Abstract

Social withdrawal and isolation are frequently experienced among people with cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease, and Alzheimer’s disease related dementias. Few assistive technologies exist to support persons with memory concerns’ (PWMC) continuing social engagement. This study aimed to understand PWMC and family caregivers’ initial perspectives on the feasibility and utility of a wearable technology-based social memory aid. We recruited 20 dyads, presented the memory aid, and conducted semi-structured interviews from June to August 2020 over Zoom video conferencing. Interviews were transcribed and analyzed using thematic analysis. Overall, participants anticipated the technology could reduce socializing-related stress now and in the future for both members of the care dyad. However, certain features of the memory aid (e.g., visitors must have the app), could limit utility, and participants provided recommendations to enhance the tool. Our findings will inform future technology-enabled social memory aid development for PWMC and family caregivers.

Keywords: assistive technology, Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, social engagement, caregiving, qualitative

People living with Alzheimer’s Disease and Alzheimer’s Disease Related Dementias (AD/ADRD) or cognitive impairment can experience difficulties engaging socially due to forgetting names or faces of other individuals, which often results in isolation and loneliness. Memory aids to help persons with memory concerns (PWMC) remain socially engaged exist; however, none have been demonstrated to help PWMC recognize or recall names of social contacts. In this paper we examine the usefulness of a smartwatch-enabled memory aid to support the social interactions of PWMC. By understanding how this new technology is perceived by PWMC and their family caregivers, we can better design technological memory aids to support PWMC.

Introduction to Memory Concerns

Memory concerns are associated with changes in social roles, embarrassment, frustration, and anxiety (Frank et al., 2006; Parikh et al., 2016). After a diagnosis of AD/ADRD, people have fewer face-to-face and telephone-based social encounters (Hackett et al., 2019). Recalling names of social contacts becomes increasingly difficult as dementia progresses (Alzheimer’s Foundation of America, n.d.) and can result in social withdrawal (Parikh et al., 2016).

Caring for a family member with memory concerns can be challenging and stressful. Caregivers of persons with mild-to-moderate memory concerns are likely to experience lower levels of burden than caregivers of persons with severe AD/ADRD (Germain et al., 2009). Given the progressive and long-term nature of AD/ADRD, caregivers often provide an increasing amount of care over the course of several years. Providing supports such as assistive technologies (ATs) may improve the caregiving experience at different stages of AD/ADRD (Sriram et al., 2019).

Memory Aids and Technology Adoption

Strategies to help PWMC compensate for changes in memory include internal strategies (e.g., cognitive training) and external strategies (e.g., memory aids). Cognitive training can be effective with mild memory concerns, but memory aids, especially those that require passive engagement (Riikonen et al., 2013), are preferable as memory concerns progress (Chandler & Shandera-Ochsner, 2018). Non- or low-technological memory aids include prompting by another person, lists, labels, and notebooks (Wilson, 2013).

An increasing number of technology-enabled memory aids are available to support PWMC. Memory aids for social engagement for PWMC have included a mobile application to help with reminiscing (Hamel et al., 2016), and robots and software to help contact others (Moyle et al., 2019; Perilli et al., 2013). Nevertheless, in a recent literature review, the only technological memory aid to assist PWMC with recognition of social contacts was the Social Support Aid (SSA; Pappadà et al., 2021). This technology used facial recognition software on a body-worn camera to prompt PWMC with the name and relationship of a visitor on a smartwatch face. The pilot randomized control trial of the SSA found no evidence of improvements in social engagement or quality of life. Barriers to beneficial use of the system included system complexity, impracticality, unreliability, and stigma. Participants noted a desire for an improved tool to assist with remembering names (McCarron et al., 2019).

Besides the SSA, a few other studies have examined the use of smartwatches as memory aids to PWMC. One study tested multiple smartwatch applications, including one that provided scheduling notifications, and found smartwatches promising for people with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia. However, there were several barriers to effective use of the smartwatch including issues with charging, device pairing, and difficulty swiping on the smartwatch face (Thorpe et al., 2016). Nevertheless, a few case studies have provided evidence in support of smartwatch reminders for people with Korsakoff’s syndrome (Lloyd et al., 2019; Smits et al., 2022) and acquired brain injury (Jamieson et al., 2019). Thorpe et al. (2016) argued that smartwatches may be uniquely well-suited as assistive tools given that they are widely available, allow for personalization, may be less stigmatizing than traditional ATs, and may become increasingly familiar.

Technology adoption models and other adoption research can aid in our understanding of factors that may influence technological memory aid uptake. Two widely accepted technology adoption models include the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) (Venkatesh et al., 2003) and the Technology Acceptance Model 3 (TAM3; Venkatesh & Bala, 2008). Both frameworks were developed to understand adoption of technologies by employees. The Model for the Adoption of Technology by Older Adults (MATOA) builds off UTAUT to better predict technology adoption for older people with technologies such as mobile phones. MATOA combines UTAUT’s constructs of performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and social influence into the construct of use expectancy, and adds biophysical aging restrictions, anxiety, requisite knowledge, and intrinsic motivation (Hsiche Wang et al., 2017). For community-dwelling PWMC, social network support, ability-appropriate guidance (Riikonen et al., 2013), simple interfaces, and visual reminders (Kruse et al., 2020) greatly influence adoption.

Informed by previous research, researchers and engineers developed the Smartwatch Reminder (SR) system with the goal of providing an improved memory aid to assist PWMC with recognizing social contacts. The SSA utilized facial recognition technology, which was unreliable, included a cumbersome enrollment process, and required PWMC wear a camera (McCarron et al., 2019). Instead, the SR system provides notifications based on the proximity of a visitor’s smartphone to the physical location of the PWMC’s smartphone. The SR system was expected to be more reliable since robust technology exists in smartphones for accurate location determination. The enrollment process of the SR system was designed to be minimal. Lastly, the SR system only requires PWMC to wear a smartwatch, which may be less stigmatizing than a body-worn camera. Ultimately, researchers hoped PWMC and family caregivers would have greater use expectancy for the SR system. The purpose of the present study was to understand PWMCs’ and family caregivers’ initial perceptions of this novel, technology-enabled, social memory aid, to inform technology development for this population.

Methods

Design

We recruited 20 PWMC and their caregivers to collect data on their initial reactions to the SR system. Each dyad participated in a semi-structured interview conducted over Zoom video conferencing. Fifteen to thirty is a common range of interviews conducted to identify patterns in qualitative research (Braun & Clarke, 2013). We determined saturation was achieved with the 20 interviews. Including the perspectives of both PWMC and caregivers is important for AT development (Holthe et al., 2018), and dyadic interviewing allows for greater breadth than in individual interviews and greater depth than focus groups (Morgan et al., 2013). Demographic information was gathered during the interview. Dyads were shown a brief instructional video and presentation on the SR system and encouraged to ask questions about the technology. They were then asked a series of open-ended questions about usability, functionality, and possible enhancements to the SR system.

Recruitment

A voluntary response sampling method was employed to recruit participants. Researchers contacted family members of PWMC and health professionals who have agreed to learn about research opportunities through the University of Minnesota Caregiver Registry listserv. Emails were sent to all members to invite them to participate in the current study. Participants were also recruited through email advertisements in professional networks, and at memory clubs and adult day programs.

To be eligible to participate, PWMC had to speak English, have no history of a serious mental illness (i.e., any major psychiatric disorder), and have a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease or mild-to-moderate cognitive impairment by a physician. Eligible caregivers had to speak English, be 21 years of age and over, and self-identify as someone who aids the PWMC because of their memory concerns. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, interviews were conducted over Zoom video conferencing, and therefore the dyad was ineligible if neither member had access to a working web camera and microphone. Of 24 dyads recruited, 20 dyads were enrolled and participated in the interviews conducted by authors EA and AM. Reasons for refusing to enroll or not completing the interviews included concerns about PWMC distress or ability to consent, and due to illness. In one interview, a non-enrolled family member was present off-screen, and researchers excluded their comments for analysis. The study was approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board (STUDY00006318).

Technology Development Process

An iterative design and development process was used by the research team to develop the SR system. Findings from the SSA study, which included the perspectives of PWMC and their caregivers, heavily influenced the SR system design (McCarron et al., 2019). A specification was iteratively drafted, reviewed, and edited by the research team and supporting engineers that described the various features and major elements of the approach. Next, graphics artists and user interface specialists created the content screens and interfaces. These screens and interfaces went through a second iterative review and adjustment process until a final design was achieved. Software engineers then coded the system to complete the specified functionality.

The Social Memory Aid

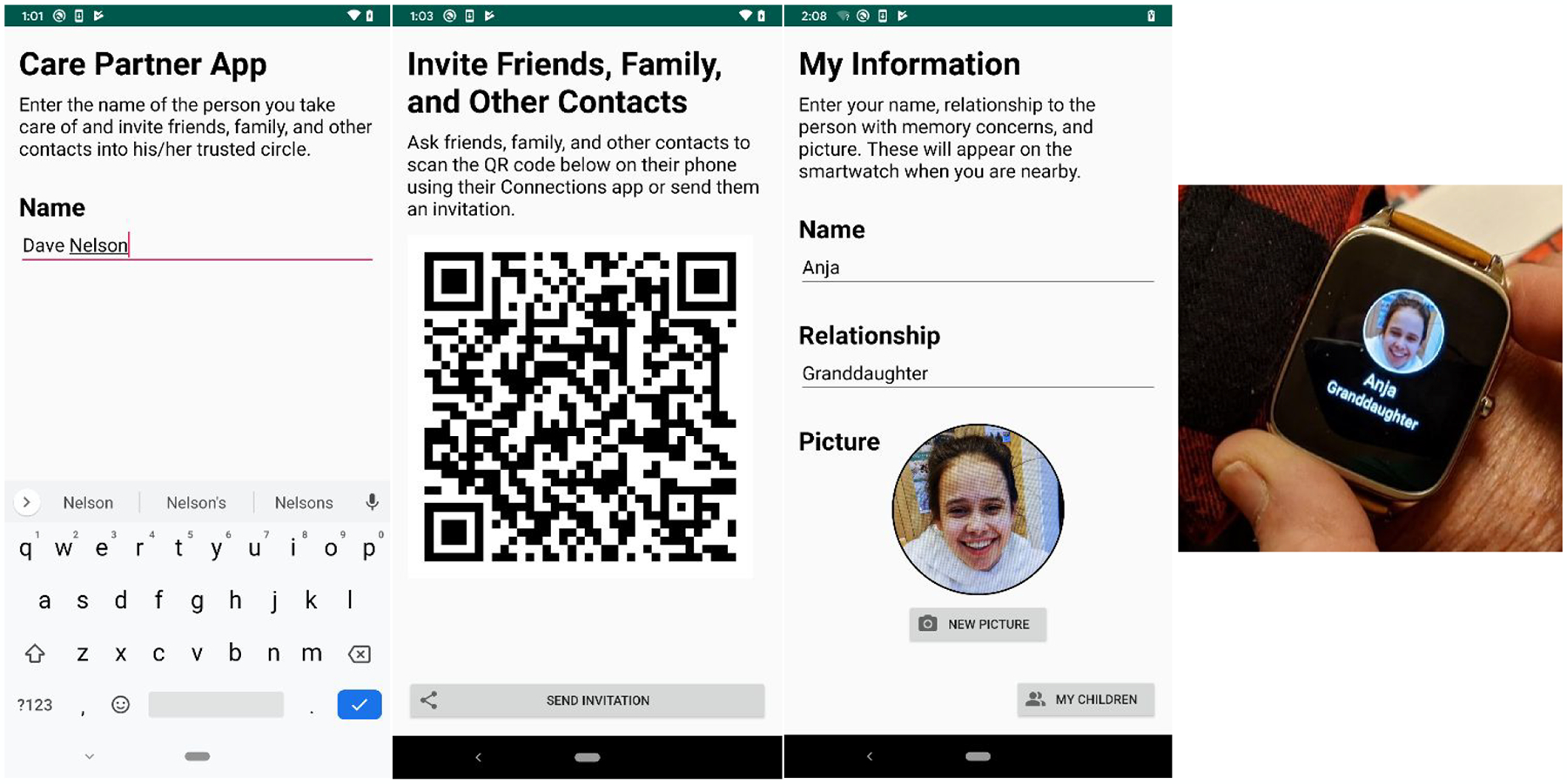

The informational slides and video demonstration described the SR system as a tool to assist with name recall for PWMC by providing a notification on a smartwatch face with information about a visitor. For set-up, the family caregiver downloads an app onto a smartphone connected by Bluetooth to a smartwatch (Figure 1). Next, social contacts scan a QR code or click on an email link to download a related app onto their smartphones. They then upload a photograph, and type in their name and their relationship to the PWMC (e.g., “Anja, Granddaughter”). When the visitor app comes within range of the caregiver app, the photograph, name, and relationship of the visitor appears on the smartwatch worn by the PWMC.

Figure 1.

Images of the Smartwatch Reminder System

Note. The first and second panel refer to the care partner app (the app on smartphone that will link to the smartwatch worn by the person with memory concerns). The third panel refers to the family and friends app. The fourth panel refers to the notification on the smartwatch.

Data Collection Procedures

Qualitative interviews were conducted between June and August 2020. Caregivers and PWMC provided verbal consent and/or assent before the interview began. PWMC’s capacity to consent was evaluated by administering the Mini-Cog and UCSD Brief Assessment of Capacity to Consent (UBACC; Borson et al., 2003; Jeste et al., 2007). The PWMC provided verbal consent if they had a Mini-Cog score of 3 or higher and a UBACC score of 14.5 or higher; otherwise they provided verbal assent. Once consent or assent was obtained, we administered a brief survey to caregivers and PWMC to determine age, sex, race, ethnicity, education, income, employment status, living arrangement, relationship to each other, and diagnosis of PWMC.

Interviews followed a semi-structured protocol (Appendix) focusing on which features seemed easy or difficult to use, and perceived barriers and facilitators to SR use (mean length=107 minutes). Interviews were audio recorded, and direct observation notes were completed within 24 hours of each interview to document impressions of the participants’ location, level of comfort with Zoom technology, notable nonverbal behaviors, and interactions between caregiver and PWMC.

Data Analysis

Audio recordings were professionally transcribed and compiled with direct observation notes, which were analyzed together using Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six steps of thematic analysis: 1) familiarization; 2) generation of initial codes; 3) search for themes; 4) review themes; 5) define and name themes; and 6) generate report of findings. An iterative process was followed to continually identify themes, linkages, and explanations, which were then compared to create a codebook. The initial codebook was developed by BH, and EA and JM reviewed to refine and clarify codes and themes. BH then independently hand-coded a subset of the interviews and revised the codebook after discussion with EA, JM, LM, EJ, JF, and AM. BH coded all 20 interview transcripts in NVivo 12, although saturation was achieved prior to 20, and EA and JM reviewed the coded material and revised as necessary. Developing codes and themes was an iterative process which ensured that saturation was achieved and that data were suitably categorized. The codebook included 26 codes which were reviewed to identify four themes with subthemes. Peer debriefing, negative case analysis, and clear audit trails enhanced transparency and rigor in the analysis (Marshall & Rossman, 2016).

Results

Sample Description

Most of the 20 dyads lived together (N=18) and were spouses (N=16). Caregivers were predominantly women (N=14) and PWMC were predominantly men (N=14). Participants most often characterized their memory concerns as relating to Alzheimer’s Disease (N=10), followed by mild cognitive impairment (N=6). All participants were community-dwelling. Our sample was predominately white (95%) and 52.5% had a Bachelor’s degree or higher. More demographic details are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample Demographics

| Variable | Entire Sample | PWMC | Caregivers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (in years) | |||

| Mean (range) | 72.23 (37–88) | 74.75 (57–88) | 69.70 (37–86) |

| Race/ethnicity (%) a | |||

| White | 38 (95%) | 19 (95%) | 19 (95%) |

| Black/African American | 2 (5%) | 1 (5%) | 1 (5%) |

| Hispanic | 1 (2.5%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (5%) |

| Gender (%) | |||

| Female | 20 (50%) | 6 (30%) | 14 (70%) |

| Male | 20 (50%) | 14 (70%) | 6 (30%) |

| Employment Status (%) | |||

| Employed | 4 (20%) | - b | 4 (20%) |

| Retired | 15 (75%) | - | 15 (75%) |

| Homemaker | 1 (5%) | - | 1 (5%) |

| Education (%) | |||

| High school degree | 5 (12.5%) | 4 (20%) | 1 (5%) |

| Some college or Associate’s degree | 14 (35%) | 5 (25%) | 9 (45%) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 6 (15%) | 3 (15%) | 3 (15%) |

| > Bachelor’s degree | 15 (37.5%) | 8 (40%) | 7 (35%) |

| Income (%) | |||

| $24,999 and below | 4 (10%) | 2 (10%) | 2 (10%) |

| $25,000–39,999 | 2 (5%) | 2 (10%) | 0 (0%) |

| $40,000–59,999 | 3 (7.5%) | 2 (10%) | 1 (5%) |

| $60,000–79,999 | 8 (20%) | 4 (20%) | 4 (20%) |

| $80,000 and above | 18 (45%) | 8 (40%) | 10 (50%) |

| Missing | 5 (12.5%) | 2 (10%) | 3 (15%) |

Note. PWMC= Persons with Memory Concerns

Participants could select multiple races; therefore, percentages add to more than 100%.

Employment status was only requested for caregivers.

Themes

Results indicated that overall, the SR system was viewed favorably to support social engagement now and in the future, and could reduce interaction-related stresses for both PWMC and family caregivers. However, dyads reported significant challenges with features of the technology and provided recommendations to improve usability. Here, we report the four primary themes, as well as sub-themes that illustrate PWMC and caregivers’ perceptions of the technology (see Table 2). All names have been replaced with pseudonyms.

Table 2.

Description of Major Themes with Subthemes

| Theme | Description | Subthemes |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived Usefulness of the Memory Aid Over Time | This theme explores the anticipated value of the social memory aid at present and in the future. |

|

| Alleviating Socializing-Related Stress | This theme details the anticipated benefit of the SR system in reducing stress stemming from social encounters for both PWMC and their caregivers. |

|

| Features Restricting Utility and Ease of Use | This theme examines limitations of the memory aid prompt that impact usability. |

|

| User Recommendations to Enhance Functionality | This theme includes users’ perspectives on features that could be added or adapted to enhance both engagement and perceived benefit from the SR system. |

|

Note. PWMC= Persons with Memory Concerns

Perceived Usefulness of the Memory Aid Over Time

Results indicated that the SR system could serve to enhance social engagement for PWMC in unique ways at different times. The relationship of when, where, how, and with whom the system could be useful is explored within the subthemes Immediate Use and Future Use.

Immediate Use.

PWMC and caregivers reported that continued social engagement was a high priority and felt that activation of the SR system now, before memory concerns progressed, could facilitate continued engagement with existing support networks. A few participants indicated that habituating PWMC to the system early on could allow for quick, seamless adoption of the technology and sustained use in the future as dementia progresses. April (F, 62 years, caregiver) said of her spouse, “if he’s already learned [the SR system] while he has that ability to learn that and train on that…he may be able to rely upon it more when his cognition declines to that point where it’s always hard to remember a name.” A few hoped the notifications could improve memory, like Lee (M, 77 years, PWMC), “having the name and a picture come up multiple times may kind of reinforce it in your memory.” This suggests that perceptions of enduring benefits can motivate use of memory aids in earlier stages of memory concerns.

Many participants identified ways the SR system could assist them with social engagement at present. Several participants envisioned utilizing the system with religious communities, special events with extended family, vocational and leisure activities, and support groups. Ivy (F, 74 years, PWMC), considered using the system in community celebrations: “our town is full of festivals in the summer and that’s where I would see a lot of people…those people, I would ask them to put in [to the SR system].” Barb (F, 86 years, caregiver) discussed her spouse using the system with neighbors: “he can remember who used to live here 40 years ago, but now we have new people, and sometimes they come over…therefore, [the SR system] would be helpful right now.” AT to facilitate social engagement with peripheral contacts may be desirable for people with mild to moderate memory concerns.

Future Use.

Many participants discussed the system having greatest utility in the future, when memory declined further, to use with their family caregiver, grandchildren, and other family and friends. Variations on the phrases “down the road,” “there will come a time”, and “in the future” appeared throughout the data from both caregivers and PWMC. Rick (M, 73 years, caregiver) said, “we’d be very interested [in the SR system]. Layla’s not at the point yet where family members or very close friends she doesn’t recognize, but we know this is a progressive thing.”

Additionally, a few caregivers described potential benefits of the system in the future with hired paid caregivers or if the PWMC moved into a long-term care facility. Rose (F, 83 years, caregiver) did not think the system would be useful now, but later on she could “see this working really well in a nursing home or assisted living, where the people live alone and don’t remember their family or friends that visit.” This points to the relationship between level of cognitive decline and memory aid value.

Alleviating Socializing-Related Stress

Participants thought the SR system could improve well-being by reducing socializing-related stress for both members of the care dyad.

PWMC Stress Relief.

Participants reported that forgetting names negatively impacts PWMC causing them to feel embarrassment, frustration, and guilt. An anticipated benefit of the SR system was reducing social anxiety for PWMC during social encounters. Trying to remember a name can distract PWMC from the conversation, and the SR system could allow them to be more present, as Layla (F, 72 years, PWMC) indicated,

There are times…that I will look at somebody and know them, and not remember their names. I don’t like that very well [sic]. So I am sure [the SR system would] free me up to not be so concerned about that. And be able to just go into the conversations.

Participants also reported that the system could reduce stress in anticipation of social encounters. Hazel (F, 75 years, caregiver) said the SR system, “would relieve Declan’s mind some… if he knew that he was going to put names and faces together.” After Tristan (M, 71 years, PWMC), explained how the system would benefit him, his wife Jamila (F, 70 years, caregiver) concurred and added that the system “would make the whole idea of going out socially more palatable.” Another way multiple participants found the system could assist before the social encounter is by warning PWMC that a visitor is nearby, such as at the front door. Lily (F, 64 years, caregiver) thought this would benefit her spouse:

If he’s got questions… he could ask before they actually appear…I know it’s not a long time that the notification is, but just having that notification ahead of time might help his anxiety a little bit on who’s coming.

Therefore, the notification timing may influence system benefits.

Caregiver Stress Relief.

Caregivers stated they may also reap the benefits through PWMC’s reduced stress and increased independence. Many caregivers mentioned the connection between their loved ones’ well-being and their own, such as Jamila (F, 70 years, caregiver), “I…personally would be happier, because Tristan would be feeling more comfortable and he’d be more confident.”

More than a quarter of caregivers in our study indicated that the SR system could provide caregivers respite as well. When unable to remember a name, PWMC often relied on family caregivers to prompt their memory. Caregivers reported that PWMC, with the support of the SR system, could take over the responsibility of name-knowing from them. Lisa (F, 77 years, caregiver) said of the SR system, “I wouldn’t have to feel like I have to jump in all the time which must be frustrating for me or for him…It makes me feel like [his] mother.” The mental load of trying to remember names is an added burden for caregivers, as Peggie (F, 60 years, caregiver) noted that without access to the memory aid, “then I have to remember all the names, right?”

Features Restricting Utility and Ease of Use

The system was developed with simplicity in mind. Overall participants had minimal technical concerns about downloading the app, sharing the app invitation with others, and receiving notifications. Although a few participants worried about learning a new technology, or had vision and dexterity concerns, results indicated that the system was mostly thought to be easy to use. However, the simplicity of the system limited functionality for many participants. Commonly noted system limitations comprise our subthemes: Visitors Must Have the App and Memory Prompt Only During Social Encounters.

Visitors Must Have the App.

For the system to function, visitors must download the SR system app onto their smartphone and create a profile, which limited system utility. Ideally, participants wanted the SR system to facilitate socializing with an extensive social network. Most participants were unconcerned about inviting close family, friends, paid caregivers, and even specific communities (e.g., religious, dementia-related groups) to the app. However, participants also desired reminders about infrequent contacts and acquaintances, yet multiple care dyads described feeling uncomfortable inviting them to the app. Some were hesitant to disclose dementia diagnosis as Annmarie (F, 73 years, caregiver) noted,

If someone did not know that this person has dementia you might feel a little uncomfortable… asking them to get the app and put it on their phone, so that he can recognize it. Because some people don’t like to share the fact that you have dementia.

Lee (M, 77 years, PWMC) expressed a similar sentiment and worried about burdening people in his senior living community with the app, “I would feel a little bit, I don’t know, embarrassed or just…a little bit uncomfortable asking them to put an app on their phone for me.” Others expected that acquaintances would be unwilling to download the app. April (F, 62 years, caregiver) thought it awkward to ask acquaintances, and her spouse Lief (M, 69 years, PWMC) added “they’re not going [to] do the app.”

A couple participants worried about contacts who do not own smartphones or are less familiar with technology. In regard to the app, Serena (F, 73 years, caregiver) said, “I’m hesitant… to put them in an imposition and then to also embarrass them because they’re going to have to say ‘I don’t know how to do it.’” Being required to download an app presents a barrier for contacts with low technology literacy skills or contacts without a smartphone.

Memory Prompt Only During Social Encounters.

Participants desired the ability to prepare for social encounters by reviewing information about visitors further in advance. Multiple caregivers discussed increased anxiety for the PWMC in anticipation of social encounters. Peggie (F, 60 years, caregiver) desired a way to “pull information…for instance, we knew some people were coming over, and Brent was asking, ‘What are their names?’ So we could say, ‘Here’s the two people,’ and show him from the app.” Participants also found the system limiting in that they cannot review information about visitors for remote interactions. Another caregiver, Barb (F, 86 years), had hoped to use the system to help her spouse recall a penpal:

He’ll say, ‘Oh, I can’t remember who that person is.’ And I’ll try and be describing [sic] them, but-- you know, ‘She’s got white hair,’ and there are 10 people that are volunteering [that] have white hair. But if he were able to find that picture, it would help.

A couple participants noted they wanted assistance remembering names when speaking with someone else. For example, April (F, 62 years, caregiver) described an incident where her spouse, Lief, felt guilty because he forgot April’s name while talking to a friend. April said, “it may frustrate Lief to not have [the SR system] do more than what it’s designed to do at this time.” The system may be limited by the heavy reliance on the notification for name recall.

User Recommendations to Enhance Functionality

The most salient recommendations to enhance usability constitute our subthemes: Social Network Directory, Combine Caregiving Technologies, and Notification Settings.

Social Network Directory.

A common desire was to add a directory of social contacts that allows for manual input and retrieval of information. Annmarie (F, 73 years, caregiver) said “it would be nice if they develop this app if there’s any way that the user could put in a picture and a descriptor… [Charles] probably doesn’t want to…have his doctor have to download the app.” The directory could include a grouping component as recommended by two caregivers, including Peggie (F, 60 years, caregiver), who suggested that the user could “create groups…a scenario is, Brent knows he’s going on his support call, and he’s like, ‘Well, who’s on the call?’… I could say, ‘Here’s the six people that usually are on that call.’” A directory could further reduce social stress for PWMC and allow for use of the system with a more expansive network.

Combine Caregiving Technologies.

Another common recommendation was to combine the SR system with other tools for PWMC and their caregivers such as GPS tracking or a medical alert system. Combining apps could reduce technology burden, as Rick (M, 73 years, caregiver) noted “so that you don’t have 50,000 apps instead of just a couple.” Some caregivers desired a more complex app to meet a multitude of needs unrelated to name recall.

Notification Settings.

Participants provided suggestions on how the notifications would best support PWMC. As many social interactions are not one-on-one, creating an effective system for multiple notifications is essential. Some recommended a scrolling feature, explained by Doug (M, 74 years, caregiver), “I would suggest [the notification screen] does a slow scroll [of notifications]. Second to that, there would be the little dots on the bottom indicating there’s [sic] other pages that you could swipe to.” His wife, Ivy (F, 74 years, PWMC), disagreed and preferred the smartwatch face show “as many [notifications] as it could handle” at one time.

A couple participants thought a one-time notification may not be enough to help PWMC with names during a conversation. If the notification stayed on the smartwatch face until it was swiped away, the SR system could assist with name recall throughout the encounter, which Annmarie (F, 73 years, caregiver) said would be “critical.” April (F, 62 years, caregiver) found this beneficial as well, saying her spouse “could keep looking at [the notification] to remind him.”

Discussion

AT devices have the potential to improve quality of life for PWMC and family caregivers. This study used qualitative interviews to understand initial user perceptions of a novel, smartwatch-enabled memory aid to inform technology research and development for this population. Results indicated that participants felt that the SR system had the potential to reduce stress associated with memory loss both now and in the future and could reduce reliance on the caregiver for name recall. Nevertheless, pared-down features of the system also risked undermining the utility of the SR system. Results have both theoretical and practical implications that are discussed in more detail, below.

The findings indicate that the SR system may be an improvement from the SSA, but barriers to beneficial use remain. Both studies confirmed that AT to help with remembering names is desirable for PWMC and caregivers. Unlike the SSA, participants in the present study largely did not think the technology was complicated and expressed optimism that it could reduce stress. Although the enrollment process wasn’t thought to be difficult, the necessity of enrolling visitors and of an ever-present application on visitors’ smartphones, were potentially stigmatizing and impractical. Some participants were wary about asking acquaintances to enroll, similar to the SSA (McCarron et al., 2019). Barriers identified only in the present study include the concern that visitors would not own the technology or have the technology skills necessary to participate, and that reminders only occur during social encounters.

Smartwatches may be an effective medium for aiding PWMC, but more research is needed. Most participants were not largely concerned about specific, practical issues with utilizing a smartwatch (Thorpe et al., 2016). The increasing dissemination of mobile devices was apparent as most participants used smartphones and multiple were regular users of smartwatches.

Technology adoption models may not adequately capture adoption considerations for PWMC and their caregivers, nor for ATs in general. Use expectancy and biophysical aging restrictions, which are key predictors of adoption in MATOA, only consider expected use and restrictions at present (Hsiche Wang et al., 2017). UTAUT and TAM3 discuss how ease of use and anxiety may change over time but not perceived usefulness (Venkatesh et al., 2003; Venkatesh & Bala, 2008). Our findings indicate care dyads distinguish between beneficial use at present and in the future when memory concerns progress, and value when technology can be used at various time points. Technology adoption models for PWMC should consider expected length of beneficial use, in relation to changes in cognitive abilities, as an essential component of use expectancy. Biophysical aging restrictions within the MATOA model should more clearly incorporate dynamic changes in abilities over time. Finally, social influences for AT adoption should include the strength of the social ties that will be required for the technology to function. AT that requires commitments from weak social ties may negatively influence use expectancy.

AT to promote social engagement should be equipped to meet changing needs of PWMC over time. AT developers should create technologies that are simple to use, but with optional, more complex features that can be turned on per personal preferences and abilities of the care dyad. Alternatively, reliable technologies can be developed that can intelligently adapt to the users’ abilities. Developers of social memory aids for PWMC in earlier stages should avoid technologies that require participation from weak social ties and should ensure functionality in group settings.

Limitations and Future Directions

Participants, especially caregivers, appeared to have high technology literacy. Because of our sample demographics and requirement that participants had video-conferencing capabilities, our findings may transfer best to community-dwelling, highly educated, and technology-literate care dyads, or to upcoming generations who are increasingly more technology-literate (AARP, 2016), since familiar tools can ease memory aid adoption (Chandler & Shandera-Ochsner, 2018). Finally, we were unable to provide the technology for demonstration and testing in-person due to the pandemic, which is a major limitation.

Future research should include user-testing in a feasibility trial of the SR system to understand how initial perceptions of a technology-enabled social memory aid translate into actual use and impacts. It should allow for comparisons of utility of the technology based on diagnosis, level of memory concerns, and technology literacy levels. Long-term longitudinal designs for AT research would reveal whether and how usefulness changes over time, as participants suggested for the SR system. Developers should consider creating a social network directory for PWMC, as requested. Finally, developers should continue to search for ways to deliver social reminder technologies, as participants noted important limitations for the Social Support Aid and the SR system.

Conclusion

Our findings provide insight into the perspectives of PWMC and family caregivers on the expected benefits and limitations of a technology-enabled social memory aid, and how the timeline for use influences expectations. These findings add to our understanding of technology adoption and can inform AT development for this population.

What this Paper Adds

Timeline for expected use is an important consideration for assistive technology users

Applications of Study Findings

Assistive technologies for people with a progressive illness should provide benefits throughout various stages of the disease

Researchers to continue innovating socially assistive technologies

Acknowledgements

The Authors would like to thank Joseph E. Gaugler at the University of Minnesota, Gary Havey at Advanced Medical Electronics, and our participants for making this research possible.

Funders

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging [grant number R44AG063683].

Appendix

Semi-Structured Interview Questions

Now that you’ve seen the Smartwatch System, let’s discuss it. What about the system seemed easy to use? What seemed difficult? How could the system be improved?

- Do you think that the Smartwatch System could work well for you in your everyday lives? Why or why not? Please think about this as a pre- or post-COVID-19 world, where you may be more mobile and you may be visited more often by other people.

- Probe for responses specific to both people in each dyad: the care partner and relative with memory concerns.

- Potential topics to discuss and prompts to consider:

- Ability to interact with other people (e.g., family, friends, community, healthcare providers)?

- Any impact on your way of providing care?

- Level of confidence (e.g., in providing care, navigating social situations)?

Do you think that technology such as the Smartwatch System could affect how you are able to get out and engage with other people in your community (e.g., visiting friends and family, participating in clubs, attending events at a senior center or church)? Please explain.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

IRB protocol/human subjects approval number

University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board (STUDY00006318).

References

- AARP. (2016). Caregivers & technology: What they want and need. AARP Research. 10.26419/res.00191.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Foundation of America. (n.d.). About Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. Retrieved April 9, 2021, from https://alzfdn.org/caregiving-resources/about-alzheimers-disease-and-dementia/

- Anderson M, & Perrin A (2017). Tech adoption climbs among older Americans. Pew Research. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2017/05/17/tech-adoption-climbs-among-older-adults/ [Google Scholar]

- Borson S, Scanlan JM, Chen P, & Ganguli M (2003). The Mini-Cog as a screen for dementia: Validation in a population-based sample. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 51(10), 1451–1454. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, & Clarke V (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Psychology, 3, 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, & Clarke V (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler MJ, & Shandera-Ochsner AL (2018). Memory compensation in mild cognitive impairment and dementia. In APA handbook of dementia (pp. 455–469). Washington: American Psychological Association. http://psycnet.apa.org/fulltext/2018-19589-024.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Frank L, Lloyd A, & Flynn JA (2006). Impact of cognitive impairment on mild dementia patients and mild cognitive impairment patients and their informants. International Psychogeriatrics, 18(1), 151–162. 10.1017/S1041610205002450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain S, Adam S, Olivier C, Cash H, Ousset PJ, Andrieu S, & Salmon E (2009). Does cognitive impairment influence burden in caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease? Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 17(1), 105–114. 10.3233/JAD-2009-1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackett RA, Steptoe A, Cadar D, & Fancourt D (2019). Social engagement before and after dementia diagnosis in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. PLOS ONE, 14(8). 10.1371/journal.pone.0220195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamel AV, Sims TL, Klassen D, Havey T, & Gaugler JE (2016). Memory Matters. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 42(7), 15–24. 10.3928/00989134-20160201-04 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holthe T, Halvorsrud L, Karterud D, Hoel K-A, & Lund A (2018). Usability and acceptability of technology for community-dwelling older adults with mild cognitive impairment and dementia: A systematic literature review. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 13, 863–886. 10.2147/CIA.S154717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiche Wang K, Chen G, & Chen H-G. (2017). A model of technology adoption by older adults. Social Behavior & Personality: An International Journal, 45(4), 563–572. [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson M, Monastra M, Gillies G, Manolov R, Cullen B, McGee-Lennon M, Brewster S, & Evans J (2019). The use of a smartwatch as a prompting device for people with acquired brain injury: A single case experimental design study. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 29(4), 513–533. 10.1080/09602011.2017.1310658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeste DV, Palmer BW, Appelbaum PS, Golshan S, Glorioso D, Dunn LB, Kim K, Meeks T, & Kraemer HC (2007). A new brief instrument for assessing decisional capacity for clinical research. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 64(8), 966–974. 10.1001/archpsyc.64.8.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse CS, Fohn J, Umunnakwe G, Patel K, & Patel S (2020). Evaluating the facilitators, barriers, and medical outcomes commensurate with the use of assistive technology to support people with dementia: A systematic review literature. Healthcare, 8(3), 278. 10.3390/healthcare8030278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd B, Oudman E, Altgassen M, & Postma A (2019). Smartwatch aids time-based prospective memory in Korsakoff syndrome: A case study. Neurocase, 25(1–2), 21–25. 10.1080/13554794.2019.1602145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall C, & Rossman G (2016). Designing qualitative research (6th ed.). SAGE, Thousand Oaks. ISBN:1452271003. [Google Scholar]

- McCarron HR, Zmora R, & Gaugler JE (2019). A web-based mobile app with a smartwatch to support social engagement in persons with memory loss: Pilot randomized controlled trial. JMIR Aging, 2(1). 10.2196/13378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan DL, Ataie J, Carder P, & Hoffman K (2013). Introducing dyadic interviews as a method for collecting qualitative data. Qualitative Health Research, 23(9), 1276–1284. 10.1177/1049732313501889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyle W, Jones C, Dwan T, Ownsworth T, & Sung B (2019). Using telepresence for social connection: Views of older people with dementia, families, and health professionals from a mixed methods pilot study. Aging & Mental Health, 23(12), 1643–1650. 10.1080/13607863.2018.1509297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappadà A, Chattat R, Chirico I, Valente M, & Ottoboni G (2021). Assistive technologies in dementia care: An updated analysis of the literature. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 644587. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.644587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh PK, Troyer AK, Maione AM, & Murphy KJ (2016). The impact of memory change on daily life in normal aging and mild cognitive impairment. The Gerontologist, 56(5), 877–885. 10.1093/geront/gnv030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perilli V, Lancioni GE, Laporta D, Paparella A, Caffò AO, Singh NN, O’Reilly MF, Sigafoos J, & Oliva D (2013). A computer-aided telephone system to enable five persons with Alzheimer’s disease to make phone calls independently. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 34(6), 1991–1997. 10.1016/j.ridd.2013.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riikonen M, Paavilainen E, & Salo H (2013). Factors supporting the use of technology in daily life of home-living people with dementia. Technology & Disability, 25(4), 233–243. 10.3233/TAD-130393 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smits S, Oudman E, Altgassen M, & Postma A (2022). Smartwatch reminders are as effective as verbal reminders in patients with Korsakoff’s syndrome: Three case studies. Neurocase, 28(1), 48–62. 10.1080/13554794.2021.2024237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sriram V, Jenkinson C, & Peters M (2019). Informal carers’ experience of assistive technology use in dementia care at home: A systematic review. BMC Geriatrics, 19, 160. 10.1186/s12877-019-1169-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe JR, Rønn-Andersen KVH, Bień P, Özkil AG, Forchhammer BH, & Maier AM (2016). Pervasive assistive technology for people with dementia: A UCD case. Healthcare Technology Letters, 3(4), 297–302. 10.1049/htl.2016.0057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh V, & Bala H (2008). Technology Acceptance Model 3 and a Research Agenda on Interventions. Decision Sciences, 39(2), 273–315. 10.1111/j.1540-5915.2008.00192.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh V, Morris MG, Davis GB, & Davis FD (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425–478. 10.2307/30036540 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson BA (2013). Chapter 30: Memory deficits. In Barnes MP & Good DC (Eds.), Handbook of Clinical Neurology (Vol. 110, pp. 357–363). Elsevier. 10.1016/B978-0-444-52901-5.00030-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]