 100.0 | 1 | 25.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |||

| Doctor’s diagnosis of depression | Yes | 6 | 0.3 | 22 | 1.4 | 113 | 1.8 | 26.942 | <0.001 |

| No | 2162 | 99.7 | 1530 | 98.6 | 6157 | 98.2 | |||

| Treatment of depression | Yes | 6 | 100.0 | 18 | 81.8 | 100 | 88.5 | 1.634 | 0.442 |

| No | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 18.2 | 13 | 11.5 | |||

| Doctor’s diagnosis of dementia | Yes | 8 | 0.4 | 27 | 1.7 | 137 | 2.2 | 31.401 | <0.001 |

| No | 2160 | 99.6 | 1525 | 98.3 | 6133 | 97.8 | |||

| Treatment of dementia | Yes | 7 | 87.5 | 27 | 100.0 | 131 | 95.6 | 2.635 | 0.268 |

| No | 1 | 12.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 4.4 | |||

| Doctor’s diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease | Yes | 0 | 0.0 | 17 | 1.1 | 32 | 0.5 | 22.371 | <0.001 |

| No | 2168 | 100.0 | 1535 | 98.9 | 6238 | 99.5 | |||

| Treatment of Parkinson’s disease | Yes | 0 | 0.0 | 17 | 100.0 | 32 | 100.0 | - | - |

| No | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |||

| Doctor’s diagnosis of insomnia | Yes | 29 | 1.3 | 31 | 2.0 | 130 | 2.1 | 4.764 | 0.092 |

| No | 2139 | 98.7 | 1521 | 98.0 | 6140 | 97.9 | |||

| Treatment of insomnia | Yes | 22 | 75.9 | 25 | 80.6 | 106 | 81.5 | 0.488 | 0.784 |

| No | 7 | 24.1 | 6 | 19.4 | 24 | 18.5 | |||

| Doctor’s diagnosis of cataract | Yes | 93 | 4.3 | 70 | 4.5 | 282 | 4.5 | 0.177 | 0.915 |

| No | 2075 | 95.7 | 1482 | 95.5 | 5988 | 95.5 | |||

| Treatment of cataract | Yes | 78 | 83.9 | 57 | 81.4 | 205 | 72.7 | 6.008 | 0.050 |

| No | 15 | 16.1 | 13 | 18.6 | 77 | 27.3 | |||

| Doctor’s diagnosis of glaucoma | Yes | 18 | 0.8 | 21 | 1.4 | 50 | 0.8 | 4.465 | 0.107 |

| No | 2150 | 99.2 | 1531 | 98.6 | 6220 | 99.2 | |||

| Treatment of glaucoma | Yes | 14 | 77.8 | 20 | 95.2 | 40 | 80.0 | 2.914 | 0.233 |

| No | 4 | 22.2 | 1 | 4.8 | 10 | 20.0 | |||

| Doctor’s diagnosis of chronic otitis media | Yes | 16 | 0.7 | 13 | 0.8 | 27 | 0.4 | 5.261 | 0.072 |

| No | 2152 | 99.3 | 1539 | 99.2 | 6243 | 99.6 | |||

| Treatment of chronic otitis media | Yes | 16 | 100.0 | 13 | 100.0 | 26 | 96.3 | 1.094 | 0.579 |

| No | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 3.7 | |||

| Doctor’s diagnosis of senile deafness | Yes | 15 | 0.7 | 48 | 3.1 | 146 | 2.3 | 30.050 | <0.001 |

| No | 2153 | 99.3 | 1504 | 96.9 | 6124 | 97.7 | |||

| Treatment of senile deafness | Yes | 9 | 60.0 | 33 | 68.8 | 83 | 56.8 | 2.129 | 0.345 |

| No | 6 | 40.0 | 15 | 31.3 | 63 | 43.2 | |||

| Doctor’s diagnosis of skin disease | Yes | 23 | 1.1 | 15 | 1.0 | 29 | 0.5 | 11.072 | 0.004 |

| No | 2145 | 98.9 | 1537 | 99.0 | 6241 | 99.5 | |||

| Treatment of skin disease | Yes | 20 | 87.0 | 15 | 100.0 | 23 | 79.3 | 3.478 | 0.173 |

| No | 3 | 13.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 20.7 | |||

| Doctor’s diagnosis of cancer (malignant neoplasm) |

Yes | 33 | 1.5 | 39 | 2.5 | 95 | 1.5 | 7.911 | 0.019 |

| No | 2135 | 98.5 | 1513 | 97.5 | 6175 | 98.5 | |||

| Treatment of cancer (malignant neoplasm) |

Yes | 30 | 90.9 | 36 | 92.3 | 81 | 85.3 | 1.345 | 0.548 |

| No | 3 | 9.1 | 3 | 7.7 | 14 | 14.7 | |||

| Doctor’s diagnosis of gastroduodenal ulcer | Yes | 94 | 4.3 | 69 | 4.4 | 272 | 4.3 | 0.037 | 0.982 |

| No | 2074 | 95.7 | 1483 | 95.6 | 5998 | 95.7 | |||

| Treatment of gastroduodenal ulcer | Yes | 90 | 95.7 | 66 | 95.7 | 253 | 93.0 | 1.314 | 0.518 |

| No | 4 | 4.3 | 3 | 4.3 | 19 | 7.0 | |||

| Doctor’s diagnosis of hepatitis | Yes | 6 | 0.3 | 5 | 0.3 | 22 | 0.4 | 0.273 | 0.873 |

| No | 2162 | 99.7 | 1547 | 99.7 | 6248 | 99.6 | |||

| Treatment of hepatitis | Yes | 5 | 83.3 | 3 | 60.0 | 21 | 95.5 | 4.675 | 0.056 |

| No | 1 | 16.7 | 2 | 40.0 | 1 | 4.5 | |||

| Doctor’s diagnosis of liver cirrhosis | Yes | 5 | 0.2 | 11 | 0.7 | 15 | 0.2 | 9.434 | 0.009 |

| No | 2163 | 99.8 | 1541 | 99.3 | 6255 | 99.8 | |||

| Treatment of liver cirrhosis | Yes | 5 | 100.0 | 11 | 100.0 | 14 | 93.3 | 1.428 | 1.000 |

| No | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 6.7 | |||

| Doctor’s diagnosis of chronic kidney disease | Yes | 9 | 0.4 | 30 | 1.9 | 55 | 0.9 | 23.091 | <0.001 |

| No | 2159 | 99.6 | 1522 | 98.1 | 6215 | 99.1 | |||

| Treatment of chronic kidney disease | Yes | 9 | 100.0 | 28 | 93.3 | 54 | 98.2 | 1.663 | 0.472 |

| No | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 6.7 | 1 | 1.8 | |||

| Doctor’s diagnosis of prostatic hyperplasia | Yes | 118 | 5.4 | 123 | 7.9 | 100 | 1.6 | 185.803 | <0.001 |

| No | 2050 | 94.6 | 1429 | 92.1 | 6170 | 98.4 | |||

| Treatment of prostatic hyperplasia | Yes | 110 | 93.2 | 119 | 96.7 | 97 | 97.0 | 2.440 | 0.295 |

| No | 8 | 6.8 | 4 | 3.3 | 3 | 3.0 | |||

| Doctor’s diagnosis of urinary incontinence | Yes | 19 | 0.9 | 27 | 1.7 | 266 | 4.2 | 71.951 | <0.001 |

| No | 2149 | 99.1 | 1525 | 98.3 | 6004 | 95.8 | |||

| Treatment of urinary incontinence | Yes | 9 | 47.4 | 18 | 66.7 | 125 | 47.0 | 3.812 | 0.419 |

| No | 10 | 52.6 | 9 | 33.3 | 141 | 53.0 | |||

| Doctor’s diagnosis of anemia | Yes | 13 | 0.6 | 23 | 1.5 | 93 | 1.5 | 10.392 | 0.006 |

| No | 2155 | 99.4 | 1529 | 98.5 | 6177 | 98.5 | |||

| Treatment of anemia | Yes | 10 | 76.9 | 22 | 95.7 | 76 | 81.7 | 3.279 | 0.175 |

| No | 3 | 23.1 | 1 | 4.3 | 17 | 18.3 | |||

| Doctor’s diagnosis of ETC | Yes | 40 | 1.8 | 24 | 1.5 | 128 | 2.0 | 1.704 | 0.426 |

| No | 2128 | 98.2 | 1528 | 98.5 | 6142 | 98.0 | |||

| Treatment of ETC | Yes | 36 | 90.0 | 24 | 100.0 | 122 | 95.3 | 2.670 | 0.273 |

| No | 4 | 10.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 4.7 | |||

| Doctor’s diagnosis total number | 1.37 | 1.24 | 1.78 | 1.50 | 2.02 | 1.50 | 356.311 | <0.001 | |

| Prescription medication that currently taking for more than 3 months |

1.31 | 1.20 | 1.78 | 1.74 | 1.94 | 1.55 | 315.923 | <0.001 | |

1 M: average, 2 SD: standard deviation, 3 X2: Chi-square test, 4 H: Kruskal-Wallis test, 5 N: frequency, p-value < 0.05.

3.3. Physical Function Status and Discomfort in Daily Life

The following were the outcomes of the physical function status and discomfort in daily living: For those who answered “yes” regarding the use of a vision aid, 1142 people were “current drivers”, 890 people were “past drivers but not current drivers”, and 3247 people had “no driver’s license”; there was a difference between the groups (p < 0.001). As for those who answered “yes” in relation to the use of hearing aids, 1676 people were “current drivers”, 199 people were ” past drivers but not current drivers”, and 747 people had “no driver’s license”; there was a difference between the groups (p < 0.001). Those who were “uncomfortable” in their daily lives as a result of bad vision were as follows: “current drivers” consisted of 560 people, “past drivers but not current drivers” consisted of 508 people, and “no driver’s license” consisted of 2165 people; there was a difference between groups (p < 0.001). For discomfort due to hearing in daily life, “current drivers” consisted of 327 people, “past drivers but not current drivers” consisted of 383 people, and “no driver’s license” consisted of 1534 people who were “uncomfortable”; there was a difference between the groups (p < 0.001). Regarding the difficulty in performing motions (such as bending, squatting, or kneeling), “current drivers” consisted of 608 people, “past drivers but not current drivers” consisted of 770 people, and “no driver’s license” consisted of 3506 people who stated that it was “slightly or very difficult”; there was a difference between the groups (p < 0.001). For difficulty in performing movements (such as reaching out for something higher than their head), “current drivers” consisted of 423 people, “past drivers but not current drivers” consisted of 616 people, and “no driver’s license” consisted of 2911 people who stated that it was “slightly or very difficult”; there was a difference between groups (p < 0.001) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Physical function and daily life discomfort.

| Characteristics | Driving | X2 3/H 4 | p-Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current Drivers | Past But Not Current Drivers | No Driver’s License | |||||||

| N 1 | % 2 | N/M | % | N/M | % | ||||

| Assisted with eyesight | Yes | 1142 | 52.7 | 890 | 57.3 | 3247 | 51.8 | 15.459 | <0.001 |

| No | 1026 | 47.3 | 662 | 42.7 | 3023 | 48.2 | |||

| Assisted with hearing | Yes | 167 | 7.7 | 199 | 12.8 | 747 | 11.9 | 34.099 | <0.001 |

| No | 2001 | 92.3 | 1353 | 87.2 | 5523 | 88.1 | |||

| Assisted with chewing | Yes | 530 | 24.4 | 558 | 36.0 | 2546 | 40.6 | 181.906 | <0.001 |

| No | 1638 | 75.6 | 994 | 64.0 | 3724 | 59.4 | |||

| Discomfort of eyesight | Not uncomfortable | 1602 | 74.1 | 1015 | 66.6 | 3981 | 64.8 | 68.161 | <0.001 |

| Uncomfortable | 524 | 24.2 | 465 | 30.5 | 2039 | 33.2 | |||

| Very uncomfortable | 36 | 1.7 | 43 | 2.8 | 126 | 2.1 | |||

| Discomfort of hearing | Not uncomfortable | 1835 | 84.9 | 1140 | 74.9 | 4612 | 75.0 | 97.336 | <0.001 |

| Uncomfortable | 308 | 14.2 | 343 | 22.5 | 1400 | 22.8 | |||

| Very uncomfortable | 19 | 0.9 | 40 | 2.6 | 134 | 2.2 | |||

| Discomfort of chewing | Not uncomfortable | 1611 | 74.5 | 934 | 61.3 | 3608 | 58.7 | 173.696 | <0.001 |

| Uncomfortable | 501 | 23.2 | 522 | 34.3 | 2252 | 36.6 | |||

| Very uncomfortable | 50 | 2.3 | 67 | 4.4 | 286 | 4.7 | |||

| Muscle strength when sitting in a chair or bed and then getting up 5 times | Performed | 2008 | 92.6 | 1126 | 72.6 | 4174 | 66.6 | 586.185 | <0.001 |

| Tried but failed to perform (5 times not successful) | 82 | 3.8 | 302 | 19.5 | 1594 | 25.4 | |||

| Inability to even attempt to perform (elderly people with a vortex, or other disabilities that make it impossible to stand up) | 10 | 0.5 | 43 | 2.8 | 174 | 2.8 | |||

| Want to do it now | 68 | 3.1 | 81 | 5.2 | 328 | 5.2 | |||

| Difficulty in performing movements such as jumping one lap (400 m) on the playground | Not difficult at all | 576 | 26.6 | 189 | 12.2 | 454 | 7.2 | 1193.227 | <0.001 |

| Slightly difficult | 882 | 40.7 | 437 | 28.2 | 1371 | 21.9 | |||

| Very difficult | 508 | 23.4 | 580 | 37.4 | 2414 | 38.5 | |||

| Cannot do it at all | 163 | 7.5 | 304 | 19.6 | 1920 | 30.6 | |||

| Do now | 39 | 1.8 | 42 | 2.7 | 111 | 1.8 | |||

| Difficulty performing movements such as walking one lap (400 m) on the playground | Not difficult at all | 1606 | 74.1 | 807 | 52.0 | 2493 | 39.8 | 826.431 | <0.001 |

| Slightly difficult | 414 | 19.1 | 477 | 30.7 | 2107 | 33.6 | |||

| Very difficult | 124 | 5.7 | 187 | 12.0 | 1157 | 18.5 | |||

| Cannot do it at all | 16 | 0.7 | 72 | 4.6 | 469 | 7.5 | |||

| Do now | 8 | 0.4 | 9 | 0.6 | 44 | 0.7 | |||

| Difficulty in climbing 10 steps without a break | Not difficult at all | 1465 | 67.6 | 639 | 41.2 | 2030 | 32.4 | 907.291 | <0.001 |

| Slightly difficult | 550 | 25.4 | 567 | 36.5 | 2391 | 38.1 | |||

| Very difficult | 129 | 6.0 | 271 | 17.5 | 1415 | 22.6 | |||

| Cannot do it at all | 20 | 0.9 | 70 | 4.5 | 394 | 6.3 | |||

| Do now | 4 | 0.2 | 5 | 0.3 | 40 | 0.6 | |||

| Difficulty performing movements such as bending, squatting, or kneeling | Not difficult at all | 1535 | 70.8 | 722 | 46.5 | 2449 | 39.1 | 682.021 | <0.001 |

| Slightly difficult | 482 | 22.2 | 551 | 35.5 | 2410 | 38.4 | |||

| Very difficult | 126 | 5.8 | 219 | 14.1 | 1096 | 17.5 | |||

| Cannot do it at all | 22 | 1.0 | 58 | 3.7 | 293 | 4.7 | |||

| Do now | 3 | 0.1 | 2 | 0.1 | 22 | 0.4 | |||

| Difficulty performing movements such as reaching out for something above the head | Not difficult at all | 1729 | 79.8 | 895 | 57.7 | 3139 | 50.1 | 590.074 | <0.001 |

| Slightly difficult | 330 | 15.2 | 474 | 30.5 | 2162 | 34.5 | |||

| Very difficult | 93 | 4.3 | 142 | 9.1 | 749 | 11.9 | |||

| Cannot do it at all | 13 | 0.6 | 38 | 2.4 | 197 | 3.1 | |||

| Do now | 3 | 0.1 | 3 | 0.2 | 23 | 0.4 | |||

| Difficulty in performing operations such as lifting or moving about 8 kg of rice | Not difficult at all | 1478 | 68.2 | 694 | 44.7 | 2097 | 33.4 | 855.233 | <0.001 |

| Slightly difficult | 496 | 22.9 | 519 | 33.4 | 2316 | 36.9 | |||

| Very difficult | 166 | 7.7 | 254 | 16.4 | 1304 | 20.8 | |||

| Cannot do it at all | 25 | 1.2 | 79 | 5.1 | 521 | 8.3 | |||

| Do now | 3 | 0.1 | 6 | 0.4 | 32 | 0.5 | |||

1 N: frequency, 2 %: percentage, 3 X2: Chi-square test, 4 H: Kruskal-Wallis test, p-value < 0.05.

3.4. Depressive Symptom

As a result of examining the depressive symptoms, the score was 10.08 (2.21) for “current drivers”, 10.40 (2.20) for “past drivers but not current drivers”, and 10.34 (2.28) for “no driver’s license”, with a cut-off point of 8. The “current drivers” group exhibited a lower depression score than the “no driver’s license” (p < 0.001) group. Despite this, all groups were found to have high levels of depression.

3.5. Economic Activity

The results related to economic activity were as follows: In relation to current economic activity, 1432 people were from the “current drivers” group, 448 people from the “past drivers but not current drivers” group, and 1898 people from the “no driver’s license” group were “currently working”. There were 676 “current drivers”, 1041 “past drivers but not current drivers”, and 3116 having “no driver’s license” who had “previously worked but not currently working”. The “never worked” people who were “current drivers” were 60 people, “previously a driver but not currently” were 63 people, and 1256 people had “no driver’s license”; there was a difference between the groups (p < 0.001). As for the participants who would like to work in the future, there were 804 people who “didn’t want to work” who were “current drivers” and 1006 people who had “no driver’s license”; 4298 people indicated wanting to “continue their current work” of which 1135 people were “current drivers” and 334 people had “no driver’s license”; 1339 people wanted to “continue with current job”, of which 82 people were “current drivers”, 53 people were “past drivers but not current drivers”, and 130 people had “no driver’s license. There were 141 “current drivers”, 130 “past drivers but not current drivers”, and 379“having no driver’s license”; there was a difference between groups (p < 0.001) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Social and economic activity.

| Characteristics | Driving | X2 3/H 4 | p-Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current Drivers | Past But Not Current Drivers | No Driver’s License | |||||||

| N 1 | % 2 | N/M | % | N/M | % | ||||

| Current economic activity | Currently working | 1432 | 66.1 | 448 | 28.9 | 1898 | 30.3 | 1305.474 | <0.001 |

| Previously worked but not currently | 676 | 31.2 | 1041 | 67.1 | 3116 | 49.7 | |||

| Not working | 60 | 2.8 | 63 | 4.1 | 1256 | 20.0 | |||

| Current work | Farmers and fisheries | 353 | 24.7 | 77 | 17.2 | 482 | 25.4 | 854.529 | <0.001 |

| Cost facilities management | 159 | 11.1 | 92 | 20.5 | 132 | 7.0 | |||

| Cleaning | 59 | 4.1 | 65 | 14.5 | 468 | 24.7 | |||

| Production | 83 | 5.8 | 27 | 6.0 | 69 | 3.6 | |||

| Household care | 21 | 1.5 | 3 | 0.7 | 82 | 4.3 | |||

| Driving transport | 160 | 11.2 | 8 | 1.8 | 8 | 0.4 | |||

| Professions | 69 | 4.8 | 8 | 1.8 | 20 | 1.1 | |||

| Office | 37 | 2.6 | 7 | 1.6 | 8 | 0.4 | |||

| Cooking and food | 148 | 10.3 | 33 | 7.4 | 242 | 12.8 | |||

| Courier and delivery | 20 | 1.4 | 3 | 0.7 | 4 | 0.2 | |||

| Site management | 46 | 3.2 | 16 | 3.6 | 22 | 1.2 | |||

| Environmental landscaping | 27 | 1.9 | 27 | 6.0 | 114 | 6.0 | |||

| Construction machinery | 135 | 9.4 | 23 | 5.1 | 28 | 1.5 | |||

| Culture and arts | 9 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.2 | |||

| Maintaining public order | 14 | 1.0 | 16 | 3.6 | 69 | 3.6 | |||

| Waste paper collection | 5 | 0.3 | 8 | 1.8 | 24 | 1.3 | |||

| ETC | 87 | 6.1 | 35 | 7.8 | 123 | 6.5 | |||

| Work status | Don’t want to work | 804 | 37.2 | 1006 | 66.1 | 4298 | 69.9 | 867.564 | <0.001 |

| Continue with current job | 1135 | 52.5 | 334 | 21.9 | 1339 | 21.8 | |||

| Seeking different work | 82 | 3.8 | 53 | 3.5 | 130 | 2.1 | |||

| Do not work now, but want to work | 141 | 6.5 | 130 | 8.5 | 379 | 6.2 | |||

1 N: frequency, 2 %: percentage, 3 X2: Chi-square test, 4 H: Kruskal-Wallis test, p-value < 0.05.

3.6. Recognition Function

The results reflecting age and educational level that affect cognitive impairment are as follows: Looking at overall cognitive impairment, the elderly who were in the “current drivers” group had less precognitive impairment than the “past drivers but not current drivers” and “no driver’s license” groups. However, in the driving group, there were participants with lower than the recognition function cut-off points of 30 in the age group of 80 years or older (Table 5).

Table 5.

Precognitive function (MMSE-K).

| Characteristics | Education Level | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–3 Years | 4–6 Years | 7–12 Years | 13 Years or More | |||||||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |||

| Current drivers | Age | 65–69 | 30 (2) | 30 (1) | 27 (73) | 27 (40) | 27 (776) | 27 (272) | 28 (165) | 29 (39) |

| 70–74 | 30 (2) | 25 (1) | 26 (60) | 25 (14) | 26 (344) | 27 (40) | 29 (66) | 28 (5) | ||

| 75–79 | 27 (2) | 24 (1) | 25 (45) | 26 (7) | 27 (120) | 26 (9) | 26 (16) | 29 (2) | ||

| 80 over | 22 (3) | 16 (1) | 23 (15) | 23 (4) | 27 (30) | 6 (1) | 28 (10) | 30 (2) | ||

| Past but not current drivers | 65–69 | 26 (1) | 23 (1) | 24 (42) | 25 (16) | 25 (185) | 27 (126) | 24 (14) | 28 (15) | |

| 70–74 | 21 (5) | 25 (1) | 25 (71) | 26 (15) | 25 (249) | 27 (62) | 26 (32) | 27 (4) | ||

| 75–79 | 22 (11) | 25 (4) | 24 (117) | 26 (20) | 25 (211) | 25 (19) | 26 (29) | 25 (6) | ||

| 80 over | 20 (29) | 15 (4) | 23 (96) | 23 (9) | 24 (114) | 24 (11) | 25 (31) | 29 (2) | ||

| No driver’s license | 65–69 | 21 (6) | 23 (41) | 26 (36) | 25 (385) | 24 (141) | 26 (1097) | 26 (10) | 26 (37) | |

| 70–74 | 25 (9) | 22 (132) | 23 (94) | 24 (602) | 23 (147) | 25 (513) | 28 (8) | 25 (16) | ||

| 75–79 | 23 (14) | 21 (256) | 23 (113) | 23 (616) | 23 (106) | 24 (241) | 27 (9) | 24 (14) | ||

| 80 over | 22 (72) | 20 (514) | 22 (180) | 22 (627) | 21 (91) | 23 (129) | 26 (9) | 24 (5) | ||

3.7. Current Drivers

The degree of difficulty in driving was as follows: 24 people found it to be very difficult; 238 people stated that it was somewhat difficult; 352 people stated that it was just so; 859 people stated that it was not difficult at all; and 689 people stated that it was not at all. The difficulties experienced while driving were “eyesight impairment” in 236 people, “hearing impairment” in 22 people, “decreased reaction speed in arms and legs” in 82 people, “decreased judgment” (understanding road conditions such as intersections) in 151 people, and “slow speed” in 123 people.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The data for this study were obtained from the health and welfare data portal of the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs to identify the physical and mental status of the elderly who are currently driving. A total of 9,990 people took part in the survey in 2020. Choi stated that elderly drivers experiencing difficulties adapting to changes in driving conditions are aware of the driving risks, including deterioration in sight and hearing [11]. It has been shown that many elderly drivers choose to drive despite the deterioration in their sight and hearing, which is a result of their natural aging and can cause serious accidents. Lee also stated that elderly drivers’ ability to adapt to driving situations is related to the risk of traffic accidents, which means that the physical health of the elderly is highly correlated with their driving performance [19].

Aging is natural, but the deterioration of vision inevitably increases the risk of accidents associated with driving; hence, elderly drivers must accurately recognize their mental and physical conditions. Health status is highly correlated with the safety perception of driving. If the elderly are rewarded for good health status, [5] they will drive more cautiously. Previous studies also reported that elderly drivers become distracted while driving owing to the increased auditory processing load, which increases the risk of driving accidents owing to increased driving speed variability [11,12]. It has been recognized that the driving risk increases when the elderly drive [11]. In addition, complications that can lead to accidents and, consequently, cause social problems are also important when psychotic or cognitive impairment occurs in elderly drivers [5,11]. In reality, it is impossible to unconditionally ban the elderly from driving, but in particular, the elderly who have vision and hearing impairments should receive driving assistance through orthoses and treatment.

It was reported that the elderly who currently drive had a better subjective health status than those who did not. Among the “current drivers”, seven people had severe disabilities (grades 1–3), 44 had moderate disabilities (grades 4–6), 32 had physical disabilities, 11 had hearing impairments, three had visual impairments, and two had respiratory problems. At the time of the data investigation, most of the current diseases had been cured, but there were differences between the groups in the treatment status of diabetes and chronic diseases such as back pain, sciatica, pulmonary tuberculosis, and tuberculosis. The number of chronic diseases increased, resulting in the elderly not driving. In addition, for 28.0% of the respondents, bending, squatting, and kneeling movements were difficult, and for 19.5%, reaching for something higher than their head was difficult. Depression symptoms decreased as they drove, and cognitive function was better in the driving group than in the other groups, but it was also lower than the cut-off point for those over the age of 80. Among the elderly who are currently drivers, 12.0% said that they experienced difficulties while driving in terms of decreased vision, hearing loss, decreased arm/leg reaction speed, decreased judgment (understanding of road conditions, such as signals and intersections), and decreased sense of speed. In a study by Choi, elderly drivers were found to take drugs for hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia [11]. Also, regarding the economic activity results of elderly drivers, there is a significant difference between groups according to current drivers, drivers who have driven in the past, and those without a driver’s license. This means that driving and economic activities are significantly correlated, and drivers have a strong correlation with economic activity. In this study, diseases such as diabetes, lower back pain, and sciatica were significantly different from those in the other groups. These results suggest that elderly drivers are unaware of medical conditions that can negatively affect their driving. The findings of this study can facilitate the safety management of elderly drivers by better understanding their mental and physical status.

This study has some limitations. The results must be interpreted with caution, as the findings do not represent all elderly drivers in the Republic of Korea. Further, the findings do not reflect the actual driving situation. In addition, it was impossible to directly discuss the risk of driving due to neurological symptoms.

Acknowledgments

This study data was processed and used as raw data from the Health and Welfare Data Portal of the Korea Institute of Health and Social Affairs (https://data.kihasa.Re.kr/kihasa/) and was based on the data (National Statistics approval no. 117071). We accessed it on 20 June 2022.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-H.J., E.-Y.K., C.O. and J.K.; data curation, S.-H.J., E.-Y.K. and W.-J.C.; formal analysis, S.-H.J., E.-Y.K., S.-J.L., H.-J.S. and J.K.; funding acquisition, J.K.; investigation, E.-Y.K., S.-J.L. and J.K.; methodology, S.-H.J. and E.-Y.K.; project administration, W.-J.C. and J.K.; resources, S.-H.J. and H.-J.S.; software, E.-Y.K., S.-J.L., W.-J.C. and J.K.; supervision, J.K.; validation, S.-H.J., E.-Y.K., W.-J.C., C.O. and H.-J.S.; visualization, E.-Y.K.; writing—original draft, S.-H.J., E.-Y.K. and J.K.; writing—review and editing, W.-J.C., C.O. and J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by a Korea University Grant, Basic Science Research Program, through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (NRF-2022R1I1A1A01071220), and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. 2020R1A5A1018052).

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Korean Statistical Information Service (KOSIS), 2019. [(accessed on 5 October 2022)]. Available online: http://kosis.kr/statHtmlstatHtml/statHtml.do?or-Id=101&tblId=DT_1BPA002&checkFlag=N/

- 2.Baldock M.R., McLean J. Older Drivers: Crash Involvement Rates and Causes. Centre for Automotive Safety Research; Adelaide, Australia: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gagliardi C., Marcellini F., Papa R., Giuli C., Mollenkopf H. Associations of personal and mobility resources with subjective well-being among older adults in Italy and Germany. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;50:42–47. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park S.W., Park H.C., Yoo M.H., Lim S.I., Hwang E.J., Kim E.S., Choi K.I., Choi K.J., Lee D.J. Driving status, habits and safety of older drivers. J. Korean Acad. Rehabil. Med. 2010;34:570–576. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee S.E. Factors affecting traffic accident anxiety of older drivers. (JNCIST) J. Next-Gener. Converg. Inf. Serv. Technol. 2019;8:263–272. doi: 10.29056/jncist.2019.09.04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmed H.I., Mohamed E.E., Aly A.M. Effect of mobility on the quality of life among older adults in geriatric home at Makkah al-Mukarramah. Adv. Life Sci. Technol. 2014;17:39–50. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Traffic Accident Analysis System (TAAS) 2019. [(accessed on 5 October 2022)]. Available online: http://taas.koroad.or.kr/sta/acs/gus/selectOdsnDrverTfcacd.do?menuId=WEB_KMP_OVT_MVT_TAS_ODT/

- 8.Donorfio L.K.M., D’Ambrosio L.A., Coughlin J.F., Mohyde M. To drive or not to drive, that isn’t the question—The meaning of self-regulation among older drivers. J. Safety Res. 2009;40:221–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim D.H., Heo T.Y. Analysis on the auto accident risks of the old. Korean Soc. Transp. 2015;33:100–111. doi: 10.7470/jkst.2015.33.1.100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charlton J.L. Characteristics of older drivers who adopt self-regulatory driving behaviours. Transp Res. F. 2006;9:363–373. doi: 10.1016/j.trf.2006.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi S.Y. Analyzing driving risk self-perception characteristics of elderly drivers. J. Converg. Inf. Technol. 2020;10:223–231. doi: 10.22156/CS4SMB.2020.10.07.223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pachana N.A., Petriwskyj A.M. Assessment of insight and self-awareness in older drivers. Clin. Gerontol. 2006;30:23–38. doi: 10.1300/J018v30n01_03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Molnar L.J., Eby D.W., Kartje P.S., St Louis R.M.S. Increasing self-awareness among older drivers: The role of self-screening. J. Safety Res. 2010;41:367–373. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donorfio L.K.M., Mohyde M., Coughlin J., D’Ambrosio L. A qualitative exploration of self-regulation behaviors among older drivers. J. Aging Soc. Policy. 2008;20:323–339. doi: 10.1080/08959420802050975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ross L.A., Clay O.J., Edwards J.D., Ball K.K., Wadley V.G., Vance D.E., Cissell G.M., Roenker D.L., Joyce J.J. Do older drivers at-risk for crashes modify their driving over time? J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2009;64:163–170. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbn034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Factor R., Mahalel D., Yair G. The social accident: A theoretical model and a research agenda for studying the influence of social and cultural characteristics on motor vehicle accidents. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2007;39:914–921. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi S.Y., Lee J.S., Kim S.K., Cha T.H., Yoo D.H., Kim H. Developing a self-questionnaire SAFE-DR to evaluate driving ability of Korean elderly driver. Asia Life Sci. 2020;29:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meuleners L.B., Harding A., Lee A.H., Legge M. Fragility and crash over-representation among older drivers in Western Australia. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2006;38:1006–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheikh J.I., Yesavage J.A. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): Recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin. Gerontol. J. Aging Ment. Health. 1986;5:165–173. doi: 10.1300/J018v05n01_09. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Folstein M.F., Robins L.N., Helzer J.E. The Mini-Mental State Examination. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1983;40:812. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790060110016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kwon Y.C. Korean version of mini-mental state examination (MMSE-K) J. Korean Neurol. Assoc. 1989;1:123–135. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kang Y., NA D.-L., Hahn S. A validity study on the Korean Mini-Mental State Examination (K-MMSE) in dementia patients. J. Korean Neurol. Assoc. 1997;15:300–308. [Google Scholar]

- 23.LEE D.-Y., LEE K.-U., LEE J.-H., KIM K.-W., JHOO J.-H., YOUN J.-C., KIM S.-Y., WOO S.-I., WOO J.-I. A normative study of the mini-mental state examination in the Korean elderly. J. Korean Neuropsychiatr. Assoc. 2002;41:508–525. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.