Abstract

Objective

Evaluate the association of the interaction between the use of dental services and the skin colour on the occurrence of dental pain over time.

Material and methods

This study is a cohort with 10 years of follow-up, started in 2010 with a sample of 639 preschool children (1–5 years old). The use of dental services, race and the presence of dental pain were self-reported by the individuals according to predefined criteria. Multilevel logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the interaction between skin colour and use of dental services in the occurrence of dental pain over time.

Results

About 449 and 429 were reassessed in 2017 and 2020, respectively. The occurrence of dental pain across the cohort was 60.7%. Caucasian individuals who used dental services throughout the cohort had a 51% lower chance of having a dental pain than those who used dental services but were non-white (OR 0.49; 95% IC 0.27–0.90).

Conclusion

There was a racial inequity in the occurrence of dental pain among individuals who managed to make use of dental services throughout the follow-ups.

Clinical relevance

The differences found should serve as a warning to the way how individuals with different characteristics are treated and must be used to combat this inequity. Individuals should receive resolute and personalized treatments according to their clinical condition and not according to their socioeconomic characteristics.

Keywords: Adolescence, Longitudinal study, Oral health, Dental care, Race factors, Dental pain

Introduction

Oral diseases remained highly prevalent around the world and affect populations unevenly, being more concentrated in socially disadvantaged groups [1–4]. Furthermore, the global burden of oral diseases impacts high economic costs [5], especially in countries with lower socioeconomic backgrounds [6–9], as well as in the daily life and well-being of the affected individuals [10]. Thus, the effects of socioeconomic, demographic and behavioural characteristics on oral health have been previously explored [10–14].

Among these factors is the use of dental services, which have been considered an important indicator of levels of oral health in children and adults [13, 15]. In Brazil, the prevalence of use of dental services in the last year is around 40% when considering the age group of children [16]. In relation to the pattern of use, it was found that only 35% of these use dental services for routine or preventive reasons. In addition, about 50% of individuals in childhood and adolescence tend to use the public health system, especially those belonging to lower-income groups [16].

Previous studies have shown that individuals who seek the service for preventive reasons, or that lived in neighbourhoods that have dentists in public services, were more likely to present better oral health outcomes [13, 17]. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that non-white individuals have worse oral health status and lower rates of use of dental services compared to their counterparts [18–20]. Race has been considered a structural health determinant [21] which influences psychosocial, behavioural and biological factors, leading to poorer oral health, and also has been related to work relationships, educational levels and income [22], which may impact individuals’ behaviours and knowledge in relation to their oral health [23].

Among the oral health outcomes affected by sociodemographic and behavioural conditions is the dental pain, which has been explored in studies considering different populations [23–26]. Pain can be defined as an unpleasant symptom and emotional experience caused by tissue damage [27, 28]. Dental pain has been reported as the most frequent type of orofacial pain and can affect social interaction and daily activities, and negatively impact the oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) [27, 29–32]. Therefore, dental pain can be considered a multifactorial health problem and an important outcome to be considered, especially during infancy and adolescence, a period of important biopsychosocial changes.

Although some previous studies have evaluated the impact of the use of services and ethnicity on dental pain occurrence, the impact of the use/reason for dental service on dental pain according to the individual’s skin colour has not yet been explored [33, 34]. Studying the effect of the interaction between these variables is important when assessing inequalities in oral health outcomes and could be useful for public health planning and prevention of oral health diseases. Thus, this study aimed to evaluate the impact of the use of dental services and the reason for dental attendance in the report of dental pain according to the skin colour of the adolescents. Our conceptual hypothesis is that non-white individuals who have used the dental services over the years, and whose reason was for preventive treatments, were more likely to have dental pain than white individuals with the same pattern of use.

Material and methods

Study design

This is a prospective cohort study with 10 years of follow-up. This project involved the baseline and 3 follow-up evaluations in the years 2012 (2 years), 2017 (7 years) and 2020 (10 years). The present study considered baseline data in 2010 (T1) and follow-up data in 2017 (T2) and 2020 (T3). This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Santa Maria (CAAE 54257216.1.0000.5346). Data were only collected after the parents/guardians of the participants consented and signed the informed consent form.

Baseline assessment

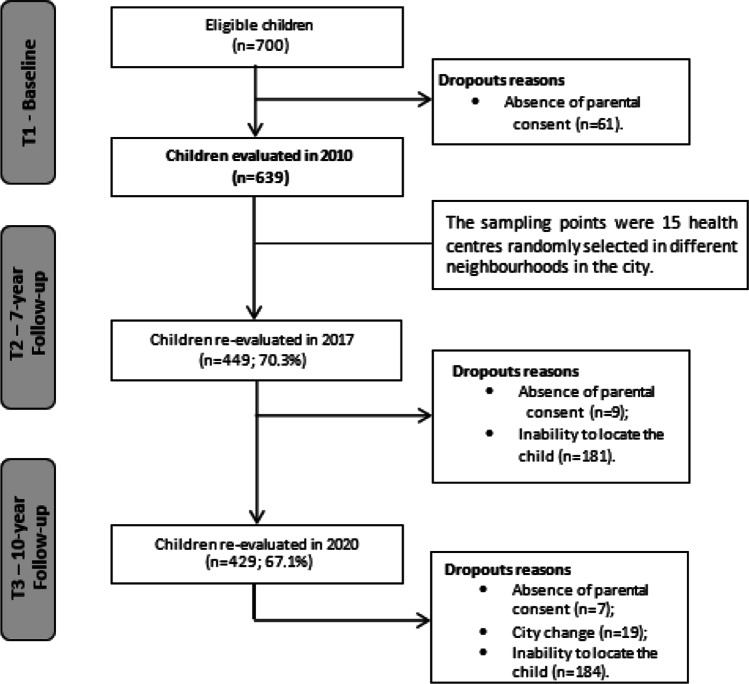

The baseline evaluation was carried out in 2010, during the National Children’s Vaccination Day in the city of Santa Maria, southern Brazil. The estimated population of the city in 2010 was 263,403 inhabitants, which included 27,520 children under 6 years old. Data collection began with an epidemiological survey of oral health, where a random sample of 639 preschool children aged 1 to 5 years was evaluated. The sampling points were 15 basic health centres that contained a dental chair, well distributed in the 8 administrative regions of the city. These health centres were the largest in the city and covered around 85% of the children in the city. At the time of collection, children were systematically selected, for every 5 positions in the queue. Individuals with some cognitive impairments were not considered eligible (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the three data collection periods

To calculate the sample size, we considered a standard error of 5%, a confidence level of 95% and a prevalence of dental pain of 7.59% in the exposed group (individuals who did not use the dental service) and 18.05% in the unexposed group (individuals who used the dental service) [28]. The calculation considered an exposed to the non-exposed ratio of 1:1 and a statistical power of 80%. In addition, the design effect of 1.2 was considered to increase accuracy due to multistage sampling. The minimum sample size was determined at 377 children, to which 30% was added to compensate for possible losses in follow-up, resulting in an initial sample of 490 pre-schoolers aged 1 to 5 years.

Follow-up assessments

Data collection from 7 years of follow-up was carried out during the year 2017, and considered all children evaluated at baseline (n=639). These individuals, who at that time were aged between 8 and 12 years, were again invited to participate in the evaluations. Other details and the results of the second phase of the study have already been published [35, 36].

Posteriorly, individuals were evaluated between 2019 and 2021, totalling 10 years of follow-up. In this moment, the individuals were between 11 and 15 years old and were already considered adolescents. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, these data collection procedures were suspended in March 2020 and recaptured in October of the same year. Other details and the results of the second phase of the study have already been published [37].

In both follow-up periods, children were sought and re-evaluated at their respective schools or during home visits. The personal data was constantly updated through phone calls or social networks, such as WhatsApp or Facebook. In the same way as in the previous stage, the children were located and invited, together with their families, to participate in the new cohort wave.

Evaluated measures

The outcome variable, dental pain, was subjectively collected at T2 and T3 through the following question: “Has your child ever had an episode of dental pain?” and, if the answer was positive, the time elapsed since the last occurrence was questioned from the options “less than 6 months”, “6 months to 1 year” and “more than 1 year”. This approach has already been used in previous studies [29, 30, 38]. For data analysis, it was considered whether the individual presented any dental pain episodes at T2 and/or T3 (0= not; 1= yes).

The behaviour of individuals in relation to the use of dental services and the reason for the last dental appointment were investigated at T1, T2 and T3. Regarding the use of dental services, the following question was asked to those caregivers: “Has your child used any dental service during the last year?”, with the answer options “yes” or “no”. This question has already been used in previous studies [13, 35]. For data analysis, the use of dental services throughout the cohort assessment periods was considered (0= not; 1= yes). The reasons for the last dental appointment were the following: 1= restorative issues; 2= extractions (due to dental caries), 3= urgent treatments or 4= preventive treatments (hygiene guidance, diagnosis, orthodontic treatment). For analysis purposes, the reason for the last dental appointment was dichotomized into routine (4) and non-routine (1, 2 and 3). For the longitudinal data analysis, the children were classified according to the trajectory for the reason for dental appointments as the following: 0= routine use (always for routine reasons or that change from non-routine to routine throughout the cohort-improvement) and 1= non-routine use (always for non-routine/treatment reasons, or that change from routine for non-routine throughout the cohort—worsening) [13].

Skin colours were collected at baseline according to the criteria established by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), which is performed in population-based surveys [39] using the following question: “What race do you consider your child to be?”, with the response options: 1= “white”, 2= “brown”, 3= “black”, 4= “yellow” or 5= “indigenous”. For data analysis, skin colour was dichotomized as whites (0) or non-whites (2, 3, 4 and 5). This approach has already been used in previous studies that collected this variable [12, 17] since southern Brazil presented few inhabitants with delicate skin colours such as brown, yellow or indigenous [22], generating very low frequencies in these categories.

Sex (boys and girls), age (in years), household income and dental caries were measured as possible confounders. Household income was collected as the mean monthly family income in Reais (Brazilian currency—US $1.00 is equivalent to R$5, approximately) and categorized into income quartiles. For the oral examination regarding the presence of dental caries, the International Caries Detection and Assessment System was used (ICDAS) [40]. Data regarding the children’s oral conditions were obtained through clinical examinations carried out in health centres at baseline or in the schools or homes at follow-ups. During data collection, all examiners were previously trained and calibrated (inter- and intra-examiner kappa coefficients ranged from 0.70 to 0.96), and conducted clinical examinations with the aid of gauze, CPI probe and a clinical mirror [41]. For data analysis, dental caries was considered according to the number of teeth with the presence of cavitated lesions (ICDAS code 3, 5 or 6). The ICDAS code 4 was not considered, as in previous studies with this same sample and, to maintain the consistency with these previous studies, the same approach was maintained [13, 30].

Data analysis

Data were analysed using the statistical program STATA 14.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). A descriptive analysis was performed to evaluate the characteristics of the sample, considering the sample weight (“svy” command). The comparison between followed and dropouts’ individuals over time, as well as those evaluated before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, was performed using the t-test (quantitative variables) and the chi-square test (qualitative variables). The study outcome was the occurrence of episodes of dental pain in 2017 and 2020.

Multilevel logistic regression models were used to assess the interaction between variables regarding the use of dental services and skin colour in the report of dental pain over time. Moderation effects occur when the relationship between two variables is modified according to a third variable [42]. Our data were tested on a scale of multiplicative interactions, as in previous studies [37, 43]. The multilevel structure of analysis considered individuals (level 1) nested in the 15 neighbourhoods (level 2). A fixed-effect model with random intercept was used. Unadjusted analysis assessed the association between dental pain, skin colour and possible confounders (i.e. age, household income and dental caries). Variables that presented p<0.20 in the unadjusted analysis were included in adjusted models. Results are presented in odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

Results

Of the 639 children assessed at baseline, 449 were followed in 2017 (70.3% response rate) and 429 were reassessed in 2020 (67.1% response rate). The dropouts were due to not locating the individuals and refusal. There was no difference in sample characteristics between individuals who were followed and dropouts, nor between those evaluated before and after the COVID-19 pandemic (p>0.05).

Table 1 displays the characteristics of the sample throughout the cohort for children followed for 10 years. Of the children re-examined, 52% were girls and 51.5% were non-white. The mean age at 10-year follow-up was 12.6 years (standard error 0.1). The percentage of children with at least one cavitated caries lesion was 30.6%. Approximately 56.9% of individuals did not use dental services and 11.5% presented a poor trajectory regarding the reason for using dental services. The prevalence of dental pain during follow-ups was 60.7%.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample throughout the cohort for children followed for 10 years (n=429)

| Variables | N (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic and socioeconomic variables | ||

| Sex | 0.227 | |

| Boys | 209 (48.0) | |

| Girls | 220 (52.0) | |

| Age (mean [SE]) | 12.6 (0.1) | 0.05 |

| Skin colour | 0.158 | |

| White | 215 (48.5) | |

| Non-white | 211 (51.5) | |

| Household income quartiles in Reals (R$) | 0.300 | |

| Quartile 1, lowest | 110 (25.6) | |

| Quartile 2 | 79 (18.4) | |

| Quartile 3 | 108 (25.2) | |

| Quartile 4, highest | 77 (17.9) | |

| Behavioural variable | ||

| Use of dental services in the last year | - | |

| Yes | 179 (43.1) | |

| Not | 250 (56.9) | |

| Reason for dental attendance | - | |

| Routine | 322 (88.5) | |

| Not routine | 42 (11.5) | |

| Oral health variables | ||

| Dental pain | - | |

| Absent | 162 (39.2) | |

| Present | 250 (60.7) | |

| Untreated dental caries | 0.774 | |

| Absent | 300 (69.4) | |

| Present | 129 (30.6) | |

SE, standard error; R$, Brazilian Real (US $1.00 is equivalent to R$ 5.4 approximately)

Taking into account the sampling weight; values lower than 429 are due to missing data. P-value refers to the comparison between participants in the follow-up and dropouts, and between individuals evaluated before and during the COVID-19 pandemic

Descriptive analyses of the use of dental services according to skin colour are presented in Table 2. Among the individuals who used the dental service, 76.6% had white skin colour and 23.4% were non-white. Regarding the trajectory of dental attendance, 23.8% of non-white individuals had a non-routine use trajectory over time.

Table 2.

Descriptive analysis of the use of dental services according to skin colour

| Variables | Skin colour N (%)* | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| White | Non-white | p-value | |

| Use of dental service in the last year | 0.688 | ||

| Yes | 305 (97.1) | 93 (97.9) | |

| Not | 9 (2.9) | 2 (2.1) | |

| Reason for dental attendance | 0.905 | ||

| Routine | 248 (88.5) | 74 (88.1) | |

| Not routine | 32 (11.5) | 10 (11.9) | |

*Taking into account the sampling weight. Values lower than 429 are due to missing data

Unadjusted analysis between the use of dental services, skin colour and dental pain is presented in Table 3. A significant association was found between the interaction of the variables use of services and skin colour and dental pain during the follow-ups (p < 0.05).

Table 3.

Unadjusted analysis of the predictor variables and interaction of skin colour and use of dental service in the last year on dental pain throughout 10 years cohort

| Variables | Dental pain | |

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Skin colour#use of dental service in the last year | ||

| Non-white#yes | 1 | |

| White#yes | 0.51 (0.31–0.85) | 0.010 |

| White#not | 1.30 (0.25–6.77) | 0.754 |

| Non-white#not | 0.36 (0.20–6.13) | 0.477 |

| Skin colour#reason for dental attendance | ||

| Non-white#routine | 1 | |

| White#routine | 0.47 (0.26–0.85) | 0.014 |

| White#not routine | 0.30 (0.12–0.73) | 0.008 |

| Non-white#not routine | 0.32 (0.08–1.25) | 0.102 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; #, interaction among variables

Table 4 shows that among those who have used the dental service over the follow-up periods, white individuals presented a 46% lower chance of experiencing dental pain (OR 0.54; 95% CI 0.32–0.93) than non-white individuals. Considering the reasons for dental attendance, white individuals who presented both routine and non-routine trajectory of use of dental service had 52% (OR 0.48; 95% CI 0.25–0.91) and 76% (OR 0.24; 95% CI 0.09–0.63) lower chances of having dental pain than non-white individuals who had a routine trajectory of using dental services.

Table 4.

Adjusted analysis of the predictor variables and interaction of skin colour and use of dental services on dental pain throughout the 10 years of cohort

| Variables | Dental pain | |

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI)* | p-value | |

| Skin colour#use of dental service in the last year | ||

| Non-white#yes | 1 | |

| White#yes | 0.54 (0.32–0.93) | 0.028 |

| White#not | 1.51 (0.28–8.10) | 0.627 |

| Non-white#not | 0.33 (0.01–5.84) | 0.456 |

| Skin colour#reason for dental attendance | ||

| Non-white#routine | 1 | |

| White#routine | 0.48 (0.25–0.91) | 0.026 |

| White#not routine | 0.24 (0.09–0.63) | 0.004 |

| Non-white#not routine | 0.23 (0.05–1.01) | 0.053 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; #, interaction among variables

*Adjusted by sex, household income and untreated dental caries

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the impact of the use of dental services on dental pain according to skin colour among adolescents. Our findings confirm the conceptual hypothesis that non-white individuals who used dental services over time or that used the service for preventive reasons were more likely to present dental pain over time than white individuals with the same pattern of use. These results reinforce the idea that there are differences in dental attendance between white and non-white individuals.

Our findings evidenced a disparity in the odds of occurrence of dental pain among individuals of different skin colour who have used dental services at least once during the 10-year follow-up period. Non-white individuals were more likely to have dental pain, even when compared with white individuals who used dental services at least once over time. These results agree with some published studies that report a higher prevalence of dental pain among individuals declared to be non-white, regardless of other factors [44–46].

In this sense, we observed a racial inequity in solving the occurrence of dental pain from using dental services. A possible explanation for this finding is that professionals plan, execute and indicate different treatments according to skin colour, as shown in previous studies [20, 47, 48]. This approach disfavours those belonging to the non-white portion of the population and justifies the finding that, even after undergoing a dental appointment, non-white individuals presented more dental pain than their counterparts [20, 47, 48].

Considering the reason for the last dental appointment, our results showed that non-white individuals who have used the service for routine reasons over time were more likely to present dental pain than white individuals with the same pattern of use. This finding confirms the information previously discussed regarding the inequities in dental treatment according to skin colour, which may impact oral health outcomes, such as dental pain [13, 20, 49, 50]. These results have proven important and answer the research question. In addition, when considering not only the use of dental services but also the way in which the services are used, individuals with non-white skin colour are still more likely to have dental pain over time relative to their comparators. This finding highlights the potential of the “skin colour” variable to influence the occurrence of dental pain.

Comparing our findings with those found in previous studies, it is possible to observe that the prevalence of use of dental services in our sample was higher, in both whites (97.1%) and non-whites (97.9%). Some authors report a prevalence of use of 59.8% for white individuals and 44.1% for non-white individuals in similar age groups [51]. Another study, when investigating the prevalence of use among adolescents, found that 58.4% of those evaluated reported having had at least one dental appointment in the last year [52]. This high rate in our study is due to the way the variable was categorized, comprising the use of service in all cohort waves. This result is in line with data from another study that collected this variable in adolescents from the question “have you ever had a dentist appointment in your life?”, and pointed to a prevalence of positive responses in 90.9% of respondents [49].

Debating the reason for the last dental appointment, a study shows that 61.1% of adolescents sought dental services for non-preventive reasons. Other surveys in a similar age group showed that less than half of the individuals reported seeking dental care for preventive reasons, revealing the curative character that dentistry still has at national and international levels [49, 53]. In comparison, our study showed that 88.5% of the individuals always used it for a preventive reason or have gone for preventive reasons during the follow-up to do so over time. The possible explanation for this high level of individuals using the services in a preventive way is given by the way in which the variable was treated, since it always considered the last consultations prior to the data collection stages, not taking into account possible non-preventive appointments between the periods. In addition, considering the trajectory of the form of use, individuals who initially used it in a curative way and started to do so in a preventive way over time were also part of the allocated portion in the “routine” group.

Regarding dental pain, our study showed a total prevalence of 60.7% in the follow-ups (T2 and T3). A previous systematic review presented occurrences of dental pain from 1.33 to 87.8% among individuals of similar age groups, reinforcing that the prevalence tends to vary according to the different methodologies used in the data gathering [54]. When comparing with another study with a similar age group and methodology developed in Brazil, our study showed a significantly higher prevalence of dental pain, and these differences can be explained due to the subjective nature of the variable and by the report by the parents or guardians [55].

It is also important to discuss the close relationship between skin colour, used as a predictor for the outcome of the study, and household income, also collected during the follow-up period. The literature has extensively shown that this relationship is consistent [22, 46, 56, 57]. Previous studies have demonstrated that white individuals, both in Brazil and in other countries, are responsible for the highest concentrations of income in their families. On the other hand, those individuals who self-declared as having black skin colour or other “non-white” categories have a greater chance of belonging to families with a lower household income [22, 56]. When evaluated as predictors for the occurrence of dental pain in studies with similar populations, both income and skin colour have been considered important predictors, with individuals with lower income and non-white skin colour being more affected by dental pain [46, 57]. These facts may potentiate the occurrence of dental pain in individuals with non-white skin colour since this class is related to lower income and both characteristics increase the chances of occurrence of the outcome.

This study has some limitations: it is possible that a selection bias arouses since some individuals were evaluated at T3 before and others during the COVID-19 pandemic. It may also have introduced a response bias regarding some behavioural factors, as well as in the occurrence of dental caries since it has demonstrated the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on oral health in this age group [58]. However, sensitivity analysis showed that this concern might not affect our findings. Furthermore, the measures regarding the use of dental services and dental pain were self-reported by participants’ parents or guardians, which may be subject to information bias. In this epidemiological study, skin colour, one of the main predictors, was broadly collected, as recommended by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) [39]. However, for data analysis, the variable was dichotomized into white and non-white individuals. This approach can limit the findings since it compiles individuals with different characteristics into the same group. Thus, possible differences among the categories grouped as non-whites may not have been explored deeply, since yellow, indigenous and especially brown and black people may have distinct realities, although both groups present poorer socioeconomic characteristics than white individuals [59]. Notwithstanding, despite emphasizing the importance of better differentiating groups, our categorization into whites and non-whites was due to the low frequency of individuals who self-declared as brown, yellow or indigenous. Another limitation of the study is the fact that we did not consider carious lesions with the ICDAS code 4, as performed in previous studies using the same sample [13, 30], which may decrease the detection of dental caries during clinical examinations.

Among the potential of the study, this is a longitudinal study with a long follow-up period and non-significant losses over time, as well as presented good response rates through the evaluation periods. In addition, the monitoring of a sample from early childhood to adolescence is of paramount importance since that provides relevant data regarding structural, behavioural and subjective variables collected during a biopsychosocial period, which can generate impacts during adulthood and persist during the years. Thus, studying these aspects during adolescence, a transitional phase characterized by a time of intense physical, psychological, affective and behavioural changes, is essential in order to provide evidence of the factors that affect this age group in general and specific groups, as belonging to the same socioeconomic class or with similar behaviours. These data can be of great value for health planning for these populations and should guide policies aimed at reducing inequalities in oral health.

Our findings concluded that among individuals who used the dental service, those who were of non-white skin colour were more likely to present dental pain, even if the reason for using the dental service was for routine preventive treatments. These findings reinforce the inequality present in the provision of dental services to individuals with different racial characteristics.

Author contributions

Mr. Rauber and Mrs. Knorst did the writing of the article and performed data collection and data analysis; Mrs. Noronha and Mrs. Zemolin performed data collection and revised the manuscript; Mr. Ardenghi collaborated with study conception and funding, and critically revised the text.

Funding

The Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq – process 161233/2021-0), Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul (FAPERGS – process 17/2551-0001083-3) and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES) – Finance Code 001.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Santa Maria (process 3.425.591).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Everton Daniel Rauber, Email: everrauber@gmail.com.

Jessica Klöckner Knorst, Email: jessicaknorst1@gmail.com.

Thiago Machado Ardenghi, Email: thiago.ardenghi@ufsm.br.

References

- 1.WHO (2003) The World Oral Health Report 2003: continuous improvement of oral health in the 21st century - the approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Geneva; World Health Organization [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.BRASIL, Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde, Departamento de Atenção Básica (2011) Projeto SB Brasil 2010: condições de saúde bucal da população brasileira 2010: resultados principais. Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde, Departamento de Atenção Básica. – Brasília: Ministério da Saúde, 2011

- 3.Marcenes W, Kassebaum NJ, Bernabe E, Flaxman A, Naghavi M, Lopez A, et al. Global burden of oral conditions in 1990-2010: a systematic analysis. Journal of Dental Research. 2013;92(7):592–7. doi: 10.1177/0022034513490168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gimenez T, Bispo BA, Souza DP, Viganó ME, Wanderley MT, et al. Does the decline in caries prevalence of Latin American and Caribbean children continue in the new century? Evidence from Systematic Review with Metanalysis. Plos One. 2016;21:11–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Listl S, Galloway J, Mossey PPA, Marcenes W. Global economic impact of dental diseases. J Dent Res. 2015;94(10):1355–1136. doi: 10.1177/0022034515602879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petersen PE (2003) The World Oral Health Report 2003: continuous improvement of oral health in the 21st century--the approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2(1):3–23 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Freire MCM, Reis SCGB, Figueiredo N, Peres KGP, Moreira RS, Antunes JLF. Individual and contextual determinants of dental caries in Brazilian 12-year-olds in 2010. Rev Saúde Pública. 2013;47(3):40–49. doi: 10.1590/s0034-8910.2013047004322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwendicke F, Dorfer CE, Schlattmann P, Foster-Page L, Thomson WM, Paris S. Socioeconomic inequality and caries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent Res. 2015;4:10–18. doi: 10.1177/0022034514557546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peres MA, Macpherson LMD, Weyant RJ, Daly B, Venturelli R, Mathur MR, Listl S, Celeste RK, Guarnizo-Herreño CC, Kearns C, Benzian H, Allison P, Rg W. Oral diseases: a global public health challenge. Lancet. 2019;394:249–260. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jin LJ, Lamster IB, Greenspan JS, Pitts NB, Scully C, Warnakulasuriya S. Global burden of oral diseases: emerging concepts, management and interplay with systemic health. Oral Dis. 2016;22(7):609–619. doi: 10.1111/odi.12428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guedes RS, Piovesan C, Antunes JL, Mendes FM, Ardenghi TM. Assessing individual and neighborhood social factors in child oral health-related quality of life: a multilevel analysis. Qual Life Res. 2014;23(9):2521–2530. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0690-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sfreddo CS, Moreira CHC, Celeste RK, Nicolau B, Ardenghi TM. Pathways of socioeconomic inequalities in gingival bleeding among adolescents. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2019;47(2):177–184. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Menegazzo GR, Knorst JK, Emmanuelli B, Mendes FM, Ardenghi DM, Ardenghi TM. Effect of routine dental attendance on child oral health-related quality of life: a cohort study. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2020;30(4):459–467. doi: 10.1111/ipd.12625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lopes RT, Neves ÉTB, Gomes MC, Paiva SM, Ferreira FM, Granville-Garcia AF. Family structure, sociodemographic factors and type of dental service associated with oral health literacy in the early adolescence. Cien Saude Colet. 2021;26(3):5241–5250. doi: 10.1590/1413-812320212611.3.34782019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silveira ER, Cademartori MG, Schuch HS, Corrêa MB, Ardenghi TM, Armfield J, Horta BL, Demarco FF (2021) The vicious cycle of dental fear at age 31 in a birth cohort in Southern Brazil. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 49(4):354–361 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Oliveira RF, Haikal DS, Carreiro DL, Silveira MF, Lima Martins AMEB. Equidade no uso de serviços odontológicos entre adolescentes brasileiros: uma análise multinível. Revista Brasileira de Geografia Médica e da Saúde. 2018;14(27):14–29. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moraes RB, Menegazzo GR, Knorst JK, Ardenghi TM (2020) Availability of public dental care service and dental caries increment in children: a cohort study. J Public Health Dent:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Boing AF, Bastos JL, Peres KG, Antunes JL, Peres MA. Social determinants of health and dental caries in Brazil: a systematic review of the literature between 1999 and 2010. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2014;17:102–115. doi: 10.1590/1809-4503201400060009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Souza JG, Costa Oliveira BE, Martins AM. Contextual and individual determinants of oral health-related quality of life in older Brazilians. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(5):1295–1302. doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1447-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chisini LA, Noronha TG, Ramos EC, Dos Santos-Junior RB, Sampaio KH, Faria-E-Silva AL, Corrêa MB. Does the skin colour of patients influence the treatment decision-making of dentists? A randomized questionnaire-based study. Clin Oral Investig. 2019;23(3):1023–1030. doi: 10.1007/s00784-018-2526-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Solar O, Irwin A (2010) A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Social Determinants of Health Discussion Paper 2 (Policy and Practice). Geneva; World Health Organization

- 22.IBGE (2019) Desigualdades Sociais por Cor ou Raça no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro; IBGE

- 23.Vilella KD, Alves SGA, De Souza JF, Fraiz FC, Assunção LRS. The association of oral health literacy and oral health knowledge with social determinants in pregnant Brazilian women. J Community Health. 2016;41(5):1027–1032. doi: 10.1007/s10900-016-0186-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mathias FB, Cademartori MG, Goettems ML. Factors associated with children’s perception of pain following dental treatment. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2020;21(1):137–143. doi: 10.1007/s40368-019-00456-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johal A, Ashari AB, Alamiri N, Fleming PS, Qureshi U, Cox S, Pandis N. Pain experience in adults undergoing treatment: a longitudinal evaluation. Angle Orthod. 2018;88(3):292–298. doi: 10.2319/082317-570.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wan S, Tao L, Liu M, Liu J. Prevalence of toothache in Chinese adults aged 65 years and above. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2021;49(6):522–532. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Locker D, Grushka M. The impact of dental and facial pain. J Dent Res. 1987;66(9):1414–1417. doi: 10.1177/00220345870660090101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Breivik H, Bond MJ. Why pain control matters in a world full of killer diseases. Pain Clinical Updates. 2004;12(4):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ortiz FR, Tomazoni F, Oliveira MDM, Piovesan C, Mendes FM, Ardenghi TM. Toothache, associated factors, and its impact on oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) in Preschool Children. Braz Dent J. 2014;25(6):546–553. doi: 10.1590/0103-6440201302439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rauber ED, Menegazzo GR, Knorst JK, Bolsson GB, Ardenghi TM. (2021) Pathways between toothache and children's oral health-related quality of life. Int J Paediatr Dent 31(5):558–564 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Krisdapong S, Prasertsom P, Rattanarangsima K, Sheiham A. School absence due to toothache associated with sociodemographic factors, dental caries status, and oral health-related quality of life in 12- and 15-year-old Thai children. J Public Health Dent. 2013;73(4):321–328. doi: 10.1111/jphd.12030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Freire MCM, Corrêa-Faria P, Costa LR. Effect of dental pain and caries on the quality of life of Brazilian preschool children. Rev Saude Publica. 2018;52:30. doi: 10.11606/S1518-8787.2018052000093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Darley RM, Karam SA, Costa FDS, Correa MB, Demarco FF. Association between dental pain, use of dental services and school absenteeism: 2015 National School Health Survey, Brazil. Epidemiol Serv Saude. 2021;30(1):e2020108. doi: 10.1590/S1679-49742021000100011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boeira GF, Correa MB, Peres KG, Peres MA, Santos IS, Matijasevich A, Barros AJ, Demarco FF. Caries is the main cause for dental pain in childhood: findings from a birth cohort. Caries Res. 2012;46(5):488–495. doi: 10.1159/000339491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knorst JK, Menegazzo GR, Emmanuelli B, et al. Effect of neighborhood and individual social capital in early childhood on oral health-related quality of life: a 7-year cohort study. Qual Life Res. 2019;28:1773–1782. doi: 10.1007/s11136-019-02138-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tondolo Junior J, Knorst JK, Menegazzo GR, Emmanuelli B, Ardenghi TM. Influence of malocclusion on oral health-related quality of life in children: a seven-year cohort study. Dent Press J Orthod. 2021;26(2):1–23. doi: 10.1590/2177-6709.26.2.e2119244.oar. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knorst JK, Vettore MV, Brondani B, Emmanuelli B, Tomazoni F, Ardenghi TM. Sense of coherence moderates the relationship between social capital and oral health-related quality of life in schoolchildren: a 10-year cohort study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2022;20(1):56. doi: 10.1186/s12955-022-01965-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silva-Júnior IF, Hartwig AD, Goettems ML, Azevedo MS. Comparative study of dental pain between children with and without a history of maltreatment. J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2019;33(3):287–293. doi: 10.11607/ofph.2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.IBGE (2010) Síntese de Indicadores Sociais. Uma análise das condições de vida da população brasileira. Rio de Janeiro; IBGE

- 40.Ismail AISW, Sohn W, Tellez M, Amaya A, Hasson HB. The International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS): an integrated system for measuring dental caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2007;35:170–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.World Health Organization- WHO (2013) Oral Health Surveys: Basic Methods 5th edition. Geneva; World Health Organization

- 42.Igartua JJ, Hayes AF. Mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: concepts, computations, and some common confusions. Span J Psychol. 2021;24:e49. doi: 10.1017/SJP.2021.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Machado FW, Perroni AP, Nascimento GG, Goettems ML, Boscato N. Does the sense of coherence modifies the relationship of oral clinical conditions and oral health-related quality of life? Qual Life Res. 2017;26(8):2181–2187. doi: 10.1007/s11136-017-1558-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peres MA, Peres KG, Frias AC, Antunes JL. Contextual and individual assessment of dental pain period prevalence in adolescents: a multilevel approach. BMC Oral Health. 2010;10:20. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-10-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gupta N, Vujicic M, Yarbrough C, Harrison B. Disparities in untreated caries among children and adults in the U.S., 2011-2014. BMC Oral Health. 2018;18(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12903-018-0493-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Costa F, Wendt A, Costa C, Chisini LA, Agostini B, Neves R, Flores T, Correa MB, Demarco F (2021) Racial and regional inequalities of dental pain in adolescents: Brazilian National Survey of School Health (PeNSE), 2009 to 2015. Cad Saude Publica 37(6) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Plessas A. To what extent do patients’ racial characteristics affect our clinical decisions? Evid Based Dent. 2019;20(4):101–102. doi: 10.1038/s41432-019-0062-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patel N, Patel S, Cotti E, Bardini G, Mannocci F. Unconscious racial bias may affect dentists’ clinical decisions on tooth restorability: a randomized clinical trial. JDR Clin Trans Res. 2019;4(1):19–28. doi: 10.1177/2380084418812886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Massoni ACLT, Porto É, Ferreira LRBO, Silva HP, Gomes MDNC, Perazzo MF, D'avila S, Granville-Garcia AF. Access to oral healthcare services of adolescents of a large-size municipality in northeastern Brazil. Braz Oral Res. 2020;34:29. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107bor-2020.vol34.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ofili DC, Esu EB, Ejemot-Nwadiaro RI. Oral hygiene practices and utilization of oral healthcare services among in-school adolescents in Calabar, Cross River State, Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;36:300. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2020.36.300.25102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Robison V, Wei L, Hsia J (2020) Racial/Ethnic Disparities Among US Children and Adolescents in Use of Dental Care. Prev Chronic Dis 30;17:E71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Araújo Júnior CAS, Rebelo Vieira JM, Rebelo MAB, Herkrath FJ, Herkrath APCQ, de Queiroz AC, Pereira JV, Vettore MV. The influence of change on sense of coherence on dental services use among adolescents: a two-year prospective follow-up study. BMC Oral Health. 2021;21(1):663. doi: 10.1186/s12903-021-02026-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hadler-Olsen E, Jönsson B. Oral health and use of dental services in different stages of adulthood in Norway: a cross sectional study. BMC Oral Health. 2021;21(1):257. doi: 10.1186/s12903-021-01626-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pentapati KC, Yeturu SK, Siddiq H. Global and regional estimates of dental pain among children and adolescents-systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2021;22(1):1–12. doi: 10.1007/s40368-020-00545-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Macedo TFF, Abreu MHNG, Castro Martins R, Matta-Machado ATG, da Silveira PR, de Castilho LS, Vargas-Ferreira F. Contextual and individual factors associated with dental pain in adolescents from Southeastern Brazil. Braz Oral Res. 2021;35:6–9. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107bor-2021.vol35.0111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Grusky David, Varner Charles, MATTINGLY MARYBETH. Pathways magazine. Stanford, CA: Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Costa NC, Abreu MHNG, Pinto RS, Vargas-Ferreira F, Martins RC (2022) Factors associated with toothache in 12-year-old adolescents in a southeastern state of Brazil. Braz Oral Res 36:e57 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Brondani B, Knorst JK, Tomazoni F, Cósta MD, Vargas AW, Noronha TG, Mendes FM, Ardenghi TM. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on behavioural and psychosocial factors related to oral health in adolescents: a cohort study. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2021;31(4):539–546. doi: 10.1111/ipd.12784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Muniz JO. Sobre o uso da variável raça-cor em estudos quantitativos. Revista de Sociologia e Política. 2010;18(36):277–291. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.