Abstract

Background:

The Latinx population is the largest and fastest-growing segment of the U.S. While the vast majority of Latinx children are U.S.-born, over half are growing up in a family where they live with at least one foreign-born parent. Despite research showing that Latinx immigrants are less likely to experience mental, emotional, and behavioral (MEB) health issues (e.g., depression, conduct disorder, substance misuse), their children have one of the country’s highest rates of MEB disorders. To address the MEB health of Latinx children and their caregivers, culturally grounded interventions have been developed, implemented, and tested to promote MEB health. The purpose of this systematic review is to identify these interventions and summarize their findings.

Methods:

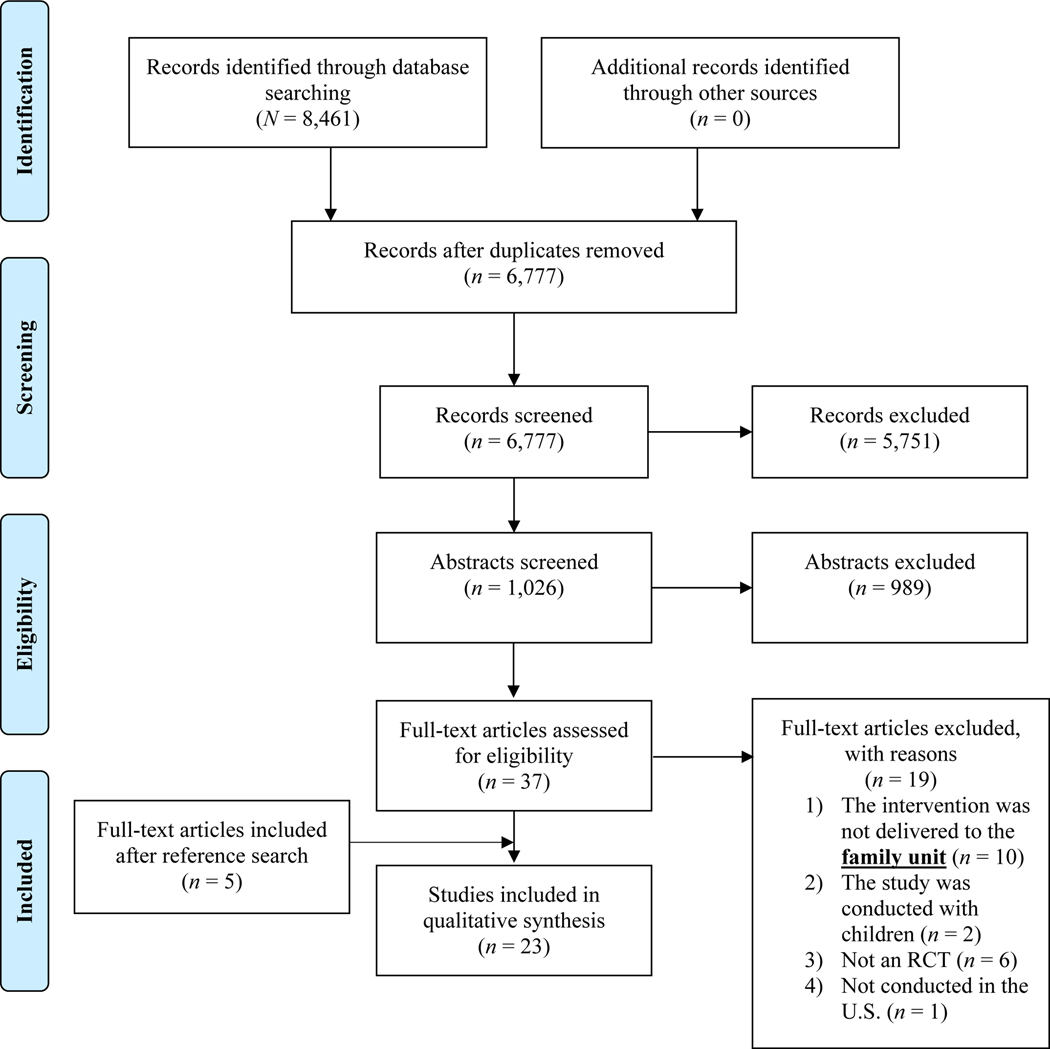

We searched PubMed, PsycINFO, ERIC, Cochrane Library, Scopus, HAPI, ProQuest, and ScienceDirect databases from 1980 through January 2020 as part of a registered protocol (PROSPERO) following PRISMA guidelines. Our inclusion criteria were randomized controlled trials of family interventions among a predominantly Latinx sample. We assessed the risk of bias in the included studies using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool.

Findings:

Initially, we identified 8,461 articles. After going through the inclusion criteria, 23 studies were included in the review. We found a total of 10 interventions, with Familias Unidas and Bridges/Puentes having the most information available. Overall, 96% of studies demonstrated their effectiveness in addressing MEB health, namely substance use, alcohol and tobacco use, risky sexual behaviors, conduct disorder, and internalizing symptoms among Latinx youths. Most interventions focused on improving parent-child relationships as the main mechanism to improve MEB health among Latinx youths.

Discussion:

Our findings show that family interventions can be effective for Latinx youths and their families. It is likely that including cultural values such as familismo and issues related to the Latinx experience such as immigration and acculturation can help the long-term goal of improving MEB health in Latinx communities. Future studies investigating the different cultural components that may influence the acceptability and effectiveness of the interventions are warranted.

Keywords: Latinx, Hispanic, immigrants, family interventions, mental health, behavioral health

Introduction

In the United States, there are nearly 60 million Latinx1 people, accounting for more than 18% of the total U.S. population (Noe-Bustamante & Flores, 2019). Although most of the Latinx population are born in the U.S., approximately 33% are foreign-born, originating from Latin America, Mexico, the Caribbean, and Central and South America (Noe-Bustamante & Flores, 2019). While the vast majority of Latinx children and youths are U.S.-born, over half of them are growing up in an immigrant family where they live with at least one foreign-born parent (Lopez et al., 2017; Lopez et al., 2018). Previous research has shown that complex factors such as immigration, cultural identity, poverty, and discrimination contribute to Latinx youths experiencing mental, emotional, and behavioral (MEB) health challenges (Ramirez et al., 2017; National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2009). In fact, approximately 22% of Latinx youths experience depressive symptoms and endure accumulated stress, a rate higher than any other minority group other than Native/Indigenous youths (Guzmán et al., 2009; Ramirez et al., 2017). A recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Survey indicated that 32.6% of Latinx students reported feelings of hopelessness, sadness, and a decrease in activities they previously enjoyed, compared to 27.2% of White and 24.7% of Black students (Arora et al., 2021; Ramirez et al., 2017). In addition, Latinx students reported higher rates of suicidal behavior, including ideation, plans, and attempts, than their White and Black counterparts (Avenevoli et al., 2013; Ramirez et al., 2017).

In addition to the high rates of MEB health issues experienced by Latinx youths, many Latinx families experience barriers when accessing MEB health services (Alegría et al., 2002), making it difficult to address and improve MEB health among Latinx youths. A recent study found that only 8% of Latinx caregivers indicated that their child had ever received MEB health services (Ramirez et al., 2017). Low utilization and premature termination rates have been identified as two factors associated with adverse mental health outcomes among Latinx youths (Kouyoumdjian et al., 2003). Explanations for low mental health utilization among Latinxs do not rest solely on individuals’ characteristics, such as limited English proficiency. Structural barriers such as anti-immigrant policies (Haley et al., 2020), limited ethnoracial and language-concordant providers (Jacquez et al., 2016; Luque et al., 2018), transportation (Parker, 2021), health insurance, and the high cost of mental health services (Ackert et al., 2021) are key to understanding the low service utilization among U.S. Latinxs (Haley et al., 2020; Kouyoumdjian et al., 2003).

With the increased numbers and MEB health challenges of Latinx youths in the U.S., it is pivotal for interventions to address and treat their needs. To address the MEB health needs of Latinx children, youths, and their caregivers, culturally grounded interventions have been developed, implemented, and tested to promote positive MEB health outcomes. The purpose of this systematic review is to provide an overview of the family interventions that have been developed, implemented, or culturally tailored to promote MEB health among Latinx youths and provide a summary of the outcomes. We specifically focus on family interventions, given the Latinx cultural value of familismo, which is the importance of family, and it is an integral value that has been demonstrated to be a beneficial and protective factor for Latinx youths (Bámaca-Colbert et al., 2012; Baumann et al., 2010; Cupito et al., 2015; Kuhlberg et al., 2010; Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2012; Peña et al., 2011; Stein et al., 2014).

For this study, we define family interventions as those where the nuclear family was engaged in the intervention by providing at least one session to the parents/caregivers and youths together. We define MEB disorders as those that encompass symptoms of depression and anxiety, conduct disorder, aggression, delinquency, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), substance use, tobacco use, and risky sexual behaviors. We encompass MEB disorders since they often co-occur. The research question guiding this systematic review is: What are the family interventions that have been implemented to promote mental health among Latinx youths?

Methods

We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines developed by Moher et al. (2009), and we followed the steps to conduct a systematic review developed by Liberati et al. (2009). The methodology, including the inclusion criteria, were specified in advance, and the systematic review protocol was registered with PROSPERO under registration number: CRD42019112389.

1.1. Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria of the studies in this review were the following: (a) Randomized Controlled Trials testing the effectiveness of a family intervention to improve MEB health among youths, (b) reported main effects of youths’ outcomes, (c) published between 1980 and 2020, (d) at least 50% of the sample was Latinx or the study presented disaggregated results by Latinx ethnicity, and (e) the study was conducted in the United States mainland. Below we provide a rationale and more information about our inclusion criteria.

Given that our research question focused exclusively on intervention implementation, identifying RCTs would allow us to address the research question, while also discussing the potential of these interventions. We included family interventions that aimed to improve MEB health among Latinx youths between 12 and 18 years of age. To be included in the review, the studies had to test the effectiveness of a family intervention, where at least one caregiver and one child received at least one intervention session together. The timeframe selected corresponds to increased Latin American immigration to the United States starting in the early 1980s (Budiman et al., 2020). We included interventions where at least 50% of the sample was Latinx because this percentage has been used in previous systematic reviews conducted with this population (Pineros-Leano et al., 2017), and it is based on the assumption that when at least half of the population in the sample is Latinx, the results are in part indicative of the effects the intervention would have for Latinx populations. Finally, we limited the scope of this review to the United States mainland given the paradoxical deterioration of MEB health with more time spent in the country (Vega & Sribney, 2011).

1.2. Search methods for identification of studies

The first author, in collaboration with a research assistant, conducted a structured, systematic search in the following seven databases: PubMed, PsycINFO, ERIC, Cochrane Library, Scopus, HAPI, and ScienceDirect. These databases were identified with the help of a librarian. The following restrictions were applied to the search in all databases: (a) peer reviewed articles published between 1980 and 2020, (b) containing specific terms anywhere in the text, and (c) published in English or Spanish. All possible combinations of the following terms were used in the search: “family intervention” OR “family program” OR “family training” OR “parenting intervention” OR “parenting program” OR “parenting training” OR “family-based intervention” OR “family-based program” OR “family-based training” AND “Latin*” OR “Latinx” OR “Hispanic” OR “Spanish.” The results of the search were exported to EndNote™, where duplicates were removed. The first author went through all the titles and deleted those that were not related to family interventions among Latinx families. Next, each abstract was reviewed independently by two investigators using the inclusion criteria. Studies that did not match the inclusion criteria were deleted. When there was disagreement between reviewers regarding the articles to keep based on the abstracts, the article was kept for a full-text review. The next step consisted of a full-text revision of studies. In this step, two investigators independently read the full text of the selected articles and kept the ones that fulfilled the inclusion criteria. In case of disagreement, the reviewers convened and discussed the article until reaching an agreement on whether the study met inclusion criteria. A reference search was then conducted on the studies that met inclusion criteria to ensure that any studies that could have been missed by the systematic search were included in the review.

1.3. Data extraction

Characteristics of the study, including the name of the intervention, treatment modality, primary and secondary outcomes, sample size, age of parents and youths, ethnoracial backgrounds of participants, measurements, timepoints, and results, were entered in an MS Excel database. A research assistant extracted all outcomes, and the first author validated the extractions.

1.4. Types of outcome measures

We included studies where the primary outcome of the family intervention was to improve MEB health among Latinx youths. MEB health encompassed symptoms of depression and anxiety, conduct disorder, aggression, delinquency, ADHD, substance use, tobacco use, and risky sexual behaviors.

1.5. Risk of bias assessment

We used the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for Randomized Trials (Higgins et al., 2011). This assessment was conducted separately by two reviewers. Any disagreements were discussed until reaching an agreement. This tool is designed to help reviewers assess elements of rigor in randomized trials. Specifically, this tool draws attention to (a) randomization of participants, (b) assignment to interventions, (c) incomplete outcome data (missingness), (d) bias in outcome measurement, and (e) bias in reporting of results. Each domain includes subdomains to better assess biases on the studies. We assessed the quality of evidence using the recommendations of low risk, high risk, or unclear. According to the protocol, any unclear data or data not provided may indicate a source of bias (Higgins et al., 2011). Also, if any subdomain demonstrates biases, this will likely impact the overall domain score and the overall study score. To better visualize the risk of bias, we created a visualization graph using Robvis (McGuinness & Higgins, 2020).

Results

We identified 8,461 initial records through the different databases we searched (Figure 1). After duplicates were deleted, we screened 6,777 titles. We screened 1,026 abstracts and excluded 989 for a full-text review of 37 articles. We then excluded 19 articles because: (a) the intervention was not delivered to the family unit (n = 10), (b) the study was conducted with children (under age 12), (c) the study was not an RCT (n = 6), and (d) the study was conducted outside of the U.S. (n = 1). A reference search of the remaining18 studies resulted in five more studies being included that were not identified in the original search. This resulted in 23 studies included in the review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram

2.1. Study characteristics

To systematically identify, integrate, and summarize the characteristics of the studies, we conducted content analysis of the data extracted from each study (Saldaña, 2015). Most studies were conducted among Latinx families exclusively (n = 17, 74%; Table 1). Among those, several interventions targeted immigrant families. Sample sizes ranged from 28 (Santisteban et al., 2011) to 746 youths and their families (Lee et al., 2019). All studies included youths and at least one caregiver, who was usually the mother. Almost all studies reported the mean age of participants (n = 21), one reported age range (Santisteban et al., 2011), and one provided information about participants’ grade level (Jensen et al., 2014). Regarding the gender of the youths, 39% of studies had a similar number of males and females (n = 9). Among the studies that did not have gender balance, all of them had more male participants, except for one, which recruited more female participants (Milburn et al., 2012). Very few studies reported the age of the parents/caregivers. We also found that most studies (n = 15; 65%) were conducted in Miami-Dade County, Florida, which has a large Latinx population.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Author and year |

Name of the intervention | Total sample (N) | Age of youths (Mean, SD) | Female (%) | Study population+ | Country of origin of Latinx families* | Geographic setting of study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Cordova et al. (2012) | Familias Unidas | 213 youths and their primary caregivers | 13.8,0.8 | 36.2 | Only Latinx families (44% of youths foreign-born) | Honduras (27%) Cuba (20%) Nicaragua (16%) |

Miami-Dade County, Florida |

| Elder et al. (2002) | Sembrando Salud | 660 youths and 1 primary caregiver | 13.4, 1.1 | 49.0 | Only Latinx families | Mexico | San Diego County, California |

| Estrada et al. (2019) | eHealth Familias Unidas | 230 youths and their primary caregivers | 13.6,0.7 | 37.0 | Only Latinx (44% of youths foreign-born) | Cuba (20%) Honduras (6%) Colombia (3%) |

Miami-Dade County, Florida |

| Estrada et al. (2015) | Brief Familias Unidas | 160 youths and their primary caregivers | 15.3,0.9 | 48.7 | Only Latinx families | Cuba (37%) Honduras (12%) Nicaragua (10%) |

Miami-Dade County, Florida |

| Gonzales et al. (2012) | Bridges/Puentes | 516 Mexican American youths and their primary caregivers | 12.3,0.5 | 50.8 | Mexican American families (19% of youths foreign-born) | Mexico | Phoenix, Arizona |

| Gonzales et al. (2018) | Bridges/Puentes | 420 Mexican American youths and their primary caregivers | 17.9,0.6 | 51.2 | Mexican American families (19% of youths foreign-born) | Mexico | Phoenix, Arizona |

| Hogue et al. (2015) | Usual Care Family Treatment | 205 youths and their primary caregivers | 15.7, 1.5 | 48.0 | Latinx (59%), Black (21%), More than one race (15%), and Other race (6%) families | Not specified | New York, New York |

| Jensen et al. (2014) | Bridges/Puentes | 494 youths and their primary female caregivers | Seventh Graders^ | 50.0 | Mexican American families (19% of youths foreign-born) | Mexico | Phoenix, Arizona |

| Lee et al. (2019) | Familias Unidas | 746 youths and their primary caregivers | 13.9,0.7 | 48.0 | Only Latinx families (45% of youths foreign-born) | Not specified | Miami-Dade County, Florida |

| Liddle et al. (2018) | Multidimensional Family Therapy (MDFT) | 113 youths and their primary caregivers | 15.36, 1.1 | 25.0 | Latinx (68%), Black (18%), White (13%) families | Not specified | Miami, Florida |

| Litrownik et al. (2000) | Sembrando Salud | 660 youths and 1 primary caregiver | 13.4, 1.1 | 49.0 | Latinx migrant families | Mexico | San Diego County, California |

| Milburn et al. (2012) | Support to Reunite, Involve and Value Each Other (STRIVE) | 151 youths and their primary caregivers | 14.8, 1.4 | 66.2 | Homeless youths and their families (62% Latinx, 21% Black, 11% White, and 7% other race) | Not specified | Los Angeles and San Bemadino counties, California |

| Pantin et al. (2003) | Familias Unidas | 167 youths and at least 1 primary caregiver | 12.4, 0.8 | 38.6 | Only Latinx families (49% of youths foreign-born) | South American countries (17%) | Miami-Dade County, Florida |

| Pantin et al. (2009) | Familias Unidas | 213 youths and their primary caregivers | 13.8,0.8 | 36.2 | Latinx families (44% of youths foreign-born) | Honduras (27%) Cuba (20%) Nicaragua (16%) |

Miami-Dade County, Florida |

| Prado, Cordova, et al. (2012) | Familias Unidas | 242 youths and their primary caregivers | 14.7, 1.4 | 35.5 | Only Latinx families (35% of youths foreign-born) | Dominican Republic (7%) | Miami-Dade County, Florida |

| Prado et al. (2013) | Familias Unidas | 213 youths and their primary caregivers | 13.8,0.8 | 36.2 | Only Latinx families (44% youths foreign-born) | Honduras (27%) Cuba (20%) Nicaragua (16%) |

Miami-Dade County, Florida |

| Prado et al. (2007) | Familias Unidas and Parent-Preadolescent Training for HIV Prevention (PATH) | 266 youths and their primary caregivers | 13.4,0.7 | 51.9 | Only Latinx families (60% of youths foreign-born) | Cuba (40%) Nicaragua (25%) Honduras (9%) |

Miami-Dade County, Florida |

| Prado, Pantin, et al. (2012) | Familias Unidas | 242 youths and their primary caregivers | 14.7, 1.4 | 35.5 | Only Latinx families (35% of youths foreign-born) | Cuba (25%) Nicaragua (9%) Honduras (16%) Dominican Republic (7%) |

Miami-Dade County, Florida |

| Robbins et al. (2008) | Structural Ecosystem Therapy (SET) | 190 youths and their family members | 15.6, 1.1 | 14.2 | Latinx (60%) and African American (40%) families | Not specified | Miami-Dade County, Florida |

| Santisteban et al. (2003) | Brief Strategic Family Therapy (BSFT) | 126 youths and their family members | 15.6, n/s | 25.0 | Only Latinx families | Cuba (51%) Nicaragua (14%) Colombia (10%) Puerto Rico (6%) |

Miami-Dade County, Florida |

| Santisteban etal. (2017) | Culturally Informed and Flexible Family-Based Treatment for Youth (CIFFTA) | 80 youths and their family members | 13.6, 1.2 | 43.7 | Latinx (80%) and Black (20%) families | Not specified | Miami-Dade County, Florida |

| Santisteban et al.(2011) | Culturally Informed and Flexible Family-Based Treatment for Youth (CIFFTA) | 28 youths and their family members | 14–17^ | n/s | Only Latinx families | Not specified | Miami-Dade County, Florida |

|

Smokowski and Bacallao (2008)

|

Entre Dos Mundos/Between Two Worlds (EDM) | 88 youths and at least 1 primary caregiver | 14.2, 1.8 | 54.0 | Latinx immigrant families (100% of youths foreign-born) | Mexico (66%) El Salvador (7%) Colombia (15%) |

Urban, rural, and mid-sized cities in North Carolina |

Note:

Represents the predominant countries of birth of foreign-born participants.

Foreign-born populations are reported whenever they are available from the original study.

The mean age was not specified

Most studies focused on preventing or reducing drug misuse (n = 16; 68%), followed by conduct disorders (n = 12; 52%), followed by alcohol use (n = 10; 43%), risky sexual behaviors (n = 8; 34%), tobacco use (n = 7; 30%), and depression and/or anxiety symptoms (n = 6; 26%; Table 1). Most studies (n = 19; 83%) aimed to target more than one outcome.

2.2. Treatment modality

Most interventions were delivered in a group format, either to the parents or the adolescents. The total number of sessions ranged from five (Milburn et al., 2012) to 32 (Santisteban et al., 2011). Sessions conducted with the entire family ranged from one (Estrada et al., 2015) to 32 (Santisteban et al., 2011). Most interventions had a set number of sessions (n = 16; 70%), whereas 30% were based on clinical severity (Hogue et al., 2015; Liddle et al., 2018; Robbins et al., 2008; Santisteban et al., 2003) or had a set amount of time within which several sessions were delivered (Cordova et al., 2012; Pantin et al., 2003; Santisteban et al., 2017). Most studies used a manualized treatment, except for the interventions by Hogue et al. (2015) and Liddle et al. (2018), where there was no set limit on the number of sessions the family could attend.

A total of seven studies were delivered at schools (Elder et al., 2002; Estrada et al., 2015; Gonzales et al., 2012; Gonzales et al., 2018; Jensen et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2019; Litrownik et al., 2000), four at community agencies (Elder et al., 2002; Hogue et al., 2015; Knox et al., 2011; Smokowski & Bacallao, 2008), and two were online (Estrada et al., 2019; Santisteban et al., 2017). Most studies (n = 12; 52%) also included a component that was delivered at home (Cordova et al., 2012; Estrada et al., 2015; Gonzales et al., 2012; Gonzales et al., 2018; Jensen et al., 2014; Milburn et al., 2012; Pantin et al., 2003; Pantin et al., 2009; Prado, Cordova, et al., 2012; Prado et al., 2013; Prado et al., 2007; Prado, Pantin, et al., 2012). Three studies used a pre-posttest design only (Litrownik et al., 2000; Santisteban et al., 2003; Smokowski & Bacallao, 2008). The other 20 studies used a pre-posttest follow-up design. Follow-up time points ranged from a 2-months postbaseline (Liddle et al., 2018) to a 5-years postbaseline (Gonzales et al., 2018; Jensen et al., 2014).

2.3. Risk of Bias

Overall, most articles were deemed to have a low risk of bias (see Figure 2), and five (22%) were considered to have moderate risk of bias (Liddle et al., 2018; Robbins et al., 2008; Santisteban et al., 2003; Santisteban et al., 2011; Smokowski & Bacallao, 2008). A moderate risk of bias indicates that there could have been some issues in the implementation or design of the trial in at least one domain, which should be considered when interpreting the results. Below we provide an explanation of the specific reasons that yielded five studies as having a moderate risk of bias.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias assessment tool (McGuinness & Higgins, 2020)

Regarding the different domains, the method for randomizing participants into the intervention and control conditions was reported acceptable for most of the studies (n = 21). The two studies that were deemed to have some concerns in this areas were the studies by Robbins et al. (2008) and Santisteban et al. (2011), given that although participants were randomized to the intervention and control conditions, there were significant differences at baseline between the experimental and the control groups, which could potentially suggest an issue in the process of randomization (Higgins et al., 2011). The studies by Liddle et al. (2018) and Smokowski and Bacallao (2008) were deemed to have some concerns regarding domain 2, which was related to the assignment to interventions. These studies were deemed to have some concerns in this domain because although participants had been randomized to the intervention condition, they were aware of the condition they had been randomized to, which could increase the risk for group contamination (Higgins et al., 2011). Also, these studies did not indicate whether steps had been taken to address the effect of intervention assignment and/or potential group contamination. Under this domain we also noticed that a few studies failed to indicate whether people who were delivering the intervention were blinded to the group to which participants had been assigned. Future studies should add as much information as possible regarding randomization processes and indicate whether the study is double- or single-blinded. Finally, the study by Santisteban et al. (2003) was deemed to have some concerns in domain 4, which is related to bias in outcome measurement, given that only youths were included in the control condition, rather than the family, which made the conditions and the measurements different between groups. An issue that we encountered that was not part of the risk of bias assessment, but one that is important to consider, was that studies lacked a clinical trial protocol, making it difficult to ascertain whether the analytical methodology differed from the analysis originally planned.

2.4. Effectiveness of interventions

In this section we will discuss each intervention and its outcomes separately. Through our search, we found a total of 10 different family interventions, with Familias Unidas being the one with the most amount of information available. Overall, 22 of the 23 studies demonstrated significant differences between the intervention and the control groups (see Table 2; Cordova et al., 2012; Estrada et al., 2019; Estrada et al., 2015; Gonzales et al., 2012; Gonzales et al., 2018; Hogue et al., 2015; Jensen et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2019; Liddle et al., 2018; Litrownik et al., 2000; Milburn et al., 2012; Pantin et al., 2003; Pantin et al., 2009; Prado, Cordova, et al., 2012; Prado et al., 2013; Prado et al., 2007; Prado, Pantin, et al., 2012; Robbins et al., 2008; Santisteban et al., 2003; Santisteban et al., 2017; Santisteban et al., 2011; Smokowski & Bacallao, 2008).

Table 2.

Summary of intervention effectiveness in addressing target outcomes

| Author and year | Name of the intervention | Was the intervention effective in addressing the target outcomes? | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Alcohol use |

Tobacco use |

Drug use |

Risky sexual behavior | Depression and/or anxiety |

Externalizing symptoms |

||

|

| |||||||

| Cordova et al. (2012) | Familias Unidas | Yes* | No | ||||

| Elder et al. (2002) | Sembrando Salud | No | No | ||||

| Estrada et al. (2019) | eHealth Familias Unidas | Yes | Yes | No | |||

| Estrada et al. (2015) | Brief Familias Unidas | No | No | No | Yes | ||

| Gonzales et al. (2012) | Bridges/Puentes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Gonzales et al. (2018) | Bridges/Puentes | Yes | |||||

| Hogue et al. (2015) | Usual Care Family Treatment | No | No | Yes | Yes | ||

| Jensen et al. (2014) | Bridges/Puentes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Lee et al. (2019) | Familias Unidas | Yes | |||||

| Liddle et al. (2018) | Multidimensional Family Therapy (MDFT) | Yes | No | Yes | |||

| Litrownik et al. (2000) | Sembrando Salud | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Milburn et al. (2012) | Support to Reunite, Involve and Value Each Other (STRIVE) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | ||

| Pantin et al. (2003) | Familias Unidas | Yes | |||||

| Pantin et al. (2009) | Familias Unidas | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Prado, Cordova, et al. (2012) | Familias Unidas | Yes* | No | Yes* | Yes | ||

| Prado et al. (2013) | Familias Unidas | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | |

| Prado et al. (2007) | Familias Unidas and Parent-Preadolescent Training for HIV Prevention (PATH) | No | Yes | Yes | No | ||

| Prado, Pantin, et al. (2012) | Familias Unidas | Yes | |||||

| Robbins et al. (2008) | Structural ecosystem therapy (SEM) | Yes* | |||||

| Santisteban et al. (2003) | Brief Strategic Family Therapy (BSFT) | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Santisteban et al.(2017) | Culturally Informed and Flexible Family-Based Treatment for Adolescents (CIFFTA) | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Santisteban et al.(2011) | Culturally Informed and Flexible Family-Based Treatment for Adolescents (CIFFTA) | Yes | No | ||||

| Smokowski and Bacallao (2008) | Entre Dos Mundos/Between Two Worlds (EDM) | Yes | |||||

Note: Externalizing symptoms include: conduct disorder, delinquency, aggressive behavior, and ADHD. Cells left blank indicate the intervention did not target outcomes.

Indicates the intervention was only effective for a specific subsample (e.g., only U.S.-born).

2.4.1. Familias Unidas

Familias Unidas is the intervention with the most trials available and one that has shown to be effective in addressing MEB health among Latinx youths. In our review, 10 out of 23 studies (43%) tested the effectiveness of Familias Unidas (Cordova et al., 2012; Estrada et al., 2019; Estrada et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2019; Pantin et al., 2003; Pantin et al., 2009; Prado, Cordova, et al., 2012; Prado et al., 2013; Prado et al., 2007; Prado, Pantin, et al., 2012). Familias Unidas was developed specifically for Latinx families using a socioecological framework, and it aims to target several socioecological levels to promote family cohesion and parental investment (Pantin et al., 2003).

We observed several variations on the implementation and outcome effectiveness of Familias Unidas. The earliest trial of Familias Unidas did not have a set number of sessions (Pantin et al., 2003), making it difficult to assess intervention dosage. This early trial (Pantin et al., 2003) found that youths in the intervention group showed a steady decline in behavior problems, compared to a more disorganized pattern in the control group, evidenced by an increase between the 3- and 6-months postbaseline and a sharp decrease at the 9-months postbaseline. The study also found that parental investment partially mediated the association between the intervention and youths’ behavior problems.

Later trials of Familias Unidas streamlined the number of group and family sessions and established the duration of the sessions. For instance, the Familias Unidas trial by Pantin et al. (2009) and Prado et al. (2013) consisted of nine 2-hour group sessions and ten 1-hour home visits. The results from Pantin et al. (2009) found significant intervention effectiveness on substance use and condom use among youths in Familias Unidas, compared to the control group. The study also found that parents who received Familias Unidas reported greater improvements in family functioning, compared to parents in the control condition. The study by Prado et al. (2013) investigated whether the degree of family risk influenced intervention effectiveness. They found that the effectiveness of the intervention varied based on the level of ecodevelopmental family risk (Prado et al., 2013). The intervention was effective for youths with high ecodevelopmental family risk by reducing externalizing disorders and substance use. However, the intervention did not show effectiveness among youths with low and moderate ecodevelopmental family risk. Similarly, the study by Cordova et al. (2012) investigated whether the results of Familias Unidas varied by nativity status. The study found that only U.S.-born youths who were part of the intervention had lower alcohol use, compared to youths in the control group. The study by Lee et al. (2019) investigated whether discrepancies in positive parenting (i.e., parents’ and youths’ ratings of positive parenting) across time impacted substance use at the 30-month follow-up. The results demonstrated that discrepancies in positive parenting decreased over time among participants in the intervention group, compared to the control group, which in turn led to a reduction in substance use at the 30-month follow-up (Lee et al., 2019).

There were other variations in the Familias Unidas intervention. The trial by Prado et al. (2007) consisted of 15 parent group sessions, eight home visits, and two parent-adolescent multifamily group sessions. In this study it was found that, over time, youths who participated in Familias Unidas and PATH (a parent-preadolescent training for HIV prevention) were less likely to smoke and use drugs, compared to youths in the control groups. The study also found that family functioning improved in the Familias Unidas and PATH, compared to the control groups, where family functioning decreased over time (Prado et al., 2007).

The intervention in the Prado, Cordova, et al. (2012) and Prado, Pantin, et al. (2012) trial consisted of eight 2-hour parent group sessions and four 1-hour family sessions delivered over 3 months. The family sessions were delivered at home. Findings from the 6-month postbaseline assessment indicated that youths in the intervention group reported an increase in responsible sexual behavior (e.g., consistent condom use, fewer sexual partners in the past 90 days), compared to youths in the control condition (Prado, Pantin, et al., 2012). The study also found that family functioning improved among parents in the Familias Unidas group compared to parents in the control condition (Prado, Pantin, et al., 2012). Findings from the same trial (Prado, Cordova, et al., 2012), but at the 12-month postbaseline, indicated that youths who had been part of Familias Unidas had lower substance use and were less likely to be diagnosed with alcohol dependence, compared to youths in the control group. The study also found that the intervention was more effective in reducing alcohol dependence among youths whose parents had low levels of social support and in reducing past 90-day illicit drug use among youths whose parents had high levels of parental stress. The study also found that youths in the intervention group were less likely to have sex under the influence, compared to youths in the control group (Prado, Cordova, et al., 2012).

A more recent version of Familias Unidas tested the effectiveness of a brief version (Estrada et al., 2015), which consisted of five 2-hour parent group sessions and one 1-hour home visit. The study found that compared to the control group, youths who were in the Familias Unidas group had lower sexual initiation rates. The study also found that youths who were 15 years of age or younger in the intervention group were less likely to engage in unsafe sex compared to older youths. There were no differences between groups on substance, alcohol, or tobacco use. However, it was found that girls in the intervention group were less likely to initiate substance use and alcohol consumption than boys (Estrada et al., 2015). The study also found higher scores on positive parenting among youths in the intervention group, compared to the control group, but no differences were found in communication or parental involvement. Further analysis indicated that youths in the intervention group who reported low- to moderate-parental involvement were less likely to use illicit drugs than those who reported high-parental involvement (Estrada et al., 2015).

Finally, an online version of Familias Unidas has been developed (Estrada et al., 2019). The eFamilias Unidas consists of eight online recorded sessions and four parent-adolescent family sessions, which are delivered virtually through video call/web conference (Estrada et al., 2019). Results from the eFamilias Unidas trial showed a decrease in marijuana and prescription drug use as well as stable inhalant use in the intervention group, compared to an increased use of these substances in the control group at the 12-month postbaseline. There was also a decrease in tobacco consumption in the intervention group over time, compared to no consumption change in the control group. Finally, the study found that eFamilias Unidas improved overall family functioning (Estrada et al., 2019).

2.4.2. Bridges/Puentes

Bridges/Puentes is the next intervention with the most amount of information. Three out of 23 studies (13%) investigated the effectiveness of Bridges/Puentes. Bridges/Puentes was developed to help Mexican American youths navigate the transition from middle to high school (Dillman Carpentier et al., 2007; Gonzales et al., 2012). Bridges/Puentes uses an ecodevelopmental framework, “which recognizes that developing youth need to adapt to multiple social contexts simultaneously, including families, peers, neighborhoods, and schools, as well as unique cultural factors, such as immigration and acculturation” (Gonzales et al., 2012, p. 2). The intervention consists of nine weekly sessions for youths and parents delivered at schools, where during the first 75 minutes youths and the parents have simultaneous separate sessions, and during the last 45 minutes youths and parents participate in the session together. The intervention also offers two home visits.

Results from the 1-year follow-up (Gonzales et al., 2012) indicated that compared to the control group, youths in the intervention group had lower levels of substance use, fewer internalizing and externalizing symptoms, and improved school discipline and grades. However, externalizing symptoms were particularly improved among English-speaking youths, compared to Spanish-speaking youths, in which externalizing behaviors went up. The study by Jensen et al. (2014) tested the effectiveness of the intervention through a 5-year follow-up. The study found that compared to the control group, youths in the intervention group had significantly lower levels of mother-youth conflict, which in turn were associated with fewer youths experiencing internalizing and externalizing symptoms, substance use, and internalizing disorder diagnoses. The study by Gonzales et al. (2018) also tested the effectiveness of the intervention 5 years postintervention, particularly on alcohol outcomes, and found that youths in the intervention group were less likely to have an alcohol use disorder diagnosis, compared to those in the control group. Results indicated that the intervention was particularly effective for youths who had already started drinking at baseline since the intervention suggested decreased alcohol consumption and drunkenness, compared to youths who had abstained from using alcohol at baseline.

2.4.3. Sembrando Salud

Two out of 23 studies (9%) investigated the effectiveness of Sembrando Salud (Elder et al., 2002; Litrownik et al., 2000). Sembrando Salud is a community-based alcohol and tobacco prevention intervention developed for low socioeconomic status Latinx youths and their families. Sembrando Salud uses a stress and coping framework where the individual and situational factors are considered and addressed. The intervention consisted of eight 2-hour sessions, delivered weekly, where parents joined the youths for three of these sessions. Results from the postintervention trial assessment indicated that youths from the intervention group were less likely to use tobacco and alcohol, compared to youths from the control group (Litrownik et al., 2000). However, significant findings were limited to youths who were from smaller households. Results from the same trial but from the 2-year follow-up assessment found no differences in smoking or drinking between the control and the intervention groups (Elder et al., 2002).

2.4.4. Culturally Informed and Flexible Family-Based Treatment for Adolescents (CIFFTA)

Two studies (9%) used the CIFFTA intervention. CIFFTA is based on Structural Family Therapy, with added modules that are of relevance to Latinx families. CIFFTA is implemented twice per week in an individual format (e.g., individual family) by family therapists for 16 weeks. CIFFTA is delivered in a therapist’s office. Based on family need, some sessions are delivered to the family unit, other sessions are delivered only to the youths, and other sessions are delivered only to the caregiver/s. Results from the 8-month follow-up trial assessment demonstrated that youths in the intervention group decreased their drug use, particularly of marijuana, compared to youths in the control group (Santisteban et al., 2011). The study also found that youths who were part of the CIFFTA group reported higher levels of positive parenting and involvement, compared to youths in the control condition (Santisteban et al., 2011). A larger trial of CIFFTA demonstrated that at the 18-week postbaseline, youths in the intervention group demonstrated improvements on externalizing behaviors, namely conduct disorder and socialized aggression, and also on internalizing behaviors, compared to the control group (Santisteban et al., 2017).

2.4.5. Usual Care Family Treatment

One study (4%) tested the effectiveness of using usual care family treatment (UC-FT), which consisted of structural-strategic family therapy as the usual care provided to families (Hogue et al., 2015). This was not a manualized intervention, and as such, there was not a set number of sessions. The intervention was conducted in outpatient clinical settings. The UC-FT intervention was delivered in an individual format (e.g., individual family), and 75% of the sessions were joined by the youths. Families attended an average of 8.3 sessions (SD = 9.9). Results from data gathered at baseline, 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-ups indicate that there were significant declines in externalizing and internalizing symptoms over time, compared to youths in the control group. This study found more significant decreases in delinquency and substance use among youths in the intervention group who used substances at baseline, compared to those in the control group (Hogue et al., 2015).

2.4.6. Multidimensional Family Therapy (MDFT)

One study (4%) used MDFT, which is an outpatient, family-based treatment that provided an average of 3.3 weekly hours of contact (SD = 1.7) between the therapist and the family, the parent, and the youth (Liddle et al., 2018). The intervention was provided in an academic setting (i.e., University of Miami). On average, the adolescent received a total of 24.7 hours of therapy, the parents received 8.4 hours, and the family unit received 37.8 hours. Therapy lasted between 6 and 9 months depending on the needs of the participants. Compared to youths in residential treatment (the control condition), participants who received MDFT were less likely to use substances, to engage in delinquent behavior, and to have substance use problems at the18-month postbaseline. However, no differences were found in mental health symptoms by group.

2.4.7. Support to Reunite, Involve, and Value Each Other (STRIVE)

One study (4%) used STRIVE, which is a manualized intervention based on cognitive-behavioral therapy principles and developed to improve conflict resolution skills between families. The intervention was delivered at home, and it consisted of five weekly family sessions, where each session lasted between 1.5 to 2 hours. The intervention was designed specifically for youths who had runaway episodes (Milburn et al., 2012). Results from the baseline, 3-, 6- and 12-month postbaseline assessments indicated that youths in the intervention group were significantly less likely to use alcohol and hard drugs, and to engage in delinquent behaviors, compared to youths in the control group. However, there were no differences by group in whether the youths had been sexually active, had unprotected sex, or in the frequency of sexual activity (Milburn et al., 2012).

2.4.8. Brief Strategic Family Therapy (BSFT)

One study (4%) used the intervention BSFT initially developed by Szapocznik (2003), which uses principles from structural and strategic family therapy, positing that maladaptive family interactions are the root of youths’ symptomatology (Santisteban et al., 2003). BSFT aims to restructure and transform family functioning in an effort to address youths’ problems. BSFT consists of 4–20 weekly sessions with all family members involved in childrearing, and it is delivered in a clinical research setting. Each session lasts approximately 1 hour. The number of sessions is based on clinical severity. In the BSFT trial, families received an average of 11.2 sessions (SD = 3.8). A pre-posttest analysis of the intervention showed that the treatment group had significantly fewer behavior problems posttreatment, particularly in terms of conduct disorder and socialized aggression, compared to participants in the control group (Santisteban et al., 2003). The results also demonstrated a decrease in marijuana consumption among youths in the treatment group, compared to those in the control group. Family functioning also improved significantly in the treatment group posttreatment but not in the control group.

2.4.9. Structural Ecosystem Therapy (SET)

One study (4%) used the intervention SET, which is a manualized family intervention that uses an ecological framework to address drug use among youths (Robbins et al., 2008). SET uses the family components from BSFT but adds ecological components that include working with the ecologic system of a youth (e.g., peers), tracking the ecological system of a youth, reframing problems, and restructuring relationships within a youth’s ecology. SET consists of 12–16 family sessions and 12 ecosystemic therapy sessions, which include family members and other people who are part of a youth’s social ecology (e.g., peers). The intervention was delivered at locations agreed upon with the family, including home and school. In the SET trial (Robbins et al., 2008), families received an average of 22.4 sessions (SD = 13.4), and Latinx families received significantly more sessions than Black families. Results from the baseline, 3-, 6-, 12-, and 18-month follow-ups indicated that SET was significantly more effective than the control and the family process-only condition by reducing drug use over time (Robbins et al., 2008).

2.4.10. Entre Dos Mundos (EDM)

One study (4%) used the Entre Dos Mundos/Between Two Worlds intervention. EDM is an intervention that uses an acculturation stressor framework, and the purpose is to provide bicultural skills training to address problematic family relationships (Smokowski & Bacallao, 2008). EDM is delivered over eight sessions, and it specifically targets Latinx immigrant youths. EDM is delivered in a multifamily-group format (Smokowski & Bacallao, 2008). As part of the intervention, parents and youths join multifamily group sessions where they discuss acculturation stressors in an effort to improve the relationship between parents and youths. The results from the study indicated that youth aggression, oppositional defiant behavior, attention problems, and ADHD went down after the intervention (Smokowski & Bacallao, 2008). Also, higher levels of bicultural identity and family adaptability were found. No statistically significant differences were found between the two delivery formats (action-oriented EDM skills training group and unstructured EDM support groups), demonstrating that different implementation formats could provide similar outcomes. Finally, a dosage effect was found; parents who attended four sessions or more reported significantly lower aggression and oppositional defiant behavior and higher bicultural identity and bicultural support among their youths than parents who attended fewer sessions (Smokowski & Bacallao, 2008).

Discussion

This review synthesized information from randomized controlled trials of family interventions to improve mental health among Latinx youths. Our results show that most interventions for Latinx families were effective in preventing or reducing MEB health issues, namely substance use, alcohol and tobacco use, risky sexual behaviors, conduct disorder, and internalizing symptoms, among Latinx youths. Our results also suggest that targeting the family, improving communication, and reducing conflict are some of the mechanisms that can help promote Latinx youths’ MEB health.

Given that almost half of U.S. Latinx children are growing up in immigrant families, interventions that understand the centrality of the family, as well as work with caregivers and the youths simultaneously, can be particularly beneficial. Previous studies with Latinx populations have consistently shown the importance of familismo and have found that focusing on family cohesiveness and positive family relationships can promote Latinx MEB health (Baumann et al., 2010; Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2012; Peña et al., 2011). Seminal work dating back to the 1980s demonstrated that working with the family unit can be a highly successful tool when working with Latinx families (Szapocznik et al., 1980; Szapocznik et al., 1989). Our systematic review further demonstrates the importance of familismo when working with Latinx families, and it reiterates that interventions with Latinx populations should continue developing and working with the family unit.

Despite the effectiveness of the studies found in our review, we did find substantial heterogeneity regarding modes of intervention delivery, number of sessions, and outcomes measured. We found that not all interventions were manualized or had a set number of sessions; instead, the number of sessions was based on the clinical need of the individual youth. However, most interventions did have a set number of sessions, which ranged from 5 to 32. This is particularly important when working with low-income Latinx families, since many of them do not have access to private insurance, and public insurance, depending on the state, may have a limit on the number of sessions a person receives per year. We also noticed that the outcomes measured by the studies sometimes were clustered together (e.g., externalizing symptoms). It is possible that this is the result of using measures that do not provide specific information about the issue a youth may be facing (e.g., Child Behavior Checklist). However, this may prevent studies from identifying the effectiveness of the intervention on the specific MEB health issues it aims to target.

Although it was beyond the scope of this review to identify cultural adaptations made to the interventions, it became evident through our review that several interventions (e.g., Familias Unidas, Sembrando Salud, Bridges/Puentes, Entre Dos Mundos) were developed specifically for Latinx families and included issues that were of particular relevance to Latinxs such as issues related to immigration and acculturation. Future studies would benefit from investigating the different cultural components that may influence the acceptability and effectiveness of the interventions. Also, future review studies summarizing the cultural adaptations made to the interventions are warranted to better understand how effective interventions with Latinx populations address the specific needs of the families, namely immigration information, trauma, language, client-provider ethnoracial concordance. This information can help the field understand whether including interventions that incorporate culturally relevant programs that bolster positive ethnic identity formation and development can reduce the risk of MEB health.

In our study we also found that besides the studies that targeted families from Mexico or from Mexican ancestry (Gonzales et al., 2012; Gonzales et al., 2018; Jensen et al., 2014), most studies did not include a lot of information regarding the ethnic heritage or race of participants. It would be helpful for future interventions to incorporate aspects of Latinx heterogeneity, including how race and experiences of racial discrimination impact Latinxs’ MEB health. Race is one of the more overlooked sources of distress among Latinx communities (Gonzalez-Barrera, 2015). Latinxs are commonly racialized by phenotype and skin color in the U.S. (Cuevas et al., 2016). Latinxs whose phenotypic features indicate Black or indigenous ancestries experience more discrimination than White Latinxs (Alvarez, 2019; Figuereo & Calvo, 2021). There is evidence that such discrimination excludes Black-Latinxs from equal access to opportunities for advancement, which leads to poverty, low levels of homeownership, poor health, and mental health problems (Cuevas et al., 2016; Figuereo & Calvo, 2021; LaVeist-Ramos et al., 2012). This suggests that interventions targeting the Latinx population would also benefit from including modules that cover the diverse experiences of Latinx youths and families.

In our study we also found that most of the interventions targeted the main caregiver, which often time was the mother. In the parenting and family mental health field, the dominant paradigm has focused on the effects mothers’ experiences, health, and well-being have on child outcomes (Paredes & Parchment, 2020). However, given the importance of familismo among Latinx families and extensive literature demonstrating the importance of engaging the entire family unit (Santisteban et al., 2013), future studies should consider engaging fathers and other family members as part of the intervention (Paredes & Parchment, 2021).

Limitations

This review is not without limitations. First, this study defined family interventions as those where at least one session was delivered to the parent and the child, leading to the potential omission of parenting or youth interventions that addressed family issues (e.g., relationships, communication) but did not deliver sessions to the family unit. Future studies should investigate the extent to which parent and youth interventions address issues at the family level in order to provide a more comprehensive understanding of interventions that target families. A second limitation also related to our search terms concerns the possibility that we missed terms that were related to interventions that were delivered to families. We tried to address this issue by conducting a reference search with the hope of identifying other studies that our original search might have missed. However, it is still possible that some interventions may have been missed. A third limitation is the fact that some studies did not provide specific information about the issues the intervention targeted. Some studies mentioned that the intervention was successful in addressing “externalizing” or “internalizing” symptoms. Future studies should be as specific as possible when measuring symptomology to have a better understanding of the target outcomes the interventions address effectively among Latinx youths. A final limitation is the lack of generalizability of the findings, given that the samples of the study were predominantly low-income, Latinx participants; therefore, it is not advised to generalize to other populations.

Conclusion

Overall, this systematic review found that family interventions are a promising approach to the promotion of MEB health among Latinx families. The evidence seems to indicate that improving family relationships can have positive and important repercussions on MEB health; however, more work is still needed to identify other mechanisms of change. Moreover, it is necessary to identify the cultural aspects, beyond language adaptations, that make family interventions appealing for Latinx immigrant families. The continuous growth of the Latinx population and the high rates of MEB issues make it imperative to focus on Latinx families and their needs.

Highlights.

Youth of Latinx immigrants have high rates of mental, emotional, and behavioral issues

Culturally grounded and responsive family interventions are a promising approach to promote mental health among Latinx families

Targeting the family, improving communication, and reducing conflict promote Latinx youth’s mental health

There was substantial heterogeneity regarding modes of intervention delivery, number of sessions, and

Funding:

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Declarations of interest: none

We use the term Latinx to be gender neutral and inclusive of all identities and lived experiences of this population.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ackert E, Hong SH, Martinez J, Van Praag G, Aristizabal P, & Crosnoe R (2021). Understanding the health landscapes where latinx immigrants establish residence in the U.S. Health Affairs, 40(7), 1108–1116. 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegría M, Canino G, Ríos R, Vera M, Calderón J, Rusch D, & Ortega AN (2002). Mental health care for Latinos: Inequalities in use of specialty mental health services among Latinos, African Americans, and Non-Latino Whites. Psychiatric Services, 53(12), 1547–1555. 10.1176/appi.ps.53.12.1547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez F (2019). Mestizo, Negro, Blanco—What does it mean? Racism and colorism’s effects in the Latinx community. Culminating Projects in Social Responsibility. Retrieved from: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/socresp_etds/18 [Google Scholar]

- Arora PG, Alvarez K, Huang C, & Wang C (2021). A three-tiered model for addressing the mental health needs of immigrant-origin youth in schools. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 23(1), 151–162. 10.1007/s10903-020-01048-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avenevoli S, Baio J, Bitsko RH, Blumberg SJ, Brody DJ, Crosby A, Gfroerer J, Ghandour RM, Hall JE, & Hedden SL (2013). Mental health surveillance among children--United States, 2005–2011. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/su6202a1.htm [PubMed]

- Bámaca-Colbert MY, Umaña-Taylor AJ, & Gayles JG (2012). A developmental-contextual model of depressive symptoms in Mexican-origin female adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 48(2), 406–421. 10.1037/a0025666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann AA, Kuhlberg JA, & Zayas LH (2010). Familism, mother-daughter mutuality, and suicide attempts of adolescent Latinas. Journal of Family Psychology, 24(5), 616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budiman A, Tamir C, Mora L, Now-Bustamante L Facts on U.S. immigrants, 2018. Statistical portrait of the foreign-born population in the United States. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from: https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2020/08/20/facts-on-u-s-immigrants/

- Cordova D, Huang S, Pantin H, & Prado G (2012). Do the effects of a family intervention on alcohol and drug use vary by nativity status? Psychology of Addictive Behaviors: Journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors, 26(3), 655–660. 10.1037/a0026438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas AG, Araujo Dawson B, & Williams DR (2016). Race and skin color in Latino health: An analytic review. American Journal of Public Health, 106(12), 2131–2136. 10.2105/ajph.2016.303452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cupito AM, Stein GL, & Gonzalez LM (2015). Familial cultural values, depressive symptoms, school belonging and grades in Latino adolescents: Does gender matter? Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(6), 1638–1649. 10.1007/s10826-014-9967-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dillman Carpentier FR, Mauricio AM, Gonzales NA, Millsap RE, Meza CM, Dumka LE, Germán M, & Genalo MT (2007). Engaging Mexican origin families in a school-based preventive intervention. Journal of Primary Prevention, 28(6), 521–546. 10.1007/s10935-007-0110-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder JP, Litrownik AJ, Slymen DJ, Campbell NR, Parra-Medina D, Choe S, Lee V, & Ayala GX (2002). Tobacco and alcohol use–prevention program for Hispanic migrant adolescents. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 23(4), 269–275. 10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00515-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrada Y, Lee TK, Wagstaff R, Rojas LM, Tapia MI, Velázquez MR, Sardinas K, Pantin H, Sutton MY, & Prado G (2019). eHealth Familias Unidas: Efficacy trial of an evidence-based intervention adapted for use on the internet with Hispanic families. Prevention Science, 20(1), 68–77. 10.1007/s11121-018-0905-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrada Y, Rosen A, Huang S, Tapia M, Sutton M, Willis L, Quevedo A, Condo C, Vidot DC, Pantin H, & Prado G (2015). Efficacy of a brief intervention to reduce substance use and human immunodeficiency virus infection risk among Latino youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 57(6), 651–657. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figuereo V, & Calvo R (2021). Racialization and psychological distress among U.S. Latinxs. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 9, 865–873. 10.1007/s40615-021-01026-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Dumka LE, Millsap RE, Gottschall A, McClain DB, Wong JJ, Germán M, Mauricio AM, Wheeler L, Carpentier FD, & Kim SY (2012). Randomized trial of a broad preventive intervention for Mexican American adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(1), 1–16. 10.1037/a0026063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Jensen M, Tein JY, Wong JJ, Dumka LE, & Mauricio AM (2018). Effect of middle school interventions on alcohol misuse and abuse in Mexican American high school adolescents: Five-year follow-up of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(5), 429–437. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.0058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Barrera A (2015). ‘Mestizo’and ‘mulatto’: Mixed-race identities among U.S. Hispanics. Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán A, Koons A, & Postolache TΤ (2009). Suicidal behavior in Latinos: Focus on the youth. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 21(4), 431–440. 10.1515/IJAMH.2009.21.4.431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haley JM, Kenney GM, Bernstein H, & Gonzalez D (2020). One in five adults in immigrant families with children reported chilling effects on public benefit receipt in 2019. Urban Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savović J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, & Sterne JAC (2011). The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ, 343, d5928. 10.1136/bmj.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogue A, Dauber S, Henderson CE, Bobek M, Johnson C, Lichvar E, & Morgenstern J (2015). Randomized Trial of family therapy versus nonfamily treatment for adolescent behavior problems in usual care. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 44(6), 954–969. 10.1080/15374416.2014.963857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquez F, Vaughn L, Zhen-Duan J, & Graham C (2016). Health care use and barriers to care among Latino immigrants in a new migration area. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 27(4), 1761–1778. 10.1353/hpu.2016.0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen MR, Wong JJ, Gonzales NA, Dumka LE, Millsap R, & Coxe S (2014). Long-term effects of a universal family intervention: Mediation through parent-adolescent conflict. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 43(3), 415–427. 10.1080/15374416.2014.891228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox L, Guerra NG, Williams KR, & Toro R (2011). Preventing children’s aggression in immigrant Latino families: A mixed methods evaluation of the families and schools together program. American Journal of Community Psychology, 48(1), 65–76. 10.1007/s10464-010-9411-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouyoumdjian H, Zamboanga BL, & Hansen DJ (2003). Barriers to community mental health services for Latinos: Treatment considerations. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(4), 394–422. 10.1093/clipsy.bpg041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlberg JA, Peña JB, & Zayas LH (2010). Familism, parent-adolescent conflict, self-esteem, internalizing behaviors and suicide attempts among adolescent Latinas. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 41(4), 425–440. 10.1007/s10578-010-0179-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaVeist-Ramos TA, Galarraga J, Thorpe RJ, Bell CN, & Austin CJ (2012). Are black Hispanics black or Hispanic? Exploring disparities at the intersection of race and ethnicity. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 66(7), e21–e21. 10.1136/jech.2009.103879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TK, Estrada Y, Soares MH, Sánchez Ahumada M, Correa Molina M, Bahamon MM, & Prado G (2019). Efficacy of a family-based intervention on parent-adolescent discrepancies in positive parenting and substance use among Hispanic youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 64(4), 494–501. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, & Moher D (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ, 339, b2700. 10.1136/bmj.b2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddle HA, Dakof GA, Rowe CL, Henderson C, Greenbaum P, Wang W, & Alberga L (2018). Multidimensional Family Therapy as a community-based alternative to residential treatment for adolescents with substance use and co-occurring mental health disorders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 90, 47–56. 10.1016/j.jsat.2018.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litrownik AJ, Elder JP, Campbell NR, Ayala GX, Slymen DJ, Parra-Medina D, Zavala FB, & Lovato CY (2000). Evaluation of a tobacco and alcohol use prevention program for Hispanic migrant adolescents: Promoting the protective factor of parent-child communication. Preventive Medicine, 31(2), 124–133. 10.1006/pmed.2000.0698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez HM, Gonzalez-Barrera A, & López G (2017). Hispanic identity fades across generations as immigrant connections fall away. Pew Hispanic Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez MH, Krogstad JM, & Flores A (2018). Key facts about young Latinos, one of the nation’s fastest-growing populations. Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Unger JB, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Ritt-Olson A, & Soto D (2012). Acculturation, enculturation, and symptoms of depression in Hispanic youth: The roles of gender, Hispanic cultural values, and family functioning. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41(10), 1350–1365. 10.1007/s10964-012-9774-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luque JS, Soulen G, Davila CB, & Cartmell K (2018). Access to health care for uninsured Latina immigrants in South Carolina. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 310. 10.1186/s12913-018-3138-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuinness LA, & Higgins JPT (2020). Risk-of-bias VISualization (robvis): An R package and Shiny web app for visualizing risk-of-bias assessments. Research Synthesis Methods, 12(1), 55–61. 10.1002/jrsm.1411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milburn NG, Iribarren FJ, Rice E, Lightfoot M, Solorio R, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Desmond K, Lee A, Alexander K, Maresca K, Eastmen K, Arnold EM, & Duan N (2012). A family intervention to reduce sexual risk behavior, substance use, and delinquency among newly homeless youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 50(4), 358–364. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, & Altman DG (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ, 339, b2535. 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. (2009). Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people: progress and possibilities. National Academies Press. 10.17226/12480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noe-Bustamante L, & Flores A (2019). Facts on Latinos in the US. Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Pantin H, Coatsworth JD, Feaster DJ, Newman FL, Briones E, Prado G, Schwartz SJ, & Szapocznik J (2003). Familias Unidas: The efficacy of an intervention to promote parental investment in hispanic immigrant families. Prevention Science, 4(3), 189–201. 10.1023/A:1024601906942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantin H, Prado G, Lopez B, Huang S, Tapia MI, Schwartz SJ, Sabillon E, Brown CH, & Branchini J (2009). A randomized controlled trial of Familias Unidas for Hispanic adolescents with behavior problems. Psychosomatic Medicine, 71(9), 987–995. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181bb2913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paredes TM, & Parchment TM (2021). The Latino father in the postnatal period: The role of egalitarian masculine gender role attitudes and coping skills in depressive symptoms. Psychology of Men & Masculinities, 22(1), 113–123. 10.1037/men0000315 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parker E (2021). Spatial variation in access to the health care safety net for Hispanic immigrants, 1970–2017. Social Science & Medicine, 273, 113750. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peña JB, Kuhlberg JA, Zayas LH, Baumann AA, Gulbas L, Hausmann-Stabile C, & Nolle AP (2011). Familism, family environment, and suicide attempts among Latina youth. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 41(3), 330–341. 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2011.00032.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineros-Leano M, Liechty JM, & Piedra LM (2017). Latino immigrants, depressive symptoms, and cognitive behavioral therapy: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 208, 567–576. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado G, Cordova D, Huang S, Estrada Y, Rosen A, Bacio GA, Leon Jimenez G, Pantin H, Brown CH, Velazquez M-R, Villamar J, Freitas D, Tapia MI, & McCollister K (2012). The efficacy of Familias Unidas on drug and alcohol outcomes for Hispanic delinquent youth: Main effects and interaction effects by parental stress and social support. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 125, S18–S25. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado G, Huang S, Cordova D, Malcolm S, Estrada Y, Cano N, Maldonado-Molina M, Bacio G, Rosen A, & Pantin H (2013). Ecodevelopmental and intrapersonal moderators of a family based preventive intervention for Hispanic youth: A latent profile analysis. Prevention Science, 14(3), 290–299. 10.1007/s11121-012-0326-x.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado G, Pantin H, Briones E, Schwartz SJ, Feaster D, Huang S, Sullivan S, Tapia MI, Sabillon E, Lopez B, & Szapocznik J (2007). A randomized controlled trial of a parent-centered intervention in preventing substance use and HIV risk behaviors in Hispanic adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(6), 914–926. 10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado G, Pantin H, Huang S, Cordova D, Tapia MI, Velazquez M-R, Calfee M, Malcolm S, Arzon M, Villamar J, Jimenez GL, Cano N, Brown CH, & Estrada Y (2012). Effects of a family intervention in reducing HIV risk behaviors among high-risk Hispanic adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 166(2), 127–133. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez AG, Gallion KJ, Aguilar R, & Dembeck ES (2017). Mental health and Latino kids: A research review. Salud America: Research Review. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins MS, Szapocznik J, Dillon FR, Turner CW, Mitrani VB, & Feaster DJ (2008). The efficacy of structural ecosystems therapy with drug-abusing/dependent African American and Hispanic American adolescents. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(1), 51–61. 10.1037/0893-3200.22.1.51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña J (2015). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban DA, Coatsworth JD, Perez-Vidal A, Kurtines WM, Schwartz SJ, LaPerriere A, & Szapocznik J (2003). Efficacy of brief strategic family therapy in modifying Hispanic adolescent behavior problems and substance use. Journal of Family Psychology, 17(1), 121–133. 10.1037/0893-3200.17.1.121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban DA, Czaja SJ, Nair SN, Mena MP, & Tulloch AR (2017). Computer informed and flexible family-based treatment for adolescents: A randomized clinical trial for at-risk racial/ethnic minority adolescents. Behavior Therapy, 48(4), 474–489. 10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban DA, Mena MP, & Abalo C (2013). Bridging diversity and family systems: Culturally informed and flexible family-based treatment for Hispanic adolescents. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice, 2(4), 246–263. 10.1037/cfp0000013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban DA, Mena MP, & McCabe BE (2011). Preliminary results for an adaptive family treatment for drug abuse in Hispanic youth. Journal of Family Psychology, 25(4), 610–614. 10.1037/a0024016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smokowski PR, & Bacallao M (2008). Entre Dos Mundos/Between Two Worlds: Youth violence prevention for acculturating Latino families. Research on Social Work Practice, 19(2), 165–178. 10.1177/1049731508315989 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stein GL, Cupito AM, Mendez JL, Prandoni J, Huq N, & Westerberg D (2014). Familism through a developmental lens. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 2(4), 224–250. 10.1037/lat0000025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J (2003). Therapy manuals for drug addiction: Brief strategic family therapy for adolescnet drug abuse. Manual 5. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Kurtines WM, & Fernandez T (1980). Bicultural involvement and adjustment in Hispanic-American youths. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 4(3), 353–365. 10.1016/0147-1767(80)90010-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Rio A, Murray E, Cohen R, Scopetta M, Rivas-Vazquez A, Hervis O, Posada V, & Kurtines W (1989). Structural family versus psychodynamic child therapy for problematic Hispanic boys. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 57(5), 571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, & Sribney WM (2011). Understanding the Hispanic health paradox through a multi-generation lens: A focus on behavior disorders. In Carlo G, Crockett LJ, & Carranza MA (Eds.), Health disparities in youth and families: Research and applications (pp. 151–168). Springer. 10.1007/978-1-4419-7092-3_7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]