Abstract

The MEK5–extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK5) tandem is a novel mitogen-activated protein kinase cassette critically involved in mitogenic activation by the epidermal growth factor (EGF). The atypical protein kinase C isoforms (aPKCs) have been shown to be required for cell growth and proliferation and have been reported to interact with the adapter protein p62 through a short stretch of acidic amino acids termed the aPKC interaction domain. This region is also present in MEK5, suggesting that it may be an aPKC-binding partner. Here we demonstrate that the aPKCs interact in an EGF-inducible manner with MEK5 and that this interaction is required and sufficient for the activation of MEK5 in response to EGF. Consistent with the role of the aPKCs in the MEK5-ERK5 pathway, we show that ζPKC and λ/ιPKC activate the Jun promoter through the MEF2C element, a well-established target of ERK5. From all these results, we conclude that MEK5 is a critical target of the aPKCs during mitogenic signaling.

The atypical protein kinase C isoforms (aPKCs), ζPKC and λ/ιPKC, are involved in a number of distinct signal transduction pathways critical for cell proliferation and apoptosis (1, 2, 6, 21–23, 30, 45). Through the MEK–extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling cascade, the aPKCs participate in the regulation of the AP-1 transcription factor and, through the regulation of the IκB kinase complex, they have been implicated in the activation of NF-κB (2, 8, 9, 17, 18, 20, 26, 27, 33, 39, 44, 50, 54, 57, 58, 61–64, 66). Both transcription factors are essential components in proliferative and prosurvival signaling. How a single kinase isoform can participate in disparate cascades could be accounted for by the existence of scaffold proteins that selectively locate the kinase in specific pathways (15, 42, 43). In this regard, we and others have shown that the aPKCs interact with different protein modulators. For example, both aPKCs but not the novel of the classical isoforms interact with the proapoptotic protein Par-4 (19, 21, 63) and with the scaffold protein p62 (47, 51–53), which bind the aPKCs at different domains. Thus, whereas Par-4 interacts with the zinc fingers of ζPKC and λ/ιPKC (47, 51–53), p62 interacts with their respective V1 regions that include the first 126 amino acids (aa) located upstream from the zinc finger (51). The binding of Par-4 leads to the inhibition of aPKC enzymatic activity (21), whereas the binding of p62 has no effect on that parameter (51). Interestingly, Par-4 is overexpressed in cells committed to programmed cell death in response to different stimuli, which provokes the inactivation of the aPKCs that is an important event for apoptosis to occur (4, 10, 19, 21, 28, 56, 63). In contrast, p62 is constitutively bound to the aPKCs, and recent results from this laboratory strongly suggest that it serves to link these PKC isoforms to specific receptor-signaling complexes. In this regard, p62 interacts with the adapter protein RIP (53) which is a death domain kinase that upon cell activation with tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) associates through homotypic interactions with TRADD, another death-domain protein that serves to recruit RIP to the TNF receptor-signaling complex (29). In addition, p62 also interacts with TRAF6 (52), which is an important intermediate in the activation of NF-κB by interleukin-1 signaling that also involves death domain-containing proteins such as MyD88 and IRAK (11, 12, 41, 59). The regions of p62 responsible for the interaction with RIP, TRAF6, and the aPKCs have been carefully mapped in our laboratory (52). It is clear that the three proteins dock at different regions in p62. Thus, the intermediary domain of RIP that is necessary and sufficient for NF-κB activation (29, 36) directly binds to a cysteine-rich sequence in p62 named the ZZ domain (53). In contrast, TRAF6 interacts with a relatively small sequence of amino acids located downstream of the ZZ region (52). Interestingly, the deletion of a small acidic stretch of 14 aa in p62 completely abrogates the interaction of this protein with the aPKCs (52). A BLAST search of the DNA data banks with this sequence, which we have termed AID for aPKC-interaction domain, reveals the existence of a highly homologous region in the amino-terminal portion of the α isoform of the protein kinase MEK5 (25, 67), the upstream activator of the big mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 (also known as ERK5) and a critical regulator of mitogenic signaling (32, 34, 35). Because the aPKCs have been shown to be necessary for mitogenic activation (1, 6), the potential connection between these PKC isoforms and the MEK5-ERK5 pathway was an attractive possibility.

Here we demonstrate that the aPKCs interact, in a stimulus-dependent manner, with MEK5 through AID and that this is important for the mitogenic activation of the MEK5-ERK5 signaling cascade. Interestingly, this activation is independent of aPKC enzymatic activity, strongly suggesting that these PKCs join the increasing number of kinases that are implicated in signal transduction in a manner that does not necessarily require their enzymatic activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and cell culture.

Recombinant human epidermal growth factor (EGF) was purchased from Upstate Biotechnology. The monoclonal 12CA5 anti-hemagglutinin (HA) and anti-Flag antibodies were from Boehringer and Sigma, respectively. The polyclonal anti-Myc, anti-HA epitope, anti-ζPKC, and anti-ERK5 antibodies as well as the monoclonal anti-glutatione S-transferase (GST) antibody were from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Inc. The polyclonal anti-MEK5 antibody was from Chemicon. HeLa and 293 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. Cultures of 293 cells were maintained in high-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal calf serum, penicillin G (100 μg/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) (Flow). HeLa cells were maintained in minimum essential Eagle medium supplemented with 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, 1.0 mM sodium pyruvate, 10% fetal calf serum, penicillin G (100 μg/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) (Flow). Subconfluent cells were transfected by the calcium phosphate method (Clontech, Inc.).

Plasmids and reporter assays.

pcDNA3-HA-ζPKC, pcDNA3-HA-ζPKCMUT, pCDNA3-HA-λ/ιPKCMUT, pCDNA3-HA-λ/ιPKC, pCDNA3-Myc-ζPKC, pCDNA3-Myc-ζPKCMUT, pcDNA3-HA-αPKC, pcDNA3-HA-ɛPKC, pCDNA-HA-ERK2, and pGEX-2KT-ζPKCReg(GST-ζPKCReg) plasmids have been previously described (7, 21, 51, 53). PCR-amplified rat MEK5 cDNA was cloned into pcDNA3HA, pcDNA3Flag, pCMVGST6, and pMAL-c2, and full-length human ERK5 was cloned into pcDNA3-HA, pcDNA3-Flag, and pMAL-c2. The kinase-inactive (MEK5MUT) and the dominant-negative (MEK5AA) mutants of MEK5 were obtained by site-directed mutagenesis (Quick-Change Site-Directed Mutagenesis; Stratagene) replacing lysine 195 with methionine and serine 311 and threonine 315 with alanine, respectively. GST-MEK5ΔAID is a deletion mutant of aa 64 to 76 obtained by the same method. The first 102 aa of MEK5 were subcloned into pcDNA3-HA or pCMVGST6 to generate pcDNA3-HA-MEK5ΔC or GST-MEK5AID, respectively. The GST-MEF2C (aa 87 to 467) fusion protein was obtained by PCR. The GST-ζPKCV1 construct was generated by inserting the first 126aa of ζPKC into pCMVGST6, MBP-ERK5 (pMAL-c2-ERK5), MBP-MEK5 (pMAL-c2-MEK5), and GST-MEF2C (pGEX-3x-MEF2C) were transformed into Escherichia coli TG1 (MBP fusion proteins) and E. coli JM101 (GST fusion proteins), respectively, and the purification of fusion proteins was carried out according to the manufacturer's procedures. Wild-type or kinase-inactive GST-MEK5 (pCMVGST6-MEK5WT/MUT) was expressed in 293 cells and purified on glutathione-Sepharose. Recombinant full-length ζPKC was prepared by using the Bac-to-Bac baculovirus expression system (Life Technologies). The luciferase reporter plasmids pJTX and pJSTX, containing the murine c-Jun promoter mutated in the AP-1 site or in the AP-1 and MEF2C sites, respectively, were generously provided by R. Prywes. Luciferase assays were performed with the Dual-Luciferase Reporter assay system from Promega following the manufacturer's instructions. Luciferase activity was normalized with Renilla.

Immunoprecipitations and kinase assays.

For coimmunoprecipitations, subconfluent 293 cells plated on 100-mm-diameter dishes were transfected with the indicated expression plasmids. After transfection (24 h), cells were harvested and lysed in buffer PD (40 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 500 mM NaCl, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 6 mM EDTA, 6 mM EGTA, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 10 mM NaF, 10 mM p-nitro-phenyl-phosphate, 300 μM Na3VO4, 1 mM benzamidine, 2 M phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, aprotinin [10 μg/ml], leupeptin [1 μg/ml], pepstatin [1 μg/ml], 1 mM dithiothreitol). Extracts were centrifuged twice at 15,000 × g for 15 min, and 1 mg of whole-cell lysate was diluted in PD buffer and incubated with 5 to 10 μg of the indicated antibody. This reaction mixture was incubated on ice for 2 h, and then 25 μl of protein A or G beads was added, and the mixture was left to incubate with gentle rotation for an additional 1 h at 4°C. The immunoprecipitates were then washed five times with PD buffer. Samples were fractionated by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), transferred to Nitrocellulose ECL membrane (Amersham) and subjected to Western blot analysis with the corresponding antibody. Proteins were detected with the ECL reagent (Amersham). For immunoprecipitations of endogenous ζPKC, 293 cells stably transfected with HA-MEK5 were used. Cells were made quiescent and stimulated with 5 ng of EGF per ml for different times. After which treatment, cells were lysed, and extracts were immunoprecipitated as described above. For experiments of endogenous interaction between MEK5 and aPKCs, HeLa or PC12 cells were serum starved for 24 h and stimulated with 5 ng of EGF per ml at different times. After which treatment, cells were lysed in PD buffer, and 1 mg of extract was immunoprecipitated with 12 μg of monoclonal anti-λPKC antibody by incubation at 4°C overnight with rotation. Immune complexes were recovered by the addition of 40 μl of anti-mouse immunoglobulin G-agarose for 2 h at 4°C. The beads were washed three times in lysis buffer, followed by a final wash in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8). The immune complexes were separated by SDS-PAGE on an 8% gel, transferred to nitrocellulose, and Western blotted with a polyclonal anti-MEK5 antibody. ERK2 activity was determined as previously described (7). ERK5 activity was measured at 30°C for 20 min in a reaction mixture containing 1 μg of GST-MEF2C as a substrate, 20 μM ATP, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM MnCl2, and 2 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP. Samples were analyzed by SDS–12% PAGE, followed by autoradiography. The quantitation was done with an Instant Imager (Packard).

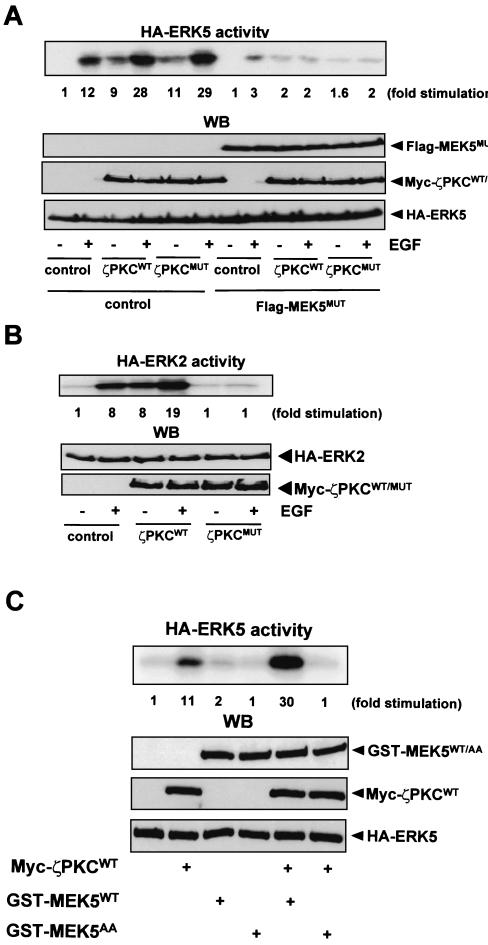

For the in vitro binding assays, recombinant bacterially expressed GST-ζPKCReg or GST and MBP-MEK5 were incubated in PD buffer at 4°C for 4 h. Afterwards, the reaction mixture was immunoprecipitated with anti-GST antibody, and the immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-MEK5 antibody.

Flow cytometry cell cycle analysis.

Subconfluent cultures of 293 cells were transfected with 10 μg of either GST, GST-MEK5AID, or GST-ζPKCV1 expression vectors. Twenty hours posttransfection, cell cultures were incubated with a low (0.2%) concentration of serum for 24 h and were then stimulated with EGF (100 ng/ml) for 20 h. Afterwards, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline, trypsinized, and centrifuged, and the pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of a solution containing 50 μg of propidium iodide per ml, 20 μg of RNase per ml, 0.6% Nonidet P-40, and 0.1% sodium citrate and incubated for 20 min at 37°C. Cells were then analyzed in an EPICS XL flow cytometer (Coulter Electronics, Inc., Hialeah, Fla.) by recording the propidium iodide staining in the red channel.

RESULTS

Interaction of aPKCs with MEK5.

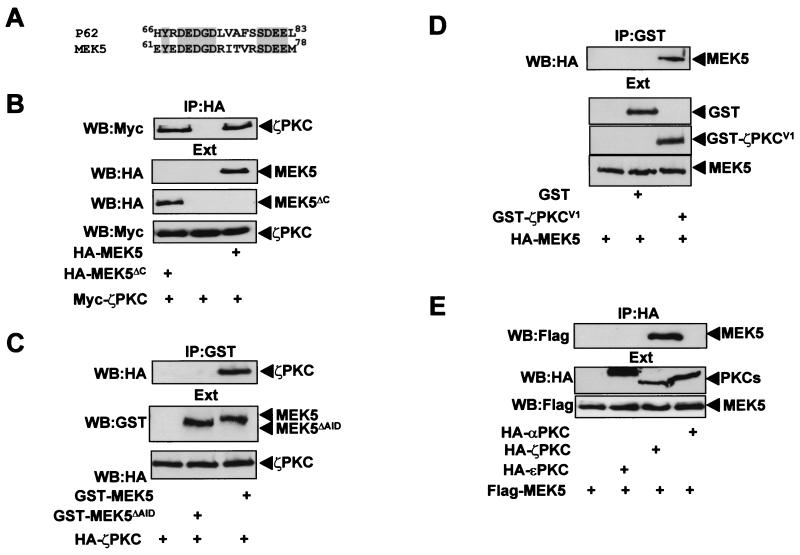

A BLAST search of the DNA data banks with the AID sequence of p62 reveals the existence of a highly homologous region in the α isoform of the kinase MEK5 (Fig. 1A). In order to determine whether the aPKCs could interact with this protein, an expression vector for a Myc-tagged version of ζPKC was transfected into 293 cells either alone or in combination with an expression plasmid for HA-tagged MEK5 constructs that express either the wild-type protein or a deletion mutant that harbors just the amino-terminal sequence containing the AID homology region (MEK5ΔC). Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with a monoclonal anti-HA antibody, and the immunoprecipitates were analyzed with a polyclonal anti-Myc antibody. The results shown in Fig. 1B demonstrate that ζPKC coimmunoprecipitates with wild-type and mutant MEK5ΔC (Fig. 1B), indicating that the AID sequence may account for that interaction. The amount of MEK that coprecipitates with ζPKC is comparable to that of p62 in previous experiments (51). Identical results were obtained when the binding of λ/ιPKC to MEK5 was investigated (not shown). In order to demonstrate that the AID site is critical for interaction with aPKCs, a GST-MEK5 construct in which aa 64 to 76 were deleted (MEK5ΔAID) was cotransfected along with the HA-tagged ζPKC, and the interaction was investigated as above. Whereas the wild-type GST-MEK5 interacted potently with ζPKC, the AID deletion mutant showed little or no binding (Fig. 1C). We and others have previously reported that the V1 domain of the aPKCs which includes the first 126 aa accounts for the interaction with the AID site of p62 (47, 51–53). In order to demonstrate that this is also the case for MEK5, we transfected 293 cells with a GST-ζPKCV1 construct that expresses the V1 domain of ζPKC fused to the GST protein, along with the HA-tagged MEK5 expression vector. Results shown in Fig. 1D indicate that the V1 domain is sufficient to account for the interaction with MEK5. Results shown in Fig. 1E demonstrate that MEK5 does not interact with the classical αPKC or the novel ɛPKC isoforms. These evidences strongly suggest that MEK5 is a bona fide aPKC-interacting protein. The ζPKC-p62 interaction has been shown to be direct (51). In the next series of experiments, we incubated recombinant bacterially expressed purified GST-ζPKCREG with MBP-MEK5, after which the ζPKC construct was immunoprecipitated with an anti-GST antibody, and the associated MBP-MEK5 was determined with an anti-MEK5 antibody. Results shown in Fig. 2 demonstrate that the ζPKC-MEK5 interaction is direct.

FIG. 1.

Interaction of aPKCs with MEK5. (A) Alignment of the AIDs of p62 and MEK5. Shaded letters indicate identical amino acids. (B) Subconfluent cultures of 293 cells in 100-mm-diameter plates were transfected with 5 μg of the Myc-ζPKC expression plasmid either alone or in combination with 5 μg of either HA-MEK5 or HA-MEK5ΔC and enough pCDNA3 plasmid to give 10 μg of total DNA. Twenty-four hours posttransfection, cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody, and the immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Myc antibody. (C) Cell cultures as described above (B) were transfected with 5 μg of HA-ζPKC along with 5 μg of either GST-MEK5 or GST-MEK5ΔAID and enough empty plasmid to give 10 μg of total DNA, cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-GST antibody, and the immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-HA antibody. (D) Cell cultures as described above (B) were transfected with 5 μg of HA-MEK5 along with 5 μg of either GST or GST-ζPKCV1 and enough empty plasmid to give 10 μg of total DNA, cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-GST antibody, and the immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-HA antibody. (E) Cell cultures as described above (B) were transfected with 5 μg of HA-tagged versions of αPKC, ɛPKC, or ζPKC either alone or in combination with 5 μg of Flag-MEK5 and enough pCDNA3 plasmid to give 10 μg of total DNA. The PKCs were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody, and the immunoprecipitates were analyzed with anti-Flag antibody. An aliquot (one-tenth of the amount of extract [Ext]) used for the immunoprecipitation) was loaded in the gels and analyzed by immunoblotting with the corresponding anti-Tag antibodies (B through E). Essentially identical results were obtained in another three independent experiments.

FIG. 2.

The interaction of ζPKC with MEK5 is direct. Recombinant bacterially expressed GST (800 nM) or GST-ζPKCReg (800 nM) was incubated with 800 nM MBP-MEK5 as described in Materials and Methods. The reaction mixture was immunoprecipitated with the anti-GST antibody, and the immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-MEK5 antibody. Essentially identical results were obtained in another experiment.

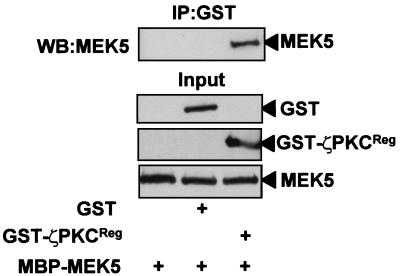

To determine whether the endogenous aPKCs will interact with MEK5 in a more physiological situation, we initially generated a stable cell line (293-MEK5) that expresses HA-tagged MEK5. Afterward, quiescent cultures of 293-MEK5 cells were either untreated or stimulated with EGF, a well-established mitogenic activator of the MEK5-ERK5 pathway (13, 32, 34, 35) for different times, after which cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with a polyclonal anti-ζPKC antibody, and the immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with the monoclonal anti-HA antibody. As a control for the activation of this pathway, ERK5 was also immunoprecipitated from the same extracts, and its activity was determined. Results shown in Fig. 3A demonstrate that EGF was a potent activator of ERK5 in our 293-MEK5 system. Interestingly, although little or no interaction of endogenous ζPKC with MEK5 was detected in unstimulated cells, the addition of EGF triggered a rapid and robust interaction (Fig. 3B) with a kinetic that is entirely consistent with the activation of ERK5 (Fig. 3A). Next we analyzed the interaction of both endogenous proteins. Cell extracts from HeLa (Fig. 3C) or PC12 (results not shown) cells treated with EGF for different times or left untreated were incubated with a monoclonal anti-λ/ιPKC antibody to immunoprecipitate the endogenous λ/ιPKC. Afterwards, these immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with a polyclonal anti-MEK5 antibody. The results of these experiments clearly show that EGF triggers the association of endogenous λ/ιPKC with endogenous MEK5 in HeLa (Fig. 3C) and PC12 (results not shown) cells. Together, these results indicate that, in marked contrast with the interaction of ζPKC with p62 (51), the binding to MEK5 is EGF inducible. These evidences indicate that MEK5 may be a downstream target of the aPKCs during mitogenic signal transduction.

FIG. 3.

The interaction of endogenous ζPKC with MEK5 is EGF dependent. Subconfluent cultures of 293 cells stably expressing the HA-MEK5 construct were made quiescent by serum starvation for 24 h. Afterward, cell cultures were stimulated with EGF (5 ng/ml) for different times, and cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-ERK5 (A) or anti-ζPKC (B) antibodies. ERK5 activity was determined in the anti-ERK5 immunoprecipitates (A), whereas the anti-ζPKC immunoprecipitates were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with the anti-HA and anti-ζPKC antibodies (B). An aliquot (one-tenth of the amount of extract [Ext] used for the immunoprecipitation) was loaded in the gels and analyzed by immunoblotting with the anti-HA antibody. (C) Subconfluent cultures of HeLa cells were serum starved for 24 h after which they were either untreated or stimulated with EGF (5 ng/ml) for different times. Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with a monoclonal anti-λ/ιPKC antibody, and the immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with a polyclonal anti-MEK5 antibody. Essentially identical results were obtained in another three independent experiments.

Role of the aPKCs in the activation of MEK5.

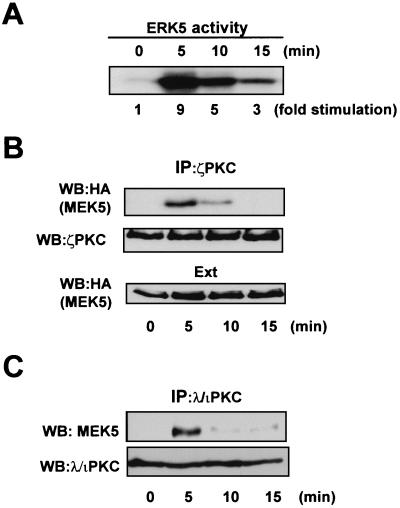

The evidence that the aPKCs interact with MEK5 in response to EGF suggests the existence of a functional link between both kinases. To address the possibility that the aPKCs may regulate the MEK5-ERK5 cascade in vivo, HeLa cells were transfected with a HA-tagged ERK5 construct along with either an empty plasmid or expression vectors for a wild type or a kinase-inactive mutant of ζPKC. After serum starvation, cells were stimulated or not with EGF for 5 min, HA-ERK5 was immunoprecipitated, and its activity was determined. Interestingly, the expression of both wild-type and kinase-inactive ζPKC was sufficient to promote ERK5 activation and synergistic cooperation with EGF (Fig. 4A). As a control, HeLa cells were transfected with HA-ERK2 along with the ζPKC constructs. In agreement with previously reported observations, the overexpression of wild-type ζPKC cooperated with EGF to activate ERK2, whereas the kinase-inactive mutant blocked the activation of ERK2 (Fig. 4B). Similar results were obtained when these experiments were repeated with λ/ιPKC expression constructs (results not shown). The ability of the aPKCs to activate ERK5 in vivo depends on MEK5 activity, as the expression of a MEK5 kinase-inactive mutant completely abrogates ERK5 activation by EGF and by the transfected ζPKC (Fig. 4A). Serine 311 and threonine 315 residues in the activation loop of MEK5 have been shown to be essential for kinase function (34). Therefore, in the next series of experiments we mutated both residues to alanines to generate the GST-MEK5AA construct. This plasmid was transfected into 293 cells either alone or in combination with Myc-ζPKC, and the activity of HA-ERK5 was determined. Interestingly, the results demonstrate that the activation of ERK5 by ζPKC is severely impaired by the expression of the MEK5AA mutant, indicating that those residues are essential for MEK5 functionality (Fig. 4C).

FIG. 4.

Role of ζPKC in the activation of ERK5 and ERK2 by EGF. Subconfluent cultures of HeLa cells in 100-mm-diameter plates were transfected with 2 μg of either HA-ERK5 (A) or HA-ERK2 (B) along with 10 μg of either an empty plasmid or expression vectors for Myc-tagged versions of wild-type (ζPKCWT) or dominant-negative (ζPKCMUT) ζPKC (A and B) with or without 10 μg of kinase-inactive MEK5MUT (A). Twelve hours posttransfection, cells were serum starved for 24 h, after which they were stimulated with EGF (5 ng/ml) for 5 min. Afterward, HA-ERK5 (A) and HA-ERK2 (B) were immunoprecipitated, and their activities were determined. (C) In another set of experiments, HeLa cell cultures, as described above (A and B) were transfected with 2 μg of HA-ERK5 with 10 μg of either GST-MEK5 or GST-MEK5AA and 10 μg of Myc-ζPKC or empty plasmid, and ERK5 activity was determined. An aliquot (one-tenth of the amount of extract [WB] used for the immunoprecipitation) was loaded in the gels and analyzed by immunoblotting with the corresponding anti-Tag antibodies. Essentially identical results were obtained in another three independent experiments.

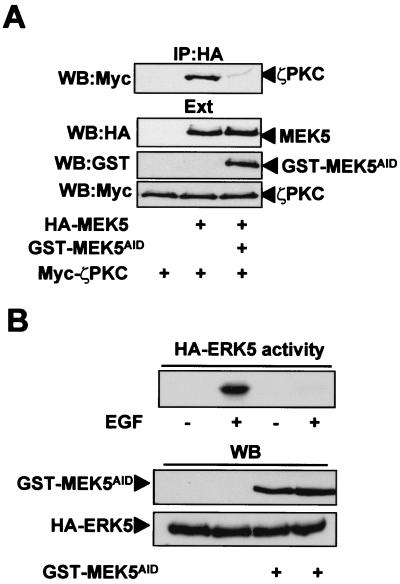

Interaction with the aPKCs is essential for the activation of MEK5.

In order to investigate whether the aPKC-MEK5 interaction is required for the activation of MEK5 by EGF in vivo, a mammalian expression vector for a GST fusion protein containing the AID of MEK5 was generated. We reasoned that the overexpression of this fragment, which is devoid of enzymatic activity, would chelate the aPKCs in an inactive complex impairing the activation of the MEK5-ERK5 cascade by EGF, if the role of the aPKCs in this pathway was important. Therefore, we first determined whether the expression of that construct actually abolished ζPKC-MEK5 interaction by transfecting GST-MEK5AID with tagged versions of ζPKC and MEK5. From the data shown in Fig. 5A, it seems clear that the expression of the GST-MEK5AID construct severely abrogates the binding of ζPKC to MEK5 in vivo. We next transfected HeLa cells with HA-ERK5 with either a control plasmid or the GST-MEK5AID expression vector. Afterward, these cell cultures were stimulated with EGF for 5 min or left unstimulated, and the activity of the immunoprecipitated HA-ERK5 was determined. Interestingly, the expression of GST-MEK5AID severely inhibits ERK5 stimulation by EGF (Fig. 5B), indicating that the interaction with ζPKC is a required event for MEK5 activation in vivo. To further demonstrate this, HA-ERK5 was transfected either with a control vector or the GST-ζPKCV1 plasmid, and cells were treated with EGF or left untreated, as described above. Results shown in Fig. 6 demonstrate that the expression of the ζPKCV1 construct completely abrogates ERK5 activation. Therefore, AID-V1 interaction is required for the activation of the ERK5 pathway by EGF. Interestingly, these results indicate that both GST-MEK5AID and GST-ζPKCV1 are dominant-negative mutants useful to investigate further the functionality of this pathway.

FIG. 5.

The overexpression of the AID of MEK5 inhibits ERK5 activation. (A) Subconfluent cultures of HeLa cells in 100-mm-diameter plates were transfected with 5 μg of the Myc-ζPKC expression plasmid either alone or in combination with 5 μg of HA-MEK5, with or without 10 μg of GST-MEK5AID expression vector and enough pCDNA3 plasmid to give 15 μg of total DNA. Twenty-four hours posttransfection, cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody, and the immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Myc antibody. (B) Subconfluent cultures of HeLa cells in 100-mm-diameter plates were transfected with 2 μg of HA-ERK5 along with 10 μg of either an empty plasmid or the GST-MEK5AID expression vector. Twelve hours posttransfection, cells were serum starved for 24 h, after which they were stimulated with EGF (5 ng/ml) for 5 min. Afterward, HA-ERK5 was immunoprecipitated, and its activity was determined. The expression levels for each construct were determined as described above for panel A. Essentially identical results were obtained in another three independent experiments.

FIG. 6.

The overexpression of the ζPKC V1 domain inhibits ERK5 activation. Subconfluent cultures of HeLa cells in 100-mm-diameter plates were transfected with 2 μg of either HA-ERK5 along with 10 μg of either an empty plasmid or the GST-ζPKCV1 expression vector. Twelve hours posttransfection, cells were serum starved for 24 h, after which they were stimulated with EGF (5 ng/ml) for 5 min. Afterward, HA-ERK5 was immunoprecipitated, and its activity was determined. The expression levels for each construct were determined as described above (see the legend to Fig. 5A). Essentially identical results were obtained in another three independent experiments.

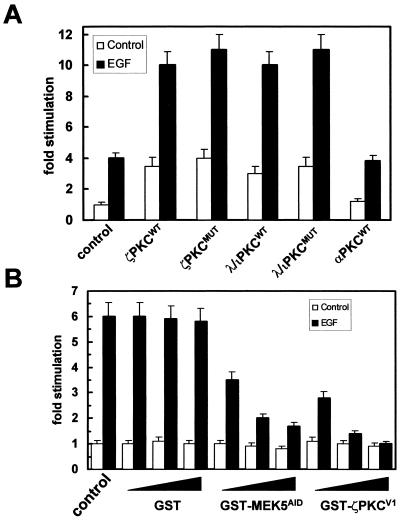

Role of the aPKC-MEK5 interaction in the activation of the Jun promoter and cell growth.

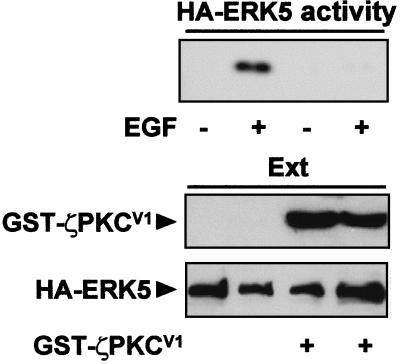

The stimulation of the MEK5-ERK5 pathway leads to the activation of the Jun promoter specifically through a MEF2-binding element (34, 35). If the activation of MEK5 by the aPKCs is functionally relevant, the overexpression of either wild-type or kinase-inactive aPKCs should activate a Jun promoter reporter plasmid in which the AP1 site has been mutated but the MEF2 site is intact. Therefore, HeLa cells were transfected with the luciferase pJTX plasmid along with a control vector of expression plasmids for wild-type or kinase-inactive ζPKC or λ/ιPKC. Cells were serum starved, after which they were either untreated or stimulated with EGF for 6 h. Interestingly, the expression of ζPKC or λ/ιPKC, either in wild-type or kinase-dead form, was sufficient to stimulate the transcriptional activity of the reporter and to synergize with EGF, in keeping with its effects on MEK5 (Fig. 7A). When a similar experiment was done with the pJSTX reporter plasmid harboring an inactivated MEF2 site, stimulation of the reporter transcriptional activity by the ζPKC or λ/ιPKC constructs was not seen (not shown). As an additional control of specificity, the overexpression of αPKC that does not interact with MEK5 (Fig. 1C) produces no effect on pJTX reporter activity (Fig. 7A).

FIG. 7.

Activation of the Jun promoter by the aPKCs. HeLa cells were transfected with the luciferase pJTX plasmid (0.25 μg) and the Renilla control reporter pRL-CMV (2.5 ng) along with 5 μg of control vector or expression plasmids for wild-type or kinase-inactive ζPKC or λ/ιPKC or wild-type αPKC (A). Cells were serum starved, after which they were either untreated or stimulated with EGF (5 ng/ml) for 6 h. In another set of experiments (B), HeLa cells were transfected with the pJTX plasmid as described above (A) with either a control vector or increasing concentrations (2, 5, and 10 μg) of GST, GST-MEK5AID, or GST-ζPKCV1 expression plasmids and enough pCDNA3 to give 15 μg of total DNA, after which cells were stimulated or not with EGF (5 ng/ml) for 6 h. Luciferase activity was normalized with Renilla. Results are the means ± standard deviation of three independent experiments with incubations in duplicate.

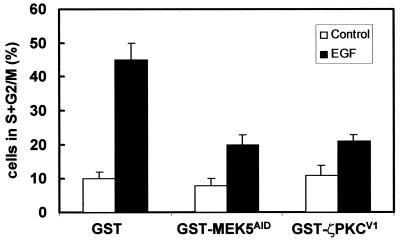

The results shown in Fig. 5 and 6 demonstrate the importance of the AID-V1 interaction for the activation of the ERK5 cascade. In order to determine if this is also true for the MEF2-dependent activation of the Jun promoter, HeLa cells were transfected with the pJTX reporter plasmid along with either the GST control or the GST-MEK5AID or GST-ζPKCV1 constructs, and cells were untreated or stimulated with EGF as before. Interestingly, the expression of GST-MEK5AID and GST-ζPKCV1 but not of GST severely abrogated MEF2-dependent transcriptional activity (Fig. 7B). In the next series of experiments, we addressed the importance of the ζPKC-MEK5 interaction in cell growth. Thus, 293 cells were transfected either with GST, GST-MEK5AID, or GST-ζPKCV1 expression vectors after which they were incubated with a low (0.2%) concentration of serum for 24 h and were then stimulated with EGF for 20 h. Cell cycle analysis demonstrated that the percentage of cells in the S plus G2/M phases of the cell cycle was dramatically reduced when transfected with either GST-MEK5AID or GST-ζPKCV1 but not with GST (Fig. 8). The reduction observed is even more important if it is considered that the efficiency of transfection in this cell system is in the range of 60 to 80%.

FIG. 8.

Importance of ζPKC-MEK5 interaction in EGF-induced mitogenesis. Subconfluent cultures of 293 cells were transfected with 10 μg of either GST, GST-MEK5AID, or GST-ζPKCV1 expression vectors. Twenty hours posttransfection, cell cultures were incubated with a low (0.2%) concentration of serum for 24 h and were then stimulated with EGF for 20 h. The percentage of cells in the S plus G2/M phases of the cell cycle was determined by flow cytometry analysis. Results are the means ± standard deviation of three independent experiments with incubations in duplicate.

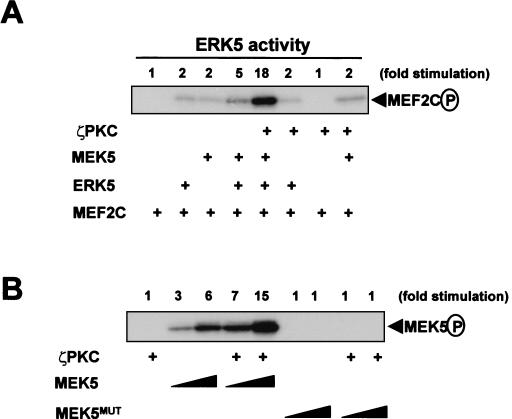

Stimulation of MEK5 in vitro by recombinant ζPKC.

To further explore the activation of MEK5 by the aPKCs, we carried out an in vitro coupled assay in which recombinant GST-MEK5 was incubated with recombinant MBP-ERK5, and its substrate, GST-MEF2C, either with or without recombinant ζPKC. Results (Fig. 9A) show that the presence of ζPKC triggers the activation of ERK5 to phosphorylate MEF2C in a manner that is dependent on MEK5. These results indicate that ζPKC is sufficient to activate the whole ERK5 cascade in vitro. In addition, ζPKC promoted the phosphorylation of wild-type MEK5 but not of its kinase-inactive mutant (Fig. 9B). Similar results were obtained when these experiments were carried out with recombinant wild-type λ/ιPKC or with recombinant ζPKC and λ/ιPKC devoid of enzymatic activity (not shown). These evidences strongly suggest that the aPKCs are unable to directly phosphorylate MEK5 and that they activate this kinase most likely by promoting its autophosphorylation. Of note, GST-ζPKCV1 was unable to activate MEK5 in vitro and even blocked the action of full-length ζPKC (not shown), consistent with its role as a dominant-negative protein (Fig. 6 to 8).

FIG. 9.

Recombinant ζPKC activates MEK5 in vitro. (A) Recombinant MBP-ERK5 (50 ng) was incubated either in the absence or in the presence of recombinant GST-MEK5 (25 ng) with or without recombinant ζPKC (10 ng), and the phosphorylation of the ERK5 substrate, GST-MEF2C (1 μg), was determined. (B) Both 12 and 25 ng of recombinant GST-MEK5 or a kinase-inactive mutant (GST-MEK5MUT) were incubated with or without recombinant ζPKC (10 ng), and their phosphorylation states were determined. Essentially identical results were obtained in another three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

Cell proliferation is the result of the activation of a number of mitogenic signaling cascades originating at the plasma membrane of growth factor-stimulated cells. These signaling pathways serve to transmit the information to the nucleus where the transcription of genes required for the mitogenic response is triggered. The MAP kinase cascades have been shown to be critical components in the pathways that link early mitogenic signaling to cell cycle progression (60) and often converge in the stimulation of the AP-1 transcription factor (3, 37). Four main MAP kinase modules have been described. The first identified is initiated by Raf (a MAP kinase kinase kinase) that phosphorylates and activates MEK1 and -2 (MAP kinase kinases) which is the upstream activator of ERK1 and -2. This cascade has been shown to be essential for cell growth, as dominant-negative mutants of MEK and ERK severely abrogate DNA synthesis. A second MAP kinase module includes the c-Jun amino-terminal kinases (JNKs, or stress-activated protein kinases [SAPKs]) that phosphorylate the transactivation domain of c-Jun promoting its transcriptional activity. The JNKs are activated analogously to the ERKs by JNK kinase 2, also known as MAP kinase kinase 7, and JNK kinase 1 (or MAP kinase kinase 4), functional homologues of MEK1 and -2. The p38 MAP kinase is the end point of another MAP kinase cassette that contains MKK3 and -6 as its upstream activators (5, 16, 38, 46, 49). Another recently identified MAP kinase module is composed of MEK5 and its downstream target ERK5 (24, 32, 35, 67). A proposed target for ERK5 is the MEF2C transcription factor (34), which controls the expression of c-Jun and along with other immediate early genes (37) is important for cell growth (55). Therefore, the activation of this pathway is essential for cell proliferation and oncogenesis. However, the actual components upstream of MEK5 have not been completely identified yet.

Here, we report that the atypical PKC isoforms, ζPKC and λ/ιPKC, interact with a relatively short stretch of amino acids in MEK5 that is highly homologous to the AID of p62 (52). However, there is an important difference between p62 and MEK5. Thus, whereas the interaction of the aPKCs with p62 is constitutive (51), that with MEK5 is induced upon EGF stimulation of quiescent cells. Furthermore, the kinetic of the activation by EGF of the MEK5-ERK5 pathway perfectly matches the induced formation of the ζPKC-MEK5 complex, suggesting that this interaction must be important for ERK5 activation. In fact, we show here that this is the case, as overexpression of ζPKC and λ/ιPKC is sufficient to stimulate ERK5 as well as the Jun promoter through the MEF2C-binding site. Furthermore, recombinant ζPKC is sufficient to activate the MEK5-ERK5 cascade in vitro to promote the phosphorylation of MEK5. Interestingly, the enzymatic activity of the aPKCs was shown here not to be required for the activation of the MEK5-ERK5 cascade or Jun promoter activity in vivo. This suggests that the simple interaction of ζPKC with MEK5 may be sufficient for its activation. In support of this notion, the expression of a MEK5 fragment harboring AID that inhibits the ζPKC-MEK5 interaction also severely abrogated the activation of ERK5 by EGF. Therefore, the aPKCs bind at least two different proteins, MEK5 and p62, through the same motif (AID). Of note, p62 also interacts with RIP (53) and TRAF6 (52), two components of cytokine-signaling pathways involved in NF-κB activation. This suggests that the binding of the aPKCs to MEK5 and p62 serves to selectively position the aPKCs in two distinct signaling cascades. However, whereas p62 seems to be just a scaffold that locates the aPKCs in the NF-κB pathway, MEK5 is a downstream target of ζPKC actions. Recently, Par-6, a protein involved in maintaining cell polarity (31, 40, 48), has been identified as a novel aPKC-interacting partner. Interestingly, the aPKCs bind to a region of Par-6 that maps to residues 15 to 110 (48). This region contains a short amino acid sequence that displays a strong homology with the AID sites of p62 and MEK5 (21a). Our recent results demonstrate that deletion of that site completely abolishes the interaction of the aPKCs with Par-6 (M. T. Diaz-Meco and J. Moscat, unpublished). Therefore, the AID motifs serve to locate the aPKCs into different signaling pathways conferring selectivity to the kinase actions.

How the aPKCs transmit the signal for the activation of MEK5 is not completely understood yet, but the fact that it is independent of the aPKC enzymatic activity, although unexpected, is not surprising, as other kinases have been shown to activate downstream effectors in a similar activity-independent manner. For example, RIP (29), IRAK (11), and the double-stranded RNA-responsive protein kinase (14) are kinases required and sufficient for the activation of NF-κB through a mechanism that is independent of their enzymatic activity. In all these cases, what appears to be important is the ability of the kinase to interact with its downstream targets. Recent results have identified MEK kinase 3 (MEKK3) as a MEK5 partner in a yeast two-hybrid screen (13). Interestingly, MEKK3 interacted with MEK5 in cotransfection experiments and efficiently induced its phosphorylation and stimulation (13). Although the activation of MEK5 by EGF is blocked by a dominant-negative MEKK3 mutant, it is not clear if the interaction of both kinases takes place in vivo in an EGF-inducible manner as we have shown here for the aPKCs. Also, a more-detailed characterization of the elements responsible for the MEKK3-MEK5 interaction needs to be investigated for a more-complete evaluation of the physiological relevance and specificity of that interaction. Further studies should address the relative contributions of both proposed upstream activators when appropriate pharmacological inhibitors and/or knockout mice become available. Preliminary results from our laboratory confirm the interaction of MEKK3 with MEK5 in cotransfection experiments (unpublished data). Of potential relevance, the cotransfection of ζPKC or λ/ιPKC displaces MEK5 from the MEKK3 complex (unpublished data). This suggests that MEK5 interacts independently with either ζPKC or MEKK3 at least when ectopically expressed.

As the aPKCs have been implicated in the regulation of a Raf-independent MEK-ERK pathway and as this is critical for DNA synthesis (see above), this kinase cascade seemed the simplest explanation for the requirement of ζPKC during cell cycle progression. However, there is no obvious docking site in MEK1 or MEK2 for these PKCs as we have found in MEK5, and there is no evidence of an inducible interaction of these MEKs with the aPKCs. Therefore, the data reported here demonstrating not only a functional but also a direct EGF-inducible physical interaction of the aPKCs with MEK5, together with the role of the MEK5-ERK5-Jun cascade in cell growth, open the possibility that this novel pathway may be the one that actually accounts for the aPKC mitogenic actions. An important question that should be addressed in future studies is the identification of the upstream regulators of the aPKCs in this novel pathway. Ras has been proposed by several groups as one of the critical activators of ζPKC in mitogenic signaling (8, 9, 20, 33, 39, 61, 65). However, the implication of Ras in MEK5 activation appears to be cell-type specific (32, 35), which suggests that other mechanisms must exist in systems where Ras does not appear to be relevant. Future studies will attempt to solve this question.

In summary, we show here that the aPKCs are located in a novel mitogenic signaling cascade that involves the interaction of these PKCs with MEK5 through a specific docking site which serves to trigger the activation of ERK5 and the induction of c-Jun, essential components during mitogenic and oncogenic activation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants SAF99-0053 from CICYT, 2FD97-1429 from DGESEIC, and BIO4-CT97-2071 from the European Union and has benefited from an institutional grant from Fundación Ramón Areces to the CBM. We also thank Therapeutic Targets for partially funding this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akimoto K, Nakaya M, Yamanaka T, Tanaka J, Matsuda S, Weng Q P, Avruch J, Ohno S. Atypical protein kinase Clambda binds and regulates p70 S6 kinase. Biochem J. 1998;335:417–424. doi: 10.1042/bj3350417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akimoto K, Takahashi R, Moriya S, Nishioka N, Takayanagi J, Kimura K, Fukui Y, Osada S, Mizuno K, Hirai S, Kazlauskas A, Ohno S. EGF or PDGF receptors activate atypical PKClambda through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. EMBO J. 1996;15:788–798. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angel P, Karin M. The role of Jun, Fos and the AP-1 complex in cell-proliferation and transformation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1072:129–157. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(91)90011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barradas M, Monjas A, Diaz-Meco M T, Serrano M, Moscat J. The downregulation of the pro-apoptotic protein Par-4 is critical for Ras-induced survival and tumor progression. EMBO J. 1999;18:6362–6369. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.22.6362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ben-Levy R, Hooper S, Wilson R, Paterson H F, Marshall C J. Nuclear export of the stress-activated protein kinase p38 mediated by its substrate MAPKAP kinase-2. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1049–1057. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berra E, Diaz-Meco M T, Dominguez I, Municio M M, Sanz L, Lozano J, Chapkin R S, Moscat J. Protein kinase C zeta isoform is critical for mitogenic signal transduction. Cell. 1993;74:555–563. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80056-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berra E, Diaz-Meco M T, Lozano J, Frutos S, Municio M M, Sanchez P, Sanz L, Moscat J. Evidence for a role of MEK and MAPK during signal transduction by protein kinase C zeta. EMBO J. 1995;14:6157–6163. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00306.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bjorkoy G, Overvatn A, Diaz-Meco M T, Moscat J, Johansen T. Evidence for a bifurcation of the mitogenic signaling pathway activated by Ras and phosphatidylcholine-hydrolyzing phospholipase C. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:21299–21306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.36.21299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bjorkoy G, Perander M, Overvatn A, Johansen T. Reversion of Ras- and phosphatidylcholine-hydrolyzing phospholipase C-mediated transformation of NIH 3T3 cells by a dominant interfering mutant of protein kinase C lambda is accompanied by the loss of constitutive nuclear mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase activity. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:11557–11565. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.17.11557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boghaert E R, Sells S F, Walid A J, Malone P, Williams N M, Weinstein M H, Strange R, Rangnekar V M. Immunohistochemical analysis of the proapoptotic protein Par-4 in normal rat tissues. Cell Growth Differ. 1997;8:881–890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao Z, Henzel W J, Gao X. IRAK: a kinase associated with the interleukin-1 receptor. Science. 1996;271:1128–1131. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5252.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cao Z, Xiong J, Takeuchi M, Kurama T, Goeddel D V. TRAF6 is a signal transducer for interleukin-1. Nature. 1996;383:443–446. doi: 10.1038/383443a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chao T H, Hayashi M, Tapping R I, Kato Y, Lee J D. MEKK3 directly regulates MEK5 activity as part of the big mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 (BMK1) signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:36035–36038. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chu W M, Ostertag D, Li Z W, Chang L, Chen Y, Hu Y, Williams B, Perrault J, Karin M. JNK2 and IKKbeta are required for activating the innate response to viral infection. Immunity. 1999;11:721–731. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colledge M, Scott J D. AKAPs: from structure to function. Trends Cell Biol. 1999;9:216–221. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(99)01558-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis R J. Signal transduction by the c-Jun N-terminal kinase. Biochem Soc Symp. 1999;64:1–12. doi: 10.1515/9781400865048.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diaz-Meco M T, Berra E, Municio M M, Sanz L, Lozano J, Dominguez I, Diaz-Golpe V, Lain de Lera M T, Alcami J, Paya C V, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Virelizier J-L, Moscat J. A dominant negative protein kinase C ζ subspecies blocks NF-κB activation. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:4770–4775. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.8.4770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diaz-Meco M T, Dominguez I, Sanz L, Dent P, Lozano J, Municio M M, Berra E, Hay R T, Sturgill T W, Moscat J. zeta PKC induces phosphorylation and inactivation of I kappa B-alpha in vitro. EMBO J. 1994;13:2842–2848. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06578.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diaz-Meco M T, Lallena M J, Monjas A, Frutos S, Moscat J. Inactivation of the inhibitory kappaB protein kinase/nuclear factor kappaB pathway by Par-4 expression potentiates tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19606–19612. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.28.19606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diaz-Meco M T, Lozano J, Municio M M, Berra E, Frutos S, Sanz L, Moscat J. Evidence for the in vitro and in vivo interaction of Ras with protein kinase C zeta. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:31706–31710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diaz-Meco M T, Municio M M, Frutos S, Sanchez P, Lozano J, Sanz L, Moscat J. The product of par-4, a gene induced during apoptosis, interacts selectively with the atypical isoforms of protein kinase C. Cell. 1996;86:777–786. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80152-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21a.Diaz-Meco M T, Moscat J. The atypical protein kinase Cs. Functional specificity mediated by specific protein adapters. EMBO Rep. 2000;1:399–403. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dominguez I, Diaz-Meco M T, Municio M M, Berra E, García de Herreros A, Cornet M E, Sanz L, Moscat J. Evidence for a role of protein kinase C ζ subspecies in maturation of Xenopus laevis oocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:3776–3783. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.9.3776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dominguez I, Sanz L, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Diaz-Meco M T, Virelizier J L, Moscat J. Inhibition of protein kinase C ζ subspecies blocks the activation of an NF-κ B-like activity in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:1290–1295. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.2.1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.English J M, Pearson G, Baer R, Cobb M H. Identification of substrates and regulators of the mitogen-activated protein kinase ERK5 using chimeric protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:3854–3860. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.7.3854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.English J M, Vanderbilt C A, Xu S, Marcus S, Cobb M H. Isolation of MEK5 and differential expression of alternatively spliced forms. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:28897–28902. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.48.28897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fitzgerald K A, Bowie A G, Skeffington B S, O'Neill L A. Ras, protein kinase C zeta, and I kappa B kinases 1 and 2 are downstream effectors of CD44 during the activation of NF-kappa B by hyaluronic acid fragments in T-24 carcinoma cells. J Immunol. 2000;164:2053–2063. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Folgueira L, McElhinny J A, Bren G D, MacMorran W S, Diaz-Meco M T, Moscat J, Paya C V. Protein kinase C-ζ mediates NF-κ B activation in human immunodeficiency virus-infected monocytes. J Virol. 1996;70:223–231. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.223-231.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guo Q, Fu W, Xie J, Luo H, Sells S F, Geddes J W, Bondada V, Rangnekar V M, Mattson M P. Par-4 is a mediator of neuronal degeneration associated with the pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease. Nat Med. 1998;4:957–962. doi: 10.1038/nm0898-957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hsu H, Huang J, Shu H B, Baichwal V, Goeddel D V. TNF-dependent recruitment of the protein kinase RIP to the TNF receptor-1 signaling complex. Immunity. 1996;4:387–396. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80252-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jamieson L, Carpenter L, Biden T J, Fields A P. Protein kinase Ciota activity is necessary for Bcr-Abl-mediated resistance to drug-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:3927–3930. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.7.3927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joberty G, Petersen C, Gao L, Macara I G. The cell-polarity protein par6 links par3 and atypical protein kinase C to cdc42. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:531–539. doi: 10.1038/35019573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kamakura S, Moriguchi T, Nishida E. Activation of the protein kinase ERK5/BMK1 by receptor tyrosine kinases. Identification and characterization of a signaling pathway to the nucleus. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26563–26571. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.37.26563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kampfer S, Hellbert K, Villunger A, Doppler W, Baier G, Grunicke H H, Uberall F. Transcriptional activation of c-fos by oncogenic Ha-Ras in mouse mammary epithelial cells requires the combined activities of PKC-lambda, epsilon and zeta. EMBO J. 1998;17:4046–4055. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.14.4046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kato Y, Kravchenko V V, Tapping R I, Han J, Ulevitch R J, Lee J D. BMK1/ERK5 regulates serum-induced early gene expression through transcription factor MEF2C. EMBO J. 1997;16:7054–7066. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.23.7054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kato Y, Tapping R I, Huang S, Watson M H, Ulevitch R J, Lee J D. Bmk1/Erk5 is required for cell proliferation induced by epidermal growth factor. Nature. 1998;395:713–716. doi: 10.1038/27234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kelliher M A, Grimm S, Ishida Y, Kuo F, Stanger B Z, Leder P. The death domain kinase RIP mediates the TNF-induced NF-kappaB signal. Immunity. 1998;8:297–303. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80535-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kovary K, Bravo R. Existence of different Fos/Jun complexes during the G0-to-G1 transition and during exponential growth in mouse fibroblasts: differential role of Fos proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:5015–5023. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.11.5015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kyriakis J M, Avruch J. Sounding the alarm: protein kinase cascades activated by stress and inflammation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:24313–24316. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.40.24313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liao D F, Monia B, Dean N, Berk B C. Protein kinase C-zeta mediates angiotensin II activation of ERK1/2 in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:6146–6150. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.10.6146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin D, Edwards A S, Fawcett J P, Mbamalu G, Scott J D, Pawson T. A mammalian PAR-3-PAR-6 complex implicated in Cdc42/Rac1 and aPKC signalling and cell polarity. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:540–547. doi: 10.1038/35019582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lomaga M A, Yeh W C, Sarosi I, Duncan G S, Furlonger C, Ho A, Morony S, Capparelli C, Van G, Kaufman S, van der Heiden A, Itie A, Wakeham A, Khoo W, Sasaki T, Cao Z, Penninger J M, Paige C J, Lacey D L, Dunstan C R, Boyle W J, Goeddel D V, Mak T W. TRAF6 deficiency results in osteopetrosis and defective interleukin-1, CD40, and LPS signaling. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1015–1024. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.8.1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mochly-Rosen D. Localization of protein kinases by anchoring proteins: a theme in signal transduction. Science. 1995;268:247–251. doi: 10.1126/science.7716516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mochly-Rosen D, Gordon A S. Anchoring proteins for protein kinase C: a means for isozyme selectivity. FASEB J. 1998;12:35–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Monick M M, Carter A B, Gudmundsson G, Mallampalli R, Powers L S, Hunninghake G W. A phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase C regulates activation of p42/44 mitogen-activated protein kinases in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human alveolar macrophages. J Immunol. 1999;162:3005–3012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murray N R, Fields A P. Atypical protein kinase C iota protects human leukemia cells against drug-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:27521–27524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.27521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nishida E, Gotoh Y. The MAP kinase cascade is essential for diverse signal transduction pathways. Trends Biochem Sci. 1993;18:128–131. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(93)90019-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Puls A, Schmidt S, Grawe F, Stabel S. Interaction of protein kinase C zeta with ZIP, a novel protein kinase C-binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6191–6196. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qiu R G, Abo A, Steven Martin G. A human homolog of the C. elegans polarity determinant par-6 links rac and cdc42 to PKCzeta signaling and cell transformation. Curr Biol. 2000;10:697–707. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00535-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Robinson M J, Cobb M H. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:180–186. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sajan M P, Standaert M L, Bandyopadhyay G, Quon M J, Burke T R, Jr, Farese R V. Protein kinase C-zeta and phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 are required for insulin-induced activation of ERK in rat adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:30495–30500. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sanchez P, De Carcer G, Sandoval I V, Moscat J, Diaz-Meco M T. Localization of atypical protein kinase C isoforms into lysosome-targeted endosomes through interaction with p62. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3069–3080. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.3069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sanz L, Diaz-Meco M T, Nakano H, Moscat J. The atypical PKC-interacting protein p62 channels NF-kappaB activation by the IL-1-TRAF6 pathway. EMBO J. 2000;19:1576–1586. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.7.1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sanz L, Sanchez P, Lallena M J, Diaz-Meco M T, Moscat J. The interaction of p62 with RIP links the atypical PKCs to NF-kappaB activation. EMBO J. 1999;18:3044–3053. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.11.3044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schönwasser D C, Marais R M, Marshall C J, Parker P J. Activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway by conventional, novel, and atypical protein kinase C isotypes. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:790–798. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schreiber M, Kolbus A, Piu F, Szabowski A, Mohle-Steinlein U, Tian J, Karin M, Angel P, Wagner E F. Control of cell cycle progression by c-Jun is p53 dependent. Genes Dev. 1999;13:607–619. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.5.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sells S F, Wood D P, Jr, Joshi-Barve S S, Muthukumar S, Jacob R J, Crist S A, Humphreys S, Rangnekar V M. Commonality of the gene programs induced by effectors of apoptosis in androgen-dependent and -independent prostate cells. Cell Growth Differ. 1994;5:457–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sontag E, Sontag J M, Garcia A. Protein phosphatase 2A is a critical regulator of protein kinase C zeta signaling targeted by SV40 small t to promote cell growth and NF-kappaB activation. EMBO J. 1997;16:5662–5671. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.18.5662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Takeda H, Matozaki T, Takada T, Noguchi T, Yamao T, Tsuda M, Ochi F, Fukunaga K, Inagaki K, Kasuga M. PI 3-kinase gamma and protein kinase C-zeta mediate RAS-independent activation of MAP kinase by a Gi protein-coupled receptor. EMBO J. 1999;18:386–395. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.2.386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thomas J A, Allen J L, Tsen M, Dubnicoff T, Danao J, Liao X C, Cao Z, Wasserman S A. Impaired cytokine signaling in mice lacking the IL-1 receptor-associated kinase. J Immunol. 1999;163:978–984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Treisman R. Regulation of transcription by MAP kinase cascades. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996;8:205–215. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80067-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Uberall F, Hellbert K, Kampfer S, Maly K, Villunger A, Spitaler M, Mwanjewe J, Baier-Bitterlich G, Baier G, Grunicke H H. Evidence that atypical protein kinase C-lambda and atypical protein kinase C-zeta participate in ras-mediated reorganization of the F-actin cytoskeleton. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:413–425. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.3.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van Dijk M C, Hilkmann H, van Blitterswijk W J. Platelet-derived growth factor activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase depends on the sequential activation of phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase C, protein kinase C-zeta and Raf-1. Biochem J. 1997;325:303–307. doi: 10.1042/bj3250303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang Y M, Seibenhener M L, Vandenplas M L, Wooten M W. Atypical PKC zeta is activated by ceramide, resulting in coactivation of NF-kappaB/JNK kinase and cell survival. J Neurosci Res. 1999;55:293–302. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990201)55:3<293::AID-JNR4>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wooten M W. Function for NF-kB in neuronal survival: regulation by atypical protein kinase C. J Neurosci Res. 1999;58:607–611. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4547(19991201)58:5<607::aid-jnr1>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wooten M W, Seibenhener M L, Matthews L H, Zhou G, Coleman E S. Modulation of zeta-protein kinase C by cyclic AMP in PC12 cells occurs through phosphorylation by protein kinase A. J Neurochem. 1996;67:1023–1031. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67031023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wooten M W, Seibenhener M L, Zhou G, Vandenplas M L, Tan T H. Overexpression of atypical PKC in PC12 cells enhances NGF-responsiveness and survival through an NF-kappaB dependent pathway. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:753–764. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhou G, Bao Z Q, Dixon J E. Components of a new human protein kinase signal transduction pathway. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:12665–12669. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.21.12665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]