Abstract

Directed differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) into functional ureteric and collecting duct epithelia is essential to kidney regenerative medicine. We describe highly efficient, serum-free differentiation of hPSCs into ureteric bud (UB) organoids and functional collecting duct cells. The hPSCs are first induced into pronephric progenitor cells at 90% efficiency and then aggregated into spheres with a molecular signature similar to the nephric duct. In a three-dimensional matrix, the spheres form UB organoids that exhibit branching morphogenesis similar to the fetal UB and correct distal tip localization of RET expression. Organoid-derived cells incorporate into the UB tips of the progenitor niche in chimeric fetal kidney explant culture. At later stages, the UB organoids differentiate into collecting duct (CD) organoids, which contain >95% CD cell types as estimated by scRNA-seq. The CD epithelia demonstrate renal electrophysiologic functions, with ENaC-mediated vectorial sodium transport by principal cells and V-type ATPase proton pump activity by FOXI1-induced intercalated cells.

Keywords: ureteric bud, anterior intermediate mesoderm, kidney bioengineering, kidney development, tissue engineering, nephric duct, collecting duct, principal cell, intercalated cell, FOXl1

Editorial summary:

Kidney collecting duct cells with physiologic functions are generated from human pluripotent cells.

Introduction

The directed differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) into organoids has been enabled by application of developmental knowledge and 3D growth environments1, 2. The derivation of kidney tissue poses particular challenges in that the organ exhibits sophisticated architecture and comprises two embryologically distinct progenitor tissues. The ureteric bud (UB) and metanephric mesenchyme arise from anterior and posterior mesodermal populations, respectively, which combine in the posterior region of the embryo to form the kidney. Normal organogenesis hinges on the hallmark branching morphogenesis of the UB, which drives the growth and radial organization of the developing fetal kidney. The resulting epithelium forms the urinary collecting system, including both the ureter and the collecting ducts (CDs) of the kidney, which play essential roles in water, electrolyte, and acid-base homeostasis. The metanephric mesenchyme, on the other hand, is successively induced by UB-derived signals into epithelialized nephrons3. Early successes in hPSC-based kidney differentiation focused on metanephric-like tissues, generating kidney organoids that contain multiple nephron components including glomeruli, proximal tubules, and distal tubules4, 5. However, these organoids lacked fundamental features of renal development, such as branching morphogenesis and maintenance of a progenitor niche, most likely because they lacked UB structures and the important RET+ tip domains. Given the essential roles of the UB in development and in kidney tissue engineering, the field requires efficient methods for differentiating hPSCs into UB organoids.

The differentiation of UB organoids was initially demonstrated using mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs); when these organoids were combined with induced metanephric progenitors, the resulting tissues formed branching structures with a high degree of similarity to the developing mouse kidney6. Similar results have not been reproduced using human cells. Recent protocols for differentiation of hPSCs to UB tissue have several technical and functional limitations. The early differentiation steps are inefficient, requiring the use of either cell sorting6–8 or mechanical dissection9 to enrich for appropriate progenitor cell populations. While UB progenitor cells could be expanded in 3D tissues, they did not reproduce either the morphological8–10 or temporal characteristics6, 7 of the iterative UB branching observed in vivo, often rather forming a folded epithelial structure8–10. One approach achieved a stalk morphology with a terminal branching event, but the growth and branching occurred over several weeks of 3D culture6, 7, compared with the normal UB that branches multiples times over several days. Moreover, to our knowledge robust in vivo-like functional quantitative characterization has not been described for hPSC-derived UB lineage cells, and only rarely for any hPSC-derived renal cell type. No hPSC-derived kidney cell types have been convincingly shown to recapitulate authentic regulated kidney physiologic functions. In the CD epithelium, the two major functional cell types are principal cells (PCs) and intercalated cells (ICs). The former regulate sodium, potassium, and water homeostasis, and the latter maintain acid-base equilibrium. Although immortalized cell lines derived from the mouse kidney displayed PC-like behaviors11, such as sodium reabsorption, similarly immortalized primary human cell lines do not12. Primary ICs from rodent models do not maintain a stable phenotype in cell culture13 so there has been no accessible model for in vitro IC function.

Here we present a robust method for the stepwise derivation of three-dimensional UB organoids and CD tissue from hPSCs. The method was optimized to ensure at least 90% efficiency at the mesendodermal and pronephric intermediate mesoderm (IM) stages, and these progenitor cells then form nephric duct spheroids that develop into branching UB organoids. We demonstrate that the tissues resemble their in vivo analogs at each stage of ureteric development via molecular analysis, and they exhibit authentic morphological behavior and responses to developmental stimuli. Their morphogenetic program is similar to the pattern observed in isolated UBs grown ex vivo14, with three-dimensional branching and organized tip-stalk polarity, and the cells can integrate into the nephrogenic niche in chimeric fetal kidney explants. Moreover, the UB organoids efficiently differentiate into CD cell types as characterized by scRNA-seq. From these organoids, we derive a 2D PC line that forms a high-resistance epithelium capable of robust sodium transport and a physiologic response to hormone signaling, a functional status not previously achieved in hPSC-derived kidney cells or in cultured primary human CD cells. We also induce the IC fate via expression of FOXI1 to facilitate the study of IC electrophysiology and proton transport. Collectively, these methods enable the modeling of a diverse spectrum of development, physiology, and pathophysiology of the human UB and CD.

Results

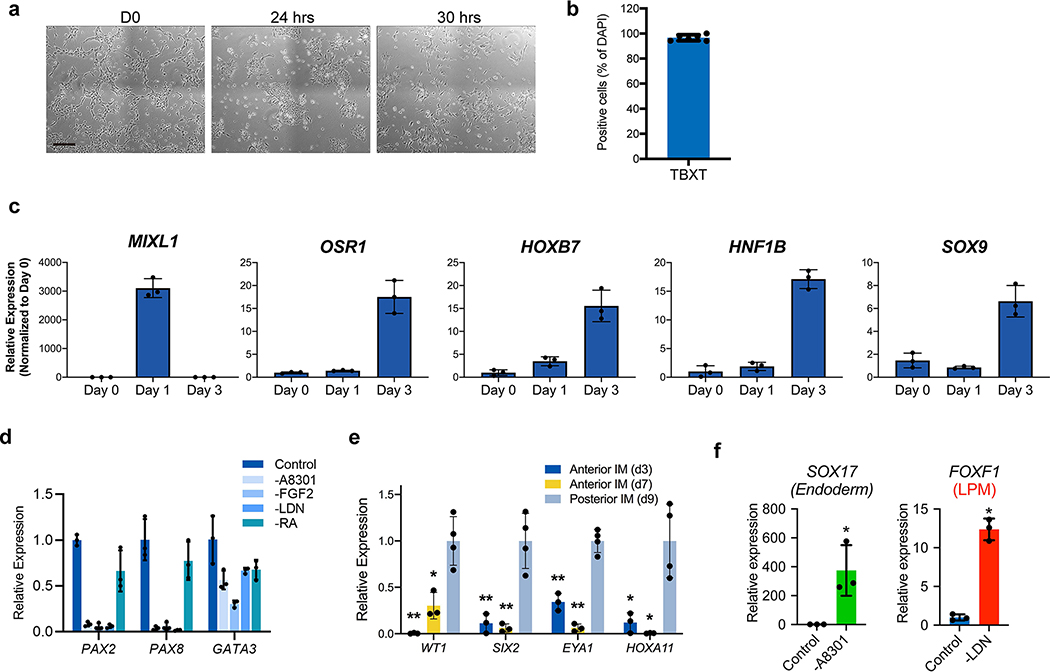

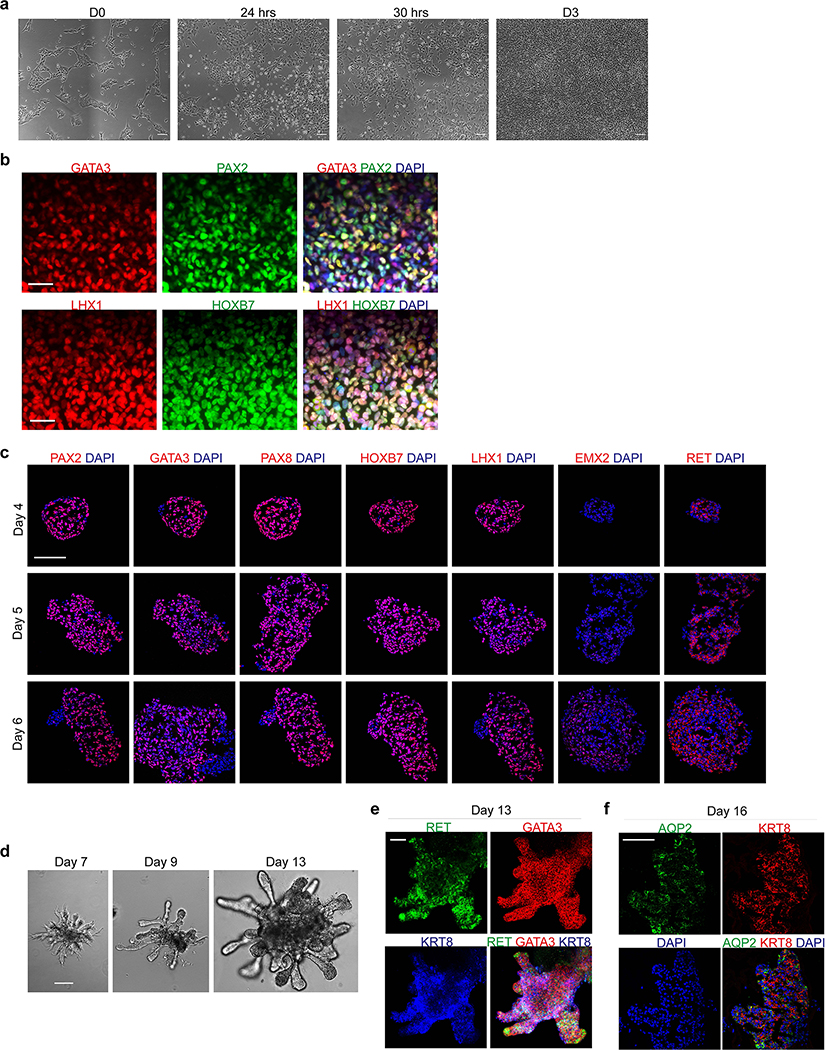

Induction of pronephric mesoderm and ND spheroids

To establish a robust protocol for generation of UB structures (summarized in Fig. 1a), we first sought to define conditions to efficiently differentiate hPSCs into pronephric IM. To facilitate these studies, we used CRISPR-Cas9 to introduce an in-frame mScarlet fluorescent reporter allele at the GATA3 locus (Extended Data Fig. 1), a transcription factor expressed persistently from the earliest stages of pronephric development and maintained throughout the CD epithelium15. Since the pronephric IM derives from early-stage primitive streak16, we first used a combination gastrula-stage signaling factors, including WNT (with the GSK3β inhibitor CHIR99021), FGF2, BMP4, and TGFβ (Activin A) as previously described to induce mesodermal fates from hPSCs17. This led to the rapid formation of TBXT+ mesendodermal progenitor cells with 96.6 ± 2.1% efficiency (Fig. 1b and Extended Data Fig. 2b) following a 30-hour exposure (Extended Data Fig. 2a), with an abrupt decrease in expression of pluripotency genes such as NANOG (Fig. 1c).

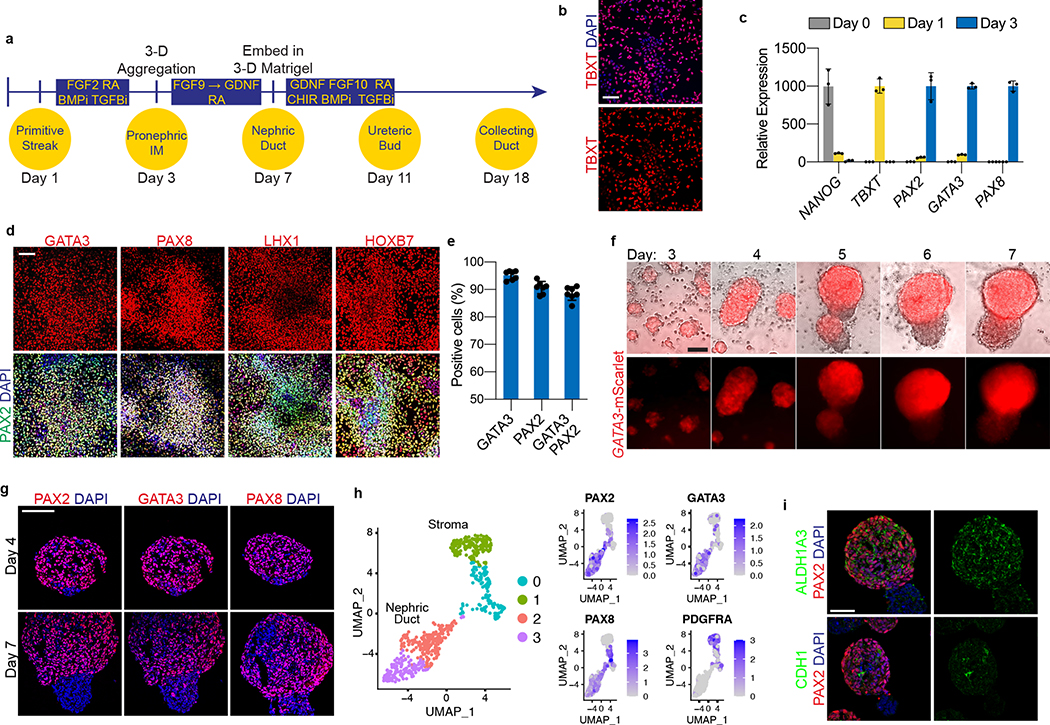

Figure 1. Directed differentiation of hPSCs into pronephric IM and nephric duct spheres.

a, Schematized diagram of stepwise differentiation strategy for generation of ureteric bud and collecting duct organoids. b, Immunofluorescent (IF) staining of monolayer cultures at day 1 revealed efficient induction of TBXT-expressing mesendodermal progenitor cells. c, Gene expression analyses by qPCR revealed dynamic down- and up-regulation of pluripotency (NANOG) and primitive streak (TBXT) markers, respectively, after one day of induction. Following two subsequent days of exposure to IM-inducing factors, TBXT was repressed and there was robust activation of PAX2, PAX8, and GATA3. n=3 independent biological replicates per timepoint. d, IF staining of day 3 monolayer cultures demonstrated a high proportion of cells with co-expression of pronephric IM genes PAX2, PAX8, GATA3, LHX1, and HOXB7. e, Quantification of staining for GATA3 and PAX2 represented on histogram revealed a high efficiency of differentiation into pronephric IM fate. n=7 quantified fields from 3 independent biological replicates. f, Following aggregation of IM cells at day 3, the resulting structures underwent stereotypic morphogenetic events characterized in the timecourse of stereomicrographs and fluorescent imaging using GATA3-mScarlet reporter. By day 7, the GATA3+ cells arranged into a dense sphere that excluded a minority population of negative cells. g, IF staining of sections of nephric duct spheres at days 4 and 7 demonstrated maintenance of expression of PAX2, PAX8, and GATA3. h, UMAP representing scRNA-seq of cells isolated from spheres at day 7, which demonstrated the presence of both nephric duct (clusters 2 and 3) and stromal (clusters 0 and 1; PDGFRA+) lineages. i, The majority of cells at day 7 expressed the nephric duct leader fate marker ALDH1A3 with low levels of the mature epithelial marker CDH1. Scale bars 100 μm (b and d), 50 μm (f, g and i). Column and error bars represent mean and standard deviation, respectively.

From the primitive streak stage, which in vivo comprises multipotent progenitors, the cells were treated for 48 hours to optimize conditions for induction of IM fate. We found that a combination of retinoic acid (RA), FGF2, and inhibitors of BMP and TGFβ signaling enabled efficient specification of PAX2-positive IM progenitors. Consistent with an anterior or pronephric fate, on average 88.5 ± 2.4% of cells at day 3 were positive for both GATA3 and PAX2 by immunofluorescent staining (Fig. 1d–e). We also confirmed similarly high levels of expression of other pronephric IM markers including PAX8, LHX1, and HOXB7 (Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 2c). Conversely, genes expressed in posterior IM regions, such as WT1, SIX2, EYA1 and HOXA11, were either absent or expressed at negligible levels in the cultures in contrast to their expression in differentiated metanephric progenitors5 (Extended Data Fig. 2e). The cells rapidly lost expression of the mesendoderm progenitor genes TBXT and MIXL1 as they adopted an IM fate from days 1–3 (Fig. 1c and Extended Data Fig. 2c). Through subtraction of individual components, we found that this particular signaling combination was highly synergistic and each factor was required for robust IM specification (Extended Data Fig. 2d). FGF2 was particularly important, consistent with the established role for FGFs in the early stages of embryonic kidney development4, 18–21. Inhibition of both BMP (with LDN193189) and TGFβ (with A83-01) signaling was required for the efficient repression of competing lateral plate mesoderm (FOXF1) and definitive endoderm (SOX17) fates, respectively (Extended Data Fig. 2f). Taken together, these initial differentiation stages represent a straightforward and rapid method to generate pronephric progenitor cells with high efficiency.

Following its initial specification, the pronephric IM generates a cord of cells termed the nephric duct (ND; alternatively named the Wolffian duct), which migrates caudally toward the metanephric mesenchyme. To facilitate these complex morphogenetic events, we transitioned the day 3 monolayer via dissociation and re-aggregation into spheroids that varied in size between 50–200 μm (Fig. 1f and Extended Data Fig. 3a). Based on the high efficiency of IM induction the cells were plated into aggregates in bulk without sorting or purification. Additionally, the cells could be plated into patterned microwell plates to generate large numbers of uniformly sized and shaped aggregates (Extended Data Fig. 3c). These structures were maintained in a serum-free growth medium containing only RA, FGF9, and later GDNF (Extended Data Fig. 3b; neither FGF2 nor FGF8 were able to support differentiation), and over several days they underwent spontaneous organization whereby GATA3-expressing cells sorted together into a sphere and spatially excluded a smaller GATA3-negative cluster (Fig. 1f). The GATA3-expressing population remained positive for PAX2, PAX8, HOXB7 and LHX1, and it acquired expression of the ND markers EMX2 and RET (Fig. 1g and Extended Data Fig. 3d). The signaling molecules WNT9B and WNT11, which are expressed in the developing ND, were also up-regulated during this period (Extended Data Fig. 3e).

To further define the cell types present in the spheroids at day 7, we performed single cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and analyzed 609 cells after filtering for quality and multiplets. As shown in the Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) in Fig. 1h, this yielded four related cell clusters. Clusters 2 and 3 shared high levels of expression of ND markers, including PAX2, PAX8, GATA3, EMX2, and RET (Fig. 1h and Extended Data Fig. 3f). In agreement with published reports6, these cells also expressed KIT and CXCR4 (Extended Data Fig. 3f). Conversely, ND markers were largely absent in clusters 0 and 1, which corresponded to the GATA3-negative cells shown in Fig. 1f. Instead, the GATA3-negative expressed stromal lineage markers PDGFRA and COL1A1 (Fig. 1h and Extended Data Fig. 3f–g) and also WT1, OSR1, TBX18, and ALDH1A2 (Extended Data Fig. 3f–h), which are found in the stroma surrounding the ND during mouse development22. The scRNA-seq analysis did not identify the presence of off-target lineage differentiation (Extended Data Fig. 3i), such as neurectoderm (PAX6), paraxial mesoderm (PAX3, TBX6), or lateral plate mesoderm (HAND1) cells.

The analyses at day 7 revealed a ND identity, but CDH1 was only weakly and heterogeneously expressed in these cells (Fig. 1i). This signature was therefore analogous to the cells at the leading edge of the ND, a proliferative and chemotactic population that drives the caudal extension of the ND23, 24. These ‘leader’ cells were recently characterized in vivo using single cell transcriptomics25 (identified as ‘NDpr4’ cells), which identified that they express Aldh1a3 and are the likely immediate precursors to the UB. The differentiated spheroids at day 7 similarly expressed high levels of ALDH1A3 in the ND population (Fig. 1i), indicating that they exhibited a state similar to the NDpr4 population. Therefore, over 7 days of culture, hPSCs were efficiently differentiated into pronephric IM followed by three-dimensional spheroids comprising ND leader cells. Furthermore, this protocol can be applied across both hESC and hiPSC lines with consistent efficiency (Extended Data Fig. 4a–f).

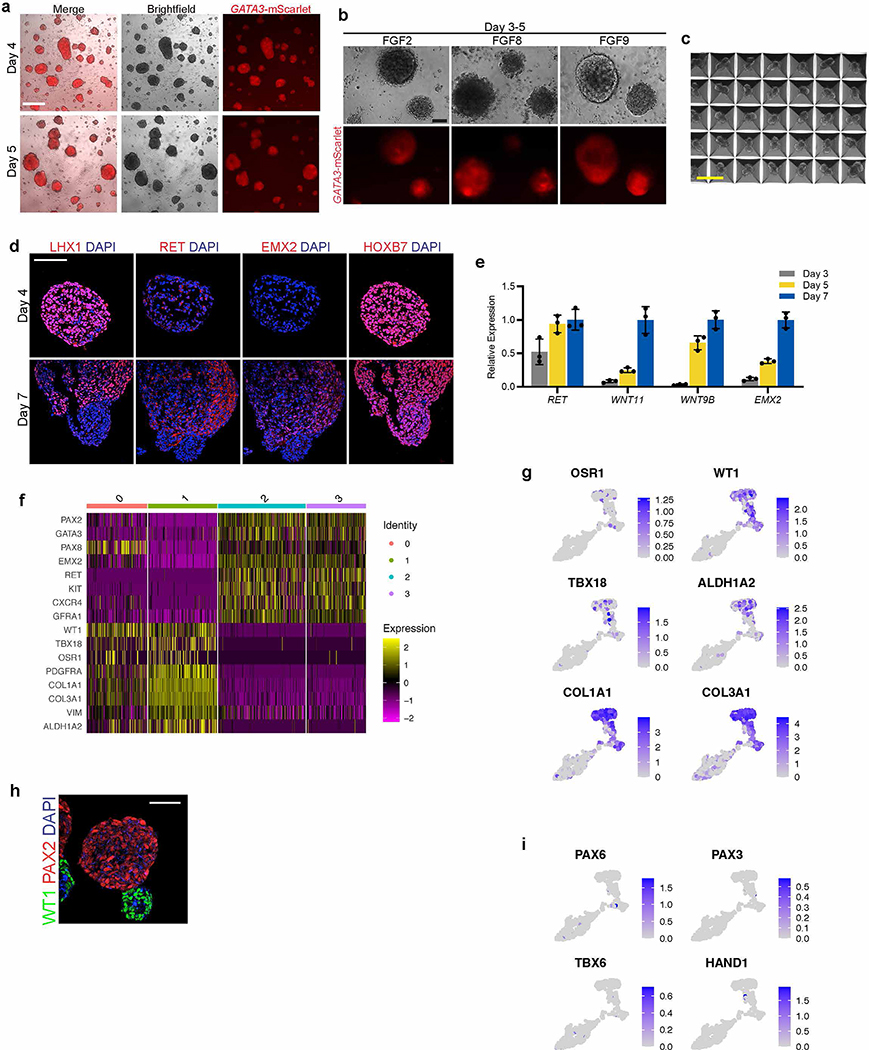

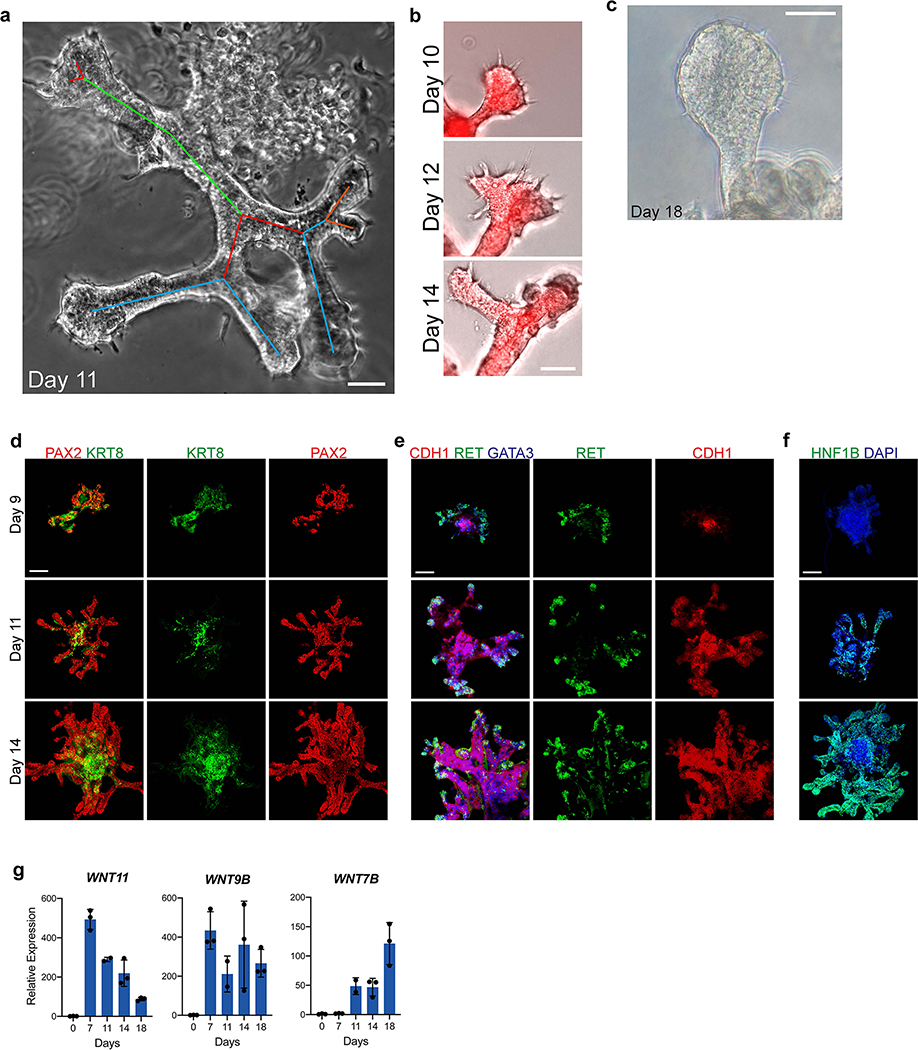

Generation of branching UB organoids

Branching morphogenesis and interaction with metanephric mesenchyme are defining features of the UB. Isolated fetal rodent UBs can grow as branching cultures in three-dimensional matrices26, which was initially achieved with specialized conditioned media14 and later in more defined conditions27. Drawing upon these published observations, we embedded the day 7 ND spheres into a dome of extracellular matrix (Matrigel) and exposed them to signaling conditions that promote a UB branching phenotype. We used serum-free conditions and a combination of growth factors including GDNF and FGF10, both of which have been well characterized for their ramogenic effects on the UB28–30, as well as inhibitors of BMP and TGFβ signaling given the known repressive effects of these pathway on UB budding and branching31–33. These conditions led to a pattern of growth and morphogenesis over one week of culture that was unprecedented for hPSC-derived tissues in that they exhibited a rapidly growing and iterative branching pattern (Fig. 2a). Each of the original ND spheroids generated multiple buds that sprouted in all directions to form elongating tubules, and the epithelia then underwent branching by several rounds of terminal bifurcation (Fig. 2a–c and Extended Data Fig. 5a–b). By day 14, the structures comprised an array of branched epithelial stalks with rounded tips that resembled the ampullae of the fetal UB (Fig. 2c). This pattern qualitatively paralleled UB branching behavior in vivo, and it very closely resembled the growth of fetal UBs in isolation in culture14. Beyond day 14, the rate of branching and overall growth in the UB organoids slowed and the bud tips at latter stages sometimes formed enlarged knob-like swellings (Extended Data Fig. 5c).

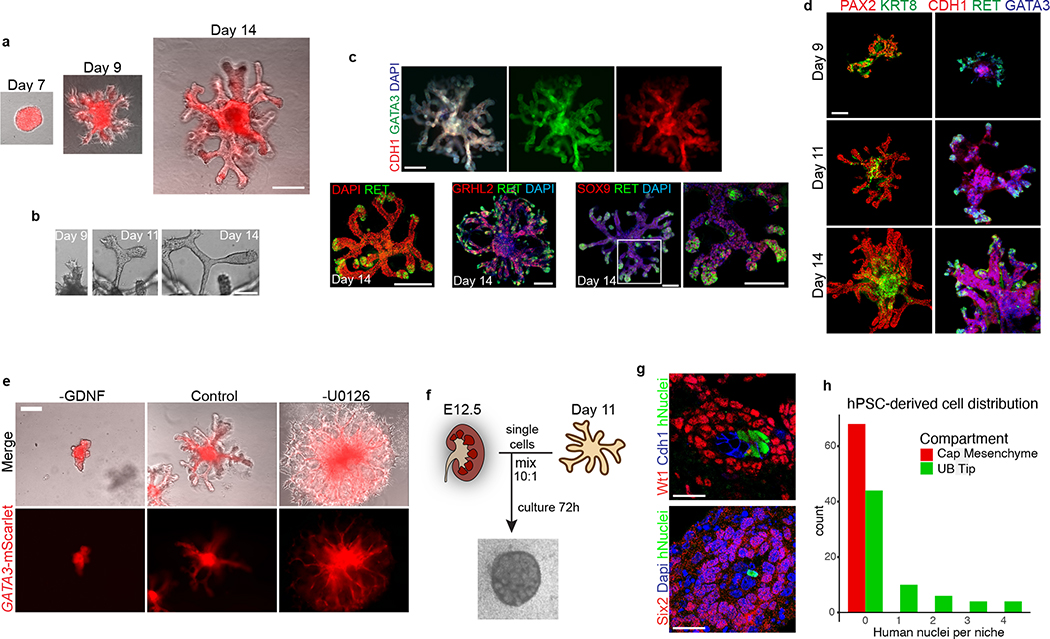

Figure 2. Three-dimensional development of branching UB organoids.

a, Between days 7–14, the nephric duct spheres underwent extensive remodeling and growth into UB organoids, which grew in a pattern of elongating stalks and branching tips similar to the fetal UB. b, Bifurcative branching was frequently observed over this time period. c, Molecular analysis at day 14 reiterated a complex branched architecture and the entire epithelium exhibited expression of GATA3, GRHL2, SOX9, and CDH1. The progenitor marker and GDNF co-receptor RET was exclusively expressed in in the distal tip domains. d, Wholemount IF staining at days 9, 11, and 14 revealed uniform expression of PAX2 with progressive segregation of the tip (RET) and stalk (KRT8) domains. e, In the absence of exogenous GDNF, the nephric duct spheres largely failed to grow and branch. Conversely, removal of the MEK inhibitor U0126 from the culture medium led to a more disorganized branched plexus of fine epithelial cords with terminal filopodia rather than rounded UB-like tips. f, To functionally assess the competence of UB organoid cells, we mixed them with dissociated murine kidneys isolated at embryonic day (E) 12.5, pelleted the cells into chimeric aggregates, and cultured on filter disks for 72 hours. g, IF staining showed the incorporation of induced UB cells (indicated by a human-specific antibody) into the Cdh1-expressing UB tip domains but not in the Six2+Wt1+ nephron progenitor compartment. h, Histogram depicting the frequency at which we observed a human cell or cluster of cells in the examined progenitor niches. Scale bars, 200 μm (a and c-e), 100 μm (b) and 20 μm (g).

The epithelium of the UB organoids maintained high expression of UB transcription factors PAX2 and GATA3, while expression of other developmental UB genes (including HNF1B, GRHL2, and CDH1) increased over time in a centrifugal pattern as the epithelialized phenotype was reinforced (Fig. 2c–d and Extended Data Fig. 5d–f). Notably, spontaneous development of organized tip-stalk radial polarity was readily apparent as early as day 9, with KRT8 confined to the central or stalk-like regions and RET expression in the periphery of the epithelium (Fig. 2c–d). As the UB organoids grew, the relative proportion of tip domain cells decreased as demonstrated by waning WNT11 expression and an increase in the stalk marker WNT7B (Extended Data Fig. 5g). Throughout these stages, however, RET remained expressed and specifically localized to only the distal tip domains (Fig. 2c–d), consistent with its pattern in the developing UB in vivo34. Therefore the UB organoids closely mimicked normal stages of early development, at the levels of both morphogenesis and molecular patterning.

The morphogenesis of UB organoids was dependent upon on a balance of both activators and inhibitors of the MEK/ERK signaling pathway. The organoids exhibited severe reduction of growth and branching in the absence of exogenous GDNF (Fig. 2e), the most well-characterized growth factor in UB development35. Conversely, removal of the MEK inhibitor U0126 from the culture medium led to highly branched structures that comprised very fine tubules with prominent cellular extensions and filopodia-like processes at the tips (Fig. 2e). This phenotype suggested that unopposed MEK activation prevented the ND leader cells from undergoing maturation and complete epithelialization. This effect on epithelial morphology paralleled observations previously described in the ND leader cells in the chick embryo24.

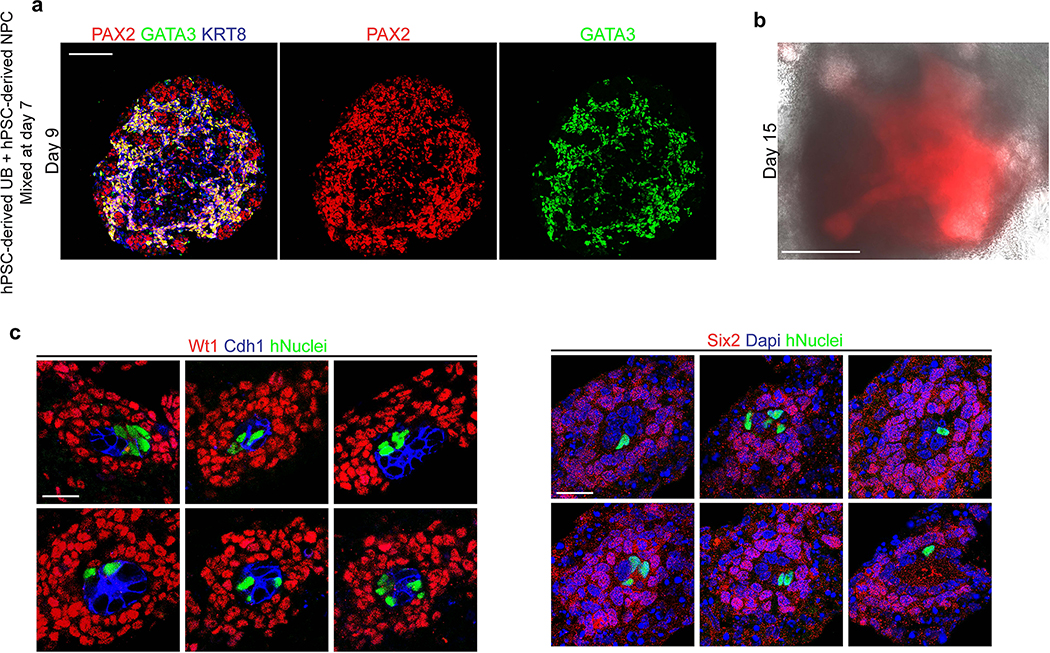

Next, we assessed the competence of UB organoids to participate in tissue-tissue interactions in the nephrogenic niche. UB cells at day 7 were combined with putative metanephric progenitors derived during kidney organoid differentiation5, and the resulting UB and metanephric tissues compartmentalized within the inner and outer parts of the organoids, respectively (Extended Data Fig. 6a). We never observed meaningful branching or maintenance of undifferentiated nephron progenitors (Extended Data Fig. 6b), similar to what has been reported elsewhere36, 37. Consequently, we used a well-established fetal kidney explant culture system38 to specifically interrogate the function of the UB organoids. Murine metanephroi from embryonic day 12.5 were dissociated and mixed with a small proportion of hPSC-derived UB cells at a ratio of 10:1 (Fig. 2f). We cultured the explants for 72 hours and analyzed the nephrogenic zones for the presence of organoid-derived cells using a human-specific antibody. We frequently observed human cells incorporated in the UB tips surrounded by Six2+Wt1+ nephron progenitors (Fig. 2g–h and Extended Data Fig. 6c) in each of the explants (n=4) examined, and their close association with nephrogenic cells implied that they were responding appropriately to the murine patterning cues. Conversely, human cells were never observed in the capping mesenchyme itself as their fate was already restricted to the UB lineage.

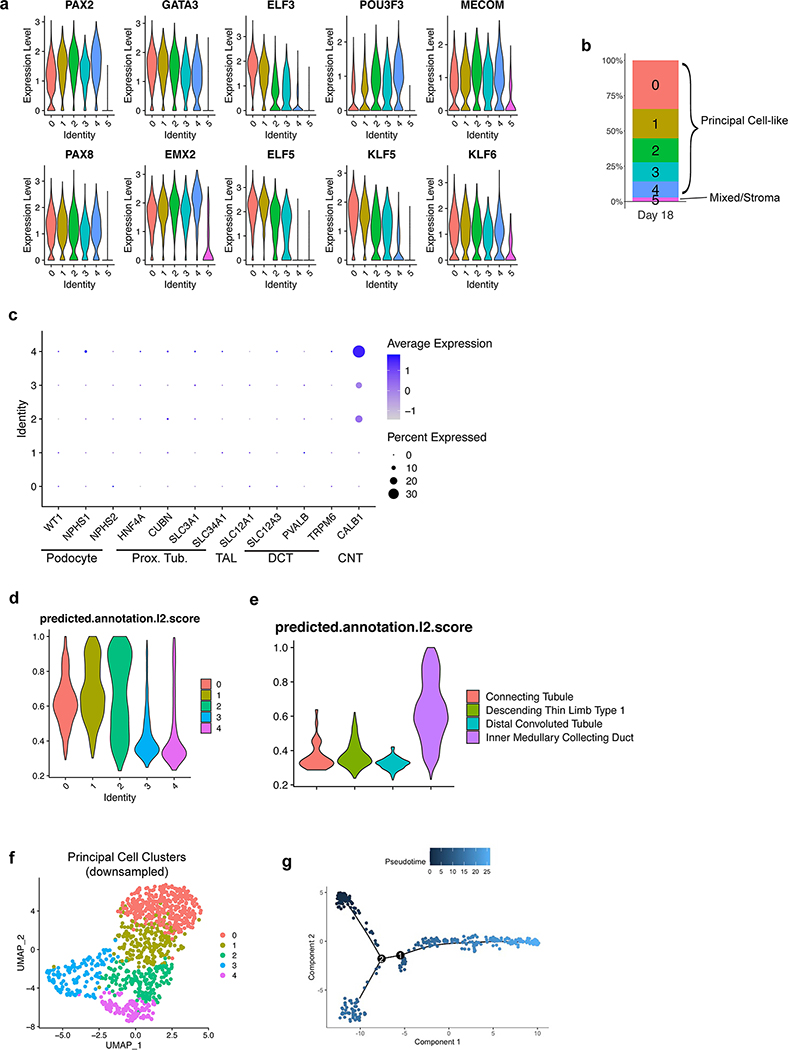

Differentiation of collecting duct epithelia in UB organoids

We monitored the developing UB organoids for the formation of differentiated CD cell types (schematized in Fig. 3a). They manifested a progressive increase in expression of principal cell markers at the transcriptional level between days 11–18, including the transcription factor ELF5 and water transporter AQP2 (Fig. 3b). As immunofluorescent staining revealed only few cells with low level AQP2-positivity (Fig. 3c), however, we hypothesized that the culture medium was inhibitory to epithelial maturation since it was designed to support the progenitor state. When we replaced this medium at day 14 with a basal medium devoid of other factors and supplemented only with the hormones arginine vasopressin (AVP) and aldosterone (Aldo), within 3–4 days there was repression of progenitor genes and significant up-regulation of ELF5 and AQP2 (Fig. 3b–c). The level of AQP2 exceeded expression in a sample of human kidney cortex by greater than 30-fold when assessed by qPCR, although PCs are only a minority of the many cell types in the kidney cortex. We therefore refer to these as CD organoids under these differentiation conditions, and they contained numerous AQP2+ cells throughout the tubular epithelia that was frequently localized to the luminal (apical) membrane (Fig. 3c–d), indicative of efficient PC specification and some extent of maturation.

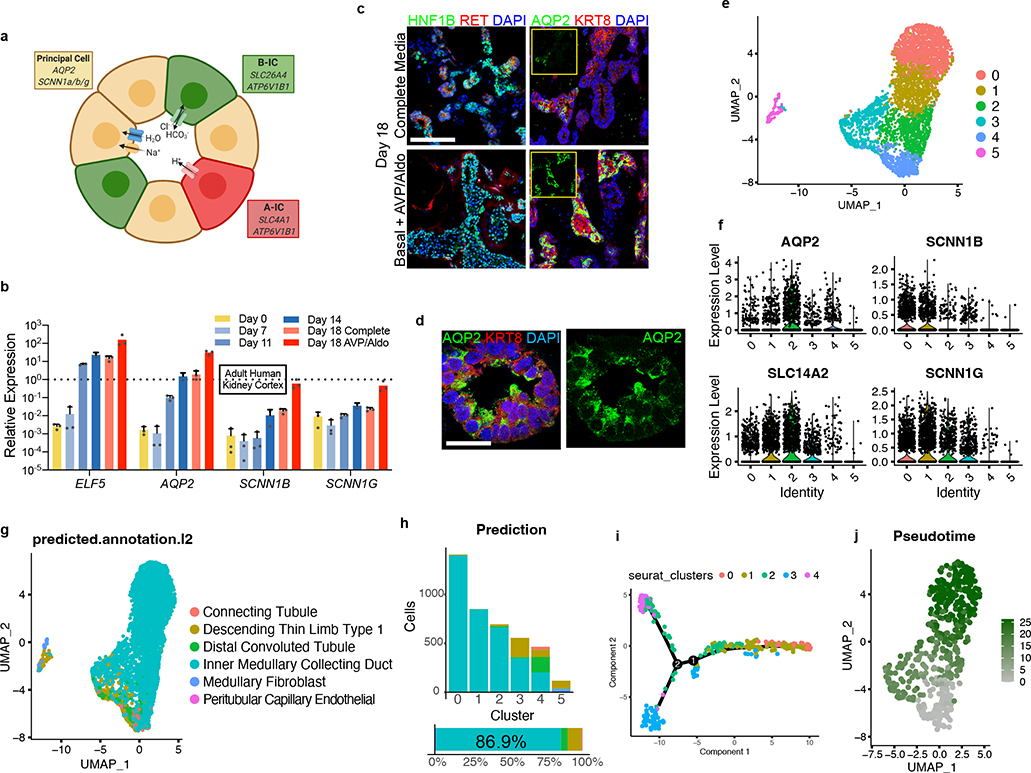

Figure 3. Differentiation of collecting duct epithelia from UB organoids.

a, Illustration demonstrating that the collecting duct epithelia comprise a mixture of principal cells, A-type, and B-type intercalated cells. b, Expression of markers ELF5, AQP2, SCNN1B, and SCNN1G increased over time, consistent with spontaneous formation and maturation of principal cells. When organoids were transitioned to a basal medium containing only AVP (10 nM) and Aldosterone (10 nM) from days 14–18, there was a marked increase in the expression of each of these genes. Dotted line represents expression observed in a sample of human kidney cortex. n=3 independent biological replicates per timepoint/condition. c, When the UB organoids were transitioned to the basal medium (with AVP/Aldo), the progenitor marker RET was downregulated in the epithelial tip domains, while AQP2 expression became more widespread and expressed at strikingly higher levels by IF. d, In numerous instances, AQP2 was localized in the epithelia nearer to the luminal or apical membrane, albeit it was not strictly apically localized. e, UMAP of scRNA-seq analysis of day 18 organoids that were cultured for four days in basal media with AVP/Aldo. f, Violin plots demonstrate expression of principal cell markers in clusters 0–4, which appear to be related given close association on UMAP, but not in cluster 5. g-h, Accordingly, integration and reference mapping to adult human kidney dataset predicted an ‘inner medullary collecting duct’ in 86.9% of cells in the dataset. While clusters 0–2 were nearly uniformly mapped to a collecting duct fate, clusters 3 and 4 contained a small proportion of cells that mapped to alternative tubular fates, namely the descending thin limb and distal convoluted tubule. i-j, Lineage trajectory analysis in Monocle predicted clusters 0 and 1 to be most differentiated cell types, while clusters 3 and 4 represented the earliest developmental stages in pseudotime. Scale bars, 100 μm (c) and 20 μm (d). Column and error bars represent mean and standard deviation, respectively.

To better characterize the differentiated cell types in the CD organoids, we generated a scRNA-seq dataset of 4,095 cells isolated at day 18. The cells segregated into six clusters as shown in Fig. 3e. Clusters 0–4 were tightly associated and constituted the vast majority (>97%) of cells, while only 118 cells were found in the distant cluster 5 (Extended Data Fig. 7b). Based on their high expression of representative marker genes including both transcription factors and functional channels/transporters (Fig. 3f and Extended Data Fig. 7a), clusters 0–4 were identified as CD PCs. For an unbiased approach to further categorize these clusters, we used the recently described Azimuth toolkit39 to perform reference mapping of our dataset to a multimodal dataset of 64,693 adult human kidney cells40. Indeed, 86.9% of cells in our dataset mapped to a predicted ‘Inner Medullary Collecting Duct’ fate (Fig. 3g–h) during this analysis, in agreement with our conclusion that CD organoids comprised a large majority of PCs.

Aside from a CD fate, the next three highest predicted cell types in the Azimuth integration analysis were descending thin limb (dTL), distal convoluted tubule (DCT), and connecting tubule (CNT) at 7.6%, 4.6%, and 0.8% (Fig. 3g–h), respectively, which all derive from the metanephric lineage. This was surprising considering that expression of the canonical markers of metanephic nephron segments was absent in the dataset (Extended Data Fig. 7c); for example, the highly specific DCT marker SLC12A3 was undetected. By reasoning that these segments were more likely to resemble the CD at early progenitor states due to overlapping expression of transcription factors, we hypothesized that the CD organoids contained cells that represented a continuum of differentiation. Lineage trajectory interrogation using Monocle on a downsampled subset of cells from clusters 0–4 (Extended Data Fig. 7f) showed a predicted lineage projection (Fig. 3i–j and Extended Data Fig. 7g) that supported a model in which clusters 0 and 1 were the most differentiated while clusters 3 and 4 were most immature. Indeed, clusters 3 and 4 contained nearly all of the cells that mapped to non-CD identities using Azimuth (Fig. 3g), and these clusters had markedly lower prediction scores (Extended Data Fig. 7d). Similarly, the prediction scores for all cells that mapped to non-CD fates were also quite low (Extended Data Fig. 7e), suggesting that reference mapping to adult tissues may be less accurate when querying more immature or undifferentiated cell types.

Induced PCs exhibit ENaC-mediated sodium transport

The CD mediates hormone-responsive reabsorption of sodium and water via the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) and AQP2 channels, respectively. In addition to AQP2, the PCs in the organoids at day 18 exhibited expression of ENaC subunits (SCNN1A/B/G) (Fig. 4a); in particular, the beta and gamma subunits were most abundant transcriptionally and we confirmed expression at the protein level using an antibody specific to SCNN1B, while the alpha subunit (SCNN1A) was expressed at lower levels. With their expression of ENaC and apicobasal polarity (Fig. 3d), we hypothesized that the cells might exhibit physiologic activity. The ENaC-mediated sodium reabsorption is an electrogenic process, so we transitioned organoid-derived cells to a two-dimensional transwell format to investigate their transepithelial electrophysiologic properties. Organoids were dissociated and re-plated in 2D tissue culture plates in a medium previously described for use with mouse CD cell lines11. From this emerged a proliferative cell line that formed a confluent homogenous epithelium (Fig. 4b), which we were able to serially passage while maintaining the epithelial phenotype.

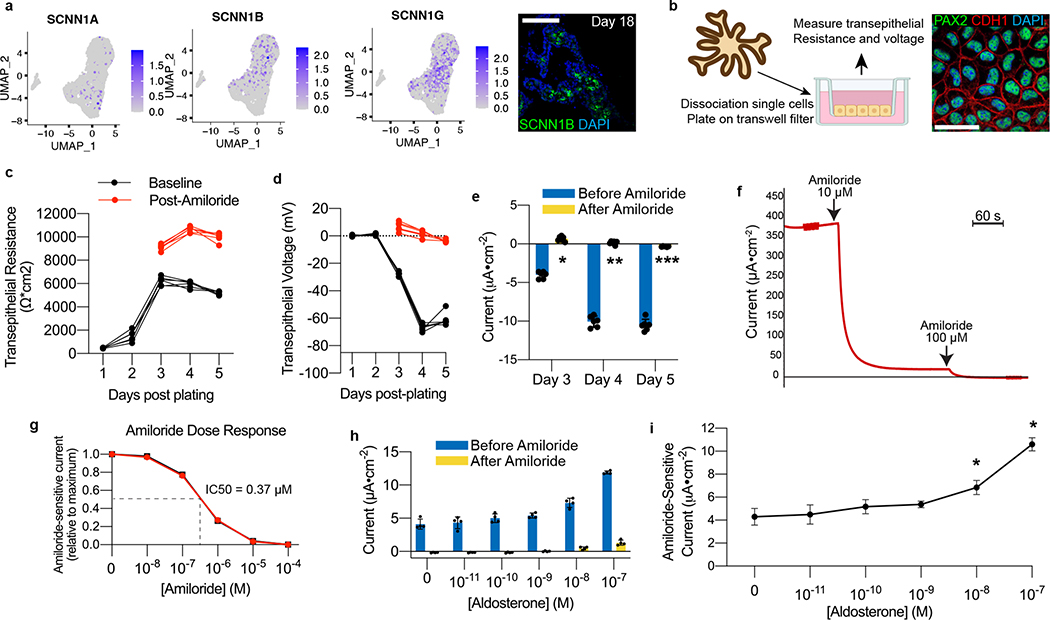

Figure 4. hPSC-derived model for interrogating ENaC-mediated sodium transport.

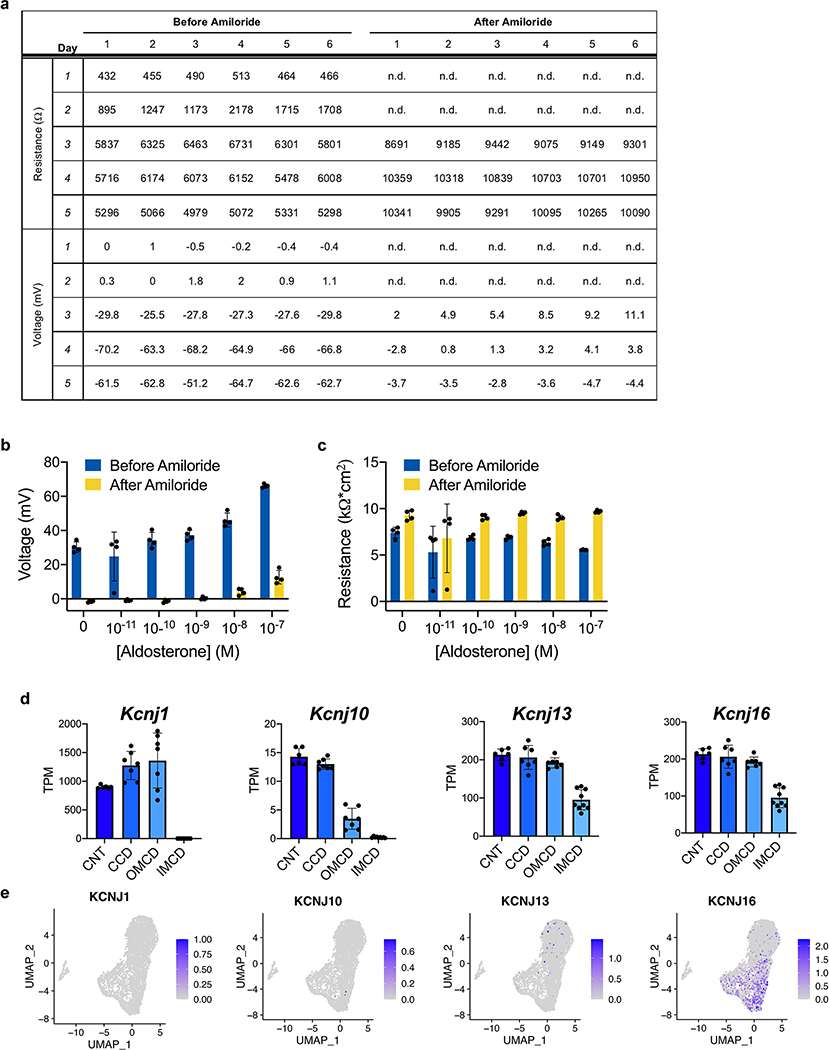

a, Expression of the ENaC subunits SCNN1B and SCNN1G was abundant in scRNA-seq data, and we detected SCNN1B at the protein level in day 18 organoids. b, To explore functional capabilities, organoids at day 18 were dissociated and plated onto two-dimensional transwell filters for electrophysiological interrogation. This led to confluent epithelia that maintained expression of collecting duct markers PAX2 and CDH1. c-d, As the cells became confluent, there was at first a steep increase and then plateau in the transepithelial resistance, which was then followed by the emergence of a transepithelial voltage. The voltage was entirely suppressible within three minutes of addition of the ENaC antagonist amiloride (10 μM), which also raised the resistance across the epithelium. e, The resulting current generated was calculated using Ohm’s Law, and it was completely ablated immediately following addition of amiloride, confirming the conductance was ENaC-dependent. *p=5.3×10−9, **p=5.7×10−8, ***p=4.5×10−6; two-tailed student’s t-test comparing results before and after amiloride; n=6 biological replicates, data representative of 3 independent experiments. f, Under closed-circuit conditions with voltage clamping in Ussing chamber, the current produced by the epithelium was similarly sensitive to amiloride, and it was completely abolished upon increasing the concentration to 100 μM. g, Amiloride induced a dose-dependent inhibition of transepithelial current in Ussing chamber, with representative dose-response curves shown from two independent wells. h-i, Addition of aldosterone for 24 hours led to a dose-dependent increase in transepithelial current measured under closed circuit conditions, and up to a maximum of approximately 2.5-fold increase in amiloride-sensitive current. *p<0.005; two-tailed student’s t-test compared to no aldosterone; n=4 independent biological replicates. Scale bars, 100 μm (a) and 20 μm (b). Column and error bars represent mean and standard deviation, respectively.

Following seeding, the cells developed a robust transepithelial resistance as they became confluent, which typically stabilized in the range of 5,000–6,000 Ohms•cm2 by day 3–4 (Fig. 4c). A significant voltage (−60–80 mV) and calculated current (−10 to −15 μA•cm−2) also emerged over this period, both of which reached a peak 1–2 days after the resistance had plateaued (Fig. 4d–e). To test for the presence of ENaC-mediated sodium current we briefly exposed cells to amiloride, a diuretic that is a specific antagonist of ENaC. The addition of amiloride completely abolished the transepithelial voltage and current within several minutes while simultaneously raising the transepithelial resistance (Fig. 4e and Extended Data Fig. 8a), essentially reducing the open-circuit current to zero and demonstrating the cells’ exhibited robust ENaC-mediated sodium reabsorption. We further demonstrated the same response in a closed-circuit system using voltage clamping in an Ussing chamber, which allowed for real-time measurements of short-circuit current. In this system, amiloride at 10 μM inhibited >95% of the short-circuit current within several minutes, and further increasing the concentration to 100 μM subsequently eliminated the small amount of residual current (Fig. 4f). In fact, in the Ussing chamber the cells displayed a stereotypic pharmacokinetic dose-response relationship to amiloride with an estimated IC50 of 0.37 μM (Fig. 4g), which is within the expected range of 0.1–0.5 μM41.

In vivo, ENaC activity is positively regulated by mineralocorticoid signaling, so we tested whether the CD organoid-derived cells exhibited physiologic response to aldosterone. The cells were first cultured in the absence of dexamethasone for several days to wash out any glucocorticoid effect, and we then exposed the cells to varying concentrations of aldosterone for 24 hours. Aldosterone induced a dose-dependent increase in transepithelial voltage and current (Fig. 4h and Extended Data Fig. 8b–c) and a statistically significant ~2.5-fold increase in amiloride-sensitive current at 10–100 nM (Fig. 4i). Therefore, the epithelium exhibited intact physiologic response to mineralocorticoid hormone signaling. Unlike the ENaC subunits, there was little expression of potassium channels in the organoid at day 18 with the exception of KCNJ16 (Extended Data Fig. 8e), which is found in the inner medullary CD42 (Extended Data Fig. 8d).

Induction of intercalated cells within CD organoids

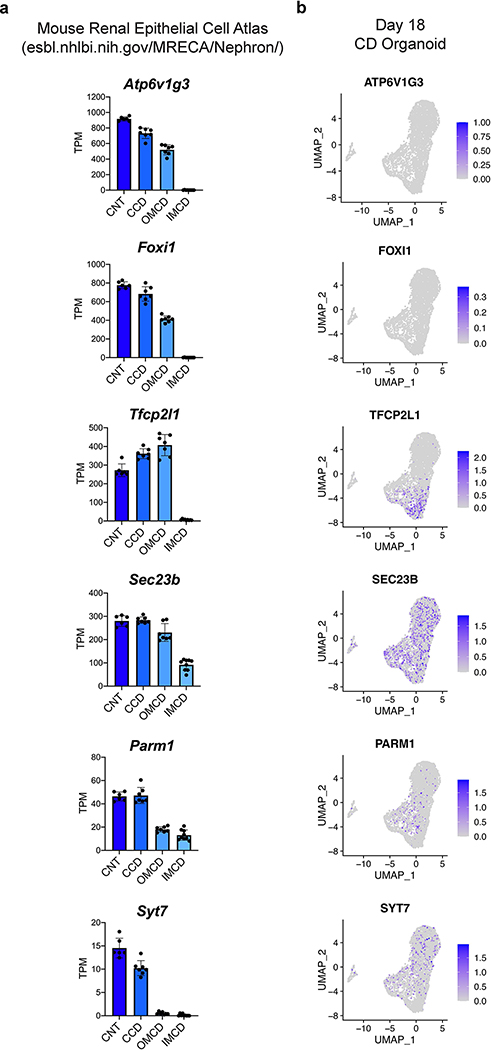

Although PCs differentiated readily under permissive culture conditions, scRNA-seq data revealed an absence of the IC-specific transcription factor FOXI1 and of its obligatory upstream regulator TFCP2L143 (Extended Data Fig. 9). Because the organoids so strongly exhibited a signature consistent with inner medullary CD (Fig. 3g–h), we hypothesized that these IC-promoting factors might be regionally restricted along the corticomedullary axis of the CD. Using data generated from microdissected nephron segments from the adult mouse kidney42, we indeed found that expression of both Foxi1 and Tfcp2l1 were completely and specifically absent in the inner medullary CD (Extended Data Fig. 9). While markers of the transitional cells that exhibit both PC and IC characteristics44, such as SEC23B, PARM1, and SYT7, were weakly but variably expressed within the organoids (Extended Data Fig. 9), the low level of TFCP2L1 likely made the cells refractory to spontaneously inducing FOXI1 and adopting the IC phenotype.

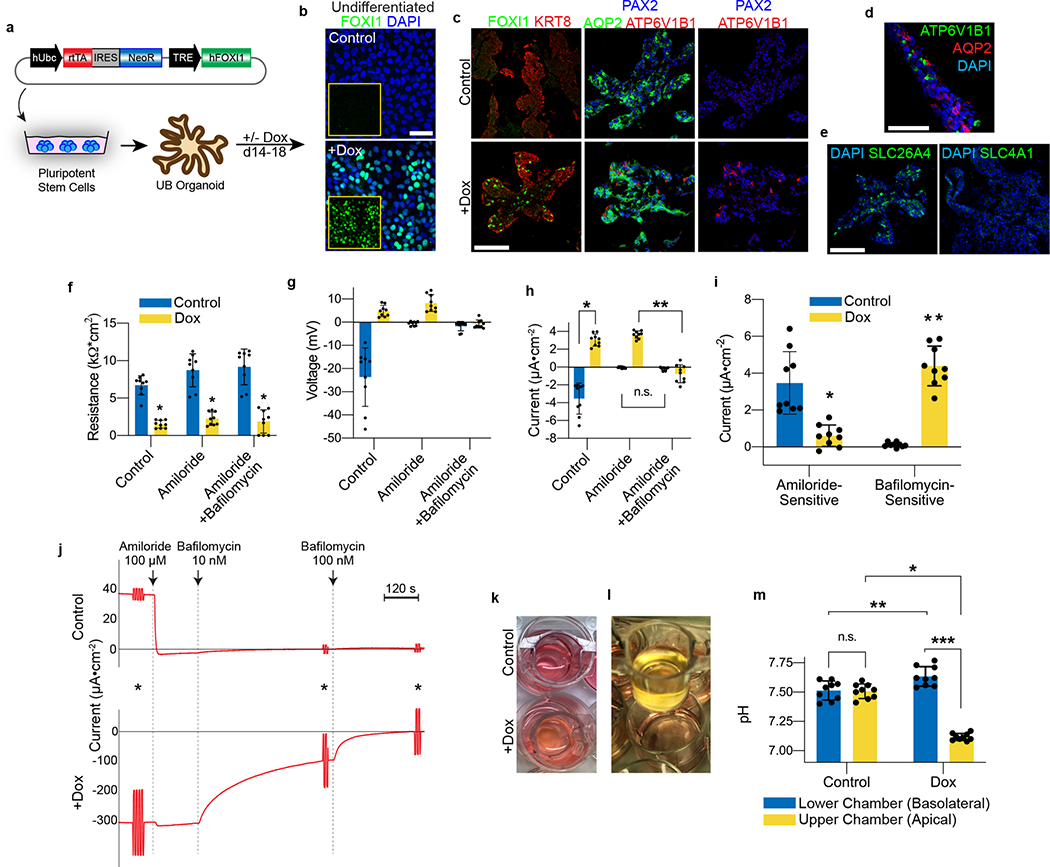

Based on prior reports that Foxi1 is necessary for IC development45, we generated a transgenic hPSC line for temporally inducible expression to determine whether FOXI1 is sufficient for cell specification (Fig. 5a–b). Exposure of CD organoids to doxycycline from days 14–18 resulted in a heterogenous expression pattern that was analogous to the normal salt-and-pepper distribution of FOXI1 in vivo (Fig. 5c). We also observed a similar pattern of cells with strong expression of the V-type ATPase subunit ATP6V1B1 distributed within the epithelium (Fig. 5c–d), confirming that FOXI1 was sufficient to induce IC specification. Although AQP2+ PCs still formed in the presence of doxycycline, these cells were distinct from those that expressed IC markers. We detected abundant expression of the B-type IC marker SLC26A4 (Fig. 5e), the apical transporter that mediates tubular secretion of bicarbonate in the CD, while the A-type IC marker SLC4A1 was not observed.

Figure 5. FOXI1 expression is sufficient for intercalated cell fate determination.

a, hESCs were transduced with lentivirus encoding a doxycycline (dox)-inducible hFOXI1 construct, and the cells were differentiated into UB organoids. b, In the undifferentiated state, FOXI1 expression was not observed in the absence of dox, but it was widely induced after exposure to dox for 48 hours. c, While control organoids exhibited no expression of FOXI1 or IC markers, the short exposure to dox induced formation of FOXI1- and ATP6V1B1-expressing ICs in a salt-and-pepper distribution. AQP2 expression was maintained in some cells but was mutually exclusive with the induced ICs. d, In the dox-induced organoids at day 18, the epithelium comprised an assortment of AQP2-expressing principal cells and ATP6V1B1-positive ICs. e, In the dox-induced organoids, only B-ICs were observed that expressed SLC26A4, while there were no SLC4A1-expressing A-ICs. f, In the 2D cell culture model, doxycycline-treated cells exhibited significant reduction in transepithelial resistance. *p<0.0005; two-tailed student’s t-test. g-h, While control cells had a negative transepithelial voltage and current that was suppressed by amiloride, the doxycycline-treated cells had a positive baseline potential and current that was augmented by amiloride but completely suppressed by the V-ATPase inhibitor bafilomycin (10 nM). *p=2×10−6, **p=1.3×10−7, two-tailed student’s t-test (h). i, Therefore control cells displayed amiloride-sensitive current while doxycycline induced a predominantly bafilomycin-sensitive current. *p=2.5×10−4, **p=1.0×10−6, two-tailed student’s t-test. In f-i, n=9 independent biological replicates per condition over two separate experiments. j, Experiments in Ussing chamber confirmed that FOXI1 expression resulted in bafilomycin-sensitive rather than amiloride-sensitive short-circuit current. Shown are representative tracings from two independent experiments. Asterisks indicate 1V pulses to assess transepithelial resistance. k, Doxycycline-treated cells induced acidification of the cell culture medium, which (l) was only observed in the apical chamber of the transwells. m, Measured using a pH meter, the FOXI1-induced cells generated a pH gradient of ~0.5 units between the upper and lower chambers of the transwell. N=9 independent biological replicates per condition. *p=1.6×10−9, **p=0.007, ***p=7.8×10−9, two-tailed student’s t-test. The data shown in k-m have been observed in more than 8 independent experiments. Scale bars, 50 μm (b-c) and 100 μm (d-e). Column and error bars represent mean and standard deviation, respectively.

We examined whether FOXI1 expression disrupted the electrophysiologic PC phenotype in the organoid-derived cell line. Transgene induction led to a statistically significant reduction in the transepithelial resistance to approximately 25% of control levels (Fig. 5f), consistent with a disruption of the epithelial tight junctions that are characteristic of PCs. More strikingly, it consistently reversed the direction of the transepithelial voltage (Fig. 5g), and the calculated open-circuit current further exemplified this stark contrast in the baseline electrical state between these two conditions (Fig. 5h). The induced cells also largely lost sensitivity to amiloride (Fig. 5h), so we hypothesized that FOXI1 led to the emergence of activity of the IC-specific V-type ATPase proton pump, which could have electrogenic function by mediating the movement of an unpaired proton (H+) across the apical membrane into the lumen. Indeed, the addition of the V-type ATPase inhibitor bafilomycin completely suppressed both the voltage and calculated current observed in the FOXI1-induced cells (Fig. 5g–h). Therefore, the inducible expression of FOXI1 was sufficient to toggle between PC and IC states that exhibit ENaC (amiloride-sensitive) and V-type ATPase (bafilomycin-sensitive) activities, respectively (Fig. 5i). We confirmed these results under closed circuit conditions in Ussing chambers, where FOXI1 induction led to reversal of the direction of baseline short-circuit current, a small increase in current following treatment with amiloride, and near complete inhibition of the current in response to bafilomycin (Fig. 5j).

ICs in the CD use V-type ATPase to generate large proton gradients and can acidify the urine to a pH of 5 in order to excrete dietary acid loads and maintain acid-base homeostasis. FOXI1-induced electrogenic activity of V-type ATPase coincided with increased acidification of the medium in the upper but not lower chamber of the transwell (Fig. 5k–l) and generation of a gradient across the epithelium of up to 0.5 pH units (Fig. 5m). Compared with control cells, the lower chamber was actually alkalinized to a modest but statistically significant degree. The changes occurred rapidly, in as little as 12 hours after replacement with fresh medium. This acidification phenotype was more consistent with that of A-ICs with the apical proton secretion. Therefore, FOXI1 was sufficient to promote an IC phenotype in the hPSC-derived CD, and it is possible that the specific IC phenotype was dependent on the culture environment.

Discussion

We have delineated a robust directed differentiation strategy for the de novo generation of UB and CD epithelia from hPSCs at unprecedented efficiency and without cell sorting or purification (Extended Data Table 1). The sequential steps progress through the stages of ureteric epithelial development, as verified by extensive molecular characterization including scRNA-seq. The UB organoids manifest a complex three-dimensional morphogenetic trajectory, which parallels that of isolated rodent UBs grown in 3D culture14, including bifurcative branching with polarized tip-stalk organization. Correlating with their physiologic growth properties, the UB cells are competent to integrate into a chimeric developmental progenitor niche. The organoids differentiate into CD epithelia at >95% efficiency based on scRNA-seq clustering, and they represent the inner medullary CD at >85% efficiency using unbiased computational analyses. They contain AQP2/ENaC-expressing PCs, which exhibit a robust capacity for electrogenic sodium transport. In response to FOXI1 expression, the epithelia differentiate into ICs with V-type ATPase activity and proton secretion. Overall, this differentiation approach generates UB and CD tissues that recapitulate a range of features, including developmental stages, growth and morphology, cell fate determination, and ion transport physiology, thereby opening opportunities for diverse investigations and applications (some examples are summarized in Supp. Table 1).

The protocol offers high efficiency, reproducibility, and relative ease of implementation. We carefully measured each of the early steps that lead to ND fate to enable straightforward optimization and application of the protocol. Previous methods reported low efficiencies of ND induction (18–46%7, ~40–60%6, and 36–55%8) and therefore required cell sorting, which may eliminate potentially important supporting populations, such as the stromal cells we described at day 7. Our approach successively induces mesendodermal and pronephric IM fates in the monolayer format with >95% TBXT- and >90% GATA3-positive cells, respectively, resulting in negligible off-target differentiation detected in the ND spheroids at day 7 and >95% CD cell types in the organoids at day 18. Our method is readily scalable, as progenitors plated into a patterned microwell plate at day 3 reliably form ~1,200 UB spheroids in a single well (Extended Data Fig. 3c), with nearly 100% of the spheres exhibiting both the ND and stromal progenitor domains and the competence to form branching organoids. Scale-up using previous methods for propagating hPSC-derived UB progenitors required laborious manual microdissection of the individual tip domains for serial passage8, 9.

The iterative branching of the UB is a key determinant of kidney architecture and nephron endowment, as perturbed branching leads to a spectrum of renal hypodysplasia including congenital birth defects in humans46, 47. The UB organoids described here exhibit analogous branching behavior, in contrast to previous methods for in vitro propagation and expansion of hPSC-derived UB progenitor cells that produced rapidly growing epithelia but with a folded or ‘flowering’ phenotype with cells predominantly biased toward the tip fate and lacked dichotomous branching8–10. Another strategy using embryoid body-based differentiation, cell sorting, and serum-containing growth medium generated UB organoids with good tip-stalk polarity and some evidence of terminal branching6, 7, but rather static growth over several weeks of 3D culture. Our organoid model more closely resembles the culture of isolated fetal UB14, with the capacity for dynamic growth and bifurcative branching, as well as maintenance of the stereotypic tip-stalk morphology. The branching was somewhat disorganized as expected given the lack of organizing mesenchyme48, but these structures will be valuable in future research on human kidney tissue engineering once they can be assembled with authentic metanephric-like progenitors. Previous attempts to mix metanephric and ureteric-like cells did not result in branching morphogenesis or other developmental interactions between the compartments36, 37, but here we demonstrate that UB organoid-derived cells can incorporate durably in the UB tip compartment in an ex vivo developing kidney (Fig. 2f–h), which is compelling given that the cells had to compete across an interspecies boundary.

Despite recent progress in generating renal cell types from hPSCs, the derivation of cells with demonstrated physiologic kidney functions has remained elusive. Our organoid-derived PCs maintained in 2D culture demonstrate robust amiloride-sensitive vectorial sodium transport, which to our knowledge has not been reported in hPSC-derived renal epithelial cells or cultured human CD epithelium from any source. ENaC activity has been shown in immortalized mouse kidney cells11 but not in immortalized human kidney cells12. Our PCs also displayed appropriate responsiveness to aldosterone. The physiologic pathways recapitulated in the PCs are targets of two widely used drug classes (ENaC antagonists and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists), testifying to the cells’ potential in pharmacologic discovery and investigation.

Nephrology has lacked in vitro models of ICs for experimental study, as even primary ICs isolated from rodent CDs rapidly lose their differentiated phenotype in culture13. Our protocol did not spontaneously yield ICs (Fig. 5d and Extended Data Fig. 9b), which likely was related to the organoids’ inner medullary phenotype since this region normally is devoid of ICs (Extended Data Fig. 9a). It is also possible that the protocol lacks a necessary developmental cue since, in another system, organoids derived from hPSCs also did not form FOXI1+ ICs while organoids derived from primary mouse UB developed well differentiated ICs8. Nevertheless, we showed that exogenous FOXI1 expression reproducibly induced the IC fate, demonstrating that it is sufficient to promote specification of ICs and provides a method to reliably derive ICs in a controlled manner in vitro. The electrophysiologic properties of the sodium-reabsorbing PCs were converted into those of acid-secreting ICs more consistent with A-ICs that secrete protons across the apical membrane (Fig. 5k–l), as opposed to the B-IC fate induced in the 3D organoids (Fig. 5e). Although the underlying mechanisms remain unknown, this is in agreement with previous observations that primary isolated B-ICs rapidly drift toward an A-IC identity in 2D culture13. This phenomenon is likely related to the plasticity among IC subtypes49, 50, which allows physiologic adaptation in response to the metabolic demands of an organism or its environment. Our approach may be helpful in dissecting the mechanisms governing IC fate determination. Moreover, it provides a culture system that exhibits IC-specific electrophysiology and ion transport to enable interrogation of novel IC biology and function.

Although the CD epithelium represents only a small fraction of cells in the kidney, it has important roles as the final site of physiologic modification of urinary composition and as the structural system for urinary drainage. It is also a rare example of a tissue in which the basic functions of ion transport and electrophysiology are tightly correlated with pathophysiology and disease states, including salt sensitivity and hypertension, electrolyte imbalance, water disequilibrium, kidney stones, and distal renal tubular acidosis. The differentiated cells presented here will aid investigation of both inherited and acquired disorders involving the CD and of putative novel drug targets. As one example, the lithium-induced side effects of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus and chronic kidney disease are of interest in psychiatry, but their precise pathobiological mechanisms remain unknown. In animal models, impaired urine concentrating ability results from a mis-regulated balance between PC and IC populations51. Our hPSC-derived CD organoids will permit modeling of the impact of lithium on fate decisions between these two cell types.

In summary, we present an efficient method for derivation of UB and CD organoids from hPSC that progresses through the normal developmental stages and morphologic processes. The CD organoids efficiently form differentiated PCs and exhibit competence to induce ICs in response to FOXI1 expression. We have also used the organoids to derive a 2D cell line with similar cytodifferentiation characteristics, which exhibits robust ENaC-dependent sodium transport at baseline and V-type ATPase activity following FOXI1-mediated conversion to an IC state.

Methods

Pluripotent stem cell culture

The H9 (WA09) hESC line was obtained from Wicell. The BJFF.6 hiPSC line was kindly provided by Sanjay Jain (Washington University, MO). H9 hESC and BJFF.6 hiPSC were maintained in feeder-free conditions on hESC-qualified Matrigel (Corning, catalog no. 354277) in mTeSR1 media (Stem Cell Technologies, catalog no. 05850) using 6-well tissue culture plates (Falcon, catalog no. 353046) in a 37°C incubator with 5% CO2. Colonies were routinely passaged at a 1:8 split ratio every four days using Gentle Cell Dissociation Reagent (Stem Cell Technologies, catalog no. 07174) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Studies involving hESCs were reviewed and approved by Mass General Brigham Institutional Biosafety Committee (2011B000287).

Mouse experiments

Mouse experiments and housing were performed according to the animal use protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Protocol 2016N000162). Timed pregnant dams of CD1 background were purchased from Charles River and arrived on the day of experiment. Animals were sacrificed using a euthanasia chamber with carbon dioxide.

GATA3-mScarlet reporter hESC line generation

To generate the donor plasmid, the left and right homology arms flanking the stop codon were amplified by high fidelity PCR (iProof, BioRad) from a template of genomic DNA isolated from H9 hESCs. The left homology arm (759bp) forward and reverse primers were 5’-GGTAGAAGAGAGGCAACCGA-3’ and 5’- ACCCATGGCGGTGACC-3’; right homology arm (984bp) primers were 5’- AGCCCTGCTCGATGCTC-3’ and 5’- GGCTGCAGGAATAGGGACAA-3’. These fragments were purified (PCR purification kit, Qiagen) and cloned into a pUC57 vector digested with NheI and SacI in a single reaction using HIFI cloning (New England Biolabs). For gRNA plasmid, oligos (5’-CACCGGCCCTGTGAGCATCGAGCA-3’ and 5’- aaacTGCTCGATGCTCACAGGGCC-3’) were annealed and ligated into pX458 vector (Addgene 48138, kindly provided by Feng Zhang) digested with BbsI. All plasmid sequences were verified by Sanger sequencing (Genewiz).

Donor and Cas9/gRNA vectors were co-transfected (TransIT-LT1, Mirus) into H9 cells that were dissociated into single cells using Accutase (Stem Cell Technologies). After passaging, Hygromycin (50 μg ml−1) was added to the culture medium and cells were maintained under selection for one week. By day 4–5, individual resistant colonies emerged, which were expanded and genotyped. We used the following flanking forward and reverse primers: 5’-CTAGCGGAAGATTTTATGGCACC-3’ and 5’-CATATCGATTGGCCCGGGAT-3’ to generate an 863bp product in correctly targeted clones. From one well of a 6-well plate we genotyped four clones, and three of which were correctly targeted and confirmed by Sanger sequencing. Clone #1 was subsequently used for differentiation experiments described throughout this paper.

Differentiation of hPSCs into ureteric bud (UB) organoids

hPSCs were dissociated into single cells using Accutase (Stem Cell Technologies, catalog no. 07920) and plated into 24-well plates (Thermo, catalog no.142475) at a density of roughly 30,000 cells/well in mTeSR1 with ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 (10 μM; Stem Cell Technologies). This resulted in ~30% starting confluency approximately 24 hours after plating. Cells were then differentiated into mesendoderm by adding 50 ng ml−1Activin A (PeproTech), 25 ng ml−1 BMP4 (PeproTech), 5 μM CHIR99021 (Cayman Chemical) and 25 ng ml−1 FGF2 (PeproTech) in basic differentiation medium consisting of Advanced RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies) and 1X L-GlutaMAX (Life Technologies) for 30 hours. Subsequently, cells were differentiated to IM by exposure to 1 μM A83-01 (Cayman Chemical), 25 ng ml−1 FGF2, 0.1 μM LDN193189 (LDN; Cayman) and 0.1 μM Retinoic acid (RA; Sigma Aldrich) for two days in Advanced RPMI 1640 supplemented with 1X L-GlutaMAX. Media was changed every day.

To induce ND, IM cells were dissociated with Accutase, pelleted, and resuspended in differentiation medium supplemented with 50 ng ml−1 FGF9 and 0.1 μM RA, and plated in 96-well, round bottom, ultra-low attachment plates (Corning, catalog no. 7007) at 2–3 × 104 cells per well. The plates were centrifuged at 100 × g for 15 seconds and cultured at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 2 days. This resulted in the formation of three-dimensional ND spheroids. At day 5, the half-medium change was performed using basic differentiation medium supplemented with 50 ng ml−1 GDNF (Peprotech) and 0.1 μM RA. As an alternative to using 96-well plates, we demonstrated the ability to plate the cells onto patterned microwells (AggreWell-400, Stem Cell Technologies) at day 3 following dissociation. For 24-well AggreWell plates, approximately 1.0 × 106 cells were plated into a single well according to manufacturer’s instructions.

On day 7 of differentiation, spheroids were embedded into 100% Matrigel Matrix (Corning, catalog no. 354234) and plated as a 45 μl droplet in 24-well plates (Thermo, catalog no. 142475). The matrigel was allowed to solidify for at least 30 minutes in the tissue culture incubator, then was overlayed with basic differentiation medium supplemented with 50 ng ml−1 GDNF, 50 ng ml−1 FGF10 (Peprotech), 2 μM CHIR, 0.1 μM LDN, 1 μM A83–01, 0.1 μM RA and 2–5 μM U0126 (Cell Signaling Technologies) for 7–10 days. The medium was replaced every 3–4 days as needed. In many instances, we found that NDs derived from BJFF.6 cells could be transitioned to 3-D matrix as early as day 6 rather than waiting until day 7, whereas the H9-derived structures failed to develop if transitioned to Matrigel prematurely.

Collecting duct (CD) organoid formation

To induce differentiated CD cell types, the organoids were transitioned to basic differentiation medium supplemented with 10 nM arginine vasopressin (AVP) and 10 nM aldosterone for 4 days to generate CD organoids. For the experiments shown in the publication, this transitioned was done at day 14 and organoids were culture for four additional days. However we have found that this differentiation process also works with comparable efficiency when done at later stages and for as short as 2–3 days.

Differentiation of metanephric progenitor cells

hPSCs were differentiated into metanephric mesenchyme according to previously published methods5. Briefly, cells were dissociated with Accutase and plated on to Matrigel-coated 24-well plates. The following day, cells were differentiated by exposure to 8 μM CHIR for four days, followed by 10 ng ml−1 Activin A for three days, and 10 ng ml−1 FGF9 for two days. Growth factors were provided in basic differentiation medium described above, and the media was changed daily. At day 9, the cells were collected for either analysis or for mixing in aggregates with UB organoid cells.

Chimeric aggregation assay

To assess the potency of the UB organoid tissue, we used re-aggregation techniques that have been previously described52 to generate chimeric kidney explants. Mouse embryos were isolated from timed pregnant females (Charles River) at E12.5 (day of plug = 0.5), and the entire urogenital systems were dissected and placed in DMEM (Corning Cellgro, catalog no. 10-013-CM). Kidneys were then isolated by manual dissection and dissociated into single cells by incubation in a 20 μl drop (4–6 kidneys per drop) of TrypLE at 37°C for 4 minutes. The enzyme was then quenched by adding 50 μl of Kidney Culture Media (KCM; DMEM, Pen/Strep, 10% fetal bovine serum) and incubating at 37°C for 10 minutes for recovery. The digested rudiments were then pooled in a 1.7 ml microcentrifuge tube with an additional 500 ul KCM, triturated using a P200 pipette, and counted. Simultaneously, UB organoids at day 11 were isolated from Matrigel and dissociated to single cells as described below (see section on scRNA-seq preparation). Aggregation was performed by mixing 90,000 fetal mouse kidney cells with 10,000 differentiated human UB cells in a microcentrifuge tube, and then the cells were pelleted at 700 × g for 5 minutes. The chimeric cell pellet was then picked up and placed onto a Nucleopore Track-Etch Membrane filter disk (Whatman, pore size 1 μm). The filter was floated on 1 ml KCM in a 24-well tissue culture plate and incubated for 72 hours.

UB organoid dissociation, single cell capture, and sequencing

For scRNA-seq, organoids were extracted from the Matrigel matrix using Cell Recovery Solution (Corning) on ice for 10–20 minutes, with intermittent pipetting usin a P1000 pipette until the organoids were freely floating. We transferred the suspension to a 15mL tube, allowed the organoids to sink by gravity, and aspirated the Cell Recovery Solution. After washing once with PBS, the organoids were incubated in TrypLE Express (Thermo Fisher) at 37°C for 10–12 minutes, at which point they dissociated into single cells. For day 7, the ND spheroids were directly collected, washed, and incubated in TrypLE Express for 7–10 minutes. The single cell suspensions were passed through a 70 μm reversible strainer (Stem Cell Technologies, catalog no. 27260) and pelleted via centrifugation at 400 × g for 3 minutes.

For multiplexing, samples were labelled using BD Human Single Cell Sample Multiplexing Kit (catalog no. 633781), pooled, and delivered to the Single Cell Core (HMS) for library preparation. Single cells were captured and libraries prepared using the BD Rhapsody system with the Whole Transcriptome Analysis (WTA) Amplification Kit (BD Biosciences, catalog no. 633801). All cells were loaded and captured on a single cartridge. The WTA and Sample Tag libraries were amplified and purified according to manufacturer’s protocol. The libraries were pooled at a ratio such that the Sample Tag library composed ~3%, and then sequenced by the HMS Biopolymers Facility using Illumina NextSeq 550 with High Output kit, yielding a depth of 25,000 reads/cell.

Analysis of scRNA-seq data

Raw sequencing data were processed using the BD Rhapsody Complete Analysis Pipeline on the Seven Bridges Genomics cloud platform, which resulted in de-multiplexed counts matrices of gene expression in single cells. The R-package Seurat (v4.0.4) was used for downstream analyses including quality control, data normalization, data scaling, and visualization. Cells that expressed less than 200 genes, greater than 8,000 UMI, greater than 30% of reads assigned to mitochondrial genes, or definitive multiplets with two distinct sample tags were filtered out of the analysis. The final dataset contained 609 and 4,095 cells in the day 7 and day 18 organoid, respectively. A principal component analysis was used for dimension reduction with a dimension value of 18 determined by the JackStrawPlot function. The top 2,000 variable genes were selected and used together with dimensional information for clustering. Unsupervised clustering was performed and Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction (UMAP) plots were generated. For reference-based mapping, we uploaded the dataset representing day 18 organoids as an R object to the human kidney application on the Azimuth web app (https://azimuth.hubmapconsortium.org). The R package Monocle (v2.20.0) was used to perform cell lineage trajectory analysis on a randomly down-sampled (500 cells) subset of the principal cells from day 18.

Inducible FOXI1 expression for specification of intercalated cells

cDNA for human FOXI1 was synthesized (Genewiz) and cloned into pDONR221 using Gateway cloning to generate an entry vector. The cDNA was shuttled into pInducer20-Blast (Addgene 109334, kindly provided by Jean Cook) recombination with LR Clonase II (Invitrogen). This plasmid was co-transfected with packaging and envelope plasmids (psPAX2, pMD2.G) into 293T/17 cells (ATCC), and lentiviral particles were harvested after 24 and 48 hours post-transfection.

H9 cells were passaged as single cells using Accutase with Y27632 and exposed to lentiviral supernatant for six hours. At six hours, media was changed with fresh mTeSR1. Two days following transduction, Blasticidin (10 μg ml−1; Invivogen) was added to the culture medium and cells were selected for four days. This cell line was differentiated into UB and CD organoids as described above. At day 14, the CD differentiation medium was supplemented with doxycycline (0.5 μg ml−1; Sigma) to activate expression of FOXI1.

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using Direct-zol RNA Miniprep (Zymoresearch, catalog no. R2051). 50–200 ng of RNA was used for reverse transcription with iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, catalog no. 1708891) according to the manufacture’s protocol. qRT-PCR was performed on iQ5 Multicolor Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad) using iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). Relative mRNA expression levels were analyzed by the ΔΔCT method and normalized to GAPDH gene expression. Primer sequences are listed in Supp. Table 2.

Immunofluorescent staining

Cells cultured on coverslips were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 45 minutes at room temperature (RT) and washed three times in PBS. For spheroids or organoids, the tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for one hour at RT and thoroughly washed in PBS. Then tissues were mounted in OCT compound (Fisher Scientific), frozen in blocks, and cut into 7 μm sections. The sections were stored in −80°C. For staining, cells or slides were incubated in blocking buffer (0.1% Triton X-100 and 5% normal donkey serum in PBS) for one hour at RT, and incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C in blocking buffer. They were then washed three times in PBS and incubated with secondary antibody (dilution 1:500) and DAPI (Sigma) for one hour at RT. Secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) were made in donkey and conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488, 594, or 647. A list of primary antibodies is shown in Supp. Table 3. After staining, slides were mounted with Fluoromount G (Invitrogen) and air-dried for a minimum of several hours at RT. Imaging was performed using confocal microscopy (Nikon C1, Tokyo, Japan). Quantification was performed using Image-J by counting random fields at 400X magnification.

For wholemount staining, 3-D organoids were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for one hour at RT and thoroughly washed in PBS. The organoids were then incubated in blocking buffer for one hour at RT, then incubated with primary antibodies in antibody dilution buffer overnight at 4°C. The organoids were then washed with PBS three times for 20~30 minutes each. The organoids were incubated with secondary antibodies and DAPI in antibody dilution buffer for 2 hours at RT, then washed with PBS three times for 30 minutes each. The organoids were moved on slides, flat-mounted with Fluoromount G, and coverslipped.

Electrophysiological measurements in transwell system

CD organoid-derived cells were dissociated to single cells and transitioned to 2D transwell culture conditions previously established for mouse CD cell lines11. Briefly, the cells were grown at 37°C with 5% CO2 in DMEM/F-12 media supplemented with insulin (5 mg ml−1), apotransferrin (5 mg ml−1), sodium selenite (60 nM), 1 triiodothyronine (1 nM), dexamethasone (10 nM), epithelial growth factor (10 ng ml−1), and fetal bovine serum (2% v/v). Under these conditions, we established a cell line that exhibited similar epithelial morphology as the mouse CD cells. The cells were serially passaged using Trypsin-EDTA. For electrophysiology studies, CD cells were seeded on Corning Cell Culture Inserts (12 well format, 0.4 mm pore size PET track-etched membranes) at 100,000 cells per well. Transepithelial resistance and voltage was monitored using epithelial voltohm meter (World Precision Instruments, EVOM3) with the STX2-plus electrode. The short-circuit current across the epithelia was calculated using Ohm’s law, Voltage = Current*Resistance. Amiloride (10 μM; Sigma) was added above the transwell and transepithelial voltage and resistance measurements were repeated after 5 minutes. Aldosterone (Sigma) was used at varying concentrations for 24 hours in the absence of dexamethasone. For FOXI1 experiments, bafilomycin-A1 (10 nM; Sigma) was added following addition of amiloride and measurements were repeated after another 5 minutes.

Transepithelial short-circuit current (Isc) Ussing chamber recordings

CD cells were grown on 12 mM Snapwell inserts with 0.4 μM polycarbonate membranes (Corning) in CD Medium for 7–14 days to ensure confluency. Snapwell inserts were mounted in Ussing Chambers (Physiological Instruments VCC MC8) at the Harvard Digestive Disease Center Core at Boston Children’s Hospital. Bath solutions of 120 mM NaCl, 25 mM NaHCO3, 3.3 mM KH2PO4, 0.8 mM K2HPO4, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 1.2 mM CaCl2, and 10 mM glucose were added to the chambers with bubbling CO2 to maintain a pH of 7.4. Snapwells were continuously clamped at 0 mV and ISC was recorded using LabChart software. Amiloride (10–100 μM) and, bafilomycin-A1 (10–100 nM) were added to the apical chamber as indicated.

Statistical analysis and reproducibility

Values were presented as mean ± standard deviation. Individual data points represent distinct samples rather than repeated measurements. All statistical tests performed were mentioned in figure legends. In brief, differences with values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Sample sizes were provided in the figure legends. Two-tailed unpaired t-test (Student’s t-test) assuming equal standard deviation was applied for statistical analysis of differences between two groups. Paired-sample t-test was used to compare the current results of induced-CD cells before and after amiloride treatment in Fig. 4. GraphPad Prism software 8 (GraphPad) was used to do statistical analysis. Statistical methods were not used to determine sample size. All p values were displayed in the figure legends.

The data shown in the Figures, and especially the micrographs depicted, are representative examples of results that have been repeated in independent experiments, typically numerous times. Specifically, the results in Fig. 1b and 1d were repeated in three experiments, Fig. 1f in >30 experiments, Fig. 1g in six experiments, Fig. 1i in four experiments, Fig. 2a–b in >30 experiments, Fig. 2c in three experiments, Fig. 2d in two experiments, Fig. 2e in three experiments, Fig. 2g in one experiment, Fig. 3c–d in at least eight experiments, Fig. 4a in three experiments, Fig. 4b in two experiments, Fig. 5b in one experiment, Fig. 5c–d in six experiments, Fig. 5e in two experiments, Extended Data Fig. 2a in >30 experiments, Extended Data Fig. 3a in >30 experiments, Extended Data Fig. 3b in two experiments, Extended Data Fig. 3c in >10 experiments, Extended Data Fig. 3d in two experiments, Extended Data Fig. 3i in three experiments, Extended Data Fig. 4a–f in two experiments, Extended Data Fig. 5a–c in >30 experiments, Extended Data Fig. 5d–f in two experiments, Extended Data Fig. 6a–b in two experiments, and Extended Data Fig. 6c in one experiment.

Data Availability

The scRNA-sequencing data from UB organoid differentiation are available at the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE206153. The RNA-seq data from microdissected mouse collecting ducts was download from the RNA-seq data from the Mouse Renal Epithelial Cell Atlas (esbl.nhlbi.nih.gov/MRECA/Nephron/).

Code Availability

Relevant code will be available upon request.

Reporting Summary

Information on research design and reagents is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Extended Data

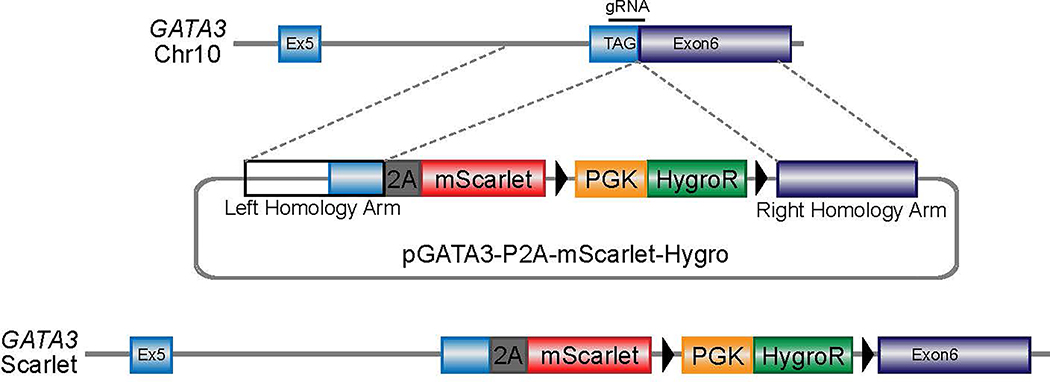

Extended Data Fig. 1. Generation of GATA3-mScarlet reporter allele.

Schematic representation depicting targeting scheme for CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knock-in of mScarlet into human GATA3 locus in H9 hESC line. The donor vector containing P2A-mScarlet and Hygro resistance cassette with flanking homology arms was co-transfected into cells with plasmid co-expressing Cas9 and gRNA targeting GATA3 stop codon.

Extended Data Fig. 2. Efficient induction of pronephric IM cells at day 3.

a, Brightfield micrographs demonstrating appearance of undifferentiated hESCs at day 0, as well cultures after 24 and 30 hours exposure to primitive streak-inducing factors. At 24 hours, there was still significant colony-like morphology consistent with incomplete induction of mesendoderm cells, but after six additional hours the colonies were nearly completely dissociated into single, mesenchymal-like cells. b, Quantification of IF staining for TBXT (as shown in Fig. 1b) revealed >95% efficiency after 30 hours exposure. n=6 quantified fields from three independent replicates. c, Timecourse qPCR analysis corresponding to Figure 1c. The primitive streak marker MIXL1 was maximally expressed at day 1 and was subsequently quickly down-regulated, while IM markers OSR1, HOXB7, HNF1B, and SOX9 were increased by day 3. n=3 independent biological replicates per timepoint. d, Efficient specification and expression of pronephric IM genes at day 3 was dependent on the combinatorial effects of FGF2, RA, TGFβ inhibition (A83-01), and BMP inhibition (LDN193189) during days 1–3. n=3 independent biological replicates per condition. e, In the pronephric IM cultures at days 3 and 7, there was low level of expression of posterior IM markers (WT1, SIX2, EYA1, and HOXA11), which were derived from a differentiation protocol for inducing metanephric progenitor cells. *, p<0.05; **p<0.005; two-tailed Student’s t-test individually comparing day 3 and day 7 against the day 9 posterior IM samples; n=4 biological replicates, data representative of 2 independent experiments. Specifically p-values for comparisons using day 3 were 0.005, 0.006, 0.0005, and 0.017 for WT1, SIX2, EYA1, and HOXA11, respectively; at day 7, they were 0.007, 0.007, 0.0002, and 0.015. f, From days 1–3, the TGFβ inhibitor A83-01 was required for suppression of definitive endoderm (SOX17) fate, whereas BMP inhibition with LDN193189 inhibited formation of lateral plate mesoderm (FOXF1). *p<0.005; two-tailed Student’s t-test; n=3 biological replicates, data representative of 2 independent experiments. Scale bar 200 μm (a). Column and error bars represent mean and standard deviation, respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 3. Characterization of nephric duct spheroids.

a, Pronephric IM cells aggregated at day 3 efficiently formed numerous compact spheroids that maintained high levels of GATA3 expression over the course of their development. b, When either FGF2 or FGF8 was used in place of FGF9 from days 3–5, the spheres were more loosely organized and exhibited lower expression of GATA3. c, Micrograph of a small region of nephric duct progenitors plated on a patterned microwell, demonstrating high degree of uniformity of size, shape, and structure of the spheroids. d, From days 4–7, the spheres maintained expression of early pronephric transcription factors LHX1 and HOXB7, and they also gradually acquired expression of nephric duct markers RET and EMX2. e, Over these several days of culture, qPCR analysis showed developmental increase in nephric duct genes RET, WNT11, WNT9B, and EMX2. n=3 independent biological replicates per timepoint. f, The leader cell marker ALDH1A3 was expressed in the ND clusters 2 and 3, while genes associated with more proximal ND (HOXB9 and TFAP2B) were less abundant. g-h, Heatmap and expression plots representing scRNA-seq data from day 7 revealed high expression of nephric duct markers in clusters 2 and 3, with complementary expression of stromal lineage genes in clusters 0 and 1 (in reference to UMAP in Fig. 1f). i, IF staining confirmed a high level of WT1-positivity in nephric duct lineage-negative cells at day 7. j, The differentiation of off-target lineages was not observed in the scRNA-seq dataset. Scale bars, 500 μm (a), 100 μm (b), 400 μm (c), 50 μm (d and h), 25 μm (i). Column and error bars represent mean and standard deviation, respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 4. UB organoid differentiation protocol is efficient when using hiPSCs.

a, Using the hiPSC line BJFF.6, a 30 hour exposure during the first stage of differentiation was also required for the primitive streak phenotype. b, AIM transcription factors PAX2, GATA3, LHX1, and HOXB7 were induced with very high efficiency by day 3. c, The hiPSC-derived AIM exhibited efficient formation of nephric duct spheroids in 96-well low attachment plates, which underwent similar molecular and morphological development compared to hESCs as shown in Figure 1. d, Nephric duct spheroids efficiently grew into branched UB organoids. e-f, hiPSC-derived UB organoids exhibited tip-stalk patterning and spontaneously formed differentiated AQP2-positive principal cells. Scale bars, 50 μm (a-d) and 100 μm (e-f).

Extended Data Fig. 5. Branching morphogenesis in UB organoids.

a, After embedding in 3-D matrix at day 7, the UB organoids exhibited several rounds of iterative branching during the first week of culture. The stereomicrograph of day 11 UB organoid demonstrates multiple terminal branching events, with each generation uniquely colored: 1=green, 2=red, 3=blue, 4=orange. b, A characteristic terminal bifurcation was demonstrated in the time course of micrographs. c, At later stages, such as day 18, branching was slowed and instead the distal UB tips formed enlarged knobs that more rarely underwent further cleavage events. d-e, Wholemount IF staining at days 9, 11, and 14 as shown in Fig. 2c with separation of channels. f, Expression of the transcription factor HNF1B increased between days 9–14. g, From day 7, the UB organoids showed a gradual decline in the tip marker WNT11 and a corresponding increase in the medullary stalk marker WNT7B. WNT9B, which is more broadly expressed in the stalk components, was maintained at relatively stable levels. n=3 independent biological replicates per timepoint. Scale bars, 50 μm (a-c) and 200 μm (d-f). Column and error bars represent mean and standard deviation, respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 6. UB progenitor cells participate in niche interactions in chimeric explants but not with hPSC-derived metanephric cells.

a, Cells from induced UB organoids and metanephric kidney organoids were dissociated at day 7, mixed and reaggregated, and cultured as spheres in suspension. Within two days (at day 9) the GATA3/KRT8-expressing UB cells had formed an epithelial network in the inner portion of the organoid. Metanephric cells (PAX2 only) were differentiating around the periphery of the structure in close association with the UB cells. However, we did not observe formation of capping mesenchyme structures or branching within the UB epithelium. b, Brightfield image with visualization of the UB epithelium using GATA3-mScarlet reporter confirmed the absence of significant branching morphogenesis. c, In chimeric explants with mouse fetal kidneys, the human induced UB cells (indicated by human nuclear antigen detection) incorporated into the UB tip (Cdh1-positive) at a high frequency, but never into the surrounding metanephric progenitors (Wt1 and Six2). Shown are six representative examples of progenitor niches that contained human cells. Scale bars, 200 μm (a and b) and 20 μm (c).

Extended Data Fig. 7. Characterization of CD organoids using scRNA-seq.

a, UB and CD transcription factors were abundant in clusters 0–4, which contained >97% of the sequenced cells (b). c, Expression of markers associated with other differentiated nephron segments, including podocytes, proximal tubule, thick ascending limb of Henle’s loop (TAL), and distal convoluted tubule (DCT), was largely absent in the dataset. d, Mapping prediction scores from Azimuth analysis were notably higher in clusters 0–2, which contained the more differentiated principal cell populations, while the scores were fairly low in clusters 3 and 4. e, Similarly, the prediction scores for cells that mapped to alternative tubular fates (found almost exclusively in clusters 3 and 4) were generally much worse than those that mapped to collecting duct. f, UMAP of clusters 0–4 following random downsampling to 500 total cells that were used in Monocle trajectory analysis. g, The predicted lineage trajectory plotted by pseudotime, which corresponds to Fig. 3i.

Extended Data Fig. 8. Amiloride-sensitive sodium conductance in two-dimensional culture.

a, Data tables from voltmeter experiments using hESC-derived collecting duct cells. The transepithelial resistances and voltages were directly measured, from which short circuit currents were calculated and normalized to surface area of the transwell filter. b-c, Transepithelial voltage and resistance measurements in response to varying concentrations, including both pre- and post-amiloride treatment. Data shown (n=4 per dose) are representative of at least three independent experiments. d, Quantification of RNA-seq expression levels of potassium channels from microdissected mouse CD segments41, including connecting tubule (CNT), cortical CD (CCD), outer medullary CD (OMCD) and inner medullary CD (IMCD). Kcnj1 and Kcnj10 were absent in the IMCD, while Kcnj13 and Kcnj16 were expressed in all CD regions. n=7 independent biological replicates per segment. e, In day 18 CD organoids, only KCNJ16 was expressed at high levels in the scRNA-seq dataset. Column and error bars represent mean and standard deviation, respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 9. CD organoids resemble the IMCD with respect to IC differentiation.